Abstract

Comprehensive profiling of actionable mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is vital to guide targeted therapy, thereby improving the survival rate of patients. Despite the high incidence and mortality rate of NSCLC in Vietnam, the actionable mutation profiles of Vietnamese patients have not been thoroughly examined. Here, we employed massively parallel sequencing to identify alterations in major driver genes (EGFR, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1) in 350 Vietnamese NSCLC patients. We showed that the Vietnamese NSCLC patients exhibited mutations most frequently in EGFR (35.4%) and KRAS (22.6%), followed by ALK (6.6%), ROS1 (3.1%), BRAF (2.3%) and NRAS (0.6%). Interestingly, the cohort of Vietnamese patients with advanced adenocarcinoma had higher prevalence of EGFR mutations than the Caucasian MSK-IMPACT cohort. Compared to the East Asian cohort, it had lower EGFR but higher KRAS mutation prevalence. We found that KRAS mutations were more commonly detected in male patients while EGFR mutations was more frequently found in female. Moreover, younger patients (<61 years) had higher genetic rearrangements in ALK or ROS1. In conclusions, our study revealed mutation profiles of 6 driver genes in the largest cohort of NSCLC patients in Vietnam to date, highlighting significant differences in mutation prevalence to other cohorts.

Subject terms: Non-small-cell lung cancer, Genetic testing

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer related deaths worldwide (18.4% of total cancer deaths), with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) being the most common subtype, accounting for approximately 85% of all diagnosed cases1,2. The majority of NSCLC patients display advanced disease when diagnosed and thus have poor prognosis2,3. It is well established that acquired genetic alterations in certain driver genes result in tumour growth and invasiveness, and that patients harboring certain mutations may benefit from targeted therapies4,5. Indeed, a randomized clinical trial reported that advanced NSCLC patients harboring activating mutations in EGFR, one of the major driver genes of NSCLC, exhibited longer progression-free period when treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), gefitinib, compared to those treated with standard platinum based chemotherapy6. However, those who were treated with TKI drugs can acquire secondary resistant mutations, in which case a new treatment regimen is needed to maintain therapeutic effect7,8. In addition to EGFR, NSCLC patients carrying ALK or ROS1 rearrangement were shown to respond well to a different TKI drug, crizotinib, while BRAF mutated NSCLC patients can be treated with a combination of BRAF inhibitors, dabrafenib and trametinib9–12. These findings suggest that the identification of mutation profiles of NSCLC is critical in order to prescribe suitable TKI therapy as well as elucidate the molecular basis of drug resistance to provide timely treatment adjustment.

Since 2018, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recommended routine mutation testing for driver genes including EGFR, ALK, ROS1 and BRAF in clinical practice for NSCLC patients13. Although there are currently no targeted drugs for KRAS or NRAS mutated NSCLCs, mutation testing for these genes has also been recommended due to their proven impact on clinical outcomes of NSCLC patients14,15. Hence, simultaneous mutation profiling of these six driver genes has been recommended in current clinical practice13,16,17. Currently, information in publicly available database such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was obtained mostly from prospective studies in Caucasians and European cohorts. Therefore, the impact of heterogeneous genetic constitution of NSCLC patients across different populations might be underestimated17.

Vietnam displays higher incidence rate of lung cancer than the average worldwide incidence (14.5% versus 11% of all new cases) despite having the same level of mortality rate according to the latest Globocan data18,19. Also, in Vietnam lung cancer is the most aggressive type of cancer in men and ranks as the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women18,19. Therefore, it is important to assess the mutation landscape as well as their association with unique clinicopathological features of Vietnamese NSCLC patients. In the present study, we employed massively parallel sequencing to detect genetic changes in six major driver genes including EGFR, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1 in tumour tissues from 350 NSCLC patients in Vietnam. Interestingly, we found that the Vietnamese cohort had a significantly higher frequency of KRAS mutations as compared to Caucasians and East Asian cohorts. We further identified significant associations between the prevalence of these mutations with patients’ clinical features in the Vietnamese cohort. Our data provide valuable information for guiding targeted therapy and drug development for Vietnamese NSCLC patients.

Results

Clinical characteristics of Vietnamese NSCLC patients

The cohort in this study comprised of 350 patients diagnosed with NSCLC by clinical histology from 4 hospitals in Vietnam, with higher percentage of male compared to female (60.6% versus 37.4%, p < 0.05) and the median age of 61 years, ranging from 24 to 89 years (Table 1). The majority of patients (289 cases, 82.6%) were classified into advanced stages (III-IV), while 12 patients (3.4%) were in early stages (I-II) and 49 cases (14%) missing information on clinical stages (Table 1). Adenocarcinoma (AC) was the most common NSCLC subtype (241 cases, 68.9%) while squamous carcinoma (SCC) was confirmed in 25 patients (7.1%). Additionally, 84 cases (24%) were of either unknown or uncharacterized subtypes (Table 1). Among 350 patients, 185 cases (52.8%) in this cohort had smoking status recorded including 54 smokers (15.4%) and 131 non-smokers (37.4%) while 165 cases (47.1%) had missing smoking status (Table 1). Treatment details were obtained for 306 patients (87.4%), including 285 patients (81.4%) who had never taken any treatment at the time of diagnosis and 21 patients (6%) experienced either tumour resection (5 cases, 1.4%), chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy (10 cases, 2.9%) or TKI therapy (6 cases, 1.7% for each treatment) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Major clinicopathological features of 350 Vietnamese NSCLC patients N: number of cases; AC: adenocarcinoma; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma.

| Clinical characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 131 | 37.4 |

| Male | 212 | 60.6 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 2 | |

| Age | < = 61 | 174 | 49.7 |

| >61 | 170 | 48.6 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 1.7 | |

| Smoking status | Yes | 54 | 15.4 |

| No | 131 | 37.4 | |

| Unknown | 165 | 47.1 | |

| Histology | AC | 241 | 68.9 |

| SCC | 25 | 7.1 | |

| Others or unknown | 84 | 24 | |

| Tumour Location | Lung | 231 | 66 |

| Bronchi | 66 | 18.9 | |

| Others or unknown | 53 | 15.1 | |

| Tumour Stage | I-II | 12 | 3.4 |

| III-IV | 289 | 82.6 | |

| Unknown | 49 | 14.0 | |

| Treatment information | Naïve to treatment | 285 | 81.4 |

| Resection | 5 | 1.4 | |

| Chemotherapy /Radiation | 10 | 2.9 | |

| TKI | 6 | 1.7 | |

| Unknown | 44 | 12.6 |

Mutation profiles of driver genes in Vietnamese NSCLC patients

In the present study, we developed a targeted capture sequencing assay to analyse genetic alterations in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue biopsy specimens of NSCLC patients. We first validated our assay by comparing its performance with a commercial droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assay (Bio-rad) for detecting three major EGFR mutations (L858R, del19 and T790M) in 40 tissue samples randomly selected from our cohort. When ddPCR results were used as reference standard, our targeted capture sequencing assay exhibited sensitivity of 81.8% (11/13), specificity of 100% (27/27) and concordance rate of 95% (38/40) (Table 2, Table S2). The two cases (LBL021 and L10021) that were positive for del19 mutation by ddPCR but missed by our assay had relatively low variant allele frequency (VAF) of 0.5% and 3.9%, respectively, below the limit of detection of our assay (4%) (Table S2). Hence, these results confirmed that our targeted capture sequencing assay achieved precise identification of mutations with VAF >4% in FFPE tissue samples. Therefore, this assay was subsequently used to identify genetic alterations in six major driver genes of NSCLC including KRAS, EGFR, NRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1 for the cohort of 350 NSCLC patients.

Table 2.

Comparison of EGFR mutation detection between our targeted capture sequencing assay and a commercial ddPCR assay.

| ddPCR | NGS | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Wild type | Total | |||

| Mutation | 11 | 2 | 13 | Sensitivity (%) | 84.6% (95% CI:54.5%–98.1%) |

| Wild type | 0 | 27 | 27 | Specificity (%) | 100% (95% CI:87.2%–100%) |

| Total | 11 | 29 | 40 | Concordance (%) | 95% (95% CI:83.1%–99.4%) |

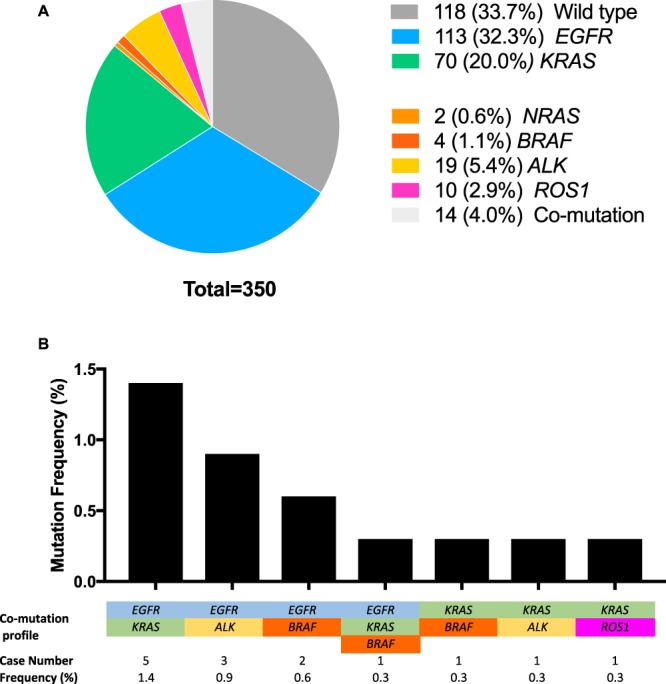

Among 350 patients successfully sequenced, 232 (66.3%) cases were found to carry at least one clinically relevant genetic alteration (according to ClinVar) in the tested driver genes while the remaining 118 cases (33.7%) were negative for these mutations (Fig. 1A). EGFR (32.3%) and KRAS (20%) were the most frequently mutated driver genes, followed by ALK (5.4%), ROS1 (2.9%), BRAF (1.1%) and NRAS (0.6%) (Fig. 1A). Although mutations in driver genes such as EGFR, KRAS and ALK were reported to be mutually exclusive in majority of NSCLC patients20, we detected 14 cases (4%) carrying mutations in more than one driver genes (Fig. 1B). Of those, the co-occurrence of mutations in EGFR and KRAS was the most common (6 cases), including one case carrying concurrent mutations in 3 driver genes (EGFR, KRAS and BRAF). EGFR mutation was also found in 3 cases with ALK rearrangement and 2 cases with BRAF mutation. In addition, KRAS mutations were also detected in patients carrying BRAF (2 cases), ALK (1 case) and ROS1 (1 case) mutations (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

The mutation composition in six major driver genes in 350 Vietnamese NSCLC patients. (A) Prevalence of mutations in 6 major driver genes determined by targeted capture sequencing. Cases with mutations occurring in more than one driver gene were counted as “co-mutation”. (B) Mutation frequency in cases harbouring co-mutations.

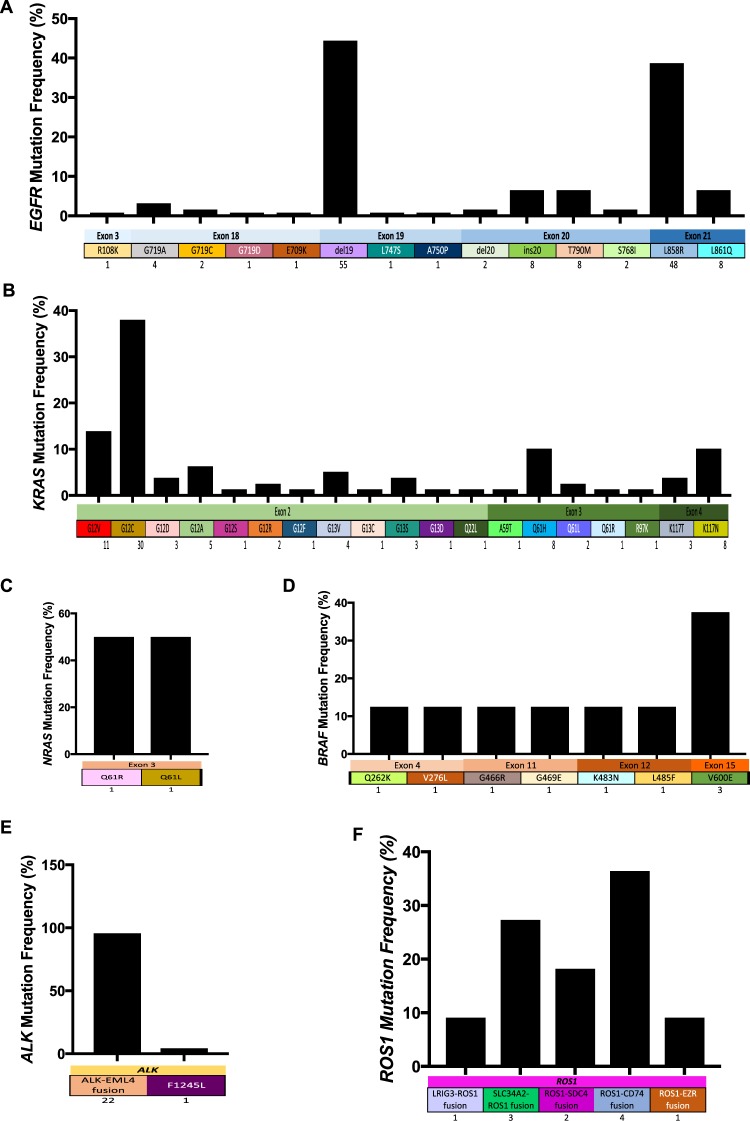

We next explored the distribution of mutation sites and subtypes across the six driver genes. EGFR mutations were predominantly detected in exon 19 and exon 21, with activating mutations del19 (55 cases) and L858R (48 cases) accounting for the majority of EGFR mutations (83.1% of all EGFR mutation events) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, mutations reported to be associated with resistance to TKI therapy, including T790M and ins20 in exon 20, were detected in 16 patients (12.9% of total patients, 8 cases for each mutation type) (Fig. 2A). All ins20 mutations were later confirmed by a real time-PCR based commercial assay Cobas® EGFR Mutation Test (Roche) (Data not shown). Additionally, other rare mutations with prevalence of less than 1% were also detected in exon 3 (R108K) and exon 18 (G719A, G719C, G719D and E709K) (Fig. 2A). The most common KRAS mutations occurred in exon 2 at G12 and G13 residues, accounting for 62/79 cases (78.4% of total KRAS mutation cases, Fig. 2B). Mutations were also detected in exon 3, residues Q61 (11 cases, 13.9%) and exon 4, residue K117 (11 cases, 13.9%, Fig. 2B). There were 8 cases carrying more than one KRAS mutation subtype and such concurrent mutations tend to arise at the same residue, with 6 out of 8 cases carrying co-mutations at the same residue (1 case at G12, 4 cases at G13 and 1 case at Q61) (Fig. 2B). Mutations in NRAS were detected in exon 3, residue Q61 (Fig. 2C); and mutations in BRAF were detected in exon 4, 11 and 12 (2 cases each) and exon 15, residue V600 (3 cases) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Distribution of mutation subtypes across 6 driver genes in Vietnamese NSCLC. (A–F) The mutation frequencies in particular subtypes of EGFR (A), KRAS (B), BRAF (C), NRAS (D), ALK (E) and ROS1 (F) genes were calculated as percentage of mutant cases in the total number of cases carrying mutations in the corresponding driver gene.

Our assay was able to detect genetic rearrangements in ALK and ROS1. ALK-EML4 translocation was identified as the most common mutation subtype (22/23 cases, 95.6%, Fig. 2E). All ROS1 mutations (11 cases) identified in this cohort were the results of fusion with the following genes: LIRG3 (1 case), SLC34A2 (3 cases), SDC4 (2 cases), CD74 (4 cases) and ERZ (1 case) (Fig. 2F).

Collectively, our data indicated that mutations in EGFR, KRAS are the two most common events occurring in more than half of all tested NSCLC patients in Vietnam, followed by less frequent mutations in other tested genes.

Comparison of mutation profiles among three NSCLC cohorts

To put the mutation profiles found in the Vietnamese cohort into global context, we compared the prevalence of mutations in Vietnamese NSCLC patients with those found in two other cohorts including the Caucasian MSK-IMPACT cohort established by the Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center21,22 and East Asian (China) cohort retrieved from a study by Wang et al.23 (Table 3). Since the majority of patients in the Vietnamese cohort were diagnosed with AC subtype in advanced stages (III-IV), we selectively retrieved data from patients with comparable histology and tumour stage from the other two cohorts. Given the comparable histology and stage, the Vietnamese cohort had fewer female patients than the other two cohorts. Additionally, patients in this cohort were slightly younger than the MSK-IMPACT cohort (median age: 61 versus 64, p < 0.001, Table 3) but older than the East Asian cohort (median age: 61 versus 58, p < 0.001, Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of mutation frequency among the three cohorts.

| Characteristics | Vietnam (N = 220) | MSK-IMPACT (N = 764) | East Asia (N = 361) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | p | N | % | p | ||

| Sex | Female | 90 | 40.9 | 447 | 58.5 | <0.00001 | 201 | 55.7 | <0.001 |

| Male | 128 | 58.2 | 317 | 41.5 | 160 | 44.3 | |||

| UN | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | Min | 31 | 19 | <0.001 | 22 | <0.001 | |||

| Max | 86 | 93 | 84 | ||||||

| Median | 61 | 64 | 58 | ||||||

| EGFR | Mutant | 83 | 37.7 | 222 | 29.1 | <0.05 | 265 | 73.4 | <0.00001 |

| WT | 137 | 62.3 | 542 | 70.9 | 96 | 26.6 | |||

| KRAS | Mutant | 47 | 21.4 | 188 | 24.6 | NS | 33 | 9.1 | <0.0001 |

| WT | 173 | 78.6 | 576 | 75.4 | 328 | 90.9 | |||

| NRAS | Mutant | 1 | 0.5 | 10 | 1.3 | NS | Not tested | ||

| WT | 219 | 99.5 | 754 | 98.7 | |||||

| BRAF | Mutant | 5 | 2.3 | 26 | 3.4 | NS | 5 | 1.4 | NS |

| WT | 215 | 97.7 | 738 | 96.6 | 356 | 98.6 | |||

| ALK | Mutant | 17 | 7.7 | 30 | 3.9 | NS | 31 | 10.0 | NS |

| WT | 203 | 92.3 | 734 | 96.1 | 330 | 90.0 | |||

| ROS1 | Mutant | 5 | 2.3 | 23 | 3.0 | NS | 6 | 1.7 | NS |

| WT | 215 | 97.7 | 741 | 97.0 | 355 | 98.3 | |||

N: total case number

n: number of cases

%: percentage of cages

UN: unknown

WT: wild type

Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test was conducted to compare the median age of patients at diagnosis

Chi-squared (χ²) test was performed to compare gender and mutation frequencies and the p-values were subsequently adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

NRAS mutations were not tested in the East Asian cohort.

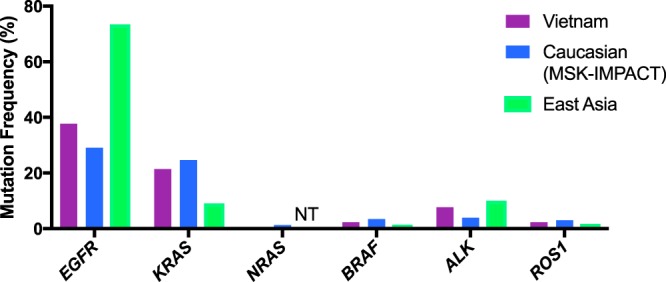

The prevalence of mutations in EGFR was significantly higher in the Vietnamese cohort compared to the MSK-IMPACT cohort (37.7% versus 29.1%, p < 0.05, Table 3 and Fig. 3) but markedly lower than the East Asian cohort (37.7% versus 73.4%, p < 0.00001, Table 3 and Fig. 3). Interestingly, the prevalence of KRAS mutations of the Vietnamese cohort was comparable to the MSK-IMPACT cohort while it was significantly higher than that of East Asians (21.4% versus 9.1%, p < 0.0001, Table 3, Fig. 3). Apart from KRAS and EGFR mutations, mutation frequencies of the remaining tested genes showed no significant differences between the Vietnamese cohort and the other two cohorts (Table 3, Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Comparison of driver gene mutation frequencies between Vietnamese NSCLC cohort with Caucasians and East Asians. Mutation frequency of each driver gene in the Vietnamese cohort was calculated among 220 patients with adenocarcinoma (AC) in late stages (III-IV) taking into account cases with co-mutation. For the Caucasian cohort, data were obtained from the MSK-IMPACT cohort (764 lung cancer cases with AC subtypes in metastatic stages (III-IV), Asian patients were excluded). For East Asia cohort, data we retrieved from a recent report profiling a similar panel of driver mutations in a Chinese cohort of 361 patients with AC in late stages (III-IV). NT: mutations were not tested.

In summary, the cohort of Vietnamese NSCLC patients showed specific characteristics that set it apart from the two other cohorts. It had higher prevalence of EGFR mutations than the Caucasian MSK-IMPACT cohort but lower than the East Asian cohort while its KRAS mutation prevalence is higher than the East Asian cohort.

Correlation between mutation prevalence and clinicopathological features of Vietnamese NSCLC patients

Previous studies have reported significant association between prevalence of driver mutations and patients’ clinicopathological features24–29. However, the results are often inconsistent across different studies. Here, we examined such associations in the Vietnamese NSCLC cohort.

Gender

Gender status was available in 343 patients including 131 female and 212 male patients (1:1.6 ratio); the 7 patients with unknown sex were excluded from gender association analysis. We performed Chi-squared (χ²) test to investigate the association between patients’ gender and mutation prevalence. Consistent with previous studies, we found that EGFR mutations were more commonly detected in Vietnamese female patients than in male patients (48.1% versus 26.9%, p < 0.00001, Table 4). Conversely, KRAS mutation frequency was significantly higher in male than that in female patients (30.7% versus 9.2%, p < 0.0001, Table 4). Other driver genes including NRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1 did not show any significant correlation

Table 4.

Association between clinical factors and mutation frequencies of NSCLC driver genes.

| Clinical characteristics | Total | EGFR | KRAS | NRAS | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not mutated | Mutated | p value | Not mutated | Mutated | p value | Not mutated | Mutated | p value | |||||||||

| Sex | Female | 131 | 68 | 51.9 | 63 | 48.1 | <0.0001 | 119 | 90.8 | 12 | 9.2 | <0.00001 | 131 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NS |

| Male | 212 | 155 | 73.1 | 57 | 26.9 | 147 | 69.3 | 65 | 30.7 | 210 | 99.1 | 2 | 0.9 | ||||

| Unknown | 7 | 3 | 42.9 | 4 | 57.1 | 5 | 71.4 | 2 | 28.6 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Age | <=61 | 174 | 112 | 64.4 | 62 | 35.6 | NS | 139 | 79.9 | 35 | 20.1 | <0.05 | 172 | 98.9 | 2 | 1.1 | NA |

| >61 | 170 | 112 | 65.9 | 58 | 34.1 | 127 | 74.7 | 43 | 25.3 | 170 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Unknown | 6 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 66.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 1 | 16.7 | 6 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

|

Smoking status |

Yes | 54 | 38 | 70.4 | 16 | 29.6 | <0.01 | 38 | 70.4 | 16 | 29.6 | <0.0001 | 54 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NA |

| No | 131 | 63 | 48.1 | 68 | 51.9 | 122 | 93.1 | 9 | 6.9 | 131 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Unknown | 165 | 53 | 32.1 | 112 | 67.9 | 93 | 56.4 | 72 | 43.6 | 163 | 98.8 | 2 | 1.2 | ||||

| Histology | ACC | 241 | 155 | 64.3 | 86 | 35.7 | <0.05 | 185 | 76.8 | 56 | 23.2 | NS | 240 | 99.6 | 1 | 0.4 | NS |

| SCC | 25 | 21 | 84 | 4 | 16 | 19 | 76 | 6 | 24 | 24 | 96 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Unknown | 84 | 50 | 59.5 | 34 | 40.5 | 67 | 79.8 | 17 | 20.2 | 84 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Clinical characteristic | Total | BRAF | ALK | ROS1 | |||||||||||||

| Not mutated | Mutated | p value | Not mutated | Mutated | p value | Not mutated | Mutated | p value | |||||||||

| Sex | Female | 131 | 128 | 97.7 | 3 | 2.3 | NS | 120 | 91.6 | 11 | 8.4 | NS | 124 | 94.7 | 7 | 5.3 | NS |

| Male | 212 | 207 | 97.6 | 5 | 2.4 | 201 | 94.8 | 11 | 5.2 | 208 | 98.1 | 4 | 1.9 | ||||

| Unknown | 7 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 85.7 | 1 | 14.3 | 7 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Age | <=61 | 174 | 171 | 98.3 | 3 | 1.7 | NS | 157 | 90.2 | 17 | 9.8 | <0.05 | 165 | 94.8 | 9 | 5.2 | <0.05 |

| >61 | 170 | 165 | 97.1 | 5 | 2.9 | 164 | 96.5 | 6 | 3.5 | 168 | 98.8 | 2 | 1.2 | ||||

| Unknown | 6 | 6 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Smoking status | Yes | 54 | 54 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NA | 53 | 98.1 | 1 | 1.9 | NS | 54 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | NA |

| No | 131 | 127 | 96.9 | 4 | 3.1 | 122 | 93.1 | 9 | 6.9 | 131 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Unknown | 165 | 159 | 96.4 | 6 | 3.6 | 144 | 87.3 | 21 | 12.7 | 154 | 93.3 | 11 | 6.7 | ||||

| Histology | ACC | 241 | 235 | 97.5 | 6 | 2.5 | NS | 223 | 92.5 | 18 | 7.5 | NA | 236 | 97.9 | 5 | 2.1 | NS |

| SCC | 25 | 24 | 96 | 1 | 4 | 25 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 96 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Unknown | 84 | 83 | 98.8 | 1 | 1.2 | 79 | 94.0 | 5 | 6.0 | 79 | 94.0 | 5 | 6.0 | ||||

N: total case number

n: number of particular group

%: percentage of particular cases in total number cases

Chi squared (χ²) test (sample size >5) or Fisher’s exact test (sample size< = 5) was performed to estimate p value.

AC: adenocarcinoma; SCC: squamous carcinoma; UN: unknown;

Age

Patient age was available in 344 patients, ranging from to 24 to 89 years old. When the median age (61 years) was used as a cutoff value, KRAS mutations were more frequently detected in elderly patients aged over 61 years than younger individuals (25.3% versus 20.1%, p < 0.05, Table 4). In contrast, the younger group showed higher prevalence of ALK (9.8% versus 3.5%, p < 0.05) and ROS1 (5.2% versus 1.2%, p < 0.05) mutations (Table 4). There was no significant correlation between patient age and mutation prevalence of other driver genes including EGFR, NRAS and BRAF (Table 4).

Smoking status

Of the 185 cases with smoking status, we could detect a statistically significant correlation between EGFR and KRAS mutation prevalence and smoking status (Table 4). Our data indicated that non-smokers showed significantly higher frequency of EGFR mutation (51.9% versus 29.6%, p < 0.01) but lower frequency of KRAS mutation (6.9% versus 29.6%, p < 0.001) than smokers.

Histology

Adenocarcinoma (AC) were diagnosed in 241 patients, accounting for the most common histological type (81%), while squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were identified in 25 cases (8.4%). We detected a significant association between histology type and EGFR mutation with higher prevalence in AC group than SCC group (35.7% versus 16%, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

NSCLC is the most common type of lung cancer with high rates of acquired somatic mutations2. Comprehensive profiling of clinically relevant mutations is of great importance in clinical practice for designing optimal targeted therapy as well as understanding drug resistance mechanisms30,31. Given the diversity of mutation constitution in different populations, the primary objective of our study is to examine the mutation profiles of major druggable driver genes in Vietnamese NSCLC patients. To this end, we performed targeted capture sequencing on 350 tumour tissue samples from Vietnamese patients with NSCLC and analyzed their genomic alterations in the six most common driver genes recommended by the ASCO and National Comprehensive Cancer Network for mutation testing in NSCLC patients17.

Our data showed that 66.3% of patients in the Vietnamese cohort harbour at least one alteration in the six tested driver genes. Our findings were consistent with our previous study using the same panel of genes and reporting a similar mutation rate of 63.6% in a smaller cohort of 59 Vietnamese NSCLC patients32. The mutation profiles of Vietnamese NSCLC patients also exhibited certain common features of NSCLC patients previously reported33,34. Firstly, mutations in EGFR and KRAS are the most common, accounted for more than 50% of total cases, while mutations in ALK, BRAF, NRAS and ROS1 were rarer. This trend was also reported in a Chinese cohort by Zhuang et al.33 or in Caucasian populations by Campbell et al.34. Secondly, the mutation sites within the driver genes identified in this cohort were similar to those reported in other populations, including these most common mutation sites: EGFR exon 19 deletion (del19) and exon 21 (L858R)35,36, KRAS exon 2 (G12C)37, BRAF V600E38 and ALK-EML4 fusion39. The frequencies of ALK (5.4%) and ROS1 (2.9%) mutations determined in our study (Fig. 1) are comparable to previously published studies reporting the frequencies of 5.05 and 1%-2% for ALK and ROS1, respectively40,41. EGFR del19, EGFR L858R, BRAF V600E, ALK-EML4 and ROS1 fusion mutations in combined (139 cases) accounted for 39.7% of cases in the Vietnamese cohort. They were known as activating mutations and clinically proven to be sensitive to treatments with available TKI drugs5,6,11,39. Thus, our findings suggested that approximately 40% of Vietnamese patients would carry such mutations and therefore would benefit from available targeted drugs. Among 6 patients currently known to be on TKI therapy (Table 1), 5 cases carrying activating EGFR mutations (EGFR del19, EGFR L858R) and one case positive for both EGFR L858R and ALK-EML4 fusion.

In contrast, some patients with activating EGFR mutations were found to develop an acquired resistance mutation, T790M42,43. Consistent with previous studies, we found that 7 out of 8 T790M cases were also positive for either L858R or del19 mutations and we suspected that these patients were under treatment with TKI drugs although we could not obtain treatment data for these cases. In addition to T790M, ins20 mutations were also known as resistant mutations44,45 and were detected in 8 cases in our cohort and most of them (6/8 cases) did not co-exist with any activating EGFR mutations L858R and del19, suggesting that ins20 mutations are likely primary inactivating mutations rather than acquired resistant mutations. Although a significant proportion of Vietnamese NSCLC patients were identified to carry KRAS mutations, drugs directly targeting KRAS mutated NSCLC are still under clinical evaluation46.

Although concomitant driver gene mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and ALK were initially reported to be mutually exclusive events in NSCLC patients20,47, we detected 14 cases (4%) harbouring concurrent alterations among the tested driver genes. These mutations might either coexist in the same tumour cell or belong to different tumour cell lines. The proportion of cases with co-mutations varied among studies. A recent study by Zhuang et al.33 involving a cohort of 3774 Chinese NSCLC patients reported a lower co-mutation rate of 1.67% in 5 tested driver genes (EGFR, KRAS, ALK, ROS1 and BRAF) while 5% of patients in another cohort of 1,000 NSCLC patients at The NCI’s Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium were reported to harbour concomitant driver gene mutations48. However, these studies together with our study consistently reported the EGRF/KRAS (6/14 cases in our study) as the most common co-mutation event in NSCLC patients33,48. The identification of patients with such co-mutations is of clinical importance since these concurrent mutations represent a distinct subset of patients and may have significant impact on treatment outcomes. In this regard, previous studies showed that patients carrying EGFR/ALK co-mutations varied in their sensitivity to and that the choice between these two classes of TKI drugs as first-line treatment for these patients is still being debated49. Hence, further studies are required to investigate clinical activity and drug sensitivity of different co-mutation subsets in order to develop suitable treatment approaches.

To identify Vietnamese-specific mutation profiles in NSCLC patients, we selected patients with comparable histology (AC) and tumour stage (stage III-IV) from the East Asian cohort (China)23 and the MSK-IMPACT cohort mainly consisting of Caucasia patients21,22. The prevalence of EGFR mutations among Vietnamese NSCLC patients was markedly lower than East Asia cohort (37.7% versus 73.4%, p < 0.00001, Table 3) but significantly higher than MSK-IMPACT cohorts (37.7% versus 29.1%, p < 0.05, Table 3), confirming previous reports that EGFR mutations are more prevalent in Asian patients than in Caucasian patients50. Of note, the percentage of Vietnamese patients with KRAS mutation including those with concurrent mutations was comparable to the MSK-IMPACT cohort but significantly higher than the published data in East Asian (21.4% versus 9.1%, p < 0.0001). Hence, our results demonstrated that NSCLC patients from Vietnamese population exhibit a unique mutation constitution, suggesting that ethnic composition might contribute to the observed variation in mutation profiles. Furthermore, Nguyen et al.32 reported a remarkably higher frequency of KRAS mutations in Vietnamese patients living in Vietnam than in those living in the USA (24.4% versus 4.5%), suggesting that geographic and socioeconomic disparities might also contribute to the variation in mutation frequencies in different cohorts. Although the clinical significance and mechanisms driving these variations are unclear, the unique mutation profiles should be taken into consideration for prioritizing research programs aiming to develop new treatment strategies for Vietnamese NSCLC patients.

KRAS mutations were detected in 30% of NSCLC patients who were non-responsive to TKI treatment51. Hence, the high prevalence of KRAS mutations in the Vietnamese NSCLC cohort might have negative impacts on clinical outcomes. However, the use of KRAS mutation status as a negatively predictive marker of TKI therapy remains controversial due to inconsistent results obtained from subsequent meta-analysis studies52–55. Interestingly, KRAS mutations, particularly the most prevalent subtype G12C, when co-existing with PD-L1 expression in patients’ tumour were shown to have poor prognosis56, supporting the potential benefit of KRAS mutation testing in selecting patients for immunotherapy using check-point inhibitor.

We further investigated correlations between mutation prevalence and major patients’ clinical characteristics. Consistent with previous studies25,50, we observed that EGFR mutations were more prevalent in female patients, non-smoker and those with histological subtype of AC. Unlike EGFR mutations, KRAS mutations were more commonly detected in male patients and showed significant correlations with patients’ age, with higher prevalence in elder patients. It is possible that the high prevalence of KRAS mutations in Vietnamese male patients may be responsible for their higher mortality rate. Previous studies reported that KRAS mutations more frequently arise in smokers than in non-smokers25,57. Consistently, we observed such correlation in our study, indicating that the high frequency of KRAS mutation in our cohort could be attributable to high prevalence of smoking in Vietnam population. In addition, we found that ALK and ROS1 rearrangement mutations were more common in younger patients as compared to elderly patients, which is consistent with previous studies28,29. Take together, our data revealed several significant correlations between driver gene mutation prevalence and patients’ clinical characteristics.

There are a few limitations in our study. Firstly, although the panel of driver genes used in this study was chosen based on ASCO guidelines5, we did not take into account mutations in other driver genes such as PIK3CA58, AKT159 and ERBB260, previously reported to co-exist with those detected mutations and possibly having significant clinical impacts. Secondly, when comparing the mutation profiles of the Vietnamese cohorts with MSK-IMPACT and East Asian cohort, we selected patients with AC in late stages (stage III-IV) to exclude the confounding effect of histological subtypes and tumour stage that are varied among three cohorts. However, there were still differences in patients’ age at diagnosis and gender ratio between the Vietnamese and the other two cohorts, which were identified be significant factors associated with EGFR and KRAS mutation prevalence, thus might have impact on the analysis of the mutation profiles. Future large-scale studies are required to assess whether these confounders contribute to the variations in mutation profile between the of Vietnamese population and other races.

In conclusions, our study revealed the mutation profiles of multiple driver genes in the largest cohort of NSCLC patients in Vietnam to date. Our data highlighted several subsets of Vietnamese NSCLC patients carrying specific mutations that would benefit from future studies to provide more suitable treatment options.

Material and Methods

Tumour tissues

We studied 350 formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour specimens from NSCLC patients treated at Pham Ngoc Thach hospital, Cho Ray hospital, Ha Noi Oncology hospital and Vietnam National cancer hospital. The tumour-rich areas of the tissues that contain at least 20% of tumour cells identified by a hematoxylin and eosin staining were micro-dissected. Written informed consents were obtained from all patients. Clinical characteristics of all patients were summarised in Table S1. This study was approved by The Ethic Committee of University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (Ethic number: 027/DHYD-HD) and The Medical Genetics Institute. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

DNA isolation

DNA was extracted from FFPE samples using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and then quantified using the QuantiFlour dsDNA system (Promega, USA).

Massively parallel sequencing

DNA fragmentation and library preparation were performed using the NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA library prep kit (New England Biolabs, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA library concentrations were quantified with a QuantiFlour dsDNA system (Promega, USA). Equal amounts of libraries (150 ng per sample) were pooled together and hybridized with xGen Lockdown probes for six targeted genes EGFR, KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, ALK and ROS1 (IDT DNA, USA). For ALK and ROS1, customized probes (Table S3) for intron regions were designed and mixed with probes for exon regions at equal concentration. Sequencing was run using NextSeq. 500/550 High output kits v2 (150 cycles) on Illumina NextSeq. 550 system (Illumina, USA) with minimum target coverage of 100×. In cases where the mean coverage in the targeted regions is lower than 100×, extra sequencing was performed to increase the mean coverage to the expected range. The mean coverage in the target regions for all samples is approximately 129×.

Variant calling using Mutect2 and Factera

Each FFPE sample was barcoded with dual indexes in the P7 and P5 primer. The PE reads were generated by bcl2fastq package (Illumina) and aligned to human genome (hg38) using BWA package61. Duplicate reads were marked using MarkDuplicates from Picard tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Somatic variants were called using Mutect2 package62. A custom pipeline with call to BWA, Picard, and Samtools packages were built to perform the above-mentioned analysis steps63. For detection of ALK and ROS1 rearrangement, fusion variant calling was analyzed using Factera v1.4.4 with default parameters64.

ddPCR method

A four-step ddPCR procedure was performed using reagents and equipment from Bio-Rad (unless otherwise stated) following the manufacturer’s instruction65. Briefly, the PCR mix was first prepared by mixing 1 × ddPCR Supermix for Probes, primers and probes (IDTDNA) and DNA template (0.8 or 1.6 ng). Next, 20 µl of the PCR mix was transferred into the Droplet Generator DG8TM Cartridge followed by 70 μl of the Droplet Generation Oil before placing in a QX100TM Droplet Generator to generate droplets. Subsequently, the droplets were transferred to a 96-well plate before placing in a thermal cycler (C1000 Touch, Bio-Rad) for PCR amplification. The PCR thermal program was performed as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 successive cycles of amplification (94 °C for 30 sec; 55 °C for 60 sec) and 98 °C for 10 min. Lastly, the droplet reading was acquired by the QX 200 Droplet reader and analyzed using the QuantaSoft Software. Positive and negative droplets are assigned based on the fluorescence threshold that was set as previously described by Deprez et al.66.

To detect T790M and L858R mutations in exon 20 and 21 of the EGFR gene, one reaction of ddPCR was used with two sets of primers and probes as follows: T790M primer F-GCCTGCTGGGCATCTG; T790M primer R-TCTTTGTGTTCCCGGACATAGTC; T790M mutation probe FAM- ATGAGCTGCATGATGAG-ZEN/3’IBFQ; L858R primer F-GCAGCATGTCAAGATCACAGATT; L858R primer R-CCTCCTTCTGCATGGTATTCTTTCT; L858R mutation probe HEX-AGTTTGGCCCGCCCAA- ZEN/3’IBFQ. For detection of 15 deletion sites in exon 19 (del19) of the EGFR gene, a commercially available ddPCR reaction (Bio-rad) was used (ddPCR™ EGFR Exon 19 Deletions Screening Kit #12002392).

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s chi-squared (χ²) test (sample size >5) or Fisher’s exact test (sample size< = 5) was performed on the web page ‘Social Science Statistics’ (http://www.socscistatistics.com) to assess the association between two categorical variables (Tables 3 and 4). Bonferroni correction was applied when multiple comparisons were performed (Table 3).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by Gene Solutions (GS-004). The funder (Gene Solutions) provided support in the form of salaries for authors V.U.T., T.T.T., H.A.T.P., H.T.T.D., B.T.V., L.T.N., T.C.V.N., L.H.N., N.H.N., H.N.D., L.S.T. and H.G. but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

A.T.H.D., V.U.T., H.A.T.P., T.T.T., B.T.V., H.T.T.D., L.T.N., T.C.V.N., Q.T.N.B. and L.H.N. performed experiments. A.T.H.D., D.T.L., L.N., N.V.N., T.H.T.N., C.V.N., H.T.L., M.L.T.N., V.T.L. and P.H.N. recruited patients and performed pathological analysis. N.H.N., Q.T.T.N., T.X.L., T.T.T.D., K.T.D. and H.N.D. designed experiments and analyzed data. M.D.P. revised the manuscript, H.N.N. supervised the project; L.S.T. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; H.G. designed experiments and analyzed sequencing data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Anh-Thu Huynh Dang and Vu-Uyen Tran.

Contributor Information

Hoai-Nghia Nguyen, Email: nhnghia81@gmail.com.

Le Son Tran, Email: leson1808@gmail.com.

Hoa Giang, Email: gianghoa@gmail.com.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-59744-3.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer J. clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sher T, Dy GK, Adjei AA. Small cell lung cancer. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2008;83:355–367. doi: 10.4065/83.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birring SS, Peake MD. Symptoms and the early diagnosis of lung cancer. Thorax. 2005;60:268–269. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.032698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tafe LJ, et al. Clinical Genotyping of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing: Utility of Identifying Rare and Co-mutations in Oncogenic Driver Genes. Neoplasia. 2016;18:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindeman NI, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J. Thorac. oncology: Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer. 2013;8:823–859. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318290868f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok TS, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sequist LV, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J. Clin. oncology: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu HA, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin. cancer research: an. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn L, Pao W. EML4-ALK: honing in on a new target in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;26:4232–4235. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw A, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;26:4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odogwu L, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Dabrafenib and Trametinib for the Treatment of Metastatic. Oncologist. 2018;6:740–745. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw A, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Ann. Oncol. 2019;30:1121–1126. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalemkerian G, Narula N, Kennedy E. Molecular Testing Guideline for the Selection of Lung Cancer Patients for. Oncol. Pract. 2018;14:323–327. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suda K, Tomizawa K, Mitsudomi T. Biological and clinical significance of KRAS mutations in lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roman M, et al. KRAS oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer: clinical perspectives on the treatment of an old target. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:33. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0789-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrer I, et al. KRAS-Mutant non-small cell lung cancer: From biology to therapy. Lung Cancer. 2018;124:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennell N, Arcila M, Gandara D, West H. Biomarker Testing for Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2019;39:531–542. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_237863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IARC, I. A. f. R. o. C. Global Cancer Observatory—Vietnam Population fact sheets. (2018).

- 19.Pham, T. et al. Cancers in Vietnam-Burden and Control Efforts: A Narrative Scoping Review. 26, 1073274819863802 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gainor JF, et al. ALK rearrangements are mutually exclusive with mutations in EGFR or KRAS: an analysis of 1,683 patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:4273–4281. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zehir A, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 2017;23:703–713. doi: 10.1038/nm.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan EJ, et al. Prospective Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Lung Adenocarcinomas for. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:596–609. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang R, et al. Comprehensive investigation of oncogenic driver mutations in Chinese non-small. Oncotarget. 2015;6:34300–34308. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, et al. Frequency of well-identified oncogenic driver mutations in lung adenocarcinoma of. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dogan S, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:6169–6177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae NC, et al. EGFR, ERBB2, and KRAS mutations in Korean non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2007;173:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014;9:154–162. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, et al. Prevalence of ROS1 fusion in Chinese patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer. 2019;10:47–53. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ke L, Xu M, Jiang X, Sun X. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Mutations and Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase/Oncogene or C-Ros Oncogene 1 (ALK/ROS1) Fusions Inflict Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Female Patients Older Than 60 Years of Age. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018;24:9364–9369. doi: 10.12659/MSM.911333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang H, et al. The role of liquid biopsy in predicting post-operative recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018;10:S838–s845. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.04.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Absenger G, Terzic J, Bezan A. ASCO update: lung cancer. Memo. 2017;10:224–227. doi: 10.1007/s12254-017-0373-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen KH, et al. Comparison of Genomic Driver Oncogenes in Vietnamese Patients With Non-Small-Cell. J. Glob. Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. doi: 10.1200/JGO.18.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuang X, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic options in non-small cell lung cancer patients with concomitant mutations of EGFR, ALK, ROS1, KRAS or BRAF. Cancer Med. 2019;8:2858–2866. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell JD, et al. Comparison of Prevalence and Types of Mutations in Lung Cancers Among Black and White Populations. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:801–809. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li K, Yang M, Liang N, Li S. Determining EGFR-TKI sensitivity of G719X and other uncommon EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Perplexity and solution (Review) Oncol. Rep. 2017;37:1347–1358. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;Suppl 1:S24–31. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boch Christian, Kollmeier Jens, Roth Andreas, Stephan-Falkenau Susann, Misch Daniel, Grüning Wolfram, Bauer Torsten Thomas, Mairinger Thomas. The frequency of EGFR and KRAS mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): routine screening data for central Europe from a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4):e002560. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paik PK, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2046–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross JC, et al. ALK Fusions in a Wide Variety of Tumor Types Respond to Anti-ALK Targeted Therapy. Oncologist. 2017;22:1444–1450. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.AACR Project GENIE: Powering Precision Medicine through an International. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rikova K, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soria JC, et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahn MJ, et al. Osimertinib in patients with T790M mutation-positive, advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Long-term follow-up from a pooled analysis of 2 phase 2 studies. Cancer. 2019;125:892–901. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vyse, S. & Huang, P. H. Targeting EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 4, 10.1038/s41392-41019-40038-41399. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Yasuda H, et al. Structural, biochemical, and clinical characterization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertion mutations in lung cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:216ra177. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garrido P, et al. Treating KRAS-mutant NSCLC: latest evidence and clinical consequences. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2017;9:589–597. doi: 10.1177/1758834017719829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leal, L. F. et al. Mutational profile of Brazilian lung adenocarcinoma unveils association of EGFR. Sci Rep. 9, 3209. 3210.1038/s41598-41019-39965-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Kris MG, et al. Identification of driver mutations in tumor specimens from 1,000 patients with lung adenocarcinoma: The NCI’s Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium (LCMC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:CRA7506–CRA7506. doi: 10.1200/jco.2011.29.18_suppl.cra7506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russo GL, et al. Concomitant EML4-ALK rearrangement and EGFR mutation in non-small cell lung cancer patients: a literature review of 100 cases. Oncotarget. 2017;8:59889–59900. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang YL, et al. The prevalence of EGFR mutation in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:78985–78993. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zandwijk NV, et al. EGFR and KRAS mutations as criteria for treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: retro- and prospective observations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18:99–103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pao W, et al. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loriot Y, Mordant P, Deutsch E, Olaussen KA, Soria JC. Are RAS mutations predictive markers of resistance to standard chemotherapy? Nature reviews. Clin. Oncol. 2009;6:528–534. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pesek M, et al. Dominance of EGFR and insignificant KRAS mutations in prediction of tyrosine-kinase therapy for NSCLC patients stratified by tumor subtype and smoking status. Anticancer. Res. 2009;29:2767–2773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE. KRAS mutation: should we test for it, and does it matter? J. Clin. oncology: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:1112–1121. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.43.0454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tao L, et al. The prognostic value of KRAS mutation subtypes and PD-L1 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:e20022–e20022. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.e20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minamimoto R, et al. Prediction of EGFR and KRAS mutation in non-small cell lung cancer using quantitative 18F FDG-PET/CT metrics. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52792–52801. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaft JE, et al. Coexistence of PIK3CA and other oncogene mutations in lung adenocarcinoma-rationale for comprehensive mutation profiling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:485–491. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rao, G. et al. Inhibition of AKT1 signaling promotes invasion and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer cells with K-RAS or EGFR mutations. Sci Rep. 7, 7066. 7010.1038/s41598-41017-06128-41599 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Chuang JC, et al. ERBB2-Mutated Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Response and Resistance to Targeted Therapies. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinforma. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Newman AM, et al. FACTERA: a practical method for the discovery of genomic rearrangements at breakpoint resolution. Bioinforma. 2014;30:3390–3393. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bio-Rad Laboratories, I. Rare Mutation Detection Best Practices Guidelines.

- 66.Deprez L, et al. Validation of a digital PCR method for quantification of DNA copy number concentrations by using a certified reference material. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 2016;9:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bdq.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.