Abstract

Introduction

The use of patient-reported outcome measures is increasingly advocated to support high-quality cancer care. We therefore investigated the added value of the Distress Thermometer (DT) when combined with known predictors to assess one-year survival in patients with lung cancer.

Methods

All patients had newly diagnosed or recurrent lung cancer, started systemic treatment, and participated in the intervention arm of a previously published randomised controlled trial. A Cox proportional hazards model was fitted based on five selected known predictors for survival. The DT-score was added to this model and contrasted to models including the EORTC-QLQ-C30 global QoL score (quality of life) or the HADS total score (symptoms of anxiety and depression). Model performance was evaluated through improvement in the −2 log likelihood, Harrell’s C-statistic, and a risk classification.

Results

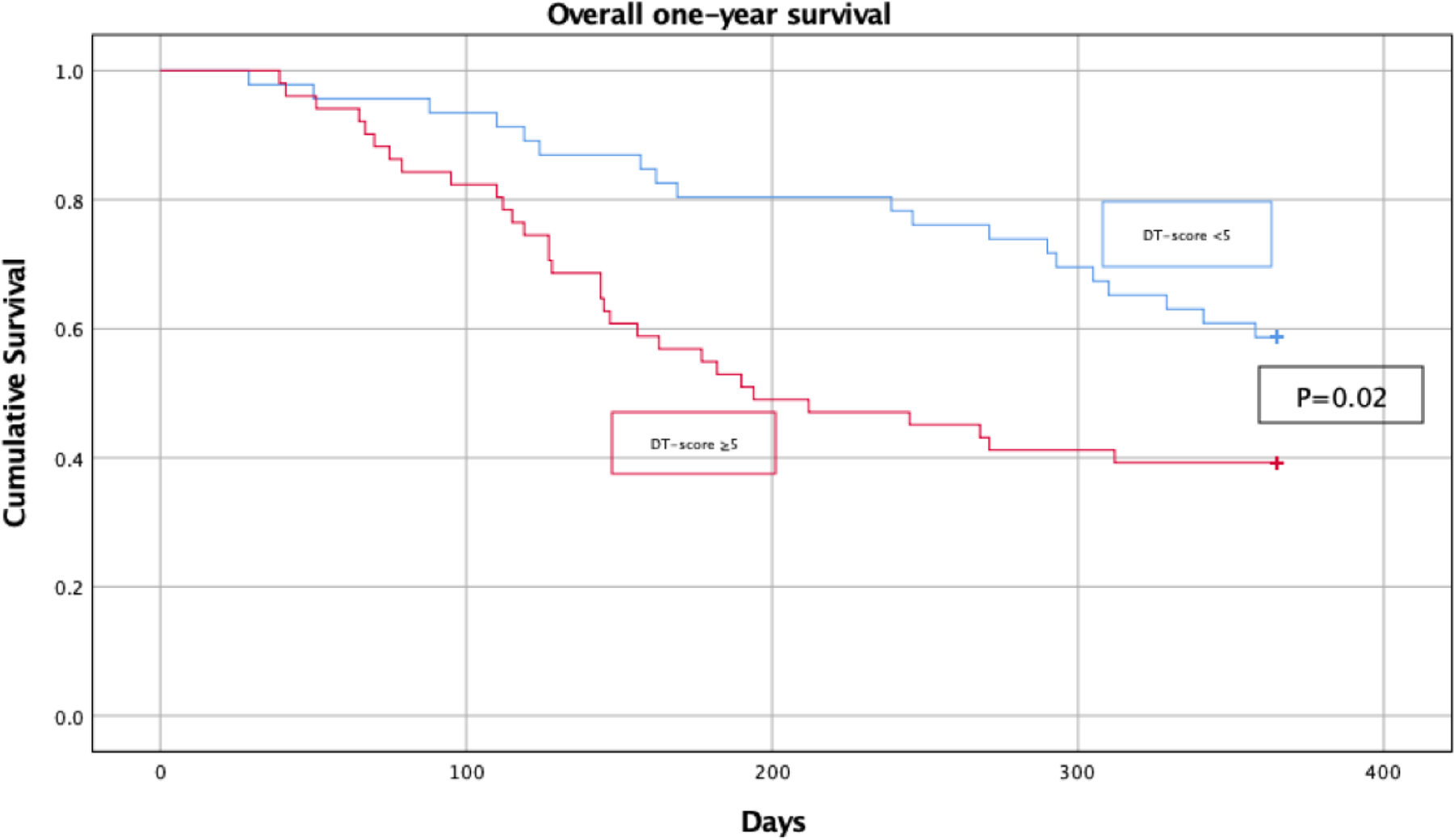

In total, 110 patients were included in the analysis of whom 97 patients accurately completed the DT. Patients with a DT score ≥5 (N=51) had a lower QoL, more symptoms of anxiety and depression, and a shorter median survival time (7.6 months vs 10.0 months; P=0.02) than patients with a DT score <5 (N=46). Addition of the DT resulted in a significant improvement in the accuracy of the model to predict one-year survival (P<0.001) and the discriminatory value (C-statistic) marginally improved from 0.69 to 0.71. The proportion of patients correctly classified as high risk (≥85% risk of dying within one year) increased from 8% to 28%. Similar model performance was observed when combining the selected predictors with QoL and symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Conclusions

Use of the DT allows clinicians to better identify patients with lung cancer at risk for poor outcomes, further explore sources of distress, and personalize care accordingly.

Keywords: Lung Neoplasm, Distress Thermometer, Survival, Prognostic Tool, Outcomes Research

1.1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common and deadliest cancer worldwide. It constitutes approximately 14 percent of all cancer diagnoses and 27 percent of all cancer deaths [1]. Most patients are diagnosed with either locally advanced or metastatic disease and are often faced with treatment-related toxicities and side-effects [2]. These factors contribute to a poor prognosis, high levels of distress, and a lower quality of life (QoL) among patients and their caregivers [3,4].

Despite this poor prognosis and limited survival, many patients with lung cancer receive aggressive treatments (e.g. chemotherapy) near the end of their life. Discussions focused on discussing the rationale for such treatments or patient’s goals and values either happen late in the disease course or are of insufficient quality [5]. Moreover, it may be difficult to accurately determine a patient’s prognosis due to the unpredictability of the disease course. Indeed, previous work shows that current prognostic predictions by clinicians are frequently inadequate and largely based on disease-related characteristics [6,7]. Recent studies have thus suggested that addition of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to such predictions can be useful to better approximate a patient’s prognosis [8–11]. Use and subsequent discussion of such measures also leads to better symptom control, increased use of supportive care facilities or measures, and enhanced patient satisfaction [12].

A PROM has been defined as “a measurement of any aspect of a patient’s health status that comes directly from the patient” [13]. International and consensus-based guidelines advocate the routine use of PROMs as an integral component of high-quality cancer care [9,11,14–16]. To date however, these measures are only sparsely incorporated in clinical care for patients with (lung) cancer [17,18]. One example of a possibly useful rapid assessment tool is the Distress Thermometer (DT). The DT is a single-item, visual analogue scale that can be immediately interpreted to rule out elevated levels of distress in patients with cancer [19,20]. The prognostic value of this tool for survival has not been confirmed among patients with lung cancer [21]. To this end, we sought to investigate the prognostic value of the DT when combined with sociodemographic and clinical predictors to assess one-year survival in patients with lung cancer. We also compared this model to models that included scores on quality of life or symptoms of anxiety and depression.

2.1. Methods

2.2. Design and setting

This study represents a secondary analysis of data obtained from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effects of screening for distress using the DT, the associated Problem List (PL) and additional supportive care measures to those in need of such care. This study detailed on the effects of this intervention on QoL, mood, patient satisfaction, and end-of-life care. The primary results of this trial are detailed elsewhere [22]. The RCT was conducted at the University Medical Center Groningen among patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent lung cancer starting systemic treatment. Randomisation, data collection and management was performed by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization. The study was approved by the institutional Medical Ethics Committee (NTR3540).

In short, patients were included within a week after start of systemic therapy and subsequently randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention group or the control group. Only patients assigned to the intervention group were invited to complete the DT and PL prior to their scheduled outpatient visit. Dependent on the DT-score, type of problems identified, and/or patient’s referral wish, responses were discussed with a nurse practitioner specialized in psychosocial issues. Patients were subsequently offered referral to an appropriate and licensed professional (e.g. a psychologist, social worker, physical therapist, or a dietician). Patients assigned to the control group were not routinely screened for distress and did not complete the DT and PL. They received care as usual as determined by the treating clinician. The primary outcome was the mean change in the EORTC-QLQ-C30 global QoL-score between 1 and 25 weeks.

2.3. Study population

Between 1 January 2010 and 30 June 2013, 223 patients were enrolled in the trial (response rate 66%). All patients had received a histological diagnosis of any type of lung cancer (stage Ib through IV), had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale of 0, 1 or 2, had to start a form of systemic treatment, were without cognitive impairment, and were able to complete questionnaires in Dutch. Systemic treatment was defined as treatment with chemotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, chemo-radiotherapy, or treatment with biologicals. Of the patients included, 110 were randomized to the intervention arm. These patients were asked to complete the DT and were therefore included in the current analyses.

2.4. Patient characteristics and survival

Sociodemographic characteristics were obtained from the hospital’s electronic health record at study entry as were clinical characteristics detailing on histological tumour type, performance status, recurrent versus new diagnosis, disease stage, initial type of treatment, and the Charlson age-adjusted co-morbidity index were also derived from the electronic health record [23]. Date of death was recorded from the electronic health record up to one year after randomisation.

2.5. Distress Thermometer, Quality of Life, and mood

The DT is an extensively validated measure to screen for distress [19,24,25]. It consists of a single-item, visual analogue scale with a score ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress) and is to be completed by the patient to quantify the level of distress experience in the past week. A score on the DT below either four or five, depending on the country and setting, has been propagated as optimal cut-off to rule out significant distress in patients with cancer [19,26]. An optimal cut-off value of five was observed among Dutch patients with cancer and therefore used in the current study. We did not use data obtained through the Dutch Problem List in these analyses.

All patients also completed the EORTC-QLQ-C30 [27] to assess health-related QoL and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [28] to assess mood. Scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 may range from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting better QoL. We only used the global QoL subscale in the current study as a best approximation to generic QoL. The HADS assesses symptoms of anxiety and depression over the past week with scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). It consists of 14 questions and scores may vary from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating more symptoms of anxiety or depression. All PROMs were completed after patients were randomised but within a week after the start of systemic therapy.

2.6. Selection of clinical predictors

Candidate predictors for one-year survival were selected based on the literature as well as expert opinion and availability of such predictors in clinical settings [29–33]. We selected the following five clinical or demographic predictors to be included in the model: 1) gender, 2) performance status (dichotomized as 0 or 1 versus 2), 3) disease stage (dichotomized as non-metastasized: stage I, II and IIIa versus metastasized: stage IIIb and IV) 4) the Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity index (entered as a continuous variable) and 5) tumour histology (dichotomized as non-small cell lung carcinoma versus small-cell lung carcinoma).

2.7. Statistical analyses

To characterize the study population, descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the frequencies, mean, and standard deviations for all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as well as other study measures at study entry. Patients with significant distress (DT-score ≥5) were compared to those without significant distress (DT-score <5) using independent T-tests and Chi-square tests [26]. The one-year survival of patients with and without significant distress was compared with the log-rank test and illustrated with a Kaplan-Meier curve. Statistical tests were performed with two-sided alternatives and considered significant if P ≤0.05, using SPSS software version 25 and STATA/IC version 13.

2.8. Model building

Univariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to determine the association of these predictors separately with one-year survival. We examined the proportional hazards assumption using log-minus-log plots. Regardless of statistical significance, all selected predictors were subsequently entered together simultaneously into a Cox proportional hazard model. This constituted the basic model. Hereafter, we separately added three sets of PROMs to the basic model: 1) the DT-score; 2) the EORTC-QLQ-C30 global QoL score; and 3) the HADS total score. We report on the added value of these PROMS to the basic model by evaluating the change in −2 log likelihood (−2LL), the statistical significance, and Harrell’s C-statistic with a 95% CI [34]. The −2LL is a measure of accuracy or overall performance of the model whereas the C-statistic demonstrates the difference in discriminatory value of a model comparable to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [34,35].

2.9. Reclassification of high-risk patients

To provide better clinical insight regarding the added value of the DT, we constructed a reclassification table including all patients who completed the DT. This table depicts the shift in classification of cases of mortality and non-cases separately for the basic model and the model after addition of the DT-score. To obtain this table, the individual survival risk was calculated for each patient using the baseline survival and the regression coefficients of the selected predictors. We then defined two risk groups (normal risk vs. high risk) primarily based on the net one-year survival date of patients with lung cancer. We defined the high risk group as patients having a one-year mortality risk as ≥85 percent [36,37]. This reclassification was not performed for models that included the EORTC-QLQ-C30 global QoL score or the HADS total score.

3.1. Results

3.2. Study population

Relevant demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients are displayed in Table 1. Approximately half of these patients was female (46%), 65% was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer, and 81% was initially treated with a chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy regimen. A total of 97 patients (88%) accurately completed the DT. Patients not completing the DT (N=13) were comparable in all sociodemographic as well as clinical characteristics to patients who completed the DT (all p-values ≥0.10; data not shown).

Table 1:

Description of total study population at study entry and comparison of groups with and without significant distress according to the Distress Thermometer

| Characteristic | Total study population (N=110) | DT-score < 5 (N=46)a | DT-score ≥ 5 (N=51)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 60.6 ± 10.5 | 59.8 ± 10.5 | 61.3 ± 10.7 |

| Female sex (N [%]) | 50 (46) | 20 (43) | 24 (47) |

| Performance status (N [%]) | |||

| 0 | 46 (42) | 22 (48) | 21 (41) |

| 1 | 56 (51) | 21 (46) | 27 (53) |

| 2 | 8 (7) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) |

| Recurrent disease, yes (N [%]) | 29 (26) | 9 (20) | 16 (31) |

| Disease stage (N [%]) | |||

| Stage 1 or 2 | 10 (9) | 5 (11) | 5 (10) |

| Stage 3 | 29 (26) | 14 (30) | 12 (23) |

| Stage 4 | 71 (65) | 27 (59) | 34 (67) |

| Smoking status (N [%]) | |||

| Yes | 48 (44) | 16 (35) | 28 (55) |

| Quit | 51 (46) | 25 (54) | 17 (33) |

| Never | 11 (10) | 5 (11) | 6 (12) |

| Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 8.3 ± 2.4 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | 8.6 ± 2.5 |

| Histology (N [%]) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 64 (58) | 25 (54) | 31 (61) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 19 (17) | 8 (18) | 9 (18) |

| Large cell n.o.s. | 5 (5) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Small-cell carcinoma | 20 (18) | 10 (22) | 8 (16) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Initial type of treatment (N [%]) | |||

| Chemotherapy | 60 (55) | 22 (48) | 32 (63) |

| Chemo-radiotherapy | 29 (26) | 15 (33) | 11 (22) |

| Biological | 21 (19) | 9 (19) | 8 (16) |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 scoreb, d (mean ± SD) | |||

| Global quality of life (N=94) | 59.2 ± 20.8 | 69.4 ± 19.1 | 51.5 ± 17.3*** |

| HADS score (mean ± SD)c, d | |||

| Anxiety subscale (N=93) | 6.4 ± 4.1 | 5.1 ± 3.6 | 7.5 ± 4.2** |

| Depression subscale (N=93) | 6.2 ± 3.9 | 4.9 ± 3.7 | 7.2 ± 3.6** |

| Total score (N=92) | 12.6 ± 7.2 | 10.0 ± 6.3 | 14.6 ± 7.0** |

| Distress Thermometer (N=97) | |||

| Score (median; range) | 5.0 (0 – 10) | - | - |

| Score ≥5 (%) | 46 | - | - |

Abbreviations: DT: Distress Thermometer, SD: Standard Deviation.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

P < 0.001, otherwise not significant (p>0.10)

Patients below the DT-score cutoff and DT-score above cutoff were compared. The remaining 13 patients did not accurately complete the DT and could not be included in this analysis.

The 30-item EORTC-QLQ-C30 assesses QOL. Scores can range from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting better functioning.

The 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) assesses anxiety and depression levels over the last week in two subscales each consisting of seven items. Scores vary from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety or depression.

Number of respondents vary and are denoted per questionnaire or subscale

3.3. Comparison of patients with and without significant distress

Of the 97 patients who accurately completed the DT, 51 had a DT score ≥5 and 46 had a score <5. Patients with and without significant distress were comparable in terms of sociodemographic and illness-related characteristics (Table 1; all p-values ≥0.10). Patients with clinically relevant distress reported a significantly lower global QoL (p<0.001), and depicted higher scores on the depression and anxiety subscales of the HADS as well as the total HADS score (p=0.004; p=0.004; and p=0.001; respectively). Median one-year survival time among patients with clinically relevant distress was significantly shorter: 7.6 months (95% CI: 6.5 – 8.7) versus 10.0 months (95% CI: 9.1 – 11.0; P=0.02).

3.4. Univariable analyses and performance of multivariable models

Table 2 displays the univariable relationships between the five selected predictors and the three sets of PROMS with one-year survival. Performance status, disease stage, and the Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity index were all found to be significant predictors. Of the included PROMs, the global QoL-score and the DT-score were identified as significant predictors, but not the HADS.

Table 2:

Univariable associations of selected clinical predictors with one-year survival

| Coefficient | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical predictors | |||

| Gender | |||

| Malea | - | - | - |

| Female | −1.95 | 0.82 (0.49 – 1.38) | 0.46 |

| Performance status at inclusion | |||

| 0, 1a | - | - | - |

| 2 | 1.43 | 4.18 (1.9 – 9.35) | 0.001 |

| Disease stage | |||

| Stage Ib, II, IIIaa | - | - | - |

| Stage IIIb, IV | 0.92 | 2.51 (1.14 – 5.53) | 0.02 |

| Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity index | 0.23 | 1.26 (1.12 – 1.42)*** | <0.001 |

| Histology | |||

| Non-small cell lung carcinomaa | - | - | - |

| Small-cell carcinoma | −0.25 | 0.78 (0.39 – 1.54) | 0.47 |

| Patient-reported outcome measures | |||

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 score | |||

| Global quality of life scale | −0.15 | 0.99 (0.97 – 1.0) | 0.02 |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale | |||

| Total score | 0.013 | 1.01 (0.98 – 1.05) | 0.32 |

| Distress Thermometer | |||

| Total score | 0.21 | 1.24 (1.09 – 1.40) | 0.001 |

Reference category

The Hazard Ratio is displayed per unit of the score for continuous variables.

Table 3 depicts the performance of the multivariable model as well as the performance of subsequent multivariable models when combined separately with the three sets of PROMs. The −2LL, i.e. the accuracy of the model, significantly improved after addition of the global QoL-score (491.4 to 431.9; P<0.001), addition of the HADS total score (491.4 to 410.0; P<0.001), and addition of the DT-score (491.4 to 397.5; P<0.001). The C-statistic, i.e. the discriminatory value, improved slightly from 0.69 (95% CI: 0.63 – 0.76) in the model with clinical predictors to 0.71 (95% CI: 0.64 – 0.77) after addition of the DT-score. Addition of the global QoL-score and the HADS total score led to a C-statistic of 0.69 (95% CI: 0.62 – 0.77) and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.60 – 0.75), respectively.

Table 3.

Different multivariable models of selected predictors when combined with various patient-reported outcome measures

| Variables included in model | −2 LL | P-value | C-statistic (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selected predictors (N=110) | 491.4 | - | 0.69 (0.63 – 0.76) |

| Selected predictors + global Quality of Life (N=99) | 431.9 | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.62 – 0.77) |

| Selected predictors + symptoms of anxiety and depression (N=96) | 410.0 | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.60 – 0.75) |

| Selected predictors + Distress Thermometer score (N=97) | 397.5 | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.64 – 0.77) |

P-value calculated (Chi-square two-sided test) versus model with selected predictors only

Abbreviations: −2 LL: −2 Log Likelihood. C-statistic: Harrel’s C concordance statistic

The five selected predictors: 1) gender, 2) performance status at inclusion, 3) disease stage, 4) Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity score, 5) histology.

Global Quality of Life was measured using the global QoL subscale of the EORTC-QLQ-C30. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale total score.

3.5. Improved reclassification of high risk patients

The reclassification model of the 97 patients of whom 50 died within one year is shown in Table 4. The proportion of correctly classified high-risk patients who died within one year increased from 8 percent to 28 percent (10 additional patients) after addition of the DT-score to the basic model. Moreover, addition of the DT-score did not considerably increase the proportion of patients incorrectly classified as high risk (Table 4; increase from 3% to 5%).

Table 4.

Improved predicted one-year mortality risk classification with addition of the Distress Thermometer score to selected predictors among 97 patients with lung cancer

| Observed death within one year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted risk of mortality within one year | Yes, N (%) | No, N (%) | Total |

| Selected predictors | |||

| Normal risk < 85% | 46 (92) | 46 (97) | 92 |

| High risk ≥85% | 4 (8) | 1 (3) | 5 |

| Total risk group | 50 (100) | 47 (100) | 97 |

| Selected clinical predictors + Distress Thermometer score | |||

| Normal risk < 85% | 36 (72) | 45 (95) | 81 |

| High risk ≥85% | 14 (28) | 2 (5) | 16 |

| Total risk group | 50 (100) | 47 (100) | 97 |

The five selected predictors: 1) gender, 2) performance status at inclusion, 3) disease stage, 4) Charlson age-adjusted comorbidity score, 5) histology.

4.1. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that addition of a patient-reported distress score, as measured by DT, to clinical predictors may hold prognostic value when estimating one-year survival. Similar results were obtained when combining the selected predictors with QoL and symptoms of anxiety or depression. Further, patients with clinically relevant distress had a significantly shorter median one-year survival time when compared to patients without clinically relevant distress, whilst being comparable in terms of clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. This finding was also supported by the improvement in the classification of patients with a high risk of death (≥85%) after combining the DT-score with selected predictors. This suggests that addition of a patient-centered outcome that can be rapidly interpreted, such as the DT-score, allows clinicians to more accurately determine which patients are at risk for a poor prognosis and possibly personalize care accordingly.

When viewed in the light of current clinical practice, these findings are important for several reasons. First, we specifically opted to study the prognostic value of the DT since prognosis of patients with lung cancer is often poor and the overall one-year net survival is only 30 percent [36,38]. The DT was originally developed as a rapid screening and diagnostic tool to rule out clinically relevant distress in patients with cancer [14,25]. Studying the prognostic value of the DT may thus move this tool beyond the originally intended purpose. Yet, other PROMs such as QoL, anxiety, and depression have previously been identified as important prognostic indicators in multiple, large-scale studies [8–11]. More importantly perhaps, these outcomes are associated with distress [39,40]. Having a fast and efficient tool available that screens for distress, and simultaneously conveys prognostic information, is therefore a promising finding in this patient population.

Second, numerous studies conducted across different care settings have provided clear evidence to support the earlier integration of palliative care, sometimes even delivered concurrently with (curative) treatment [41,42]. This has led to an increased interest with regards to the earlier integration as well as official endorsement by clinical guidelines [43]. Yet, many patients with advanced (lung) cancer either receive such care at a late stage and the quality of this care can be improved [44,45]. Although the use of a short screening tool cannot substitute careful clinical assessment and management, routine use of the DT may aid clinicians in identifying those patients at risk for poor outcomes and provide a vantage point from which to earlier engage patients and caregivers in patient-centered conversations about advance care planning and palliative care options.

In contrast to our findings, one previously conducted study (N=113) did not identify the prognostic value of the DT in patients with stage III lung cancer treated with chemotherapy containing carboplatin [21]. Notably, the observed median DT-score in that study was lower compared to the current study and the majority of patients refused to complete the DT and the associated Problem List. As described by the authors, this selection bias may account for the contrasting findings. Previous studies, although conducted among different cohorts of patients with advanced cancer, have shown that screening for distress has positive effects on the experienced of physical as well as psychosocial problems [46,47]. Moreover, these studies also observed that distress measures may convey important prognostic information in terms of survival.

A recent systematic review concluded that more effort is needed towards ensuring patients’ adherence when completing PROMs and that routine completion should be supplemented by clear guidelines to support clinicians when discussing responses with patients [12]. Other PROMs such as QoL and anxiety or depression have been found to convey important prognostic information in patients with cancer [9,11,16,48]. Yet, these instruments are often lengthy and require additional training and time investment. Also, healthcare professionals have cited practical concerns related to the length of questionnaires and required time investment, disruption of workflow, costs, and a lack of training for accurate interpretation [49]. In contrast to this, the DT allows for rapid assessment and may therefore be easier to integrate in clinical settings.

Our findings should be viewed in light of certain limitations. The current study represents a secondary analysis of a previously conducted RCT at a single, academic institution and our sample size was small. Further, although we did include patients with any histological subtype of lung cancer and all patients started a form of systemic treatment, only patients with an ECOG performance status between 0 and 2 were eligible for inclusion in the trial (the full score ranges from 0 to 5). These observations limit the generalizability of our findings. Third, the current patient population does not include patients treated with immunotherapy. This recent treatment modality is likely to markedly shift the prognosis of patients with advanced lung cancer in the near future. It would therefore be interesting to investigate whether patients with increased levels of distress are also at risk of a poor prognosis among patients treated with immunotherapy.

Next, we used the −2LL and the C-statistic as a best approximation to general performance of the different multivariable models. The −2LL did show significant improvements after addition of the different PROMs but we did not observe similar findings using the C-statistic (all values between 0.67 and 0.71). The C-statistic, however, has been criticized for a lack of sensitivity with regards to recognizing the added value of a risk marker. It has therefore been recommended to additionally report a reclassification table since this conveys important complementary information [50]. In line with this, we decided to use a cutoff of 85 percent to define patients at high risk of dying within one year [36,37]. We specifically decided not to include the EORTC-QLQ-C30 or the HADS in this reclassification table. Instead, we contrasted the performance of these PROMs in the outlined multivariable models to demonstrate similar performance of the DT when compared to other PROMs.

Although this cutoff likely represents the futility of further tumor-targeted treatment in this patient population, it was arbitrarily chosen and should be further validated in future studies. Last, the response rate in the original trial was relatively low (66%). This was most likely because of the high symptom burden these patients already face and was also stated as the most common reason for participation refusal (41% of objectors). This should be taken into consideration when interpreting our current findings.

4.2. Conclusions

In conclusion, this is the first study to provide evidence for added prognostic value of the DT-score in patients with lung cancer. The possible relationship between the DT-score and survival should be evaluated further in prospective, longitudinal studies across different settings and institutions [9]. Yet, our findings are promising and may allow clinicians to identify those patients at risk for poor outcomes and prevent discordance between care received and personal patient preferences near the end of life. This may further improve the timely delivery of high quality, patient-centered care for patients with lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier overall one-year survival curve stratified by significantly elevated elevated distress as evaluated by the Distress Thermometer (cutoff score of 5). Survival data was calculated from the date of randomization and date of death was recorded up to one year later.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL 1TR002541) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Further, the authors would like to thank Boudewijn Kollen from the Department of General Practice and Elderly Care Medicine at the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, for his statistical support throughout this study. Further, the authors are deeply grateful to Marleen Stokroos for her contribution to the randomised controlled trial. The current study would not have been possible without her efforts.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Lung Cancer, (2018). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed June 29, 2018).

- [2].LeBlanc TW, Nickolich M, Rushing CN, Samsa GP, Locke SC, Abernethy AP, What bothers lung cancer patients the most? A prospective, longitudinal electronic patient-reported outcomes study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer., Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 23 (2015) 3455–3463. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chambers SK, Girgis A, Occhipinti S, Hutchison S, Turner J, Morris B, Dunn J, Psychological distress and unmet supportive care needs in cancer patients and carers who contact cancer helplines., Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl) 21 (2012) 213–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, Earle CC, Weeks JC, End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study., Ann. Intern. Med 156 (2012) 204–210. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mrad C, Abougergi MS, Daly RM, Trends in aggressive inpatient care at the end-of-life for stage IV lung cancer patients., J. Clin. Oncol 36 (2018) 26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.30_suppl.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].White N, Reid F, Harris A, Harries P, Stone P, A Systematic Review of Predictions of Survival in Palliative Care: How Accurate Are Clinicians and Who Are the Experts?, PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0161407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Henselmans I, Smets EMA, Han PKJ, de Haes HCJC, van Laarhoven HWM, How long do I have? Observational study on communication about life expectancy with advanced cancer patients., Patient Educ. Couns 100 (2017) 1820–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li T-C, Li C-I, Tseng C-H, Lin K-S, Yang S-Y, Chen C-Y, Hsia T-C, Lee Y-D, Lin C-C, Quality of life predicts survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer., BMC Public Health. 12 (2012) 790. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ediebah DE, Coens C, Zikos E, Quinten C, Ringash J, King MT, Schmucker von Koch J, Gotay C, Greimel E, Flechtner H, Weis J, Reeve BB, Smit EF, Taphoorn MJ, Bottomley A, Does change in health-related quality of life score predict survival? Analysis of EORTC 08975 lung cancer trial, Br. J. Cancer 110 (2014) 2427–2433. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.208 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sloan JA, Zhao X, Novotny PJ, Wampfler J, Garces Y, Clark MM, Yang P, Relationship between deficits in overall quality of life and non-small-cell lung cancer survival., J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) 1498–1504. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vodermaier A, Lucas S, Linden W, Olson R, Anxiety After Diagnosis Predicts Lung Cancer-Specific and Overall Survival in Patients With Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Population-Based Cohort Study., J. Pain Symptom Manage 53 (2017) 1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, Harrow A, Di Domenico D, Croy S, Macgillivray S, What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials, J. Clin. Oncol 32 (2014) 1480–1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Valderas JM, Alonso J, Patient reported outcome measures: a model-based classification system for research and clinical practice., Qual. Life Res 17 (2008) 1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Holland JC, Andersen B, Breitbart WS, Compas B, Dudley MM, Fleishman S, Fulcher CD, Greenberg DB, Greiner CB, Handzo GF, Hoofring L, Jacobsen PB, Knight SJ, Learson K, Levy MH, Loscalzo MJ, Manne S, McAllister-Black R, Riba MB, Roper K, Valentine AD, Wagner LI, Zevon MA, Distress management., J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw 8 (2010) 448–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oncoline, Screening for psychosocial distress, 2013 (2013). http://www.oncoline.nl/screening-for-psychosocial-distress (accessed January 4, 2016).

- [16].Qi Y, Schild SE, Mandrekar SJ, Tan AD, Krook JE, Rowland KM, Garces YI, Soori GS, Adjei AA, Sloan JA, Pretreatment quality of life is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer., J. Thorac. Oncol 4 (2009) 1075–1082. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ae27f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ben Bouazza Y, Chiairi I, El Kharbouchi O, De Backer L, Vanhoutte G, Janssens A, Van Meerbeeck JP, Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in the management of lung cancer: A systematic review., Lung Cancer. 113 (2017) 140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Basu Roy U, King-Kallimanis BL, Kluetz PG, Selig W, Ferris A, Learning from Patients: Reflections on Use of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Lung Cancer Trials, J. Thorac. Oncol (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ma X, Zhang J, Zhong W, Shu C, Wang F, Wen J, Zhou M, Sang Y, Jiang Y, Liu L, The diagnostic role of a short screening tool--the distress thermometer: a meta-analysis, Support. Care Cancer 22 (2014) 1741–1755. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2143-1 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carlson LE, Waller A, Mitchell AJ, Screening for distress and unmet needs in patients with cancer: review and recommendations, J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) 1160–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509; 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].de Mol M, den Oudsten BL, Aarts M, V Aerts JGJ, The distress thermometer as a predictor for survival in stage III lung cancer patients treated with chemotherapy, Oncotarget. 8 (2017) 36743–36749. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Geerse OP, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, Stokroos MH, Burgerhof JGM, Groen HJM, Kerstjens HAM, Hiltermann TJN, Structural distress screening and supportive care for patients with lung cancer on systemic therapy: A randomised controlled trial, Eur. J. Cancer 72 (2017) 37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR, A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation, J. Chronic Dis 40 (1987) 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Donovan KA, Grassi L, McGinty HL, Jacobsen PB, Validation of the Distress Thermometer worldwide: state of the science, Psychooncology. 23 (2014) 241–250. doi: 10.1002/pon.3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mitchell AJ, Pooled results from 38 analyses of the accuracy of distress thermometer and other ultra-short methods of detecting cancer-related mood disorders., J. Clin. Oncol 25 (2007) 4670–4681. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: Use of the distress thermometer, Cancer. 113 (2008) 870–878. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 85 (1993) 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zigmond AS, Snaith RP, The hospital anxiety and depression scale, Acta Psychiatr. Scand 67 (1983) 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fu JB, Kau TY, Severson RK, Kalemkerian GP, Lung cancer in women: analysis of the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database., Chest. 127 (2005) 768–777. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Simmons CP, Koinis F, Fallon MT, Fearon KC, Bowden J, Solheim TS, Gronberg BH, McMillan DC, Gioulbasanis I, Laird BJ, Prognosis in advanced lung cancer – A prospective study examining key clinicopathological factors, Lung Cancer. 88 (2015) 304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Iachina M, Jakobsen E, Moller H, Luchtenborg M, Mellemgaard A, Krasnik M, Green A, The effect of different comorbidities on survival of non-small cells lung cancer patients., Lung. 193 (2015) 291–297. doi: 10.1007/s00408-014-9675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Subramanian J, Morgensztern D, Goodgame B, Baggstrom MQ, Gao F, Piccirillo J, Govindan R, Distinctive characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the young: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) analysis., J. Thorac. Oncol 5 (2010) 23–28. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c41e8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Woodard GA, Jones KD, Jablons DM, Lung Cancer Staging and Prognosis., Cancer Treat. Res 170 (2016) 47–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40389-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Newson RB, Comparing the predictive power of survival models using Harrell ‘ s c or Somers ‘ D, Stata J. 10 (1983) 1–19. doi:The Stata Journal. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bamber D, The area above the ordinal dominance graph and the area below the receiver operating characteristic graph, J. Math. Psychol 12 (1975) 387–415. doi: 10.1016/0022-2496(75)90001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cancer Research UK, Lung cancer survival statistics, (n.d.). https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/lung-cancer/survival (accessed August 28, 2018).

- [37].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D, Global cancer statistics, CA. Cancer J. Clin 61 (2011) 69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107; 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-tieulent J, Jemal A, Global Cancer Statistics, 2012, CA Cancer J Clin 00 (2015) 1–22. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Head BA, Schapmire TJ, Keeney CE, Deck SM, Studts JL, Hermann CP, Scharfenberger JA, Pfeifer MP, Use of the Distress Thermometer to discern clinically relevant quality of life differences in women with breast cancer, Qual. Life Res 21 (2012) 215–223. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9934-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Mitchell AJ, Short screening tools for cancer-related distress: a review and diagnostic validity meta-analysis., J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw 8 (2010) 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher E, Admane S, Jackson V, Dahlin C, Bilderman C, Jacobsen J, Pirl W, Billings A, Lynch T, Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer, N. Engl. J. Med 363 (2010) 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lammers A, Slatore CG, Fromme EK, Vranas K, Sullivan DR, Association of Early Palliative Care with Chemotherapy Intensity in Patients with Advanced Stage Lung Cancer : A National Cohort Study, J. Thorac. Oncol (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, Smith TJ, Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update Summary., J. Oncol. Pract 13 (2017) 119–121. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kaufmann TL, Kamal AH, Oncology and Palliative Care Integration: Cocreating Quality and Value in the Era of Health Care Reform., J. Oncol. Pract 13 (2017) 580–588. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.023762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nakano K, Yoshida T, Furutama J, Sunada S, Quality of end-of-life care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer in general wards and palliative care units in Japan., Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 20 (2012) 883–888. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kim GM, Kim SJ, Song SK, Kim HR, Kang BD, Noh SH, Chung HC, Kim KR, Rha SY, Prevalence and prognostic implications of psychological distress in patients with gastric cancer., BMC Cancer. 17 (2017) 283. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Carlson LE, Waller A, Groff SL, Bultz BD, Screening for distress, the sixth vital sign, in lung cancer patients: effects on pain, fatigue, and common problems--secondary outcomes of a randomized controlled trial, Psychooncology. 22 (2013) 1880–1888. doi: 10.1002/pon.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen J, Li W, Cui L, Qian Y, Zhu Y, Gu H, Chen G, Shen Y, Liu Y, Chemotherapeutic Response and Prognosis among Lung Cancer Patients with and without Depression., J. Cancer 6 (2015) 1121–1129. doi: 10.7150/jca.11239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Boyce MB, Browne JP, Greenhalgh J, The experiences of professionals with using information from patient-reported outcome measures to improve the quality of healthcare: a systematic review of qualitative research., BMJ Qual. Saf 23 (2014) 508–518. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Pencina KM, Janssens ACJW, Greenland P, Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models., Am. J. Epidemiol 176 (2012) 473–481. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]