Abstract

Background:

Monitoring and improving the quality of care is an ever increasing concern for health care organisations. Measuring the effectiveness of clinical outcomes is done by looking at specific markers of high quality care. Pain management is considered one of the markers of high quality care and satisfaction with pain management is a crucial and important quality assurance marker; yet, we know little about what contributes to a patient’s decision about satisfaction.

Methods:

A qualitative study drawing on phenomenological approach aiming to evaluate the perspective of patients experiencing post-operative pain. Patients undergoing major abdominal surgery were recruited from a Renal Transplant and Urology ward in the North of England, UK. Data were collected using in-depth semi-structured interviews and were analysed using Colaizzi’s approach.

Results:

Ten patients participated in the study and three themes emerged from the analysis. The findings of this study revealed that in order to achieve satisfaction with the management of pain, patient care has to include information delivery which is timely and adequate according to a patient’s individual needs, nurses should have a caring attitude and pain should be well controlled.

Conclusion:

Satisfaction with pain management is influenced by good communication and information transfer, appropriate pain management and an empathic presence throughout.

Keywords: Post-operative pain, pain management, patient satisfaction, patient experience, patient expectation

Background

Monitoring and improving the quality of care is an increasing concern for health care organisations. National Health Service (NHS) organisations in the United Kingdom are required to measure the effectiveness of clinical outcomes in order to identify factors that will improve the quality of care.1 Measuring the effectiveness of clinical outcomes is done by looking at specific markers of high-quality care and pain management is one of these. Many quality improvement programmes which mainly focus on timely pain assessment and management have been put in place.2–5

Despite the introduction of quality improvement programmes, in many places, pain management is suboptimal. In a multicentre study of emergency departments (n = 50), it was found that only 51% of 7265 patients identified to have pain were given pain treatment.6 Similar figures have been found in cancer care.7 In terms of documentation, a 1 day survey of inpatients (n = 279) found that 76% of patients had pain in the previous 24 hours and only 58% had pain assessment or management recognised in their records.8 In addition, a large-scale study of hospital electronic records found that 38.4% of 810,774 pain scores identified from 38,451 patient stays were clinically significant pain events. Yet only 0.2% of these scores were independent of other clinical observations suggesting that pain was not the clinical focus.9 Pain was assessed using the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) consisting of four categories: none (0), mild (1), moderate (2) or severe (3), pain scores of moderate or severe were categorised as ‘clinically significant pain’.

Due to the complexities of pain and its management, it is unclear what elements are necessary to determine quality care and which of these would be factored into patient satisfaction assessments. Martinez et al. undertook a large multivariate linear regression analysis of pain satisfaction from cancer patients (n = 2746). The results revealed that quality care was associated with physician communication, care coordination and responsiveness to pain severity.10 This agrees with another hospital study carried out by Zoega et al.11 to explore whether pain management practices in a university hospital were in line with guidelines on acute, geriatric and cancer pain. Patients were recruited from both medical and surgical wards (n = 308); 83% of patients with pain identified that satisfaction was linked to reduced time in severe pain. In addition, patient expectations and satisfaction are linked. One cancer study (n = 144) found that pain severity and patient expectation were inversely related12 which helps to establish a link between pain relief and satisfaction with pain management.13 Other factors which may be important in satisfaction with pain management are improved use of analgesia,14 pre-operative pain assessment15 and patient beliefs and attitudes.16

Nurses play a key role in trying to improve patient satisfaction: by focusing on better-quality pain management;17,18 by assisting in quality improvement programmes19,20 and by trying to understand what patients mean by satisfactory pain management.21,22 Understanding patient satisfaction with pain management will enable nurses to target care improvement. Beck and colleagues interviewed 33 people in pain and identified four themes that were important in satisfaction. These were being treated right; having a safety net; partnership with the health care professional and the need for the treatment to work.21 In addition, a qualitative literature review of satisfaction and the experience of care over 20 years in emergency departments found five themes.22 These are timeliness, empathy, the need for information, technical competence and pain management. Both studies identified that the patient is not just looking at zero pain by the use of analgesia alone. However, they are looking for relief from suffering associated with physical pain, functional impairment, fear and uncertainty.23

This review has highlighted what influences patient satisfaction in cancer care and emergency departments. However, the literature on the meaning that underlies patient judgements about satisfaction with post-operative pain management is limited. In the United Kingdom, care providers collect information through audit data to assess the effectiveness of their care delivery.24 The results of these audits reveal that despite advancements in analgesia administration, there remains a level of dissatisfaction with post-operative pain management. This study aimed to explore patient perspectives and satisfaction with their pain management following major surgery.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative study using a phenomenological approach.

Aims

To describe patient expectations related to the experience of pain.

To explore the meaning that underlies patient judgements about satisfaction with pain management.

Population and sampling

Participants were recruited from a Renal Transplant and Urology unit in a University Hospital located in the North West of England. A purposive sample was used to ensure that the sample chosen was able to provide the information needed for the topic25 using the following inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

18 years of age and over

Undergone open abdominal surgery, both elective and non-elective admissions.

English speaking.

Exclusion criteria

Vulnerable adults

Minor surgery.

Recruitment

Nurses on the ward reviewed patient’s notes to assess the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were given an invitation letter and the participant information sheet. Depending upon the surgery and the recovery of individual patients, this was done on the second or third post-operative day. The participants were given at least 24 hours to read and understand the information. If they agreed to participate in the study, written informed consent was obtained by the researcher and the interview date set before discharge from hospital. There was no minimum time point on the researcher coming to see the patient because it was dependant on the type of operation the patient had, the progress of the patient’s recovery and the patient’s willingness to talk. Confidentiality and anonymity was maintained through the study.

Data collection

Data were collected by semi-structured interviews using a pre-prepared guide of areas to be discussed (Table 1). Interviews were conducted by the researcher who had 15 years of surgical experience with a particular interest in acute pain management. The researcher was employed as a ward sister in the department where the patients were being recruited from. However, at the time of the study, the researcher was on study leave and had no direct clinical contact with the patients. Participants were given the choice to be interviewed face to face, in clinic, at home or over the phone. The interviews were arranged to take place as close to discharge from hospital as possible to ensure that experiences were still fresh in their minds. Participants were encouraged to talk freely and to tell stories using their own words. Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 minutes.

Table 1.

Interview guide.

|

Part 1

Pre-operative ● What was your perception of pain? ● Describe the preparation you had on pain management before you went to theatre What information did you receive when you first came back from theatre? Your experience Tell me about your experience on the management of your pain ● Describe the severity of your pain after the operation ● How would you describe the assessment of your pain after the operation? ● What information did you receive about the pain killers you were being given 1. Choice on the type of analgesia 2. Different routes depending on the degree of pain How often they can have the analgesia How would you describe the nurses’ attitude regarding your pain? Part 2 Satisfaction ● What does satisfaction mean to you? ● Describe what influenced how satisfied you were with the overall experience? ● What specifically did nurses do to respond to your pain that led to you feeling satisfied or dissatisfied (Whatever the patient responded) ● Was the nurse’s response to your pain the same or different from what you expected? ● What things do you think we should have done better? |

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by a Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) and the Hospital Research and Development department (R&D).

Analysis

Data collection and analysis ran concurrently to allow for the exploration of the key themes and to judge when data saturation occurred. All interviews were audio recorded. Data were analysed using Colaizzi’s method which helped to gain a sense of each participant’s pain experiences. Analysis was performed using the following steps:

Data were read and re-read to acquire general understandings of the narrative.

Significant statements pertaining to pain and satisfaction were extracted.

The formulated meanings were sorted into themes and clusters of themes.

Themes were clustered and validated with the original text to identify experiences common to participants. The first three steps were repeated for each participant in order to generate overarching themes. At this stage, any contradictory themes were investigated for their relevance to the topic.

Validation of the findings was then sought from the research participants to compare the researcher’s descriptive results with their experiences.

Finally, based on the participant’s feedback, the changes were incorporated into the themes representing the patients’ experience and satisfaction of post-operative pain management during their stay in hospital.

Rigour

Colaizzi’s approach is commonly used in phenomenological research. Bradbury-Jones et al.26 indicate that participant feedback is the key feature of phenomenology. This approach was used to enhance the credibility of the results. Colaizzi’s analysis provided the opportunity to return to the participants for validation of the results. Transcripts were sent to the participants allowing them to read through the data and analyses. They were able to provide feedback on the researchers’ interpretations of their responses, providing the researcher with a method of checking for inconsistencies, challenging the researchers’ assumptions and providing them with an opportunity to re-analyse their data.

Assumptions

The researcher’s assumptions were that patient satisfaction with pain management was linked to pain relief. However, Colaizzi’s method of analysis was used to ensure that the researcher views were challenged.

Results

Eleven participants agreed to participate in the study but data saturation was reached after interviewing eight participants. In order to ensure that there were no new themes emerging from the interviews, two more participants were interviewed. One participant was recruited (PM01) but withdrew from the study before being interviewed as they were still experiencing pain even after being discharged home (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| Identification no | Age | Sex | Type of op | Type of operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM02 | 26 | Male | Donor nephrectomy | Elective |

| PM03 | 70 | Male | Cystectomy | Elective |

| PM04 | 29 | Male | Adrenalectomy | Elective |

| PM05 | 58 | Female | Kidney transplant | Emergency |

| PM06 | 74 | Male | Kidney transplant | Emergency |

| PM07 | 58 | Male | Kidney transplant | Emergency |

| PM08 | 58 | Male | Kidney transplant | Elective |

| PM09 | 46 | Female | Kidney transplant | Emergency |

| PM10 | 31 | Female | Donor nephrectomy | Elective |

| PM11 | 42 | Female | Cystectomy | Elective |

All interviews were face to face and took place either in clinic or in the participant’s home. Transcripts and themes were sent out to all participants and nine responded. One participant (PM06) developed surgical complications after being interviewed and did not verify the data. As no changes were asked to be made to any of the first nine participants, it was considered safe to include the unverified data from this participant in the analysis. Three themes emerged: being informed, managing their pain and empathic caring (see Table 3 for themes and subthemes).

Table 3.

| Themes | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Being informed ● Not having sufficient information ● Well informed |

| 2 | Managing their pain ● Intensity of post-operative pain ● Using patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) for pain control |

| 3 | Empathic caring |

Being informed

Delivery of information was a very important aspect in the management of pain. Two distinct clusters were apparent in this theme, those who felt that they did not have enough knowledge about pain and those that felt that they received sufficient information.

Not having sufficient information

Some of the participants who felt ill-informed had more pain than they expected. They felt that information about pain should have been included in the pre-operative care phase. They wanted information about acceptable levels of pain and how it was going to be managed, as their expectation was that pain follows a predictable course that could be foreseen:

… Pre-op was over 3 days, bloods and there was this cycling test they had to do. It was all about how fit I was to have the operation, there was nothing really about pain … (PM03)

Some participants also felt that things were rushed. The duration between being called to hospital and having the operation was short in many cases. This was especially true of the patients undergoing emergency or transplantation surgery who had been on the waiting list and whose preparation for surgery had been delivered some time ago. The urgency of the situation meant they did not have enough time to speak to anybody about pain or think about what to expect post-operatively:

… I thought it was going to hurt a lot, I didn’t really have enough time to think about it to be honest. I was only called in at 11 am, I came in at 1 pm and by 4 pm I already gone to theatre. I was petrified … (PM05)

Delivery of inadequate information was thought to have carried on even in the post-operative period. For some patients, it was also evident that delivery of information on how to manage side effects in order to maximise the use of the patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was lacking because side effects such as nausea and drowsiness led them to reduce the amount of morphine they delivered to themselves:

… I kept pressing the button for the morphine. But I was feeling sick, it was making me feel sick … so I slept nearly the whole day … (PM10)

Some participants also highlighted how they struggled to manage the pain effectively due to the timing of information. When information was given to them in the immediate post-operative period, they were unable to process and comprehend the information:

… It was all a bit vague because I was a bit out of it but they did say that they will be giving me some Paracetamol and some small tablets called codeine … (PM03)

The content of the information about the operation was very important too. Participants expected to be given information about the details of the operation in order for them to understand how best to control their pain:

… I needed just a bit more information about the pain, what to expect, how to control it. I am having a lot of twinges but it would be good to know what they did inside. Obviously other people wouldn’t want to know, but I would have loved to know … (PM03)

Clear and detailed information about the pain therapy, pain assessment routines and the nature of the operation were considered important to help them to control their pain but many stated that this was lacking:

… I had a pain killer, it was quiet a strong pain killer, I don’t know what it is called … It’s given through the pump. You have to press it every 5 minutes or something … (PM04)

… I had the syringe first … They only told me to press it, I don’t even know what was in it … (PM05)

… I had the strong pain killer at night thinking it might make me sleep … (PM05)

Well informed

Some participants felt that they received sufficient information to help prepare them for the pain following their surgery:

… Before the operation, the doctor briefed me that I will be given a pain killer, I won’t feel much pain, that the pain killer will be my control … (PM02)

… yes, we discussed it. They told me what kind of things I will have, that I could be in hospital for a long time or I could be there for a short time … (PM10)

Some participants also indicated that the information on pain came from various sources. They indicated that they received helpful information from fellow patients who had the operations a few days earlier. They gave them detailed information about their experiences on the pain and how to use PCA. The information received was seen as helpful and did not necessarily mean that the participants complained about it not coming from the health professionals:

… the patient next to me was telling me to keep pressing it. He was advising me to kill the pain before it starts … (PM06)

Because of previous surgery and previous hospital admissions, some were well informed about what to expect and had the knowledge of what type of treatment they were going to receive:

… I have had 3 caesarean sections, I knew that I was going to have morphine and that it helps ease the pain … (PM10)

… I had been admitted before, I saw what happens from other patients. They tell you everything … (PM06)

However, knowing or not knowing what to expect did not seem to affect satisfaction with the management of the pain. The participants had different views on what they felt was important information on pain management. This indicated that information delivery about pain control should be tailored to individual patient needs.

Managing the pain

Intensity of post op pain

Patient’s pain experience was varied as well. Regular assessment of pain was done during medication rounds and when checking observations of vital signs. Pain was assessed using the Numeric Rating Score (NRS) of 0 as no pain at all and 10 as the worst possible pain. Participants talked about the intensity of their pain and how it was controlled. Some described the pain to be intense or unbearable during the first few hours after the operation:

… after the operation, I felt really unbearable pain; It made it hard to move to my side. Obviously I went into theatre feeling OK … it was unexpected, sharp, unbearable pain … (PM04)

… for the first 24 hours to be honest, I did feel pain … (PM10)

… They kept asking me that about this chart of 0-10 but there was only one day when I said it was 8, the rest were 2 s to me. That was ok … (PM03)

… at its worst, using a score 0-10, the pain score was probably an 8 on average the first few days and the pain just went down as time went on … (PM07)

Some patients revealed they did not experience enough pain to enable them to use the PCA. One patient described her experience to be a ‘breeze’ compared to previous operations:

… This time I had a morphine button, but when I came back from theatre, I never pressed it once. I wasn’t in pain, I was uncomfortable, but I wasn’t in so much pain for me to press that buzzer … (PM08)

Using PCA for pain control

In addition to the effect that education had on participants’ ability to use PCA, there were other elements of PCA that they identified as being important to their pain relief. Most participants received opioids through PCA and although the PCA machine may appeared easy to use, some patients struggled to get the relief they wanted in the initial post-operative period and therefore suffered more pain than they would have liked:

… At first I wasn’t pressing it that much and someone had to press it for me. I was quite tired and weak and I kept forgetting to press it … (PM04)

One patient described the ability to use the PCA was intuitive:

… it’s self-explanatory really. You are given the button and you can press it whenever you need it … (PM07)

Despite the fact that some patients had difficulty in using PCA, overall it was considered an effective method of managing their pain and all of the participants agreed that once they knew how to use it effectively, their pain was well controlled:

… Once I was able to do it, I pressed it every 5 minutes for over a period of two hours and it helped reduce the pain … (PM04)

… the pain was about 9-10 when I moved but because I kept pressing the pain killer, I kept it on 3-4 … (PM06)

Empathic caring

Apart from ensuring the delivery of information and the pain was well controlled, the general care of every patient was important in ensuring satisfaction. Carrying out regular pain assessment and ensuring that the PCA was being used properly indicated that the nurses cared:

… There was one nurse between me and another patient and they would check that I wasn’t in pain and that I was pressing the button … they always checked to make sure that I was pressing it and to check how much pain I had. So there was always somebody that was checking … (PM04)

Participants also indicated that despite being very busy, nurses cared for them, attended to their requests for pain control and also provided a friendly environment:

… they were nice to me and they were caring. Once I am feeling any pain, I called them and they came … (PM02)

… They were helpful and nice; there wasn’t anyone who wasn’t nice….The few times I asked for something, they would sort of address it … (PM04)

… the nurses were good; they always asked if you had any pain. They joked with you, it was fantastic, it was a much better experience than when I had the babies … (PM10)

Care did not just involve pain management, patients also indicated how nurses responded to other needs with dedication and empathy:

… when I went to the toilet, I had a problem with my catheter and the nurse sorted it out … I have never seen nurses as good as the ones who looked after me … staff are so busy because of staff shortages, but when I was in pain, she was with me all the time … (PM06)

Each patient was asked to describe whether they were satisfied with their care or not. Overall, participants expressed high satisfaction levels because their pain was well controlled and the nurses responded to them with empathy and a caring attitude. The way care was delivered and the attitude of the nurses had an impact on the patient’s recovery and on their decisions about satisfaction. Participants described the care they received as generally good and they highly valued nurses’ responses to their pain. Satisfaction was related to swift and timely nursing responses and the fact that nurses believed them when they said they were in pain. When asked about what influenced their satisfaction, participants said,

… my satisfaction was influenced by the fact that I wasn’t in pain at all … (PM05)

… It’s the fact that they had the medication readily available when I needed it and they encouraged me to take it, it was there if I needed it … (PM04)

… Because of the way they responded to me when I asked for pain killers, they gave me the pain killers and I had relief … the nurses were caring … (PM02)

… I was very satisfied, I have never seen nurses so good, I saw that the night staff were so busy because of staff shortages, but when I was in pain, they were with me all the time … (PM06)

However, one patient expressed satisfaction with the pain control but was not happy because they did not receive enough information:

… I was never left in pain, I would like to say I was satisfied but not happy because I wasn’t told enough. Just a bit more information about the pain, what to expect, how to control it would have been good … (PM03Discussion

This study demonstrates the need for a holistic approach to ensure satisfaction with pain management. The study reported inconsistency in the delivery of information during the pre- and the post-operative period. Some participants would have preferred to have received more pre-operative information. This is supported by Anderson et al.27 and Bennett et al.28 who found that participants wished to receive written and verbal information. Delivery of adequate and timely information has been found to help patients to develop an understanding of the expectations of pain relief post-operatively and enhance psychological preparation.29–33 The inability to give timely and adequate information had an effect on the ability to use the equipment such as PCA effectively. This is supported by literature revealing the effects of information on pain, education and patient preparation for PCA.27,34–37

In our study participants said that they got detailed information from fellow patients about how to reduce pain and how to use the PCA. This is consistent with a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies carried out by Dwarsward et al.38 to evaluate the self-management support from the perspective of patients with chronic conditions. Dwarsward et al.’s study revealed that health care professionals are valued for their knowledge, while a patient identifying themselves with someone in the same situation is a powerful experience because it helps them share experiences. However, the use of peer support in acute post-operative pain management is not common. In the current study, it is clear that they considered the information they received from the peers to be helpful. This is an important message as the information may not be accurate and we therefore suggest that health care professionals must be at the forefront of the information giving if we are to ensure accuracy. This has not been identified previously and future research may wish to explore this area.

Satisfaction was influenced by the way nurses interacted with patients and the effectiveness of the analgesia. The participants unmistakably articulated that regular pain assessment by nurses and the consequent attempt to control pain showed that they cared and this had an effect on satisfaction not only with pain control but with the overall care received. This ability of the nurses to express empathic caring through nursing interventions has become known as nursing therapeutics.39 Nursing therapeutics account for the nursing skill to develop therapeutic relationships while undertaking routine nursing tasks. Pain management is one area where the nurse can utilise the time with the patient to express care, compassion and empathy and these results suggest that this could have a significant effect on patient satisfaction. This is also consistent with a qualitative study carried out by Waters et al.33 in which empathy was identified to have a significant impact on patient satisfaction.

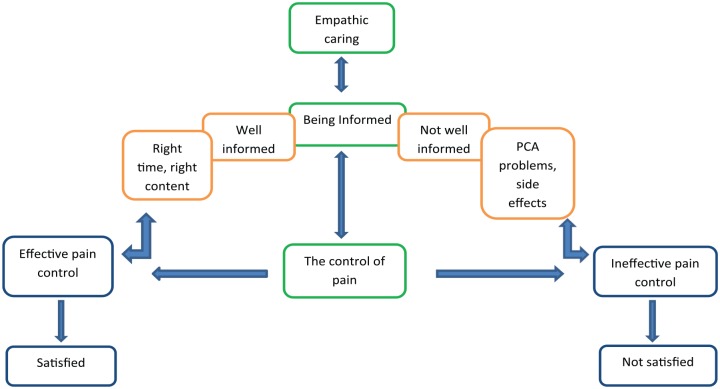

Our study has revealed that in order to achieve satisfaction with the management of pain, a holistic approach should include timely and adequate information delivery, nurses should have a caring attitude and pain should be well controlled. Figure 1 illustrates the main themes identified in this study which contribute to a holistic approach to satisfaction with pain management.

Figure 1.

Holistic approach to satisfaction with post-operative pain management.

Conclusion

Satisfaction with pain management is influenced by good communication and information transfer, appropriate pain management and an empathic presence throughout.

Limitations and recommendations

The sample was diverse in terms of patho-physiology, age, gender and other social factors which may have impacted on the pain and its management and influenced satisfaction levels. It would be sensible therefore to consider further research to explore any variations in homogeneous populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and The University of Manchester.

Footnotes

Author contributions: W.M.M. was involved in writing the literature review, developing the protocol, gaining ethical approval, patient recruitment and data analysis. C.R. was involved in writing the literature review, developing the protocol and data analysis. M.B. was involved in re-analysing the data. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: NRES Committee South East Coast – Brighton and Sussex (reference no: 13/LO1920). Hospital Research and Development department (R&D) (reference no: R03464).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article

Guarantor: W.M.M. is a guarantor.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

ORCID iD: Womba Musumadi Mubita  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6362-9883

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6362-9883

References

- 1. Ralaigh VS, Foot C. Getting the measure of quality: opportunities and challenges. London: The Kings Fund, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boerlage AA, Masman AD, Hagoort J, et al. Is pain assessment feasible as a performance indicator for Dutch nursing homes? A cross-sectional approach. Pain Manage Nurs 2013; 14(1): 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doherty S, Knott J, Bennetts S, et al. National project seeking to improve pain management in the emergency department setting: findings from the NHMRC-NICS national pain management initiative. Emerg Med Australas 2013; 25(2): 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saturno PJ, Martinez-Nicolas I, Robles-Garcia IS, et al. Development and pilot test of a new set of good practice indicators for chronic cancer pain management. Eur J Pain 2015; 19(1): 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stevens BJ, Yamada J, Estabrooks CA, et al. Pain in hospitalized children: effect of a multidimensional knowledge translation strategy on pain process and clinical outcomes. Pain 2014; 155(1): 60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gueant S, Taleb A, Borel-Kuhner J, et al. Quality of pain management in the emergency department: results of a multicentre prospective study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011; 28(2): 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weingart SN, Cleary A, Stuver SO, et al. Assessing the quality of pain care in ambulatory patients with advanced stage cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012; 43(6): 1072–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Eull D, et al. Pain outcomes in a US Children’s Hospital: a prospective cross-sectional survey. Hosp Pediatr 2015; 5(1): 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carr ECJ, Meredith P, Chumbley G, et al. Pain: a quality of care issue during patients’ admission to hospital. J Adv Nurs 2014; 70(6): 1391–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martinez KA, Snyder CF, Malin JL, et al. Patient-reported quality of care and pain severity in cancer. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(4): 875–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zoega S, Sveinsdottir H, Sigurdsson GH, et al. Quality pain management in the hospital setting from the patient’s perspective. Pain Pract 2015; 15(3): 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naveh P, Leshem R, Dror YF, et al. Pain severity, satisfaction with pain management, and patient-related barriers to pain management in patients with cancer in Israel. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011; 38(4): E305–E313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tornvall E, Wilhelmsson S. Quality of nursing care from the perspective of patients with leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2010; 19(9): 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosenberg RE, Klejmont L, Gallen M, et al. Making comfort count: using quality improvement to promote pediatric procedural pain management. Hosp Pediatr 2016; 6(6): 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maratt JD, Lee Y, Lyman S, et al. Predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30: 1142–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Savvas S, Gibson S. Pain management in residential aged care facilities. Austr Family Phys 2015; 44(4): 198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown AM. The role of nurses in pain and palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2013; 27: 300–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayes K, Gordon DB. Delivering quality pain management: the challenge for nurses. AORN J 2015; 101(3): 328–334, quiz 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haller G, Agoritsas T, Luthy CP, et al. Collaborative quality improvement to manage pain in acute care hospitals. Pain Med 2011; 12(1): 138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iyer SB, Schubert CJ, Schoettker PJ, et al. Use of quality-improvement methods to improve timeliness of analgesic delivery. Pediatrics 2011; 127(1): e219–e225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beck SL, Towsley GL, Berry PH, et al. Core aspects of satisfaction with pain management: cancer patients’ perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39(1): 100–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Welch SJ. Twenty years of patient satisfaction research applied to the emergency department: a qualitative review. Am J Med Qual 2010; 25(1): 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee TH. Zero pain is not the goal. JAMA 2016; 315: 1575–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Darzi L. High quality for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tongco DC. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethinobot Res Appl 2007; 5: 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bradbury-Jones C, Irvin F, Sanbrook S. Phenomenology and participant feedback: convention or contention. Nurs Res 2010; 17(2): 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anderson V, Otterstrom-Rydgerg E, Karlsson A. The importance of written and verbal information on pain treatment on patients undergoing surgical intervention. Pain Manage Nurs 2015; 16(5): 634–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bennett MI, Bagnall AM, Jose-Closs S. How effective are patient based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain. Pain 2009; 143(3): 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szyca R, Rosiek A, Nowakoska U, et al. Analysis of factors influencing patient satisfaction with hospital treatment at a surgical department. Pol Przegl Chir 2012; 84(3): 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fosnocht DE, Heaps ND, Swanson ER. Patient expectations for pain relief in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2004; 22(4): 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Halloran R, Grohn B, Worral L. Environmental factors that influence communication in patients with a communication disability in Acute Hospital stroke units: a qualitative metasynthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabilitat 2012; 93: S77–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ 2012; 345: e6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, et al. Identification of factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient clinic consultation: a qualitative study. Man Ther 2016; 25: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lemay CA, Lewis CG, Singh JA, et al. Receipt of pain management information pre-operatively is associated with improved functional gain after elective total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32: 1763–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hopayian K, Notley C. A systematic review of low back pain and sciatica patients’ expectations and experiences of health care. Spine J 2014; 14: 1769–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kazanowski MK. Pain (ed. Laccetti MS.). Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eid T, Bucknall T. Documenting and implementing evidence-based post-operative pain management in older patients with hip fractures. J Orthopaed Nurs 2008; 12: 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dwarsward J, Bakker E, van Staa A, et al. Self-management support from perspective of patients with chronic condition. A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Health Expectat 2015; 19: 194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Richardson C, Ovens E. Therapeutic opportunities when using vapocoolants for cannulation in children. Br J Nurs 2016; 25(14): S23–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]