Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Statutory rebates and preferred drug lists (PDLs) may result in differential use of biosimilars and generics between Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) and managed care organizations (MCOs), particularly for branded drugs with large price increases subject to large inflation rebates, which are not retained by MCOs.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the use of 2 biosimilar/generics of branded drugs whose list price tripled in 2008-2018 across states with only FFS Medicaid, with MCOs not subject to statewide PDLs, with MCOs subject to statewide PDLs, and with MCOs where drug benefits have been carved out.

METHODS:

Using 2018 Medicaid drug utilization data, we extracted reimbursement records in Q1-Q3 2018 for insulin glargine 100 IU/mL and glatiramer. We calculated the market share of the biosimilar insulin glargine and generic glatiramer among the corresponding drugs. We compared the market share of these products across 4 state groups: states with only FFS Medicaid, states with MCOs not subject to statewide PDLs for each drug, states with MCOs subject to PDLs, and states with MCOs where drug benefits have been carved out into FFS. We evaluated the correlation between state-level penetration of MCOs and share of biosimilar/generic products.

RESULTS:

Nationally, the market share of these biosimilar/specialty generics was higher among MCOs than FFS (60.5% vs. 3.7% for biosimilar insulin glargine; 59.4% vs. 5.7% for generic glatiramer; all P < 0.001). The market share of these products was highest in states where MCOs were not subject to statewide PDLs for these drugs (59.1% for biosimilar insulin glargine, 52.8% for glatiramer) compared with states with MCOs subject to PDLs (2.4%, 18.0%); states with only FFS Medicaid (0.9%, 1.7%); or states where drug benefits have been carved out of MCOs (0.0%, 1.0%; all P < 0.001). There was a significant correlation between state-level MCO penetration and share of generic/biosimilar products (R = 0.50 for biosimilar insulin glargine and 0.57 for glatiramer; all P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

For 2 drug classes with large price increases, use of biosimilars/generics was greater in MCOs than FFS Medicaid, specifically in states without PDL requirements for MCOs. These findings may reflect financial incentives for MCOs to use drugs with lower list prices because they do not benefit from statutory Medicaid rebates.

What is already known about this subject

Statutory rebates for drugs administered by Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) are collected by states and not MCOs.

This rebate structure incentivizes MCOs to use generics and biosimilars with lower list prices, while fee-for-service (FFS) programs may prefer branded products that, after rebates, have lower net costs than their corresponding biosimilars/generics.

States can favor the use of brands with lower net prices in Medicaid MCOs through the use of preferred drug lists.

What this study adds

For 2 examples of branded products with large list price increases, use of biosimilars/generics was substantially higher in Medicaid MCOs than FFS Medicaid, specifically in states where Medicaid MCOs were not subject to preferred drug list requirements.

The greater use of biosimilars and specialty generics in Medicaid MCOs may reflect financial incentives for MCOs to use drugs with lower list prices because they do not benefit from statutory Medicaid rebates.

Drugs covered by Medicaid are subject to statutory rebates that reduce drug spending. Before 2010, states would only receive rebates for drugs administered through fee-for-service (FFS) programs, which incentivized the administration of Medicaid drug benefits through FFS. Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, states also collect rebates for drugs covered under Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs).1 Since then, states have increasingly “carved-in” drug benefits, shifting their provision to MCOs.2

Rebates to states for drugs administered by MCOs create differential incentives for drug use between FFS and MCOs. Because MCOs do not benefit from statutory rebates (which are collected by states), they are incentivized to use generics and biosimilars with lower list prices. In contrast, FFS programs and state governments may prefer higher list price drugs that, after rebates, have lower net costs than their corresponding biosimilars/generics.4 To promote the use of branded products in MCOs, some states require them to follow statewide preferred drug lists (PDLs). Through PDLs, states can favor the use of brands with lower net prices (because of high rebates) by listing them as preferred medications and requiring prior authorizations for the biosimilar/generic versions.

Differential incentives between states and MCOs for using brand versus biosimilar/generics are accentuated when branded drugs have large price increases and thus are subject to large inflation rebates. Inflation rebates are one of the components of the Medicaid statutory rebate and penalize increases in drug prices above general inflation. In fact, inflation rebates account for more than half of total rebates for brand-name drugs in Medicaid.5 Thus, we selected 2 case studies of branded drugs whose list prices have tripled between 2008-2018 and that have biosimilar/generic versions available: insulin glargine and glatiramer acetate.6,7 Using these 2 examples, we evaluated how the use of a biosimilar and specialty generic differs between FFS Medicaid and MCOs and with statewide PDL requirements.

Methods

Data Source

Medicaid state drug utilization data reports the number of units, number of prescriptions, and total amount reimbursed by each state Medicaid agency for covered outpatient drugs. The data are made available by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services upon compilation of records submitted by each state Medicaid agency. Utilization data are provided at the National Drug Code and quarter level.

Study Sample

Using Medicaid state drug utilization data, we extracted FFS and MCO reimbursement records in quarters (Q) 1 through 3 of 2018 (most recent data at the time of analysis) for insulin glargine 100 IU/mL and glatiramer acetate. Combined, these products accounted for over $1.7 billion in Medicaid expenditure in 2017, around 2.7% of Medicaid expenditures in 2017 on outpatient prescription drugs.8 Formulations for insulin glargine 100 IU/mL included branded Lantus and “biosimilar” Basaglar (referred to hereafter as “biosimilar insulin glargine”). Although biosimilar insulin glargine was approved through the new drug pathway,9 it is a substitute for branded insulin glargine and is used in a similar fashion to a biosimilar.6 Glatiramer included 20 mg and 40 mg formulations for branded Copaxone, Glatopa, and generic glatiramer. Glatopa 20 mg was the first generic glatiramer to gain approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015. In 2017, a second generic of glatiramer 20 mg and generic glatiramer 40 mg were approved. Glatopa 40 mg was approved in February 2018 and thus was not available for the first month of the study period. Both Glatopa and generic glatiramer are AP rated, which means that they are considered therapeutically equivalent to branded Copaxone by the FDA.

Outcomes

Outcomes included the market share of biosimilar insulin glargine and generic glatiramer in Q1-Q3 2018 and were measured nationally for FFS and MCO records and for each state. The market share of biosimilar insulin glargine was defined as the proportion of insulin international units reimbursed for insulin glargine 100 IU/mL in each state that were accounted for by biosimilar insulin glargine. The market share of generic glatiramer was the proportion of daily dose equivalents (20 mg) reimbursed for glatiramer in each state that were accounted for by generic glatiramer or Glatopa.

Independent Variables

Using data from the Kaiser Family Foundation,3 we categorized states into 4 groups according to the provision of drug benefits under FFS or MCOs and the existence of PDLs for the drugs under study: (1) states with only FFS Medicaid, (2) states with active MCOs where drug benefits are carved in MCOs and where MCOs are not subject to statewide PDL requirements for each of the drugs, (3) states with active MCOs where drug benefits are carved in MCOs and where MCOs are subject to statewide PDLs, and (4) states with active MCOs where drug benefits are carved out of MCOs and directly provided by Medicaid state agencies. For states with some statewide PDL requirements,10 we reviewed their PDLs to determine if each of the 2 drugs under study were subject to the requirements in 2018 (Appendix, available in online article).

We also obtained the state-level penetration of MCOs from the Kaiser Family Foundation.11 We selected state-level penetration of MCOs as an independent variable because we are not aware of any data sources containing the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving drug benefits from an MCO in each state.

Statistical Analyses

We compared outcomes between FFS and MCOs nationally using the chi-square test and across the 4 state groups using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. We calculated the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the state-level penetration of MCOs in 2018 and the share of biosimilar/generic products. In sensitivity analyses, we calculated the correlation between the state-level penetration of MCOs in 2018 and the share of biosimilar/generic products after excluding states that have carved-out drug benefits from MCOs. Finally, we computed the correlations among the share of 2 products at the state level to understand if states that favored biosimilar insulin glargine also favored generic glatiramer. Medicaid suppresses state records for National Drug Code numbers with less than 11 prescriptions in a given quarter. To minimize the effect of this data suppression on our results, state-level analyses only included states with at least 100 prescriptions for insulin glargine or glatiramer in Q1-Q3 2018. While all states were included in analyses for insulin glargine, only 37 states were included in analyses for glatiramer.

Results

Nationally, the market share of biosimilar/generic products was higher among MCOs than FFS Medicaid (60.5% vs. 3.7% for biosimilar insulin glargine; 59.4% vs. 5.7% for generic glatiramer; all P < 0.001).

All but 12 states had active MCOs in 2018. In those states with active MCOs, only 4 states carved out the drug benefits.3 MCOs were subject to statewide PDL requirements for insulin glargine in 9 states and for glatiramer in 8 states (Appendix). All PDLs favored use of the branded versions of these products, with the exception of Arizona, which favored Glatopa in the case of the 40 mg glatiramer formulation.

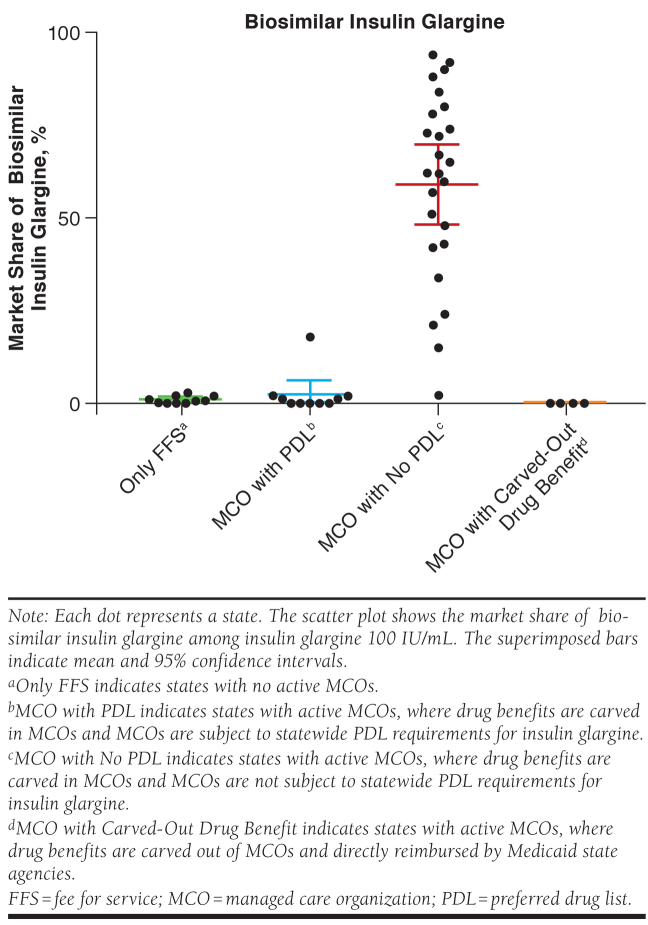

The market share of biosimilar/generic products was highest in states where MCOs were not subject to statewide PDL requirements for each of these drugs. For biosimilar insulin glargine, the market share was 59.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 48.6%-69.6%) in states where MCOs were not subject to statewide PDL requirements for insulin glargine, compared with 2.4% (95% CI = 0.0%-6.4%) for states with MCOs subject to PDLs; 0.9% (95 CI = 0.3%-1.6%) in states with only FFS Medicaid; and 0% in all states with drug benefits carved out of MCOs (P < 0.001; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Mean Medicaid Market Share of Biosimilar Insulin Glargine in 2018 at the State Level

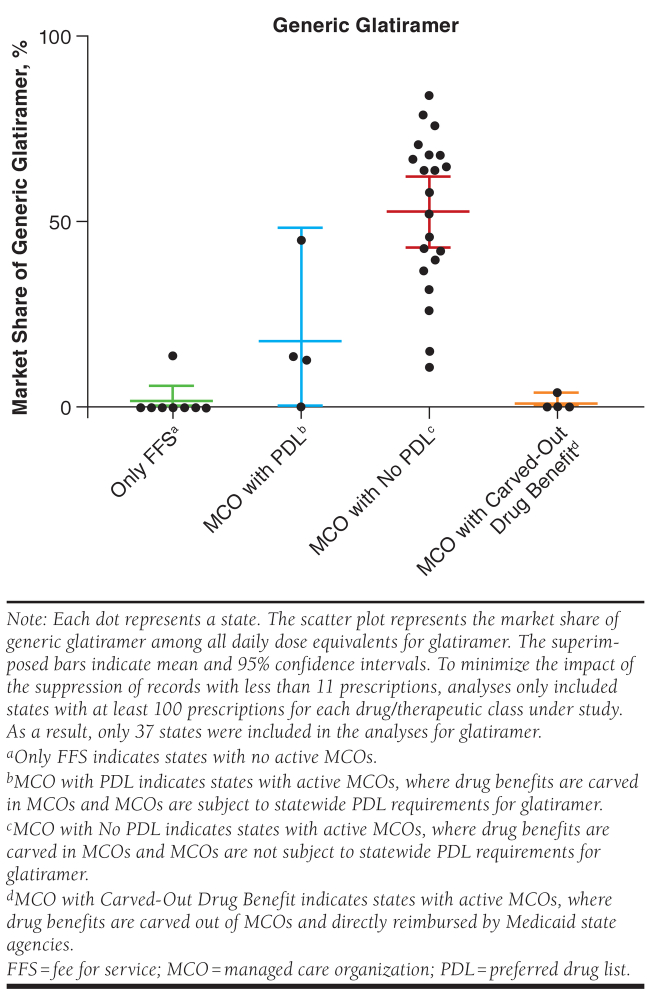

The market share of generic glatiramer was 52.8% (95% CI = 43.3%-62.2%) in states where MCOs were not subject to statewide PDL requirements for glatiramer, compared with 18.0% (95% CI = 0%-48.4) in states with MCOs subject to PDLs; 1.7% (95% CI = 0%-5.9%) in states with only FFS Medicaid; and 1.0% (95% CI = 0%-4.2%) in states with drug benefits carved out of MCOs (P < 0.001; Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mean Medicaid Market Share of Generic Glatiramer in 2018 at the State Level

The market share of biosimilar/generic products was higher among states with higher penetration of MCOs, with correlation coefficient (R) = 0.504 for biosimilar insulin glargine (Figure 3) and R = 0.569 for generic glatiramer (Figure 4; all P < 0.001). After excluding states that have carved-out drug benefits from MCOs, the correlation coefficients increased to R = 0.567 for biosimilar insulin glargine and R = 0.689 for generic glatiramer (all P < 0.001). States with higher use of biosimilar insulin glargine also had higher generic glatiramer use (Figure 5), with R = 0.900 (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3.

Correlation Between Penetration of Medicaid MCOs and Market Share of Biosimilar Insulin Glargine at the State Level

FIGURE 4.

Correlation Between Penetration of Medicaid MCOs and Market Share of Generic Glatiramer at the State Level

FIGURE 5.

Correlation Between Market Share of Biosimilar Insulin Glargine and of Generic Glatiramer at the State Level

Discussion

For 2 examples of branded products whose list prices tripled in 2008-2018,6,7 use of biosimilars/generics was substantially higher in MCOs than FFS Medicaid, specifically in states where MCOs were not subject to statewide PDL requirements. We observed a moderate correlation between the penetration of MCOs and market share of these products, and states with higher use of biosimilar insulin glargine also had higher use of the specialty generic for glatiramer acetate.

While previous research has compared generic use between MCOs and FFS Medicaid,2,12 this study is the first to examine differences in biosimilar and generic use for drugs with large increases in prices. As more of these complex drugs reach the market and their prices increase, they will provide increasingly larger rebates to states. Because these rebates are collected by states and not MCOs, they incentivize MCOs to use biosimilars and generics with lower list prices, while incentivizing FFS programs to continue to use the brands. When list prices rise quickly, the inflation rebate can drive the discount to 100% of the drug’s average manufacturer price (over 15% of branded drugs hit the Medicaid rebate cap in 2017).13,14 Thus, the use of branded products with lower net prices lowers costs to the state, while it increases spending by MCOs and, consequently, capitated rates.

Our results are particularly relevant because these consequences of the current rebate structure will augment, if the Medicaid rebate cap is eliminated, as recently proposed.15 A larger inflation rebate will make it more attractive for states to continue use of the branded drug. Moreover, states are increasingly implementing PDL requirements for MCOs,10 which will further increase differences in the use of biosimilar and specialty generic products across states. As rebates rise and more states adopt statewide PDLs, it will be important to assess to what extent the higher spending by MCOs that use brands is compensated through the capitated rates that states pay managed care plans. In addition, future research should assess the effects of this differential use of biosimilars and specialty generics on medication access by Medicaid beneficiaries.

Limitations

Our analysis has some limitations to consider. First, MCOs, especially those not subject to statewide PDLs, can negotiate confidential supplemental rebates that could not be accounted for in this analysis. Second, the correlations we measured are associations only and may be explained by unmeasured factors; however, we were unable to identify other factors that could explain such large differences in biosimilar/generic use across states for these drugs. Finally, our results based on 2 drugs may not generalize to other medications. We focused on these examples because their list prices tripled in 2008-2018, so they were subject to large inflation rebates; they had a biosimilar or a generic version available; and their use was high enough to observe use in most states after the suppression of records with less than 11 prescriptions. We were not able to identify any other medications in this time period that fit these criteria.

Conclusions

For insulin glargine and glatiramer, use of new biosimilars/generics was substantially greater in MCOs than FFS Medicaid, specifically in states without statewide PDL requirements. The presence of Medicaid statutory rebates and their strong financial incentives likely played a major role in this differential use, with potential effects on patients.

APPENDIX. Status of Selected Biosimilars/Specialty Generics and Branded Versions in Statewider Preferred Drug Lists

| State | Insulin Glargine | Glatiramer Acetate |

|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Lantus preferred | Copaxone preferred for 20 mg, Glatopa preferred for 40 mg |

| Delaware | Lantus preferred | Copaxone preferred |

| Florida | Lantus preferred | Copaxone preferred |

| Iowa | Lantus preferred | Copaxone preferred |

| Kansas | Lantus preferred | Therapeutic class not included in PDL |

| Massachusetts | Therapeutic class not included in PDL | Therapeutic class not included in PDL |

| Minnesota | Therapeutic class not included in PDL | Therapeutic class not included in PDL |

| Mississippi | Lantus preferred | Copaxone 20 mg preferred |

| North Dakota | Lantus preferred | Copaxone 20 mg preferred |

| Nebraska | Lantus preferred | Copaxone 20 mg preferred |

| Oregon | Therapeutic class not included in PDL | Therapeutic class not included in PDL |

| Texas | Lantus preferred | Therapeutic class not included in PDL |

| Washington | Lantus preferred | Copaxone preferred |

Note: For analyses, we considered that MCOs in all states listed in this table were subject to statewide PDL requirements for insulin glargine 100 IU/mL, except for Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Oregon. MCOs in all states listed here except for Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oregon, Kansas, and Texas were considered to be subject to statewide PDL requirements for glatiramer.

MCO = managed care organization; PDL = preferred drug list.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services. Medicaid drug rebate program notice. July 21, 2016. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Prescription-Drugs/Downloads/Rx-Releases/State-Releases/state-rel-177.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dranove D, Ody C, Starc A. A dose of managed care: controlling drug spending in Medicaid. NBER Working Paper No. 23956. October 2017. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w23956. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gifford K, Ellis E, Edwards BC, et al. Medicaid moving ahead in uncertain times: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2017 and 2018. October 2017. Available at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Results-from-a-50-State-Medicaid-Budget-Survey-for-State-Fiscal-Years-2017-and-2018. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services. MassHealth brand name preferred over generic drug list. 2019. Available at: https://masshealthdruglist.ehs.state.ma.us/MHDL/pubdownloadpdfwelcome.do;jsessionid=1ED751D80A266F2D94CCBCD987085BF3?docId=246&fileType=PDF. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levinson D. Medicaid rebates for brand-name drugs exceeded Part D rebates by a substantial margin. OEI-03-13-00650. April 2015. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-03-13-00650.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez I, Good CB, Shrank WH, Gellad W F. Trends in Medicaid prices, market share, and spending on long-acting insulins, 2006-2018. JAMA. 2019;321(16):1627-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez I. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D. JAMA Neurol. August 26, 2019. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicaid drug spending trends. 2019. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Medicaid-Drug-Spending-Trends.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Approval package for Basaglar. 2015. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/205692Orig1s000Approv.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gifford K, Ellis E, Edwards BC, et al. States focus on quality and outcomes amid waiver changes: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2018 and 2019. October 25, 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/states-focus-on-quality-and-outcomes-amid-waiver-changes-pharmacy-and-opioid-strategies/. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser Family Foundation. Share of Medicaid population covered under different delivery systems. 2019. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/share-of-medicaid-population-covered-under-different-delivery-systems/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Lewin Group. An evaluation of Medicaid savings from Pennsylvania’s HealthChoices Program. May 2011. Available at: http://www.lewin.com/content/dam/Lewin/Resources/Site_Sections/Publications/MedicaidSavingsPAHealthChoices.pdf. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickson S. Estimates of the number of brand-name drugs affected by the Medicaid rebate cap in 2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):437-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roubein R. A critical deadline on Montana’s Medicaid expansion. Politico Pulse. April 15, 2019. Available at: https://www.politico.com/newsletters/politico-pulse/2019/04/15/a-critical-deadline-on-montanas-medicaid-expansion-583691. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed T. MACPAC calls for Congress to eliminate the drug rebate cap. FierceHealthcare. April 12, 2019. Available at: https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/hospitals-health-systems/macpac-calls-for-congress-to-eliminate-drug-rebate-cap. Accessed December 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]