Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are considered to serve essential roles in podocyte apoptosis, and to be critical in the development of diabetic nephropathy (DN). Activation of the Notch signaling pathway has been demonstrated to serve an important role in DN development; however, its regulatory mechanisms are not fully understood. The present study used a high glucose (HG)-induced in vitro apoptosis model using mouse podocytes. Expression levels of miR-145-5p and its target, Notch1, and other key factors involved in the apoptosis signaling pathway were detected and measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and western blotting. A luciferase reporter assay was performed to elucidate the miRNA-target interactions. The functions of miR-145-5p in apoptosis were detected using flow cytometry and TUNEL staining. The present study demonstrated that in HG conditions, miR-145-5p overexpression inhibited Notch1, Notch intracellular domain, Hes1 and Hey1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels. Notch1 was identified as a direct target of miR-145-5p. Furthermore, cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax levels were reduced significantly by miR-145-5p overexpression. These results indicate that miR-145-5p overexpression inhibited the Notch signaling pathway and podocyte lesions induced by HG. In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested that miR-145-5p may be a regulator of DN. Additionally, miR-145-5p inhibited HG-induced apoptosis by directly targeting Notch1 and dysregulating apoptotic factors, including cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax. The results of the present study provided evidence that miR-145-5p may offer a novel approach for the treatment of DN.

Keywords: high glucose, microRNA-145-5p, apoptosis, Notch signaling pathway

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a risk factor for end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular diseases, which are associated with high morbidity and mortality (1). Microvascular lesions may lead to impaired blood flow and contribute to damage to the target organs (2). Therefore, it is important to establish a novel therapeutic method for patients with DN and improve their prognosis.

Podocytes act as the most important barrier to urinary protein loss through the formation and maintenance of foot processes and interposed slit-diaphragms (3). Podocytes serve an important role in DN. A multitude of factors, including oxidative stress and inflammatory response in diabetes cause abnormalities in podocytes that limit their ability to self-repair and regenerate (4,5). Furthermore, diabetes may cause podocyte foot process detachment, hypertrophy and loss (4,5). Therefore, podocyte injury is widely considered as a key factor in determining the prognosis of DN (4,5).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are endogenous small non-coding RNAs with a length of 19–25 nucleotides, and are involved in various cellular processes (6–8). They are reported to function by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) of target genes, resulting in the degradation of mRNAs (9–11). Recent studies have demonstrated that miRNAs targeting podocyte-associated genes may be potential candidates for antiapoptotic therapies for DN (12,13). A previous study demonstrated that miR-25 inhibited high glucose (HG)-induced apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells by reducing the production of reactive oxygen species, and decreasing the activity and cleavage of caspase-3 (14). Another study reported that the inhibition of miR-377 expression ameliorated inflammation and improved insulin sensitivity (15). These results suggest that miRNAs serve important roles in regulating the DN process. Therefore, further investigations regarding the influence of miRNAs and their targets are a promising perspective. A previous study has demonstrated that miR-145-5p is enriched in diabetic patients, and may represent a novel candidate biomarker (16).

The Notch signaling pathway is associated with vascular defects, including abnormal structure and leakiness (17,18). Under normal circumstances, activation of Notch receptors releases a signal in the form of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). When NICD enters the nucleus, its binding to chorionic somatomammotropin hormone like 1 may trigger an allosteric alteration and, later, NICD transfers into the nucleus and activates the gene transcription of hes family bHLH transcription factor 1 (Hes1) and hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1 (Hey1) (19), which are associated with cell differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis (20,21).

Based on the aforementioned information, the present study aimed to investigate the role of miR-145-5p and Notch1 in DN. Furthermore, their interactions and potential mechanism in HG-induced podocytes was studied. This may provide a theoretical basis for clinical treatment.

Materials and methods

Podocyte cell culture and treatment groups

Mouse podocytes (cat. no. M1710) and all cell culture media, FBS and other supplements were purchased from ScienCell Research Laboratories, Inc. Mouse podocytes were cultured according to the manufacturer's protocols as follows: Mouse podocytes were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 10 U/ml mouse recombinant γ-interferon (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) with 5% CO2 at 33°C. Subsequently, cells were cultured in fresh DMEM-F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 10–14 days (22). Prior to the functional experiments, expression levels of the podocyte differentiation marker synaptopodin were detected by immunofluorescence staining (data not shown). Subsequently, cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO2 containing 25 mM glucose (HG) or 5 mM glucose [normal glucose (NG)] for 12, 24, 48 and 72 h. The 293T cells (Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of Chinese Academy of Sciences) were cultured as described previously (23).

Lipofectamine transfection

miR-145-5p mimics, miR-145-5p inhibitor and scrambled controls were applied to create miR-145-5p overexpression and knockdown in podocytes. Lipofectamine® 2000 reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used for cell transfection. Briefly, Lipofectamine® 2000 was diluted and the podocytes were then added to the diluted solution. The solution was added into 6-well plates and incubated for 6 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Subsequently, 10 nM miRNA duplexes and miRNA transfection reagent were mixed and added to 100 ml miRNA transfection medium for 45 min at 20°C. Finally, the medium was changed to conventional medium and cultured for a further 48 h. After 48 h of transfection, the total RNA and protein were extracted from the cells and tested using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively.

TUNEL staining

Cell apoptosis was examined by TUNEL staining using a DeadEnd™ fluorometric TUNEL system kit (Promega Corporation), according to the manufacturer's protocol as previously described (24). Cells (5×104/well) were first washed using saline. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% neutral formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 15 min. Then, the slides were washed three times with PBS, and with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min at room temperature. After treatment with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, the cell slides were immersed into 100 ml equilibration buffer at room temperature (22°C) for 15 min, followed by incubation in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature. After a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase buffer pre-incubation for 10 min at room temperature, slides were incubated in the TUNEL reaction mixture for 60 min at 37°C and sealed using fluorescent mounting medium (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Fluorescence microscopy was used for detection of the fluorescence of apoptotic cells and data analysis. The size (mm2) of each area containing TUNEL-positive cells was measured with a micro ruler at ×200 magnification. After the measurement, the number of apoptotic cells was counted by two technicians in three high-power fields (magnification, ×400) under a light microscope.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

To detect and compare gene expression, RT-qPCR was performed. Total RNA was extracted from podocytes using TRIzol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Then, the RNA concentration was determined by measuring the absorbance (A) at 260 and 280 nm, and a A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 indicated acceptable purity. Briefly, 2 µg total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara Bio, Inc.) using the temperature protocol of 42°C for 60 min followed by 70°C for 5 min. RT-qPCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system thermocycler using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara Bio, Inc.). The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 2 min and a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. The primers used for amplification are shown in Table I, and were synthesized by Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The results were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCq method (25). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis.

| Complementary DNA | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| miR-145-5p | GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATCC | TCGCTTCGGCAGCACATAT |

| NICD | GTGGATGACCTAGGCAAGTCG | GTCTCCTCCTTGTTGTTCTGC |

| Bcl-2 | CGGAGGCTGGGATGCCTTTG | TTTGGGGCAGGCATGTTGAC |

| Bax | GCCCTTTTGCTTCAGGGTTT | TCCAATGTCCAGCCTTTG |

| Caspase-3 | TACAGGAACAGACCATAATACC | AGACCAGTGCTCACAAGGAAC |

| Hes1 | CACGACACCGGACAAACCA | GCCGGGAGCTATCTTTCTTAAGTG |

| Hey1 | AAGACGGAGAGGCATCATCGAG | CAGATCCCTGCTTCTCAAAGGCAC |

| U6 | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA | AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT |

| GAPDH | ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG | GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC |

Hes1, hes family bHLH transcription factor 1; Hey1, hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1; miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; NICD, Notch intracellular domain.

For measurement of miR-145-5p expression, the Taqman™ MicroRNA Reverse Transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and Taqman® Universal Master Mix II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used for reverse transcription and RT-qPCR, respectively. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 2 min and a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. U6 was used as an internal control.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was conducted as previously described (26). Briefly, podocytes were washed with saline and harvested by scraping the culture dishes followed by RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The buffer was cooled for 40 min in an ice bath and centrifuged for 20 min at 1,000 × g at room temperature. After the supernatant was discarded, the protein concentration was assessed using a Bicinchoninic Acid protein assay. Then, 30 µg/lane proteins were transferred to 10% PVDF membranes, and the membranes were blocked by treatment with 5% non-fat milk for 2 h at 37°C. After rinsing, the membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies. The primary polyclonal antibodies were as follows: NICD (1:200 dilution; cat. no. ab8925; Abcam); Hes1 (1:500 dilution; cat. no. ab71559; Abcam), Hey1 (1:500 dilution; cat. no. ab22614; Abcam); cleaved caspase-3 (1:3,000 dilution; cat. no. ab49822; Abcam), Bcl-2 (1:3,000 dilution; cat. no. ab692; Abcam) and Bax (1:3,000 dilution; cat. no. ab77566; Abcam) and GAPDH (loading control; 1:3,000 dilution; cat. no ab9485; Abcam). After washing with Tris buffer solution, secondary rabbit anti-primary IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:1,500; cat. no. ab6721 Abcam). was added to the solutions and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Binding was detected using Western Lightning™ Plus ECL reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc). Densitometric analysis was performed for semi-quantification of the blots using ImageJ software (version 1.8; National Institutes of Health).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was conducted as previously described (27). Briefly, podocytes (5×104/well) were incubated with fully-supplemented RPMI-1640 for 24 h following transfection with miR-145-5p mimics, inhibitor or scrambled control. Subsequently, for apoptosis measurements, podocytes were collected, washed with PBS, resuspended in 100 µl 1X binding buffer and stained with 5 µl Annexin V and 5 µl propidium iodide (PI; Becton, Dickinson and Company) at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Fixed cells (1×104/well) were rehydrated in PBS for 10 min and subjected to PI/RNase (10 µg/ml) staining at 4°C for 20 min A flow cytometer was utilized to evaluate the apoptotic levels and cell cycle distribution in each sample according to the manufacturer's protocol. The results were analyzed using a BD FACScan™ flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva™ software (version 1.2; BD Biosciences).

Luciferase reporter assay

Potential target mRNAs of miR-145-5p were searched for using TargetScan (version 7.2; http://www.targetscan.org/) (28), miRanda (version 1.0; http://www.microrna.org) and miRDB (version 1.0; http://mirdb.org/) (29). For the luciferase reporter assay, a fragment from the 3′-UTR of Notch1, which was predicted to contain a binding sequence for miR-145-5p, was amplified using the pGL3 luciferase promoter vector (Promega Corporation) Then, 1×105 293 cells were cultured and transfected with the wild-type or mutated 3′-UTR fragments and miR-145-5p inhibitor or mimic using Lipofectamine® 2000. After culturing for 48 h, the cells were harvested and lysed. Luciferase activity was measured using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega Corporation). Relative luciferase activity was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase activity.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated three times and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.1 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are expressed as the means ± SD. Statistical analyses were carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Expression levels of miR-145-5p are decreased in HG-induced podocytes

First, in order to investigate the role of miR-145-5p in HG-treated podocytes, the expression levels of miR-145-5p were detected using RT-qPCR following incubation with 25 mM glucose for 12, 24, 48 and 72 h. As shown in Fig. 1, the expression levels of miR-145-5p were significantly decreased in HG-treated podocytes from 24 h onwards. These data indicate that miR-145-5p serves a critical role in HG-stimulated podocytes.

Figure 1.

Expression levels of miR-145-5p are decreased in HG podocytes. Podocytes were incubated with 5 mM (NG group) and 25 mM (HG group) glucose for different time periods (12, 24, 48 and 72 h). The expression levels of miR-145-5p were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and as the fold change relative to the control group (n=3). **P<0.01 vs. NG. miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose.

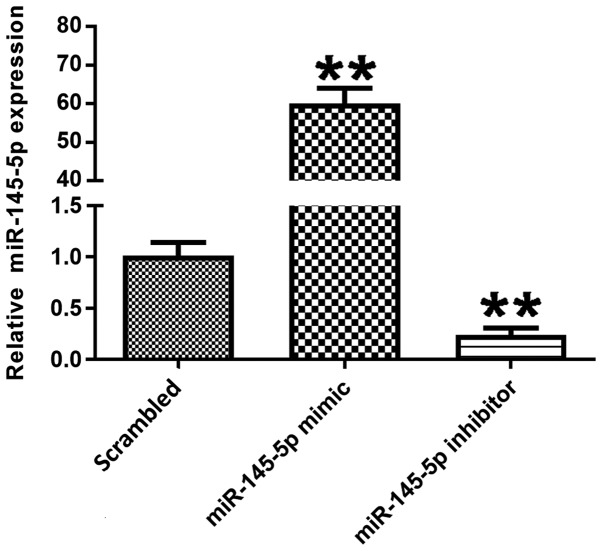

miR-145-5p expression is successfully changed following transfection with miR-145-5p mimic or inhibitor

miR-145-5p expression was detected in different transfection groups. Podocytes were transfected with scrambled control, miR-145-5p mimic or miR-145-5p inhibitor for 48 h. Following transfection, the expression levels of miR-145-5p were detected via RT-qPCR. Fig. 2 shows that in the miR-145-5p overexpression group, transfected with miR-145-5p mimic, the expression levels of miR-145-5p were significantly higher compared with those in the scrambled control group. Additionally, in the miR-145-5p knockdown group, transfected with miR-145-5p inhibitor, miR-145-5p expression was significantly decreased in the podocytes compared with control. These data indicate that the transfection was successful.

Figure 2.

Determination of transfection efficiency in different groups. The expression of miR-145-5p was measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and as the fold change relative to the control group (n=3). **P<0.01 vs. the scrambled control. miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p.

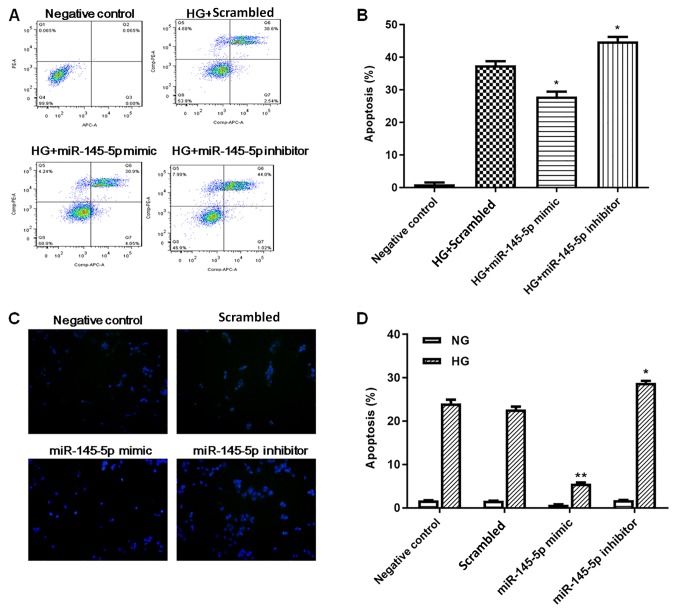

Overexpression of miR-145 inhibits HG-induced apoptosis in podocytes

Podocyte apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry and TUNEL staining. In flow cytometry assays (Fig. 3A and B), HG-treated podocytes exhibited a significant increase in apoptotic cells compared with the negative control group. Under HG conditions, the percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly decreased in the miR-145-5p overexpression group compared with the scrambled control group, whereas the percentage of apoptotic cells in the miR-145-5p inhibitor group was significantly increased. In the TUNEL staining assay (Fig. 3C and D), the numbers of apoptotic cells were markedly increased in the HG-induced podocytes compared with NG podocytes. Under HG conditions, the number of apoptotic cells was significantly lower in the miR-145-5p mimic group compared with that in the scrambled control group; however, in the miR-145-5p inhibitor group, the number of apoptotic cells was significantly higher than that in the scrambled control group. Overall, these functional experiments demonstrated that miR-145-5p attenuated HG-induced cell apoptosis in podocytes.

Figure 3.

Effect of miR-145-5p on HG-induced podocyte apoptosis. (A) Podocyte apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry following HG (25 mM) stimulation for 48 h. Podocytes treated with NG (5 mM) were used as the negative control group. (B) Quantification of the percentage of apoptotic cells. (C) TUNEL staining of apoptotic podocytes. Magnification, ×200. (D) Percentages of apoptotic cells identified by TUNEL staining. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and as the fold change relative to the control group (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. the scrambled control. HG, high glucose; miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; NG, normal glucose.

miR-145-5p is a direct target of Notch1 in podocytes

To identify the further mechanisms, the present study first screened the putative target of miR-145-5p using three different bioinformatic algorithms (Fig. 4A). Notch1, which is a vital factor in the Notch signaling pathway and serves an important role in podocyte apoptosis, was identified as a potential target by all three (Fig. 4B). To confirm the association between miR-145-5p and Notch1, luciferase reporter constructs containing wild-type and mutated forms of a putative miR-145-5p binding site were constructed. Subsequently, wild-type pGL3-Notch1 3′-UTR or pGL3-Notch1-Mut-3′-UTR was co-transfected with miR-145-5p mimic or inhibitor into 293T cells. When cells were transfected with the wild-type pGL3-Notch1 3′-UTR, the co-transfection of miR-145-5p mimic inhibited luciferase activity whereas the co-transfection of miR-145-5p inhibitor exhibited the opposite effect. By contrast, co-transfection of miR-145-5p mimic or inhibitor with pGL3-Notch1-Mut-3′-UTR containing mutations in the predicted consensus sequences for miR-145-5p exhibited no apparent effect on luciferase activity (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, to identify whether miR-145-5p regulated the expression levels of Notch1 in podocytes, the mRNA levels of Notch1 in different groups were detected. The results confirmed that the mRNA levels of Notch1 were decreased in podocytes transfected with miR-145-5p mimics and increased in podocytes transfected with miR-145-5p inhibitors compared with those in the scrambled control group (Fig. 4D). These findings suggest that Notch1 is a direct target of miR-145-5p.

Figure 4.

miR-145-5p is a direct target of Notch1 in podocytes. (A) Venn diagram showing the 267 genes identified as potential targets of miR-145-5p using three prediction tools (B) Predicted binding sequences of miR-145-5p with the 3′-UTR of Notch1. (C) Relative luciferase activity was analyzed after WT or mut 3′-UTR reporter plasmids were co-transfected with miR-145-5p mimic or miR-145-5p inhibitor in podocytes. (D) Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR detection of Notch1 mRNA expression in podocytes transfected with miR-145-5p mimic or miR-145-5p inhibitor. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and shown as the fold change relative to the control group (n=3). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. the respective NC or scrambled control. HG, high glucose; miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; NC, negative control; MUT, mutant; NG, normal glucose; UTR, untranslated region; WT, wild-type.

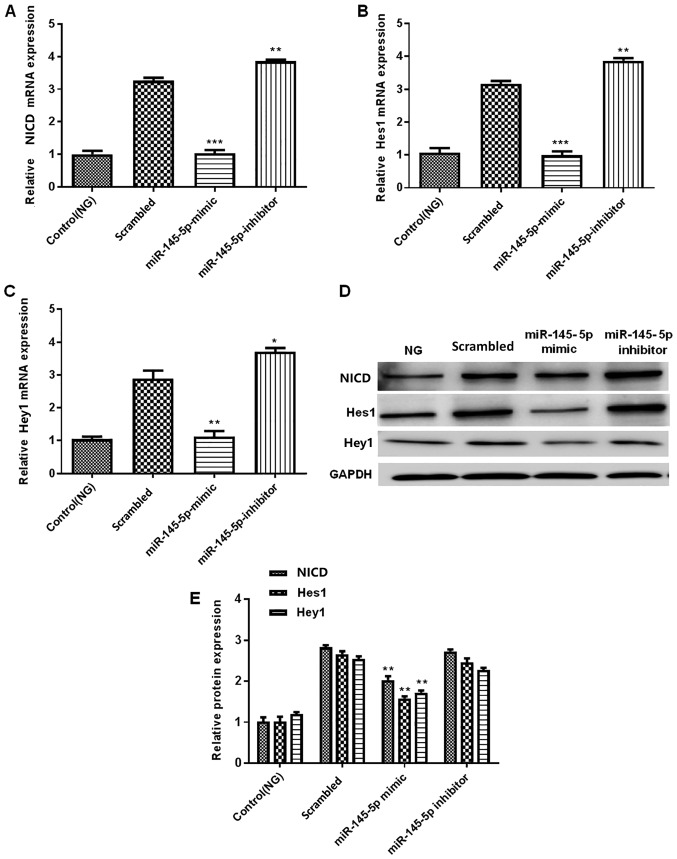

Overexpression of miR-145-5p suppresses HG-induced activation of the Notch signaling pathway

The Notch signaling pathway contains numerous effectors, including NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 (30–32). To further determine the effect of miR-145-5p on the Notch signaling pathway, the present study detected the expression levels of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1, which are important downstream factors of this signaling pathway. The protein and mRNA expression levels of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 were measured by western blotting and RT-qPCR, respectively. The results demonstrated that in the miR-145-5p mimic group, the protein and mRNA expression levels of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 were significantly decreased compared with those in the scrambled control group, whereas those in the miR-145-5p inhibitor group were significantly increased (Fig. 5). Overall, the results suggest that overexpression of miR-145-5p suppressed the HG-induced activation of the Notch signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of miR-145-5p suppresses the HG-induced activation of the Notch signaling pathway. (A-C) RT-qPCR detection of (A) NICD, (B) Hes1 and (C) Hey1 mRNA expression in control (NG) and transfected podocytes under HG conditions. (D) Western blotting detection of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 protein expression in podocytes. (E) Semi-quantification of the protein levels of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and shown as the fold change relative to the control group (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the scrambled control. miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; HG, high glucose; NG, normal glucose; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; NICD, intracellular domain of Notch; Hes1, hes family bHLH transcription factor 1; Hey1, hes related family bHLH transcription factor with YRPW motif 1.

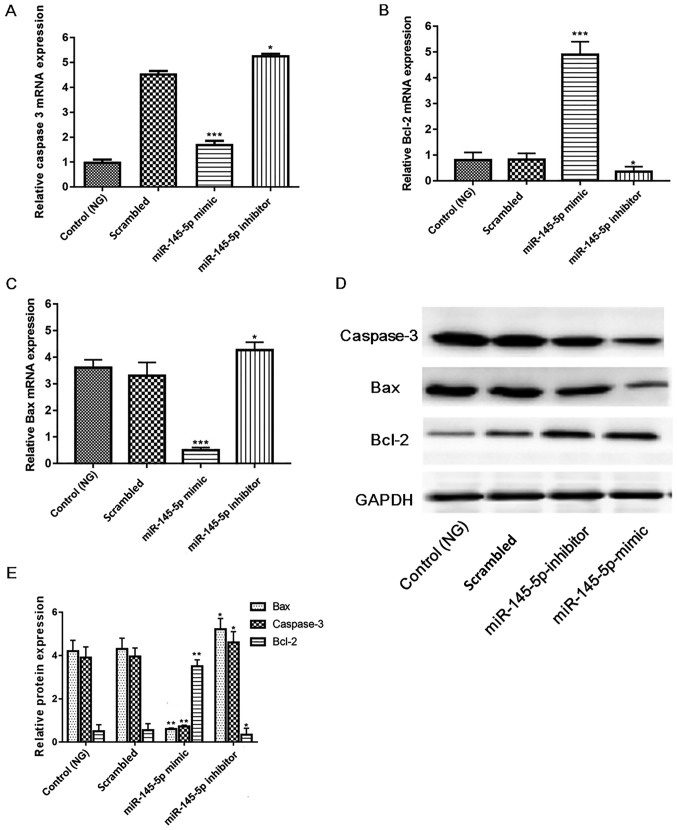

Overexpression of miR-145-5p inhibits apoptotic pathways

Since numerous key factors, including cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax serve pivotal roles in apoptosis (33–35), the present study investigated whether their activity is increased in HG-induced podocytes. Protein and mRNA expression were measured in different groups of HG-induced podocytes. Fig. 6 shows that in the miR-145-5p overexpression group, the mRNA and protein expression levels of cleaved caspase-3 and Bax were significantly decreased, and those of Bcl-2 were significantly increased compared with those in the scrambled control group. Furthermore, opposite results were observed in the miR-145-5p inhibitor group. These results indicate that miR-145-5p overexpression suppressed the apoptosis of podocytes in under HG conditions via the inhibition of apoptotic signaling.

Figure 6.

mRNA and protein expression levels of caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax in podocytes. (A-C) RT-qPCR detection of (A) caspase-3, (B) Bcl-2 and (C) Bax mRNA expression in podocytes. (D) Western blotting detection of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax protein levels in podocytes transfected with miR-145-5p mimics and inhibitors. (E) Semi-quantification of protein levels of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and shown as the fold change relative to the control group. GAPDH was used as an internal control (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. the scrambled control. miR-145-5p, microRNA-145-5p; NG, normal glucose; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

Discussion

DN is one of the most common complications of diabetes mellitus and may lead to end-stage renal disease (1). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that podocyte apoptosis serves an essential role in the pathogenesis of proteinuria and deteriorated renal function in DN (4,36–38). Previous studies have suggested that the Notch signaling pathway serves a pivotal role in podocyte apoptosis, which is regulated by various downstream factors, including NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 (34,36). For example, the Notch signaling pathway is mediated via the release and translocation of NICD into the nucleus, where NICD directly functions as a transcriptional coactivator (39). In the pathological process of DN, high blood glucose and hemodynamic alterations induce increased expression of Jagged1 ligand and Notch1 receptor of the Notch signaling pathway, resulting in a change in the receptor structure (39). The enzyme g-secretase induces podocytes to release NICD1, the active form of Notch1, and activates the downstream genes Hes1 and Hey1 (36,38). Notably, a previous study found that ubiquitination-dependent coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 degradation in podocytes promotes podocyte apoptosis via Notch1 activation in DN (34).

A series of studies has focused on the crosstalk between miRNA and the Notch signaling pathway in podocytes (40,41). For example, a previous study have demonstrated that miRNA-34 directly interacts with the 3′-UTRs of Notch1 and Jagged1, which is critical for Notch signaling pathway activation (41). Liu et al (42) suggested that miR-34c overexpression inhibits the Notch signaling pathway by targeting Notch1 and Jagged1, which are two important factors for Notch signaling and apoptosis in HG-treated podocytes. Additionally, Zhang et al (41) provided evidence that miR-34a overexpression inhibits the Notch signaling pathway (Notch1, Jagged1, NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 proteins) and podocyte lesions induced by HG. miR-145 has primarily been defined by its role in diabetic retinopathy, where it acts as a negative regulator of toll like receptor 4/NF-κB signaling and attenuates HG-induced oxidative stress (41). Chen et al (43) revealed that miR-145 can suppress the HG-induced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells by targeting Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 1, which prevents the occurrence and progression of atherosclerosis. The present study first illustrated the transcriptional inhibition of the Notch signaling pathway by miR-145-5p, which protected podocytes from HG-induced injury. The present study supported the hypothesis that miR-145-5p may have a renal protective effect in DN via the amelioration of renal injury.

A number of factors in the apoptosis signaling pathway are also involved in the pathological process of DN. Previous studies indicate that DN can activate cell apoptosis-related proteins (Bcl-2, p53 and NF-κB) (44–47). Gao et al (48) reported that the expression levels of Notch1, Jagged1, NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 were upregulated in podocytes under HG conditions, and mediate the apoptosis of podocytes via the Bcl-2 and p53 signaling pathways.

The present study established an in vitro DN model by using HG-induced podocytes, and detected the expression levels of miR-145-5p in different groups, including the HG (25 mM glucose) and NG (5 mM glucose) groups, at different time points. The expression levels of miR-145-5p were lower in HG-induced podocytes than under NG conditions. Functional experiments were conducted, and the results of flow cytometry and TUNEL staining assays revealed that the overexpression of miR-145-5p inhibits HG-induced cell apoptosis. To further clarify possible mechanisms and signaling pathways, potential target genes of miR-145-5p were identified using miRanda, TargetScan and miRDB. The results of a luciferase assay demonstrated that Notch1 was a direct target of miR-145-5p. In addition, miR-145-5p mimic or inhibitor were transfected into the HG-induced podocytes. Subsequently, using western blotting and RT-qPCR, the downstream factors of the Notch signaling pathway, namely NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 were detected. The results demonstrated that overexpression of miR-145-5p resulted in the downregulation of NICD, Hes1 and Hey1 at the protein and mRNA levels. Finally, the levels of indicators of apoptotic signaling, including cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax, were measured. The results revealed that the overexpression of miR-145-5p inhibits these key factors, which suggests that miR-145-5p inhibits not only the Notch signaling pathway but also other apoptotic signaling pathways.

In conclusion, the present study identified that miR-145-5p overexpression could attenuate the apoptosis of HG-induced podocytes by inhibiting the activation of the Notch signaling pathway and other key factors of the apoptotic signaling pathway. Therefore, miR-145-5p could potentially serve as a novel and effective therapeutic target for future DN treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to further research being performed, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

BW and YSL designed the study, read and approved the final version of the manuscript; BW performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. HXG analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tong L, Adler SG. Diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:335–338. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04650417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying Q, Wu G. Molecular mechanisms involved in podocyte EMT and concomitant diabetic kidney diseases: An update. Ren Fail. 2017;39:474–483. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2017.1313164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asanuma K. The role of podocyte injury in chronic kidney disease. Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2015;38:26–36. doi: 10.2177/jsci.38.26. (In Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius FC, Coward RJ. Podocytes, signaling pathways and vascular factors in diabetic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:304–310. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armelloni S, Corbelli A, Giardino L, Li M, Ikehata M, Mattinzoli D, Messa P, Pignatari C, Watanabe S, Rastaldi MP. Podocytes: Recent biomolecular developments. Biomol Concepts. 2014;5:319–330. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2014-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tetreault N, De Guire V. miRNAs: Their discovery, biogenesis and mechanism of action. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:842–845. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duarte FV, Palmeira CM, Rolo AP. The role of microRNAs in mitochondria: Small players acting wide. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:865–886. doi: 10.3390/genes5040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li T, Cho WC. MicroRNAs: Mechanisms, functions and progress. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2012;10:237–238. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves P, Zeng Y. Biogenesis of mammalian microRNAs: A global view. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2012;10:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Wang C, Zhang D, Chu X, Zhang Y, Li J. miR-15b-5p ameliorated high glucose-induced podocyte injury through repressing apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses by targeting Sema3A. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:20869–20878. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Li YT, Zhang SX, Fu SZ, Ye XZ. miR-590-3p attenuates acute kidney injury by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 in septic mice. Inflammation. 2019;42:637–649. doi: 10.1007/s10753-018-0921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Zhu X, Zhang J, Shi J. MicroRNA-25 inhibits high glucose-induced apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells via PTEN/AKT pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng J, Wu Y, Deng Z, Zhou Y, Song T, Yang Y, Zhang X, Xu T, Xia M, Cai A, et al. miR-377 promotes white adipose tissue inflammation and decreases insulin sensitivity in obesity via suppression of sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) Oncotarget. 2017;8:70550–70563. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barutta F, Tricarico M, Corbelli A, Annaratone L, Pinach S, Grimaldi S, Bruno G, Cimino D, Taverna D, Deregibus MC, et al. Urinary exosomal microRNAs in incipient diabetic nephropathy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto S, Schulze KL, Bellen HJ. Introduction to Notch signaling. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1187:1–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1139-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hori K, Sen A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2135–2140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.127308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penton AL, Leonard LD, Spinner NB. Notch signaling in human development and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braune EB, Lendahl U. Notch-a goldilocks signaling pathway in disease and cancer therapy. Discov Med. 2016;21:189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voelkel JE, Harvey JA, Adams JS, Lassiter RN, Stark MR. FGF and Notch signaling in sensory neuron formation: A multifactorial approach to understanding signaling pathway hierarchy. Mech Dev. 2014;134:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saleem MA, O'Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:630–638. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepard BD, Natarajan N, Protzko RJ, Acres OW, Pluznick JL. A cleavable N-terminal signal peptide promotes widespread olfactory receptor surface expression in HEK293T cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loo DT. In situ detection of apoptosis by the TUNEL assay: An overview of techniques. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;682:3–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-409-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shan H, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Zhang Y, Pan Z, Cai B, Wang N, Li X, Feng T, Hong Y, Yang B. Downregulation of miR-133 and miR-590 contributes to nicotine-induced atrial remodelling in canines. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:465–472. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pockley AG, Foulds GA, Oughton JA, Kerkvliet NI, Multhoff G. Immune cell phenotyping using flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Toxicol. 2015;66:18.8.1–34. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.tx1808s66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam J, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife. 2015;4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Wang X. Prediction of functional microRNA targets by integrative modeling of microRNA binding and target expression data. Genome Biol. 2019;20:18. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1629-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng R, Pan L, Gao J, Ye X, Chen L, Zhang X, Tang W, Zheng W. Prognostic value of miR-106b expression in breast cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2015;195:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu ZH, Dai XM, Du B. Hes1: A key role in stemness, metastasis and multidrug resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16:353–359. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1016662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez-Mateo I, Arruabarrena-Aristorena A, Artaza-Irigaray C, Lopez JA, Calvo E, Belandia B. HEY1 functions are regulated by its phosphorylation at Ser-68. Biosci Rep. 2016;36(pii):e00343. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choudhary GS, Al-Harbi S, Almasan A. Caspase-3 activation is a critical determinant of genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1219:1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1661-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laulier C, Lopez BS. The secret life of Bcl-2: Apoptosis- independent inhibition of DNA repair by Bcl-2 family members. Mutat Res. 2012;751:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu S, Li T, Tan J, Yan X, Zhang D, Zheng C, Chen Y, Xiang Z, Cui H. Bax is essential for death receptor-mediated apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2012;27:577–581. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D, Lim S, Park M, Choi J, Kim J, Han H, Yoon K, Kim K, Lim J, Park S. Ubiquitination-dependent CARM1 degradation facilitates Notch1-mediated podocyte apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1774–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matoba K, Kawanami D, Nagai Y, Takeda Y, Akamine T, Ishizawa S, Kanazawa Y, Yokota T, Utsunomiya K. Rho-kinase blockade attenuates podocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the notch signaling pathway in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(pii):E1795. doi: 10.3390/ijms18081795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao F, Yao M, Cao Y, Liu S, Liu Q, Duan H. Valsartan ameliorates podocyte loss in diabetic mice through the Notch pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:1328–1336. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto S, Schulze KL, Bellen HJ. Introduction to Notch signaling. In: Bellen HJ, Yamamoto S, editors. Notch Signaling: Methods and Protocols. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun J, Zhao F, Zhang W, Lv J, Lv J, Yin A. BMSCs and miR-124a ameliorated diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting notch signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:4840–4855. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Song S, Luo H. Regulation of podocyte lesions in diabetic nephropathy via miR-34a in the Notch signaling pathway. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5050. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu XD, Zhang LY, Zhu TC, Zhang RF, Wang SL, Bao Y. Overexpression of miR-34c inhibits high glucose-induced apoptosis in podocytes by targeting Notch signaling pathways. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:4525–4534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen M, Zhang Y, Li W, Yang J. MicroRNA-145 alleviates high glucose-induced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells through targeting ROCK1. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;99:81–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui Y, Yin Y. MicroRNA-145 attenuates high glucose-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in retinal endothelial cells through regulating TLR4/NF-κB signaling. Life Sci. 2018;207:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim JH, Youn DY, Yoo HJ, Yoon HH, Kim MY, Chung S, Kim YS, Chang YS, Park CW, Lee JH. Aggravation of diabetic nephropathy in BCL-2 interacting cell death suppressor (BIS)-haploinsufficient mice together with impaired induction of superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Diabetologia. 2014;57:214–223. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deshpande SD, Putta S, Wang M, Lai JY, Bitzer M, Nelson RG, Lanting LL, Kato M, Natarajan R. Transforming growth factor-β-induced cross talk between p53 and a microRNA in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2013;62:3151–3162. doi: 10.2337/db13-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kolati SR, Kasala ER, Bodduluru LN, Mahareddy JR, Uppulapu SK, Gogoi R, Barua CC, Lahkar M. BAY 11–7082 ameliorates diabetic nephropathy by attenuating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammation via NF-κB pathway. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;39:690–699. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao F, Yao M, Shi Y, Hao J, Ren Y, Liu Q, Wang X, Duan H. Notch pathway is involved in high glucose-induced apoptosis in podocytes via Bcl-2 and p53 pathways. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:1029–1038. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to further research being performed, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.