Abstract

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades are key signalling pathways that regulate a wide variety of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and stress responses. The MAPK pathway includes three main kinases, MAPK kinase kinase, MAPK kinase and MAPK, which activate and phosphorylate downstream proteins. The extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK1 and ERK2 are evolutionarily conserved, ubiquitous serine-threonine kinases that regulate cellular signalling under both normal and pathological conditions. ERK expression is critical for development and their hyperactivation plays a major role in cancer development and progression. The Ras/Raf/MAPK (MEK)/ERK pathway is the most important signalling cascade among all MAPK signal transduction pathways, and plays a crucial role in the survival and development of tumour cells. The present review discusses recent studies on Ras and ERK pathway members. With respect to processes downstream of ERK activation, the role of ERK in tumour proliferation, invasion and metastasis is highlighted, and the role of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway in tumour extracellular matrix degradation and tumour angiogenesis is emphasised.

Keywords: extracellular signal-regulated kinase, Ras, Raf, ERK, mitogen-activated protein kinase, pathway, tumorigenesis, cancer

1. Introduction

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK) belongs to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, which plays a role in signalling cascades and transmits extracellular signals to intracellular targets. Therefore, MAPK cascades are central signalling elements that regulate basic processes including cell proliferation, differentiation and stress responses (1–3). These cascades transmit signals through sequential activation of three to five layers of protein kinases known as MAPK kinase kinase kinase (MAP4K), MAPK kinase kinase (MAP3K), MAPK kinase (MAPKK), MAPK and MAPK-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPK). The first three central layers are considered as a basic core unit, while the last two layers appear in some cascades and can vary among cells and stimuli. Four MAPK cascades have been defined based on the components in the MAPK layer: ERK1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 MAPK and ERK5. This review focuses on the ERK cascade (4–6) which involves several kinases in the MAP3K layer (mainly Rafs), including Ras/Raf/MAPK (MEK) 1/2 at the MAPKK layer, ERK1/2 at the MAPK layer and several MAPKAPKs in the next layer (ribosomal s6 kinases, MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinases, mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases and cytosolic phospholipase A2). ERK cascades are highly regulated cascades that are responsible for basic cellular processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation. These regulatory factors affect bispecific phosphatases (7–10), scaffold proteins (11–14), signal duration and intensity (15), and the dynamic subcellular localization of cascade components (16,17). Due to the importance of the ERK cascade, ERK disorders are harmful to cells and ultimately to the body. Excessive activation of upstream proteins and kinases in the ERK pathway has been shown to induce various diseases, including cancer, inflammation, developmental disorders and neurological disorders (18–22). Since ERK1 and ERK2 are very similar, the singular form of ERK is used in this review, although two subtypes exist.

Dysfunction in the Ras-ERK pathway is a major trigger for the development of most cancer types (23). Activation of the ERK cascade occurs in most cancer types, whereby activating mutations of this pathway are the most abundant oncogenic factor across all cancer types (24). Different components in the cascade are highly variable in human cancers (24). Driver mutations in ras (mainly K-ras) are the most common mutations in cancer, appearing in ~30% of all cancer types (25) and in ~10% of all patients with cancer (26). raf mutations (particularly in B-raf) have been detected in ~8% of all cancer types (26). The frequency of extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK) mutations is low (~1%), though a few major pathogenic mutations in ERK have been reported (26,27). This review focuses on the mechanism of the nuclear ERK/MAPK signalling pathway in cancer development. Specifically, the basic components of the MAPK signalling pathway and its basic structure, function and ERK composition are summarized. The role of ERK in tumour proliferation and invasion-metastasis is also reviewed, and the role of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway in tumour extracellular matrix degradation and tumour angiogenesis is emphasised, which has important therapeutic significance for preventing ERK/MAPK gene mutation.

2. MAPK signalling pathways

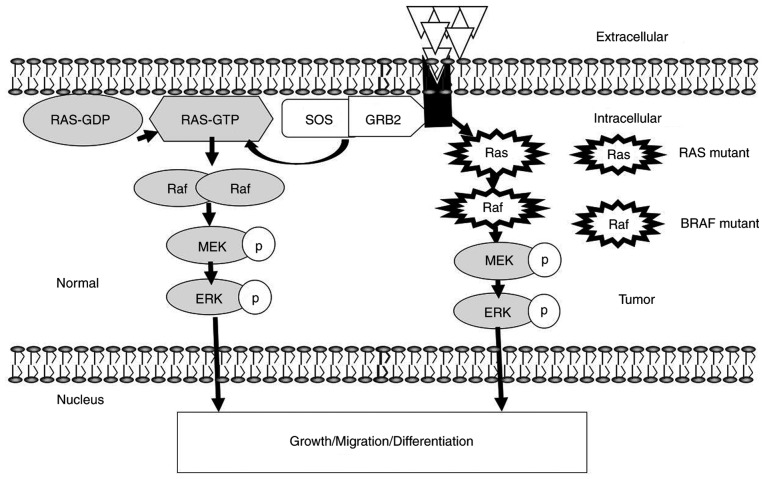

Among the numerous intracellular signalling pathways, the MAPK pathway plays a more important role in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis and tumour metastasis than other pathways. The following four MAPK cascades have been identified in eukaryotic cells: ERK, JNK/stress-activated protein kinase, p38 MAPK and ERK5 signal transduction pathways. Each MAPK signalling cascade consists of at least three tiers: MAP3K, MAPKK and MAPK (3,6) (Fig. 1). Studies have shown that the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways are mainly related to stress and apoptosis of cells, while the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway, which is the most thoroughly studied MAPK signalling pathway, is closely related to cell proliferation and differentiation and plays a pivotal role in the cell signal transduction network (11,28–30).

Figure 1.

MAPK cascades. MAPKs, which are present in the cytoplasm and can be translocated into the nucleus, catalyse the phosphorylation of dozens of cytosolic proteins and numerous nuclear transcription factors. Adapted from (29). MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MAP4K, MAPK kinase kinase kinase; MAP3K, MAPK kinase kinase; MAPKK, MAPK kinase; MAPKAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases; MEK, Ras/Raf/MAPK; RSK, ribosomal s6 kinase; MSK, mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases; MNK, MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinases; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; c-FOS, proto-oncogene c-Fos; Elk1, ETS domain-containing protein Elk-1; Ets1, Protein C-ets-1; SP-1, transcription factor Sp1.

3. ERK/MAPK structure and functions

Among all the signalling networks, the MAPK signal transmission pathway plays an important role in controlling various physiological processes in cells, such as cell growth, development, division and death. ERK is a member of the MAPK family, and the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway is the core of the signalling network involved in regulating cell growth, development and division. The basic signal transmission steps follow the MAPK tertiary enzymatic cascade, consisting of an upstream activator sequence, MAP3K, MAP2K and MAPK. In the ERK pathway, Ras acts as an upstream activating protein, Raf acts as MAP3K, MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) acts as MAPKK and ERK is the MAPK, forming the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway (31).

Members of the ERK family

ERK, a type of serine/threonine protein kinase, is a signal transduction protein that transmits mitogen signals (32). ERK is generally located in the cytoplasm; upon activation, ERK enters the nucleus and regulates transcription factor activity and gene expression (33). Through artificial cloning and sequencing analysis, the ERK family has been shown to consist of ERK 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 (3). ERK1 and ERK2 are two important members of the MAPK/ERK pathway, with molecular weights of 44 and 42 kDa, respectively (33). The C-terminus of ERK5 contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS), two proline-rich regions and a transcriptional activation domain (TAD). ERK5 is more than twice the molecular weight of other MAPKs (110 kDa). This structural difference enables active ERK5 to self-phosphorylate its C-terminal TAD, which is a unique ability of ERK5 to directly control its own gene transcription (34). In the non-phosphorylated state, ERK5 is in an inactive conformation and its N- and C-terminal domains are interconnected in the cytoplasm. Activation of MEK5 induces open conformation of ERK5, exposes the NLS, alleviates self-inhibition and promotes ERK5 translocation to the nucleus (35–37). ERK5 activity is also regulated by its splicing variants (a, b, and c) (38). Only ERK5a shows kinase activity, and both ERK5b and c are deficient in protein kinase activity and can inhibit MEK5-mediated ERK5a stimulation. The current manuscript focuses on the ERK1/2/MAPK signalling pathway.

ERK pathway upstream protein and kinase activation mechanism

Multiple stimulants such as growth factors, cytokines, viruses, G-protein-coupled receptor ligands and oncogenes activate the ERK pathway. Key molecules in the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway mainly include the small G proteins Ras and downstream Raf kinase, MEK1/2 and ERK1/2. Ras is the most conserved product encoded by the Ha-ras, Hi-ras and N-ras oncogenes of the ras gene family. Raf kinase is a product of the raf oncogene. MEK1 and MEK2 are rare dual-specificity kinases that can activate ERK through phosphorylation at two regulatory sites, Tyr 204/187 and Thr 202/185 (30).

Ras

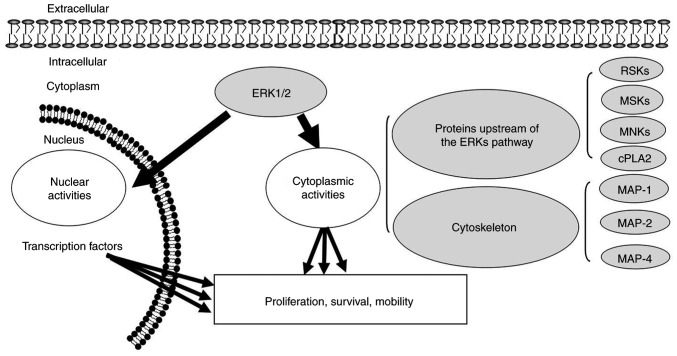

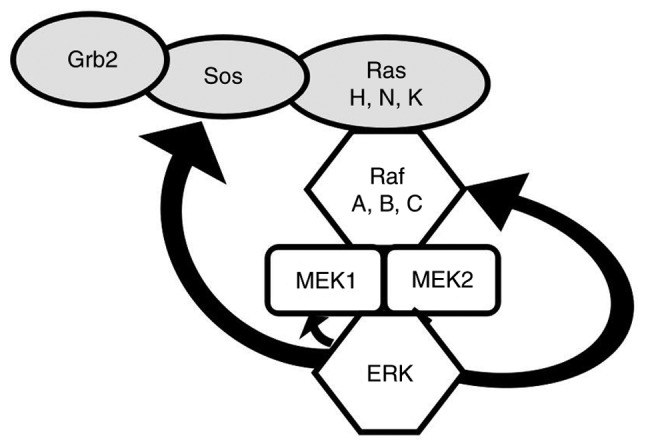

Ras, an upstream protein of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway, was the earliest discovered small G protein and product of the ras oncogene (39). It has an active GTP-binding conformation and an inactive GDP-binding conformation (40). The protein can alternate between the two conformations to regulate signal transduction (41). Ras is activated by many stimulating factors, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), tumour necrosis factor, activators of protein kinase C (PKC) and Src family members (42). When an extracellular signal binds to the receptor, a connector molecule, growth factor receptor-binding protein 2 (Grb2), binds to the activated receptor and interacts with the proline-rich sequence at the C-terminus of son of sevenless (SOS) to form the receptor-Grb2-SOS complex. Binding of SOS to the Tyr phosphorylation site on the receptor or receptor substrate protein leads to translocation of cytoplasmic SOS to the membrane, resulting in a high concentration of SOS near Ras (43). SOS and Ras-GDP promote the replacement of GDP with GTP in Ras, thereby activating Ras to initiate the Ras pathway (44) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

ERK MAPK signalling pathway. The kinase-mediated ERK MAPK signalling is sequentially activated by phosphorylation. ERK1/2 at the terminal kinases in MAPK signalling can translocate to the nucleus to regulate transcription programs, and mediate growth, migration and differentiation. The phosphorylated forms of MEK and ERK are indicated by white circles. Membrane Receptors are presented by grey shapes. Ligands are represented by white triangles. The cytoplasmic receptor is indicated by a thick black arrow. Adapted from (78,79). SOS, son of sevenless; GRB2, growth factor receptor-binding protein 2; p, phosphorylated.

Raf

The Raf protein kinase is a protein encoded by the raf gene and is composed of 648 amino acids (aa) with a molecular weight of 40–75 kDa (42). Raf exhibits serine/threonine protein kinase activity after binding to Ras. Its molecular structure comprises three conserved regions: Conserved region (CR) l (located at aa 61–194), CR2 (located at aa 254–269) and CR3 (located at aa 335–627). CRl, located at the amino terminus, is rich in cysteine and contains a zinc finger-like structure, similar to the ligand-binding region of PKC (45). CR1 is the main site of activated Ras binding to Raf-1 protein kinase. CR2 is present near the amino terminus and contains many serine and threonine residues (45). CR3, located at the carboxyl terminus, is the catalytic functional region of the Raf-1 protein kinase (46). The Raf kinase family has three subtypes: Raf-1, A-Raf and B-Raf. Raf kinases can be activated in the following ways: i) Localisation of Raf on the inside of the cell membrane through its interaction with Ras (47); ii) dimerization of Raf protein; iii) phosphorylation and dephosphorylation at different sites; iv) dissociation with Raf kinase inhibitor protein; and v) binding to Ras kinase inhibitor (47). Raf-1 plays an important role in the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK cell proliferation signalling pathway. Stokoe et al (48) suggested that activation of Raf-1 occurs in two steps. The first step is Ras binding to and fixing Raf-1 on the inner side of the membrane; the second step is activation of Raf-1, which may be conducted by tyrosine kinase. In the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK proliferation signal transduction pathway, Ras, as the upstream activated protein, uses two regions, the Ras-binding domain and cysteine-rich domain at the N-terminus of Raf-1, to bind and translocate Raf from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane, where Raf is activated. Activated Raf-1 continues to activate downstream MEK and MAPK, and finally delivers cell proliferation and differentiation signals to the nucleus by regulating the activity of various transcriptional regulators, which regulate gene expression (49). Although Raf kinases are highly conserved among subtypes, their activity, tissue distribution and modality of regulation differ (50). A-Raf shows the weakest kinase activity, while B-Raf shows the strongest activity. Among the three subtypes, B-Raf has the highest mutation rate, which is 90% in melanoma (Table I) (51–73).

Table I.

Frequency of mutations in the activator components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK pathway across different tumours.

| Author, year | Tumour type | KRAS | NRAS | HRAS | BRAF | MEK | ERK | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombino et al, 2012; Edlundh-Rose et al, 2006; Namba et al, 2003; Davies et al, 2002; Murugan et al, 2009; Nikolaev et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2007; Jänne et al, 2017 | Melanoma | 15–29% | 20% | N/A | 90% | 3–8% | 67–90% | (51–58) |

| Nikolaev et al, 2011; Seo et al, 2012; Cardarella et al, 2013 | NSCLC | 35% | N/A | N/A | 4% | N/A | N/A | (56,59,60) |

| Davies et al, 2002; Tol et al, 2009; Jones et al, 2017 | Colorectal | 40% | N/A | N/A | 5–20% | <3% | N/A | (54,61,62) |

| Sieben et al, 2004 | HGSOC | 0–12% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | (63) |

| Bell, 2005; Singer et al, 2003 | LGSOC | 27–36% | N/A | N/A | 33–50% | N/A | N/A | (64,65) |

| Cardarella et al, 2013; Bansal et al, 2013; Paik et al, 2011 | THCA | 9–27% | 9–27% | 9–27% | 10–70% | N/A | N/A | (60,66,67) |

| Bansal et al, 2013; Xing et al, 2013 | PTC | 20% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | (66,68) |

| Singer et al, 2003; Bansal et al, 2013 | ATC/FTC | N/A | 15% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | (65,66) |

| Tiacci et al, 2011 | Hairy Cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | 79–100% | N/A | N/A | (69) |

| Namba et al, 2003 | PDAs | 70% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | (53) |

| Jones et al, 2017; Xi et al, 2012 | AML/ALL | 10% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | (63,70) |

| Cardarella et al, 2013 | BLCA | N/A | N/A | 20% | N/A | N/A | N/A | (60) |

| Paik et al, 2011 | RCCs | N/A | N/A | 2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | (67) |

| Davies et al, 2002; Chao et al, 1999; Cheng et al, 2005; Sun et al, 2001 | BC | <5% | N/A | N/A | 1.2% | 7–9% | N/A | (54,71–73) |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; LGSOC, low-grade serous ovarian cancer; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid cancers; ATC, anaplastic thyroid cancers; FTC, follicular thyroid cancers; PDAs, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas; AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinomas; RCCs, renal cell carcinomas; BC, breast cancer.

MEK (MAPK/ERK kinase)

When Raf is activated, its C-terminal catalytic domain can interact with MEK, and its catalytic VIII subregion is phosphorylated at the serine residue, activating MEK. The two MEK subtypes, MEK1 and MEK2, have molecular weights of 44 and 45 kDa, respectively (74). MEK is a rare dual-specificity kinase that activates ERK by phosphorylating the Tyr and Thr regulatory sites (75). How MEK has both Tyr and Thr specific phosphorylation activity is unclear, but it has important physiological significance, as the ERK signalling pathway is in a central position in the cell signal transduction network, and any errors in activation can profoundly influence cellular processes. This recognition and activation mechanism that confers double specificity greatly improves the accuracy of signal transduction and prevents errors in ERK activation (62).

ERK

MAPK/ERK is a Ser/Thr protein kinase. When multiple kinases act on MEK, activated MEK directly interacts with ERKs through its N-terminal region, catalysing the bispecific phosphorylation of Tyr and Thr residues in the 8 ‘TEY box’ of the sub-functional region of ERK to activate ERK. MEK not only activates ERK, but also anchors ERK in the cytoplasm. When the signalling pathway is inactive, ERK is localized to the cytoplasm. Once a signal stimulates the phosphorylation and dimerization of ERK, activated ERKs are translocated to the nucleus, promote cytoplasmic target protein phosphorylation or regulate the activity of other protein kinases, followed by further phosphorylation of downstream substrates. Avruch et al (76) studied the process of ERK2 phosphorylation and translocation into the nucleus and found that both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated ERK2 form a homologous dimer before nuclear translocation, indicating that formation of the homologous dimer is necessary for ERK nuclear translocation (25,47).

4. Activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway

Various stimulating factors, such as cytokines, viruses, G-protein-coupled receptor ligands and oncogenes, play regulatory roles by activating the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway. The ERK/MAPK signalling pathway can be activated through the following ways: i) Ca2+activation; ii) receptor tyrosine kinase Ras activation; iii) PKC-mediated activation; and iv) G protein-coupled receptor activation (77).

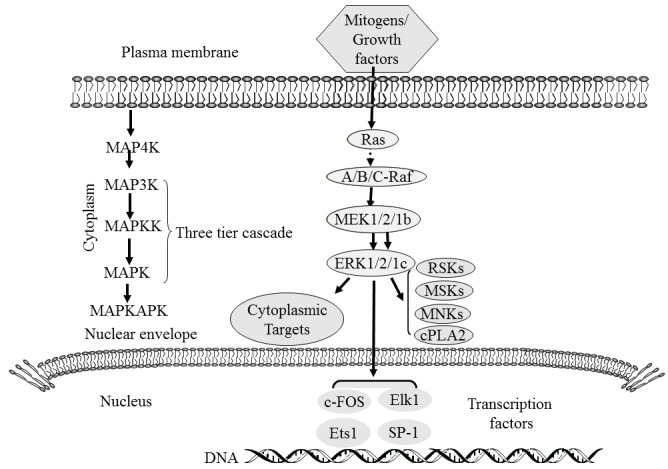

5. Downstream of ERK1/2

ERK1/2 is located in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells. Once activated, ERK1/2 is transferred to the nucleus and regulates the activity of various transcription factors through phosphorylation, eventually regulating cell metabolism and function and influencing the specific biological effects of cells (Fig. 3). Cytoskeletal components such as microtubule-associated protein (MAP) 1, MAP2 and MAP4 are phosphorylated in the cytoplasm to participate in the regulation of cell morphology and cytoskeletal redistribution. In the nucleus, the phosphorylation of nuclear transcription factors such as proto-oncogene c-Fos, proto-oncogene c-Jun, ETS domain-containing protein Elk-1, proto-oncogene c-Myc and cyclic AMP-dependent transcription factor ATF2. Cytoplasmic ERK1/2 can phosphorylate a series of other protein kinases upstream of the ERK pathway, such as SOS, Raf-1 and MEK in a negative feedback regulatory manner (Fig. 4). Activation of ERK/MAPK signalling pathways activates other extracellular signalling pathways. Extracellular signals such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor and EGF can be activated by receptor tyrosine kinase autologous phosphorylation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway. Activated ERK may enter the nucleus and bind to transcription factors that induce gene expression in response to extracellular stimuli, and regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and transcription (4,80–83).

Figure 3.

Downstream propagation direction of ERK1/2 kinase signalling in the ERK pathway. ERK1/2 is located in the cytoplasm of normal cells, while activated ERK1/2 is translocated to the nucleus to regulate the activity of transcription factors through phosphorylation. Cytoskeletal components are phosphorylated by ERK1/2 in the cytoplasm. Black arrows indicate signal propagation downstream of ERK. ‘Nuclear activities’ and ‘cytoplasmic activities’ depict ERK activation in the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively. RSK, ribosomal s6 kinase; MSK, mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinases; MNK, MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinases; cPLA2, cytosolic phospholipase A2; MAP, microtubule-associated protein.

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of upstream protein kinases in the ERK pathway. Curved arrows indicate the downstream targets of ERK. SOS, son of sevenless; GRB2, growth factor receptor-binding protein 2.

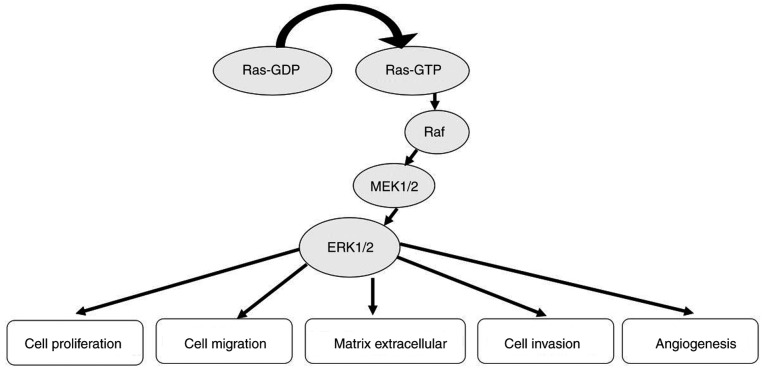

6. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis

The ERK/MAPK signalling pathway is not only involved in regulating cellular biological functions, such as cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell cycle regulation, cell apoptosis and tissue formation, but is also related to tumour formation (84) (Fig. 5). Elevated ERK expression has been detected in various human tumours, such as ovarian, colon, breast and lung cancer (85–88). Denkert et al (89) found that the expression of MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) in normal ovarian surface epithelium and benign cystadenomas is increased compared to invasive carcinomas and low malignancy potential tumors and borderline tumors. The expression level of MKP-1 in tumour tissues of patients with stage III/IV disease was significantly lower compared with that in patients with stage I/II disease. Expression of the phosphorylated form of ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2) was significantly increased in normal ovarian tissues, benign tumours and borderline tumours. The expression level of p-ERK1/2 in stage III/IV patients was significantly higher compared with that in stage I/II patients. There was a significant negative correlation between MKP-1 and p-ERK1/2 expression in the same ovarian cancer tissue detected by immunohistochemistry and western blotting. Abnormal expression of MKP-1 and ERKs may play a role in the development of ovarian cancer. Hong et al (90) found that the expression levels of MAPK1 and ERK in ovarian cancer tissues were higher compared with those in adjacent normal tissues. Lee et al (91) showed that the rates of MEK phosphorylation in colon cancer, villous adenoma and tubular adenoma were 76, 40 and 30%, respectively, while the phosphorylation of MEK in normal colonic mucosal cells was barely detectable. Continuous activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway can promote the transformation of normal cells into tumour cells, while inhibition of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway can restore tumour cells to a non-transformed state in vitro and can inhibit tumour growth in vivo (92). Therefore, increased activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway may be closely related to the occurrence and development of tumours.

Figure 5.

Role of ERK/mitogen-activated protein kinase in cancer.

Role of ERK/MAPK in cell proliferation

Unlimited cell proliferation, dedifferentiation and a lack of apoptosis are important biological characteristics of tumours (93). The activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway promotes proliferation and has an anti-apoptotic effect. Hypoxia-induced VEGF can inhibit the apoptosis of serum-starved cells by activating the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway (94). Inhibiting the expression of this pathway can inhibit the proliferation of and lack of apoptosis in tumour cells, and promote their differentiation (95). Gauthier et al (96) found that the ERK1/2 signalling pathway is involved in cell survival following intestinal injury, and inhibition of this pathway can promote the apoptosis of intestinal injury cells. Huang et al (97) found that blocking the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway inhibited the proliferation of a diffuse large B cell lymphoma cell line and promoted cell apoptosis. Inhibiting the expression of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway to inhibit tumour cell proliferation may involve inhibition of the cell cycle (98). Sebolt-Leopold et al (92) showed that the use of MEK1/2 inhibitors to inhibit ERK1/2 activity in colon cancer cells could prevent the cells from entering the S phase from the G1 phase, and inhibit the growth of adherent cells. Inhibition of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway can reduce cell dedifferentiation and the anti-apoptosis effect. Maemura et al (99) reported that the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by influencing the activity of downstream cell cycle regulatory proteins, apoptosis-related proteins and other effector molecules, such as G1/S specific cyclin D1. Ellipticine, an alkaloid with anti-tumour activity, induces apoptosis of the human endometrial cancer cell line RL95-2 by activating reactive oxygen species and MAPK/ERK (18). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone induces activation of the MAPK signaling pathway in normal and carcinoma cells of the human ovary and placenta (100). SPACRC-like protein 1 (SPARCL1) is overexpressed in ovarian cancer; by inhibiting activation of the MEK/ERK signalling pathway, SPARCL1 is downregulated through the MEK/ERK pathway and inhibits the proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer cells (101).

ERK/MAPK signalling in tumour invasion and metastasis

Invasion and metastasis of tumour cells occurs in three stages: Adhesion, degradation and migration. Tumour cells break away from the primary tumour, adhere to the basement membrane and become invasive. Tumour cells infiltrate and grow in the surrounding stroma and enter the circulatory system, where most cells are killed by the immune system. A small number of tumour cells with strong survival ability reach the target organ and continue to proliferate, forming new metastases in the same manner as the primary tumour. This process involves the coordination of multiple signalling pathways, and the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway plays an important role in tumour invasion and metastasis (102).

Sung et al (103) established a mouse model of metastatic xenotransplantation using human ovarian carcinoma SK-OV-3 cells. They found that γ-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit π (GABRP) expression was upregulated (>4-fold) in metastatic tissues from the xenograft mice compared with SK-OV-3 cells. GABRP knockdown diminished the migration and invasion of SK-OV-3 cells and reduced ERK activation, while overexpression of GABRP exhibited significantly increased cell migration, invasion and ERK activation. The MEK inhibitor U0126 is a specific and non-ATP-competitive MEK1 and MEK2 inhibitor. U0126 acts on recombinant constitution-activated mutant MEK1 (at sites DN3-S218E/S222D), blocking MAPK signal transmission. U0126 inhibited the migration and invasion of SK-OV-3 cells (103). Liu et al (104) found that death domain-associated protein 6 promoted the proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer ascites cells by activating the ERK signalling pathway. Zhao et al (105) found that CD147 promoted Sp1 phosphorylation at T453 and T739 through the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways and that blocking the positive feedback loop of Sp1-CD147 reduced the invasive ability of human ovarian cancer (ho8910) cells. The Sp1-CD147 positive feedback loop may play a key role in the invasive ability of ovarian cancer cells. Down-regulation of the long non-coding RNA MIR4697 host gene (MIR4697HG) promotes the growth and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells by lowering levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9, p-ERK, and phosphorylated AKT (106). Downregulation of MIR4697HG inhibited cell migration and invasion (106).

ERK/MAPK signalling pathway is involved in degradation of the tumour extracellular matrix

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are proteolytic enzymes that hydrolyse the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is one of the most important processes in the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells (107). Overexpression of MMPs is beneficial for tumour invasion and metastasis, while inhibiting the expression of MMPs has the opposite effects. Maeda-Yamamoto et al (108) showed that inhibition of ERK phosphorylation by epigallocatechin gallate in fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells resulted in inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression in these cells. The expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 depends on the phosphorylation of ERK. Simon et al (109) found that in oral cancer cells, ERK1/ERK2 activation inhibitors reduced the activity of ERK1/ERK2 while downregulating MMP-9 and reducing invasiveness. The activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway can increase tumour invasion and metastasis by upregulating MMP expression, while inhibition of this signalling pathway can reduce tumour invasion and metastasis (110–111). A previous study reported that mesothelin regulates the expression of MMP-7 through the MAPK/ERK signal transduction pathway, ERK1/2, AKT and JNK pathways, which enhances the invasiveness of ovarian cancer (112). In vitro, an ERK1/2 inhibitor or decoy activator protein 1 oligonucleotide inhibited MMP-7 expression and the migration of MSLN-treated ovarian cancer cells. Intra-tumoural MMP-7 expression was reduced by a kinase/ERK inhibitor, resulting in delayed tumour growth and prolonged survival of mice (113).

ERK/MAPK signalling pathway is involved in tumour cell migration

Cell deformation and migration occurs during tumour metastasis. The expression of cytoskeletal and microfilament-related proteins is related to the deformation and migration of tumour cells. The human colon cancer cell line SW620 showed a larger number of intracellular microfilaments and a longer migration distance upon treatment with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) compared with a control treatment. The study showed that HGF enhanced cell migration by activating the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway, thus promoting the invasion and metastasis of tumour cells. Further studies showed that protein phosphorylation is associated with regulation of the microfilament cytoskeleton (114–115). Bray et al (114) demonstrated that ERK/MAPK signalling pathways transduce extracellular signals and regulate the expression of transcription factors that cause cytoskeleton deformation and enhance tumour invasion and metastasis. Blocking the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway may inhibit the role of HGF and other extracellular signals that promote cell movement, which inhibits tumour invasion and metastasis.

Role of activation of ERK/MAPK signalling pathway in tumour angiogenesis

All processes in cells, including tumour cells, require certain nutrients, which are provided to cells through blood vessels. In the absence of blood vessels, tumour tissues rarely exceed 2 mm3 (116); blood vessels are also the channels through which tumour metastasis occurs (117). Tumour angiogenesis involves not only the overexpression of angiogenic factors, but also the low expression of angiogenic inhibitors and an imbalance between the two (118). VEGF is an important pro-angiogenic factor and the most powerful pro-vascular endothelial growth cytokine that promotes cell division and vascular construction from esophageal cancer and ovarian cancer, increases microvascular permeability and promotes endothelial cell migration (119–121).

ERK/MAPK signalling pathways can activate transcription factors to enhance the transcription of VEGF, increasing VEGF expression in tumour cells and promoting the formation of blood vessels. The MAPK/ERK pathway can inhibit thrombospondin-1, the expression of which promotes blood vessel formation and thus promotes tumour growth, invasion and metastasis. Interleukin (IL)-8 and VEGF are jointly expressed in various tumours and can promote tumour angiogenesis, growth and metastasis. ERK1/2 can be used as an alternative pathway to induce the expression of IL-8 and VEGF, thereby promoting the formation of tumour blood vessels. Inhibition of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway provides a theoretical basis for inhibiting tumour angiogenesis, thereby inhibiting tumour growth and metastasis. Soula-Rothhut et al (122) showed that the MEK inhibitor U0126 inhibited the expression of thrombospondin-1 induced by follicular thyroid carcinoma-133. Activation of the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway plays a role in inducing VEGF expression in colorectal cancer (123). HGF upregulates the expression of VEGF in colorectal cancer cells through the MEK/MAPK or PI3K/AKT signalling pathways (124). Inhibition of MEK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT signalling pathways can reduce VEGF expression, inhibit tumour angiogenesis and inhibit tumour growth and metastasis.

The downstream target of ERK/MAPK, the 70-kDa ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (p70S6K1), is an important regulator of cell cycle progression and proliferation. A study showed that vector-based small interfering RNA against p70S6K1 inhibited p70S6K1 activity in ovarian cancer cells and decreased VEGF protein expression (124). Downregulation of p70S6K1 inhibits the growth and angiogenesis of ovarian tumours and reduces the proliferation and expression levels of VEGF and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in tumour tissues, further inhibiting the growth and angiogenesis of ovarian tumours (125).

7. Conclusions

This review summarized how the ERK/MAPK signalling pathway affects the occurrence and development of human tumours. Further studies will reveal additional details regarding the role of MAPK signalling pathways in tumour pathogenesis. The cellular signalling pathway is a complex network. Activation of a signalling molecule by its downstream signal has biological effects such as promoting or inhibiting tumour cell growth and invasion; however, the regulatory mechanism of synergism or antagonism among intracellular signalling pathways remains unclear. The role of signalling pathways in cellular processes requires further analysis to clarify the role of signalling pathways in tumorigenesis and development. This may further provide new methods for treating tumours.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by The Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LY17H160060), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31871402 and 81402162), the Experimental Animal Science and Technology Plan Projects of Zhejiang Province (grant no. 2017C37173) and the College Student's Science and Technology Innovation Project (grant no. 2018R417024).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YJG, WWP and SBL conceived and designed the article. YX and ZFS analysed the relevant literature. YJG wrote the manuscript and drew the figures. YJG, YX, ZFS and LLH made revised the manuscript. YJG, WWP and SBL are responsible for text layout.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Keshet Y, Seger R. The MAP kinase signaling cascades: A system of hundreds of components regulates a diverse array of physiological functions. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;661:3–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-795-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabio G, Davis RJ. TNF and MAP kinase signalling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plotnikov A, Zehorai E, Procaccia S, Seger R. The MAPK cascades: Signaling components, nuclear roles and mechanisms of nuclear translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1619–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eblen ST. Extracellular-regulated kinases: Signaling from ras to ERK substrates to control biological outcomes. Adv Cancer Res. 2018;138:99–142. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roskoski R., Jr ERK1/2 MAP kinases: Structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol Res. 2012;66:105–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wortzel I, Seger R. The ERK cascade: Distinct functions within various subcellular organelles. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:195–209. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seternes OM, Kidger AM, Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:124–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson KI, Brummer T, O'Brien PM, Daly RJ. Dual-specificity phosphatases: Critical regulators with diverse cellular targets. Biochem J. 2009;418:475–489. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou B, Wang ZX, Zhao Y, Brautigan DL, Zhang ZY. The specificity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31818–31825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Z, Seger R. The molecular mechanism of MAPK/ERK inactivation. Curr Genomics. 2004;5:385–393. doi: 10.2174/1389202043349309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison DK, Davis RJ. Regulation of MAP kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:91–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chuderland D, Seger R. Protein-protein interactions in the regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Mol Biotechnol. 2005;29:57–74. doi: 10.1385/MB:29:1:57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaul YD, Seger R. The MEK/ERK cascade: From signaling specificity to diverse functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: Transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wainstein E, Seger R. The dynamic subcellular localization of ERK: Mechanisms of translocation and role in various organelles. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;39:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao Z, Seger R. The ERK signaling cascade-views from different subcellular compartments. Biofactors. 2009;35:407–416. doi: 10.1002/biof.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JY, Lee SG, Chung JY, Kim YJ, Park JE, Koh H, Han MS, Park YC, Yoo YH, Kim JM. Ellipticine induces apoptosis in human endometrial cancer cells: The potential involvement of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinases. Toxicology. 2011;289:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshizumi M, Kyotani Y, Zhao J, Nagayama K, Ito S, Tsuji Y, Ozawa K. Role of big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (BMK1)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) in the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerosis. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;120:259–263. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12R11CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogoyevitch MA, Ngoei KR, Zhao TT, Yeap YY, Ng DC. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling: Recent advances and challenges. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta J, Nebreda AR. Roles of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in mouse models of inflammatory diseases and cancer. FEBS J. 2015;282:1841–1857. doi: 10.1111/febs.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.García-Gómez R, Bustelo XR, Crespo P. Protein-protein interactions: Emerging oncotargets in the RAS-ERK pathway. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:616–633. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khotskaya YB, Holla VR, Farago AF, Mills Shaw KR, Meric-Bernstam F, Hong DS. Targeting TRK family proteins in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;173:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maik-Rachline G, Hacohen-Lev-Ran A, Seger R. Nuclear ERK: Mechanism of translocation, substrates, and role in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(pii):E1194. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Vega F, Mina M, Armenia J, Chatila WK, Luna A, La KC, Dimitriadoy S, Liu DL, Kantheti HS, Saghafinia S, et al. Oncogenic signaling pathways in the cancer genome atlas. Cell. 2018;173:321–337.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holderfield M, Deuker MM, McCormick F, McMahon M. Targeting RAF kinases for cancer therapy: BRAF-mutated melanoma and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:455–467. doi: 10.1038/nrc3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khokhlatchev AV, Canagarajah B, Wilsbacher J, Robinson M, Atkinson M, Goldsmith E, Cobb MH. Phosphorylation of the MAP kinase ERK2 promotes its homodimerization and nuclear translocation. Cell. 1998;93:605–615. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S, Liu G. Targeting the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:1041–1047. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anjum R, Blenis J. The RSK family of kinases: Emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:747–758. doi: 10.1038/nrm2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boulton TG, Nye SH, Robbins DJ, Ip NY, Radziejewska E, Morgenbesser SD, DePinho RA, Panayotatos N, Cobb MH, Yancopoulos GD. ERKs: A family of protein-serine/threonine kinases that are activated and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to insulin and NGF. Cell. 1991;65:663–675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90098-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morimoto H, Kondoh K, Nishimoto S, Terasawa K, Nishida E. Activation of a C-terminal transcriptional activation domain of ERK5 by autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35449–35456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buschbeck M, Ullrich A. The unique C-terminal tail of the mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK5 regulates its activation and nuclear shuttling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2659–2667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimoto S, Nishida E. MAPK signalling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:782–786. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kondoh K, Terasawa K, Morimoto H, Nishida E. Regulation of nuclear translocation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 by active nuclear import and export mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1679–1690. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1679-1690.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan C, Luo H, Lee JD, Abe J, Berk BC. Molecular cloning of mouse ERK5/BMK1 splice variants and characterization of ERK5 functional domains. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10870–10878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou B, Der CJ, Cox AD. The role of wild type RAS isoforms in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;58:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muñoz-Maldonado C, Zimmer Y, Medová M. A comparative analysis of individual RAS mutations in cancer biology. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1088. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dohlman HG, Campbell SL. Regulation of large and small G proteins by ubiquitination. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:18613–18623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terrell EM, Morrison DK. Ras-mediated activation of the raf family kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;9(pii):a033746. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bandaru P, Kondo Y, Kuriyan J. The interdependent activation of son-of-sevenless and ras. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;9(pii):a031534. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a031534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simanshu DK, Nissley DV, McCormick F. RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rukhlenko OS, Khorsand F, Krstic A, Rozanc J, Alexopoulos LG, Rauch N, Erickson KE, Hlavacek WS, Posner RG, Gómez-Coca S, et al. Dissecting RAF inhibitor resistance by structure-based modeling reveals ways to overcome oncogenic RAS signaling. Cell Syst. 2018;7:161–179.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roskoski R., Jr RAF protein-serine/threonine kinases: Structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roskoski R., Jr Targeting ERK1/2 protein-serine/threonine kinases in human cancers. Pharmacol Res. 2019;142:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stokoe D, McCormick F. Activation of c-Raf-1 by Ras and Src through different mechanisms: Activation in vivo and in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:2384–2396. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandamme D, Herrero A, Al-Mulla F, Kolch W. Regulation of the MAPK pathway by raf kinase inhibitory protein. Crit Rev Oncog. 2014;19:405–415. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2014011922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding Q, Wang Q, Evers BM. Alterations of MAPK activities associated with intestinal cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:282–288. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colombino M, Capone M, Lissia A, Cossu A, Rubino C, De Giorgi V, Massi D, Fonsatti E, Staibano S, Nappi O, et al. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2522–2529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edlundh-Rose E, Egyházi S, Omholt K, Månsson-Brahme E, Platz A, Hansson J, Lundeberg J. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma tumours in relation to clinical characteristics: A study based on mutation screening by pyrosequencing. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:471–478. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232300.22032.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Namba H, Nakashima M, Hayashi T, Hayashida N, Maeda S, Rogounovitch TI, Ohtsuru A, Saenko VA, Kanematsu T, Yamashita S. Clinical implication of hot spot BRAF mutation, V599E, in papillary thyroid cancers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4393–4397. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nat. 2002;417:949–954. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murugan AK, Dong J, Xie J, Xing M. MEK1 mutations, but not ERK2 mutations, occur in melanomas and colon carcinomas, but none in thyroid carcinomas. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2122–2124. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nikolaev SI, Rimoldi D, Iseli C, Valsesia A, Robyr D, Gehrig C, Harshman K, Guipponi M, Bukach O, Zoete V, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2011;44:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ng.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang D, Boerner SA, Winkler JD, LoRusso PM. Clinical experience of MEK inhibitors in cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1248–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jänne PA, van den Heuvel MM, Barlesi F, Cobo M, Mazieres J, Crinò L, Orlov S, Blackhall F, Wolf J, Garrido P, et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel compared with docetaxel alone and progression-free survival in patients with KRAS-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The SELECT-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1844–1853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seo JS, Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY, Lee JK, Bleazard T, Lee J, Jung YJ, Kim JO, Shin JY, et al. The transcriptional landscape and mutational profile of lung adenocarcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22:2109–2119. doi: 10.1101/gr.145144.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cardarella S, Ogino A, Nishino M, Butaney M, Shen J, Lydon C, Yeap BY, Sholl LM, Johnson BE, Jänne PA. Clinical, pathologic, and biologic features associated with BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4532–4540. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tol J, Nagtegaal ID, Punt CJ. BRAF mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:98–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0904160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones JC, Renfro LA, Al-Shamsi HO, Schrock AB, Rankin A, Zhang BY, Kasi PM, Voss JS, Leal AD, Sun J, et al. Non-V600 BRAF mutations define a clinically distinct molecular subtype of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2624–2630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.4394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sieben NL, Macropoulos P, Roemen GM, Kolkman-Uljee SM, Jan Fleuren G, Houmadi R, Diss T, Warren B, Al Adnani M, De Goeij AP, et al. In ovarian neoplasms, BRAF, but not KRAS, mutations are restricted to low-grade serous tumours. J Pathol. 2004;202:336–340. doi: 10.1002/path.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bell DA. Origins and molecular pathology of ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl 2):S19–S32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singer G, Oldt R, III, Cohen Y, Wang BG, Sidransky D, Kurman RJ, Shih IeM. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:484–486. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bansal M, Gandhi M, Ferris RL, Nikiforova MN, Yip L, Carty SE, Nikiforov YE. Molecular and histopathologic characteristics of multifocal papillary thyroid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1586–1591. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318292b780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, Sima CS, Miller VA, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, Riely GJ. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2046–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, Viola D, Elisei R, Bendlova B, Yip L, Mian C, Vianello F, Tuttle RM, et al. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:1493–1501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tiacci E, Trifonov V, Schiavoni G, Holmes A, Kern W, Martelli MP, Pucciarini A, Bigerna B, Pacini R, Wells VA, et al. BRAF mutations in hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2305–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xi L, Arons E, Navarro W, Calvo KR, Stetler-Stevenson M, Raffeld M, Kreitman RJ. Both variant and IGHV4-34-expressing hairy cell leukemia lack the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2012;119:3330–3332. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chao TH, Hayashi M, Tapping RI, Kato Y, Lee JD. MEKK3 directly regulates MEK5 activity as part of the big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (BMK1) signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36035–36038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng J, Yu L, Zhang D, Huang Q, Spencer D, Su B. Dimerization through the catalytic domain is essential for MEKK2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13477–13482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sun W, Kesavan K, Schaefer BC, Garrington TP, Ware M, Johnson NL, Gelfand EW, Johnson GL. MEKK2 associates with the adapter protein Lad/RIBP and regulates the MEK5-BMK1/ERK5 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5093–5100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Muta Y, Matsuda M, Imajo M. Divergent dynamics and functions of ERK MAP kinase signaling in development, homeostasis and cancer: Lessons from fluorescent bioimaging. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(pii):E513. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Avruch J, Khokhlatchev A, Kyriakis JM, Luo Z, Tzivion G, Vavvas D, Zhang XF. Ras activation of the Raf kinase: Tyrosine kinase recruitment of the MAP kinase cascade. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2001;56:127–155. doi: 10.1210/rp.56.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lawrence MC, Jivan A, Shao C, Duan L, Goad D, Zaganjor E, Osborne J, McGlynn K, Stippec S, Earnest S, et al. The roles of MAPKs in disease. Cell Res. 2008;18:436–442. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shin M, Franks CE, Hsu KL. Isoform-selective activity-based profiling of ERK signaling. Chem Sci. 2018;9:2419–2431. doi: 10.1039/C8SC00043C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanchez JN, Wang T, Cohen MS. BRAF and MEK inhibitors: Use and resistance in BRAF-mutated cancers. Drugs. 2018;78:549–566. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0884-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kolch W. Meaningful relationships: The regulation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway by protein interactions. Biochem J. 2000;351:289–305. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schulze A, Lehmann K, Jefferies HB, McMahon M, Downward J. Analysis of the transcriptional program induced by Raf in epithelial cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:981–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.191101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deming D, Geiger P, Chen H, Vaccaro A, Kunnimalaiyaan M, Holen K. ZM336372, a Raf-1 activator, causes suppression of proliferation in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:852–857. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0495-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.O'Neill E, Kolch W. Conferring specificity on the ubiquitous Raf/MEK signalling pathway. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:283–288. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rubinfeld H, Seger R. The ERK cascade: A prototype of MAPK signaling. Mol Biotechnol. 2005;31:151–174. doi: 10.1385/MB:31:2:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhartiya D, Singh J. FSH-FSHR3-stem cells in ovary surface epithelium: Basis for adult ovarian biology, failure, aging, and cancer. Reproduction. 2015;149:R35–E48. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bang YJ, Kwon JH, Kang SH, Kim JW, Yang YC. Increased MAPK activity and MKP-1 overexpression in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:43–47. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rao A, Herr DR. G protein-coupled receptor GPR19 regulates E-cadherin expression and invasion of breast cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864:1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang Q, Wu J, Zheng F, Hann SS, Chen Y. Emodin increases expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 through activation of MEK/ERK/AMPKα and interaction of PPARγ and Sp1 in lung cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;41:339–357. doi: 10.1159/000456281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Denkert C, Schmitt WD, Berger S, Reles A, Pest S, Siegert A, Lichtenegger W, Dietel M, Hauptmann S. Expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) in primary human ovarian carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:507–513. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hong L, Wang Y, Chen W, Yang S. MicroRNA-508 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells through the MAPK1/ERK signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7431–7440. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee SH, Lee JW, Soung YH, Kim SY, Nam SW, Park WS, Kim SH, Yoo NJ, Lee JY. Colorectal tumors frequently express phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase. APMIS. 2004;112:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm11204-0502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, Van Becelaere K, Wiland A, Gowan RC, Tecle H, Barrett SD, Bridges A, Przybranowski S, et al. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:810–816. doi: 10.1038/10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mader S, Pantel K. Liquid biopsy: Current status and future perspectives. Oncol Res Treat. 2017;40:404–408. doi: 10.1159/000478018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baek JH, Jang JE, Kang CM, Chung HY, Kim ND, Kim KW. Hypoxia-induced VEGF enhances tumor survivability via suppression of serum deprivation-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2000;19:4621–4631. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lefloch R, Pouysségur J, Lenormand P. Total ERK1/2 activity regulates cell proliferation. Cell cycle. 2009;8:705–711. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.5.7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gauthier R, Harnois C, Drolet JF, Reed JC, Vézina A, Vachon PH. Human intestinal epithelial cell survival: Differentiation state-specific control mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1540–C1554. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huang Y, Zou Y, Lin L, Ma X, Zheng R. miR-101 regulates the cell proliferation and apoptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by targeting MEK1 via regulation of the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2019;41:377–386. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shah S, Brock EJ, Ji K, Mattingly RR. Ras and Rap1: A tale of two GTPases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;54:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maemura K, Shiraishi N, Sakagami K, Kawakami K, Inoue T, Murano M, Watanabe M, Otsuki Y. Proliferative effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid on the gastric cancer cell line are associated with extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:688–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kang SK, Tai CJ, Cheng KW, Leung PC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in human ovarian and placental cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;170:143–151. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ma Y, Xu Y, Li L. SPARCL1 suppresses the proliferation and migration of human ovarian cancer cells via the MEK/ERK signaling. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:3195–3201. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sulzmaier FJ, Ramos JW. RSK isoforms in cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6099–6105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sung HY, Yang SD, Ju W, Ahn JH. Aberrant epigenetic regulation of GABRP associates with aggressive phenotype of ovarian cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e335. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu SB, Lin XP, Xu Y, Shen ZF, Pan WW. DAXX promotes ovarian cancer ascites cell proliferation and migration by activating the ERK signaling pathway. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:90. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao J, Ye W, Wu J, Liu L, Yang L, Gao L, Chen B, Zhang F, Yang H, Li Y. Sp1-CD147 positive feedback loop promotes the invasion ability of ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:67–76. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang LQ, Yang SQ, Wang Y, Fang Q, Chen XJ, Lu HS, Zhao LP. Long noncoding RNA MIR4697HG promotes cell growth and metastasis in human ovarian cancer. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst) 2017;2017:8267863. doi: 10.1155/2017/8267863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gialeli C, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Roles of matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression and their pharmacological targeting. FEBS J. 2011;278:16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Maeda-Yamamoto M, Suzuki N, Sawai Y, Miyase T, Sano M, Hashimoto-Ohta A, Isemura M. Association of suppression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation by epigallocatechin gallate with the reduction of matrix metalloproteinase activities in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1858–1863. doi: 10.1021/jf021039l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Simon C, Hicks MJ, Nemechek AJ, Mehta R, O'Malley BW, Jr, Goepfert H, Flaitz CM, Boyd D. PD 098059, an inhibitor of ERK1 activation, attenuates the in vivo invasiveness of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1412–1419. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C, Drula R, Gulei D, Raduly L, Rusu A, Irimie A, Atanasov AG, Slaby O, et al. A comprehensive review on MAPK: A promising therapeutic target in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(pii):E1618. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gao J, Wang Y, Yang J, Zhang W, Meng K, Sun Y, Li Y, He QY. RNF128 promotes invasion and metastasis via the EGFR/MAPK/MMP-2 pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11(pii):E840. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chang MC, Chen CA, Chen PJ, Chiang YC, Chen YL, Mao TL, Lin HW, Lin Chiang WH, Cheng WF. Mesothelin enhances invasion of ovarian cancer by inducing MMP-7 through MAPK/ERK and JNK pathways. Biochem J. 2012;442:293–302. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hohmann T, Dehghani F. The cytoskeleton-A complex interacting meshwork. Cells. 2019;8(pii):E362. doi: 10.3390/cells8040362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bray D. Garland Publishing; New York: 2001. Cell movements, 2nd editionn; p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yamamoto T, Kozawa O, Tanabe K, Akamatsu S, Matsuno H, Dohi S, Uematsu T. Involvement of p38 MAP kinase in TGF-beta-stimulated VEGF synthesis in aortic smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:591–598. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Krishna Priya S, Nagare RP, Sneha VS, Sidhanth C, Bindhya S, Manasa P, Ganesan TS. Tumour angiogenesis-Origin of blood vessels. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:729–735. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Heikenwalder M, Lorentzen A. The role of polarisation of circulating tumour cells in cancer metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:3765–3781. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Javan MR, Khosrojerdi A, Moazzeni SM. New insights into implementation of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer therapy: Prospects for anti-angiogenesis treatment. Front Oncol. 2019;9:840. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Song M, Finley SD. Mechanistic insight into activation of MAPK signaling by pro-angiogenic factors. BMC Syst Biol. 2018;12:145. doi: 10.1186/s12918-018-0668-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Su CM, Su YH, Chiu CF, Chang YW, Hong CC, Yu YH, Ho YS, Wu CH, Yen CS, Su JL. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C upregulates cortactin and promotes metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(Suppl 4):S767–S775. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bhattacharya R, Ray Chaudhuri S, Roy SS. FGF9-induced ovarian cancer cell invasion involves VEGF-A/VEGFR2 augmentation by virtue of ETS1 upregulation and metabolic reprogramming. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:8174–8189. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Soula-Rothhut M, Coissard C, Sartelet H, Boudot C, Bellon G, Martiny L, Rothhut B. The tumor suppressor PTEN inhibits EGF-induced TSP-1 and TIMP-1 expression in FTC-133 thyroid carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhang YH, Wei W, Xu H, Wang YY, Wu WX. Inducing effects of hepatocyte growth factor on the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human colorectal carcinoma cells through MEK and PI3K signaling pathways. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:743–748. doi: 10.1097/00029330-200705010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bian CX, Shi Z, Meng Q, Jiang Y, Liu LZ, Jiang BH. P70S6K 1 regulation of angiogenesis through VEGF and HIF-1alpha expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:395–399. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ping H, Guo L, Xi J, Wang D. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-interacting protein 3a inhibits ovarian carcinoma metastasis via the extracellular HMGA2-mediated ERK/EMT pathway. Tumor Biol. 2017;39:1010428317713389. doi: 10.1177/1010428317713389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.