Abstract

Background

Antenatal care (ANC) is an important opportunity to diagnose and treat pregnancy-related complications and to deliver interventions aimed at improving health and survival of both mother and the infant. Multiple individual studies and national surveys have assessed antenatal care utilization at a single point in time across different countries, but ANC trends have not often been studied in rural areas of low-middle income countries (LMICs). The objective of this analysis was to study the trends of antenatal care use in LMICs over a seven-year period.

Methods

Using a prospective maternal and newborn health registry study, we analyzed data collected from 2011 to 2017 across five countries (Guatemala, India [2 sites], Kenya, Pakistan, and Zambia). Utilization of any ANC along with use of select services, including vitamins/iron, tetanus toxoid vaccine and HIV testing, were assessed. We used a generalized linear regression model to examine the trends of women receiving at least one and at least four antenatal care visits by site and year, controlling for maternal age, education and parity.

Results

Between January 2011 and December 2017, 313,663 women were enrolled and included in the analysis. For all six sites, a high proportion of women received at least one ANC visit across this period. Over the years, there was a trend for an increasing proportion of women receiving at least one and at least four ANC visits in all sites, except for Guatemala where a decline in ANC was observed. Regarding utilization of specific services, in India almost 100% of women reported receiving tetanus toxoid vaccine, vitamins/iron supplementation and HIV testing services for all study years. In Kenya, a small increase in the proportion of women receiving tetanus toxoid vaccine was observed, while for Zambia, tetanus toxoid use declined from 97% in 2011 to 89% in 2017. No trends for tetanus toxoid use were observed for Pakistan and Guatemala. Across all countries an increasing trend was observed for use of vitamins/iron and HIV testing. However, HIV testing remained very low (<0.1%) for Pakistan.

Conclusion

In a range of LMICs, from 2011 to 2017 nearly all women received at least one ANC visit, and a significant increase in the proportion of women who received at least four ANC visits was observed across all sites except Guatemala. Moreover, there were variations regarding the utilization of preventive care services across all sites except for India where rates were generally high. More research is required to understand the quality and influences of ANC.

Keywords: Antenatal care, Low-middle income countries, Maternal health

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are associated with potential major risks for women and newborns and the death of thousands of women and millions of infants worldwide.1 In 2015, an estimated 300,000 women died from pregnancy-related causes.2,3 Although considerable progress has been made over the last twenty years in reducing maternal, fetal and neonatal mortality by improving access to and provision of high quality services during pregnancy, labor, and delivery, high pregnancy-related mortality is still common in many low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).4

Care during pregnancy, also known as antenatal care (ANC), is defined as the care provided by skilled health-care professionals to pregnant women to ensure the best health for both the mother and fetus during pregnancy.5 ANC coverage (at least one visit) is defined as the percentage of 15–49 year old women who received ANC provided by a skilled birth attendant (doctor, nurse or midwife) at least once during pregnancy. Similarly, focused ANC (FANC) is the percentage of women aged 15 to 49 who received ANC four or more times.6 Based on these definitions, countries have assessed their ANC coverage through Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).7 Global data suggest that around 86% of pregnant women access ANC at least once but substantially less (62%) have at least four ANC contacts.6 Moreover, in the regions with the highest rates of maternal mortality, stillbirth and neonatal mortality, sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia, only 52% and 46% of women have at least four ANC contacts, respectively.6 Wide disparities exist in access to four or more ANC visits between rural and urban areas, with a greater than 20% difference between rural and urban areas in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.6 This suggests that that much more work is needed to address ANC utilization and quality.

The timing of initiation of the first ANC visit is important to ensure optimal care and health outcomes both for women and their children.8 Until now, many countries have been following the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations of FANC guidelines, with varying coverage of one to four visits during pregnancy. However, recently, the WHO has also released recommendations to improve the quality of ANC and reduce the risk of pregnancy complications.5,9 According to the WHO, a pregnant woman should have her first ANC visit by 12 weeks’ of gestation, with 7 subsequent visits at between 20 and 40 weeks’ of gestation.9 These new guidelines aim to ensure not only a healthy pregnancy but also an effective transition to labor, delivery and eventually to a positive motherhood experience.9 In addition to recommending specific maternal and fetal assessments, these comprehensive guidelines address nutrition during pregnancy, prevention and treatment of common physiological problems, counseling and support for women facing intimate partner violence and preventative interventions for malaria and/or HIV in endemic areas.5,9 Thus, a positive impact may be achieved through screening for pregnancy problems, assessing pregnancy risk, treating problems that may arise during the antenatal period, giving medication to improve pregnancy outcomes, and for preparing women physically and psychologically for childbirth and parenthood.10,11 In addition, family planning counseling, skilled delivery care, and emergency obstetric care, are key elements of the package of services aimed at improving maternal and newborn health.12,13 Consequently, ANC may lead to further utilization of additional maternal services such as institutional delivery and seeking assistance for complications during delivery and the postnatal period. To reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, coverage of early ANC is one component of the global targets of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.13–15

Rates of ANC coverage are available through many population-based surveys such as the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and national household surveys in LMICs and through routine health management information systems and special perinatal surveys in high-income countries. The limitation of these surveys is that the information is collected retrospectively.16,17 Additionally, many individual studies and surveys have assessed utilization of ANC at one point in time, but trends of ANC across time periods have not often been studied prospectively in LMICs. Thus, our objective was to analyze the trends of ANC use in LMICs over the seven years from 2011 to 2017 using a prospective community-based multi-country research database.18 We also assessed the use of select preventive services at ANC as indicators of the quality of ANC during this period. These trends might be informative for program and policy makers in LMICs at the provincial and national level to improve maternal and child health.

Methods

This analysis was conducted using data from January 2011 through December 2017 from a prospective community-based multi-country study, known as the Maternal and Newborn Health Registry (MNHR) that includes outcomes from rural or semi-urban geographical areas served by government health services. The MNHR data for this study were from communities at six sites in five low-income countries (Chimaltenango, Guatemala; Nagpur District and Karnataka State, India; western Kenya; Thatta District, Pakistan; and Lusaka, Zambia) within the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research Network (GN), which is a network of research teams comprised of LMIC investigators working in partnership with researchers from U.S. institutions. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), a U.S. governmental organization, supports this network.

The methods of the MNHR have been published elsewhere in detail.18,19 In general, each site identified 10 or more geographically-defined communities, each of which represents the catchment area of a primary healthcare center, and approximately 300–500 annual births. The objective of the MNHR study is to enroll pregnant women by 20 weeks’ gestation and to obtain data on pregnancy outcomes for all deliveries that take place within the community. Each community employs registry administrators (RAs) who are paid community health workers or nurses recruited from the local communities. Every RA identifies and tracks these pregnancies and their outcomes in coordination with community elders, birth attendants, and other healthcare workers.

Once a pregnant woman was identified, consented and enrolled, the RA obtained basic health information at the enrollment visit, including the woman’s gestational age. All pregnant women who provided consent were enrolled in the MNHR study; however, for this study analyses, women who miscarried or had a medical termination of pregnancy or were lost to follow-up prior to delivery were excluded.

Follow-up visits are conducted after delivery and at 42-days post-partum. During the follow-up visit, in addition to pregnancy outcome, questions related to ANC are asked regarding the utilization of ANC to determine any ANC received during pregnancy. Receiving any ANC is defined as at least one visit during pregnancy. Likewise, the number of ANC visits are recorded. Moreover, the provision of specific preventive care services such as usage of vitamins/iron, tetanus toxoid (TT) vaccine and HIV testing are also captured as binary responses.

Statistical analysis

The numbers and percentages of women receiving any ANC (i.e., at least one ANC visit) were computed for each site and year. In addition, for women enrolled from 2013 to 2017, the number of ANC visits was collected and the numbers and percentages of women with at least one or at least four ANC visits for those years were computed. Chi-square tests were used to determine whether there was a significant change from the first to last year for each site. Line graphs were created to visualize changes in the number of ANC visits (0, 1, 2, 3, 4+) by year (2013–2017) for each site. Furthermore, a generalized linear regression model was used to examine changes in the percentage of women receiving at least four ANC visits by site and year, controlling for maternal age, education, and parity. We tested a site by year interaction to determine whether changes over time differed across the sites for at least four ANC visits. Similarly, regression analyses were conducted for select preventive care services at ANC. Specifically, we calculated the numbers and percentages of women receiving TT vaccine, vitamins/iron and HIV tests by site and year.

Ethical consideration

This study was reviewed and approved by ethics review committees of all research sites (INCAP, Guatemala; University of Zambia, Zambia; Moi University, Kenya; Aga Khan University, Pakistan; KLE University’s Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Belagavi, India; Lata Medical Research Foundation, Nagpur, India), the institutional review boards at each U.S. partner university and the data coordinating center (RTI International). All women provided informed consent for participation in the study, including data collection and the follow-up visits.

Results

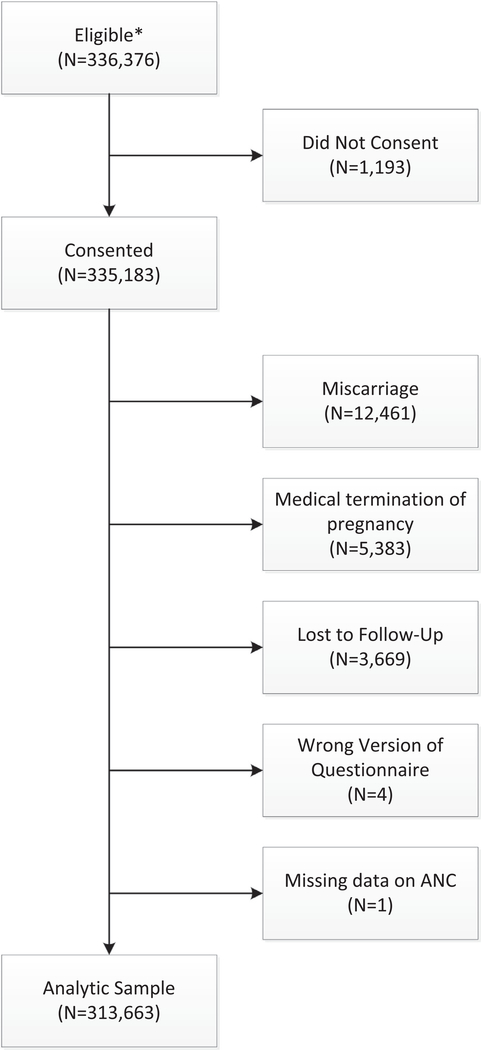

The number of participants screened and enrolled during the study period (2011 through 2017) is provided in Fig. 1. A total of 336,376 women were eligible out of which 335,183 (99.6%) consented to participate in the MNHR. Of those who consented to participate, 21,520 women were excluded due to miscarriages (12,461) medical termination of pregnancy (5383), were lost to follow up (3669), or had missing data (N = 5). Hence, 313,663 women were included in the analyses with the following distribution by site: Belagavi, India (N= 54,631), Guatemala (N = 45,430), Kenya (N = 57,628), Nagpur, India (N = 60,191), Pakistan (N = 46,908) and Zambia (N = 48,875).

Fig. 1–

Sample selection flowchart.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of participating women. The proportion of nulliparous women ranged from 18% in Pakistan to more than 40% in India. The proportion of women with no formal education ranged from 2% in Kenya to 86% in Pakistan. Most of the women were 20–35 years old at the time of enrollment for all sites.

Table 1 –

Demographics by Site and Year.

| Variable | All | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Deliveries | ||||||||

| Zambia | 48875 | 7040 | 6720 | 6760 | 6687 | 7279 | 7348 | 7041 |

| Guatemala | 45430 | 6703 | 6299 | 6779 | 6385 | 6223 | 6761 | 6280 |

| Belagavi, India | 54631 | 8201 | 10393 | 9810 | 7013 | 6844 | 6423 | 5947 |

| Pakistan | 46908 | 8028 | 6776 | 6785 | 6801 | 6402 | 6125 | 5991 |

| Nagpur, India | 60191 | 8670 | 8586 | 9047 | 8796 | 9193 | 8187 | 7712 |

| Kenya | 57628 | 9547 | 8862 | 8381 | 7858 | 7746 | 7668 | 7566 |

| Nulliparous | ||||||||

| Zambia | 14128 (29) | 1902 (27) | 1938 (29) | 1897 (28) | 1879 (28) | 2146 (29) | 2169 (30) | 2197 (31) |

| Guatemala | 12865 (28) | 1772 (26) | 1733 (28) | 1836 (27) | 1832 (29) | 1835 (29) | 1943 (29) | 1914 (30) |

| Belagavi, India | 21728 (40) | 3356 (41) | 4205 (40) | 4036 (41) | 2762 (39) | 2685 (39) | 2471 (38) | 2213 (37) |

| Pakistan | 8067 (18) | 1600 (20) | 1407 (21) | 1230 (18) | 819 (12) | 680 (11) | 1095 (18) | 1236 (21) |

| Nagpur, India | 29241 (49) | 4276 (49) | 4140 (48) | 4211 (47) | 4190 (48) | 4496 (49) | 4075 (50) | 3853 (50) |

| Kenya | 16652 (29) | 2315 (24) | 2335 (26) | 2210 (26) | 2325 (30) | 2427 (31) | 2409 (31) | 2631 (35) |

| No formal schooling | ||||||||

| Zambia | 4395 (9) | 815 (12) | 727 (11) | 638 (9) | 714 (11) | 568 (8) | 450 (6) | 483 (7) |

| Guatemala | 8325 (18) | 1573 (23) | 1274 (20) | 1244 (18) | 1084 (17) | 1104 (18) | 1107 (16) | 939 (15) |

| Belagavi, India | 9365 (17) | 1711 (21) | 2380 (23) | 1954 (20) | 1072 (15) | 901 (13) | 744 (12) | 603 (10) |

| Pakistan | 40219 (86) | 6988 (87) | 6010 (89) | 5799 (85) | 5743 (84) | 5346 (84) | 5188 (85) | 5145 (86) |

| Nagpur, India | 1867 (3) | 262 (3) | 246 (3) | 224 (2) | 389 (4) | 389 (4) | 219 (3) | 138 (2) |

| Kenya | 1296 (2) | 296 (3) | 239 (3) | 241 (3) | 169 (2) | 137 (2) | 134 (2) | 80 (1) |

| Maternal age at enrollment | ||||||||

| Zambia | ||||||||

| < 20 | 12084 (25) | 1803 (26) | 1838 (27) | 1737 (26) | 1613 (24) | 1736 (24) | 1710 (23) | 1647 (23) |

| 20–35 | 32742 (67) | 4660 (66) | 4341 (65) | 4509 (67) | 4506 (67) | 4968 (68) | 4974 (68) | 4784 (68) |

| > 35 | 3995 (8) | 570 (8) | 522 (8) | 501 (7) | 557 (8) | 572 (8) | 663 (9) | 610 (9) |

| Guatemala | ||||||||

| < 20 | 7592 (17) | 1099 (16) | 1017 (16) | 1047 (15) | 1074 (17) | 1107 (18) | 1165 (17) | 1083 (17) |

| 20–35 | 33117 (73) | 4869 (73) | 4615 (73) | 5033 (74) | 4626 (72) | 4485 (72) | 4915 (73) | 4574 (73) |

| > 35 | 4715 (10) | 732 (11) | 666 (11) | 697 (10) | 685 (11) | 631 (10) | 681 (10) | 623 (10) |

| Belagavi, India | ||||||||

| < 20 | 5818 (11) | 872 (11) | 961 (9) | 843 (9) | 719 (10) | 793 (12) | 753 (12) | 877 (15) |

| 20–35 | 48631 (89) | 7303 (89) | 9395 (90) | 8943 (91) | 6272 (89) | 6026 (88) | 5649 (88) | 5043 (85) |

| > 35 | 152 (0) | 20 (0) | 20 (0) | 19 (0) | 20 (0) | 25 (0) | 21 (0) | 27 (0) |

| Pakistan | ||||||||

| < 20 | 1647 (4) | 269 (3) | 197 (3) | 198 (3) | 178 (3) | 368 (6) | 240 (4) | 197 (3) |

| 20–35 | 42525 (91) | 7218 (90) | 6213 (92) | 6292 (93) | 6313 (93) | 5705 (89) | 5408 (88) | 5376 (90) |

| > 35 | 2686 (6) | 511 (6) | 357 (5) | 291 (4) | 305 (4) | 327 (5) | 477 (8) | 418 (7) |

| Nagpur, India | ||||||||

| < 20 | 1280 (2) | 167 (2) | 183 (2) | 176 (2) | 187 (2) | 182 (2) | 179 (2) | 206 (3) |

| 20–35 | 58629 (97) | 8478 (98) | 8360 (97) | 8831 (98) | 8563 (97) | 8971 (98) | 7970 (97) | 7456 (97) |

| > 35 | 260 (0) | 24 (0) | 34 (0) | 30 (0) | 46 (1) | 40 (0) | 37 (0) | 49 (1) |

| Kenya | ||||||||

| < 20 | 12881 (22) | 2023 (21) | 1960 (22) | 1902 (23) | 1817 (23) | 1703 (22) | 1695 (22) | 1781 (24) |

| 20–35 | 42198 (73) | 7079 (74) | 6549 (74) | 6107 (73) | 5683 (72) | 5685 (73) | 5652 (74) | 5443 (72) |

| > 35 | 2445 (4) | 431 (5) | 344 (4) | 355 (4) | 350 (4) | 341 (4) | 303 (4) | 321 (4) |

Table 2 shows the trend of the proportions of women receiving at least one ANC visit by site and by year. The rates were generally high reaching close to 100% for nearly all the sites. For both Indian sites, nearly 100% of women received at least one visit each year. In Pakistan, the percentage of women with at least one ANC visit increased significantly from 86% in 2011 to 97% in 2017 (p<0.001). However, in Guatemala, the percentage of women receiving at least one ANC visit decreased from 97% in 2011 to 94% in 2017 (p<0.001).

Table 2 –

Antenatal Care by Site and Year.

| Variable | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Last – first year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | % difference | p-value | |

| At least one antenatal care visit | |||||||||

| Zambia | 7001 (99) | 6691 (100) | 6740 (100) | 6683 (100) | 7274 (100) | 7339 (100) | 7030 (100) | 0.39 | < 0.001 |

| Guatemala | 6514 (97) | 6206 (99) | 6706 (96) | 6124 (96) | 5791 (93) | 6371 (94) | 5933 (94) | −2.71 | < 0.001 |

| Belagavi, India | 8200 (100) | 10390 (100) | 9802 (100) | 7006 (100) | 6841 (100) | 6421 (100) | 5946 (100) | −0.01 | 0.820 |

| Pakistan | 6930 (86) | 5839 (86) | 5932 (87) | 6271 (92) | 6128 (96) | 5892 (96) | 5803 (97) | 10.54 | < 0.001 |

| Nagpur, India | 8656 (100) | 8582 (100) | 9038 (100) | 8722 (99) | 9182 (100) | 8186 (100) | 7711 (100) | 0.15 | 0.002 |

| Kenya | 9261 (97) | 8721 (98) | 8296 (99) | 7762 (99) | 7684 (99) | 7609 (99) | 7399 (98) | 0.79 | 0.001 |

| At least two antenatal care visits | |||||||||

| Zambia | 6384 (94) | 6385 (95) | 6870 (94) | 7037 (96) | 6753 (96) | 1.36 | < 0.001 | ||

| Guatemala | 6591 (97) | 5843 (92) | 5397 (87) | 5943 (88) | 5583 (89) | −8.34 | < 0.001 | ||

| Belagavi, India | 9766 (100) | 6928 (99) | 6776 (99) | 6389 (99) | 5923 (100) | −0.01 | 0.877 | ||

| Pakistan | 4446 (66) | 5056 (74) | 5273 (82) | 4897 (80) | 4990 (83) | 17.72 | < 0.001 | ||

| Nagpur, India | 8740 (97) | 8592 (98) | 9040 (98) | 8133 (99) | 7666 (99) | 1.72 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kenya | 7935 (95) | 7407 (94) | 7397 (95) | 7397 (96) | 6948 (92) | −2.86 | < 0.001 | ||

| At least four antenatal care visits | |||||||||

| Zambia | 1519 (22) | 2124 (32) | 2710 (37) | 3323 (45) | 3890 (55) | 32.75 | < 0.001 | ||

| Guatemala | 5522 (81) | 4358 (68) | 3692 (59) | 3972 (59) | 3823 (61) | −20.59 | < 0.001 | ||

| Belagavi, India | 6759 (69) | 4278 (61) | 4795 (70) | 4925 (77) | 4844 (81) | 12.51 | < 0.001 | ||

| Pakistan | 1760 (26) | 2051 (30) | 2651 (41) | 2252 (37) | 2408 (40) | 14.24 | < 0.001 | ||

| Nagpur, India | 6779 (75) | 6754 (77) | 7673 (83) | 7495 (92) | 7249 (94) | 18.24 | < 0.001 | ||

| Kenya | 3750 (45) | 3523 (45) | 4393 (57) | 4823 (63) | 3962 (52) | 7.62 | < 0.001 | ||

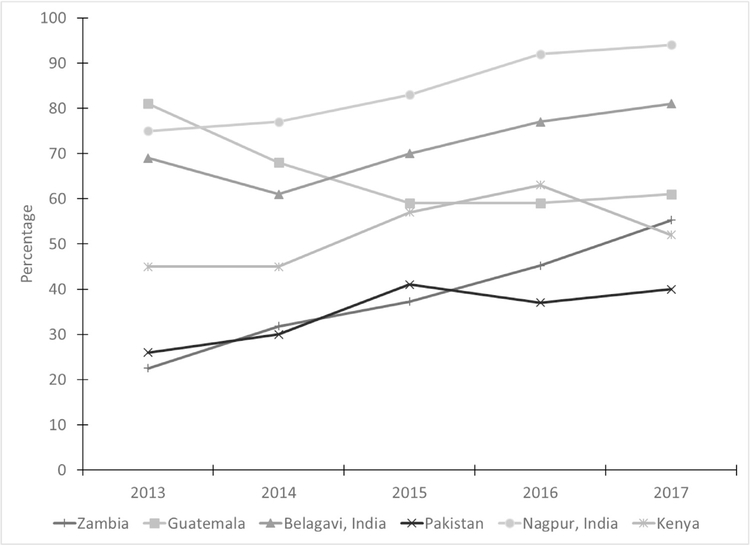

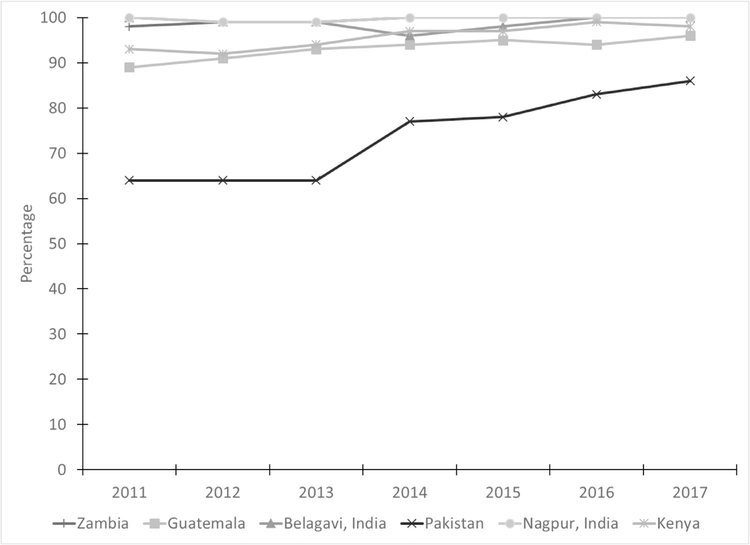

The percentages of women receiving at least four ANC visits were substantially lower; however, except for Guatemala, these percentages increased significantly over time (p<0.001) (Table 2). These trends remained significant after controlling for demographic characteristics (Fig. 2). The site by year interaction was significant (p<0.001), indicating that trends varied significantly by site.

Fig. 2– Percentage of women with at least four antenatal care visits by year and site.

Note: Site x year interaction was significant, controlling for maternal age, education, and parity (p < 0.001).

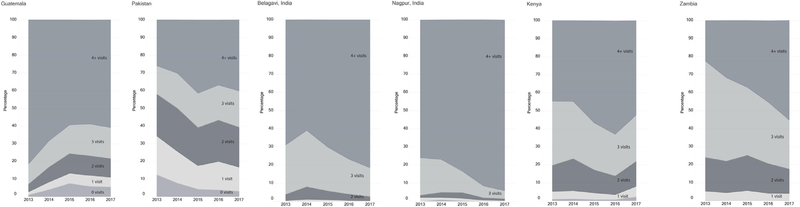

Fig. 3 graphically displays changes in the number of ANC visits over time according to site. In Guatemala, the rates for women with 0, 1, 2, and 3 ANC visits increased over time, while the percentage receiving 4+ ANC visits decreased. For other sites, the proportion of 4+ visits increased over time. In some sites, the increase in the percentage of those with 4+ visits seems to be related to a reduction in the percentage of those with 3 visits. For example, in Zambia, the proportion of women with 1 or 2 ANC visits was consistent over time while those with 4+ visits increased and those with 3 visits decreased.

Fig. 3–

Percentage of women by number of antenatal care visits, year, and site.

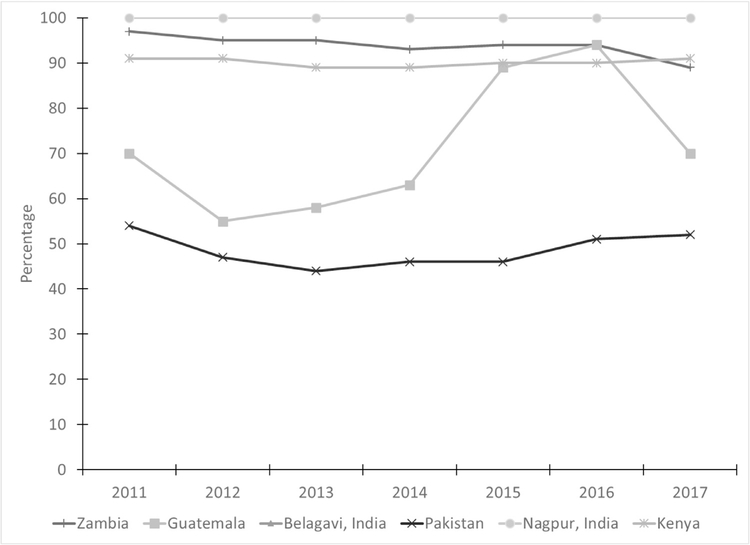

The percentage of women receiving various types of preventive care during ANC are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 4. Similar to the results for at least one ANC visit, in the Indian sites, 100% of women received the TT vaccine, while in Kenya use remained between 89% and 91% over the study period. In Pakistan, the percentage receiving TT vaccine remained low over time with values ranging from 44% to 54%. In Guatemala, the TT coverage increased from 55% in 2012 to 94% in 2016; however, in 2017, the percentage dropped to 70%. Zambia had a significant decrease in the coverage of women receiving TT vaccine over time from 97% in 2011 to 89% in 2017 (p< 0.001).

Table 3 –

Preventive Care by Site and Year.

| Variable | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Last – first year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | % difference | p-value | |

| Tetanus toxoid vaccine | |||||||||

| Zambia | 6818 (97) | 6394 (95) | 6408 (95) | 6194 (93) | 6819 (94) | 6939 (94) | 6256 (89) | −8.00 | < 0.001 |

| Guatemala | 4715 (70) | 3434 (55) | 3910 (58) | 4002 (63) | 5553 (89) | 6348 (94) | 4388 (70) | −0.47 | 0.560 |

| Belagavi, India | 8196 (100) | 10377 (100) | 9794 (100) | 6995 (100) | 6835 (100) | 6415 (100) | 5934 (100) | −0.16 | 0.009 |

| Pakistan | 4330 (54) | 3194 (47) | 3009 (44) | 3158 (46) | 2937 (46) | 3106 (51) | 3111 (52) | −2.01 | 0.018 |

| Nagpur, India | 8661 (100) | 8567 (100) | 9010 (100) | 8775 (100) | 9165 (100) | 8176 (100) | 7694 (100) | −0.13 | 0.041 |

| Kenya | 8719 (91) | 8053 (91) | 7481 (89) | 6954 (89) | 6988 (90) | 6920 (90) | 6887 (91) | −0.30 | 0.490 |

| Vitamins/iron | |||||||||

| Zambia | 6915 (98) | 6654 (99) | 6710 (99) | 6668 (100) | 7266 (100) | 7329 (100) | 7026 (100) | 1.57 | < 0.001 |

| Guatemala | 5984 (89) | 5737 (91) | 6337 (93) | 6015 (94) | 5884 (95) | 6380 (94) | 6027 (96) | 6.50 | < 0.001 |

| Belagavi, India | 8184 (100) | 10336 (99) | 9710 (99) | 6742 (96) | 6722 (98) | 6391 (100) | 5924 (100) | −0.19 | 0.032 |

| Pakistan | 5176 (64) | 4362 (64) | 4329 (64) | 5218 (77) | 5003 (78) | 5109 (83) | 5150 (86) | 21.47 | < 0.001 |

| Nagpur, India | 8656 (100) | 8471 (99) | 8968 (99) | 8765 (100) | 9161 (100) | 8166 (100) | 7686 (100) | −0.18 | 0.023 |

| Kenya | 8855 (93) | 8196 (92) | 7903 (94) | 7643 (97) | 7536 (97) | 7564 (99) | 7438 (98) | 5.56 | < 0.001 |

| HIV test | |||||||||

| Zambia | 6872 (98) | 6618 (98) | 6670 (99) | 6655 (100) | 7258 (100) | 7325 (100) | 6964 (100) | 1.30 | < 0.001 |

| Guatemala | 2045 (31) | 3107 (49) | 4193 (62) | 4237 (66) | 4592 (74) | 5078 (75) | 4885 (78) | 47.28 | < 0.001 |

| Belagavi, India | 8140 (99) | 10301 (99) | 9717 (99) | 6983 (100) | 6828 (100) | 6414 (100) | 5930 (100) | 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| Pakistan | 28 (0) | 14 (0) | 31 (0) | 33 (0) | 40 (1) | 23 (0) | 26 (0) | 0.08 | 0.420 |

| Nagpur, India | 8542 (99) | 8437 (98) | 8936 (99) | 8721 (99) | 9129 (99) | 8149 (100) | 7687 (100) | 1.16 | < 0.001 |

| Kenya | 8974 (94) | 8400 (95) | 8022 (96) | 7554 (96) | 7647 (99) | 7568 (99) | 7371 (97) | 3.42 | < 0.001 |

Fig. 4– Percentage of women receiving tetanus toxoid vaccine by site and year.

Note: Site x year interaction was significant, controlling for maternal age, education, and parity (p < 0.001).

Prenatal vitamins/iron use was nearly 100% across all years in Zambia and the two Indian sites (Table 3, Fig. 5). Although Guatemala and Kenya already had high proportions of women using prenatal vitamins and iron in 2011 (89% and 93%, respectively), the use over time increased to 96% and 98%, respectively. The greatest change was observed for Pakistan with a substantial increase from 64% in 2011 to 86% in 2017.

Fig. 5– Percentage of women receiving prenatal vitamins/iron by site and year.

Note: Site x year interaction was significant, controlling for maternal age, education, and parity (p < 0.001).

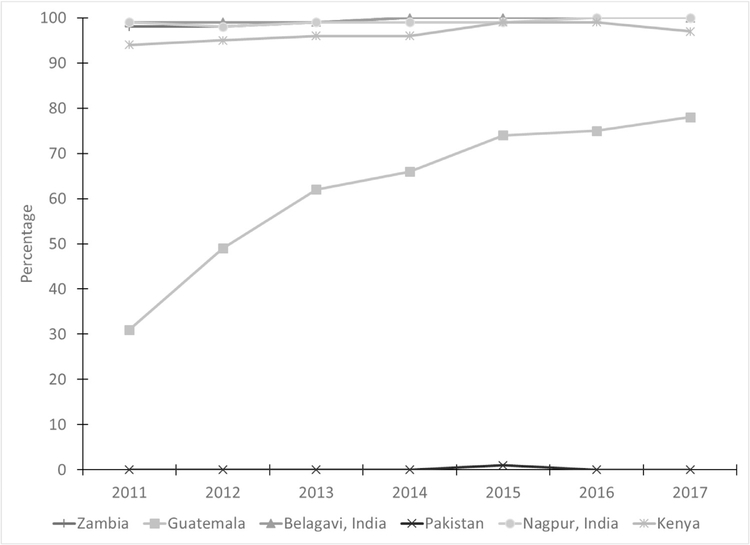

The percentage of women receiving an HIV test increased across all sites except Pakistan (p< 0.001; Table 3, Fig. 6). Usage in Pakistan remained close to zero as HIV testing is not standard practice. High rates for HIV testing were observed for both African and Indian sites at 94% or higher. Guatemala had lower percentages of HIV testing but the percentage steadily increased over the time from 31% in 2011 to 78% in 2017.

Fig. 6– Percentage of women receiving HIV test by site and year.

Note: Site x year interaction was significant, controlling for maternal age, education, and parity (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the trends of ANC visits based on prospectively collected data from six sites in five countries. In summary, most of the women across all sites used ANC services at least once. With the exception of Guatemala, the overall trend for at least one ANC visit increased for most of the sites or remained consistent. However, for Guatemala, there was a significant decrease in the receipt of at least one ANC visit over the seven years. For at least four ANC visits, there was an increasing trend for all sites from 2011 to 2017 except for the Guatemala site where the opposite trend was observed.

Regarding the utilization of specific preventive care services at ANC, for TT use, no consistent trend was observed; however, a trend of increased use of iron/vitamin was observed for all sites. There was an increasing trend for HIV testing over the period for all sites except for Pakistan, where HIV testing is not part of routine ANC.

Our results for ANC care use are consistent with some of the DHS surveys of the participating countries. For example, DHS surveys from Pakistan showed that ANC utilization has increased over the last twenty-five years.20–23 The percentage of women making at least four ANC visits remained low in the early years but substantially increased over the last two decades.20–23 These surveys showed that the overall proportion of TT vaccine use was lower in Pakistan compared to the other sites, but with an increasing trend over the last two decades.20–23

Similarly, three different national health surveys for India also showed an increasing trend for both one and at least four ANC visits over the last twenty years.24–26 Likewise, increasing trends were observed for the percentage of women utilizing at least four visits and TT vaccines.24–26 The DHS results showed similar trends for Kenya, however, the proportion of women utilizing at least one ANC visit was quite high in 1998 to begin with and increased slightly in 2014.27–29 Likewise, the proportion of women having at least four visits was found to be high relative to surveys conducted in India and Pakistan.27–29 Furthermore, these surveys showed the fluctuations of TT vaccine utilization over the last fifteen years.27–29 DHS conducted in Zambia have also shown similar trends with a higher percentage of women receiving at least one visit and showing declining trends for at least four visits.30–33 However, for TT vaccine utilization, these surveys showed no clear trends.30–33 In contrast to our study findings, for Guatemala, national DHS have shown an increasing trend for at least one and four ANC visits from 1998 to 2015.34–36 Based on our study findings, the reasons for the decline in ANC visits trend for Guatemala may need to be explored further in future studies.

The possible reasons for the increasing trend in ANC visits for different study sites may be explained by the many initiatives taken by the government and non-government organizations (NGOs) for increasing awareness regarding ANC among women of reproductive age. For example, the Government of Pakistan has been providing maternal and child health services through two national programs, the National Program for Family Planning and Primary Health Care (Lady Health Workers (LHW) Programme and the National Maternal and Child Health Program since 1994 and 1996, respectively.37,38 These programs aim to not only create awareness regarding maternal and child health services including ANC but also provide basic maternal and child health services through LHWs and community midwives. Likewise, in India, promotion of maternal and child health has been one of the most important components of the Family Welfare Programme of the Government of India and the National Population Policy–2000 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2000). In 1996, the Indian Government incorporated safe motherhood and child health services into the Reproductive and Child Health Programme with the main components including the provision of ANC, iron prophylaxis, two doses of TT vaccine, detection, and treatment of anemia in mothers, and management and referral of high-risk pregnancies.39 Similarly, since 1967, the Kenya government has been promoting an integrated maternal and child health/family planning program with the dual objectives of enhancing the welfare of both mothers and children and reducing fertility.40 Moreover, the government of Kenya has also introduced a FANC model as recommended by the WHO.41 FANC guidelines recommend that a pregnant woman should have four comprehensive ANC visits, and be screened and treated for anemia, malaria, HIV/AIDS, and also be immunized against tetanus.41 The FANC model was introduced into the National Health Strategic Plan of Zambia in 200542. This model also intended to reduce waiting times, increase the time spent educating women about pregnancy and reduce the cost of medical care for the family.42

In addition to the various government initiatives, women are also provided information about ANC through initiatives conducted by NGOs. For example, a community based trial in Thatta, Pakistan, Belagavi, India and Guatemala began in 2012, where in addition to the main study objectives, home visitor research assistants (HVRAs) sensitized pregnant women about ANC during their biweekly visits and motivated them to seek the ANC services from nearby facilities.43 HVRAs also provided supplements containing macro- and micro-nutrients and iron tablets to women at their home. This might be one of the reasons explaining the rise in vitamins or iron uptake for these sites.43

Thus, regarding the preventive services, the proportion of pregnant women utilizing vitamins or iron was either high or showed an increasing trend for all countries, but TT vaccine and HIV testing did not increase. This might be because vitamins or iron in oral form can still be provided to women by health workers in their homes, but HIV testing and TT vaccination are generally provided within a facility. Moreover, in order to obtain the complete two doses of TT vaccine, women must visit a health care facility at least twice.

The higher percentages of women getting HIV testing done during pregnancy can be explained by the fact that three of the sites (India, Kenya, and Zambia) have policies and laws on HIV testing during pregnancy.44 These policies and laws often provide an opportunity for pregnant women to get free HIV screening and treatment services.44 Similarly, in 2010 the Guatemalan National Congress approved the National Law for a Healthy Maternity and the National Plan to promote maternal and neonatal health, which may help explain the rising trend for HIV testing during pregnancy.45 On the other hand, Pakistan, does not have policies requiring HIV testing.

The decrease in ANC coverage in the Chimaltenango area of Guatemala is likely explained by a 2014 government decision to eliminate an outreach program that increased ANC coverage.46 This program has not been replaced with other options to improve ANC coverage. The change occurred at the end of 2014, and likely explains our findings of decreased ANC in the Guatemala site since that time.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths including that it was population-based and did not rely solely on hospital data. Second, even though the DHS provides data on ANC coverage for many of the countries included in this study, one of the strengths of our study is that it is more recent, with prospectively collected data, unlike the DHS surveys which collect data retrospectively. Third, the data were collected from a large cohort of more than 300,000 births. To our knowledge, this is among the first studies that assessed trends of ANC in LMICs of South Asia, Africa and Latin America with a good representation of varied community-based sites.

This study had a number of potential limitations. First, despite the large sample size, these data were collected in relatively small, often rural areas of each of the countries and are not representative samples from the countries. Second, we did not determine the trimester (gestational age), during which a pregnant mother availed ANC service. In addition, while assessing ANC care during pregnancy, we did not ask women about the number of doses of TT vaccine administered to her during pregnancy, which trimester the TT vaccine was administered and for how long the women used vitamins or iron during pregnancy. Moreover, the information about TT vaccine use was mainly based on the recall of mother at the time of delivery.

Conclusion

Progress in the coverage of ANC as well as certain measures of ANC quality have been achieved in nearly all study sites, but coverage and high-quality care is still far from universal. More research is required to better understand reasons for poor ANC coverage and quality, as well as how to improve the quantity and quality of that care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robinson M, Pennell CE, McLean NJ, Tearne JE, Oddy WH, Newnham JP. Risk perception in pregnancy. Eur Psychol. 2015;20:120–127. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO, UNICEF. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2015: estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division, WHO, UNICEF; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(2):e98–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Requejo JH, Bryce J, Barros AJ, et al. Countdown to 2015 and beyond: fulfilling the health agenda for women and children. Lancet. 2015;385(9966):466–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNICEF. Antenatal care data. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 7.Abou-Zahr CL, Wardlaw TM. WHO. Antenatal Care in Developing Countries: Promises, Achievements, and Missed Opportunities: An Analysis of Trends, Levels and Differentials, 1990–2001. WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moller A-B, Petzold M, Chou D, Say L. Early antenatal care visit: a systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013. Lancet Global Health. 2017;5(10):e977–e983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [cited 23 October 2018]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/news/antenatalcare/en/. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saad-Haddad G, DeJong J, Terreri N, et al. Patterns and determinants of antenatal care utilization: analysis of national survey data in seven countdown countries. J Global Health. 2016;6(1): 010404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pell C, Meñaca A, Were F, et al. Factors affecting antenatal care attendance: results from qualitative studies in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. PloS One. 2013;8(1):e53747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York; 2015. [cited 2018 23 October 2018]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.html. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO, Mathers C Global strategy for women’s, children’s andadolescents’ health (2016–2030). 2016. WHO; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Every Newborn: an action plan toend preventable deaths. 2014. Available at: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/newborns/every-newborn/en/. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 16.Measure Evaluation. Demographic and Health Surveys.Available at: http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/dhs. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 17.Gottlieb CA, Maenner MJ, Cappa C, Durkin MS. Child disability screening, nutrition, and early learning in 18 countries with low and middle incomes: data from the third round of UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (200506). Lancet. 2009;374(9704):1831–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goudar SS, Carlo WA, McClure EM, et al. The maternal and newborn health registry study of the global network for women’s and children’s health research. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2012;118(3):190–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bose CL, Bauserman M, Goldenberg RL, et al. The Global Network Maternal Newborn Health Registry: a multi-national, community-based registry of pregnancy outcomes. Reprod Health. 2015;12(2):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan], andMacro International Inc. 2008. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006–07. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Population Studies and Macro International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan], andMacro International Inc. 2014. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Population Studies and Macro International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan], and Macro International Inc. 2018. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Islamabad,Pakistan: National Institute of Population Studies and Macro International Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute of Population Studies. Pakistan Demographicand Health Survey 1990/1991. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR29/FR29.pdf. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 24.India National Family Health Survey. 1998–1999 (NFHS2). Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/frind2/frind2.pdf. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 25.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) andMacro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I Mumbai: IIPS; Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/frind3/00frontmatter00.pdf Accessed 14 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare International Institutefor Population Sciences Deonar Mumbai. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 20152016. Available at: http://rchiips.org/nfhs. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 27.National Council for Population and development (NCPD), Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) (Office of the Vice President and Ministry of Planning and National Development) [Kenya], and Macro International Inc. (MI). 1999. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 1998. Calverton, Maryland: NDPD, CBS, and MI; Available at: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR102/FR102.pdf. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro.2010. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 200809. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; Source: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr229/fr229.pdf. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health/Kenya,National AIDS Control Council/Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, Population NCf, Development/Kenya. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014; Rockville, MD, USA: 2015. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-fr308-dhs-final-reports.cfm. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Central Statistical Office [Zambia] and Ministry of Health and Macro International Inc. 1997. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey, 1996. Calverton, Maryland: Central Statistical Office and Macro International Inc; Available at: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR86/FR86.pdf. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Central Statistical Office [Zambia], Central Board of Health[Zambia], and ORC Macro. 2003. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2001–2002. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Central Board of Health, and ORC Macro; Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Central Statistical Office (CSO), Ministry of Health (MOH), Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC), University of Zambia, and Macro International Inc. 2009. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSO and Macro International Inc; Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Zambia], Ministry of Health(MOH) [Zambia], and ICF International. 2014. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2013–14. Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, and ICF International; Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 34.InstitutoNacionalde Estadística -INE/Guatemala, Macro International. Guatemala Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil 1995. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Instituto Nacional de Estadística - INE/Guatemala and Macro International, 1996. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR70-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Instituto Nacional de Estadística INE/Guatemala, Macro International. Guatemala Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil 1998–1999. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE/Guatemala and Macro International, 1999. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR107-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm. Accessed 13 April, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(INE) MoPHaSAMNIoS. Guatemala VI National Survey of Maternal and Child Health (ENSMI) 2014–2015 Report. (INE) MoPHaSAMNIoS; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhutta ZA, Memon ZA, Soofi S, Salat MS, Cousens S, Martines J. Implementing community-based perinatal care: results from a pilot study in rural Pakistan. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ministry of Health, Government of Pakistan. Pakistan National Maternal and Child Health Programme. 2007. Accessed 13 April, 2019.

- 39.Kumar V, Singh P. How far is universal coverage of antenatal care (ANC) in India? An evaluation of coverage and expenditure from a national survey. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2017;5(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikamari LD. Maternal health care utilization in Teso District. Afr J Health Sci. 2004;11(1):21–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gitonga E Determinants of focused antenatal care uptake among women in Tharaka Nithi county, Kenya. Adv Public Health; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chama-Chiliba CM, Koch SF. Utilization of focused antenatal care in Zambia: examining individual and community-level factors using a multilevel analysis. Health Policy Plan.2013;30(1):78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hambidge KM, Krebs NF, Westcott JE, et al. Preconception maternal nutrition: a multi-site randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maman S, Groves A, King E, Pierce M, Wyckoff S. HIV testing during pregnancy: A literature and policy review, New York: Open Society Institute; 2008; 790:60. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Washington DC. Reproductive Health and Healthy Motherhood: Aligning National Legislation with International Human Rights Law. 2014.

- 46.Carlos Á, Bright R, Gutiérrez J, Hoadley K, Manuel C, Romero N, Rodríguez MP Guatemala, Analisis del Sistema de Salud 2015 - Resumen Ejecutivo. Bethesda, MD: Proyecto Health Finance and Governance, Abt Associates Inc. [Google Scholar]