Abstract

Background

There is a growing body of evidences indicating iNOS has involved in the pathogenesis of SLE. However, the role of iNOS in SLE is inconsistency. This systematic review was designed to evaluate the association between iNOS and SLE.

Results

Six studies were included, reporting on a total of 277 patients with SLE. The meta-analysis showed that SLE patients had higher expression of iNOS at mRNA level than control subjects (SMD = 2.671, 95%CI = 0.446–4.897, z = 2.35, p = 0.019), and a similar trend was noted at the protein level (SMD = 3.602, 95%CI = 1.144–6.059, z = 2.87, p = 0.004) and positive rate of iNOS (OR = 9.515, 95%CI = 1.915–47.281, z = 2.76, p = 0.006) were significantly higher in SLE group compared with control group. No significant difference was observed on serum nitrite level between SLE patients and control subjects (SMD = 2.203, 95%CI = -0.386–4.793, z = 1.64, p = 0.095). The results did not modify from different sensitivity analysis, representing the robustness of this study. No significant publication bias was detected from Egger’s test.

Conclusions

There was a positive correlation between increasing iNOS and SLE. However, the source of iNOS is unknown. Besides NO pathway, other pathways also should be considered. More prospective random studies are needed in order to certify our results.

Background

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, autoimmune disease characterized by a variety of clinical symptoms, producing autoantibodies and causing damage to multiple organs [1–3]. However, the pathogenesis of SLE remains unclear. Up to now, T-cell and B-cell abnormalities, impaired apoptotic debris clearance, abnormal cytokines and autoantibody productions have been partially set forth [4]. In recent years, free radical-mediated reactions have been implicated as contributions in a range of autoimmune diseases, including SLE [5, 6].

Nitric oxide (NO) is one of the most important and widely studied free radical molecules. It plays an important role in the regulation of physiological processes, host defense, anti-inflammation under physiologic conditions [7, 8]. Conversely, it serves as a cytotoxic effector molecule or a pathogenic mediator of tissue destruction when over-expressed [9]. Previous study showed NO is an important mediator of apoptosis and a vital regulator of the Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmune diseases [10]. Furthermore, over-expression of NO was parallel with the development of SLE [11, 12]. However, NO is unstable, its potential in SLE pathogenesis lies largely on the extent of its production and generation of O2▪ -, leading to formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−). ONOO− is one of reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which induced tissue injury via direct oxidant, protein tyrosine nitration and nucleic acid modification [5, 13–15]. In addition, it can penetrate the cellular membranes directly and oxidate protein side-chains which may be related to oxidative cell injury [16, 17]. Alteration of protein can generate neo-epitopes, which may be effective in activating T cells, leading to autoimmune attack. Accumulating evidence showed a positive association between RNS and SLE [14, 18]. Meanwhile, blocking RNS can reduce disease activity [19]. Moreover, it had been showed that NO production, such as nitrate and nitrite, as well as RNS-modified proteins, such as 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) were elevated in SLE [20, 21]. Therefore, NO plays an important role in SLE via different ways. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS) is the synthase catalyze L-arginine to form NO.

There are three isoforms of NOS: neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NOS (iNOS). In contrast with the former two isoforms, iNOS is an inducible and calcium-independent synthase. Studies in murine models have shown that iNOS is induced in response to inflammatory stimuli, and iNOS can produce much higher amounts of NO than the other two isoforms. More and more evidence showed a positive correlation between increasing iNOS activity and progression of SLE. Clinical data showed that iNOS elevated in endothelial cells, keratinocytes and renal tissue cells in SLE patients [22]. In animal models of SLE, increased NO and iNOS expression were observed [23]. Studies from both human and animals showed that iNOS over-expression has a positive association with autoimmune diseases [24]. iNOS inhibitor prevents glomerulonephritis developing in MRL/lpr mice [25, 26], which suggests that iNOS promote the development and progression of SLE. A recent study with MRL/lpr mice suggested iNOS promoted the proliferation of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells [27], which were thought to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of SLE though promoting B cells to produce more IgG [28, 29]. A positive correlation between iNOS and SLE had emerged. However, Bronte et al. indicated that iNOS can limit the functions of autoreactive T cells and reduce disease severity [30]. Meanwhile, a recent study by using NOS2−/− MRL/lpr mice showed a lower level of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and a higher level of triglycerides, ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) which aggravate vascular inflammatory processes, suggesting that iNOS may relieve SLE symptoms in some conditions [31]. Collectively, these data suggested a pathogenic role of iNOS in SLE. However, the role is controversial. Herein, we conducted this meta-analysis to explore the association between iNOS and SLE.

Results

Studies included

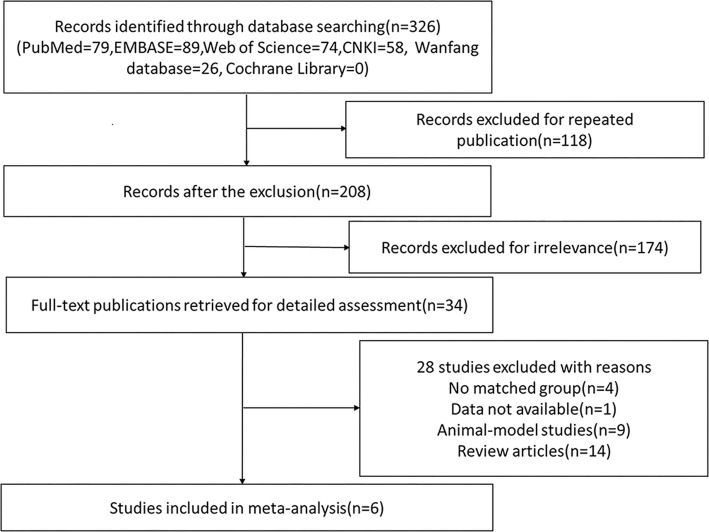

The detailed search process was showed in the flow diagram (Fig. 1). The search strategy retrieved 326 potentially relevant studies, which included 79 articles from PubMed, 89 from EMBASE, 74 from Web of Science, 58 from CNKI, 26 from Wanfang database, 0 from Cochrane Library. After excluding duplicate and irrelevant publications, 34 articles were scrutinized. According to the inclusion criteria, 6 articles were included in this meta-analysis finally [22, 32–36]. Total sample sizes of the 6 studies were 277, including 184 patients with SLE and 93 control subjects.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for identification of relevant studies

Study characteristics

The major characteristics of the included studies were summarized in Table 1. All of them were designed as case-control studies. The age and gender were matched between SLE patients and control subjects in each included study. Of these, subjects of 3 studies [22, 33, 35] were fulfilled the criteria of the ARA for SLE diagnosis, the other 3 [32, 34, 36] were diagnosed according to ACR. The tissues used for evaluating iNOS expression were as follows: In studies of Belmont [32] and Kuhn [22] skin was evaluated, in studies of Gong [33] and Xu [34], peripheral blood was evaluated, and in the other 2 studies [35, 36] kidney was evaluated. The quality of included studies was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. All studies showed high quality for achieving a rating of 5 stars or higher (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Study design | Sample size (SLE/control) | Gender of SLE(F/M) | Mean age of SLE(y) | Criteria of SLE diagnosis | Type of tissue/cell used in studies | Characteristics of controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belmont 1997 [32] | Case-control | 36(25/11) | NG | NG | ACR | Skin: endothelial cell, keratinocyte | Skin biopsy samples obtained from young, healthy, female volunteers |

| Kuhn 1998 [22] | Case-control | 26(21/5) | NG | NG | ARA | Skin: keratinocyte | Non-lesional skin from healthy people |

| Gong 2002 [33] | Case-control | 64(34/30) | 30/4 | 29.8 | ARA | Peripheral blood: PBMC | Healthy volunteers, mean age was 25.6, gender ratio was 26/4 |

| Xu 2003 [34] | Case-control | 58(38/20) | 38/0 | 32.2 | ACR | Peripheral blood | Healthy volunteers, mean age was 28.2, gender ratio was 20/0 |

| Zheng 2006 [35] | Case-control | 59(49/10) | 43/6 | 30.85 | ARA | Kidney: tubular cell | Normal kidney biopsies without SLE, but accompanied by renal cell carcinoma |

| Bollain 2009 [36] | Case-control | 34(17/17) | 14/3 | 25.9 | ACR | kidney | Normal kidney biopsies without renal pathology |

F Female, M Male, SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus, ARA American Rheumatism Association, ACR American College of Rheumatology, NG Not given

Table 2.

Study assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

| Study | Patient selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total stars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belmont 1997 [32] | 4* | 1* | 2* | 7* |

| Kuhn 1998 [22] | 3* | 1* | 1* | 5* |

| Gong 2002 [33] | 4* | 1* | 1* | 6* |

| Xu 2003 [34] | 3* | 1* | 2* | 6* |

| Zheng 2006 [35] | 4* | 1* | 1* | 6* |

| Bollain 2009 [36] | 4* | 1* | 2* | 7* |

* indicates item achieves 1piont in Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

Expression of iNOS

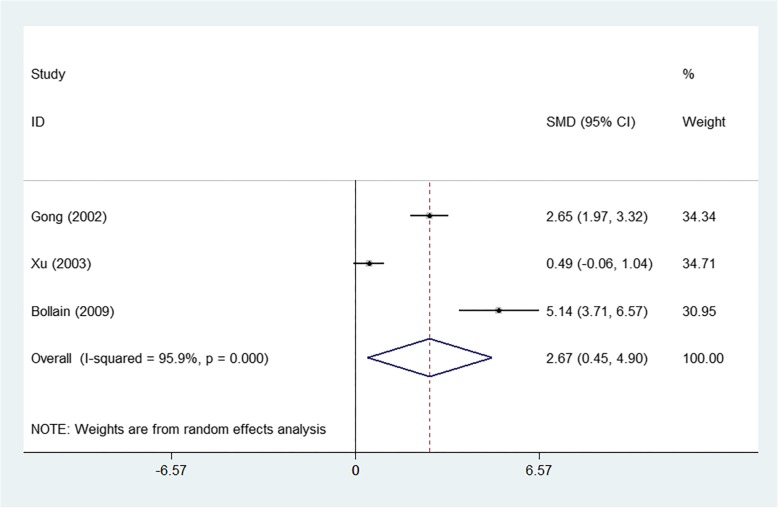

The meta-analysis showed that SLE patients had higher expression of iNOS at mRNA level than the controls (SMD = 2.671, 95%CI = 0.446–4.897, z = 2.35, p = 0.019) (Fig. 2 and Additional file 5: Figure S5A). And a similar tendency was observed at the protein level, staining score of iNOS (SMD = 3.602, 95%CI = 1.144–6.059, z = 2.87, p = 0.004) (Fig. 3 and Additional file 5: Figure S5B). Meanwhile, positive rate of iNOS (OR = 9.515, 95%CI = 1.915–47.281, z = 2.76, p = 0.006) (Fig. 4 and Additional file 5: Figure S5C) were significantly higher in SLE group compared with control group.

Fig. 2.

Forest-plot representing the expression of iNOS at mRNA level between SLE patients and controls

Fig. 3.

Forest-plot representing the expression of iNOS at protein level (staining score of iNOS) between SLE patients and controls

Fig. 4.

Forest-plot representing the positive rate of iNOS between SLE patients and controls

Serum nitrite level

Serum NO is rapidly oxidized to nitrite by iNOS. Nitrite was measured as surrogate markers of NO. So, it always represents the level of NO. We did not observe significant differences in serum nitrite level between SLE cases and control subjects (SMD = 2.203, 95%CI = -0.386–4.793, z = 1.64, p = 0.095) (Fig. 5 and Additional file 5: Figure S5D).

Fig. 5.

Forest-plot representing the serum nitrite elevation between SLE patients and controls

Assessment of publication bias

Because of the limits of funnel plotting, Egger’s test was performed to test publication bias. Except for iNOS expression at protein level (p = 0.006) there was no publication bias according to Egger’s test (Table 3). iNOS expression at mRNA level yieled an Egger’s test score of p = 0.326, Similar results were found in positive rate of iNOS (p = 0.337). However, it’s a failure to get the publication bias of serum nitrite because of insufficient studies.

Table 3.

Egger’s test results of this meta-analysis

| Publication bias | Studies(n) | Egger’s test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P value | 95% CI | ||

| iNOS mRNA level | 3 | 0.326 | −64.87792, 85.96822 |

| iNOS protein level | 3 | 0.006 | 9.40983, 11.97152 |

| Positive rate of iNOS | 4 | 0.337 | −177.3446, 322.8514 |

Heterogeneity and sensitivity analysis

The results in this study showed significant level of substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 90%, p < 0.0001), except for the positive rate of iNOS (I2 = 54.6%, p = 0.085). Subgroup analysis on public year, sample size, study quality and assessing tissue type was tried, although the number of included studies was small. However, for the limitation of the insufficient studies we did not find the source of heterogeneity (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Sensitivity analysis by excluding individual studies revealed that the results were not modified when compared to the overall effect (Additional file 3: Figure S3). Then the sensitivity analysis with fixed effects model demonstrated that the results were not changed (Additional file 4: Figure S4). Overall, sensitivity analysis revealed that the results produced in this meta-analysis were robust.

Discussion

More and more experimental data suggest that iNOS was an essential pathogenic mediator in SLE. The general idea of this progress is that iNOS rises in SLE and the inhibitor of iNOS can lessen disease severity [24, 25]. However, several studies indirectly showed an opposite opinion that iNOS might relieve SLE symptoms [30, 31]. Our meta-analysis showed that the expression of iNOS is higher in SLE patients than control subjects, both at mRNA level and protein level (including the staining score and positive rate of iNOS expression). This is consistent with previous findings [5, 8, 37]. These data supported the hypothesis that over-expression of iNOS may lead to organ damage and alter immune response with SLE. Although the present analysis showed a positive correlation between iNOS and SLE, the source of iNOS is unknown. Recently, increasing evidence has suggested that proportions of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous myeloid precursor, enhanced in SLE patients and mice [38, 39]. Although a variety of potential mechanisms is involved in the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs, the main suppressive activity of MDSCs is associated with the secretion of arginase-1 and iNOS [30, 40]. So, we speculate iNOS and MDSCs has some relationship in SLE. Perhaps MDSCs is the source of iNOS.

Previous studies show iNOS and excessive production of NO have been detected in SLE [12, 21]. NO can convert to nitrite, nitrate, nitrotyrosine (NT) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which are stable. So, nitrite is evaluated to represent NO level in general. Our analysis showed no significant difference in serum nitrite elevation between SLE group and control group. This goes against the previous studies [5, 12, 21]. It may be due to the small sample of this index. Besides, dual effect of NO may contribute to this result. Low levels of NO plays a role of defending factor against invading pathogens. High levels of NO plays a role of proinflammatory factor promoting immune disorders. However, there is no definite boundary of the concentration. Meanwhile, SLE patients are under the environment with inflammation for a long time, and if they have formed a tolerance of NO is not clear. Moreover, in arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) models, NOS inhibition during inactive stage worsened clinical symptoms, while during active stage ameliorated clinical symptoms [41, 42]. The individuals included in the selected studies were accorded with ACR or ARA criteria of SLE diagnosis, but the included studies did not describe if they were during an active or inactive stage. All of this may infect the results.

iNOS is an inducible synthase and can catalyze arginase producing excessive NO. NO is one of the most important RNS. There is a wealth of evidence to implicate the increased RNS were associated with autoantibody increasing, suggesting a potential role of RNS in autoimmune disease, including SLE [43–45]. However, the exact mechanisms are not clear. According to the present information, we known NO has various proinflammatory actions that lead to tissue damage and chronic inflammation because of involving in several cell functions [46]. For example, NO can lead to gene mutation via the cytosine deamination, it also can lead to oxidative phosphorylation decreasing due to the mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster enzyme inhibition [42]. ONOO−, one of the stable products of NO, is more reactive and more toxic than NO and permeates membranes to attack cellular compartments and nucleic acid in cells leading cell injury. It can induce apoptosis via cytochrome-C-mediated caspase activation. Circulating apoptotic cells can lead to accumulation of autoantibodies in SLE [47]. In addition, ONOO− also may play a role in activating signaling pathways such as activator protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB). These studies together inspired the hypothesis that iNOS correlated with the progression of SLE via RNS. Previous studies have shown that JAK/STAT signaling pathway involves in the suppression of T cells by inducing iNOS [48]. Recently, some new views have been put forward. In macrophage, the induction of iNOS was dependent on PI3K/ AKT signaling pathways [49]. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) therapy lessened SLE mice by producing iNOS to inhibit T follicular helper (Tfh) cells expansion [27]. The study in murine animals shows L-NMMA, an iNOS inhibitor, can break the balance of immune tolerance in SLE via regulatory B (Breg) cells [50]. These findings suggest that iNOS can be considered as a novel targeting therapeutic strategy in SLE patients. Previous studies have shown that inhibiting iNOS activity in MRL/lpr mice can restore renal catalase activity, and inhibit cellular apoptosis and proliferation in the glomerulus [51, 52]. Also, heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which can reduce the expression of iNOS, was an effective therapy for glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice [53–55]. Although the mortality of SLE is greatly reduced, patients still suffer from disease flares due to the complex mechanisms. In line with this, immunosuppressant medications are mainstay of treatment. Several of the medications drive benefits from their capacity to inhibit iNOS. In some tissues, glucocorticoids and cyclosporine inhibit the induction of iNOS. Mycophenolate Mofetil can reduce the generation of NO through inhibiting the activity of GTP-dependent iNOS. These medicines showed effectiveness toward SLE. However, they can only prolong the inactive period of SLE instead of recovery. Despite the availability of new treatments directed against causative molecular targets, most clinical trials have been disappointing. Therefore, iNOS has important implications regarding the development of pharmacologic therapies for SLE.

The present study has some limits cannot be ignored. First, because of the limits of incorporated studies, the limited sample size may decrease the statistical power of this analysis. Second, all the included studies were case-control and single-center clinical studies, so they lacked randomness. Third, in the included criteria, we did not set a rigorous definition to the tissue which used to measure iNOS expression. For iNOS expression is positive in multiple cell types, such as macrophages, endothelial cells, peripheral blood monocytes, tubular cells [56, 57]. Moreover, there were no unified standards according to previous studies. This might be a confounding factor. Fourth, there was significant heterogeneity in our meta-analysis. The source of heterogeneity was unidentifiable despite attempting different sensitivity analyses and analyzing different subgroups. The insufficient number of included studies is the major limiting factor. Other factors, such as methods of measurement, sample size, public year, environmental factors, should also be taken into account. Finally, the result of iNOS expression at protein level has a publication bias, the source of it may come from 3 aspects: included studies were non-randomized controlled trails, the sample size was small, the high heterogeneity. Above all, the results should be interpreted with caution. More prospective randomized studies are needed to certify our results.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis showed SLE patients have a higher iNOS expression at both mRNA level and protein level. On the contrary, there is no difference of serum nitrite level between SLE patients and control subjects. These data suggested that the over-expression of iNOS may relate to the pathological process of SLE. However, the source of iNOS is unclear. Although reactive nitrogen species are considered to be the most important and widely studied way to join in SLE, other factors are discovered gradually, such as Tfh [37], Breg cells [38], as well as some signaling pathways (PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT signaling pathways). Therefore, therapeutic strategy targeting iNOS is a promising therapy for SLE patients.

Methods

Search strategy

The online database of PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Wanfang database were searched for observational studies assessing the association of iNOS and SLE, Using the following key words or MeSH terms: “systemic lupus erythematosus” or “SLE” or “lupus”, combined with “inducible nitric oxide synthase” or “inducible NOS” or “iNOS” or “NOS2”. The final systematic search was conducted on June 2018 with no language restriction. References in the retrieved articles were explored for potentially relevant studies.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if they met the following criteria:

Case-control, cross-sectional or cohort studies;

SLE patients were diagnosed based on the diagnostic criteria of American Rheumatism Association (ARA) or American College of Rheumatism (ACR);

Control subjects are people without the history of any autoimmune disorders including SLE;

Results contained evaluation of iNOS.

Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded if they met the following criteria:

animal-model studies, case reports, review articles, letters, comments, editorials;

Participants were pregnancy;

Participants who were suffering diabetes mellitus, malignant tumor, chronic kidney diseases and other diseases can lead to cachexia;

Studies with incomplete data.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by 2 independent authors. Ambiguities were resolved by discussion among all authors. The third reviewer (Huanfa Yi) was the final person to solve the issue. Data from each study were extracted including, but not limited to: name of author, year of publication, study design, gender of participants, numbers of participants, age of participants, criteria of SLE diagnosis, tissue type used to evaluate iNOS.

Quality assessment

As the studies involved in this meta-analysis are all case-control ones, quality of the included studies was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). In this scale, “patient selection”, “comparability of study groups” and “exposure” consist of a particular “star system” to evaluate included studies [58]. The lowest score was 0 star, and the highest score was 9 stars. Studies with a score of ≥5 stars were defined as having a high quality. On the other hand, studies with a score of <5 stars were defined as having a low quality [59].

Statistical analysis

Odd ratio (OR) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for dichotomous variables. Standardized mean difference (SMD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for continuous variables. The Q statistic test and the I2 test were used to assess heterogeneity [60]. If I2 >50% (I2 test) and p <0.1 (Q test) were applied as significant heterogeneity of outcomes, we use random effect model to pool the data. Otherwise, the fixed effect model was used. The subgroup analysis was conducted to detect the sources of heterogeneity. The articles involved in our meta-analysis were less than 10, funnel plots cannot be used to detect publication bias [61]. Due to the limits of funnel plotting, publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s test, where, p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. We evaluated the strength of the pooled estimates by performing a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis and changing the analysis method from random-effects model to fixed-effects model to measure the impacts that each study applies on the overall pooled estimate. All statistical analysis involved in this meta-analysis was carried out with the use of the STATA 12.0. Statistically significant value was less or equal to 0.05 (p ≤ 0.05).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Subgroup analysis of the expression of iNOS at mRNA level from A) Public year (1: ≤2002, 2: > 2002); B) Study quality (1: ≤6*, 2: > 6*); C) Sample size (1: > 50, 2:≤50); D) Tissue (1: skin, 2: blood, 3: kidney).

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Subgroup analysis of staining score of iNOS from A) Public year (1: ≤2002, 2: > 2002); B) Study quality (1: ≤6*, 2: > 6*); C) Sample size (1: > 50, 2:≤50); D) Tissue (1: skin, 2: blood, 3: kidney).

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Sensitivity analysis by excluding individual studies of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. Sensitivity analysis with fixed effects model of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Additional file 5: Figure S5. The statistical values (z value and p value) of combined effect variables of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- ACR

American College of Rheumatism

- AP-1

Activator protein-1

- ARA

American Rheumatism Association

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- eNOS

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- HO-1

heme-oxygenase-1

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- NT

nitrotyrosine

- ONOO−

Peroxynitrite

- RNS

Reactive nitrogen species

- S1P

Sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SLE

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Authors’ contributions

LP and SY designed the work, acquired data and played an important role in interpreting the results. LP drafted the manuscript. JW and MX contributed to the data extraction. HY contributed to the conception of the study. SW performed manuscript review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81671592 and 81501279). The funding bodies have no roles in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shaofeng Wang and Huanfa Yi contributed equally to this work.

Lu Pan and Sirui Yang contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Lu Pan, Email: panlu0330@jlu.edu.cn.

Sirui Yang, Email: sryang@jlu.edu.cn.

Jinghua Wang, Email: 14745099@qq.com.

Meng Xu, Email: xusmilemen@163.com.

Shaofeng Wang, Email: shaofengwang@jlu.edu.cn.

Huanfa Yi, Email: yihuanfa@jlu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12865-020-0335-7.

References

- 1.Durcan L, Petri M. Why targeted therapies are necessary for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2016;25(10):1070–1079. doi: 10.1177/0961203316652489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Autoimmunity and oxidatively modified autoantigens. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(7):567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurevitz SL, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of the disease and treatment options. Consult Pharm. 2013;28(2):110–121. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsokos GC, et al. New insights into the immunopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(12):716–730. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shobaili HA, Rasheed Z. Physicochemical and immunological studies on mitochondrial DNA modified by peroxynitrite: implications of neo-epitopes of mitochondrial DNA in the etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013;22(10):1024–1037. doi: 10.1177/0961203313498803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths HR. Is the generation of neo-antigenic determinants by free radicals central to the development of autoimmune rheumatoid disease? Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7(7):544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moncada S, Higgs A. The L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(27):2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson SB, et al. The role of nitric oxide in tissue destruction. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2001;15(5):831–845. doi: 10.1053/berh.2001.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clancy RM, Abramson SB. Nitric oxide: a novel mediator of inflammation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;210(2):93–101. doi: 10.3181/00379727-210-43927AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez-Gay MA, et al. Inducible but not endothelial nitric oxide synthase polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis in Northwest Spain. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(9):1182–1185. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souza JM, et al. Factors determining the selectivity of protein tyrosine nitration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;371(2):169–178. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilkeson G, et al. Correlation of serum measures of nitric oxide production with lupus disease activity. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(2):318–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan PE, Sturgess AD, Davies MJ. Evidence for chronically elevated serum protein oxidation in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Free Radic Res. 2009;43(2):117–127. doi: 10.1080/10715760802623896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah D, et al. Oxidative stress in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship to Th1 cytokine and disease activity. Immunol Lett. 2010;129(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzon E, et al. Role of tight junction derangement in the endothelial dysfunction elicited by exogenous and endogenous peroxynitrite and poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase. Shock. 2002;18(5):434–439. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negre-Salvayre A, et al. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(1):6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad R, Ahsan H. Role of peroxynitrite-modified biomolecules in the etiopathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Med. 2014;14(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10238-012-0222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frostegard J, et al. Lipid peroxidation is enhanced in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and is associated with arterial and renal disease manifestations. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(1):192–200. doi: 10.1002/art.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habib S, Moinuddin, Ali R. Peroxynitrite-modified DNA: a better antigen for systemic lupus erythematosus anti-DNA autoantibodies. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2006;43(Pt 2):65–70. doi: 10.1042/BA20050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan F, Siddiqui AA, Ali R. Measurement and significance of 3-nitrotyrosine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64(5):507–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oates JC, et al. Prospective measure of serum 3-nitrotyrosine levels in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlation with disease activity. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111(6):611–621. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.99110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn A, et al. Aberrant timing in epidermal expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase after UV irradiation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(1):149–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinberg JB, Granger DL, Pisetsky DS, et al. The role of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of spontaneous murine autoimmune disease: increased nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthase expression in MRL-lpr/lpr mice, and reduction of spontaneous glomerulonephri- tis and arthritis by orally administered N G -monomethyl- L -arginine. J Exp Med. 1994;179:651–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. Estrogen regulation of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in immune cells: implications for immunity, autoimmune diseases, and apoptosis. Nitric Oxide. 2006;15(3):177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra N, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors modulate renal disease in the MRL-lpr/lpr mouse. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(4):539–552. doi: 10.1172/JCI16153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang CW, et al. Aminoguanidine reduces glomerular inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1) mRNA expression and diminishes glomerulosclerosis in NZB/W F1 mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113(2):258–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit T follicular helper cell expansion through the activation of iNOS in lupus-prone B6.MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. Cell Transplant. 2017;26(6):1031–1042. doi: 10.3727/096368917X694660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueno H, Banchereau J, Vinuesa CG. Pathophysiology of T follicular helper cells in humans and mice. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(2):142–152. doi: 10.1038/ni.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crotty S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity. 2014;41(4):529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al Gadban MM, et al. Lack of nitric oxide synthases increases lipoprotein immune complex deposition in the aorta and elevates plasma sphingolipid levels in lupus. Cell Immunol. 2012;276(1–2):42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belmont HM, et al. Increased nitric oxide production accompanied by the up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelium from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(10):1810–1816. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juanqin G, et al. iNOS expression at mRNA level in peripheral blood mononucler cell in SLE. J Clin Dermatol. 2002;31(1):17-19.

- 34.Xu LT, Wang MM. The detective of NO and its production in SLE. Jingsu Med J. 2003;29(12):923–924. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng L, Sinniah R, Hsu SI. Renal cell apoptosis and proliferation may be linked to nuclear factor-kappaB activation and expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in patients with lupus nephritis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(6):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bollain-y-Goytia JJ, et al. Widespread expression of inducible NOS and citrulline in lupus nephritis tissues. Inflamm Res. 2009;58(2):61–66. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-7215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang JS, et al. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and apoptosis in human lupus nephritis. Nephron. 1997;77(4):404–411. doi: 10.1159/000190316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji J, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells contribute to systemic lupus erythaematosus by regulating differentiation of Th17 cells and Tregs. Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130(16):1453–1467. doi: 10.1042/CS20160311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vlachou K, et al. Elimination of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in lupus-prone mice linked to reactive oxygen species-dependent extracellular trap formation. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):449–461. doi: 10.1002/art.39441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien NC, et al. Nitric oxide plays a critical role in the recovery of Lewis rats from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and the maintenance of resistance to reinduction. J Immunol. 1999;163(12):6841–6847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberg JB. Nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthase type 2 expression by human mononuclear phagocytes: a review. Mol Med. 1998;4(9):557–591. doi: 10.1007/BF03401758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang G, et al. Lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde-protein adducts contribute to trichloroethene-mediated autoimmunity via activation of CD4+ T cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44(7):1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G, et al. Markers of oxidative and nitrosative stress in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlation with disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2064–2072. doi: 10.1002/art.27442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang G, et al. Protein adducts of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal contribute to trichloroethene-mediated autoimmunity via activating Th17 cells: dose- and time-response studies in female MRL+/+ mice. Toxicology. 2012;292(2–3):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levesque MC, Weinberg JB. The dichotomous role of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of accelerated atherosclerosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4(7):777–786. doi: 10.2174/1566524043359872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oates JC, Gilkeson GS. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis in spleen lymphocytes from MRL/lpr mice. J Investig Med. 2004;52(1):62–71. doi: 10.1136/jim-52-01-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang D, et al. A CD8 T cell/indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase axis is required for mesenchymal stem cell suppression of human systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(8):2234–2245. doi: 10.1002/art.38674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cianciulli A, et al. PI3k/Akt signalling pathway plays a crucial role in the anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in LPS-activated microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;36:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park MJ, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells induce the expansion of regulatory B cells and ameliorate autoimmunity in the Sanroque mouse model of systemic lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(11):2717–2727. doi: 10.1002/art.39767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keng T, et al. Peroxynitrite formation and decreased catalase activity in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Mol Med. 2000;6(9):779–792. doi: 10.1007/BF03402193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reilly CM, et al. Modulation of renal disease in MRL/lpr mice by pharmacologic inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Kidney Int. 2002;61(3):839–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takeda Y, et al. Chemical induction of HO-1 suppresses lupus nephritis by reducing local iNOS expression and synthesis of anti-dsDNA antibody. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138(2):237–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lui SL, et al. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil on severity of nephritis and nitric oxide production in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Lupus. 2002;11(7):411–418. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu214oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu CC, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil reduces renal cortical inducible nitric oxide synthase mRNA expression and diminishes glomerulosclerosis in MRL/lpr mice. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;138(1):69–77. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.115647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bolli R. Cardioprotective function of inducible nitric oxide synthase and role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia and preconditioning: an overview of a decade of research. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(11):1897–1918. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dusting GJ, et al. Nitric oxide in atherosclerosis: vascular protector or villain? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 1998;25:S34–S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wells GS, S.B., O’Connell D, et al. The Newcatle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2013. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

- 59.Mak A, Liu Y, Ho RC. Endothelium-dependent but not endothelium-independent flow-mediated dilation is significantly reduced in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without vascular events: a metaanalysis and metaregression. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1296–1303. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Higgins JP, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higgins JPT, G. S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/. Accessed July 2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Subgroup analysis of the expression of iNOS at mRNA level from A) Public year (1: ≤2002, 2: > 2002); B) Study quality (1: ≤6*, 2: > 6*); C) Sample size (1: > 50, 2:≤50); D) Tissue (1: skin, 2: blood, 3: kidney).

Additional file 2: Figure S2. Subgroup analysis of staining score of iNOS from A) Public year (1: ≤2002, 2: > 2002); B) Study quality (1: ≤6*, 2: > 6*); C) Sample size (1: > 50, 2:≤50); D) Tissue (1: skin, 2: blood, 3: kidney).

Additional file 3: Figure S3. Sensitivity analysis by excluding individual studies of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Additional file 4: Figure S4. Sensitivity analysis with fixed effects model of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Additional file 5: Figure S5. The statistical values (z value and p value) of combined effect variables of different results: A) expression of iNOS at mRNA level; B) staining score of iNOS; C) positive rate of iNOS; D) serum nitrite level.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.