Abstract

Background:

Neglect is the most common allegation in Child Protective Services (CPS) investigations. Researchers and media have questioned whether and how CPS-investigated neglect differs from poverty. Prior studies are limited by self-reported or cross-sectional measures, small samples, and short observation periods.

Objective:

(1) To estimate the “added harm” of CPS-investigated neglect, net of poverty exposure (depth and duration), on high school completion, employment and earnings, incarceration, and teen parenthood; (2) To assess whether abuse is a stronger risk factor for adverse outcomes than neglect.

Participants and Setting:

29,154 individuals born in 1993–1996 from Milwaukee County, WI, who either received food assistance or were reported to CPS before age 16.

Method:

Using logistic regression with a rich set of social and demographic controls, we compared individuals with CPS-investigated neglect, abuse, or both abuse and neglect in early childhood or adolescence to those who experienced poverty but not CPS involvement. We calculated cumulative measures of poverty duration and poverty depth between ages 0 and 16 for the full sample using public benefit records.

Results:

Outcomes among children with alleged or confirmed neglect were statistically significantly worse in all domains than impoverished children without maltreatment allegations, and similar to children with alleged or confirmed abuse. Effect sizes varied by outcome.

Conclusions:

Overall, this study suggests that CPS allegations of neglect are distinct from poverty and an important risk factor for adverse outcomes in adulthood.

Keywords: child neglect, child abuse, poverty, early adulthood, child protective services

In the U.S. Child Protective Services (CPS) system, the overwhelming majority of substantiated cases – over 70% in 2016—involve some form of neglect (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017). Neglect is generally defined as a failure to meet the basic needs of a child, typically encompassing food, shelter, clothing, medical care, and supervision (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014). Because legal definitions of neglect include deprivation of material needs, some have questioned whether and how neglect is distinguishable from economic hardship or poverty and whether labeling parents as perpetrators of neglect essentially punishes poverty (Pelton, 2016; Roberts, 2014). In addition, there has been a growth in state and local differential response programs, which redirect “low-risk” cases—often a subset of neglect referrals—to a non-investigative, often voluntary system response that eschews victim/perpetrator labels (Hughes, Rycus, Saunders-Adams, Hughes, & Hughes, 2013). However, lack of clear measures of the contexts of neglect in CPS records make it difficult to ascertain whether CPS reports of neglect are largely “low-risk” and primarily reflect material deprivation due to poverty. Moroever, the evidence base that seeks to differentiate the effects of neglect from those of poverty and abuse is limited by considerable data and measurement issues.

Current estimates suggest that 37% of all U.S. children (and more than half of all U.S. Black children) experience a CPS investigation before their 18th birthday (Kim, Wildeman, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2017). An estimated 85% of families investigated by CPS are below 200% of the federal poverty line (Dolan, Smith, Casanueva, & Ringeisen, 2011), suggesting a broad reach of CPS into the lives of poor families. By comparing long-term outcomes of children reported to CPS for neglect with those who experience varying degrees and durations of poverty, we can better understand whether the allegations of neglect investigated by CPS are distinct from poverty in their effects on children’s later functioning. By comparing children with neglect allegations and children with abuse allegations, we further assess whether abuse is associated with worse social, educational, and economic and behavioral outcomes than neglect. Specifically, we address two research questions: (1) Do the social, educational, and economic outcomes of children exposed to alleged neglect differ from outcomes of children exposed to alleged abuse or to poverty alone, net of other sociodemographic confounds?; and (2) How do the estimated effects of child neglect and abuse compare to the estimated effects of poverty?

Background

Poverty is correlated with neglect (Berger & Waldfogel, 2011; Sedlak et al., 2010; Slack, Holl, McDaniel, Yoo, & Bolger, 2004), and a small body of evidence indicates causal effects of income on maltreatment and neglect specifically (Berger, Font, Slack, & Waldfogel, 2017; Cancian, Yang, & Slack, 2013; Fein & Lee, 2003). Whether poverty contributes to neglect is not widely disputed; what remains contentious is whether what is often reported or labeled as neglect simply is poverty. Indeed, one need not look far to find articles in mainstream media outlets written by or quoting academic scholars asserting that the system investigates or removes children on the basis of poverty (Chill, 2018; Dewan, 2018; Wexler, 2019). State policy and local practices generally instruct CPS caseworkers not to make a finding of neglect in situations that arose for reasons of poverty (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014), irrespective of whether the child was harmed or likely to be harmed in the future. Yet, the extent to which CPS caseworkers are able to distinguish between poverty as a contributing factor versus poverty as the sole factor in neglect is questionable (Eamon & Kopels, 2004).

Defining Neglect

A basic definition of neglect is the failure of a parent or caregiver to meet a child’s basic needs such that a child’s health or safety is threatened (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2014). States’ civil statutes commonly delineate those needs to include food, clothing, shelter, medical care, supervision, and protection. However, it is rarely possible to parse all of the forms of neglect that could be occurring in an environment based on the documentation practices of most CPS agencies, where the details are contained in narrative form and the sub-categories of neglect, if used, are broad. Thus, the vast majority of research on neglect uses a singular construct, though some studies, typically those relying on parent-reported neglect, have differentiated physical neglect (lack of food, shelter, medical care, or clothing) from all other forms of neglect (Berger et al., 2017; Font & Berger, 2015; Yang & Maguire-Jack, 2016).

Non-physical forms of neglect are commonly termed general neglect or supervision neglect, and often involve situations where children are left alone or left in the care of an unsafe or inappropriate person, as well as children’s exposure to parental substance abuse, domestic violence, or criminality. These forms of neglect often involve role-modeling of antisocial behavior by parents (e.g., intoxication, violence toward others, criminal acts). Given that parents are the predominant unit of socialization for children, children may internalize and practice the values expressed in their parents’ behaviors. Though current national measures (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017) are not considered reliable, smaller studies have estimated that parental substance abuse was a contributing factor in at least one-third, and perhaps as many as 80%, of CPS cases (Murphy et al., 1991; Semidei, Radel, & Nolan, 2001; Young, Boles, & Otero, 2007). In addition to adverse effects of in-utero drug and alcohol exposure, substance abuse may compromise parental competence in numerous ways. Intoxicated parents are less aware of or attentive to their children’s needs; they may behave more erratically or aggressively; and, when dependent on substances, parents may be focused on the acquisition of drugs or alcohol rather than caregiving responsibilities (Mayes & Truman, 2002). Although substance abuse is not constrained to those of lower socioeconomic status, substance abuse can affect financial stability by interfering with employment and directly consuming resources that could be spent on housing, food, and other basic needs. Similarly, exposure to domestic violence is believed to negatively affect children not only due to the impact of witnessing harm to others, but also because the non-offending parent’s capacity to connect with, discipline, and attend to the needs of their children is compromised (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, 2008). In cases related to lack of supervision, which may or may not involve substance abuse, children are deprived of cognitive stimulation and emotional connection, and may have greater opportunity for delinquent behavior.

Evidence on Poverty, Neglect, and Development

The causal impacts of childhood poverty are most clearly demonstrated for children’s academic and cognitive outcomes (Duncan, Magnuson, & Votruba-Drzal, 2017), and are at least partially explained by differences in cognitive enrichment (Reeves & Howard, 2013). Cognitive enrichment can take a variety of forms—reading to children, taking them to museums or other places that facilitate learning, and regular age-appropriate interaction and communication. It can also be provided through multiple sources – parents, extended family, day care providers, or school personnel. Although poverty may limit the quality of day care providers and schools available, parents in poverty provide varying degrees of other forms of stimulation (Sperry, Sperry, & Miller, 2019). Because neglect often manifests in poor supervision and lack of attention to children’s well-being, parents who are neglectful may provide the least cognitive enrichment. Hence, neglected children would be expected to exhibit, on average, worse academic outcomes than their non-neglected low-income peers.

The same factors may be relevant for understanding differences between poor non-neglected and neglected children in social-behavioral outcomes. The lack of supervision and consistent expectations among neglected children may leave them ill-equipped to follow the rules and structure of other environments, including school and work, whereas exposure to inappropriate caregiver behavior (aggression, drug use, unreliability) provides behavioral role models that are not conducive to adaptive social functioning. Children with impoverished but non-neglectful parents may have higher exposure to inappropriate role models due to the concentration of poor families in disorganized, high-crime, neighborhoods (Voisin, 2007); they may also have less consistently structured environments due to more scheduling instability in low-wage jobs. If CPS reports of child neglect primarily reflect structural constraints faced by poor families, then minimal differences in early adulthood outcomes would be expected between children with neglect allegations and children from poor families without such allegations. In contrast, if impoverished non-neglectful parents are better able to control their children’s environments and provide consistent nurturing than parents suspected of neglect, then their children would be expected to exhibit comparatively better social-behavioral outcomes than their neglected counterparts.

However, income poverty is not sufficient for understanding youth outcomes; rather, it is when poverty leads to material hardship or deprivation that parenting behavior and child well-being are most impacted (Gershoff, Aber, Raver, & Lennon, 2007). Thus, it may be that families reported for neglect are simply the most severely and chronically economically disadvantaged, but that the primary issue remains economic in nature. Regardless, economic deprivation affects children in part because economically-distressed parents are less attentive, more harsh, and have more intrafamilial conflict (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994; Newland, Crnic, Cox, & Mills-Koonce, 2013). It is possible that the parents who have the least successful coping mechanisms are most likely to maltreat under conditions of economic stress. Comparing children with CPS neglect allegations with children exposed to varying levels of poverty severity and duration provides insight into whether alleged neglect is distinctively harmful.

Notably, neglect can also arise independently of poverty, but there is limited understanding about the context in which this occurs. It is possible that neglect manifests differently—and has different effects—in non-poor families. Parents who have the resources to meet their child’s basic needs but are unwilling to do so may have a more negative impact, at least psychologically, on their children than parents who are unable due to financial problems. Additionally, poverty may exacerbate the negative impacts of neglect. Neglected but wealthier children may receive better educational supports due to higher quality schools that compensate for inadequate stimulation and support at home. Additionally, the risks of a lack of supervision may be greater in poor families. Given the correlation between individual and neighborhood poverty, and between neighborhood poverty and crime (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997), neglected youth living in poverty may have greater exposure to deviant peers that compound (or are not offset by) parental influences. Thus, neglect may increase the risk of adverse academic and social-behavioral outcomes overall, but especially for youth in poverty.

Limitations of Prior Studies

Prior studies suggest that poor families are more likely to perpetrate abuse and neglect (Sedlak et al., 2010) and reach CPS at higher rates because they face greater risks (Jonson-Reid, Drake, & Kohl, 2009). Yet, studies examining the effects of neglect typically control for or match respondents on current parent-report income (Chen, Propp, & Corvo, 2011; English et al., 2005; Manly, Lynch, Oshri, Herzog, & Wortel, 2013; Whitaker, Phillips, Orzol, & Burdette, 2007). Individuals often underreport total income (Davern, Rodin, Beebe, & Call, 2005)—especially income from benefit programs (Meyer & Mittag, 2015)—or refuse to disclose income (Epstein, 2006). Moreover, households may transition in and out of poverty, and a snapshot of income does not account for the unique impact of persistent childhood poverty (McLeod & Shanahan, 1993). Absent historical data on families’ income, effects of neglect will be overstated if chronic poverty is more common among neglectful families than non-neglectful families. Studies also often combine all forms of child maltreatment into one variable (Lau et al., 2005), which can be problematic if individual types or combinations of maltreatment have differential etiologies or sequalae. Similarly, research focusing on a single type of maltreatment will likely overstate its effects, due to the high rate of co-occurance of multiple maltreatment types (Turner, Vanderminden, Finkelhor, & Hamby, 2019; Vachon, Krueger, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2015).

Current Study

The current study leverages administrative data to identify the associations of poverty and neglect with a host of young adult outcomes. By measuring neglect and poverty longitudinally, we construct a more relevant comparison group for neglected children and thereby improve identification of neglect effects. To address the co-occurrence of multiple forms of maltreatment, and to investigate whether abuse is more harmful than neglect, we compare four groups of children: those exposed to poverty but not maltreatment, those exposed to neglect but not abuse, those exposed to physical or sexual abuse but not neglect, and those exposed to a combination of abuse and neglect. We further consider whether the associations of abuse and neglect with young adult outcomes vary by duration or depth of poverty exposure during childhood. Lastly, we acknowledge that CPS involvement can itself impact children, net of the effects of maltreatment. The effects of CPS involvement, though estimated to be largely null (Afifi, McTavish, Turner, MacMillan, & Wathen, 2018; White, Hindley, & Jones, 2015) could be positive or negative, and the impacts of CPS involvement are confounded by the severity of maltreatment, given that more severe maltreatment is more likely to result in intervention. Thus, we also conduct subsample analyses that exclude children who received a CPS intervention, in order to ascertain whether children with ostensibly lower risk CPS cases nevertheless experience more adverse outcomes in young adulthood than children from low-income families.

Method

Data and Sample

This study used the Wisconsin Administrative Data Core, a linked longitudinal administrative dataset housed at the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, combined with records from the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) for the years 2005 to 2016. The Data Core includes individual-level administrative records from state-administered public social welfare program data systems, which have been linked across programs and over time. We specifically used records from the child welfare system (CPS; which includes foster care data), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; formerly food stamps), Unemployment Insurance system (UI; which includes earnings data), Supplemental Security Income program (SSI), cash welfare, Department of Corrections (DOC), and the Milwaukee County Jail. Child welfare records were not completely electronic in all Wisconsin counties until mid-2004. Thus, the analysis focused on children from Milwaukee County, which had electronic child welfare records beginning in January 2000. Children did not need to remain in Milwaukee County as adults to be included in the study – outcome measures were captured statewide.

To ensure that children’s alleged maltreatment was observed from a relatively early age, we included only those born between 1993 and 1996; thus, the sample was largely between the ages of 3 and 7 when CPS records became available (January 2000). Because some of the early adulthood outcomes (teen parenthood and high school completion) can occur before legal adulthood, we focused on poverty and maltreatment occurring prior to age 16. Outcome data for the sample were observed until their 20th birthday. Of those born between 1993 and 1996, youth were included in the sample if they resided in Milwaukee County at some point during childhood, and received SNAP or were the alleged victim on a CPS investigation prior to age 16. There were 39,102 youth identified under this target population. Youth were excluded if they were reported to have died before age 20 (n=164), were known to have moved out of state (n=2,676); their only maltreatment allegations were not defined as abuse or neglect or occurred at or after age 16 (n=1,259); they spent time in out-of-home care for any reason (4,495); or they were missing information on their biological mother (n=1,354). The final sample size was 29,154 individuals. We excluded children who spent time in out-of-home care because it would not be possible to differentiate the effects of their maltreatment exposure from the effects of their out-of-home care experiences. This exclusion may understate effects of maltreatment, as the most severely maltreated children would likely experience out-of-home placement at higher rates.

The CPS portion of the sample (n=9,278) was divided into two groups: those for whom the CPS system provided in-home services or petitioned the family court (n=1,477) and those whose allegations led to no intervention (n=7,801). Because more severe cases are more likely to result in intervention, the effects of intervention confound the effects of maltreatment in severe cases. However, by focusing on suspected maltreatment that was considered insufficiently severe to warrant intervention, we address whether non-severe cases of neglect are distinct from poverty.

Measures

Outcomes.

We focused outcome measurement primarily on the first two years of adulthood, at ages 18 and 19.

Data from the Milwaukee County Jail and all Wisconsin state prisons were used to construct binary indicators of incarceration. Because those who appear in prisons are likely to have committed (or been charged with) more serious offenses than those who appear in jail only, we modeled jail incarceration and prison incarceration separately.

Parenthood by age 20 was based on multiple sources of data to link children to their biological parents, including Medicaid and child support records, as well as other public assistance and child welfare records. The parenthood measure included children born to parents under the age of 18 as well, though a majority of births occur at ages 18 and 19.

High school graduation was a binary indicator drawn from Department of Public Instruction records; it did not include youth who attended private or choice schools, or youth who were home-schooled; thus, models of this outcome were based on a smaller sample of 24,161.

Stable employment was equal to 1 if a youth reported earnings in six or more quarters in the first eight quarters following their 18th birthday (i.e., were employed 75–100% of quarters in their first two years of adulthood).

Earnings were measured as the average earnings per quarter in the first eight quarters after their 18th birthday, adjusted for inflation. Employment and earnings were not available for individuals missing a valid social security number; analysis for those outcomes was based on a slightly reduced sample of 28,701. Together, the six outcome measures captured multiple domains of functioning: educational, economic, and social-behavioral.

Poverty.

To measure poverty, we relied on data from SNAP (food assistance). Although the threshold for SNAP eligibility is slightly above the federal poverty line (130%), its usage among poor families is far higher than for other means-tested programs; thus, it is among the most inclusive measures of poverty that can be gleaned from administrative data. Rate of SNAP participation among eligible persons was approximately 83% in 2015, with highest participation among the families in greatest economic need (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017). To capture childhood poverty, we identified those who were ever enrolled in SNAP prior to age 16.

However, families may enroll in SNAP due to a temporary economic shock or prolonged economic need, and families enrolled in SNAP have different levels of need. If neglect cases are comprised of more chronic or more severe poverty, then those who were ever SNAP recipients would not be an adequate comparison group. Thus, we created measures of duration and depth of poverty. Duration of poverty was equal to the percent of a subject’s childhood months (ages 0–16) in which they received SNAP. Poverty depth was equal to the average percent of the maximum benefit that the subject’s family received, conditional on receiving a benefit. The percent of maximum benefit was equal to the amount received in a month divided by the maximum benefit for their household size permitted under USDA rules, where a higher percentage indicates that the family had less income to contribute to their own food costs. Months in which no benefit was received were not included in the calculation of poverty depth.

Maltreatment.

Maltreatment types that were investigated or confirmed by CPS were used to create four categories: No alleged or confirmed maltreatment (NM), alleged or confirmed neglect only (NO), alleged or confirmed abuse only (AO), and alleged or confirmed abuse and neglect (AN). The main indicator of neglect was based on investigated allegations of neglect by CPS that occurred between year 2000 and the child’s 16th birthday. We used the 16th birthday as a cutoff to avoid measuring outcomes such as teen parenthood and high school dropout that were determined prior the onset of maltreatment. The primary code, “Neglect - general lack of care,” was fairly generic and thus did not provide indications of the underlying circumstances. Abuse allegations included physical, sexual, and emotional abuse allegations. Types of maltreatment were drawn both from the allegations identified in the initial CPS report and from substantiation disposition following the investigation, where applicable. In the main models, we did not differentiate between investigations that were substantiated (confirmed), because it is not clear such distinctions are indicative of the veracity of allegations (Hussey et al., 2005; Kohl, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2009). Rather, investigations were differentiated on the basis of intervention. Because CPS intervenes in a limited number of cases where intervention is perceived as necessary to protect the child, it is likely that these cases involve higher risk or more harmful situations that cases in which intervention was not provided. We excluded children removed from the home because that is an intervention that direct impacts child well-being in ways that are beyond the scope of this study, whereas in-home services are largely focused on the child’s caregivers and effects on child well-being would be indirect (Berger & Font, 2015). Intervention was defined as providing services or case monitoring or involving family court. It was not possible to differentiate effects of intervention from severity of maltreatment – no independent measures of severity or harm were available in the data.

Covariates.

We controlled for several factors that may confound associations of poverty and maltreatment with education, economic, and social outcomes. Youth characteristics controlled in all models were year of birth, sex, race/ethnicity, and receipt of SSI (as a proxy for disability status). Family characteristics were mother’s age at first birth, number of children born to mother, number of fathers to mother’s children, and marital status at child’s birth. We also controlled for subjects’ mothers’ receipt of cash assistance, employment, earnings, and incarceration when the subject was ages 0 to 5.

Analysis

Logistic regression models were used to regress the outcome measures on the maltreatment measure, the poverty measures, and the interactions between maltreatment and poverty. The poverty measures were mean-centered and models include the interaction of poverty duration and depth. To ease interpretation of multi-category interaction terms, We plotted the predicted probabilities of each outcome by maltreatment and poverty duration, with all other variables held constant. Models focused on comparisons between youth from low-income families (i.e., youth who received SNAP benefits) without CPS history and (1) all youth with a CPS investigation, (2) youth with a CPS investigation but no intervention, and (3) youth with a CPS intervention.

Results

Sample Description

Table 1 contains a description of the full sample by group (no allegations of maltreatment [NM], alleged neglect only [NO], alleged abuse only [AO], alleged abuse and neglect [AN]). Youth in the NM and AO groups experienced a shorter duration of poverty (40 and 38% of childhood months) than those in the NO or AN groups (49 and 53% of childhood months). NM youth had a higher estimated depth of poverty while receiving SNAP benefits than the maltreatment groups – NM youth received about 63% of the maximum benefit while on SNAP, versus 58% for NO youth, 60% for AN youth, and 52% for AO youth. Similarly, NO and AN youth were more likely to have mothers who received cash welfare in early childhood (NO youth: 76%, AN youth: 79%) than NM youth (64%) or AO youth (68%), and had mothers who were less frequently employed and had lower earnings. Mothers of NO and AN children were also younger at first birth than mothers of AO and NM children.

Table 1.

Sample Description by Maltreatment Exposure (full sample)

| N | No Alleged Maltreatment (NM) 19,876 |

Alleged neglect Only (NO) 3,060 |

Alleged neglect and abuse (AN) 2,248 |

Alleged abuse only (AO) 3,970 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/Mean | SD | %/Mean | SD | %/Mean | SD | %/Mean | SD | |

| Poverty Measures (SNAP receipt, age 0–16) | ||||||||

| Never | --- | 10.49% | 5.46% | 15.10% | ||||

| Duration (% months received) | 40.10 | 29.23 | 49.18 | 32.46 | 52.82 | 30.00 | 38.47 | 31.38 |

| Depth (mean % max benefit when received) | 62.78 | 18.42 | 57.56 | 26.55 | 59.57 | 22.41 | 51.55 | 27.23 |

| Outcomes through age 20 | ||||||||

| Graduated high school | 77.53% | 63.59% | 59.10% | 72.28% | ||||

| Teen parenthood | 12.85% | 18.10% | 23.49% | 15.99% | ||||

| Milwaukee County Jail | 8.52% | 13.76% | 17.93% | 12.04% | ||||

| State prison | 1.81% | 3.92% | 4.85% | 2.92% | ||||

| Regular employment | 35.54% | 29.58% | 30.65% | 35.47% | ||||

| Average quarterly earnings | $1,036.39 | 1284.24 | $930.18 | 1226.56 | $914.19 | 1200.99 | $1,035.01 | 1243.87 |

| Characteristics of Youth’s Biological Mother | ||||||||

| Age at first birth | 20.18 | 4.36 | 19.24 | 4.07 | 19.28 | 4.02 | 20.15 | 4.41 |

| Number of children | 3.77 | 1.98 | 4.51 | 2.26 | 4.20 | 2.08 | 3.51 | 1.90 |

| Incarcerated at child ages 0–5 | 0.42% | 0.88% | 1.38% | 0.81% | ||||

| Received cash welfare at child ages 0–5 | 63.61% | 76.34% | 79.31% | 67.91% | ||||

| Avg. quarters employed at child ages 0–5 | 1.66 | 1.38 | 1.62 | 1.27 | 1.70 | 1.26 | 2.01 | 1.35 |

| Avg. annual earnings at child ages 0–5 | 7015.34 | 9060.26 | 6232.74 | 9517.43 | 6265.95 | 8477.96 | 9296.42 | 11106.12 |

| Youth Family Status | ||||||||

| Child was a marital birth | 12.49% | 12.78% | 14.99% | 17.23% | ||||

| Child was a nonmarital birth | 66.33% | 71.90% | 75.62% | 67.10% | ||||

| Child’s birth status unknown | 21.18% | 15.33% | 9.39% | 15.67% | ||||

| Paternity not established | 32.79% | 23.86% | 17.17% | 22.14% | ||||

| Paternity established, no support order | 12.50% | 11.67% | 11.03% | 12.29% | ||||

| Support order | 54.71% | 64.48% | 71.80% | 65.57% | ||||

| Youth Demographics | ||||||||

| White non-Hispanic | 14.69% | 18.59% | 22.51% | 22.29% | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 55.25% | 59.71% | 53.20% | 51.01% | ||||

| Hispanic (any race) | 17.89% | 11.44% | 15.61% | 15.39% | ||||

| Other race/unknown race | 12.17% | 10.26% | 8.67% | 11.31% | ||||

| Female | 48.40% | 47.35% | 53.02% | 53.25% | ||||

| Born 1993 | 24.55% | 24.28% | 21.09% | 24.23% | ||||

| Born 1994 | 24.99% | 24.54% | 25.04% | 24.51% | ||||

| Born 1995 | 24.83% | 24.58% | 26.20% | 24.71% | ||||

| Born 1996 | 25.63% | 26.60% | 27.67% | 26.55% | ||||

| Received SSI as child | 7.04% | 12.03% | 18.28% | 11.66% | ||||

Notes: SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. SSI = Supplemental Security Income (means-tested cash assistance program for children or adults with disabilities).

Similarly, there were significant bivariate differences in the outcomes of youth by maltreatment exposure. Youth in the NO and AN groups were less likely to complete high school (64% and 59%) than youth in the AO or NM groups (73% and 78%). NO and AN youth were also more likely to have a child before age 20 (18% and 23%, vs. 16% and 13%). Youth in the AN group were more likely than all other youth to have been in jail (18%) or prison (5%) by age 20; NO youth and AO youth had similar risks of jail (14% vs. 12%) and prison (4% vs. 3%), whereas NM youth had the lowest risk (jail 9%, prison 2%). NO and AN youth were less likely to be stably employed and had lower average quarterly earnings than AO or NM youth.

Regression Results

Is Maltreatment Associated with Young Adult Outcomes, Net of Poverty Exposure?

In our first set of models, we estimated the odds of each outcome as a function of maltreatment, poverty duration, average poverty depth, and sociodemographic controls (coefficients for control variables not shown). In the full sample we found that, compared with NM youth, all youth with maltreatment allegations had lower odds of high school graduation and regular employment, lower average earnings, and higher odds of teen parenthood and jail or prison incarceration. AN youth were less likely to graduate high school and more likely to become teen parents than NO or AO youth. AO youth higher odds of incarceration and NO youth high lower odds of stable employment. There were no statistically significant differences between NO and AO youth in the odds of high school graduation, teen parenthood, or earnings. Both poverty duration and poverty depth were negatively associated high school graduation, and positively associated with teen parenthood and imprisonment. Poverty duration during childhood was associated with slightly higher odds of regular employment and with higher average earnings, whereas poverty depth was associated with lower odds of regular employment and lower earnings. Notably, we cannot account for whether youth were enrolled in postsecondary education, which may reduce employment and earnings. Given lower rates of high school completion, it is likely that maltreated youth would also have lower rates of college enrollment; failure to account for college may downwardly bias estimates of differences in employment and earnings.

The subsample models (Panels B and C) show that youth with CPS allegations that did not lead to any intervention were nevertheless distinct in their outcomes when compared to NM youth – the coefficients are similar to those reported in the full sample models. When focusing only on CPS youth who receive an in-home intervention (Panel C), the size of cofficients differs from the non-intervention group, though not in a consistent direction. Again, more negative outcomes in the intervention group may be attributable to effects of the interventions themselves, but there is no evidence that in-home services negatively impact youth outcomes.

Effect Sizes.

We estimated the predicted probabilities or means (earnings only) of various outcomes across different values of poverty exposure and maltreatment. Predicted values were based on logistic regression models for Panel B that allowed associations between maltreatment and each outcome to be moderated by poverty depth and duration. We do not show these interaction models in table form because of limitations in the interpretability of interaction terms in the context of logistic regression and instead focus on the predicted values. We specifically examined the predicted probability (or mean, for earnings) of each outcome at average, low, and high poverty exposure. Average was defined as the mean sample value for duration and depth (duration = 40% of childhood months or 6.4 years of poverty, depth = average 63% of maximum benefit). Low poverty exposure was −1 standard deviation on both metrics (duration =10% of childhood months or 1.6 years of poverty, depth = average 42% of maximum benefit), and high poverty exposure was +1 standard deviation on both metrics (duration = 70% of childhood months or 11.2 years of poverty, depth = average 84% of maximum benefit). Covariates were held constant at the mean for quantitative measures and at the base value for all categorical control variables except race and sex, which were treated as balanced across groups. We focused on comparisons of those with no known maltreatment (NM) to those with maltreatment allegations that did not result in any CPS intervention to exclude any effects of CPS intervention on risk. Wald tests were used to determine the statistical significance of group differences.

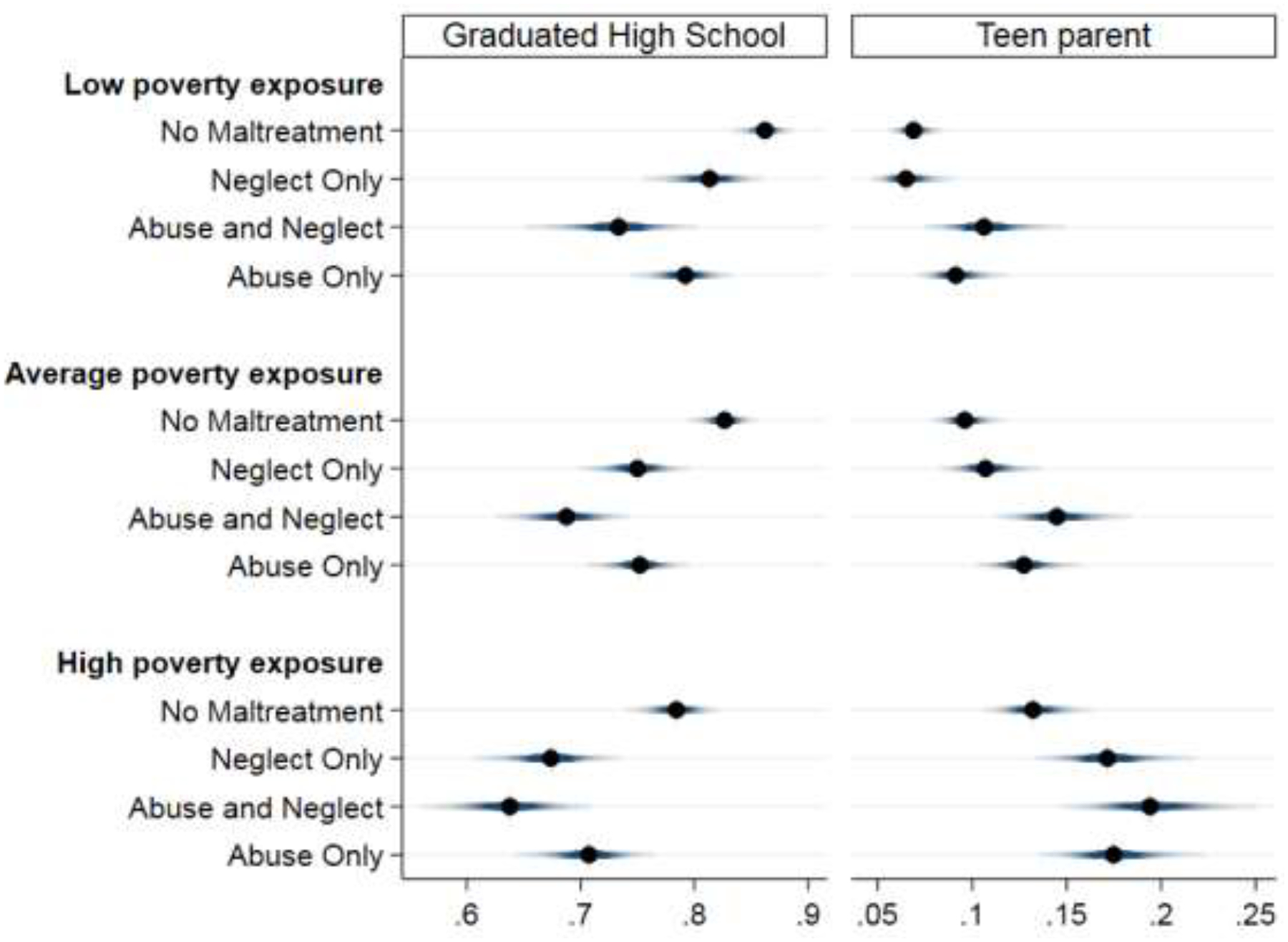

Figure 1 displays predicted probabilities of high school graduation and teen parenthood. Among those with average (sample mean) poverty duration and depth, the predicted probability of high school graduation for NM youth was .83, about 7 percentage points (PP) higher than for NO and AO youth (p<.001), and 14PP higher than AN youth (p<.001). In comparison, the difference in probability of high school graduation for NM youth with high versus average poverty exposure was 5PP, statistically significantly smaller than differences associated with neglect only, abuse only, or combined abuse and neglect. That is, the decrease in probability of high school graduation associated with a CPS investigation is greater than the decrease associated with spending an additional 4.8 years in poverty. At average poverty duration and depth, the probability of teen parenthood for NM youth was .10, similar to the risk for NO youth (p=.107), and 3PP lower than AO youth (p<.001) and 4PP lower than AN youth (p<.001). In comparison, risk for high poverty NM youth was .13, statistically equivalent to the rates of average poverty AO and AN youth, but higher than average poverty NO youth (p=002).

Figure 1.

Probability of High School Graduation and Teen Parenthood by Alleged Maltreatment and Poverty Exposure, Panel B

Notes: Estimates are predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals from logit models including all variables from Table 2 plus interactions between maltreatment and poverty duration, and between maltreatment and poverty depth. Predicted probabilities are estimated treating race and sex as balanced across groups, and holding all other categorical covariates constant at the base category and quantitative covariates at mean.

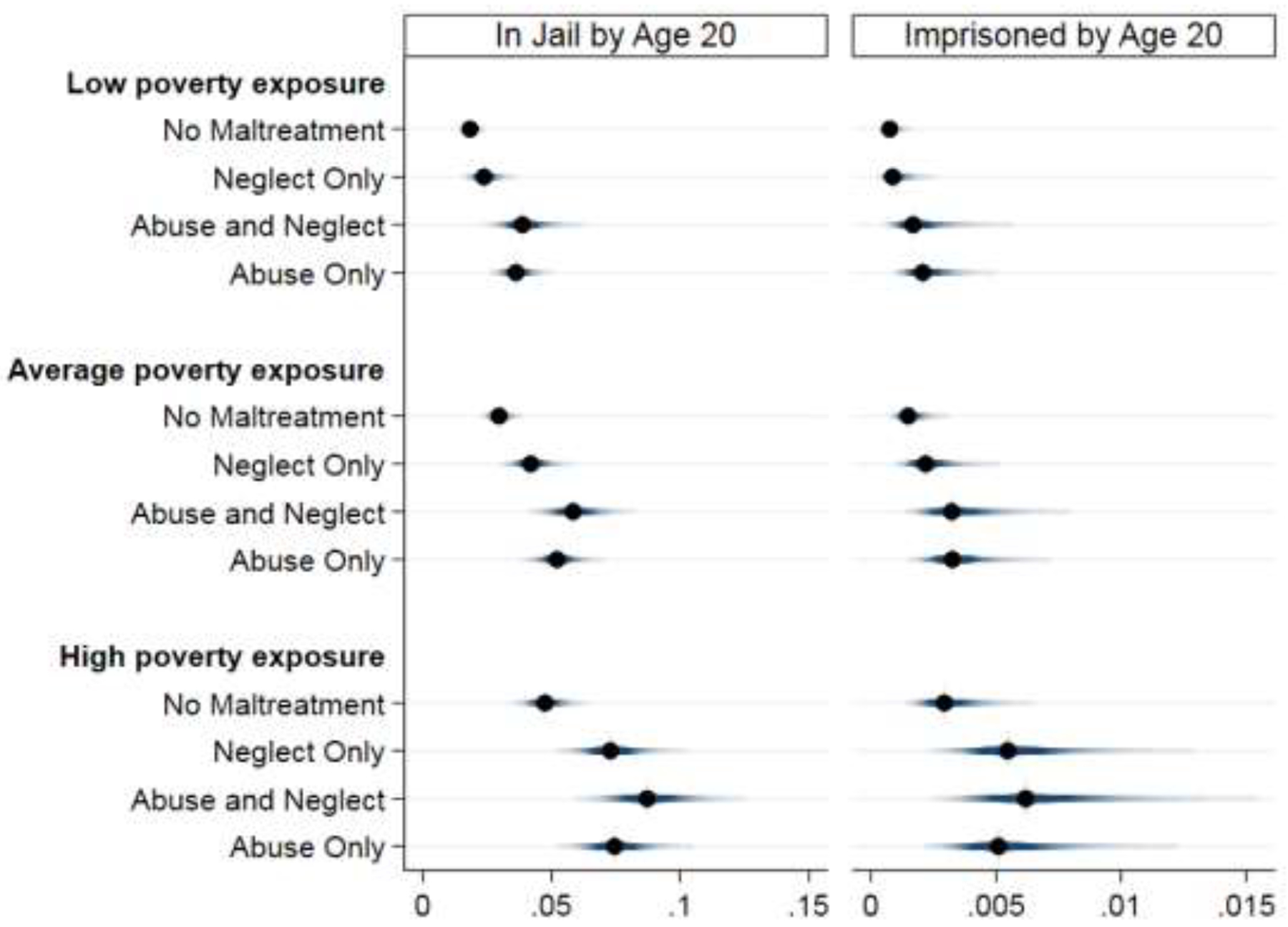

Predicted probabilities of experiencing jail and prison by age 20 are shown in Figure 2. The predicted probability of jail by age 20 was .03 for NM youth at average poverty exposure, 1PP lower than NO youth (p<.001), 3PP lower than AN youth (p<.001), and 2PP lower than AO youth (p<.001). In comparison, NM youth with high poverty exposure were 2PP more likely to experience jail – the ‘effect’ of a 1 SD increase in poverty duration and depth was not significantly different from that of neglect (NO, p=.150), abuse and neglect (AN, p=.052), or abuse (AO, p=.203). Findings for risk of prison were similar to findings for risk of jail.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probabilities of Jail and Prison Incarceration before Age 20 by Alleged Maltreatment and Poverty Exposure, Panel B

Notes: Estimates are predicted probabilities and 95% confidence intervals from logit models including all variables from Table 2 plus interactions between maltreatment and poverty duration, and between maltreatment and poverty depth. Predicted probabilities are estimated treating race and sex as balanced across groups, and holding all other categorical covariates constant at the base category and quantitative covariates at mean.

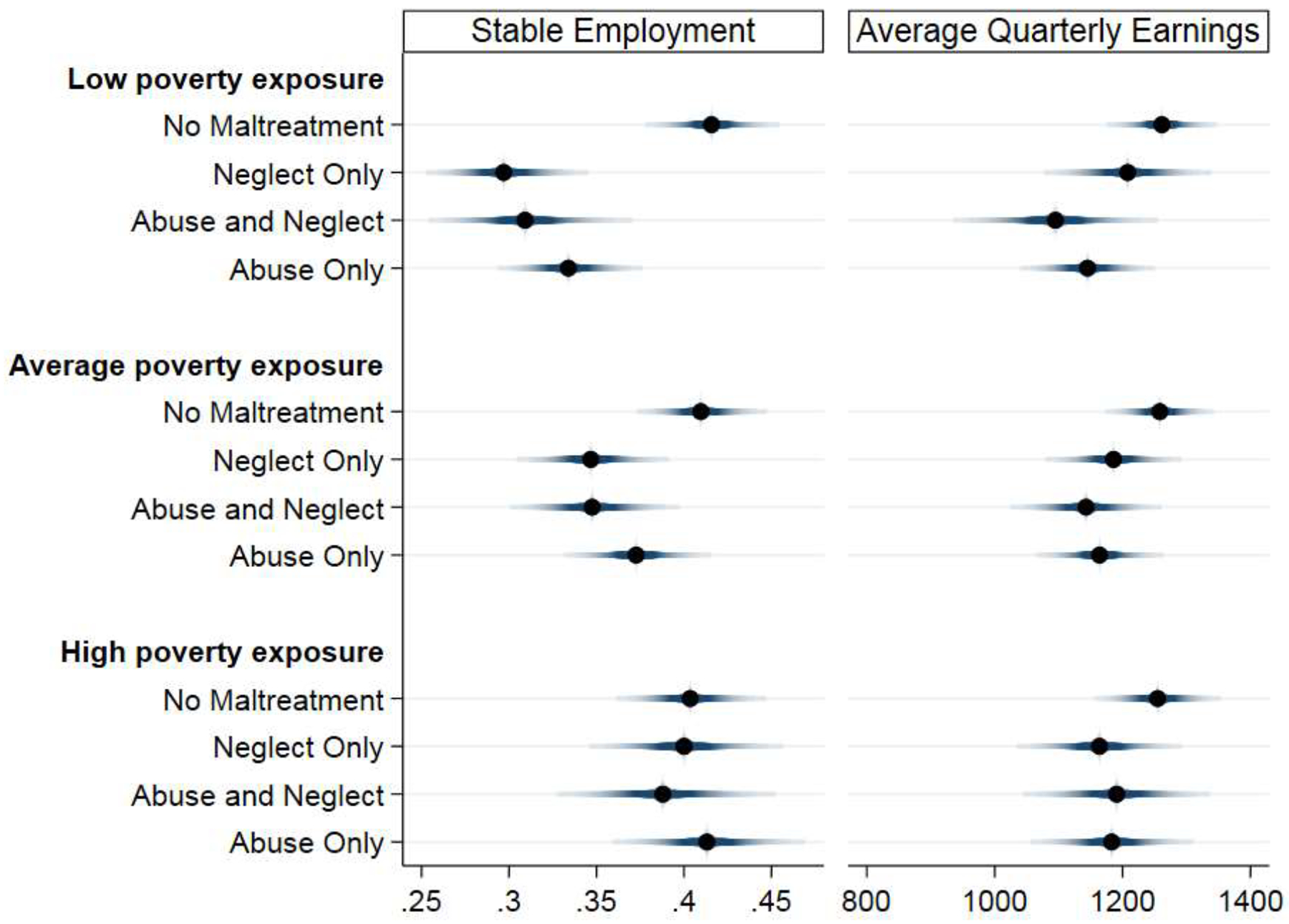

Lastly, the predicted probabilities of stable employment and predicted average quarterly earnings are shown in Figure 3. The predicted probability of stable employment in the 8 quarters after reaching age 18 was .41 for NM youth at average poverty exposure; 6PP lower than for NO youth (p<.001) and AN youth (p<.001), and 4PP lower than AO youth (p<.001). Moreover, all maltreatment groups at average poverty had a lower probability of stable employment (p<=.008) and lower earnings (p<=.026) than NM youth with high poverty exposure.

Figure 3.

Probability of Stable Employment and Mean Quarterly Earnings at Ages 18 and 19, by Maltreatment and Poverty Exposure, Panel B

Notes: Estimates are predicted probabilities (for employment) or means (earnings) and 95% confidence intervals from logit (employment) and linear (earnings) regression models including all variables from Table 2 plus interactions between maltreatment and poverty duration, and between maltreatment and poverty depth. Predicted values are estimated treating race and sex as balanced across groups, and holding all other categorical covariates constant at the base category and quantitative covariates at mean.

Sensitivity Analyses.

We tested additional models with an interaction between poverty depth and poverty duration and a nonlinear term for poverty duration. Neither change substantively altered the results. We also acknowledge possible differences in the effects of substantiated and unsubstantiated investigations. However, because the vast majority of children who never received a CPS intervention also did not have substantiated investigations, it was not possible to separate effects of substantiation and intervention.

Discussion

This study sought to assess whether, and how, the effects of CPS-investigated neglect differ from poverty and from CPS-investigated abuse. Of course, causal effects of maltreatment are difficult to identify, given that experimental designs would be unethical and there are many confounding factors. However, in this study, we improve on prior estimates by accounting for a rich set of longitudinal childhood economic and family characteristics. We found that youth with CPS-investigated neglect have substantially worse outcomes –lower rates of high school graduation and regular employment, and higher rates of teen parenthood and incarceration –than youth without maltreatment allegations who were exposed to similar duration and depth of poverty. Moreover, worse outcomes were observed even for youth with allegations that led to no CPS intervention – ostensibly low-risk cases. Lastly, whereas youth exposed to both abuse and neglect fare worse than youth exposed to a single form of maltreatment, we found no consistent indication that abuse was associated with worse outcomes than neglect. Rather, abuse was more predictive of jail and prison incarceration, whereas neglect was more predictive of lacking stable employment. This is consistent with prior research showing that neglect is strongly associated with cognition and learning, which may affect employment, whereas abuse is more predictive of externalizing behavior, which may manifest in criminal activity (Font & Berger, 2015; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001).

About ninety percent of our maltreatment sample (88% for Neglect only, 93% for Abuse and Neglect, 84% for Abuse only) received food assistance at some point prior to age 16, confirming that the CPS system is overwhelming comprised of children from low-income families. Moreover, the children that reach the attention of CPS spend more time in poverty than other children on public assistance. However, our study suggests that allegations of neglect matter beyond the effects of poverty, and that the process of reporting and screening for investigation is, on average, effectively capturing a distinctly at-risk subset of impoverished youth. Indeed, children identified as at risk of neglect have worse outcomes than impoverished children across multiple domains, even at high levels of poverty. To the extent that the risks of neglectful families are distinct from non-neglectful impoverished families, interventions targeting economic needs alone may be inadequate.

The findings of this study also challenge the perception that neglect is less harmful than abuse. Prior researchers have speculated that this perception may be due to the consequences of abuse being more immediately observable than the consequences of neglect (Dubowitz, 2007). Nevertheless, the divergence in outcomes for neglected youth and impoverished non-neglected youth is significant, at least by early adulthood. Given the prevalence of neglect and the increased risk of adverse outcomes associated with neglect, targeted efforts to prevent and treat the effects of neglect warrant greater priority.

The findings of this study also have implications for the CPS system. Our results suggest that current child protection practice (what is reported to CPS and screened in for investigation) is, on average, identifying a subset of impoverished children at disproportionately high risk of adverse life outcomes – it is not targeting low-income families indiscriminately. At the same time, allegations that led to no intervention were nevertheless associated with adverse outcomes. In other words, alleged maltreatment that is either unable to be proven or is deemed insufficiently severe to warrant intervention is nevertheless a significant predictor of a host of outcomes – net of poverty and demographics. Notably, however, CPS may not be the appropriate agency to address the risks faced by these youth, given that the services provided or procured by CPS predominately focus on reducing the risk that parents will perpetrate new maltreatment, not on children’s health or development (Berger & Font, 2015). As a result, the social-emotional and educational needs of children may not be directly addressed. Increased access to high quality services for all families coming to the attention of CPS, regardless of screening and substantiation decisions is critical for improving outcomes for all children. Some states have implemented tracks in which families who are screened out or unsubstantiated are offered voluntary services to help improve family circumstances in an effort to prevent future maltreatment. However, prevention of future maltreatment may not be sufficient to improve children’s developmental outcomes. Given that factors like teen parenthood, low educational attainment, and criminality are risk factors for perpetrating maltreatment, greater attention to the developmental needs of children investigated by CPS – by way of proper assessment and referral to services for children– may pay dividends via reduced intergenerational transmission.

Limitations and Implications for Future Research

We note several limitations. First, the data are from residents of a single county, and, given variability in how maltreatment is reported and screened across states, these findings may not generalize nationally. For example, agencies that decline to investigate a greater proportion of lower-risk referrals may observe larger differences between its CPS population and the broader population of impoverished children, whereas agencies that investigate most or all referrals may observe weaker differences. Milwaukee County, the site of this study, investigates approximately 80% of reports (Dumas, Elzinga-Marshall, Monahan, van Buren, & Will, 2015) – a higher rate than the national average (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2017).

Second, the measures of maltreatment types are simplistic, given the breadth and depth of allegations that may be investigated. This study demonstrated only that, at various thresholds of poverty, those with neglect allegations have a higher probability of adverse outcomes than those without any maltreatment allegations, and are similar to those with abuse allegations. Yet, it remains possible that, for example, allegations involving inadequate supervision due to parental substance abuse are uniquely predictive of adverse outcomes, whereas allegations pertaining to inadequate housing are not. Although many studies of neglect rely on CPS allegation codes, this remains a serious limitation to the study of neglect. The measures also contain no indication of severity of harm and it is impossible to ascertain whether the abuse and neglect groups were exposed to the same degree of harm or risk of harm. It is possible that there is a different threshold for removal to out-of-home care in cases of abuse than neglect because the impacts are more immediately observable (e.g., physical injuries), and that, as a result, the in-home CPS abuse and neglect groups are substantively dissimilar.

Third, our comparison group suffers some contaminiation (e.g., some of those without identified maltreatment allegations experienced maltreatment) for two reasons: not all maltreatment is investigated by CPS and electronic CPS records were not available prior to 2000. Contamination concerns are somewhat diminished by the numerous years of CPS data, as the cumulative likelihood that a maltreated child reaches the attention of CPS should increase over time. Nevertheless, contamination is likely to downwardly bias our estimates. Studies combining survey and administrative data to account for sample contamination would address this problem.

Fourth, there may be omitted variables that bias our findings. For example, families with neglect allegations may be more likely to have specific forms of material hardship, such as housing instability, than families in our poverty comparison conditions. Housing problems are very common among families involved with CPS (Courtney, McMurtry, & Zinn, 2004) and may be a unique risk factor for adverse outcomes (Slack, Font, Maguire-Jack, & Berger, 2017).

Lastly, we acknowledge limitations to the use of SNAP receipt to measure poverty. Although the vast majority of those eligible receive assistance, especially those at higher rates of poverty (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2017), not all do. Moreover, there may be misreporting in income and assets, which could result in inaccurate estimates of poverty depth for some children. However, because these measures are consistently structured over time, have some degree of validation due to program eligibility verifications, and do not rely on self-report, we argue these measures are preferable to those used in other studies.

Nevertheless, given these limitations, researchers should continue to examine the effects of neglect to confirm or challenge our findings, and our results identify areas where measurement could be improved. Our research points to the need to account for multiple forms of maltreatment exposure. A great deal of existing research focuses on a single form of maltreatment, or measures maltreatment type based on what is alleged at a single point in time. Our findings show that youth exposed to both abuse and neglect fared significantly worse than youth exposed to abuse or neglect alone; thus, studies that focus on abuse without accounting for neglect, or assign a hierarchy of maltreatment in which abuse is assumed to be primary, will likely overstate the effects of abuse. In addition, our study emphasizes the need to disaggregate the multiple subtypes of neglect. For decades, researchers have called for improvement to the measurement of neglect, in order to better identify its antecedents and consequences (Dubowitz, Pitts, & Black, 2004; Slack, Holl, Altenbernd, McDaniel, & Stevens, 2003) but federal data collection through the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System continues to combine all forms of and other prominent surveys of child maltreatment also include limited measures of neglect. More research is needed to determine the longterm effects of neglect subtypes, and, particularly, whether they are distinct from poverty.

Conclusion

The CPS system receives a large volume of referrals each year, most of which involve neglect and result in no intervention. Yet, several years after the alleged incident of neglect, youth are at high risk for adverse outcomes, net of poverty exposure and family characteristics. Indeed, even among those exposed to long-term poverty, those who also have neglect allegations are less likely to graduate high school or to be regularly employed, are more likely to experience incarceration, and have lower earnings. Notably, these findings largely hold even when focusing only on “low-risk” CPS cases (those for which no intervention was provided). For many outcomes, there are no differences between those with neglect allegations and those with abuse allegations, although those with both abuse and neglect allegations are at highest risk of adverse outcomes. In sum, despite that childhood poverty and neglect are frequently comorbid, neglect has distinctly negative associations with youth outcomes, similar to abuse. Given that definitions of neglect are broad and administrative measures are simplistic, we cannot determine what exactly children reported for neglect are experiencing that places them at increased risk. However, this study suggests that it is not poverty alone.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Results

| Graduated high schoola | Teen parenthoodb | Jailc | Prisond | Regularly Employede | Average quarterly earnings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |

| Panel A. Full Sample | ||||||||||||

| Maltreatment Exposure (reference: none known) | ||||||||||||

| Alleged neglect | −.512 | (.053)*** | .222 | (.054)*** | .316 | (.063)*** | .448 | (.113)*** | −.308 | (.045)*** | −107.709 | (21.621)*** |

| Alleged neglect and abuse | −.793 | (.059)*** | .505 | (.057)*** | .750 | (.067)*** | .821 | (.121)*** | −.338 | (.052)*** | −160.404 | (27.800)*** |

| Alleged abuse | −.429 | (.049)*** | .236 | (.051)*** | .503 | (.060)*** | .631 | (.113)*** | −.186 | (.039)*** | −106.389 | (21.829)*** |

| Poverty exposure | ||||||||||||

| Duration | −.005 | (.001)*** | .011 | (.001)*** | .014 | (.001)*** | .017 | (.002)*** | .006 | (.001)*** | 3.006 | (.331)*** |

| Depth | −.007 | (.001)*** | .003 | (.001)** | .002 | (.001) | .006 | (.003)* | −.004 | (.001)*** | −4.321 | (.371)*** |

| Panel B. NM and CPS Non-Intervention | ||||||||||||

| Maltreatment Exposure (reference: none known) | ||||||||||||

| Alleged neglect | −.491 | (.057)*** | .163 | (.059)** | .360 | (.068)*** | .430 | (.122)*** | −.299 | (.048)*** | −90.495 | (26.600)*** |

| Alleged neglect and abuse | −.724 | (.068)*** | .490 | (.067)*** | .643 | (.080)*** | .676 | (.144)*** | −.292 | (.059)*** | −139.182 | (32.391)*** |

| Alleged abuse | −.420 | (.051)*** | .235 | (.053)*** | .514 | (.062)*** | .622 | (.119)*** | −.191 | (.041)*** | −104.678 | (22.884)*** |

| Poverty exposure | ||||||||||||

| Duration | −.005 | (.001)*** | .011 | (.001)*** | .014 | (.001)*** | .018 | (.002)*** | .006 | (.001)*** | 3.157 | (.340)*** |

| Depth | −.006 | (.001)*** | .003 | (.001)* | .002 | (.001) | .007 | (.003)* | −.004 | (.001)*** | −4.264 | (.382)*** |

| Panel C. NM and CPS In-Home Intervention | ||||||||||||

| Maltreatment Exposure (reference, none known) | ||||||||||||

| Alleged neglect | −.617 | (.119)*** | .496 | (.115)*** | .112 | (.149) | .525 | (.235)* | −.359 | (.114)** | −202.141 | (58.730)*** |

| Alleged neglect and abuse | −.950 | (.102)*** | .522 | (.098)*** | 1.001 | (.112)*** | 1.109 | (.188)*** | −.456 | (.096)*** | −219.383 | (50.117)*** |

| Alleged abuse | −.495 | (.135)*** | .263 | (.142) | .425 | (.173)*** | .709 | (.310)* | −.200 | (.116) | −127.885 | (65.079)* |

| Poverty exposure | ||||||||||||

| Duration | −.005 | (.001)*** | .011 | (.001)*** | .015 | (.001)*** | .018 | (.002)*** | .006 | (.001)*** | 3.626 | (.389)*** |

| Depth | −.006 | (.001)*** | .001 | (.001) | .002 | (.002) | .004 | (.003) | −.008 | (.001)*** | −5.110 | (.459)*** |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Panel A: NO≠AN*** AN≠AO***; Panel B: NO≠AN** AN≠AO***; Panel C: NO≠AN* AN≠AO**.

Panel A: NO≠AN*** AN≠AO***; Panel B: NO≠AN*** AN≠AO**.

Panel A: NO≠AN*** NO≠AO** AN≠AO*; Panel B: NO≠AN**; Panel C: NO≠AN*** AN≠AO**.

Panel A: NO≠AN**; Panel C: NO≠AN*.

Panel A: NO≠AO* AN≠AO*.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R21HD091459) and with support from the Capstone Center Translational Center for Child Maltreatment Studies (P50HD089922) and the Population Research Institute at Penn State University (P2CHD041025). We thank the Wisconsin Dept. of Children and Families, Dept. of Health Services, Dept. of Corrections, Dept. of Public Instruction, and Dept. of Workforce Development for the use of data, but acknowledge that these agencies do not certify the accuracy of the analyses presented.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah Font, Pennsylvania State University, 612 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802.

Kathryn Maguire-Jack, University of Michigan, School of Social Work 1080 S. University Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

References

- Afifi TO, McTavish J, Turner S, MacMillan HL, & Wathen CN (2018). The relationship between child protection contact and mental health outcomes among Canadian adults with a child abuse history. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, & Font SA (2015). The role of the family and family-centered programs and policies. Future of Children, 25(1), 155–176. doi: 10.1353/foc.2015.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, Font SA, Slack KS, & Waldfogel J (2017). Income and Child Maltreatment in Unmarried Families: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(4), 1345–1372. doi: 10.1007/s11150-016-9346-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LM, & Waldfogel J (2011). Economic determinants and consequences of child maltreatment. Retrieved from OECD website: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/economic-determinants-and-consequences-of-child-maltreatment_5kgf09zj7h9t-en

- Cancian M, Yang M-Y, & Slack KS (2013). The effect of additional child support income on the risk of child maltreatment. Social Service Review, 87(3), 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-Y, Propp J, & Corvo K (2011). Child neglect and its association with subsequent juvenile drug and alcohol offense. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28(4), 273. [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2014). Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/statutes/define.pdf

- Chill P (2018). Hundreds Of U.S. Children Taken From Home. Hartford Courant; Retrieved from http://www.courant.com/opinion/op-ed/hc-op-chill-removing-children-20180625-story.html [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, & Simons RL (1994). Economic Stress, Coercive Family Process, and Developmental Problems of Adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00768.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, McMurtry SL, & Zinn A (2004). Housing problems experienced by recipients of child welfare services. Child Welfare, 83(5), 393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davern M, Rodin H, Beebe TJ, & Call KT (2005). The effect of income question design in health surveys on family income, poverty and eligibility estimates. Health Services Research, 40(5p1), 1534–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan S (2018, November 2). Family Separation: It’s a Problem for U.S. Citizens, Too. The New York Times; Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/22/us/family-separation-americans-prison-jail.html [Google Scholar]

- Dolan M, Smith K, Casanueva C, & Ringeisen H (2011). Nscaw II Baseline Report: Introduction to Nscaw II Final Report OPRE Report 2011–27a. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H (2007). Understanding and addressing the “neglect of neglect:” Digging into the molehill. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(6), 603–606. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Pitts SC, & Black MM (2004). Measurement of three major subtypes of child neglect. Child Maltreatment, 9(4), 344–356. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas A, Elzinga-Marshall G, Monahan B, van Buren M, & Will M (2015). Child Welfare Screening in Wisconsin: An Analysis of Families Screened Out of Child Protective Services and Subsequently Screened In. Retrieved from Department of Children and Families website: https://www.lafollette.wisc.edu/images/publications/workshops/2015-dcf.pdf

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, & Votruba-Drzal E (2017). Moving beyond correlations in assessing the consequences of poverty. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 413–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK, & Kopels S (2004). ‘For reasons of poverty’: Court challenges to child welfare practices and mandated programs. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(9), 821–836. [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Upadhyaya MP, Litrownik AJ, Marshall JM, Runyan DK, Graham JC, & Dubowitz H (2005). Maltreatment’s wake: The relationship of maltreatment dimensions to child outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 597–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein WM (2006). Response bias in opinion polls and American social welfare. The Social Science Journal, 43(1), 99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2005.12.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fein DJ, & Lee WS (2003). The impacts of welfare reform on child maltreatment in Delaware. Children and Youth Services Review. [Google Scholar]

- Font SA, & Berger LM (2015). Child maltreatment and children’s developmental trajectories in early to middle childhood. Child Development, 86(2), 536–556. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, & Lennon MC (2007). Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development, 78(1), 70–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt S, Buckley H, & Whelan S (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8), 797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes RC, Rycus JS, Saunders-Adams SM, Hughes LK, & Hughes KN (2013). Issues in differential response. Research on Social Work Practice, 23(5), 493–520. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, & Kotch JB (2005). Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, & Kohl PL (2009). Is the overrepresentation of the poor in child welfare caseloads due to bias or need? Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 422–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 274–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Jonson-Reid M, & Drake B (2009). Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreatment, 14(1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Leeb RT, English D, Graham JC, Briggs EC, Brody KE, & Marshall JM (2005). What’s in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 533–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, & Cicchetti D (2001). Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology, 13(04), 759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Lynch M, Oshri A, Herzog M, & Wortel SN (2013). The impact of neglect on initial adaptation to school. Child Maltreatment, 18(3), 155–170. doi: 10.1177/1077559513496144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayes LC, & Truman SD (2002). Chapter 13: Substance abuse and parenting In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting volume 4: social conditions and applied parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 329–359). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, & Shanahan MJ (1993). Poverty, parenting, and children’s mental health. American Sociological Review, 351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BD, & Mittag N (2015). Using linked survey and administrative data to better measure income: Implications for poverty, program effectiveness and holes in the safety net. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Jellinek M, Quinn D, Smith G, Poitrast FG, & Goshko M (1991). Substance abuse and serious child mistreatment: Prevalence, risk, and outcome in a court sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 15(3), 197–211. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90065-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newland RP, Crnic KA, Cox MJ, & Mills-Koonce WR (2013). The family model stress and maternal psychological symptoms: Mediated pathways from economic hardship to parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton LH (2016). Separating coercion from provision in child welfare: Preventive supports should be accessible without conditions attached. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51(1), 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R, & Howard K (2013). The parenting gap. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-parenting-gap/

- Roberts DE (2014). Child protection as surveillance of African American families. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 36(4), 426–437. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, & Earls F (1997). Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Peta I, McPherson K, Greene A, & Li S (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved on July, 9, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Semidei J, Radel LF, & Nolan C (2001). Substance abuse and child welfare: Clear linkages and promising responses. Child Welfare, 80(2), 109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Font S, Maguire-Jack K, & Berger LM (2017). Predicting Child Protective Services (CPS) Involvement among Low-Income US Families with Young Children Receiving Nutritional Assistance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(10), 1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl J, Altenbernd L, McDaniel M, & Stevens AB (2003). Improving the measurement of child neglect for survey research: Issues and recommendations. Child Maltreatment, 8(2), 98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel M, Yoo J, & Bolger K (2004). Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment, 9(4), 395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry DE, Sperry LL, & Miller PJ (2019). Reexamining the Verbal Environments of Children From Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds. Child Development, in press. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Vanderminden J, Finkelhor D, & Hamby S (2019). Child Neglect and the Broader Context of Child Victimization. Child Maltreatment, 1077559518825312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2017). Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: Fiscal Year 2010 to Fiscal Year 2015. Retrieved from https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/ops/Trends2010-2015.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Child Maltreatment 2016. Retrieved from Author, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau website: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2016.pdf

- Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Rogosch FA, & Cicchetti D (2015). Different forms of child maltreatment have comparable consequences among children from low-income families. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(11), 1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin DR (2007). The effects of family and community violence exposure among youth: Recommendations for practice and policy. Journal of Social Work Education, 43(1), 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler R (2019, 23). Little AJ Freund’s horrific death is not an argument for tearing up more families. Chicago Sun-Times; Retrieved from https://chicago.suntimes.com/2019/5/23/18629508/aj-freund-child-abuse-dcfs-joseph-wallace [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM, & Burdette HL (2007). The association between maltreatment and obesity among preschool children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(11), 1187–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White OG, Hindley N, & Jones DP (2015). Risk factors for child maltreatment recurrence: An updated systematic review. Medicine, Science and the Law, 55(4), 259–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M-Y, & Maguire-Jack K (2016). Predictors of basic needs and supervisory neglect: Evidence from the Illinois Families Study. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young NK, Boles SM, & Otero C (2007). Parental substance use disorders and child maltreatment: Overlap, gaps, and opportunities. Child Maltreatment, 12(2), 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]