Abstract

Inflammatory diseases are an important health concern and have a growing incidence worldwide. Thus, developing novel and safe drugs to treat these disorders remains an important pursuit. Artemisia iwayomogi, locally known as Dowijigi (DJ), is a perennial herb found primarily in Korea and is used to treat various diseases such as hepatitis, inflammation and immune disorders. In the present study, the anti-inflammatory effects of a polyphenolic extract from the DJ flower (PDJ) in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were investigated. Cell cytotoxicity was assessed using the MTT assay. The production of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was measured by Griess and ELISA analysis, respectively. The expression levels of inducible nitric oxide (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) were examined by western blot analysis. Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR was performed to detect the mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-1β, as well as COX2 and iNOS. The production of NO and PGE2 was significantly decreased following treatment with PDJ. The mRNA expression levels of TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, COX2 and iNOS were significantly decreased in LPS-induced PDJ co-treated cells compared with the group treated with LPS alone. Western blot analysis indicated that PDJ downregulated the LPS-induced expression of iNOS and COX2, as well as the expression of NF-κB proteins. In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that PDJ exerted anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-induced macrophage cells by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway. Therefore, PDJ may be used as a potential therapeutic agent in inflammation.

Keywords: Dowijigi, anti-inflammation, inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2, NF-κB signaling

Introduction

Inflammation is an important adaptive mechanism of the host immune response, and typically occurs at the site of infection. Inflammation is caused by cell injury and toxin exposure and is associated with a number of pathological conditions (1,2). Inflammation plays a vital role in the body's defense system via multiple mediators that allow cells to recover from damage and to regulate tissue homeostasis (3,4). Excessive and continuous inflammation can cause severe tissue damage that can lead to a series of disordered states, including hepatitis, pneumonia, atherosclerosis, septic shock and rheumatoid arthritis (5–7). The normal inflammatory response is self-limiting and is maintained by the downregulation of pro-inflammatory proteins and the upregulation of anti-inflammatory proteins (4). Therefore, targeting dysregulated inflammatory processes and regulating inflammatory mediators are regarded to be effective therapeutic approaches to managing inflammatory disorders (8,9).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is one of the most effective activators of macrophages (10). LPS induces the production of inflammatory cytokines and mediators such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2 and IL-18, resulting in the induction of inflammatory genes like TNF-α, CXCL10, IL-2B and IL-10 via the activation of specific signaling cascades, at the transcription level (4,11). The imbalance and build-up of oxidative stress in the cellular environment in disease conditions, including inflammation, stroke, cancer and diabetes, often increases the generation of reactive oxygen species (12–14). LPS-stimulated macrophages induce the production of large amounts of inflammatory mediators, including nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). NO and PGE2 are secreted in inducible isoforms, iNOS and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), during the inflammatory response (15,16).

The nuclear transcription factor NF-κB is an important regulator that initiates inflammation (17). NF-κB is activated by a series of intracellular signals involving inhibitor of κB kinase (IKK)α/β proteins and its phosphorylation (18). The binding of LPS to the toll-like receptors (TLR) of activated macrophages leads to the phosphorylation and activation of IKK proteins, which allows the translocation of NF-κB into the cell nucleus, where pro-inflammatory cytokines are transcribed (19). A reduction in NF-κB signaling pathway activity and the expression of its related proteins have been shown to alleviate inflammatory responses (20). Thus, the NF-κB signaling pathway is a crucial target in the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Artemisia iwayomogi, commonly known as Dowijigi (DJ), is a perennial herb that belongs to the composite asteraceae family, primarily found in Korea (21). A. iwayomogi exerts various biological effects such as anti-oxidation, anti-inhibition and anti-inflammation, and has been widely used in the treatment of various diseases, including hepatitis, inflammation, cholecystitis and immune-related disorders (22). Methanolic extracts of A. iwayomogi have been shown to exhibit scavenging activity in a number of diseases involving inflammation, and to inhibit NO production by LPS-activated macrophages (23). However, the mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of DJ remains largely unknown. The anti-inflammatory activities of the polyphenolic extract of Dowijigi (PDJ) can be assessed by measuring their potential to inhibit the production of inflammatory intermediates (24). Since macrophages play an important role in inflammation and immune defense responses, RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cells are one of the most commonly used cell line models to evaluate the anti-inflammatory effect of drugs in vitro (25). In the present study, the inhibitory effect of PDJ on inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and the underlying mechanism of action were investigated.

Materials and methods

Plant material

A. iwayomogi plants were collected in May 2018 from Namhae Island. The plant samples were authenticated under the Korea Animal Bioresource Research Bank (plant registration no. 00754C). The voucher specimens were deposited at the herbarium of the Research Institute of Life Science. The flowers were separated from the plants and were washed with water, lyophilized and stored at −20°C prior to extraction.

Preparation of the PDJ

The lyophilized flowers were weighed (100 g) and refluxed in 70% methanol (2 liters) at 60°C for 20 h. The extracted mixture was filtered through a Büchner funnel and concentrated to ~300 ml at 35°C at a variable pressure, using a rotary evaporator. To remove non-polar impurities from the concentrated filtrate, the filtrate was washed with n-hexane (300 ml) three times. Furthermore, the filtrate was extracted using ethyl acetate (100 ml) three times and dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate. The solvent was removed from the rotatory evaporator. The resulting sticky residue was placed on the top of a silica gel sorbent (40×2.5 cm) and eluted with ethyl acetate to eliminate highly polar impurities. The solvent was then removed to yield solids of polyphenol mixture (1.74 g; 1.74% of the lyophilized plants). The mixture was stored at −20°C until analysis.

High-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) analysis

HPLC analysis was conducted using a 1260 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) with a multiple wavelength detector set at 254, 280, 320 or 360 nm. A Prontosil C18 column (length, 250 mm; inner diameter, 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 µm; Phenomenex Co., Ltd.); Bischoff Chromatography) set at 30°C was used. The binary mobile phase system consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). The gradient conditions were 0–10 min at 10% B, 10–60 min at 10–40% B, 60–70 min at 40–50% B, 70–80 min at 50–10% B and 80–90 min at 10% B. The flow rate was maintained at 1 ml/min and a sample injection volume of 10 µl was used in each experiment. The electrospray ionization MS/MS analysis was conducted using a 3200 QTrap LC/MS/MS system (Applied Biosystems, Fortser, CA, USA) operated in negative ion mode (spray voltage set at −4.5 kV) and nitrogen at a pressure of 45 psi was used as nebulizing agent and drying gas was supplied. The mass spectra were recorded in the range of m/z 100–1000. The obtained data were analyzed using BioAnalystTM software (version 1.4.2; SCIEX).

Cell culture

Mouse RAW264.7 macrophage cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in complete DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

RAW264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells per well in 96 well plate and then cultured with or without LPS (1 µg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) pre-treatment at 37°C for 1 h, followed by treatment with various concentration of PDJ (0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/ml) at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, MTT solution (10 µl; 5 mg/ml) was added to the plate and the cells were incubated at 37°C for ~4 h. Then, the culture media was washed off completely and the insoluble formazan crystals formed were dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 590 nm using a PowerWave HT microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

Griess assay for NO detection

NO production in the cell cultures was measured using the Promega Griess Reagent system (Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, RAW264.7 cells were cultured at a density of 1×104 cells per well in 96-well plates with or without LPS pre-treatment at 37°C for 1 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with either 2.5 or 5 µg/ml PDJ and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, the media in each group was collected and mixed with 50 µl sulfanilamide solution and 50 µl Griess reagent for 10 min at room temperature, protected from light. The nitrate concentration was measured at a wavelength of 520 nm. Sodium nitrite was used to generate the standard curve and NO production in the culture medium was estimated from the NO2 concentration.

ELISA

RAW264.7 cells were seeded at a density of 5×104 per well in 48-well plates. The cells were pre-treated with 1 µg/ml LPS at 37°C for 1 h and then incubated with 2.5 or 5 µg/ml of PDJ for 24 h at 37°C. Levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα were quantified using the mouse IL-1β (cat. no. ADI-900-132A; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.), IL-6 (cat. no. ADI-900-045; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.) and TNFα (cat. no. ADI-900-047; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.) ELISA kits, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

ELISA for measuring PGE2 levels

PGE2 levels in the cells were analyzed using a PGE2 assay kit (cat. no. ADI-900-001; Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.), according to manufacturer's protocol. RAW264.7 cells were cultured at a density of 1×104 cells per well in 96-well plates with or without LPS pre-treatment at 37°C for 1 h. Cells were subsequently treated with either 2.5 or 5 µg/ml PDJ and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After PDJ treatment, 100 µl standard diluent was added to the ELISA plate, followed by 100 µl sample and ~50 µl assay buffer. Then, 50 µl PGE2 conjugate was added to the plate, followed by 50 µl PGE2 antibody. No antibody was added to the blank wells. The plates were incubated for 2 h on a shaker at room temperature. After 2 h, the contents of the wells were emptied and the wells were washed three times with 400 µl of 1X wash solution from the PGE2 assay kit. After the final wash, media were aspirated from the wells and 5 µl conjugate solution was added. Subsequently, 200 µl p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate solution was added to the wells followed by incubation at room temperature for ~45 min without shaking. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 µl stop solution to the wells and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 405 nm.

Determination of protein expression by western blot analysis

For western blot analysis, RAW264.7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 6×105 cells/well and treated with 2.5 or 5 µg/ml PDJ for 24 h at 37°C. Then, the cells were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 SDS and 1% NP-40]. Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce™ bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of protein (~10 µg) were separated on via SDS-PAGE on 10% gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes using the TE 77 Semi-Dry Transfer Unit (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The blots were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk and 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were further incubated with 1:1,000 dilutions of primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies of COX-2 (cat. no. 12282S; 1:1,000), iNOS (cat. no. 13120S; 1:1,000), p65 (cat. no. 8242S; 1:1,000), p-p65 (cat. no. Ser536; 3033S; 1:1,000), IκBα (cat. no. 4812S; 1:1,000), p-IκBα (Ser32; cat. no. 2859S; 1:1,000), JNK (cat. no. 9258S, 1:1,000), p-JNK1/2 (Thr183/Tyr185; cat. no. 4671S, 1:1,000), p38 (cat. no. 8690S; 1:1,000), p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182; cat. no. 9216S, 1:1,000), ERK1/2 (cat. no. 4695S; 1:1,000), p-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; cat. no. 4970S, 1:1,000), and β-actin (cat. no. 3700S, 1:10,000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. The membranes were washed three times for 10 min with TBST and then probed with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit and anti-mouse, A120-101P and A90-116P, respectively, Bethyl Laboratory, Inc.) for 3 h at room temperature. The blots were visualized using Clarity™ ECL substrate reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) with β-actin as the loading control. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Determination of mRNA expression by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

To determine the mRNA expression levels of related proteins, RAW264.7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5×105 cells/well and treated with LPS at 37°C for 1 h, followed by co-treatment with 2.5 or 5 µg/ml PDJ for 24 h at 37°C. The total RNA content was isolated using Trizol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the concentration of RNA was measured using a spectrophotometer. Total RNA (1 µg) was converted to cDNA using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and qPCR was performed with AccuPower® 2X Greenstar™ qPCR Mastermix (Bioneer Corporation) and a CFX384 Real Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) according to each manufacturer's protocol, respectively. The qPCR primers used were as follows: TNFα sense, 5′-TGGAGTCATTGCTCTGTGAAGGGA-3′ and antisense, 5′-AGTCCTTGATGGTGGTGCATGAGA-3′; IL-6 sense, 5′-GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC-3′ and antisense, 5′-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA-3′; IL-1β sense, 5′-TGCAGAGTTCCCCAACTGGTACATC-3′ and antisense, 5′-GTGCTGCCTAATGTCCCCTTGAATC-3′; iNOS sense, 5′-TCCTACACCACACCAAAC-3′ and antisense, 5′-CTCCAATCTCTGCCTATC-3′; COX2 sense, 5′-CCTCTGCGATGCTCTTCC-3′ and antisense, 5′-TCACACTTATACTGGTCAAATCC-3′; and β-actin sense, 5′-TACTGCCCTGGCTCCTAGCA-3′ and antisense, 5′-TGGACAGTGAGGCCAGGATAG-3′. The thermocycling conditions were as follows: Pre-denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec, 58°C for 30 sec and 95°C for 5 sec. All the data were analyzed using Bio-Rad CFX Manager Version 3.1 software. Relative quantification was measured using the 2−ΔΔCq method (26). The mRNA expression levels were normalized against β-actin.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.02; GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistically significant differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Separation and quantification of PDJ

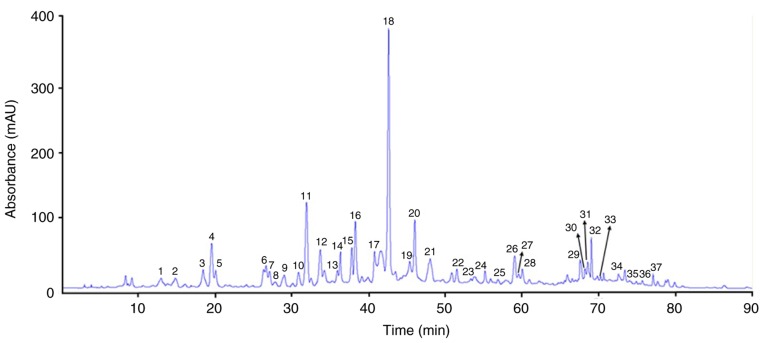

PDJ was separated and quantified using HPLC-MS/MS. A total of 37 peaks were identified based on the HPLC retention times and the UV-vis spectra (Fig. 1). The phenolic compounds and flavonoids were identified according to the peaks obtained in the HPLC chromatogram and the description of their mass spectrometry quantification data based on the reference compounds from published sources are provided in Table I.

Figure 1.

High-performance liquid chromatography chromatogram of polyphenols obtained from the flower extract of Artemeisa iwayonogi (Dowijigi).

Table I.

MS/MS data of the polyphenols in Artemisia iwayonogi (Dowijigi).

| Peak no. | Compound | Retention time (min) | UV max, nm | [M-H]− | MS/MS | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protocatechuic aldehyde | 12.866 | 278, 310 | 137 | 109 | (40) |

| 2 | Gallocatechin | 14.713 | 272 | 305 | 261, 221, 219, 179 | (41) |

| 3 | Methyl catechin | 18.337 | 272 | 305 | 137 | (42) |

| 4 | Epicatechin | 19.460 | 272 | 305 | 139 | (42) |

| 5 | Caffeic acid | 19.979 | 323 | 179 | 135 | (43) |

| 6 | Epigallocatechin | 26.570 | 272 | 305 | 261, 221, 219, 179 | (41) |

| 7 | Catechin | 27.003 | 272 | 289 | 245, 205 | (41) |

| 8 | 5-caffeoylquinic acid | 27.718 | 284 | 353 | 191 | (41) |

| 9 | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate | 28.929 | 294 | 457 | 331, 305, 169 | (41) |

| 10 | 5-Feruoylquinic acid | 30.802 | 272 | 367 | 193, 191, 173 | (44) |

| 11 | Rhamnose-C-acetyl-hexoside apigenin | 31.828 | 344 | 619 | 499, 457, 413, 341, 311, 293, 315 | (45) |

| 12 | Liquiritigenin-7-O-sulfate | 33.610 | 342 | 335 | 255, 135, 119 | (46) |

| 13 | Quercetin-rutinoside | 35.853 | 254, 352 | 609 | 301 | (41) |

| 14 | Quercetin-3-galactoside | 36.234 | 254, 370 | 463 | 301 | (47) |

| 15 | Quercetin-3-glucoside | 37.718 | 256, 354 | 463 | 301 | (47) |

| 16 | Malyidin-3-glucoside | 38.211 | 256, 354 | 493 | 331 | (48) |

| 17 | 3,4-di-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 40.702 | 326, 300 | 515 | 353, 335, 191, 179, 173 | (49) |

| 18 | 3,5-di-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 42.525 | 328, 300 | 515 | 353, 354, 191, 179 | (9) |

| 19 | Quinic acid derivate | 45.298 | 324, 226 | 515 | 353, 335, 191, 179, 173 | (50) |

| 20 | 4,5-di-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 45.929 | 326, 300 | 515 | 353, 335, 317, 299, 191, 179, 173 | (49) |

| 21 | Mearnsetin-O-diglucoside | 47.971 | 330 | 655 | 535, 493, 492, 331, 329, 316, 301 | (50) |

| 22 | Quercetin diglycoside | 51.437 | 330 | 771 | 609, 463, 608, 301, 300 | (49) |

| 23 | Quercetin dihexoside | 53.260 | 354 | 625 | 463, 301 | (45) |

| 24 | Caffeoyl dihexoside | 53.816 | 328 | 503 | 342, 341, 179 | (49) |

| 25 | 3-Caffeoyl-4-feruoyl-quinic acid | 56.817 | 322, 286 | 529 | 367, 353, 255, 203, 191, 179, 173 | (50) |

| 26 | Luteolin | 58.962 | 358, 254 | 285 | 133 | (51) |

| 27 | Isorhamnetin | 59.497 | 344, 268 | 315 | 300 | (51) |

| 28 | 5,7,4′,5′-Tetrahydroxy-6,3′-Dimethoxyflavone | 59.991 | 348, 270 | 345 | 330, 315, 287, 259, 136 | (44) |

| 29 | Mearnsetin-glu | 67.527 | 335, 265 | 493 | 478, 331, 330, 316, 315 | (50) |

| 30 | Gliricidin | 68.182 | 330, 272 | 299 | 284, 271, 256, 212, 175 | (52) |

| 31 | Kaempferol methylether | 68.523 | 348, 266 | 299 | 285, 255, 227 | (45) |

| 32 | 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,4′-dimetoxyflavone | 69.006 | 343, 272 | 329 | 314, 299 | (47) |

| 33 | 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,4′-dimetoxyflavone | 70.197 | 343, 272 | 329 | 314, 299 | (47) |

| 34 | 5,7,3′-Trihydroxy-6,4′-dimetoxyflavone | 72.526 | 343, 272 | 329 | 314, 299 | (47) |

| 35 | 3-Hydroxy-6,7,4′-trimethoxy flavone | 74.865 | 336, 247 | 343 | 328, 327, 313, 261 | (50) |

| 36 | Quercetagetin-tetramethyl ester | 75.648 | 354, 272 | 373 | 358, 343, 328, 313 | (47) |

| 37 | Genkwanin | 77.049 | 335, 268 | 283 | 268 | (47) |

MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry. [M-H], M; Main structure and H; Hydrogen ion.

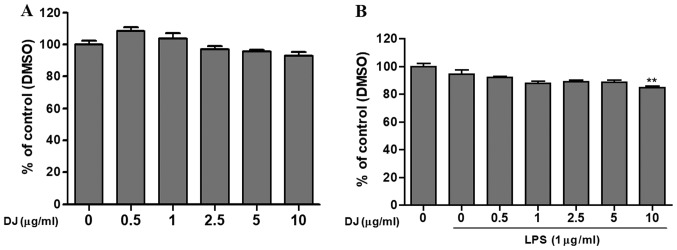

Cytotoxic effect of PDJ in RAW264.7 cells

To identify the non-toxic dose of PDJ, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PDJ (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/ml) following pre-treatment with or without LPS for 1 h. The results suggested that concentrations of PDJ ≤10 µg/ml were non-toxic, therefore, doses of 2.5 and 5 µg/ml were used for subsequent experiments (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic effect of PDJ on RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with or without LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 or 10 µg/ml) at 37°C for 24 h. (A) Effect of PDJ on non-LPS-induced cell viability in RAW264.7 cells. (B) Effect of PDJ on LPS-induced cell viability in RAW264.7 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **P<0.005 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

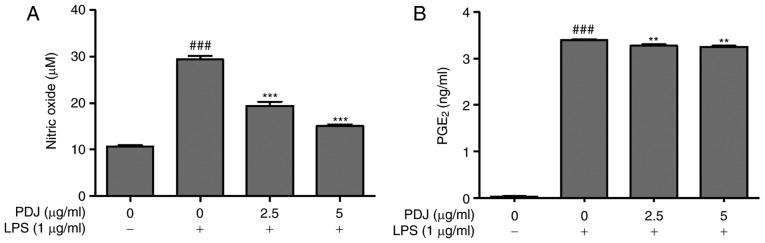

PDJ inhibits LPS-induced NO production and PGE2

The effect of PDJ on NO production in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells was measured by the Griess assay. Cells were pre-treated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 1 h followed by treatment with PDJ (2.5 or 5 µg/ml). Treatment with LPS induced a significant (P<0.001) increase in NO production, which was suppressed upon further treatment with PDJ at both concentrations (Fig. 3A). Thus, there was a decrease in the NO accumulation in the cells co-treated with PDJ and LPS compared with those treated with LPS alone. The level of PGE2 in the LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells treated with PDJ was measured using a PGE2 ELISA kit. The intensity of the bound antibody was measured to calculate the concentration of PGE2 in the PDJ-treated cells. The results displayed that PGE2 levels significantly (P<0.001) decreased upon treatment with PDJ compared with LPS-only treated cells (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Effect of PDJ on LPS-induced production of the inflammatory mediators NO and PGE2 in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml) for 24 h. (A) NO production. (B) PGE2 production. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ###P<0.001 vs. untreated group; **P<0.005 vs. LPS-only treated group; ***P<0.001 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2.

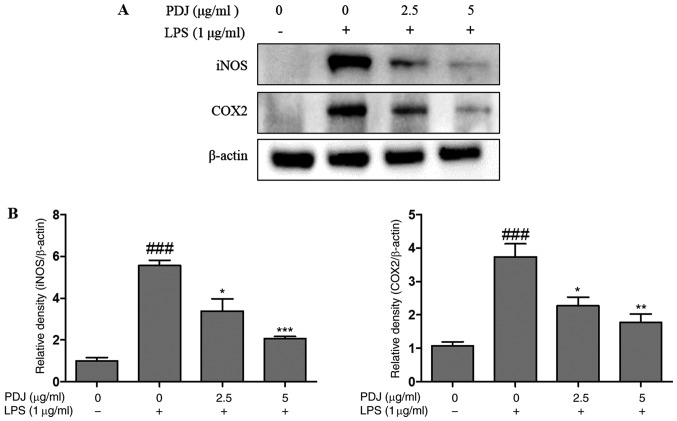

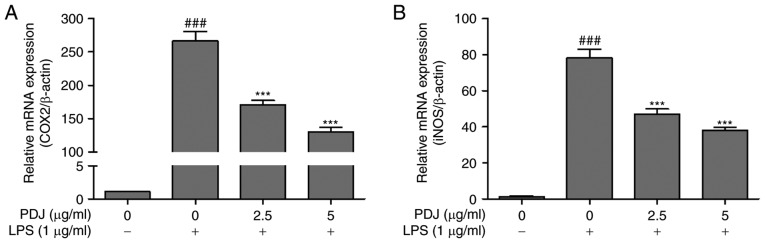

PDJ inhibits LPS-induced mRNA and protein expression of iNOS and COX2

The effect of PDJ on COX2 and iNOS mRNA and protein expression levels in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells was evaluated by RT-qPCR analysis and western blotting, respectively. The expression of COX2 and iNOS in RAW264.7 cells stimulated with LPS was significantly (P<0.001) increased compared with the non-LPS treated control cells, at both the protein (Fig. 4A and B) and mRNA (Fig. 5A and B) level. However, the protein and mRNA expression levels of COX2 and iNOS in the RAW264.7 cells were significantly (P<0.001) decreased after treatment with PDJ. The results indicated that PDJ downregulated LPS-induced COX2 and iNOS expression at both the mRNA and protein levels.

Figure 4.

Effect of PDJ on LPS-induced iNOS and COX2 protein expression levels in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml) at 37°C for 24 h. (A) Protein expression levels of iNOS and COX2 in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells co-treated with PDJ. β-actin was used as the loading control. (B) Relative expression of iNOS and COX2 bands from western blotting were quantified by densitometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ###P<0.001 vs. untreated group; *P<0.05 vs. LPS-only treated group; **P<0.01 vs. LPS-only treated group; ***P<0.001 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2.

Figure 5.

Effect of PDJ on the LPS-induced mRNA expression of COX2 and iNOS in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml) at 37°C for 24 h. mRNA expression levels of (A) COX2 and (B) iNOS were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ###P<0.001 vs. untreated group; ***P<0.001 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2.

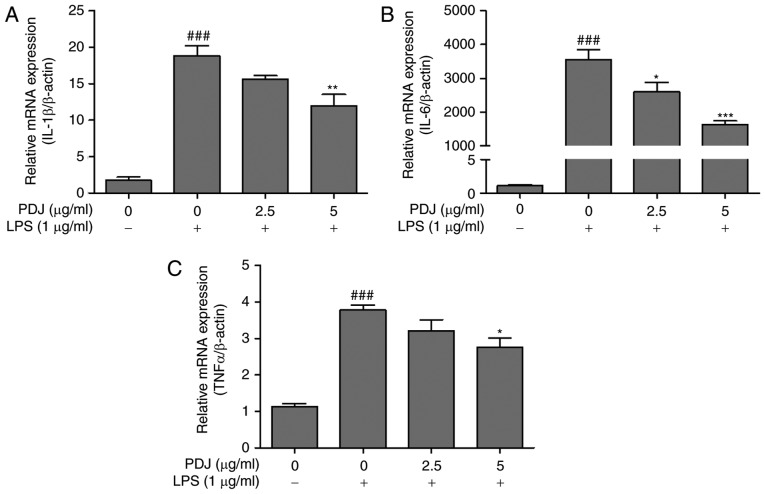

PDJ inhibits LPS-induced mRNA expression of the inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-6 and IL-1β

The effect of PDJ on the mRNA expression levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells was evaluated by RT-qPCR. mRNA levels of the inflammatory cytokines were significantly increased (P<0.001) following LPS treatment compared with the untreated control group. The levels of IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα expression decreased in LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells that were also treated with PDJ (Fig. 6A-C). The results indicated that PDJ suppressed cytokine expression at the transcriptional level in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells.

Figure 6.

Effect of PDJ on the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression levels in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml) for at 37°C 24 h. mRNA expression levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (A) IL-1β, (B) IL-6 and (C) TNFα were measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ###P<0.001 vs. untreated group; *P<0.05 vs. LPS-only treated group; **P<0.01 vs. LPS-only treated group; ***P<0.001 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

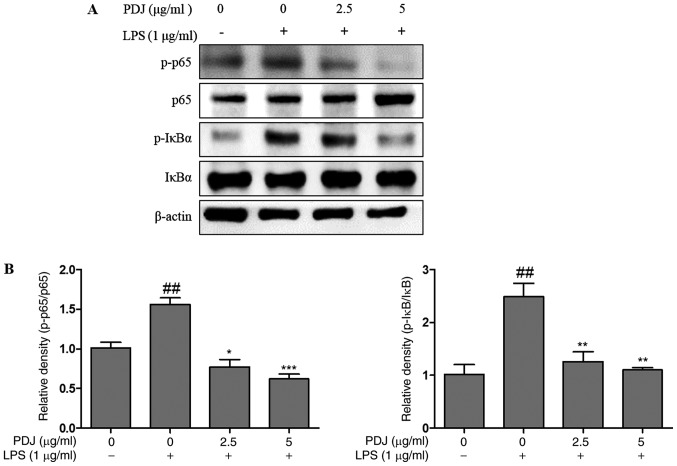

PDJ induces anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells via regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway

The effect of PDJ on the LPS-induced degradation and phosphorylation of NF-κB proteins and the expression levels of inhibitor of κBα (IκBα) and p65 were analyzed by western blotting. The results indicated that PDJ treatment following LPS-stimulation decreased p-IκBα and p-p65 protein expression, whereas the expression of p65 and IκBα remained unchanged (Fig. 7). The results suggested that PDJ increased IκBα and p65 protein levels by dephosphorylating IκBα and p65 in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells.

Figure 7.

Effect of PDJ on LPS-induced protein expression of p-p65, p65, p-IκBα and IκBα. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with LPS (1 µg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and then subsequently treated with PDJ (0, 2.5 or 5 µg/ml) for at 37°C 24 h. β-actin was used as the loading control. (A) Western blot analysis and (B) the relative expression of p-p65/p65 and p-IκBα/IκBα ratios quantified by densitometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ##P<0.01 vs. untreated group; *P<0.05 vs. LPS-only treated group; **P<0.01 vs. LPS-only treated group; ***P<0.001 vs. LPS-only treated group. PDJ, polyphenolic extract from the Dowijigi flower; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; p, phosphorylated; IκBα, inhibitor of κBα.

Discussion

Plant extracts are attracting greater interest in anti-inflammatory drug discovery due to their low side effect profile and effective mode of action (27). Numerous varieties of phytoconstituents present in plants, including phenols, flavonoids and alkaloids, are responsible for the effective biological activities of plants, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-tumor, anti-bacterial and anti-viral effects (28). Compounds isolated from DJ exert pharmacological effects in a number of diseases and processes, including obesity, diabetes, fatty liver, inflammation and aging (23,29,30). However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have reported the inhibitory activities of PDJ on macrophage cells for the treatment of inflammation. The present study examined the anti-inflammatory effect of PDJ on LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells.

The polyphenolic content in the DJ flower extract was analyzed and identified by HPLC and MS/MS. The results of the MTT assay suggested that PDJ was not cytotoxic to RAW264.7 cells at concentrations ≤10 µg/ml. Therefore, 2.5 and 5 µg/ml PDJ were used for further experiments to examine the anti-inflammatory effects of PDJ.

Oxidative stress leads to an excessive accumulation of reactive oxygen species, such as NO and PGE2, in activated macrophages that has been observed in both acute and chronic inflammation in a number of disease conditions, including atherosclerosis, obesity and arthritis (31–33). Inhibition of NO production and PGE2 accumulation modulates the inflammatory response in macrophages, leading to the reduction of swelling and redness at the infection site (34,35). Therefore, the present study investigated NO and PGE2 production to determine whether PDJ could mediate the inflammatory response in RAW264.7 cells stimulated by LPS and co-treated with PDJ. The results suggested that PDJ effectively inhibited the production of NO and PGE2.

NO and PGE2 are produced from L-arginine and arachidonic acid metabolites of the proteins iNOS and COX2 (36). Thus, the mRNA and protein expression levels in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells were analyzed using RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. Pretreatment with LPS increased the mRNA and protein expression levels of iNOS and COX2, whereas the expression levels were significantly decreased in a concentration-dependent manner in cells co-treated with PDJ. Collectively, these data suggested that the suppressive effect of PDJ on NO and PGE2 production was a result of the inhibition of iNOS and COX2 expression, respectively.

Through synergetic interplay with the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6, iNOS and COX2 aggravate inflammation and the inflammatory response in pathological conditions (37, 38). The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6, by activated macrophages at the site of infection is an important target for anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies (15,19). Consistent with the RT-qPCR results, PDJ significantly downregulated the mRNA expression levels of TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6, suggesting that PDJ exerted anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of the pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The NF-κB signaling pathway is activated by the phosphorylation, ubiquitination and subsequent proteolytic degradation of NF-κB-bound IκB kinase proteins such as IκBα and p65, which in turn triggers the response of cytokine genes such as TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 in the nucleus. Moreover, the majority of anti-inflammatory drugs interrupt the inflammatory genes including TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 via activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (35,39). The expression of the NF-κB signaling pathway-related proteins IκBα and p65 in the present study suggested that treatment with PDJ inhibited the phosphorylated forms of p65 and IκBα, while the expression levels of the whole form of the proteins remained unchanged. The ratio of p-p65/p65 and p-IκBα/IκBα were elevated in the LPS-only treated group but were not elevated in the LPS group co-treated with PDJ, indicating that PDJ promoted phosphorylation of the p65 and IκBα proteins via the NF-κB signaling pathway to increase immune function in the RAW264.7 cells.

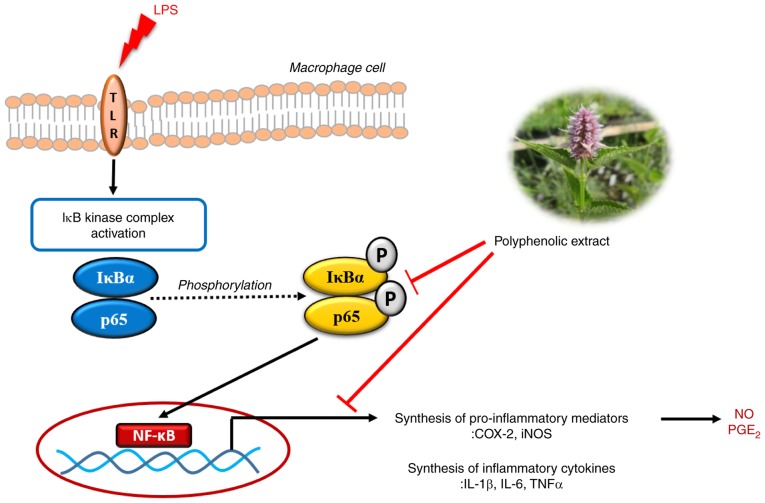

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested that PDJ exerted anti-inflammatory effects in RAW264.7 cells in vitro by suppressing NO and PGE2 production, and further displayed the inhibitory effects of PDJ on the inflammatory mediators iNOS and COX2 and the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory activity of PDJ might have occurred by direct inhibition of upstream kinases in the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, as summarized in Fig. 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the NF-κB-mediated inhibition of inflammatory responses by the polyphenolic extract of Dowijigi flower. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; TLR, Toll-like receptor; IκB, inhibitor of κB; IκBα, inhibitor of κBα; COX2, cyclooxygenase-2; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NO, nitric oxide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; p, phosphorylated.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported partly by The National Research Foundation of Korea funded by The Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (grant nos. 2012M3A9B8019303 and 2017R1A2B4003974).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SMK and PV designed the study, performed the experiments, organized focus group discussions, and collected and analyzed the data. HHK performed the extraction of polyphenols and performed the HPLC analysis. SEH and VVGS performed experiments and prepared the final manuscript. GSK participated in the focus group discussion and revised the study design, the results and the final manuscript for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wu C, Zhao W, Zhang X, Chen X. Neocryptotanshinone inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 macrophages by suppression of NF-κB and iNOS signaling pathways. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeong SG, Kim S, Kim HG, Kim E, Jeong D, Kim JH, Yang WS, Oh J, Sung GH, Hossain MA, et al. Mycetia cauliflora methanol extract exerts anti-inflammatory activity by directly targeting PDK1 in the NF-κB pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;231:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Araújo ERD, Félix-Silva J, Xavier-Santos JB, Fernandes JM, Guerra GCB, de Araújo AA, Araújo DFS, de Santis Ferreira L, da Silva Júnior AA, Fernandes-Pedrosa MF, Zucolotto SM. Local anti-inflammatory activity: Topical formulation containing Kalanchoe brasiliensis and Kalanchoe pinnata leaf aqueous extract. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;113:108721. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Lee K, Lee M, Ham I, Choi HY. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production by chloroform fraction of Cudrania tricuspidata in RAW 264.7 macrophages. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:250. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demoruelle MK, Deane KD, Holers VM. When and where does inflammation begin in rheumatoid arthritis? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:64–71. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16045. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo G, Cheng BC, Zhao H, Fu XQ, Xie R, Zhang SF, Pan SY, Zhang Y. Schisandra Chinensis Lignans suppresses the production of inflammatory mediators regulated by NF-κB, AP-1, and IRF3 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 Cells. Molecules. 2018;23 doi: 10.3390/molecules23123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, Li Y, Wang X, Zhao L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2017;9:7204–7218. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdulkhaleq LA, Assi MA, Abdullah R, Zamri-Saad M, Taufiq-Yap YH, Hezmee MNM. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet World. 2018;11:627–635. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2018.627-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng F, Lowell CA. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage activation and signal transduction in the absence of Src-family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1661–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchins AP, Takahashi Y, Miranda-Saavedra D. Genomic analysis of LPS-stimulated myeloid cells identifies a common pro-inflammatory response but divergent IL-10 anti-inflammatory responses. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9100. doi: 10.1038/srep09100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecilia OM, José Alberto CG, José NP, Ernesto Germán CM, Ana Karen LC, Luis Miguel RP, Ricardo Raúl RR, Adolfo Daniel RC. Oxidative stress as the main target in diabetic retinopathy pathophysiology. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:8562408. doi: 10.1155/2019/8562408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuo L, Prather ER, Stetskiv M, Garrison DE, Meade JR, Peace TI, Zhou T. Inflammaging and oxidative stress in human diseases: From molecular mechanisms to novel treatments. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20184472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayouf N, Charef N, Saoudi S, Baghiani A, Khennouf S, Arrar L. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of Asphodelus microcarpus methanolic extracts. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;239:111914. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.111914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han JM, Lee EK, Gong SY, Sohng JK, Kang YJ, Jung HJ. Sparassis crispa exerts anti-inflammatory activity via suppression of TLR-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophage cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;231:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah M, Ullah MA, Drouet S, Younas M, Tungmunnithum D, Giglioli-Guivarc'h N, Hano C, Abbasi BH. Interactive effects of light and melatonin on biosynthesis of silymarin and anti-inflammatory potential in callus cultures of Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. Molecules. 2019;24:1207. doi: 10.3390/molecules24071207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song C, Hong YH, Park JG, Kim HG, Jeong D, Oh J, Sung GH, Hossain MA, Taamalli A, Kim JH, et al. Suppression of Src and Syk in the NF-κB signaling pathway by Olea europaea methanol extract is leading to its anti-inflammatory effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;235:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han SY, Yi YS, Jeong SG, Hong YH, Choi KJ, Hossain MA, Hwang H, Rho HS, Lee J, Kim JH, Cho JY. Ethanol extract of Lilium bulbs plays an anti-inflammatory role by targeting the IKK[Formula: see text]/[Formula: see text]-mediated NF-[Formula: see text]B pathway in macrophages. Am J Chin Med. 2018;46:1281–1296. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X18500672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han B, Dai Y, Wu H, Zhang Y, Wan L, Zhao J, Liu Y, Xu S, Zhou L. Cimifugin inhibits inflammatory responses of RAW264.7 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:409–417. doi: 10.12659/MSM.912042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abad MJ, Bedoya LM, Apaza L, Bermejo P. The Artemisia L. genus: A review of bioactive essential oils. Molecules. 2012;17:2542–2566. doi: 10.3390/molecules17032542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Narayan VP, Hong EY, Whang WK, Park T. Artemisia iwayomogi extract attenuates high-fat diet-induced hypertriglyceridemia in mice: Potential involvement of the adiponectin-AMPK pathway and very low density lipoprotein assembly in the liver. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18081762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YK, Hong EY, Whang WK. Inhibitory effect of chemical constituents isolated from Artemisia iwayomogi on polyol pathway and simultaneous quantification of major bioactive compounds. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:7375615. doi: 10.1155/2017/7375615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandhiutami NM, Moordiani M, Laksmitawati DR, Fauziah N, Maesaroh M, Widowati W. In vitro assesment of anti-inflammatory activities of coumarin and Indonesian cassia extract in RAW264.7 murine macrophage cell line. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2017;20:99–106. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2017.8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erbel C, Rupp G, Helmes CM, Tyka M, Linden F, Doesch AO, Katus HA, Gleissner CA. An in vitro model to study heterogeneity of human macrophage differentiation and polarization. J Vis Exp. 2013:e50332. doi: 10.3791/50332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan SY, Zhou SF, Gao SH, Yu ZL, Zhang SF, Tang MK, Sun JN, Ma DL, Han YF, Fong WF, Ko KM. New perspectives on how to discover drugs from herbal medicines: CAM's outstanding contribution to modern therapeutics. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:627375. doi: 10.1155/2013/627375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maione F, Russo R, Khan H, Mascolo N. Medicinal plants with anti-inflammatory activities. Nat Prod Res. 2016;30:1343–1352. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1062761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu HH, Kim YH, Kil BS, Kim KJ, Jeong SI, You YO. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil of Artemisia iwayomogi. Planta Med. 2003;69:1159–1162. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-818011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park WS, Son YK, Ko EA, Choi SW, Kim N, Choi TH, Youn HJ, Jo SH, Hong DH, Han J. A carbohydrate fraction, AIP1, from Artemisia iwayomogi reduces the action potential duration by activation of rapidly activating delayed rectifier K channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;14:119–125. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.3.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abramson SB. Nitric oxide in inflammation and pain associated with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/ar2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li T, Liu B, Guan H, Mao W, Wang L, Zhang C, Hai L, Liu K, Cao J. PGE2 increases inflammatory damage in Escherichia coli-infected bovine endometrial tissue in vitro via the EP4-PKA signaling pathway. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:175–186. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ezzat SM, Raslan M, Salama MM, Menze ET, El Hawary SS. In vivo anti-inflammatory activity and UPLC-MS/MS profiling of the peels and pulps of Cucumis melo var. cantalupensis and Cucumis melo var. reticulatus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;237:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park SB, Park GH, Kim HN, Son HJ, Song HM, Kim HS, Jeong HJ, Jeong JB. Anti-inflammatory effect of the extracts from the branch of Taxillus yadoriki being parasitic in Neolitsea sericea in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;104:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong GE, Kim JA, Nagappan A, Yumnam S, Lee HJ, Kim EH, Lee WS, Shin SC, Park HS, Kim GS. Flavonoids identified from Korean Scutellaria baicalensis georgi inhibit inflammatory signaling by suppressing activation of NF-κB and MAPK in RAW 264.7 cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:912031. doi: 10.1155/2013/912031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herencia F, Ferrándiz ML, Ubeda A, Guillén I, Dominguez JN, Charris JE, Lobo GM, Alcaraz MJ. Novel anti-inflammatory chalcone derivatives inhibit the induction of nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in mouse peritoneal macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:129–134. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00707-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muniandy K, Gothai S, Badran KMH, Suresh Kumar S, Esa NM, Arulselvan P. Suppression of proinflammatory cytokines and mediators in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages by stem extract of Alternanthera sessilis via the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:3430684. doi: 10.1155/2018/3430684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojdasiewicz P, Poniatowski ŁA, Szukiewicz D. The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:561459. doi: 10.1155/2014/561459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tzeng HE, Tsai CH, Ho TY, Hsieh CT, Chou SC, Lee YJ, Tsay GJ, Huang PH, Wu YY. Radix Paeoniae Rubra stimulates osteoclast differentiation by activation of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18:132. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandes A, Sousa A, Mateus N, Cabral M, de Freitas V. Analysis of phenolic compounds in cork from Quercus suber L. by HPLC-DAD/ESI-MS. Food Chem. 2011;125:1398–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Rio D, Stewart AJ, Mullen W, Burns J, Lean ME, Brighenti F, Crozier A. HPLC-MSn analysis of phenolic compounds and purine alkaloids in green and black tea. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:2807–2815. doi: 10.1021/jf0354848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasain JK, Peng N, Dai Y, Moore R, Arabshahi A, Wilson L, Barnes S, Michael Wyss J, Kim H, Watts RL. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry identification of proanthocyanidins in rat plasma after oral administration of grape seed extract. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardana C, Scaglianti M, Pietta P, Simonetti P. Analysis of the polyphenolic fraction of propolis from different sources by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;45:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han B, Xin Z, Ma S, Liu W, Zhang B, Ran L, Yi L, Ren D. Comprehensive characterization and identification of antioxidants in Folium Artemisiae Argyi using high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2017;1063:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barros L, Dueñas M, Carvalho AM, Ferreira IC, Santos-Buelga C. Characterization of phenolic compounds in flowers of wild medicinal plants from Northeastern Portugal. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:1576–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li F, Zhang YB, Wei X, Song CH, Qiao MQ, Zhang HY. Metabolic profiling of Shu-Yu capsule in rat serum based on metabolic fingerprinting analysis using HPLC-ESI-MSn. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:4191–4204. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olennikov DN, Chirikova NK, Kashchenko NI, Nikolaev VM, Kim SW, Vennos C. Bioactive phenolics of the genus Artemisia (Asteraceae): HPLC-DAD-ESI-TQ-MS/MS profile of the Siberian species and their inhibitory potential against α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:756. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pati S, Losito I, Gambacorta G, La Notte E, Palmisano F, Zambonin PG. Simultaneous separation and identification of oligomeric procyanidins and anthocyanin-derived pigments in raw red wine by HPLC-UV-ESI-MSn. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:861–871. doi: 10.1002/jms.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schütz K, Kammerer DR, Carle R, Schieber A. Characterization of phenolic acids and flavonoids in dandelion (Taraxacum officinale WEB. ex WIGG.) root and herb by high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:179–186. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han J, Ye M, Qiao X, Xu M, Wang BR, Guo DA. Characterization of phenolic compounds in the Chinese herbal drug Artemisia annua by liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2008;47:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orčić D, Francišković M, Bekvalac K, Svirčev E, Beara I, Lesjak M, Mimica-Dukić N. Quantitative determination of plant phenolics in Urtica dioica extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Food Chem. 2014;143:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ye M, Yang WZ, Liu KD, Qiao X, Li BJ, Cheng J, Feng J, Guo DA, Zhao YY. Characterization of flavonoids in Millettia nitida var. hirsutissima by HPLC/DAD/ESI-MS n. J Pharm Anal. 2012;2:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.