Abstract

Introduction

Postoperative ileus occurs frequently following abdominal surgery. Identification of groups at high risk of developing ileus before surgery may allow targeted interventions. This review aimed to identify baseline risk factors for ileus.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted with reference to PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines. It was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017068697). Searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL were undertaken. Studies reporting baseline risk factors for the development of postoperative ileus based on cohort or trial data and published in English were eligible for inclusion. Dual screening of abstracts and full texts was undertaken. Independent dual extraction was performed. Bias assessment was undertaken using the quality in prognostic studies tool. Meta-analysis using a random effects model was undertaken where two or more studies assessed the same variable.

Findings

Searches identified 2,430 papers, of which 28 were included in qualitative analysis and 12 in quantitative analysis. Definitions and incidence of ileus varied between studies. No consistent significant effect was found for association between prior abdominal surgery, age, body mass index, medical comorbidities or smoking status. Male sex was associated with ileus on meta-analysis (odds ratio 1.12, 95% confidence interval 1.02–1.23), although this may reflect unmeasured factors. The literature shows inconsistent effects of baseline factors on the development of postoperative ileus. A large cohort study using consistent definitions of ileus and factors should be undertaken.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal surgery, Ileus, Prognosis

Introduction

Postoperative ileus remains a challenging and frustrating clinical problem for clinicians and patients alike. Prolonged postoperative ileus occurs in up to one in eight patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery,1 and results in patient discomfort, prolonged hospital stay. It is associated with increased postoperative complications.2 It is unsurprising, therefore, that a 2017 patient and public consultation study reported prevention of postoperative ileus as an important and unanswered issue.3

The causes of postoperative ileus are likely to be multifactorial,4 with risk factors for the development of prolonged postoperative ileus conceptually divided into patient and operative factors.5 Studies that have attempted to both elucidate the risk factors or strategies to reduce postoperative ileus have been hampered by lack of consistent definitions of what actually it constitutes and when transient it becomes prolonged.1

Several clinical intervention studies have sought to reduce the incidence of postoperative ileus. Agents such as steroids,6 opioid agonists7 and intravenous lidocaine8 have all been investigated. However, studies assessing such novel agents are hampered by the absence of clear and robust definitions and a consensus-derived core outcome set.9 Development of a validated gastrointestinal recovery score would greatly aid this endeavour. To achieve this, the relevance and effect of preoperative and operative risk factors for development of postoperative ileus, outcome variables, interventions and natural history of ileus requires further investigation.

The UK Medical Research Council-funded PROGnosis RESearch Strategy (PROGESS) initiative aims to develop multidisciplinary and collaborative research into improving research into quality of care outcomes such as postoperative ileus.10 Thus, identification of risk factors and development of a gastrointestinal recovery score to better assess strategies to reduce postoperative ileus would fit within two of the remits of this initiative ‘prognostic factor research’ and ‘prognostic model research’.

The aim of this review was to identify preoperative factors associated with the development of postoperative ileus as part of a larger collaborative effort overseen by the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) to develop a gastrointestinal recovery score.

Methods

This review was undertaken with reference to the Cochrane Handbook, reported meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses guidelines.11–13 The review was registered at the outset on PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42017068697).

Our primary aim was to derive a list of candidate risk factors for postoperative ileus following gastrointestinal surgery through systematic review of published literature. The secondary aim was to perform a meta-analysis of candidate risk factors to examine the significance and magnitude of effect on the risks for postoperative ileus.

We undertook a systematic review of MEDLINE (via OvidSP), EMBASE (via OvidSP) and Cochrane Library databases according to a predefined protocol up to May 2017. The search strategy is presented in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies assessing baseline (preoperative) factors and their association with development of postoperative ileus following gastrointestinal surgery in adults were eligible for inclusion. In order to review literature as widely as possible, the definition of postoperative ileus was accepted as defined by authors of individual studies rather than being set by the research team. There was no time limit placed on date of publication, and only studies written in the English language were included. Retrospective and prospective cohort or case–control studies, together with randomised controlled trials, were eligible for inclusion in the review. Owing to the risk of bias, case series, case reports, commentaries and editorials were excluded.

Data extraction

Article titles and abstracts were exported into Covidence, an established online screening and data extraction tool (www.covidence.org) screened for eligibility independently by two authors (PVS and/or ML and/or DV) with disagreements resolved by discussion. Review of the full text was undertaken by two authors for each candidate article. Bibliographies of included studies were hand searched to identify further relevant primary studies. Two authors independently extracted information from each primary studies using a standardised Microsoft Excel proforma. Data on study design and size, surgical approach (laparoscopic or open), background disease (eg cancer, inflammatory bowel disease) and definition of postoperative ileus were collected. Data on all reported characteristics were collected, including non-modifiable patient characteristics (eg gender, age) modifiable patient characteristics (eg smoking status), physiology characteristics (eg white cell count) and disease characteristics (eg indication for surgery).

Bias assessment

The methodological quality of all studies included in the systematic review was performed using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) tool.14 Two authors independently applied the QUIPS tool to each study to generate summary quality judgement with the bias assessment considered in the evaluation of the strength of findings. Funnel plots and visual tests of asymmetry were used to assess the risk of publication bias.

Statistical analysis

Studies that reported odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were considered for meta-analysis. This was selected as many studies reported OR from logistic regression, but no underlying data. A meta-analysis was performed if two or more studies reported a risk factor in this way. Meta-analysis used inverse variance and random effects included in the final synthesis were pooled using meta-analysis to construct relative risk estimates and presented using forest plots.

Results

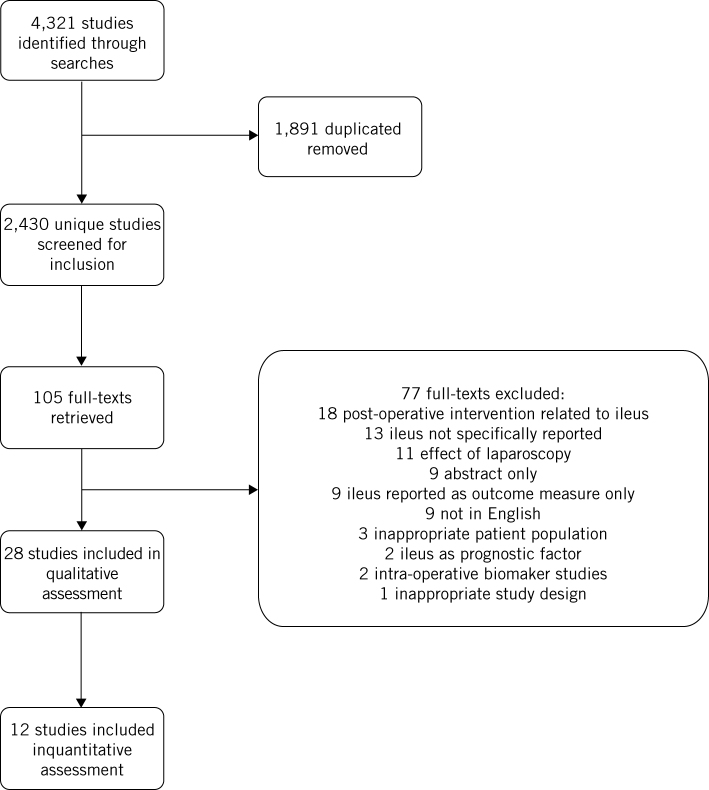

Initial searches identified 2,430 unique papers. Following screening, 105 papers were retrieved for full-text analysis. Following assessment, 28 papers were included in the qualitative analysis and 12 were included in quantitative analysis. This is summarised in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig 1). These papers reported assessments of 57,767 patients, of whom 6,127 developed postoperative ileus. This included 6 prospective cohort studies and 21 retrospective cohort studies. Study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| Study | Study design | Surgical population | Operative approach | Patients (n) | Rate of POI (%) |

| Akiyoshi et al (2011)33 | Prospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 1,194 | 1.08 |

| Artinyan et al (2008)4 | Retrospective cohort | Abdominal surgery | Open | 88 | 100 |

| Bakker et al (2015)45 | Prospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 816 | 11.64 |

| Barletta et al (2011)15 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 279 | 8.60 |

| Bickenbach et al (2013)35 | Retrospective cohort | Gastric cancer resection | Not reported | 1,853 | 8.60 |

| Bisanz et al (2008)16 | Retrospective cohort | Abdominal surgery | Not reported | 101 | 43.56 |

| Chapuis et al (2013)5 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 2,400 | 14.00 |

| Englesbe et al (2010)46 | Prospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 1,553 | 5.34 |

| Franko et al (2006)31 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 820 | 4.52 |

| Grosso et al (2012)26 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 446 | 5.38 |

| Hamel et al (2000)30 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 85 | 17.64 |

| Huang et al (2015)27 | Prospective cohort | Gastric cancer resection | Mixed | 296 | 32.43 |

| Ichikawa et al (2016)47 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 172 | 2.91 |

| Juarez-Parra et al (2015)17 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 95 | 21.11 |

| Kim et al (2013)28 | Retrospective cohort | Gastric cancer resection | Laparoscopic | 389 | 1.80 |

| Kronberg et al (2011)25 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 413 | 10.17 |

| Le et al (2011)21 | Retrospective cohort | Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis | Open | 91 | 21.98 |

| Millan et al (2012)29 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 773 | 15.91 |

| Moghadamyeghaneh et al (2016)22 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 27,560 | 12.69 |

| Murphy et al (2016)23 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 9,734 | 14.01 |

| Petros et al (1995)18 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Open | 358 | 16.20 |

| Pikarsky et al (2002)34 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 162 | 12.34 |

| Tian et al (2017)19 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 5,533 | 7.95 |

| Valenti et al (2007)48 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Open | 273 | 9.15 |

| Vather et al (2013)20 | Prospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 255 | 19.61 |

| Vather et al (2015)24 | Prospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Mixed | 327 | 26.91 |

| Yamamoto et al (2013)32 | Retrospective cohort | Colorectal resection | Laparoscopic | 1,701 | 2.70 |

POI, postoperative ileus.

Bias assessment

The QUIPS tool found concerns around outcome measurements (ie the definition of ileus). It also identified a high risk of bias associated with statistical analysis, as many small studies reported univariate assessments, without adjustment for other factors. A summary of bias assessment is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bias assessment using quality in prognostic studies tool.

| Study | Participation | Attrition | Prognostic factor measurement | Outcome measurement | Confounding | Statistical analysis and reporting |

| Akiyoshi et al (2011)33 | L | L | L | H | M | M |

| Artinyan et al (2008)4 | H | M | M | M | H | M |

| Bakker et al (2015)45 | L | L | L | M | M | H |

| Barletta et al (2011)15 | L | L | L | L | M | M |

| Bickenbach et al (2013)35 | H | L | L | H | H | H |

| Bisanz et al (2008)16 | L | L | L | M | H | M |

| Chapuis et al (2013)5 | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Englesbe et al (2010)46 | M | M | M | M | H | H |

| Franko et al (2006)31 | L | L | L | L | M | M |

| Grosso et al (2012)26 | L | L | L | M | M | H |

| Hamel et al (2000)30 | L | L | L | M | M | H |

| Huang et al (2015)27 | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Ichikawa et al (2016)47 | M | L | M | H | H | H |

| Juarez-Parra et al (2015)17 | M | L | L | M | M | H |

| Kim et al (2013)28 | M | L | L | M | M | H |

| Kronberg et al (2011)25 | L | L | M | H | H | M |

| Le et al (2011)21 | L | L | L | M | M | H |

| Millan et al (2012)29 | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Moghadamyeghaneh et al (2016)22 | L | L | M | M | L | L |

| Murphy et al (2016)23 | M | L | M | M | L | L |

| Petros et al (1995)18 | L | L | L | L | M | M |

| Pikarsky et al (2002)34 | H | M | L | L | M | H |

| Tian et al (2017)19 | L | L | L | M | M | L |

| Valenti et al (2007)48 | L | L | L | M | L | L |

| Vather et al (2013)20 | M | M | L | H | M | M |

| Vather et al (2015)24 | L | M | L | L | L | L |

| Yamamoto et al (2013)32 | L | L | L | H | H | H |

H, high risk of bias; L, low risk of bias; M, medium risk of bias.

Definition of postoperative ileus

Postoperative ileus was defined in all studies. This was typically a compound definition including aspects of tolerance of diet, absence of distention, passage of stool or flatus. The definitions of postoperative ileus used are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Definitions of postoperative ileus used in studies.

| Study | Definition of postoperative ileus |

| Akiyoshi et al (2011)33 | ‘Persistent ileus’ – not otherwise defined. |

| Artinyan et al (2008)4 | Patient’s ability to tolerate a solid diet in the absence of nausea, vomiting or abdominal distention. |

| Bakker et al (2015)45 | Prolonged inability to pass flatus and stool resulting in nausea and vomiting and requiring the use of a nasogastric tube and/or total parenteral nutrition. |

| Barletta et al (2011)15 | Three episodes of vomiting over 24 hours, cessation of oral diet or the need for a nasogastric tube within 5 days after surgery. |

| Bickenbach et al (2013)35 | Not defined. |

| Bisanz et al (2008)16 | Lack of return of bowel function; no passage of flatus; unable to tolerate oral intake; abdominal distention, nausea and vomiting, and absence of bowel movement by postoperative day 3. |

| Chapuis et al (2013)5 | Presence of abdominal distension with lack of bowel sounds in a patient who has experienced nausea or vomiting and has failed to pass flatus or stool for more than 3 days postoperatively, in the absence of mechanical bowel obstruction. |

| Englesbe et al (2010)46 | An ileus lasting more than 7 days from the index operation. |

| Franko et al (2006)31 | Ileus defined as the inability to tolerate any diet combined with abdominal distension beyond the third postoperative day. |

| Grosso et al (2012)26 | Not defined. |

| Hamel et al (2000)30 | Any placement of a nasogastric tube during the initial hospitalisation; the criterion was vomiting 200ml or more, two or more times. |

| Huang et al (2015)27 | Two or more of the following five criteria met on or after postoperative day 4 without prior resolution of ‘postoperative ileus’: nausea or vomiting, inability to tolerate oral diet over 24 hours, absence of flatus over 24 hours, abdominal distension and radiological confirmation of ileus. |

| Ichikawa et al (2016)47 | Not defined. |

| Juarez-Parra et al (2015)17 | The absence of passage of flatus/stool or inability to tolerate oral diet on or after four postoperative days. |

| Kim et al (2013)28 | Absence of adequate bowel function on postoperative day 5 or the need for insertion of a nasogastric tube in the absence of a mechanical obstruction. |

| Kronberg et al (2011)25 | Not defined. |

| Le et al (2011)21 | Any transient cessation of coordinated bowel motility following surgery that prevented the effective transit of intestinal contents or tolerance of oral intake within 7 days of surgery. |

| Millan et al (2012)29 | No bowel recovery at postoperative day 6. |

| Moghadamyeghaneh et al (2016)22 | No return of bowel function within 7 days. |

| Murphy et al (2016)23 | Nasogastric tube or nil by mouth on postoperative day 4 or later. |

| Petros et al (1995)18 | Passage of flatus or stool, or the ability to tolerate a clear liquid diet, were regarded as evidence of the resolution of postoperative ileus. Postoperative ileus ≥ 7 days. |

| Pikarsky et al (2002)34 | Ileus defined as a condition requiring reinsertion of a nasogastric tube due to two or more episodes of emesis of more than 200ml. |

| Tian et al (2017)19 | ICD-10 diagnostic code K56. Abdominal plain x-ray and computed tomography, and the presence of clinical manifestations including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and/or delay in the passage of flatus and stool for more than 7 days postoperatively, in the absence of mechanical bowel obstruction. |

| Valenti et al (2007)48 | Continued nasogastric tube on the fifth postoperative day or reintroduction of the tube |

| Vather et al (2013)20 | Prolonged postoperative ileus was recorded as occurring if this was clinically diagnosed and documented by the overseeing surgical team. |

| Vather et al (2015)24 | Prolonged postoperative ileus was defined as occurring if patients met two of the following five criteria on or after postoperative day 4: nausea or vomiting over the preceding 12 hours, inability to tolerate a solid or semisolid oral diet over the preceding two meal times, abdominal distension, absence of flatus and stool over the preceding 24 hours. |

| Yamamoto et al (2013)32 | Not defined. |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision.

Demographic characteristics associated with postoperative ileus

Twelve studies assessed sex for association with postoperative ileus. Seven studies found no significant relationship between sex and postoperative ileus,4,15–20 and a further five found a positive association with male sex.5,21–24 It should be noted that those finding a significant association tended to be larger studies which used multivariate regression methods. Nine studies assessed age for association with postoperative ileus. Three studies found that increasing age had no association with increased rates of postoperative ileus.15,16,25 Three studies found an association between postoperative ileus and increasing age when a cut-off point at 65 years26,27 or 70 years28 was used within univariate analyses. Three studies using multivariate analysis found increasing age was significantly associated with increased rates of postoperative ileus.17,22,23 The association between prior abdominal surgery and postoperative ileus was assessed in eight studies. No relationship with postoperative ileus was seen in five studies,4,17,21,29,30 and a positive association was found in three studies.25,31,32 Again, positive relationships were typically seen in larger studies which used multivariate regression analysis.

Comorbidity characteristics associated with postoperative ileus

Reported studies tended to support respiratory disease or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as risk factors for postoperative ileus, with three studies supporting this21,22,29 and one disagreeing.17 The presence of cardiac disease or congestive heart failure were reported as having a significant positive association with postoperative ileus rates in two studies22,29 and no relationship in a large retrospective cohort.

Renal failure or dialysis were not found to be risk factors,22,23,29 while in a single study pre-existing constipation was significantly associated with postoperative ileus (odds ratio, OR, 3.67 95% confidence interval, CI, 1.40–9.67).22 Obesity was assessed in seven studies. Obesity had a positive association in two studies,33,34 but this was not replicated across other studies.16,27,29,33,35 Weight showed no relationship with postoperative ileus in two studies.15,16 Smoking was associated with increased rates of postoperative ileus in a retrospective study.23

Physiological factors

Increasing American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status was associated with postoperative ileus in two large studies. Milan et al reported an odds ratio for postoperative ileus of 1.6 for ASA II and 7.0 for ASA IV, albeit with large confidence intervals.29 Moghadamyeghaneh et al reported that the risk of developing postoperative ileus was increased for patients judged to be higher than ASA II (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.07–1.36).22 White cell count raised above 12 × 10mm3 was a risk factor in one small retrospective study,36 but this was not reflected in a large retrospective study using multivariate analyses.22

Meta-analysis

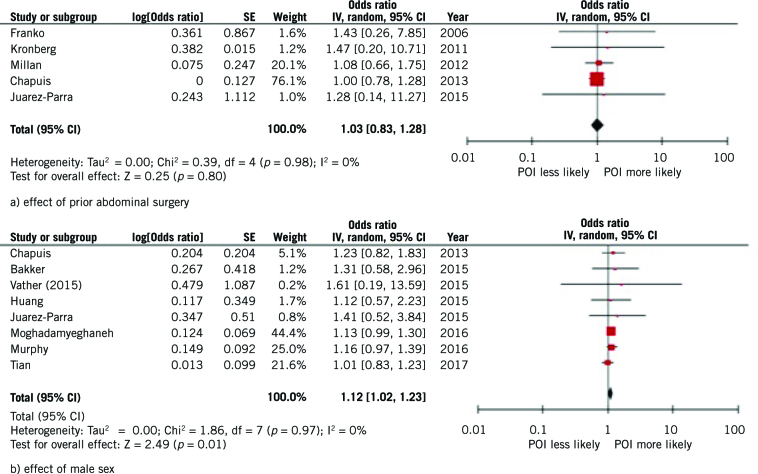

Meta-analysis was considered where two or more studies reported on association between the same factor and postoperative ileus. For age, the heterogeneity in factor classification and reported outcome measure precluded meta-analysis. Therefore only the demographic characteristics of male sex and prior abdominal surgery were assessed using meta-analysis. Data from five studies was pooled and showed a non-significant effect odds ratio (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.83–1.28, I2 = 0%; Fig 2a). Data from eight studies showed a significant positive association between male sex and development of postoperative ileus (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.23, p=0.01) with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%; Fig 2b).

Figure 2.

Meta-analyses of demographic factors on development of postoperative ileus (POI).

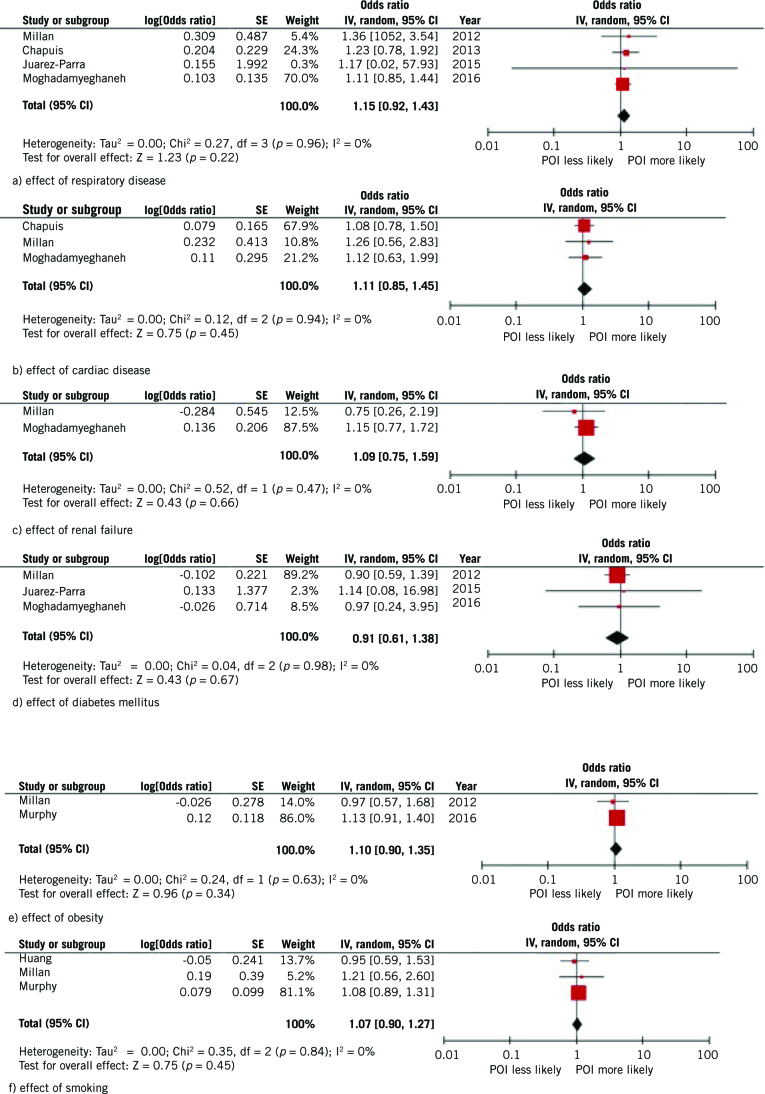

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of effect of comorbidities on development of postoperative ileus (POI).

Meta-analysis of comorbidity factors did not show significant effect of any factors, and demonstrated consistently low heterogeneity. Visual inspection of funnel plots did not demonstrate asymmetry.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review with meta-analysis to examine the relationship between baseline demographic or physiological factors and incidence of postoperative ileus in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Our review confirms significant heterogeneity in the definition of postoperative ileus used in clinical studies, which limits the synthesis of the published evidence. A total of 27 studies were included, with some evidence for an association between postoperative ileus and the factors age, male sex, prior abdominal surgery, obesity and pre-existing respiratory disease. However, meta-analysis of the synthesised evidence was limited by heterogeneity in factor and outcome classification, with a significant association seen for male sex only.

Postoperative ileus is a significant clinical problem. It is perhaps the most common complication following gastrointestinal surgery, occurring in up to one in eight patients, and remains poorly understood.1 There are two traditionally recognised phases of ileus: a short-acting neurogenic phase typified by exaggerated inhibitory reflexes triggered by activation of afferent nerves during the surgical procedure, and a longer inflammatory phase driven by immune mediators.37,38 Numerous intervention studies have sought to intervene in the physiology of postoperative ileus, yet the assessment of such studies is limited by both the lack of a standard definition of postoperative ileus and limited understanding of the contribution of baseline demographic and physiological factors.

To better assess strategies to reduce postoperative ileus, we believe that a consensus-derived gastrointestinal recovery score is needed alongside a better understanding of baseline risk factors, with the current study satisfying two remits of the Medical Research Council-funded PROGESS initiative: ‘prognostic factor research’ and ‘prognostic model research’.10 Regardless of the wide application of enhanced recovery programmes, identification of those at high risk of developing postoperative ileus is useful. Proper characterisation of this group could help to identify mechanistic processes underlying the development of postoperative ileus, eventually developing effective targeted treatments.

Some evidence for an association between postoperative ileus and the factors age, male sex, prior abdominal surgery, obesity and pre-existing respiratory disease is reported here and, as such, these variables should be collected and adjusted for in future studies of postoperative ileus. Male sex is associated with postoperative ileus in five studies and the only factor significantly associated with postoperative ileus on meta-analysis. The observed association may result from increased surgical duration and manipulation of the bowel, owing to increased visceral adiposity or a narrow male pelvis necessitating increased manipulation of bowel to complete an operation. Increasing age is associated with increased postoperative ileus in six studies, which could reflect previously reported delayed baseline colonic transit and increased sensitivity to anaesthetic or opiate analgesia.39 Obesity was associated with postoperative ileus in two studies assessed and may reflect increased surgical duration, a higher need for open surgery or increased perioperative anaesthetic or opiate requirement. Finally, three studies reported increased postoperative ileus in patients with baseline respiratory disease, which may reflect a tendency towards greater opiate use in such patients given the fear of postoperative respiratory complications.

Three additional studies that were published recently and therefore outside the years of our search criteria support a number of the above findings.40–42 Hain et al assessed risk factors for postoperative ileus in 428 patients undergoing rectal cancer surgery and reported independent significant associations with the baseline factors of male gender (OR 2.3) and age (OR 2.0). Postoperative ileus was also associated with conversion to open surgery and postoperative intra-abdominal infection, with a rate of 54% in patients with three or more of these risk factors.40 Wolthius et al reported a series of 523 patients undergoing colorectal resection, with male sex (OR 2.07) and previous abdominal surgery (OR 1.65) associated with postoperative ileus, and a trend towards increased postoperative ileus with increasing age and body mass index.1 Rybakov et al investigated postoperative ileus in 300 patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection, with positive independent associations seen with body mass index (OR 3.20) and previous abdominal surgery (OR 3.02), and a trend towards increased postoperative ileus in male patients.41 Finally, Sugawara reported a series of 841 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, of which around 70% were gastrointestinal surgical procedures, with male gender significantly associated with postoperative ileus, with a non-significant trend towards increased postoperative ileus with age, body mass index and respiratory disease.42 It is, however, probable that these studies have similar bias-related issues to those seen in the included studies, so the results should be interpreted with caution.

Limitations

There are some inherent limitations to the present analysis. Crucially, definition of ileus varied across the included studies, confirming findings of a previous systematic review.1,43 Some definitions may have been more sensitive that others, leading to wide variation in the incidence of postoperative ileus reported. This may impact upon the ability of statistical methods to ascertain the true effect size. Similarly, many studies conducted univariate analyses only, leaving findings open to critical bias. Similarly, the covariates used to adjust the analysis varied between studies and all studies included in the review were observational studies; hence, unmeasured confounding cannot be ruled out. The number of studies identified examining a single specific factor and postoperative ileus was generally small and this limits the power to detect significant associations. Finally, we recognise that ileus can occur after other surgical procedures, yet have specifically addressed ileus following gastrointestinal surgery to provide some homogeneity in an already heterogeneous field. Even with this relatively narrowed scope, there is significant variation in rates of ileus after different surgical procedures. Controlling for these rates might help to identify some of the underlying factors. The heterogeneity of conditions in this study may have led to a type II error.

Data from the contemporaneous Ileus Management International (IMAGINE) cohort,44 and the randomised trial ‘A placebo controlled randomised trial of intravenous lidocaine in accelerating gastrointestinal recovery after colorectal surgery’ (ALLEGRO) may provide additional information to guide risk stratification of patients. However, it is likely that a large prospective cohort study with robust definitions of postoperative ileus and risk factors will be required to answer this question accurately. Despite advances in other aspects of the art and science, the community seems to have made little progress in the prediction and mitigation of ileus. As a condition seen following most gastrointestinal surgery, this condition should be a focus for researchers and funders.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all attendees of the Gastrointestinal Recovery Research Day (28 April 2017; Royal College of Surgeons of England, London), supported by the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Delphi research programme and the Bowel Disease Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Wolthuis AM, Bislenghi G, Fieuws S et al. Incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 2016; : O1–O9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlet H, Holte K. Review of postoperative ileus. Am J Surg 2001; : 3S–10S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNair AG, Heywood N, Tiernan J et al. A national patient and public colorectal research agenda: integration of consumer perspectives in bowel disease through early consultation. Colorectal Dis 2017; : O75–O85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artinyan A, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Balasubramaniam S et al. Prolonged postoperative ileus: definition, risk factors, and predictors after surgery. World J Surg 2008; : 1,495–1,500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapuis PH, Bokey L, Keshava A et al. Risk factors for prolonged ileus after resection of colorectal cancer: an observational study of 2400 consecutive patients. Ann Surg 2013; : 909–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DREAMS Trial Collaborators and West Midlands Research Collaborative Dexamethasone versus standard treatment for postoperative nausea and vomiting in gastrointestinal surgery: randomised controlled trial (DREAMS Trial). BMJ 2017; : j1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady JT, Dosokey EM, Crawshaw BP et al. The use of alvimopan for postoperative ileus in small and large bowel resections. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; : 1,351–1,358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kranke P, Jokinen J, Pace NL et al. Continuous intravenous perioperative lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain and recovery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (7): CD009642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake TM, Ward AE. Pharmacological management to prevent ileus in major abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2016; : 1,253–1,264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: prognostic factor research. PLoS Med 2013; (2): e1001380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins J, Altman D, Sterne J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions London: : Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; : 2,008–2,012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; (7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL et al. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013; : 280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barletta JF, Asgeirsson T, Senagore AJ. Influence of intravenous opioid dose on postoperative ileus. Ann Pharmacother 2011; : 916–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisanz A, Palmer JL, Reddy S et al. Characterizing postoperative paralytic ileus as evidence for future research and clinical practice. Gastroenterol Nurs 2008; : 336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juarez-Parra MA, Carmona-Cantu J, Gonzalez-Can JR et al. Risk factors associated with prolonged postoperative ileus after elective colon resection. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2015; : 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petros JG, Realica R, Ahmad S et al. Patient-controlled analgesia and prolonged ileus after uncomplicated colectomy. Am J Surg 1995; : 371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tian Y Xu, B Yu G et al. Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index score as predictor of prolonged postoperative ileus in patients with colorectal cancer who underwent surgical resection. Oncotarget 2017; : 20,794–20,801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vather R, Trivedi S, Bissett I. Defining postoperative ileus: results of a systematic review and global survey. 2013; : 962–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Q, Liou D, Murrell Z, Fleshner P. Does a history of postoperative ileus predispose to recurrent ileus after multistage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis? Dis Colon Rectum 2011; : e114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Hwang GS, Hanna MH et al. Risk factors for prolonged ileus following colon surgery. Surg Endosc 2016; : 603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy M, Tevis S, Kennedy G. Independent risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus development. J Surg Res 2016; : 279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vather R, Josephson R, Jaung R et al. Development of a risk stratification system for the occurrence of prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a prospective risk factor analysis. Surgery 2015; : 764–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kronberg U, Kiran RP, Soliman MS et al. A characterization of factors determining postoperative ileus after laparoscopic colectomy enables the generation of a novel predictive score. Ann Surg 2011; : 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosso G, Biondi A, Marventano S et al. Major postoperative complications and survival for colon cancer elderly patients. BMC Surg 2012; (Suppl 1): S20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang DD, Zhuang CL, Wang SL et al. Prediction of prolonged postoperative ileus after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a scoring system obtained from a prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; : e2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MG, Kim HS, Kim BS, Kwon SJ. The impact of old age on surgical outcomes of totally laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 2013; : 3,990–3,997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millan M, Biondo S, Fraccalvieri D et al. Risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus after colorectal cancer surgery. World J Surg 2012; : 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamel CT, Pikarsky AJ, Weiss E et al. Do prior abdominal operations alter the outcome of laparoscopically assisted right hemicolectomy? Surg Endosc 2000; : 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franko J, O’Connell BG, Mehall JR et al. The influence of prior abdominal operations on conversion and complication rates in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. JSLS J. 2006; : 169–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto M, Okuda J, Tanaka K et al. Effect of previous abdominal surgery on outcomes following laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; : 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akiyoshi T, Ueno M, Fukunaga Y et al. Effect of body mass index on short-term outcomes of patients undergoing laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer: a single institution experience in Japan. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011; : 409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pikarsky AJ, Saida Y, Yamaguchi T et al. Is obesity a high-risk factor for laparoscopic colorectal surgery? Surg Endosc 2002; : 855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bickenbach KA, Denton B, Gonen M et al. Impact of obesity on perioperative complications and long-term survival of patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; : 780–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vather R, Bisset I. Risk factors for the development of prolonged post-operative ileus following elective colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013; : 1,385–1,391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman SJ, Pericleous A, Downey C, Jayne DG. Postoperative ileus following major colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2018; : 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stakenborg N, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Postoperative ileus: pathophysiology, current therapeutic approaches. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017; : 39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu CP, Tsai CH, Tsai CC et al. Postoperative ileus in the elderly. Int J Gerontol 2014; : 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hain E, Maggiori L, Mongin C et al. Risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus after laparoscopic sphincter-saving total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: an analysis of 428 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc 2018; : 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rybakov EG, Shelygin YA, Khomyakov EA, Zarodniuk IV. Risk factors for postoperative ileus after colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis 2018; : 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugawara, K, et al. Perioperative factors predicting prolonged postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2018; : 508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman SJ, Thorpe G, Vallance AE et al. Systematic review of definitions and outcome measures for return of bowel function after gastrointestinal surgery. BJS Open 2018; : 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapman SJ, Eurosurg Collaborative. Ileus Management International (IMAGINE): protocol for a multicentre, observational study of ileus after colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2018; : O17–O25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakker N, Cakir H, Doodeman HJ, Houdijk APJ. Eight years of experience with enhanced recovery after surgery in patients with colon cancer: impact of measures to improve adherence. Surgery 2015; : 1,130–1,136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Englesbe MJ, Brooks L, Kubus J et al. A statewide assessment of surgical site infection following colectomy: the role of oral antibiotics. Ann Surg 2010; : 514–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ichikawa N, Brooks L, Kubus J et al. Safety of laparoscopic colorectal resection in patients with severe comorbidities. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2016; : 503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Valenti V, Hernandez-Lizoain JL, Baixauli J et al. Analysis of early postoperative morbidity among patients with rectal cancer treated with and without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; : 1,744–1,751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]