Abstract

Background:

Bariatric surgery leads to sustained weight loss and resolution of obesity-associated comorbidities in severely obese adolescents. However, one consequence of massive weight loss is excess skin and soft tissue. Many details regarding the timing, outcomes, and barriers associated with body contouring surgery (BCS) in youth who have undergone bariatric surgery are unknown.

Methods:

Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS) is a prospective multi-institutional study of 242 adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery from 2007 to 2012. Utilization of BCS was analyzed in this population with comparison of anthropometrics and excess skin-related symptoms between those who did and those who did not undergo BCS.

Results:

Among the 198 study participants with BCS data available, 25 (12.6%) underwent 41 body contouring procedures after bariatric surgery. The most common BCS was panniculectomy (n=23). Presence of pannus-related symptoms at baseline and the magnitude of weight loss within the first year after bariatric surgery were independently associated with subsequent panniculectomy (p=0.04 and p=0.03, respectively). All adolescents who underwent panniculectomy experienced resolution of pannus-related symptoms. At five years after bariatric surgery, 74% of those who did not undergo panniculectomy reported an interest in the procedure and 58% indicated that cost/insurance coverage was the barrier to obtaining BCS.

Conclusion:

Few adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery later underwent BCS procedures. Panniculectomy effectively treated pannus-related symptoms. Disparities in access to surgical care for adolescents who desire BCS warrants further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the substantial health benefits of bariatric surgery, many consider the development of excess skin and soft tissue following massive weight loss an adverse consequence of bariatric procedures. In adults undergoing bariatric surgery, excess skin and soft tissue can impair mobility, exercise capacity, lead to intertriginous dermatitis and ulceration, and diminish quality of life (QOL) [1–4]. These symptoms often lead individuals to pursue body contouring surgery (BCS) after bariatric surgery [4]. While adolescents undergoing bariatric surgery achieve similar weight loss and health improvement compared to adults [5], they may be less susceptible to problems associated with excess skin and soft tissue than adults due to greater skin thickness and elasticity [6]. However, contrasting data suggest that some adolescents experience comparable dissatisfaction with excess skin and a similar desire for BCS as adults [7].

Since a majority of weight is lost within the first year following bariatric surgery [5, 8], BCS in adults is often deferred until eighteen months after bariatric surgery to assure weight stability. Applying this strategy, adults who undergo BCS after bariatric surgery experience enhanced body image, superior weight loss maintenance, and improved QOL [9–11]. Whether it is appropriate to apply adult principles to the management of excess skin and expect similar outcomes in adolescents is unclear, and this knowledge gap limits our ability to counsel adolescents regarding the potential benefits and preferred timing of BCS after bariatric surgery.

The primary objective of this study was to assess for predictors of body contouring utilization in an adolescent bariatric population. Secondary aims were to identify characteristics at the time of bariatric surgery that predict that an individual obtains BCS, to evaluate the effect of BCS on excess skin and soft tissue related symptoms and QOL, and to describe barriers to obtaining BCS.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS) is a prospective observational study that enrolled 242 adolescents (13–19 years of age) who underwent bariatric surgery in five centers across the United States between 2006 and 2012. Study protocol and data safety and monitoring plans were approved by the steering committee, each institutional review board, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) data and safety monitoring board. Study details are available at clinicaltrials.gov using the identifier [5].

Data Collection

Participants were evaluated pre-operatively and at 6-, 12-, 24-, 36-, 48-, and 60- months following bariatric surgery. At each post-operative visit, participants reported the presence or absence of six skin and soft-tissue related symptoms (intertriginous/fungal cutaneous infections, recurrent cellulitis, superficial cutaneous ulcerations, deep cutaneous ulcerations, necrotizing fasciitis, and lymphedema) and whether they underwent any BCS procedures since their prior visit. In addition, participants completed an Impact of Weight on Quality of Life (IWQOL) survey annually. At the 60-month visit, participants also completed an “Excessive Skin Survey” which included questions specific to body regions. This instrument was adapted from the Longitudinal Assessment after Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study and was originally developed and utilized as no valid/reliable instrument appropriate to ascertain excess skin related data was available.

Baseline demographics, anthropometrics, and skin and soft tissue symptoms were compared between adolescents who underwent BCS during the first five years after bariatric surgery and adolescents who did not. Abdominal pannus severity was objectively scored by a surgical investigator at each in-person visit. The scale that was used consisted of six categories: 0, no pannus; 1, pannus covers pubic hairline; 2, pannus covers genitals at the level of the upper thigh crease; 3, pannus covers upper thigh; 4, pannus covers mid-thigh; and 5, pannus covers knees [16]. A pictoral example of each category was provided to the investigators in the case report form to increase the harmonization and consistency in assessments over time and across sites.

Statistical Methods

Specific pannus symptoms at baseline were compared between BCS groups using unadjusted Fisher’s exact tests and exact logistic regression adjusting for covariates. Baseline characteristics and differences at one year were compared between groups using a two-sample t-test for continuous measures and either a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical measures. Change in severity of the abdominal pannus between the time of bariatric surgery and five years after bariatric surgery was compared using an ordinal logistic regression with generalized estimating equations assuming an exchangeable working correlation and combining pannus grades four and five due to small number. QOL measures over time were compared between BCS groups using linear mixed models with a spatial power error structure to account for serial correlation. QOL measures collected at visits before and after BCS were compared using a one-sample t-test. The p-value threshold for concluding statistical significance was defined at 0.05.

RESULTS

Incidence and Timing of Body Contouring Surgery

Among the 242 Teen-LABS participants, 198 (81.8%) completed the BCS survey instrument at 60 months and were included in the analysis. Of these 198 participants, 25 (12.6%) reported undergoing a total of 41 BCS procedures during the five years after bariatric surgery. Twenty-three (56%) of these BCS procedures were panniculectomies. The remaining eighteen BCS procedures were performed to address excess skin and soft tissue of the chest (n=6), arms (n=5), thighs (n=3), back (n=3), and buttock (n=1, Supplemental Table). The mean age at time of BCS was 19.1±1.7 years. Baseline demographics between those who did and those who did not undergo BCS were not significantly different with the exception of age; the group that ultimately underwent BCS was approximately one year younger at the time of bariatric surgery (p<0.01, Table 1).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| No Body Contouring Surgery (n=173) | Any Body Contouring Surgery (n=25) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 132 (76.3%) | 17 (68.0%) | 0.52 |

| Male | 41 (23.7%) | 8 (32.0%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 14 (8.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.22 |

| Non-Hispanic | 159 (91.9%) | 25 (100%) | |

| Race | |||

| African American | 38 (22.0%) | 5 (20.0%) | 1 |

| American Indian | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Multiple | 8 (4.6%) | 1 (4.0%) | |

| White | 126 (72.8%) | 19 (76.0%) | |

| Bariatric Surgery Procedure | |||

| Gastric bypass | 120 (69.4%) | 18 (72.0%) | 0.52 |

| Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band | 11 (6.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Vertical Sleeve gastrectomy | 42 (24.3%) | 7 (28.0%) | |

| Baseline Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.7 (1.56) | 15.5 (1.53) | <0.01 |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 52.3 (9.49) | 54.0 (8.96) | 0.40 |

| Baseline Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 148 (30.3) | 153 (32.3) | 0.45 |

Values for continuous measures represent mean (SD). Values for categorical measures represent n (%). No adolescent within the Body Contouring Surgery (BCS) group had undergone BCS by this timepoint. BMI, body mass index.

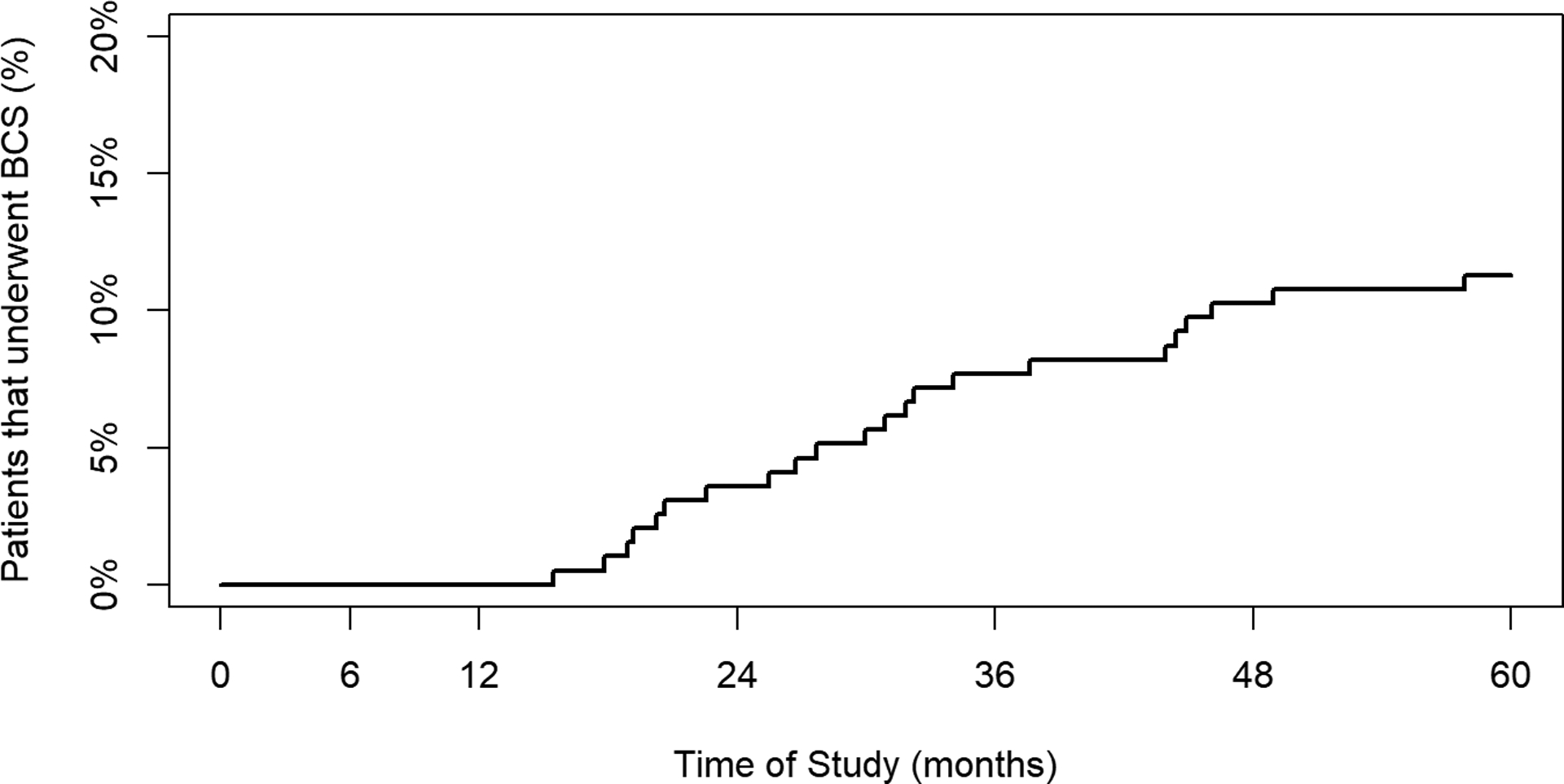

No adolescent reported undergoing BCS within a year of bariatric surgery, but by year two post-bariatric surgery, seven (3.5%) of the 198 adolescents reported undergoing BCS, eight (4.0%) more by year three, five (3.0%) more by year four, and two (1.0%) more by year five (Figure). Three additional adolescents reported undergoing a BCS on the body region form administered at their year five research visit, but the timing of BCS was unknown.

Figure: Timing of Body Contouring Surgery After Bariatric Surgery.

Among the 198 adolescents whose body contouring surgery status was known, 22 reported the exact timing of their operation, the cumulative results of which are represented in this Kaplan-Meyer graph. The y-axis scale ranges from zero to 20% in order for better visualization of the timing of surgery among those who underwent body contouring surgery. BCS, body contouring surgery.

Characteristics of Participants Undergoing Panniculectomy

To identify predictors of which adolescents would undergo panniculectomy following bariatric surgery, we compared the prevalence of abdomen-specific skin and soft tissue symptoms at before bariatric surgery between participants who subsequently underwent panniculectomy and those who did not. Baseline pannus symptoms were more common among adolescents who ultimately underwent panniculectomy (p=0.04, Table 2). After adjusting for sex, body mass index (BMI), and surgery type, we found that those who subsequently underwent panniculectomy were 3.4-fold more likely to have experienced pannus-related symptoms at baseline than those who did not undergo a panniculectomy (p=0.04, 95% C.I. = 1.1, 11.0). Although the baseline prevalence of intertriginous/fungal cutaneous infections and superficial cutaneous ulcerations was not significantly different between the two groups, recurrent cellulitis was more prevalent in the group that later underwent panniculectomy (13.6% versus 2.9%, p<0.05).

Table 2:

Anthropometric Associations with Subsequent Panniculectomy

| No Panniculectomy (n=175) | Panniculectomy (n=23) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline pannus symptoms present | 13 (7.4%) | 5 (22.7%) 1 | 0.04 |

| Percent weight change at 1 year | −28.9 (9.8) 13 | −32.4 (6.5) | 0.03 |

| Percent BMI change at 1 year | −29.1 (9.9) 14 | −32.6 (6.5) | 0.03 |

| Pannus grade change at 1 year | |||

| Increased | 23 (15.5%) 27 | 4 (18.2%) 1 | 0.91 |

| Remained the same | 45 (30.4%) | 6 (27.3%) | |

| Decreased | 80 (54.1%) | 12 (54.5%) |

Values represent number (%) or mean (SD). The number of missing values are provided as superscripts for each group. No adolescent within the panniculectomy group had undergone BCS by this timepoint. BMI, body mass index.

We also compared anthropometric measurements within the first year after bariatric surgery to determine if changes in these characteristics predicted whether an adolescent underwent subsequent panniculectomy. Baseline weight and BMI were not statistically different between adolescents who did and did not subsequently receive panniculectomy. However, at one-year post-bariatric surgery, prior to any BCS procedures, the group that later underwent panniculectomy had lost more weight with greater reduction in BMI (p=0.03) than those who did not undergo panniculectomy. We did not detect a relationship between change in pannus grade and future panniculectomy (Table 2).

Outcomes After Panniculectomy

We performed a longitudinal analysis comparing pannus severity over time between adolescents who did and did not undergo a panniculectomy. Among those who did not undergo panniculectomy, heterogeneous outcomes were observed: 14% experienced progression in pannus grade, 50% experienced improvement in pannus grade, and 26% remained the same. In contrast, among those who reported undergoing a panniculectomy, all had a reduction in their pannus grade except those who started with a pannus grade of zero. Even after accounting for time post-surgery, sex, surgery type, amount of weight lost, and baseline BMI, the odds of experiencing a decrease to a lower pannus grade were 6.1 times greater for those who underwent a panniculectomy (p<0.01, 95% CI = 2.6, 14.0).

To determine the effect of panniculectomy on excess skin and soft tissue problems, we compared prevalence of any pannus-related symptoms at baseline and at each study visit after bariatric surgery. While the frequency of pannus-related symptoms among those who did not undergo a panniculectomy increased from 7.2% (n=13) at baseline to 11.2% (n=19) at five years (p=0.30), no one who underwent a panniculectomy reported pannus-related symptoms following their panniculectomy.

Results of QOL analyses using the IWQOL instrument for total score, physical subscale, and body esteem subscale (reported at baseline and at each post-bariatric surgery visit) suggested there were no significant differences in mean weight related QOL scores over time between those who underwent any BCS compared to those who did not (p=0.65, p=0.69, p=0.68, respectively, regression results not presented; Supplemental Figure). In addition, when we compared pre- and post-BCS IWQOL among the 21 adolescents for whom data were available, we found no significant difference in each IWQOL metric (p>0.05 for each metric).

Barriers to Body Contouring Surgery

Among all 41 BCS procedures reported, 30 (73%) were covered by an insurance payor. Twenty (87%) of the 23 panniculectomies performed were covered by insurance benefits (Supplemental Table). The desire for BCS was body region specific with more than half of participants reporting a desire for BCS of the abdomen, arms, chest, and thighs. Less than half of participants reported a desire for BCS of the back, rear, and chin. Cost was the most frequently cited reason for not undergoing surgery (Table 3).

Table 3:

Reported Interest in Body Contouring Surgery

| Abdominal (n=147) | Arm (n=171) | Back (n=168) | Thigh (n=171) | Chest (n=172) | Rear (n=175) | Chin (n=178) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desire to obtain BCS | 109 (74.1%) | 114 (66.3%) | 72 (42.9%) | 109 (63.7%) | 89 (51.7%) | 59 (33.7%) | 37 (20.8%) |

| If BCS was desired, reasons for not obtaining BCS: | |||||||

| Cost | 63 (57.8%) | 70 (61.4%) | 39 (54.2%) | 64 (58.7%) | 54 (60.7%) | 35 (59.3%) | 14 (37.8%) |

| Not recommended | 6 (5.5%) | 6 (5.3%) | 3 (4.2%) | 7 (6.4%) | 4 (4.5%) | 5 (8.5%) | 4 (10.8%) |

| Planning to | 35 (32.1%) | 31 (27.2%) | 23 (31.9%) | 34 (31.2%) | 24 (27.0%) | 16 (27.1%) | 16 (43.2%) |

| Other | 5 (4.6%) | 7 (6.1%) | 7 (9.7%) | 4 (3.7%) | 7 (7.9%) | 3 (5.1%) | 3 (8.1%) |

Data reported from the excess skin survey five years after bariatric surgery. N=242 Teen-LABS participants minus individuals with missing or conflicting data and those who underwent body contouring surgery to the queried region. BCS, body contouring surgery.

DISCUSSION

Similar to adults who have lost significant weight after bariatric surgery, 13% of adolescents underwent BCS within five years of their weight loss procedure. Those who reported recurrent cellulitis at baseline and those who lost more weight within the first year after bariatric surgery were more likely to undergo BCS. Among adolescents who underwent BCS, all experienced resolution of pannus-related symptoms.

These findings are consistent with prior studies evaluating skin and soft tissue related issues in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery [7, 12]. In a smaller series of 49 adolescents who underwent bariatric surgery, Staalesen et al. reported that five participants (11%) underwent BCS within four years of bariatric surgery [7], consistent with our finding of 13%. An additional similarity between studies was the number of adolescents who desired but did not undergo BCS. While we found that the desire for BCS was site specific, with approximately 70% of adolescents desiring BCS for their pannus and arms, Staalesen et al. found that 88% of adolescents desired BCS but their analysis was not site specific [7].

With an 82% follow up rate, our findings substantially extend results from studies of skin and soft tissue related issues in adults undergoing bariatric surgery. Among the LABS cohort, Marek et al. found that 11% of adults underwent BCS within five years of bariatric surgery [12]. Collectively, these data call into question the commonly held belief that adolescents have a reduced need for BCS after surgery due to a greater likelihood of natural resolution of youthful excess skin following bariatric surgery.

While excess skin related issues, specifically recurrent dermatitis, have been reported to affect greater than 50% of individuals who undergo bariatric surgery [4], it is not clear whether BCS reduces frequency or severity of symptoms related to excess skin and soft tissue. In the present study we found that adolescents who suffered from excess-skin related issues at baseline were 3.4-fold more likely to undergo panniculectomy. We also found that adolescents who underwent panniculectomy experienced complete resolution of skin and soft-tissue symptoms, while there was a trend towards increase in prevalence of symptoms in adolescents who did not undergo panniculectomy. Thus, our findings provide clinicians with empirically derived criteria for which adolescents may require panniculectomy after bariatric surgery and the benefits of panniculectomy to these patients.

Many third-party payers consider BCS a cosmetic procedure and often limit or refuse coverage, which may explain the disparity between the number of patients seeking consultation by a plastic surgeon and number who actually undergo BCS [12]. In a recent report, Azin et al. found that 95% of adults desire BCS after bariatric surgery, but third-party payers denied coverage in half of these cases[17]. In a separate study of 33 adults who underwent BCS, abdominoplasty and breast lift were the only body contouring procedures covered by insurance (47% and 33% covered, respectively) [13], and for a majority of adults who underwent BCS after bariatric surgery, self-pay was required[12]. Contrasting these reports, among the 41 BCS cases reported in the Teen-LABS cohort, 73% were covered by third-party payers. However, we found that among our Teen-LABS participants who did not undergo BCS post-bariatric surgery, (a majority of the cohort), 74% were interested in undergoing panniculectomy at their five-year follow-up appointment, and 58% of these individuals reported cost/insurance coverage to be a limiting factor. Together, these observations suggest that excess skin and soft tissues are perceived as a significant problem among adolescents after bariatric surgery, but cost can be a significant barrier to obtaining surgical services.

There are several limitations inherent in this study design. Specifically, the subset of individuals who underwent BCS is small, limiting the power to detect differences that may exist between those who did and did not undergo BCS. Additionally, although the prospective data were collected using a combination of survey instruments, recall bias is possible due to the data collection only at annual study visits, particularly in the case of the one BCS instrument specific to body region, which was administered only at year five. Indeed, nine study participants reported more than one BCS procedure, all of whom underwent a panniculectomy, but did not specify the chronologic order, most likely due to difficulty in recall of the dates of procedure. For this analysis, we assumed that their panniculectomy occurred first, as all pannus-related symptoms resolved in these adolescents following their first BCS. As several studies have reported that BCS resulted in improved QOL [14, 18, 19], we explored this relationship within the Teen-LABS data. Unlike prior studies in post-bariatric surgery adults demonstrating improvement in QOL following BCS [17, 18, 20], we did not find a significant difference in weight related QOL between those adolescents who did and did not undergo BCS. Of note, we measured QOL using the impact of weight on quality of life instrument, and these questions were not designed to probe how the excess skin specifically affects quality of life. Lastly, this report does not provide a complete examination of BCS use after bariatric surgery as BCS likely continues beyond five years post-surgery, which would ultimately increase estimates of incidence of BCS.

In summary, from this series of individuals who underwent bariatric surgery as adolescents, we found that relatively few underwent subsequent BCS. However, for those who did, panniculectomy led to resolution of excess skin related symptoms providing compelling evidence for the effectiveness of BCS in patients with symptomatic disease. During follow up, health care providers should inquire about and document excess skin related concerns and refer to surgeons experienced in BCS for effective treatment of these conditions. Further studies are needed to address the disparity between those who desire BCS and those who actually obtain it.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES:

- [1].Baillot A, Asselin M, Comeau E, Meziat-Burdin A, Langlois MF. Impact of excess skin from massive weight loss on the practice of physical activity in women. Obes Surg 2013;23:1826–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Giordano S, Victorzon M, Koskivuo I, Suominen E. Physical discomfort due to redundant skin in post-bariatric surgery patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:950–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, Mitchell JE, Rubin JP. Psychological considerations of the bariatric surgery patient undergoing body contouring surgery. Plast Reconst Surg. 2008;121:423e–34e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kitzinger HB, Abayev S, Pittermann A, Karle B, Bohdjalian A, Langer FB, et al. After massive weight loss: patients’ expectations of body contouring surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22:544–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Inge TH, Courcoulas AP, Jenkins TM, Michalsky MP, Helmrath MA, Brandt ML, et al. Weight Loss and Health Status 3 Years after Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mora Huertas AC, Schmelzer CE, Hoehenwarter W, Heyroth F, Heinz A. Molecular-level insights into aging processes of skin elastin. Biochimie. 2016;128–129:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Staalesen T, Olbers T, Dahlgren J, Fagevik Olsen M, Flodmark CE, Marcus C, et al. Development of excess skin and request for body-contouring surgery in postbariatric adolescents. Plast Reconst Surg. 2014;134:627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, Berk PD, Flum DR, Garcia L, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. Jama. 2013;310:2416–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Balague N, Combescure C, Huber O, Pittet-Cuenod B, Modarressi A. Plastic surgery improves long-term weight control after bariatric surgery. Plast Reconst Surg. 2013;132:826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Toma T, Harling L, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Ashrafian H. Does Body Contouring After Bariatric Weight Loss Enhance Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of QOL Studies. Obes Surg 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wiser I, Avinoah E, Ziv O, Parnass AJ, Averbuch Sagie R, Heller L, et al. Body contouring surgery decreases long-term weight regain following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: A matched retrospective cohort study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Marek RJ, Steffen KJ, Flum DR, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Rubin JP, et al. Psychosocial functioning and quality of life in patients with loose redundant skin 4 to 5 years after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Ertelt TW, Marino JM, Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, et al. The desire for body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Monpellier VM, Antoniou EE, Mulkens S, Janssen IMC, Jansen ATM, Mink van der Molen AB. Body Contouring Surgery after Massive Weight Loss: excess skin, body satisfaction and qualification for reimbursement in a Dutch post-bariatric population. Plast Reconst Surg 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wagenblast AL, Laessoe L, Printzlau A. Self-reported problems and wishes for plastic surgery after bariatric surgery. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48:115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Igwe D Jr., Stanczyk M, Lee H, Felahy B, Tambi J, Fobi MA. Panniculectomy adjuvant to obesity surgery. Obes Surg. 2000;10:530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Azin A, Zhou C, Jackson T, Cassin S, Sockalingam S, Hawa R. Body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery: a study of cost as a barrier and impact on psychological well-being. Plast Reconst Surg. 2014;133:776e–82e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gilmartin J, Bath-Hextall F, Maclean J, Stanton W, Soldin M. Quality of life among adults following bariatric and body contouring surgery: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:240–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Alderman A, Soldin M, Thoma A, Robson S, et al. The BODY-Q: A Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Weight Loss and Body Contouring Treatments. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hearnshaw C, Matyka K. Managing childhood obesity: when lifestyle change is not enough. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:947–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.