Summary

Background

MSB11022 is a proposed adalimumab biosimilar.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of MSB11022 with reference adalimumab.

Methods

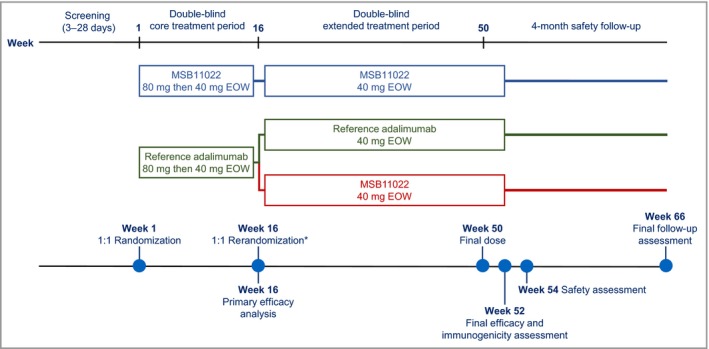

AURIEL‐PsO was a double‐blind randomized controlled equivalence trial, in which patients with moderate‐to‐severe chronic plaque‐type psoriasis were randomized 1 : 1 to MSB11022 or reference adalimumab. The primary end point was ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) at week 16, with a prespecified equivalence interval of ± 18%. Patients with a ≥50% improvement in PASI at week 16 were eligible to enter a double‐blind extension period: patients receiving MSB11022 continued treatment, and patients receiving reference adalimumab were rerandomized 1 : 1 either to continue reference adalimumab or to switch to MSB11022. Other efficacy end points and safety, immunogenicity and pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated at scheduled visits up to weeks 52 (efficacy and immunogenicity), 54 and 66 (safety).

Results

In total, 443 patients were randomized. The difference in PASI 75 response rates at week 16 between the treatment arms was −1·9%, and the 95% confidence interval (−7·8% to 4·1%) was within the prespecified equivalence interval. No notable difference in the incidence of treatment‐emergent adverse events was observed between treatment arms up to the end of the trial, and no new safety signals were observed. Following treatment switch at week 16, no clinically meaningful differences in safety or immunogenicity were seen between treatment arms through to the end of the observation period.

Conclusions

Therapeutic equivalence between MSB11022 and reference adalimumab was demonstrated. AURIEL‐PsO provides evidence to support the similarity of both products with regard to efficacy, safety and immunogenicity.

What's already known about this topic?

Adalimumab is a fully human antitumour necrosis factor‐α monoclonal antibody, indicated for the treatment of multiple inflammatory disorders, including psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases and ankylosing spondylitis.

MSB11022 is a proposed adalimumab biosimilar that has shown structural and functional similarity to the reference product in an extensive analytical comparability exercise.

MSB11022 has demonstrated bioequivalence and comparable safety and immunogenicity profiles in a phase I study in healthy volunteers.

What does this study add?

This phase III study confirmed equivalent efficacy for MSB11022 and reference adalimumab in patients without any immunomodulation comedication in moderate‐to‐severe chronic plaque‐type psoriasis at week 16.

The efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab were similar over the respective observation periods (week 52 for efficacy and immunogenicity, week 66 for safety).

A switch from reference adalimumab to MSB11022 at week 16 did not impact efficacy, safety or immunogenicity.

Short abstract

Linked Comment: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.18717.

Therapies targeting tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α have been shown to provide significant clinical benefits to patients with immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases.1 Adalimumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds TNF‐α with high affinity and specificity.2 It is successfully used in clinical practice for the treatment of various chronic inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases and ankylosing spondylitis.3

Due to the high acquisition costs of biologics, strict reimbursement criteria are implemented in many countries, meaning that patients may not have access to biologics even if they meet the eligibility criteria recommended in national and international guidelines.4, 5 However, as patents for biologics expire, the introduction of biosimilars will contribute to reducing drug costs and improving access to biologics.6 Biosimilars are biological medicines highly similar in all essential aspects to a reference biological medicine already authorized.7, 8, 9, 10

Regulatory approval of biosimilars requires evidence that the molecule is similar to the reference product in terms of structure, function, clinical efficacy and safety.7, 8, 9, 11 MSB11022 (Idacio®) is a proposed adalimumab biosimilar that has been shown to be structurally and functionally similar to reference adalimumab based on extensive analytical characterization.12 The pharmacokinetic bioequivalence of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab (both European Union and U.S.A. approved versions) has been shown in a phase I study.13 Here we report results from the phase III AURIEL‐PsO study, which was conducted to demonstrate equivalence in efficacy at week 16 and to compare the safety, immunogenicity and impact on quality of life (QoL) of MSB11022 with those of reference adalimumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe chronic plaque psoriasis.

As recommended by the European Medicines Agency, an equivalence study design was used in this study.11 The impact of switching from reference adalimumab to MSB11022 and the effect of longer‐term treatment were also evaluated through a single treatment switch at week 16 and an extended double‐blind treatment period up to week 52, with a 4‐month safety follow‐up period.

Patients and methods

AURIEL‐PsO was a multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, parallel‐group trial conducted from 16 February 2016 to 18 December 2017, with patients enrolled across 69 centres in North America, South America and Europe (NCT02660580).

Study population

The eligibility criteria were similar to those used for the pivotal studies of reference adalimumab in psoriasis.14, 15 Adult patients with active but clinically stable moderate‐to‐severe chronic plaque‐type psoriasis diagnosed ≥ 6 months before study baseline, who had previously received phototherapy or systemic psoriasis therapy or who were candidates for such therapies were enrolled. Moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis was defined as a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score ≥12,16, 17 a modified Physician's Global Assessment (PGA) score ≥ 3 (based on a scale of 0–4)18 and ≥ 10% body surface area affected by plaque‐type psoriasis. Patients must have had no evidence of active tuberculosis. Key exclusion criteria included topical therapy against psoriasis or phototherapy within 2 weeks of baseline, and previous use of biologics for the treatment of autoimmune disease (other than the use of no more than one of either etanercept or infliximab). Detailed exclusion criteria are listed in Appendix S1 (see Supporting Information).

All patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the current International Council on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with local regulatory requirements. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board for each centre.

Study design

The trial consisted of four periods: a screening period, a double‐blind core treatment period (weeks 1–16), a double‐blind extension treatment period (weeks 16–52) and a 4‐month safety follow‐up period (from last dose of study drug to week 66). After the screening period, patients were randomized 1 : 1 to receive MSB11022 or reference adalimumab (Humira®; AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL, U.S.A.; European Union authorized). Patients were stratified by previous systemic therapy use (pretreated vs. treatment naive), and pretreated patients were stratified by the type of systemic therapy received (biologic vs. nonbiologic). The allocation sequence was generated centrally by Cenduit (Nottingham, U.K.) using permuted blocks. The investigators enrolled patients by contacting the central interactive web response system, which assigned patients to their groups according to the allocation sequence.

MSB11022 or reference adalimumab was administered at an initial dose of 80 mg subcutaneously, followed by 40 mg every other week starting 1 week after the first dose. At week 16, patients who achieved ≥ 50% improvement in PASI from baseline (PASI 50) were eligible to enter the extension period. Patients initially randomized to receive MSB11022 continued treatment, and patients initially randomized to receive reference adalimumab were rerandomized in a 1 : 1 ratio either to continue reference adalimumab or to switch to MSB11022. Patients who failed to achieve PASI 50 at week 16 or at any subsequent visit were discontinued from the trial. A full safety and immunogenicity assessment was performed 4 weeks after the last dose of MSB11022 or adalimumab (week 54 for patients who completed the extended treatment period). Adverse events were also recorded at a safety follow‐up 4 months after the last dose of study drug (Fig. 1). The CONSORT statement for noninferiority and equivalence trials was used to report the results.19

Figure 1.

Study design. *Only patients who achieved ≥ 50% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index at week 16 were eligible to enter the extended treatment period. EOW, every other week.

Assessments

The primary end point was the PASI 75 response rate at week 16. The key secondary end point was the percentage change from baseline in PASI at week 16. Other PASI and PGA‐related efficacy end points are described in Appendix S2 (see Supporting Information). QoL was assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),20 EuroQoL 5‐Dimensions 5‐Levels (EQ‐5D‐5L),21 Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ‐DI)22 and Patient Global Assessment for Joints on a Visual Analogue Scale (PJA‐VAS)23 questionnaires. HAQ‐DI and PJA‐VAS were used for patients who also had psoriatic arthritis. Safety was assessed by monitoring for treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and serious adverse events. Adverse events of special interest were predefined as serious infections (those requiring hospitalization, those with fatal outcome or sepsis, or those requiring intravenous antibiotics or antimicrobials), latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis.

Predose serum concentrations of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab were measured at weeks 1, 2, 14, 15, 24, 25, 32 and 33. Serum concentrations were quantified using a validated enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay in a central clinical laboratory. The incidence of antidrug antibodies (ADAs) was assessed using a highly sensitive and drug‐tolerant validated bioanalytical method based on the Meso Scale Discovery Electrochemiluminescent platform (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.).13 The assay sensitivity was 86·4 ng mL−1 with a drug tolerance of 250 μg mL−1 at the low positive control level of 129·6 ng mL−1.13

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy analysis was based on the per protocol set, which consisted of all randomized patients who completed the study until week 16 without major protocol deviations. A sensitivity analysis was performed in the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, which included all randomized patients. Secondary end points were assessed in the per protocol and ITT populations. The safety population included all randomized patients who received a dose of MSB11022 or reference adalimumab.

For the primary end point, MSB11022 and reference adalimumab were considered equivalent if the PASI 75 response rate for the MSB11022 arm was within ± 18% of the reference adalimumab arm after 16 weeks of treatment. The two treatment groups were compared using the two‐sided 95% stratified Newcombe confidence interval (CI) for the difference in PASI 75 response rate. Therapeutic equivalence was established if the 95% CI was included in the prespecified equivalence interval. Equivalence margins were determined based on values reported in the literature and agreed with the regulatory authorities.

A sample size of 382 patients was calculated based on two assumptions. Firstly, an estimated response rate of 59% for the primary end point was assumed, based on a weighted mean of response rates observed for various patient populations in previous adalimumab studies.14, 15, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Secondly, no expected difference between EU approved reference adalimumab and MSB11022 was assumed following a single 80‐mg dose of reference adalimumab at week 1 and a 40‐mg dose every other week from weeks 2 to 16.14, 15, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32 This sample size provided a 90% power for the equivalence margin of 18% and a type I error of 2·5% (one sided).

For the per protocol set, little or no missing data were expected, so no imputation was performed. For the ITT analysis, patients with a missing PASI value at week 16 were classified as nonresponders. The key secondary end point of percentage change in PASI from baseline to week 16 was analysed using an analysis of covariance model, with treatment group and previous systemic therapy use as fixed factors, and baseline PASI as a covariate. Therapeutic equivalence for the key secondary end point was confirmed if the 95% CI of the least squares mean treatment difference was within the predefined interval of ± 15%. Additional details on the efficacy analyses are provided in Appendix S2 (see Supporting Information).

Results

Demographics

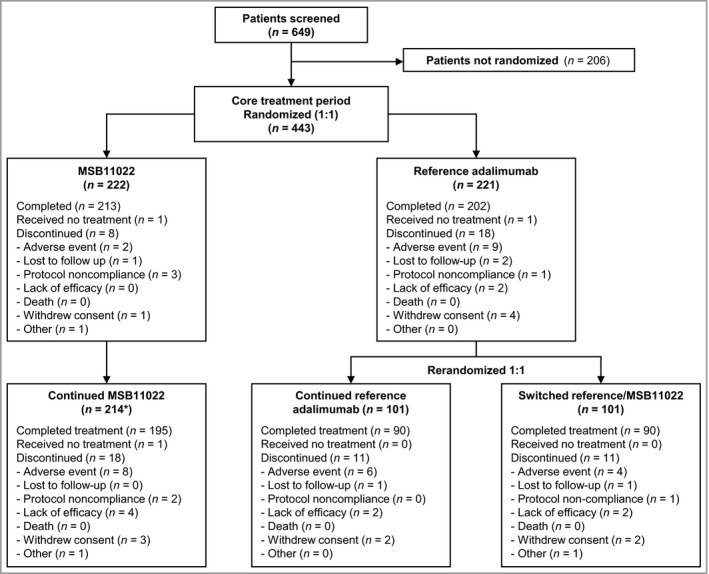

In total, 443 patients were randomized (MSB11022, n = 222; reference adalimumab, n = 221) and included in the ITT population. Of these, 19 patients (8·6%) in the MSB11022 arm and 30 patients (13·6%) in the reference adalimumab arm were excluded from the per protocol set either due to not completing the 16‐week study or due to major protocol violations. At week 16, 214 (96·4%) patients continued receiving MSB11022 and 202 (91·4%) patients from the reference adalimumab group were rerandomized either to continue receiving reference adalimumab (n = 101) or to transition to MSB11022 (n = 101). In the core treatment period, all except two patients (one per arm) received at least one administration of trial treatment and were included in the safety analysis set (Fig. 2). The patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. *One patient in the MSB11022 group had a temporary treatment interruption at the time of the week 16 visit due to an adverse event, and was not counted as completing the core treatment period. This patient was included in the extension treatment period.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (per protocol set)

| MSB11022 (n = 203) | Reference adalimumab (n = 191) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 136 (67·0) | 130 (68·1) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 44·8 ± 12·7 | 42·4 ± 11·8 |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 192 (94·6) | 179 (93·7) |

| Black | 1 (0·5) | 0 |

| Asian | 3 (1·5) | 8 (4·2) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 7 (3·4) | 4 (2·1) |

| Region, n | Both arms | |

| Europe | 326 | |

| Americas | 68 | |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 81·4 ± 13·5 | 80·0 ± 13·1 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 26·6 ± 3·1 | 26·3 ± 3·0 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 27·6 (24·2–29·1) | 26·8 (24·2–29·1) |

| PASI | ||

| Mean ± SD | 20·6 ± 8·8 | 21·2 ± 8·1 |

| Median (range) | 17·4 (12·0–61·8) | 18·4 (12·1–48·2) |

| BSA affected (%) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 28·6 ± 14·3 | 29·9 ± 13·6 |

| Median (range) | 25·9 (11·0–86·0) | 27·1 (10·0–72·0) |

| PGA, n (%) | ||

| Moderate | 146 (71·9) | 128 (67·0) |

| Severe | 57 (28·1) | 63 (33·0) |

| Previous biologic or other therapy for psoriasis, n (%) | 177 (87·2) | 168 (88·0) |

| Previous biologic or other therapy, n (%) | ||

| Etanercept | 22 (10·8) | 24 (12·6) |

| Infliximab | 2 (1·0) | 1 (0·5) |

| Other | 175 (86·2) | 166 (86·9) |

PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; BSA, body surface area; PGA, Physician's Global Assessment.

Efficacy

Primary end point

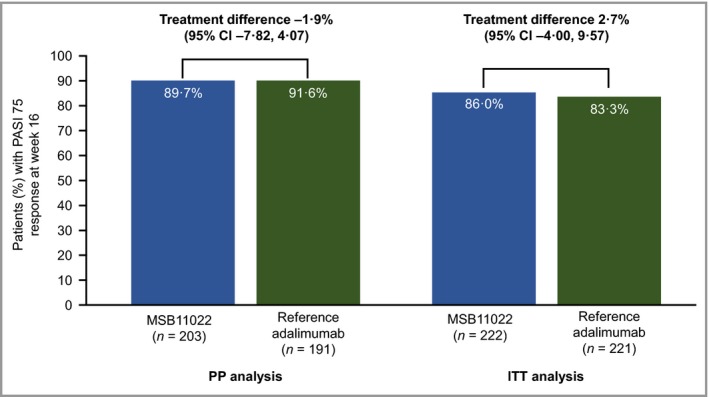

The PASI 75 response rate at week 16 was 89·7% in the MSB11022 arm and 91·6% in the reference adalimumab arm, with a treatment difference of −1·9% (95% CI −7·82 to 4·07). As the 95% CI was contained within the prespecified equivalence interval (± 18%), equivalent efficacy was shown (Fig. 3). Consistent results were reported in a sensitivity analysis performed on the ITT population (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Response rate of ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) at week 16 in the per protocol (PP) and intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis sets. CI, confidence interval.

Key secondary end point

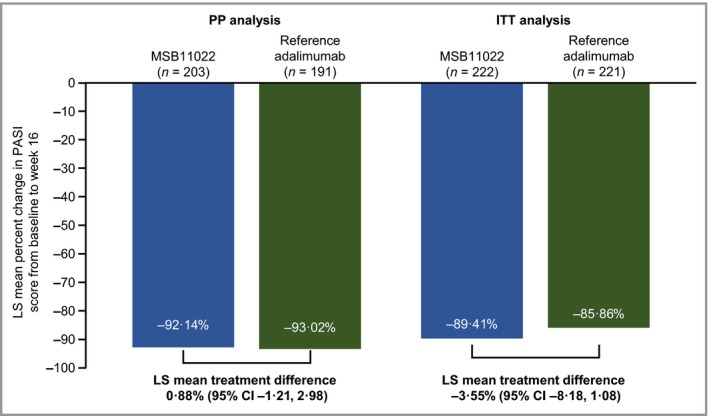

The least squares mean (± standard error) percentage change in PASI from baseline to week 16 was −92·1 ± 0·86 with MSB11022 vs. −93·0 ± 0·87 with reference adalimumab. The treatment difference (least squares mean difference 0·88%, 95% CI −1·21% to 2·98%) was contained within the prespecified interval (± 15%) and so equivalence was confirmed (Fig. 4). Consistent results were reported in a sensitivity analysis performed on the ITT population (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage change in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) from baseline to week 16 in the per protocol (PP) and intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis sets. LS, least squares; CI, confidence interval.

Other end points

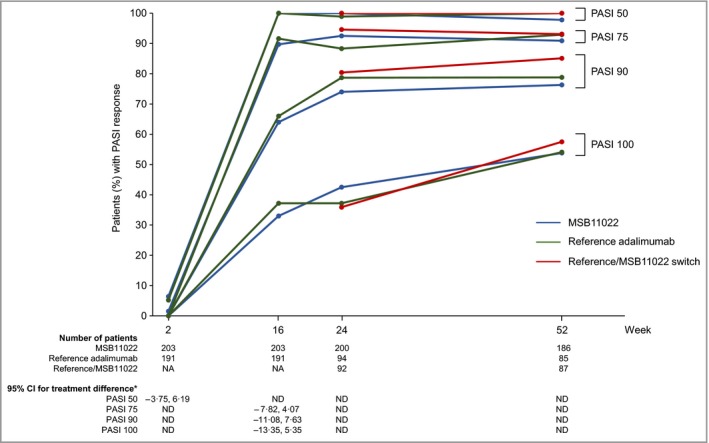

At all scheduled visits up to week 52, the PASI response rates were comparable between the MSB11022, continued reference adalimumab and switch arms (Fig. 5). The percentage change in PASI from baseline to weeks 24 and 52, the time to achieve PASI 75, 90 and 100 and improvements in PGA at weeks 24 and 52 were also comparable between treatment arms (Table S1; see Supporting Information). Improvements in QoL scores at weeks 16, 24 and 52 were similar across treatment groups (Table 2; and Table S2; see Supporting Information). Treatment effects were consistent across the subgroups stratified by previous systemic therapy (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Response rates of ≥ 50%, ≥ 75%, ≥ 90% and 100% in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 50, 75, 90 and 100) in the per protocol set. *95% confidence interval (CI) for the treatment difference between MSB11022 and reference adalimumab. NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

Table 2.

Improvement in quality‐of‐life scores at weeks 24 and 52

| DLQI | EQ‐5D‐5L | EQ‐5D‐5L VAS | HAQ‐DI | PJA‐VAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSB11022 (n = 203) | |||||

| Week 1 | 14·0 ± 7·02 | 0·76 ± 0·15 | 64·1 ± 22·4 | 0·57 ± 0·55 | 41·9 ± 23·5 |

| Week 24 | 2·5 ± 4·13 | 0·89 ± 0·11 | 83·2 ± 14·3 | 0·35 ± 0·40 | 29·7 ± 25·3 |

| Week 52 | 3·0 ± 4·74 | 0·90 ± 0·11 | 83·5 ± 15·6 | 0·34 ± 0·45 | 25·0 ± 20·3 |

| Reference adalimumab (n = 95) | |||||

| Week 1 | 12·6 ± 6·94 | 0·77 ± 0·16 | 64·7 ± 25·4 | 0·45 ± 0·58 | 32·4 ± 26·9 |

| Week 24 | 2·3 ± 4·04 | 0·90 ± 0·13 | 84·2 ± 13·8 | 0·28 ± 0·54 | 20·6 ± 27·1 |

| Week 52 | 2·1 ± 3·50 | 0·90 ± 0·12 | 85·1 ± 13·3 | 0·09 ± 0·24 | 14·7 ± 16·5 |

| Reference/MSB11022 switch (n = 96) | |||||

| Week 1 | 14·0 ± 6·79 | 0·76 ± 0·14 | 63·3 ± 22·6 | 0·87 ± 0·44 | 48·8 ± 24·1 |

| Week 24 | 2·3 ± 3·90 | 0·91 ± 0·12 | 84·3 ± 14·0 | 0·44 ± 0·36 | 24·9 ± 20·5 |

| Week 52 | 2·7 ± 4·03 | 0·88 ± 0·14 | 82·1 ± 16·2 | 0·51 ± 0·35 | 29·5 ± 19·7 |

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EQ‐5D‐5L (VAS), EuroQoL 5‐Dimensions 5‐Levels (visual analogue scale); HAQ‐DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; PJA‐VAS, Patient Joint Assessment Visual Analogue Scale. DLQI and EQ‐5D‐5L were collected for all patients, and HAQ‐DI and PJA‐VAS were collected only for patients with psoriatic arthritis (MSB11022, n = 21; reference adalimumab, n = 9; reference/MSB11022 switch, n = 13).

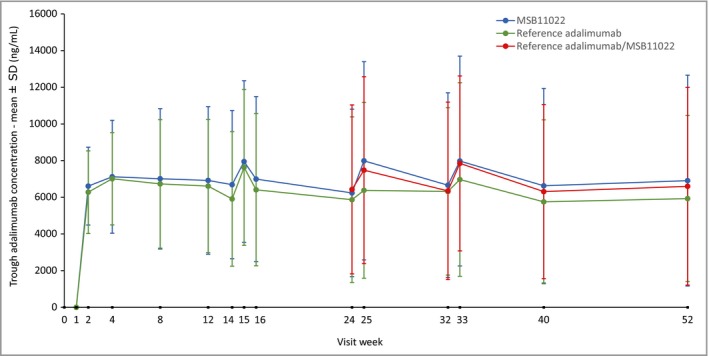

Pharmacokinetic results

Mean trough concentrations reached steady‐state levels by week 2 (1 week after the initial dose) in all treatment arms (Fig. 6). Mean trough levels up to week 52 were comparable across the MSB11022, reference adalimumab and reference/MSB11022 switch treatment groups.

Figure 6.

Trough plasma concentrations of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab until week 52. Only patients who consented to take part in a pharmacokinetic substudy provided samples at weeks 14, 15, 25 and 33.

Safety

The median duration of exposure was 15 weeks for both the MSB11022 and reference adalimumab arms during the 16‐week core treatment period. In both arms, the median number of injections in the core treatment period was nine. For the core and extended treatment periods, the median duration of exposure was 51 weeks in all treatment arms.

During the core treatment period up to week 16, a similar proportion of patients in the MSB11022 and reference adalimumab arms had at least one TEAE (MSB11022: n = 114, 51·6%; reference adalimumab: n = 117, 53·2%) (Table S3; see Supporting Information). From baseline to week 66, the proportions of patients with at least one TEAE were similar between the MSB11022 group (n = 173, 78·3%), the continued reference adalimumab group (n = 92, 77·3%) and the switch group (n = 76, 75·2%) (Table 3). The incidences of serious adverse events, treatment‐related TEAEs, TEAEs of special interest, treatment discontinuations due to TEAEs, injection‐site reactions and hypersensitivity reactions were similar between all three treatment arms through to week 66 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events up to week 66

| MSB11022 (n = 221) | Continued reference adalimumab (n = 119) | Reference/MSB11022 switch (n = 101) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEAE | 173 (78·3) | 92 (77·3) | 76 (75·2) |

| Serious TEAE | 20 (9·0) | 8 (6·7) | 5 (5·0) |

| Treatment‐related TEAE | 69 (31·2) | 41 (34·5) | 33 (32·7) |

| Serious treatment‐related TEAE | 3 (1·4) | 5 (4·2) | 0 |

| TEAE of special interesta | 12 (5·4) | 4 (3·4) | 4 (4·0) |

| Permanent treatment discontinuation due to TEAE | 10 (4·5) | 16 (13·4) | 4 (4·0) |

| Death | 0 | 1 (0·8) | 0 |

| Injection‐site reaction TEAEsb | 37 (16·7) | 21 (17·6) | 25 (24·8) |

| Hypersensitivity TEAEsc | 10 (4·5) | 4 (3·4) | 6 (5·9) |

The data are presented as the number (%) of patients. TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event. aSerious infection, latent tuberculosis infection, or active tuberculosis infection. bIncludes the following preferred terms: injection‐site bruising, injection‐site erythema, injection‐site haematoma, injection‐site haemorrhage, injection‐site induration, injection‐site oedema, injection‐site pain, injection‐site pruritus, injection‐site rash, injection‐site swelling. cIncludes the following preferred terms: injection‐site rash, anaphylactic shock, drug hypersensitivity, rash pustular, rhinitis allergic, dermatitis, dermatitis allergic, dermatitis contact, eczema, erythema multiforme, hypersensitivity vasculitis, idiopathic urticaria, rash, urticaria.

One patient died during the study (in the continued reference adalimumab group in the extended treatment period); the death was reported to be due to an accident with subsequent cardiac failure, cerebral haematoma and brain oedema. This event was considered to be unrelated to trial treatment.

Immunogenicity

During the core treatment period, 88·1% and 88·4% of patients in the MSB11022 and reference adalimumab treatment arms had at least one positive ADA result, and 41·1% and 42·3% of patients in the MSB11022 and reference adalimumab arms, respectively, had a positive neutralizing antibody result. From baseline to week 52, the incidences of at least one positive ADA result were reported to be 93·2%, 92·1% and 94·1% for patients in the MSB11022, continued reference adalimumab and switch treatment arms, respectively. For the three treatment groups, at least one positive neutralizing antibody result was reported for 63·0%, 61·4% and 58·4%, respectively, of patients during that period. The immunogenicity results for the 52‐week treatment period are summarized in Figure S1 (see Supporting Information). No differences in PASI 75 response rates by ADA status were observed at weeks 16, 24 and 52 (Fig. S2; see Supporting Information). ADA‐positive patients had lower serum concentrations of adalimumab than patients who were ADA negative in all three treatment arms, with similar concentration–time profiles for the MSB11022 and reference adalimumab groups (Fig. S3; see Supporting Information).

Discussion

MSB11022 was shown to be equivalent to the reference adalimumab product after 16 weeks of treatment in terms of the primary end point of PASI 75 response rate, which is a clinically meaningful end point in clinical trials, and is considered by clinicians to be indicative of success in the treatment of patients with psoriasis.33 Equivalence between MSB11022 and reference adalimumab was also shown for the secondary efficacy end points.

The PASI 75 response rates observed in this study are higher than those seen in previous phase III adalimumab trials;14, 34 however, they are in line with more recent studies,35, 36 which may reflect the improved standard of care for patients with psoriasis. In AURIEL‐PsO, the proportion of patients with moderate disease was 70·0%, compared with previous studies ranging from 18·6% to 65·5%.34, 35 Previous studies with greater proportions of patients with moderate psoriasis also showed higher response rates.35, 36 In addition, patients with psoriasis with a higher BMI have previously been shown to be less responsive to adalimumab31 or to discontinue earlier.37 Therefore, the exclusion criteria in this study were designed to reduce the number of patients with a high body weight in order to increase the sensitivity of the population to show any differences between treatment arms. The mean weight of the study population was lower than in some previous trials establishing the efficacy of the reference product or other adalimumab biosimilars,14, 38, 39 but it was similar to or higher than weights in other adalimumab trials.15, 34, 35

Increases in the proportions of patients achieving PASI 90 and 100 from week 16 to 52 were also observed in all treatment arms. Again, this continued response may be due to the sensitive population selected for this trial. The efficacy results are supported by the QoL data, with no meaningful differences across treatment groups observed for any of the health‐related QoL measures used in this study. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic data were consistent with results from a phase I study, in which the median time to maximum observed serum concentration was approximately 191 hours (8 days) for MSB11022 and for reference adalimumab.13

MSB11022 and reference adalimumab also showed comparable safety up to week 66, with no new safety signals observed. Immunogenicity was also similar between the two treatments, although the incidences of ADAs and neutralizing antibodies were considerably higher than those previously reported for reference adalimumab.40 This likely reflects the fact that more sensitive and drug‐tolerant assays were used in these studies than were used in previous studies with the reference product,41 and is consistent with the higher immunogenicity rates reported in more recent studies of adalimumab.42 Of note, it is reassuring that no differences in PASI 75 response rates were observed between ADA‐positive and ADA‐negative patients in this study. Although serum concentrations of adalimumab were lower in the ADA‐positive subgroup, mean trough concentrations remained above 5000 ng mL−1, which is considered to be within the therapeutic range.43 The differences observed between ADA subgroups in serum adalimumab concentration were consistent between the two treatment arms up to week 52.

Patients who switched from reference adalimumab to MSB11022 at week 16 showed similarity in all efficacy, safety and immunogenicity end points assessed compared with patients who continued on MSB11022 or reference product throughout the trial. This is consistent with several previous studies that have shown no impact of switching, including multiple switches, from a TNF inhibitor reference product to a biosimilar and vice versa in inflammatory disease.44, 45, 46, 47

The present study and analysis of switching data have some limitations. Most importantly, as its primary objective was to assess biosimilarity, the study was not powered for statistical comparisons of equivalence after switching. However, the study design was agreed with the regulatory authorities to meet the requirements of a therapeutic equivalence study and is consistent with the majority of biosimilar equivalence studies that incorporate a switch element.10 Like all randomized controlled trials, generalizability of the results may be limited by the selection of a patient population which may be less heterogeneous than seen in clinical practice.

In conclusion, no clinically meaningful differences in efficacy, safety or immunogenicity were seen between MSB11022 and reference adalimumab up to 52 weeks of treatment in a highly sensitive population of patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque‐type psoriasis. No new or unexpected safety issues were reported, and the safety profiles of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab were similar to those reported in previous studies with reference adalimumab. A switch from reference adalimumab to MSB11022 at week 16 did not impact efficacy, safety or immunogenicity. The results presented here provide confirmation of the clinical similarity of MSB11022 and reference adalimumab and contribute to the totality of the evidence supporting MSB11022 as an adalimumab biosimilar.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Full exclusion criteria.

Appendix S2. Full details of efficacy end points and statistical analyses of other secondary efficacy end points.

Appendix S3. Full list of investigators in the AURIEL‐PsO trial.

Fig S1. Incidences of (a) antidrug antibodies and (b) neutralizing antibodies from baseline to week 54.

Fig S2. Response rate of ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index by antidrug antibody status at weeks 16, 24 and 52.

Fig S3. Mean adalimumab serum concentration–time profiles by antidrug antibody status up to week 52.

Table S1 Other secondary efficacy end points (per protocol set).

Table S2 Improvements in quality‐of‐life scores at week 16.

Table S3 Treatment‐emergent adverse events up to week 16.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and study personnel involved in this study. A full list of study investigators is provided in Appendix S3 (see Supporting Information). Editorial support was provided by Stephanie Carter of Arc Medical Communications Ltd, supported by Fresenius Kabi.

Conflicts of interest

J.H. has received honoraria for attendance at advisory boards for Novartis, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Nordic Pharma, UCB, Sanofi Genzyme and Fresenius Kabi; as an investigator for AbbVie, Merck, Amgen, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Pfizer; and as a speaker for AbbVie, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Janssen‐Cilag, LEO Pharma, L'Oréal, Nordic Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre and Sanofi‐Aventis. K.A.P. has received honoraria for attendance at advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dow Pharma, Eli Lilly, Fresenius Kabi, Galderma, Janssen, Merck (MSD), Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi‐Aventis/Genzyme, UCB and Valeant; as a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Kyowa Hakka Kirin, LEO, Merck (MSD), Novartis, Pfizer and Valeant; as a consultant for AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, Baxalta, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Dow Pharma, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Kyowa Hakka Kirin, LEO, Merck (MSD), Merck‐Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis/Genzyme, Takeda, UCB and Valeant; and for other activities for AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, Anacor, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Kyowa Hakka Kirin, Merck (MSD), Merck‐Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi‐Aventis/Genzyme and Valeant; and has received grants as an investigator for AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, Anacor, Baxalta, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Dow Pharma, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Janssen, Kyowa Hakka Kirin, LEO, Merck (MSD), Merck‐Serono, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi‐Aventis/Genzyme, Takeda, UCB and Valeant. V.C. is a former employee of Fresenius Kabi SwissBioSim. M.U. is an employee of Fresenius Kabi SwissBioSim. P.V. has no conflicts of interest to declare. C.J.E. has received honoraria for attendance at advisory boards for AbbVie, Biogen, BMS, Celgene, Fresenius Kabi, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, Mundipharma, Roche and Sanofi; and as a consultant for Anthera, Merck and Samsung Bioepis; and has received grants as an investigator for AbbVie, Biogen and Pfizer.

Funding sources This study was sponsored by Merck. Fresenius Kabi acquired the asset from Merck KGaA in September 2017.

Conflicts of interest Conflicts of interest statements can be found in the Appendix.

References

- 1. Feldmann M, Maini RN. Anti‐TNF therapy, from rationale to standard of care: what lessons has it taught us? J Immunol 2010; 185:791–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaymakcalan Z, Sakorafas P, Bose S et al Comparisons of affinities, avidities, and complement activation of adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept in binding to soluble and membrane tumor necrosis factor. Clin Immunol 2009; 131:308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lapadula G, Marchesoni A, Armuzzi A et al Adalimumab in the treatment of immune‐mediated diseases. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2014; 27:33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Putrik P, Ramiro S, Kvien TK et al Variations in criteria regulating treatment with reimbursed biologic DMARDs across European countries. Are differences related to country's wealth? Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73:2010–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalo Z, Voko Z, Ostor A et al Patient access to reimbursed biological disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs in the European region. J Mark Access Health Policy 2017; 5:1345580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrascosa JM, Jacobs I, Petersel D et al Biosimilar drugs for psoriasis: principles, present, and near future. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2018; 8:173–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blauvelt A, Cohen AD, Puig L et al Biosimilars for psoriasis: preclinical analytical assessment to determine similarity. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:282–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blauvelt A, Puig L, Chimenti S et al Biosimilars for psoriasis: clinical studies to determine similarity. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen AD, Wu JJ, Puig L et al Biosimilars for psoriasis: worldwide overview of regulatory guidelines, uptake and implications for dermatology clinical practice. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177:1495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM et al Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs 2018; 78:463–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. European Medicines Agency . Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology‐derived proteins as active substance: non‐clinical and clinical issues. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-containing-biotechnology-derived-proteins-active_en-2.pdf (last accessed 18 July 2019).

- 12. Magnenat L, Palmese A, Fremaux C et al Demonstration of physicochemical and functional similarity between the proposed biosimilar adalimumab MSB11022 and Humira. MAbs 2017; 9:127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hyland E, Mant T, Vlachos P et al Comparison of the pharmacokinetics, safety, and immunogenicity of MSB11022, a biosimilar of adalimumab, with Humira® in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 82:983–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menter A, Tyring SK, Gordon K et al Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 58:106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L et al Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION). Br J Dermatol 2008; 158:558–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis – oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica 1978; 157:238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmitt J, Wozel G. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is the adequate criterion to define severity in chronic plaque‐type psoriasis. Dermatology 2005; 210:194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Langley RG, Feldman SR, Nyirady J et al The 5‐point Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat 2015; 26:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ et al Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 2012; 308:2594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19:210–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yfantopoulos J, Chantzaras A, Kontodimas S. Assessment of the psychometric properties of the EQ‐5D‐3L and EQ‐5D‐5L instruments in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 2017; 309:357–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005; 23 (5 Suppl. 39):S14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cauli A, Gladman DD, Mathieu A et al Patient global assessment in psoriatic arthritis: a multicenter GRAPPA and OMERACT study. J Rheumatol 2011; 38:898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K et al An assessment of adalimumab efficacy in three phase III clinical trials using the European Consensus Programme criteria for psoriasis treatment goals. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Lumig PP, Lecluse LL, Driessen RJ et al Switching from etanercept to adalimumab is effective and safe: results in 30 patients with psoriasis with primary failure, secondary failure or intolerance to etanercept. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163:838–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woolf RT, Smith CH, Robertson K et al Switching to adalimumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who have failed on etanercept: a retrospective case cohort study. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163:889–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bissonnette R, Bolduc C, Poulin Y et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with plaque psoriasis who have shown an unsatisfactory response to etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63:228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pitarch G, Sanchez‐Carazo JL, Mahiques L et al Treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007; 32:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ryan C, Kirby B, Collins P et al Adalimumab treatment for severe recalcitrant chronic plaque psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2009; 34:784–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Menter A, Gordon KB, Leonardi CL et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab across subgroups of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63:448–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prussick R, Unnebrink K, Valdecantos WC. Efficacy of adalimumab compared with methotrexate or placebo stratified by baseline BMI in a randomized placebo‐controlled trial in patients with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol 2015; 14:864–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thaçi D, Ortonne JP, Chimenti S et al A phase IIIb, multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, vehicle‐controlled study of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab with and without calcipotriol/betamethasone topical treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: the BELIEVE study. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163:402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu JJ. Contemporary management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Manag Care 2017; 23 (21 Suppl.):S403–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Asahina A, Nakagawa H, Etoh T et al Adalimumab in Japanese patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II/III randomized controlled study. J Dermatol 2010; 37:299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cai L, Gu J, Zheng J et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in Chinese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: results from a phase 3, randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Papp K, Bachelez H, Costanzo A et al Clinical similarity of the biosimilar ABP 501 compared with adalimumab after single transition: long‐term results from a randomized controlled, double‐blind, 52‐week, phase III trial in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177:1562–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lafuente‐Urrez RF, Perez‐Pelegay J. Impact of obesity on the effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of psoriasis: a retrospective study of 30 patients in daily practice. Eur J Dermatol 2014; 24:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gordon KB, Duffin KC, Bissonnette R et al A phase 2 trial of guselkumab versus adalimumab for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gordon KB, Langley RG, Leonardi C et al Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double‐blind, randomized controlled trial and open‐label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. AbbVie Inc . Prescribing information: HUMIRA (adalimumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Available at: http://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/humira.pdf (last accessed 18 July 2019).

- 41. Song S, Yang L, Trepicchio WL et al Understanding the supersensitive anti‐drug antibody assay: unexpected high anti‐drug antibody incidence and its clinical relevance. J Immunol Res 2016; 2016:3072586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gorovits B, Baltrukonis DJ, Bhattacharya I et al Immunoassay methods used in clinical studies for the detection of anti‐drug antibodies to adalimumab and infliximab. Clin Exp Immunol 2018; 192:348–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Menting SP, Coussens E, Pouw MF et al Developing a therapeutic range of adalimumab serum concentrations in management of psoriasis: a step toward personalized treatment. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151:616–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blauvelt A, Lacour JP, Fowler JF Jr et al Phase III randomized study of the proposed biosimilar adalimumab GP2017 in psoriasis: impact of multiple switches. Br J Dermatol 2018; 179:623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jorgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL et al Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT‐P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR‐SWITCH): a 52‐week, randomised, double‐blind, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2017; 389:2304–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weinblatt ME, Baranauskaite A, Dokoupilova E et al Switching from reference adalimumab to SB5 (adalimumab biosimilar) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: fifty‐two‐week phase III randomized study results. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70:832–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yoo DH, Prodanovic N, Jaworski J et al Efficacy and safety of CT‐P13 (biosimilar infliximab) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison between switching from reference infliximab to CT‐P13 and continuing CT‐P13 in the PLANETRA extension study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76:355–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Full exclusion criteria.

Appendix S2. Full details of efficacy end points and statistical analyses of other secondary efficacy end points.

Appendix S3. Full list of investigators in the AURIEL‐PsO trial.

Fig S1. Incidences of (a) antidrug antibodies and (b) neutralizing antibodies from baseline to week 54.

Fig S2. Response rate of ≥ 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index by antidrug antibody status at weeks 16, 24 and 52.

Fig S3. Mean adalimumab serum concentration–time profiles by antidrug antibody status up to week 52.

Table S1 Other secondary efficacy end points (per protocol set).

Table S2 Improvements in quality‐of‐life scores at week 16.

Table S3 Treatment‐emergent adverse events up to week 16.