Abstract

Aim

Regional core centers for the management of liver disease, which are located in every prefecture in Japan, not only take the lead in hepatitis care in their respective regions, but also serve a wide range of other functions, such as education, promotion of hepatitis testing, treatment, and research.

Method

Since fiscal year 2010, the Hepatitis Information Center has conducted surveys of regional core centers throughout Japan regarding information about their facilities, programs for patient support, training, and education of medical personnel.

Results

By compiling and analyzing the results of these surveys, we have elucidated the status of regional core centers and the issues they currently have. We found that regional core centers have come to play widely varied roles in hepatitis treatment and have expanded their programs. These surveys also suggest that uniform accessibility of hepatitis treatment has been implemented throughout Japan.

Conclusion

To continue serving their diverse roles, regional core centers require further development of hepatitis care networks that include specialized institutions, primary care physicians, and local and central governments; as well as collaboration with other professions and groups.

Keywords: Council for Hepatitis Treatment, counseling and support service, educational activities, hepatitis medical care coordinators, regional hepatitis care networks

Introduction

Viral hepatitis poses a major public health problem in Japan. The national government is therefore undertaking comprehensive measures for hepatitis,1 which currently consist of the following five strategies: (i) promotion of hepatitis virus testing; (ii) introduction of the subsidy system for medical care for hepatitis; (iii) establishment of medical care system for hepatitis, (iv) enlightenment and dissemination of the need for early detection and treatment, and (v) promotion of research on hepatitis.2

The strengthening of regional hepatitis care networks began in 2007, when the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) issued “Guidelines for the System for Treatment of Liver Disease after Hepatitis Testing in Local Regions” (Report of the National Conference of Hepatitis C on 26 January 2007) and “Maintenance of Hepatitis Care Networks” (Health Service Bureau Notice No. 0419001).3 The above served as the foundation for the nationwide establishment of hepatitis care networks consisting of regional core centers for the management of liver disease (hereinafter, “regional core centers”), institutions specializing in liver disease (hereinafter, “specialized institutions”), and primary care physicians.

Regional core centers were first established in fiscal year (FY) 2007, and had been installed in all 47 prefectures in Japan by FY2011. At present, 71 institutions nationwide have been designated as regional core centers, all of which have counseling centers for liver disease (Table S1; Fig. S1). All regional core centers are medical institutions that meet the criteria for specialized institutions and are capable of providing multimodal therapy for liver cancer. Regional core centers are appointed by the Council for Hepatitis Treatment in every prefecture, and play a central role in liver disease care networks in their respective prefectures. Specialized institutions are appointed by the Council for Hepatitis Treatment in every prefecture; as of FY2018, roughly 3000 such institutions had been established throughout Japan. The prerequisites for specialized institutions and regional core centers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expected roles of medical institutions in hepatitis care network in each prefecture in Japan

| I. Specialized institutions (at least one institution in each secondary medical region) |

| a. Determination of diagnostic and therapeutic policy by physicians with specialized knowledge and skills in the management of liver disease |

| b. Providing antiviral therapy with interferon, nucleotide analogs, or DAAs |

| c. Identification of patients at high risk of liver cancer and its early diagnosis |

| II. Regional core centers (one hospital in each prefecture in principle) |

| a. Providing general medical information regarding liver disease |

| b. Collecting and providing information regarding medical institutions in prefectures |

| c. Organizing training workshops, lectures, and meetings, and supporting healthcare professionals and/or the public for acquiring information regarding liver disease |

| d. Setting up and management of a forum for discussions with specialized medical institutions for liver disease |

DAAs, direct‐acting antivirals.

Regional core centers in every prefecture, which serve as the nuclei of regional hepatitis care networks, as described above, not only collaborate with specialized institutions to lead the way in regional medical care for liver disease; but also play a crucial role in Japan's comprehensive measures for hepatitis. The Hepatitis Information Center, which was established in 2008 in the Research Center for Hepatitis and Immunology, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, have been conducting annual survey since 2010 on the activities of all regional core centers. These surveys investigate activities over the previous FY. By analyzing the cumulative results of surveys, the present study sought to elucidate the current status of regional core centers and the issues they face.

Methods

We examined the activities of all regional core centers in Japan from FY2010 to FY2018 (there were 55 regional core centers in Japan in FY 2009, 66 in FY2010, and 70 from FY2011 to FY2017). These surveys investigated activities over the previous FY. The survey items are broadly divided into five categories: (i) basic information about regional core centers; (ii) patient support; (iii) training; (iv) education; and (v) miscellaneous. We examined all 37 items covered in surveys on activities from FY2009 to FY2014, and all 90 items covered from FY2015 to FY2017. The survey form was an Excel file distributed to regional core centers by email. The response rate was 100%, although there were some missing responses. As of March 2019, a part of the results of previous surveys can be viewed on the Hepatitis Information Center's Website.4

As a control of health and welfare of people living in Japan, eight regional blocks are governed by eight Bureau of Health and Welfare, which are Hokkaido, Tohoku, Kanto‐Shinetsu, Tokai‐Hokuriku, Kinki, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu (Fig. S2). To gain the status of regional core centers from a regional perspective in this study, survey items were aggregated overall and by six regional blocks (Hokkaido‐Tohoku, Kanto‐Koshin'etsu, Tokai‐Hokuriku, Kinki, Chugoku‐Shikoku, and Kyushu). Activities conducted from FY2015 to FY2017 were broadly divided into eight categories: (i) counseling and support services; (ii) liver disease seminars/family support; (iii) employment, treatment, and work–life balance support; (iv) other forms of patient support; (v) regional counseling and support networks (hepatitis medical care coordinators); (vi) training; (vii) education; and (viii) in‐hospital alerts for patients with positive hepatitis virus tests (positive hepatitis virus test patient alert system, etc.; Table 2). Using a standardized index in which the overall mean and standard deviation are respectively represented as 0 and 1, we assessed the characteristics of regional core centers by six blocks, as well as changes in those characteristics from FY2015 to FY2017. The formula for calculating the standardized index is z = (score – mean) / standard deviation.

Table 2.

Items used to calculate a standardized index

| I. Counseling and support services |

| a. Explanations of the counseling center website (yes/no) |

| b. Establishment of the counseling center (yes/no) |

| c. Number of counselors |

| d. Number of counseling sessions |

| e. Collaboration with municipal governments related to counseling and support services |

| II. Liver disease seminars/family support lectures |

| a. Number of liver disease seminars held |

| b. Mean number of participants in liver disease seminars |

| c. Number of family support lectures held |

| d. Mean number of participants in family support lectures |

| III. Employment support |

| a. Establishment of employment support services (yes/no) |

| b. Number of sessions |

| IV. Other forms of patient support |

| a. Patient meet‐ups (yes/no) |

| b. Lectures by patients or former patients |

| c. Peer supporter training workshops |

| d. Preparation/distribution of hepatitis patient support handbooks |

| V. Regional counseling and support networks |

| a. Training for hepatitis medical care coordinators (yes/no) |

| b. Number of hepatitis medical care coordinators in training |

| c. Knowledge of hepatitis medical care coordinator placement (yes/no) |

| VI. Training for health care workers |

| a. Number of regional core center liaison conferences held |

| b. Number of hepatitis specialist training workshops held |

| c. Mean number of participants in hepatitis specialist training workshops |

| d. Number of training workshops for general medical professionals held |

| e. Mean number of participants in training workshops for general medical professionals |

| VII. Education for citizens |

| a. Number of public seminars organized |

| b. Number of participants in public seminars |

| c. Preparation of hepatitis care support leaflets (yes/no) |

| d. Events/symposiums held (yes/no) |

| e. Preparation of posters/leaflets (yes/no) |

| f. Publicity via newspaper advertisements, train advertisements, newspaper articles, etc. (yes/no) |

| g. Other educational activities held (yes/no) |

| VIII. In‐hospital alerts for patients with positive hepatitis virus tests |

| a. Alert system using electronic medical records, etc. (yes/no) |

Statistical analysis and standardized index calculations were performed with IBM spss Statistics version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Overview of regional core centers

Regional core centers were first established in FY2007, and were established in all prefectures by FY2011. From FY2011 to FY2017, 70 institutions were appointed as regional core centers (as of FY2018, 71 institutions have been appointed, but the newest institution was outside the scope of the present study). Websites for regional core centers were first launched in FY2016, and have now been launched for all centers. A total of 15 prefectures have multiple regional core centers.

As of FY2013, all regional core centers have counseling centers for liver disease (hereinafter, “counseling centers”). Counseling centers were primarily publicized through hospital websites (67 regional core centers, 96%) and pamphlets (55 centers, 79%). As of FY2017, 64 regional core centers had launched homepages for their respective counseling centers.

Counseling and support services for liver disease

Counseling and support systems

From FY2009 to FY2014, 47–60% of counseling centers had multiple professionals responsible for counseling (hereinafter, “counselors”); since FY2015, this figure had increased to 84–87%. However, just 22–25% (FY2017: 21%) of counselors were full‐time counselors. The most common types of professionals serving as full‐time counselors (multiple responses permitted) were nurses, physicians, and office workers; whereas the most common types of professionals serving as part‐time counselors were physicians, nurses, and medical social workers. Among these counselors, the types of professionals who most often conducted counseling were physicians, nurses, and office workers.

The number of regional core centers that had prepared lists of anticipated questions and answers remained nearly constant at 12–18 (FY2017: 17 centers).

Number of counseling sessions and topics addressed

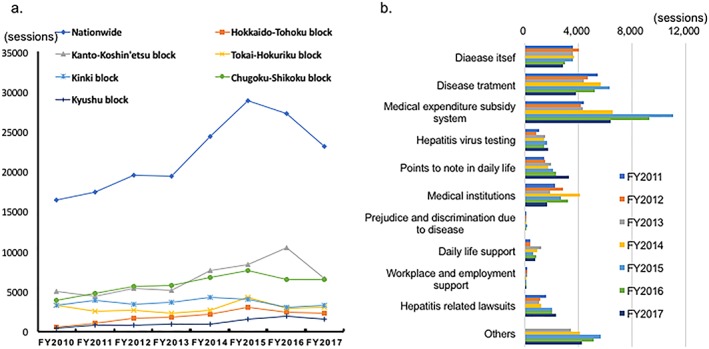

Regional core centers have recently provided a total of nearly 30 000 counseling sessions nationwide. The number of counseling sessions remained nearly constant from FY2010 to FY2013. In FY2014 and FY2015, the number of counseling sessions increased by 25% and 20%, respectively, compared with the previous FY. In FY2016 and FY2017, the number of counseling sessions (23 112 sessions in FY2017) instead decreased by 6% and 15%, respectively, compared with the previous FY. All regional blocks showed the same trend as the nationwide trend described above (Fig. 1a). The most frequent mean monthly number of counseling sessions was 1–10; the frequencies of 11–20, 21–50, and 51–100 monthly counseling sessions were all nearly equal. A few regional core centers conducted ≥101 counseling sessions in 1 month.

Figure 1.

Summary of counseling sought at counseling centers from fiscal year (FY)2010 to FY2017. (a) Numbers of counseling sessions over time (nationwide and by regional block). (b) Nationwide numbers of counseling sessions by topic over time. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Counseling was most commonly sought by the patients themselves, followed by the patient's family, other medical institutions, and local governments (FY2017: 15 270, 2733, 1189, and 354 people, respectively; other: 2052 people). Since FY2014, the most common topic addressed in counseling has been the medical expenditure subsidy system, followed by disease treatment and disease itself (Fig. 1b). In FY2016, all of the above topics were addressed less frequently in counseling; instead, the number of counseling sessions that addressed points to note in daily life, medical institutions, daily living support, and hepatitis‐related lawsuits all increased slightly. Also, in FY2016, the decrease in the number of counseling sessions that addressed medical expenditure subsidies compared with the previous FY (1745 fewer sessions) was roughly the same as the overall decrease in counseling sessions (1660 fewer sessions). In the Hokkaido‐Tohoku, Tokai‐Hokuriku, Kinki, and Chugoku‐Shikoku regional blocks, the most common topic addressed in counseling was the medical expenditure subsidy system. In the Kanto‐Koshin'etsu and Kyushu blocks, the most common topics were “other” and disease itself, respectively. Individual blocks differed in terms of topics for which counseling sessions increased.

Other forms of patient support

Liver disease seminars and family support lectures

Liver disease seminars are conducted to give patients with hepatitis the information they require regarding the pathology of hepatitis, the latest therapies, and points to note in daily life. The number of regional core centers that hold liver disease seminars has increased annually, as has the number of seminars. In FY2017, liver disease seminars were held at 60 regional core centers (86%; nationwide mean of 4.6 seminars/year), and were attended by a total of 5708 people. Most participants were patients themselves and their families; however, local residents accounted for roughly 20% of participants. The most common reasons for not holding liver disease seminars were problems with personnel, location, and cost.

Family support lectures were first held in FY2015; in FY2017, these lectures were held at 36 regional core centers (51%). The most common reasons for not holding liver disease seminars were problems with personnel, location, and cost.

Support for employment, treatment, and work–life balance (employment support)

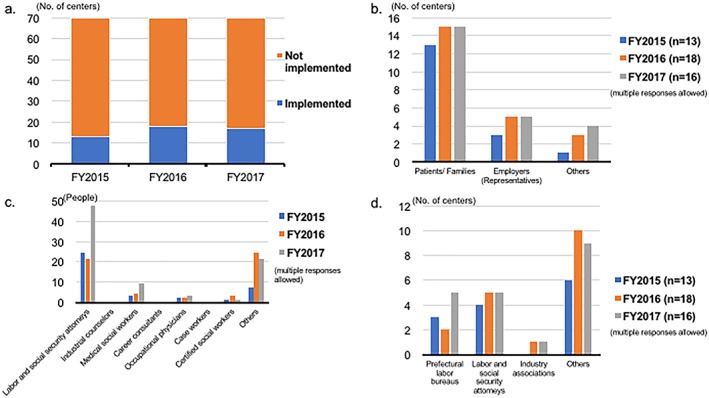

The employment support model project was started in FY2014 to maintain an environment that allows patients with hepatitis to receive appropriate medical care while continuing to work. In FY2017, employment support was provided at 17 regional core centers, which conducted 187 support sessions. The most common participants were patients themselves and their families, followed by employers and miscellaneous; representatives of employers consisted primarily of labor and social security attorneys (Fig. 2a–c). Employment support sessions were primarily held either at regional core centers only or at regional core centers and elsewhere, with many regional core centers holding regularly scheduled sessions. Most regional core centers that provided employment support (94% of them as of FY2017) did so in collaboration with other groups. The most common collaborators were: (i) Association of Labor and Social Security attorneys; (ii) prefectural labor bureaus; and (iii) patient groups; others included public health centers, public employment security offices, and occupational health support centers (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Summary of employment support project model from fiscal year (FY)2015 to FY2017. (a) The number of centers conducting employment support. (b) Participants. (c) Professions of representatives of employers. (d) Employment support partners. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Regional counseling and support services (training of hepatitis medical coordinators)

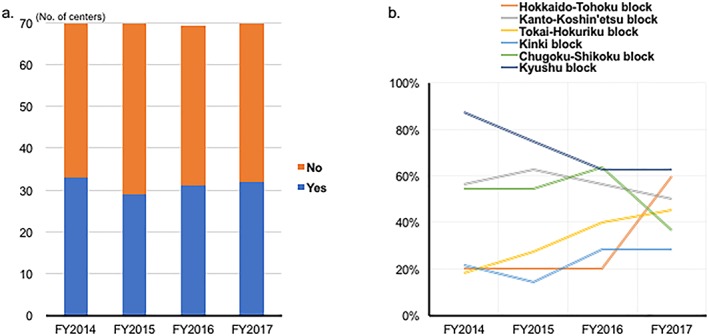

To maintain regional counseling networks, in FY2017, 32 regional core centers across Japan (46%; Fig. 3a) had been commissioned by prefectural governments to train hepatitis medical care coordinators (hereinafter, “coordinators”). The number of these trainees has increased annually. In the Kyushu, Kanto‐Koshin'etsu, and Hokkaido‐Tohoku regional blocks, the majority of regional core centers were training coordinators (Fig. 3b). Most coordinators are medical personnel and include a wide range of professionals, such as nurses, public health nurses, pharmacists, dietitians, clinical technicians, medical social workers, office workers, and treatment/life balance coordinators. Other responses included labor and social security attorneys, and patient groups. Of the 70 regional core centers, 30 (43%, FY2017) supported coordinator activities in ways other than training, including the following forms of support: (i) skill improvement seminars (23 centers); (ii) publicizing of coordinator activities (14 centers); (iii) sessions for information exchange (13 centers); and (iv) preparation of relevant manuals and other materials (5 centers).

Figure 3.

Summary of hepatitis medical care coordinators from fiscal year (FY)2014 to FY2017. (a) Number of centers conducting training. (b) Percentages of centers conducting training by regional block. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Support for patients with hepatitis

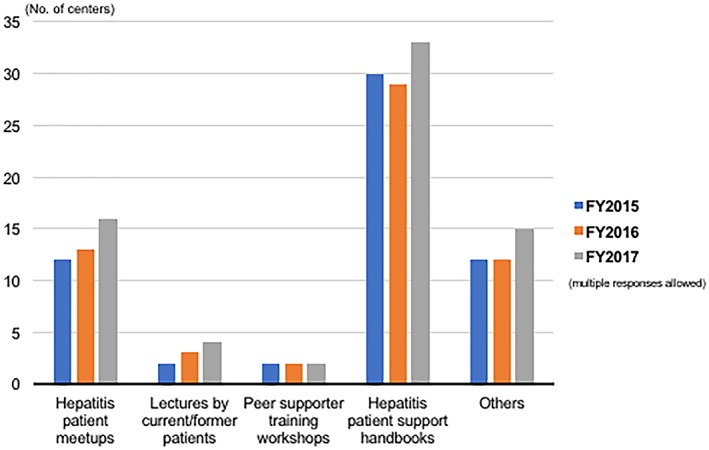

Patient support activities other than those listed above include hepatitis patient meet‐ups, lectures by current or former patients, peer supporter training workshops, and preparation/distribution of hepatitis patient support handbooks. The number of regional core centers conducting these activities is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Forms of patient support other than counseling and support services or lectures for patients and their families (fiscal year [FY]2015–2017). [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Regional core center liaison conferences and workshops

Regional core center liaison conferences

Regional core center liaison conferences (hereinafter, “liaison conferences”) comprise regional core centers along with members engaged in measures for hepatitis care from various perspectives, such as regional specialized institutions, government officials, and patient groups. The purpose of these liaison conferences is to provide a forum to discuss measures for hepatitis tailored to real‐world conditions in every prefecture in Japan. In FY2017, 19 of 70 regional core centers did not hold liaison conferences. Although most liaison conferences included government officials and specialized institutions as members, few regional core centers included patient groups or other medical professionals. The most frequent number of liaison conference meetings per year was one, followed by two, and then three or more.

Hepatitis specialist training and general medical professional training

Regional core centers hold training workshops for hepatitis specialists and general practitioners. In FY2017, hepatitis specialist training (hereinafter, “hepatitis specialization”) was conducted by 58 regional core centers an average of 3.3 times for a total of 9705 people throughout Japan. Training for general practitioners (hereinafter, “general”) was conducted by 42 regional core centers an average of 3.8 times for a total of 7137 people throughout Japan. In both types of training, the most common topic was the latest therapies and pharmaceuticals (hepatitis specialization: 56 centers; general: 47 centers), followed by government policies, such as medical expenditure subsidies (hepatitis specialization: 36 centers; general: 30 centers) and regional hepatitis care networks (hepatitis specialization: 35 centers; general: 28 centers; multiple responses allowed).

Education

Public seminars

Public seminars have been held by roughly 90% of regional core hospitals since the system's inception, with the number of seminars held increasing over time. In FY2016, public seminars were held at 63 regional core centers (90%) an average of 1.5 times, and were attended by a total of 11 423 people nationwide.

Other educational activities

Aside from public seminars, the most common type of educational activity was posters/leaflets, followed by hepatitis care leaflets, newspaper advertisements/articles, and events/symposiums. Other activities included dissemination of information through websites and social media, traveling liver disease seminars, and hepatitis virus testing.

Alert system of hepatitis virus test‐positive patients

The MHLW Basic Guidelines for Promotion of Hepatitis Measures (MHLW Notification 278; June 30, 2016) state that medical institutions shall definitively explain the results of hepatitis virus tests (such as those conducted before surgery) and urge patients to seek consultation.5 We examined regional core center alerts for hepatitis virus‐positive patients and recommendations for testing dating back to FY2015. As of FY2017, 54 regional core centers (74%) had introduced hepatitis test‐positive alert systems using electronic medical records or had referred all test‐positive patients to departments of hepatology; this 74% figure was higher than in FY2015 (43 centers, 61%).

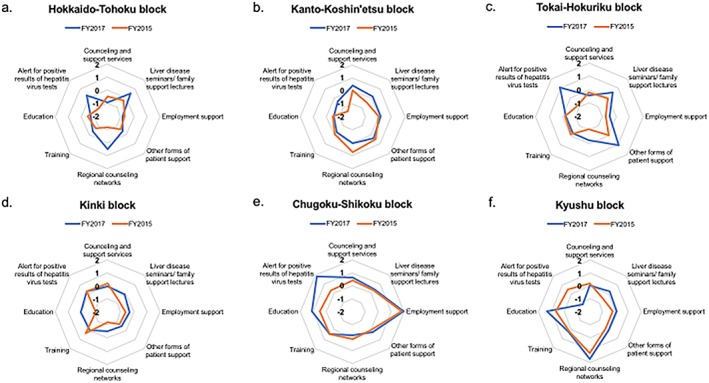

Activities of regional core centers grouped by regional block as viewed with a standardized index

Characteristics of regional blocks (FY2017 results)

In terms of employment support, the Chugoku‐Shikoku block showed a significantly higher standardized index value than the Hokkaido‐Tohoku, Tokai‐Hokuriku, and Kinki blocks (P < 0.05). Regarding regional counseling and support networks, the Kyushu block showed a significantly higher standardized index value than all other blocks, except for the Hokkaido‐Tohoku block (P < 0.05). Regarding education, the Chugoku‐Shikoku and Kyushu blocks showed a significantly higher standardized index than the other four blocks (P < 0.05). Activities by regional block are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Radar charts showing balances among activities by regional block. Blue lines: fiscal year (FY)2017, orange lines: FY2015. The formula for calculating the score (z) is z = (score – mean) / standard deviation (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1). (a) Hokkaido‐Tohoku block. (b) Kanto‐Koshin'etsu block. (c) Tokai‐Hokuriku block. (d) Kinki block. (e) Chugoku‐Shikoku block. (f) Kyushu block. [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Comparisons with FY2015 and promotion of uniform accessibility of activities

The mean standardized indices for FY2015 and FY2017 were −0.16 and 0.15, respectively; thus, the standardized index was significantly higher in FY2017 (P = 0.002). There were no activities with a standardized index significantly lower than the national average.

Discussion

During improvements to regional hepatitis care networks, there have been changes in the environment surrounding hepatitis care, such as the enhancement of measures for hepatitis and the development of novel therapies. Therefore, in March 2017, the MHLW released “Treatment of liver disease and the development of a support system for patients with liver disease” (Health Service Bureau Notice No. 0331–8; hereinafter, the “New Notice”).6 While maintaining existing basic guidelines, the New Notice presents the following novel basic ideas: (i) establishment of goals and indices; (ii) establishment of a system to facilitate easy access to testing, consultation, treatment, and follow up; (iii) patient‐oriented liver disease treatment; (iv) improvement of hepatitis treatment and promotion of uniform accessibility; and (v) suitable counseling and support for patients with hepatitis. Through care networks anchored by regional core centers, the New Notice outlines the promotion of measures for hepatitis tailored to the actual conditions of specific regions. To grasp the wide range of activities conducted by regional core centers and the changes in the environment surrounding these activities, we aggregated and analyzed results of surveys on the current status of regional core centers for the management of liver disease. We found that 71 regional core centers in every prefecture have been playing major roles not only in local hepatitis care networks, but also in the promotion of comprehensive control measures of hepatitis in Japan.

In counseling centers for liver disease, which are central to the mission of regional core centers, counseling is primarily provided by physicians who are often not engaged in full‐time counseling. Therefore, a potentially important measure for providing patients with hepatitis and their families with better counseling and information is to improve the counseling abilities of nurses and office workers. However, the nature of requests for counseling at counseling centers for liver disease has been changing; for example, in the roughly 5 years since interferon‐free therapy was approved in Japan for chronic hepatitis C, consultations regarding medical expenditure subsidies have decreased, whereas consultations regarding hepatitis‐related lawsuits and points to note in daily life have increased. Few regional core centers had independently prepared lists of anticipated questions and answers for counselors.

In 2018, the government‐funded research group entitled “Construction, application, and assessment of a counseling and support system for patients with liver disease” (principal investigator: Dr Hiroshi Yatsuhashi) led to the beginning of counseling and support systems for liver disease, which was subsequently handed over to the Hepatitis Information Center for regional core centers throughout Japan. These systems are applied to achieve the following objectives: to disseminate information on trends in the diverse array of counseling topics across the country, as well as details on challenging cases, and to alleviate the worries of patients with liver disease and improve their quality of life.

The role of a hepatitis medical coordinator is supporting patients for gaining easy access to testing, consultation, treatment, and follow up by mediating with medical institutions, administrative institutions, and relevant personnel in other regions and occupations. Because the missions of training coordinators are assigned to prefectural governments, grasping an overall picture of regional counseling and support projects is difficult from the surveys on regional core centers alone. However, as commissioned by prefectural governments, many regional core centers not only train hepatitis medical coordinators, but also support coordinators through activities such as skill improvement seminars. By working in regions familiar to them in a manner that suits their respective professions, coordinators of many different professions can foster a social foundation of understanding of hepatitis.

Employment support was offered by only a limited number of regional core centers despite the varied expansion of regional core center projects, conceivably because employment support was distinguished from other projects based on the need for collaboration with labor and social security attorneys, and other professions. We found that 94% of the regional core centers that offer employment support do so in collaboration with labor and social security attorneys or prefectural labor bureaus. However, recent advancements in diagnostic techniques and treatment methods for liver disease have led to dramatic improvements in survival of patients with viral hepatitis. Therefore, they should be given equal opportunities to gain access to treatment, by avoiding any pressure to leave their jobs, such as misconceptions about their disease or insufficient workplace support. Balancing treatment and work life is an issue not only for patients with liver disease, but also for many patients with other chronic conditions, such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, guidelines have been drafted to foster some balance between treatment and work.7 It might be necessary to expand employment support projects through disseminating information about cases by regional core centers.

Many countries are making various efforts to eliminate the hepatitis virus.8 The main target population of these measures is high‐risk groups for hepatitis C virus exposure, such as persons who inject drugs and incarcerated individuals. In addition, regarding the prevention of hepatitis B virus, the focus of timely vaccination is mainly on infants. There are few countries like Japan that implement strategy against viral hepatitis targeting the general population. The development of regional hepatitis care networks, a system unique to Japan, resulted from such strategic differences. Regional core centers serve a wide variety of roles in establishing measures for the treatment of hepatitis in their regions; over time, the scope of these projects has been expanding. Every regional block differs in the extent of balance achieved among its projects. For instance, in the western part of Japan, where the prevalence of hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus is relatively higher compared with that in other regions, the score regarding patient support was higher. Meanwhile no block showed significantly less activity than the national average in any project, indicating that support and treatment for hepatitis is uniformly accessible throughout Japan. To fulfill the diverse roles expected of them, regional core centers require further strengthening of hepatitis care networks that include specialized medical institutions, primary care physicians, and local governments; as well as collaboration with other professions and groups.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Regional blocks of core centers for liver disease in Japan.

Figure S2. Regional area that is governed by each Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare.

Table S1. Regional core centers for liver disease in Japan

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all those involved in community‐based hepatitis measures at the 71 regional core centers across Japan, medical personnel at specialized institutions or those involved in medical care for hepatitis, those responsible for related matters in prefectural and municipal governments, hepatitis medical care coordinators, and hepatitis patients and their families. This study was conducted as a part of the Policy Research for Hepatitis Measures of Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan and was supported by Health, Labour and Welfare Sciences Research Grants in Japan (Grant number H29‐kansei‐shitei‐001). This work was also supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Research from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Grant number 29‐shi‐2002).

Setoyama, H. , Korenaga, M. , Kitayama, Y. , Oza, N. , Masaki, N. , and Kanto, T. (2020) Nationwide survey on activities of regional core centers for the management of liver disease in Japan: Cumulative analyses by the Hepatitis Information Center 2009–2017. Hepatol Res, 50: 165–173. 10.1111/hepr.13458.

Conflict of interest: Tatsuya Kanto received honoraria from Gilead Sciences and MSD. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Oza N, Isoda H, Ono T, Kanto T. Current activities and future directions of comprehensive hepatitis control measures in Japan: The supportive role of the Hepatitis Information Center in building a solid foundation. Hepatology Res 2017; 47: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Health, Labour and Welfare Statistics Association . Part 3: Trends in health care. Chapter 3: Measures against infectious diseases. Trends in Public Health 2016/2017 (Special Issue of the Journal of Health and Welfare Statistics) 2016, p. 702 (in Japanese)

- 3. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Comprehensive Promotion of Hepatitis Measures: Maintenance of Hepatitis Care Networks. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-10905750-Kenkoukyoku-Kanentaisakusuishinshitsu/0000155091.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 4. Hepatitis Information Center . Surveys on the Current Status of Regional Core Centers for the Treatment of Liver Disease (FY 2009–2017). Available at: http://www.kanen.ncgm.go.jp/content/state_of_the_present_from_h21_to_h29.pdf.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 5. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Comprehensive Promotion of Hepatitis Measures: Basic Guidelines for Promotion of Hepatitis Measures. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou09/pdf/hourei-27.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 6. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Comprehensive Promotion of Hepatitis Measures: Treatment of Liver Disease and the Development of a Support System for Patients with Hepatitis. Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou09/pdf/hourei-170404-2.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 7. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . The Balance Between Treatment and Work. Available at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000115267.html. Accessed March 1, 2019. (in Japanese)

- 8. Popping S, Bade D, Boucher C et al The global campaign to eliminate HBV and HCV infection: International Viral Hepatitis Elimination Meeting and core indicators for development towards the 2030 elimination goals. J Virus Erad 2019; 5: 60–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Regional blocks of core centers for liver disease in Japan.

Figure S2. Regional area that is governed by each Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare.

Table S1. Regional core centers for liver disease in Japan