Abstract

Strategies to reduce, halt, and reverse global declines in marine biodiversity are needed urgently. We reviewed, coded, and synthesized historical and contemporary marine conservation strategies of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation in British Columbia, Canada to show how their approaches work. We assessed whether the conservation actions classification system by the Conservation Measures Partnership was able to encompass this nation's conservation approaches. All first‐order conservation actions aligned with the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation's historical and contemporary marine conservation actions; hereditary chief management responsibility played a key role. A conservation ethic permeates Kitasoo/Xai'xais culture, and indigenous resource management and conservation existed historically and remains strong despite extreme efforts by colonizers to suppress all indigenous practices. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais's embodiment of conservation actions as part of their worldview, rather than as requiring actions separate from everyday life (the norm in nonindigenous cultures), was missing from the conservation action classification system. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais are one of many indigenous peoples working to revitalize their governance and management authorities. With the Canadian government's declared willingness to work toward reconciliation, there is an opportunity to enable First Nations to lead on marine and other conservation efforts. Global conservation efforts would also benefit from enhanced support for indigenous conservation approaches, including expanding the conservation actions classification to encompass a new category of conservation or sacredness ethic.

Keywords: first nations management, great bear rainforest, indigenous community conserved areas, indigenous protected areas, indigenous stewardship, marine protected areas, administración indígena, áreas conservadas por comunidades indígenas, áreas marinas protegidas, áreas protegidas indígenas, bosque lluvioso Great Bear, gestión de las Primeras Naciones, 原住民保护地, 第一民族管理, 原住民管理, 大熊雨林, 海洋保护地, 原住民保留地

Short abstract

Article impact statement: Indigenous marine conservation remains strong, despite colonial efforts to undermine indigenous governance, and should be supported.

Estrategias Indígenas Contemporáneas de Conservación Marina en el Pacífico Norte

Resumen

Se necesitan urgentemente estrategias para reducir, detener y revertir las declinaciones mundiales de biodiversidad marina. Revisamos, codificamos y sintetizamos estrategias históricas y contemporáneas de conservación marina realizadas por la Primera Nación Kitasoo/Xai'xais en la Columbia Británica, Canadá, para demostrar cómo funcionan sus estrategias. Evaluamos si el sistema de clasificación de acciones de conservación hecho por la Asociación de Medidas de Conservación era capaz de englobar las acciones de conservación de esta nación. Todas las acciones de conservación de primera orden se alinearon con las acciones históricas y contemporáneas de conservación marina realizadas por la Primera Nación Kitasoo/Xai'xais; en las cuales la responsabilidad de gestión del jefe hereditario jugó un papel de suma importancia. Una ética de conservación permea la cultura Kitasoo/Xai'xais, y la conservación el manejo indígena de los recursos han existido históricamente y permanecen fuertes a pesar los esfuerzos extremos de los colonizadores por eliminar todas las prácticas indígenas. La encarnación de las acciones de conservación de los Kitasoo/Xai'xais como parte de su cosmogonía, en lugar de requerir acciones separadas de la vida diaria (la norma para las culturas no indígenas), no estaba incluida en el sistema de clasificación de las acciones de conservación. Este pueblo es uno de los tantos grupos étnicos que se encuentran trabajando para revitalizar su gobernanza y sus autoridades de manejo. Con la declaración de disposición del gobierno canadiense por trabajar hacia la reconciliación, existe una oportunidad para permitirle a las Primeras Naciones liderar los esfuerzos de conservación marina, así como otros tipos de conservación. Los esfuerzos globales de conservación también se beneficiarían de un mayor apoyo a las estrategias indígenas de conservación, incluyendo la expansión de la clasificación de las acciones de conservación para que engloben una categoría nueva de conservación o de ética sagrada.

摘要

制定减少、遏制及逆转全球海洋生物多样性下降的保护策略已刻不容缓。我们回顾、解译并整合了加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚省 Kitasoo/Xai'xais 印第安人的海洋保护策略的历史和现状, 以展示他们的保护方法的有效性。我们评估了《保护措施伙伴关系》的保护行动分类体系是否囊括了印第安人所有保护措施, 发现所有一级保护行动都与 Kitasoo/Xai'xais 印第安人历史和当代的海洋保护行动相符, 其中世代相袭的酋长管理职责发挥了关键作用。保护伦理贯穿着 Kitasoo/Xai'xais 文化, 原住民的资源管理和保护久已有之, 尽管其行动受到殖民者的极力压制, 然而这些管理和保护仍然有很强的作用。保护行动是 Kitasoo/Xai'xais 民族世界观的一部分, 而不是与日常生活 (非原住民的文化规范) 相分离的被动行为, 这在保护行动分类系统中没有体现。 Kitasoo/Xai'xais 是致力于振兴其统治和管理权力的诸多原住民民族之一。随着加拿大政府已公开表示愿意共同努力达成和解, 我们也有机会让印第安人在海洋及其它保护工作中发挥领导作用。全球保护工作将得益于来自原住民保护方法的支持, 包括扩展保护行动分类以纳入新的保护或神圣伦理。【翻译: 胡怡思; 审校: 聂永刚】

Introduction

Declines in marine biodiversity and wilderness are occurring globally and regionally (Jones et al. 2018) due to threats such as overfishing, climate change, and pollution (Halpern et al. 2015). Many countries committed to improving biodiversity conservation by supporting the Convention on Biological Diversity's Aichi targets and sustainable development goals (CBD 2010; Griggs et al. 2013). Many nations recognize the need to align conservation with indigenous peoples’ rights (Ban & Frid 2018) and signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UN General Assembly 2007).

To create a common understanding of conservation strategies and threats, Salafsky et al. (2008) developed a classification of conservation strategies. The Conservation Measures Partnership (CMP) (2018) updates this comprehensive classification. Actions are classified into restoration and stress‐reduction actions, for example, water and species management, behavioral change, and threat‐reduction actions, such as awareness raising, law enforcement, and incentives (CMP 2018). This classification is the only such system used globally and has been implemented widely because it is useful in assessing and identifying gaps in conservation actions (Schwartz et al. 2012; Bower et al. 2018; Redford et al. 2018). Given the broad application of the CMP and the increasingly urgent need to recognize indigenous peoples’ conservation practices, it is important to ensure the classification captures all conservation practices.

Indigenous marine conservation and management practices (hereafter indigenous conservation) vary globally and support local ecosystems, customs, and sustainable use (Lepofsky & Caldwell 2013; Ban & Frid 2018; Berkes 2018). Some indigenous conservation strategies are similar across cultures, including customary tenure areas where rights of extraction, management, and access to the ocean belong to specific people or entities (e.g., village, chief, or family) (Cinner & Aswani 2007; Jupiter et al. 2014). Indigenous conservation practices are commonly underpinned by worldviews that embed respect for all living beings and guide actions as contained within stories, customs, and traditions (Lepofsky & Caldwell 2013; Ban & Frid 2018; Berkes 2018). Although the conservation literature highlights the importance of indigenous conservation (e.g., Drew 2005), many countries continue to displace indigenous peoples in the name of conservation (e.g., Lunstrum & Ybarra 2018).

We examined whether the CMP's conservation actions classification captures indigenous conservation practices. We used the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation's strategies through time as an example. We formed a partnership between the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation and University of Victoria researchers to conduct the study. The intent was not to justify or rationalize indigenous conservation practices in Western terms. Rather, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais wanted to showcase their historical and contemporary conservation strategies by using a scheme recognized by practitioners regionally and globally so that their approaches can be better recognized and supported in ongoing marine planning and protection processes in the region. This work is part of a broader effort by Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation to revitalize their governance and practices.

Methods

Case Study

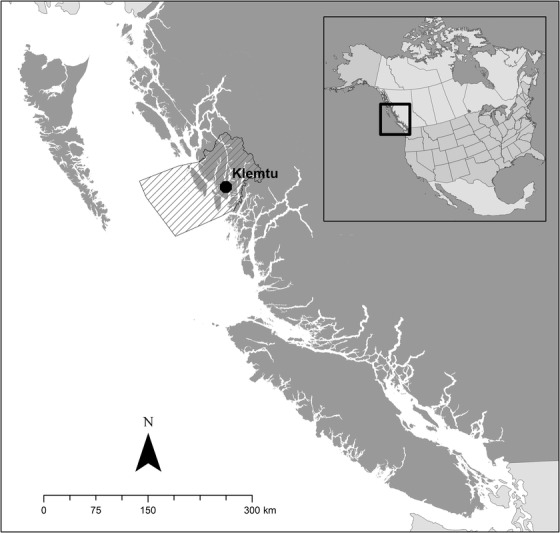

The Kitasoo/Xai'xais people call the central coast of British Columbia, Canada, their home (Fig. 1). The Kitasoo and Xai'xais lived in villages and seasonal camps throughout their territory. Kitasoo traditionally resided in coastal areas, and Xai'xais primarily resided in inlets (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation 2011). Around 1875, the 2 groups joined together in Klemtu and are now collectively known as the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation. Historically, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais were highly dependent on the land and ocean for survival and trade (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation 2011). The hereditary chieftainship system, potlatch ceremonies, and the seasonal food and preservation cycle governed resource ownership and extraction, ensuring sustainable use of marine resources for thousands of years (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation 2011). The Kitasoo/Xai'xais say, sustainable “means the wealth of the forests, fish, wildlife and the complexity of all life will be here forever…[and] …we will be here forever” and that “we need to protect, manage and enhance the resources and our culture…to ultimately protect our heritage” (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation and University of Victoria 2018).

Figure 1.

Study area in Canada (hatching, claimed territory of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation).

Past and ongoing colonization of many coastal regions resulted in rapid and drastic changes in indigenous management practices because they were criminalized. Indigenous peoples were forcibly relocated, and declines of marine species due to commercialization contributed to changed access to indigenous management practices (Harris 2002; Ommer 2007). In Canada, the Indian Act and associated policies prohibited First Nations’ cultural practices, such as potlatches (gift‐giving feasts, a crucial governance mechanism); banned, for example, indigenous fish traps and weirs that allowed selective harvest of salmon (Atlas et al. 2017); confined indigenous people to reservations; and forcibly placed children in boarding schools (Harris 2002; Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2015). These policies, and related ongoing legacies, severely diminished the well‐being of First Nations and disrupted indigenous knowledge and management practices (Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2015).

Information and Analyses

The Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation developed their Cultural Heritage Project to revitalize their governance and practices by documenting their laws, governance, practices, and stories. They compiled all available documented information about the Kitasoo/Xai'xais, including historical documents (e.g., journals of explorers and anthropologists), traditional stories, and recordings and transcripts of interviews, into the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Heritage Database. Kitasoo/Xai'xais researchers searched their own, regional, national, and international archives (e.g., British Columbia Archives, Library and Archives Canada, American Philosophical Society) and placed a copy of all sources in the Heritage Database. Kitasoo/Xai'xais researchers interviewed elders to document their memories of indigenous laws and governance practices and also used a method developed by Friedland and Napoleon (2015) to derive Kitasoo/Xai'xais legal principles from the material.

We accessed and reviewed all sources (∼2000 entries as of May 2018) in the Heritage Database to identify and summarize those that pertained directly to marine governance (∼100 entries). We used these to articulate Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine governance and management through a community‐based process (i.e., iterative review by the community, hereditary chiefs, and elders) and 6 semistructured interviews with elders to fill gaps relating to the marine environment specifically (University of Victoria ethics protocol 17–211). This process is described in Ban et al. (2019). We used the specifics of Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine governance and management detailed in an unpublished report (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation and University of Victoria 2018) to code their conservation strategies for the CMP Actions Classification (Salafsky et al. 2008). First we coded for historical and contemporary Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation categories, and then we coded strategies that did not fit the classification. We considered the contemporary period as time since European colonial and settler influence became dominant.

The Heritage Database, on which our research is based, although impressive, is incomplete due to efforts by the government to undermine indigenous languages, laws, and cultures. Thus, we focused on documented knowledge about Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine governance, but we recognize this knowledge is not comprehensive. Hence, no data do not mean an aspect of marine conservation was not practiced, but rather that we did not have information about it. Similarly, the Heritage Database focuses primarily on documenting historical governance. While many of the interviews contained in the database comment on recent events, and there was less information on contemporary than on historical Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation actions. Contemporary conservation strategies fall within the lived experience of Kitasoo/Xai'xais stewardship staff, and in particular one of us (D.N.) as stewardship director. We thus augmented contemporary conservation practices with our experiences and conversations with Kitasoo/Xai'xais resource stewardship staff. For each of the categories of conservation actions, we assessed whether relevant actions were documented in the Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine governance and management report (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation and University of Victoria 2018) and, if so, summarized them while ensuring that confidential information was not disclosed (e.g., names of hereditary chiefs, and specific places).

Results

All first‐order categories of CMP conservation actions classification system (2018) were applicable for historical and contemporary Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation practices (Table 1). Historically and contemporaneously a recurring theme was the paramount importance of conservation to sustain use of marine ecosystems. Kitasoo/Xai'xais stewardship and conservation did not cease as colonizers attempted to deconstruct indigenous governance. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais asserted their management authority—especially for conservation—and applied conservation practices evolved through time. We report highlights for first‐order conservation action of the classification: land and water management; species management; awareness raising; law enforcement and prosecution; livelihood, economic, and moral incentives; conservation designation and planning; legal and policy frameworks, research and monitoring; and institutional development. Although we focused on linking Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation practices to first order actions, many of their practices entail >1 category (Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Historical and contemporary use of categories in the Conservation Measures Partnership Conservation Actions Classification (version 2.0) by the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation

| Categories of first‐ and second‐order conservation action* | Historical | Contemporary |

|---|---|---|

| Target restoration and stress‐reduction actions | ✔ | ✔ |

| land and water management | ✔ | ✔ |

| site and area stewardship | ✔ | ✔ |

| ecosystem and natural‐process re‐creation | ✔ | ✔ |

| species management | ✔ | ✔ |

| species stewardship | ✔ | ✔ |

| species reintroduction & translocation | ✔ | |

| ex situ conservation | ||

| Behavioral change and threat‐reduction actions | ✔ | ✔ |

| awareness raising | ✔ | ✔ |

| outreach & communications | ✔ | ✔ |

| protests & civil disobedience | ✔ | |

| law enforcement & prosecution | ✔ | ✔ |

| detection & arrest | ✔ | ✔ |

| criminal prosecution & conviction | ✔ | ✔ |

| noncriminal legal action | ✔ | |

| Livelihood, economic, & moral incentives | ✔ | ✔ |

| linked enterprises and alternative livelihoods | ✔ | ✔ |

| better products and management practices | ✔ | ✔ |

| market‐based incentives | ||

| direct economic incentives | ||

| nonmonetary values | ✔ | ✔ |

| Enabling condition actions | ✔ | ✔ |

| conservation designation & planning | ✔ | ✔ |

| protected area designation or acquisition | ✔ | ✔ |

| easements and resource rights | ✔ | ✔ |

| land‐ and water‐use zoning and designation | ✔ | ✔ |

| conservation planning | ✔ | |

| site infrastructure | ✔ | ✔ |

| legal and policy frameworks | ✔ | ✔ |

| laws, regulations, and codes | ✔ | ✔ |

| policies and guidelines | ✔ | ✔ |

| research and monitoring | ✔ | ✔ |

| basic research and status monitoring | ✔ | ✔ |

| evaluation, effectiveness measures, and learning | ✔ | ✔ |

| education and training | ✔ | ✔ |

| formal education | ✔ | ✔ |

| training and individual capacity development | ✔ | |

| institutional development | ✔ | ✔ |

| internal organizational management and administration | ✔ | |

| external organizational development and support | ||

| alliance and partnership development | ✔ | ✔ |

| financing conservation | ✔ |

*Second‐order actions are subordinate to first order in the column.

Land and Water Management

Historically and today hereditary chiefs are stewards for the territory held under their name to ensure these areas are used sustainably. Historically, people dispersed to seasonal spring and summer camps to use resources. Everyone using resources had stewardship obligations (e.g., disable fish traps when not in use). Access to the territory in the short term to allow recovery of species and in the long‐term through agreements with neighboring nations is regulated.

Hereditary chiefs use their authority to oppose non‐Kitasoo/Xai'xais decisions imposed on them. For example, in the 2010s the Kitasoo/Xai'xais created their own herring management plan (Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation 2019), and members protested against the commercial herring roe fishery, reacting to concerns about declines in herring populations and unstainable federal fisheries management. When Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) disclosed new fishing regulations in Kitasu Bay for community members, the chiefs did not accept them and protested. Hereditary chiefs and community members practice their authority over harvesting decisions, even though the Canadian government provides DFO with sole jurisdiction to manage fisheries.

Historically, conservation emphasized long‐term sustainable use, such that ecosystem and natural‐process creation or re‐creation was not necessary. Respect, reciprocity, intergenerational knowledge, and interconnectedness are foundational to Kitasoo/Xai'xais law, inform all marine governance processes, and are essential to how Kitasoo/Xai'xais interact with others and the environment. Hereditary chiefs ensure conservation of resources by making decisions about harvesting. Today, Kitasoo/Xai'xais continue to view conservation and sustainability as essential, actively oppose unsustainable practices, and are involved in ecosystem restoration projects.

Species Management

Hereditary chiefs are responsible for conservation and management of all species. Continual use of resources is a way of maintaining and displaying rights to resource claims. Selective harvesting is paramount (e.g., harvesting abundant species and selecting for specific characteristics and sizes). Today, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Stewardship Authority (KXSA) is involved in species conservation and management. The Fisheries Committee stipulates fisheries openings and gathers catch data. Individual Kitasoo/Xai'xais help ensure sustainability by, for example, moving small captured crabs to places where they have been depleted.

Awareness Raising

The need to raise awareness about conservation was less paramount in the past, when everyone relied on the oceans for their well‐being. Important events continue to be communicated during potlaches, where guests serve as witnesses. Historically and currently, oral story telling is a key aspect of transferring knowledge, laws, and principles among generations. In addition to traditional communication methods, KXSA uses modern tools (e.g., quarterly newsletter, social media, experiential learning, and art).

In contemporary Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation, protests and civil disobedience are practiced to obtain recognition of legitimate authority over their territory. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais have also used indigenous laws to close bays to herring and crab fishing and will risk arrest to enforce those laws (not yet recognized by the Canadian government) (Frid et al. 2016).

Law Enforcement and Prosecution

Historically, the Kitasoo met at Disju (an important gathering place) to resolve resource and territorial disputes within and beyond the nation. For individuals there were clear consequences for acting irresponsibly (e.g., unsustainable harvest of species), including loss of access and expulsion from the territory. Now, Kitasoo/Xai'xais, especially harvesters, report illegal fishing activities to Kitasoo/Xai'xais leadership. The Guardian Watchmen (a coast‐wide program in which the Kitaoo/Xai'xais participate) are paid to patrol the territory, observe, and ensure compliance with rules. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais Guardian Watchmen do not yet have the legal authority to issue citations or make arrests, but they carefully monitor the territory and collect evidence. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais have participated in legal action to safeguard their territory (e.g., against Fisheries and Oceans Canada for managing sea cucumber unsustainably). Hereditary chiefs and elders work with KXSA to enforce harvesting laws. Because elders know the history of hereditary chief names and ownership of places is associated with those names given to people, they can assist with harvesting laws and land and sea ownership‐dispute resolution.

Livelihood, Economic, and Moral Incentives

The evolution of fishing technologies, coupled with strict harvesting protocols, led to extensive systems of fish traps and weirs in the territory that facilitated selective harvesting. Kitasoo/Xai'xais have a deep relationship with the ocean (it is their primary source of sustenance) and everything in it is considered sacred. This is highlighted in many stories and customs. For example, when the first catch of the season was brought in, the chief would hold a feast to celebrate and call attention to his property and harvest rights. Today, the condition of the ocean remains closely tied to people's well‐being, and Kitasoo/Xai'xais continue to support environmentally responsible livelihoods. In particular, Klemtu has become a world‐class tourism destination for people seeking to see the spirit bear, a genetic variant of the black bear (Ursus americanus kermodei), and the Spirit Bear Lodge provides employment for Kitasoo/Xai'xais. Commercial ventures in Kitasoo/Xai'xais territory (e.g., ecotourism and fish farming) are carefully managed, guided by Kitasoo/Xai'xais principles, to develop best practices, minimize environmental damage, and provide livelihood opportunities for Kitasoo/Xai'xais.

Conservation Designation and Planning

Hereditary Chiefs are responsible for long‐term conservation. Specific restrictions were established for seasons and places (e.g., harvesting eulachon [Thaleichthys pacificus] in a specific river was not allowed because it had the first run of the year).

Since colonization, and especially over the past 50 years, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais fought (and continue to) to establish resource management rights recognized by Canadian provincial and federal governments (e.g., establishment of indigenous protected areas and use of Kitasoo/Xai'xais laws to close bays to commercial and recreational crabbing) (Frid et al. 2016). The Kitasoo/Xai'xais actively engage in conservation planning (e.g., community's marine‐use plan, regional Marine Plan Partnership, and planning the Northern Shelf Bioregion marine protected area). A patrol hut was built at Mussel Inlet to allow Guardian Watchmen a presence there. A new stewardship building was recently completed to enhance learning and research.

Legal and Policy Frameworks

Kitasoo/Xai'xais are expected to treat the marine environment in a way that upholds Kitasoo/Xai'xais underlying principles and practices. They believe the ocean has a right to be respected and protected. There were historic intertribal agreements about uses and boundaries based on respect and reciprocity. The protocol to harvest resources in somebody else's territory is to ask permission of whoever holds rights to the area. Marine territory rights, validated through potlatches, are “…established and formalized by means of demonstration of and claims to such rights through certain names, crests, and songs.” Respect is a cultural norm, demonstrated by taking only what one needs, not killing for fun, fully using what is harvested, and not overharvesting. For example, when colonial law encouraged the killing of seals and wolves, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais did not participate. Today, Kitasoo/Xai'xais work with neighboring nations on resource management issues, for example, through the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance. The KXSA provides policies and reviews application for permits (by nonindigenous users) in the territory.

Research and Monitoring

Historically, Kitasoo/Xai'xais acted on observations to regulate harvesting in the areas for which each hereditary chief was responsible. Although this was not research and monitoring as framed today, presence on the water, and adaptive management and evolution of management practices, ensured conservation and sustainable use.

Today the Kitasoo/Xai'xais are leading and partnering on numerous research projects, some of which are aimed at assessing the effectiveness of management measures (e.g., Kitasoo/Xai'xais Guardian Watchmen carry out biological monitoring of species and interview knowledge holders). The Kitasoo/Xai'xais Cultural Heritage Project is an important research endeavor.

Education and Training

In the past, formal education was provided as guidance from elders and knowledge holders. The principle of intergenerational knowledge relies on the transfer of knowledge between generations, which depends on teaching. Parents, grandparents, and elders teach young people about marine governance principles and the proper way to act. Elders continue to play a crucial role in intergenerational knowledge transfer.

More recently, the Guardian Watchmen program trains staff to be stewards of the territory. The KXSA provides training and capacity‐development opportunities year round (e.g., first aid, whale disentanglement workshops). The summer programs Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards and Sua Youth Cultural Group for high school students provide education in resource stewardship and cultural practices.

Institutional Development

The KXIRA provides technical advice and support for effective decision making by the Kitasoo/Xai'xais community and its leadership. They work with neighboring nations to promote sustainable management and conservation of the central coast and partner with universities, not‐for profit organizations, and governments on resource management and conservation issues. Institutional development, as conceptualized today, did not exist in the past, although Disju was the gathering place where leaders met and partnerships were formed.

Conservation Actions Not Present

Not all second‐order conservation actions (CMP 2018) were relevant for historical and contemporary Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation. Ex situ conservation, market‐based incentives, direct economic incentives, and external organizational support and development were not mentioned in historical or contemporary Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation. No zoos or seedbanks exist in Kitasoo/Xai'xais territory; thus, ex situ conservation is not relevant. Cultural values dominate economic ones—although the latter also matters—hence, neither market‐based nor economic incentives have as yet been employed. External organizational support and development was not applicable in the past and was not mentioned for contemporary times.

Missing Elements of Current Classification

The classification captured many aspects of Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation practices, but missed the important role Kitasoo/Xai'xais worldview and legal principles play in engraining a conservation ethic that permeates all aspects of being and acting. The belief that the ocean is sacred is embedded in practices that ensure the well‐being of the ocean and people, and showing respect is an essential component of how Kitasoo/Xai'xais act with regard to other beings. An example is the First Salmon Feast, a celebration for the return of salmon in May. When potlatches were banned, Kitasoo/Xai'xais still celebrated this important event but concealed under the Salmon Queen, and later, the May Queen celebrations.

Relationships are key in the Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation ethic, and marine (and other) species are considered relatives. This close relationship can be seen in the names of people, including hereditary chief names that refer to marine species. The sacredness of the ocean and its inhabitants are considered kin, which results in a conservation ethic that permeates everyday life. These are not emphasized in the conservation classification; instead, they are relegated to “developing religious or cultural arguments for conservation” (CMP 2018).

Discussion

The CMP (CMP 2018), the most prominent globally recognized classification of conservation actions (Schwartz et al. 2012; Bower et al. 2018; Redford et al. 2018), captured many of the conservation actions used by the Kitasoo/Xai'xais people, yet also fell short in some aspects. Matching Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation actions to the CMP conservation action classification illustrated that strategies used by the Kitasoo/Xai'xais are broader than the classification system and encompass multiple actions across categories. For example, hereditary chiefs are responsible for stewardship of specific areas, ecosystem processes, species stewardship, resolving disputes, among others. There is thus a danger that application of the classification may make indigenous conservation actions appear as distinct pieces when they are part of the cultural fabric of stewardship where all conservation actions are connected. There are pros and cons to using a classification. One the one hand, a classification of conservation actions can greatly facilitate the work of conservation practitioners. On the other, one classification may never fully encompass all cultural manifestations of conservation. We attempted to take a middle ground and expand the view of conservation by assessing the classification in a different cultural context.

A crucial gap we identified in the conservation action classification was related to a conservation ethic (Leopold 1933). A conservation ethic permeates Kitasoo/Xai'xais culture, which has many similarities to First Nations in British Columbia, and has been documented for many other indigenous peoples (e.g., Johannes 2002; Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina 2016; Simpson 2017; Friedlander 2018). Furthermore, indigenous resource management and conservation existed in the past (Lepofsky & Caldwell 2013) and continues strongly, despite efforts by colonizers to suppress all indigenous practices (Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2015). We found that this conservation ethic is so strong that individuals risked severe punishment to maintain it (e.g., imprisonment). This aspect of conservation—its embodiment in all actions as part of the worldview rather than its conceptualization as a separate activity—is also what we found missing from the conservation action classification (CMP 2018). We suggest that a high‐level conservation action be added as “sacredness ethic” or “conservation ethic” to recognize activities that embody conservation in the everyday (Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina 2016). In this sacredness ethic, “taking of resources is viewed as an exchange and a privilege that comes with stewardship responsibilities,” which contrasts with the currently prevailing commodity ethic that maximizes profits (Kealiikanakaoleohaililani & Giardina 2016). An improved conservation classification system could be used, at the request of indigenous peoples, to help translate and make visible indigenous governance to nonindigenous conservation practitioners. Another tactic would be to take one or more indigenous conservation approaches as a starting point to develop a different classification and then see how it compares.

As part of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais's efforts to revitalize their indigenous governance and practices, the results of this study are helping instill a sense of pride in Kitasoo/Xai'xais's past and ongoing cultural conservation practices and showed that many of the conservation actions applied were relevant in the past and are relevant today. The strength of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation ethic today is remarkable given colonial attempts to undermine all aspects of indigenous culture and practices (Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2015). Their governance mechanisms and practices adapted to the changes, went underground, and laid dormant. The Kitasoo/Xai'xais Cultural Heritage Project, which includes this work as a small piece thereof, is part of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais Nation's attempt to reinvigorate their governance. We contend that other indigenous peoples likewise have sacredness ethics and that their conservation actions adapted and persist despite past and ongoing attempts of colonial governments to undermine them. Documenting indigenous conservation strategies, where desired and led by indigenous peoples, is one avenue for cultural and governance resurgence in the domain of conservation. With the Canadian government espousing its intention to move toward reconciliation with indigenous peoples, there is an urgent opportunity for the federal and provincial governments to support and recognize indigenous authority over resource management, including in the ocean (Ban & Frid 2018).

Our case study also highlighted similarities, and some differences, with other documented indigenous conservation practices. In particular, a key aspect of Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine conservation—the stewardship responsibilities of hereditary chiefs—is a form of customary marine tenure. Customary marine tenures have been described and studied fairly extensively in the tropical Pacific (e.g., Cinner 2005; Jupiter et al. 2014), but have received less attention in the northern Pacific Ocean (but see Trosper 2009; Lepofsky & Caldwell 2013). Yet unlike some other regions, where conservation has been described as an unintended by‐product of customary marine tenure systems (Cinner & Aswani 2007), we found strong evidence that conservation is an explicit and essential component of the responsibility of hereditary chiefs for their areas, today and in the past.

The main limitation of our research—likely applicable for similar efforts elsewhere—was that gaps exist in knowledge about past Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation practices and protocols. Our account of Kitasoo/Xai'xais conservation strategies is thus also incomplete, yet we had to synthesize and simplify the rich descriptions of known strategies because of space restriction and confidentiality concerns. Still, we provide an overview of the extent to which conservation was, and is, a focal point. We focused on marine conservation because the Canadian government separates marine from terrestrial jurisdictions, but in the Kitasoo/Xai'xais worldview, land and sea are a continuum.

Although the importance of indigenous peoples is well recognized in the conservation literature (e.g., Drew 2005), it nevertheless remains important to highlight case studies such as that of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais. Colonial governments continue to undermine attempts by indigenous governments to manage their territories (Colchester 2004; Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2015), and in some cases indigenous peoples continue to be displaced from their territories in the name of conservation (Lunstrum & Ybarra 2018). Thus, raising awareness and providing support for indigenous conservation strategies and their authority to govern marine resources is crucial for the future of both indigenous peoples and biodiversity. If even more areas than at present can be managed by indigenous people (Garnett et al. 2018), the future would be brighter for indigenous peoples and biodiversity (Ban et al. 2018).

Supporting information

Details of Kitasoo/Xai'xais historical and contemporary conservation strategies as categorized into the CMP Conservation Actions (Appendix S1) are available online. The authors are solely responsible for the content and functionality of these materials. Queries (other than absence of the material) should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to members of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation who have generously shared their time and knowledge with us for this project. The authors thank all the Kitasoo/Xai'xais knowledge holders who contributed to the broader Heritage Project. The authors also thank the Kitasoo/Xai'xais leadership for supporting this project and Resource Stewardship past and present employees. The authors thank C. McKnight for his research assistant support, S. Harrison for helpful comments on the manuscript, and the University of Victoria Indigenous Law Research Unit for introducing their method at a workshop. Funding was provided by the Tides Canada Foundation ‐ British Columbia Marine Planning Fund, the University of Victoria Lansdowne Award, and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council.

Article impact statement: Indigenous marine conservation remains strong, despite colonial efforts to undermine indigenous governance, and should be supported.

Literature Cited

- Atlas WI, Housty WG, Béliveau A, DeRoy B, Callegari G, Reid M, Moore JW. 2017. Ancient fish weir technology for modern stewardship: lessons from community‐based salmon monitoring. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 3:1341284. [Google Scholar]

- Ban NC, Frid A. 2018. Indigenous peoples' rights and marine protected areas. Marine Policy 87:180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ban NC, Frid A, Reid M, Edgar B, Shaw D, Siwallace P. 2018. Incorporate indigenous perspectives for impactful research and effective management. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2:1680–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban NC, Wilson E, Neasloss D. 2019. Strong historical and ongoing indigenous marine governance in the northeast Pacific Ocean: a case study of the Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation. Ecology and Society 24:10. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes F. 2018. Sacred ecology. 4th edition Routledge, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bower SD, et al. 2018. Making tough choices: picking the appropriate conservation decision‐making tool. Conservation Letters 11:e12418. [Google Scholar]

- Cinner J. 2005. Socioeconomic factors influencing customary marine tenure in the Indo‐Pacific. Ecology and Society 10:36. [Google Scholar]

- Cinner JE, Aswani S. 2007. Integrating customary management into marine conservation. Biological Conservation 140:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Colchester M. 2004. Conservation policy and indigenous peoples. Environmental Science & Policy 7:145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Conservation Measures Partnership (CMP) . 2018. CMP conservation actions classification v 2.0. CMP, Washington, D.C. Available from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1i25GTaEA80HwMvsTiYkdOoXRPWiVPZ5l6KioWx9g2zM/edit#gid=874211847 (accessed December 2018).

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity) . 2010. Aichi biodiversity targets. CBD, Montreal, Canada: Available from http://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/ (accessed July 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Drew JA. 2005. Use of traditional ecological knowledge in marine conservation. Conservation Biology 19:1286–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Frid A, McGreer M, Stevenson A. 2016. Rapid recovery of dungeness crab within spatial fishery closures declared under indigenous law in British Columbia. Global Ecology and Conservation 6:48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Friedland H, Napoleon V. 2015. Gathering the threads: developing a methodology for researching and rebuilding indigenous legal traditions. Lakehead Law Journal 1:16–44. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander AM. 2018. Marine conservation in Oceania: past, present, and future. Marine Pollution Bulletin 135:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett ST, et al. 2018. A spatial overview of the global importance of Indigenous lands for conservation. Nature Sustainability 1:369–374. [Google Scholar]

- Griggs D, et al. 2013. Policy: sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 495:305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern BS, et al. 2015. Spatial and temporal changes in cumulative human impacts on the world's ocean. Nature Communications 6:7615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C. 2002. Making native space: colonialism, resistance, and reserves in British Columbia. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes RE. 2002. Did indigenous conservation ethic exist? SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin 14:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jones KR, et al. 2018. The location and protection status of Earth's diminishing marine wilderness. Current Biology 28:2506–2512.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupiter SD, Cohen PJ, Weeks R, Tawake A, Govan H. 2014. Locally‐managed marine areas: multiple objectives and diverse strategies. Pacific Conservation Biology 20:165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kealiikanakaoleohaililani K, Giardina CP. 2016. Embracing the sacred: an indigenous framework for tomorrow's sustainability science. Sustainability Science 11:57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation and University of Victoria . 2018. Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine governance and management: a synthesis of Kitasoo/Xai'xais marine resources harvesting, territorial, and procedural protocols. Kitasoo/Xai'xais Integrated Resource Authority, Klemtu, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation . 2011. Kitasoo/Xai'xais integrated marine use plan. Kitasoo/Xai'xais Integrated Resource Authority, Klemtu, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation . 2019. Kitasoo/Xai'xais management plan for Pacific Herring. Klemtu, British Columbia, Canada. Kitasoo/Xai'xais Integrated Resource Authority, Klemtu, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Leopold A. 1933. The conservation ethic. Journal of Forestry 31:634–643. [Google Scholar]

- Lepofsky D, Caldwell M. 2013. Indigenous marine resource management on the Northwest Coast of North America. Ecological Processes 2:12. [Google Scholar]

- Lunstrum E, Ybarra M. 2018. Deploying difference security threat narratives and state displacement from protected areas. Conservation and Society 16:114‐124. [Google Scholar]

- Ommer RE. 2007. Coasts under stress: restructuring and social‐ecological health. McGill‐Queen's Press‐MQUP, Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Redford KH, Hulvey KB, Williamson MA, Schwartz MW. 2018. Assessment of the conservation measures partnership's effort to improve conservation outcomes through adaptive management. Conservation Biology 32:926–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salafsky N, et al. 2008. A standard lexicon for biodiversity conservation: unified classifications of threats and actions. Conservation Biology 22:897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Deiner K, Forrester T, Grof‐Tisza P, Muir MJ, Santos MJ, Souza LE, Wilkerson ML, Zylberberg M. 2012. Perspectives on the open standards for the practice of conservation. Biological Conservation 155:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson LB. 2017. As we have always done: indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Trosper RL. 2009. Resilience, reciprocity and ecological economics: northwest Coast sustainability. Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission . 2015. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly . 2007. United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. UN, New York. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Details of Kitasoo/Xai'xais historical and contemporary conservation strategies as categorized into the CMP Conservation Actions (Appendix S1) are available online. The authors are solely responsible for the content and functionality of these materials. Queries (other than absence of the material) should be directed to the corresponding author.