Abstract

Background:

Men who have sex with men (MSM) with bacterial STDs are at elevated risk for HIV. We evaluated the integration of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) referrals into STD partner services (PS) for MSM.

Setting:

King County, Washington

Methods:

Disease Intervention Specialists (DIS) in King County attempt to provide PS to all MSM with early syphilis and, as resources allow, MSM with gonorrhea or chlamydia. Our health department defines MSM with any of the following as at high HIV risk: early syphilis, rectal gonorrhea, methamphetamine/poppers use, sex work, or an HIV-unsuppressed partner. DIS offer high-risk MSM referral to our STD Clinic for PrEP and other MSM referral to community providers. In 2017, we interviewed a random sample of MSM offered referrals in 2016 to assess PrEP initiation following PS.

Results:

From 8/2014-8/2017, 7546 cases of bacterial STDs were reported among HIV-negative MSM. DIS provided PS to 3739 MSM, of whom 2055 (55%) were at high risk. DIS assessed PrEP use in 1840 (90%) of these men, 895 (49%) of whom reported already using PrEP. DIS offered referrals to 693 (73%) of 945 MSM not on PrEP; 372 (54%) accepted. Among 132 interviewed for the random sample, men who accepted referrals at initial interview were more likely to report using PrEP at follow-up (32/68=47%) than those who did not (12/64=19%) [p=0.0006]. 10.4% of all interviewed MSM initiated PrEP following PS-based referral.

Conclusions:

Integrating PrEP referrals into STD PS is an effective population-based strategy to link MSM at high HIV risk to PrEP.

Keywords: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, men who have sex with men, sexually transmitted diseases, partner services, surveillance

INTRODUCTION

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis is effective at preventing new HIV infections among men who have sex with men (MSM)1–3, and clinical and public health guidelines recommend PrEP for populations at substantial risk for HIV infection4–7. Since its introduction in 2012, PrEP use has increased rapidly among MSM in the U.S., but many MSM with indications for PrEP have not been reached and uptake has varied widely by region, age, and race/ethnicity8–10. Identifying acceptable, effective, and equitable approaches for promoting PrEP use among MSM is critical to the successful implementation of this effective intervention.

Diagnosis with bacterial sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) has long been associated with risk for HIV diagnosis and acquisition11–13, and recent studies have identified early syphilis and rectal infections, in particular, as associated with future HIV acquisition among MSM14–19. These infections are legally reportable to health departments throughout the U.S., nearly all health departments routinely provide partner services (PS) to people diagnosed with early syphilis, and some selectively provide these services to people with gonorrhea or chlamydia20. As a result, public health STD PS may represent a population-based opportunity to link people at high risk of acquiring HIV to PrEP and, insofar as black and Latino MSM have higher rates of STD diagnosis than other MSM19,21–23, to reduce racial/ethnic inequities in PrEP use.

As part of a broader effort to leverage STD PS for HIV prevention in Washington State, Public Health–Seattle & King County (PHSKC) began routinely asking about current PrEP use and offering referrals to PrEP care for HIV-negative MSM not currently on PrEP as part of PS interviews in October 2014. Here, we describe an evaluation of the uptake and effectiveness of PS-based PrEP referrals and the use of PS data to monitor PrEP use among MSM with STDs.

METHODS

STD case reporting

Medical providers in Washington State are legally required to complete a case report for each person they diagnose with syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia. This form includes gender of sex partners and anatomical site of gonococcal and chlamydial infection, allowing health departments to identify MSM. Laboratories are also required to report these infections, and public health staff follow-up on laboratory-reported cases to ensure case reports are complete.

Partner services intervention

In October 2014, PHSKC began offering PrEP at its STD Clinic. In preparation, disease intervention specialists (DIS) began assessing PrEP use among and offering referrals for PrEP to select clients in August 2014. (DIS are public health staff who conduct outreach investigations, including PS.) We initially limited assessment and referrals to MSM with early syphilis, the population with the highest prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection at the time of STD diagnosis24. Informed by analyses examining correlates of HIV incidence among local MSM16,25, we expanded PrEP assessment to include all MSM receiving PS and referrals to include MSM diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea in May 2015. Then, following the introduction of statewide PrEP implementation guidelines6, we expanded referrals to all MSM receiving PS in January 2016.

PHSKC uses the Washington State PrEP Implementation Guidelines to define priority populations for PrEP referral. The guidelines define two categories of HIV risk, a high risk group for whom providers should initiate PrEP and an intermediate risk group with whom providers should discuss PrEP initiation. MSM are considered at high risk if they meet any of the following criteria: diagnosis of early syphilis or rectal gonorrhea; methamphetamine or poppers use or sex work in the prior year; or an ongoing sexual partnership with an HIV-positive person whose viral load is not suppressed or who is not taking or recently started antiretroviral therapy6,16. MSM are considered at intermediate risk if they meet any of the following criteria: condomless anal sex outside of a long-term mutually monogamous relationship an HIV-negative partner; diagnosis of chlamydial infection or urethral or pharyngeal gonorrhea; an ongoing sexual partnership with an HIV-positive partner who is on antiretroviral therapy and is virologically suppressed; injection drug use; seeking a prescription for PrEP; or completing a course of post-exposure prophylaxis. DIS assess risk status based on STD diagnosis from the case report and the case’s self-reported behaviors. DIS offer referrals to the PHSKC STD Clinic to high risk MSM and to community PrEP providers to high risk MSM who refuse STD clinic referrals and intermediate risk MSM.

Population and data

HIV-negative MSM reported to PHSKC with early syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia from August 2014-August 2017 were included in this analysis. We defined men as MSM if they reported sex with men in the prior year during PS interviews, their provider indicated male sex partners on the case report, or they were diagnosed with rectal gonorrhea or rectal chlamydia. The Washington State Department of Health routinely matches local STD reporting data with the state’s Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS)24. We excluded men diagnosed with HIV prior to or at the time of STD diagnosis based on eHARS HIV diagnosis dates or self-report during PS interview.

Initiation of PrEP care and PrEP utilization

We conducted two assessments of PrEP care initiation and use following referrals. First, for the entire evaluation period, we linked records from people accepting PrEP referrals to the STD clinic PrEP program database to determine which high risk men attended at least 1 PrEP-related clinic visit after their PS interview. If MSM accepted multiple referrals to the STD clinic before attending a clinic visit, only the referral immediately prior to the clinic visit was considered to have resulted in a PrEP visit.

Second, we conducted an analysis of MSM PS recipients in 2016, the first year during which we offered all HIV-negative MSM referrals to PrEP, to estimate the proportion of MSM who initiated PrEP following PS. We conducted follow-up interviews with a random sample of 50% of MSM who were offered PrEP referrals during their PS interviews in 2016. To create the sample, we stratified these cases into four groups by whether they accepted a PrEP referral and risk category (high vs. intermediate). We used the latest interview in 2016 if an individual was interviewed more than once. The sample included 189 cases distributed equally across the four strata. A single DIS attempted to re-interview sampled cases from April-September 2017 and asked respondents whether they had used PrEP at any time following initial PS interview. Among respondents not currently using PrEP, the DIS assessed respondents’ HIV risk, offered additional PrEP referrals, and asked about barriers to PrEP initiation.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportions of cases receiving PS who were asked about PrEP, already taking PrEP, offered PrEP referrals by DIS, accepted referrals, and (among those accepting referrals to the STD clinic) attended at least 1 visit for PrEP care. We compared outcomes across strata using chi-square tests. We assessed correlates of PrEP use (among those whose PrEP use was assessed) and acceptance of a PrEP referral (among those offered referrals) at initial interview using chi-square tests for bivariable analyses and Poisson regression with robust variance for multivariable analyses. We used STD cases as the unit of analysis because our intervention was delivered at the case level.

We examined temporal trends in PrEP use overall and by HIV risk using the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for trend. Because PrEP users test frequently for STDs, leading to increased ascertainment of asymptomatic infections, we also evaluated trends among MSM with symptomatic infections (defined as urethral gonorrhea and primary/secondary syphilis) as a measure less likely to be affected by ascertainment bias. To address the potential for MSM receiving PS more than once per year to bias estimates of PrEP use, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using only one case per year for each unique person. In this analysis, MSM who had PrEP use assessed during more than one PS interview in a given year had a single interview randomly selected for inclusion; however, MSM could contribute data in multiple years.

Among men interviewed for the random sample, we assessed correlates of completing a follow-up interview and compared the proportion reporting current PrEP use among those who accepted vs. declined referrals overall and within risk strata using chi-square tests. We calculated the number needed to interview (NNTI) for one client to initiate PrEP in two ways: (1) assuming that all PrEP initiations following acceptance of a PS-based referral could be attributed to the referral and (2) assuming the rate of PrEP initiation observed in men who refused referrals represented a background rate that would have occurred without our intervention. (For details and full equations, see Supplemental Digital Content 1). Finally, we described progress towards PrEP initiation and barriers to PrEP experienced by people who did not initiate PrEP following a referral as well as acceptance of new referrals at follow-up.

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institutes, Cary, NC) and Stata version 15 (College Station, TX). These activities were conducted as part of public health program evaluation and therefore not considered human subjects research.

RESULTS

Population

From August 1, 2014, through August 30, 2017, 7546 cases of early syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia were reported among 5036 unique HIV-negative MSM in King County, Washington, of whom 3739 (50%) cases were interviewed for PS, including 71% of MSM with early syphilis or rectal gonorrhea and 41% of MSM with other reportable STDs (Table 1). Cases who were under age 35, Hispanic/Latino, and diagnosed with gonorrhea or early syphilis were more likely to receive PS (p<0.01 for all).

Table 1.

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use and uptake among HIV-negative MSM with bacterial STDs receiving partner services (PS) in King County, WA, from August 2014-August 2017

| Total | Early syphilis or rectal GC | CT (any site) or urethral or pharyngeal GCa | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (of total) | 7546 | 2145 (28%) | 5401 (72%) | ||

| Received PS (of cases) | 3739 (50%) | 1517 (71%) | 2222 (41%) | <0.0001 | |

| High HIV risk (of PS recipients) | 2055 (55%) | 1517 (100%) | 538 (24%) | <0.0001 | |

| High Risk PS recipients (N = 538) | Intermediate Risk PS recipients (N = 1684) | ||||

| PrEP use assessed (of PS recipients) | 3238 (87%) | 1374 (91%) | 466 (87%) | 1398 (83%) | <0.0001 |

| Currently using PrEP (of assessed) | 1330 (41%) | 655 (48%) | 240 (52%) | 435 (31%) | <0.0001 |

| Not currently using PrEP (of assessed) | 1908 (59%) | 719 (52%) | 226 (48%) | 963 (69%) | <0.0001 |

| Offered PrEP referral (of non-users) | 949 (50%) | 602 (84%) | 91 (40%) | 256 (27%) | <0.0001 |

| Accepted PrEP referral (of offered PrEP) | 501 (53%) | 312 (52%) | 60 (66%) | 129 (50%) | 0.0284 |

| Accepted STD clinic referral (of accepted) | 289 (58%) | 221 (29%) | 32 (53%) | 36 (28%) | <0.0001 |

| Attended PrEP assessment visitb (of clinic referral) | 155 (54%) | 129 (58%) | 16 (50%) | 10 (28%) | 0.0027 |

| Attended PrEP assessment visit within 3 month^ (of clinic referral) | 132 (46%) | 110 (50%) | 15 (47%) | 7 (19%) | 0.0032 |

Excludes co-infections with early syphilis or rectal gonorrhea.

As of November 9, 2017.

Of the 3739 PS recipients, most were non-Latino White (61%) or Latino (19%). The median age was 30 [interquartile range (IQR)=25-38], and 23% reported poppers use, 4% methamphetamine use, and 38% ≥10 male sex partners in the prior year. Overall, 2055 (55%) were at high HIV risk and eligible to receive PrEP at the STD clinic, 1374 (67%) of whom were diagnosed with early syphilis or rectal gonorrhea and 538 (33%) had other infections and at least one behavior defining them as at high risk per local guidelines (Table 1). Twenty-four percent of cases diagnosed with chlamydia or urethral or pharyngeal gonorrhea were considered high risk.

PrEP use prior to STD PS

Of the 3238 PS recipients who were asked about current PrEP use (87% of total recipients), 1330 (41%) reported being on PrEP. MSM at high risk were more likely to report being on PrEP than men at intermediate risk (49% vs. 31%, p<0.0001). In multivariable analyses, being on PrEP was associated with being non-Latino white, age 30-44, using poppers, having ≥10 or an unknown number of male sex partners in the prior year, more recent year of diagnosis, and diagnosis with early syphilis, rectal infections, or pharyngeal chlamydia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with reporting current PrEP use and accepting referrals to PrEP services at initial STD PS interview

| Characteristic | Total PrEP use assessed | On PrEP prior to PS interview | Association with Current PrEP Usea | Offered PrEP referral | Accept PrEP referral | Association with Accepting Referrala | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % of total | N | % | IRR (95%CI) | N | N | % | IRR (95%CI) | |

| Total | 3238 | 1330 | 41% | 949 | 501 | 53% | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Asian | 253 | 89% | 75 | 30% | 0.84 (0.68-1.04) | 81 | 52 | 64% | 1.26 (1.05-1.51) c |

| Black | 175 | 5% | 55 | 31% | 0.74 (0.62-0.89) d | 65 | 38 | 58% | 1.19 (0.96-1.49) |

| Latino | 626 | 19% | 250 | 40% | 0.91 (0.82-1.01) | 207 | 116 | 56% | 1.07 (0.93-1.24) |

| White | 1973 | 61% | 879 | 45% | Reference | 528 | 262 | 50% | Reference |

| Other | 211 | 7% | 71 | 34% | 0.86 (0.72-1.04) | 68 | 33 | 49% | 0.93 (0.72-1.19) |

| Age (in years) | |||||||||

| 17-24 | 720 | 22% | 174 | 24% | 0.63 (0.53-0.74)e | 278 | 157 | 56% | 1.63 (1.25-2.11) e |

| 25-29 | 865 | 27% | 349 | 40% | 0.98 (0.87-1.11) | 283 | 165 | 58% | 1.71 (1.32-2.22) e |

| 30-34 | 623 | 19% | 303 | 49% | 1.18 (1.04-1.33) c | 147 | 73 | 50% | 1.46 (1.10-1.94) d |

| 35-44 | 556 | 17% | 302 | 54% | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) e | 108 | 62 | 57% | 1.64 (1.23-2.18) e |

| 45+ | 471 | 15% | 201 | 43% | Reference | 132 | 43 | 33% | Reference |

| STD (ordered by HIV incidence following infection) | |||||||||

| Rectal GC | 866 | 27% | 431 | 50% | 1.38 (1.22-1.57) e | 343 | 189 | 55% | 0.96 (0.81-1.13) |

| Early syphilis | 508 | 16% | 224 | 44% | 1.23 (1.07-1.41) d | 259 | 123 | 47% | 0.88 (0.73-1.07) |

| Urethral GC | 580 | 18% | 193 | 33% | Reference | 141 | 80 | 57% | Reference |

| Rectal CT | 568 | 18% | 230 | 40% | 1.31 (1.13-1.52)e | 80 | 43 | 54% | 1.08 (0.84-1.38) |

| Pharyngeal GC | 432 | 13% | 166 | 38% | 1.12 (0.96-1.30) | 94 | 42 | 45% | 0.80 (0.61-1.03) |

| Urethral CT | 218 | 7% | 65 | 30% | 1.01 (0.81-1.26) | 22 | 17 | 77% | 1.29 (0.98-1.70) |

| Pharyngeal CT | 48 | 1% | 19 | 40% | 1.44 (1.02-2.03) c | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1.56 (1.23-1.98) e |

| GC/CT, site unknown | 18 | 1% | 2 | 11% | 0.32 (0.09-1.15) | 9 | 6 | 67% | 1.45 (0.95-2.21) |

| Methampetamine use | |||||||||

| Yes | 141 | 4% | 74 | 52% | 0.91 (0.79-1.07) | 46 | 31 | 67% | 1.14 (0.92-1.42) |

| No/Unknown | 3097 | 96% | 1256 | 41% | Reference | 903 | 470 | 52% | Reference |

| Poppers use | |||||||||

| Yes | 776 | 24% | 423 | 55% | 1.24 (1.15-1.35) e | 208 | 141 | 68% | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) e |

| No/Unknown | 2462 | 76% | 907 | 37% | Reference | 741 | 360 | 49% | Reference |

| Number of male sex partners | |||||||||

| 10+ | 1256 | 39% | 446 | 36% | 1.64 (1.49-1.80) e | 309 | 196 | 63% | 1.26 (1.11-1.42) e |

| 0-9 | 1541 | 48% | 446 | 29% | Reference | 534 | 261 | 49% | Reference |

| Unknown | 441 | 14% | 197 | 45% | 1.50 (1.32-1.71) e | 106 | 44 | 42% | 0.82 (0.64-1.06) |

| Year of diagnosisb | 1.25 (1.20-1.31) e | 1.04 (0.97-1.11) | |||||||

| 2014 | 294 | 9% | 56 | 19% | 54 | 26 | 48% | ||

| 2015 | 1048 | 32% | 356 | 34% | 201 | 95 | 47% | ||

| 2016 | 1069 | 33% | 495 | 46% | 377 | 208 | 55% | ||

| 2017 | 827 | 26% | 423 | 51% | 317 | 172 | 54% | ||

| HIV risk status | |||||||||

| Early syphilis or rectal GC | 1374 | 42% | 655 | 48% | 602 | 312 | 52% | ||

| Other high risk | 466 | 14% | 240 | 52% | 91 | 60 | 66% | ||

| Intermediate risk | 1398 | 43% | 435 | 31% | 256 | 129 | 50% | ||

IRR = incidence rate ratio.

Multivariable Poisson regression including all characteristics except HIV risk strata, which is a composite of STD, substance use, and other characteristics; p-values are from Wald tests.

2014 includes cases diagnosed from August-December only and 2017 from January-August only.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001.

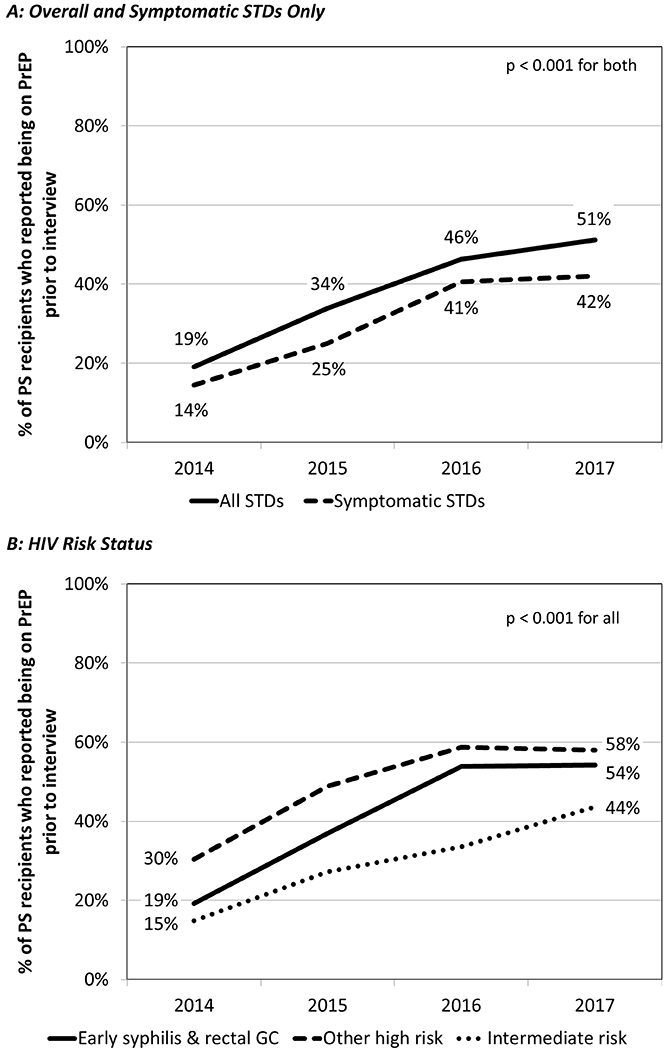

Trends in PrEP use

The proportion of HIV-negative MSM who were on PrEP at the time of PS interview increased from 19% in 2014 to 51% in 2017 among MSM with all STDs and from 14% to 42% among those with symptomatic STDs (p<0.001 for both; Fig. 1A). Similar trends were observed when stratifying by HIV risk (Fig. 1B) and by age and race/ethnicity (data not shown) with men at high risk, ages 35-44, and non-Latino white consistently reporting the highest use. In a sensitivity analysis accounting for men receiving PS more than once in a year, we found nearly identical estimates of overall PrEP use over time, increasing from 19% in 2014 to 50% in 2017 (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Temporal trends in reported PrEP use among HIV-negative MSM receiving STD partner services, August 2014-August 2017.

Presented overall and among symptomatic STDs only (Panel A) and by HIV risk strata (Panel B). Limited to men whose PrEP use was assessed as part of the partner services interview. Symptomatic STDs were defined as urethral gonorrhea and primary or secondary syphilis. GC = gonorrhea.

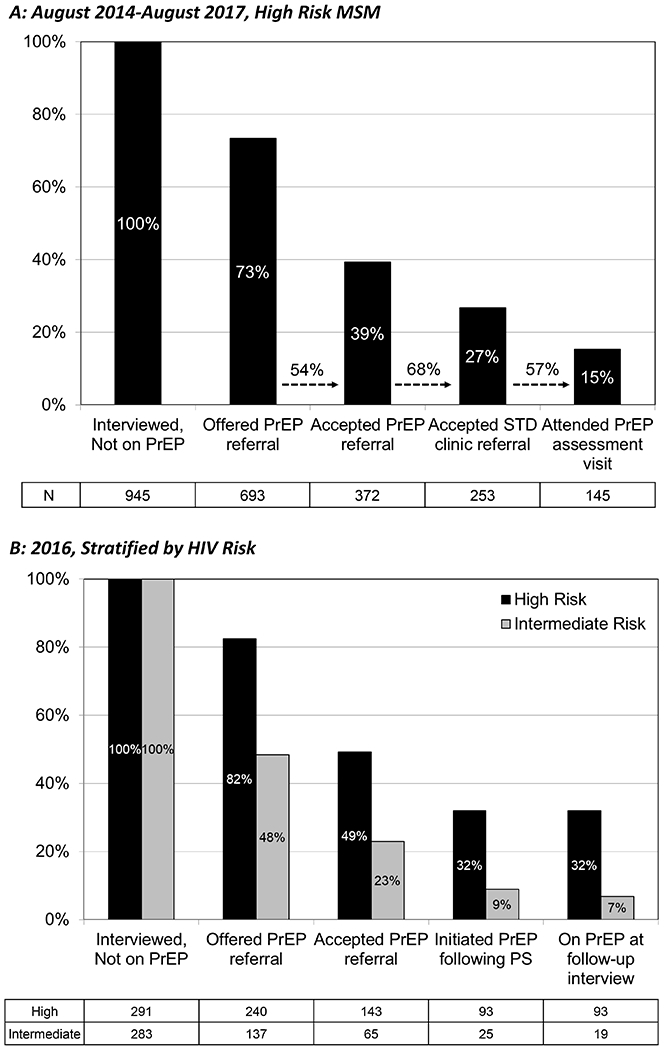

PrEP referral through STD PS

During the evaluation period, DIS offered PrEP referral to 693 (71%) of the 945 high risk MSM PS recipients who were not already on PrEP (Table 1). Of those offered, 372 (54%) accepted a referral, 253 (68%) to the STD clinic and 119 (32%) to community providers. Of those referred to the STD clinic, 145 (57%) had attended an initial PrEP evaluation appointment at the clinic as of November 9, 2017, 125 (49%) within 3 months of PS interview. Overall, 7% of HIV-negative MSM receiving PS and 21% of those offered a referral to the STD clinic for PrEP attended an evaluation appointment at the STD clinic (Fig. 2A). Referral outcomes for intermediate risk MSM and stratified by HIV risk criteria are presented in Table 1.

Figure 2. STD partner services (PS) provision, PrEP use, and acceptance of PrEP referrals among HIV-negative MSM diagnosed with bacterial STDs in King County, Washington.

Presented among MSM at the highest risk for HIV acquisition, August 2014-August 2017 (Panel A) and among all MSM diagnosed in 2016 (Panel B). For August 2014-August 2017 (A), assessment of PrEP uptake was limited to attendance at a PrEP evaluation visit at the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD Clinic. For 2016 (B), PrEP initiation and current use was assessed during follow-up interviews of a random sample of who were offered PrEP referrals during their PS interview in 2016 (includes PrEP initiation and use within and outside the STD Clinic).

Random sample: PrEP uptake

In 2016, 377 HIV-negative/unknown MSM received STD PS, reported not being on PrEP at the time of the interview, and were offered a referral for PrEP (Table 3). Of these, 189 (50%) were randomly sampled for follow-up interviews conducted April-September 2017, of whom 132 (70%) were interviewed a median of 315.5 days (IQR=254-393) following their initial PS interview, 56 (29%) could not be contacted, and 1 (1%) refused to be interviewed. Response rates did not differ significantly by age, race/ethnicity, or strata defined by referral acceptance and risk status (p>0.2 for all).

Table 3.

PrEP outcomes in a random sample of HIV-negative MSM receiving STD partner services (PS), stratified by HIV risk and PrEP referral acceptance at initial PS interview

| Outcomes | MSM at high risk | MSM at intermediate risk | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accepted | Did not accept | Accepted | Did not accept | ||

| Initial PS interviews (% of total) | 143 (38%) | 97 (26%) | 65 (17%) | 72 (19%) | |

| Assigned to random sample (% of total) | 50 (35%) | 48 (49%) | 46 (71%) | 45 (63%) | <0.0001 |

| Interviewed (% of assigned) | 34 (68%) | 31 (65%) | 34 (74%) | 33 (73%) | 0.72 |

| PrEP use following initial interview | |||||

| Ever on PrEP following initial PS (% of interviewed) | 22 (65%) | 7 (23%) | 13 (38%) | 6 (18%) | 0.0003 |

| Currently on PrEP (% of interviewed) | 22 (65%) | 6 (19%) | 10 (29%) | 6 (18%) | <0.0001 |

| Receiving PrEP from STD clinic (% of current users) | 11 (50%) | 1 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) | 0.02 |

| Acceptance of new PrEP referrals | |||||

| Not currently on PrEP (% of interviewed) | 12 (35%) | 25 (81%) | 24 (71%) | 27 (82%) | <0.0001 |

| Interested in PrEP at follow-up (% of non-users) | 6 (50%) | 9 (36%) | 11 (46%) | 13 (48%) | 0.79 |

| Identified as at high HIV risk at follow-up (% of interested) | 6 (100%) | 8 (89%) | 7 (64%) | 6 (46%) | 0.06 |

| Accepted referral or will go to own provider (% of interested) | 5 (83%) | 5 (56%) | 10 (91%) | 10 (77%) | 0.37 |

PrEP uptake following initial PS interview and acceptance of new referrals among those who reported not being on PrEP are described in Table 3. Overall, 44 (33%) of the 132 with a follow-up interview reported being on PrEP at follow-up and 4 (2%) had initiated PrEP but discontinued it. Of current PrEP users, 70% were prescribed PrEP by community providers, and 98% reported taking >4 doses in the prior 7 days. Men who accepted referrals at initial interview were significantly more likely to be using PrEP at follow-up (32/68=47%) than those who did not (12/64=19%) [relative risk (RR) = 2.51, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.42-4.43; p=0.0006]. This effect was greater among high risk men (3.34, 1.56-7.15; p=0.0002) than intermediate risk men (1.62, 0.66-3.95; p=0.28).

Reweighting responses by the proportion of PS recipients in each strata of the random sample, 40% of all men offered referrals and 56% of those who accepted referrals reported having initiated PrEP following PS. Applying estimates from the random sample to overall PS and PrEP referral outcomes from 2016 suggests that 32% of high risk and 9% of intermediate risk MSM who received PS and were not already using PrEP initiated PrEP following their interview (Fig. 2B) and that 10.4% of all interviewed HIV-negative MSM (including those previously on PrEP) initiated PrEP following a referral provided via PS. This corresponds to a NNTI for one client to initiate PrEP following PS referral of 9.6. Assuming the rate of PrEP initiation observed in men who refused referrals represents a background rate that would have occurred in the absence of our intervention, 6.5% of interviewed MSM initiated PrEP as a consequence of PS-based referral, and the NNTI was 15.

Random sample: Barriers to PrEP use and acceptance of new referrals

Of the 33 randomly sampled men who accepted a referral at the initial interview but did not initiate PrEP, 27 remembered receiving a referral, of whom 8 (30%) decided they were not interested in PrEP, 15 (56%) were interested but did not contact a provider, 2 (7%) scheduled an appointment with a provider but did not attend, 1 (4%) reported having an upcoming appointment, and 1 (4%) had an appointment but decided against initiating PrEP. Among the 33 referred, the most commonly reported barriers to PrEP were not thinking they were at risk (45%) and the frequency of provider visits for follow-up (42%) [complete table of barriers available as Supplementary Digital Content 2].

Of the 88 men who reported not being on PrEP at follow-up, 39 (44%) were interested in starting PrEP, 30 (77%) of whom accepted a referral to a PrEP provider or indicated they would seek PrEP from their own medical provider (Table 3). Of men interested in starting PrEP, 27 (69%) were identified as being at high risk based on their follow-up interview, including 13 of 24 who had been classified as intermediate risk at initial interview.

DISCUSSION

We found that routinely offering referrals to PrEP providers as part of STD PS for MSM was both feasible and effective at increasing PrEP uptake, particularly among men at highest risk for HIV. Approximately half of MSM PS recipients accepted referrals when offered, accepting a referral was associated with a 2.5-fold increase in PrEP use following PS, and in our experience, approximately 1 in 3 MSM who accepted referrals through PS initiated PrEP. While we regard this level of uptake as a success, we observed significant attrition along the continuum from offering referrals to PrEP initiation, highlighting the need to improve intervention delivery throughout the process. Additionally, we found that following up with men after their initial PS interview provided an opportunity to address barriers to PrEP use and offer additional referrals.

Our results highlight how PrEP promotion can be successfully integrated into STD PS, one of several opportunities to broaden the focus of PS to address related public health objectives26. We previously reported that STD PS can be used to increase HIV testing among MSM24 and identify people with HIV who are inadequately engaged in care27. Here, we found that approximately one of every 10 MSM receiving STD PS can be successfully referred to initiate PrEP. These findings should prompt health departments to expand the objectives of STD PS and consider using HIV-specific resources to fund these more broadly conceived programs.

Our ability to successfully integrate PrEP referrals into PS was facilitated by several factors: the large number of PrEP providers in our area, our ability to identify MSM before initiating PS using case report data, DIS coordination of our public health PrEP program, and the relative paucity of financial barriers to PrEP resulting from Washington State’s expansion of Medicaid and statewide PrEP drug assistance program28. These factors likely increased the effectiveness of PrEP referrals in our setting and may impact other jurisdictions’ ability to reproduce our program. However, the high underlying rate of PrEP use among MSM limited the number of men eligible for referral. Integrating PrEP promotion into STD PS may have even more potential for benefit in settings with less PrEP use, particularly if paired with PrEP clinical care or navigation services.

Our findings also demonstrate how assessing PrEP use during PS interviews can help health departments monitor PrEP use in a population of MSM at high risk for HIV. Consistent with other local analyses29,30, we found that PrEP use has dramatically increased among MSM in King County since 2014. In 2017, just over half of PS recipients were on PrEP. Of note, 42% of MSM with symptomatic STDs–infections unlikely to have been detected as a result of PrEP-related screening–were on PrEP, indicating that the high level of PrEP use we observed was not simply a consequence of PrEP-related STD testing. This final estimate is only slightly higher than other recent local estimates from behavioral and sentinel surveillance of PrEP use among MSM at high and intermediate risk, which range from 35–39%30. Despite this success, we identified significant and sustained racial/ethnic inequities in PrEP use. Of particular importance, as in many other settings8–10,31–33, black and Latino MSM, populations that experience higher HIV incidence than white MSM in the U.S.34 and locally30, were less likely to be using PrEP. This uneven uptake of PrEP has the potential to further increase inequities in HIV incidence. Integrating PrEP promotion into STD PS has particular potential to help address these inequities because it is population-based and because black and Latino MSM are also disproportionately affected by STDs19,21–23.

This program evaluation has some limitations. First, we relied on self-report when assessing PrEP use. Second, we were unable to assess the success of referrals for all MSM receiving PS and relied on conducting interviews with a random sample of 2016 cases to assess uptake and effectiveness of referrals. Third, although we found a strong association between referrals and PrEP initiation, this was an observational study, and we cannot directly attribute PrEP initiation to our intervention. Finally, not all MSM diagnosed with STDs may have been identified as MSM and prioritized for PS, PS recipients differed from men who refuse PS or could not be located, assessment of PrEP use improved over time (data not shown) and differed by risk criteria, and some men were diagnosed with multiple STIs and received PS more than once over the evaluation period, potentially biasing our estimates of PrEP use.

In conclusion, STD PS represent an opportunity to promote PrEP to a large and diverse population of MSM at high risk for HIV and provide a population-based estimate of PrEP use in this population. PrEP promotion should be considered as an outcome of syphilis PS, and health departments should consider expanding PS programs to MSM with STDs other than syphilis with HIV prevention as an explicit goal.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Public Health – Seattle & King County (PHSKC) disease intervention specialists for their work conducting partner services and promoting PrEP in persons with STDs as well as PHSKC epidemiology and data management staff for their work on the supplemental database.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: MRG has received research support from Cempra Pharmaceuticals and Melinta Therapeutics. JCD has conducted research supported by grants to the University of Washington from Hologic, Quidel, and ELITech and received travel support to a conference supported by Gilead. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

This program and its evaluation were supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [H25 PS004364]; the Washington State Department of Health; and Public Health – Seattle & King County. The evaluation was also supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [UL1 TR002319] and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health [P30 AI027757].

Footnotes

Note: This work was presented in part at the 2017 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Seattle, WA, and the 2018 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No New HIV Infections With Increasing Use of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Clinical Practice Setting. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;61(10):1601–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach - 2nd ed Geneva; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – 2017. update: A clinical practice guideline. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

- 6.Golden MR, Lindquist S, Dombrowski JC. Public Health-Seattle & King County and Washington State Department of Health Preexposure Prophylaxis Implementation Guidelines, 2015. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(4):264–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saag MS, Benson CA, Gandhi RT, et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2018 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. Jama. 2018;320(4):379–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchbinder SP, Liu AY. CROI 2018: HIV Epidemic Trends and Advances in Prevention. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2018;26(1):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu AY, Buchbinder SP. CROI 2017: HIV Epidemic Trends and Advances in Prevention. Topics in antiviral medicine. 2017;25(2):35–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AIDSVu. Mapping PrEP: First Ever Data on PrEP Users Across the U.S. Available at: https://aidsvu.org/prep/ Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

- 11.Piot P, Laga M. Genital ulcers, other sexually transmitted diseases, and the sexual transmission of HIV. Bmj. 1989;298(6674):623–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sexually transmitted infections. 1999;75(1):3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward H, Ronn M. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2010;5(4):305–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Shepard C, Schillinger JA. The high risk of an HIV diagnosis following a diagnosis of syphilis: a population-level analysis of New York City men. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;61(2):281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Schillinger JA. HIV incidence among men with and those without sexually transmitted rectal infections: estimates from matching against an HIV case registry. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;57(8):1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Bell TR, Kerani RP, Golden MR. HIV Incidence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men After Diagnosis With Sexually Transmitted Infections. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(4):249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2010;53(4):537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solomon MM, Mayer KH, Glidden DV, et al. Syphilis predicts HIV incidence among men and transgender women who have sex with men in a pre-exposure prophylaxis trial. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley CF, Vaughan AS, Luisi N, et al. The Effect of High Rates of Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections on HIV Incidence in a Cohort of Black and White Men Who Have Sex with Men in Atlanta, Georgia. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2015;31(6):587–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, St Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2003;30(6):490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su JR, Beltrami JF, Zaidi AA, Weinstock HS. Primary and secondary syphilis among black and Hispanic men who have sex with men: case report data from 27 States. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grey JA, Bernstein KT, Sullivan PS, et al. Rates of Primary and Secondary Syphilis Among White and Black Non-Hispanic Men Who Have Sex With Men, United States, 2014. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2017;76(3):e65–e73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novak RM, Ghanem A, Hart R, et al. Risk factors and incidence of syphilis in HIV-infected persons, the HIV Outpatient Study, 1999–2015. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP, et al. Integrating HIV Testing as an Outcome of STD Partner Services for Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2016;30(5):208–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menza TW, Hughes JP, Celum CL, Golden MR. Prediction of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2009;36(9):547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golden MR, Katz DA, Dombrowski JC. Modernizing Field Services for Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Sexually Transmitted Infections in the United States. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017;44(10):599–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz DA, Golden MR, Bell TR, et al. Using Sexually Transmitted Disease Partner Services to Promote Engagement in HIV Care among Persons Living with HIV. Presented at: 2016 STD Prevention Conference; 2016; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washington State Department of Health. Pre-Exposure Drug Assistance Program (PrEP-DAP). Available at: https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/IllnessandDisease/HIVAIDS/HIVPrevention/PrEPDAP Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

- 29.Hood JE, Buskin SE, Dombrowski JC, et al. Dramatic increase in preexposure prophylaxis use among MSM in Washington state. Aids. 2016;30(3):515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Public Health – Seattle & King County HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Unit, Washington State Department of Health Infectious Disease Assessment Unit. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Report 2017. Vol. 86, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G, National HIVBSSG. Willingness to Take, Use of, and Indications for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men-20 US Cities, 2014. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016;63(5):672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snowden JM, Chen YH, McFarland W, Raymond HF. Prevalence and characteristics of users of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2014 in a cross-sectional survey: implications for disparities. Sexually transmitted infections. 2017;93(1):52–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare CB, Silverberg MJ, Volk JE. Disparities in Uptake of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis in a Large Integrated Health Care System. American journal of public health. 2016;106(10):e2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2016. Vol. 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.