Abstract

Background

Disc prolapse accounts for five percent of low‐back disorders but is one of the most common reasons for surgery.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to assess the effects of surgical interventions for the treatment of lumbar disc prolapse.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, PubMed, Spine and abstracts of the main spine society meetings within the last five years. We also checked the reference lists of each retrieved articles and corresponded with experts. All data found up to 1 January 2007 are included.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials (RCT) and quasi‐randomized trials (QRCT) of the surgical management of lumbar disc prolapse.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed trial quality and extracted data from published papers. Additional information was sought from the authors if necessary.

Main results

Forty RCTs and two QRCTs were identified, including 17 new trials since the first edition of this review in 1999. Many of the early trials were of some form of chemonucleolysis, whereas the majority of the later studies either compared different techniques of discectomy or the use of some form of membrane to reduce epidural scarring.

Despite the critical importance of knowing whether surgery is beneficial for disc prolapse, only four trials have directly compared discectomy with conservative management and these give suggestive rather than conclusive results. However, other trials show that discectomy produces better clinical outcomes than chemonucleolysis and that in turn is better than placebo. Microdiscectomy gives broadly comparable results to standard discectomy. Recent trials of an inter‐position gel covering the dura (five trials) and of fat (four trials) show that they can reduce scar formation, though there is limited evidence about the effect on clinical outcomes. There is insufficient evidence on other percutaneous discectomy techniques to draw firm conclusions. Three small RCTs of laser discectomy do not provide conclusive evidence on its efficacy, There are no published RCTs of coblation therapy or trans‐foraminal endoscopic discectomy.

Authors' conclusions

Surgical discectomy for carefully selected patients with sciatica due to lumbar disc prolapse provides faster relief from the acute attack than conservative management, although any positive or negative effects on the lifetime natural history of the underlying disc disease are still unclear. Microdiscectomy gives broadly comparable results to open discectomy. The evidence on other minimally invasive techniques remains unclear (with the exception of chemonucleolysis using chymopapain, which is no longer widely available).

Plain language summary

The effects of surgical treatments for individuals with 'slipped' lumbar discs

Prolapsed lumbar discs ('slipped disc', 'herniated disc') account for less than five percent of all low‐back problems, but are the most common cause of nerve root pain ('sciatica'). Ninety percent of acute attacks of sciatica settle with non‐surgical management. Surgical options are usually considered for more rapid relief in the minority of patients whose recovery is unacceptably slow.

This updated review considers the relative merits of different forms of surgical treatments by collating the evidence from 40 randomized trials and two quasi‐randomized controlled trials (5197 participants) on: (i) Discectomy ‐ surgical removal of part of the disc (ii) Microdiscectomy ‐ use of magnification to view the disc and nerves during surgery (iii) Chemonucleolysis ‐ injection of an enzyme into a bulging spinal disc in an effort to reduce the size of the disc

Despite the critical importance of knowing whether surgery is beneficial, only three trials directly compared discectomy with non‐surgical approaches. These provide suggestive rather than conclusive results. Overall, surgical discectomy for carefully selected patients with sciatica due to a prolapsed lumbar disc appears to provide faster relief from the acute attack than non‐surgical management. However, any positive or negative effects on the lifetime natural history of the underlying disc disease are unclear. Microdiscectomy gives broadly comparable results to standard discectomy. There is insufficient evidence on other surgical techniques to draw firm conclusions.

Trials showed that discectomy produced better outcomes than chemonucleolysis, which in turn was better than placebo. For various reasons including concerns about safety, chemonucleolysis is not commonly used today to treat prolapsed disc.

Many trials provided limited information on complications, but generally included recurrence of symptoms, need for additional surgery and allergic reactions (chemonucleolysis).

Many of the trials had major design weaknesses that introduced considerable potential for bias. Therefore, the conclusions of this review should be read with caution.

Future trials should be designed to reduce potential bias. Future research should explore the optimal timing of surgery, patient‐centred outcomes, costs and cost‐effectiveness of treatment options, and longer‐term results over a lifetime perspective.

Background

Lumbar disc prolapse ('slipped disc') accounts for less than five percent of all low‐back problems, but is the most common cause of nerve root pain ('sciatica'). Ninety percent of acute attacks of sciatica settle with conservative management. Absolute indications for surgery include altered bladder function and progressive muscle weakness, but these are rare. The usual indication for surgery is to provide more rapid relief of pain and disability in the minority of patients whose recovery is unacceptably slow.

The primary rationale of any form of surgery for disc prolapse is to relieve nerve root irritation or compression due to herniated disc material, but the results should be balanced against the likely natural history. Surgical planning should also take account of the anatomical characteristics of the spine and any prolapse (Carlisle 2005), the patient's constitutional make‐up and equipment availability. Of the techniques available, open discectomy, performed with (micro‐), or without the use of an operating microscope, is the most common, but there are now a number of other less invasive surgical techniques. Ideally, it would be important to define the optimal type of treatment for specific types of prolapse (Carragee 2003). For example, different surgical procedures may be appropriate if disc material is sequestrated rather than contained by the outer layers of the annulus fibrosus and the choice of treatment should reflect these.

Many of the early trials relate to the use of chemonucleolysis (dissolution of the nucleus by enzyme injection) using chymopapain. Chemonucleolysis became popular in the 1970s after its introduction as a therapy for a contained lumbar disc prolapse, i.e. without fragment sequestration into the spinal canal (Smith 1964). Concerns about its safety and controversy about its effectiveness led to it being withdrawn for a while by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, but it was re‐released in 1982. Its use is currently in decline, so this is an appropriate time to synthesise the evidence on its effectiveness.

There are several non‐systematic reviews that consider the relative merits of microdiscectomy, automated percutaneous discectomy and various types of arthroscopic microdiscectomy. In all these treatments, smaller wounds are said to promote faster patient recovery with earlier hospital discharge (Kahanovich 1995; Onik 1990; Kambin 2003) but the question remains whether that is actually associated with improved clinical outcomes. RCTs are required to provide Level 1 evidence of treatment efficacy. Moreover, treatment may prove to be of marginal benefit yet expensive and hence not cost effective. It is particularly important that the safety, efficacy and cost benefits of all new innovative procedures should be compared with currently accepted forms of treatment.

Objectives

We aimed to test the following null hypotheses. In the treatment of lumbar inter‐vertebral disc prolapse, there is no difference in effectiveness or incidence of adverse complications between: (i) any form of discectomy and conservative management (ii) microdiscectomy and open 'standard' discectomy (iii) forms of minimally invasive therapy including automated percutaneous discectomy, laser discectomy, percutaneous endoscopic discectomy, trans‐foraminal endoscopic discectomy and microdiscectomy (iv) chemonucleolysis and placebo injection (v) chemonucleolysis and discectomy (vi) discectomy with and without materials designed to prevent post‐operative scar formation

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized (RCT) or quasi‐randomized (QRCT ‐ methods of allocating participants to a treatment that are not strictly random e.g. by date of birth, hospital record number or alternation) controlled trials pertinent to the surgical management of lumbar disc prolapse.

Types of participants

Patients with lumbar disc prolapse who have indications for surgical intervention.

Where possible, an attempt was made to categorise patients according to their symptom duration (less than six weeks, six weeks to six months, more than six months) and by their response to previous conservative therapy. We included studies comparing methods of treatment of any type of lumbar disc prolapse and searched carefully for any data relating to specific types of prolapse (for example central, lateral, far‐out, sequestrated).

Types of interventions

Data were sought relating to the use of discectomy, micro‐discectomy, chemonucleolysis, automated percutaneous discectomy, nucleoplasty and laser discectomy. Any modifications to these interventional procedures were included, but alternative therapies such as nutritional or hormonal therapies were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were sought:

A) Patient centred outcomes:

(i) Proportion of patients who recovered according to self, a clinician's assessment or both (ii) Proportion of patients who had resolution or improvement in pain (iii) Proportion of patients who had an improvement in function measured on a disability or quality of life scale (iv) Return to work (v) Economic data as available (vi) Rate of subsequent back surgery

B) Measures of objective physical impairment:

Spinal flexion, improvement in straight leg raise, alteration in muscle power and change in neurological signs.

C) Adverse complications:

(i) Early: Damage to spinal cord, cauda equina, dural lining, a nerve root, or any combination; infection; vascular injury (including subarachnoid haemorrhage); allergic reaction to chymopapain; medical complications; death. (ii) Late: Chronic pain, altered spinal biomechanics, instability or both; adhesive arachnoiditis; nerve root dysfunction; myelocele; recurrent disc prolapse.

D) Cost data

Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant published data from randomized controlled trials in any language, up to 1 January 2007 were identified by the following search strategies:

(i) Computer aided searching of MEDLINE (Higgins 2005) with specific search terms (see Appendix 1) and PUBMED (www.ncbi.nlm.nih,.gov/). (ii) Personal bibliographies. (iii) Hand searching of Spine and meeting abstracts of most major spinal societies from 1985. (iv) Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. (v) Communication with members of the Cochrane Back Review Group and other international experts. (vi) Citation tracking from all papers identified by the above strategies.

The International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register and Clinical Trials Register were searched from their beginning to September 20, 2006 to identify ongoing studies (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/; clinicaltrials.gov).

Data collection and analysis

Eligible trials were entered into RevMan 4.2 and sorted on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For each included trial, assessment of methodological quality and data extraction were carried out as detailed below.

1. Two review authors (JNAG, GW) selected the trials to be included in the review. Disagreement was resolved by discussion, followed if necessary by further discussion with an independent colleague.

2. The methodological quality was assessed and internal validity scored by the review authors, assessing risk of pre‐allocation disclosure of assignment, intention‐to‐treat analysis, and blinding of outcome assessors (Schulz 1995). The quality of concealment allocation was rated in three grades: A: Clearly yes ‐ some form of centralized randomization scheme or assignment system; B: Unclear ‐ assignment envelopes, a "list" or "table", evidence of possible randomization failure such as markedly unequal control and trial groups, or trials stated to be random but with no description; C: Clearly no ‐ alternation, case numbers, dates of birth, or any other such approach, allocation procedures which were transparent before assignment. Withdrawal, blinding of patients and observers, and intention‐to‐treat analyses were assessed according to standard Cochrane methodology and tabulated in the results tables.

The nature, accuracy, precision, observer variation and timing of the outcome measures were tabulated. Initially any outcomes specified were noted. The data were then collated and the most frequently reported outcome measures (in five or more studies) used for meta‐analysis. In fact, only three outcomes were consistently reported: the patient's rating of success, a surgeon's rating of success and the need for a second procedure (treatment failure). To pool the results, ratings of excellent, good and fair were classified as 'success' and poor, unimproved and worse as 'failure'. The pooled data are given in the analysis table.

3. For each study, Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence limits (95% CI) were calculated. Results from clinically comparable trials were pooled using random effects models for dichotomous outcomes. It should be noted that in several instances the test for heterogeneity was significant, which casts doubt on the statistical validity of the pooling. Nevertheless, there is considerable clinical justification for pooling the trials in this way and in view of the clinical interest, these results are presented as the best available information at present, with the qualification that there may be statistical weaknesses to the results.

Results

Description of studies

Forty‐two studies have been included in this review as detailed below. Details of individual trials are presented in the Characteristics of Included Studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Many of the trials, particularly of surgery, had major design weaknesses. Some of the trials were of a very small number of patients. Methods and published details of randomization were often poor and there was lack of concealment of randomization. Because of the nature of surgical interventions, double blinding was not possible. Blinded assessment of outcome was generally feasible yet often not even attempted. There were few proper clinical outcomes (Deyo 1998), and the most common surgical outcomes were crude ratings by patients or surgeons. Some of the assessments were by the operating surgeon, or by a resident or fellow beholden to the primary investigator. Although 35 of the trials had follow‐up rates of at least 90%, there was often considerable early code break or crossover of patients which was not always properly allowed for in the analysis or presentation of results. Only ten of the 42 trials presented two‐year follow‐up results as recommended for surgical studies, although two of these trials also presented 10‐year results.

These defects of trial design introduced considerable potential for bias. Most of the conclusions of this review are based upon six to twelve‐month outcomes and there is a general lack of information on longer‐term outcomes.

Effects of interventions

Forty RCTs and two QRCTs are included in this updated review. This an increase of 15 reports over the first edition of the review (1998), but 17 new papers are actually included, as two were deleted from the original set (North 1995, Petrie 1996) due to a lack of publication of substantive results within a five‐year period. One additional new abstract was excluded for the same reason (Chung 1999). Sixteen of the original trials were found on MEDLINE, five by searching on‐line OVID and the final six by handsearching conference proceedings and personal bibliographies and correspondence with experts. The new trials were mainly collected by the authors from personal literature review or after notification by colleagues from the Cochrane Back Review Group. Nine additional trials are currently labelled 'ongoing' as insufficient data are available to allow critical analysis.

It was not possible to analyse patients according to duration of their symptoms, previous conservative treatment, type of disc prolapse, or indications for surgery, as few of the trials provided these data in usable form. Many trials provided limited information on selected complications, but these were not comparable between trials. Moreover, relatively small RCTs do not have sufficient statistical power to produce any meaningful conclusions about complications of low incidence. That requires a completely different kind of database, which is much larger and more representative of routine clinical practice (Hoffman 1993).

Five studies attempted to estimate costs (Lavignolle 1987; Muralikuttan 1992; Chatterjee 1995; Malter 1996; Geisler 1999) and three of these estimated cost‐effectiveness (Chatterjee 1995; Malter 1996; Geisler 1999), although their methodology has been criticised (Goosens 1998).

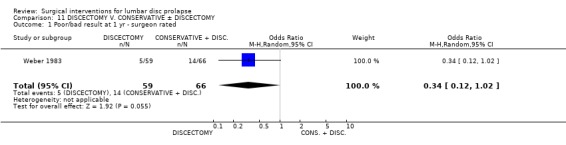

a) Discectomy

There are now four trials included in the review comparing surgical treatment of lumbar disc prolapse with some form of natural history, conservative treatment, or placebo but one of these is still only published as an abstract (Greenfield 2003). In the first trial, Weber (Weber 1983) compared long‐term outcomes of treatment by discectomy versus initial conservative management followed by surgery if conservative therapy failed. The trial was not blinded and 26% of the 'conservative' group actually came to surgery, i.e. crossed‐over, though there was an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Both patient and observer ratings showed that discectomy was significantly better than 'conservative therapy' at one year, but there were no significant differences in outcomes at four and ten years. Regardless of treatment, impaired motor function had a good prognosis, whereas sensory deficits remained in almost one‐half of the patients. Malter (Malter 1996) re‐analysed Weber's data and suggested that discectomy was highly cost‐effective, at approximately $29,000 per QALY gained.

In November 2006, the multi‐center US Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial was published (Weinstein 2006). This trial compared standard open discectomy with nonoperative treatment individualized to the patient. Primary outcomes were changes from baseline in the 36‐item Short‐Form bodily pain and physical function scales and modified Oswestry Disability Index. The major limitation of the trial was lack of adherence to assigned treatment and the amount of cross‐over: only 50% of patients assigned to surgery actually received surgery and 30% of those assigned to non‐operative treatment received surgery within three months of enrolment. Both surgically and conservatively treated groups improved substantially on all outcomes over two years follow‐up. Intention‐to‐treat analyses showed that the results tended to favour surgery, but the treatment effects on the primary outcomes were small and not statistically significant. In contrast, as‐treated analysis based on treatment received showed strong, statistically significant advantages for surgery on all outcomes at all follow‐up times. The amount of cross‐over makes it likely that the intention‐to‐treat analysis underestimates the true effect of surgery; but the resulting confounding also makes it impossible to draw any firm conclusions about the efficacy of surgery. Greenfield (Greenfield 2003) also compared microdiscectomy with a low‐tech physical therapy regime and educational approach . Although at twelve and eighteen months there were statistically significant differences in pain and disability favouring the surgical group, by 24 months this was no longer the case. It should be noted that the patients studied had all presented with low‐back pain and sciatica and were selected to include those with a small or moderate disc prolapse only.

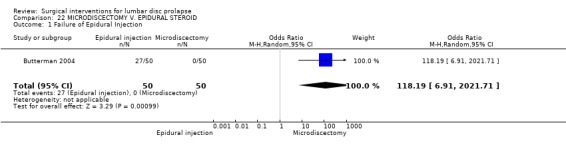

Butterman (Butterman 2004) compared results following microdiscectomy with those after an epidural steroid injection. Although the authors considered that the control arm was microdiscectomy it is probably more useful to consider this as the intervention. Patients undergoing discectomy had the most rapid decrease in their symptoms. Twenty‐seven of 50 patients receiving a steroid injection had a subsequent microdiscectomy. Outcomes in this cross‐over group did not appear to have been adversely affected by the delay in surgery. The patients who had a successful epidural steroid injection were twice as likely to have an extruded or sequestered disc as those in whom the injection failed. Very limited data are available from a trial comparing microdiscectomy plus isometric muscle training with plain muscle training (Osterman 2003) and this trial is labelled 'ongoing'.

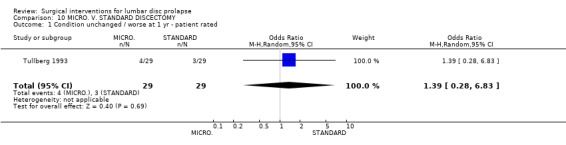

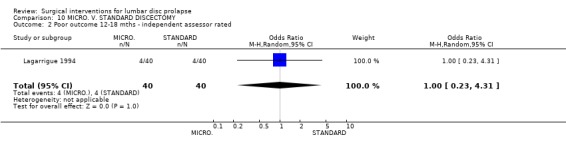

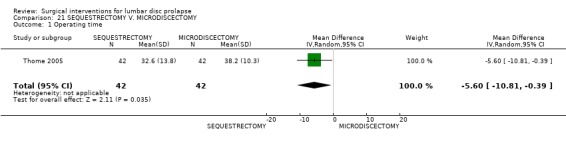

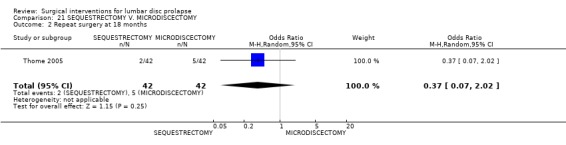

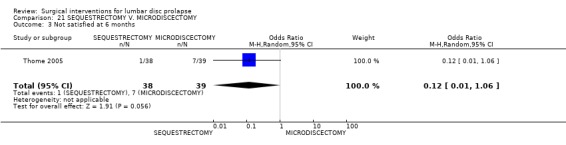

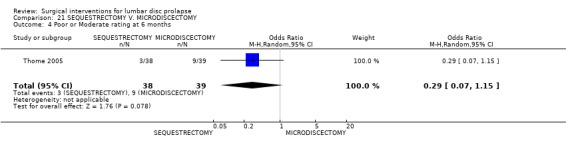

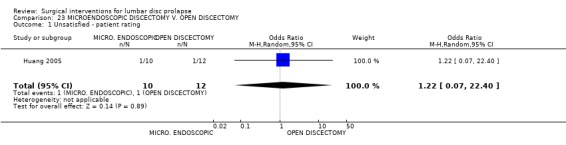

Nine of the forty‐two trials were of different forms or techniques of surgical discectomy. Three trials compared microdiscectomy (Tullberg 1993; Lagarrigue 1994; Henriksen 1996) and one micro‐endoscopic discectomy (Huang 2005) with standard discectomy. Use of the microscope lengthened the operative procedure, but did not appear to make any significant difference to peri‐operative bleeding or other complications, length of in‐patient stay, or the formation of scar tissue. Clinical outcome data were not comparable and could not be pooled. The place for micro‐endoscopic discectomy (Huang 2005) is uncertain as the number of patients studied (22) was too small to draw any clear conclusions. Data from a further trial by Hermantin (Hermantin 1999) and from a now excluded trial (Chung 1999) suggest that video arthroscopy may be worth further study. One trial (Thome 2005) compared early outcomes and recurrence rates after sequestrectomy and microdiscectomy. There was a trend toward better outcome and a lesser rate of secondary surgery after sequestrectomy alone, than after removal of the herniated material and resection of disc tissue from the intervertebral space.

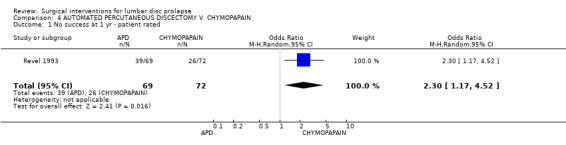

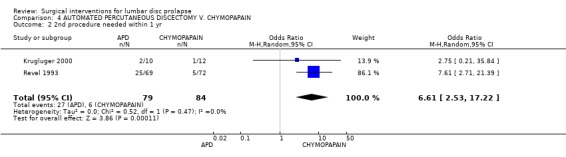

Two trials (Revel 1993; Krugluger 2000) compared automated percutaneous discectomy (APD) with chymopapain and two compared it with microdiscectomy (Chatterjee 1995; Haines 2002). Results from these trials suggest that APD produces inferior results to either more established procedure. However, we do note that Onik (Onik 1990), the original proponent of APD, suggested that the therapy was only suitable for small‐sized herniations, strictly localized in front of the intervertebral space and without a tear of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Ideally, the disc herniation should not occupy more than 30% of the spinal canal. This figure was clearly exceeded in Revel's series (Revel 1993) in which the disc herniation size was 25 to 50% in 59% of the APD and 63% of the chemonucleolysis patients. A fifth trial compared percutaneous endoscopic discectomy (cannula inserted into the central disc) with microdiscectomy (Mayer 1993). This trial showed comparable clinical outcomes after the two procedures but the study group of 40 patients was small. No trial looked specifically at transforaminal endoscopic discectomy or foraminotomy.

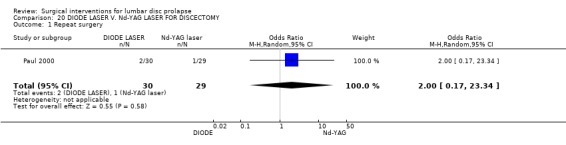

There are now two included trials of laser discectomy. In their QRCT, Paul and Hellinger (Paul 2000) compared the effects of a Nd‐YAG‐laser (1064 nm) with that of a diode laser (940 nm). Both produced only slight vaporisation but excellent shrinkage of disc tissue. However, no comparative outcome results were published. Steffen and Wittenberg (Steffen 1996) published three abstracts detailing results from a comparative study of chemonucleolysis and laser discectomy. The limited results favoured chemonucleolysis. In a third trial, no significant difference was demonstrated between outcomes following laser use and that obtained after an epidural injection (Livesey 2000) but the trial was aborted before its conclusion and therefore 'excluded'. Statistical pooling was not possible due to the clinical heterogeneity of the trials and there were insufficient data to calculate effect size.

b) Chemonucleolysis

Seventeen of the forty‐two trials were of some form of chemonucleolysis. Use of chymopapain is now rare, so this may turn out to be a final summary of the historical evidence on chemonucleolysis.

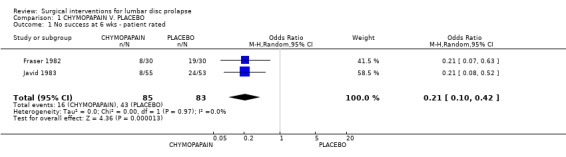

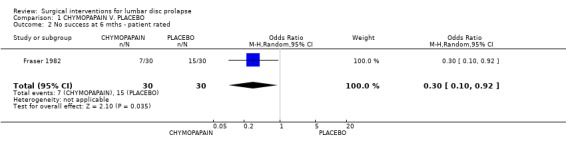

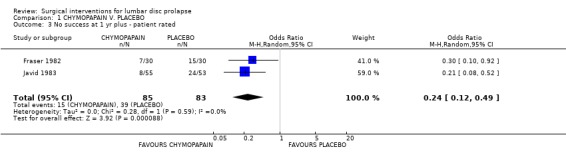

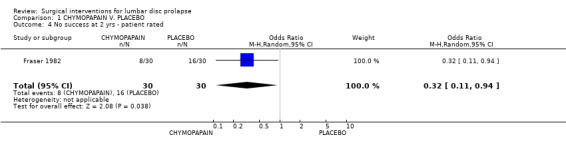

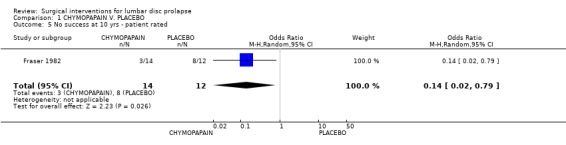

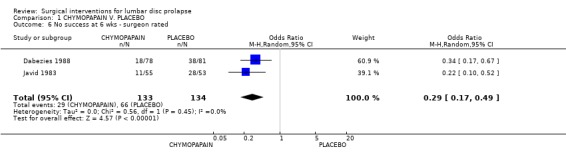

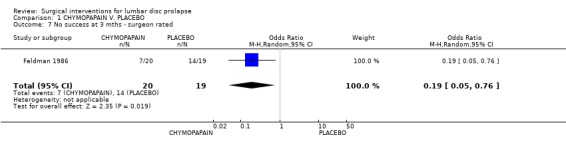

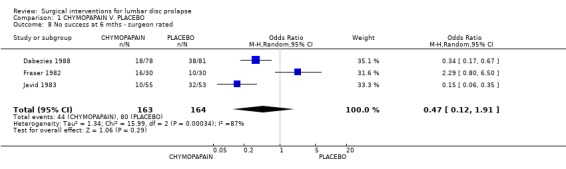

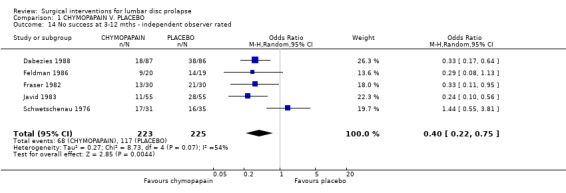

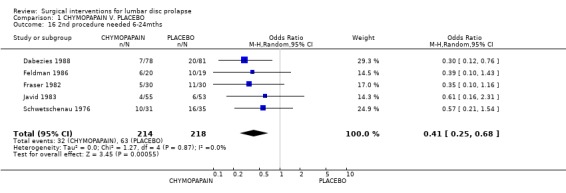

Five trials (Schwetschenau 1976; Fraser 1982; Javid 1983; Feldman 1986; Dabezies 1988) compared the efficacy of chemonucleolysis using chymopapain versus placebo. These trials had the highest quality scores in this review, with generally adequate randomization, double‐blinding, and independent outcome assessment. In all the trials, chymopapain was injected by standard technique. The combined results from the five trials compared data from 446 patients with an average follow up of 97%, and are summarised in the analysis tables. The meta‐analysis clearly showed that chymopapain was more effective than placebo whether rated by the patients (random effects model OR 0.24; 95%CI 0.12 to 0.49; Graph 01.03), or rated by surgeons conducting the study or an independent observer (random OR 0.40; 95%CI 0.21 to 0.75; Graph 01.14). Fewer patients after chymopapain injection proceeded to open discectomy (random OR 0.41; 95%CI 0.25 to 0.68; Graph 01.16).

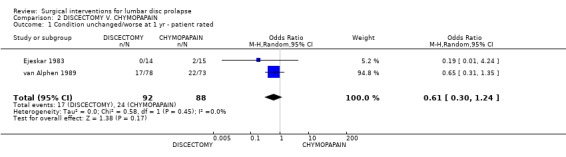

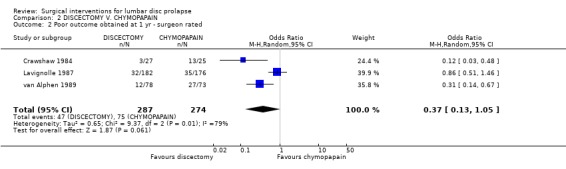

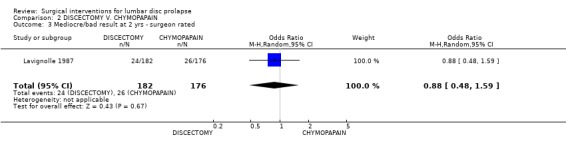

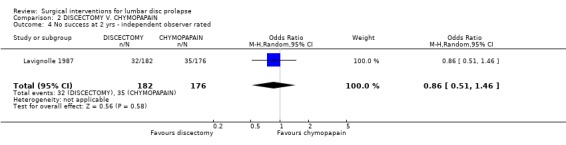

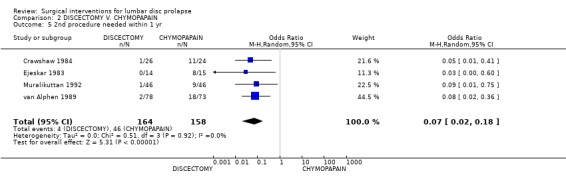

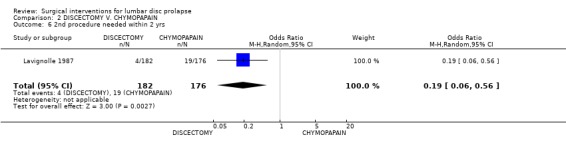

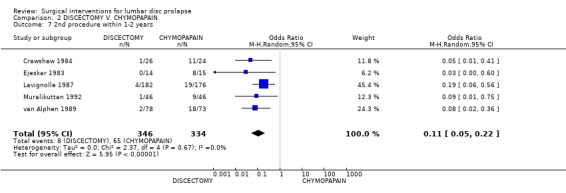

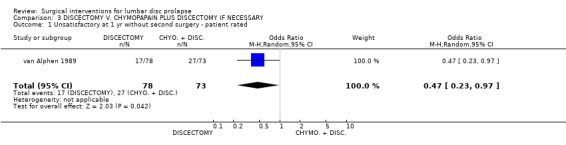

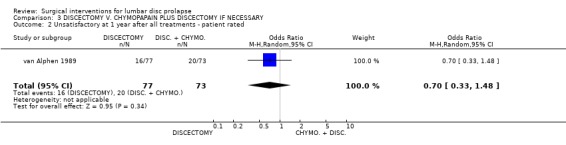

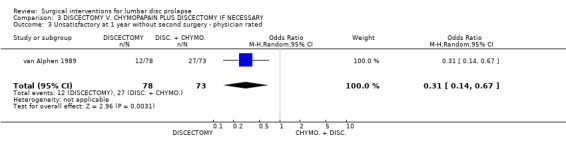

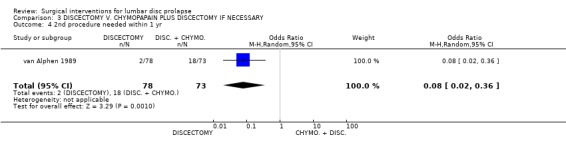

Another five trials (Ejeskar 1983; Crawshaw 1984; Lavignolle 1987; van Alphen 1989; Muralikuttan 1992), one of which was a QRCT (van Alphen 1989), compared chemonucleolysis using chymopapain and surgical discectomy. In each instance, a set dose of chymopapain was injected by standard technique, and compared with standard discectomy. In all the trials there was a poor description of the method of randomization and the nature of these studies precluded blinding of the patients. The combined results from the five trials compared data from 680 patients with an average follow up of 97%, and are summarised in the analysis tables. Note that the test for homogeneity was significant in this group of trials. Nevertheless, there is strong clinical rationale for pooling this group of trials and in view of the clinical importance of the issue these results are presented as the best available information at present, with the qualification that there may be statistical weaknesses to the results. All of the analyses showed consistently poorer results with chemonucleolysis, though this did not reach statistical significance in the random effects model. Two trials (Ejeskar 1983; van Alphen 1989) showed a worse result at one year as rated by the patients (random OR 0.61; 95%CI 0.30 to 1.24; Graph 02.01). Three trials (Crawshaw 1984; Lavignolle 1987; van Alphen 1989) showed a poorer result at one year as rated by the surgeon (fixed OR 0.52; 95%CI 0.35 to 0.78; graph not shown; random OR 0.37; 95%CI 0.13 to 1.05; Graph 02.02). About 30% of patients with chemonucleolysis had further disc surgery within two years, and meta‐analysis showed that a second procedure was more likely after chemonucleolysis (random OR 0.07; 95%CI 0.02 to 0.18; Graph 02.05). However, chemonucleolysis is a less invasive procedure, which may be regarded as an intermediate stage between conservative and surgical treatment, and surgery following failed chemonucleolysis is not strictly comparable to repeat surgery after failed discectomy. There was some suggestion that the results of discectomy after failed chemonucleolysis are poorer than primary discectomy, but there were insufficient data to allow meta‐analysis and in any event, the patient sub‐groups so derived were unlikely to be comparable. The main meta‐analysis shows that the final outcome of patients treated by chemonucleolysis, including the effects of further surgery if chemonucleolysis failed, remained poorer than those treated by primary discectomy.

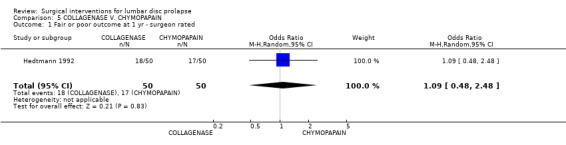

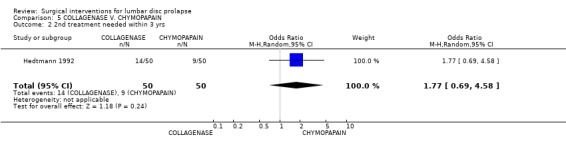

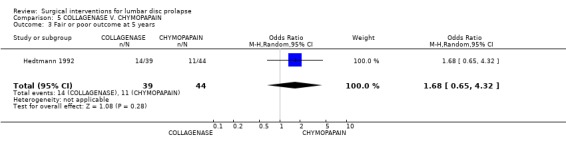

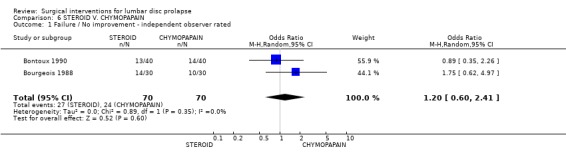

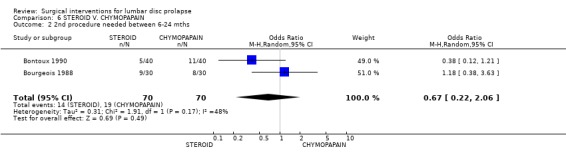

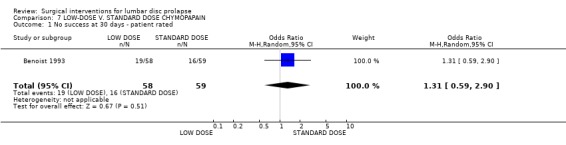

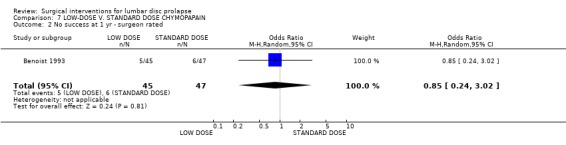

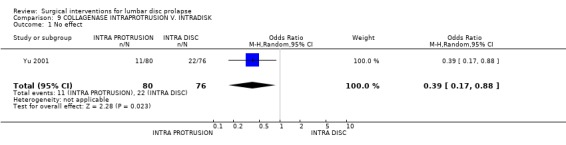

No statistically significant differences were demonstrated between low dose and standard dose chymopapain (Benoist 1993), between chymopapain and collagenase (Hedtmann 1992), or between chymopapain and steroid injection (Bourgeois 1988; Bontoux 1990). It should be noted that although one trial suggested that collagenase was more effective than placebo, that was a small study and there was 40% code break by eight weeks (Bromley 1984). A single study (Yu 2001) shows a marginally better effect of collagenase if injected into a disc protrusion rather than into the main disc itself.

c) Barrier membranes

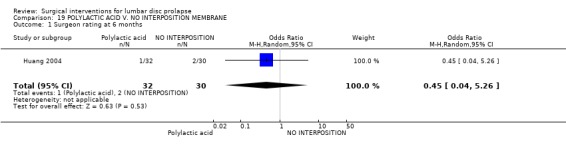

Eight trials considered the effect of different types of inter‐position membrane on the formation of intra‐spinal scarring following discectomy, as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging or enhanced computerised tomography. Three of the trials (MacKay 1995; Jensen 1996; Bernsmann 2001) failed to show any improvement in clinical outcomes following use of fat or gelfoam, although a lesser number of painful episodes one year after surgery was recorded in a fourth trial (Gambardella 2005). There are three trials of ADCON‐L an anti‐adhesion gel derived from porcine collagen and dextran sulfate. Results from the European (De Tribolet 1998; Richter 2001) and U.S. (Geisler 1999) multicentre studies show conflicting results. Twelve month results are reported from a pilot study of Oxiplex/SP gel (Kim 2004). Although there is a trend suggesting that treatment diminishes leg pain severity and lower limb weakness, the study had very low power and the results reported are not significant. A polylactic acid membrane was shown to prevent epidural scar adhesion without effect on outcome (Huang 2004).

Discussion

The results from 40 RCTs and two QRCTs of surgical interventions for lumbar disc prolapse are now presented, including 17 new trials since the first issue of this review. Although, as we have pointed out, there were many weaknesses of trial design and data have to be interpreted with caution, it is possible to draw a number of provisional conclusions.

The trial by Weber ( Weber 1983) is widely quoted as a direct comparison of discectomy and conservative treatment, and as showing a temporary benefit in clinical outcomes at one year, but no difference on longer term follow up at four and ten years. We believe that this is an inaccurate interpretation of the results (See also Bessette 1996 for a critique of this trial). Weber (Weber 1983) actually reported on a subgroup of patients with uncertain indications for surgery: of a total series of 280 patients, 67 were considered to have definite indications for surgery, 87 patients improved with conservative management, and only the intermediate 126 were randomised in the trial. The intervention consisted of primary discectomy compared with initial conservative management followed by discectomy as soon as clinically considered necessary if the patient failed to improve. The trial did show clearly that discectomy produced better clinical outcomes at one year, particularly for relief of sciatica. What it also showed is that if the clinical indications are uncertain, postponing surgery to further assess clinical progress may delay recovery but does not produce long‐term harm. There are now three further trials comparing discectomy with conservative treatment (Greenfield 2003; Butterman 2004; Weinstein 2006), the conclusions of which appear broadly comparable to those from Weber.

At present, the best scientific evidence on the effectiveness of discectomy still comes from chemonucleolysis. There is strong evidence that discectomy is more effective than chemonucleolysis and that chemonucleolysis is more effective than placebo: ergo, discectomy is more effective than placebo. This is entirely consistent with systematic reviews (Hoffman 1993; Stevens 1997) of non‐RCT series of discectomy and many clinical series which have shown consistently that 65% to 90% of patients get good or excellent outcomes, particularly for the relief of sciatica and for at least six to 24 months, compared with 36% of conservatively treated patients (Hoffman 1993). It is not possible to draw any conclusions about indications for surgery from the present review of RCTs, but these other reviews (Hoffman 1993; Stevens 1997) provide evidence on the need for careful selection of patients. All of this evidence confirms clinical experience and teaching that the primary benefit of discectomy is to provide more rapid relief of sciatica in those patients who have failed to resolve with conservative management, even if there is no clear evidence that surgery alters the long‐term natural history or prognosis of the underlying disc disease. The medium‐term clinical outcomes have been sufficiently consistent for discectomy to survive the test of time in widespread clinical practice for more than 60 years.

This review also provides evidence on a number of technical questions about discectomy. There is moderate evidence from three trials that the clinical outcomes of microdiscectomy are comparable to those of standard discectomy. In principle, the microscope provides better illumination and facilitates teaching. These trials suggest that use of the microscope lengthens the operative procedure, but despite previous concerns, they did not show any significant difference in peri‐operative bleeding, length of in‐patient stay, or the formation of scar tissue. It is probable that some form of interposition membrane may reduce scarring after discectomy, although there is no clear evidence on clinical outcomes.

Enthusiasm for chemonucleolysis with chymopapain has waxed and waned. After forty years, there remains good evidence on its effectiveness: five generally high quality trials show that chemonucleolysis produces better clinical outcomes than placebo, and one trial showed that these outcomes are maintained for ten years. Conversely, however, there is strong evidence that chemonucleolysis does not produce as good clinical outcomes as discectomy, even if that must be balanced against a lower overall complication rate (Bouillet 1987). Moreover, a significant proportion of patients progress to surgery anyway after failed chemonucleolysis and their final outcome may not be quite as good. Rationally, chemonucleolysis is a minimally invasive procedure, that might be considered as an intermediate stage between conservative management and open surgical intervention, and could save about 70% of patients from requiring open surgery. It is then a matter of debate about the relative balance of possibly avoiding surgery, relative risks and complication rates, clinical outcomes over the next year or so, and the potential impact on the lifetime natural history of disc disease. In current practice, that balance of advantages and disadvantages has put chemonucleolysis out of favour.

The place for other forms of discectomy is unresolved. Trials of automated percutaneous discectomy and laser discectomy suggest that clinical outcomes following treatment are at best fair and certainly worse than after microdiscectomy, although the importance of patient selection (see results) is acknowledged. There are no RCTs examining intradiscal electrotherapy or coblation as a treatment for disc prolapse, nor as yet any comparing transforaminal endoscopic (arthroscopic) discectomy advocated for small sub‐ligamentous prolapse

Although a few trials report the number of patients who return to work after treatment, there are insufficient data to draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of any of these surgical treatments on capacity for work. Readers are referred to older, non‐RCT reviews and discussions by Taylor and Scheer (Taylor 1989; Scheer 1996).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Epidemiological and clinical studies show that most lumbar disc prolapses resolve naturally with conservative management and the passage of time, and without surgery.

There is considerable evidence that surgical discectomy provides effective clinical relief for carefully selected patients with sciatica due to lumbar disc prolapse that fails to resolve with conservative management. It provides faster relief from the acute attack of sciatica, although any positive or negative effects on the long‐term natural history of the underlying disc disease are unclear. There is still a lack of scientific evidence on the optimal timing of surgery.

The choice of micro‐ or standard discectomy at present probably depends more on the training and expertise of the surgeon, and the resources available, than on scientific evidence of efficacy. However, it is worth noting that some form of magnification is now used almost universally in major spinal surgical units to facilitate vision.

At present, unless or until better scientific evidence is available, automated percutaneous discectomy, coblation therapy and laser discectomy should be regarded as research techniques.

Implications for research.

The quality of surgical RCTs still needs to be improved, particularly on the issues of sufficient power, adequate randomization, blinding, duration of follow‐up and better clinical outcome measures. There are major gaps in our knowledge on the costs and cost‐effectiveness of all forms of surgical treatment of lumbar disc prolapse. Authors of future surgical RCTs should seek expert methodological advice at the planning stage.

There is still a need for more and better evidence on a) the optimal selection and timing of surgical treatment in the over‐all and long‐term management strategy for disc disease, b) the outcomes of discectomy versus conservative management, and c) the relative clinical outcomes, morbidity, costs and cost‐effectiveness of micro‐ versus standard discectomy. High quality RCTs are required to determine if there is any role for automated percutaneous discectomy or laser discectomy. There is a major need for long‐term studies into the effects of surgery on the lifetime natural history of disc disease and on occupational outcomes.

This Cochrane review should continue to be maintained and updated as further RCTs become available. The authors will be pleased to receive information about any new RCTs of surgical treatment of lumbar disc prolapse.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1997 Review first published: Issue 1, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 January 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Although there were many weaknesses of trial design and data have to be interpreted with caution, it is possible to draw a number of provisional conclusions. Surgical discectomy for carefully selected patients with sciatica due to lumbar disc prolapse provides faster relief from the acute attack than conservative management. Any positive or negative effects on the lifetime natural history of the underlying disc disease are still unclear and there is still a lack of scientific evidence on the optimal timing of surgery. Microdiscectomy gives broadly comparable results to open discectomy. The evidence on other minimally invasive techniques remains unclear (with the exception of chemonucleolysis using chymopapain, which is no longer widely available). |

| 1 January 2007 | New search has been performed | The results from 40 RCTs and two QRCTs of surgical treatment for lumbar disc prolapse are now presented, including 17 new trials since the first issue of this review in 1999. |

Acknowledgements

Ms Inga Grant was a co‐author on the original review. We are grateful to Professor WJ Gillespie, and Dr Helen Handoll of the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Review Group Editorial Board for their encouragement and to the late Professor A Nachemson for continuing assistance in the literature search and retrieval. We are also grateful to Clarus Medical, Mn, USA for providing a detailed analysis of the literature pertaining to percutaneous discectomy for contained herniated lumbar disc. The editorial staff of the Cochrane Back Review Group provided professional support in preparation of this manuscript; Ms Hilda Bastian (from the Cochrane Consumers Network) provided input for the original review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. INTERVERTEBRAL‐DISK‐CHEMOLYSIS / all subheadings 2. CHYMOPAPAIN 3. CHEMONUCLEOLYSIS 4. INTERVERTEBRAL near DISK near CHEMOLYSIS 5. INTERVERTEBRAL‐DISK‐DISPLACEMENT / without‐subheadings, complications, drug‐therapy, economics, enzymology, immunology, mortality, nursing, rehabilitation, surgery, therapy 6. SPINAL‐STENOSIS / without‐subheadings, complications, drug‐therapy, economics, enzymology, mortality, nursing, rehabilitation, surgery, therapy 7. SLIPPED near (DISC or DISCS or DISK or DISKS) 8. STENOSIS near SPINE* or ROOT or SPINAL 9. DISPLACE* near (DISC or DISCS or DISK or DISKS) 10. PROLAP* near (DISC or DISCS or DISK or DISKS) 11. LUMBAR‐VERTEBRA* / injuries, surgery 12. explode DISKECTOMY / all subheadings 13. explode LASER‐SURGERY / all subheadings 14. #12 and #13 15. DISCECTOMY or DISKECTOMY 16. #13 and #15 17. PERCUTANEOUS and #15 18. ENDOSCOPIC and #15 19. BACK‐PAIN / without‐subheadings, complications, mortality, surgery, therapy, economics, rehabilitation 20. LOW‐BACK‐PAIN / without‐subheadings, complications, mortality, surgery, therapy, economics, rehabilitation 21. CAUDA EQUINA / without‐subheadings, drug effect* 22. CAUDA near COMPRESS* 23. ENZYME*‐THERAPEUTIC‐USE 24. ENZYME* near INJECTION 25. (INTRADISC* or INTRADISK*) near (STEROID* orTRIAMCINOLONE) 26. COLLAGENASE* 27. #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #14 or #16 or #17 or # #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No success at 6 wks ‐ patient rated | 2 | 168 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.10, 0.42] |

| 2 No success at 6 mths ‐ patient rated | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.10, 0.92] |

| 3 No success at 1 yr plus ‐ patient rated | 2 | 168 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.12, 0.49] |

| 4 No success at 2 yrs ‐ patient rated | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.11, 0.94] |

| 5 No success at 10 yrs ‐ patient rated | 1 | 26 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.14 [0.02, 0.79] |

| 6 No success at 6 wks ‐ surgeon rated | 2 | 267 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.17, 0.49] |

| 7 No success at 3 mths ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 39 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.05, 0.76] |

| 8 No success at 6 mths ‐ surgeon rated | 3 | 327 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.12, 1.91] |

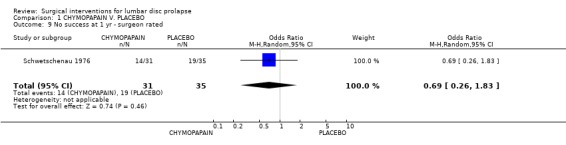

| 9 No success at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 66 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.26, 1.83] |

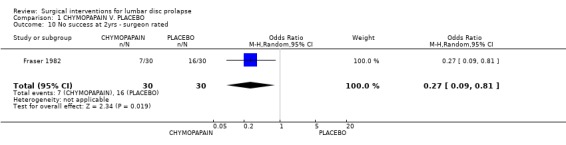

| 10 No success at 2yrs ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.09, 0.81] |

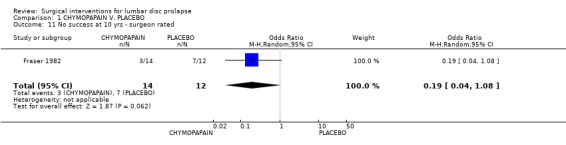

| 11 No success at 10 yrs ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 26 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.04, 1.08] |

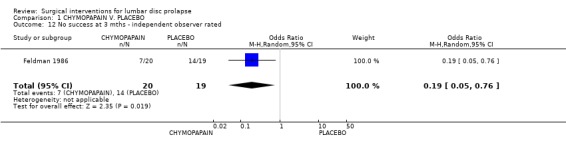

| 12 No success at 3 mths ‐ independent observer rated | 1 | 39 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.05, 0.76] |

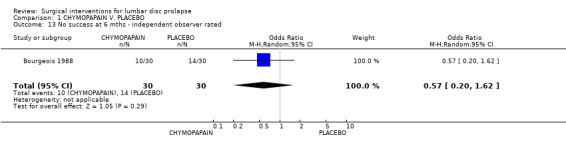

| 13 No success at 6 mths ‐ independent observer rated | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.20, 1.62] |

| 14 No success at 3‐12 mths ‐ independent observer rated | 5 | 448 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.22, 0.75] |

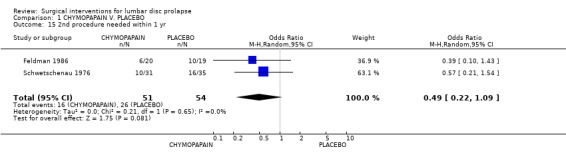

| 15 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr | 2 | 105 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.22, 1.09] |

| 16 2nd procedure needed 6‐24mths | 5 | 432 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.25, 0.68] |

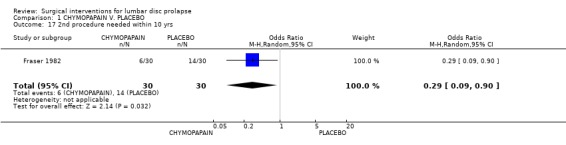

| 17 2nd procedure needed within 10 yrs | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.09, 0.90] |

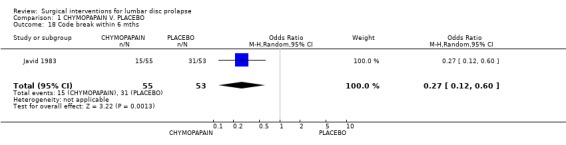

| 18 Code break within 6 mths | 1 | 108 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.12, 0.60] |

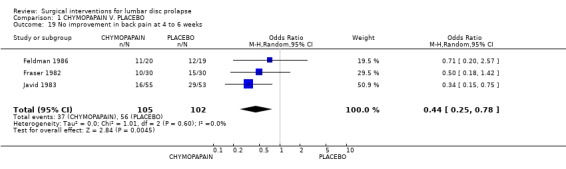

| 19 No improvement in back pain at 4 to 6 weeks | 3 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.25, 0.78] |

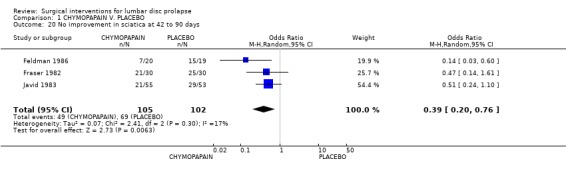

| 20 No improvement in sciatica at 42 to 90 days | 3 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.20, 0.76] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 1 No success at 6 wks ‐ patient rated.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 2 No success at 6 mths ‐ patient rated.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 3 No success at 1 yr plus ‐ patient rated.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 4 No success at 2 yrs ‐ patient rated.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 5 No success at 10 yrs ‐ patient rated.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 6 No success at 6 wks ‐ surgeon rated.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 7 No success at 3 mths ‐ surgeon rated.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 8 No success at 6 mths ‐ surgeon rated.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 9 No success at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 10 No success at 2yrs ‐ surgeon rated.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 11 No success at 10 yrs ‐ surgeon rated.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 12 No success at 3 mths ‐ independent observer rated.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 13 No success at 6 mths ‐ independent observer rated.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 14 No success at 3‐12 mths ‐ independent observer rated.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 15 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 16 2nd procedure needed 6‐24mths.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 17 2nd procedure needed within 10 yrs.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 18 Code break within 6 mths.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 19 No improvement in back pain at 4 to 6 weeks.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CHYMOPAPAIN V. PLACEBO, Outcome 20 No improvement in sciatica at 42 to 90 days.

Comparison 2. DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Condition unchanged/worse at 1 yr ‐ patient rated | 2 | 180 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.30, 1.24] |

| 2 Poor outcome obtained at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated | 3 | 561 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.13, 1.05] |

| 3 Mediocre/bad result at 2 yrs ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 358 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.48, 1.59] |

| 4 No success at 2 yrs ‐ independent observer rated | 1 | 358 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.51, 1.46] |

| 5 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr | 4 | 322 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.07 [0.02, 0.18] |

| 6 2nd procedure needed within 2 yrs | 1 | 358 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.06, 0.56] |

| 7 2nd procedure within 1‐2 years | 5 | 680 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.05, 0.22] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 Condition unchanged/worse at 1 yr ‐ patient rated.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 Poor outcome obtained at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 3 Mediocre/bad result at 2 yrs ‐ surgeon rated.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 4 No success at 2 yrs ‐ independent observer rated.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 5 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 6 2nd procedure needed within 2 yrs.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 7 2nd procedure within 1‐2 years.

Comparison 3. DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN PLUS DISCECTOMY IF NECESSARY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Unsatisfactory at 1 yr without second surgery ‐ patient rated | 1 | 151 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.47 [0.23, 0.97] |

| 2 Unsatisfactory at 1 year after all treatments ‐ patient rated | 1 | 150 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.33, 1.48] |

| 3 Unsatisfactory at 1 year without second surgery ‐ physician rated | 1 | 151 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.14, 0.67] |

| 4 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr | 1 | 151 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.08 [0.02, 0.36] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN PLUS DISCECTOMY IF NECESSARY, Outcome 1 Unsatisfactory at 1 yr without second surgery ‐ patient rated.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN PLUS DISCECTOMY IF NECESSARY, Outcome 2 Unsatisfactory at 1 year after all treatments ‐ patient rated.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN PLUS DISCECTOMY IF NECESSARY, Outcome 3 Unsatisfactory at 1 year without second surgery ‐ physician rated.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN PLUS DISCECTOMY IF NECESSARY, Outcome 4 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr.

Comparison 4. AUTOMATED PERCUTANEOUS DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No success at 1 yr ‐ patient rated | 1 | 141 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.3 [1.17, 4.52] |

| 2 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr | 2 | 163 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.61 [2.53, 17.22] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 AUTOMATED PERCUTANEOUS DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 No success at 1 yr ‐ patient rated.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 AUTOMATED PERCUTANEOUS DISCECTOMY V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 2nd procedure needed within 1 yr.

Comparison 5. COLLAGENASE V. CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fair or poor outcome at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.48, 2.48] |

| 2 2nd treatment needed within 3 yrs | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.77 [0.69, 4.58] |

| 3 Fair or poor outcome at 5 years | 1 | 83 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.68 [0.65, 4.32] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 COLLAGENASE V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 Fair or poor outcome at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 COLLAGENASE V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 2nd treatment needed within 3 yrs.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 COLLAGENASE V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 3 Fair or poor outcome at 5 years.

Comparison 6. STEROID V. CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Failure / No improvement ‐ independent observer rated | 2 | 140 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.60, 2.41] |

| 2 2nd procedure needed between 6‐24 mths | 2 | 140 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.22, 2.06] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 STEROID V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 Failure / No improvement ‐ independent observer rated.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 STEROID V. CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 2nd procedure needed between 6‐24 mths.

Comparison 7. LOW‐DOSE V. STANDARD DOSE CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No success at 30 days ‐ patient rated | 1 | 117 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.59, 2.90] |

| 2 No success at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 92 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.24, 3.02] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 LOW‐DOSE V. STANDARD DOSE CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 No success at 30 days ‐ patient rated.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 LOW‐DOSE V. STANDARD DOSE CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 No success at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated.

Comparison 8. COLLAGENASE V. PLACEBO.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Poor result obtained at 17 mths ‐ patient rated | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.04, 0.67] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 COLLAGENASE V. PLACEBO, Outcome 1 Poor result obtained at 17 mths ‐ patient rated.

Comparison 9. COLLAGENASE INTRAPROTRUSION V. INTRADISK.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No effect | 1 | 156 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.17, 0.88] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 COLLAGENASE INTRAPROTRUSION V. INTRADISK, Outcome 1 No effect.

Comparison 10. MICRO. V. STANDARD DISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Condition unchanged / worse at 1 yr ‐ patient rated | 1 | 58 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [0.28, 6.83] |

| 2 Poor outcome 12‐18 mths ‐ independent assessor rated | 1 | 80 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.23, 4.31] |

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 MICRO. V. STANDARD DISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Condition unchanged / worse at 1 yr ‐ patient rated.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 MICRO. V. STANDARD DISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 Poor outcome 12‐18 mths ‐ independent assessor rated.

Comparison 11. DISCECTOMY V. CONSERVATIVE ± DISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Poor/bad result at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 125 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.12, 1.02] |

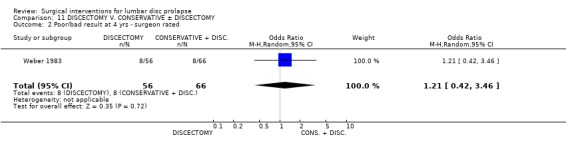

| 2 Poor/bad result at 4 yrs ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 122 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.42, 3.46] |

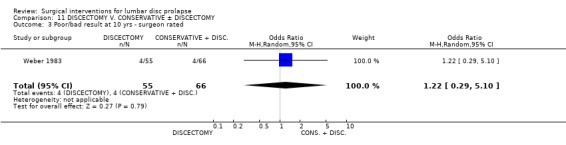

| 3 Poor/bad result at 10 yrs ‐ surgeon rated | 1 | 121 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.29, 5.10] |

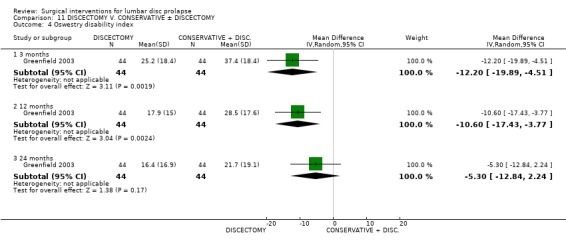

| 4 Oswestry disability index | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 3 months | 1 | 88 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐12.2 [‐19.89, ‐4.51] |

| 4.2 12 months | 1 | 88 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.60 [‐17.43, ‐3.77] |

| 4.3 24 months | 1 | 88 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.30 [‐12.84, 2.24] |

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 DISCECTOMY V. CONSERVATIVE ± DISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Poor/bad result at 1 yr ‐ surgeon rated.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 DISCECTOMY V. CONSERVATIVE ± DISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 Poor/bad result at 4 yrs ‐ surgeon rated.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 DISCECTOMY V. CONSERVATIVE ± DISCECTOMY, Outcome 3 Poor/bad result at 10 yrs ‐ surgeon rated.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 DISCECTOMY V. CONSERVATIVE ± DISCECTOMY, Outcome 4 Oswestry disability index.

Comparison 12. PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) V. MICRODISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

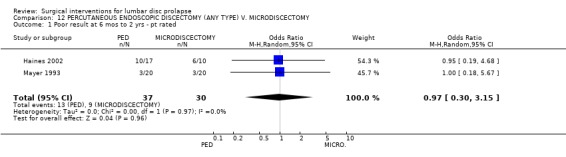

| 1 Poor result at 6 mos to 2 yrs ‐ pt rated | 2 | 67 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.30, 3.15] |

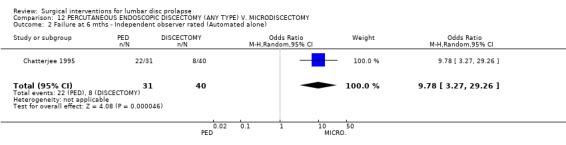

| 2 Failure at 6 mths ‐ Independent observer rated (Automated alone) | 1 | 71 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 9.78 [3.27, 29.26] |

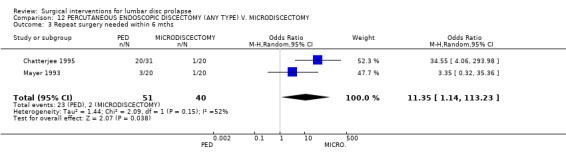

| 3 Repeat surgery needed within 6 mths | 2 | 91 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 11.35 [1.14, 113.23] |

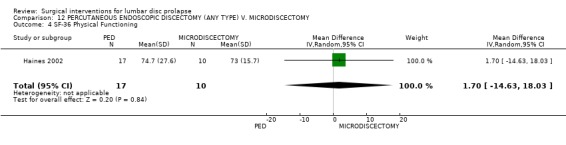

| 4 SF‐36 Physical Functioning | 1 | 27 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.70 [‐14.63, 18.03] |

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Poor result at 6 mos to 2 yrs ‐ pt rated.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 Failure at 6 mths ‐ Independent observer rated (Automated alone).

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 3 Repeat surgery needed within 6 mths.

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 4 SF‐36 Physical Functioning.

Comparison 13. PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) AND SUBSEQUENT MICRODISCECTOMY IF FAILURE V. MICRODISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No success at 2 yrs ‐ Patient rated | 1 | 40 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.01, 2.53] |

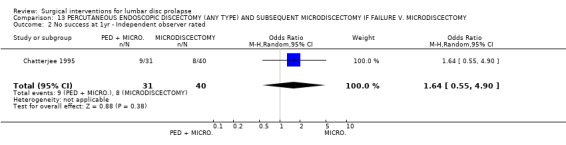

| 2 No success at 1yr ‐ Independent observer rated | 1 | 71 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.64 [0.55, 4.90] |

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) AND SUBSEQUENT MICRODISCECTOMY IF FAILURE V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 No success at 2 yrs ‐ Patient rated.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY (ANY TYPE) AND SUBSEQUENT MICRODISCECTOMY IF FAILURE V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 No success at 1yr ‐ Independent observer rated.

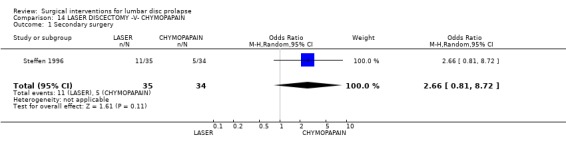

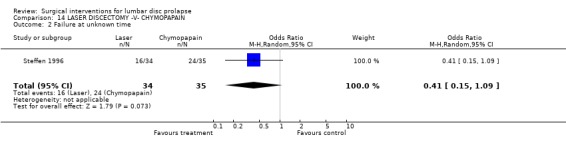

Comparison 14. LASER DISCECTOMY ‐V‐ CHYMOPAPAIN.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Secondary surgery | 1 | 69 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.66 [0.81, 8.72] |

| 2 Failure at unknown time | 1 | 69 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.15, 1.09] |

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 LASER DISCECTOMY ‐V‐ CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 1 Secondary surgery.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 LASER DISCECTOMY ‐V‐ CHYMOPAPAIN, Outcome 2 Failure at unknown time.

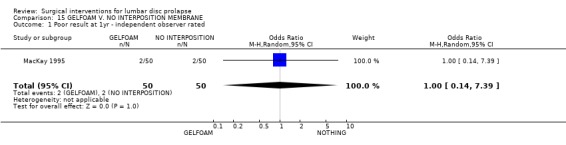

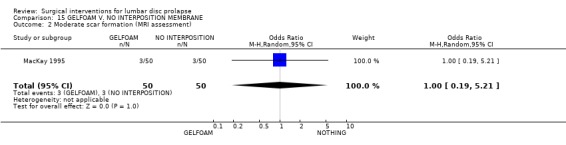

Comparison 15. GELFOAM V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Poor result at 1yr ‐ independent observer rated | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.14, 7.39] |

| 2 Moderate scar formation (MRI assessment) | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.19, 5.21] |

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 GELFOAM V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 1 Poor result at 1yr ‐ independent observer rated.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 GELFOAM V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 2 Moderate scar formation (MRI assessment).

Comparison 16. FREE FAT GRAFT V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

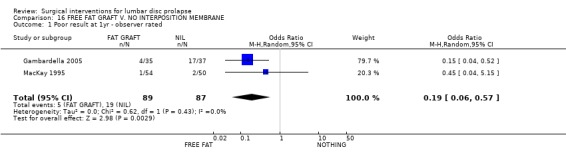

| 1 Poor result at 1yr ‐ observer rated | 2 | 176 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.06, 0.57] |

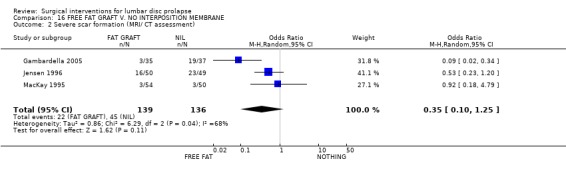

| 2 Severe scar formation (MRI/ CT assessment) | 3 | 275 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.10, 1.25] |

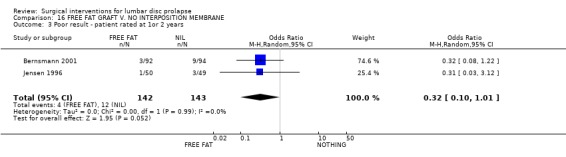

| 3 Poor result ‐ patient rated at 1or 2 years | 2 | 285 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.10, 1.01] |

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 FREE FAT GRAFT V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 1 Poor result at 1yr ‐ observer rated.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 FREE FAT GRAFT V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 2 Severe scar formation (MRI/ CT assessment).

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 FREE FAT GRAFT V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 3 Poor result ‐ patient rated at 1or 2 years.

Comparison 17. VIDEO‐ASSISTED ARTHROSCOPIC MICRODISCECTOMY V. OPEN DISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Poor result ‐ Surgeon rated at 2 years | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.04, 5.63] |

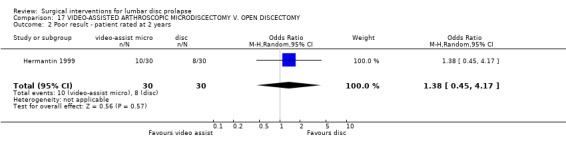

| 2 Poor result ‐ patient rated at 2 years | 1 | 60 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.45, 4.17] |

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 VIDEO‐ASSISTED ARTHROSCOPIC MICRODISCECTOMY V. OPEN DISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Poor result ‐ Surgeon rated at 2 years.

17.2. Analysis.

Comparison 17 VIDEO‐ASSISTED ARTHROSCOPIC MICRODISCECTOMY V. OPEN DISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 Poor result ‐ patient rated at 2 years.

Comparison 18. ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

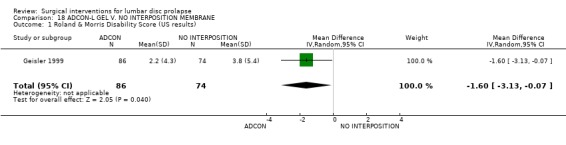

| 1 Roland & Morris Disability Score (US results) | 1 | 160 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.60 [‐3.13, ‐0.07] |

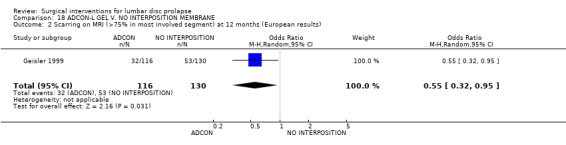

| 2 Scarring on MRI (>75% in most involved segment) at 12 months (European results) | 1 | 246 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.32, 0.95] |

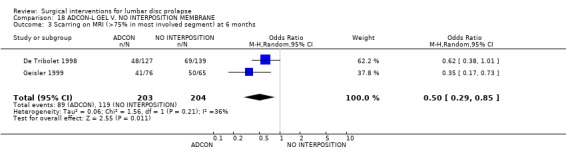

| 3 Scarring on MRI (>75% in most involved segment) at 6 months | 2 | 407 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.29, 0.85] |

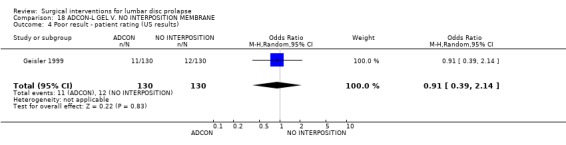

| 4 Poor result ‐ patient rating (US results) | 1 | 260 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.39, 2.14] |

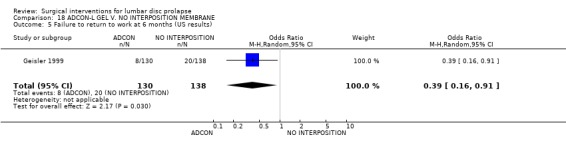

| 5 Failure to return to work at 6 months (US results) | 1 | 268 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.16, 0.91] |

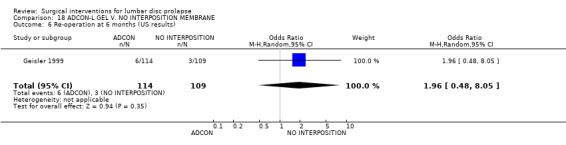

| 6 Re‐operation at 6 months (US results) | 1 | 223 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.96 [0.48, 8.05] |

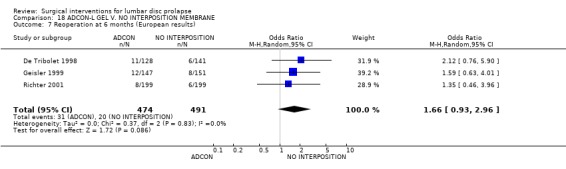

| 7 Reoperation at 6 months (European results) | 3 | 965 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.66 [0.93, 2.96] |

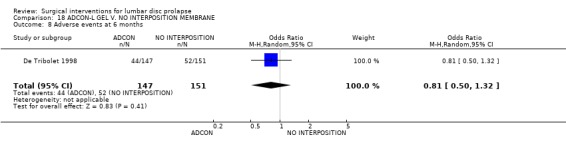

| 8 Adverse events at 6 months | 1 | 298 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.50, 1.32] |

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 1 Roland & Morris Disability Score (US results).

18.2. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 2 Scarring on MRI (>75% in most involved segment) at 12 months (European results).

18.3. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 3 Scarring on MRI (>75% in most involved segment) at 6 months.

18.4. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 4 Poor result ‐ patient rating (US results).

18.5. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 5 Failure to return to work at 6 months (US results).

18.6. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 6 Re‐operation at 6 months (US results).

18.7. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 7 Reoperation at 6 months (European results).

18.8. Analysis.

Comparison 18 ADCON‐L GEL V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 8 Adverse events at 6 months.

Comparison 19. POLYLACTIC ACID V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Surgeon rating at 6 months | 1 | 62 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.04, 5.26] |

19.1. Analysis.

Comparison 19 POLYLACTIC ACID V. NO INTERPOSITION MEMBRANE, Outcome 1 Surgeon rating at 6 months.

Comparison 20. DIODE LASER V. Nd‐YAG LASER FOR DISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Repeat surgery | 1 | 59 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.17, 23.34] |

20.1. Analysis.

Comparison 20 DIODE LASER V. Nd‐YAG LASER FOR DISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Repeat surgery.

Comparison 21. SEQUESTRECTOMY V. MICRODISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Operating time | 1 | 84 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐5.60 [‐10.81, ‐0.39] |

| 2 Repeat surgery at 18 months | 1 | 84 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.07, 2.02] |

| 3 Not satisfied at 6 months | 1 | 77 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.01, 1.06] |

| 4 Poor or Moderate rating at 6 months | 1 | 77 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.07, 1.15] |

21.1. Analysis.

Comparison 21 SEQUESTRECTOMY V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Operating time.

21.2. Analysis.

Comparison 21 SEQUESTRECTOMY V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 2 Repeat surgery at 18 months.

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 SEQUESTRECTOMY V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 3 Not satisfied at 6 months.

21.4. Analysis.

Comparison 21 SEQUESTRECTOMY V. MICRODISCECTOMY, Outcome 4 Poor or Moderate rating at 6 months.

Comparison 22. MICRODISCECTOMY V. EPIDURAL STEROID.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Failure of Epidural Injection | 1 | 100 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 118.19 [6.91, 2021.71] |

22.1. Analysis.

Comparison 22 MICRODISCECTOMY V. EPIDURAL STEROID, Outcome 1 Failure of Epidural Injection.

Comparison 23. MICROENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY V. OPEN DISCECTOMY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Unsatisfied ‐ patient rating | 1 | 22 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.07, 22.40] |

23.1. Analysis.

Comparison 23 MICROENDOSCOPIC DISCECTOMY V. OPEN DISCECTOMY, Outcome 1 Unsatisfied ‐ patient rating.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Benoist 1993.

| Methods | Independently generated list Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 34/118 at 1 yr | |

| Participants | 118 pts; 80 m,8 f; age 21‐70 yrs Paris, France Lumbar disc herniation + radicular pain Unsuccessful conservative treatment (6 wks) | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (2000 Units) Ctl: chymopapain (4000 Units) |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating

Patient rating ‐ at 1 yr |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bernsmann 2001.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 14/200 at 2 yrs | |

| Participants | 200 pts; 97 m,89 f; age 22‐75 yrs Bochum, Germany | |

| Interventions | Exp: fat graft Ctl: no fat graft |

|

| Outcomes | Patient rating ‐ at 2 yrs |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bontoux 1990.

| Methods | Table randomization Blinding: assessor Lost to follow‐up: 0/80 ‐ at 6 mths | |

| Participants | 80 pts. Poitiers, France Sciatica for 2 mths | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (4000 units) Ctl: triamcinolone hexacetonide (70 mg) |

|

| Outcomes | Independent observer rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | French translation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bourgeois 1988.

| Methods | Drawing of lots Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 0/60 at 6 mths | |

| Participants | 60 pts; 40 m,20 f; age 26‐62 yrs Paris, France Sciatica for 6 wks | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (4000 units) Ctl: triamcinolone hexacetonide (80 mg) |

|

| Outcomes | Independent observer rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | French translation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Bromley 1984.

| Methods | Table randomization Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 0/30 at 17 mths | |

| Participants | 30 pts; 15 m,15 f; age 21‐63 yrs Paterson, NJ Failed conservative therapy (incl. 2 wks bed rest) Myelogram: confirming a single herniated disc | |

| Interventions | Exp: collagenase (600 units/ml) Ctl: normal saline |

|

| Outcomes | Patient rating ‐ at 17 mths |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Butterman 2004.

| Methods | Computer randomization Blinding: nil Lost to follow‐up: 3/100 | |

| Participants | 100 pts; Stillwater, MN Large herniations (>25% cross section of spinal canal) with failure of conservative treatment after 6 wks | |

| Interventions | Exp: discectomy Ctl: epidural steroid (up to 3 weekly injections) |

|

| Outcomes | Back and leg pain

ODI

2nd procedure required ‐ at 3 yrs |

|

| Notes | Steroid dose and use of fluoroscopy varied | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chatterjee 1995.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: assessor Lost to follow‐up: 0/71 at 6 mths | |

| Participants | 71 pts; 39 m,32 f; age 20‐67 yrs Liverpool, U.K. Contained disc herniation at a single level Unsuccessful conservative treatment (min. 6 wks) | |

| Interventions | Exp: automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy Ctl: microdiscectomy |

|

| Outcomes | Repeat surgery (microdiscectomy) required ‐ following failed APLD

Independent observer rating ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | Parallel study of direct/social economic costs reported in different publication (Stevenson 1995) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Crawshaw 1984.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: nil Lost to follow‐up: 2/52 at 1 yr | |

| Participants | 52 pts; age 15‐60 yrs Nottingham, U.K. Root involvement at a single level Failed conservative treatment (min. 3 mths) | |

| Interventions | Exp: chemonucleolysis (4000 units chymopapain) Ctl: surgery (choice left to surgeon) |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 1 yr |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dabezies 1988.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 9/173 at 6 mths | |

| Participants | 173 pts; 112 m,61 f; age 18‐70 yrs Multicentre, US (25 centres) Proven classic lumbar disc syndrome with unilateral single‐level radiculopathy Failed conservative treatment (min. 2 wks strict bed rest) | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (8 mg in 2 mls) Ctl: cysteine‐edetate‐iothalamate |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

De Tribolet 1998.

| Methods | Randomization by computerised paradigm Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 31/298 at 6 mths | |

| Participants | 298 pts; 167 m, 102 f; mean age 39 yrs Lausanne, Switzerland Single level disc prolapse | |

| Interventions | Exp: Adcon‐L gel Ctl: No anti‐adhesion gel |

|

| Outcomes | Post‐op scarring on MRI scan

2nd procedure

Radicular pain ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | European arm of Adcon‐L study. Some patients had a laminectomy (6) or hemilaminectomy (102) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Ejeskar 1983.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: assessor Lost to follow‐up: 0/29 at 1 yr | |

| Participants | 29 pts; 22 m,7 f; age 19‐73 yrs Gothenburg, Sweden Obvious signs + symptoms of a herniated disc Severe symptoms for longer than 4 mths positive myelogram | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (4000 IU) Ctl: surgery (laminotomy) |

|

| Outcomes | Pt rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 1 yr |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Feldman 1986.

| Methods | Drawing of lots Allocation concealment: B Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 0/39 | |

| Participants | 39 pts. Paris, France Symptoms resistant to 4 wks conservative therapy | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (4000 U) Ctl: distilled water |

|

| Outcomes | Independent observer assessment

Re‐operation ‐ at 22 mths |

|

| Notes | French translation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Fraser 1982.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated Blinding: double Lost to follow‐up: 0/60 at 2 yrs 4/60 at 10 yrs | |

| Participants | 60 pts; 39 m, 21 f; age 19‐69 yrs Adelaide, Australia Failed conservative treatment (unknown duration) within preceding 6 mths Myelogram demonstrating posterolateral herniated disc at single level | |

| Interventions | Exp: chymopapain (8 mg in 2 mls) Ctl: saline (2 mls) |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating

Patient rating

2nd procedure required ‐ at 2, 10 yrs |

|

| Notes | 6 mths, 2 yrs and 10 yrs follow‐up reported in separate publications | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Gambardella 2005.

| Methods | Randomization method not stated. Radiologist blinded. Lost to follow up 2/74 | |

| Participants | 74 pts; Messina and Reggio Calabria, Italy | |

| Interventions | Exp: Fat graft Ctl: Nil |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon's assessment of clinical score Radiological score |

|

| Notes | 1 yr | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Geisler 1999.

| Methods | Closed envelope randomization Blinding: single + assessor Lost to follow‐up: Europe ‐ 29/298 US ‐ 45/268 | |

| Participants | European study ‐ 298 pts; 167 m,102 f

followed‐up; mean age 38 yrs

Multicentre, Europe (9 centres) 268 pts; m:f not specified Multicentre, US (16 centres) |

|

| Interventions | Exp: ADCON‐L anti‐adhesion barrier gel Ctl: nil | |

| Outcomes | Patient rating, MRI scar score ‐ at 6 mths |

|

| Notes | US arm of Adcon‐L study Figures submitted to FDA by manufacturer falsified. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Greenfield 2003.

| Methods | Closed opaque envelope randomization Blinding: nil Lost to follow‐up: 0/88 | |

| Participants | 88 pts; 50 m, 38 f; Bristol, UK Small or moderate lumbar disc herniation | |

| Interventions | Exp: Microdiscectomy Ctl: Physiotherapy exercises |

|

| Outcomes | VAS

ODI

Work loss ‐ at 2 yrs |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Haines 2002.

| Methods | Randomization not stated Lost to follow‐up: 8/35 at 6 mos. |

|

| Participants | 35 pts; 19 m,16 f; Multicentre, US (8 centres) | |

| Interventions | Exp: Automated percutaneous discectomy Ctl: Conventional discectomy |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating

SF‐36

Roland score ‐ at 1 yr |

|

| Notes | 37 patients recruited out of 5735 screened and 95 eligible | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hedtmann 1992.

| Methods | Randomization by drawn cards Blinding: nil Lost to follow‐up: 16/100 at 5 yrs | |

| Participants | 100 pts; 65 m, 35 f; Bochum, Germany Contained disc at 1 level Failed conservative treatment (min 6 wks) | |

| Interventions | Exp: collagenase 400 ABC units Ctl: chymopapain (4000 units) |

|

| Outcomes | Surgeon rating ‐ 1 yr, 5 yrs 2nd treatment required ‐ 3 yrs, 5 yrs | |

| Notes | 5 year results included in separate publication (Wittenberg et al 1996) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Henriksen 1996.

| Methods | Closed envelope randomization Blinding: single No losses to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 79 pts; age 30‐48 yrs Copenhagen, Denmark Single level nerve root compromise | |

| Interventions | Exp: microsurgical discectomy Ctl: standard lumbar discectomy |

|

| Outcomes | Back pain score, leg pain score, time to discharge ‐ at 6 wks |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hermantin 1999.

| Methods | Closed envelope randomization Blinding: nil Lost to follow‐up: 0/60 | |

| Participants | 60 pts; age 15‐67 yrs Philadelphia, PN Single intracanal herniation <50% AP canal diameter | |

| Interventions | Exp: Arthroscopic microdiscectomy Ctl: Laminotomy and discectomy |

|

| Outcomes | Days to return to normal activity

Mean pain score

Patient rating ‐ at 2 yrs |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||