Abstract

Background

Colloids are widely used in the replacement of fluid volume. However, doubts remain as to which colloid is best. Different colloids vary in their molecular weight and therefore in the length of time they remain in the circulatory system. Because of this, and their other characteristics, they may differ in their safety and efficacy.

Objectives

To compare the effects of different colloid solutions in patients thought to need volume replacement.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Injuries Specialised Register (searched 1 December 2011), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 2011, issue 4 (The Cochrane Library); MEDLINE (Ovid) (1948 to November Week 3 2011); EMBASE (Ovid) (1974 to 2011 Week 47); ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (1970 to 1 December 2011); ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (1990 to 1 December 2011); CINAHL (EBSCO) (1982 to 1 December 2011); National Research Register (2007, Issue 1) and PubMed (searched 1 December 2011). Bibliographies of trials retrieved were searched, and for the initial version of the review drug companies manufacturing colloids were contacted for information (1999).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing colloid solutions in critically ill and surgical patients thought to need volume replacement.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted the data and assessed the quality of the trials. The outcomes sought were death, amount of whole blood transfused, and incidence of adverse reactions.

Main results

Eighty‐six trials, with a total of 5,484 participants, met the inclusion criteria. Quality of allocation concealment was judged to be adequate in 33 trials and poor or uncertain in the rest.

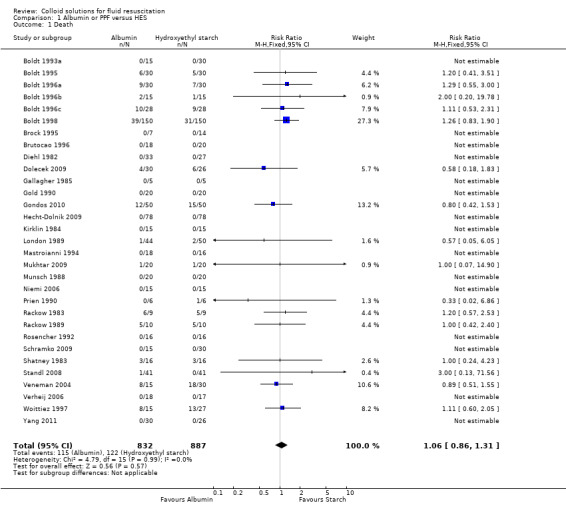

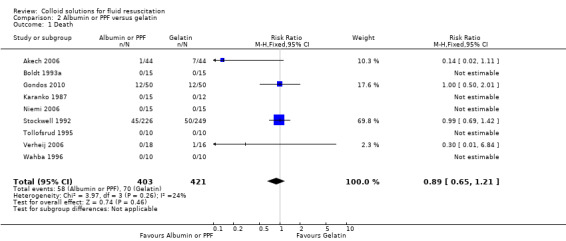

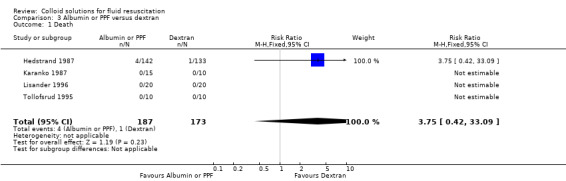

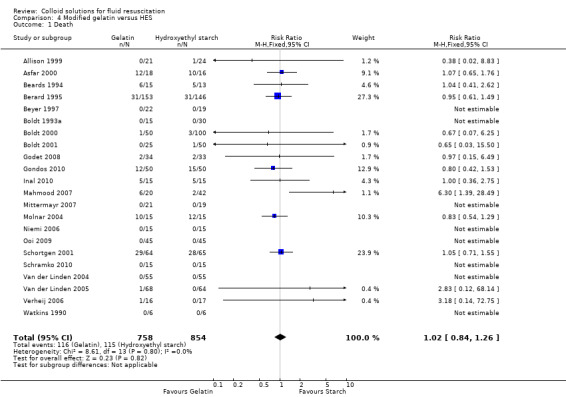

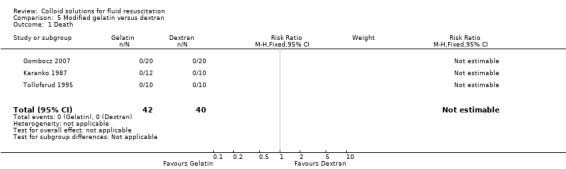

Deaths were reported in 57 trials. For albumin or plasma protein fraction (PPF) versus hydroxyethyl starch (HES) 31 trials (n = 1719) reported mortality. The pooled relative risk (RR) was 1.06 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 1.31). When the trials by Boldt were removed from the analysis the pooled RR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.20). For albumin or PPF versus gelatin, nine trials (n = 824) reported mortality. The RR was 0.89 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.21). Removing the study by Boldt from the analysis did not change the RR or CIs. For albumin or PPF versus dextran four trials (n = 360) reported mortality. The RR was 3.75 (95% CI 0.42 to 33.09). For gelatin versus HES 22 trials (n = 1612) reported mortality and the RR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.26). When the trials by Boldt were removed from the analysis the pooled RR was 1.03 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.27). RR was not estimable in the gelatin versus dextran and HES versus dextran groups.

Forty‐one trials recorded the amount of blood transfused; however, quantitative analysis was not possible due to skewness and variable reporting. Twenty‐four trials recorded adverse reactions, with two studies reporting possible adverse reactions to gel and one to HES.

Authors' conclusions

From this review, there is no evidence that one colloid solution is more effective or safe than any other, although the CIs were wide and do not exclude clinically significant differences between colloids. Larger trials of fluid therapy are needed if clinically significant differences in mortality are to be detected or excluded.

Keywords: Humans; Blood Proteins; Blood Proteins/therapeutic use; Colloids; Colloids/therapeutic use; Dextrans; Dextrans/therapeutic use; Fluid Therapy; Fluid Therapy/methods; Fluid Therapy/mortality; Hydroxyethyl Starch Derivatives; Hydroxyethyl Starch Derivatives/therapeutic use; Plasma Substitutes; Plasma Substitutes/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Rehydration Solutions; Rehydration Solutions/therapeutic use; Resuscitation; Resuscitation/methods; Resuscitation/mortality; Serum Albumin; Serum Albumin/therapeutic use; Serum Albumin, Human; Serum Globulins; Serum Globulins/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Are particular types of colloid solution safer for replacing blood fluids than others?

When a person is bleeding heavily, the loss of fluid volume in their veins can lead to shock, so they need fluid resuscitation. Colloids and crystalloids are two types of solutions used to replace lost blood fluid (plasma). They include blood and synthetic products. Both colloids and crystalloids appear to be similarly effective at resuscitation. There are different types of colloids and these may have different effects. However, the review of trials found there is not enough evidence to be sure that any particular colloid is safer than any other.

Background

Colloids are used as plasma substitutes for short‐term replacement of fluid volume while the cause of the problem is being addressed (e.g. stopping bleeding). These solutions can be blood products (human albumin solution, plasma protein fraction (PPF)) or synthetic products (modified gelatins, dextrans, etherified starches). Colloid solutions are widely used in fluid resuscitation (Yim 1995) and they have been recommended in a number of resuscitation guidelines and intensive care management algorithms (Armstrong 1994; Vermeulen 1995). Previous systematic reviews have suggested that colloids are no more effective than crystalloids in reducing mortality (Perel 2012; Roberts 2011). Despite this, colloid solutions are still widely used as they are thought to remain in the intravascular space for longer than crystalloids and, therefore, be more effective in maintaining osmotic pressure.

It is plausible that colloids may vary in their safety and effectiveness. Different colloids vary in the length of time they remain in the circulatory system. It may be that some low‐to‐medium molecular weight colloids (e.g. gelatins and albumin) are more likely to leak into the interstitial space (Traylor 1996), whereas some larger molecular weight hydroxyethyl starches (HES) are retained for longer (Boldt 1996). In addition it is thought that some colloids may affect coagulation or cause other adverse effects.

This review examines direct comparisons of the different colloid solutions in randomised trials to complement the earlier reviews on colloids compared to crystalloids (Perel 2012) and human albumin (Roberts 2011).

Objectives

To quantify the relative effects on mortality of different colloid solutions in critically ill and surgical patients requiring volume replacement, by examining direct comparisons of colloid solutions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Patients clinically assessed as requiring volume replacement or maintenance of colloid osmotic pressure.

Administration of fluid for preoperative haemodilution or volume loading, during plasma exchange, for priming extracorporeal circuits or following paracentesis are excluded.

Types of interventions

The colloid solutions considered are human albumin solutions, PPF, modified gelatins, dextran 70, or etherified starch solutions.

Trials of other blood products not used primarily for volume replacement (e.g. fresh frozen plasma (FFP), pooled serum) were excluded.

The review compares the administration of any regimens of different classes of colloids with each other.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was mortality from any cause at the end of the study period.

We also attempted to find data on incidence of adverse reactions, allergies or anaphylactic shock, and the amount of blood (whole blood or red blood cells) transfused in each group. Some of the synthetic colloids may have anticoagulant properties and, therefore, we felt that some measure of blood loss or haemorrhage was important. However, as blood loss is vulnerable to measurement error, we decided to use the amount of blood products transfused as an outcome measure.

Intermediate physiological outcomes were not used for several reasons. These were that they are subject to intra‐ and inter‐observer variation, they have no face value to patients and relatives, and the ones seen as appropriate are not stable over time. Also there would need to exist a strong predictive relationship between the variable and mortality.

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not limit the search for trials by language, date, or publication status.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

Cochrane Injuries Specialised Register (searched 1 Dec 2011);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2011, issue 4, The Cochrane Library);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1948 to November Week 3 2011);

EMBASE (Ovid) (1974 to 2011 Week 47);

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (1970 to 1 December 2011);

ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (1990 to 1 December 2011);

CINAHL (EBSCO) (1982 to 1 December 2011);

PubMed (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/) (searched 1 December 2011 limit‐Humans, published in the last 90 days);

National Research Register (issue 1, 2007);

Zetoc (searched 23 March 2007).

Full search strategies are listed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the bibliographies of the retrieved trials and contacted drug companies manufacturing colloids for information. For the original version of the review in 1999 we also identified trials by using the searches undertaken for the pre‐existing review of colloids versus crystalloids (Perel 2012), which included BIDS Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings, drawing on the handsearching of 29 international journals and the proceedings of several international meetings on fluid resuscitation, and checking the reference lists of the trials found. There were no language restrictions in any of the searches.

To identify unpublished trials we searched the register of the Medical Editors' Trial Amnesty and we contacted the UK Medicines Control Agency.

For the first version of the review (published 1999) we also contacted the medical directors of the following companies, which all manufacture colloids:

Alpha Therapeutic UK Limited (Albutein),

American Critical Care McGraw (Hespan),

Bayer (Plasbumin),

Baxter (Gentran),

Bio Products Laboratory (Zenalb),

Cambridge Laboratories (Rheomacrodex),

Centeon Ltd (Albuminar),

CIS UK Ltd,

CP (Lomodex),

Common Services Agency,

Consolidated (Gelofusine),

DuPont (Hespan),

Fresenius (eloHAES and HAES‐Steril),

Geistlich Sons Ltd (Hespan and Pentaspan),

Hoechst (Haemaccel),

Mallinckrodt Medical GMBH (Infoson),

Nycomed, Oxford Nutrition (Elohes),

Pharmacia and Upjohn Ltd (Rheomacrodex),

Sorin Biomedica Diagnostics Spa.

Data collection and analysis

The Injuries Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator ran the electronic database searches, collated the results, and removed duplicates before sending them to the review authors for screening.

Selection of studies

One review author examined the search results for reports of possibly relevant trials and these reports were then retrieved in full. Two review authors applied the selection criteria independently to the trial reports, resolving disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted information on the following:

method of allocation concealment,

number of randomised patients,

type of participants,

the interventions,

outcome data (numbers of deaths, volume of blood transfused, and incidence of adverse or allergic reactions).

The review authors were not blinded to the trial authors or journal when doing this, as the value of this has not been established (Berlin 1997). Results were compared and any differences resolved by discussion. Where there was insufficient information in the published report, we attempted to contact the trial authors for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Since there is evidence that the quality of allocation concealment particularly affects the results of studies (Higgins 2011), two review authors scored this quality on the scale used by Higgins 2011 as shown below, assigning 'high risk of bias' to poorest quality and 'low risk of bias' to best quality:

low risk of bias = trials deemed to have taken adequate measures to conceal allocation (i.e. central randomisation; numbered or coded bottles or containers; drugs prepared by the pharmacy; serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes; or other description that contained elements convincing of concealment);

unclear risk of bias = trials in which the authors either did not report an allocation concealment approach at all or reported an approach that did not fall into one of the other categories;

high risk of bias = trials in which concealment was inadequate (such as alternation or reference to case record numbers or to dates of birth).

Where the method used to conceal allocation was not clearly reported, the trial author was contacted, if possible, for clarification. We then compared the scores allocated and resolved differences by discussion.

Data synthesis

The following comparisons were made:

albumin or PPF versus etherified starch,

albumin or PPF versus modified gelatin,

albumin or PPF versus dextran 70,

modified gelatin versus etherified starch,

modified gelatin versus dextran 70,

etherified starch versus dextran 70.

For each trial we calculated the risk ratio (RR) of death and 95% confidence interval (CI), such that a RR of more than 1 indicates a higher risk of death in the first group named.

We examined the groups of trials for statistical evidence of heterogeneity using Chi2 and I2 tests. If there was no obvious heterogeneity on visual inspection or statistical testing, we calculated pooled RRs and 95% CIs using a fixed‐effects model.

We assessed the skewness of continuous data by checking the mean and standard deviation (if available). If the standard deviation is more than twice the mean for data with a finite end point (such as 0 in the case of bleeding), the data are likely to be skewed and it is inappropriate to apply parametric tests (Altman 1996). This is because the mean is unlikely to be a good measure of central tendency. If parametric tests could not be applied, we tabulated the data.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined the effect of excluding trials judged to have inadequate (scoring 'high risk of bias') allocation concealment in a sensitivity analysis.

The editorial group is aware that a clinical trial by Professor Joachim Boldt has been found to have been fabricated (Boldt 2009). As the editors who revealed this fabrication pointed out (Reinhart 2011; Shafer 2011), this casts some doubt on the veracity of other studies by the same author. All Cochrane Injuries Group reviews that include studies by this author have therefore been edited to show the results with this author's trials included and excluded. Readers can now judge the potential impact of trials by this author on the conclusions of the review.

Results

Description of studies

For more detailed descriptions of individual studies, see 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Eighty‐six studies met the inclusion criteria, with a total of 5488 participants. The earliest trial was from 1980 and the most recent from 2011. From the drug companies that we contacted in 1999, we were sent information by Baxter Healthcare Ltd, CIS UK Ltd, Fresenius Ltd, Hoechst and Pharmacia. No new trials were identified from the information sent to us.

The trials included the following comparisons.

Albumin or PPF versus starch (50 trials with 2458 participants in these groups)

Arellano 2005; Boldt 1986; Boldt 1993a; Boldt 1995; Boldt 1996a; Boldt 1996b; Boldt 1996c; Boldt 1998; Brock 1995; Brutocao 1996; Claes 1992; Diehl 1982; Dolecek 2009; Falk 1988; Friedman 2008; Fulachier 1994; Gahr 1981; Gallagher 1985; Gold 1990; Gondos 2010; Haas 2007; Hausdorfer 1986; Hecht‐Dolnik 2009; Hiippala 1995; Huskisson 1993; Jones 2004; Kirklin 1984; London 1989; Mastroianni 1994; Moggio 1983; Mukhtar 2009; Munoz 1980; Munsch 1988; Niemi 2006; Prien 1990; Rackow 1983; Rackow 1989; Reine 2008; Rosencher 1992; Schramko 2009; Shatney 1983; Standl 2008; Veneman 2004; Verheij 2006; Vogt 1994; Vogt 1996; Vogt 1999; von Sommoggy 1990; Woittiez 1997; Yang 2011.

Albumin or PPF versus dextran (six trials with 410 participants in these groups)

Hedstrand 1987; Hiippala 1995; Jones 2004; Karanko 1987; Lisander 1996; Tollofsrud 1995.

Albumin or PPF versus gelatin (14 trials with 1152 participants in these groups)

Boldt 1986; Du Gres 1989; Evans 2003; Gondos 2010; Haas 2007; Huang 2005; Huskisson 1993; Karanko 1987; Niemi 2006; Stockwell 1992; Stoddart 1996; Tollofsrud 1995; Verheij 2006; Wahba 1996.

Starch versus gelatin (26 trials with 1883 participants in these groups)

Allison 1999; Asfar 2000; Beards 1994; Berard 1995; Beyer 1997; Boldt 1986; Boldt 2000; Boldt 2001; Carli 2000; Dytkowska 1998; Godet 2008; Gondos 2010; Haas 2007; Huskisson 1993; Inal 2010; Jin 2010; Mahmood 2007; Molnar 2004; Niemi 2006, Ooi 2009; Rittoo 2004; Schortgen 2001; Schramko 2010; Van der Linden 2004; Van der Linden 2005; Volta 2007.

Starch versus dextran (one trial with 30 participants in these groups)

Dextran versus gelatin (three trials with 82 participants in these groups)

Gombocz 2007; Karanko 1987; Tollofsrud 1995.

The trials involved patients with hypovolaemia, sepsis, trauma, and patients who had undergone surgery.

The trials tended to report surrogate outcomes such as haemodynamic variables. Data on death were obtainable from 57 trials. Information on the amount of blood or FFP transfused was available in 41 trials. However, the data were reported in a variety of different ways that made combining the data in a meta‐analysis unfeasible.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria varied, but many of the studies excluded patients with previous adverse reactions to colloids, clotting problems, or renal disease.

Risk of bias in included studies

Using the criteria defined in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) the quality of allocation concealment was judged to be adequate (at low risk of bias) in 33 trials, unclear in 42 trials, and inadequate (at high risk of bias) in 10 trials. Where the method of allocation concealment was unclear, we attempted to contact all of the trialists and we obtained information from 16 of them. However, due to the lack of reported information on the process of randomisation and allocation concealment, we were unable to assess the quality in many of the trials properly.

Thirteen trials mentioned that some form of blinding was used. In nine, some, or all, of the staff giving treatment were blinded, in six those giving postoperative care were blinded, in two the outcome assessors were blinded, and in one the statisticians performing the analysis were blinded to treatment group.

Effects of interventions

Mortality

Of the 86 trials identified, 41 reported mortality data. Information on death was obtained from a further 16 trials by contact with the trial authors. We, therefore, had data on death from 57 trials.

Albumin or PPF versus HES

Thirty‐one trials (1719 participants) reported mortality data. The pooled RR was 1.06 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.31). When the trials by Boldt (Boldt 1993a; Boldt 1995; Boldt 1996a; Boldt 1996b; Boldt 1996c; Boldt 1998; Boldt 2006a) were removed from the analysis the pooled RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.35).

Albumin or PPF versus gelatin

Nine trials (824 participants) reported mortality but only three of those trials had any deaths. The RR was 0.89 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.21). The Boldt trial included in this analysis had no events (Boldt 1993a), and therefore contributed no data to the analysis.

Albumin or PPF versus dextran

Four trials (360 participants) reported mortality and were included in the meta‐analysis. Only one of these reported any deaths (Hedstrand 1987). The RR was 3.75 (95% CI 0.42 to 33.09).

Gelatin versus HES

Twenty‐two studies (1612 participants) reported mortality and the pooled RR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.26). The effect was unchanged with removal of the six trials by Boldt (Boldt 1993a; Boldt 2000; Boldt 2001; Haisch 2001c; Haisch 2001c; Huttner 2000a) (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.25).

Gelatin versus dextran 70

There were three trials (82 participants) that reported mortality. There were no deaths so the RR was not estimable.

HES versus dextran 70

No trials reported mortality.

Amount of blood transfused

Forty‐five trials recorded the amount of blood or FFP transfused. As the data were reported in various ways, often lacking a measure of variation, and was also skewed we did not attempt a quantitative synthesis. These data can be seen in the 'other data' tables.

Adverse events

Twenty‐four trials reported the incidence of adverse or allergic reactions or anaphylactic shock. The majority reported that there were no such incidents. However, one study (Akech 2006) reported a possible adverse reaction to gelatin (Gelufusine) and one (Godet 2008) reported two possible adverse reactions in the HES group and one in the gelatin group.

Sensitivity analysis

The effect of excluding trials judged to have inadequate or unclear allocation concealment was examined in a subgroup analysis. This made no significant difference to the results (albumin or PPF versus HES: pooled RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.86 to 1.36; albumin or PPF versus gelatin pooled RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.47 to 1.81; gelatin versus HES pooled RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.44).

There was also no significant difference when the trials by Boldt were removed from the analysis (albumin or PPF versus HES pooled RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.20), albumin or PPF vs gelatin 0.92 (0.47, 1.81), gelatin versus HES 1.03 (0.84, 1.27).

Removing both the trials with inadequate allocation concealment and the trials by Boldt from the albumin or PPF versus HES analysis gave a pooled effect of RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.24). The RR for gelatin versus HES was 1.12 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.47).

Discussion

Despite finding 90 trials we cannot make any conclusions about the relative effectiveness of different colloid solutions. Previous systematic reviews have suggested that colloids are no more effective than crystalloids in reducing mortality (Perel 2012; Roberts 2011), but there are too few data available to show in direct comparisons whether any of the colloids are safer or more effective than another. The CIs are wide and do not exclude clinically significant differences between colloids.

Mortality was selected as the main outcome measure in this systematic review for several reasons. In the context of critical illness, death or survival is a clinically relevant outcome that is of immediate importance to patients, and data on death are reported in many of the studies. Furthermore, one might expect that mortality data would be less prone to measurement error or biased reporting than would data on pathophysiological outcomes. The use of a pathophysiological end point as a surrogate for an adverse outcome assumes a direct relationship between the two, an assumption that may sometimes be inappropriate. Finally, when trials collect data on a number of physiological end points, there is the potential for bias due to the selective publication of end points showing striking treatment effects.

There was wide variation in the participants, intervention regimens, and the length of follow‐up. The length of follow‐up was not reported in many of the studies. Where it is reported it ranges from a matter of hours to months, which may explain a high proportion of the heterogeneity in overall event rates. The effect of these factors was not examined in a sensitivity analysis, as there was felt to be insufficient data to justify examining subgroups.

Many of the trials were small, and some had been done some time ago. Although older trials will not necessarily be of poorer quality, it may be that treatment protocols have subsequently altered making these trials less relevant to current clinical practice.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Previous reviews have not shown a benefit of colloids over crystalloids for volume replacement (Perel 2012; Roberts 2011).

This review does not provide any evidence that one colloid is safer than another, but does not rule out clinically significant differences.

Implications for research.

Trials of fluid therapy need to be larger in order to exclude clinically significant differences between colloids in patient relevant outcomes. However, trials should probably first address the question of whether colloids are any more effective than crystalloid solutions.

Use of surrogate outcomes, such as physiological measurements, should be discouraged unless there is a strong relationship with outcomes of interest to patients and relatives.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 October 2012 | Amended | Minor copy edits made to analysis labels |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 June 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Due to the retraction of four studies (Boldt 2006; Haisch 2001a; Haisch 2001b; Huttner 2000), the review has been amended. The retracted studies, and their associated data, are now excluded from the review. The conclusions of the review have not changed. |

| 1 May 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The review has been updated to December 2011. Twenty additional studies have been included (Akech 2006;Dolecek 2009; Friedman 2008; Godet 2008; Gombocz 2007; Gondos 2010; Haas 2007; Hecht‐Dolnik 2009; Inal 2010; Jin 2010; Mahmood 2007; Mittermayr 2007; Mukhtar 2009; Ooi 2009; Reine 2008; Schramko 2009; Schramko 2010; Standl 2008; Volta 2007; Yang 2011). The conclusions of the review have not changed. |

| 30 April 2012 | New search has been performed | The review has been updated to December 2011. |

| 10 February 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The editorial group is aware that a clinical trial by Prof. Joachim Boldt has been found to have been fabricated (Boldt 2009). As the editors who revealed this fabrication point out (Reinhart 2011; Shafer 2011), this casts some doubt on the veracity of other studies by the same author. All Cochrane Injuries Group reviews which include studies by this author have therefore been edited to show the results with this author's trials included and excluded. Readers can now judge the potential impact of trials by this author (Boldt 1986, Boldt 1993a, Boldt 1995, Boldt 1996a, Boldt 1996b, Boldt 1996c, Boldt 1998, Boldt 2000, Boldt 2001, Boldt 2006a, Haisch 2001c, Haisch 2001c, Huttner 2000a) on the conclusions of the review. |

| 11 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 2 October 2007 | New search has been performed | The search for the review was updated in March 2007 and thirteen new studies were added to the review. |

Notes

The editorial group is aware that a clinical trial by Professor Joachim Boldt has been found to have been fabricated (Boldt 2009). As the editors who revealed this fabrication point out (Reinhart 2011; Shafer 2011), this casts some doubt on the veracity of other studies by the same author. All Cochrane Injuries Group reviews which include studies by this author have therefore been edited to show the results with this author's trials included and excluded. Readers can now judge the potential impact of trials by this author (Boldt 1986; Boldt 1993a;Boldt 1995;Boldt 1996a;Boldt 1996b;Boldt 1996c;Boldt 1998;Boldt 2000;Boldt 2001; Boldt 2006a Haisch 2001c Haisch 2001c Huttner 2000a) on the conclusions of the review.

Emma Sydenham, Managing Editor, performed the sensitivity analysis in 2011. The authors agreed with the changes to the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Phil Alderson, Victoria Hawkins and Syed Ashraf who were authors of earlier versions of this review. In addition, we acknowledge the help of Ralph Bloch, Olivier Duperrex, Andrew Smith, Peter Smith, and Reinhard Wentz, who assisted with translating articles. Also many thanks to the authors who provided us with details of their studies.

We are grateful to the drug companies, Baxter Healthcare Ltd, CIS Ltd, Fresenius Ltd, Hoechst, and Pharmacia who responded to our request for information.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| Cochrane Injuries Specialised Register (searched: 1 December 2011) 1. (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*) 2. (fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) and (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*) 3. 1 and 2 |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials 2011, issue 4 (The Cochrane Library) #1 MeSH descriptor Colloids explode all trees in MeSH products #2 MeSH descriptor Plasma explode all trees in MeSH products #3 MeSH descriptor Albumins explode all trees in MeSH products #4 (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*) #5 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4) #6 MeSH descriptor Fluid Therapy explode all trees in MeSH products #7 MeSH descriptor Plasma Volume explode all trees #8 (fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) near1 (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*) #9 (#6 OR #7 OR #8) #10 (#5 AND #9) #11 (#10), from 2007 to 2011 |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) (1948 to November Week 3 2011) 1. exp Albumins/ 2. exp plasma/ 3. exp colloids/ 4. (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*).ti,ab. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. Exp Plasma volume/ 7. Exp Fluid Therapy/ 8. ((fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) adj1 (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*)).ab,ti. 9. 6 or 7 or 8 10. 5 and 9 |

| EMBASE (Ovid) (1974 to 2011 Week 47) 1. exp ALBUMIN/ 2. exp HYDROCOLLOID/ 3. exp PLASMA/ 4. (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*).ti,ab. 5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6. exp Fluid Therapy/ 7. exp Plasma volume/ 8. ((fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) adj1 (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*)).ab,ti. 9. 6 or 7 or 8 10. 5 and 9 11. exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 12. exp controlled clinical trial/ 13. randomi?ed.ab,ti. 14. placebo.ab. 15. *Clinical Trial/ 16. randomly.ab. 17. trial.ti. 18. 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19. exp animal/ not (exp human/ and exp animal/) 20. 18 not 19 21. 10 and 20 22. (2007* or 2008* or 2009* or 2010* or 2011*).em. 23. 21 and 22 |

| ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (1970 to 1 December 2011), ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (1990 to 1 December 2011) #1 Topic=((colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*)) AND Topic=((fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) NEAR/1 (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*)) #2 TS=((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) NEAR/1 (blind* OR mask*)) OR TS=((clinical OR control* OR placebo OR random*) NEAR/1 (trial* or group* or study or studies or placebo or controlled)) NOT TI=(Animal* or rat or rats or rodent* or mouse or mice or murine or dog or dogs or canine* or cat or cats or feline* or rabbit or rabbits or pig or pigs or porcine or swine or sheep or ovine* or guinea pig*) #3 #1 and #2 |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) (1982 to 2011) S1. (fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) N3 (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*) S2. colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid* S3. S1 and S2 (limit to Publication Type: Randomized Controlled Trial) |

| PubMed [www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez/] (searched 1 December 2011: Limit‐Humans, published in the last 90 days) #1((randomized controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt]) OR (randomized OR randomised OR randomly OR placebo[tiab]) OR (trial[ti]) OR ("Clinical Trials as Topic"[MeSH Major Topic])) NOT (("Animals"[Mesh]) NOT ("Humans"[Mesh] AND "Animals"[Mesh])) #2 (fluid* or volume or plasma or rehydrat* or blood or oral) and (replac* or therapy or substitut* or restor* or resuscitat* or rehydrat*) #3 (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*) #4 (("Albumins"[Mesh]) OR "Colloids"[Mesh]) OR "Plasma"[Mesh] #5 #3 or #4 #6 #1 and #2 and #5 |

| NRR up to issue 1, 2007 #1 (colloid* or albumin* or albumen* or plasma* or starch* or dextran* or gelofus* or hemacc* or haemacc* or hydrocolloid*) #2 ((plasma* or fluid* or volum*) and (therap* or restor* or resuscita* or substitut* or replac*)) #3 #1 and #2 |

| ZETOC searched on 23 March, 2007 Colloid* fluid* resusc* |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Albumin or PPF versus HES.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 31 | 1719 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.86, 1.31] |

| 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albumin or PPF versus HES, Outcome 1 Death.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Albumin or PPF versus HES, Outcome 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | |

| Arellano 2005 | HA group received median of 1 unit each; HES median of 3 units each | |

| Boldt 1998 | Total units of red blood cells transfused given for each group (Hetastarch 356, albumin 371). No means, medians, or measures of variation given | |

| Brock 1995 | The amount of blood derivatives ('blutderivate') was given in millilitres as a mean and standard deviation (SD). In the 10% starch group the mean was 379 (SD 483), in the 6% starch group the mean was 243 (SD 192) and in the 5% albumin group the mean was 171 (SD 236) | |

| Brutocao 1996 | Packed red cell transfusion is given in mL/kg. In the HES group the mean was 0.3, the SD 1.3, and the range of 0 to 6.4. In the albumin group the mean was 1.1, the SD 3.7, and the range 0 to 13.1 | |

| Claes 1992 | Blood transfused was not recorded. Authors state "none of the patients lost an abnormally large quantity of blood or experienced a clinically perceptible coagulation disorder" | |

| Diehl 1982 | 18% (n = 5) of the albumin group and 15% (n = 5) of the HES group received banked blood during their stay. Blood transfused was recorded as mean number of units per person. In the albumin group this was 0.37 units per person and in the HES group this was 0.36 units per person | |

| Falk 1988 | Packed red blood cells transfused at 24 hours was given in millilitres. The albumin group received a mean of 375 with a standard error of the mean (SEM) of 244 and the HES group received a mean of 700 with an SEM 228 | |

| Gallagher 1985 | Amount of blood products transfused postoperatively was given as a mean in millilitres with the SEM. For the albumin group the mean was 560 (SEM 149.2) and for the starch group the mean was 566 (SEM 72.6) | |

| Gold 1990 | Packed red blood cells is given in units. The albumin group received a mean of 2.05 and the HES group received a mean of 2.50 | |

| Hecht‐Dolnik 2009 | Data given as mean number of units (SD) RBC: HES 1.13 (2.52), HA 0.40 (0.89), P = 0.0002 Platelets: HES 0.35 (0.77), HA 0.13 (0.38), P = 0.0001 FFB: HES 0.56 (1.24), HA 0.15 (0.56), P value not significant |

|

| Hiippala 1995 | Amount of red cell concentrates transfused was given as a mean and SD of millilitres per kilogram body weight (mL/kgBW). For albumin the mean was 20 (SD 14), for 4% HES the mean was 20 (SD 14) and for 6% HES the mean was 25 (SD 17) | |

| Jones 2004 | HA group received mean of 0.5 units (range 0 units to 1 unit), HEs group received mean of 1 unit (range of 0 units to 2 units) | |

| Kirklin 1984 | The amount of red cells given up to the first 24 hours postoperatively was recorded. In the HES group the mean was 430 with a standard error of 90, and in the albumin group the mean is 440 with a standard error of 76 | |

| London 1989 | Total postoperative blood transfused is given in millilitres. In the albumin group the figures are given as 838 mL (630 mL) and the HES group 894 mL (600 mL). It does not report what the figures represent (they may be mean and SD). Intraoperatively the blood given in the albumin group was 400 mL (346 mL) and in the HES group 336 mL (400 mL) | |

| Mastroianni 1994 | The mean of packed red cells given was recorded in millilitres. For pentastarch the mean was 167 and for albumin it was 234. Another figure was given 163 for pentastarch and 148 for albumin but it was not clear what this represented | |

| Mukhtar 2009 | Reported as units of PRBCs, mean and range. Intraoperatively HA 4 (0 to 6), HES 4 (0 to 10), postoperatively HA 4 (0 to 8), HES 2 (0 to 8) | |

| Munsch 1988 | The amount of whole blood transfused was given as a median volume. For the albumin group it was 830 mL (range 260 mL to 1800 mL), and for the HES group it was 830 mL (range 50 mL to 1840 mL) | |

| Niemi 2006 | The mean and SD of number of RBC units transfused was given. HA mean 0.2 (SD 0.6), HES mean 0.3 (SD 0.6) | |

| Prien 1990 | The mean and SEM for the amount of packed red cells given was recorded. For the albumin group the mean was 1.2 (SEM 0.7). In the HES group the mean was 1.8 (SEM 0.7) | |

| Rackow 1983 | Total amount of blood transfused was given in millilitres at the end of the maintenance period. For the albumin group the mean was 363.9 (SEM 186) and for the starch group the mean was 757.1 (SEM 201) | |

| Rackow 1989 | No data on units transfused. The authors say "there was no evidence of clinical bleeding" | |

| Shatney 1983 | The amount of red blood cells transfused was given in a graphical form not figures | |

| Standl 2008 | Data given as mean number of units with SD RBC: HES 52.2 (139.2), 53.4 (155.9) FFP: HES 22.4 (117.9), HA 25.2 (90.7) No significant difference between groups |

|

| Vogt 1994 | Amount of EK given was recorded as a mean and SD of the millilitres given. For the albumin group it was 1138 (SD 763.5), and for the HES group it was 944.4 (SD 466.2) | |

| Vogt 1996 | The mean and SD of packed red blood cells transfused was given for the end of surgery and at 6 hours. For the albumin group at the end of surgery the mean was 798 (SD 1147) and at 6 hours it was 1333 (SD 1399). For the HES group at the end of surgery the mean was 763 (SD 923) and at 6 hours the mean was 1538 (SD 1074) | |

| Vogt 1999 | Amount of packed red blood cells was given as mean and SD. In the HES group the mean was 1510 mL (SD 765 mL) and in the albumin group the mean was 1410 mL (SD 946 mL) | |

| von Sommoggy 1990 | The trialists report 'no increased bleeding in the HES group' | |

Comparison 2. Albumin or PPF versus gelatin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 9 | 824 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.65, 1.21] |

| 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Albumin or PPF versus gelatin, Outcome 1 Death.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Albumin or PPF versus gelatin, Outcome 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | ||||

| Evans 2003 | No data on amount of units transfused. Author reports that there was no significant difference in the median total blood loss between the groups (P = 0.5587) | ||||

| Niemi 2006 | The mean and standard deviation (SD) of RBC units transfused was given. HA mean 0.2 (SD 0.6), Gel mean 0.2 (SD 0.4) | ||||

| Stockwell 1992 | The volume of blood products given was recorded as a mean with the range also given. In the albumin group the mean was 1.45 L (range 0‐29) and in the haemacell group the mean was 1.39 L (range 0 L to 66 L) (P = 0.65, Mann‐Whitney U test) | ||||

| Tollofsrud 1995 | The amount of erthrocytes given was recorded as a mean and SD. In the albumin group the mean was 240 (SD 310), and in the polygeline group the mean was 490 (SD 548) | ||||

Comparison 3. Albumin or PPF versus dextran.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 4 | 360 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.75 [0.42, 33.09] |

| 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albumin or PPF versus dextran, Outcome 1 Death.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Albumin or PPF versus dextran, Outcome 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | ||||

| Hedstrand 1987 | The perioperative and postoperative amount of red blood cells transfused was reported as a mean and standard deviation (SD) of units given. For the plasma group the mean was 5.2 (SD 4.8) and for the dextran group the mean was 5.8 (SD 4.4) | ||||

| Hiippala 1995 | Amount of red cell concentrates transfused was given as a mean and SD of millilitre per kilo gram body weight (mL/kgBW). For albumin the mean was 20 (SD 14) and for dextran the mean was 19 (SD 12) | ||||

| Jones 2004 | Mean of 0.5 unit HA (range 0 to 1), mean of 1 for DEX (range 0 to 2) | ||||

| Lisander 1996 | Total red blood cells transfused is given. For the albumin group the mean was 2.3 (SD1.6), in the dextran group the mean was 3.8 (SD 2.4). Red cells autotransfused was also given as 312 (SD 184) in the albumin group and 383 (SD 259) in the dextran group | ||||

| Tollofsrud 1995 | Erythrocytes given was recorded as mean and SD. The mean for the albumin group was 240 (SD 310) and the mean for the dextran group was 390 (SD 417) | ||||

Comparison 4. Modified gelatin versus HES.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 22 | 1612 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.84, 1.26] |

| 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Modified gelatin versus HES, Outcome 1 Death.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Modified gelatin versus HES, Outcome 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | ||||

| Allison 1999 | The mean volume of packed red blood cells (PRBC) transfused was given for each day up to and including the 5th day. For the first postoperative day the hydroxyethyl starch (HES) group received a total of 3067 mL of PRBCs and the gelatine group received 2643 mL of PRBCs | ||||

| Berard 1995 | Blood transfused was given in units, 2.6 units for the gel group and 2.5 units for the HES group (presumably this figure is mean) | ||||

| Beyer 1997 | Blood transfused is given in graphical form and not figures | ||||

| Boldt 2000 | The amount of PRBC transfused is given as the total number of units for each group

By the first post operative day the number of units of PRBCs transfused was: HES 70: 38 units, HES 200: 40 units, Gelatin: 44 units |

||||

| Boldt 2001 | The amount of PRBC transfused is given as the total number of units for each group By the first post operative day the number of units of PRBCs transfused was: HES 200: 18 units, HES 130: 16 units, Gelatin 18 units | ||||

| Carli 2000 | The amount of PRBC transfused is given as the total number of units for each group 1 unit of blood was given in the gel group and 0 units of blood were given in the starch group | ||||

| Mahmood 2007 | Amount of red cells and FFP is given as median number of units (range) Red cells: HES 200/0.62 = 7.0 (4.5 to 10), HES 130/0.4 = 6.0 (4.0 to 8.0), gelatin = 7.0 (5.25 to 9.75). P = 0.360 (no statistical difference between groups) FFP: HES 200/0.62 = 4 (0 to 6), HES 130/0.4 = 2 (0 to 5), gelatine = 4 (0 to 7). P = 0.420 (no statistical difference between groups) |

||||

| Mittermayr 2007 | Total red cells units transfused Gelatin n = 13, HES n = 9 Number of patients transfused Gelatin n = 8/21, HES n = 3/19 |

||||

| Niemi 2006 | The mean and SD of red blood cell (RBC) units transfused was given. Gel mean 0.2 (SD 0.4), HES 0.3 (0.6) |

||||

| Ooi 2009 | Data reported as number of patients who received at least 1 unit PRBCs: HES = 40, gelatin = 42. P = 0.46 FFP: HES = 17, gelatin = 24. P = 0.14 No statistical difference between groups |

||||

| Schramko 2009 | Data given as number of units of RBC and FFP transfused RBC: HES 200/0.5 = 11, HES 130/0.4 = 5, HA = 5 FFP: HES 200/0/5 = 1, HES 130/0.4 = 1, HA = 0 No significant difference between groups |

||||

| Schramko 2010 | Data given as number of units of RBC and FFP transfused HES group received 15 units of RBC and 2 units of FFP Gel group received 21 units of RBC and 2 units of FFP No significant difference between groups |

||||

| Van der Linden 2004 | HES group received total of 12 units of PRBC, GEL group received 3 units of PRBC | ||||

| Van der Linden 2005 | No of patients receiving allogenic blood in each group HES group n= 24, GEL n= 21 No of units of PRBC (median and range) HES 0 (range 0‐6), Gel 0 (range 0‐6) |

||||

Comparison 5. Modified gelatin versus dextran.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death | 3 | 82 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Modified gelatin versus dextran, Outcome 1 Death.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Modified gelatin versus dextran, Outcome 2 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | ||||

| Gombocz 2007 | Units of red blood cells transfused Dextran (group A): mean 1.8 (standard deviation (SD) 1.3) Oxypolygelatin (group B): mean 1.6 (SD 1.2) P = 0.548 |

||||

| Tollofsrud 1995 | Erythrocytes given was recorded as mean and SD Polygeline: mean 490 (SD 548) Dextran: 390 (SD 417) |

||||

Comparison 6. HES versus dextran.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | Other data | No numeric data |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 HES versus dextran, Outcome 1 Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data).

| Blood/red cells transfused (skewed or inadequate data) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Notes | ||||

| Hiippala 1995 | Amount of red cell concentrates transfused in millilitres/kilogram body weight (mL/kgBW) was given as a mean and standard deviation Dextran mean 19 (SD 12) 4% Starch mean 20 (SD 14) 6% Starch mean 25 (SD 17) |

||||

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Akech 2006.

| Methods | Randomised design. Fluid interventions allocated sequentially in blocks of 10 ITT analysis |

|

| Participants | 88 children over 3 months of age with severe malaria complicated by metabolic acidosis. Inclusion criteria: severe malaria, metabolic acidosis, and clinical feature of shock. Excluded if had pulmonary oedema, oedematous malnutrition, or papilloedema | |

| Interventions | 1) 4% Modified gelatin (n = 44) 2) 4.5% Albumin (n = 44) |

|

| Outcomes | Death Resolution of shock and acidosis Neurological sequelae at discharge Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Intervention arms not blinded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. Authors report that allocation of intervention was not concealed |

Allison 1999.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Randomisation was based on date of admission Analysis not ITT | |

| Participants | 45 patients with blunt trauma who required colloid infusion. Patients were excluded if they were less than 12 years old, did not require admission to the ITU, died within 24 hours, were pregnant or in renal failure 8 gelatin and 6 HES patients excluded after randomisation | |

| Interventions | 1) HES (200/0.45 Pentaspan) (n = 24) 2) Gelatin (Gelofusine) (n = 21) After 24 hours, colloid administration was at the discretion of the clinician | |

| Outcomes | Death Glasgow coma score Volumes of blood and platelets infused Haematological parameters | |

| Notes | Data were collected until the patient left the ITU or for a maximum of 5 days. Main outcome of interest was capillary leak | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. Randomisation was based on date of admission (on even dates patients received HES) |

Arellano 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. All participants, healthcare workers, and study personnel blinded to allocation | |

| Participants | 50 adults undergoing surgical ablation of oropharyngeal cancer with free flap reconstruction (mean age 55 years). Exclusion criteria ‐ ASA Physical Status Classification 3‐4, cardiac insufficiency, pancreatitis, severe hepatic dysfunction, renal dysfunction, anaemia, coagulation abnormalities, ingestion of NSAID, or ASA within 10 days of surgery and previous major head and neck surgery with free flap reconstruction | |

| Interventions | 1) 5% HA (n = 25) 2) HES 264/0.45 (n = 25) CVP was maintained between 7 mmHg and 10 mmHg | |

| Outcomes | Clinical indices of coagulation Number of units of blood transfused | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 24 hours. 1 patient in each group did not complete the study because planned surgical procedure was abandoned | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Study colloids placed in masked container by nurse not involved in other aspects of trial |

Asfar 2000.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 34 septic, hypovolaemic, ventilated, and haemodynamically controlled patients Inclusion criteria: patients aged over 16 years, systolic arterial pressure higher than 90 mmHg and hypovolaemia defined by PAOP of 12 mmHg or less Patients were excluded if they had an overt haemodynamic, ventilatory, or acid base status instability. Sepsis was identified by either positive bacterial blood cultures, bronchoalveolar lavage, or clinical evidence of infection | |

| Interventions | 1) 6% HES (n = 16) 2) 4% MFG (n = 18) | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 1 hour. 2 patients in the HES group were excluded because they experienced haemodynamic instability. The final analysis was made on remaining 16 patients. Information on allocation concealment obtained from study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Allocation using sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Beards 1994.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 28 patients with hypovolaemia, mechanically ventilated for concurrent acute respiratory failure. Patients fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: age >16 years, body weight between 50 kg and 85 kg, MAP < 80 mmHg (or 30 mmHg less than previously recorded); PAOP < 10 mmHg with oliguria (i.e. urine output < 15 mL/hour) | |

| Interventions | 1) Rapid infusion of 500 mL MFG (n = 15) 2) Rapid infusion of 500 mL hetastarch (n = 13) | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Oxygen variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 30 minutes for haemodynamic variables and until discharge for deaths. Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. Allocation by alternation |

Berard 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Blinding not mentioned | |

| Participants | 319 patients in a resuscitation service receiving medical (gastrointestinal haemorrhage) and surgical cases. Patients were excluded if they had had a prior allergic reaction | |

| Interventions | 1) Gelatin (n = 153) 2) HES (n = 146) The prescribers chose the quantity of colloid, guided by normal practice | |

| Outcomes | Death Amount of colloid and RBCs given Cost | |

| Notes | 20 patients lost to follow‐up, no explanation given. Follow‐up to discharge. Information on method of randomisation was obtained on contact with the study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. 'A set of 200 tickets (type 1) and another set of 200 tickets (type 2) were mixed in a box. One ticket was drawn at random for each patient' |

Beyer 1997.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. No blinding | |

| Participants | 48 patients undergoing major elective hip surgery with an expected blood loss of > 1000 mL. Exclusion criteria were Hb concentration 11 g/dL or less; heart failure and coronary artery disease; MI within the past 6 months; hypertension (> 180 mmHg systolic); impaired renal function; pregnancy; known hypersensitivity to HES or gelatin; patient taking drugs that may specifically affect blood viscosity, diuresis, or clotting | |

| Interventions | 1) 3% MFG (n = 22) 2) 6% HES (n = 19) Both groups also given RL. Fluids administered according to haemodynamic and clinical parameters | |

| Outcomes | Death (information on death was obtained by contact with the study author) Haemodynamic variables Packed cell volume, Hb, clotting times Incidence of allergic reactions | |

| Notes | 7 patients were lost to follow‐up but only 5 were accounted for. Information on method of allocation concealment was obtained by contact with the author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Allocation was by a list of random numbers read by someone not entering patients into the trial (closed list) |

Boldt 1986.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, using sealed opaque envelopes Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study authors Blinding not mentioned Loss to follow‐up not mentioned | |

| Participants | 55 patients undergoing elective aortocoronary bypass surgery Exclusion criteria were ejection fraction < 50% and LVEDP >15 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 1) 500 mL 20% HA (n = 15) 2) 500 mL 3% HES (n = 13) 3) 500 mL 3.5% Gelatin (n = 14) A fourth group received no colloid (n = 13) | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables Incidence of anaphylactic shock Amount blood transfused | |

| Notes | Follow‐up until discharge from ICU | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Boldt 1993a.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 75 men undergoing elective aortocoronary bypass grafting, who had a PCWP of < 5 mmHg after induction of anaesthesia | |

| Interventions | 1) HA 5% (n = 15) 2) 6% HES, HMW (n = 15) 3) 6% HES, LMW (n = 15) 4) Gelatin 3.5% (n = 15) 5) No additional volume | |

| Outcomes | Death (information obtained on contact with author) Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 1 day. Information on allocation was obtained on contact with study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Allocation by sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Blinding of outcome assessors not mentioned | |

| Participants | 30 consecutive trauma patients (injury severity score > 15) and 30 consecutive septic patients who underwent major surgery. Exclusions: patients suffering from renal failure requiring haemofiltration, severe liver dysfunction or coagulation abnormalities in their history were excluded as were patients who were receiving aspirin or other cyclooxygenase inhibitors | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES, LMW (15 trauma patients and 15 sepsis patients) 2) 20% HA (15 trauma patients and 15 sepsis patients) Fluid was given to maintain CVP and PCWP between 12 mmHg and 16 mmHg | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up at 5 days Deaths were reported within the study period and later (time not specified). Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 1996a.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Outcome assessors blinded to treatment | |

| Participants | 30 trauma patients and 30 patients with from sepsis secondary to major general surgery. Exclusions were patients with renal impairment, liver insufficiency, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or septic shock | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES (n = 30)

2) 20% HA solution (n = 30)

All patients also received RL Volume therapy was given to maintain PCWP between 12 mmHg and 18 mmHg |

|

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up at 5 days and at discharge from ICU | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Allocation by sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 1996b.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. The doctors giving the fluid were blinded to the solution but blinding of outcome assessors not mentioned. Loss to follow‐up not reported | |

| Participants | 45 consecutive trauma patients transferred to the surgical ICU. Inclusion criteria: injury severity score of > 15 points All patients were haemodynamically stable before being admitted to the study | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES (n = 15) 2) 20% HA (n = 15) 3) Unspecified volume therapy regimen (n = 15) The allocated solution was given to maintain CVP and or PAWP between 12 mmHg and 18 mmHg | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Circulating adhesion molecules | |

| Notes | Deaths were reported within the study period and later (left ITU). Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 1996c.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Outcome variables were collected by an investigator who was blinded to the treatment. Loss to follow‐up not reported | |

| Participants | 56 patients from the surgical ICU. 28 patients with an injury severity score > 15 and 28 patients with sepsis secondary to major surgery. Patients with renal insufficiency, urine output < 20 mL/hour, severe liver dysfunction, or disseminated intravascular coagulation were excluded | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES, LMW (14 trauma patients, 14 sepsis patients) 2) 20% HA (14 trauma patients, 14 sepsis patients) Fluid was infused to maintain PCWP at 10 mmHg to 15 mmHg | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 5 days Deaths were reported within the study period and later (time not specified) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Blinding of outcome assessors not mentioned Loss to follow‐up not mentioned | |

| Participants | 150 traumatised patients (injury severity score >15) and 150 postoperative patients with sepsis. Patients suffering from renal failure, severe liver insufficiency, or with major coagulation abnormalities were not included | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES, LMW (n = 150)

2) 20% HA (n = 150) Both for 5 days to maintain the PAWP between 12 Torr and 15 Torr |

|

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Organ function Coagulation | |

| Notes | Deaths were reported within the study period and after the study period (time not specified). Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 2000.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 150 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery | |

| Interventions | 1) 6% HES, LMW (n = 50) 2) 6% HES, MMW (n = 50) 3) 3% MFG (n = 50) To keep MAP > 70 mmHg and CVP between 10 mmHg and 14 mmHg Volume was given perioperatively until the morning of the first postoperative day. For each hour of surgery 500 mL to 800 mL of crystalloids was routinely infused | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Blood loss Blood transfused Cost | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 1 postoperative day. Deaths recorded after study period. Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Sequentially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Boldt 2001.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Volume therapy was done by doctors who did not know the aim of the study | |

| Participants | 75 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery Volume was administered to keep the CVP between 8 mmHg and 12 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 1) 6% HES (n = 25) 2) 6% HES (n = 25) 3) 4% MFG (n = 25) All groups also received 500 mL of RL for each hour of surgery | |

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Blood loss Blood units transfused | |

| Notes | There were no deaths in the study period (until first follow‐up on first postoperative day. Deaths until discharge | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. 'Closed envelope system' |

Brock 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 21 patients who had undergone cardiac surgery | |

| Interventions | 1) 10% HES 200/0.5 in 7.2% saline (n = 7) 2) 5% HA (n = 7) 3) 6% HES in 0.9% saline (n = 7) | |

| Outcomes | Death (data obtained on contact with study author) Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Data on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. Allocation by list of random numbers read by someone entering patients into the trial (open list) |

Brutocao 1996.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind controlled trial with pharmacy‐controlled randomisation | |

| Participants | 38 children aged 1 year or more who were undergoing surgical repair of a congenital heart disease. Exclusion criteria included amrinone therapy, renal disease, coagulopathy, or a known bleeding diathesis | |

| Interventions | 1) 5% Albumin (n = 18) 2) 6% HES (n = 20) Volume expansion was administered as clinically indicated to maintain adequate CVP, perfusion, and urine output. The total amount of colloid therapy was determined by care providers blinded to the randomisation | |

| Outcomes | Death (information on death was obtained on contact with the study authors) Haemodynamic variables Coagulation variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up until discharge from hospital 9 children excluded post randomisation because they did not require colloid. Information on allocation concealment was obtained on contact with the study authors | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Pharmacy‐controlled randomisation |

Carli 2000.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Not ITT analysis | |

| Participants | 164 trauma patients. Patients were included if their SBP was < 100 mmHg, associated with signs of hypoperfusion | |

| Interventions | 1) HES (Hesteril 6%) (n = 85) 2) Gelatin (Plasmion) (n = 79) | |

| Outcomes | Glasgow coma score Haemodynamic variables Units of blood transfused Adverse reaction | |

| Notes | There were 13 deaths from heart failure but these patients were excluded from the final analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. 'Each centre received instructions from the coordinating Institute on the treatment to give the patient' |

Claes 1992.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Blinding not mentioned No loss to follow‐up |

|

| Participants | 20 patients undergoing brain tumour surgery and 20 patients undergoing transabdominal hysterectomy. Exclusion criteria: pre‐existing coagulopathies, abnormal preoperative coagulation screening tests, intake of drugs affecting haemostasis within 2 weeks preoperatively, and liver or kidney dysfunction | |

| Interventions | 1000 mL of fluid for volume replacement, as 1) 6% HES (n = 19) 2) 5% HA solution in 0.9% saline (n = 21) | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables Coagulation variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 48 postoperative hours | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation or allocation |

Diehl 1982.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Blinding not mentioned No loss to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 60 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass | |

| Interventions | 1) 6% HES (n = 27) 2) 5% Albumin (n = 33) for volume expansion during the first 24 hours postoperatively. Neither hetastarch nor albumin was used intraoperatively or in the pump prime | |

| Outcomes | Death Coagulation data Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 7 postoperative days | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate. Patients were allocated to groups according to their hospital identification number |

Dolecek 2009.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, randomised according to computer‐generated randomisation list | |

| Participants | 56 patients with severe sepsis. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older and developed severe sepsis. Exclusion criteria: severe coagulopathy, pregnant, cardiac failure, acute renal failure, aortal aneurysm, severe aortal regurgitation or dysrhythmia | |

| Interventions | 1) 20% Albumin (n = 30) 2) 6% HES (n = 26) |

|

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables |

|

| Notes | Follow‐up 28 days | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Sealed opaque sequentially numbered envelopes (information obtained from authors) |

Du Gres 1989.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Blinding not mentioned No loss to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 30 patients post cardiac surgery. Patients were included if they were haemodynamically stable, were without serious 'rhythm' problems, had MAP < 90 mmHg, mean pulmonary artery pressure < 20 mmHg and CVP < 10 mmHg. Patients excluded if they needed blood transfusion, had a haematocrit < 28% or Hb < 9 g/100 mL | |

| Interventions | 1) 4% HA (n = 15) 2) Haemaccel (n = 15) | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic parameters | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 4 hours | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation |

Dytkowska 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 40 patients post cardiac surgery. Patients were excluded if they had co‐existing cardiogenic shock, renal failure with creatinine level > 3.0 mg, or severe clotting disorders | |

| Interventions | 1) 200/0 HAES 6% (n = 20) 2) Gelafundin (n = 20) Colloids were administered to patients with diagnosed symptoms of hypovolaemia, during the first 24 hours postoperatively. Infusion rate was adjusted to patients needs but it did not exceed 1000 mL/hour | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic parameters Biochemical parameters Adverse reactions | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 2 hours | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation |

Evans 2003.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Treatment blinded (fluid set up by independent operator and covered with opaque black bag) | |

| Participants | 55 patients undergoing unilateral cemented hip replacement Exclusion criteria: cardiac insufficiency, renal insufficiency, altered liver function, preoperative anaemia, preoperative coagulation abnormalities, chronic use of corticosteroids and diuretics | |

| Interventions | 1) 4.5% HA (n = 13) 2) 4% Gelosulfine (n = 14) 3) Haemacel (n = 14) 2 L of fluid was infused during the operative period A fourth group received normal saline (n = 14) | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables Total blood loss | |

| Notes | Follow‐up before surgery, at the end of the surgery, and 2 hours postoperatively | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear ‐ 'sealed envelopes' |

Falk 1988.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Blinding not mentioned No loss to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 12 patients with septic shock. Patients were excluded from the study if the pretreatment PAWP > 10 mmHg | |

| Interventions | 1) 250 mL of 5% Albumin (n = 6) 2) 250 mL of 6% HES (n = 6) Given every 15 minutes until the PAWP was increased to 15 mmHg. The test infusion was then continued at 100 mL/hour to maintain PAWP at 15 mmHg for the next 24 hours | |

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables Clotting variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 24 hours | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation |

Friedman 2008.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 34 haemodynamically stable adults with sepsis and suspected hypovolaemia. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, terminal state, PAOP > 12 mmHg, serum creatinine concentration > 3 mg/dL, severe coagulation abnormalities, history of allergy to any IV fluid | |

| Interventions | 1) 400 mL 10% HES (n=11) 2) 400 mL 6% HES (n=10) 3) 4% HA (n=13) All over 40 minutes |

|

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 160 minutes. No data on mortality or blood transfused | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear ‐ sealed, opaque envelope assignment (does not say if sequentially numbered) |

Fries 2004.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Treatment not blinded | |

| Participants | 60 patients undergoing primary knee replacement surgery Exclusion criteria: contraindications for regional anaesthesia and puncture of the radial artery, any known allergies, primary and secondary haemostatic disorder | |

| Interventions | 1) 4% Gelofusine (n = 20)

2) 6% HES (n = 20)

A third group received RL Before administrating spinal anaesthesia all patients received 500 mL RL. All patient intraoperatively |

|

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 2 hours postoperatively | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation or allocation |

Fulachier 1994.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Blinding not mentioned No loss to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 16 patients undergoing cardiac surgery (8 were undergoing valve replacement and 8 undergoing coronary bypass). Patients were excluded if they were > 80 years of age, < 18 years of age, had been included in other studies, had received colloids in the month preceding surgery, had coagulation abnormalities, or who were undergoing inotropic treatment | |

| Interventions | 1) 500 mL OF 4% solution of HA in RL (n = 8)

2) 500 mL of HES (n = 8) until starting cardiopulmonary bypass |

|

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic variables | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 30 minutes | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation or allocation |

Gahr 1981.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. No information given on method of randomisation No loss to follow‐up | |

| Participants | 20 patients with hypovolaemia following abdominal surgery for malignoma | |

| Interventions | 1) 500 mL HES 450/0.7 (n = 10)

2) 500 mL HA 5% (n = 10) during the first 24 hours after the operation |

|

| Outcomes | Haemodynamic parameters Coagulation data | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 6 hours | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear. No information given on method of randomisation or allocation |

Gallagher 1985.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 10 patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery Exclusion criteria: patients with significant left main coronary artery stenosis, poor left ventricular function, or poor pulmonary function | |

| Interventions | 1) 5% Albumin (n = 5) 2) 6% HES (n = 5) | |

| Outcomes | Death (data on deaths from study author) Haemodynamic data | |

| Notes | Follow‐up 1 day. Data on allocation obtained on contact with author | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Computerised system ‐ patient details were entered before treatment assignment was revealed |

Godet 2008.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Computer‐generated random list with randomisation in balanced blocks | |

| Participants | 65 patients aged 18 years and over with renal dysfunction undergoing abdominal aortic surgery. Exclusion criteria: endovascular aortic surgery, preoperative serum creatinine > 250 µmol/L, history or present diagnosis of severe hepatic insufficiency or coagulation disorders, dialysis, anuria, and post‐transplant surgery | |

| Interventions | 1) 6% HES (n = 32) 2) 3% Gelatin (n = 33) |

|

| Outcomes | Death Haemodynamic variables Renal safety (serum creatinine) Adverse events |

|

| Notes | Follow‐up at 6 days and 3 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate. Investigator received a set of envelopes. Envelope only opened when the patient arrived at pre‐induction anaesthesia room |

Gold 1990.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial Colloid solution was blinded by covering with foil No loss to follow‐up |

|

| Participants | 40 surgical patients undergoing AAA surgery | |

| Interventions | 1) 1 g/kg Albumin 5% solution (n = 20) 2) 1 g/kg Hetastarch 6% solution (n = 20) | |

| Outcomes | Death (data on death was obtained on contact with the author) Haemodynamic and coagulation variables | |