Abstract

Background

Asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux are both common medical conditions and often co‐exist. Studies have shown conflicting results concerning the effects of lower oesophageal acidification as a trigger of asthma. Furthermore, asthma might precipitate gastro‐oesophageal reflux. Thus a temporal association between the two does not establish that gastro‐oesophageal reflux triggers asthma. Randomised trials of a number of treatments for gastro‐oesophageal reflux in asthma have been conducted to determine whether treatment of reflux improves asthma.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments for gastro‐oesophageal reflux in terms of their benefit on asthma.

Search methods

The Cochrane Airways Group trials register, review articles and reference lists of articles were searched.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of treatment for oesophageal reflux in adults and children with a diagnosis of both asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux.

Data collection and analysis

Trial quality and data extraction were carried out by two independent reviewers. Authors were contacted for confirmation or more data.

Main results

Twelve trials met the inclusion criteria. Interventions included proton pump inhibitors (n=6), histamine antagonists (n=5), surgery (n=1) and conservative management (n=1). Treatment duration ranged from 1 week to 6 months. A temporal association between asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux was investigated in 4 trials and found to be present in a proportion of participants in these trials. Anti‐reflux treatment did not consistently improve lung function, asthma symptoms, nocturnal asthma or the use of asthma medications.

Authors' conclusions

In asthmatic subjects with gastro‐oesophageal reflux, (but who were not recruited specifically on the basis of reflux‐associated respiratory symptoms), there was no overall improvement in asthma following treatment for gastro‐oesophageal reflux. Subgroups of patients may gain benefit, but it appears difficult to predict responders.

Plain language summary

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux treatment for asthma in adults and children

People with asthma also often have gastro‐oesophageal reflux (where acid from the stomach comes back up the gullet (esophagus)). Reflux is very common in people with asthma. It may be a trigger for asthma, or alternatively, asthma may trigger reflux. Treatments that can help reflux include antacids and drugs to suppress stomach acids or empty the stomach. This review of trials found that using reflux treatments does not generally help ease asthma symptoms. While asthma may be improved in some people, it was not possible to predict who might benefit.

Background

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux (GOR) is the passage of gastric contents through the gastric cardia into the oesophagus. This can be a normal physiological event that occurs mainly after meals during the day in healthy people. Abnormal reflux occurs when there is significant acid exposure (pH< 4.0) to the distal oesophagus for more than 1.2 hours (cumulative time > 5%) over a twenty‐four hour period as established by intra‐oesophageal pH monitoring (Johnson 1974; Johnsson 1987). Abnormal reflux is associated with upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. It is also reported to be associated with non‐gastro‐intestinal symptoms including chest pain, cough, wheezing and with worsening asthma.

Asthma and GOR are both common medical conditions and recent studies show that they often co‐exist. For example, Sontag 1990 studied 104 adult asthmatics and found that more than 80% had abnormal gastro‐oesophageal reflux on 24 hour pH monitoring. Compared with control subjects, asthmatic individuals with reflux had significantly decreased lower oesophageal sphincter pressures, greater oesophageal acid exposure times, more frequent reflux episodes, and longer acid clearance irrespective of body position and bronchodilator therapy. They also found oesophagitis or Barrett's oesophagus on endoscopy in 73 out of 186 consecutive and unselected asthmatics who consented to the procedure. Paediatric studies similarly show a high prevalence of significant gastro‐oesophageal reflux in children with asthma (Andze 1991; Tucci 1993; Martin 1982).

The role of GOR as a trigger factor in asthma is an important issue. Several mechanisms by which oesophageal reflux may trigger asthma have been proposed. These include: acid aspiration (Klotz 1971; Mays 1976), direct acid stimulation of the oesophagus or stimulation of vagal nerves which heightens bronchial responsiveness to extrinsic allergens (Mansfield 1989; Tuchman 1984). However, studies in humans with asthma have shown conflicting results concerning the effects of lower oesophageal acidification as a trigger of asthma. Furthermore the possibility also exists that asthma might precipitate GOR (Singh 1983). Thus a temporal association between the two does not conclusively establish that GOR triggers asthma.

Therapy of gastro‐oesophageal reflux can involve a number of measures. These include anti‐reflux measures, histamine (receptor type 2) antagonists either in standard dose or high dose, proton pump inhibitors, cisapride, and surgical therapy including Nissen fundoplication and partial posterior hemi‐fundoplication (Toupet and Lind techniques). Narrative reviews have identified the high frequency of gastro‐oesophageal reflux in people with asthma, the clinical features and diagnosis and the spectrum of therapy available. They have also identified that randomised trials have been conducted on each form of therapy with conflicting results (Winter 1997; Choy 1997 ; Kahrilas 1996; Simpson 1995, Field 1998). A systematic review of antireflux surgery on asthmatics found that surgery may improve asthma symptoms but not pulmonary function (Field 1999).

The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the literature concerning treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux in asthma, and its effect on asthma.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment for gastro‐oesophageal reflux in adults and children with asthma, in terms of its benefit on asthma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials of gastro‐oesophageal reflux therapy in patients with asthma which report asthma outcomes.

Types of participants

Asthma: Objective confirmation by history, doctor's diagnosis, and evidence of variable expiratory airflow obstruction.

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux: symptoms or objective documentation by 24 hour pH studies, or oesophagoscopy with or without biopsy.

Types of interventions

These include:

Anti‐reflux measures

Histamine antagonists standard dose

Histamine antagonists high dose

Proton pump inhibitors

Cisapride

Surgical therapy

Types of outcome measures

The following outcomes were evaluated:

Asthma symptoms, lung function, exacerbations, unscheduled visits to the doctor, ER visits, hospitalisation, airway hyper responsiveness, treatment preference.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Airways Group asthma RCT register was searched using the terms: "asthma" AND "gastro‐oesophageal reflux" OR "gastroesophageal reflux" OR gastro‐esophageal reflux" OR "reflux" OR "ger" OR "gerd" OR "acid" OR "esophagus" AND "cimetidine" OR "ranitidine" OR "famotidine" OR "nizatidine" OR "omeprazole" OR "pantoprazole" OR "lansoprazole" OR "surgery" OR "Nissen".

Data collection and analysis

IDENTIFICATION OF RELEVANT STUDIES: All identified abstracts were assessed independently by two reviewers. The full text version of each potential article was obtained for assessment by two independent reviewers to establish whether it met the inclusion criteria. The percentage agreement for inclusion/exclusion of studies was 100%.

QUALITY: Study quality was assessed independently and scored by two reviewers using two instruments. The first, the Jadad system, allows for a score between 0 and 8 with higher scores indicating a better description of the study (Moher 1995). The Jadad system measures the clarity of the description of: inclusion criteria, randomisation, adverse effects, blinding, treatment of withdrawals and dropouts and statistical analysis. Studies were further assessed as "Adequate", "Inadequate" or "Unclear" according to the actual methods used for randomisation and concealment of allocation. In this assessment, if studies are either not truly randomised (e.g. alternated) or if allocation to treatment or control groups is not truly blinded, studies are considered "inadequate". If the author does not fully state these methods, the study is characterised as "unclear" until the author is contacted and clarification can be made.

OUTCOMES:

The following health outcomes were identified for assessment: Admission/readmission rate Emergency room visits Unscheduled doctor visits Lung function: spirometry, measured as forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) Use of 'rescue' (or reliever) medications Nocturnal symptoms Symptoms score Airway hyper responsiveness Treatment preference

AUTHOR CONTACT:

Authors were contacted to verify and provide further information about methodological approaches and outcomes data.

ANALYSIS:

Outcomes were analysed as continuous or dichotomous outcomes, using standard statistical techniques.

For continuous outcomes, the weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardised mean difference(SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk was calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

Revman software has been designed for use with parallel designed studies. For the crossover designed trials the confidence intervals were compared to the original paired t‐test when reported in the trial.

SUB‐GROUP ANALYSIS:

Outcomes were analysed according to the type of intervention the subjects received (i.e. medical or surgical treatment).

Medical interventions were sub grouped according to the type of therapy:

H2 antagonist

Proton Pump Inhibitor

Conservative therapy

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy yielded 261 abstracts of which 22 full text versions of papers and one abstract were retrieved. Of these, twelve randomised controlled trials were included of which nine were cross‐over trials and three were of a parallel design.

Four trials investigated histamine antagonists (Gustafsson 1992, Ekstrom 1989, Nagel 1988, Goodall 1981), six investigated proton pump inhibitors (Ford 1994; Meier 1994; Teichtahl 1996; Boeree 1998; Levin 1998; Kiljander 1999); one assessed conservative treatment of GOR (Kjellen 1981) and one had three arms which included a surgical approach, a histamine antagonist and a placebo control (Larrain 1991).The studies are described below according to their design, participant characteristics, intervention characteristics and outcomes reported.

Included studies

STUDY DESIGN: Nine of the twelve studies were randomised controlled cross‐over trials (Ekstrom 1989; Ford 1994; Gustafsson 1992; Goodall 1981; Meier 1994; Nagel 1988;Teichtahl 1996; Levin 1998; Kiljander 1999) with the other three studies (Larrain 1991; Kjellen 1981; Boeree 1998) conducted as parallel randomised controlled trials without crossover.

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS: Number of participants: The number of participants randomised ranged from 11 (Ford 1994) to 90 (Larrain 1991). The mean completion rate was 90% for the eleven studies reporting this statistic. Age: With the exception of Gustafsson who studied children and adolescents aged between 10 and 20 years, all trials investigated adults. In the adult studies, mean ages ranged from 42 years (Nagel 1988) to 63 years (Ford 1994). Overall the mean age was 48 years and ranged between 22 to 80 years.

Recruitment: Subjects were primarily outpatients recruited from respiratory or asthma/allergy clinics. Teichtahl 1996 was the only study to recruit from both respiratory and gastroenterology outpatient clinics.

Diagnostic criteria for asthma: The following methods were reported as the methods used to diagnose asthma for inclusion of subjects into the respective studies: American Thoracic Society criteria:‐ Ekstrom 1989; Meier 1994; Kjellen 1981;Kiljander 1999 Doctor's diagnosis:‐ Ford 1994; Nagel 1988; Goodall 1981; Gustafsson 1992; Teichtahl 1996; Patient report of wheezing or shortness of breath:‐ Larrain 1991. Objective lung function:‐ Boeree 1998, Levin 1998

Baseline severity of asthma: The severity of asthma was documented in different ways. Where baseline data were not reported, the inclusion criteria for the study have been substituted as an indicator of asthma severity. Two studies did not specify the severity of asthma nor report specific criteria of asthma severity for inclusion (Ekstrom 1989; Gustafsson 1992). However, the asthma medications used by subjects in the Gustafsson trial indicate the inclusion of subjects with moderate to severe asthma. The severity of asthma in the other studies was reported in the following manner: Boeree:‐ >=20% fall post methacholine challenge, ICS >= 0.4mg/day, mean baseline PEF 329/321 l/min, Ford:‐ mean baseline PEF 253‐300 l/min, Goodall: nocturnal wheezing present in all subjects, Kiljander:‐ >15% reversibility post bronchodilator or >=20% PEF diurnal variation or PD20 methacholine, Kjellen: stated that their subjects suffered 'more severe' asthma, Larrain: 56/81 had reactive airways and 35/81 used corticosteroids, Levin:‐ >=15% reversibility post bronchodilator, mean baseline FEV1 1.9 L Meier: > 15% reversibility after bronchodilator (FEV1 & PEF), Nagel: > 25% reversibility after bronchodilator (FEV1 & PEF), Teichtahl: >15% reversibility after bronchodilator (FEV1) and diurnal variation of PEF of > or = 20% in PEF documented in past 6 months.

Diagnostic criteria of GOR: The methods used to diagnose GOR included: history of symptoms endoscopy manometry acid perfusion test 24 hour pH monitoring oesophageal motility All studies employed more than one of the above methods to confirm GOR.

Baseline severity of GOR: Baseline severity of GOR was described in the following ways:

Boeree Dysphagia n=3/3; heartburn n= 9/12; regurgitation n = 3/7 Ekstrom All had symptoms of GOR Ford Esophagitis: Grade I n=1; Grade II n=1; Grade III n=3; Barrett's oesophagus n=2 Goodall Esophagitis 11/20; abnormal pH Score 8/18; Decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure (LESP) 8/20; abnormal pH 8/20; heartburn 19/20; regurgitation 12/20. Gustafsson Mean (SEM) % time pH < 4 = 0.5 (0.1); 2.7 (0.3). Kiljander 20% had no GOR symptoms Kjellen Hiatial hernia 55%; dysmotility 58%; abnormal pH 35%; Decreased LESP 40%. Larrain Esophagitis: Grade 1 n=20/81; Normal n=60/81 Free reflux on radiography n=38/81 Abnormal lower oesophageal pH after 300 ml Loading of the stomach with HCl solution. Heartburn 60/81. Levin Mean % of time pH<4 = 24.4% Meier Esophagitis 15/15: Grade I n=1; Grade II n=4; Grade III n= 8; Grade IV n=2. Stricture n=8/15. Barrett's oesophagus n=2/15 Hiatal hernia n=10/15 Mean distal probe pH score 60.5. Nagel All had reflux symptoms which occurred at least once Every 6 weeks. Patient history of GOR related respiratory Symptoms and 24 hour pH monitoring. Association Required for entry. Teichtahl Esophagitis: Grade 0 n=3; Grade I n=4; Grade 2 n=11; Grade 3 n=2. Mean % of time pH < 4 = 12.2%. 24‐hour pH monitoring conducted.

Symptomatic GOR: number symptomatic/number of subjects Boeree Dysphagia n=6; heartburn n= 21; regurgitation n = 10 Ekstrom 48/48 Ford 10/10 Goodall 19/20 Gustaffson 18/37 Kjellen not specified Kiljander not specified Larrain 60/81 Levin 11/11 Meier 15/15 Nagal 14/14 Teichtahl 19/20

INTERVENTION CHARACTERISTICS: Interventions were characterised according to the type of intervention (Medical or Surgical). For medical interventions, we further noted the type of pharmacological agent (and dose) or type of conservative therapy. We also documented the length of time of exposure to the treatment.

A Medical Interventions: i) Histamine antagonist studies Trial Agent Dose/day Treatment Duration Ekstrom ranitidine 300 mg 4 weeks Goodall cimetidine 1000 mg 6 weeks Gustafsson ranitidine 150 or 300 mg 4 weeks Larrain cimetidine 1200 mg 26 weeks Nagel ranitidine 450 mg 1 week

ii) Proton Pump Inhibitor studies: Trial Agent Dose/day Treatment Duration Boeree omeprazole 80mg 12 weeks Ford omeprazole 20 mg 4 weeks Kiljander omeprazole 160mg 8 weeks Levin omeprazole 20mg 8 weeks Meier omeprazole 40 mg 6 weeks Teichtahl omeprazole 40 mg 4 weeks

iii) Conservative anti‐reflux therapy study: Kjellen 1981 was the only study to investigate non‐pharmacological conservative reflux therapy. The intervention included raising the head of the bed, drinking warm water after meals, not eating for 3 hours prior to bed time, anti‐reflux medication as required, refraining from aspirin and anticholinergic preparations and avoidance of procedures which increase intra‐abdominal pressure. This was a parallel study where outcome measures were taken over six weeks.

B. Surgical Interventions: There was only one surgical intervention study (Larrain 1991) which randomised subjects to either a medical therapy (cimetidine above) or an identical placebo or surgery. The surgical approach used was a posterior gastropexy. Outcomes were measured after 26 weeks in a parallel study design.

OUTCOMES: No studies measured or reported hospitalisations or emergency room visits. Only one author provided data for unscheduled visits to the doctor for asthma (Teichtahl 1996). Lung function, symptoms and use of asthma medications were the most popular outcomes investigated. However, these outcomes were reported in several different ways which has limited our capacity to combine the data in a meta‐analysis. The data have been requested from the authors, in a form that will enable combination.

Risk of bias in included studies

Each study was scored according to the 0‐8 point scale of Jadad accompanied by a separate rating of the allocation procedure where A indicates appropriate blinding, B unclear and C, an inadequate allocation procedure.

All studies were appropriately randomised except for Kjellen 1981 which used alternation to allocate subjects into treatment or control groups.

Nine of the twelve studies used blinded allocation procedures. The range of Jadad ratings was (4‐7), the mode 7 and the mean 6.4 indicating only minimal opportunity for bias among these studies.

The quality ratings for the trials were: Ekstrom 1989 A7, Ford 1994 A6, Goodall 1981 A6, Gustafsson 1992 A7, Kjellen 1981 C4, Larrain 1991 A7, Meier 1994 A7, Nagel 1988 B6, Teichtahl 1996 B6, Boeree 1998 B7, Levin 1998 B7, Kiljander 1999 B7.

Effects of interventions

The twelve RCTs investigated the treatment of GOR on asthma in 432 patients of whom 396 completed. The studies were inconsistent in reporting outcomes, and this has prevented quantitative data synthesis (meta‐analysis) for many outcomes. No studies reported hospitalisations or emergency room visits resulting from asthma. Lung function was reported in several different ways (see Table). Overall, there was no consistent benefit of anti‐reflux treatment on lung function in asthmatics with GOR.

LUNG FUNCTION:

| Outcome | Number of studies | Measured Significant Improvement |

| FEV1 | 11 | 2 (Meier 1994; Larrain 1991) |

| am PEF | 8 | 1 (Levin 1998) |

| pm PEF | 7 | 2 (Teichtahl 1996; Goodall 1981) |

| day PEF | 4 | 0 |

| Airway hyper‐responsiveness | 4 | 0 |

FORCED EXPIRATORY VOLUME IN ONE SECOND (FEV1):

Ten trials of eleven interventions (five proton pump inhibitor, four H2 antagonist, one conservative therapy and one surgical intervention) reported FEV1. One study reported a 20% improvement in FEV1 favouring omeprazole in four of 14 subjects (Meier 1994). The mean percentage change in FEV1 was 10% (p<0.05). No other studies reported a significant improvement in FEV1 in either the proton pump inhibitor (Boeree 1998, Levin 1998, Kiljander 1999, Teichtahl 1996), histamine antagonist (Gustafsson 1992; Ekstrom 1989; Goodall 1981; Larrain 1991), conservative therapy (Kjellen 1981) or surgical (Larrain 1991) groups.

PEAK EXPIRATORY FLOW (PEF):

An improvement in morning PEF was reported in only one of the eight studies that reported this variable (Levin 1998). Treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux with either omeprazole (Boeree 1998, Kiljander 1999, Teichtahl 1996; Ford 1994) or histamine antagonists (Ekstrom 1989; Goodall 1981; Nagel 1988) had no significant effect on morning PEF in the seven remaining studies. A significant improvement in evening PEF, measured as percentage of predicted, was reported after treatment with omeprazole 40 mg/day for four weeks (Teichtahl 1996) and after treatment with cimetidine 1000 mg/d for six weeks (Goodall 1981). However, no effect of treatment on evening PEF was seen in five other studies (Boeree 1998; Ekstrom 1989; Ford 1994; Levin 1998; Nagel 1988). In an unpaired analysis of three studies (Ekstrom 1989; Ford 1994; Teichtahl 1996) using the PEF endpoint in l/min there was no significant treatment effect on evening PEF [7.0 (‐26 to 40) (WMD 95%CI)]. Similarly, no treatment effect was found in four studies which reported daytime PEF (Ford 1994; Goodall 1981; Gustafsson 1992; Meier 1994).

AIRWAY HYPERRESPONSIVENESS (AHR):

AHR was not effected by omeprazole therapy (Boeree 1998; Teichtahl 1996) nor treatment with an H2 antagonist (Gustafsson 1992; Ekstrom 1989).

ASTHMA SYMPTOMS:

| Outcome | Number of studies | Significant improvement |

| Asthma symptoms | 12 | 3 (Kjellen 1981; Larrain 1991;Levin 1998) |

| Nocturnal asthma score | 6 | 3 (Goodall 1981; Ekstrom 1989; Kiljander 1999)) |

Asthma symptoms were measured and reported in all of the included studies. The variety of ways in which symptoms were reported using several different scales, has precluded meta‐analysis except for nocturnal symptom scores. Overall, the majority of studies failed to demonstrate an improvement in asthma symptoms.

Asthma Symptoms: Three studies of adults reported a significant improvement in asthma symptoms (Ekstrom 1989; Larrain 1991; Levin 1998). Kjellen 1981, reported a significant reduction in the proportion of subjects experiencing respiratory symptoms (dyspnoea, cough, wheeze and expectoration) in a study of conservative therapy for GOR. A subgroup analysis showed that subjects with "endogenous asthma" improved significantly in all symptom outcomes but subjects with "exogenous asthma" did not. Larrain 1991 found significant improvement in both treatment groups (cimetidine and surgical p<0.001) as well as the placebo group (p<0.02) when comparing the change in asthma symptoms from baseline to follow‐up. The cimetidine (p<0.03) and surgical (p<0.01) groups showed significant improvement in asthma symptoms over the placebo group after six months with 13 of the 27 cimetidine‐treated patients and nine of the 26 surgically treated patients reporting a total abolition of symptoms compared with only one of the 28 control subjects. Levin 1998 reported an improvement in asthma related quality of life for subjects receiving omeprazole. The remaining nine trials did not demonstrate a benefit of GOR treatment on asthma symptoms

Nocturnal Asthma: Ekstrom 1989 reported a significant, but clinically modest, improvement in nocturnal asthma symptom scores after treatment with a histamine antagonist (p<0.02). When sub grouped into subjects who had a history of reflux associated respiratory symptoms and those without, the former showed a statistically significant ranitidine related improvement (p<0.001). Goodall 1981 also demonstrated a positive effect of a histamine antagonist on nocturnal asthma (p<0.05). Kiljander 1999 reported a significant improvement in night‐time asthma symptoms for high dose omeprazole (p<0.04). Gustafsson 1992 reported significant positive correlations between the improvement of nocturnal, morning and total asthma symptoms and the degree of pathological GOR at oesophageal pH monitoring in children and adolescents. However, neither Boeree 1998, Gustafsson 1992 nor Ford 1994 demonstrated a benefit of GOR treatment on nocturnal asthma symptoms.

ASTHMA MEDICATIONS

| Outcome | Number of studies | Significant improvement |

| Beta agonist use | 7 | 3 (Ekstrom 1989; Kjellen 1981; Larrain 1991) |

| Asthma medications | 1 | 1 (Kjellen 1981) |

| Steroid use | 1 | 1 (Larrain 1991) |

| Oral Corticosteroids | 1 | 0 |

Three of seven studies reported a significant reduction in beta agonist use. Ekstrom 1989 reported a reduction in mean puffs/day in the ranitidine treated group (p< 0.01). When sub grouped into subjects who had a history of reflux associated respiratory symptoms and those without, the former showed a statistically significant reduction in beta agonist use with ranitidine treatment (p<0.05). However a reduction from 5.9 (0.92) to 5.2 (0.88) puffs per day is of doubtful clinical significance. Kjellen 1981 also reported a significant reduction in the consumption of beta‐adrenergic sprays in the treatment group (4.4 to 3.8 doses /day) (p< 0.05). Larrain 1991 recorded a total medication score which most likely included all inhaled and oral asthma medications, and found a significant reduction from base‐line to follow‐up at six months in both the cimetidine and surgical groups and a non‐significant increase in the placebo group. Four other trials which reported beta‐agonist use did not find a treatment related improvement in drug consumption (Ford 1994; Goodall 1981; Meier 1994; Nagel 1988) despite adequate power to do so.

Larrain 1991 reported that three of 11 surgically treated patients and two of 13 cimetidine treated patients were able to discontinue long‐term corticosteroid treatment compared with none of 14 control subjects.

TREATMENT PREFERENCE: A significant preference for treatment was found in two studies (Goodall 1981; Ford 1994). In the first of these (Goodall 1981) 14/17 preferred active treatment compared to 3/17 preferring placebo , whilst in the second (Ford 1994) 7/11 preferred active treatment and none preferred placebo. A third study (Gustafsson 1992) which reported this outcome did not show a significant difference, with 5/18 preferring active treatment and 4/18 placebo.

GASTRO‐OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX INDUCED ASTHMA Four studies (Ekstrom 1989; Goodall 1981; Meier 1994; Nagel 1988) identified subjects in whom reflux appeared to trigger asthma. In these subjects, although gastro‐oesophageal reflux was temporally associated with asthma, no consistent benefit of gastro‐oesophageal reflux therapy was demonstrated on asthma outcomes.

EFFECT OF TREATMENT ON GASTRO‐OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX The effect of study treatment on gastro‐oesophageal reflux was reported in 11 of 12 trials. Symptoms were assessed in 10 studies and study treatment improved reflux symptoms in only five of them. The effect of treatment on oesophageal pH was assessed in three studies and was improved by high dose omeprazole (Boeree 1998) and surgery (Larrain 1991) but not by H2 antagonists Larrain 1991) or low dose omeprazole Teichtahl 1996).

Discussion

In this systematic review of twelve trials, the treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux did not reveal a consistent benefit on asthma. There was no clear effect on lung function, airway responsiveness or asthma symptoms. Although nine of the twelve trials reported at least one significant outcome, there was no consistency in these effects.

Most studies assessed the effect of GOR treatment on lung function. Only two studies found improved evening peak expiratory flow (Goodall 1981; Teichtahl 1996). One might anticipate that if treatment of GOR were beneficial in asthma, the morning PEF would be more likely to improve (as a manifestation of managing nocturnal symptoms). However only one trial found improved morning PEF (Levin 1998). Overall comparisons of medical treatment of GOR versus placebo did not find better morning or evening PEF.

Other measurements of lung function were reported. Although two studies (Meier 1994; Larrain 1991) showed improved FEV1 with medical therapy, eight other trials found no beneficial outcome. Unfortunately the different ways reporting FEV1 (such as change from baseline, means without a measure of variance, medians and ranges, mean percentage predicted as opposed to mean litres per minute) precluded a meta‐analysis. In four trials which measured airway hyper responsiveness, no benefit of therapy was observed. In summary, lung function tests failed to reveal consistent advantages of treatment for GOR in asthmatics. A limitation of this conclusion is that we were unable to combine the data in a meta‐analysis.

Asthma or respiratory symptoms were outcomes in all twelve studies. Six studies used nocturnal symptoms as an outcome, with positive findings reported by Ekstrom 1989, Kiljander 1999, Gustafsson 1992 and Goodall 1981. Meta analysis showed a tendency for benefit from histamine antagonists but this failed to reach statistical significance. Both the Larrain 1991 and Kjellen 1981 studies reported an improvement in wheezing. Of the seven trials that reported the use of beta agonists, only the Ekstrom and Kjellen papers reported positive results.

Treatment preference was significantly in favour of active treatment in two studies, but there is a major limitation with this outcome factor in that it is likely that the patient preference reflected an improvement in the reflux rather than an improvement in asthma.

In general, the participants in these studies were selected on the basis of having a diagnosis of asthma and GOR. Not all subjects demonstrated symptomatic GOR. Furthermore, a requirement to demonstrate that GOR precipitated asthma was an entry criterion in only two studies. An association was found to be present in a subset of subjects in four of the trials. As such, the appropriate conclusion is that in unselected asthmatics no consistent improvement in asthma is seen with GOR treatment. It remains possible that GOR therapy may improve asthma in a subgroup of asthmatics in whom GOR precipitates asthma. Two reports (Meier 1994; Nagel 1988) studied participants in whom GOR was objectively demonstrated to precipitate asthma. Although FEV1 improved in one study, other outcomes were negative. This finding contrasts with prior uncontrolled studies (Harding 1986) which demonstrate good response of GOR treatment in this subgroup of asthmatics.

Although twelve good quality studies were available for this systematic review, the interventions used and the outcomes assessed were not consistent. There was a wide variation in the treatment of GOR used (ranitidine in three, cimetidine in two, omeprazole in six, non pharmacological in one and surgery in one), their dosages and the duration of therapy. Similarly the outcomes varied widely. Even when the outcomes appeared similar, they were often reported in several ways, which limited our capacity to combine studies.

The duration of drug therapy was often short, and it might be argued that a longer period of observation would be necessary before improved control of GOR resulted in benefits for asthma. Indeed, when treatment was given for 6 months (Larrain 1991), the results were positive. Studies consistently averaged the results over the entire treatment period for symptom scores, PEF, and medication use. If the effect of treatment were delayed, or required time to be manifest, then averaging results over the entire treatment period would bias against finding a treatment effect. The likely implication is that these studies might underestimate the response to GOR therapy.

A further problem is insufficient sample size in the pooled studies to detect a clinically significant treatment effect. It is therefore possible that current studies are negative because of a type 2 error. Using the estimates of sample variance from the meta‐analysis of PEF data, a sample size of 506 subjects in a parallel study would be required to detect a difference in PEF of 20 litre/min with alpha at 0.05 and power of 80%.

Our original intention had been to look at the effect of treatment of GOR in both adults and children with asthma. The paucity of appropriate paediatric studies limited the scope of the final review, with the Gustafsson paper the only one that included children (age range for patients in this study 10‐20 years, mean age 14.2 years). There is no way of determining whether the observations made in this systematic review are generalisable to children with asthma and GOR.

The relationships between asthma and GOR have been well recognised. Both conditions are common and would be expected to coexist, purely on the basis of chance. Studies in children (Andze 1991, Tucci 1993, Martin 1982) and adults (Sontag 1990) have found a high prevalence of gastro‐oesophageal reflux in patients with asthma suggesting that the relationship may be causal. A number of mechanisms could be invoked to explain how GOR would trigger asthma. Aspiration of gastric contents into the airways is an obvious possibility. Similarly acid stimulation of vagal nerve fibres in the mid‐oesophagus can result in wheeze (Mansfield 1989). On the other hand, large intrathoracic pressure swings associated with acute exacerbations of asthma might result in asthma promoting reflux. Clinical observation suggests that there are individuals in whom GOR is an important trigger to asthma. However, it is unclear as to whether or not this is a common phenomenon.

In order for treatment for GOR to have a beneficial effect on asthma, it needs to be effective in controlling reflux. This review found a variety of treatments for reflux, with surgical, medical and non pharmacological therapies. The duration and dosage of medication varied between studies. It is also not clear from the available data whether the therapies treated the reflux successfully, because the outcomes were not reported with sufficient consistency. In three studies, use of a proton pump inhibitor (Ford 1994) or a histamine antagonist (Goodall 1981; Gustafsson 1992) was associated with a treatment preference over placebo, which suggests that the patients in these studies were experiencing a decrease in symptoms of reflux. An optimal study design would establish that the reflux was controlled as a prerequisite to an assessment of the effect on the asthma.

Future research is warranted to examine the effects of therapy for GOR on asthma control. A parallel group RCT using a proton pump inhibitor for up to 6 months would be appropriate. Subjects with symptomatic asthma and symptomatic GOR in whom GOR was documented to precipitate episodes of asthma should be studied. Such trials should include assessment and standardised reporting of asthma symptoms, quality of life, lung function, symptom and PEF diary, and an assessment of the effects of therapy on GOR. The data should be evaluated as change from baseline, or data during the last few weeks of therapy should be compared between groups.

This systematic review found a heterogeneous group of trials with a variety of outcomes. Although the majority of studies reported at least one statistically significant response, the overall findings from the twelve studies are inconsistent. Treatment of GOR will not help all patients with asthma; the possibility remains that a subgroup will receive benefit, however this requires evaluation in further studies. It is not possible to recommend medical treatment of GOR as a means to improve asthma. Clearly, if GOR exists it should be managed appropriately in order to control the symptoms and complications of GOR. There are opportunities for further research to evaluate the role of surgical therapy for GOR, and to establish if treatment of GOR improves asthma in those patients in whom objective tests show that GOR triggers asthma.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

In subjects who had both asthma and GOR, treatment for GOR did not produce a consistent improvement in asthma symptoms. A subgroup of subjects was reported to gain benefit but it appears difficult to predict responders. At present it is not possible to recommend medical treatment of GOR as a means to control asthma.

Implications for research.

It is recommended that future studies should be performed to identify the optimal therapy for GOR in asthma, the optimal drug dosages and duration of therapy. Such studies should be of adequate duration and measurements should be made in the later period on therapy rather than during the entire treatment course. Consideration should also be given to recruitment of participants with proven GOR‐induced asthma.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 September 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following authors for responding to our request for further information about their studies: Dr. T. Ekstrom Dr P.M. Gustafsson Dr A. Larrain Dr H. Teichtahl

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

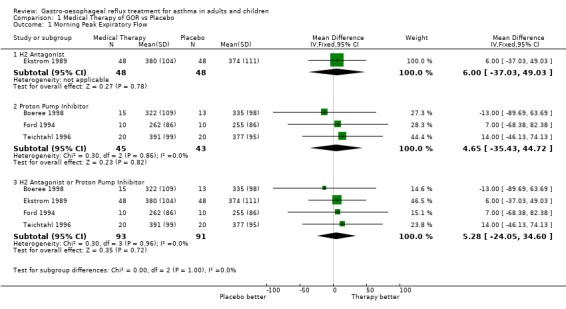

| 1 Morning Peak Expiratory Flow | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 H2 Antagonist | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.0 [‐37.03, 49.03] |

| 1.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 3 | 88 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.65 [‐35.43, 44.72] |

| 1.3 H2 Antagonist or Proton Pump Inhibitor | 4 | 184 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.28 [‐24.05, 34.60] |

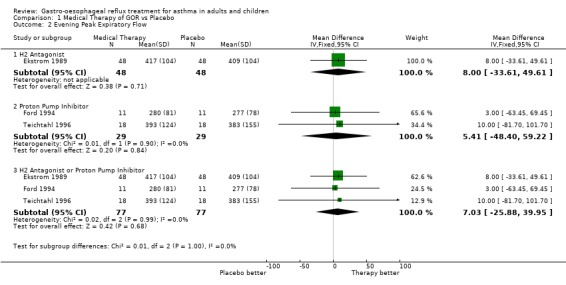

| 2 Evening Peak Expiratory Flow | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 H2 Antagonist | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.0 [‐33.61, 49.61] |

| 2.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 2 | 58 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.41 [‐48.40, 59.22] |

| 2.3 H2 Antagonist or Proton Pump Inhibitor | 3 | 154 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.03 [‐25.88, 39.95] |

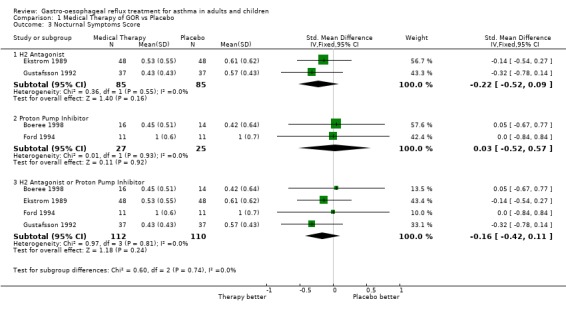

| 3 Nocturnal Symptoms Score | 4 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 H2 Antagonist | 2 | 170 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.52, 0.09] |

| 3.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 2 | 52 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.52, 0.57] |

| 3.3 H2 Antagonist or Proton Pump Inhibitor | 4 | 222 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.16 [‐0.42, 0.11] |

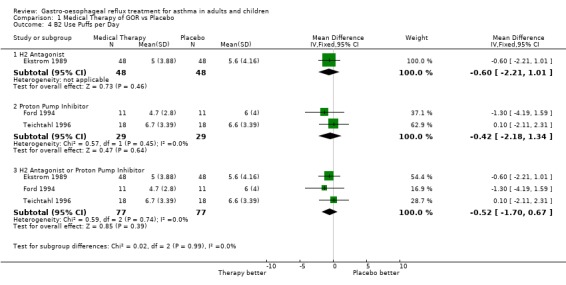

| 4 B2 Use Puffs per Day | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 H2 Antagonist | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐2.21, 1.01] |

| 4.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 2 | 58 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐2.18, 1.34] |

| 4.3 H2 Antagonist or Proton Pump Inhibitor | 3 | 154 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.52 [‐1.70, 0.67] |

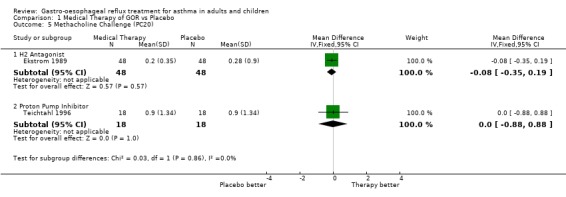

| 5 Methacholine Challenge (PC20) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 H2 Antagonist | 1 | 96 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.35, 0.19] |

| 5.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 1 | 36 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.88, 0.88] |

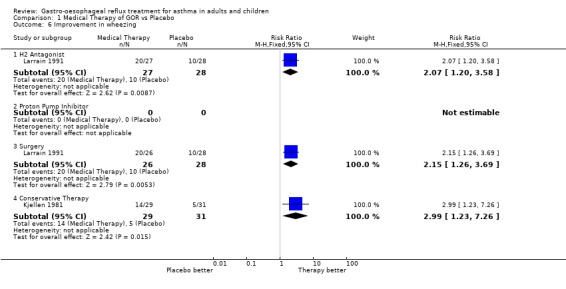

| 6 Improvement in wheezing | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 H2 Antagonist | 1 | 55 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.07 [1.20, 3.58] |

| 6.2 Proton Pump Inhibitor | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.3 Surgery | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [1.26, 3.69] |

| 6.4 Conservative Therapy | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.99 [1.23, 7.26] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Morning Peak Expiratory Flow.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 2 Evening Peak Expiratory Flow.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 3 Nocturnal Symptoms Score.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 4 B2 Use Puffs per Day.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 5 Methacholine Challenge (PC20).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Medical Therapy of GOR vs Placebo, Outcome 6 Improvement in wheezing.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Boeree 1998.

| Methods | Study Design: Parallel Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Computer generated random list. Stratified by PC20 >= 0.6mg/ml or <0.6mg/ml. Concealment of Allocation: unclear Double‐Blinding: Yes Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 36 completed: 30 Mean age (SD): intervention 51(10); Control 52 (17) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Objective ‐ methacholine challenge >=20% fall; reversibility to ipratropium bromide. Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: 24 hr pH monitoring ‐ intra oesophageal pH <4.0. GER defined as >4% of 24hr registration. Manometry Association between GOR & Asthma tested? No H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: COPD Major exclusions: other concomitant lung disease Baseline severity of asthma: FEV1 % predicted mean (SD): Intervention 66(20; Control 75(23). PEF mean (SD) Intervention 329 (91); Control 321 (109) Baseline Severity of GOR: all had documented increased acid reflux . Baseline Complications of GOR: number experiencing symptoms for intervention and control groups: Dysphagia Int: n=3, Cont n=3; Heartburn Int n=9, Cont n=12; Regurgitation Int n=3, Cont n=7. | |

| Interventions | Proton pump inhibitor Omeprazole 40mg twice daily or placebo. Duration of intervention: 12 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: at baseline and every 4 weeks for 3 month duration of study. Outcomes measured: PEF, FEV1, asthma symptoms, PC20 methacholine, heartburn, 24hr pH monitoring. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available (Cochrane Grade B) |

Ekstrom 1989.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Randomised according to "Principles of Medical Statistics" 9th Ed. in groups of 10 patients. Randomisation performed by Glaxo, Sweden. Concealment of Allocation: Adequate Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Investigated and reported as not being found. Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 50 Number completed: 48 Mean age (range):58.5 (28‐70) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: ATS Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: ‐ Symptoms (heartburn and/or acid regurgitation n=48) ‐ 24 hour pH monitoring (abnormal n=32) ‐ acid perfusion test (abnormal n=27) Association between GOR & Asthma tested? Yes ‐ Association not required for entry ‐ Association tested by history / symptoms ‐ 27/48 had one or more reflux associated respiratory symptom. H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: not specified Major exclusions: not specified Baseline severity of asthma: not specified Baseline Severity of GOR: ‐ all had symptoms of GOR Baseline Complications of GOR: ‐ not specified | |

| Interventions | H2 antagonist ranitidine 150 mg twice daily Duration of intervention: Four weeks. Antacid allowed as required in both treatment and control groups. No daily dose specified. Identical placebo was used for the control group. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms, PEF and medication use were averaged over the 12 week treatment period. FEV1 and blood studies were undertaken on the last day of each treatment period. Outcomes measured: FEV1, PEF am, PEF pm, asthma symptoms, airway hyperresponsiveness, eosinophils, nocturnal asthma score*, B2 use*. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Ford 1994.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated, method not described Concealment of Allocation: Adequate Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Not Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 11 Number completed: 10 Mean age (range): 63 (50‐80) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: ‐ Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function. Nocturnal attack of asthma. Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: ‐ Symtpoms ‐ all had symptomatic GOR for an average of 52 (7‐99) months. ‐ esophagitis ‐ 24 hr pH monitoring Association between GOR & Asthma tested?: ‐ No H‐Pylori Tested?: ‐ No Other diseases included: not specified Major exclusions: not specified Baseline severity of asthma: ‐ FEV1 not specified ‐ PEF mean overall l/min 253‐300 ‐ Exacerbations not specified Baseline Severity of GOR: ‐ all had symptoms and nocturnal coughing/choking Baseline Complications of GOR: ‐ Barrett's esophagus n=2 ‐ pH score not reported ‐ ulceration grades I n=1;Grade II n= 1; Grade III n=4. ‐ esophageal stricture n=0. | |

| Interventions | Omeprazole 20 mg daily or identical placebo. Duration of intervention: 4 weeks. Antacids as required allowed in both the treatment and control groups. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms, PEF and medication use were averaged over the 4 week treatment periods. Asthma symptoms, PEF, Nocturnal asthma symptoms, Nocturnal B2 use, Day B2 use, Treatment Preference*. | |

| Notes | * indicates significant result. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Goodall 1981.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated, method not described. Concealment of Allocation: Randomisation scheme controlled by pharmacy Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Not Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 20 Number completed: 18 Mean age (range): 54 (30‐65) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Doctor's diagnosis based on 'clinical grounds'. Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: any of symptoms, or abnormal endoscopy, 24 hr pH monitoring, acid‐perfusion or manometry. 19/20 had symptomatic reflux. Association between GOR & Asthma tested? Yes ‐ association found in 10 subjects. H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: not specified Major exclusions: not specified Baseline severity of asthma: nocturnal wheezing present in all subjects Baseline Severity of GOR: ‐ heartburn 19/20 subjects ‐ regurgitation in 12/20 subjects Baseline Complications of GOR: ‐ esophagitis mild n=7/20, marked n=4/20, normal n=9/20. ‐ abnormal pH n=8/18, normal n=10/18 ‐ manometry low pressure n=8/20, normal n‐12/20. | |

| Interventions | H2 antagonist: cimetidine 200 mg three times daily plus cimetidine 400 mg at night. Duration of intervention: 6 weeks. B2 agonists, inhaled corticosteroids or sodium cromoglycate as required were allowed in both the treatment and control phases. Control subjects had an identical placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: asthma symptoms and B2 use were recorded in a diary and averaged over the 6 week treatment period. Lung function and GOR symptoms were measured on entry and after each treatment period. Outcomes measured: Asthma symptoms, FEV1, PEF am, PEF pm,* nocturnal asthma symptoms*, B2 use, GOR symptoms, treatment preference. | |

| Notes | * indicates significant finding. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Gustafsson 1992.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated, method not described. Concealment of Allocation: Adequate Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Not Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 40 Number completed: 37 Mean age (range): 14.2 (10‐20) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Doctor's diagnosis Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Symptoms (11 reported no heartburn and 11 reported no regurgitation ‐ unclear if these were the same 11 subjects or not ‐ the rest had symptomatic GOR), 24 hr pH monitoring, Acid perfusion test. Association between GOR & Asthma tested?H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified Major exclusions: Not specified Baseline severity of asthma: Not specified Baseline Severity of GOR: 26/37 had nocturnal cough/choking Baseline Complications of GOR: Mean (SEM) % of reflux time Group 1: 0.5 (0.1), Group 2: 2.7(0.3). | |

| Interventions | H2 antagonist: ranitidine 150mg or 300 mg nocte (dependent on weight) Duration of intervention: 4 weeks B2 agonists, inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids or sodium cromoglycate were maintained as usual in both the treatment and control phases. Control subjects had an identical placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms, PEF, and medication use were averaged over the 4 week treatment periods. Lung function and bronchial hyperresponsiveness was measured at the end of run‐in, and at the end of each treatment period. Outcomes measured: FEV1, PEF, airway hyperresponsiveness, treatment preference, asthma symptoms*, nocturnal asthma symptoms*. | |

| Notes | * denotes significant finding. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Kiljander 1999.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: drug company was responsible for randomisation Random stated: Method ‐ not described Concealment of Allocation: not described Double‐Blinding: Yes Withdrawals/Dropouts: all subjects accounted for Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 57 Number completed: 52 Mean age (range): 49 (21‐75) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: ATS Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Manometry and 24 hr pH monitoring Association between GOR & Asthma tested? No H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: not stated Major exclusions: Not specified Baseline severity of asthma: FEV1 % predicted mean(range): 81 (31‐114) Baseline Severity of GOR: 35% patients had no symptoms Baseline Complications of GOR: not specified | |

| Interventions | Proton Pump inhibitor: Omeprazole 40mg daily or placebo. Duration: 8 weeks for each treatment period plus 2 week washout period and 1 week run in. Asthma medications maintained throughout study period. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: 3 x weekly dairies at baseline and immediately after both treatment periods (total 19 weeks) Outcomes measured: Asthma symptoms, FEV1, nocturnal symptoms* and gastric symptom score*. | |

| Notes | * indicates significant result. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available (Cochrane Grade B) |

Kjellen 1981.

| Methods | Study Design: Parallel Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated: Method ‐ alternation Concealment of Allocation: Alternation ‐ inadequate Double‐Blinding: Not stated or described Withdrawals/Dropouts: Not described Adverse Events: Not described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 62 Number completed: not reported Mean age (range): 52 (36‐65) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: as per ATS Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Manometry, Acid perfusion test. Symptomatic GOR was not required for entry nor reported. Association between GOR & Asthma tested? No ‐ not required for entry H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified Major exclusions: Not specified Baseline severity of asthma: stated "more severe" p 191. Mean FEV1 pre bronchodilator 2.16 l/min Baseline Severity of GOR: Not stated Baseline Complications of GOR: hiatal hernia 55%; dysmotility 58%, positive acid perfusion test 35% and decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressure 40%. | |

| Interventions | Conservative treatment of GOR including: elevation of head of bed; warm water after meals; avoid food 3 hours before bed time; refrain from aspirin &/or anticholinergic drugs; avoid procedures which raise intra‐abdominal pressure. Control group were informed there was a suspicion of esophageal dysfunction but that results had to be checked in two months time. Both groups kept diaries of asthma drugs. Duration of intervention: 8 weeks Asthma medications were considered optimal at the time of entry into the study. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: a comparison between the first and the third month was made for asthma medications. Patient reported improvement in symptoms was noted at the 2 month follow‐up. Asthma symptoms (number who self‐reported an improvement) dyspnoea, wheeze, cough, expectoration; FEV1; beta‐agonist use;GOR symptoms (number who self‐reported an improvement). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | Investigators aware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade C) |

Larrain 1991.

| Methods | Study Design: Parallel Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Randomised stated. Concealment of Allocation: Adequate ‐ centralised randomisation conducted by Smith Kline in USA. Double‐Blinding: Double blinding for medical treatment only (as surgical treatment would have been obvious) Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 90 Number completed: 81 Mean age (s.d.): 44 (11) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Patient report of wheezing and/or shortness of breath Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Heartburn symptoms (60 had mild symptoms, 21 had no symptoms), endoscopy (all had either a normal oesophagus (n=60) or erythema (n=20) , 30 minute pH monitoring after loading stomach with 300 mls of 0.1N HCl followed by a barium mean if no reflux seen on x‐ray. Temporal Association between GOR & Asthma tested? Unsure H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified Major exclusions: COPD Baseline severity of asthma: 56/81 had reactive airways. 35/81 used corticosteroids Baseline Severity of GOR: 60/81 experienced heartburn. 38/81 had free reflux shown on radiography. Baseline Complications of GOR: 20 had grade 1 erosion, 60 had a normal endoscopy. | |

| Interventions | H2 antagonist: cimetidine 300 mg four times daily or placebo for Duration: 26 weeks OR Surgery: modified posterior gastropexy. Antacids were allowed as required in all groups. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms and lung function were evaluated and recorded monthly. Medication scores were calculated from daily records over the full 6 month period. Outcome measured: Pulmonary symptoms (surgery* & cimetidine*), FEV1 (cimetidine*), asthma medications score, steroid use (surgery*). | |

| Notes | * indicates significant finding in the specified group | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Levin 1998.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: "Random drawing" Concealment of Allocation: "Patients and investigators were blinded to treatment identity until completion of study" Double‐Blinding: Yes Withdrawals/Dropouts: all subjects accounted for Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 11 Number completed: 9 Mean age (range): 35‐72 Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Objective lung ‐ function ‐ >=15% reversibility post B2 and daily asthma medication. Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: symptoms of heartburn or regurgitation at least weekly without therapy. Association between GOR & Asthma tested? No H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Major exclusions: COPD, prior oesophageal surgery, acute PUD, use of omeprazole or URTI within past 30 days and severe medical or surgical illness. Baseline severity of asthma: FEV1 1.9(l/min) 1.0‐2.9 (range) Baseline Severity of GOR: mean % time pH<4 in the proximal oesophagus was 4.5% total, 6.5% upright, 0.6% supine. Baseline Complications of GOR: not specified | |

| Interventions | Proton Pump inhibitor: Omeprazole 20mg daily or placebo. Duration: 8 weeks for each treatment period and 4 week lead‐in time | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: Symptoms of asthma and GER were measured daily for 20 weeks of the study. Quality of life was was measured at the end of the 4 week lead in period and after each 8 week treatment period. Outcomes measured:PEF*, FEV1 and quality of life* | |

| Notes | * indicates significant result. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available (Cochrane Grade B) |

Meier 1994.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Block Random stated, method not described. Concealment of Allocation: Adequate Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 15 Number completed: 15 Mean age (range): 49 (34‐63) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma : ATS / objective lung function Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: included if abnormal endoscopy or abnormal pH on 24 hr monitoring. All had symptoms of pyrosis. Additional investigations included acid‐perfusion test (Bernstein) test, manometry, esophageal motility. Association betwen GOR & Asthma tested? Yes. Association required for entry. Tested by: ‐ history and symptoms ‐ 24 hr pH monitoring H Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified Major exclusions: pregnancy or unwilling to comply with birth contraception requirements, less than 19 years of age or unable to give informed consent. Baseline severity of asthma: ‐ FEV1 >15% response to bronchodilator ‐ PEF > 15% response to bronchodilator Baseline Severity of GOR: 15/15 had GOR symptoms Baseline Complications of GOR: Number per grade of esophageal erosion: ‐ Grade 1 = 1, Grade II = 4, Grade III = 8 Grade IV = 2. ‐ Stricture 8/15 ‐ pH mean for distal probe 60.5 ‐ hiatal hernia 10/15 | |

| Interventions | Proton Pump inhibitor: Omeprazole 20 mg twice daily or placebo. Duration of intervention: 6 weeks (plus a two week washout period) Status quo asthma medications maintained throughout the study. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms and medication use were recorded daily. Lung function tests were conducted at 3,6,8,11,14 and 16. It is not specified which results contributed to the reported results. Outcomes measured: Wheeze or hoarseness, exacerbations, oral corticosteroids, FEV1*, PEF, B2 agonist use. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Nagel 1988.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated, method not described. Concealment of Allocation: Unclear Double‐Blinding: Described and appropriate Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 15 Number completed: 14 Mean age (range): 42 (20‐64) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Symptoms, 24hr pH monitoring‐ required pH < 4 for > 4.2% of the time or > 3 episodes of reflux lasting longer than 5 minutes. Required to have symptomatic GOR at least once every 6 weeks. Association between GOR & Asthma tested? Yes. Association required for entry. ‐ history / symptoms ‐ 24 hr pH monitoring associated with a dip in PEF during the night. H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified. Major exclusions: Not specified Baseline severity of asthma: FEV1 > 25% reversibility after bronchodilators PEF > 25% reversibility after bronchodilators Baseline Severity of GOR: ‐ symptoms occurred at least once every 6 weeks. Baseline Complications of GOR:‐ not specified. | |

| Interventions | H2 antagonist: ranitidine 150mg in the morning and 300mg at night or placebo for Duration: 7 weeks plus a 3 day washout period. Continued usual medications for asthma throughout the study. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: averaged over the 1 week treatment period. Outcomes measured: Asthma score, PEF am, PEF pm, B2 agonist use. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available (Cochrane Grade B) |

Teichtahl 1996.

| Methods | Study Design: Cross‐over Randomised Controlled Trial Randomisation: Random stated ‐ method unclear Concealment of Allocation: Closed envelope technique Double‐Blinding: Yes ‐ double blinded. Withdrawals/Dropouts: Described Adverse Events: Described Statistical Analysis: Described | |

| Participants | Number randomised: 25 Number completed: 20 Mean age (s.d.): 46 (12) Diagnostic Criteria for Asthma: Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function. Also had to have a positive provocation test. Diagnostic Criteria for GOR: Endoscopy and pH < 4 for > 5% of the 24 hr period. 19/20 had symptomatic GOR. The other subject had difficult to control nocturnal asthma. Association between GOR & Asthma tested? No H‐Pylori Tested?: No Other diseases included: Not specified Major exclusions: significant respiratory disease other than asthma, respiratory tract infection in 4 weeks prior to the study, significant systemic, cardiac or hepatic illness; oesophageal varicies; gastric ulcer; pre‐pyloric ulcer; duodenal ulcer or pregnancy. Baseline severity of asthma: ‐ FEV1 15% reversibility within 15 to 30 minutes of B2 agonist AND diurnal variation of PEF of >19% documented in the past 6 months. Baseline Severity of GOR: all had GOR symptoms Baseline Complications of GOR: Number per grade of esophagitis: Grade 0 = 3, grade I = 4; grade II = 11; grade III = 2 pH score ‐ average % of time that pH < 4 = 12.2% | |

| Interventions | Proton pump inhibitor: omeprazole 40mg daily as a morning dose. Duration: 4 weeks plus a 2 week run‐in /washout period. Astemizole or other long acting H1 antagonists were ceased 6 weeks prior to the study. Cholinergic or anticholinergic agents were not permitted during the study. Inhaled B2 agonists allowed as required throughout the study. Theophylline and inhaled and oral corticosteroids remained constant throughout the study. Oral B2 agonists and sodium cromoglycate not allowed during the study. | |

| Outcomes | Duration over which outcomes were measured: symptoms, PEF and medication use were recorded in a daily diary and averaged over the 4 week treatment period. Lung function was measured at the beginning and end of each treatment period. Outcomes measured: Hospitalisations, unscheduled visits to the doctor, Nocturnal asthma, Daytime asthma symptoms, FEV1, PEF am, PEF pm*, FEV1, Use of B2 agonists . | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment (Cochrane Grade A) |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Cloud 1994 | Not asthma |

| Harper 1987 | Not randomised |

| Hubert 1988 | Not reflux treatment |

| Langer 1993 | Not asthma |

| Laursen 1995 | Not asthma |

| Poder 1997 | Not randomised, not controlled |

| Singh 1983 | Not reflux treatment. |

| Spechler 1992 | Subjects did not have asthma |

| Spechler 1995 | Subjects did not have asthma |

| Tashkin 1982 | Not Gastro‐oesophageal Reflux |

Contributions of authors

Gibson PG ‐ instigation of review, intellectual direction and guidance, inclusion/exclusion, data extraction, re‐writing, editing, analysis and interpretation. Coughlan JL ‐ inclusion/exclusion, data extraction, first draft writing, data input, analysis and interpretation. Henry RL ‐ inclusion/exclusion, data extraction, writing and interpretation.

Sources of support

Internal sources

John Hunter Hospital, Newcastle, Australia.

The University of Newcastle, Australia.

NHS Research and Development, UK.

External sources

NSW Department of Health, Australia.

National Asthma Campaign, Australia.

Garfield Weston Foundation, UK.

Declarations of interest

NIL

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Boeree 1998 {published data only}

- Boeree MJ, Peters FTM, Postma DS, Kleibeuker JH. No effects of high‐dose omeprazole in patients with severe airway hyperresponsiveness and (a)symptomatic gastro‐oesophageal reflux. European Respiratory Journal 1998;11:1070‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ekstrom 1989 {published data only}

- Ekstrom T, Lindgren BR, Tibbling L. Effects of ranitidine treatment on patients with asthma and a history of gastroesophageal reflux: a double blind crossover study. Thorax 1989;44:12‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ford 1994 {published data only}

- Ford GA, Oliver PS, Prior JS, Butland RJ, Wilkinson SP. Omeprazole in the treatment of asthmatics with nocturnal symptoms and gastro‐oesophageal reflux: a placebo‐controlled cross‐over study. Postgraduate Medical Journal 1994;70:350‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goodall 1981 {published data only}

- Goodall RJ, Earis JE, Cooper DN, Bernstein A, Temple JG. Relationship between asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux. Thorax 1981;36(2):116‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gustafsson 1992 {published data only}

- Gustafsson PM, Kjellerman NI, Tibbling L. A trial of ranitidine in asthmatic children and adolescents with or without pathological gastro‐oesophageal reflux. European Respiratory Journal 1992;5:201‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kiljander 1999 {published data only}

- Kiljander T, Salomaa E‐R, Hietanen E, Helenius H, Liippo K, Terho EO. Asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux: can the reponse to anti‐reflux therapy be predicted?. Respiratory Medicine 2001;95:387‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiljander TO, Salomaa ERM, Hietanen EK, Terho EO. Gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatics. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled crossover study with omeprazole. Chest 1999;116:1257‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjellen 1981 {published data only}

- Kjellen G, Tibbling L, Wranne B. Effect of conservative treatment of oesophageal dysfunction on bronchial asthma. European Journal of Respiratory Diseases 1981;62:190‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Larrain 1991 {published data only}

- Larrain A, Carrasco E, Galleguillos F, Sepulveda R, Pope CE II. Medical and surgical treatment of non‐allergic asthma associated with gastroesophageal reflux. Chest 1991;99(6):1330‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrain A, Carrasco J, Galleguillos J, Pope CE II. Reflux treatment improves lung function in patients with intrinsic asthma. Gastroenterology 1981;80(5 Part 2):1204. [Google Scholar]

Levin 1998 {published data only}

- Levin TR, Sperling RM, McQuaid KR. Omeprazole improves peak expiratory flow rate and quality of life in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1998;93:1060‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meier 1994 {published data only}

- Meier JH, McNally PR, Punja M, Freeman SR, Sudduth RH, Stocker N, et al. Does omeprazole (Prilosec) improve respiratory function in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux?. Disgestive Diseases and Sciences 1994;39(10):2127‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nagel 1988 {published data only}

- Nagel RA, Brown P, Perks WH, Wilson RSE, Kerr GD. Ambulatory pH monitoring of gastro‐esophageal reflux in 'morning dipper' asthmatics. British Medical Journal 1988;297:1371‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Teichtahl 1996 {published data only}

- Teichtahl H, Kronborg IJ, Yeomans ND, Robinson P. Adult asthma and gastro‐oesophageal reflux: the effects of omperazole therapy on asthma. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine 1996;26:671‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Cloud 1994 {published data only}

- Cloud ML, Offen WW, Hill, et al. Nizatidine versus placebo in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease: a 6‐week, multicentre, randomised, double‐blind comparison. British Journal of Clinical Practice Supplement 1994;48:11‐19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harper 1987 {published data only}

- Harper PC, Bergner A, Kaye MD. Antireflux treatment for asthma. Archives of Internal Medicine 1987;147:56‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hubert 1988 {published data only}

- Hubert D, Gaudric M, Guerre J, Lockhart A, Marsac J. Effect of theophylline on gastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 1988;81:1168‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Langer 1993 {published data only}

- Langer JC, Winthrop AL, Issenman RM. The single‐subject randomised trial ‐ A useful clinical tool for assessing therapeutic efficacy in pediatric practice. Clinical Pediatrics 1993:654‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laursen 1995 {published data only}

- Laursen LS, Haveund T, Bondesen S, Hansen J, Sanchez G, Sebelin E, et al. [Omeprazole int he long‐term treatment of gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease. A double‐blind randomised dose‐finding study]. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1995;30(9):839‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poder 1997 {published data only}

- Poder G, Bokay J, Parrak Z, Kelemen J. Occurence of gastro‐esophageal reflux and the efficiency of antireflux treatment in reactive airway diseases of children. Clinical Investigation ‐ Mon Sci Monit, 1997;3(4):485‐8. [Google Scholar]

Singh 1983 {published data only}

- Sing V, Jain NK. Asthma as a cause for, rather than a result of gastro‐oesophageal reflux. Journal of Asthma 1983;20(4):241‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spechler 1992 {published data only}

- Spechler SJ and the Dept of Veterans Affairs Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease in veterans. The New England Journal of Medicine 1992;326:786‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Spechler 1995 {published data only}

- Spechler SJ, Gordon DW, Cohen J, Williford WO, Krol W, and the Dept of Beterans Affairs Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group. The effects of antireflux therapy on pulmonary function in patients with sever gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 1995;90(6):915‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tashkin 1982 {published data only}

- Tashkin DP, Ungerer R, Wolfe R, Mendoza G, Calvarese B. Effect of orally administered cimetidine on histamine‐ and antigen‐induced bronchospasm in subjects with asthma. American Review of Respiratory Disease 1982;125:691‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Andze 1991

- Andze G, Brandt M, St‐Vil D, Bensoussan A, Blanchard H. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in 500 children with respiratory symptoms: value of pH monitoring. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 1991;26(3):295‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Choy 1997

- Choy D, Leung R. Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Respirology 1997;2:163‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Field 1998

- Field SK, Sutherland LR. Does medical therapy improve asthma in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review of the literature. Chest 1998;114:275‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Field 1999

- Field SK, Gelfand GAJ, McFadden SD. The effects of antireflux surgery on asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux. Chest 1999;116:766‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harding 1986

- Harding S, Richter J, Guzzo M, Schan C, Alexander R, Bradley L. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux: acid suppressive therapy improves asthma outcome. American Journal of Medicine 1986;100(4):395‐405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnson 1974

- Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Twenty‐four hour pH monitoring of the distal oesophagus: A quantitative measure of gastroesophageal reflux. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1974;62:325‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnsson 1987

- Johnsson F, Joelsson B, Isberg P‐E. Ambulatory 24 hour intraesophageal pH‐monitoring in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut 1987;28:1145‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kahrilas 1996

- Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. JAMA 1996;276(12):983‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klotz 1971

- Klotz SD, Moeller RK. Hiatal hernia and intractable bronchial asthma. Annals of Allergy 1971;29:325‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mansfield 1989

- Mansfield, IE. Gastro‐oesophageal reflux and respiratory disorders: a review. Annals of Allergy 1989;62:158‐63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martin 1982

- Martin ME, Grunstein MM, Larsen GL. The relationship of gastroesophageal reflux to nocturnal wheezing in children with asthma. Annals of Allergy 1982;49:318‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mays 1976

- Mays EE. Intrinsic asthma in adults: association with gastroesophageal reflux. JAMA 1976;236:2626‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moher 1995

- Moher D, Jada AR, Nichol G, Penman M, Tugwell P, Walsh S. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: An annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clinical Trials 1995;16:62‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simpson 1995

- Simpson WG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and asthma. Archives of Internal Medicine 1995;155:798‐803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sontag 1990

- Sontag SJ, O'Connell S, Khandelwal S, Miller T, Nemchausky B, Schnell TG, et al. Most asthmatics have gastroesophageal reflux with or without bronchodilator therapy. Alimentary Tract 1990;99:613‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tucci 1993

- Tucci F, Resti M, Fontana R, Novembre E, Lami CA, Vierucci A. Gastroesophageal reflux and bronchial asthma: prevalence and effect of cisapride therapy. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 1993;17(3):265‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tuchman 1984

- Tuchman DN, Boyle JT, Pack IA. Comparison of airway responses following tracheal or oesophageal acidification in the cat. Gastroenterology 1984;87:872‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Winter 1997

- Winter DC, Brennan NJ, O'Sullivan G. Reflux induced respiratory disorders (RIRD). Journal of the Irish Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons 1997;26(3):202‐10. [Google Scholar]