Abstract

Background:

During the transition between prison and community, people are at greatly increased risk for adverse health outcomes. This study describes a peer health mentoring program that supports women in the first 3 days after their release from a provincial correctional facility in British Columbia.

Methods:

We used a participatory health research framework to develop multimethod processes to describe the Unlocking the Gates Peer Health Mentoring Program. Mentors are women with incarceration experience. Between 2013 and 2018, women released from Alouette Correctional Centre for Women were invited to access the program. All program clients were invited to participate in the surveys and interviews. We analyzed survey and interview data using descriptive analysis for quantitative data and content analysis for qualitative data.

Results:

There were 346 program contacts from 340 women over the study period. For every contact, a telephone interview was conducted. Among the 346 contacts, 173 women met their mentor, of whom 172 (99.4%) completed the intake and consent forms. A total of 105 women (61.0%) completed a program activity feedback survey at the end of the mentoring period. Women identified a range of needed supports during the transition from prison to community, including access to clothing, social assistance, housing and health care. Participants described a mix of emotions surrounding release, including excitement, anxiety, hope, and a wish for understanding and support. Within 3 days of release, 49 participants (46.7%) had accessed a family physician, and 89 (84.8%) had accessed at least 1 community resource. Ninety-eight participants (93.3%) reported that their mentor assisted them in accessing community resources.

Interpretation:

Peer health mentoring provides valuable, multifaceted support in helping women to navigate health and social services and to meet their basic needs. Strengthening health supports during the transition from prison to community is critical to promoting the health and well-being of women leaving prison.

On any given day, about 40 000 adults are imprisoned in Canadian correctional facilities.1 In Canada, the vast majority of people return to the community after weeks rather than years in prison.1 During the transition between prison and community, people are at greatly increased risk for poor health outcomes, harm and death.2,3 Many who experience incarceration have histories of unstable housing, low educational attainment, financial insecurity and childhood trauma.4–6 On release, people often lack financial resources and adequate housing.7 People who experience incarceration have a high burden of health conditions including mental health issues, substance use, and acute and chronic physical health conditions.8,9 Immediately after release, people face multiple challenges, which may make it difficult to prioritize health.10 Compounding this, people with a history of incarceration may experience barriers to accessing health care, including discrimination owing to their criminal justice involvement.7,11 Ensuring adequate support during this transition is critical from both health and justice perspectives, as medical comorbidities and poor health are linked with relapse to substance use7 and recidivism.5

Peers trained as health mentors can provide important social and navigational support during this transition. In this paper, we define peers as people with lived experience of incarceration. Peers can act as role models and inspire hope.12,13 Peers are uniquely positioned to develop empathetic, nondirective relationships and to support people to trust and engage with services.12 Among people with substance use disorder, there is evidence that peer support can increase engagement with treatment, reduce relapse rates, improve relationships with providers and enhance treatment experience.13 Peer support is also a fundamental component of trauma-informed care.14

The purpose of this study was to describe the Unlocking the Gates Peer Health Mentoring Program,15 which supports women in the first 3 days after release from prison. The study’s objectives were to report on 1) self-reported demographic characteristics of women who participated in the program, 2) unmet needs that affect health and well-being, as identified by women being released, 3) women’s experience of release and 4) the program activities.

Methods

Setting

The Alouette Correctional Centre for Women is a multilevel security prison in Maple Ridge, British Columbia. It has 192 cells16 and is the main provincial custodial centre for women. The length of stay averages 3 months (range a few days to 24 mo). The Unlocking the Gates program is ongoing. We report on data collected from the program’s start, in March 2013, to July 2018 inclusive.

Intervention

During a previous community-based participatory health research study,17 incarcerated women proposed a peer health mentoring program to support women to achieve their health goals during the days immediately after release, when women report feeling most vulnerable and are most at risk for adverse health outcomes.2,3,18,19 We implemented this idea by training and employing women with incarceration experience as peer health mentors. Mentor training included San’yas Indigenous cultural safety training,20 trauma-informed practice,21 research ethics,22 effective boundaries and respectful communication (delivered by a trained facilitator) and naloxone training.23 As of July 2018, 10 peer health mentors had been trained. Each evening, the program manager, who also has lived experience of incarceration, checks in with peer health mentors to ensure the safety of clients and mentors.

Incarcerated women are made aware of the program by personalized letters sent by the program team and by posters and flyers in prison living units. Since June 1, 2013, the program team has written a letter to every woman identified on Court Services Online as having received a custodial sentence, inviting her to access the program (https://justice.gov.bc.ca/cso/esearch/criminal/partySearch.do). While incarcerated, women who wish to participate can telephone the program office at no charge or approach a specific staff member within the prison to facilitate referral. At release, women are met by a mentor, who provides a wide range of supports and mentorship depending on the priorities each woman identifies. Women are matched to a mentor by mentor availability and by the geographic destination of the client. Supports include arranging housing or medical appointments, taking women to access clothing or food, and accompanying women to obtain social assistance. Although the formal period of mentorship ends after 3 days, mentors report that they often stay in contact with participants to provide ongoing support.

Research design

Participatory health research engages participants in research processes, thereby creating research that informs or creates social action to improve the quality of people’s lives and communities.24 The Unlocking the Gate program team (composed of women who had experienced incarceration and academics) used a participatory framework to create a multimethod process to compile descriptive data, including designing 2 surveys and a telephone interview script. Formerly incarcerated women participated in designing and implementing the survey tools, applying for research ethics board review, collecting data, assisting with data analysis, and interpreting and disseminating study findings.

Data collection

Data collection included needs assessments and program activity feedback. Needs assessment occurred at 2 time points during the program:

While incarcerated: women’s first contact with the program occurred when they telephoned the program office. A telephone interview was conducted with the use of closed- and open-ended scripted questions (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/1/E1/suppl/DC1), and responses were recorded for program use. For this study, we conducted secondary analysis of program data collected from telephone interviews.

When released: participants met their mentor and completed a release intake form (Appendix 1). Starting in July 2016, a demographic survey was added to this intake (Appendix 1). Depending on participant preference, the woman completed the forms herself, or the mentor read the questions to the participant and recorded answers on the forms.

Participant feedback about the program activities was collected at the end of the 3-day mentoring period. Participants completed the program activity feedback survey (Appendix 1) and were provided an addressed, stamped envelope to mail it to the program office.

Analysis

Each participant was given a unique study identifier. Data were deidentified and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. We analyzed quantitative data using descriptive statistics. Open-ended questions from the intake and feedback surveys were examined by means of content analysis (conducted by K.E.M., verified by R.E.M., M.K., P.Y.); major categories were clustered and then illuminative quotes identified.

To check findings, women with incarceration experience were invited to review the manuscript through a closed peer-support Facebook group with over 200 members. In addition, 4 coauthors are women who have experienced incarceration and are members of the program team.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board. Amendments were obtained for study modifications that emerged through iterative participatory processes and for secondary use of data from program telephone interviews.

Results

Participants

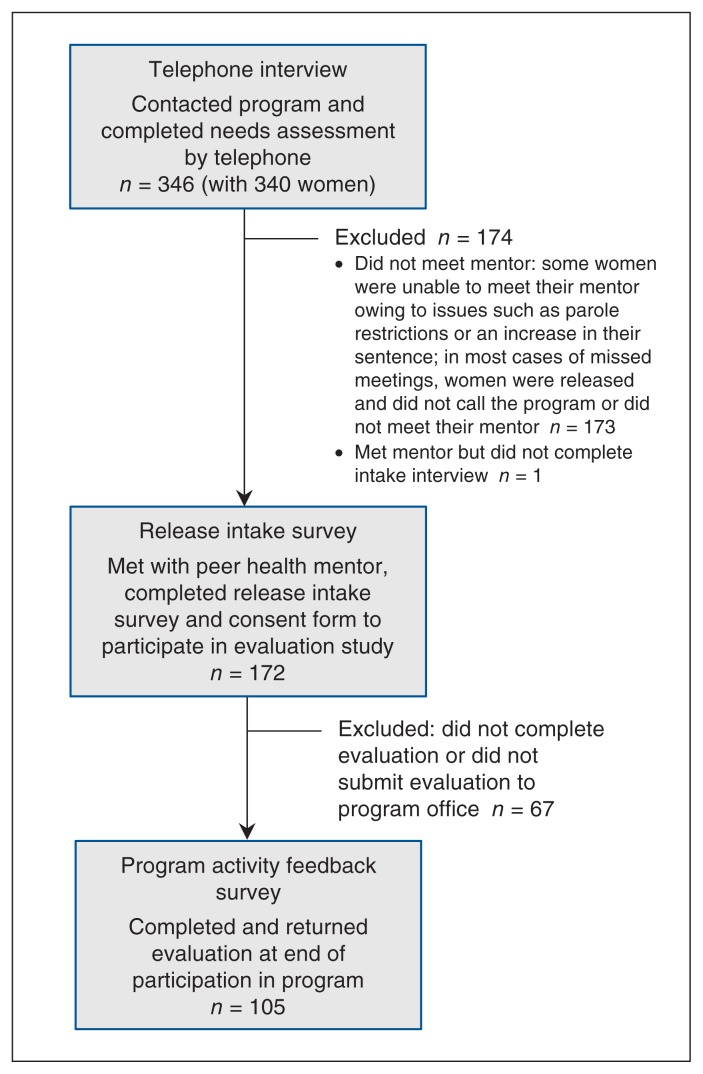

Between March 2013 and July 2018, there were 346 program contacts from 340 women (Figure 1). For every contact, a telephone interview was conducted for program use. Among the 346 contacts, 173 women met their mentor, of whom 172 (99.4%) completed the intake and consent forms. A total of 105 women (61.0%) completed a program activity feedback survey at the end of the 3-day mentoring period.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram showing participants from whom data were collected.

At intake, 92 participants (53.5%) identified themselves as Indigenous women (Table 1). Of the 66 women who completed the demographic survey, 43 (65%) were aged 31–50 years, 10 (15%) identified as LGBTQ2+, 46 (70%) were single, never married, and 34 (52%) had attained grade 10 or lower as their highest level of education. At the time of intake, 16/66 women (24%) were homeless, and 57 (86%) were accessing social assistance or disability. Fifty-three women (80%) had children, and 46 (70%) had at least 1 child less than age 18 years. For 5 women (8%) it was their first time in custody, and 54 women (82%) were on probation at the time of intake. Twenty-nine women (44%) were aged 18 or less at the time of their first incarceration. The median time served for the most recent incarceration was 45 days.

Table 1:

Self-reported demographic characteristics of women who participated in a peer health mentoring program for up to 3 days after their release from a correctional centre in British Columbia

| Characteristic | No. (%) of women |

|---|---|

| Self-identified Indigenous identity (n = 172) | |

| Indigenous | 92 (54) |

| First Nations | 71 (41) |

| Métis | 16 (9) |

| Inuit | 4 (2) |

| Don’t know | 1 (1) |

| Not Indigenous | 77 (44) |

| Don’t know | 2 (1) |

| Missing data | 1 (1) |

| Demographic data (n = 66)* | |

| Age, yr | |

| 16–30 | 19 (29) |

| 31–50 | 43 (65) |

| 51–70 | 2 (3) |

| Missing data | 2 (3) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight/heterosexual | 54 (82) |

| LGBTQ2+ | 10 (15) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 1 (2) |

| Divorced | 2 (3) |

| Common-law | 6 (9) |

| Single, never married | 46 (70) |

| Widowed | 5 (8) |

| Separated | 6 (9) |

| Highest educational attainment | |

| Grade 8 or lower | 7 (11) |

| Grade 9–10 | 26 (39) |

| Grade 11–13 | 17 (26) |

| Some postsecondary | 12 (18) |

| Don’t know/prefer not to say/missing | 4 (6) |

| Homeless at time of intake interview | 16 (24) |

| Source of support† | |

| Accessing social assistance/disability at time of intake interview | 57 (86) |

| Wages and salaries | 1 (2) |

| Under the table income | 1 (2) |

| Nonlegitimate source of income | 1 (2) |

| Parental support | 1 (2) |

| Other | 3 (4) |

| Don’t know | 3 (4) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2) |

| Have children | 53 (80) |

| Children < 18 yr | 46 (70) |

| Incarceration history (n = 66) | |

| Age at first conviction, yr | |

| ≤ 18 | 29 (44) |

| 19–30 | 23 (35) |

| 31–50 | 7 (11) |

| Missing data | 7 (11) |

| Type of offence on record | |

| Violence | 27 (41) |

| Property | 40 (61) |

| Drugs | 22 (33) |

| Administrative | 18 (27) |

| Time served (most recent incarceration), d | |

| Average | 115 |

| Median | 45 |

| Range | 0–1095 |

| First time in custody‡ | 5 (8) |

| On parole at time of intake | 4 (6) |

| On probation at time of intake | 54 (82) |

| No. of years incarcerated over lifetime | |

| < 1 | 20 (30) |

| 1–2 | 20 (30) |

| 2–5 | 16 (24) |

| 5–10 | 6 (9) |

| 10–15 | 2 (3) |

| 15–20 | 2 (3) |

Collection of demographic data began in July 2016; therefore, demographic data are not available for women who participated from March 2013 to June 2016 inclusive.

Respondents could select more than 1 answer. One woman reported being employed at the time of intake.

Among the 61 women who reported that it was not their first time in custody, responses regarding how many times they had previously been in custody included “too many to count,” “lots,” “many,” “countless” and “don’t know.”

The number of times in provincial custody ranged from 2 to 50 (average 6.7, median 4.5). Seven women reported having been previously incarcerated in a federal facility.

Identified needs

Women leaving prison were returning to communities across BC (Table 2). This made navigating travel home an immediate need for most women. At the time of their telephone interview, 36/346 women (10.4%) were unsure where they would go when released.

Table 2:

Region in British Columbia that incarcerated women reported to be going to after their release from a provincial correctional facility during telephone interview

| Region | No. (%) of women n = 346 |

|---|---|

| Vancouver Island/coast | 49 (14.2) |

| Lower Mainland/Southwest* | 166 (48.0) |

| Thompson-Okanagan | 76 (22.0) |

| Kootenay | 2 (0.6) |

| Cariboo | 7 (2.0) |

| Northeast | 1 (0.3) |

| Out of province | 2 (0.6) |

| Unsure† | 36 (10.4) |

| Answer missing | 7 (2.0) |

Region where the Alouette Correctional Centre for Women is located.

Includes women who reported they were unsure of where they would go and those who reported more than 1 possible destination.

Women identified their priorities twice, first in the telephone interview (n = 346) and again in the in-person intake survey after their release (n = 172). A majority of women (≥ 57%) identified clothing and social assistance as needs at both times (Table 3). Housing was identified as a need by 178 women (51.4%) during the telephone interview and 60 women (37.3%) on the intake form. An immediate need for health care was identified by 52 women (15.0%) in the telephone interview and 48 women (29.8%) in the intake survey. Needs identified in the telephone interview were similar for women who went on to participate in the program and those who did not (Table 4).

Table 3:

Needs most commonly identified by women during telephone interview before release from provincial correctional facility and during intake interview on/after their release

| Need* | No. (%) of women | |

|---|---|---|

| Telephone interview n = 346 |

Intake interview n = 161† |

|

| Clothing | 217 (62.7) | 92 (57.1) |

| Social assistance | 209 (60.4) | 112 (69.6) |

| Housing | 178 (51.4) | 60 (37.3) |

| Probation | 109 (31.5) | 1 (0.6) |

| Drug and alcohol counsellor | 95 (27.4) | 44 (27.3) |

| Outreach worker‡ | 87 (25.1) | 40 (24.8) |

| Narcotics Anonymous/ Alcoholics Anonymous meeting times | 63 (18.2) | 25 (15.5) |

| Health care | 52 (15.0) | 48 (29.8) |

Participants could select more than 1 need. Other needs identified included access to a dentist, food, a safe ride home or to other transportation, help with court, family services, access to grief counselling, support to stop shoplifting, treatment programs, mental health services and help with bail supervision.

Answer missing for 11 women.

Outreach workers are employed by community organizations to support people who are street involved or have unstable housing to meet their needs such as getting health care or connecting to housing.

Table 4:

Needs most commonly identified during the telephone interview by women who participated in the program and those who did not meet their mentor after release

| Need* | No. (%) of women | |

|---|---|---|

| Participated in program n = 174 |

Did not meet mentor n = 172 |

|

| Clothing | 102 (58.6) | 115 (66.9) |

| Social assistance | 102 (58.6) | 107 (62.2) |

| Housing | 73 (42.0) | 102 (59.3) |

| Probation | 51 (29.3) | 59 (34.3) |

| Drug and alcohol counsellor | 48 (27.6) | 47 (27.3) |

| Outreach worker | 44 (25.3) | 43 (25.0) |

| Narcotics Anonymous/ Alcoholics Anonymous meeting times | 35 (20.1) | 33 (19.2) |

| Health care | 34 (19.5) | 27 (15.7) |

Participants could select more than 1 need. Other needs identified included access to a dentist, food, a safe ride home or to other transportation, help with court, family services, access to grief counselling, support to stop shoplifting, treatment programs, mental health services and help with bail supervision.

During intake, women were asked to identify resources they felt could have helped them before release. Responses were received from 108 women and included more contact with the community, more access to a telephone, more release planning support, having social assistance set up, having safe housing lined up, more connections with alcohol and drug counsellors, and recovery houses or treatment centres. Although this study does not report on the content of telephone calls, program records indicate that mentors provided advice about health care and community resources to women in prison, to assist them in addressing their health and social goals related to their pending discharge.

To understand more about women’s needs and the contexts of their lives, during the program activity feedback survey (n = 105), participants were asked to respond to a series of questions adapted from the Difference Game25 by agreeing or disagreeing with statements starting with “It would make a difference in my life if I had … .” The most commonly identified factors were money to buy necessities (91 [86.7%]), someone to talk to about the things that worried them (90 [85.7%]), housing (89 [84.8%]), medical care (89 [84.8%]) and a real friend (89 [84.8%]) (Table 5).

Table 5:

Responses to the item “It would make a difference in my life if I had …”

| Response | No. (%) of women n = 105 |

|---|---|

| Money to buy necessities | 91 (86.7) |

| Someone to talk to about the things that worry me | 90 (85.7) |

| Housing | 89 (84.8) |

| Medical care | 89 (84.8) |

| A real friend | 89 (84.8) |

| Dependable transportation | 84 (80.0) |

| Someone to hassle with agencies when I can’t | 83 (79.0) |

| More education | 82 (78.1) |

| Healthy food to eat | 81 (77.1) |

| Drug or alcohol treatment | 79 (75.2) |

| A good job | 79 (75.2) |

| More control of my life | 78 (74.3) |

| Personal safety | 78 (74.3) |

| Enough clothes | 77 (73.3) |

| Food | 76 (72.4) |

| Freedom from abuse | 72 (68.6) |

| Time for fun | 71 (67.6) |

| Somewhere else to live | 67 (63.8) |

| A good partner | 65 (61.9) |

| A dependable relationship | 64 (61.0) |

| Legal help | 63 (60.0) |

| Someone to lend me money | 63 (60.0) |

| A telephone or access to a telephone | 62 (59.0) |

| Help with child custody problem | 61 (58.1) |

| Time to get enough sleep | 58 (55.2) |

| Time to be by myself | 58 (55.2) |

| Birth control | 46 (43.8) |

Experience of release

At intake, women were asked what they would like people to know about women being released from prison. Illustrative quotes are provided in Table 6. Several women wrote about greater understanding and the difficulties of release. Others wanted people to know about the need for greater support during transition back to community.

Table 6:

Illustrative quotes from narrative comments provided by women during their intake interview

| Item | Illustrative quote* |

|---|---|

| What would you like people to know that would be helpful for women being released? | |

| Greater understanding and difficulties of release | We’re human and we all make mistakes, and addiction is very powerful. (QOJ) There is hope for everyone. (BGG) It’s overwhelming. (TJE) We are struggling, so be patient. (TYI) |

| Need for greater support | We need help, not to just throw us into society. (TVF) We don’t get much support, so if someone can help us we would really appreciate it. (UOE) |

| Write a little bit about how you’re feeling right now | |

| Excitement, especially related to family; happy and hopeful | I feel motivated and blessed to have another chance to be successful and a great mother. (NJA) I’m happy and glad to have a new start in life. (UNH) Like I’m being honoured in my head. (KUC) |

| Anxiety and fear about uncertainty | Having a lot of stress not knowing what to expect. (IOD) Scared, don’t want to go back to the streets. (MFD) |

| Mix of emotions | Overwhelmed, anxious, wanting to use, hopeful and excited. (DYF) Full of anxiety, unsure of the future but hopeful. (OUH) A little scared but confident I will succeed. (TYJ) I am between anxiety attacks and feeling happy to have support and someone who is there for me. (CRH) |

Three-letter identifiers were assigned to participants.

Women were also asked to share how they were feeling. Some expressed excitement, especially related to their families, and that they were happy and hopeful for a fresh start. Some women expressed anxiety and fear about the uncertainty of release. Many women expressed a mix of emotions (Table 6).

Program activities

Within 3 days after release, 89/105 participants (84.8%) connected with at least 1 community resource, and nearly half (49 [46.7%]) accessed a family doctor (answer missing for 4 participants). Of the 52 who did not access a family doctor, 31 (55.4%) reported that their mentor provided information about accessing a family doctor. A majority of women (66 [62.8%]) required access to income assistance, and, of these women, 55 (83.3%) reported that their mentor accompanied them to obtain it. Ninety-eight participants (93.3%) reported that their mentor assisted them in accessing community resources, and 94 (89.5%) reported that their mentor helped them to achieve the goals they had identified for themselves before release.

The program feedback activity survey invited narrative comments. Most women wrote about how they saw importance and value in the support of their peer health mentor (Box 1).

Box 1: Representative quotes from the program feedback survey*.

Peer health mentors are a huge help. They understand what you’ve been through and how you want to be free of it. (NJA)

I am so grateful to have [peer health mentor] here with me today, otherwise I would [have] probably used. (TOD)

I am happy with everything and very grateful for this program. If it wasn’t for your program, I would have given up on trying. (CPC)

Three-letter identifiers were assigned to participants.

Interpretation

This study describes the short-term multifaceted benefits to having the support of a peer health mentor during the transition from prison. We found that peer health mentoring provided valuable, multifaceted support that helped women to navigate health and social services, as well as meet their basic needs, after release from prison. Nearly half (47%) of women accessed a family physician within 72 hours of their release. A recent study in BC showed that people are more likely to be refused by a family physician if they disclose a history of incarceration.11 In addition, women incarcerated in Ontario identified health literacy and knowledge of services as barriers to accessing health care inside prison and in the community.26 A peer health mentor may help to navigate services and to identify specific services and practitioners who will not discriminate.

Housing is a key determinant of health27,28 and an essential resource for addressing other needs such as employment and health care services. Finding secure housing is also one of the most challenging barriers that people face in reentry into community following prison release.29 In the present study, 80% of participants had children, and most had children less than age 18 years. This highlights the need for family-based programming and supports, as well as collaboration among ministries responsible for corrections, health, and child and family services during incarceration and following release.

The distance to home was a huge challenge faced by women leaving prison in the current study. Forty percent of women were returning to communities outside the region where the prison is located. The geographical separation of women from their communities is also a barrier to maintaining family connections and relationships throughout incarceration. This separation contravenes international recommendations for smaller, local custodial units for women in the criminal justice system.30

When asked what would make a difference in their lives, women most identified needs related to money, social connection, housing and health care. This reflects the disproportionate experience of inadequate social supports and services among people who experience incarceration. Also, 44% of participants reported that it would make a difference in their life if they had access to birth control. This finding is consistent with a study in Ontario in which 80% of incarcerated women reported an unmet need for contraception before their admission to a correctional facility, and 38% expected this as an unmet need after release.31

The positive experiences expressed by our participants are reflective of the impact of peer support described in other studies. In a US randomized controlled trial, people leaving prison who were connected with a transition health team that included a peer mentor had reduced use of emergency departments32 compared to another accessible clinic. In BC, the Provincial Health Services Authority, which has been responsible for health care in provincial correctional facilities since October 2017, is piloting community transition teams that include peers.

Although only 4.9% of the Canadian population identify as Indigenous,33 in provincial and territorial facilities, 28% of incarcerated men are Indigenous, and 43% of incarcerated women are Indigenous.1 Fifty-four percent of participants in the current study were Indigenous women, whereas the proportion of the BC population who are Indigenous is 5.9%.34 There is an urgent need to address the systemic criminalization of Indigenous people and to provide culturally safe and trauma-informed approaches to address the ongoing legacy of colonization, including the Sixties Scoop and the residential school system.35 Future work in the Unlocking the Gate program will seek to increase ways in which supports may be grounded in Indigenous culture and ways of knowing.

Limitations

Tailoring supports to each woman’s expressed needs means that consistency of mentorship is difficult to assess. However, daily check-ins with the program manager and field notes submitted by peer health mentors about their work show that mentors provide a wide variety of supports to address specific needs of individual clients, consistent with the program’s aims and values. Half of women who contacted the office while incarcerated did not meet their mentor. Future research should seek to understand why women may not access peer mentorship and identify alternative supports that may be offered. Women provided feedback about the program after 3 days of mentorship. This short window limits our ability to understand the lasting impact of peer mentorship following release. Future research should evaluate the impact of peer health mentoring on the long-term achievement of health goals and on the potential to support women to break the cycle of reincarceration.

Conclusion

Peer mentoring provided valuable and multifaceted support to women during the transition from prison to community. Strengthening supports during this transition is important to increase access to health care and social services, and to mitigate the risk of morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge that the study and program were conducted across the unceded traditional territories of 198 First Nations. They acknowledge women with incarceration experience who envisioned and imagined the Unlocking the Gates Peer Health Mentoring program, those with the commitment and leadership needed to develop and implement the program, and those who participated as clients and who contributed their voice to this study. The authors honour and mourn the women who have died as a result of the tragic opioid overdose epidemic that has swept across British Columbia. The authors dedicate this article to the memory of Dr. Carl Leggo (1953–2019), coauthor, colleague and friend.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Ruth Elwood Martin reports grants from the First Nations Health Authority during the conduct of the study. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Mo Korchinski, Pamela Young, Ruth Elwood Martin, Vivian Ramsden, Alison Granger-Brown, Lynn Fels, Patricia Janssen, Marla Buchanan, Lara-Lisa Condello, Christine Hemingway and Tammy Milkovich conceived the study. Marla Buchanan, Jane Buxton, Lara-Lisa Condello, Patricia Janssen, Mo Korchinski, Vivian Ramsden, Pam Young, Christine Hemingway, Katherine McLeod and Ruth Elwood Martin designed the study. Katherine McLeod analyzed the data, overseen by Ruth Elwood Martin, Mo Korchinski and Pamela Young. Katherine McLeod and Ruth Elwood Martin drafted the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to data interpretation, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This project received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Knowledge Translation) (2011), the Koerner Foundation (2012), the Interior Health Authority (2012), the Provincial Health Services Authority (2012), Mary Pence (2014), the First Nations Health Authority (2015, 2018) and private donors (2017, 2018, 2019).

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/1/E1/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Malakieh J. Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2016/2017. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2018. [accessed 2019 Mar 28]. [corrected 2018 June 29]. Cat no 85002-X. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2018001/article/54972-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groot E, Kouyoumdjian FG, Kiefer L, et al. Drug toxicity deaths after release from incarceration in Ontario, 2006–2013: review of coroner’s cases. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, et al. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart LA, Nolan A, Thompson J, et al. Social determinants of health among Canadian inmates. Int J Prison Health. 2018;14:4–15. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-08-2016-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen PA, Korchinski M, Desmarais SL, et al. Factors that support successful transition to the community among women leaving prison in British Columbia: a prospective cohort study using participatory action research. CMAJ Open. 2017;5:E717–23. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bodkin C, Pivnick L, Bondy SJ, et al. History of childhood abuse in populations incarcerated in Canada: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:e1–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouyoumdjian F, Schuler A, Matheson FI, et al. Health status of prisoners in Canada: narrative review. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:215–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:912–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong KR, Must A, Tang AM, et al. Competing priorities that rival health in adults on probation in Rhode Island: substance use recovery, employment, housing, and food intake. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:289–99. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahmy N, Kouyoumdjian FG, Berkowitz J, et al. Access to primary care for persons recently released from prison. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:549–51. doi: 10.1370/afm.2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrenger SL. Enacting lived experiences: peer specialists with criminal justice histories. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2019;42:9–16. doi: 10.1037/prj0000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reif S, Braude L, Lyman DR, et al. Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65:853–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhri S, Zweig KC, Hebbar P, et al. Trauma-informed care: a strategy to improve primary healthcare engagement for persons with criminal justice system involvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:1048–52. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4783-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin RE, Korchinski M, Fels L, et al., editors. Releasing hope: women’s stories of transition from prison to community. Toronto: INANNA Publications and Education; 2019. pp. 134–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellringer C. An audit of the Adult Custody Division’s correctional facilities and programs. Victoria: Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia; 2015. [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: https://www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/2015/special/report/AGBCCorrections report FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin RE, Murphy K, Chan R, et al. Primary health care: applying the principles within a community-based participatory health research project that began in a Canadian women’s prison. Glob Health Promot. 2009;16:43–53. doi: 10.1177/1757975909348114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binswanger IA, Stern M, Deyo R, et al. Release from prison — a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borschmann R, Kinner S, Spittal M. The Mortality After Release from Incarceration Consortium (MARIC) study: strengths of international data linkage. Int J Pop Data Sci. 2018:3. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v3i4.908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.San’yas Indigenous cultural safety training. Vancouver: Provincial Health Services Authority; [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: www.sanyas.ca/training/british-columbia/core-ics-foundations. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trauma informed care e-Learning modules. Edmonton: Alberta Health Services; [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/page15526.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 22.TCPS 2: CORE — tutorial. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2) Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2018. [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: https://tcps2core.ca/welcome. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naloxone training online. BC Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions; 2018. [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: https://www.stopoverdose.gov.bc.ca/theweekly/naloxone-training-online. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macaulay AC, Commanda LE, Freeman WL, et al. Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. BMJ. 1999;319:774–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grant T, Ernst CC, McAuliff S, et al. The Difference Game: facilitating change in high-risk clients. Fam Soc. 1997;78:429–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed R, Angel C, Martel R, et al. Access to healthcare services during incarceration among female inmates. Int J Prison Health. 2016;12:204–15. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-04-2016-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guirguis-Younger M, McNeil R, Hwang SW. Homelessness & health in Canada. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee BA, Tyler KA, Wright JD. The new homelessness revisited. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:501–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geller A, Curtis MA. A sort of homecoming: incarceration and the housing security of urban men. Soc Sci Res. 2011;40:1196–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corston J. The Corston report: a review of women with particular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system. London (UK): 2007. [accessed 2019 Oct 28]. Available: www.justice.gov.uk/publications/docs/corston-report-march-2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liauw J, Foran J, Dineley B, et al. The unmet contraceptive need of incarcerated women in Ontario. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:820–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, et al. Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:e22–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aboriginal peoples in Canada: key results from the 2016 census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [accessed 2019 May 12]. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Data products, 2016 census. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [accessed 2019 Dec 3]. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Cat no 98-404-X2016001. Available: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-PR-Eng.cfm?TOPIC=9&LANG=Eng&GK=PR&GC=59. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in Aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005 Mar-Apr;96(Suppl 2):S45–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03403702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.