ABSTRACT

A cancer-promoting role of fibrogenesis in the liver has long been speculated; however, the molecular mechanisms regarding this phenomenon are largely unknown. We demonstrated in our previous study that macrophage-derived S100A4 promotes liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells; however, whether and how S100A4 directly contributes to the development of fibrosis-associated liver cancer remains elusive. High expression of S100A4 in the fibrotic region was observed in human liver tumor tissues which associated with advanced disease severity. Through an established hepatocarcinogenesis model involving apparent liver fibrogenesis, we found that S100A4-deficient mice developed significantly less and smaller liver tumor nodules, with no change in the liver inflammation but decreased liver fibrosis and expression of stem cell markers in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues. Mechanistically, S100A4 directly promoted stem cell-associated genes signatures in a way synergistic with its interacting protein, extracellular matrix component collagen I. This process is dependent on the receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and β-catenin signaling. Furthermore, the liver tumor sphere formation in vitro and tumor growth in vivo were greatly enhanced only when the cancer cells were pretreated with both S100A4 and collagen I. Our work firstly demonstrated a key role of S100A4 in synergy with extracellular matrix in the promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by affecting the stemness of cancer cells.

KEYWORDS: S100A4, collagen I, hepatocellular carcinogenesis, fibrosis, stemness

Introduction

Liver cancer was the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide in 2018, with approximately 841,000 new cases and 782,000 deaths annually.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most prevalent primary liver cancer, accounting for 80-90% of cases, and usually arises after years of liver disease.1 Approximately 90% of HCCs develop due to underlying chronic liver inflammation, the induction of fibrosis and/or subsequent cirrhosis caused by hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, high alcohol consumption or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2,3 As a result of the wound healing process in response to hepatic injury of various causes and manifested by deposits of extracellular matrix synthesized by activated stellate cells, the risk for HCC in patients with fibrotic disease is greatly enhanced.4-7 The presence of fibrosis has been speculated to increase the stromal stiffness,8,9 potentially activate integrin signaling pathways and promote the crosstalk of intercellular networks between tumors and hepatic stromal cells, negatively modulating immune responses, inducing cancer-prone chronic inflammation, and leading to tumorigenesis or aberrant cancer growth.10-13 Although several genes/signaling pathways have been implicated in the development of HCC, the molecular mechanisms underlying fibrosis-related liver cancer pathogenesis are still poorly understood.

S100A4 is a member of the S100 calcium-binding protein family that was originally cloned as a fibroblast specific protein (FSP1).14 It was further identified as a molecule associated with tumor metastasis (metastasin, or mts-1) that acted by promoting the motility and invasion of tumor cells.15 Moreover, S100A4 interacts with p53, annexin II,16 receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE),17 heparan sulfate proteoglycans and cytoskeletal proteins, and these interactions have been shown to enhance apoptosis, cell motility and angiogenesis.18 Interestingly, a recent finding indicated that S100A4 cells constitute an inflammatory subpopulation of macrophages in the liver;19 however, the function of S100A4 in liver biology is still unclear.

High expression levels of S100A4 are associated with a poor prognosis in several human cancers including breast cancer,20 colorectal cancer,21 and HCC.22 In prior studies, we also showed that S100A4+ cells promoted tumor development and chronic inflammation in different pathological process.24–27 Given the importance of S100A4 in both tumor biology and fibrogenesis, we evaluated whether S100A4 contributes to fibrosis-related liver carcinogenesis. Using a DEN/CCl4-induced fibrosis-related HCC mouse model, we found a critical role of S100A4 in orchestrating liver cancer development. Thus, S100A4 may represent an important pathway that triggers liver fibrogenesis-cancer stemness-carcinogenesis trilogy.

Results

Expression of S100A4 in liver cancer associated with fibrotic lesions

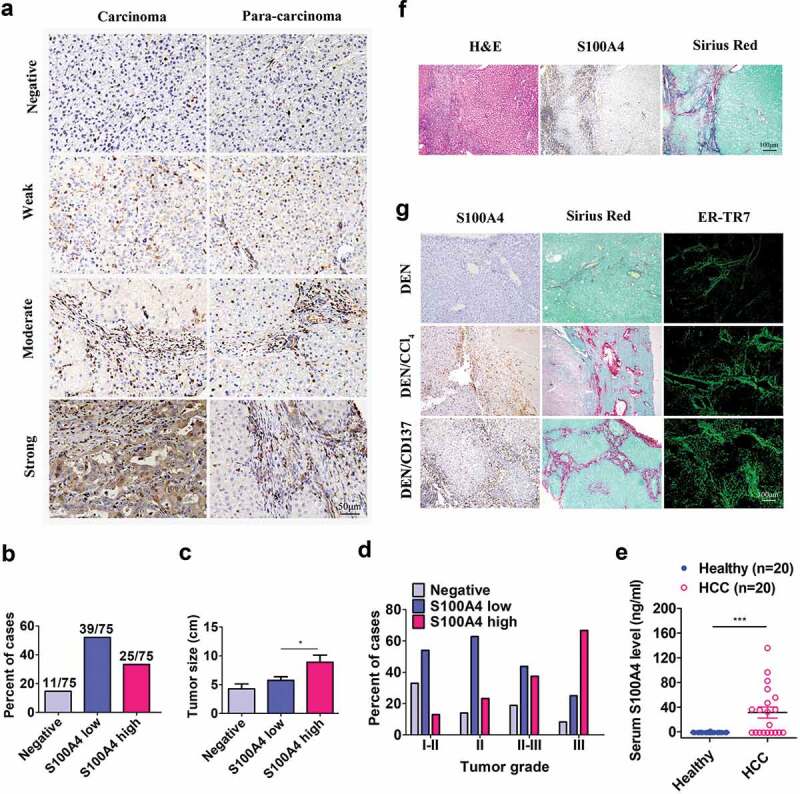

To identify the relationship between S100A4 expression and HCC progression, we profiled tumor tissues and adjacent paracarcinoma tissues from 75 HCC patients. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that S100A4 expression was significantly upregulated in HCC samples compared to the paracarcinoma tissues. As shown in Figure 1(a), S100A4 expression was observed in the cytoplasm or a combination of the nucleus and cytoplasm in HCC tumor tissues by stromal-like cells.

Figure 1.

S100A4 expression is associated with fibrosis-related HCC. (a) Immunohistochemical staining of S100A4 in 75 HCC tissues and 75 adjacent cancer-free tissues in a tissue array was performed. (a) Representative S100A4 staining is shown. (b) Percentage of the cases expressing S100A4 in carcinoma tissues. (c) Average tumor size in HCC patients with different S100A4 protein levels. * P < .05. (d) Percentage of tissues with negative, low and high S100A4 expression with different tumor grades. (e) Serum S100A4 levels in healthy donors (n = 20) and HCC patients (n = 20) were detected by ELISA. *** P < .001. (f) Immunohistochemical staining including H&E, S100A4 and Sirius Red staining of adjacent tissue sections of human HCC tissues. (g) S100A4 expression in mouse models of HCC. Adjacent sections of HCC tissues were stained for S100A4, Sirius Red and ER-TR7 in C57BL/6 mice treated with DEN for 8 months, C57BL/6 mice treated with DEN and CCl4 for 8 months, and C57BL/6 mice treated with DEN and anti-CD137 agonist antibody (2A) for 8 months. Scale bar, 100 μm.

By leveraging the different expression densities of S100A4 in this cohort of HCC tumor tissues (Figure 1(a)), we found that approximately 17.7% cases were negative for S100A4, and 52% and 33.3% cases had either low or high expression, respectively (Figure 1(b)). Furthermore, patients with high S100A4 expression had significantly larger tumor sizes (P = .015) (Figure 1(c)), and there was a positive trend in the percentage of patients with high S100A4 expression and advanced tumor grades (P < .001) (Figure 1(d)). Serum S100A4 levels in HCC patients were also significantly higher than those in healthy donors (P = .041) (Figure 1(e)). As most human HCC was associated with liver fibrosis, interestingly, we found that most S100A4+ cells were accumulated around Sirius Red-positive fibrotic areas in HCC tissues (Figure 1(F)).

Then we took advantage of several recently established mouse models of HCC involving liver fibrogenesis.27 DEN/CCl428 and DEN/2A (one anti-CD137 agonist antibody)24,29 models were fibrosis-related HCC models, but DEN induced HCC model30 was not closely related with fibrosis. Consistent with the observations in HCC patients, the expression of S100A4 was also found in these fibrosis-related HCC models. As shown in Figure 1(g), high expression of S100A4 was found in DEN/CCl4 and DEN/2A fibrosis-related HCC models. However, fibrosis rarely accompanied with DEN-induced HCC tissues and the expression of S100A4 was very low. Altogether, our data suggest that S100A4 may play a significant role during the development of HCC that is associated with a fibrotic microenvironment.

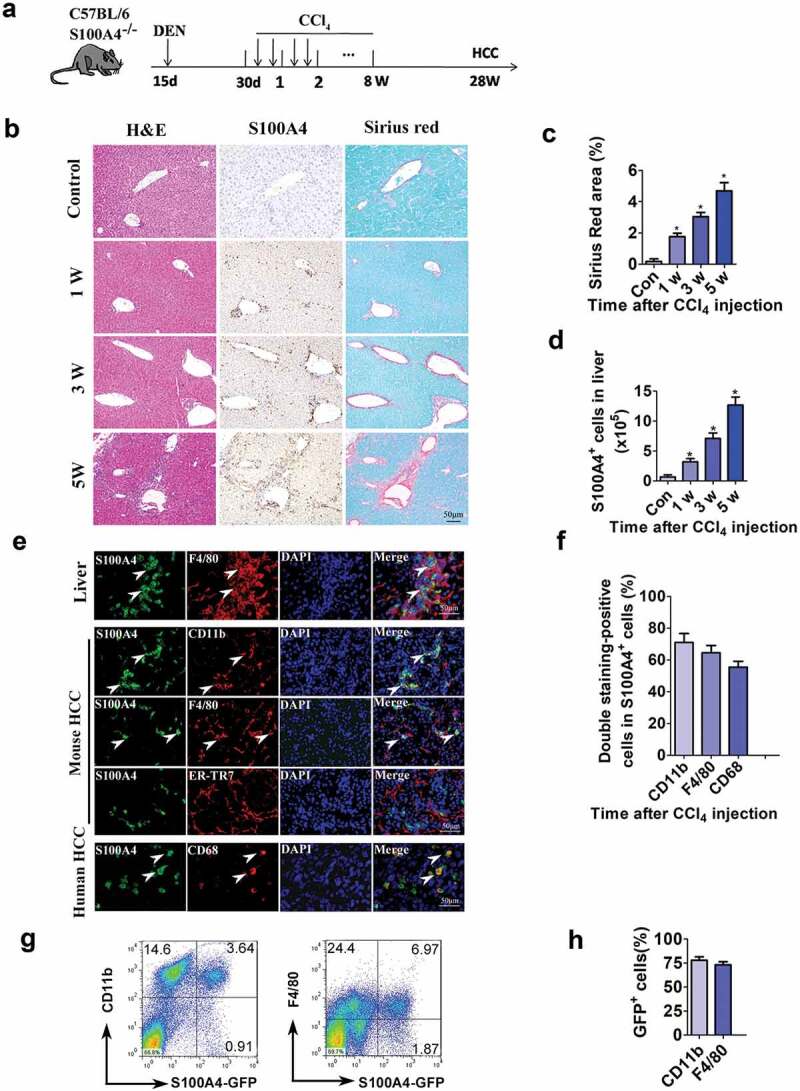

S100A4+ cells accumulate during the development of HCC, and they are a subpopulation of macrophages

We intended to further investigate the kinetics of S100A4+ cells during the development of fibrosis-related HCC. We then select the DEN/CCl4 model to study the role of S100A4 in HCC development. C57BL/6 mice were as Figure2(a) showed, tissue sections were evaluated for S100A4 staining and Sirius Red staining for collagen deposition. As shown in Figure 2(b), only a few S100A4+ cells could be detected in untreated liver tissues; however, the number of S100A4+ cells were increased significantly after DEN/CCl4 treatment, similar to how there was increased collagen deposition in the liver sections (Figure 2(b,c)). We also confirmed the expression of S100A4 by using S100A4+/+ GFP transgenic mice.31 The number of GFP+ (S100A4+) cells in liver tissues were significantly increased after CCl4 application at different timepoints and correlated very well with the percentage of Sirius Red-positive areas (Figure 2(c,d)).

Figure 2.

S100A4+ cells accumulate during the development of HCC, and they are a subpopulation of macrophages. (a) Schematic representation of the DEN/CCl4-induced liver fibrosis-related HCC experiment. Groups of mice (3/group) were left untreated (control) or were treated i.p. with a single injection of 50 μg/g of DEN at 15 days old and were treated with CCl4 twice weekly for 8 weeks 1 month later. Liver tissues were harvested at the indicated timepoints after the final injection. (b) Histological characterization of liver fibrosis and S100A4+ cell accumulation. Adjacent sections were stained with H&E, anti-S100A4 and Sirius Red. Representative images are shown for untreated control and CCl4-treated mice at each time point. Scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Quantification of areas stained with Sirius Red. Statistical analysis was performed between the control and CCl4-treated groups (n = 3). Results represent three independent experiments; mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice per group. * P < .05. (d) S100A4+/+ GFP transgenic mice were administered DEN/CCl4 as described above. Total cell numbers of GFP+ cells in the liver (calculated by multiplying the absolute liver nonparenchymal cell number by the percentage of GFP+ cells) of untreated (control) and CCl4-treated mice at each time point are shown. * P < .05. (e) Double staining for S100A4 (green) and F4/80, CD11b and CD68 (red) in liver, mouse HCC and human HCC tissues. Typical double staining positive cells were indicated by arrows. Scale bar, 50 μm. (f) Percentages of double staining positive S100A4+ cells in HCC tissues. (g-h) Flow cytometry analysis of the phenotypes of S100A4+ cells in the liver of S100A4+/+GFP mice treated with CCl4 by staining GFP+ cells with CD11b and F4/80 antibodies. (g) Representative images of three independent experiments showed S100A4+ cells in the liver of CCl4 treatment. (h) Statistic analysis of CD11b+S100A4+ or F4/80+S100A4+ cells in S100A4+ (GFP+ cells) cells.

Christoph H. Österreichera et al. demonstrated that S100A4+ cells in livers were an inflammatory subpopulation of macrophages in the liver.19 In our previous studies, we also reported that both CCl4 and DEN/CD137 induced S100A4+ cells in livers were main macrophages.24,32 In this study, we found most of the S100A4+ cells in both mouse liver fibrotic tissues and mouse liver tumor tissues, as well as in human HCC tissues were also expressed macrophage markers CD11b, F4/80 or CD68 by immunofluorescent double staining (Figure 2(e,f)). To further confirm the phenotypes of liver-infiltrating S100A4+ cells, we also isolated the liver nonparenchymal cells, performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) staining of these cells, and we found that, among the S100A4-GFP+ cells, about 78.84% were CD11b+ and about 73.07% were F4/80+ (Figure 2(g,h)), further confirmed the macrophage-associated origin of S100A4+ cells.

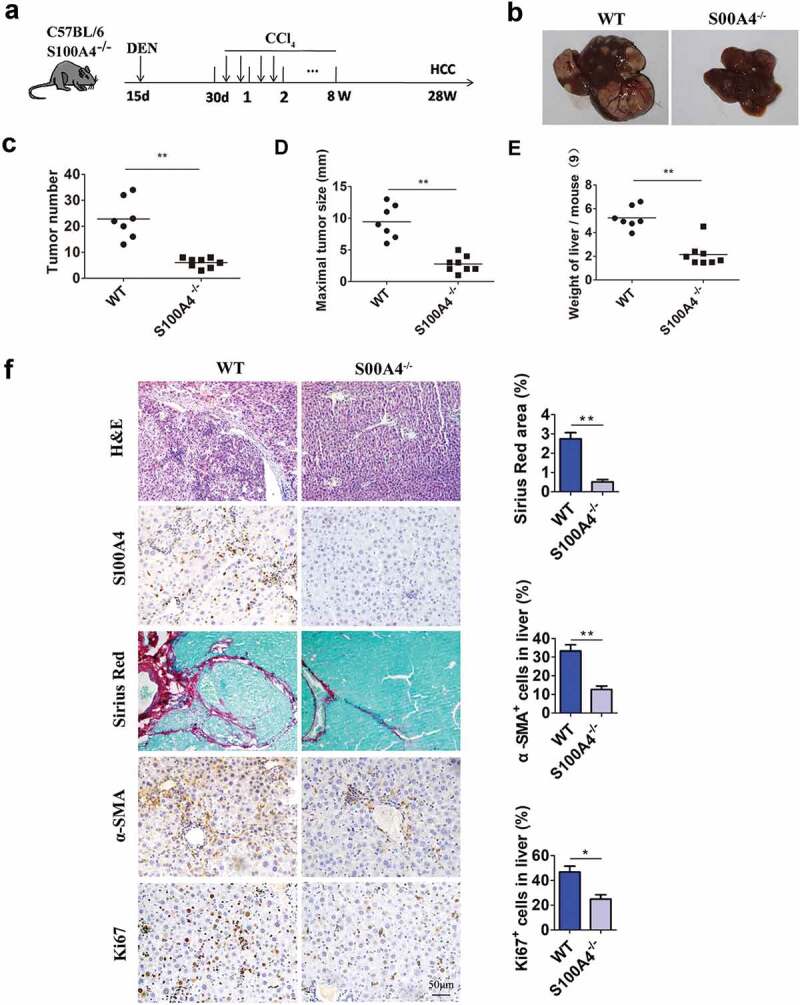

S100A4 deficiency attenuates liver fibrosis and prevents hepatocarcinogenesis

To explore the role of S100A4 in fibrosis-related liver carcinogenesis, S100A4-deficient mice (S100A4−-/-)33 and WT control littermates were given a single intraperitoneal injection of DEN, followed by CCl4 treatment twice a week for 8 weeks; liver tumorigenesis was monitored at 32 weeks (Figure 3(a)). All WT littermates developed liver tumors within 32 weeks, however, S100A4−/- mice showed obvious resistance to liver cancer development. S100A4 deficiency significantly decreased the number of HCC tumors detectable at 32 weeks after DEN administration (22.9 ± 2.93 vs 6 ± 0.65, P < .001) (Figure 3(b,c)), the maximal tumor diameters (9.4 ± 0.99 mm vs. 2.8 ± 0.45 mm, P < .001) and liver weights (5.2 ± 0.35 vs. 2.2 ± 0.36, P < .001) were also notably smaller in S100A4−/- mice than in WT littermates (Figure 3(d,e)). Pathologic analysis further confirmed the different tumor sizes in S100A4−/- mice compared to WT littermates (Figure 3(f)), and S100A4 deficiency led to impaired accumulation of fibrosis in the liver, as measured by Sirius Red and α-SMA staining (Figure 3(f)). A decrease in the percentages of Ki67+ cells in the liver was also found in S100A4−/- mice (Figure 3(f)). Therefore, our data suggest a critical role of S100A4 in promoting both liver fibrosis and liver cancer pathogenesis.

Figure 3.

S100A4 deficiency attenuates liver fibrosis and DEN/CCl4-induced carcinogenesis. (a) Schematic illustration of the DEN/CCl4-induced HCC model. Fifteen-day-old WT littermates and S100A4−/- mice (n = 8) were treated i.p. with a single injection of 50 μg/g DEN and 1 month later were treated with CCl4 twice weekly for 2 months. All mice were euthanized 8 months after DEN treatment for further analysis. (b) Representative photographs of the livers from the animals in each group at 8 months of age. (c-e) The tumor number, maximal tumor size and weight of liver are shown. *** P < .001. (f) Liver sections of HCC were stained with H&E, S100A4, Sirius red and α-SMA. Scale bar, 100 μm. * P < .05, ** P < .01.

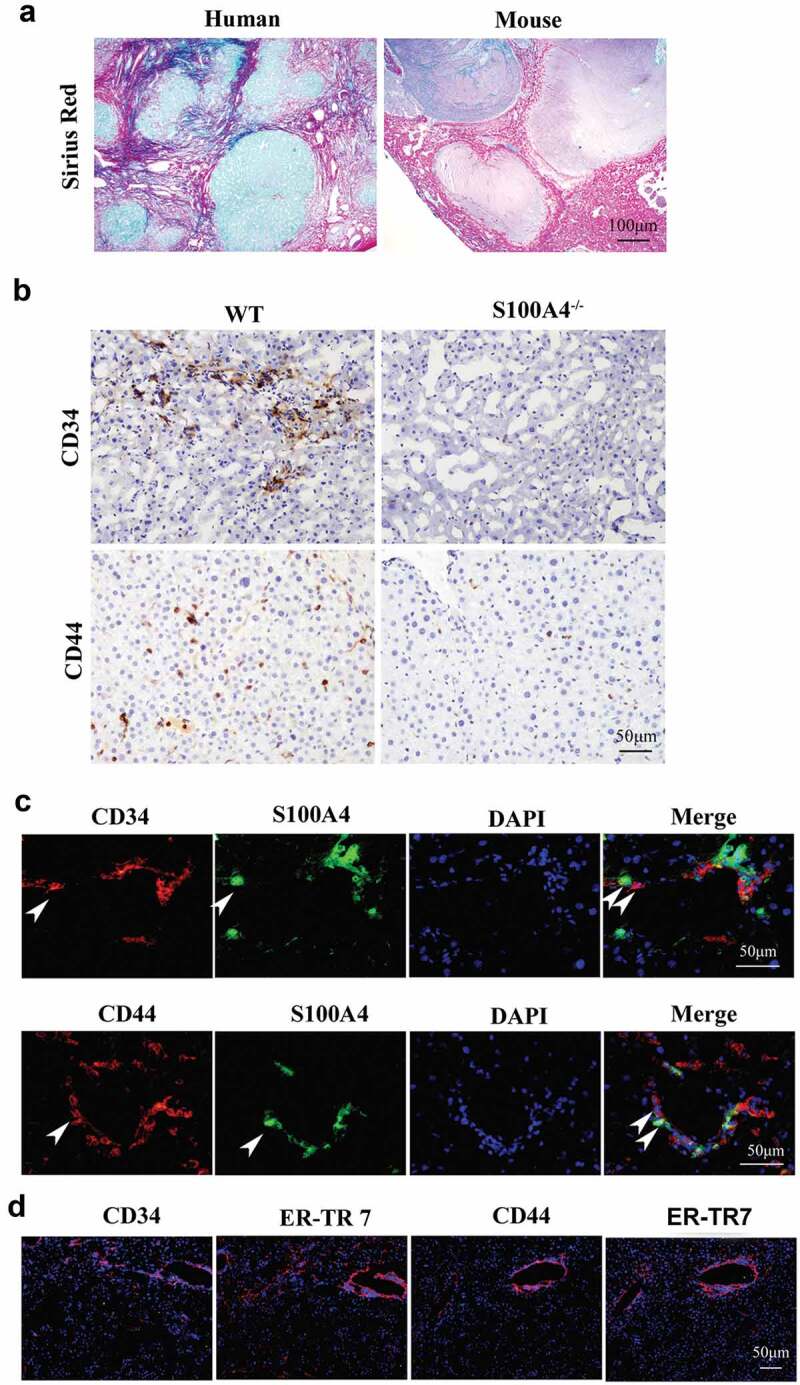

HCC tends to be located in fibrotic livers and to express high levels of stem cell markers

Chronic inflammation of the liver has been linked to both liver fibrosis and liver cancers.34,35 We evaluated liver inflammatory responses at different timepoints in our study. However, in the DEN/CCl4 model, both innate and adaptive immune subsets in the liver remained unchanged after S100A4 depletion (Fig. S1). Thus, we reasoned that the effect of S100A4 in the liver might not occur through altering inflammation but potentially through other mechanisms.

Similar to previous reports, we found that the majority of the local tumors were surrounded by liver fibrotic lesions both in human and mouse HCC tissues (Figure 4(a)), emphasizing a potential contribution of a fibrotic liver environment to cancer development. By profiling cancer-related markers in the liver tumors by immunohistochemical staining, we found that the expression of stem cell markers CD44 and CD34 in fibrosis adjacent HCC tissues of WT littermates was dramatically higher than that in tissues from S100A4−/- mice (Figure 4(b)). Further immunofluorescence staining of HCC tissues from WT littermates showed that the expression of CD44 and CD34 was correlated with S100A4 (Figure 4(c)), which was near the area of fibrosis as indicated by ER-TR7 staining (Figure 4(d)). The results suggest that the effect of S100A4 in the liver might occur by affecting tumor stem cells.

Figure 4.

Higher expression of stem cell markers in HCC is associated with liver fibrosis. (a) Representative images of Sirius Red staining of human and mouse HCC tissues. (b) DEN/CCl4-induced HCC sections from WT littermates and S100A4−/- mice were stained with CD34 and CD44. Scale bar, 100 μm. (c) Double staining for CD34/CD44 (red) and S100A4 (green). DEN/CCl4-induced HCC tissues were harvested and stained with anti-CD34/CD44 and anti-S100A4. White arrows indicate the adjacent CD44/CD34+ cells and S100A4+ cells. Scale bar, 50 μm. (d) Staining for CD34/CD44 and ER-TR7. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Upregulation of stem cell-associated genes in huh-7 cells cultured in collagen Ⅰ medium with S100A4

We further tested the target cells that S100A4 works on within the liver. Interestingly, we found exogenous recombinant S100A4 could be sequestered in the fibrous extracellular matrix of cirrhotic liver. When sections were pre-incubated with recombinant S100A4 protein, this protein was exclusively localized in the fibrous extracellular matrix of the fibrotic septa as indicated by immunostaining (Fig. S2). Whereas no such staining was observed on sections that was preincubated with PBS (Fig. S2). This result indicates that S100A4 might interact with fibrotic lesions that may potentiate the liver pathogenesis.

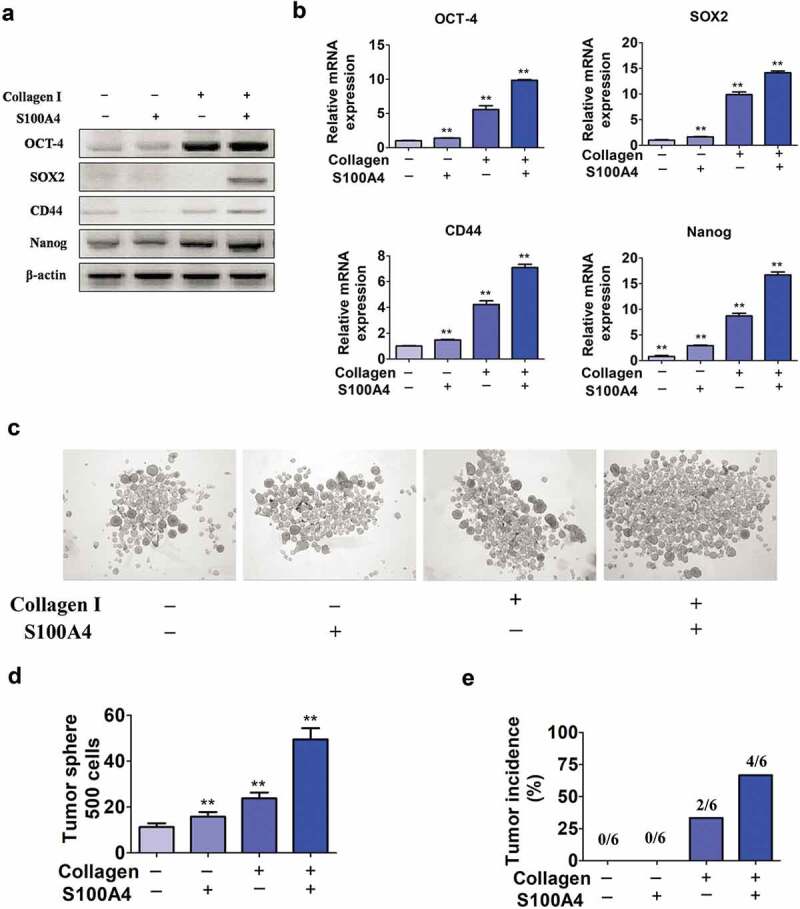

Stem cell activation plays key roles in carcinogenesis in multiple tumor types, including in liver cancers.36,37 To further test our hypothesis, we performed in vitro hepatoma culture experiments. We precoated the tissue culture plate with collagen I as it is the major component of the extracellular matrix of liver fibrotic lesions,38 and later placed Huh-7 cells. S100A4 recombinant protein was further added to the culture medium for 12 hrs. By using RT-PCR or real-time PCR, we found a panel of stem cell markers OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog were significantly upregulated upon stimulation with collagen (Figure 5(a,b)).

Figure 5.

Upregulation of stem cell-associated genes in Huh-7 cells cultured in collagen I medium with S100A4. (a) Stem cell marker expression in Huh-7 cells. Huh-7 cells were cultured in collagen I medium or without collagen I medium and incubated with or without S100A4 (200 ng/ml) for 5 days; then, cell mRNA was extracted and used for the detection of OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog mRNA expression by RT-PCR. Three independent experiments showed similar results. (b) Stem cell markers expression in Huh-7 cells was quantified by real-time PCR. Cells treated as described above were collected and analyzed for the expression of OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog by real-time PCR. ** P < .01. (c-d) Huh-7 tumor spheroid formation after 3 days in culture treatment with collagen I and S100A4. ** P < .01. (e) Tumorigenicity of collagen I and S100A4-cultured Huh-7 cells in nude mice. Cells were treated as described above for 5 days. They were then subcutaneously injected into nude mice with 5 × 105, and tumor formation was observed as described in methods.

Further we performed a sphere formation assay to determine the in vitro self-renewal ability of these cells. Huh-7 cells cultured with both collagen I and S100A4 displayed much better sphere-forming features (Figure 5(c,d)), thus, in sphere-forming experiment, collagen I plus S100A4 given together elicited a strong synergistic effect. In addition, we found that cells stimulated with collagen plus S100A4 grew rapidly in vivo, 4 of 6 mice formed palpable tumors by 15 days. In contrast, other groups, subcutaneously injecting of Huh-7 cells cultured with S100A4 only or without S100A4 and collagen I stimulation, did not elicit obvious tumor formation (0/6), and only 2 of 6 mice formed tumor with collagen I only treatment (Figure 5(e)). Thus, our data suggest that S100A4 could promote stem cell features and the tumorigenic capacity of liver cancer cells in the presence of collagen I.

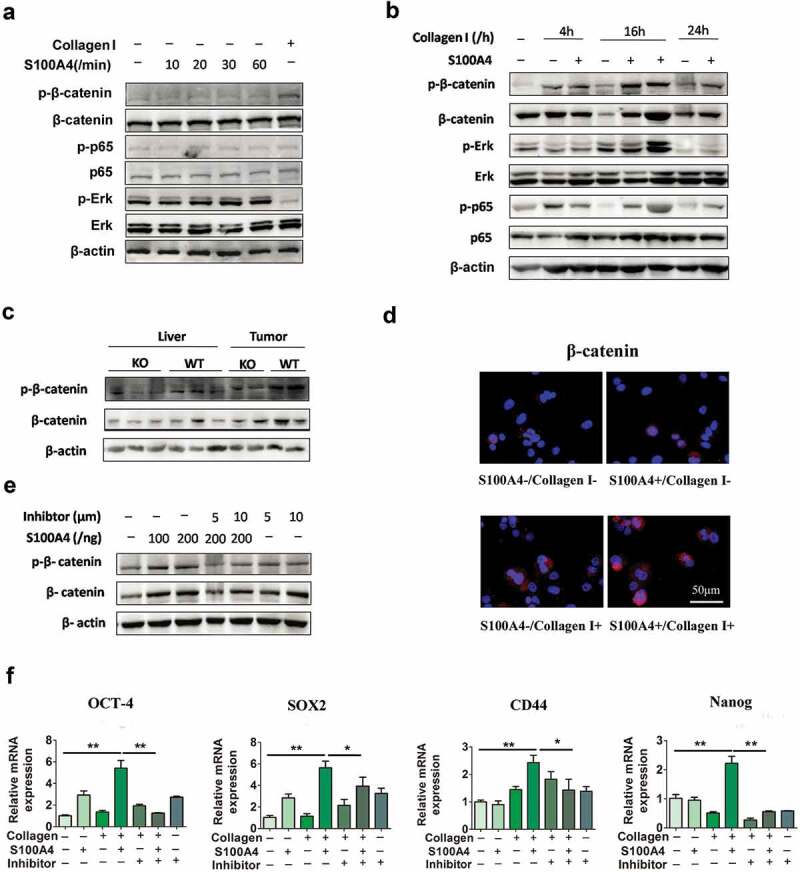

S100A4 upregulates stem cell-associated genes in collagen Ⅰ-cultured huh-7 cells through β-catenin signaling

To identify the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of extracellular S100A4 and collagen I on the induction of stem cell-associated genes, Huh-7 cells were cultured with different stimuli as indicated previously. After treatment with S100A4 at various timepoints (Figure 6(a)), we found that both the overall protein and phosphorylation levels of β-catenin, Erk, and p65 were unaffected. However, when cells were pretreated with collagen I, the addition of S100A4 resulted in upregulation of these three signal pathways when compared with control group (Figure 6(b)).

Figure 6.

S100A4 upregulates stem cell-associated genes in collagen I-cultured Huh-7 cells through β-catenin signaling. (a) Levels of p-p65, p-Erk and p-β-catenin in Huh-7 cells were determined by western blot analysis. Huh-7 cells were cultured without collagen I and incubated with or without S100A4 (200 ng/ml) as indicated. (b) Levels of p-p65, p-Erk and p-β-catenin in Huh-7 cells were upregulated upon administration of collagen I and S100A4, determined by western blot. Huh-7 cells were cultured with collagen I and incubated with or without S100A4 (200 ng/ml) as indicated. (c) Western blot analysis of protein levels of p-β-catenin in DEN/CCl4-treated liver tissues and tumor tissues from S100A4−/- and WT littermates. (d) Sections of β-catenin expression was detected upon S100A4 and collagen I administration by immunofluorescence, representative images were shown. (e) Levels of p-β-catenin in Huh-7 cells were determined by western blot analysis. Huh-7 cells were cultured with collagen I and incubated with S100A4 (200 ng/ml) or a β-catenin inhibitor for 12 h. (f) Expression of OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog in Huh-7 cells by real-time PCR. The upregulated effect of S100A4 was abolished upon administration of β-catenin inhibitors. *P < .05, ** P < .01.

β-catenin signaling plays a pivotal role in regulating cancer stem cells.39 In previous study, we demonstrated that S100A4 promoted lung tumor development through β-catenin pathway-mediated autophagy inhibition.25 We were interested in whether β-catenin signaling was regulated by S100A4 in HCC development. Importantly, the β-catenin levels in DEN/CCl4-induced liver tissues and HCC tissues in S100A4−/- mice were clearly downregulated, as indicated by western blot (Figure 6(c)). We further confirmed the upregulation of β-catenin in collagen I plus S100A4-treated Huh-7 cells also by immunofluorescence (Figure 6(d)). Thus, S100A4 seems to affect the β-catenin pathway both in vitro and in vivo.

Cardamonin is a chalcone from Aplinia katsumadai Hayata that inhibits intracellular β-catenin levels. To further test the contribution of β-catenin signaling on Huh-7 cells stemness properties, we applied cardamonin to β-catenin signaling in this assay (Figure 6(e)). The inhibition of β-catenin signaling markedly eliminated the upregulated expression of OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog in Huh-7 cells after collagen/S100A4 stimulation (Figure 6(f)), which suggested that S100A4 may upregulate stem cell-associated genes in collagen I-cultured Huh-7 cells through β-catenin signaling.

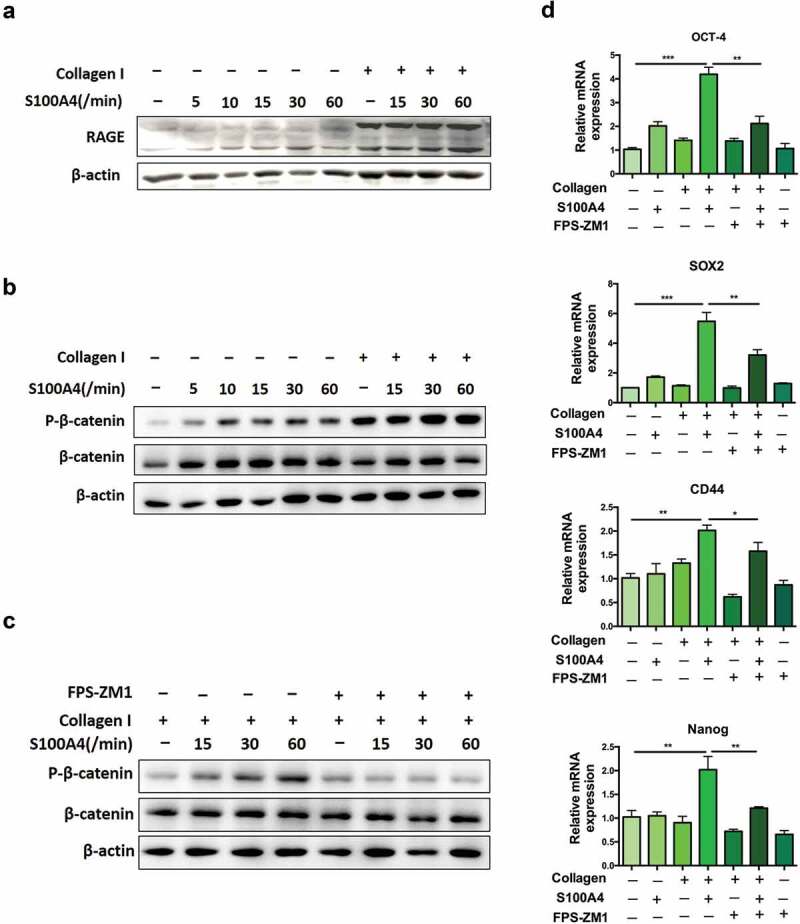

S100a4-induced β-catenin signaling in collagen Ⅰ-cultured huh-7 cells was RAGE dependent

RAGE is a well-accepted interaction partner for S100A4.17,40 We detected whether S100A4-induced β-catenin signaling in collagen I-cultured Huh-7 cells was RAGE dependent. As shown in Figure 7(a), the basal expression of RAGE is very low in Huh-7 cells cultured without collagen I. However, it was clearly upregulated after collagen I stimulation. FPS-ZM1 is a specific antagonist of RAGE, which interacts with the ligand-bingding domain of the receptor to block RAGE signaling.41 Furthermore, we used FPS-ZM1 to prevent RAGE activation in collagen I-cultured Huh-7 cells. As a result, the level of phosphorylated β-catenin could not be upregulated by S100A4/collagen I stimulation (Figure 7(b,c)). Consequently, the expression of stem cell-associated genes was also downregulated by RAGE inhibitors (Figure 7(d)). Thus, our results indicate the critical contribution of the RAGE receptor to the induction of β-catenin signaling in collagen I-cultured Huh-7 cells by S100A4.

Figure 7.

S100A4 induced β-catenin signaling in collagen I cultured Huh-7 cells was RAGE dependent. (a) The expression of RAGE in HCC cells was upregulated after collagen treatment. Huh-7 cells were cultured with or without collagen I and incubated with S100A4 (200 ng/ml) for different time as indicated. Levels of RAGE in Huh-7 cells were determined by western blot. (b) Huh-7 cells were cultured as (a) described, levels of p-β-catenin in Huh-7 cells were determined by western blot analysis. (c) Huh-7 cells were cultured as (a) described, RAGE inhibitor FPS-ZM1 (75 nmol/μl) was added or not, levels of p-β-catenin were determined by western blot analysis. (d) The expression of OCT-4, SOX2, CD44 and Nanog in Huh-7 cells were detected by real-time PCR. * P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001.

Discussion

The mechanism for fibrosis-associated hepatocellular carcinogenesis is rather unclear. In this study, we have demonstrated that S100A4, a liver macrophage-associated molecule, not only affects liver fibrosis as we previously reported but also promotes the development of fibrosis-associated HCC by enhancing fibrosis-related liver cancer stemness. Mechanistically, S100A4 and collagen I together upregulates stem cell-associated genes signatures in liver tumor cells. This process is dependent on the RAGE and β-catenin signaling.

S100A4 has been associated with cancer for a long time, but previous studies were mainly focused on its role in cancer metastasis. S100A4 expression was initially characterized in cells of mesenchymal origin including stromal fibroblasts and epithelial cells undergoing epithelial mesenchymal transition.14,31 However, in the liver, S100A4+ cells mainly represent cells of macrophage origin. Previously, we have reported a critical role of macrophage-derived S100A4 in the liver in promoting liver fibrosis through hepatic stellate cell activation. Moreover, it has been reported that increased S100A4 expression is an independent biomarker for poor outcomes of HCC.22,42 In our current study, IHC analysis of human HCC tissues revealed clear S100A4 expression in over 80% of HCC tissues and most S100A4+ cells accumulated around fibrotic areas in human HCC tissues (Figure 1), suggesting a potential role of S100A4 in fibrogenesis related HCC development. Further study indicated that whole-body genetic deletion of S100A4 in mice attenuates liver fibrosis and resistance to liver cancer development, highlighting the critical role of S100A4 in HCC pathogenesis.

Recently, it has been reported that depletion of S100A4+ stromal cells does not prevent HCC development but reduces the stem cell-like phenotype of HCC tumors in Pten-S100A4 transgenic mice.43 In that study, S100A4+ cells depletion reduced the inflammation but did not affect liver fibrosis. In our study, S100A4-deficient mice developed significantly less and smaller liver tumor nodules (Figure 3(d,e)), with no change in both innate and adaptive immune subsets in the liver (Fig. S1), but decreased liver fibrosis (Figure 3(f)) and expression of stem cell markers in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) tissues (Figure 4(b)). In addition, in our another study, S100A4 significantly promoted liver fibrosis and HCC development induced by anti-CD137 mAb treatment in S100A4-Tk and S100A4−/- mice.24 Thus, the effect of S100A4 on HCC development may be correlated with liver fibrosis. Our findings demonstrated a key role of S100A4-RAGE-β-catenin axis in the promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by affecting fibrosis-associated cancer stemness.

Cancer stem cells are believed to possess stem cell-like properties, such as unlimited self-renewal, exclusive in vivo tumorigenicity, and subsequent generation of differentiated progeny recapitulating the parental tumor phenotype.36,44 The mechanisms of cancer stem cell involvement in the initiation and progression of HCC are still unclear. The contribution of S100A4 to modulating the stemness properties of cancer-initiating cells was first proposed in head and neck and gastric cancers.45,46 Recently, it has been reported that S100A4 is a central node in a molecular network that controls stemness and EMT in glioblastoma.47 In our results, collagen plus S100A4 elicited strong synergistic effects in promoting self-renewal markers, such as Oct-4, Nanog, CD133, SOX2 and CD44 in HCC cells. However, S100A4 alone could not upregulate the stemness genes of liver cancer cells. Our results showed that collagen I and S100A4 provided synergetic effects in promoting the activation of β-catenin signaling in Huh-7 cells. However, whether it is specific to the liver or represents a general mechanism for stem cell activation in other organs remains to be answered.

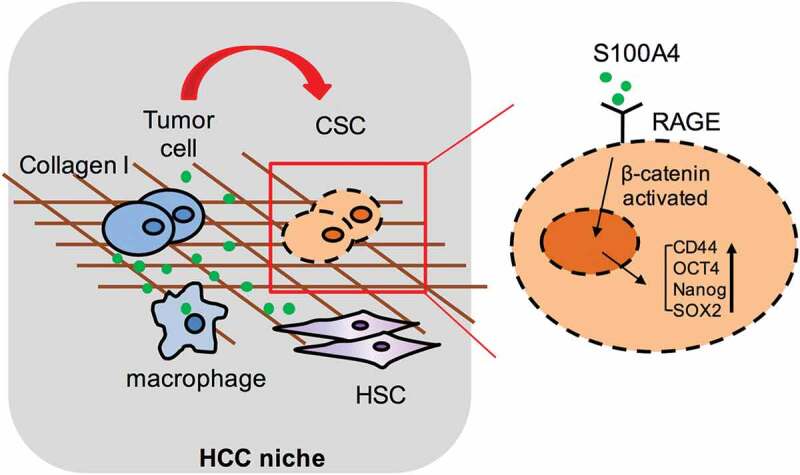

In summary, this study provides both in vitro and in vivo evidence for a critical role of S100A4 in promoting fibrosis-related hepatocarcinogenesis through the crosstalk between macrophage-associated S100A4, fibrotic lesion and HCC stem cells. These results are summarized in a model diagram (Figure 8). It would be important to test further whether anti-S100A4 antagonists may be effective through targeting tumor initiating cells and the tumor microenvironment and therefore provide a potential strategy for liver cancer prevention and treatment.

Figure 8.

Schematic summary for the role of S100A4 in promoting fibrosis-related hepatocarcinogenesis through the crosstalk between macrophage-associated S100A4, fibrotic lesion and HCC stem cells.

Materials and methods

Some detailed information was provided in supplementary data.

Cell lines, mice and antibodies

The murine liver cancer cell line Hep1-6 and human HCC cell line Huh-7 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). These cells were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (HG-DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Heterozygous B6.Cg-Tg (S100a4-EGFP) M1Egn (S100A4+/+GFP)31 and homozygous B6.129S6-S100a4tm1Egn (S100A4−/−) transgenic mice34 were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice and wild-type (WT) control littermates were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facilities at the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Male mice that were 6–8 weeks of age were used. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The experiments described were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Diethylnitrosamine (DEN)/CCl4-induced hepatocellular carcinoma

Mice were first intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with 50 μg/g of DEN (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 ml of PBS at the age of 15 days. Mice at the age of 45 days were then treated with 0.5 μl/g body weight of CCl4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted (1:9) in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by i.p. injection twice weekly for 8 weeks. Tumor development was monitored at 8 months.

Tissue microarray immunohistochemistry staining

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) consisting 75 HCC patient cases for immunohistochemistry were purchased from Xin Chao (Shanghai, China). The company provided ethical statement to confirm that the local ethics committees approved their consent procedures and all study participants signed an approved informed consent form. The ethical statement provided by the company and the protocol of experiment had been checked carefully and approved by Ethics Committee of Beijing Jiaotong University. The tissue microarrays were stained with anti-S100A4 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). In the 75 cases, was carried out for evaluating S100A4 staining according to previous study.48 The intensity of S100A4 expression was scored as follows: 0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong (Figure 1(a)). Extent of staining was scored as follows: 1, 0 to 25%; 2, 25 to 50%; 3, 50 to 75% or 4, 75 to 100%. Five random fields were observed under a light microscope. The final score was determined by multiplying the scores of intensity with the extent of staining. The sum from 0 to 5 was defined as S100A4 negative. The sum from 5 to 45 was defined as S100A4 low expression. The sum from 45 to 80 was defined as S100A4 high expression.

Human samples

For serum S100A4 detection, venous blood was drawn from 20 HCC patients and 20 healthy donors. The informed consent was obtained from all participants before sample collection. The characteristics of patients and healthy donors are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.

Isolation of liver nonparenchymal cells

Briefly, cells were isolated from the liver tissues using a two-stage collagenase perfusion technique as described previously.24 Filtered cells were centrifuged at 50 × g for 2 minutes to remove hepatocytes. The remaining nonparenchymal cell (NPC) fraction was collected, washed, and isolated by a 40% and 70% nonlinear Percoll (GE healthcare biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) gradient system.

In vitro tumor sphere coculture system

Huh-7 and PLC/PRF/5 cells were plated at a density of 1000 cells/ml in ultralow attachment plates in tumor sphere culture medium. We used serum-free DMEM/F-12, supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, 1:100), N2 (Invitrogen, 1:50), 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), 5 ng/ml bFGF, 4 µg/ml heparin, 2 µg/ml insulin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 ng/ml streptomycin.

In vivo tumorigenesis experiment

Huh-7 cells were cultured with or without S100A4 and collagen I for 2 weeks, washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 3 times before injected to nude mice. 1 × 106 cells in 200 μL PBS were subcutaneously injected into the abdominal region of nude mice (n = 6 per group). Starting at day 7 after tumor-cell inoculation, tumor growth was monitored every 2–3 days, and tumor volumes (V) were assessed in mm3 using the formula: V = 0.5 (a × b2) with a being the long and b the short diameters of the tumor. Tumor volumes >100 mm3 were considered as effective tumorigenesis.

Statistical analysis

All of the data were expressed as the mean ± SEM and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. Significant differences between mean values were obtained using three independent experiments. Differences between two groups were compared using Mann–Whitney, and grouped comparison was evaluated by non-parametric ANOVA and subsequent Kruskal–Wallis (Kruskal–Wallis). Correlations between S100A4 expression and clinicopathologic variables were obtained by using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2015CB553705), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81630068, 31670881, 81772497).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author’s Contributions

JZ and ZQ conceived the project. JZ, YL, JW and KS performed the experiments, immunohistological staining, and western blot analysis. SL, HZ and CN participated in the partial animal studies. FW, WZ and JL collected patients’ serum samples. JZ, YL analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. YL, JW, ZQ and JZ finalized the paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, Gores G.. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seitz HK, Stickel F. Risk factors and mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis with special emphasis on alcohol and oxidative stress. Biol Chem. 2006;387:349–13. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O’Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:222–232. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0044-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in USA. Hepatol Res. 2007;37(Suppl 2):S88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutte K, Bornschein J, Malfertheiner P. Hepatocellular carcinoma–epidemiological trends and risk factors. Dig Dis. 2009;27:80–92. doi: 10.1159/000218339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrader J, Gordon-Walker TT, Aucott RL, van Deemter M, Quaas A, Walsh S, Benten D, Forbes SJ, Wells RG, Iredale JP, et al. Matrix stiffness modulates proliferation, chemotherapeutic response, and dormancy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2011;53:1192–1205. doi: 10.1002/hep.24108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Dranoff JA, Chan EP, Uemura M, Sevigny J, Wells RG. Transforming growth factor-beta and substrate stiffness regulate portal fibroblast activation in culture. Hepatology. 2007;46:1246–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang DY, Friedman SL. Fibrosis-dependent mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2012;56:769–775. doi: 10.1002/hep.25670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SK, Kim MH, Cheong JY, Cho SW, Yang SJ, Kwack K. Integrin alpha V polymorphisms and haplotypes in a Korean population are associated with susceptibility to chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2009;29:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fransvea E, Mazzocca A, Antonaci S, Giannelli G. Targeting transforming growth factor (TGF)-betaRI inhibits activation of beta1 integrin and blocks vascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;49:839–850. doi: 10.1002/hep.22731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlodavsky I, Miao HQ, Medalion B, Danagher P, Ron D. Involvement of heparan sulfate and related molecules in sequestration and growth promoting activity of fibroblast growth factor. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1996;15:177–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00437470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, Neilson EG. Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:393–405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boye K, Maelandsmo GM. S100A4 and metastasis: a small actor playing many roles. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:528–535. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semov A, Moreno MJ, Onichtchenko A, Abulrob A, Ball M, Ekiel I, Pietrzynski G, Stanimirovic D, Alakhov V. Metastasis-associated protein S100A4 induces angiogenesis through interaction with Annexin II and accelerated plasmin formation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20833–20841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yammani RR, Carlson CS, Bresnick AR, Loeser RF. Increase in production of matrix metalloproteinase 13 by human articular chondrocytes due to stimulation with S100A4: role of the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2901–2911. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1529-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiryushko D, Novitskaya V, Soroka V, Klingelhofer J, Lukanidin E, Berezin V, Bock E. Molecular mechanisms of Ca(2+) signaling in neurons induced by the S100A4 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3625–3638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3625-3638.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osterreicher CH, Penz-Osterreicher M, Grivennikov SI, Guma M, Koltsova EK, Datz C, Sasik R, Hardiman G, Karin M, Brenner DA, et al. Fibroblast-specific protein 1 identifies an inflammatory subpopulation of macrophages in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:308–313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017547108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudland PS, Platt-Higgins A, Renshaw C, West CR, Winstanley JH, Robertson L, Barraclough R. Prognostic significance of the metastasis-inducing protein S100A4 (p9Ka) in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1595–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gongoll S, Peters G, Mengel M, Piso P, Klempnauer J, Kreipe H, von Wasielewski R. Prognostic significance of calcium-binding protein S100A4 in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1478–1484. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Liu H, Pan H, Du Q, Liang J. Clinicopathological significance of S100A4 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:457–462. doi: 10.1177/0300060513478086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Chen L, Xiao M, Wang C, Qin Z. FSP1+ fibroblasts promote skin carcinogenesis by maintaining MCP-1-mediated macrophage infiltration and chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Song K, Wang J, Li Y, Liu S, Dai C, Chen L, Wang S, Qin Z. S100A4 blockage alleviates agonistic anti-CD137 antibody-induced liver pathology without disruption of antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1296996. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1296996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou S, Tian T, Qi D, Sun K, Yuan Q, Wang Z, Qin Z, Wu Z, Chen Z, Zhang J, et al. S100A4 promotes lung tumor development through beta-catenin pathway-mediated autophagy inhibition. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:277. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0319-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Bao J, Bian Y, Erben U, Wang P, Song K, Liu S, Li Z, Gao Z, Qin Z, et al. S100A4(+) macrophages are necessary for pulmonary fibrosis by activating lung fibroblasts. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1776. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown ZJ, Heinrich B, Greten TF. Mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview and highlights for immunotherapy research. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15:536–554. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uehara T, Pogribny IP, Rusyn I. The DEN and CCl4 -induced mouse model of fibrosis and inflammation-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2014;66:1430 11–14 30 10. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.2014.66.issue-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Zhao W, Cheng L, Guo M, Li D, Li X, Tan Y, Ma S, Li S, Yang Y, et al. CD137-mediated pathogenesis from chronic hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:7654–7662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG. Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:341–350. doi: 10.1172/JCI0215518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen L, Li J, Zhang J, Dai C, Liu X, Wang J, Gao Z, Guo H, Wang R, Lu S, et al. S100A4 promotes liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2015;62:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue C, Plieth D, Venkov C, Xu C, Neilson EG. The gatekeeper effect of epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulates the frequency of breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3386–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuchs BC, Hoshida Y, Fujii T, Wei L, Yamada S, Lauwers GY, McGinn CM, DePeralta DK, Chen X, Kuroda T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition attenuates liver fibrosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;59:1577–1590. doi: 10.1002/hep.26898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang L, Inokuchi S, Roh YS, Song J, Loomba R, Park EJ, Seki E. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in hepatocytes promotes hepatic fibrosis and carcinogenesis in mice with hepatocyte-specific deletion of TAK1. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1042–1054 e1044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beck B, Blanpain C. Unravelling cancer stem cell potential. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:727–738. doi: 10.1038/nrc3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oishi N, Yamashita T, Kaneko S. Molecular biology of liver cancer stem cells. Liver Cancer. 2014;3:71–84. doi: 10.1159/000343863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R. Modern pathogenetic concepts of liver fibrosis suggest stellate cells and TGF-beta as major players and therapeutic targets. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:76–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hua F, Shang S, Yang YW, Zhang HZ, Xu TL, Yu JJ, Zhou DD, Cui B, Li K, Lv -X-X, et al. TRIB3 interacts with beta-catenin and TCF4 to increase stem cell features of colorectal cancer stem cells and tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:708–721 e715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dahlmann M, Okhrimenko A, Marcinkowski P, Osterland M, Herrmann P, Smith J, Heizmann CW, Schlag PM, Stein U. RAGE mediates S100A4-induced cell motility via MAPK/ERK and hypoxia signaling and is a prognostic biomarker for human colorectal cancer metastasis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3220–3233. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.v5i10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deane R, Singh I, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Ross NT, LaRue B, Love R, Perry S, Paquette N, Deane RJ, et al. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1377–1392. doi: 10.1172/JCI58642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhai X, Zhu H, Wang W, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Mao G. Abnormal expression of EMT-related proteins, S100A4, vimentin and E-cadherin, is correlated with clinicopathological features and prognosis in HCC. Med Oncol. 2014;31:970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiao J, Gonzalez A, Stevenson HL, Gagea M, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, Beretta L. Depletion of S100A4(+) stromal cells does not prevent HCC development but reduces the stem cell-like phenotype of the tumors. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:e422. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng LH, Hung KF, Huang TF, Hsieh HP, Wang SY, Huang CY, Lo JF. Attenuation of cancer-initiating cells stemness properties by abrogating S100A4 calcium binding ability in head and neck cancers. Oncotarget. 2016;7:78946–78957. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo J, Bian Y, Wang Y, Chen L, Yu A, Sun X. S100A4 influences cancer stem cell-like properties of MGC803 gastric cancer cells by regulating GDF15 expression. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:559–568. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chow KH, Park HJ, George J, Yamamoto K, Gallup AD, Graber JH, Chen Y, Jiang W, Steindler DA, Neilson EG, et al. S100A4 is a biomarker and regulator of glioma stem cells that is critical for mesenchymal transition in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:5360–5373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang SF, Wang XY, Fu ZQ, Peng QH, Zhang JY, Ye F, Fu YF, Zhou CY, Lu WG, Cheng XD, et al. TXNDC17 promotes paclitaxel resistance via inducing autophagy in ovarian cancer. Autophagy. 2015;11:225–238. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2014.998931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.