Abstract

A 70-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for dyspnea and a fever of 2 weeks duration. Chest imaging showed bilateral infiltration, and a rapid diagnostic test for influenza virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Legionella spp. was negative. She was intubated and mechanically ventilated and underwent bronchoalveolar lavage. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid yielded no significant pathogens, and the multiplex polymerase chain reaction test was positive only for human bocavirus. Specific antibodies against significant pathogens were not increased in paired sera, so we diagnosed her with primary human bocavirus pneumonia.

Keywords: primary human bocavirus pneumonia, fatal, adults, immunocompetent

Introduction

Human bocavirus (HBoV) is an emerging pathogen for which sequences were identified in 2005 by molecular screening in respiratory samples of Swedish children with lower respiratory tract infections (1). HBoV is distributed worldwide and has been identified in every country that has tested for it. HBoV infections do not appear to be common in normal adults with respiratory illnesses but are mainly reported in immunocompromised individuals (2,3).

We herein report a fatal case of primary HBoV pneumonia in an immunocompetent adult and discuss HBoV.

Case Report

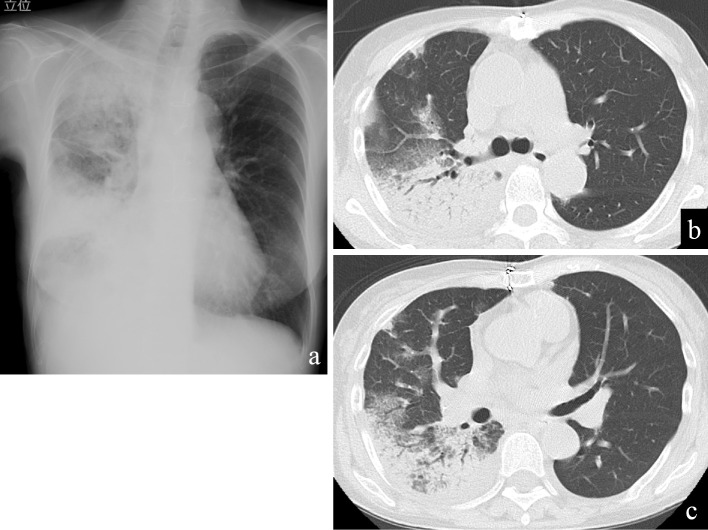

A 70-year-old woman was transferred to our hospital with severe respiratory failure and a fever in June 2018. She had developed general fatigue two weeks earlier and was admitted to another hospital nine days before transfer to our hospital. Chest X-ray and computed tomography at that hospital showed consolidation in the right lung field (Fig. 1), whereas her left lung was clear. Sputum and blood cultures did not yield significant pathogens. She was diagnosed with pneumonia and treated with levofloxacin plus ampicillin/sulbactam, but her condition continued to worsen, and she was transferred to our hospital.

Figure 1.

Chest imaging on admission to another hospital before transfer to our hospital. Chest X-ray showed right-sided consolidations (a). Chest computed tomography showed consolidations and ground-glass opacities in the right lung field (b, c). No pleural effusion was present.

She had a history of atrioseptal defect for which she had received surgery at 20 years of age, but she had received no drugs until she developed her initial symptoms. She had never experienced repeated episodes of infection that would be suggestive of immunodeficiency. She had never smoked or drunk, nor had she ever been exposed to significant amounts of dust.

Her vital signs on admission included a blood pressure of 135/78 mmHg, heart rate of 115 beats/min, respiratory rate of 32/min, and body temperature of 37.5℃. Her consciousness was clear. Chest auscultation revealed bilateral coarse crackles, and no murmurs were audible. No eruptions or peripheral edema was found. An arterial blood gas analysis under O2 at 10 L/min with a reservoir mask showed the following: pH 7.397, PaCO2 49.8 Torr, PaO2 62.0 Torr, HCO3− 29.9 mmol/L, and lactate 1.40 mmol/L. Her white blood cell count was 29,700/mm3 (neutrophils 28,400/mm3, eosinophils 0/mm3, basophils 100/mm3, monocytes 600/mm3, and lymphocytes 600/mm3), with hemoglobin of 10.1 g/dL and a platelet count of 52.2×104/mm3. Other laboratory data included a serum total protein of 7.2 g/dL, albumin of 1.9 g/dL, normal liver transaminase, LDH of 177 IU/L, creatine kinase of 82 IU/L, C-reactive protein of 29.4 mg/dL, procalcitonin of 0.830 ng/mL, immunoglobulin (Ig) G of 1,516 mg/dL, IgA of 303 mg/dL, and IgM of 149 mg/dL. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibodies were both negative. Serum autoimmune antibodies, including anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, were all negative. A rapid influenza test and Mycoplasma antigen test using a nasopharyngeal specimen were negative, as were the urine antigens of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Legionella spp. A beta-D glucan and Aspergillus antigen test were both negative. An anti-HIV antibody was negative. Chest X-ray showed bilateral consolidation with air bronchogram (Fig. 2a). Chest computed tomography showed bilateral pleural effusion, bilateral consolidation with air bronchogram, and ground-glass opacities in her left lung (Fig. 2b, c). Left ventricular motion on transthoracic echocardiography was normal with an ejection fraction of 65%.

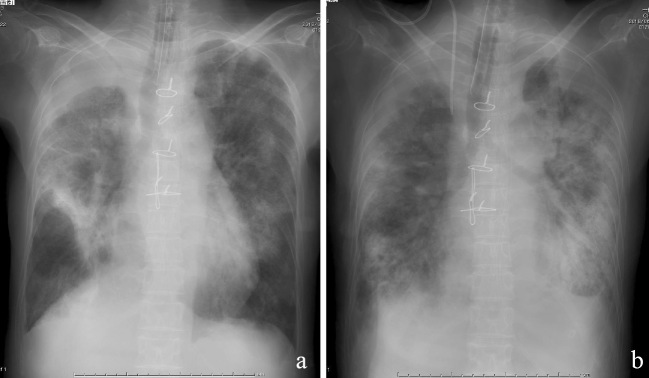

Figure 2.

Chest imaging on admission to our hospital. Chest X-ray showed bilateral consolidations (a). Chest computed tomography showed bilateral consolidations (b), ground-glass opacities, and bilateral pleural effusion (c).

She was admitted to the intensive-care unit and then intubated for invasive mechanical ventilation. We initially diagnosed her with acute interstitial pneumonia and started levofloxacin 500 mg daily, azithromycin 500 mg daily, and methylprednisolone 1 g daily for 3 days. Prednisolone 40 mg daily was started from hospital day 4, after which her respiratory condition and infiltration on chest X-ray improved (Fig. 3a). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) obtained bloody BAL fluid with cell numbers of 1.48×103/mm3 (macrophages 1.3%, lymphocytes 65.8%, neutrophils 26.8%, and eosinophils 6.2%) but did not show any microorganisms on Gram staining or yield significant pathogens, including M. pneumoniae or Legionella spp. Neither hemosiderin-laden macrophages nor atypical cells were found. We performed a multiplex, real-time polymerase chain reaction using an FTD Resp 21 Kit and FTD Legionella Kit (Fast Track Diagnostics, Silema, Malta), which can detect influenza virus, human rhinovirus, human coronavirus, human parainfluenza virus 1-4, human metapneumovirus A/B, HBoV, human syncytial virus A/B, human adenovirus, enterovirus, human parechovirus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila and L. longbeachae, although only HBoV was detected. Repeated blood cultures during admission were all negative. During the convalescent phase, specific antibody titers against M. pneumoniae, Legionella spp., Chlamydophila pneumoniae, C. psittaci, influenza virus, adenovirus, RSV, and human parainfluenza virus did not increase significantly. We therefore diagnosed her with primary viral pneumonia due to HBoV.

Figure 3.

Chest X-ray findings during hospitalization. Chest X-ray performed on hospital day 4 showed improvement of infiltration bilaterally (a); however, bilateral consolidation had increased and worsened by hospital day 22 (b).

Unfortunately, her respiratory condition and findings of infiltration on chest X-ray worsened, and she stopped responding to further corticosteroid therapy and antibiotics. Her condition deteriorated until her death on hospital day 22 from severe respiratory failure with broad bilateral infiltration noted on chest X-ray (Fig. 3b).

Discussion

HBoV is predominantly found in respiratory secretions, and prevalence studies have indicated that it is found primarily in respiratory secretions from children with acute respiratory illnesses, at a rate of 2% to 20% (4). Although found throughout the year, primary HBoV infection predominantly occurs in the winter and spring, as do many other respiratory infections. Evidence accumulated since 2005 supports HBoV as a genuine human pathogen causing mild to severe respiratory tract infections that especially target children (5). Risk factors for severe HBoV1-associated illnesses include underlying chronic medical conditions, such as cardiac or pulmonary disease, prematurity with chronic lung disease, cancer, and immunosuppression (6); however, our patient had none of these conditions.

HBoV is detected in nasopharyngeal specimens in about 0-8.6% of asymptomatic children (7). Our hospital did not detect HBoV from BAL fluid in any of 50 asymptomatic adults (unpublished data), indicating the rarity of HBoV detection in BAL fluid from asymptomatic adults. Another study showed that HBoV DNA is rarely detected in respiratory samples of adult patients over 65 years of age with or without a respiratory tract infection (6). Other studies have shown HBoV DNA to be common in tonsillar tissue taken from children with hypertrophic tonsils (8). However, our patient was already intubated when BAL was performed, so the possibility of contamination by viruses colonizing the nasopharyngeal region can be ruled out. Although HBoV infection frequently involves coinfection with other pathogens (9), our patient had a positive result only for HBoV, and we thus considered her to have primary viral pneumonia.

Several cases of severe, life-threatening, and even fatal respiratory HBoV infection have been reported, most of which were in children. Adult cases include one patient with hematologic malignancy who had severe pneumonia due to HBoV (10) and another with no underlying disease (11). To our knowledge, there have been no reported cases of fatal HBoV infections in immunocompetent adults.

Chest CT findings of HBoV pneumonia in adults include bilateral consolidation (70.6%) and/or ground-glass opacities (64.7%), but centrilobular nodules are less frequent (14.7%) (12). These findings were compatible with those of our patient, but they were nonspecific, and we had also initially diagnosed our patient with acute interstitial pneumonia. We subsequently changed the diagnosis to viral pneumonia based on a multidisciplinary discussion considering the positive results of HBoV.

No specific treatment currently exists for HBoV infection. Our administration of corticosteroid with antibiotics failed. The significance of corticosteroid use in the treatment of pneumonia remains controversial (13), and our patient's condition progressively deteriorated until her death despite its use. Further studies are needed to establish an effective treatment for this infection.

One limitation of the present study is that we were unable to measure the quantitative HBoV viral loads in the respiratory BAL fluid of our patient. Although a previous pediatric study showed that this measurement can quantitate disease severity (14), viral loads for HBoV infection are not routinely assessed in our hospital.

Conclusion

We herein report a fatal case of primary HBoV pneumonia. Despite the high prevalence of pediatric HBoV infections, the virus continues to be underrecognized by many physicians. Our case shows that, even in immunocompetent adults, HBoV is an emerging pathogen that requires closer attention (15).

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Financial Support

T.I. received a grant from the Saitama Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center (grant no. 16ES).

References

- 1. Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12891-12896, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maggi F, Andreoli E, Pifferi M, Meschi S, Rocchi J, Bendinelli M. Human bocavirus in Italian patients with respiratory diseases. J Clin Virol 38: 321-325, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manning A, Russell V, Eastick K, et al. . Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human parvoviruses. J Infect Dis 194: 1283-1290, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jartti T, Hedman K, Jartti L, Ruuskanen O, Allander T, Söderlund-Venermo M. Human bocavirus-the first 5 years. Rev Med Virol 22: 46-64, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meriluoto M, Hedman L, Tanner L, et al. . Association of human bocavirus 1 infection with respiratory disease in childhood follow-up study, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis 18: 264-271, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen A, Kesti O, Elenius V, et al. . Human bocaviruses and paediatric infections. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 3: 418-426, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ishiguro N, Endo R. Human bocavirus infection. Nihon Kyobu Rinsho 69: 822-833, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Proença-Módena JL, Buzatto GP, Paula FE, et al. . Respiratory viruses are continuously detected in children with chronic tonsillitis throughout the year. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78: 1655-1661, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamano-Hasegawa K, Morozumi M, Nakayama E, et al. . Comprehensive detection of causative pathogens using real-time PCR to diagnose pediatric community-acquired pneumonia. J Infect Chemother 14: 424-432, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kupfer B, Vehreschild J, Cornely O, et al. . Severe pneumonia and human bocavirus in adults. Emerg Infect Dis 12: 1614-1616, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krakau M, Gerbershagen K, Frost U, et al. . Case report: human bocavirus associated pneumonia as cause of acute injury, Cologne, Germany. Medicine 94: e1587, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee HN, Koo HJ, Kim SH, Choi SH, Sung H, Do KH. Human bocavirus infection in adults: clinical features and radiological findings. Korean J Radiol 20: 1226-1235, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Confalonieri M, Kodric M, Santagiuliana M, et al. . To use or not to use corticosteroids for pneumonia? A clinician's perspective. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 77: 94-101, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang W, Yin F, Zhou W, Yan Y, Ji W. Clinical significance of different virus load of human bocavirus in patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Sci Rep 6: 20246, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ma X, Endo R, Ishiguro N, et al. . Detection of human bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol 44: 1132-1134, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]