Abstract

Offsetting—trading losses in one place for commensurate gains in another—is a tool used to mitigate environmental impacts of development. Biodiversity and carbon are the most widely used targets of offsets; however, other ecosystem services are increasingly traded, introducing new risks to the environment and people. Here, we provide guidance on how to “trade with minimal trade-offs”— i.e. how to offset impacts on biodiversity without negatively affecting ecosystem services and vice versa. We briefly survey the literature on offsetting biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services, revealing that each subfield addresses unique issues (often overlooking those raised by others) and rarely assesses potential trade-offs. We discuss key differences between offsets that trade biodiversity and those that trade ecosystem services, conceptualise links between these different targets in an offsetting context and describe three broad approaches to manage potential trade-offs. We conclude by proposing a research agenda to strengthen the outcomes of offsetting policies that are emerging internationally.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13280-019-01245-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Biodiversity, Ecosystem services, Mitigation hierarchy, Offsetting, Trade-offs

Introduction

Offsetting—trading losses in one place for gains in another—is a conservation approach used to mitigate the impacts of development on nature, often in an attempt to achieve no net loss (NNL) to ecosystems. To date, most offsetting has focused on trading either biodiversity (BBOP 2012) or carbon (Agrawal et al. 2011) and these policies and projects have been the subject of distinct academic literatures. Some other policies have also targeted specific ecosystem services (e.g. Canada’s NNL policy on productive fish habitat; Harper and Quigley 2005). Recently, however, like many other conservation activities, offsets have broadened in scope to target an increasingly wide range of ecosystem services—the ways in which ecosystems contribute to human wellbeing—such as food and fibre provision, water and air quality regulation and opportunities for cultural and recreational experiences (Sonter et al. 2018). These changes have happened quickly; requirements to offset impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services are now evident in government policies (Schulp et al. 2016), international financing agreements (IFC 2012), corporate strategies and industry standards (ICMM and IUCN 2013) and international conventions (Cowie et al. 2018). We note that some place-based spiritual or cultural services cannot be offset (Bull et al. 2018), as a loss at one site simply cannot be adequately compensated for with a gain at another. Here, when discussing ecosystem services, we are referring to those for which exchanging a loss at one site for a gain elsewhere is feasible (e.g. can be measured) and socially/culturally acceptable.

Multiple factors have led to an expansion in the scope of offsets to include other ecosystem services. Namely, there is growing awareness that biodiversity loss affects human wellbeing (Díaz et al. 2015) and that conserving ecosystem services can achieve positive outcomes for nature and people (Dee et al. 2017). However, relationships between biodiversity and ecosystem services are not always positive (Ricketts et al. 2016) and, although synergistic opportunities may exist to offset both goals at once (Venter et al. 2009), trade-offs may also occur (Bateman et al. 2013). For example, enhancing wetland biodiversity negatively affected nutrient retention in Sweden (Hansson et al. 2005). Further, even when positive relationships exist between biodiversity and the ecological supply of a service, it does not mean there will be an increased benefit to people (Watson et al. 2019). For example, conserving stream biodiversity may enhance fish populations, but reduce benefits to anglers if conservation prevents resource access. Without careful planning, offsetting biodiversity may negatively affect the service supply and benefits, just like offsetting services may negatively affect biodiversity.

Trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services have received considerable attention in the conservation and restoration literatures (Benayas et al. 2009; Mace et al. 2012); less attention has been given to trade-offs in an offsetting context (Tallis et al. 2015). Many challenges associated with trade-offs are shared among other conservation instruments, yet two factors are unique to the offsetting context. First, trade-offs are often difficult to identify and thus manage, since they can emerge from both the development and offsetting activities. For example, at Rio Tinto’s Ambatovy nickel mine, loss of access to ecosystem services at both the mine site and its associated biodiversity offset negatively affected the provision of food and fibre to local communities (Bidaud et al. 2017). In some cases, these trade-offs may be an implicit goal of offsetting; achieving additional biodiversity gains often involves preventing human access to ecosystems (Sonter et al. 2014). Managing trade-offs is particularly important given that offsets are compensatory activities. While other conservation actions, such as implementing protected areas, often aim to optimise multiple goals (inevitably allowing some trade-off); offsets, with their grounding in measurable loss-gain trades and explicit outcomes like NNL, must meet each individual (and independent) goal. Second, any unmanaged trade-offs may render offsets unsuccessful in achieving NNL objectives, as they can cause additional loss to other goals that then require further compensation (Bull et al. 2018). Although some policies require these trade-offs to be managed (including IFC’s Performance Standards 5 and 6), significant challenges remain to identifying and managing them in practice (Bidaud et al. 2018).

Therefore, our purpose here is to provide guidance on how to offset impacts of development on biodiversity and ecosystem services, while minimising potential trade-offs. To do this, we briefly synthesise the peer-reviewed literature on offsetting biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services. Second, we discuss key differences between offsetting biodiversity and ecosystem services (in terms of the spatial scale of trades, equivalence metrics and concepts of additionality). In doing so, we illustrate the key challenges involved in expanding biodiversity offsets to ecosystem services, and vice versa. We then present a novel conceptual framework illustrating the potential links between biodiversity and ecosystem services in an offsetting context and discuss three broad approaches to minimise trade-offs and enhance potential synergies. We conclude by proposing a research agenda that aims to enhance the outcomes of international mitigation policies.

Links between offsetting biodiversity and ecosystem services

Three distinct literature bodies have examined offsets to date. Our survey of 700 papers (Appendix S1 and Database S1) revealed that, although offsetting biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services are overlapping topics, each has spawned a unique subfield with unique histories [often aligning with emerging policies driving their use in practice (e.g. Calvet et al. 2015)], distinct emphases and efforts to address different challenges. Given that subfields were largely independent (< 8% of papers occurred in more than one subfield), it was not surprising to find differences in how each conceptualised offsets. Biodiversity studies used strict area-based definitions and focused on how to achieve NNL of species and ecosystems, while studies on carbon and other ecosystem services were more diverse, evaluating economic mechanisms for implementation (McDermott 2014; Pasgaard et al. 2016), and addressing interdisciplinary challenges of equity (Mandle et al. 2015; Schulp et al. 2016), but not always seeking NNL goals.

Further, very few papers on offsets occurred in multiple subfields, illustrating a limited sharing of ideas among them (although see Needham et al. 2019 for a recent synthesis of what biodiversity offsets can learn from tradeable pollution permits). Of those that did, most examined consequences of trading one objective (e.g. carbon) on other outcomes (e.g. water supply; Jackson et al. 2005), with a particular focus on positive co-benefits. Fewer papers examined negative trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services and, when they did, simplifications were made—e.g. inadequate biodiversity metrics were used and concepts of additionality were ignored. Very few papers examined integrated offsets (i.e. when biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services are traded simultaneously). As a result, the extent to which trade-offs occur in practice is unclear and the tools needed to minimise them are underdeveloped, despite the apparent increase in offset projects aiming to achieve positive outcomes for both biodiversity and ecosystem services (Sonter et al. 2018).

Differences in offsetting biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services

While the principles underpinning offsetting are similar for biodiversity, carbon and other ecosystem services, our literature survey suggests the challenges of developing and implementing sound approaches to trade each objective differs substantially. Here we summarise key differences in terms of the spatial scale of offset trades and the way in which equivalence and additionality of gains generated by the trade should be calculated. Our purpose is to illustrate the potential for cryptic trade-offs (i.e. those that are not reasonably foreseeable) that add to the challenges involved to identify and manage consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem services simultaneously.

Spatial scale over which trades occur

Offsetting, by definition, involves exchanging a loss in one place for gains in another. The equivalence (in terms of ‘like-for-like’) of these trades will often, although not always, depend on the spatial location of these two places. For biodiversity, opportunities to make equivalent trades are often a function of distance, because ecological similarity decays with distance (Nekola and White 1999; Soininen et al. 2007), however, allowing offsets to be placed at greater distances from the impact site potentially allows more cost-effective gains (due to a greater selection of offset sites to be chosen from). Currently, many policies require or encourage offsets to be located close to the impact they are to counterbalance. However, for ecosystem services, the spatial scale of trades will depend on patterns of both ecological supply and human demand (Burkhard et al. 2014). For some services (such as carbon storage), the location of human beneficiaries and where trades are made does not influence the receipt of benefits. For example, increasing carbon storage anywhere on Earth (eventually) provides an equivalent offset for a given quantum of carbon emitted, as all carbon sequestration contributes to global climate regulation (although spatial distribution of projects affects costs and effectiveness in undertaking carbon trades; Chomitz 2002). In this case, it is reasonable for offsets to be established wherever they most effectively generate gains. However, at the other extreme, offsetting a loss in productivity of local fisheries for one human community may only be acceptable if the offset is situated so that the same community can access it to satisfy their demand (Griffiths et al. 2018).

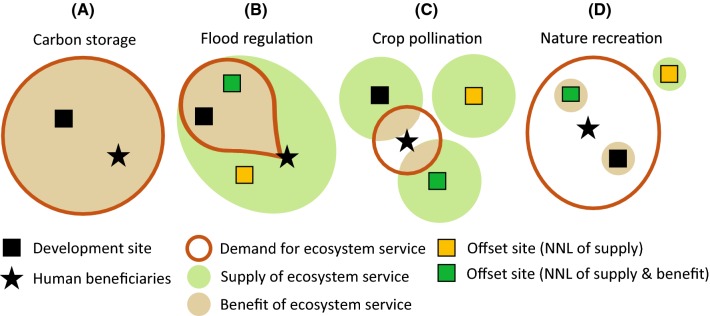

Trading ecosystem services becomes particularly complex when there is a mismatch between the areas supplying ecosystem services and the areas where people demand benefits from them (Fisher et al. 2009; Serna-Chavez et al. 2014; Tallis et al. 2015). A mismatch (or a lack of “flow”) between areas of supply and demand can exist either when service supply does not reach potential beneficiaries (e.g. pollinator habitat is further than bee foraging distance from nearby crops), or when people who demand services are unable to access their benefits (e.g. a lack of infrastructure prevents disabled tourists accessing a nature reserve). Whether flow occurs between supply and demand also depends on other spatial dynamics, such as the areas’ proximity and the overall landscape fragmentation and permeability (Mitchell et al. 2015). Hence, for offsets to achieve NNL of benefits to specific human beneficiaries, ecosystem services trades must consider the spatial distribution of their supply and demand, and offsets be established at a site that ensures flows between these places (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of ecosystem service supply, demand, flow and benefit. Figure shows four cases where development causes a loss in service supply and benefit to people. The demand for services is drawn relative to the negatively affected human beneficiaries; it represents the area where people will potentially benefit from services. Ecosystem service supply is drawn relative to development and offset sites; it indicates the area across which services can potentially benefit people. A benefit to humans is therefore achieved where areas of supply and demand intersect (or flow; shaded light brown in the figure). For an offset to achieve NNL in supply and benefit, a fundamental requirement is that it must be located in an area where supply intersects demand. On top of this requirement, the offset must then also deliver gains that are additional. See Appendix S2 for an expanded description of each service (a–d)

Equivalence in the trade (in-kind versus out-of-kind)

The challenge of determining which units, or metrics, of losses and gains ought to be measured varies substantially among different types of offset exchanges. Carbon is the most straightforward example, since emissions anywhere can be assumed fungible by being converted to carbon dioxide equivalent units (Lashof and Ahuja 1990; Fig. 1). For biodiversity, although debate continues about the appropriateness of different metrics (Quetier and Lavorel 2011), widely-adopted approaches include the number of individuals of a species, hectares of a given species’ habitat or quality-weighted hectares of a particular ecosystem type (Maseyk et al. 2016). These units remain largely arbitrary attempts to capture aspects of biodiversity that people care about and for which they wish to achieve NNL (Maron et al. 2016). Although these units are often complicated to calculate, they are less complex than metrics intended explicitly to capture losses and gains in ecosystem services.

Since ecosystem services are, by definition, experienced by people, and those experiences are spatially heterogeneous, no matter how small, metrics that capture benefit directly are rarely used in offsetting (Griffiths et al. 2018). Instead, proxies are typically employed, often relating to the supply of ecosystem services, such as nutrient reduction to maintain water quality supply (Greenhalgh and Selman 2012). For services with global flows—like climate regulation—this is acceptable, since the location of development and offset sites will not influence the benefits to people. However, for other services (such as flood regulation, crop pollination and nature-based recreation shown in Fig. 1), the complexity of ‘who benefits and how?’ continues to complicate offsetting decisions (Mandle et al. 2015; Bidaud et al. 2017). It seems unacceptable for a loss in services to one group of people to be considered equivalent to a gain in that service for another group of people (Bull et al. 2018). On the other hand, since ecosystem services ought to be measured in terms of benefits to people, a potentially interchangeable “wellbeing or currency unit” has been proposed for use within services and even, perhaps, among services or human beneficiaries (Griffiths et al. 2018). While these issues have been conceptualised (e.g. Tallis et al. (2015) identified three ways in which equivalence in ecosystem services trades should be assessed, i.e. exchanges between services, among beneficiaries and when using substitutes, such as monetary payments), implications have not been explored in practice.

Additionality of gains

Any offset must generate benefits that are additional to what would otherwise have occurred and that additional benefit must be equivalent to the losses due to development (BBOP 2012; IPCC 2014; IUCN 2016). Measuring or estimating additional benefit is a central and ongoing challenge for offsetting of all kinds and, indeed, for evaluating the impact of any environmental programme (Ferraro 2009; Maron et al. 2013). Estimating the additionality of biodiversity and carbon offsets both involve developing counterfactual scenarios for the supply or availability of the target (species, habitat, carbon storage, etc.) and the difference made to these scenarios by the offset (Gordon et al. 2011; Bull et al. 2014). While this can be technically and conceptually fraught and is subject to much discussion in their respective literatures (Olander et al. 2008; Maron et al. 2018), it is even more complex for ecosystem services. For ecosystem services where demand and flow are dynamic, counterfactual scenarios for all components (supply, demand and flow) will be required to determine the additionality of the offset’s service provision. A given impact on the supply of an ecosystem service may be a poor indication of the impact on the benefits it provides if demand or flow dynamics change, for example, due to technology innovation or infrastructure establishment. For example, a biodiversity offset may provide additional habitat for native pollinators, but may not increase crop yields in surrounding landscapes if farmers are resettled elsewhere.

Conceptualising links between offsets for biodiversity and ecosystem services

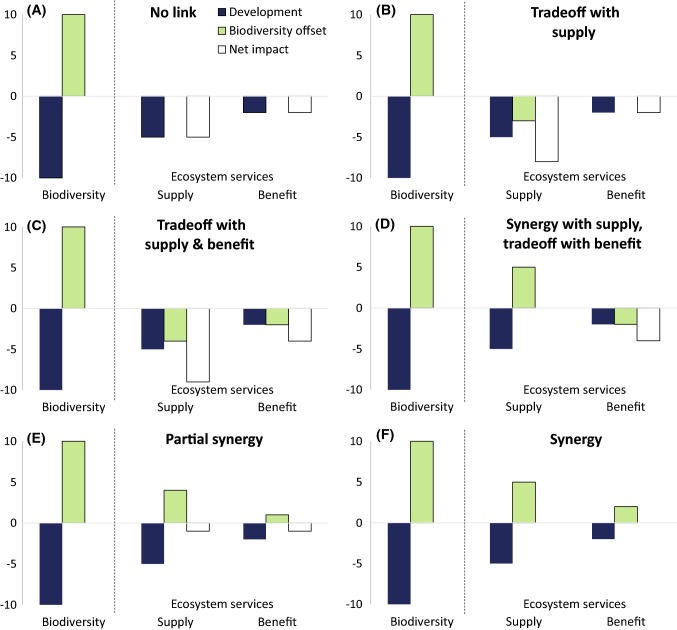

Given that very few studies examined both biodiversity and ecosystem services in the context of offsetting (see Appendix S1), and that offsets for each objective differ in how they make trades and achieve equivalence and additionality, the first challenge to mitigating trade-offs is to identify when and how they occur. Previous studies discuss the need to integrate biodiversity and ecosystem services into offsetting activities (Tallis et al. 2015) and develop software tools to investigate how offsets affect biodiversity and ecosystem services (Mandle et al. 2016); but none has developed a conceptual framework to illustrate the full spectrum of potential outcomes in terms of trade-offs and synergies. Here, we illustrate three broad potential outcomes at an offset site (no link, trade-offs and synergies; Fig. 2), which depend on the links between biodiversity and ecosystem services. Figure 2 illustrates consequences of offsetting on ecosystem services, for the case where development negatively affects biodiversity and the supply and benefit of ecosystem services, and the offsets achieves NNL of biodiversity. However, equivalent cases would exist for offsets that seek to achieve NNL of ecosystem services.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework illustrating consequences of biodiversity offsets on ecosystem services, for the case where development causes losses (negative values) in biodiversity and ecosystem services and offsets generate biodiversity gains (positive values). Net impacts are the difference between losses due to development and gains due to offsetting); they equal 0 when NNL is achieved and are negative when residual losses remain. Graphs show six potential outcomes for ecosystem services, depending on their link to biodiversity at the offset site: a no link, where biodiversity gains do not affect the service supply or benefit (and thus residual losses remain); b trade-offs where biodiversity gains negatively affect supply (and thus net losses for supply are larger than losses caused by development); c trade-offs where biodiversity gains negatively affect supply and benefit; d a combination of synergies and trade-offs, where biodiversity gains positively affect supply (and achieves NNL) but negatively affect benefit and e partial and f full synergies where biodiversity gains positively affect supply and benefit. This series of graphs could also be drawn to illustrate the consequences of ecosystem services offsets on biodiversity, for example when offsets generate equivalent gains in service supply and have trade-offs/synergies with biodiversity

No links

There may be no link between biodiversity and ecosystem services at the offset site, i.e. a change in biodiversity at the offset site does not affect the supply or benefit of ecosystem services (Fig. 2a). This may occur if the biodiversity traded does not supply a service or if the offset is established in a remote location where there is limited accessibility or demand for the service that it does provide (Fig. 1). There may also be no link at the offset site, even when a significant link exists at the development site. For example, vegetation clearing along a riparian buffer may negatively affect sediment retention and downstream water quality regulation, but offsets that establish these species in a non-riparian area may not affect the supply and benefits of those services. Similarly, offsets for ecosystem services may have no link with biodiversity. For example, offsets that increase carbon storage may have relatively minor benefits for biodiversity conservation (Budiharta et al. 2018). In this case, separate offsets for biodiversity and ecosystem services would be needed to mitigate losses due to development, but there is no need for additional offsets to mitigate negative trade-offs.

Trade-offs

Trade-offs may emerge when an increase in biodiversity at the offset site causes a loss in ecosystem services, or when increases in ecosystem services at the offset causes a loss of biodiversity. In these cases, biodiversity is negatively linked to the supply (Fig. 2b) or benefits (Fig. 2c) of ecosystem services to people. For example, offsets that create gains in biodiversity through upstream revegetation may decrease water supply to regional agricultural land users. Similarly, gains in the supply and benefit of non-timber forest products could negatively affect specific threatened species. Trade-offs in benefits of services may also occur independent to supply (Fig. 2d), for example, if offsets prevent human access to services (e.g. through a change in land tenure) or remove demand entirely by displacing local communities (e.g. through resettlement). Across all of these cases, offsets (that achieve either NNL of biodiversity or ecosystem services) cause net losses to other non-traded outcomes (i.e. to ecosystem services or biodiversity, respectively) that are larger than those due to development alone. As a result, not only will offsets need to mitigate losses due to development, but also the additional losses due to trade-offs associated with the original offsets.

Synergies

Potential synergies exist when biodiversity and ecosystem services are positively related, i.e. an increase in biodiversity at the offset site results in an increase in ecosystem service, or vice versa. These include co-benefits, where, gains in biodiversity enhance the supply and benefits of ecosystem services. For example, vegetation clearing along a riparian buffer supplying sediment retention services and thus downstream drinking water, could be offset by revegetating further downstream where they equally contribute to the supply of those services. These synergies may either partially (Fig. 2e) or fully (Fig. 2f) mitigate the ecosystem services losses at the development site. Although, if these new services supply benefits to a different population they may not count as benefits to people in the NNL calculation. A focus of the carbon offset subfield investigates co-benefits of biodiversity and human wellbeing (Agrawal et al. 2011; Phelps et al. 2012). Similar findings have found ecosystem service co-benefits of biodiversity offsets, such as enhanced opportunities for nature-based recreation (Sonter et al. 2018). If synergies exist, fewer offsets (compared to “no links”), are needed to compensate the biodiversity and ecosystem services losses due to development.

Integrated offsets: Minimising trade-offs and enhancing synergies

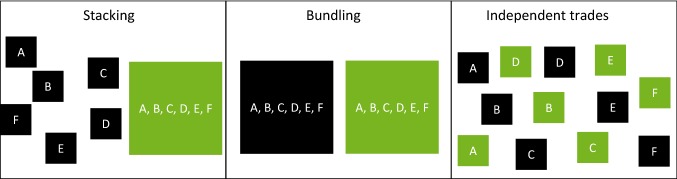

Once the potential links between biodiversity and ecosystem services are identified, three broad approaches exist to offset impacts of development on both: stacking, bundling and independent trades (Fig. 3). Policies often incorporate a mix of these approaches. Here, we discuss each approach and their implications for and ability to manage trade-offs and enhance synergies from offsetting for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Fig. 3.

Three approaches to offsetting biodiversity and ecosystem services. Black boxes are impact sites, green boxes are offset sites. The letter within each box represents a unique biodiversity components (e.g. a threatened species or ecosystem) or ecosystem services (e.g. carbon storage, water purification)

Credit stacking

Stacking refers to the case where a single offset can generate multiple sets of independent credits. The benefits the offset generates for (possibly multiple elements of) biodiversity as well as for one or more ecosystem services are separately estimated and accounted for, each being traded to offset an impact at a different place (Gardner and Fox 2013; Lee et al. 2013). This would require separate metrics for each type of biodiversity and ecosystem service benefit generated from the offset. Each set of credits could then be used separately to offset an equivalent loss elsewhere, so that one offset site could be providing credits for multiple impact sites, each of which has a different set of impacts that must be offset. This approach is exemplified by the New South Wales (Australia) Offset Policy for Major Projects, which permits a single site to generate carbon and biodiversity credits for sale separately (von Hase and Cassin 2018). The primary problem with stacking is that determining additionality becomes complex, because it is often unclear the extent to which the provision of one type of benefit is inseparable from the provision of another (Fox et al. 2011). For example, if an area is protected to offset biodiversity losses elsewhere, any ecosystem service benefits that arise from that protection are not additional, as once the site is deemed a biodiversity offset, those associated ecosystem service benefits occur regardless of whether they are then exchanged for equivalent losses elsewhere (von Hase and Cassin 2018). As such, ecosystem service benefits that are intrinsic to the biodiversity offset should not be able to be traded for ecosystem service losses from anywhere other than the place for which the original biodiversity offset was created (i.e. ‘bundling’, as per comprehensive bundling, below). However, there may be cases where clear additional action could be taken to generate extra ecosystem service credits on top of those intrinsic to the provision of the biodiversity offset at the site, and these additional credits could legitimately be traded separately.

Comprehensive bundling

Gains in biodiversity and ecosystem services from a given offset can also be comprehensively “bundled” into a single credit type (Deal et al. 2012; von Hase and Cassin 2018). One option here is to have a composite metric that combines the biodiversity and ecosystem service credits into a single currency. However, this can be problematic as it would inherently allow for trading between the different components of the metric (Maseyk et al. 2016) (although metrics can be constructed for multiple-criteria that do specifically limit trade-offs). The other approach would involve quantifying all losses from a given development to both biodiversity and ecosystem services via different metrics and then identifying an offset site and intervention(s) that could compensate fully for each of those losses. While it is possible in theory to achieve NNL of biodiversity and ecosystem services with this approach—as is the intention of US Wetland Mitigation Banking (Stein et al. 2000), especially where loss-gain calculations account for more than just wetland area, but also wetland function and services (e.g. as is the case in North Carolina) (von Hase and Cassin 2018)—comprehensive bundles at a single offset location that could offset all equivalent losses at an impact location are likely rare. This is particularly true given that achieving additional outcomes for biodiversity often involves restricting access or activities allowed on a site and thus may decrease the flow of benefits to people. Therefore, this approach may require offsets at multiple locations with different interventions, which then becomes more similar to the ‘independent trades’ approach described below. It should also be noted that even if bundled offsets achieve NNL goals, there is still potential for trade-offs to emerge if offsets cause losses to other biodiversity components and services not captured in the bundles, or if the amount or spatial location of demand for a given ecosystem service changes, for example, due to population growth or shifts.

Independent trades

The alternative to stacking and bundling is to account for each loss to biodiversity and ecosystem services at multiple sites and allow them to be offset independently across a range of offset and intervention sites (Tallis et al. 2015). In this case, the impacts of each offset on the other would need to be monitored, with any further losses to biodiversity or ecosystem services mitigated by additional offsets. This approach has the advantage of making accounting simpler, particularly if a comprehensive record of all losses and gains is maintained, revisited and updated periodically. It also does not sacrifice the achievement of additionality (a risk with stacking) or dilute gains in one objective to enhance those of others (as could happen with some forms of bundling). However, making independent trades forgoes opportunities for synergies, when some components of biodiversity and ecosystem services are positively linked. A judicious combination of bundling of some services (for which synergies are likely), and independent trades for the remainder, may therefore be the most effective approach.

Recommendations, remaining issues and research agenda

To minimise trade-offs and enhance synergies, offsets must consider both biodiversity and ecosystem services, and be designed and implemented following a comprehensive assessment of losses and gains that arise from both the development and offsetting plans. Of the approaches described above, the third (independent trades) is most likely to minimise trade-offs, as it is accounting for the supply, demand and flow of ecosystem services. Given the likely large additional financial costs to identify, minimise and mitigate these trade-offs, research can play an important role in helping to predict when trade-offs are likely to occur, which approaches work best to manage them and when additional issues may emerge.

One challenge relates to the lack of information on how biodiversity and ecosystem services link in an offsetting context. It will be important to understand how the subset of metrics included in biodiversity offsets (e.g. threatened species or habitat condition) relates to other non-traded ecosystem services outcomes (e.g. food provision). Studies in multiple locations are needed to understand circumstances leading them to co-vary and how variable these relationships can be with changing landscape contexts (Ricketts et al. 2016). Further, when biodiversity and ecosystem services are linked, it is critical to understand consequences of offsetting. For example, it would help to understand whether trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services due to offsets hold across spatial and temporal scales; the extent to which ecosystems and people themselves adjust and adapt to new conditions and how changes in the demand for ecosystem services affect outcomes. Answering these questions and obtaining a better understanding of links in an offsetting context, will provide a more mechanistic insight into when trade-offs are likely to emerge and which management approaches will work best.

Offsetting impacts on multiple objectives also has the potential to generate somewhat perverse incentives, if not carefully designed. Ecosystem services are multi-dimensional, including both the ecological supply of services and their benefits to people. Losses in benefits could be offset by removing the demand for them. For example, losses in crop pollination supplied by bee habitat could be offset by either creating new bee habitat, or relocating farmers elsewhere nearby existing bee habitat. In the latter, the supply of service provision declines when considering the set of impacted and offset areas, but there is still NNL in the benefits experienced by farmers. Many ecosystem services are also substitutable, where benefits are gained through investment in developing non-natural capital. For example, losses in crop pollination could be partially offset through the use of domesticated honey bees (although wild pollinator diversity remains important; Garibaldi et al. 2013). These solutions may provide more reliable gains or be more cost effective; however, they also obviate any associated biodiversity co-benefits of ecosystem services offsets. It is thus important to understand how links and trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services differ and how they can be measured considering different types of metrics, encompassing the quantification of ecosystem services supply, fluxes and benefits.

Finally, the validity of the mitigation hierarchy is challenged by integrating both ecosystem services and biodiversity into offsets. This process—most evident in the biodiversity offset subfield (as illustrated by our literature survey; see Appendix S1)—requires proponents to avoid, minimise, then rehabilitate, with offsetting only permitted for remaining losses (BBOP 2012). However, applying the mitigation hierarchy to multiple objectives is challenging and there may be situations where it can be ‘gamed’. For example, if an offset for biodiversity losses generates ecosystem services gains, this could reduce the incentive to avoid or minimise impacts on those services in the first place, as the claim could be made that they have been offset. This would undermine the application of the mitigation hierarchy, with potentially adverse implications for those people reliant on ecosystem service(s).

Conclusion

Offsetting activities increasingly target biodiversity and ecosystem services; however, the literature is currently scarce of guidance on how to identify and manage trade-offs that may emerge between these two objectives. While many challenges are shared among other conservation interventions, two are unique to offsetting activities: (1) trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services emerge from both the losses due to development and gains due to offsetting activities, and (2) unmanaged offsetting trade-offs may render them unsuccessful in achieving NNL (or other management) goals. Here, we present a novel conceptual framework to illustrate potential outcomes and have explored options for offset design in each case, and discuss three approaches to minimise trade-offs and enhance potential synergies. Assessing the potential for trade-offs is essential, as is designing offset schemes with this knowledge in hand; however, without a generalised understanding of which approach works best in different offsetting contexts, policies will not ensure biodiversity offsets do not negatively affect ecosystem services and offsets for ecosystem services do not negatively affect biodiversity. Therefore, we propose a series of remaining challenges that can help guide future research and identify additional problems that may emerge once offsets start to explicitly address and manage trade-offs between biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken during a workshop on “linking landscape structure to ecosystem services”, supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; n. 2017/50015-5), University of Queensland (UQ; Sprint 4/2016) and ARC Centre for Excellence in Environmental Decisions (CEED). LJS was supported by an ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE170100684). M.M. is supported by ARC Future Fellowship FT140100516.

Biographies

Laura J. Sonter

is a lecturer in Environmental Management and an ARC DECRA Research Fellow at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. Her research examines drivers of deforestation and consequences for ecosystems and people, and the impacts of conservation policies.

Ascelin Gordon

is a senior research fellow at RMIT University, Australia. His research focuses on quantitative approaches for conservation planning, conservation on private land and understanding the impacts of environmental policies on biodiversity.

Carla Archibald

is a Ph.D. student at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. Her research aims to inform conservation policy by examining how characteristics of conservation programmes influence their adoption and effectiveness.

Jeremy S. Simmonds

is a post-doctoral researcher at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. His research interests include conservation policy and the management of biodiversity in human-modified landscapes.

Michelle Ward

is a Ph.D. student at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. Her research interests include systematic conservation planning, cost-effective prioritisation strategies, impacts of dynamic threats, action mapping and political ecology.

Jean Paul Metzger

is a Professor at The University of São Paulo. His research interests include landscape fragmentation and connectivity, ecological thresholds and time-lag responses to landscape changes, conservation planning, relationships between landscape structure and ecosystems services, landscape restoration and environmental policy efficiency.

Jonathan R. Rhodes

is an Associate Professor at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. He is an applied ecologist working at the interface between ecology and policy to improve and better understand decision-making for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services.

Martine Maron

is a Professor at the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Queensland. Her research interests include avian ecology and conservation policy, particularly ecological compensation.

Author contributions

All authors designed the research and wrote the manuscript. CA, JSS and MW conducted the literature survey.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Laura J. Sonter, Email: l.sonter@uq.edu.au

Ascelin Gordon, Email: ascelin.gordon@rmit.edu.au.

Carla Archibald, Email: c.archibald@uq.edu.au.

Jeremy S. Simmonds, Email: j.simmonds1@uq.edu.au

Michelle Ward, Email: m.ward@uq.edu.au.

Jean Paul Metzger, Email: jpm@ib.usp.br.

Jonathan R. Rhodes, Email: j.rhodes@uq.edu.au

Martine Maron, Email: m.maron@uq.edu.au.

References

- Agrawal A, Nepstad D, Chhatre A. Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2011;36:373–396. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-042009-094508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman IJ, Harwood AR, Mace GM, Watson RT, Abson DJ, Andrews B, Binner A, Crowe A, et al. Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision-making: Land use in the United Kingdom. Science. 2013;341:45–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1234379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBOP . Standard on biodiversity offsets. Washington, DC: Business and Biodiversity Offsets Program; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Benayas JMR, Newton AC, Diaz A, Bullock JM. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: A meta-analysis. Science. 2009;325:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.1172460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaud C, Schreckenberg K, Jones JPG. The local costs of biodiversity offsets: Comparing standards, policy and practice. Land Use Policy. 2018;77:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaud C, Schreckenberg K, Rabeharison M, Ranjatson P, Gibbons J, Jones JPG. The sweet and the bitter: Intertwined positive and negative social impacts of a biodiversity offset. Conservation and Society. 2017;15:1–13. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.196315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budiharta S, Meijaard E, Gaveau DLA, Struebig MJ, Wilting A, Kramer-Schadt S, Niedballa J, Raes N, et al. Restoration to offset the impacts of developments at a landscape scale reveals opportunities, challenges and tough choices. Global Environmental Change. 2018;52:152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bull JW, Baker J, Griffiths VF, Jones JPG, Milner-Gulland EJ. Ensuring no net loss for people and biodiversity: Good practice principles. Oxford. 2018 doi: 10.31235/osf.io/4ygh7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bull JW, Gordon A, Law EA, Suttle KB, Milner-Gulland EJ. Importance of baseline specification in evaluating conservation interventions and achieving no net loss of biodiversity. Conservation Biology. 2014;28:799–809. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhard B, Kandzior M, Hou Y, Müller F. Ecosystem service potentials, flows and demand: Concepts for spatial localisation, indication and quantification. Landscape Online. 2014;34:1–32. doi: 10.3097/LO.201434. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvet C, Napoleone C, Salles JM. The biodiversity offsetting dilemma: Between economic rationales and ecological dynamics. Sustainability. 2015;7:7357–7378. doi: 10.3390/su7067357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chomitz KM. Baseline, leakage and measurement issues: How do forestry and energy projects compare? Climate Policy. 2002;2:35–49. doi: 10.3763/cpol.2002.0204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie AL, Orr BJ, Castillo Sanchez VM, Chasek P, Crossman ND, Erlewein A, Louwagie G, Maron M, et al. Land in balance: The scientific conceptual framework for land degradation neutrality. Environmental Science & Policy. 2018;79:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2017.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deal RL, Cochran B, LaRocco G. Bundling of ecosystem services to increase forestland value and enhance sustainable forest management. Forest Policy and Economics. 2012;17:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dee LE, De Lara M, Costello C, Gaines SD. To what extent can ecosystem services motivate protecting biodiversity? Ecology Letters. 2017;20:935–946. doi: 10.1111/ele.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Ram Adhikari J, et al. The IPBES conceptual framework: connecting nature and people. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2015;14:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro PJ. Counterfactual thinking and impact evaluation in environmental policy. New Directions for Evaluation. 2009;2009:75–84. doi: 10.1002/ev.297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Turner RK, Morling P. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecological Economics. 2009;68:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Gardner RC, Maki T. Stacking opportunities and risks in environmental credit markets. Environmental Law Reporter. 2011;41:10121–10125. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RC, Fox J. The legal status of environemtnal credit stacking. Ecology Law Quarterly. 2013;40:713–758. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi LA, Steffan-Dewenter I, Winfree R, Aizen MA, Bommarco R, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Carvalheiro LG, et al. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science. 2013;339:1608–1611. doi: 10.1126/science.1230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A, Langford WT, Todd JA, White MD, Mullerworth DW. Assessing the impacts of biodiversity offset policies. Environmental Modelling and Software. 2011;144:558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh S, Selman M. Comparing water quality trading programs: What lessons are there to learn? The Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy. 2012;42:104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths VF, Bull JW, Baker J, Milner-Gulland EJ. No net loss for people and biodiversity. Conservation Biology. 2018;33:76–87. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson LA, Bronmark C, Nilsson PA, Abjornsson K. Conflicting demands on wetland ecosystem services: Nutrient retention, biodiversity or both? Freshwater Biology. 2005;50:705–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2005.01352.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harper DJ, Quigley JT. A comparison of the areal extent of fish habitat gains and losses associated with selected compensation projects in Canada. Fisheries. 2005;30:18–25. doi: 10.1577/1548-8446(2005)30[18:ACOTAE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ICMM and IUCN. 2013. Independent report on biodiversity offsets. London, UK: International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Report prepared by The Biodiversity Consultancy, Cambridge, UK.

- IFC . Performance standard 6: Biodiversity conservation and sustainable management of living natural resources. Washington, DC: International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC et al. Climate change 2014: mitigation of climate change. In: Edenhofer O, et al., editors. Working group III contribution to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN . Policy on biodiversity offsets. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RB, Jobbágy EG, Avissar R, Roy SB, Barrett DJ, Cook CW, Farley KA, le Maitre DC, et al. Trading water for carbon with biological carbon sequestration. Science. 2005;310:1944–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.1119282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashof DA, Ahuja DR. Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature. 1990;344:529–531. doi: 10.1038/344529a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Lazarus M, Smith GR, Todd K, Weitz M. A ton is not always a ton: A road-test of landfill, manure, and afforestation/reforestation offset protocols in the US carbon market. Environmental Science & Policy. 2013;33:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2013.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Needham K, de Vries FP, Armsworth PR, Hanley N. Designing markets for biodiversity offsets: Lessons from tradable pollution permits. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2019;56:1429–1435. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mace GM, Norris K, Fitter AH. Biodiversity and ecosystem services: A multilayered relationship. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2012;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandle L, Tallis H, Sotomayor L, Vogl AL. Who loses? Tracking ecosystem service redistribution from road development and mitigation in the Peruvian Amazon. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2015;13:309–315. doi: 10.1890/140337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandle L, Douglass J, Sebsatian Lozano J, Sharp RP, Vogl AL, Denu D, Walschburger T, Tallis H. OPAL: An open-source software tool for integrating biodiversity and ecosystem services into impact assessment and mitigation decisions. Environmental Modelling and Software. 2016;84:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maron M, Brownlie S, Bull JW, Evans MC, von Hase A, Quetier F, Watson JEM, Gordon A. The many meanings of no net loss in environmental policy. Nature Sustainability. 2018;1:19–27. doi: 10.1038/s41893-017-0007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maron M, Ives CD, Kujala H, Bull JW, Maseyk FJF, Bekessy S, Gordon A, Watson JEM, et al. Taming a wicked problem: Resolving controversies in biodiversity offsetting. BioScience. 2016;66:489–498. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biw038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maron M, Rhodes JR, Gibbons P. Calculating the benefit of conservation actions. Conservation Letters. 2013;6:359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Maseyk FJF, Barea LP, Stephens RTT, Possingham HP, Dutson G, Maron M. A disaggregated biodiversity offset accounting model to improve estimation of ecological equivalency and no net loss. Biological Conservation. 2016;204:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott CL. REDDuced: From sustainability to legality to units of carbon—The search for common interests in international forest governance. Environmental Science & Policy. 2014;35:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MGE, Suarez-Castro AF, Martinez-Harms M, Maron M, McAlpine C, Gaston KJ, Johansen K, Rhodes JR. Reframing landscape fragmentation’s effects on ecosystem services. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2015;30:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekola JC, White PS. The distance decay of similarity in biogeography and ecology. Journal of Biogeography. 1999;26:867–878. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00305.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olander LP, Gibbs HK, Steininger M, Swenson JJ, Murray BC. Reference scenarios for deforestation and forest degradation in support of REDD: A review of data and methods. Environmental Research Letters. 2008;3:025011. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/3/2/025011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasgaard M, Sun Z, Mülle D, Mertz O. Challenges and opportunities for REDD+ : A reality check from perspectives of effectiveness, efficiency and equity. Environmental Science & Policy. 2016;63:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2016.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps J, Friess DA, Webb EL. Win-win REDD+ approaches belie carbon-biodiversity trade-offs. Biological Conservation. 2012;154:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quetier F, Lavorel S. Assessing ecological equivalence in biodiversity offset schemes: Key issues and solutions. Biological Conservation. 2011;144:2991–2999. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts TH, Watson KB, Koh I, Ellis AM, Nicholson CC, Posner S, Richardson LL, Sonter LJ. Disaggregating the evidence linking biodiversity and ecosystem services. Nature Communications. 2016;7:13106. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulp CJE, van Teeffelen AJA, Tucker G, Verburg PH. A quantitative assessment of policy options for no net loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services in the European Union. Land Use Policy. 2016;57:151–163. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Chavez HM, Schulp CJE, van Bodegom PM, Bouten W, Verburg PH, Davidson MD. A quantitative framework for assessing spatial flows of ecosystem services. Ecological Indicators. 2014;39:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soininen J, McDonald R, Hillebrand H. The distance decay of similarity in ecological communities. Ecography. 2007;30:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.04817.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonter LJ, Barrett DJ, Soares-Filho BS. Offsetting the impacts of mining to achieve no net loss of native vegetation. Conservation Biology. 2014;28:1068–1076. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonter LJ, Gourevitch J, Koh I, Nicholson CC, Richardson LL, Schwartz AJ, Singh NK, Watson KB, et al. Biodiversity offsets may forgo opporutnities to mitigate impacts on ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2018;16:143–148. doi: 10.1002/fee.1781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein ED, Tabatabai F, Ambrose RF. Wetland mitigation banking: A framework for crediting and debiting. Environmental Management. 2000;26:233–250. doi: 10.1007/s002670010084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallis H, Kennedy CM, Ruckelshaus M, Goldstein J, Kiesecker JM. Mitigation for one and all: An integrated framework for mitigation of development impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Environmental Impact Assessment Review. 2015;55:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2015.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venter O, Laurance WF, Iwamura T, Wilson KA, Fuller RA, Possingham HP. Harnessing carbon payments to protect biodiversity. Science. 2009;326:1368. doi: 10.1126/science.1180289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hase A, Cassin J. Theory and practice of ‘stacking’ and ‘bundling’ ecosystem goods and services: A resource paper. Washington, DC: Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme (BBOP). Forest Trends; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Watson KB, Galford GL, Sonter LJ, Koh I, Ricketts TH. Effects of human demand on conservation planning for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Conservation Biology. 2019;33:942–952. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.