Abstract

Usutu virus (USUV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus circulating in Western Europe that causes die-offs of mainly common blackbirds (Turdus merula). In the Netherlands, USUV was first detected in 2016, when it was identified as the likely cause of an outbreak in birds. In this study, dead blackbirds were collected, screened for the presence of USUV and submitted to Nanopore-based sequencing. Genomic sequences of 112 USUV were obtained and phylogenetic analysis showed that most viruses identified belonged to the USUV Africa 3 lineage, and molecular clock analysis evaluated their most recent common ancestor to 10 to 4 years before first detection of USUV in the Netherlands. USUV Europe 3 lineage, commonly found in Germany, was less frequently detected. This analyses further suggest some extent of circulation of USUV between the Netherlands, Germany and Belgium, as well as likely overwintering of USUV in the Netherlands.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Usutu virus (USUV) is a mosquito-borne arbovirus of the genus Flavivirus. The virus has a positive-stranded RNA genome with a genome length of around 11,000 nucleotides which encodes a single polyprotein. The polyprotein is processed by viral and host proteases into structural and non-structural proteins1. The life cycle of USUV involves mosquitoes (mainly Culex sp.2,3) as vectors and wild birds as the main amplifying hosts. Humans and other mammals can be infected by mosquito bites and are generally considered dead-end hosts. Recent studies revealed that USUV can also be detected in small mammals such as bats4, rodents and shrews5.

USUV was first identified from a Culex neavei mosquito in South Africa in 19596. Over subsequent decades, it was sporadically reported in several mosquito and bird species, and twice in a human patient with fever and rash in African countries7. USUV was for first identified in Europe in 2001, when it was determined to be the causative agent of a mass mortality event in several bird species in Austria8. This prompted retrospective analysis of archived tissue samples from dead wild birds in Italy in 1996, which revealed an earlier presence of the virus in Europe9. Our understanding of the USUV geographical range has since expanded to include the majority of European countries10, where outbreaks are marked by mass die-offs of wild birds, with the heaviest toll on common blackbird (Turdus merula) populations. In Germany, it has been demonstrated that five years after the first detection of USUV in the southwest of the country, circulation of the virus was associated with a 15.7% decline in the common blackbird population in USUV-suitable areas11.

The recent emergence of USUV epizootics among wild bird populations in Europe has been accompanied by reports of USUV infections in humans. Pathogenicity in humans appears to range from asymptomatic or mild symptoms, as shown in seroprevalence studies among healthy blood donors in Italy12, Germany13, Austria14 and the Netherlands15 to neuroinvasive infections associated with encephalitis or meningo-encephalitis, mainly in patients with underlying chronic disease or in immunocompromised patients, as described in Italy16–19, France20 and Croatia21. The number of human USUV cases described is very limited, but as it is likely that some clinical cases of acute USUV infection in humans remain remain undiagnosed, it is difficult to evaluate the real public health impact of USUV emergence in Europe at this stage. The circulation of USUV in birds can be linked to an increased human exposure to zoonotic risk. Indeed, the detection of viremic blood donations in the Netherlands co-incided with months of active USUV circulation in birds22, human cases described in Italy were from an area with demonstrated concomitant circulation of USUV in mosquitoes and birds16–19, and in Austria an increase in human cases was observed alongside the increased USUV activity in birds23.

Various USUV lineages are co-circulating in Europe4,24. In Germany, circulation of five different USUV lineages (Europe 2, Europe 3, Europe 5, Africa 2, and Africa 3) has been described25,26 and in France two lineages (Africa 2 and Africa 3) were detected in mosquitoes from the same region27,28. The co-circulation of different USUV lineages is thought to be due to independent introduction events to Europe by long-distance migratory birds from Africa, where different USUV lineages are presumed to be circulating, followed by local amplification and evolution leading to a geographical signal in phylogenetic analyses29. The assignment and nomenclature of USUV lineages are not standardized, and it is unclear if the lineages differ in their potential to be transmitted by mosquitoes and to infect or cause disease in different wild bird species and/or humans29.

In the Netherlands, USUV was first detected in 2016 when it was identified as the cause of an outbreak among blackbirds and captive great grey owls (Strix nebulosa)28,30. The virus circulated also in 2017 and 2018, and each late summer to autumn was associated with an increased die-off in blackbirds. Through a national wildlife disease surveillance programme, dead birds reported by citizens were collected, dissected and tissues were submitted for USUV diagnostics. To date, only a limited number of USUV genomes are available in the public domain, and it is unknown if USUV was already present in the Netherlands before 2016. In addition, it is unknown if there was a single introduction event or several independent introduction events, and – if so – what the geographic origin of the viruses is. Recent advances in third generation sequencing technologies have opened up new opportunities for infectious disease research. Pathogen genomics can be used to resolve crucial questions regarding origin, modes of transmission and ecology of emerging viral disease31–35. Therefore, we have sequenced 112 USUV genomes from blackbirds brain tissues on the Nanopore sequencing platform to analyse the emergence and spread of USUV throughout the Netherlands in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Results

USUV genomic sequencing

Between September 2016 and September 2018, 165 dead blackbirds were screened for the presence of USUV by RT-PCR. This screening resulted in 118 USUV positive birds and genomic sequences were generated with an USUV specific multiplex PCR using the Nanopore sequencing technology. Successful sequencing was defined as obtaining at least 80% of the USUV genome with a read coverage threshold of 100x per amplicon36. Near complete or complete viral genomes were recovered from 112 of 118 samples (Table 1). The median Ct value of the USUV positive brain tissues was 20, and the threshold for successful sequencing directly from brain tissue samples was shown to be around Ct value 32. Above this Ct value, only some amplicons were sequenced with a coverage >100x. An overview of the number of reads generated, the percentage of USUV reads and the proportion of successfully sequenced amplicons is displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the different USUV blackbird samples sequenced during this study.

| Sample ID | Accession number | Ct Value | Collection date | Location | USUV lineage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS201600034 | MN122145 | 19.45 | 01-09-16 | Gennep | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600036 | MN122146 | 15.38 | 06-09-16 | Andelst | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600042 | MN122147 | 14.21 | 07-09-16 | Venlo | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600045 | MN122148 | 14.97 | 07-09-16 | Lierop | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600048 | MN122149 | 19.74 | 07-09-16 | Lierop | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600051 | MN122150 | 21.44 | 07-09-16 | Ottersum | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600057 | MN122151 | 15.6 | 08-09-16 | Sint Agatha | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600060 | MN122152 | 19.75 | 12-09-16 | Zevenaar | Europe 3 |

| AS201600062 | MN122153 | 16.99 | 13-09-16 | Andelst | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600089 | MN122154 | 21.08 | 20-09-16 | Vlijmen | Europe 3 |

| AS201600095 | MN122155 | 19.78 | 21-09-16 | Klarenbeek | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600098 | MN122156 | 20.73 | 21-09-16 | Uden | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600101 | MN122157 | 20.34 | 22-09-16 | Beek en Donk | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600104 | MN122158 | 18.92 | 22-09-16 | Heino | Europe 3 |

| AS201600107 | MN122159 | 21.85 | 22-09-16 | Wernhout | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600110 | MN122160 | 24.21 | 22-09-16 | Reek | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600115 | MN122161 | 24.06 | 22-09-16 | Houten | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600118 | MN122162 | 21.02 | 22-09-16 | De Bilt | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600121 | MN122163 | 20.39 | 22-09-16 | Haarzuilens | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600124 | MN122164 | 23.8 | 23-09-16 | Westervoort | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600127 | MN122165 | 17.47 | 23-09-16 | Deventer | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600133 | MN122166 | 22.59 | 23-09-16 | Overdinkel | Europe 3 |

| AS201600136 | MN122167 | 16.99 | 23-09-16 | Arnhem | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600148 | MN122168 | 24.79 | 23-09-16 | Nieuwegein | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600173 | MN122169 | 20.33 | 07-10-16 | Doetichem | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600197 | MN122170 | 20.13 | 11-10-16 | Reimerswaal | Europe 3 |

| AS201600203 | MN122171 | 32.01 | 05-10-16 | Lelystad | Europe 3 |

| AS201600221 | MN122172 | 19.95 | 22-09-16 | Haarzuilens | Europe 3 |

| AS201600227 | MN122173 | 26.23 | 30-09-16 | Hilversum | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600241 | MN122174 | 20.16 | 27-09-16 | Midden-Drenthe | Europe 3 |

| AS201600244 | MN122175 | 18.89 | 27-09-16 | Zutphen | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600247 | MN122176 | 14.07 | 30-09-16 | Terneuzen | Europe 3 |

| AS201600253 | MN122177 | 21.51 | 27-09-16 | Landgraaf | Europe 3 |

| AS201600265 | MN122178 | 16.48 | 30-09-16 | Enschede | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600268 | MN122179 | 16.72 | 30-09-16 | Nederlek | Europe 3 |

| AS201600274 | MN122180 | 21.11 | 27-09-16 | streek De Liemers | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600277 | MN122181 | 17.43 | 27-09-16 | De Ronde Venen | Europe 3 |

| AS201600280 | MN122182 | 21.87 | 26-09-16 | Ingen | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600281 | MN122183 | 14.07 | 25-09-16 | Langbroek | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600283 | MN122184 | 19.94 | 27-09-16 | Oss | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201600284 | MN122185 | 20.09 | 03-10-16 | Oss | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600286 | MN122186 | 28.48 | 28-09-16 | Oss | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201600287 | MN122187 | 14.46 | 27-09-16 | Schaik | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201700024 | MN122188 | 19.88 | 11-04-17 | Westvoort | Europe 3 |

| AS201700077 | MN122189 | 16.8 | 03-07-17 | Best | Europe 3 |

| AS201700080 | MN122190 | 19.6 | 05-07-17 | Bilthoven | Europe 3 |

| AS201700084 | MN122191 | 16.6 | 05-07-17 | Bunnik | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700086 | MN122192 | 18.3 | 11-07-17 | Best | Europe 3 |

| AS201700087 | MN122193 | 17 | 11-07-17 | Zutphen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700090 | MN122194 | 13.9 | 13-07-17 | Doetinchem | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700096 | MN122195 | 14.4 | 14-07-17 | Rosmalen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700103 | MN122196 | 22.7 | 19-07-17 | Gemonde | Europe 3 |

| AS201700106 | MN122197 | 23.8 | 25-07-17 | Soest | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700109 | MN122198 | 25.2 | 25-07-17 | Bennekom | Europe 3 |

| AS201700112 | MN122199 | 18 | 27-07-17 | Enschede | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700118 | MN122200 | 22 | 03-08-17 | Huizen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700121 | MN122201 | 27.8 | 01-08-17 | Koekange | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201700124 | MN122202 | 16.4 | 01-08-17 | Enschede | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700127 | MN122203 | 26.6 | 30-07-17 | Grenspad | Europe 3 |

| AS201700130 | MN122204 | 20.5 | 16-08-17 | Lelystad | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700152 | MN122205 | 24.98 | 19-07-17 | IJsselstein | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700155 | MN122206 | 15.13 | 10-08-17 | Almere | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201700167 | MN122207 | 29.27 | 01-09-17 | Almere | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700170 | MN122208 | 26.03 | 25-08-17 | Almere | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700174 | MN122209 | 22.72 | 29-08-17 | Utrecht | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700177 | MN122210 | 21.85 | 15-09-17 | Epe | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700186 | MN122211 | 23.93 | 13-09-17 | Zoeterwoude | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201700189 | MN122212 | 16.52 | 14-09-17 | Eext | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201700248 | MN122213 | 23.65 | 20-09-17 | Hardinxveld-Giessendam | Europe 3 |

| AS201700254 | MN122214 | 17.92 | 22-09-17 | Hilversum | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800038 | MN122215 | 17.75 | 11-09-17 | Eastermar | Europe 3 |

| AS201800081 | MN122216 | 17.69 | 27-07-18 | Naarden | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800082 | MN122217 | 20.39 | 27-07-18 | Naarden | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800084 | MN122218 | 27.04 | 31-07-18 | Spijk (West Betuwe) | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800086 | MN122219 | 27.86 | 01-08-18 | Middelburg | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800087 | MN122220 | 21.72 | 01-08-18 | Wierden | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800088 | MN122221 | 18.60 | 01-08-18 | Losser | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800089 | MN122222 | 22.61 | 02-08-18 | Rijswijk | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800090 | MN122223 | 28.02 | 02-08-18 | Ermelo | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800091 | MN122224 | 17.73 | 02-08-18 | Ermelo | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800092 | MN122225 | 23.42 | 02-08-18 | Rotterdam | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800093 | MN122226 | 19.40 | 03-08-18 | Leiden | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800094 | MN122227 | 20.94 | 03-08-18 | Bilthoven | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800095 | MN122228 | 23.58 | 06-08-18 | Middelburg | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800097 | MN122229 | 28.93 | 03-08-18 | Oldambt | Europe 3 |

| AS201800099 | MN122230 | 22.52 | 07-08-18 | Noordosterpolder | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800100 | MN122231 | 20.24 | 07-08-18 | Venlo | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800101 | MN122232 | 27.4 | 07-08-18 | Tynaarlo | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800102 | MN122233 | 20.81 | 09-08-18 | Noordenveld | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800103 | MN122234 | 22.19 | 10-08-18 | Raalte | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800112 | MN122235 | 16.36 | 14-08-18 | Boekel | Europe 3 |

| AS201800113 | MN122236 | 15.97 | 14-08-18 | Westland | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800114 | MN122237 | 22.70 | 15-08-18 | Noordoostpolder | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800115 | MN122238 | 23.17 | 15-08-18 | Midden Groningen | Africa 3.1 |

| AS201800116 | MN122239 | 17.15 | 16-08-18 | Groningen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800118 | MN122240 | 25.68 | 16-08-18 | Den Haag | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800120 | MN122241 | 22.09 | 17-08-18 | Utrechtse Heuvelrug | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800121 | MN122242 | 17.80 | 17-08-18 | Heerenveen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800122 | MN122243 | 21.00 | 21-08-18 | Tytsjerksteradiel | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800123 | MN122244 | 20.02 | 21-08-18 | Tytsjerksteradiel | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800125 | MN122245 | 25.03 | 22-08-18 | Westerveld | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800126 | MN122246 | 24.00 | 22-08-18 | Hardenberg | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800127 | MN122247 | 25.07 | 22-08-18 | Groningen | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800128 | MN122248 | 15.74 | 22-08-18 | Zuidhorn | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800129 | MN122249 | 21.44 | 23-08-18 | Lochem | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800150 | MN122250 | 23.67 | 30-08-18 | Bloemendaal | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800151 | MN122251 | 24.42 | 30-08-18 | Bloemendaal | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800152 | MN122252 | 20.87 | 30-08-18 | Bloemendaal | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800154 | MN122253 | 17.26 | 31-08-18 | Oldenbroek | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800155 | MN122254 | 16.16 | 31-08-18 | Heerhugowaard | Africa 3.2 |

| AS201800156 | MN122255 | 17.99 | 31-08-18 | Bosch en Duin | Africa 3.3 |

| AS201800157 | MN122256 | 22.89 | 04-09-18 | Borger-Odoorn | Africa 3.3 |

Phylogenetic analysis of USUV in the Netherlands

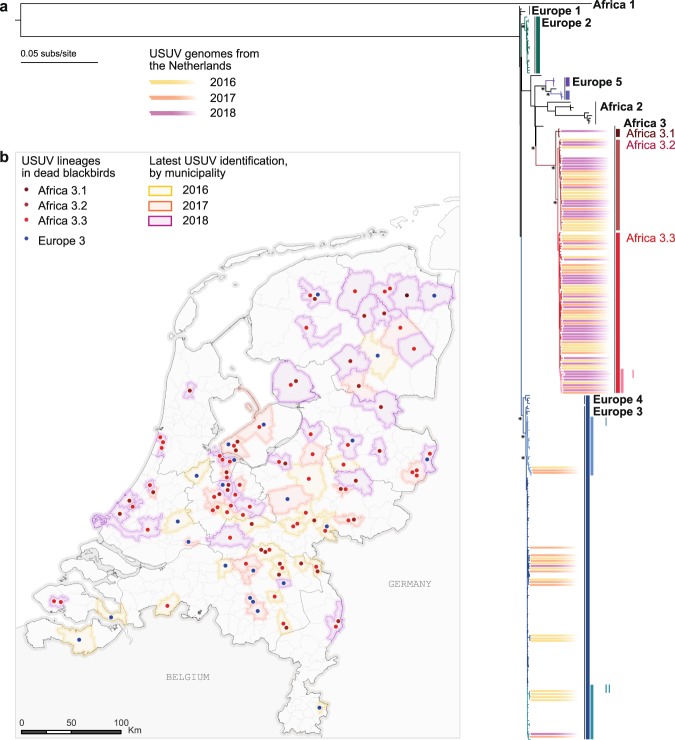

Phylogenetic analysis revealed the co-circulation of USUV lineages Europe 3 and Africa 3 in the Netherlands (Fig. 1), with Africa 3 lineage viruses most frequently detected. The USUV lineage Africa 3 has been previously detected in Germany but not as major variant (9 of the 108 published whole genomes). USUV from blackbirds in the Netherlands are at this stage considered the most numerous within this lineage. In contrast, while the Europe 3 lineage was most commonly found to be associated with blackbird deaths in Germany between 2011 and 2016, this lineage appears to be less frequently detected in the Netherlands. Viruses belonging to the Europe 3 lineage formed several groups which were interspersed with viruses found in neighbouring countries. The two lineages were shown to co-circulate in the Netherlands during 3 consecutive years. In all three years, Africa 3 lineage viruses were more frequently detected (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis and geographic distribution of USUV strains detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands. (a) Maximum likelihood phylogeny of USUV complete coding sequences. PhyCLIP’s cluster designation is indicated in colour and asterisk indicate bootstrap scores ≥80%. (b) Geographic distribution of USUV clusters detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands. Dots indicate the center of municipality at which USUV positive dead birds were collected. In municipalities where more than one dead blackbird were collected, dots are dispersed and the municipality is colored according to year of most recent death. Scale bar represents units of substitutions per site.

Table 2.

Overview of the presence of the different USUV lineage during 2016–2018.

| USUV Africa 3 (%) | USUV Europe 3 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 30 (69.8%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| 2017 | 19 (65.5%) | 10 (34.5%) |

| 2018 | 39 (95.1%) | 2 (4.9%) |

These differences in phylogenetic signal strongly suggests differences in the emergence of these two lineages in the Netherlands, with continuous circulation of the Africa 3 lineage and repeated introductions of viruses from the Europe 3 lineage. However, systematic sequencing of a representative set of samples from birds from other parts of Europe in the same time period is needed to resolve this question.

PhyCLIP37, a statistically-principled approach to delineate phylogenetic trees into clusters, was used to resolve the phylogenetic clustering of USUV (Fig. 1). PhyCLIP showed that the Africa 3 lineage can be divided into 3 different clusters: (1) a cluster comprising 3 sequences from Germany from 2016 and 1 sequence from the Netherlands from 2018 (2) a cluster comprising 32 USUV sequences detected in the Netherlands between 2016–2018, as well as 3 USUV sequences detected in Germany in 2014 and 2016, and (3) a cluster comprising 55 sequences detected in the Netherlands in 2016–2018 and 4 sequences detected in Germany and Belgium in 2015–2016, in this cluster 10 sequences could further be delineated into a nested sub-cluster. Delineation of these 3 clusters and the nested sub-cluster of the Africa 3 lineage does not appear to be structured over time (Fig. 2). Furthermore, sequences from the Netherlands from clusters Africa 3.2 and Africa 3.3 have been detected from across the country each year, while cluster USUV Africa 3.1 was only detected once in 2018. PhyCLIP delineated the Europe 3 USUV lineage as one clade with two different sub-clusters: (I) a sub-cluster with sequences detected in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands in 2011–2017 and (II) a sub-cluster detected in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands in 2011–2018. Also for the Europe 3 lineage, delineation of the sub-clusters does not appear to be structured over time. Four sequences from blackbirds and mosquitos detected in Italy that were previously classified as a distinct clade, Europe 424, were classified by PhyCLIP within the Europe 3 lineage.

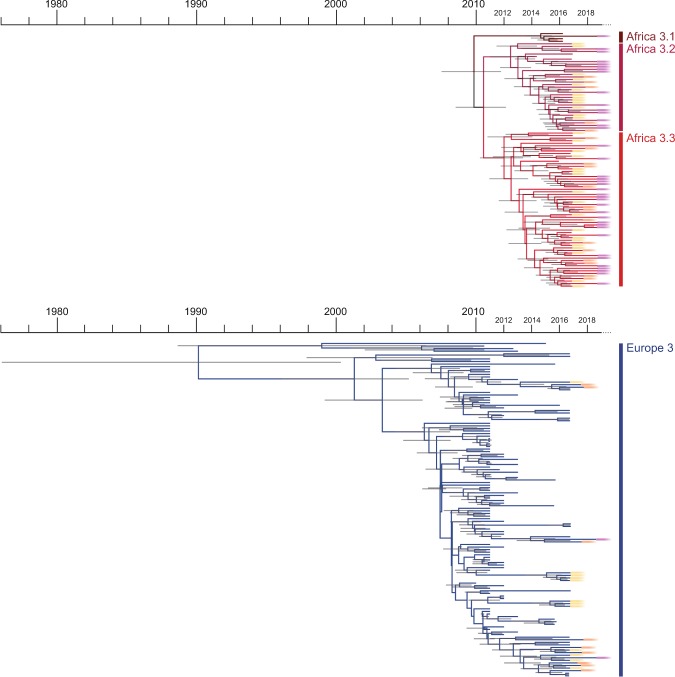

Figure 2.

Molecular clock phylogeny of the complete coding sequences of USUV lineages detected in dead blackbirds from the Netherlands. Annotations correspond to clusters designed by PhyCLIP. Node bars indicate 95% confidence intervals of the time of the most common ancestor.

Apart from the Europe 3 lineage and the 3 clusters within the Africa 3 lineage, PhyCLIP identified 3 additional clusters. The Europe 2 lineage, which consists of sequences identified in humans, blackbirds and mosquitos in Italy, Austria and Hungary between 2001 and 2017, was recognized as a cluster. PhyCLIP delineated two higher resolution clusters from the Europe 5 lineage, the first consisting of sequences from mosquitos in Israel from 2004, the second consisting of sequences from mosquitos in Israel from 2015. Several USUV sequences could not be classified into clusters. This suggests that more lineages might be circulating, but that the number of sequences available at the moment is too limited to enable delineation into clusters by PhyCLIP.

An overview of the geographical distribution of the USUV clusters detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands is displayed in Fig. 1 and in the Supplementory Movie. The first set of dead blackbirds positive for USUV collected in September 2016, were found in 10 of 12 different provinces, indicating already widespread circulation at the time of detection. The USUV identified from this first set were genetically diverse and each of the four USUV clusters identified in the Nertherlands were already present at that time. The different USUV clusters all have a widespread geographic distribution throughout the Netherlands.

Molecular clock phylogeny of USUV lineages detected in the netherlands

BEAST analysis was performed to determine the time to most recent common ancestor of the USUV Africa 3 and Europe 3 lineages, both detected in the Netherlands. Separate BEAST analyses were performed for each of the two lineages. The estimated time to the most recent common ancestor of lineage Africa 3 was shown to be around 2009 (between 2007–2012, 95% confidence interval). The estimated time to the most recent common ancestor of the Europe 3 lineage, encompassing USUV sequences from the Netherlands, was shown to be around 2002 (1996–2006, 95% confidence interval).

Discussion

The emergence of USUV in Europe is causing massive die-offs of mainly common blackbirds. Besides being of concern for wildlife conservation, the occurrence of numerous and sustained outbreaks in wildlife should be considered as a serious warning signal from the perspective of surveillance for zoonotic pathogens. The increasing numbers of reports of asymptomatic human USUV infections as well as cases of mild to severe neuroinvasive USUV infections in humans may be due to changes in awareness and surveillance but may also be an effect of increased human exposure to this zoonotic risk. Dense genomic monitoring of viral pathogens supports outbreak investigations by providing insights to paterns of transmission. Since USUV was only recently recognized in the Netherlands, we used genomic sequencing to gain insight in how this emerging arbovirus spread and evolve in a previously naïve population. We describe the genetic characterization of USUV genomes from tissue samples from dead blackbirds in the Netherlands throughout 3 consecutive years. An amplicon-based sequencing approach using Nanopore sequencing was used to monitor the genetic diversity of USUV36. This protocol proved to be sensitive enough to sequence the vast majority of tissue samples from dead blackbird surveillance. This study shows that genomic sequencing on the Nanopore platform is a powerfull approach for monitoring and tracing ongoing arbovirus infections in dead wildlife.

The USUV Africa 3 lineage was found to be predominantly circulating in the Netherlands. Furthermore, divergence inside this lineage was shown to justify its division into 3 higher resolution clusters. The absence of clear temporal delineation in the phylogeny of the USUV Africa 3 lineage could indicate that subsequent to the first identification of USUV in the Netherlands in 2016, the outbreaks in 2017 and 2018 were more likely caused by USUV lineages that persisted during winter in the Netherlands, rather than by repeated introduction of USUV strains from areas outside the Netherlands. It remains unclear if and how USUV can persist in the Netherlands during winter time, whether through vertical tranmission in mosquitoes, maintainance in birds or overwintering mosquitoes, or if it remains present in other animal species. Therefore, extending the diversity of species included in USUV surveillance efforts would be a useful consideration. A recent study in Germany also showed an increase in the detection of the USUV Africa 3 lineage in 2017 and 201826, however only partial sequence data is available and more genetic information is needed before it can accurately be used in phylogenetic analysis. The results differed for the USUV Europe 3 lineage: this lineage was less frequently detected in the Netherlands, and sequences from the Netherlands were interspersed with viruses from Germany and Belgium. The reason for this is unknown but might suggest that the USUV Europe 3 lineage – unlike the USUV Africa 3 lineage – is not enzootic in the Netherlands but periodically introduced from neighbouring countries.

USUV was detected in the Netherlands through bird mortality in 2016, but the most recent common ancestors of both the Africa 3 lineage and Europe 3 lineage are estimated to be well before the initial detection. The two time windows identified are broad, and more data from other regions and previous years has to be produced to generate more precise estimates. However, this information, taken together with the described diversity of USUV detected in the Netherlands since the beginning of the outbreak in September 2016, suggests limited circulation of different USUV lineages in the Netherlands before its initial detection. USUV circulation may have been boosted in 2016 by favourable environmental conditions for mosquitoes28,30. Alternatively, several introductions from neighbouring countries could have occurred close to the date of first detection and spread efficiently with these favourable conditions. Phylogenetic and molecular clock analyses conducted for the reconstrution of the Zika virus epidemic in the Americas have estimated the time of introduction of Zika virus more than a year before it was detected through human-disease surveillance35. It is unclear whether blackbird mortality associated with USUV infection did not occur prior to 2016 or whether it occurred at levels that did not prompt detection through citizen science-based alerting system. In October 2012, 66 songbirds, including 34 blackbirds, were found dead throughout the Netherlands but all tested negative for USUV38. Serological testing of a small number of serum samples from birds in the Netherlands in 2015 did show a seroprevalence of 2.8% for USUV; however, the positive birds consisted of species that are partially migratory and therefore this result does not necessarly indicate local circulation of the virus at that time39. Retrospective testing of other samples for the presence of USUV may help to elucidate this. In addition, care has to be taken with the interpretation of the BEAST analysis since recently it was shown that by sequencing an ancient hepatitis B virus the evolutionary rate of the virus has shown to be different than previously thought40. To date, only very recent data on USUV is available and we do not know how the virus behaves over a prolonged period of time.

Several USUV sequences remained unclassified by the statistically-principled approach for phylogenetic clustering (PhyCLIP37). This indicates that more lineages might be present, but that the amount of genetic data available is at the moment too limited to enable accurate phylogenetic clustering. In addition, by adding a large amount of sequences to the public database, the genomic information currently available is very skewed towards the USUV strains circulating in the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Recent identification and generation of USUV genomic data outside Europe (Senegal5 and Israel41) have had an important impact on the understanding of the global USUV diversity. To get a better overview of USUV diversity in Europe and a better understanding of USUV evolution, it is important that more sequence data is generated from other countries. Given the detection of USUV in the Netherlands, it is important to identify the vector competence in local mosquitos, although a previous studie has already shown the vector competence in the Culex pipiens mosquito which is present in the Netherlands3.

This study describes a proactive investigation of USUV emergence and spread in the Netherlands through a national wildlife disease scanning surveillance programme associated with the application of a protocol enabling fast and accurate complete genome sequencing of USUV on the Nanopore platform. We add knowledge relating to the USUV epidemiology and describe the genomic diversity profile of USUV circulating in the country. Our analysis suggests that USUV is likely circulating between neighboring countries in Western Europe, where it has been established and is overwintering. We report an important genomic diversity of the viruses circulating in the Netherlands, observable already at the time of the first identifications of USUV in the country. We highlight issues of bias in surveillance, as well as the possibility of eventual silent circulation of the virus in European countries preceding epizootics detection. Another virus circulating in Europe, West-Nile virus, has antigenic cross-reactivity, similar transmission cycle and may interact at population level with USUV42. With the first report of West Nile virus in Germany in 201843, the detection of authochthonous West Nile virus in the Netherlands is likely a matter of time. The readily established dead wildlife disease surveillance programme presented here and the expansion of the described protocol for sequencing on the Nanopore platform to West Nile virus should in this scenario allow for the real time monitoring of eventual reciprocal interaction in the dynamics of West Nile virus.

Methods

Dead blackbirds surveillance

Mortality in blackbirds was reported through a citizen science-based alerting system. For a selection of the cases reported, dead blackbirds were collected, autopsy was performed, and brain tissues were sampled for USUV diagnostics if autopsy indicated USUV as the possible cause of death until the first detection of USUV in 201630, and systematically afterwards. The selection was based on freshness of the carcasses and on geographic location, with oversampling at locations where USUV activity had not been identified by then. Therefore, the sampling reflects the edges of observed bird mortality rather than the local evolution of the virus over time. Locations where dead blackbirds were found were registered by municipality, and date of death was based on the date of the sample collection.

Usutu virus diagnostics

Tissue from dead blackbirds was homogenized using the Fastprep bead beater (4.0 m/s for 20 seconds). Samples were spun down for 10 minutes at 10.000 xg after which Phocine distemper virus (PDV) was added as internal NA extraction control to the supernatant and total NA was extracted from the supernatant using the Roche MagNA Pure. The NA was screened for the presence of USUV using real-time PCRs described by Nicolay et al.44 and Jost et al.45, in duplex with PDV.

Multiplex PCR for nanopore sequencing

The multiplex PCR for MinION sequencing was performed as previously described36. In short, random primers (Invitrogen) were used to perform reverse transcription using ProtoScript II (NEB, cat. no. E6569) after which USUV specific multiplex PCR was performed in 2 reactions using Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB, cat no. M0493). Nanopore sequencing was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions using the 1D Native barcoding genomic DNA Kit (Nanopore, EXP-NBD103 and SQK-LSK108) on a FLO-MIN106 flowcell. A total of 12 or 24 samples were multiplexed per sequence run.

Data analysis MinION sequencing

Raw sequence data was demultiplexed using Porechop (https://github.com/rrwick/porechop). Primers were trimmed and reads were quality controlled to a minimal length of 150 and a median PHRED score of 10 using QUASR46. A reference based alignment against an arbitrary chosen Usutu virus genome was performed in Geneious47 or in CLC Genomic Workbench 11.0 (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/). The consensus genome was extracted and compared to the non-redundant database using Blastn48. The most closely related sequence was selected and used for a second reference based alignment using the quality controlled reads. The consensus genome was extracted and positions with a coverage <100 were replaced with an “N”. This threshold was set based on a recent publication demonstrating that by using this threshold the quality of full genomes is very high (one position per 106 USUV whole genomes sequences sequenced is called erroneously)36. Homopolymeric regions were manually checked and resolved consulting the closest reference genome.

Phylogenetic analysis

All available full length USUV genomes were retrieved from GenBank49 on 12 February 2019 and aligned with the newly obtained USUV sequences using MUSCLE50. Sequences with >20% “Ns” were not included in the phylogenetic analysis. The alignment was manually checked for discrepancies after which IQ-TREE51 was used to perform maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis under the GTR + I + G4 model as best predicted model using the ultrafast bootstrap option with 1,000 replicates.

PhyCLIP

PhyCLIP37 was used to delineate the phylogenetic tree in clusters. The default settings for intermediate-resolution clustering were used with the recommended range of input parameters to determine the optimal parameters: S = 3–10 (increasing by 1), FDR = 0.05–0.20 (increasing by 0.05) and gamma = 1–3 (increasing by 0.5).

BEAST analysis

Bayesian phylogenetic trees were inferred using BEAST v1.10.352. The HKY site model was used with 4 gamma categories with 3 partition into codon positions to generate an uncorrelated relaxed molecular clock. The tree prior was set to exponential growth and random sampling for the Africa 3 lineage and to constant size for the Europe 3 lineage. MCMC was set to 80,000,000 generations for both lineages. Log files were analyzed in Tracer v1.7.1 to check if ESS values were beyond threshold (>200). Tree annotator v1.8.4 was used with 10% burnin and median node heights. The tree was annotated and visualized using FigTree53.

Geographical distribution of USUV strains detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands

The map was created using ArcGIS 10.6 software (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA) (http://www.esri.com/) and uses the datasets Gemeentegrenzen 2019 and Provinciegrenzen 2019 by ESRI Nederland (services.arcgis.com) for administrative boundaries.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Movie: Geographic distribution of USUV strains detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands.

Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 643476 (COMPARE) and by the ZonMW Eco-Alert project. The general wildlife disease surveillance programme was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and Utrecht University (grants 1200022600/2016, 1300024982/2017 and 1300027028/2018).

Author contributions

B.B.O.M., E.M., R.K., A.v.d.L., C.M.E.S. performed the sequence library preparations and sequencing. B.B.O.M., E.M. and D.F.N. performed the data analysis. H.v.d.J., M.K. and J.R. were involved in sample collection. C.B.E.M.R. and M.K. conceived the study. B.B.O.M., E.M., C.B.E.M. and M.K. wrote the paper with help from the other authors.

Data availability

The genomic sequences of the Usutu viruses sequenced in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MN122145 – M122256.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: B. Bas Oude Munnink, E. Münger, C. B. E. M. Reusken and M. Koopmans.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-59692-y.

References

- 1.Pauli G, et al. Usutu virus. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2014;41:73–82. doi: 10.1159/000357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camp JV, Kolodziejek J, Nowotny N. Targeted surveillance reveals native and invasive mosquito species infected with Usutu virus. Parasit. Vectors. 2019;12:46. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3316-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fros JJ, et al. Comparative Usutu and West Nile virus transmission potential by local Culex pipiens mosquitoes in north-western Europe. One Heal. 2015;1:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadar D, et al. Usutu virus in bats, Germany, 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1771–3. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diagne M, et al. Usutu Virus Isolated from Rodents in Senegal. Viruses. 2019;11:181. doi: 10.3390/v11020181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams MC, Simpson DIH, Haddow AJ, Knight EM. The Isolation of West Nile Virus from Man and of Usutu Virus from the Bird-Biting Mosquito Mansonia Aurites (Theobald) in the Entebbe Area of Uganda. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1964;58:367–374. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1964.11686258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolay B, Diallo M, Boye CSB, Sall AA. Usutu Virus in Africa. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1417–1423. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissenböck H, et al. Emergence of Usutu virus, an African Mosquito-Borne Flavivirus of the Japanese Encephalitis Virus Group, Central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:652–656. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.020094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weissenböck H, Bakonyi T, Rossi G, Mani P, Nowotny N. Usutu Virus, Italy, 1996. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:274–277. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.121191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Y, et al. Evaluating the risk for Usutu virus circulation in Europe: comparison of environmental niche models and epidemiological models. Int J Heal. Geogr. 2018;17:35. doi: 10.1186/s12942-018-0155-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lühken R, et al. Distribution of Usutu Virus in Germany and Its Effect on Breeding Bird Populations. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1994–2001. doi: 10.3201/eid2312.171257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierro A, et al. Detection of specific antibodies against West Nile and Usutu viruses in healthy blood donors in northern Italy, 2010–2011. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013;19:E451–E453. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cadar D, et al. Blood donor screening for West Nile virus (WNV) revealed acute Usutu virus (USUV) infection, Germany, September 2016. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22:30501. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.14.30501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakonyi, T. et al. Usutu virus infections among blood donors, Austria, July and August 2017 – Raising awareness for diagnostic challenges. Eurosurveillance22, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Zaaijer Hans L., Slot Ed, Molier Michel, Reusken Chantal B.E.M., Koppelman Marco H.G.M. Usutu virus infection in Dutch blood donors. Transfusion. 2019;59(9):2931–2937. doi: 10.1111/trf.15444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecorari, M. et al. First human case of Usutu virus neuroinvasive infection, Italy, August-September 2009. Euro Surveill. 14, (2009). [PubMed]

- 17.Cavrini, F. et al. Usutu virus infection in a patient who underwent orthotropic liver transplantation, Italy, August-September 2009. Euro Surveill. 14, (2009). [PubMed]

- 18.Cavrini F, et al. A rapid and specific real-time RT-PCR assay to identify Usutu virus in human plasma, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Virol. 2011;50:221–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grottola A, et al. Usutu virus infections in humans: a retrospective analysis in the municipality of Modena, Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017;23:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simonin Y, et al. Human Usutu Virus Infection with Atypical Neurologic Presentation, Montpellier, France, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:875–878. doi: 10.3201/eid2405.171122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santini M, et al. First cases of human Usutu virus neuroinvasive infection in Croatia, August–September 2013: clinical and laboratory features. J. Neurovirol. 2015;21:92–97. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaaijer Hans L., Slot Ed, Molier Michel, Reusken Chantal B.E.M., Koppelman Marco H.G.M. Usutu virus infection in Dutch blood donors. Transfusion. 2019;59(9):2931–2937. doi: 10.1111/trf.15444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aberle SW, et al. Increase in human West Nile and Usutu virus infections, Austria, 2018. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23:1800545. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.43.1800545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calzolari M, et al. Co-circulation of two Usutu virus strains in Northern Italy between 2009 and 2014. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;51:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieg Michael, Schmidt Volker, Ziegler Ute, Keller Markus, Höper Dirk, Heenemann Kristin, Rückner Antje, Nieper Hermann, Muluneh Aemero, Groschup Martin H., Vahlenkamp Thomas W. Outbreak and Cocirculation of Three Different Usutu Virus Strains in Eastern Germany. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2017;17(9):662–664. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2016.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michel F, et al. Evidence for West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus Infections in Wild and Resident Birds in Germany, 2017 and 2018. Viruses. 2019;11:674. doi: 10.3390/v11070674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eiden M, et al. Emergence of two Usutu virus lineages in Culex pipiens mosquitoes in the Camargue, France, 2015. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018;61:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cadar, D. et al. Widespread activity of multiple lineages of Usutu virus, Western Europe, 2016. Eurosurveillance 22, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Engel D, et al. Reconstruction of the Evolutionary History and Dispersal of Usutu Virus, a Neglected Emerging Arbovirus in Europe and Africa. MBio. 2016;7:e01938–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01938-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rijks, J. M. et al. Widespread Usutu virus outbreak in birds in The Netherlands, 2016. Eurosurveillance 21, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Faria NR, et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science. 2016;352:345–349. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill SC, et al. Early Genomic Detection of Cosmopolitan Genotype of Dengue Virus Serotype 2, Angola, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:784–787. doi: 10.3201/eid2504.180958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faria NR, et al. Genomic and epidemiological monitoring of yellow fever virus transmission potential. Science (80-.). 2018;361:894–899. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naveca FG, et al. Genomic, epidemiological and digital surveillance of Chikungunya virus in the Brazilian Amazon. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019;13:e0007065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faria NR, et al. Establishment and cryptic transmission of Zika virus in Brazil and the Americas. Nature. 2017;546:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature22401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oude Munnink BB, et al. Towards high quality real-time whole genome sequencing during outbreaks using Usutu virus as example. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;73:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han, A. X., Parker, E., Scholer, F., Maurer-Stroh, S. & Russell, C. A. Phylogenetic Clustering by Linear Integer Programming (PhyCLIP). bio Rxiv 446716. 10.1101/446716 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Reusken C, et al. No proof for usutuvirus as cause of death in songbirds in the Netherlands (fall 2012) Tijdschr. Diergeneeskd. 2014;139:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim SM, et al. Serologic evidence of West Nile virus and Usutu virus infections in Eurasian coots in the Netherlands. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65:96–102. doi: 10.1111/zph.12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mühlemann B, et al. Ancient hepatitis B viruses from the Bronze Age to the Medieval period. Nature. 2018;557:418–423. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannasse B, et al. Usutu Virus RNA in Mosquitoes, Israel, 2014–2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1699–1702. doi: 10.3201/eid2310.171017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikolay Birgit. A review of West Nile and Usutu virus co-circulation in Europe: how much do transmission cycles overlap? Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2015;109(10):609–618. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.OIE. OIE-West Nile Fever. Available at: http://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Reviewreport/Review?page_refer=MapFullEventReport&reportid=27744. (Accessed: 13th November 2018) (2018).

- 44.Nikolay B, et al. Development of a Usutu virus specific real-time reverse transcription PCR assay based on sequenced strains from Africa and Europe. J. Virol. Methods. 2014;197:51–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jöst H, et al. Isolation of usutu virus in Germany. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:551–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson SJ, et al. Viral population analysis and minority-variant detection using short read next-generation sequencing. Philos Trans. R. Soc L. B. Biol. Sci. 2013;368:20120205. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D46–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gill MS, et al. Improving Bayesian population dynamics inference: a coalescent-based model for multiple loci. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:713–24. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rambaut, A. FigTree. Available at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Movie: Geographic distribution of USUV strains detected in dead blackbirds in the Netherlands.

Data Availability Statement

The genomic sequences of the Usutu viruses sequenced in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MN122145 – M122256.