Abstract

Cysteinyl cathepsins are lysosomal/endosomal proteases that mediate bulk protein degradation in these intracellular acidic compartments. Yet, studies indicate that these proteases also appear in the nucleus, nuclear membrane, cytosol, plasma membrane, and extracellular space. Patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) show increased levels of cathepsins in the heart, aorta, and plasma. Plasma cathepsins often serve as biomarkers or risk factors of CVD. In aortic diseases, such as atherosclerosis and abdominal aneurysms, cathepsins play pathogenic roles, but many of the same cathepsins are cardioprotective in hypertensive, hypertrophic, and infarcted hearts. During the development of CVD, cathepsins are regulated by inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, hypertensive stimuli, oxidative stress, and many others. Cathepsin activities in inflammatory molecule activation, immunity, cell migration, cholesterol metabolism, neovascularization, cell death, cell signaling, and tissue fibrosis all contribute to CVD and are reviewed in this article in memory of Dr. Nobuhiko Katunuma for his contribution to the field.

Keywords: cathepsin, atherosclerosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, hypertrophy, myocardial infarction, heart failure

1. Introduction

Cysteinyl cathepsins are primarily intracellular proteases for non-specific bulk proteolysis in the endosomes and lysosomes [1]. There are 11 members in this family in humans [2] named alphabetically as B, C (also called J or DPPI [dipeptidyl peptidase I]), F, H, K (initially called O), L, O, V (also named as L2), S, W, and Z (also named as X or P). These cathepsins are regulated by their endogenous inhibitor cystatins, including intracellular stefin A and B, extracellular cystatin C, E, M, F, D, S, SA, SN, and kininogens in the circulation [3, 4]. Likely because of their primary localization in the endosomes and lysosomes, all cathepsins show their optimum activity under an acidic pH. Yet, accumulating evidences indicate their activities in extracellular matrix protein (ECM) degradation, a best-studied mechanism of cathepsin participation in the development of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Among all cathepsins, only cathepsin S (CatS) remains partially active at a neutral pH [5]. Apparently, CatS is not the only enzyme for ECM degradation. Therefore, there must be mechanisms for these lysosomal proteases being active under unfavorable conditions.

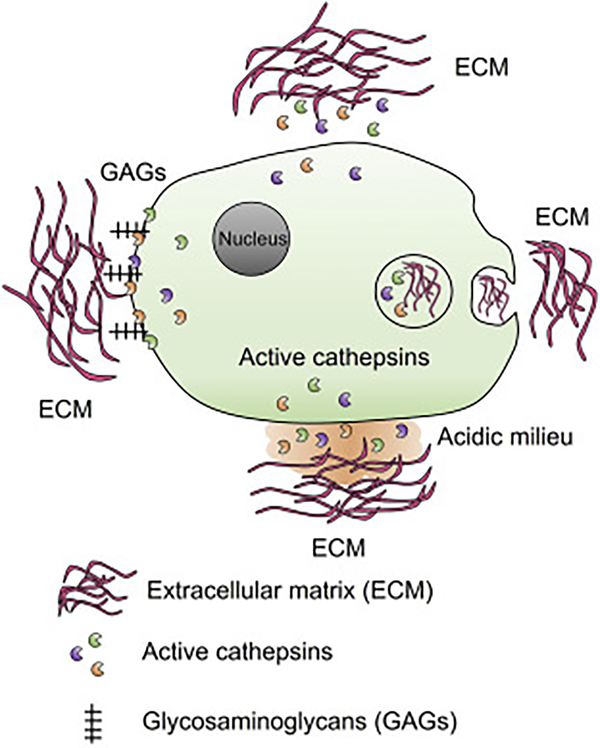

It is possible that at least for a short time at a neutral pH, cathepsins remain active (Figure 1, top side). Therefore, cells must constantly secrete active cathepsins for ECM degradation. This hypothesis may be possible, but cannot be the major mechanism and yet there is no evidence to support this possibility. Studies showed that ECM can be phagocytosed and degraded intracellularly (Figure 1, right side). This hypothesis has been proven using both cell permeable and non-permeable cathepsin inhibitors. About one third ECM degradation occurred intracellularly and two thirds extracellularly [6]. The best-studied mechanism is glycosaminoglycan (GAG)-mediated cathepsin stabilization under a neutral pH [7, 8] (Figure 1, left side). GAGs are heteropolysaccharides with repeating disaccharide units with a high negative charge because of multiple carboxyl groups and sulfate substitutions as most GAGs are sulfated, including chondroitin, keratin, dermatan, heparan, and heparin. GAG regulation of cathepsin activities was first reported for CatL. GAGs accelerate the activation of CatL zymogen to mature form, including at a neutral pH [9, 10]. GAGs show the same activity on CatB and CatS [11, 12]. GAGs control cathepsin activation by two possible mechanisms [12]: Upon binding, GAGs convert cathepsin zymogen into a better substrate; GAG binding favors the zymogen open conformation to promote activation in both acidic and neutral pH. Therefore, GAGs allosterically regulate cathepsin activity and stability [13, 14]. For example, all tested GAGs increased the stability of CatK over a broad range of pH. Chondroitin from the cartilage prominently increased the collagenase activity of CatK [15]. Heparin is a strong activator of CatK at a physiological plasma pH, and increases CatK elastase and collagenase activity and enzyme half-life [14]. We also favor the interface acidification mechanism (Figure 1, bottom side). Once cells attached to the ECM, cell membrane vacuole-type H+-ATPase [16] or other proton pumps such as Na+-H+ exchanger-1 [17, 18] may be activated to acidify the local environment. This hypothesis has been confirmed [19]. Bafilomycin is an inhibitor of intracellular and extracellular space acidification. It inhibits macrophage elastase activity by inhibiting the vacuole-type H+-ATPase [16]. During bone resorption, CatK and chondroitin co-localize at the ruffles border between osteoclast and bone interface [20].

Figure 1.

Cathepsin stability and activity against ECM. Active forms of cathepsins may be secreted constantly for ECM degradation (top side). ECM can also be internalized by phagocytosis and degraded intracellularly (right side). Plasma membrane GAGs play important role in cathepsin stabilization under neutral pH to maintain cathepsin activity in ECM degradation (left side). Cell-EMC interface may also form acidic milieu where allows cathepsin to degrade ECM (bottom side).

Cathepsin-mediated ECM degradation not only destabilize the arterial wall and cause ruptures to the macro- and micro-vasculatures, but also generate bioactive fragments that can be pathogenic or beneficial to the vasculatures. CatL generates angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin by degrading human and mouse collagen-XVIII [21, 22]. In contrast, CatS cleaves the anti-angiogenic collagen-IV peptides canstatin and arresten [23], thereby promoting angiogenesis. We also showed that CatS processes laminin-5 and generates the pro-angiogenic γ2’, γ2χ, and γ2” fragments [23]. In the myocardium, CatS cleaves fibronectin and generates the ED-A fragment that promotes cardiac fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts [24].

In addition to ECM degradation, cathepsin activities in CVD also include activation of zymogens, pro-hormones, chemokines, and nuclear membrane Toll-like receptors (TLR). CatK involves in pro-MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinase-9) conversion into active MMP-9 [25]. CatC activates grazymes A and B, mast cell chymase and tryptase, CatG, proteinase-3, and neutrophil elastase [26–30]. CatB, CatL and CatK from thyroid epithelial cells release thyroid hormones from the extracellular thyroglobulin [31–33]. As we will discuss further, CatS, CatK, and CatL activate endosomal TLR-7 and TLR-9 [34, 35]. In smooth muscle cells (SMC), CatS cleaves the pro-inflammatory chemokine CX3CL1, also known as fractalkine, and regulates cell adhesion and monocyte capture [36]. CatC regulates neutrophil recruitment by producing chemokine CXCL12, also known as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1), during elastase-induced mouse abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) [37].

In this review, we will summarize what we have leaned from current knowledge regarding cathepsin function in CVD, from biomarkers to experimental models, and from expression regulation to pharmacological inhibition as a drug target.

2. Cathepsin cellular localizations

Although cathepsins primarily reside in the endosomes and lysosomes, accumulating evidence suggest additional localizations in the nuclei, nuclear membrane, cytosol, plasma membrane, and extracellular space under certain conditions. After cells are exposed to apoptotic stimuli, cathepsins go to the cytosol to process Bcl-2 and trigger apoptosis [38–40]. Under inflammatory stimulation, cathepsins may be released to the extracellular space to target ECM. Yet, extracellular cathepsins can also bind to the plasma membrane and exert their activity on plasma membrane. In ovarian carcinoma cells, membrane-bound CatB activates urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) [41]. In colorectal carcinoma cells, CatB binds to annexin-II tetramer and locates in the caveolae membrane microdomain [42]. On melanoma cell membrane, CatL mediates tumor cell metastasis [43]. CatX binds to CHO cell surface GAGs to promote CatX activity and stability [44]. On macrophage, monocytes, and dendritic cells, pre-CatX binds to the β2 integrin receptors Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) and LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18), where CatX gets activated. Mature CatX then activates β2 integrin receptors, promotes monocyte/macrophage adhesion to ECM, and regulates monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis, DC maturation, and T-cell proliferation and migration [45, 46]. On SMC plasma membrane, active CatS colocalizes with integrin ανβ3 on vascular SMC and plays a role in SMC-mediated ECM degradation and invasion [47]. All these activities from plasma membrane-bound cathepsins, although some are from tumor cell studies, may occur in cardiac and vascular cells and contribute to the development of CVD.

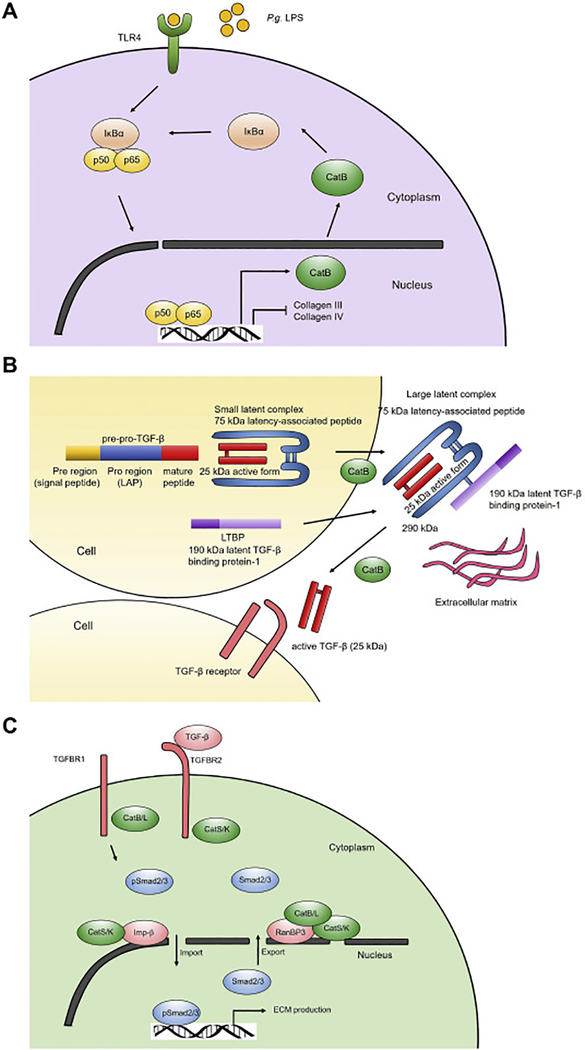

We recently revealed a proteolysis-independent mechanism of cathepsins in TGF-β signaling in a mouse unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced kidney fibrosis model [48]. TGF-β signaling is mediated by its two plasma membrane receptors TGF-β receptor-1 (TGFBR1) and TGF-β receptor-2 (TGFBR2). TGF-β binds to TGFBR2, followed by activation of TGFBR1. This activity of TGFBR2 is suppressed by TCPTP (T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase). TGFBR1 activation leads to phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3. Phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 (p-Smad2/3) form a Smad complex that is translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus. This step is mediated by nuclear membrane importing proteins, including importin-β. Within the nucleus, p-Smad2/3 complex gets dephosphorylated and then exported to the cytosol, a process that is mediated by nuclear membrane exporting protein complex, including RanBP3 as outlined in Figure 2A. Using mouse kidney tubular epithelial cells, we found that CatB and CatL bind to TGFBR1 that may block its activation by TGFBR2, thereby reducing the TGF-β signaling and p-Smad2/3 production. In contrast, CatS and CatK bind to TGFBR2 to interfere the action of the negative regulatory molecule TCPTP, leading to enhanced TGFBR1 activity, TGF-β signaling, and p-Smad2/3 production (Figure 2A). At the nuclear membrane, CatS and CatK increases the expression of importin-β, whereas CatB and CatL decreases importin-β expression, but increases the expression of nuclear exporter protein RanBP3. CatS and CatK preferentially bind to the nuclear importin-β and RanBP3, which may increase the shuttling of p-Smad2/3 complexes between the cytosol and nucleus, whereas CatB and CatL only bind to RanBP3 and reduce the p-Smad2/3 complex nuclear translocation (Figure 2A). In the absence of CatS or CatK, TCPTP blocks the TGFBR2 activity. Therefore, CatB and CatL remain active to bind and reduce the TGFBR1 activity on the plasma membrane. On the nuclear membrane, absence of CatS or CatK affects the nuclear translocation of the p-Smad2/3 complexes, thereby reducing TGF-β signaling (Figure 2B). In the absence of CatB and CatL, CatS and CatK remain active and bind to TGFBR2, thereby activating TGFBR1 and p-Smad2/3 signaling. CatS and CatK binding on nuclear membrane importin-β and RanBP3 enhances p-Smad2/3 complex shuttling between cytosol and nucleus, thereby increasing TGF-β signaling and fibrotic protein expression (Figure 2C). Our study reveals a novel mechanism of cathepsins in TGF-β signaling by binding to both plasma membrane TGF-β receptors and nuclear membrane p-Smad2/3 complex transporters [48]. As we will discuss further, cathepsin activities in skin and lung fibroblast TGF-β signaling may differ from kidney epithelial cells. A same cathepsin can have different activities, depending on the cell types.

Figure 2.

Different roles of cathepsins in TGF-β signaling. TGF-β-induced p-Smad2/3 complex nucleus translocation and fibrotic protein expression in kidney epithelial cells from WT mice (A), CatB- and CatL-deficient mice (B), and CatS- and CatK-deficient mice (C).

3. Cathepsin expression regulation

While most tested tissue and cell types express CatB, other cathepsins are inducible. We reported induced expression of CatS, CatK, CatL, and CatB in human atherosclerotic and AAA lesions [49, 50] and in infarcted mouse hearts [24, 51]. In diet-induced mouse atherosclerotic lesions, increased expression of cathepsins [52] was found at the sites prone to rupture, including macrophages boarding the lipid core and adjacent to the fibrous cap, or macrophages and SMC in the shoulders [53, 54]. From human and rat left ventricle (LV) hypertrophy heart or heart failure (HF), real time (RT)-PCR and immunostaining revealed expression of CatS together with IL1β in human and rat HF LV tissues. In these tissues, CatS was located to cardiomyocytes and coronary SMC and macrophages. CatS activity in LV intramyocardial coronary artery elastin fragmentation was increased. In cultured mouse neonatal cardiomyocyte, IL1β increased CatS expression and activity [55]. In stenotic human valves, RT-PCR and immunostaining revealed increased expression of CatS, CatK, CatV, and cystatin C and total cathepsin activity in infiltrated inflammatory cells, bony area, and ECs in neovascularization [56]. Therefore, any stimulus to harm the aorta or myocardium may induce cathepsin expression that can play either pathogenic or beneficial roles to the initiation and progression of CVD. These stimuli can be diseases, diet, inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, or mechanical injuries and can involve inflammatory, vascular, and cardiac cells (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cathepsin expression regulation.

| Stimuli | Cathepsin expression and activity |

|---|---|

| Cytokines (positive regulators) | |

| IL1β, IFN-γ, THF-α, IL6, IL13 | Increase |

| Growth factors | |

| VEGF, bFGF | Increase |

| Cytokines (negative regulators) | |

| TGF-β, IL10 | Decrease |

| Other molecules | |

| Ang-II, Aβ40/42, oxLDL | Increase |

| Other mechanisms | |

| Shear stress | Increase |

| Paracrine mechanism from other cells, RNA editing | In(de)crease |

| Indirect mechanisms | |

| IFN-γ, IL6, LPS, CpG ODN to reduce cystatin C | Increase |

In human or mouse SMCs and ECs, IL1β, IFN-γ, TGF-α, VEGF, bFGF increase the expression of CatL [50], CatS [57], and CatK [58–60]. Oscillatory shear stress induces the expression of CatS, CatL, and CatK in human and mouse aortic ECs. Inhibition of CatL and CatK with siRNA reduces sheer stress-induced gelatinase and elastase activity [61–63]. Cathepsin expression can also be indirectly regulated. To human aortic ECs, TGF-α-induced expression and activity of CatK and CatV can be increased by co-culturing ECs with THP-1 monocytes in a JNK-dependent manner [59] (Table 1).

Inflammatory cells are major sources of cathepsins in atherosclerotic and AAA lesions, and in infarct or hypertrophic hearts. Macrophages are among the most-studied inflammatory cells in cathepsin expression and function. Inflammatory cytokines IL1β, IFN-γ, TGF-α, IL6, and IL13 induce macrophage expression of CatK, CatS, and CatL, and their elastinolytic and collagenolytic activities [47, 50], whereas TGF-β and IL10 inhibit CatK expression in vascular cells and macrophages [49][64–68]. As an indirect mechanism to increase cathepsin activity, IFN-γ, IL6, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), CpG ODN, and other inflammatory signals may reduce cystatin C secretion and indirectly increase cathepsin activity [69–71]. In addition to these common inflammatory molecules, many other mechanisms also induce cathepsin expression in macrophages. Angiotensin-II (Ang-II) [72], pathogenic β-amyloid peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42 [73], and oxLDL [74] induce the expression of CatF and CatS from human monocyte-derived macrophages (Table 1). IL3-induced differentiation of human monocytes into macrophages also increases the expression of CatK and CatV [6].

Cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts are major cardiac cells involving in MI and cardiac hypertrophy in addition to ECs and inflammatory cells. While normal hearts express negligible or no cathepsins, cytokine, Ang-II, and superoxide enhance heart cathepsin expression [75]. CatS, CatK, CatB, and CatL are expressed in cardiomyocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts in hearts with infarction, hypertrophy, HF, or valvular disease [24, 51, 55, 76, 77]. IL1β induces CatS expression in neonatal cardiomyocytes [55]. In high-salt diet-induced hypertensive HF, superoxide anions activate cathepsins and trigger myocardial remodeling [78].

Cathepsin expression can also be regulated at the RNA levels via RNA editing. A single nucleotide change by the adenosine deaminase unwinds stable double strand RNA into RNase targetable single strand RNA [79, 80] (Table 1). We discussed this mechanism in details in our recent review [81].

4. Cathepsins as biomarker and risk factor of human CVD

Since we first reported cathepsin expression in human atherosclerotic and AAA lesions [49, 82], plasma cathepsin levels have been associated with the development of human CVD. We first reported elevated serum CatS levels in patients with atherosclerotic stenosis [83]. From two community-based cohorts from Sweden: the ULSAM (Uppsala Longitudinal Study of Adult Men) and PIVUS (Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors), serum CatS levels are associated with increased risk of mortality in a multivariate COX regression test after adjusting for age, blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, cholesterol, anti-hypertension treatment, lipid-lowing treatment, and history of CVD. Higher serum CatL and CatS are associated with cardiovascular mortality [84, 85]. Patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have higher plasma CatL and CatK than those with stable angina [86–88]. Plasma CatL levels increase by >10% in patients with coronary artery stenosis, and persist after adjusting for sex, smoking, age, and glucose levels [50]. Plasma CatK levels exert negative association with high-density lipoprotein (HDL) but positive association with high sensitivity-C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that CatK was an independent predictor of human coronary artery diseases (CAD) [86, 88]. From patients with HF, those with low left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) had higher plasma CatK than those with high LVEF. Linear regression showed that CatS correlated negatively with LVEF and positively with LV end-diastolic and systolic dimensions, and left atrial diameters. Multivariate logistic regression test showed CatK as an independent predictor of congestive heart failure (CHF) [89]. Studies also showed that plasma CatK levels were higher in patients with major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and CatK was an independent predictor of MACCE [90]. Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) also had high plasma CatK, along with high N-terminal propeptide of collagen-I and C-terminal telopeptide of collagen-I (ICTP). Patients with persistent AF had higher CatK and ICTP than those with paroxysmal AF [91].

We originally reported cystatin C-deficiency from 8 patients with dilated abdominal aorta [82]. From a cohort of 476 male AAA patients and 200 age-matched male controls that we had from Denmark, we demonstrated that the plasma total CatS, pro-CatS, and mature CatS levels were all significantly higher in AAA patients than in non-AAA controls. Logistic regression showed that plasma total and pro-CatS were independent risk factors of AAA. Total, pro-CatS, and active CatS correlated positively with maximal aortic diameter, whereas plasma cystatin C associated negatively with AAA. Univariate and multivariate correlation tests showed that total and active CatS correlated positively with aortic diameter [92]. This study was subsequently confirmed in a smaller cohort of 31 AAA patients and 32 controls. Serum CatS and CRP levels were increased in AAA patients and correlated each other. Both CatS and CRP were associated with AAA diameters [93]. From the same Danish cohort that we have, plasma CatL levels were also higher in AAA patients than in controls and positively associated with plasma CatS and maximal aortic diameter. Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that plasma CatL was a risk factor of human AAA [94]. Plasma cystatin B levels were also significantly higher from these Danish AAA patients than in age-matched controls (251.6±90.2 ng/mL vs. 220.3±64.7 ng/mL, P=2.40e-8) and positively correlated with AAA size r=0.150, P<0.0001. Logistic regression analysis showed association between cystatin B and presence of AAA before (odds ratio [OR]=1.65, P<0.0001) and after adjustment for AAA confounding factors (OR=1.526, P<0.0001) [95].

5. Cathepsin expression in human atherosclerotic and AAA lesions

CatS and CatK are the first cathepsins found in human atherosclerotic lesions [49]. These cathepsins present in SMCs from early human atherosclerotic lesion media and intima. In advanced lesions, CatS and CatK present in macrophages and SMC from the fibrous caps [49] and in ECs in the lumen and in microvessels [16]. Cathepsin active site labeling found that CatS and CatB activities were increased in unstable plaques. M2 macrophages from unstable plaques contained 5-fold higher cathepsin activity than M2 cells from stable plaques [96]. As a potent elastase and collagenase, CatK was found colocalized with the C-terminal fragments of type I collagen (CTX-I) in areas with intimal hyperplasia and in shoulder of advanced plaques from patients with early or advanced atherosclerosis. Human monocyte-derived macrophages and foam cells produced CTX-1 when cultured on type I collagen rich matrix [97]. CatL expression in human atherosclerotic lesions was localized to CD68+ macrophages and at a lower level to SMCs, and correlated with apoptosis and stress protein ferritin. Plaques from symptomatic patients contained much higher CatL expression than those from asymptomatic patients [50, 98]. CatF and CatV in atherosclerotic lesions showed similar expression pattern to CatS, mainly in macrophages, ECs, and SMCs [6, 99].

Human AAA lesions contain elevated levels of protein, mRNA, and activity for most tested cathepsins, including CatH, CatB, CatL, CatK, and CatS in microvessel ECs, media SMCs, and macrophages [100–104]. We previously reported cystatin C-deficiency in AAA lesions [82]. This observation was later confirmed with much larger sample sizes [100, 103]. In human AAA lesions, CatS negatively associated with the full-length collagen-I, but positively associated with the type 1 collagen-derived CTX-1 fragments [104], although CatS is a much weaker collagenase than CatK [105].

6. Cathepsin functions from experimental CVD

6.1. Atherosclerosis and neointima formation

Neointima hyperplasia leads to atherosclerotic lesion growth. Several mouse carotid artery neointima formation models, including wire injury, carotid ligation injury, and vein graft consistently showed the increased expression of CatL and CatS. Deficiency of CatL or CatS reduced intima hyperplasia, plaque elastin disruption, and reduced lesion monocyte/macrophage accumulation, cultured macrophage migration, lesion SMC proliferation, and cultured SMC p38 MAPK, Akt, and HDAC6 activation, and TLR-2 expression [106–108]. From 5/6 nephrectomy-induced chronic renal disease, CatS inhibition (with the Roche inhibitor RO5444101) or genetic deficiency reduced atherosclerotic lesion elastin fragmentation, plaque size, macrophage contents, and aortic and valvular calcification [109, 110].

From diet-induced atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice, transfer of bone-marrow from cystatin C-deficient mice increased atherosclerotic lesion sizes in the aortic root by 30% compared with those received bone-marrow from wild-type (WT) control mice [111]. Deficiency of CatK reduced the brachiocephalic artery atherosclerotic lesion size, lesion macrophage contents and apoptosis, and increased lesion elastin and collagen contents and fibrous cap thickness [112]. Similarly, aged CatK-deficient Apoe−/−Ctsk−/− mice (26 weeks) on a chow diet also showed smaller atherosclerotic size and fewer lesions in the aortic arch than those from the WT control mice. Lesions from Apoe−/−Ctsk−/− mice displayed increased lesion collagen content and elastica integrity [113]. Macrophages from Apoe−/−Ctsk−/− mice demonstrated increased CD36-dependent oxLDL uptake [113]. CatS activity in atherosclerosis has also been tested in Apoe−/− mice. After consuming a high fat diet (HFD) for 12 weeks, Apoe−/−Ctss−/− mice had 73% fewer acute plaque rupture events and 46% smaller plaque size in the brachiocephalic artery than the WT control mice. Plaque stability as determined by lesion elastin, collagen, lipid, and macrophage contents increased by 67% [114]. From Apoe−/− mice on a western diet for 8 weeks, CatS inhibition with a selective inhibitor showed similar phenotypes to the Apoe−/−Ctss−/− mice with reduced brachiocephalic artery lesion size, macrophage accumulation, media elastin breaks, and buried fibrous caps [115].

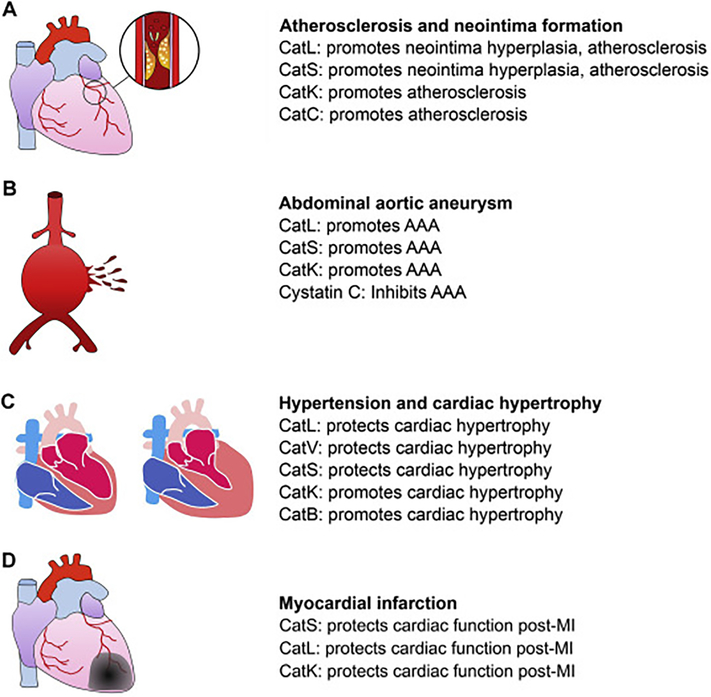

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice (Ldlr−/−) fed an atherogenic diet also develop atherosclerosis. By introducing the CatS-deficient Ctss−/− mice and CatL-deficient Ctsl−/− mice to this model, we demonstrated a role of CatS and CatL in atherogenesis. Deficiency of these cathepsins reduced atherosclerosis in the aortic arch and thoracic to abdominal aortas, although we did not examine the aortic roots [116, 117]. Deficiency of these cathepsins reduced lesion macrophage content, lipid cores area, T-cell content, SMC content, elastin fragmentation, collagen content. To Ldlr−/− mice, transplantation of bone-marrow from CatC-deficient Ctsc−/− mice reduced atherosclerotic burden in the carotid artery, arch, and root. Mechanistic study showed that CatC blocked M2 macrophage and Th2 lymphocyte polarization [118], CatS promoted SMC apoptosis, reduced macrophage cholesterol uptake [119], and increased monocyte and T-cell trans-endothelium migration [120]. Therefore, all tested cathepsins (CatL, CatS, CatK, and CatC) play pathogenic roles in neointima hyperplasia and atherosclerosis (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Cathepsin function in aortic and cardiac diseases. Different cathepsins may play detrimental or beneficial roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and neointima formation (A), AAA (B), hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy (C), and myocardial infarction (D).

6.2. Abdominal aortic aneurysm

We reported cystatin C-deficiency in human AAA lesions with increased CatS, CatL, and CatK expression [82]. From aortic elastase perfusion-induced AAA in mice, cystatin C-deficiency enhanced AAA development and lesion cathepsin activity with increased lesion macrophage and T-cell contents, elastin fragmentation, SMC apoptosis and loss, and microvessel contents [121]. From the same model or in peri-aortic CaCl2 injury-induced AAA, we also demonstrated that deficiency of CatL and CatK reduced AAA development with reduced lesion macrophages, CD4+ T cells, chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels, angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and elastin fragmentation [122, 123]. From Ang-II subcutaneous perfusion-induced AAA, CatS-deficiency in Apoe−/−Ctss−/− mice reduced AAA incidence and size, media elastin fragmentation, SMC apoptosis and loss, lesion chemokine expression and inflammatory cell accumulation (MCP1 expression, macrophage and CD4+ T-cell contents, and lesion T-cell proliferation) [120]. In this aortic disease, all tested cathepsins (CatL, CatS, and CatK) also play detrimental roles (Figure 3B). With unknown mechanisms, CatL-deficiency reduced the expression and activity of other cathepsins (CatB, CatS, CatK) and MMPs (MMP-2, MMP-9) in ECs [122]. In SMCs, CatL-deficiency reduced CatK, MMP-2, and MMP-9 expression and CatK-deficiency reduced CatL, MMP-2, and MMP-9 activities [123]. Therefore, deficiency of one cathepsin affects the expression and activity of other proteases, a historic puzzle that has never been fully understood.

6.3. Hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy

While most studies proved pathogenic roles of cathepsins in aortic diseases, cathepsin functions in the myocardium can be different. One year old Ctsl−/− mice developed ventricular and atrial enlargement as dilative cardiomyopathy with modestly increased heart weight and increased interstitial fibrosis, likely because of reduced collagenolytic activity due to CatL-deficiency. These mice showed impaired myocardial contraction and develop supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular extrasystoles, and first-degree atrioventricular block [124]. Cardiomyocyte-specific CatL transgene expression (α-myosin heavy chain promoter) in Ctsl−/− mice improved cardiac contraction with normal atrionatriuretic peptide expression, heart weight, and cardiomyocyte ultrastructure [125]. From aortic banding-induced cardiac hypertrophy, Ctsl−/− mice displayed exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy, worsened cardiac function, and increased mortality. Cardiac cells from hypertensive Ctsl−/− mice showed impaired lysosomal protein degradation, increased sarcomere-associated protein aggregation, increased ubiquitin-proteasome system and altered endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis [126]. Phenylephrine-induced hypertrophy in neonatal cardiomyocytes from Ctsl−/− mice was more pronounced than control cells [126]. Studies showed that CatL protected against hypertension-induced cardiac hypertrophy via the inactivation of the Akt/GSK3b signaling pathway. CatL expression blunted cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by blocking the AKT/GSK3b signaling [127]. In the same model of aortic banding-induced cardiac hypertrophy, transgenic expression of CatL attenuated hypertrophic responses, reduced myocardium cell apoptosis and fibrosis, and preserved cardiac function, along with attenuated AKT/GSK3b signaling. CatV acted the same as CatL. In human cardiomyocytes, recombinant CatV blocked Ang-II-induced expression of hypertrophic molecules atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), B-type natriuretic peptides (BNP), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) expression, by repressing the phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK [128].

CatS acts similarly to CatL or CatV. Ctss−/− mice developed severe cardiac fibrosis (expression of collagen-I and α-SMA) with increased myocardium macrophage infiltration and cytokine expression after 7 days of Ang-II infusion. Hearts in these mice contained abnormal autophagosomes and appeared defect in damaged mitochondria clearance, leading to increased reactive oxygen species and NF-κB activation [129].

In contrast to our expectation, several studies unequivocally suggest an opposite role of CatK from CatL or CatS in mouse cardiac hypertrophy. Aged mice (24 mon old) developed significantly enlarged cardiac chamber size, wall thickness, cardiomyocyte cross-sectional area, and fibrosis, decreased cardiac contractility, prolonged relengthening along with compromised cardiomyocyte intracellular Ca2+ release compared with young mice (6 mon old). These symptoms were diminished in CatK-deficient Ctsk−/− mice. CatK-deficiency reduced the expression of cardiomyocyte senescence markers cardiac lipofuscin, p21 and p16, cardiomyocyte apoptosis and nuclear translocation of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor [130]. WT mice fed a HFD showed increased heart weight and LV thickness, reduced fractional shortening (FS), and increased cardiomyocyte size and hypertrophic protein expression and apoptosis. CatK-deficiency reversed impaired cardiomyocyte contractility and dysregulated calcium handling, and improved glucose intolerance and insulin-stimulated Akt activation [77]. In pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, CatK-deficiency also protected mice from cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction with blunted mTOR and Erk signaling in heart and cultured cardiomyocytes. CatK overexpression in cultured cardiomyocytes trigged cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, which was blocked by mTOR and Erk inhibitors [131].

CatB acts similarly to CatK. In pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, CatB-deficient Ctsb−/− mice demonstrated reduced heart and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, reduced interstitial and perivascular fibrosis, and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and reduced myocardium expression of TNF-α, p-ASP1, p-JNK, p-c-Jun [132]. In H9c2 cells, Ang-II induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [133] and CatB expression directly affected cell size and expression of hypertrophic markers ANP, BNP, and β-MHC [132]. Therefore, all five tested cathepsins acted differently in cardiac hypertrophy. While CatL, CatV, and CatS are beneficial, CatK and CatB are detrimental to cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 3C).

6.4. Myocardial infarction

Cathepsin functions in infarcted hearts also differ from those in the aorta. Using left coronary artery ligation-induced MI, we established a role of CatS in controlling myofibroblast differentiation and protecting cardiac functions. Pan inhibition of cathepsins with E64d exacerbated cardiac dysfunction, reduced myocardium CD4+ T-cell accumulation, p-Smad-2/3 expression and fibrosis (collagen, α-SMA, fibronectin expression), and fibronectin ED-A fragment accumulation essential for myofibroblast differentiation [24]. In cultured fibroblasts, TGF-β induced α-SMA and CatS expression. CatS-deficiency or inhibition blocked fibronectin and α-SMA expression [24]. MI also induces myocardium CatL activity. CatL-deficiency increased post-MI mortality, infract scar dilatation, infarct length, heart weight to body weight ratio, and reduced infarct segment thickness, myocardium MMP-9 activity, numbers of myocardium inflammatory cells (monocyte, macrophage, c-kit+ cell, NK1.1 cell), fibroblasts and fibrosis, and reduced myocardium VEGF expression and microvascularization [134]. We recently reported that patients with AMI contained significantly higher plasma CatK levels than normal controls and those with stable and unstable angina pectoris. In mice, heart CatK expression was increased at 7 days and then declined at 28 days post-MI. CatK-deficiency further increased diastole and systole left ventricular internal diameter (LVID), decreased systole left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPW;s), and reduced FS and EF at both 7-day and 28-day post-MI, with increased myocardium fibrosis and cell death [51]. These studies from MI mice proved cardioprotective function of CatS, CatL, and CatK (Figure 3D).

7. Different cathepsin activities in CVD

7.1. Inflammation

Cathepsins control inflammation by proteolyticaly activating cytokines and chemokines (Table 2). In human fibroblasts, CatL enhances the activity of IL8 by limiting the N-terminal truncation and plays a role in IL8 proteolytic activation at the site of inflammation [135]. In mouse monocyte-derived macrophages, CatB activity involves in the posttranslational processing and production of LPS-induced TNF-α. In these cells, CatB-selective inhibition leads to cytosol accumulation of TNF-α precursor-containing vesicles [136].

Table 2.

Cathepsin activities in CVD.

| Cathepsin activity | Cathepsins | Functions relevant to CVD |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | CatB, CatL | Cytokine/chemokine proteolytic activation [135, 136] |

| CatB, CatL | NLRP3 inflammasome activation [137–139] | |

| Immunity | CatB, CatL, CatF | Antigen presentation, CD4+ T-cell activation, Th17 cell differentiation [140–145, 147–149] |

| CatS, CatK, CatL | TLR7 activation, Treg activity suppression [150] | |

| Cell migration | CatS | SMC CX3CR1 release and monocyte capture, monocyte/macrophage trans-endothelium migration [36, 47, 116] |

| CatC | Neutrophil serine protease activation and migration [37, 154] | |

| Cholesterol metabolism | CatH | LDL modification and foam cell formation [158] |

| CatF, CatB, CatK, CatS, CatL, CatV | apoB-100 cleavage, LDL aggregation [99, 159] | |

| CatS, CatF, CatK, CatB | apoA-1 degradation, cholesterol efflux inhibition [161–163] | |

| Angiogenesis | CatS | PAR-2 activation and endothelium damage, collagen-IV-derived canstatin and arresten degradation, laminin-5 γ2 fragment generation [23, 57, 163] |

| CatK | EC proliferation and invasion [60] | |

| CatL | EPC homing to injured vasculature [166] | |

| Cell death | CatB, CatL, CatS, CatK | Bid proteolysis into tBid and consequent cytochrome C release from the mitochondria [170, 171, 174–177] |

| Autophagy | CatL, CatS, CatB | Required for HUVEC, HAEC, and macrophage autophagy, but reduce cardiomyocyte autophagic degradation, required for HUVEC, cardiomyocyte, and macrophage survival, but increase HAEC death, required for M2 macrophage polarization [126, 183, 185, 188, 191] |

| Cell signaling and tissue fibrosis | CatB, CatL | EGF/EGF receptor complex intracellular degradation [192–195] |

| CatB, CatX | IGF-1 degradation [196, 197] | |

| CatS, CatK, CatB, CatL | TGF-β signaling and tissue fibrosis (Figures 2 and 4) [200, 205] |

Recent studies indicate a role of inflammasome in activating caspase-3 and −9 and in activating IL1β and IL18 [81]. Serum amyloid A (SAA) is an acute phase inflammatory protein. SAA activates inflammasome and induces IL1β expression [137]. Silencing the inflammasome component NACHT, LRR, and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) reduces IL1β secretion. Inflammasome activation involves CatB and CatL (Table 2). CatB-selective inhibition blocks SAA-induced IL1β secretion from the inflammasome [137]. Saturated free fatty acid palmitate induces endothelial dysfunction and vascular permeability by activating inflammasomes. Genetic deficiency of NLRP3 or inflammasome inhibition with YVAD (caspase-1 inhibitor) or high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) inhibitor glycyrrhizin reduced HFD-induced impairment of vascular integrity. CatB-selective inhibition also abolished palmitate-induced NLRP3 activation and EC permeability [138]. Pre-aggregated Aβ40 and Aβ42 mixture induced cytosol cathepsin activity, NLRP3 inflammasome formation, caspase activation, and IL1β secretion in rat glial cells. Aβ treatment reduced the production of NLRP3 inflammasome negative regulator NLRP10, which is also a target of CatB and CatL [139].

7.2. Immunity

CatS, CatL, and CatF are essential to antigen presentation in professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), thymic epithelial cells, and macrophages by processing the MHC class-II-associated invariant chain (Ii), respectively, for T-cell activation [140–142] (Table 2). Later studies showed that CatS, but not CatL also processed Ii in nonprofessional APCs such as intestinal epithelial cells [143, 144]. Therefore, Ctss−/− mice showed reduced antibody production, antibody isotype switching, and CD4+ T-cell activation [140]. Ctsl−/− mice developed impaired CD4+ T-cell positive selection due to the defect of thymic epithelial cell antigen presentation and Ii processing [141]. Proper Ii processing and CD4+ T-cell activation control atherogenesis. In Ctsl−/− mice, thymic epithelium transgenic expression of human CatL or CatV (also called CatL2) rescued partially (~50%) the frequency of CD4+ T cells [145]. We reported that Ii-deficiency reduced autoantigen IgG1, IgG2b, and IgG2c production, impaired autoantigen antibody isotype switch, and protected mice from atherosclerosis [146]. In addition to Ii processing, cathepsins also mediate antigenic peptide production. CatB and CatH produce antigenic peptides from collagen-II and influenza hemagglutinin H5N1-HA [147]. Ctsl−/− mice showed impaired generation of MHC-II-bound peptide on cortical thymic epithelial cells [148]. In addition to antigen presentation, CatL contributes to CD4+ T-cell differentiation into Th17 cells. Th17 differentiation was suppressed by pan cathepsin inhibitor and CatL-selective inhibitor [149]. As we will discuss further, cathepsin activity reduces the differentiation, lifespan, and immunosuppressive activity of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) by activating TLR-7 [150] (Table 2). All these cells, such as CD4+ T cells, Th17 cells, and Tregs contribute to CVD [151, 152].

7.3. Cell migration

SMC migration and proliferation promote neointima formation. This activity of SMC requires cathepsin activity in ECM degradation. On matrix protein gels containing collagen or elastin, cathepsin pan inhibitor E64 and CatS-selective inhibitor LHVS blunted SMC invasion [47]. CX3CL1 (fractalkine) is the CX3C chemokine that binds to the G-protein-coupled receptor CX3CR1 [153]. In atherosclerotic lesions, SMCs express CX3CL1. Its membrane-bound form mediates cell-cell interaction, while its soluble form induces CX3CR1-positive leukocyte chemotaxis. CatS cleaves the membrane-bound form and releases the 55-kDa form to the media to capture monocytes (Table 2). CatS, CX3CL1, and endosome marker Rab11a colocalize in vascular SMCs, suggesting that this process occurs during the endosome trafficking of CX3CL1 to the plasma membrane [36].

Inflammatory cell migration and accumulation to the site of injury in the aortas or heart are one of the major events in the development of aortic and cardiac diseases. We reported that monocyte and macrophage migration through the subendothelium basement membrane required CatS activity. Such migration of monocytes/macrophages from Ctss−/− mice was effectively blocked [116] (Table 2). Under a similar condition, macrophages from Ctsk−/− mice showed no difference from WT cells in migration through the matrigel matrix assay, a reconstituted basement membrane [113]. CatC mediates neutrophil migration. In Sendai virus infection-induced airway acute inflammation, CatC-deficiency reduced neutrophil accumulation and chemokine/cytokine (CXCL2, TNF-α, IL1β, and IL6) expression in the lung. Reconstitution of WT neutrophils reversed these phenotypes, suggesting a role of neutrophil CatC in neutrophil recruitment and cytokine expression [154]. Such activity of CatC affected neutrophil accumulation in mouse AAA lesions. CatC activates neutrophil serine proteases to enhance further neutrophil recruitment to AAA lesions (Table 2). CatC-deficiency blocked neutrophil migration and AAA formation [37].

7.4. Cholesterol metabolism

Cholesterol accumulation and macrophage foam cell formation stimulate cathepsin expression by activating TLRs and the p38 MAPK pathway [155]. For example, CatS expression was increased during foam cell formation in human macrophages in response to oxLDL [74]. In turn, uptake of oxLDL also damages the lysosomal membrane [156], leading to lysosomal cathepsin translocation to the cytoplasm, where cathepsins act as cleavage enzymes during apoptosis [157]. Cathepsins also modify cholesterols to promote foam cell formation. For example, CatH and cholesterylesterase modify LDL and confer LDL the capacity in inducing macrophage foam cell formation [158]. ApoB is the primary apolipoprotein of LDL. CatF cleaves apoB-100, triggers LDL particle aggregation and fusion, and enhances LDL binding to human arterial proteoglycans in vitro [99]. CatB, CatK, CatS, CatL, and CatV also cleave apoB-100 and enlarge LDL particles [159] (Table 2).

Cathepsins degrade HDL and reduce macrophage foam cell cholesterol efflux [160] (Table 2). ApoA-1 is the major component of HDL that mediates HDL activity to stimulate ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1)-dependent macrophage foam cell cholesterol export. CatS degrades lipid-free apoA-1, leading to complete loss of apoA-1 cholesterol receptor function, and blocks cholesterol efflux from macrophage foam cells [161]. CatF and CatK also have this activity, leading to 30% and 15% reductions in cholesterol efflux [161]. CatB cleaves the C-terminal of apoA-1. Human monocyte-derived macrophage co-culture with human apoA-1 cleaved apoA-1 at Ser228-Phe229. This cleavage was also found in human carotid plaques [162]. Studies from patients with aortic valve stenosis (AVS) showed that CatS activity accounted for 54.2% of apoA-1 degradation in AVS and correlated with the mean transaortic pressure gradient in women (r=0.5, P=0.04) and was a significant predictor of disease severity in women (Stepwise linear regression, Standardized B coefficient=0.832, P<0.0001) [163]. Therefore, cathepsin activities in cleaving apoB-100 and apoA-1 both promote foam cell formation, important pathogenic component of human CVD.

7.5. Angiogenesis

EC damage and growth control the pathogenesis of CVD and associated mortality. Macrophage infiltration following aortic injury releases CatS to activate protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) on ECs and causes endothelium damage. Injection of recombinant CatS into normal mice caused marked endothelium damage, resulting vascular leakage and albuminuria. Endothelium was protected in PAR2-deficeint Par2−/− mice [164]. Cathepsin activity in angiogenesis is probably the best-studied in cancers [165]. We reported that inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic growth factors VEGF and bFGF promoted aortic EC CatS expression, but down-regulated cystatin C expression. Cytokines and growth factors also increased EC activity in ECM (elastin and collagen) degradation. Aortic ECs from Ctss−/− mice showed reduced activity in degrading ECM and in microvessel formation in a mouse skin wound-healing model [57]. We further demonstrated a role of CatS in RIP1-Tag2 transgenic model of mouse islet cell carcinogenesis. CatS-deficiency reduced tumor burden and angiogenesis, whereas cystatin C-deficiency yielded opposite results. Mechanistic studies showed that CatS degraded collagen-IV-derived anti-angiogenic peptides arresten and canstatin, and generated laminin-5-derived pro-angiogenic γ2, γ2’, and γ2χ bioactive fragments [23]. CatL is highly expressed in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and plays an essential role in EPC homing to the ischemia vasculature [166]. In ECs, CatK silencing or overexpression correlated with c-Notch-1 expression and its downstream signaling. CatK-deficient mice displayed impaired EC activities in invasion, proliferation, and tube formation, along with decreased circulating CD31+/c-Kit+ EPCs following femoral artery ligation-induced hind limb ischemia, which can be restored by bone-marrow transplant from WT mice [60]. From mouse experimental CVD models, cathepsin-deficiency directly affects angiogenesis that involves cathepsin activities in PAR2 signaling, ECM degradation, and bioactive molecule generation (Table 2).

7.6. Cell death

Lysosomes release cathepsins to the cytosol after destabilization or membrane permeabilization [167–169]. Lysosomal permeabilization also releases apoptogenic factors, among which Bid is the best-studied cathepsin substrate [170]. CatB, CatL, CatS, and CatK cleave Bid into 15-kDa pro-apoptotic tBid [170, 171] that activates Bax and promotes mitochondria release of cytochrome c and activates caspase-3 and −9 [172] (Table 2). Cathepsin activity in cell death has been tested in many cell types, including neurons [173], hepatocytes [174], myeloma cells [175], T cells [176], and cardiomyocytes [77].

Serine protease inhibitor 2A (Spi2A) is an anti-apoptotic cytosolic cathepsin inhibitor. Spi2A-deficiency led to the loss of memory phenotype CD44+CD8+ T cells with age or after lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Concomitant CatB-deficiency, however, rescued the survival of these CD8+ T cells [176]. We showed that HFD feeding enlarged cardiomyocytes in the heart and promoted cardiac hypertrophy and associated cardiac dysfunction in mice. CatK-deficiency blunted HFD-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and death [77]. In cultured human H9c2 cardiomyocytes, CatK silencing with siRNA also inhibited palmitic acid-induced release of cytochrome c and cleaved nuclear enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) from mitochondria [77]. Hyperthermic injury (HI) induced cardiomyocyte (H9c2 cell) apoptosis and increased CatB expression. Either the pan cathepsin inhibitor E64-c or heat shock protein HSP-70 blocked HI-induced H9c2 cell apoptosis and reduced cytosol cytochrome C and tBid, although this study did not test a specific role of CatB in HI-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte death [177].

7.7. Autophagy

Autophagy mediates cytosolic and organelle protein degradation. The initial step of this highly conserved process is to form the autophagosomes that engulf cytoplasmic components in the cytosol and organelles. During autophagy, a cytosolic form of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 LC3-I becomes phosphatidylethanolamine conjugated to form LC3-II that presents on the autophagosomal membrane [178]. Therefore, the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio is considered as a marker of autophagy that has normally considered as a preventive mechanism to reduce cellular damage and vascular inflammation [179].

Although detailed mechanisms are still not fully understood, the role of cysteinyl cathepsins in autophagy and associated cell survival has been tested in ECs, cardiomyocytes, and macrophages from cathepsin-deficient mice or treated with cathepsin inhibitors. Oxidized LDL (ox-LDL) is a biomarker and predictor of human CVD [180]. It induces inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and foam cell formation [181, 182]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), ox-LDL induces CatL expression, and promotes autophagy with increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. Ox-LDL also induces HUVEC expression of caspase substrate beclin 1 [183]. Caspase-mediated beclin 1 cleavage produces its C-terminal fragment that translocates to the mitochondria to sensitize cells to apoptosis signals. Therefore, beclin 1 cleavage products block autophagy function [184]. CatL inhibition blocked the increase of LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and expression of beclin-1, suggesting a role of CatL in promoting autophagy in HUVECs. Consistently, CatL inhibition enhanced ox-LDL-induced HUVEC apoptosis [183]. Therefore, CatL activities in assisting HUVEC autophagy and reducing HUVEC apoptosis may protect vascular endothelium from CVD-associated damage. However, studies from human aortic ECs (HAECs) yielded somewhat different conclusions. Ox-LDL also induced HAEC autophagy with increased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and expression of p62 [185], an autophagy receptor that recognizes cellular waste for clearance by autophagy [186]. Ox-LDL also reduced HAEC survival with increased oxidative stress (induced malondialdehyde and reduced superoxide dismutase expression) and endothelial dysfunction (increased soluble ICAM-1 expression and reduced eNOS expression). Cathepsin inhibition with E64d reversed all these phenotypes, supporting a role of cathepsins in promoting HAEC autophagy, but reducing HAEC survival that differs from the role of CatL in reducing HUVEC apoptosis [183].

Studies from cardiomyocytes also showed different results. Hypertrophic stimulation of mouse neonatal cardiomyocytes with phenylephrine induced CatL expression as well as LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and p62 expression. Different from HUVECs or HAECs, CatL-deficiency further increased the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and p62 expression, decreased cardiomyocyte viability, and increased phenylephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and proteasome activity [126]. Therefore, in cardiomyocytes, CatL plays a suppressive role in autophagy but is required for cardiomyocyte survival.

In mouse bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM), the activities of cathepsins, including CatB, CatS, and CatL were reduced when cells were treated with 7-Keto, the most abundant lipid metabolite in the oxLDL particle [187], with increased lysosomal expansion [188]. This activity of 7-Keto differed from that of ox-LDL in inducing CatL expression in HUVEC [183]. Ox-LDL and 7-Keto increase mitochondrial oxidative stress and cause mitochondrial damage [189] that is cleared by autophagy to prevent inflammatory events and cell apoptosis [190]. In BMDM, 7-Keto treatment increased mitochondrial fragmentation. Inhibition of CatB, CatS, and CatL intensified this 7-Keto activity and increased the expression of LC3 splicing variants LC3A and LC3B and p62 with dense clusters of p62 in the mitochondria, suggesting decreased autophagic degradation with increased intracellular mitochondrial content. Therefore, cathepsins in BMDM determine mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and maintain an anti-inflammatory environment [191]. Cathepsin inhibition promotes BMDM polarization to M1 phenotypes with increased expression of IL-1α, TNF-α and MCP-1 with reduced expression of M2 markers resistin-like molecule alpha (Retnla), arginase-1, CD206, IL10, and mannose receptor C-1 (Mrc-1) [188]. Together, the role of cathepsins in autophagy and cell survival can differ among different cell types. At present, cathepsin activities in autophagy in CVD still remain inconclusive.

7.8. Cell signaling and tissue fibrosis

Cathepsins as endosomal and lysosomal proteases have been implicated in cell signaling by degrading growth factor and growth factor receptor complexes in the endosomes and lysosomes (Table 2). Yet, such activity of cathepsins depends on the types of cathepsins, growth factors, and cells. In rat liver and human follicular thyroid carcinoma cell line FTC-133 and human glioma cell line LN-18, CatB mediated epidermal growth factor (EGF) and EGF receptor degradation in the endosomes [192, 193]. However, in human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells, CatL, but not CatB or CatH cleaved EGF receptor and affected downstream signaling and cell growth [194]. In mouse keratinocytes, it was also CatL that mediated EGF-EGF receptor complex degradation, leading to cell surface EGF accumulation [195]. Type 1 insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) is a well-known activator of proliferating tumor cells. In human breast and murine lung carcinoma cells, CatB-selective inhibitor CA-074Me blocked IGF-1 degradation, leading to abrogation of IGF-1 signaling and reduced IGF-1 receptors on cell surface [196]. In human prostate carcinoma cells, siRNA-mediated CatX depletion impaired the phosphorylation of IGF-1 receptor and downstream focal adhesion kinase signaling (p-FAK) in response to IGF-1 stimulation [197]. Besides these direct growth factor degradation, cathepsins also control cell signaling by indirect mechanism. In neurons, γ-enolase controlled neuronal survival, differentiation, and neurite regeneration by activating the MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways [198]. CatX abolished these signaling pathways by cleaving the γ-enolase C-terminal dipeptide [199]. Although many of these studies were carried in tumor cells, such cathepsin activities in EGF and IGF-1 degradation may also occur in vascular or inflammatory cells.

Fibroblasts play essential role in cardiac fibrosis and aortic wall matrix deposition. Although many cathepsins are collagenases and elastase, and also degrade laminin, fibronectin, and many other ECM in aortic wall and myocardium, recent studies suggest a role of cathepsins in ECM expression. In human skin BJ fibroblast cell line, LPS treatment for 24 hrs increased the expression of CatB but reduced the expression of collagens III and IV. CatB inhibition with CA-074Me completely blocked the role of LPS-induced reduction in collagen expression, suggesting a role of CatB in blocking fibroblast collagen synthesis. Mechanistic studies showed that CA-074Me increased the LPS-induced suppression of I-κBα, a NF-κB inhibitor. CatB mediates I-κBα degradation [200], thereby increasing NF-κB activity that inhibits downstream collagen expression [201, 202]. Therefore, CatB inhibition with CA-074Me reduced LPS-induced NF-κB activation and TLR-2 expression, leading to increased collagen synthesis. Together, these in vitro studies suggest that CatB plays essential roles in blocking LPS-induced TLR-2 activation and NF-κB signaling (Figure 4A). This hypothesis is consistent to the observation that primary skin fibroblasts from Ctsb−/− mice showed increased expression of collagens III and IV [200]. When invasive human melanoma cells cultured in matrigel/collagen I matrices were co-cultured with human embryonic or adult skin fibroblasts, invasive melanomas cells showed increased expression of CatB and CatL, MMP-1, MMP-9, and serine proteases uPA and tissue type plasminogen activator (tPA). Cell permeable CatB inhibitor CA-074Me and CatL inhibitor Z-FF-FMK but not cell impermeable CatB inhibitor CA-074 or pan MMP inhibitor GM6001 inhibited melanoma growth and invasion. In human melanoma cells, CatB inhibition with CA-074Me reduced the release of the 290-kDa TGF-β large latent complex to the cell culture medium (Figure 4B). Yet, this study did not test how CatB regulated TGF-β secretion [203]. The 290-kDa TGF-β large latent complex in the extracellular space is stored in the ECM and contains the 25-kDa mature homodimer, the 75-kDa latency-associated peptide, and the 190-kDa latent TGF-β binding protein-1 (LTBP1) (Figure 4B) [204]. TGF-β induces fibroblast differentiation into myofibroblasts, a major contributor of cardiac fibrosis. In human idiopathic pulmonary fibroblasts and human lung CCD-19Lu fibroblasts, TGF-β induces the expression of α-SMA, intracellular and extracellular CatB and CatL, and membrane-bound CatB. In CCD-19Lu fibroblasts, CatB inhibition or silencing with siRNA diminished α-SMA expression, delayed myofibroblasts differentiation, and led to intracellular accumulation of the small latent complex. Addition of CatB into the CatB siRNA-pretreated CCD-19Lu fibroblast lysate generated the 25-kDa mature forms of TGF-β (Figure 4B). CatB inhibition decreased Smad2/3 phosphorylation, but showed no effect on p38 MAPK and JNK phosphorylation [205]. These observations suggest that CatB activity is required for lung fibroblast TGF-β signaling, contradictory to what occurred in human skin BJ fibroblast [200] (Figure 4A). We recently reported from mouse kidney epithelial cells that both CatB and CatL negatively regulated the TGF-β signaling by blocking the activation of TGFBR1 by TGFBR2 and by blocking the import of p-Smad2/3 complex into the nuclei. In contrast, CatS and CatK acted completely opposite from CatB and CatL [48] (Figure 4C/2A). Therefore, different cathepsins may play different roles in TGF-β signaling, depending on the cell types. Fibroblasts from the myocardium and aortic wall are important sources of ECM. Cathepsin activity in TGF-β signaling in these fibroblasts may differ from those from the skin or lungs, a hypothesis that merits further investigation.

Figure 4.

Cell type-dependent cathepsin activities in TGF-β signaling and fibrotic protein synthesis. A. CatB degrades IκBα, enhances NF-κB activity, and blocks collagen expression in human skin BJ fibroblasts. B. In human melanoma cells, CatB promotes the secretion of TGF-β large latent complex to the extracellular space, where this complex is stored with ECM. CatB also produces the 25-kDa active form of TGF-β from the large latent complex in human lung fibroblasts. C. In mouse kidney epithelial cells, CatB and CatL act differently from CatS and CatK in mediating plasma membrane TGF-β receptor activation and nuclear membrane p-Smad2/3 complex shuttling between the cytosol and nucleus.

8. Future perspective of cathepsin research in CVD

The fact is that there is no single cathepsin inhibitor on the market for any types of diseases since we first isolated the human CatS and CatK more than 25 years ago [5, 206], although there are still dozens of on-going clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) to target these two cathepsins as we recently summarized [81]. It is our opinion that the failures in clinical trials may not be because of the efficacy or selectivity of these cathepsin inhibitors, but their side effects. We now have some explanations to these prior pre-clinical and clinical studies. As discussed above, CatB activity in TGF-β signaling and tissue fibrosis in human idiopathic pulmonary fibroblasts and human lung CCD-19Lu fibroblasts differs from that in mouse kidney epithelial cells and human skin BJ fibroblasts. Although not tested, cardiac fibroblasts may act the same as human lung fibroblasts in TGF-β signaling and collagen synthesis. CatB inhibition reduced cardiac fibrosis [207]. Inhibition of CatB activity in the heart seems beneficial to the heart, but may increase the risk of kidney fibrosis.

Our recent studies revealed an alternative and probably much safer method to use cathepsin inhibitors in experimental disease models. To CD4+ T cells or isolated regulatory T cells (Tregs), treatment with a CatK inhibitor [150] or CatS inhibitor overnight (Shi unpublished observation) increased the TGF-β/IL2-induced Treg differentiation, lifespan, and immunosuppressive activity against effector T cells in cell culture and in mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). To the SLE mice, adoptive transfer of Tregs pre-treated with a CatS or CatK inhibitor overnight effectively ameliorated SLE phenotypes. Surprisingly, cathepsin inhibitor pre-treated Tregs proliferated and remained their high immunosuppressive activity after three months in the recipient mice. Mechanistic studies revealed a role of CatS and CatK in endosomal TLR7 activation [150].

Prior studies in macrophages showed that CatB, CatK, CatL, and CatS produce functional endosomal TLR7 and TLR9 [34, 208–210]. TLR7 and TLR9 localize in the ER and bind to unc93b1 in resting cells. Upon stimulation with their cognate ligands, they traffic to endosomes/lysosomes to meet their ligand and initiate a signaling cascade via the adaptor molecules MyD88 [211–213]. TLR7 and TLR9 activation by exogenous or endogenous ligands impairs Treg generation and function by reducing de novo Treg generation from naïve T cells [214–218]. We have shown Treg deficiency in patients with cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and AAA [219–221] and Tregs protected mice from AAA development [221, 222]. Therefore, cathepsin inhibitor pre-treated Tregs as a therapeutic regimen may present a new use of cathepsin inhibitors in CVD and possible other Treg-deficient diseases, such as SLE and metabolic diseases.

Highlights.

Cathepsins act extracellularly and in various subcellular compartments.

Inflammation in CVD is a common mechanism to induce cathepsin expression.

Increased cathepsin expression in CVD patients serve as a biomarker or risk factor.

Cathepsin activity in fibrotic protein synthesis depends on the cell types.

Cathepsins play different roles in the aorta versus the myocardium.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants the National Institute of Health, USA [HL123568, HL60942, and AG058670 to GPS]. Dr. Xian Zhang is supported by the American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship #18POST34050043.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Turk V, Turk B, Turk D, Lysosomal cysteine proteases: facts and opportunities, EMBO J, 20 (2001) 4629–4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rossi A, Deveraux Q, Turk B, Sali A, Comprehensive search for cysteine cathepsins in the human genome, Biol Chem, 385 (2004) 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dubin G, Proteinaceous cysteine protease inhibitors, Cell Mol Life Sci, 62 (2005) 653–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Turk V, Bode W, The cystatins: protein inhibitors of cysteine proteinases, FEBS Lett, 285 (1991) 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shi GP, Munger JS, Meara JP, Rich DH, Chapman HA, Molecular cloning and expression of human alveolar macrophage cathepsin S, an elastinolytic cysteine protease, J Biol Chem, 267 (1992) 7258–7262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yasuda Y, Li Z, Greenbaum D, Bogyo M, Weber E, Bromme D, Cathepsin V, a novel and potent elastolytic activity expressed in activated macrophages, J Biol Chem, 279 (2004) 36761–36770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Turk B, Dolenc I, Turk V, Bieth JG, Kinetics of the pH-induced inactivation of human cathepsin L, Biochemistry, 32 (1993) 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Almeida PC, Nantes IL, Chagas JR, Rizzi CC, Faljoni-Alario A, Carmona E, Juliano L, Nader HB, Tersariol IL, Cathepsin B activity regulation. Heparin-like glycosaminogylcans protect human cathepsin B from alkaline pH-induced inactivation, J Biol Chem, 276 (2001) 944–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ishidoh K, Kominami E, Procathepsin L degrades extracellular matrix proteins in the presence of glycosaminoglycans in vitro, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 217 (1995) 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mason RW, Massey SD, Surface activation of pro-cathepsin L, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 189 (1992) 1659–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vasiljeva O, Dolinar M, Pungercar JR, Turk V, Turk B, Recombinant human procathepsin S is capable of autocatalytic processing at neutral pH in the presence of glycosaminoglycans, FEBS Lett, 579 (2005) 1285–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Caglic D, Pungercar JR, Pejler G, Turk V, Turk B, Glycosaminoglycans facilitate procathepsin B activation through disruption of propeptide-mature enzyme interactions, J Biol Chem, 282 (2007) 33076–33085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li Z, Kienetz M, Cherney MM, James MN, Bromme D, The crystal and molecular structures of a cathepsin K:chondroitin sulfate complex, J Mol Biol, 383 (2008) 78–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Novinec M, Kovacic L, Lenarcic B, Baici A, Conformational flexibility and allosteric regulation of cathepsin K, Biochem J, 429 (2010) 379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li Z, Hou WS, Bromme D, Collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is specifically modulated by cartilage-resident chondroitin sulfates, Biochemistry, 39 (2000) 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu J, Sukhova GK, Sun JS, Xu WH, Libby P, Shi GP, Lysosomal cysteine proteases in atherosclerosis, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 24 (2004) 1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang J, Cheng X, Xiang MX, Alanne-Kinnunen M, Wang JA, Chen H, He A, Sun X, Lin Y, Tang TT, Tu X, Sjoberg S, Sukhova GK, Liao YH, Conrad DH, Yu L, Kawakami T, Kovanen PT, Libby P, Shi GP, IgE stimulates human and mouse arterial cell apoptosis and cytokine expression and promotes atherogenesis in Apoe−/− mice, J Clin Invest, 121 (2011) 3564–3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu CL, Zhang X, Liu J, Wang Y, Sukhova GK, Wojtkiewicz GR, Liu T, Tang R, Achilefu S, Nahrendorf M, Libby P, Guo J, Zhang JY, Shi GP, Na(+)-H(+) exchanger 1 determines atherosclerotic lesion acidification and promotes atherogenesis, Nat Commun, 10 (2019) 3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reddy VY, Zhang QY, Weiss SJ, Pericellular mobilization of the tissue-destructive cysteine proteinases, cathepsins B, L, and S, by human monocyte-derived macrophages, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 92 (1995) 3849–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lemaire PA, Huang L, Zhuo Y, Lu J, Bahnck C, Stachel SJ, Carroll SS, Duong LT, Chondroitin sulfate promotes activation of cathepsin K, J Biol Chem, 289 (2014) 21562–21572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Felbor U, Dreier L, Bryant RA, Ploegh HL, Olsen BR, Mothes W, Secreted cathepsin L generates endostatin from collagen XVIII, EMBO J, 19 (2000) 1187–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Veillard F, Saidi A, Burden RE, Scott CJ, Gillet L, Lecaille F, Lalmanach G, Cysteine cathepsins S and L modulate anti-angiogenic activities of human endostatin, J Biol Chem, 286 (2011) 37158–37167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang B, Sun J, Kitamoto S, Yang M, Grubb A, Chapman HA, Kalluri R, Shi GP, Cathepsin S controls angiogenesis and tumor growth via matrix-derived angiogenic factors, J Biol Chem, 281 (2006) 6020–6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chen H, Wang J, Xiang MX, Lin Y, He A, Jin CN, Guan J, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Wang JA, Shi GP, Cathepsin S-mediated fibroblast trans-differentiation contributes to left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction, Cardiovasc Res, 100 (2013) 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Christensen J, Shastri VP, Matrix-metalloproteinase-9 is cleaved and activated by cathepsin K, BMC Res Notes, 8 (2015) 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McGuire MJ, Lipsky PE, Thiele DL, Purification and characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase I from human spleen, Arch Biochem Biophys, 295 (1992) 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Adkison AM, Raptis SZ, Kelley DG, Pham CT, Dipeptidyl peptidase I activates neutrophil-derived serine proteases and regulates the development of acute experimental arthritis, J Clin Invest, 109 (2002) 363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pham CT, Ley TJ, Dipeptidyl peptidase I is required for the processing and activation of granzymes A and B in vivo, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 96 (1999) 8627–8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wolters PJ, Pham CT, Muilenburg DJ, Ley TJ, Caughey GH, Dipeptidyl peptidase I is essential for activation of mast cell chymases, but not tryptases, in mice, J Biol Chem, 276 (2001) 18551–18556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Turk D, Janjic V, Stern I, Podobnik M, Lamba D, Dahl SW, Lauritzen C, Pedersen J, Turk V, Turk B, Structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C): exclusion domain added to an endopeptidase framework creates the machine for activation of granular serine proteases, EMBO J, 20 (2001) 6570–6582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Brix K, Dunkhorst A, Mayer K, Jordans S, Cysteine cathepsins: cellular roadmap to different functions, Biochimie, 90 (2008) 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Friedrichs B, Tepel C, Reinheckel T, Deussing J, von Figura K, Herzog V, Peters C, Saftig P, Brix K, Thyroid functions of mouse cathepsins B, K, and L, J Clin Invest, 111 (2003) 1733–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Brix K, Linke M, Tepel C, Herzog V, Cysteine proteinases mediate extracellular prohormone processing in the thyroid, Biol Chem, 382 (2001) 717–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ewald SE, Engel A, Lee J, Wang M, Bogyo M, Barton GM, Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase, J Exp Med, 208 (2011) 643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Garcia-Cattaneo A, Gobert FX, Muller M, Toscano F, Flores M, Lescure A, Del Nery E, Benaroch P, Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 109 (2012) 9053–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fonovic UP, Jevnikar Z, Kos J, Cathepsin S generates soluble CX3CL1 (fractalkine) in vascular smooth muscle cells, Biol Chem, 394 (2013) 1349–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pagano MB, Bartoli MA, Ennis TL, Mao D, Simmons PM, Thompson RW, Pham CT, Critical role of dipeptidyl peptidase I in neutrophil recruitment during the development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104 (2007) 2855–2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Boya P, Kroemer G, Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death, Oncogene, 27 (2008) 6434–6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Repnik U, Cesen MH, Turk B, The endolysosomal system in cell death and survival, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a008755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Droga-Mazovec G, Bojic L, Petelin A, Ivanova S, Romih R, Repnik U, Salvesen GS, Stoka V, Turk V, Turk B, Cysteine cathepsins trigger caspase-dependent cell death through cleavage of bid and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologues, J Biol Chem, 283 (2008) 19140–19150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kobayashi H, Moniwa N, Sugimura M, Shinohara H, Ohi H, Terao T, Effects of membrane-associated cathepsin B on the activation of receptor-bound prourokinase and subsequent invasion of reconstituted basement membranes, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1178 (1993) 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mai J, Finley RL Jr., Waisman DM, Sloane BF, Human procathepsin B interacts with the annexin II tetramer on the surface of tumor cells, J Biol Chem, 275 (2000) 12806–12812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rozhin J, Wade RL, Honn KV, Sloane BF, Membrane-associated cathepsin L: a role in metastasis of melanomas, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 164 (1989) 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nascimento FD, Rizzi CC, Nantes IL, Stefe I, Turk B, Carmona AK, Nader HB, Juliano L, Tersariol IL, Cathepsin X binds to cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans, Arch Biochem Biophys, 436 (2005) 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kos J, Jevnikar Z, Obermajer N, The role of cathepsin X in cell signaling, Cell Adh Migr, 3 (2009) 164–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Obermajer N, Svajger U, Bogyo M, Jeras M, Kos J, Maturation of dendritic cells depends on proteolytic cleavage by cathepsin X, J Leukoc Biol, 84 (2008) 1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Cheng XW, Kuzuya M, Nakamura K, Di Q, Liu Z, Sasaki T, Kanda S, Jin H, Shi GP, Murohara T, Yokota M, Iguchi A, Localization of cysteine protease, cathepsin S, to the surface of vascular smooth muscle cells by association with integrin alphanubeta3, Am J Pathol, 168 (2006) 685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang X, Zhou Y, Yu X, Huang Q, Fang W, Li J, Bonventre JV, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Shi GP, Differential Roles of Cysteinyl Cathepsins in TGF-beta Signaling and Tissue Fibrosis, iScience, 19 (2019) 607–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI, Chapman HA, Libby P, Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells, J Clin Invest, 102 (1998) 576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Liu J, Sukhova GK, Yang JT, Sun J, Ma L, Ren A, Xu WH, Fu H, Dolganov GM, Hu C, Libby P, Shi GP, Cathepsin L expression and regulation in human abdominal aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and vascular cells, Atherosclerosis, 184 (2006) 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Fang W, He A, Xiang MX, Lin Y, Wang Y, Li J, Yang C, Zhang X, Liu CL, Sukhova GK, Barascuk N, Larsen L, Karsdal M, Libby P, Shi GP, Cathepsin K-deficiency impairs mouse cardiac function after myocardial infarction, J Mol Cell Cardiol, 127 (2019) 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Jormsjo S, Wuttge DM, Sirsjo A, Whatling C, Hamsten A, Stemme S, Eriksson P, Differential expression of cysteine and aspartic proteases during progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice, Am J Pathol, 161 (2002) 939–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sasaki T, Kuzuya M, Nakamura K, Cheng XW, Hayashi T, Song H, Hu L, Okumura K, Murohara T, Iguchi A, Sato K, AT1 blockade attenuates atherosclerotic plaque destabilization accompanied by the suppression of cathepsin S activity in apoE-deficient mice, Atherosclerosis, 210 (2010) 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jaffer FA, Kim DE, Quinti L, Tung CH, Aikawa E, Pande AN, Kohler RH, Shi GP, Libby P, Weissleder R, Optical visualization of cathepsin K activity in atherosclerosis with a novel, protease-activatable fluorescence sensor, Circulation, 115 (2007) 2292–2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cheng XW, Obata K, Kuzuya M, Izawa H, Nakamura K, Asai E, Nagasaka T, Saka M, Kimata T, Noda A, Nagata K, Jin H, Shi GP, Iguchi A, Murohara T, Yokota M, Elastolytic cathepsin induction/activation system exists in myocardium and is upregulated in hypertensive heart failure, Hypertension, 48 (2006) 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Helske S, Syvaranta S, Lindstedt KA, Lappalainen J, Oorni K, Mayranpaa MI, Lommi J, Turto H, Werkkala K, Kupari M, Kovanen PT, Increased expression of elastolytic cathepsins S, K, and V and their inhibitor cystatin C in stenotic aortic valves, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 26 (2006) 1791–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Shi GP, Sukhova GK, Kuzuya M, Ye Q, Du J, Zhang Y, Pan JH, Lu ML, Cheng XW, Iguchi A, Perrey S, Lee AM, Chapman HA, Libby P, Deficiency of the cysteine protease cathepsin S impairs microvessel growth, Circ Res, 92 (2003) 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Keegan PM, Surapaneni S, Platt MO, Sickle cell disease activates peripheral blood mononuclear cells to induce cathepsins k and v activity in endothelial cells, Anemia, 2012 (2012) 201781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Keegan PM, Wilder CL, Platt MO, Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates cathepsin K and V activity via juxtacrine monocyte-endothelial cell signaling and JNK activation, Mol Cell Biochem, 367 (2012) 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jiang H, Cheng XW, Shi GP, Hu L, Inoue A, Yamamura Y, Wu H, Takeshita K, Li X, Huang Z, Song H, Asai M, Hao CN, Unno K, Koike T, Oshida Y, Okumura K, Murohara T, Kuzuya M, Cathepsin K-mediated Notch1 activation contributes to neovascularization in response to hypoxia, Nat Commun, 5 (2014) 3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Jo H, Laminar shear stress inhibits cathepsin L activity in endothelial cells, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 26 (2006) 1784–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Parker IK, Roberts LM, Hansen L, Gleason RL Jr., Sutliff RL, Platt MO, Pro-atherogenic shear stress and HIV proteins synergistically upregulate cathepsin K in endothelial cells, Ann Biomed Eng, 42 (2014) 1185–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Shi GP, Weiss D, Vega JD, Taylor WR, Jo H, Expression of cathepsin K is regulated by shear stress in cultured endothelial cells and is increased in endothelium in human atherosclerosis, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 292 (2007) H1479–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Ebisui C, Tsujinaka T, Morimoto T, Kan K, Iijima S, Yano M, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Monden M, Interleukin-6 induces proteolysis by activating intracellular proteases (cathepsins B and L, proteasome) in C2C12 myotubes, Clin Sci (Lond), 89 (1995) 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]