Abstract

Objective:

The use of behavioral interventions has been shown to improve glycemic control, however, the effectiveness of different behavioral interventions in one of the most high risk populations, African Americans, remains unclear. This systematic review identified and examined findings of published behavioral interventions targeted at African Americans to improve glycemic control. The goal of this study was to distinguish which interventions were effective and identify areas for future research.

Design:

Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL were searched for articles published between January 2000 through January 2012 using a reproducible strategy. Study eligibility criteria included interventions aimed at changing behavior in adult African Americans with type 2 diabetes and measured glycemic control.

Results:

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria, of which five showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c in the intervention group when compared to the control group. Summary information and characteristics of the reviewed studies are provided.

Conclusions:

Characteristics of successful interventions included using problem solving with the patient, culturally tailoring the intervention, and using a nurse educator. Limitations include the limited number of intervention studies available using glycemic control as the outcome measure. Clinical trials are needed to determine how best to tailor interventions to this largely underserved population and studies should describe details of cultural tailoring to provide information for future programs.

Keywords: Diabetes, glucose control, African Americans, ethnic groups, lifestyle

INTRODUCTION

Ethnic Differences in Burden of Diabetes

Diabetes affects 25.8 million people, or 8.3% of the United States (US) population, and is the seventh leading cause of death in the US [1]. It is the leading cause of kidney failure, nontraumatic lower-limb amputations, new cases of blindness among adults, heart disease and stroke [1]. Ninety percent of all cases of diabetes are categorized as type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [2]. Overall estimated cost in the US in 2007 was $174 billion [1] and is predicted to increase to $192 billion by 2020 [3]. Rates are steadily increasing and it is estimated that globally, by 2030, 522 million people will be diagnosed [4,5]. Due to the prevalence and economic burden of diabetes, it is considered one of the most challenging health problems of the 21st century [5].

While T2DM is a concern for all racial and ethnic groups, ethnic minorities show an increased prevalence, risks of complications, and mortality [1,6,7]. Compared to non-Hispanic White (NHW) adults, the risk of diagnosed diabetes is 77% higher among non-Hispanic Blacks (NHB), 66% higher in Hispanic/Latinos, and 18% higher in Asian Americans [1]. Once diagnosed, African Americans are 2.6 times more likely to develop end-stage renal disease and more likely to undergo a lower-limb amputation [6]. Additionally, the average life years lost by diagnosis for NHB women is 12 years and NHB men is 9.3 years [8].

Evidence suggests that minority populations tend to have poorer self-management and outcomes as compared to NHWs, increasing the already disproportionate burden of disease and adding to the disparity in diabetes related complications [9]. African Americans in particular tend to exhibit worse outcomes, including glycemic control, when compared to other minority populations and NHWs [9].

Impact of Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes such as exercise, diet, and medication adherence have been shown to alter the course of disease progression through improving glycemic control [10–14]. Reduced risk of diabetes-related complications, including nephropathy and myocardial infarction have been shown to be associated with HbA1c below 7 percent [1]. However, while a person’s cultural context has the potential to impact their self-management, studies have not adequately targeted minorities [7,13,14].

Previous reviews have shown that the most successful interventions are aimed at changing behavior rather than knowledge [13]. Using behavioral interventions has been shown to improve glycemic control and quality of life in patients with T2DM [1,10–12]. Nevertheless, there are still gaps in understanding the effectiveness of different behavioral interventions in African Americans and which aspects are most significant [7, 13].

As no review exists providing information on interventions in African Americans, a literature review was conducted to systematically examine the results of published articles to answer whether behavioral inverventions targeted at African Americans are effective at improving glycemic control. The goal of this study was to identify effective interventions and areas for future research.

METHODS

Information sources, eligibility criteria and search

Three databases (Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL) were searched for articles published between January 2000 through January 2012 using a reproducible strategy. Three searches with broad search terms were performed in each database using MeSH headings search. The first search used the MeSH headings diabetes and ethnic groups, the second used diabetes and lifestyle, and the third used diabetes and community.

The following inclusion criteria were used to determine eligible study characteristics: (1) published in English, (2) targeted African American adults, ages 18+ years, (3) described an intervention, (4) the intervention was aimed at changing behavior, and (5) the intervention measured change in glycemic control as determined by HbA1c. For the purposes of this review, an article was considered to have targeted African Americans if at least 70% of the sample were Black or African American. Studies were classified as behavioral interventions if they focused on modifying one or more diabetes-relevant behaviors including diet, physical activity, self-monitoring, medication adherence, smoking, weight loss or stress/coping. Glycemic control was chosen as a required outcome measure because it is associated with successful self-care behaviors and lower rates of disease progression [1].

Study selection and data collection

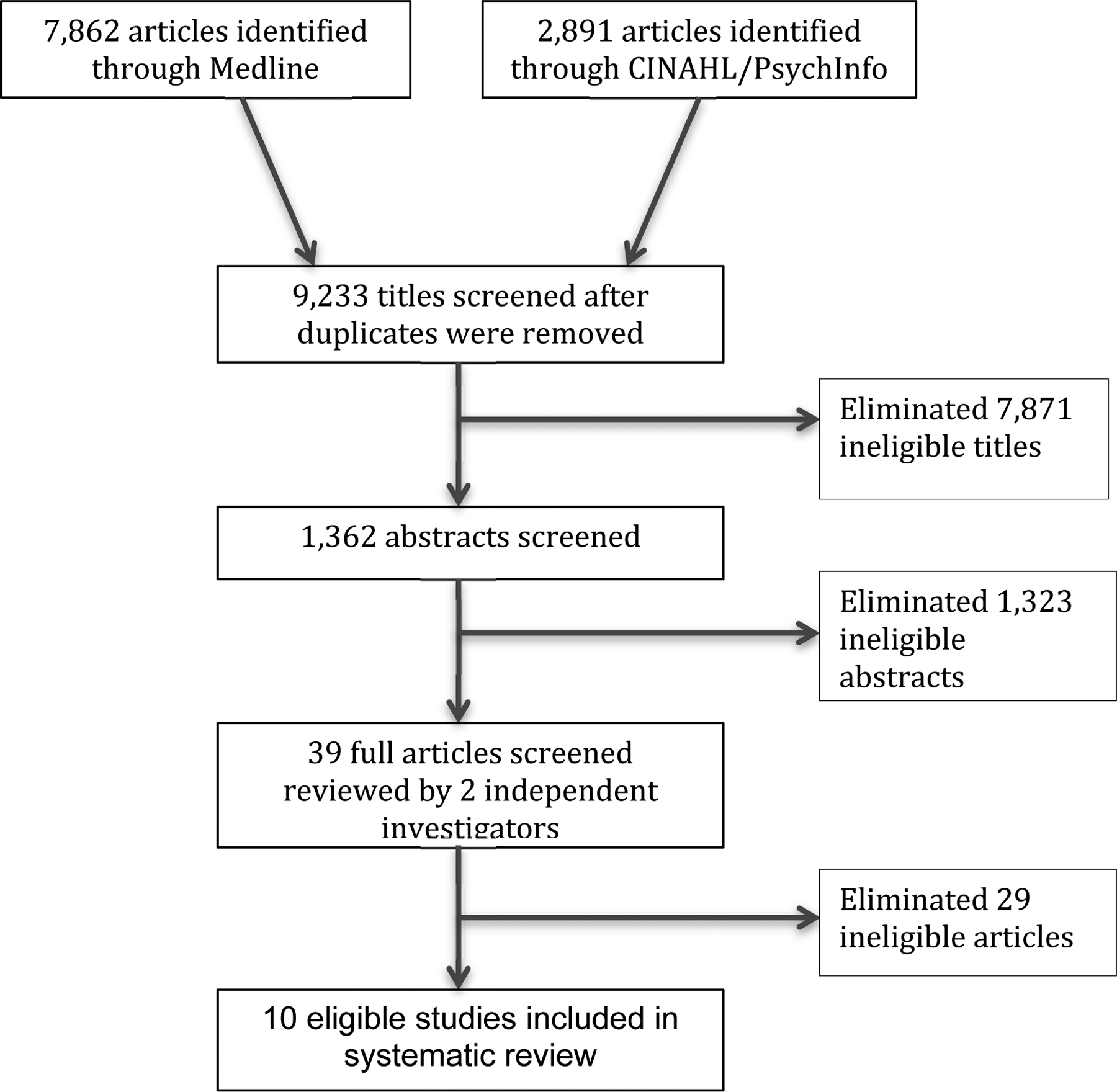

The process used to screen the citations is shown in Figure 1. Titles were eliminated if they were obviously ineligible, for instance describing Type 1 diabetes, gestational diabetes, diabetes prevention studies or targeting ethnic groups other than African Americans. Full articles were read and reviewed using a standardized check-list by two independent reviewers (RW, BS). A senior topic expert (LE) acted as a third independent reviewer and made the final decision regarding eligibility in the case of disagreement.

Figure 1:

Process for eligible article selection

Data collected from the eligible articles is shown in Tables 1–4. Since there were few intervention studies that targeted African Americans available, we included Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies, with and without a control arm. Data was extracted on the number of participants, sample population, duration of intervention, setting of intervention, study design, type of control, major findings, and limitations for the study (Table 1). An outcome table was created to include the mean baseline HbA1c, mean change (or baseline and post intervention if not reported), and statistical significance (Table 2). Details of the interventions are presented including theoretical basis, intervention description, and follow-up (Table 3). Each article was also analyzed for relevant intervention characteristics, including whether it was culturally tailored, included one-on-one counseling, group counseling, or telemedicine, involved nurse or diabetes educators, focused on nutrition or supervised exercise, and allowed for problem solving with the patient (Table 4). A narrative review was performed as the heterogenous interventions and diverse study designs precluded conducting a meta-analysis. Though risk of bias exists, articles were not excluded due to the limited evidence available in the literature. The risk of bias across studies is discussed in the limitations.

Table 1:

Summary of Interventions

| Characteristics | Studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study author, year | Anderson, 2005 | Anderson-Loftin, 2002 | Carter, 2011 |

| Participants (completed) | 239 | 23 (16) | 74 (47) |

| Sample population | Urban African American | Rural African American | Inner city African American |

| Intervention Duration | 6 weeks | 5 months | 9 months |

| Intervention Setting | Community based location | Rural SC | Online |

| Study design | RCT pretest/posttest | Longitudinal quasi-experimental | RCT |

| Type of control | Wait list (standard care) | None | Standard care |

| Major findings | No difference between control and intervention except diabetes understanding; positive pre/post changes in HbA1c | Intervention was effective in improving HbA1c, costs and dietary habits | Effective telehealth intervention; increase in self-care, mental and physical well being |

| Limitations | Volunteer bias; effects of providing study data to patients | Small sample size; no control | Access to internet; cost; small sample; ability to read |

| Study author, year | Davis, 2010 | Hawkins, 2010 | Mayer-Davis, 2004 |

| Participants (completed) | 165 | 77 (66) | 187 (152) |

| Sample population | Low-income, overweight, predominantly African American | Rural, predominantly African American, 60+ | Overweight, predominantly African American, 45+ |

| Intervention Duration | 1 year | 6 months | 12 months |

| Intervention Setting | Telehealth, community health center | Videophone | Rural health care center |

| Study design | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Type of control | Standard care – 20-min education session | No reminder calls; good health handouts; 5-min monthly calls | Standard care, one individualized session |

| Major findings | Effective multicomponent telehealth strategy to rural and underserved populations | Access to individualized diabetes education; all improved HbA1c | Weight loss was significant for intensive group; no difference for reimbursable level; weight loss not predictive of HbA1c |

| Limitations | Only federally qualified health care setting | Sample size limited; technology needs to fit audience | No self-care measure |

| Characteristics | Studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study author, year | Rimmer, 2002 | Tang, 2010 | Walker, 2010 | Weinstock, 2011 |

| Participants (completed) | 30 | 77 (12 drop-outs) | 195 | 1665 |

| Sample population | Inner-city, predominantly African Americans | African American, 40+ | African American, 40+ | Underserved, ethnically diverse |

| Intervention Duration | 12 weeks | 6 months | 6 months | 5 years |

| Intervention Setting | Local hospital and clinic | In person and mailings | In person and telephone | Telemedicine |

| Intervention description | ||||

| Study design | Quasi-experimental | Control-intervention time series (subjects as own control) | Quasi-experimental | RCT |

| Type of control | None | Attention-control, weekly newsletters | Standard care | Standard care |

| Major findings | Intensive and highly structured intervention was successful in underserved population | Control served as low intensity intervention; flexible model is promising | Increase in knowledge maintained for 6-mo; stages of change increased for exercise though no change in behavior | Persistent benefit of telemedicine may reduce disparities |

| Limitations | Barriers to participation | No real control | Group differences; small comparison group | HbA1c not similar at baseline |

RCT = randomized controlled trial

Table 4:

Characteristics of Interventions

| Study Author, Year | Culturally Tailored | One-on-one Counseling | Group Counseling | Telemedicine | Problem Solving with Patient | Nurse Educators | Certified Diabetes Educator | Dietician | Information to Provider | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, 2005 | x | x | x | x | x | NS | ||||

| Anderson-Loftin, 2002 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Carter, 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Davis, 2010 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Hawkins, 2010 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Mayer-Davis, 2004 | x | x | x | x | NS | |||||

| Rimmer, 2002 | x | x | x | x | x | NS | ||||

| Tang, 2010 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Walker, 2010 | x | x | x | NS | ||||||

| Weinstock, 2011 | x | x | x | x | x | NS |

NS=not significant

Table 2:

Outcomes of Interventions

| Study author, year | Mean baseline A1C, % | Intervention mean change in A1C, % | Control mean change in A1C, % | Statistical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, 2005 | 8.6 | 8.74 baseline; 8.34 post intervention |

8.41 baseline; 8.13 post intervention |

No sign difference; sign pre/post decrease in HbA1c (p<0.001) |

| Anderson-Loftin, 2002 | 50% elevated levels | Decreased 1.18 | No control | P=0.0106 |

| Carter, 2011 | 8.9 | 9.0 baseline; 6.82 post intervention |

8.8 baseline; 7.9 post intervention |

P<0.05 OR=4.58 to reach A1c<7 if in intervention |

| Davis, 2010 | 9.3 (intervention); 8.9 (control) |

9.4 baseline; 8.3 6-mo post; 8.2 12-mo post |

8.8 baseline; 8.6 6-mo post intervention; 8.6 12-mo post |

P=0.003 6-mo P=0.004 12-mo |

| Hawkins, 2010 | 8.95 | Decreased 1.7 | Decreased 0.6 | P=0.015 |

| Mayer-Davis, 2004 | 9.6 (usual care); 9.7 (reimbursable care); 10.2 (intensive care) |

Decreased 0.8 reimbursable; Decreased 1.6 intensive | Decreased 1.1 | Not significant |

| Rimmer, 2002 | 10.8 | 10.8 baseline; 10.3 post intervention |

No control | No significant difference |

| Tang, 2010 | 8.2 (intervention); 7.9 (control) |

Decreased 0.68 | Increased 0.32 | P=0.008 |

| Walker, 2010 | 41% elevated levels | 39% elevated levels | Not reported | Not significant |

| Weinstock, 2011 | 7.02 (White); 7.58 (Black); 7.79 (Hispanic) |

7.10 baseline, 6.87 5-yr post (White); 7.61 baseline, 6.95 5-yr post (Black); 7.69 baseline, 7.32 5-yr post (Hispanic) |

6.97 baseline; 6.93 5-yr post (White); 7.56 baseline, 7.20 5-yr post (Black); 7.94 baseline, 7.82 5-yr post (Hispanic) |

Treatment effect not significant (Black, White) Treatment effect 0.50 (95%CI 0.22–0.78) (Hispanic) |

Table 3:

Intervention details

| Study author, year | Theoretical Basis | Intervention description | Data collection | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, 2005 | Empowerment | Six weekly 2-hr group sessions conducted by nurse and dietician focused on self-management. Focus based on patient-identified problems, questions used to initiate discussion. | Baseline, after six-week sessions, after six-week control, 6-mo, 12-mo | Option of monthly support group or monthly phone call from nurse after six week study. |

| Anderson-Loftin, 2002 | Model of Nursing Case Management | Nurse case manager provided basic diabetes information and counseled on practices. Four 1-hr dietary classes every 2-wks. Four 30-min group discussions after class included social event, cooking demos, storytelling, role modeling. | Baseline, 5 months postintervention | Weekly phone calls and single home visit. Five 1-hr monthly group discussions postintervention. |

| Carter, 2011 | Coordinated service delivery | Access to online self-management tools/modules, patient records, health education and social networking. Bi-weekly 30-min videoconference with nurse to develop action plans | Baseline, 9-mo | None |

| Davis, 2010 | Health Beliefs Model; Transtheoretical | Twelve-month education through 3 independent and 10 group sessions. Three group sessions in person, others videoconference with nurse and dietician. Participants completed self-monitoring logs and had access to education curriculum. | Baseline, 6-mo, 12-mo | 24-mo on 2/3 or randomized sample |

| Hawkins, 2010 | Motivational interviewing | 15-min weekly videophone call with nurse for 3-mo, then 15-min monthly calls for 3-mo. Patient-selected topic from packets read before session, discussion focused on experiences, emotion, problem-solving and clinical questions. | Baseline, 6-mo | None |

| Mayer-Davis, 2004 | Empowerment | Participants given goal of 10% weight loss and randomized into intensive intervention, reimbursable level intervention or usual care. Intensive: 4-mo of weekly counseling sessions using curriculum composed of behavioral strategies, then biweekly for 2 months, then monthly for 6 months. 3 group sessions and 1 individual session pattern. Reimbursable: 4 1-hr sessions over 12 months; 3 group, 1 individual. | Baseline, 3-mo, 6-mo, 9-mo | None |

| Rimmer, 2002 | Health promotion | 12-weeks of 3-days/wk, 3-hrs/day including structured exercise, nutrition instruction, and health education. Presentation and group discussions used to facilitate development of support relationships and incorporate approaches into daily lives. | Baseline, 12-wk | None |

| Tang, 2010 | Empowerment | 24-months of weekly sessions facilitated by diabetes educator and clinical psychologist directed by patient questions, concerns and priorities focusing on experience, emotion, problem-solving, and goal setting. | Baseline, 6-mo | 24-months |

| Walker, 2010 | Health Promotion; Transtheoretical | Three 2-hr interactive group sessions focused on diabetes knowledge, exercise and diet, medications and treatment. | Baseline, 3-mo, 6-mo | Phone calls weekly for 1 mo., bi-monthly for 2 mo., every other month for 2 mo. |

| Weinstock, 2011 | None stated | Videoconference with diabetes educator every 4–6 weeks for self-care education and goal setting. Access to educational web pages. Home measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose. | Baseline, 6-mo, 12-mo | Yearly for 5 years |

RESULTS

Study selection

Figure 1 shows the results of the search. After duplicates were removed, the search resulted in 9,233 citations. Title review produced 1,362 abstracts to examine, after which 39 articles were determined eligible for full article review. Ten eligible studies were identified based upon the predetermined eligibility criteria [15–24].

Study characteristics and results of individual studies

Tables 1 and 2 provide a summary of the ten studies that met eligibility criteria. Sample sizes ranged from 23 to 1,665, intervention duration ranged from 6 weeks to 5 years, and mean baseline HbA1c ranged from 7.58 to 10.8. Three of the studies focused on urban/inner-city population [15,17,21] and two focused on rural populations [16,19]. Five included only African Americans [15–17,22,23], four included predominantly African Americans [18–21], and one analyzed the African American population separately from other ethnic/racial groups [24]. Six of the ten were RCTs [15,17–20,24], three were quasi-experimental [16,21,23], and one was a time-series [22]. Eight of the ten studies used a control group [15,17–20,22–24]. Of these eight, four reported statistically significant improvements in HbA1c in the intervention group compared with the control. [17–19,22] Of the two studies without a control group, one reported statistically significant change in HbA1c [16].

Intervention characteristics of the ten studies are provided in Tables 3 and 4. Three studies used an empowerment theoretical basis [15,20,22], one used motivational interviewing [19], one used health beliefs model [18], two used transtheoretical model [18,23], two used health promotion [21,23], one used nursing case-management [16] and one used coordinated service delivery [17]. Five of the ten studies specifically stated being culturally tailored [15–18,20]. Seven provided one-on-one counseling [17–20,22,23], five provided group counseling [15,16,18,20,21], and four were delivered through telemedicine [17–19,24]. Nine of the ten interventions involved problem solving with the patient, through development of action plans or question based discussion [15–19,21–24]. Six used nurse educators [15–19,21], five used certified diabetes educators [15,18,21,22,24], four used dieticians [16,20,21,23], and four provided information to the patient’s provider [16,17,22,24].

Five of the studies were statistically significant. Of these, five involved problem solving, three were culturally tailored [16–18], four used a nurse educator [16–19], two used a certified diabetes educator [18,22], one used a dietician [16], and three provided information to the provider [16,17,22]. Statistically significant results were found in three of the four telemedicine interventions [17–19], two of the five group counseling interventions [16,18], and four of the seven one-on-one counseling interventions [17–19,22].

DISCUSSION

Summary of evidence

This systematic review identified effective behavioral interventions in African Americans with T2DM based on the impact on glycemic control. Using a reproducible search strategy, 9,233 articles were reviewed. Ten articles met inclusion criteria and five showed a statistically significant change in HbA1c in the intervention group, compared to the control group. Five of the ten studies specifically noted cultural tailoring, three of which were significant. All studies with statistically significant results used problem solving with the patient, four used a nurse educator, three provided information to the provider, three were delivered via telemedicine, four provided one-on-one counseling, and two provided group counseling sessions.

A noteworthy aspect of the studies reviewed was problem solving - defined as both a cognitive and behavioral process to find solutions [25]. Self-management behaviors have been associated with positive problem solving skills [26–28], however, not all studies have found this association significant [29]. In the studies reviewed, some interventions addressed problem solving through structured processes such as action plans and goal setting, while others used open-ended questions and time for discussion of patient concerns. Few studies have looked specifically at the impact of problem solving in patients with diabetes on glycemic control. This review found that interventions consistently allowed for problem solving and half improved glycemic control, indicating it may be a critical aspect when engaging African Americans with T2DM.

Cultural tailoring of interventions has been shown to improve outcomes, and was evidenced in this review [10,30,31]. Of the five studies that specifically noted cultural tailoring, three found statistically significant changes in HbA1c, however, few gave details regarding how interventions were tailored. Among studies that detailed culturally appropriate interventions, techniques included modifying dietary suggestions for practical and cultural acceptance, providing demonstrations, discussing food choices at social events, and using local healthcare providers [16].

All studies reviewed used either nurse educators, certified diabetes educators, or dieticians, and four noted providing information to the healthcare provider, as recommended by national standards for DSME [10]. Nurse educators seemed to be most effective, being used in four of the five statistically significant studies. Since African Americans have been shown to have lower levels of trust in health care providers [32], the specific type of education provider may be important in intervention effectiveness. Benkert et al found significantly higher trust in African American patients with hypertension seen by nurse practitioners than those seen by medical doctors [33].

Considering the large number of behavioral intervention studies, few studies targeting African Americans and measuring the impact on glycemic control were found. African Americans are more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes, and have been shown to have greater disability from diabetes complications than NHWs [6]. In addition, patients with diabetes in the US have been shown to have twice the medical costs of those without [1]. Only ten studies were found in this review and of those that were statistically significant only three had a separate control group. This is an insufficient level of evidence to inform wide-scale behavior interventions and suggests more work is needed to develop effective behavioral interventions for African Americans with T2DM. Addtionally, while cultural tailoring of interventions has been shown to be effective [10,30,31], only half of the studies reviewed noted use of this technique. This review provides a summary of the evidence, which can serve as a starting point for development of clinical trials in the future.

Limitations

There are four limitations to this study worth addressing. First, the search was limited to articles published in English between 2000 and 2012. Second, the review was limited to studies using glycemic control as an outcome. While this is an important risk factor for disease progression, it limited the number of interventions examined. Future studies should investigate the impact of behavioral interventions on other outcomes, such as quality of life. Third, since studies with positive results are more likely to be published, the studies in this review may reflect publication bias. Lastly, the small number of RCTs and heterogeneous methodology prevented a meta-analysis from being performed. Conclusions from this review are therefore qualitative and meant to guide future research rather than serve as conclusive answers.

Conclusions

Based on this review, future research should continue testing the effectiveness of behavioral interventions in African Americans. Studies should investigate whether incorporating problem solving improves glycemic control over providing information without efforts to improve problem solving. Studies should be clear in their description of methods used, such as how to encourage problem solving or details of cultural tailoring. Future studies should also investigate the possible link between trust and DSME effectiveness, specifically investigating the association between outcomes and the type of professional delivering an intervention. Additionally, studies on the impact of feedback to providers and changes in patient trust levels or patient-provider interactions would be informative. A recent review on the effectiveness of provider reminders showed that modest improvements are seen in provider behavior when interventions use reminders [34]. This review was not specific to diabetes, but supports this may be important.

In conclusion, an extensive search of the literature resulted in only ten studies being identified as targeting African Americans with T2DM for behavioral interventions to improve glycemic control as measured by HbA1c. Based on these studies, those that include problem solving with patients, culturally tailored information, and nurse educators are effective. Clinical trials are needed to determine how best to tailor interventions to this largely underserved population and studies should describe details of cultural tailoring to provide information for future programs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. DHHS, CDC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2005;28:S37–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogan P, Dall T, Nikolov P. Economic costs of diabetes in the US in 2002. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:917–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle JP, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KMV, et al. Projection of diabetes burden through 2050: impact of changing demography and disease prevalence in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2011;24(11):1936–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 5th edn Brussels, Belgium: IDF, 2011. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egede LE, Dagogo-Jack S. Epidemiology of Type 2 diabetes: focus on ethnic minorities. Med Clin N Am. 2005;89:949–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall MC. Diabetes in African Americans. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorenson SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk of diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Egede LE. Glucose control in diabetes: the impact of racial differences on monitoring and outcomes. Endocrine. 2012;42(3):471–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl1):S87–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gary TL, Genkinger JM, Guallar E, Peyrot M, Brancati FL. Meta-analysis of randomized educational and behavioral interventions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2003;29(3);488–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkisian CA, Brown AF, Norris KC, Wintz RL, Manglone CM. A systematic review of diabetes self-care interventions for older, African American or Latino adults. The Diabetes Educator. 2003;29(3):467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin JA, Black SA, Satish S. Aging versus disease: the opinions of older black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white Americans about the causes and treatment of common medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Nwankwo R, Gillard ML, Oh M, Fitzgerald T. Evaluating a problem-based empowerment program for African Americans with diabetes: results of a randomized controlled trial. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson-Loftin W, Barnett S, Sullivan P, Summers Bunn P, Tavakoli A. Culturally competent dietary education for southern rural African Americans with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2002;28:245–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter EL, Nunlee-Bland G, Callender C. A patient-centric, provider-assisted diabetes telehealth self-management intervention for urban minorities. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2011;8;1b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis RM, Hitch AD, Salaam MM, Herman WH, Zimmer-Galler IE, Mayer-Davis EJ. TeleHealth improves diabetes self-management in an underserved community. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(8);1712–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins SY. Improving glycemic control in older adults using a videophone motivational diabetes self-management intervention. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2010;24(4):217–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer-Davis EJ, D’Antonio AM, Smith SM, et al. Pounds off with empowerment (POWER): a clinical trial of weight management strategies for black and white adults with diabetes who live in medically underserved rural communities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):1736–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimmer JH, Silverman K, Braunschweig C, Quinn L, Liu Y. Feasibility of a health promotion intervention for a group of predominantly African American women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2002;28:571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander JE. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(2):178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker EA, Stevens KA, Persaud S. Promoting diabetes self-managemetn among African Americans: an educational intervention. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:169–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, Goland R, et al. The IDEATel Consortium. Glycemic control and health disparities in older ethnically diverse underserved adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Problem-solving therapy: a positive approach to clinical intervention. 2007. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, DeVellis BM, DeVellis RF. Health coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: a systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:1080–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hills-Briggs F, Yeh HC, Gary TL, Batts-Turner M, D’Zurilla T, Brancati FL. Diabetes problem-solving scale development in an adult, African American sample. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(2):291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King DK, Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, et al. Self-efficacy, problem solving, and social-environemtnal support are associated with diabetes self-management behaviors. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):751–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt CW, Grant JS, Pritchard DA. An empirical study of self-efficacy and social support in diabetes self-management: implications for home healthcare nurses. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2012;30(4):255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities. A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(suppl1):181–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawthorne K, Robles Y, Cannings-John R, Edwards AG. Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes mellitus in ethnic minorities. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(3):CD006424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes Halbert C, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Shaker L. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benkert R, Peters R, Tate N, Dinardo E. Trust of nurse practitioners and physicians among African Americans with hypertension. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(5):273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheung A, Wier MC, Mayhew A, Kozloff N, Brown K, Grimshaw J. Overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of reminders in improving healthcare professional behavior. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1(36). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]