Abstract

The treatment of massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears remains a challenge for shoulder surgeons. When treating patients with chronic rotator cuff tears, especially those with severe fatty degeneration, severe tendon retraction, or muscle atrophy, the risk of re-tear and persistent severe pain persists. Therefore, surgeons can choose from numerous options. Superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) was introduced as a technique to maintain the stability of the upper shoulder and stabilize the muscles without repairing the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Various autograft and allograft techniques have been developed. SCR performed using an autograft has the disadvantage of requiring harvesting the tensor fascia lata. Although allografts reduce harvest time, they also increase donor-site morbidity and the time required for healing. To solve the healing problem, we have introduced an SCR technique through grafting with the Achilles tendon–bone. Although this is an unproven technique for patients with chronic irreparable rotator cuff tears, our short-term outcomes seem promising. Further studies and follow-ups are needed to determine the success of this technique.

Introduction (With Video Illustration)

The treatment of chronic massive rotator cuff tears is challenging for shoulder surgeons. When treating patients with chronic rotator cuff tears, particularly those with severe fatty degeneration, severe tendon retraction, or muscle atrophy, the risk of re-tear and persistent severe pain remains. Many treatment options have been proposed for treating patients with chronic, massive, and irreparable rotator cuff tears.1, 2, 3

Recently, a surgical procedure called superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) was described by Mihata et al.,4 who reported promising short-term clinical outcomes in 24 shoulders (23 consecutive patients) with symptomatic irreparable rotator cuff tears. Since then, studies on SCR have been conducted, and various techniques have been introduced that use the tensor fascia lata as an autograft or the acellular derma graft as an allograft. Determining whether an allograft or autograft is best for reconstruction surgery is important for each patient. Recovery time, pain, stability, strength, and infection should be considered when choosing a graft. The advantages and disadvantages of each technique have been reported. Allografts pose a risk of immune response and disease transmission in the implants, and they are expensive.5,6 However, they have a significant advantage: no donor-site morbidity. However, studies on which technique or graft is better are lacking. Lim et al.7 reported a study on graft tear and confirmed graft tear on magnetic resonance imaging in 9 of 31 patients (29%) who underwent SCR using the fascia lata autograft. All 9 patients had tears in the medial and lateral rows of the greater tuberosity footprint; no graft failure was observed in the glenoid anchor site. Thus, we hypothesize that the tear rate would be greater with grafts of the greater tuberosity than of the glenoid and propose a method to provide a stronger fixation force. Here, we describe another technique of SCR through allografts using the Achilles tendon–bone in patients with massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears (Video 1).

Surgical Technique

Operative Indications

Indications for this surgery include young or active patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears, no or minimal glenohumeral arthritic wear, and good bone stock for anchor fixation. Younger patients with little cartilage wear and symptoms associated with primarily irreparable cuff tears may be considered for SCR instead of arthroplasty. Magnetic resonance imaging findings should be consistent with those of irreparable rotator cuff tendon tears and demonstrate retraction beyond the glenoid, along with grade 3 or greater changes of the supraspinatus or grade 2 or greater changes of the infraspinatus on sagittal oblique imaging.8 However, in addition to the results of preoperative examination, another crucial factor is the time for operation to confirm that the rotator cuff tear cannot be repaired. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to confirm the irreparable nature of tears because the retracted tendon cannot be brought back to the original footprint on the greater tuberosity.

Patient Positioning and Anesthesia

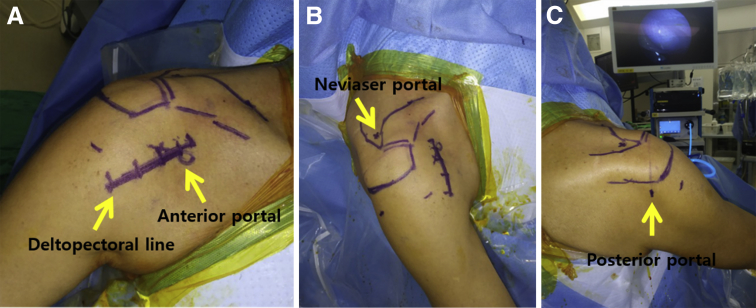

A preoperative peripheral nerve block and general anesthesia are induced. The patient is elevated to 60° in the upper part of the beach chair and both legs are elevated to maintain the position. Routine Betadine skin preparation and usual surgical drape are performed. With a marking pen, the shoulder joint is palpated to mark the anterior, lateral, and posterior border of the clavicle distal end, acromion, acromioclavicular joint, and scapular spine. The deltopectoral line is marked for grafting the Achilles tendon–bone on the biceps groove by using the modified keyhole technique (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Right shoulder and beach chair positioning: using a marking pen, the shoulder joint is palpated to mark the anterior, lateral, and posterior border of the clavicle distal end, acromion, acromioclavicular joint, and scapular spine. In addition, the deltopectoral line is marked along the anterior portal. (A) Anterior aspect. (B) Superior aspect. (C) Posterior aspect.

Portal Placement/Diagnostic Arthroscopy

To form the posterior portal, a blunt trocar is placed 1 cm medial and 1 cm inferior from the posterolateral tip of the acromion and inserted into the glenohumeral joint with the bladder trocar facing the coracoid process between the infraspinatus and teres minor tendons. An anterior spinal needle is placed on a soft-tissue spot in a slightly lateral portion (to suit deltopectoral incision) of the coracoid process to the anterior portal.

If the biceps tendon is still present in the joint (often, there is a chronic tear and the long head is absent), it needs to be removed from the superior glenoid. On completion of arthroscopic SCR, mini-open subpectoral biceps tenodesis can be performed. Any loose bodies should be removed, and synovectomy can be performed as needed.

The scope is then repositioned into the subacromial space. A lateral portal is created, typically one anterolaterally and one posterolaterally. Bursectomy is performed; the rotator cuff tear is then carefully evaluated, characterized, and mobilized, ensuring that repair is not possible or advisable. SCR is considered if there is a massive full-thickness tear of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus that cannot be repaired and the glenohumeral joint does not show severe degenerative changes. Then, the decision is made to proceed with SCR using an Achilles tendon–bone allograft.

Preparation of the Superior Aspect of the Glenoid

Any residual soft tissue on the superior glenoid neck and greater tuberosity is removed using a motorized shaver and/or electrocautery wand. To maximize healing potential, the superior glenoid neck is burred down to the bleeding bone.

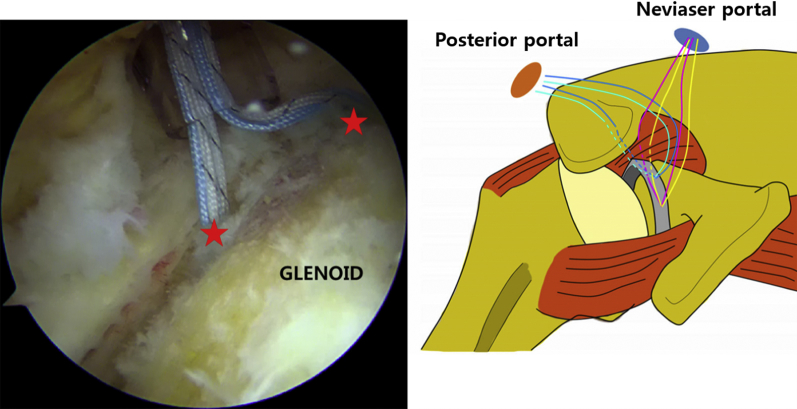

A Neviaser portal is made to fix the medial anchor. Through this, medial anchors are placed on the superior glenoid, approximately 1 mm medial to the rim, taking care to ensure good bone quality and avoid intra-articular penetration. Anchors are placed as far anterior and posterior as possible to provide adequate spread and coverage for medial graft fixation on the glenoid. Typically, 2 anchors (Y-Knot RC All-Suture Anchor w/Two #2 Hi-Fi Sutures; ConMed Linvatec, Largo, FL) are placed in the region between the 10- and 2-o’clock positions (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Glenoid anchors. Right shoulder: A Neviaser portal helps with the proper trajectory of the anchors, which are placed in the region between the 10- and 2-o’clock positions (red stars).

Graft Preparation and Passage

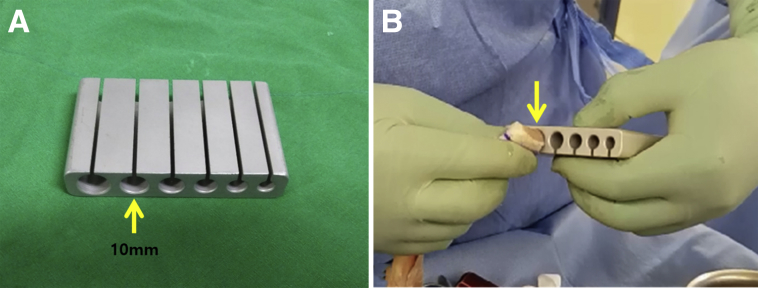

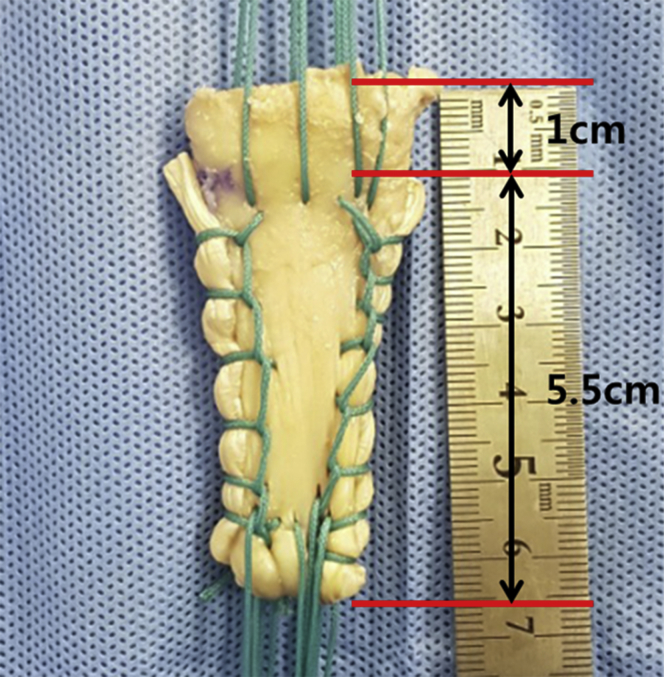

An Achilles tendon–bone allograft is prepared on the back table. After the allograft is thawed, a burr, microsaw, rasp, and rongeur are used to make a 10-mm transverse bone plug from the calcaneus, along with the attached tendon. Next, the Achilles tendon–bone length is customized for each patient according to the humeral head length. After that, tendon–bone diameter is checked to ensure that it is 10 mm through graft sizing block (Fig 3). The average appropriate length for a graft is 5.5 and 5.0 cm for male and female patients, respectively. This is accurately measured through the medial–lateral distance measured for the glenoid and tuberosity anchors. Once the appropriate size is confirmed, the length of the Achilles tendon that is to be folded in 2 layers using multiple no. 2 ETHIBOND (Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) stitches is marked to obtain at least an 8-mm-thick graft through the Krackow suture technique (Fig 4). Then, a no. 2 ETHIBOND stitch is used to make 4 shuttle relay threads on the opposite side of the bone.

Fig 3.

Graft preparation. (A) Graft sizing block. (B) The Achilles tendon–bone is inspected with graft sizing block to make a 10 mm-transverse bone plug (yellow arrow).

Fig 4.

Graft preparation. To insert into the keyhole of the humerus head, the bone should be made to the proper size. It is also important to precisely mark the Achilles tendon in duplicate for the length of the graft to be obtained through the Krackow suture technique.

Graft Insertion and Fixation in the Humeral Head Using the Mini-Open Modified Keyhole Technique

The skin incision is exposed with an additional 5-cm incision through the deltopectoral approach on the anterior portal. The humeral head is exposed using a Kolbel self-retractor. The biceps tendon with previous tenotomy is removed from the biceps groove and tagged using Vicryl sutures for the tenodesis. The tunneling guide pin used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is inserted into the biceps groove 1 cm below the humeral head. A 10-mm reamer is used to create a tunnel for tendon–bone insertion (Fig 5). Then, 2 anchors (Y-Knot RC All-Suture Anchor w/Two #2 Hi-Fi Sutures; ConMed Linvatec) are inserted on the medial side of the keyhole for additional fixation of the tendon–bone graft. The Achilles tendon–bone graft is then inserted into the humeral hole using a bone tamper. After each mattress stitch is tied, lateral row knotless anchors (3.5 mm Pop-Lock; ConMed Linvatec) are inserted 2 to 3 cm distal to the lateral edge of the keyhole (Fig 6).

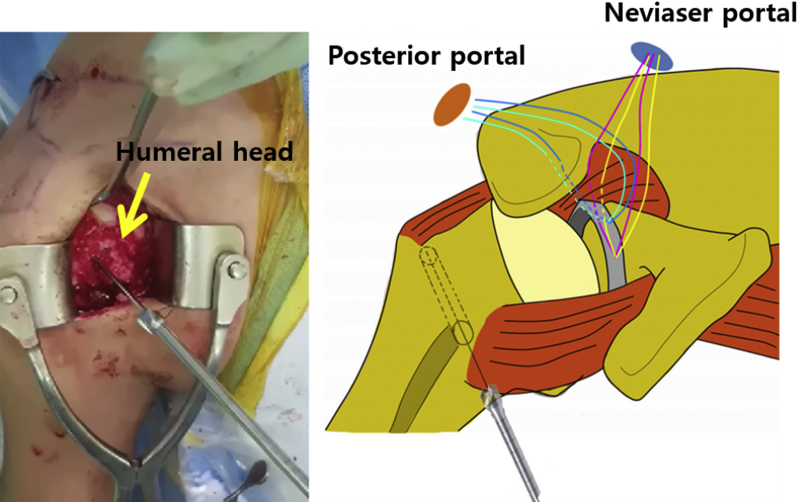

Fig 5.

Right shoulder: the tunneling guide pin is inserted into the biceps groove just 1 cm below the humeral head. A 10-mm reamer is used to create a tunnel for tendon–bone insertion.

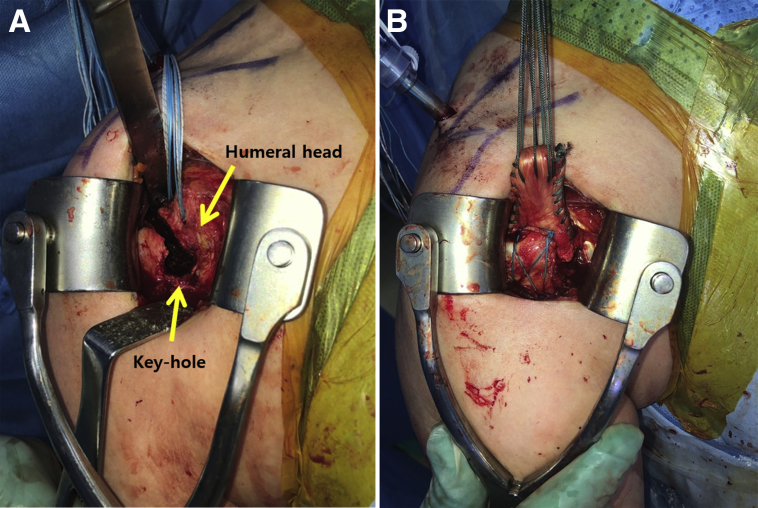

Fig 6.

Graft insertion and fixation (right shoulder). (A) A keyhole is formed in the biceps groove. Two anchors are inserted into the medial row. (B) A prepared Achilles tendon–bone graft is inserted into the humeral head and fixed using a knotless anchor. At this time, if it is fixed to the medial side, the anchor may be inserted into the hole and fracture may occur.

Medial Fixation With Shuttle Relay and Knot Tying

Thereafter, the anchor threads inserted into the glenoid again through the arthroscope are taken individually from the back to the mini-open site and passed through the shuttle relay from the lower to the upper side using ETHIBOND, which was previously sutured on the medial side of the Achilles tendon. The paired anchor thread is then transferred to the posterior portal. The graft tendon is passed in the same format as # 3 and # 4 and left as a Neviaser portal. Then, the Achilles tendon is inserted back into the joint through the mini-open site and tied in the reverse order from #4 to #1 (Fig 7).

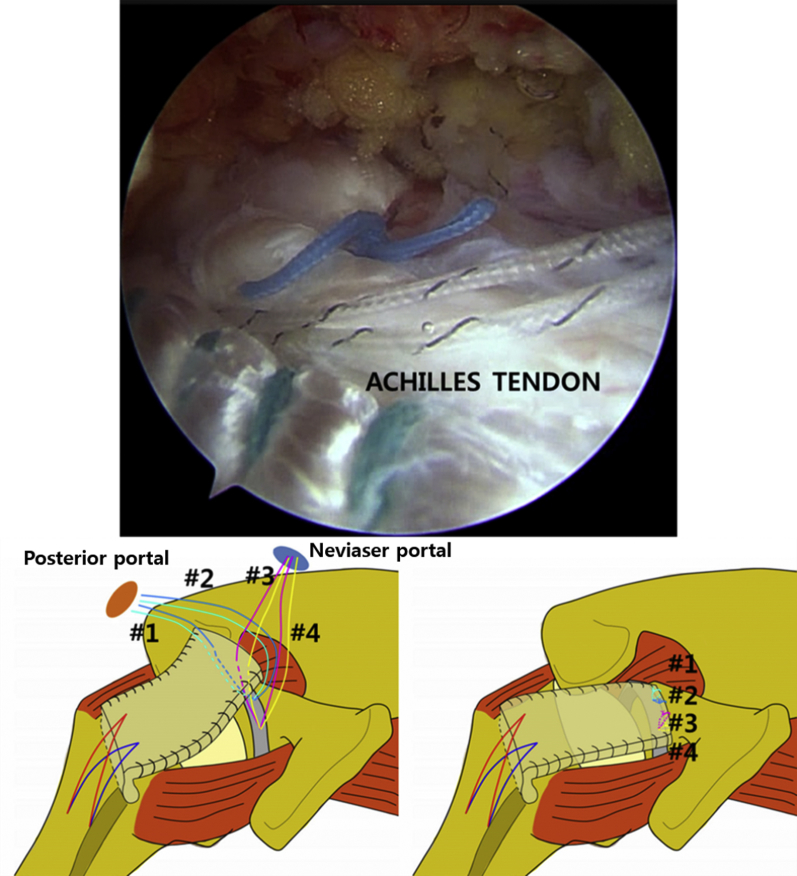

Fig 7.

Right shoulder: the anchors on the glenoid are passed through the shuttle relay from the lower side to the upper side using the ETHIBOND from the back side. The Achilles tendon is inserted back into the joint through the mini-open site. Afterward, the anchors are tied. (#1: green anchor knot, #2: blue anchor knot, #3: red anchor knot and #4: yellow anchor knot.)

Anterior and Posterior Convergence

Once the graft is secured medially and laterally, side-to-side margin convergence sutures are placed to secure the graft to the intact cuff. Typically, 2 side-to-side sutures are used posteriorly to connect the graft to the intact part of the infraspinatus or the teres minor (Fig 8). If necessary, the superior border of the subscapularis and graft tendon may be sutured 1 or 2 in the anterior aspect. The shoulder is then taken through a full range of motion to ensure there are no signs of impingement. Residual spurs on the acromion or osteophytes off the inferior distal clavicle should be resected.

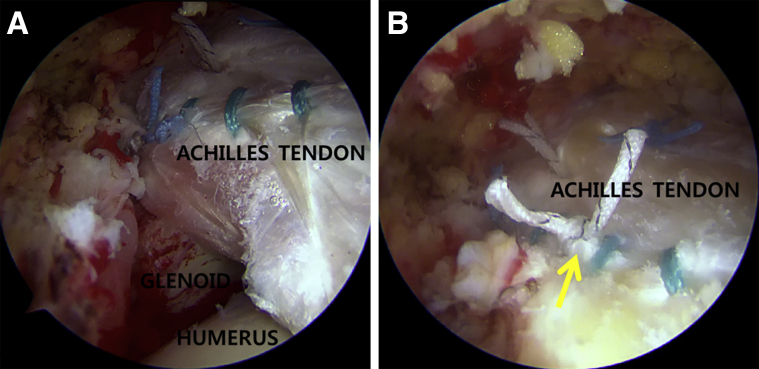

Fig 8.

Anterior and posterior convergence (right shoulder). (A) After the Achilles tendon is fixed on the glenoid side, there is an empty space with the intact cuff on the posterior side. (B) Posterior convergence is performed using an anchor knot (yellow arrow).

Closure and Postoperative Protocol

All portals are closed in a standard manner. Postoperatively, the patient is placed in a sling with an abduction brace. The brace should remain in place for 8 weeks. The patient is only allowed elbow, wrist, and hand exercises for 4 weeks. Progressive motion such as forward elevation begins at 4 weeks postoperatively. Passive range-of-motion exercises begin at 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively and full active motion is allowed after 8 weeks. Strengthening progresses after 12 weeks, and return to activities that require overhead lifting is allowed no earlier than 16 weeks. Typical full return to activities is allowed 6 months postoperatively.

Discussion

We have introduced the SCR technique through grafting with the Achilles tendon–bone. Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in younger and active patients remain a significant clinical challenge to orthopaedic surgeons. Arthroplasty with reverse shoulder replacement is not ideal in these patients. Mihata et al.9 showed in biomechanical cadaveric studies that graft reconstruction can restore superior glenohumeral translation when the graft is attached to the glenoid medially and the humeral head laterally.

An advantage of SCR is that it provides an option to restore and rebalance the force couples necessary for dynamic shoulder function and does not exclude future treatment options. By securing the graft to the glenoid neck, graft integration into the native rotator cuff is not required for function. The graft functions to add superior stability to the glenohumeral joint, thus restoring more anatomic force couples and improving function. The graft also links the posterior and anterior rotator cuff and may function as a soft-tissue spacer and preventive measure against superior migration of the humeral head. With the graft secured to the glenoid and humerus, one could reason that there may be increased medial–lateral tension on the graft from simple adduction of the extremity, resulting in potential failure of the construct. However, many technical aspects of this procedure have not been well studied, such as ideal suture and anchor configuration medially or laterally, ideal graft tissue (allograft vs autograft), ideal graft thickness, or ideal tensioning technique.

When reviewing studies on recurrent tear and graft tear for SCR, Mihata et al.4 reported a recurrent tear and graft tear rate of 16.7% (4/24) in patients treated by SCR using the fascia lata at a mean follow-up of 34 months. In the study by Lim et al.7, failures may have occurred because of excessive tension concentrated on the distal portion of the graft (graft on the greater tuberosity) during active shoulder abduction and elevation. Thus, we devised a hole in the humeral head to insert a tendon–bone graft to increase the fixation tensioning of the graft to the humerus.

We focused on saving operative time and the surface such that bone-to-bone healing is induced by the tendon–bone graft, using a keyhole to reduce graft tear in the greater tuberosity. In a study on anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, healing and revascularization were induced by grafting the Achilles tendon–bone through bone tunneling.10 In this way, we confirmed that the Achilles tendon–bone graft had a good effect in SCR by creating a keyhole-shaped tunnel in the humeral head. An appropriate size and thickness can be achieved with the Achilles tendon through appropriate folding due to a large-sized graft. Although there is a risk of additional fractures due to artificial hole formation, it may be difficult to rehabilitate because bone healing should occur within a particular time frame. However, we followed the same rehabilitation protocol as that used in the general SCR technique.

Overall, the advantages of this technique are as follows: (1) no donor-site morbidity; (2) fixation through bone-to-bone graft improves humeral healing; and (3) it is easy to adjust the size or thickness of the graft using the Achilles allograft. The disadvantages are as follows: (1) it is not the easiest of all arthroscopic techniques; (2) fractures may occur when the hole position is improper; and (3) allografts are expensive (Tables 1 and 2). Considering these, SCR by the mini-open modified keyhole technique can lead to good clinical results if patients with proper indications are selected. The clinical outcomes at our institution are relatively short-term but have shown early promising results. Larger studies with longer-term follow-up are required to completely evaluate the efficacy of this technique.

Table 1.

Technical Pearls and Pitfalls of SCR Using an Achilles Tendon–Bone allograft

|

|

|

|

|

SCR, superior capsular reconstruction.

Table 2.

Advantages and Disadvantages

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: This study was supported by a Wonkwang University research grant 2019. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction by the mini-open modified keyhole technique using an achilles tendon–bone allograft.

References

- 1.Bedi A., Dines J., Warren R., Dines D. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1894–1908. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novi M., Kumar A., Paladini P., Porcellini G., Merolla G. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: Challenges and solutions. Orthop Res Rev. 2018;10:93–103. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S151259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wall K.C., Toth A.P., Garrigues G.E. How to use a graft in irreparable rotator cuff tears: A literature review update of interposition and superior capsule reconstruction techniques. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11:122–130. doi: 10.1007/s12178-018-9466-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mihata T., Lee T.Q., Watanabe C. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fishman J.A., Greenwald M.A., Grossi P.A. Transmission of infection with human allografts: Essential considerations in donor screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:720–727. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingulli E. Mechanism of cellular rejection in transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim S., AlRamadhan H., Kwak J.M., Hong H., Jeon I.H. Graft tears after arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction (ASCR): Pattern of failure and its correlation with clinical outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139:231–239. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-3025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo J.C., Ahn J.H., Yang J.H., Koh K.H., Choi S.H., Yoon Y.C. Correlation of arthroscopic repairability of large to massive rotator cuff tears with preoperative magnetic resonance imaging scans. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mihata T., McGarry M.H., Pirolo J.M., Kinoshita M., Lee T.Q. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: A biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2248–2255. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shino K., Kawasaki T., Hirose H., Gotoh I., Inoue M., Ono K. Replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament by an allogenic tendon graft: An experimental study in the dog. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66:672–681. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6501359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction by the mini-open modified keyhole technique using an achilles tendon–bone allograft.