Abstract

Lavandula pubescens Decne (LP) is one of the three Lavandula species growing wildly in the Dead Sea Valley, Palestine. The products derived from the plant, including the essential oil (EO), have been used in Traditional Arabic Palestinian Herbal Medicine (TAPHM) for centuries as therapeutic agents. The EO is traditionally believed to have sedative, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, antidepressive, antiamnesia, and antiobesity properties. This study was therefore aimed to assess the in vitro bioactivities associated with the LP EO. The EO was separated by hydrodistillation from the aerial parts of LP plants and analyzed for its antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticholinesterase, and antilipase activities. GC-MS was used for phytochemical analysis. The chemical analysis of the EO composition revealed 25 constituents, of which carvacrol (65.27%) was the most abundant. EO exhibited strong antioxidant (IC50 0.16–0.18 μL/mL), antiacetylcholinesterase (IC50 0.9 μL/mL), antibutyrylcholinesterase (IC50 6.82 μL/mL), and antilipase (IC50 1.08 μL/mL) effects. The EO also demonstrated high antibacterial activity with the highest susceptibility observed for Staphylococcus aureus with 95.7% inhibition. The EO was shown to exhibit strong inhibitory activity against Candida albicans (MIC 0.47 μL/mL). The EO was also shown to possess strong antidermatophyte activity against Microsporum canis, Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum (EC50 0.05–0.06 μL/mL). The high antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, and antimicrobial potentials of the EO can, therefore, be correlated with its high content of monoterpenes, especially carvacrol, as shown by its comparable bioactivities indicators results. This study provided new insights into the composition and bioactivities of LP EO. Our finding revealed evidence that LP EO makes a valuable natural source of bioactive molecules showing substantial potential as antioxidant, neuroprotective, antihyperlipidemic, and antimicrobial agents. This study demonstrates, for the first time, that LP EO might be useful for further investigation aiming at integrative CAM and clinical applications in the management of dermatophytosis, Alzheimer's disease, and obesity.

1. Introduction

The genus Lavandula (Lamiaceae), lavender, is a typical aromatic evergreen understory chamaephyte that comprises about 32 species [1], some of them being utilized in complementary and alternative medicine for a long time, either dried or as essential oils (EOs). Three native Lavandula species are growing wild in Palestine (West Bank and Gaza Strip), namely, L. pubescens Decne (Downy lavender), L. stoechas L. (French lavender), and L. coronopifolia Poir. (Staghorn lavender) [2]. L. pubescens is common in the Dead Sea Valley, Jerusalem, and Hebron Desert and very rare in the Lower Jordan Valley and L. coronopifolia is common only in the Dead Sea Valley and only rare in Jerusalem and Hebron Desert, whereas L. stoechas is rare in Gaza Strip. Many pharmacological properties have been reported for lavender EOs, including local anesthetic, sedative, analgesic, anticonvulsant, antispasmodic [3, 4], cholinesterase inhibitory [5], antioxidant [6, 7], antibacterial, and antifungal effects and inhibition of microbial resistance [6, 8], and they are used for the treatment of inflammation and many neurological disturbances [9]. The oil has also been utilized for relieving anxiety and associated sleep disorders [10], depression, and headache [11]. The EO of Lavandula species is also used widely in pharmaceutical fragrance, food, and household cleaners [12–14].

The EO of L. pubescens has been reported to exhibit a strong wide-ranging in vitro antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria including Salmonella enterica, Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus luteus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Escherichia coli [6, 13, 15] and hepatoprotective [16], cytotoxic, and xanthine-oxidase inhibitory activities [6, 8].

The products derived from the Palestinian Downy lavender (L. pubescens) (Arabic, Khuzama), including EO, have been utilized for centuries in Traditional Arabic Palestinian Herbal Medicine (TAPHM) as CAM therapies [17]. The LP EO is traditionally believed to have sedative, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, antidementia, and antiobesity properties and has therefore been utilized for the management of, but not limited to, indigestion, neurological disorders, dementia, obesity, and microbial skin infections [17].

However, no reports are available on the antidermatophytic, anticholinesterase (i.e., anti-Alzheimer's disease), and antilipase (i.e., antiobesity) effects associated with the EO of L. pubescens.

This study was, therefore, aimed at defining the chemical composition of EO attained from above-ground parts of L. pubescens plants collected from wild populations in the Dead Sea Valley in Palestine, and assessing its potential in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticholinesterase, and antilipase effects and thus to verify its use as a complementary medicine for the treatment of AD, obesity, and microbial skin infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Essential Oil Extraction

The aerial parts of fully bloomed Lavandula pubescens were collected from Palestine (Dead Sea Valley) in May 2017 and used for EO extraction. Plants were authenticated by the first author. The voucher specimen (Lavandula pubescens Decne, Voucher No. BERC-BX603) has been deposited at BERC Herbarium, Til, Nablus, Palestine. 250 gm of the fresh above-ground plant parts were subjected to hydrodistillation using a modified Clevenger apparatus until there was no significant increase in the amount of EO collected [18].

2.2. GC-MS Analysis of Essential Oil

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was performed to determine the EO composition by using the conditions reported by Ali-Shtayeh et al. [18]. Identification of the compounds was performed by comparing their relative retention indices (RI) with those of authentic compounds (e.g., carvacrol, terpinolene, ε-caryophyllene, and β-bisabolene) or by comparing their mass spectral fragmentation patterns with Wiley 7 MS library (Wiley, New York, NY, USA) and NIST98 (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) mass spectral database. The identified components along with their RI values and percentage composition are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the essential oil of Lavandula pubescens.

| Nu. | Ret time | RI | Compound name | Area % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.93 | 988 | Myrcene | 2.05 |

| 2 | 7.383 | 1002 | α-Phellandrene | 0.14 |

| 3 | 7.456 | 1008 | 3-δ-Carene | 0.20 |

| 4 | 7.681 | 1014 | α-Terpinene | 0.15 |

| 5 | 7.89 | 1022 | p-Cymene | 0.20 |

| 6 | 8.03 | 1029 | Limonene | 0.12 |

| 7 | 8.104 | 1026 | 1,8-Cineole | 0.05 |

| 8 | 8.225 | 1032 | Ζ-β-Ocimene | 2.63 |

| 9 | 8.519 | 1044 | Ε-β-Ocimene | 0.20 |

| 10 | 9.667 | 1086 | Terpinolene | 5.34 |

| 11 | 9.781 | 1089 | p-Cymenene | 0.10 |

| 12 | 10.068 | 1054 | α-Terpinolene | 0.04 |

| 13 | 10.439 | 1108 | 1,3,8-p-Menthatriene | 0.03 |

| 14 | 12.631 | 1179 | p-Cymen-8-ol | 0.53 |

| 15 | 12.874 | 1186 | 4-Terpineol | 0.21 |

| 16 | 13.029 | 1201 | 4,5-Epoxy-1-isopropyl-4-methyl-1-cyclohexene | 0.36 |

| 17 | 13.308 | 1215 | 2,6-Dimethyl-3,5,7-octatriene-2-ol | 0.08 |

| 18 | 14.158 | 1241 | Carvacrol methyl ether | 5.36 |

| 19 | 15.695 | 1286 | Thymol | 0.26 |

| 20 | 16.071 | 1298 | Carvacrol | 65.27 |

| 21 | 16.082 | 1294 | Para-menth-1-en-9-ol | 1.73 |

| 22 | 19.241 | 1417 | ε-Caryophyllene | 6.21 |

| 23 | 20.172 | 1452 | α-Humulene | 0.20 |

| 24 | 21.544 | 1505 | Β-Bisabolene | 7.43 |

| 25 | 23.387 | 1582 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1.11 |

2.3. Antioxidant Activity Evaluation

Antioxidant properties of the EO from L. pubescens were evaluated by using the following methods: the 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzo thiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) ABTS radical cation decolorization and reductive potential (RP) assays as reported previously [19, 20]. Trolox, ascorbic acid, and BHT were used as standard antioxidants.

2.4. Enzymatic Inhibitory Activities

The essential oils of L. pubescens and carvacrol were investigated for their enzyme inhibitory properties on acetylcholinesterase (AChE), butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), and porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL) following previously reported spectrophotometric methods [21, 22]. Neostigmine was used as a reference compound for AChE and BuChE enzymes, and orlistat was used for PPL enzyme.

The effects of different doses of test compounds (LP essential oil, carvacrol and reference compounds) on the AChE, BuChE, and PPL activities were used to calculate the IC50 values from dose-effect curves by linear regression.

2.5. Microbiological Assays

Microorganisms used in this study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Test microorganisms.

| Microorganisms | Species name | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC 25923 | Gram positive |

| Proteus vulgaris | ATCC 13315 | Gram negative | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | ATCC 27853 | ||

| Salmonella typhi | ATCC 14028 | ||

| Escherichia coli | ATCC 25922 | ||

| Klebsiella pneumonia | ATCC 13883 | ||

|

| |||

| Candida | Candida albicans | CBS6589 | |

| CBS9120 | |||

| BERC M77 | Clinical isolates (vulvovaginal and cutaneous candidiasis patients) | ||

| BERC N17 | |||

| BERC N40 | |||

|

| |||

| Dermatophytes | Microsporum canis | CBS 132.88 | |

| BERC MC03 | Clinical isolates (dermatophytosis patients) | ||

| BERC MC39 | |||

| BERC MC13 | |||

| Trichophyton rubrum | BERC CBS 392.58 | ||

| BERC TR64 | Clinical isolates (dermatophytosis patients) | ||

| BERC TR67 | |||

| BERC TR69 | |||

| Trichophyton mentagrophytes | CBS 106.67 | ||

| BERC TM1 | Clinical isolates (dermatophytosis patients) | ||

| BERC TM2 | |||

| BERC TM78 | |||

| Epidermophyton floccosum | CBS 358.93 | ||

2.5.1. Agar Disc Diffusion Assay

This method was used to evaluate the antimicrobial activities of the EO and carvacrol against Candida albicans and bacterial strains as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [23]. The inhibition zone diameter for each sample was measured in mm and used to calculate the antibacterial and anticandidal activity index (AI) and % of inhibition (PI) at a concentration of 1 μL/disc using the following formulas [24]:

| (1) |

All experiments were done in triplicate. Chloramphenicol and voriconazole were used as positive controls for bacteria and candida, respectively.

2.5.2. Broth Microdilution Assay

The broth microdilution technique with some modifications was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the EO against bacteria and C. albicans strains [25–27]. Chloramphenicol (1 to 64 μg/mL) and voriconazole (0.019 to 1.25 μg/mL) were used as reference antibiotics for bacteria and Candida, respectively.

2.5.3. Determination of Antidermatophytic Activity: Poisoned-Food Technique

Essential oils from L. pubescens and carvacrol were tested for their antidermatophyte activity against four dermatophytes species: Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Epidermophyton floccosum, and Trichophyton rubrum (Table 2) using the modified poisoned-food technique [28]. EO and carvacrol were tested at different concentrations (0.5–0.0039 mL/L). Mycelial growth inhibition % (PI) was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where DC is the average diameter of mycelial growth of the control, and DT is the average diameter of mycelial growth of the treatment. Effective concentration fifty (EC50) that caused 50% growth inhibition was estimated using Microsoft Excel 2010 under Windows 10.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) were assessed following the previously reported assays [29, 30].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GC-MS Analysis

There are no reports on the EO composition of L. pubescens growing wild in Palestine and only a few such reports are available worldwide [6, 8, 13, 31]. Hydrodistillation of the L. pubescens leaves yielded 1.9 mL per 250 g fresh plant material.

The GC-MS analysis of the EO led to the identification of 25 components (Table 1). The main identified compounds were carvacrol (65.27%), β-bisabolene (7.43%), ε-caryophyllene (6.21%), carvacrol methyl ether (5.36%), terpinolene (5.34%), Z-β-ocimene (2.63%), myrcene (2.05%), para-menth-1-en-9-ol (1.73%), and caryophyllene oxide (1.11%), representing 97.13% of the total oil. Hence, the EO from the Palestinian L. pubescens can be characterized as carvacrol chemotype. The oxygenated monoterpenes were the dominant (73.26%) chemical group within the constituents, followed by sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (13.84%), monoterpene hydrocarbons (11.79%), and oxygenated sesquiterpenes (1.11%). The EO chemical profile in this study is qualitatively comparable to that formerly reported from Yemen where the EO has shown to be carvacrol chemotype (60.9–77.5%) [6, 31].

Carvacrol is a monoterpenic phenol that is biosynthesized from γ-terpinene [32] through p-cymene [33]. These two compounds are therefore present in the L. pubescens EO. Biosynthetic intermediates such as terpinene-4-ol [34] and p-cymen-8-ol [35] are also present [36].

3.2. Antioxidant Potential

The antioxidant activity of EOs is a biological property of great interest because the oils that possess the ability of scavenging free radicals may play an important role in the prevention of some diseases that may result from oxidative stress damages caused by the free radicals, such as brain dysfunction, Alzheimer's disease, obesity, cancer, heart disease, and immune system decline [37–39]. The consumption of naturally occurring antioxidants that can be used to protect human beings from oxidative stress damages has therefore been increased [38]. This work reports the antioxidant activities of L. pubescens EO as assessed by ABTS and RP assays (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antioxidant activities of essential oil from aerial parts of Lavandula pubescens.

| ABTS | Reductive potential | |

|---|---|---|

| IC 50 (μL/mL) | ||

| Oil | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.0 |

| Carvacrol | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.0 |

|

| ||

| Standard antioxidants IC 50 (mg/ml) | ||

| Trolox | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.08 ± 0.0 |

| Ascorbic acid | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.04 ± 0.0 |

| BHT | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

The antioxidant potential of LP EO was generally high with RP50 and IC50 of 0.16 and 0.18 μL/mL using RP and ABTS assays, respectively. Interestingly, carvacrol has shown comparable antioxidant activity (IC50 = 0.03 μL/mL) relative to the potent antioxidant agent BHT using the ABTS assay and high antioxidant capacity (RP50 = 0.07 μL/mL) comparable to the tested potent antioxidant agents (Trolox and BHT) (Table 3).

The antioxidant capacities of L. pubescens EO may be attributed to the high content of the oil's major phenolic constituents, especially carvacrol, which were confirmed as effective antioxidant compounds with potential health benefits [40]. Our results demonstrate that the EOs of L. pubescens and carvacrol have a significant strength to provide electrons to reactive oxygen species (ROS), converting them into more stable nonreactive species and ending the free ROS chain reaction.

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

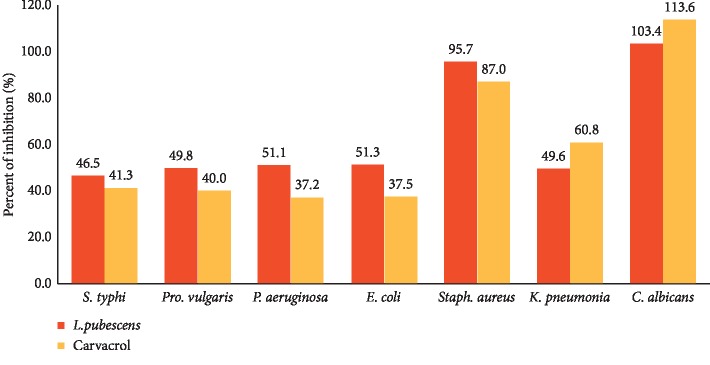

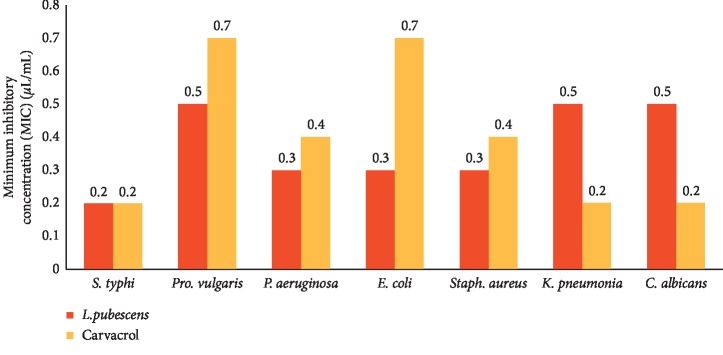

Results for the in vitro antibacterial activity of L. pubescens EO and carvacrol are presented in Figures 1 and 2 as PI and MIC. The EO and carvacrol had similar high antibacterial activities against all bacteria tested with a PI range of 37.2–95.7% and MIC range of 0.2–0.7 μL/mL. Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) was the most susceptible strain (PI value 95.7% for EO and 87% for carvacrol). Among the tested Gram-negative bacterial strains, the EO has comparable inhibition effect with PI values 46.5, 49.8, 51.1, 51.3, and 49.6% against Salmonella typhi, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, E. coli, and K. pneumonia, respectively.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial activity (percent of inhibition) of essential oil and carvacrol on bacteria and Candida albicans.

Figure 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the essential oil against bacteria strains and Candida albicans.

The strong antibacterial activity of the EO may be ascribed to the presence of high % of oxygenated monoterpenes (73.26%) such as carvacrol (65.27%), which was found to destroy cell morphology and biofilm viability in typical biofilm construction by increasing the permeability and reducing polarization of the cytoplasmic membrane [41–43]. The antibacterial activity of carvacrol has been mainly attributed to its hydrophobicity and the free hydroxyl group in its structure [44]. With the appropriate hydrophobicity of carvacrol, the compound can be accumulated in the cell membrane, while its hydrogen-bonding and its proton-release abilities may induce conformational modification of the membrane resulting in cell death [45]. Our results can, therefore, explain the association of the use of the LP EO in TAPHM as an antiseptic, due to the antibacterial action of carvacrol which has been previously confirmed [46, 47].

3.4. Anticandidal Activity

Candidiasis is a mycotic infection caused by several species of Candida, which can endorse superficial and systemic opportunist diseases worldwide. The current treatment against candidiasis is based on synthetic antimycotic drugs. Most presently available anticandidal drugs have limitations that hamper their use, which necessitates the search for safe and effective antimycotic agents.

The results of this study showed that the EO and carvacrol possessed strong inhibitory activity against C. albicans (isolated from cutaneous and vulvovaginal infections) with average PI values of 103.4% for EO and 113.6% for carvacrol (Figure 1) and MIC values of 0.47 and 0.24 μL/mL for EO and carvacrol, respectively (Figure 2). The strong anticandidal activity of EO can, therefore, be correlated with its high content of carvacrol owing to the anticandidal activity of carvacrol which has been previously confirmed [48].

3.5. Antidermatophytic Activity

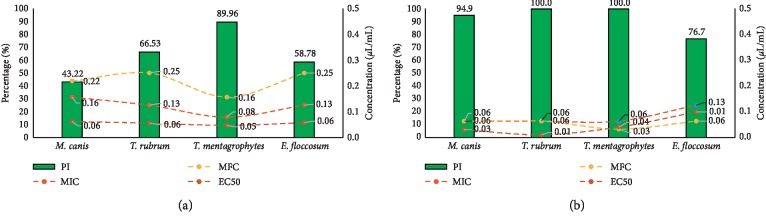

Aromatic plants EOs are known to be mycostatic or fungicidal and represent a potential source of new antimycotics [49]. In view of the increasing resistance to the classical antimycotics, the EOs and their active constituents may be beneficial in the management of mycoses, especially dermatophytosis [50]. In the present study, the L. pubescens EO showed strong activity against M. canis, T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, and E. floccosum as indicated by their PI, MIC, MFC, and EC50 values (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of mycelial growth inhibition (PI) with MIC, MFC, and EC50 values of (a) of Lavandula pubescens EO and (b) carvacrol against the tested dermatophytes.

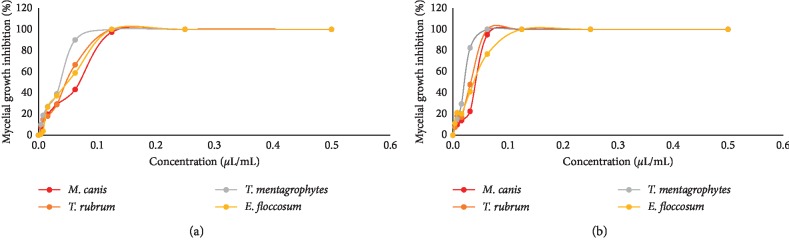

The EO of L. pubescens and carvacrol showed a dose-dependent activity against the tested dermatophytes (Figure 4). Overall, as the dose of the EO or carvacrol increased, the inhibitory activity against the tested dermatophytes increased indicated by heightened mycelial growth inhibition. The radial mycelial growth of all tested isolates was completely inhibited by the EO and carvacrol at 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 μL/mL concentration. However, at lower doses (0.004–0.063 μL/mL), the EO was still more active on the mycelial growth of T. mentagrophytes than other tested dermatophytes at 0.63 μL/mL, PI = 89.7% (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Mycelial growth inhibition activity of (a) Lavandula pubescens essential oil and (b) carvacrol against the tested dermatophytes.

The MIC and EC50 values of the EO of L. pubescens on the tested dermatophytes were in the ranges of 0.08–0.16 μL/mL and 0.05–0.06 μL/mL, respectively. However, EO showed a fungicidal effect on the four studied dermatophytes and the MFCs were in the range of 0.16–0.25 μL/mL. T. mentagrophytes were more susceptible to L. pubescens EO than the other tested fungi with MIC, MFC, and EC50 values of 0.05, 0.08, and 0.16 μL/mL, respectively.

The strong antifungal property could be attributed to the major component of the EOs, carvacrol, and the oxygenated monoterpene, which exhibited strong inhibitory activity against the tested dermatophytes (Figure 3) with PI, MIC, EC50, and MFC values ranging from 76.7 to 100%, 0.063–0.125 μL/mL, 0.01–0.1 μL/mL, and 0.03–0.63 μL/mL, respectively. The monoterpene alcohols are water soluble and possess functional alcohol groups that explain their strong antidermatophyte activity [49].

In general, EO and carvacrol can exert their antidermatophyte actions due to membrane damage, cytoplasmic content leakage, and ergosterol depletion [49, 51–53].

3.6. Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Essential Oil

3.6.1. Anticholinesterase Activity

Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) have recently become the most widely used drugs for the management of Alzheimer's disease (AD) [54]. ChEIs play a crucial role in the memory enhancement of AD patients through increasing ACh concentration in neural synaptic clefts and thus improving the brain cholinergic transmission and decreasing β-amyloid aggregation and neurotoxic fibrils formation [55–57]. However, synthetic AChEIs including galanthamine and tacrine have restrictions owing to the short half-life and adverse side effects such as digestive disorders, nausea, and dizziness [58, 59]. Hence, it is necessary to explore new safe alternatives with superior characteristics to deal with AD.

Several plants and phytochemical compounds have revealed cholinesterase inhibitory capacity and therefore can be valuable in the management of neurological disturbances [21]. In this study, LP EO was investigated for its in vitro cholinesterases (AChE and BuChE) inhibitory activities. The EO and carvacrol have shown to possess high AChE (IC50 = 0.9, and 1.43 μL/mL, respectively) and medium BuChE (IC50 6.82, and 7.75 μL/mL, respectively) inhibitory activities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Cholinesterase inhibitory activity (ChEIA) of L. pubescens essential oil.

| IC50 (μL/mL) | Selectivity index (SI)∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinestrase | Buterylcholinestrase | ||

| Oil | 0.9 ± 0.14 | 6.82 ± 0.35 | 7.58 ± 0.13 |

| Carvacrol | 1.43 ± 0.56 | 7.75 ± 0.25 | 5.42 ± 0. 01 |

| Neostagmin (μg/mL) | 1.54 ± 0.00 | 174.41 ± 0.00 | 113.18 ± 0.00 |

∗SI = IC50 BuChE/IC50 AChE.

Thus, the high AChE inhibitory effect of the L. pubescens EO in the current study may be mainly associated with its major component, carvacrol, and with its high phenol content. Overall, the tested EO was shown to be more selective inhibitors for acetylcholinesterase than butyrylcholinesterase with a selectivity index (SI) of 7.58.

Our results demonstrate that LP EO could be a valued natural source of AChEIs, e.g., carvacrol, with effective inhibitory activities against the principal enzymes associated with AD and could signify a basis for developing a new treatment strategy for Alzheimer's using plant-derived AChEIs.

3.6.2. Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activity

Pancreatic lipase, the principal enzyme associated with obesity, plays a key role in the efficient digestion of acylglycerols [60]. The hydrolysis of glycerides to glycerol and free fatty acids is performed by lipases. Taking into consideration that 50–70% of the total dietary fat hydrolysis is performed by pancreatic lipase, enzyme inhibition is one of the approaches used to treat obesity [60]. The mechanism involves inhibition of dietary triglyceride absorption, as this is the main source of excess calories [61]. Besides, pancreatic lipase inhibition does not alter any central mechanism, which makes it an ideal approach for obesity treatment [62]. The pancreatic lipase has been widely used for the determination of the potential efficacy of natural products as antiobesity agents [62].

In the present study, L. pubescens EO and carvacrol were assessed for their activity against pancreatic lipase. The EO exhibited high inhibitory activity against PPL with IC50 of 1.08 μL/mL (Table 5). The high antiobesity activity of L. pubescens EO may be mainly ascribed to its high content of carvacrol which has been reported to inhibit visceral adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation in animal cells and decrease body weight and plasma lipid levels [63, 64]. However, carvacrol on its own cannot explain the high activity of EO, and therefore the totality of constituents of the EO may act synergistically to exert such high antiobesity activity. The higher pancreatic lipase inhibitory effects of L. pubescens EO may, therefore, be attributed to its high content of bioactive phenolic acids and flavonoids acting together in a synergistic style [22].

Table 5.

Antiobesity activities of Lavandula pubescens essential oil.

| IC50 (μL/mL) | |

|---|---|

| Oil | 1.08 ± 0.35 |

| Carvacrol | 6.63 ± 1.03 |

| Orlistat (μg/ml) | 0. 12 ± 0.03 |

The current study has indicated the ability of the EO to exercise health benefit attributes by inhibiting the pancreatic lipase enzyme (responsible for digestion and absorption of triglycerides) and thus lead to the reduction of fat absorption.

4. Conclusions

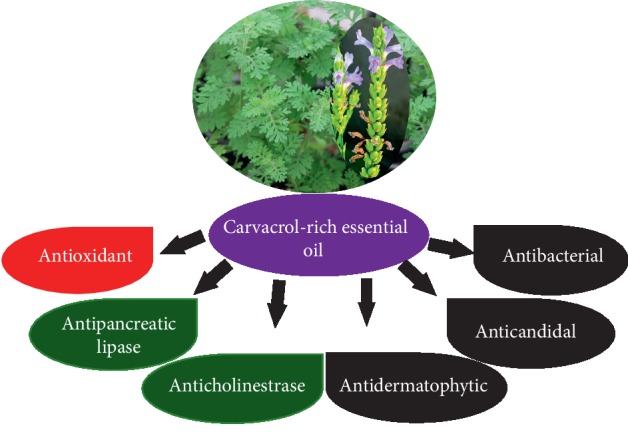

The main constituent of L. pubescens EO was determined as carvacrol in wild plants. The results demonstrate that the plant is a valuable natural source for carvacrol-rich EO with promising potential antimicrobial, antiobesity, and anti-AD health effects (Figure 5). Our results support the use of L. pubescens EO as a natural complementary treatment in TAPHM. This is the first report on the antidermatophytic, AChE inhibitory, and antiobesity effects of L. pubescens EO. In conclusion, our results might be useful for further investigation aiming at clinical applications of L. pubescens EO and carvacrol in the management of AD, obesity, and microbial skin infections including dermatophytosis, candidiasis, and others.

Figure 5.

Beneficial health effects of Lavandula pubecsens essential oil and its main active constituent, carvacrol.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially funded by the Middle East Regional Cooperation (MERC) project M36-010 (award number: SIS700 15G360 10).

Abbreviations

- ABTS:

2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzo thiazoline-6-sulphonic acid)

- AChE:

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD:

Alzheimer's disease

- AI:

Activity index

- BERC:

Biodiversity and environmental research center

- BuChE:

Butyrylcholinesterase

- CLSI:

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- EC50:

Effective concentration fifty

- EO:

Essential oil

- GC-MS:

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- IC50:

Inhibitory concentration fifty

- MFC:

Minimum fungicidal concentration

- MIC:

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- PI:

Percent of inhibition

- PPL:

Porcine pancreatic lipase

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- RP:

Reductive potential

- TAPHM:

Traditional Arabic Palestinian herbal medicine.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lis-Balchin M. Lavender: The Genus Lavandula. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M. Updating the plant “red list” of Palestine (West Bank and Gaza Strip): conservation assessment and recommendations. Journal of Biodiversity & Endangered. 2018;6(3) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehrner J., Marwinski G., Lehr S., Johren P., Deecke L. Ambient odors of orange and lavender reduce anxiety and improve mood in a dental office. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;86(1-2):92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin P. W.-K., Chan W.-C., Ng B. F.-L., Lam L. C.-W. Efficacy of aromatherapy (Lavandula angustifolia) as an intervention for agitated behaviours in Chinese older persons with dementia: a cross-over randomized trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):405–410. doi: 10.1002/gps.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adsersen A., Gauguin B., Gudiksen L., Jäger A. K. Screening of plants used in Danish folk medicine to treat memory dysfunction for acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;104(3):418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Badani R. N., da Silva J. K. R., Mansi I., Muharam B. A., Setzer W. N., Awadh Ali N. A. Chemical composition and biological activity of Lavandula pubescens essential oil from Yemen. Journal of Essential Oil Bearing Plants. 2017;20(2):509–515. doi: 10.1080/0972060x.2017.1322538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baptista R., Madureira A. M., Jorge R., et al. Antioxidant and antimycotic activities of two native Lavandula species from Portugal. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:10. doi: 10.1155/2015/570521.570521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gouda B., Mousa O., Salama M., Kassem H. Volatiles and lipoidal composition: antimicrobial activity of flowering aerial parts of Lavandula pubescens Decne. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research. 2017;9(8) doi: 10.25258/phyto.v9i08.9628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koulivand P. H., Khaleghi Ghadiri M., Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:10. doi: 10.1155/2013/681304.681304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasper S., Gastpar M., Müller W. E., et al. Silexan, an orally administered Lavandula oil preparation, is effective in the treatment of “subsyndromal” anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;25(5):277–287. doi: 10.1097/yic.0b013e32833b3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajhashemi V., Ghannadi A., Sharif B. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of the leaf extracts and essential oil of Lavandula angustifolia mill. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;89(1):67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(03)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim N.-S., Lee D.-S. Comparison of different extraction methods for the analysis of fragrances from Lavandula species by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2002;982(1):31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park C. H., Park Y. E., Yeo H. J., et al. Chemical compositions of the volatile oils and antibacterial screening of solvent extract from downy lavender. Foods. 2019;8(4):p. 132. doi: 10.3390/foods8040132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarker L. S., Galata M., Demissie Z. A., Mahmoud S. S. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of borneol dehydrogenase from the glandular trichomes of Lavandula x intermedia. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2012;528(2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada D., Segni L., Goudjil M. B., Benchiekh S.-E., Gherraf N. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Lavandula pubescens Decne essential oil from algeria. International Journal of Biosciences (IJB) 2018;12(1):187–192. doi: 10.12692/ijb/12.1.187-192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mousa O., Gouda B., Salama M., Kassem H., El-Eraky W. Total phenolic, total flavonoid content, two isolates and bioactivity of Lavandula pubescens Decne. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research. 2018;10(6):254–263. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M. Traditional Arabic Palestinian Herbal Medicine, TAPHM. Til, Nablus, Palestinian: Biodiversity and Environmental Research Center BERC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M., Abu-Zaitoun S. Y., et al. Chemical profile and bioactive properties of the essential oil isolated from Clinopodium serpyllifolium (m.bieb.) kuntze growing in Palestine. Industrial Crops and Products. 2018;124:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira I. C. F. R., Baptista P., Vilas-Boas M., Barros L. Free-radical scavenging capacity and reducing power of wild edible mushrooms from northeast Portugal: individual cap and stipe activity. Food Chemistry. 2007;100(4):1511–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.11.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Re R., Pellegrini N., Proteggente A., Pannala A., Yang M., Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1999;26(9-10):1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali-shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M., Abu Zaitoun S. Y., Qasem I. B. In-vitro screening of acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of extracts from Palestinian indigenous flora in relation to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Functional Foods in Health and Disease. 2014;4(9):381–400. doi: 10.31989/ffhd.v4i9.149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamous R. M., Abu-Zaitoun S. Y., Akkawi R. J., Ali-Shtayeh M. S. Antiobesity and antioxidant potentials of selected palestinian medicinal plants. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;2018:p. 21. doi: 10.1155/2018/8426752.8426752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibumeh J., Egharevba H. O., Iliya I., et al. Broad spectrum antimicrobial activity of Psidium guajava linn. leaf. Nature and Science. 2010;8(12):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarikurkcu C., Zengin G., Oskay M., Uysal S., Ceylan R., Aktumsek A. Composition, antioxidant, antimicrobial and enzyme inhibition activities of two Origanum vulgare subspecies (subsp. vulgare and subsp. hirtum) essential oils. Industrial Crops and Products. 2015;70:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.03.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M., Abu-Zaitoun S. Y., et al. Secondary treated effluent irrigation did not impact chemical composition, and enzyme inhibition activities of essential oils from Origanum syriacum var. syriacum. Industrial Crops and Products. 2018;111:775–786. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.11.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohareb A. S. O., Badawy M. E. I., Abdelgaleil S. A. M. Antifungal activity of essential oils isolated from Egyptian plants against wood decay fungi. Journal of Wood Science. 2013;59(6):499–505. doi: 10.1007/s10086-013-1361-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Euloge S. A., Sandrine K., Edwige D.-A., Dominique C. K. S., Mohamed M. S. Antifungal activity of Ocimum canum essential oil against toxinogenic fungi isolated from peanut seeds in post-harvest in Benin. International Research Journal of Biological Sciences. 2012;1(7):20–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gakuubi M. M., Maina A. W., Wagacha J. M. Antifungal activity of essential oil of Eucalyptus camaldulensis dehnh. against selected Fusarium spp. International Journal of Microbiology. 2017;2017:7. doi: 10.1155/2017/8761610.8761610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Badani R. N., Da Silva J. K. R., Setzer W. N., et al. Variations in essential oil compositions of Lavandula pubescens (lamiaceae) aerial parts growing wild in Yemen. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 2017;14(3) doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201600286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis P., Mill R., Tan K. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands. Vol. 10. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guner A., Ozhatay N., Ekim T., Baser K. Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands. Vol. 11. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirimer N., Başer K. H. C., Tümen G. Carvacrol-rich plants in Turkey. Chemistry of Natural Compounds. 1995;31(1):37–41. doi: 10.1007/bf01167568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baser K. H. C., Kirimer N., Tümen G. Composition of the essential oil of Origanum majorana L. from Turkey. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 1993;5(5):577–579. doi: 10.1080/10412905.1993.9698283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baser K., Başer C., Demirci F. Chemistry of essential oils. In: Berger R., editor. Flavours and Fragrances: Chemistry, Bioprospecting and Sustainability. Heidelberg, Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media; 2007. pp. 43–86. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mata A. T., Proença C., Ferreira A. R., Serralheiro M. L. M., Nogueira J. M. F., Araújo M. E. M. Antioxidant and antiacetylcholinesterase activities of five plants used as Portuguese food spices. Food Chemistry. 2007;103(3):778–786. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scalbert A., Manach C., Morand C., Rémésy C., Jiménez L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2005;45(4):287–306. doi: 10.1080/1040869059096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miguel M. G. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oils: a short review. Molecules. 2010;15(12):9252–9287. doi: 10.3390/molecules15129252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guimarães A. G., Oliveira G. F., Melo M. S., et al. Bioassay-guided evaluation of antioxidant and antinociceptive activities of carvacrol. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2010;107(6):949–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nostro A., Papalia T. Antimicrobial activity of carvacrol: current progress and future prospectives. Recent Patents on Anti-infective Drug Discovery. 2012;7(1):28–35. doi: 10.2174/157489112799829684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alagawany M., El-Hack M., Farag M., Tiwari R., Dhama K. Biological effects and modes of action of carvacrol in animal and poultry production and health—a review. Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences. 2015;3(2s):73–84. doi: 10.14737/journal.aavs/2015/3.2s.73.84. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nostro A., Marino A., Blanco A. R., et al. In vitro activity of carvacrol against staphylococcal preformed biofilm by liquid and vapour contact. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2009;58(6):791–797. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.009274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ultee A., Bennik M. H. J., Moezelaar R. The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2002;68(4):1561–1568. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.4.1561-1568.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arfa A. B., Combes S., Preziosi-Belloy L., Gontard N., Chalier P. Antimicrobial activity of carvacrol related to its chemical structure. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2006;43(2):149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.2006.01938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo Cantore P., Shanmugaiah V., Iacobellis N. S. Antibacterial activity of essential oil components and their potential use in seed disinfection. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2009;57(20):9454–9461. doi: 10.1021/jf902333g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marei G. I. K., Abdel Rasoul M. A., Abdelgaleil S. A. M. Comparative antifungal activities and biochemical effects of monoterpenes on plant pathogenic fungi. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2012;103(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Al-Nuri M. A., Yaghmour R. M.-R., Faidi Y. R. Antimicrobial activity of Micromeria nervosa from the Palestinian area. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1997;58(3):143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baindara P., Korpole S. Recent Trends in Antifungal Agents and Antifungal Therapy. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuzarte M., Gonçalves M. J., Cavaleiro C., Dinis A. M., Canhoto J. M., Salgueiro L. R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oils of Lavandula pedunculata (miller) cav. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2009;6(8):1283–1292. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chavan P. S., Tupe S. G. Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of carvacrol and thymol against vineyard and wine spoilage yeasts. Food Control. 2014;46:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toncer O., Karaman S., Diraz E. An annual variation in essential oil composition of Origanum syriacum from Southeast Anatolia of Turkey. Journal of Medical Plants Research. 2010;4(11):1059–1064. doi: 10.5897/JMPR. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nazzaro F., Fratianni F., Coppola R., De Feo V. Essential oils and antifungal activity. Pharmaceuticals. 2017;10(4):1–20. doi: 10.3390/ph10040086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orhan I. E., Senol F. S., Haznedaroglu M. Z., et al. Neurobiological evaluation of thirty-one medicinal plant extracts using microtiter enzyme assays. Clinical Phytoscience. 2017;2(1):p. 9. doi: 10.1186/s40816-016-0023-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ballard C., Greig N., Guillozet-Bongaarts A., Enz A., Darvesh S. Cholinesterases: roles in the brain during health and disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2005;2(3):307–318. doi: 10.2174/1567205054367838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mukherjee P. K., Kumar V., Mal M., Houghton P. J. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plants. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(4):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orhan I., Şener B., Choudhary M. I., Khalid A. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of some Turkish medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;91(1):57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wszelaki N., Kuciun A., Kiss A. Screening of traditional European herbal medicines for acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Acta Pharmaceutica. 2010;60(1):119–128. doi: 10.2478/v10007-010-0006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park S. M., Ki S. H., Han N. R., et al. Tacrine, an oral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, induced hepatic oxidative damage, which was blocked by liquiritigenin through GSK3-beta inhibition. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2015;38(2):184–192. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b14-00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lowet M. E. The triglyceride lipases of the pancreas. Journal of Lipid Research. 2002;43(12):2007–2016. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200012-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomson A. B. R., De Pover A., Keelan M., Jarocka-Cyrta E., Clandinin M. T. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 286. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Publisher; 1997. Inhibition of lipid absorption as an approach to the treatment of obesity; pp. 3–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shi Y., Burn P. Lipid metabolic enzymes: emerging drug targets for the treatment of obesity. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2004;3(8):695–710. doi: 10.1038/nrd1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cho S., Choi Y., Park S., Park T. Carvacrol prevents diet-induced obesity by modulating gene expressions involved in adipogenesis and inflammation in mice fed with high-fat diet. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2012;23(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wieten L., Van Der Zee R., Spiering R., et al. A novel heat-shock protein coinducer boosts stress protein Hsp70 to activate T cell regulation of inflammation in autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2010;62(4):1026–1035. doi: 10.1002/art.27344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.