Summary

Background

Use of involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation varies widely within and between countries. The factors that place individuals and populations at increased risk of involuntary hospitalisation are unclear, and evidence is needed to understand these disparities and inform development of interventions to reduce involuntary hospitalisation. We did a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis to investigate risk factors at the patient, service, and area level associated with involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation of adults.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Clinical Register of Trials from Jan 1, 1983, to Aug 14, 2019, for studies comparing the characteristics of voluntary and involuntary psychiatric inpatients, and studies investigating the characteristics of involuntarily hospitalised individuals in general population samples. We synthesised results using random effects meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. Our review follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and is registered on PROSPERO, CRD42018095103.

Findings

77 studies were included from 22 countries. Involuntary rather than voluntary hospitalisation was associated with male gender (odds ratio 1·23, 95% CI 1·14–1·32; p<0·0001), single marital status (1·47, 1·18–1·83; p<0·0001), unemployment (1·43, 1·07–1·90; p=0·020), receiving welfare benefits (1·71, 1·28–2·27; p<0·0001), being diagnosed with a psychotic disorder (2·18, 1·95–2·44; p<0·0001) or bipolar disorder (1·48, 1·24–1·76; p<0·0001), and previous involuntary hospitalisation (2·17, 1·62–2·91; p<0·0001). Using narrative synthesis, we found associations between involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation and perceived risk to others, positive symptoms of psychosis, reduced insight into illness, reduced adherence to treatment before hospitalisation, and police involvement in admission. On a population level, some evidence was noted of a positive dose-response relation between area deprivation and involuntary hospitalisation.

Interpretation

Previous involuntary hospitalisation and diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were factors associated with the greatest risk of involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation. People with these risk factors represent an important target group for preventive interventions, such as crisis planning. Economic deprivation on an individual level and at the population level was associated with increased risk for involuntary hospitalisation. Mechanisms underpinning the risk factors could not be identified using the available evidence. Further research is therefore needed with an integrative approach, which examines clinical, social, and structural factors, alongside qualitative research into clinical decision-making processes and patients' experiences of the detention process.

Funding

Commissioned by the Department of Health and funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) via the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit.

Introduction

Involuntary admission to hospital for psychiatric care can be lifesaving1 and perceived as beneficial in the long term for some people.2 Yet, the experience of involuntary admission can be traumatic,3 frightening,4 stigmatising,5 and lead to long-term avoidance of mental health support6 and increased risk for further coercion as an inpatient.7 Rates of involuntary hospitalisation vary greatly worldwide and, in several European countries (including the UK), the number of people detained in psychiatric hospitals has risen substantially in the past three decades.8 The reasons for these international variations and increases in rates of involuntary hospitalisations cannot be accounted for fully by legislative diversity or differences in rates of severe mental illness, and remain largely unexplained.9

Variation in use of involuntary hospitalisation within countries by region, by hospital, and by population subgroup is also unexplained.6, 10 We previously reported in The Lancet Psychiatry11 findings of a companion paper that showed, compared with people from white ethnic groups, people from black Caribbean (odds ratio [OR] 2·53, 95% CI 2·03–3·16), black African (2·27, 1·62–3·19), and south Asian (1·33, 1·07–1·65) ethnic groups were at increased risk of involuntary hospitalisation. Moreover, people from migrant groups were significantly more likely to be detained when compared with native groups (OR 1·50, 95% CI 1·21–1·87).11 Again, the reasons for these disparities remain largely unexplained. Greater understanding of the clinical and social factors driving involuntary hospitalisation could clarify these variations within and between countries and could inform the interventions that are needed and where they should be targeted to help prevent or reduce use of involuntary hospitalisation.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Rates of involuntary psychiatric detentions are rising in the UK and other European countries, and reducing the use of coercive psychiatric care is a policy priority. Greater understanding of the clinical and social factors associated with an increased risk of involuntary hospitalisation is essential to inform the development and targeting of interventions aimed at reducing or preventing involuntary hospitalisations and to understand international and intranational variations in use of coercive care. We searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Clinical Register of Trials between Jan 1, 1983, and May 21, 2018, with no restriction by language. Our search terms included “mental health” OR “involuntary treatment” OR “psychiatric hospitalisation” AND “risk factor”, as well as specific potential clinical and social risk factors including “gender”, “age”, “diagnosis”, “marital status”, “family structure”, “employment status” and “living arrangements”. We repeated this search on Aug 14, 2019. We found no previous international systematic reviews or meta-analyses on this topic.

Added value of this study

To our knowledge, this report is the first systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis to review both international and UK-based studies of risk factors (with the exclusion of ethnic origin) for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation. This review benefits from consideration of both clinical and social risk factors at the area, service, and individual patient level. The main risk factors for involuntary hospitalisation were a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and previous involuntary hospitalisation. Both factors more than doubled risk for involuntary hospitalisation. We also identified that economic deprivation on an individual and population level is associated with increased risk of involuntary hospitalisation.

Implications of all the available evidence

Patients with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder or previous involuntary hospitalisation are an important target group for preventive interventions. Extending interventions such as crisis planning, which have had some success in reducing use of coercion among people with psychosis and bipolar disorder, to people who have previously been detained in hospital, could significantly reduce use of secondary involuntary hospitalisation. Understanding the mechanisms by which the risk factors we have identified contribute to involuntary hospitalisation should be a priority for future research and policy investment, to ensure equitable access to psychiatric treatment and reduce health-care inequalities.

Some factors that have been implicated in the risk for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation include a diagnosis of psychosis,12, 13, 14, 15 male gender,12, 13, 14, 16 risk of aggression,14, 17, 18 absence of of alternative community services,19 and socioeconomic deprivation.6, 20 However, research to date has been inconclusive and the factors associated with involuntary hospitalisation remain poorly understood. To our knowledge, no international systematic review or meta-analysis of the risk factors for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation has been done. We aimed to assess current evidence for the associations between clinical and social factors (with the exception of ethnic origin, which we have reviewed previously)11 and involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We included studies that compared risk factors for involuntary versus voluntary hospitalisation among psychiatric inpatients, including studies that recorded voluntary and involuntary admissions to hospital and studies that reported on patients already in hospital voluntarily and involuntarily (for this reason, we use the term involuntary hospitalisation throughout). We also included epidemiological studies that investigated factors associated with an increased risk for involuntary hospitalisation in general population samples. The primary outcome of interest was involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation and comparison groups were either patients hospitalised voluntarily or source populations (eg, the population in a specified catchment area or individuals accessing mental health services within a specified group of mental health trusts). All quantitative study designs published in peer-reviewed journals were considered. We did not assess grey literature sources. We developed our search strategy in consultation with an information scientist with experience in mental health research. We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and the Cochrane Controlled Clinical Register of Trials from Jan 1, 1983 (the year the UK Mental Health Act was enacted), to May 21, 2018, and repeated the search on Aug 14, 2019. We did not restrict our search by language. A combination of keyword and subject heading searches was used, and search terms for mental health and involuntary hospitalisation were combined with potential risk factors for involuntary hospitalisation, such as diagnosis, gender, aggressive behaviour, employment status, and socioeconomic status. Ethnic origin was not included in the final analysis to avoid duplication of results from our companion paper, a meta-analysis of ethnic variations in involuntary hospitalisation.11 Also, the wide scope of our review would have necessitated an amalgamation of ethnic groups, in direct contradiction of the main recommendations for future research in our companion paper. Study samples with a mean age younger than 18 years were excluded because risk factors for involuntary hospitalisation of children and adolescents are being investigated separately. Full search strategies are available in the appendix (pp 2–7).

Four reviewers (SW, EM, ML, and CD-L) independently identified studies that met inclusion criteria through systematic screening of all titles, then abstracts, then the full text. At each stage a random 10% check was done to ensure agreement between reviewers. We supplemented the search strategy with a backwards reference search of included studies and any relevant reviews and a forward citation search using Scopus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Six of us (SW, EM, ML, CD-L, LSR, and KT) extracted data independently using a Microsoft Excel-based broad extraction sheet, which included study design, sample size, country, diagnosis, age, gender, marital status, living status, socioeconomic status, educational level, length of stay, pathways to care, and our primary outcome measures and their associated statistical data. These factors had been identified a priori through expert consensus, but we also extracted data on any other factors associated with involuntary hospitalisation that were identified in the studies. Five reviewers (SW, EM, ML, LSR, and CD-L) assessed included studies using the Kmet 14-item checklist,21 which is a quality assessment method suitable for use with various study designs. Every study was assessed against each of the 14 items using a 3-point scale, with a score of 2 showing that criteria were fully met, 1 denoting that criteria were partly met, and 0 representing that criteria were not met. A linear summary score (total sum divided by total possible sum) from 0 to 100 was calculated and each study was then categorised as low (≤49), moderate (50–74), or high (≥75) quality. Scores for each study are available in the appendix (pp 8–11).

Data analysis

We used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (CMA version 3) and the metafor package in the statistical programme R to calculate random effects summary estimates (ORs and 95% CIs) for the association between the seven meta-analysable variables (gender, diagnosis, employment, housing status, relationship status, previous involuntary hospitalisation, and previous psychiatric hospitalisation) and involuntary hospitalisation. We included only unadjusted data in our meta-analyses. We calculated heterogeneity between studies using I2. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, 25% low heterogeneity, 50% moderate heterogeneity, and 75% high heterogeneity.22 To examine possible causes of heterogeneity, post-hoc meta-regressions were done. Possible predictors of the effect of the variables on compulsory hospitalisation examined were mean age of the study sample, female gender percentage in each study, and publication year. Mean age was chosen because of the differential risk of psychoses and other severe mental illnesses across the life course; percentage female gender was chosen as a crude measure of gendered associations; and publication year was chosen to ascertain whether there were changes in published work over time. In line with Cochrane handbook guidance,23 meta-regressions were reported only when there were ten or more studies for each variable. We also did sensitivity analyses, including only studies rated as high quality for the primary outcome of involuntary hospitalisation.

The narrative synthesis was done following guidance for systematic reviews.24 Using data in our broad extraction sheet, we identified factors that were reported inconsistently or infrequently and were more suitable for a narrative analysis than a meta-analytical approach. These included area deprivation, availability of less restrictive care, treatment compliance (including medication adherence), psychiatric symptomatology (including insight), referral pathway, risk to self and others, social support, and education level. To develop a preliminary synthesis of these factors, three of us (SW, EM, and KT) tabulated data by study and included a textual description of the identified factors, whether the direction of the association with involuntary hospitalisation was positive or negative, and if the association was significant. We also recorded any hypotheses given by the authors of the studies about the reasons behind these associations, as well as the quality rating of the study. We then regrouped data by factor of interest to investigate how each factor was associated with involuntary care across all studies. We assessed publication bias by examination of a funnel plot.25

Our review follows Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and is registered on PROSPERO, CRD42018095103.

Role of the funding source

The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

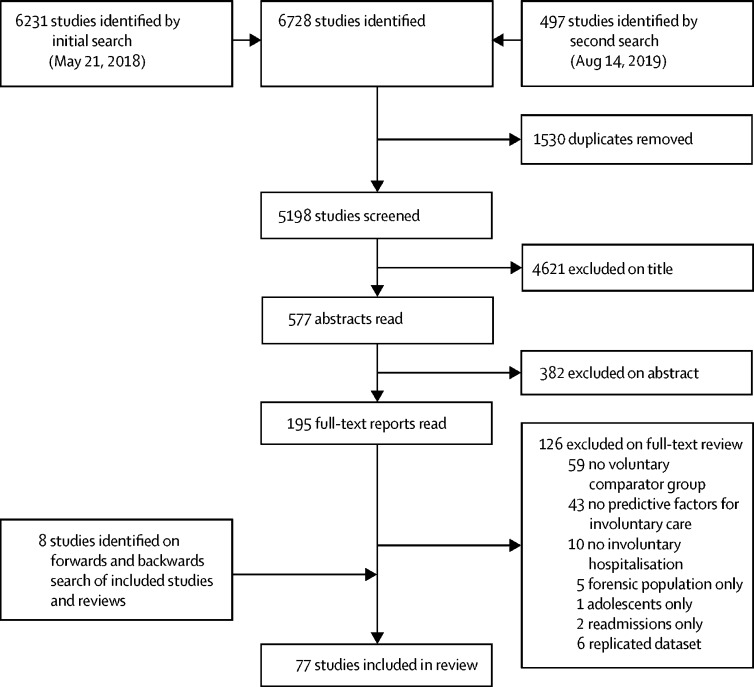

Our initial search identified 6231 studies and a repeat search identified a further 497 studies. In total, 195 full-text articles were screened, of which 69 studies met inclusion criteria and a further eight studies were identified after reference and citation searches (figure).

Figure.

Selection of studies

The key characteristics of the 77 included studies are presented in table 1. The studies were from 18 high-income countries (Australia, Canada, Israel, Taiwan, the USA, and 13 in Europe) and four middle-income countries (Brazil, China, India, and Turkey). In total, 975 004 psychiatric inpatients were represented in the study, of whom 228 239 (23%) had been admitted to hospital involuntarily. Most studies were retrospective cohort studies using hospital or national databases as data sources. Three studies used population samples, rather than comparing voluntary and involuntary inpatients,6, 20, 66 and two compared rates of compulsory care across different services.45, 53 42 studies were rated as moderate quality, 22 were rated high quality, and 13 were rated low quality. Funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias (appendix pp 12–14). A high level of heterogeneity was identified between the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study type | Setting | Sample size | Sample description | Number of involuntary admissions (% of all inpatients) | Social and clinical correlates extracted for analysis | Quality of study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguglia et al (2016)26 | Cohort | Italy | 730 | Consecutive admissions to the psychiatric inpatient unit of the San Luigi Gonzaga Hospital, Orbassano, Italy, from September, 2013, to August, 2015 | 112 (15·3%) | Age, gender, education level, relationship status, diagnosis | Moderate |

| Balducci et al (2017)27 | Cohort | Italy | 848 | Consecutive admissions to the psychiatric inpatient unit of the general teaching hospital of Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Italy, from June, 2011, to June, 2014 | 309 (36·4%) | Age, gender, relationship status, diagnosis, taking medication at the time of admission, more than one hospitalisation, risk to self | High |

| Bauer et al (2007)28 | Cohort | Israel | 34 799 | National psychiatric case registry of the Israeli Ministry of Health used to identify all adult inpatient psychiatric admissions to hospital between 1991 and 2000 | 11 156 (32·1%) | Gender, diagnosis, relationship status, years of education, risk to self | High |

| Beck et al (1984)29 | Cohort | USA | 300 | Random sample of voluntary and involuntary admissions to three adult inpatient units in the US State of Missouri over three periods (January, 1978, to June, 1978; January, 1979, to June, 1979; and January, 1980, to June, 1980) | 150 (selected control group) | None | Low |

| Bindman et al (2002)20 | Ecological | England | About 1·71 million | Purposive sample of eight mental health provider trusts in England from 1998 to 1999 | 1507 (voluntary admissions not recorded) | Number of inpatient beds, availability of less restrictive care, area deprivation | Moderate |

| Blank et al (1989)30 | Cohort | USA | 274 | All patients aged 55 years and older admitted to an old age psychiatric unit in a non-profit teaching hospital in the US State of New York from November, 1984, to December, 1985 | 75 (27·3%) | Gender, relationship status, living situation, diagnosis, risk to others, risk to self, presentation | High |

| Bonsack and Borgeat (2005)31 | Cross-sectional | Switzerland | 87 | Self-completed questionnaire given to all inpatients of the psychiatric hospital of the University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, on May 10, 2002 (response rate 96%) | 30 (34·5%) | Gender, diagnosis | Low |

| Bruns (1991)32 | Cohort | Germany | 628 | Patients who were involuntarily admitted into the psychiatric unit of Hospital Bremen-Ost in Germany, and 300 randomly chosen controls who were voluntarily admitted between 1984 and 1985 | 328 (selected control group) | Gender, relationship status | Low |

| Burnett et al (1999)33 | Cohort | England | 100 | First admissions with psychosis within southeast London in England from April, 1991, to March, 1993 | 28 (28%) | Pathways to care | Moderate |

| Canova Mosele et al (2018)17 | Cohort | Brazil | 137 | Admissions to the psychiatry service of the University Hospital of Santa Maria in Brazil from August, 2012, to January, 2013 | 71 (51·8%) | Gender, living situation, occupation, relationship status, presentation, pathways to care, risk to self, risk to others, education level | High |

| Casella and Loch (2014)34 | Cohort | Brazil | 169 | Consecutive discharges from the Philippe Pinel Psychiatric Hospital in Brazil from May, 2009, to August, 2009; those with diagnoses other than psychosis or bipolar affective disorder were excluded | 81 (48%) | Gender, relationship status, diagnosis, previous admission, presentation, correct use of medication before admission, risk to others, risk to self, social support | Moderate |

| Chang et al (2013)35 | Cohort | Brazil | 2289 | All adults hospitalised at the Institute of Psychiatry of the Clinical Hospital, University of San Paulo, Brazil, between 2001 and 2008 | 305 (13·3%) | Gender, employment, relationship status, education level, diagnosis, adherence to treatment before admission | Low |

| Chiang et al (2017)36 | Cohort | Taiwan | 26 611 | All first admissions with psychosis in Taiwan between 2004 and 2007, identified using the national health insurance database | 2540 (9·5%) | Gender, employment, previous admission | High |

| Cole et al (1995)37 | Cohort | England | 93 | People with first-onset psychosis in the catchment area for St Ann's Hospital in London, England, between July 1, 1991, and June 30, 1992 | 29 (31%) | Age, living situation, employment, pathways to care, social support | Moderate |

| Cougnard et al (2004)38 | Cohort | France | 86 | Consecutive admissions with psychosis in ten departments of psychiatry in the Bordeaux region of France between March, 2001, and March, 2002 | 53 (61·6%) | Age, gender, living situation, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, presentation, pathways to care, risk to self, criminal history, social support, educational level | High |

| Craw and Compton (2006)39 | Cohort | USA | 227 | Consecutively discharged patients from a large public sector hospital in the US State of Georgia from December, 2003, to July, 2004 | 171 (75·3%) | Age, gender, living situation, employment, relationship status, previous psychiatric hospitalisation, presentation | High |

| Crisanti and Love (2001)40 | Cohort | Canada | 1718 | Admissions to the Department of Psychiatry at the Calgary General Hospital in Alberta, Canada between April 1, 1987, and March 31, 1995 | 711 (41·4%) | Gender, diagnosis, criminal history | High |

| Curley et al (2016)16 | Cohort | Ireland | 1099 | All admissions to St Aloysius Ward, an acute adult psychiatric inpatient facility in north Dublin, Ireland, between Jan 1, 2008, and Dec 31, 2014 | 155 (14·1%) | Area deprivation (other variables repeated in Kelly et al [2018])65 | High |

| de Girolamo et al (2009)41 | Cross-sectional national survey | Italy | 1548 | All patients admitted to public or private inpatient facilities in Italy (excluding Sicily) during a 12-day period in 2004 | 196 (12·6%) | Gender, housing status, employment status, relationship status, diagnosis, availability of less restrictive care, presentation, referral pathway, risk to self, risk to others, criminal history, educational level | Moderate |

| Delayahu et al (2014)42 | Cohort | Israel | 24 | Men aged 18–60 years with a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis and substance abuse disorder who were hospitalised in an acute psychiatric dual diagnosis ward in Israel between February, 2004, and March, 2004, and between May, 2004, and June, 2004* | 9 (37·5%) | Age, relationship status, presentation on admission, risk to self, educational level | Moderate |

| Di Lorenzo et al (2018)43 | Cohort | Italy | 396 | All patients admitted to an acute psychiatric ward in northern Italy between Jan 1, 2015, and Dec 31, 2015 | 160 (40%) | Gender, living arrangements, diagnosis, employment situation, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Donisi et al (2016)44 | Cohort | Italy | 74 931 | All discharges from the 40 acute inpatient facilities in the Vento region of Italy between 2000 and 2007 | 3975 (5·3%) | Referral pathway | High |

| Emons et al (2014)45 | Cohort | Germany | 230 678 | All admissions to the largest provider of psychiatric services in Germany (Landschaftsverbands Westfalen-Lippe) from 2004 to 2009 | 17 206 (7·5%) | Area deprivation, availability of less restrictive care | Moderate |

| Eytan et al (2013)46 | Cohort | Switzerland | 2227 | All admissions to an acute psychiatric facility in Switzerland over an 8-month period in 2006 | 1422 (63·9%) | None | Moderate |

| Fok et al (2014)47 | Cohort | England | 14 233 | Adult patients with severe mental illness with and without co-morbid personality disorder between Jan 1, 2007, and Dec 31, 2011 | 3748 (26%) | None | High |

| Folnegovic-Smalc et al (2000)48 | Cohort | Croatia | 888 | All admitted patients to two acute facilities in Croatia from Jan 1, 1997, to June 30, 1997 | 173 (19%) | Gender, diagnosis | Moderate |

| Gaddini et al (2008)49 | Cross-sectional | Italy | 7984 | All adult inpatients in 369 psychiatric facilities across Italy (excluding Sicily) on May 8, 2003 | 305 (3·8%) | None | Moderate |

| Garcia Cabeza et al (1998)50 | Cross- sectional | Spain | 367 | All patients admitted to the acute unit at the psychiatric service of the hospital Gregorio Marañon in Madrid, Spain, in the first 4 months of 1994 | 67 (18%) | Gender, relationship status, employment status, living arrangements, diagnosis, pathways to care | Moderate |

| Gou et al (2014)51 | Cohort | China | 160 | Consecutive admissions to an acute psychiatric facility in China between July 26, 2012, and Sept 10, 2012 | 85 (53·1%) | Age, gender, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, presentation on admission, education | High |

| Gultekin et al (2013)52 | Cohort | Turkey | 504 | Patients admitted to an acute psychiatric facility in Turkey between May 1, 2010, and Oct 31, 2010, who had been discharged at the time of data collection | 66 (13·1%) | Gender, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, education | High |

| Hansson et al (1999)53 | Cohort | Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden | 2834 | All new patients contacting the psychiatric services in seven catchments areas over a 1-year period | 219 (7·7%) | None | Moderate |

| Hatling et al (2002)54 | Cohort | Norway | 13 985 | Patients admitted to psychiatric facilities in general hospitals in Norway in 1996 | 6476 (46·3%) | Gender, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, availability of inpatient beds | Moderate |

| Hoffman et al (2017)55 | Cohort | Germany | 213 595 | All admissions to the largest provider of psychiatric services in Germany (Landschaftsverbands Westfalen-Lippe) from 2004 to 2009 | 17 206 (8·1%) | Gender, relationship status, diagnosis, referral pathway, previous admission | Moderate |

| Hotzy et al (2019)56 | Cohort | Switzerland | 31 508 | Includes all admissions to the University Hospital of Psychiatry in Zurich, Switzerland, between 2008 and 2016; the number of admissions per patient ranged from one to ten (median two [IQR one to three]) | 8843 (28·1%) | Gender, diagnosis, education level | Moderate |

| Houston et al (2001)57 | Cohort | USA | 487 | First admissions (unclear where to) between October, 1986, and December, 1990 | 282 (58%) | None | Low |

| Hugo (1998)58 | Cohort | Australia | 402 | Inpatient admissions to an acute ward in Australia over an 8-month period | 136 (34%) | Diagnosis, presentation, risk to self, risk to others | Low |

| Hustoft et al (2012)59 | Cohort | Norway | 3326 | Consecutive admissions to 20 acute psychiatric units in Norway from 2005 to 2006 | 1453 (44%) | Gender, housing stability, employment, relationship status, presentation on admission, referral pathway, education level, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Ielmini et al (2018)60 | Cohort | Italy | 200 | 200 adult psychiatric inpatients hospitalised at the General Hospital Psychiatric Ward in Varese, Italy, from January, 2014, to March, 2017 | 100 (selected control group) | Age, gender, housing stability, employment, relationship status, presentation on admission, risk to others, having social support | Moderate |

| Indu et al (2018)61 | Case-control | India | 300 | Consecutive compulsory admissions and the two following voluntary admissions to the Indian Government's mental health centre in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, from June, 2010, to February, 2011 | 100 (33%) | Gender, housing stability, employment status, relationship status, diagnosis, previous involuntary admission, presentation, compliance, having social support, education level | Moderate |

| Isohanni et al (1991)62 | Case-control | Finland | 1586 | Admissions to a closed psychiatric ward with modified therapeutic community principles in Oulu, Finland, between 1978 and 1987 | 215 (13·6%) | Age, diagnosis, previous admission | Moderate |

| Iversen et al (2002)63 | Cohort | Norway | 223 | All patients admitted to four acute wards in Norway from October, 1998, to November, 1999 | 150 (67%) | Gender, diagnosis, presentation | Moderate |

| Kelly et al (2004)64 | Cohort | Ireland | 78 | Patients with first-episode psychosis admitted to two psychiatric hospitals in Dublin, Ireland, over a 4-year period | 17 (22%) | Age, gender, presentation | Moderate |

| Kelly et al (2018)65 | Cohort | Ireland | 2940 | All adult admissions to three acute psychiatric hospitals in Dublin, Ireland, from 2008 to 2015 (Dublin Involuntary Admission Study) | 423 (14·4%) | Gender, employment, relationship status, diagnosis | Moderate |

| Keown et al (2016)66 | Cohort | England | Population of 138 primary care trusts | All adult psychiatric admissions in England in 2010 and 2011; data from the Mental Health Minimum Data Set | Unclear | Area deprivation | High |

| Lastra Martinez et al (1993)67 | Cross-sectional | Spain | 298 | Clinical records of patients admitted to the acute unit of the psychiatric service of a general hospital (San Carlos University Hospital) in Madrid, Spain, between March, 1990, and February, 1991 | 148 (voluntary group is a selected control group) | Gender, relationship status, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Lay et al (2011)68 | Cohort | Switzerland | 9698 | All patients admitted to psychiatric inpatient facilities in Zurich, Switzerland, in 2007 | 2406 (24·8%) | Age, gender, housing stability, employment, diagnosis, inpatient beds, education level, presentation on admission | Moderate |

| Lebenbaum et al (2018)69 | Cohort | Canada | 115 515 | All patients admitted to mental health beds in the Canadian Province of Ontario from 2009 to 2013 | 85 607 (74·1%) | Gender, housing stability, diagnosis, previous involuntary admission, referral pathways, risk to self, risk to others, presentation on admission | High |

| Leung et al (1993)70 | Case-control | USA | 44 | Admissions of Indochinese patients to a psychiatric facility in the US State of Oregon in 1985 and 1986; all involuntary admissions were included, and the same number of voluntary patients was selected randomly | 22 (selected control group) | Gender, housing stability, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, previous involuntary admission, previous admission, education level | Moderate |

| Lin et al (2019)71 | Case-control | Taiwan | 10 190 | All inpatients in Taiwan with a principal diagnosis of schizophrenia between 2007 and 2013; all involuntary patients were included and matched to four voluntary patients based on age, gender, and year of admission | 2038 (selected control group) | Risk to self, previous admission | Moderate |

| Lorant et al (2007)72 | Cohort | Belgium | 346 | Random sample of 1200 patients referred to one of six psychiatric inpatient units in Brussels, Belgium, in 2004 | 154 (44·5%) | Age, availability of less restrictive care, compliance with treatment before admission, risk to self, risk to others | High |

| Luo et al (2019)73 | Cross-sectional | China | 155 | All patients with a diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder admitted to 16 psychiatric institutions in China in an index month (March 15, 2013, to April 15, 2013) | 81 (52%) | Gender, employment status, relationship status, education level, previous outpatient treatment, previous hospitalisation, risk to self, risk to others, presentation | Moderate |

| Malla et al (1987)74 | Cohort | Canada | 5729 | Consecutive admissions to four psychiatric facilities in the Canadian Province of Ontario between October, 1975, and October, 1978 | 724 (12·6%) | Gender, employment, relationship status, referral pathways, diagnosis, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Mandarelli et al (2014)75 | Case-control | Italy | 60 | Consecutive involuntary admissions to a psychiatric inpatient unit in Rome, Italy, between October, 2009, and April 2010; each inpatient was matched for age and sex to a voluntarily admitted patient from the same hospital over the same period | 30 (selected control group) | Relationship status, diagnosis, presentation, risk to self | Moderate |

| Montemagni et al (2011)76 | Cohort | Italy | 119 | Patients with schizophrenia consecutively admitted to an emergency psychiatric ward in Turin, Italy, between December, 2007, and December, 2009 | 34 (28·5%) | Age, gender, employment, relationship status, previous involuntary admission, presentation | Moderate |

| Montemagni et al (2012)77 | Cohort | Italy | 848 | Consecutive admissions to an emergency psychiatric ward in Turin, Italy, between January, 2007, and December, 2008 | 146 (17%) | Age, diagnosis, education level, risk to self, presentation | Moderate |

| Myklebust et al (2012)78 | Cohort | Norway | 1963 | Admissions to a psychiatric hospital in northern Norway from 2003 to 2006 | 183 (9·3%) | Age, gender, diagnosis, presentation on admission, referral pathway | Moderate |

| Okin (1986)79 | Cross-sectional | USA | 198 | All admissions to seven state psychiatric hospitals in the US State of Massachusetts over a 2-week period in 1981 | 94 (47·5%) | Gender, housing stability, diagnosis, previous admission, relationship status, education, risk to self, risk to others | Low |

| Olajide et al (2016)80 | Cohort | England | 2087 | Patients referred for a Mental Health Act assessment in London, Birmingham, or Oxfordshire in England between the months of July and October in 2008–11 | 1396 (66·9%) | Age, diagnosis, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Opjordsmoen et al (2010)81 | Cohort | Norway | 217 | Inpatients with first-episode psychosis in four psychiatric facilities in Norway from January, 1997, to December, 2000 | 126 (58·1%) | Gender, relationship status, presentation, education level | Moderate |

| Opsal et al (2011)82 | Cross-sectional | Norway | 1187 | All patients with a history of substance abuse admitted to 39 acute psychiatric wards in Norway over a 3-month period in 2005–06 | 361 (30·4%) | Gender, housing stability, employment status, diagnosis, presentation, risk to self, referral pathways | Moderate |

| Polachek et al (2017)83 | Cohort | Israel | 5411 | All patients with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder discharged from a mental health centre between January, 2010, and April, 2013 | 2109 (39%) | Gender | Low |

| Riecher et al (1991)84 | Cohort | Germany | 10 749 | All patients admitted to psychiatric hospital in Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany, between Jan 1, 1984, and June 30, 1986 | 517 (4·8%) | Gender, housing stability, employment, relationship status diagnosis, previous admission | Moderate |

| Ritsner et al (2015)85 | Cohort | Israel | 439 | All patients admitted to the Sh'ar Menashe mental health centre in Israel between March 1, 2012, and Feb 28, 2013 | 106 (24·1%) | Age, gender, diagnosis, presentation, risk to self | Low |

| Rodrigues et al (2019)7 | Cohort | Canada | 5191 | All patients from a cohort of young people (aged 16–35 years) with a diagnosis of non-affective psychosis who were hospitalised over a 2-year follow-up period from the initial diagnosis | 4208 (84%) | Gender, living arrangements, social support, risk to self, risk to others, presentation, previous hospitalisation, adherence to treatment before hospitalisation, pathways to care | High |

| Rooney et al (1996)86 | Case-control | Ireland | 101 | Consecutive involuntary admissions to an inpatient psychiatric unit in Dublin, Ireland, over 6 months were compared with a sample of voluntary patients in the same hospital | 58 (selected control group) | Gender, diagnosis, referral pathways, risk to self, risk to others | Low |

| Schmitz-Buhl et al (2019)87 | Cohort | Germany | 5764 | All patients involuntarily hospitalised in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in Cologne, Germany, in 2011; 3991 patients treated voluntarily in the same hospitals over the same period served as a control group | 1773 (voluntary group is a selected control group) | Education level, risk to self | Moderate |

| Schuepbach et al (2006)88 | Cohort | Switzerland | 86 | Inpatients with an acutely manic or mixed episode of bipolar disorder in the Swiss cohort of the EMBLEM study | 55 (64%) | Gender, relationship status, presentation on admission, compliance with medication before admission | Moderate |

| Schuepbach et al (2008)89 | Cross-sectional | 14 European countries | 1374 | A sample of inpatients with an acutely manic or mixed episode of bipolar disorder enrolled in the EMBLEM study | 561 (40·8%) | Gender, housing stability, relationship status, presentation, compliance with medication before admission, risk to self, education level | Moderate |

| Serfaty and McCluskey (1998)90 | Case series | England | 12 | A sample of 11 inpatients with a diagnosis of an eating disorder | 7 (58·3%) | Diagnosis, presentation | Low |

| Silva et al (2018)91 | Cohort | Switzerland | 5027 | All consecutive admissions to four psychiatric hospitals in the Canton of Vaud, Switzerland, between Jan 1, 2015, and Dec 31, 2015 | 1918 (38·2%) | Gender, relationship status, diagnosis, risk to self, risk to others, previous psychiatric hospitalisation, previous involuntary hospitalisation | High |

| Spengler (1986)92 | Cohort | Germany | 206 | Consecutive new contacts with the psychiatric emergency department who were admitted to public psychiatric hospitals in Hamburg, Germany, from January, 1980, to September, 1981 | 122 (59·2%) | Gender, housing stability, employment, relationship status, diagnosis, presentation, compliance with treatment before admission, risk to self | High |

| Stylianidis et al (2017)93 | Cohort | Greece | 715 | All patients admitted to the psychiatric hospital of Attica, Greece, from June, 2011, to October, 2011 | 427 (59·7%) | Age, gender, employment status, relationship status, diagnosis, previous admission, social support, education | High |

| Tørrissen (2007)94 | Cohort | Norway | 104 | All patients discharged from an acute ward in the Norwegian county of Hedmark from January, 2005, to June, 2005 | 49 (47%) | Age, diagnosis | Low |

| van der Post et al (2009)95 | Cohort | Netherlands | 7600 | Consecutive patients presenting to emergency psychiatric services in Amsterdam and admitted to an inpatient unit between Sept 15, 2004, and Sept 15, 2006 | 352 (46·3%) | Previous involuntary admission, referral pathway, presentation, risk to self, risk to others | Moderate |

| Wang et al (2015)96 | Cohort | Taiwan | 2777 | Admissions to psychiatric hospital from the emergency psychiatric service from January, 2009, to December, 2010 | 110 (4·0%) | Age, gender, diagnosis, presentation on admission, referral pathways, risk to self | Moderate |

| Watson et al (2000)97 | Cohort | USA | 397 | Consecutive patients with an eating disorder referred for admission in the University of Iowa hospital between July, 1991, and June, 1998 | 66 (16·6%) | Gender, relationship status | Low |

| Weich et al (2017)6 | Cross-sectional | England | 1 238 188 total sample; 104 647 inpatient admissions | All patients who received care at 64 NHS provider trusts in 2010–11; data from the Mental Health Minimum Data Set | 42 915 (3·5% of total sample, 41·0% of the inpatient sample) | Gender, area deprivation, inpatient beds, availability of less restrictive care | High |

EMBLEM=European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication. NHS=National Health Service.

The full meta-analysis results are presented in table 2 and a meta-analysis restricted to high-quality studies is presented in table 3. Forest plots are available in the appendix (pp 18–35).

Table 2.

Risk factors for involuntary care

| Number of studies (k) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male vs female | 53 | 1·23 (1·14–1·32) | 94·22% |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Psychosis | 37 | 2·18 (1·95–2·44) | 94·78% |

| Bipolar disorder | 14 | 1·48 (1·24–1·76) | 61·24% |

| Depression | 10 | 0·22 (0·15–0·33) | 85·87% |

| Mood disorder | 20 | 0·59 (0·50–0·69) | 95·73% |

| Anxiety | 11 | 0·80 (0·68–0·95) | 76·22% |

| Personality disorder | 26 | 0·78 (0·65–0·93) | 92·66% |

| Anorexia | 2 | 1·19 (0·21–6·72) | 95·99% |

| Substance misuse | 23 | 0·81 (0·66–1·00) | 95·19% |

| Organic disorder | 14 | 1·57 (1·08–2·27) | 97·82% |

| Neurosis | 8 | 0·37 (0·19–0·73) | 98·11% |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed | 20 | 1·43 (1·07–1·90) | 91·28% |

| Student | 3 | 0·88 (0·28–2·79) | 74·61% |

| Homeworker | 2 | 1·36 (0·27–6·83) | 75·83% |

| Welfare benefits | 8 | 1·71 (1·28–2·27) | 71·73% |

| Retired | 7 | 1·41 (0·92–2·17) | 76·62% |

| Dependent | 2 | 1·08 (0·67–1·74) | 93·44% |

| Housing | |||

| Homeless | 7 | 1·22 (0·88–1·69) | 91·27% |

| Living alone | 13 | 1·24 (0·94–1·65) | 75·37% |

| Friend or relative | 6 | 1·14 (0·73–1·78) | 69·00% |

| Living in an institution | 5 | 0·88 (0·47–1·63) | 71·41% |

| Non-owner vs owner | 3 | 1·49 (1·04–2·15) | 87·02% |

| Relationship | |||

| Single | 28 | 1·47 (1·18–1·83) | 97·22% |

| Separated or divorced | 11 | 0·96 (0·67–1·39) | 75·46% |

| Widowed | 7 | 0·81 (0·32–2·05) | 89·36% |

| Previously married | 6 | 1·26 (1·12–1·42) | 59·21% |

| Previous involuntary hospitalisation | |||

| Yes vs no | 6 | 2·17 (1·62–2·91) | 84·23% |

| Previous admission | |||

| Yes vs no | 12 | 0·86 (0·58–1·28) | 94·22% |

Table 3.

Risk factors for involuntary care, restricted to high-quality studies

| Number of studies (k) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male vs female | 16 | 1·32 (1·16–1·51) | 96·90% |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Psychosis | 10 | 2·19 (1·80–2·66) | 94·85% |

| Bipolar disorder | 3 | 1·06 (0·70–1·60) | 67·37% |

| Depression | 2 | 0·10 (0·06–0·17) | 0% |

| Mood disorder | 6 | 0·46 (0·36–0·60) | 97·12% |

| Anxiety | 2 | 0·56 (0·09–3·42) | 53·16% |

| Personality disorder | 5 | 0·60 (0·37–0·98) | 93·12% |

| Anorexia | 0 | NA | NA |

| Substance misuse | 4 | 0·66 (0·52–0·84) | 9·20% |

| Organic disorder | 4 | 1·92 (0·72–5·08) | 97·76% |

| Neurosis | 2 | 0·55 (0·45–0·67) | 0% |

| Employment | |||

| Unemployed | 7 | 1·46 (1·04–2·05) | 32·80% |

| Student | 1 | NA | NA |

| Homeworker | 2 | 1·36 (0·27–6·83) | 75·83% |

| Welfare benefits | 1 | NA | NA |

| Retired | 3 | 1·19 (0·50–2·81) | 49·65% |

| Dependent | 1 | NA | NA |

| Housing | |||

| Homeless | 3 | 0·58 (0·22–1·57) | 85·07% |

| Living alone | 5 | 0·68 (0·39–1·20) | 67·82% |

| Friend or relative | 1 | NA | NA |

| Living in an institution | 2 | 0·72 (0·06–9·42) | 88·63% |

| Non-owner vs owner | 1 | NA | NA |

| Relationship | |||

| Single | 9 | 1·18 (0·85–1·64) | 91·72% |

| Separated or divorced | 4 | 0·53 (0·23–1·25) | 89·62% |

| Widowed | 3 | 1·27 (0·37–4·46) | 90·20% |

| Previously married | 3 | 1·12 (1·06–1·20) | 0% |

| Previous involuntary hospitalisation | |||

| Yes vs no | 2 | 1·58 (1·32–1·90) | 82·68% |

| Previous admission | |||

| Yes vs no | 5 | 0·75 (0·55–1·02) | 94·71% |

NA=not available.

Looking at demographic characteristics, men were more likely to be detained involuntarily in hospital than were women (OR 1·23, 95% CI 1·14–1·32; table 2) and this effect remained when restricted to high-quality studies (1·32, 1·16–1·51; table 3). An association was noted between involuntary psychiatric admission and being unemployed in both the full meta-analysis (OR 1·43, 95% CI 1·07–1·90; table 2) and high-quality meta-analysis (1·46, 1·04–2·05; table 3). Being on welfare benefits was associated with an increased risk of detention in the full meta-analysis (OR 1·71, 95% CI 1·28–2·27; table 2) but was included in only one high-quality study (table 3). Involuntary psychiatric admission was associated with renting compared with owning one's home (OR 1·49, 95% CI 1·04–2·15; table 2), although this risk factor was reported in only three studies and small numbers precluded meta-analysis of high-quality studies only (table 3). Being single (OR 1·47, 95% CI 1·18–1·83) or previously married (1·26, 1·12–1·42) were both associated with involuntary hospitalisation (table 2), but only the association with previous marriage remained in the meta-analysis of high-quality studies (1·12, 1·06–1·20; table 3).

Looking at psychiatric diagnoses, individuals with a diagnosis of psychosis (OR 2·18, 95% CI 1·95–2·44) or bipolar affective disorder (1·48, 1·24–1·76) were significantly more likely to be admitted to hospital involuntarily than were those with other mental health diagnoses (table 2). This effect remained for psychosis when the analysis was restricted to high-quality studies (OR 2·19, 95% CI 1·80–2·66), but not for bipolar affective disorder (table 3). By contrast, having a diagnosis of depression, mood disorder (type not specified), anxiety, personality disorder, or neurosis (used as a general category of non-psychotic illness) was associated with voluntary rather than involuntary hospitalisation (table 2). This effect remained in the high-quality studies for all of these diagnoses except anxiety (table 3).

As well as having a psychotic disorder, the risk factor that was associated most strongly with involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation was previous involuntary hospital admission (OR 2·17, 95% CI 1·62–2·91; table 2). Only two high-quality studies considered previous involuntary hospitalisation but the association remained significant (OR 1·58, 95% CI 1·32–1·90; table 3).

The results of meta-regressions are included in the appendix (pp 15–17). Neither mean age of the study sample, percentage female gender, nor publication date predicted any associations.

Positive symptoms of psychosis were measured in ten moderate to highly rated studies using either the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Health of the Nation Outcome Scores (HoNOS) or the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS),17, 41, 51, 58, 63, 69, 75, 76, 77, 81 and all but one of these studies51 identified a significant association between positive symptoms and involuntary rather than voluntary hospitalisation. By contrast, eight studies measured symptoms of mood or anxiety disorders using the BPRS, HoNOS, PANSS, or Hamilton Depression Scale,38, 41, 58, 75, 77, 81, 88, 89 and six of these identified a significant association with voluntary rather than involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation.38, 41, 58, 77, 81, 89

Eight studies of moderate to high quality reported on levels of insight and all found that lack of insight was strongly associated with involuntary hospitalisation.7, 42, 51, 64, 73, 76, 88, 89 However, only four studies reported how insight had been measured: two used the Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire,51, 73 one used the Scale for the Assessment of Unawareness of Mental Disorder,76 and one used PANSS (in which one item is labelled “lack of judgement and insight”, which is rated on a seven-point Likert scale).64 Two of the eight studies that reported on levels of insight found that lack of insight was the strongest predictor of involuntary hospitalisation.7, 73

Adherence to treatment and compliance with medication before hospitalisation was investigated in seven studies of low to moderate quality and in one high-quality study. Six studies identified an association between poor treatment compliance and involuntary rather than voluntary hospitalisation,7, 61, 88, 89, 92, 95 and one of these studies found that lack of adherence to medication in the 4 weeks before admission was the most powerful predictor of involuntary hospitalisation.89 Two studies noted no effect.34, 35

The association between involuntary hospitalisation and risk to self was widely reported, although whether the assessment of risk was based on previous self-harm or suicide attempts, or expressions of suicidal ideation, was often unclear. Nine studies found that suicidal behaviour, ideation, and history were associated with voluntary rather than involuntary hospitalisation.17, 27, 28, 43, 67, 80, 82, 85, 86 In five studies, risk to self was associated with involuntary admission,7, 69, 72, 74, 87 whereas in 17 studies, no association was noted between risk to self and the legal status of admission.30, 34, 38, 41, 42, 58, 59, 71, 73, 75, 77, 79, 89, 91, 92, 95, 96

18 studies reported on risk to others and all noted a positive association with involuntary hospitalisation.7, 17, 30, 34, 41, 43, 58, 59, 60, 67, 69, 72, 73, 74, 79, 80, 91, 95 However, measurement and definition of risk to others was inconsistent throughout these studies, with scant use of formal assessment scales. Three studies used HONOS to record levels of aggression,58, 59, 91 two used the Overt Aggression Scale,17, 73 two used the Risk of Harm to Others Scale,7, 69 and two used an item of the Personal and Social Performance scale (disturbing and aggressive behaviour,41 and danger to others).95 Four studies used information from patients' notes,30, 43, 74, 80 but only one of these studies was clear about requiring a record of an actual incident of violent behaviour.74 In one study,79 risk to others was assessed by interviews with family members, who were asked if there were any verbal threats to harm someone and aggressive outbursts in the week before admission. In the remaining four studies, measurement of the level of risk to others was unclear.

In nine studies, a strong association was noted between police involvement in admission and involuntary care.7, 17, 33, 50, 69, 74, 82, 95, 96 By contrast, involvement of a general practitioner or family doctor in the referral or admission process was associated with a significantly increased likelihood of voluntary rather than involuntary care in all studies that measured this risk factor.33, 37, 59, 69

The relation between social support and involuntary hospitalisation was reported in seven studies.7, 34, 37, 38, 60, 61, 93 These all measured social support in different ways, including patient report of perceived social support,37, 38, 60, 61, 93 patient's social network reporting feeling overwhelmed by the illness,7 and the number of family visits the patient had while in hospital.34 Five studies identified an association between limited social support and involuntary hospitalisation, whereas two found no association. Only one study used a formal measure of social support, the Oslo social support scale, and found that higher levels of perceived social support were independently linked to a lower probability of involuntary hospitalisation.93

Evidence for an association between availability of inpatient beds and involuntary hospitalisation was sparse and inconclusive.6, 54, 68 Adequacy of community services and the rate of involuntary hospitalisation were investigated in four studies. One German study of moderate quality identified reduced rates of involuntary care in settings where community services provided more home visits.45 In one UK study, availability of home visits after 2200 h was associated with reduced use of admission under Section 2 of the Mental Health Act.20 Another high-quality UK study found that the availability of alternative less restrictive forms of care was the most crucial factor in determining whether to admit patients involuntarily.72 However, a population-based high-quality study showed that mental health-care trusts in England in which community services were rated more highly by service users had greater numbers of patients admitted involuntarily.6

The relation between area-level deprivation and involuntary hospitalisation was examined in only four studies,6, 20, 45, 66 three of which were from the UK. In two studies,6, 66 the same dataset was used but different measures were implemented to assess deprivation. Findings from all three UK studies6, 20, 66 showed that the greater the level of area deprivation, the higher the rate of involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation. The study from Germany,45 which compared clinics with high and low rates of involuntary hospitalisation, also found that the clinics with high rates of involuntary hospitalisations were in areas where there were significantly higher rates of unemployment, increased population density, and less homogeneity of incomes.

Discussion

The findings of our meta-analysis show that the risk factors associated most strongly with involuntary hospitalisation for psychiatric care are a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and previous involuntary hospitalisation. People with either of these risk factors had more than double the odds of being hospitalised against their will than did people without them. Psychotic disorders can be among the most severe and disabling mental health conditions, and it is perhaps reassuring that mental health legislation is being used most frequently for people with the most severe mental health needs. However, although many studies in our review looked at psychosis as a risk factor for involuntary hospitalisation, there remains a paucity of knowledge about what specific factors might increase the risk for involuntary admission in someone with psychosis, and the pathways and mechanisms by which this occurs (panel).4, 7, 64, 100 Previous involuntary hospitalisation as a risk factor for future involuntary admission has been reported much less frequently. The mechanisms behind this association are unclear, but are likely to be multifaceted and include the fluctuating nature of serious mental illness as well as clinical decision-making processes. Furthermore, previous involuntary hospitalisation can be experienced as traumatic and negatively affect future engagement with mental health services.6, 101 This factor might mean that people who have previously been detained do not seek help until the point of crisis, when a further involuntary hospitalisation might be needed.

Panel. Lived-experience commentary by Rachel Rowan Olive, Patrick Nyikavaranda.

The clinical risk factors identified in the studies reviewed by Walker and colleagues largely measure clinical opinion, which might be a poor proxy for actual need and experience. There is a risk of circular logic: individuals judged to have more severe symptoms were more likely to be detained, but several measures on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (eg, suspiciousness and hostility) would probably be exacerbated by detention. Relatively few studies included in the meta-analysis highlight the effect of either assessing clinicians' manner or hospital environment on presentations and assessments. This omission is especially problematic with respect to constructs such as insight, which is contested by legal, clinical, and service user or survivor experts. Insight is often poorly defined and can be used to pathologise disagreement with treatment plans or non-medical understandings of one's own experience.98, 99

However, we also have concerns about apparently objective criteria such as previous involuntary admissions. A patient's clinical history wears a path that unconsciously directs the feet of clinicians meeting the patient for the first time: when an individual has been detained before, it takes a brave approved mental health professional–doctor team to make a different decision at the next Mental Health Act assessment, going against the grain of their colleagues' past judgments. We, therefore, caution against planning interventions targeted at specific clinical groups based on the evidence reviewed here without further examining the role of the detaining clinicians' subjectivity, biases, and anxieties.

Further research is also needed to investigate the experiences of individuals who have been involuntarily admitted. This work might help to determine why some groups of people are the most likely to be hospitalised involuntarily. However, we remain concerned about the paucity of legal safeguards against coercion during voluntary admissions, making some such admissions de facto detentions. It is difficult to ascertain real differences in experience between voluntary and involuntary hospitalisations. We would like to see this consideration integrated into future research and policy recommendations in this area.

Crisis-planning interventions can substantially reduce the risk of involuntary hospitalisation among people with psychosis and bipolar affective disorder.102, 103 Ensuring that these interventions are offered consistently to individuals with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and to those who have previously been detained could contribute to a reduction in use of coercive care. Moreover, the significant association between previous involuntary hospitalisation and risk of future involuntary hospitalisation could provide an explanation for the acceleration in rates of involuntary hospitalisation in some countries and within some population subgroups.8

Using meta-analysis, we also identified sociodemographic and socioeconomic risk factors associated with involuntary hospitalisation: these were male gender, single marital status, unemployment, being in receipt of welfare benefits, and not owning one's own home. These findings should be interpreted alongside those of our companion paper,11 in which we identified that all ethnic minority groups studied were at increased risk of involuntary hospitalisation, but patients of black Caribbean and black African ethnic origin were at greatest risk and had more than double the odds of an involuntary hospitalisation than did people from white ethnic groups. Explanations for these sociodemographic and socioeconomic associations are limited and rarely based on primary evidence.

Using narrative synthesis, we were able to examine further some of the features associated with involuntary hospitalisation, although unfortunately not how these features interacted with each other or potentially affected the other risk factors we identified. On an individual level, we found that factors associated with involuntary hospitalisation were positive symptoms of psychosis, perceived risk to others, clinician-rated lack of insight, lack of adherence to treatment before hospitalisation, scant social support, and police (vs family doctor) involvement in admission. However, the methods by which some of these factors were assessed were unclear. Only three studies reported levels of insight based on a formal questionnaire; social support was formally measured in just one study; and assessment of risk was typically unspecified. This lack of clarity into constructions such as risk and insight precludes methodological enquiry.

The finding of a greater likelihood of involuntary care among people with single marital status and those without social support could be a reflection of the associations that are increasingly recognised between loneliness, scant social support, and severe mental health difficulties.104, 105 It might also reflect the role that friends and family may have in encouraging and facilitating help-seeking by voluntary means, a role that may be all the more important when community-based support from statutory and voluntary sectors are reduced.106 On a population level, we identified a positive dose-response relation between area-level deprivation and increased rates of involuntary hospitalisation, although this association was reported in only four studies. The bidirectional link between poverty and poor physical and mental health is well established,107 but the reasons why people who are subject to economic deprivation (on an individual and population level) should be more likely to be hospitalised against their will remain unclear. Understanding the mechanisms behind this health-care inequality should now be a research and policy priority.

Our study has several limitations. Ethnic origin is an important risk factor for involuntary hospitalisation and probably intersects with many risk factors we have identified. As such, our review should be read in light of the findings from our companion paper on ethnic variations in detention.11 Most studies we included in our review were from high-income countries, which is a major limitation and precluded investigation of risk factors for involuntary care in low-income or lower-middle income countries, where community mental health services are typically more rare. However, despite this homogeneity, the countries represented by the studies we included in our review are diverse with respect to legal and health-care systems.9 It is likely that this diversity, along with the wide range of study methodologies, study settings, populations, and periods studied have contributed to the high heterogeneity of results. Our focus on peer-reviewed quantitative research only is a limitation, since some countries might not have published such research on involuntary hospitalisation. Future research would benefit from inclusion of a wider range of sources, including qualitative work on clinical decision-making processes and service-user and carer experiences of inpatient psychiatric care and pathways into it.4 Although the correlation between perceived coercion and legal status is high, many patients voluntarily admitted to hospital feel highly coerced, whereas some who were involuntarily admitted report little or no coercion.81, 108 Finally, results were limited by most studies reporting group-level characteristics over individual data, preventing examination of the interplay of various risk factors and the mechanisms of their contribution to involuntary psychiatric detention.

Despite these limitations, our study updates current research on the associations between social and clinical factors and involuntary hospitalisation. We have identified potential target groups for interventions to prevent or reduce use of involuntary care. This targeting is imperative as the importance of liberty and autonomy over paternalism and authority is increasingly recognised and prioritised within mental health policy and practice internationally.14, 109, 110 Further research needs to focus on confirming prospectively in current cohorts the risk factors for involuntary hospitalisation; elucidating the mechanisms that underpin these risk factors at individual, group, service and area level; and using this evidence to inform the development and implementation of targeted strategies to reduce the use of involuntary treatment and to improve equity of access to mental health care. This work should occur alongside fine-grained research into the processes implicated in clinical decision making around involuntary hospitalisation, including assessments of risk and insight, and the experiences of individuals subject to involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation.

Data sharing

We are happy to share all data collected for this Article, including data extraction tables and the statistical analysis. These data will be available from the publication date. Please contact the corresponding author if you would like to see any data that are not included in the Article or appendix.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme, conducted through the NIHR Policy Research Unit (PRU) in Mental Health (PR-PRU-0916-22003) to support the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or its arm's length bodies, or other government departments. CD-L, KT, BL-E, and SJ are supported by the Mental Health PRU. SW is funded by an NIHR Doctoral Research Fellowship for this research project. Rachel Rowan Olive and Patrick Nyikavaranda (NIHR Mental Health PRU Lived Experience Working Group) provided invaluable input throughout the project and the statement to accompany this study.

Editorial note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributors

SJ and BL-E contributed to the original study proposal. SW and EM drafted the original protocol with revisions by SJ and BL-E. SW and EM led the screening and data extraction process. SW, EM, LSR, ML, CD-L, and KT independently screened papers and extracted data. EM and SW wrote the statistical analysis plan. PB and EM did the statistical analysis. SW wrote the draft report. PB, LSR, ML, CD-L, KT, SJ, and BL-E provided content expertise and methodological guidance. All authors contributed to consecutive drafts and approved the final report.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Wang DWL, Colucci E. Should compulsory admission to hospital be part of suicide prevention strategies? BJPsych Bull. 2017;41:169–171. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.116.055699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priebe S, Katsakou C, Amos T. Patients' views and readmissions 1 year after involuntary hospitalisation. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:49–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, Grubaugh AL, Sauvageot JA. Patients' reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:1123–1133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akther SF, Molyneaux E, Stuart R, Johnson S, Simpson A, Oram S. Patients' experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BJPsych Open. 2019;5:e37. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel K, Tuckel P. Suicide and civil commitment. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1987;12:343–360. doi: 10.1215/03616878-12-2-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weich S, McBride O, Twigg L. Variation in compulsory psychiatric inpatient admission in England: a cross-classified, multilevel analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:619–626. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues R, MacDougall AG, Zou G. Involuntary hospitalization among young people with early psychosis: a population-based study using health administrative data. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keown P, Murphy H, McKenna D, McKinnon I. Changes in the use of the Mental Health Act 1983 in England 1984/85 to 2015/16. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:595–599. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheridan Rains L, Zenina T, Dias MC. Variations in patterns of involuntary hospitalisation and in legal frameworks: an international comparative study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:403–417. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinkler M, Priebe S. Detention of the mentally ill in Europe: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:3–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnett P, Mackay E, Matthews H. Ethnic variations in compulsory detention under the Mental Health Act: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:305–317. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30027-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riecher A, Rossler W, Loffler W, Fatkenheuer B. Factors influencing compulsory admission of psychiatric patients. Psychol Med. 1991;21:197–208. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700014781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riecher-Rossler A, Rossler W. Compulsory admission of psychiatric patients: an international comparison. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salize HJ, Dressing H, Peitz M. Compulsory admission and involuntary treatment of mentally ill patients: legislation and practice in EU-Member States—final report. May 15, 2002. https://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2000/promotion/fp_promotion_2000_frep_08_en.pdf

- 15.Ng XT, Kelly BD. Voluntary and involuntary care: three-year study of demographic and diagnostic admission statistics at an inner-city adult psychiatry unit. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35:317–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curley A, Agada E, Emechebe A. Exploring and explaining involuntary care: the relationship between psychiatric admission status, gender and other demographic and clinical variables. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2016;47:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canova Mosele PH, Chervenski Figueira G, Antônio Bertuol Filho A, Ferreira de Lima JAR, Calegaro VC. Involuntary psychiatric hospitalization and its relationship to psychopathology and aggression. Psychiatry Res. 2018;265:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yesavage JA, Werner PD, Becker JM, Mills MJ. The context of involuntary commitment on the basis of danger to others: a study of the use of the California 14-day certificate. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170:622–627. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myklebust LH, Sorgaard K, Wynn R. Local psychiatric beds appear to decrease the use of involuntary admission: a case-registry study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bindman J, Tighe J, Thornicroft G, Leese M. Poverty, poor services, and compulsory psychiatric admission in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:341–345. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kmet LM, Lee RC, Cook LS. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Feb 1, 2004. https://www.ihe.ca/publications/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org

- 24.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. April, 2006. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.php

- 25.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguglia A, Moncalvo M, Solia F, Maina G. Involuntary admissions in Italy: the impact of seasonality. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2016;20:232–238. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2016.1214736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balducci PM, Bernardini F, Pauselli L, Tortorella A, Compton MT. Correlates of involuntary admission: findings from an Italian inpatient psychiatric unit. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29:490–496. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2017.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer A, Rosca P, Grinshpoon A. Trends in involuntary psychiatric hospitalization in Israel 1991–2000. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck NC, Houge LR, Fraps C, Perry C, Fenstemaker L. Patient diagnostic, behavioral and demographic variables associated with changes in civil commitment procedures. J Clin Psychol. 1984;40:364–371. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198401)40:1<364::aid-jclp2270400168>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blank K, Vingiano W, Schwartz HI. Psychiatric commitment of the elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1989;2:140–144. doi: 10.1177/089198878900200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonsack C, Borgeat F. Perceived coercion and need for hospitalization related to psychiatric admission. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2005;28:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruns G. Zwangseinweisungspatienten-eine psychiatrische risikogruppe. Nervenarzt. 1991;62:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnett R, Mallett R, Bhugra D, Hutchinson G, Der G, Leff J. The first contact of patients with schizophrenia with psychiatric services: social factors and pathways to care in a multi-ethnic population. Psychol Med. 1999;29:475–483. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casella CB, Loch AA. Religious affiliation as a predictor of involuntary psychiatric admission: a brazilian 1-year follow-up study. Front. 2014;2:102. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang TM, Ferreira LK, Ferreira MP, Hirata ES. Clinical and demographic differences between voluntary and involuntary psychiatric admissions in a university hospital in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29:2347–2352. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00041313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiang CL, Chen PC, Huang LY. Time trends in first admission rates for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in Taiwan, 1998–2007: a 10-year population-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole E, Leavey G, King M, Johnson-Sabine E, Hoar A. Pathways to care for patients with a first episode of psychosis: a comparison of ethnic groups. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167:770–776. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.6.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cougnard A, Kalmi E, Desage A. Factors influencing compulsory admission in first-admitted subjects with psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:804–809. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Craw J, Compton MT. Characteristics associated with involuntary versus voluntary legal status at admission and discharge among psychiatric inpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:981–988. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crisanti AS, Love EJ. Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients detained under civil commitment legislation: a Canadian study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2001;24:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(01)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Girolamo G, Rucci P, Gaddini A, Picardi A, Santone G. Compulsory admissions in Italy: results of a national survey. Int J Mental Health. 2009;37:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delayahu Y, Nehama Y, Sagi A, Baruch Y, Blass DM. Evaluating the clinical impact of involuntary admission to a specialized dual diagnosis ward. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2014;51:290–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Lorenzo R, Vecchi L, Artoni C, Mongelli F, Ferri P. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients involuntarily hospitalized in an Italian psychiatric ward: a 1-year retrospective analysis. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:17–28. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i6-S.7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donisi V, Tedeschi F, Salazzari D, Amaddeo F. Differences in the use of involuntary admission across the Veneto region: which role for individual and contextual variables? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25:49–57. doi: 10.1017/S2045796014000663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emons B, Haussleiter IS, Kalthoff J. Impact of social-psychiatric services and psychiatric clinics on involuntary admissions. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:672–680. doi: 10.1177/0020764013511794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eytan A, Chatton A, Safran E, Khazaal Y. Impact of psychiatrists' qualifications on the rate of compulsory admissions. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fok ML, Stewart R, Hayes RD, Moran P. The impact of co-morbid personality disorder on use of psychiatric services and involuntary hospitalization in people with severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1631–1640. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0874-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Folnegovic-Smalc V, Uzun S, Ljubin T. Sex-specific characteristics of involuntary hospitalization in Croatia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2000;54:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaddini A, Biscaglia L, Bracco R. A one-day census of acute psychiatric inpatient facilities in Italy: findings from the PROGRES-acute project. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:722–724. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia Cabeza I, Rojano Capilla P, Arango Lopez C, Sanz Amador M, Calcedo Ordonez A. Internamiento psiquiatrico contra la voluntad previo expediente y de urgencia (a proposito de una encuesta) An Psiquiatr. 1998;14:301–306. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gou L, Zhou J-S, Xiang Y-T. Frequency of involuntary admissions and its associations with demographic and clinical characteristics in China. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gultekin BK, CelIk S, Tihan A, Beskardes AF, Sezer U. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of involuntary and voluntary hospitalized psychiatric inpatients in a mental health hospital. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2013;50:216–221. doi: 10.4274/npa.y6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansson L, Muus S, Saarento O. The Nordic comparative study on sectorized psychiatry: rates of compulsory care and use of compulsory admissions during a 1-year follow-up. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:99–104. doi: 10.1007/s001270050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hatling T, Krogen T, Ulleberg P. Compulsory admissions to psychiatric hospitais in Norway: international comparisons and regional variations. J Ment Health. 2002;11:623–634. [Google Scholar]