Abstract

BACKGROUND

Neuroendocrine neoplasms are rarely located in the gallbladder (GB), and carcinoid syndrome is exceedingly rare in patients with GB neuroendocrine neoplasms.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a case of GB neuroendocrine carcinoma (GB-NEC) in a 65-year-old man, who presented with flushing for 2 mo. Pathological specimens of the flushed skin revealed that mucin was deposited between the collagen bundles in the dermis. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging indicated neoplasm in the GB with liver invasion and enlarged lymph nodes in the portacaval space. High fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was detected in lymph nodes in the portacaval space, but distant metastasis was not seen by positron emission tomography. Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of the GB neoplasm was suggestive of high-grade NEC. Because of the functional characteristics of poorly differentiated NEC, en bloc cholecystectomy, resection of hepatic segments IVb and V, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. A diagnosis of poorly differentiated NEC was made by pathological findings and immunohistochemical staining data. Ki-67 index was > 80%. The patient refused adjuvant therapy and passed away in the 7th month.

CONCLUSION

Distinctive manifestation combined with imaging helps make correct preoperative diagnosis. Radical surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy might improve prognosis.

Keywords: Malignant carcinoid syndrome, Neuroendocrine tumors, Carcinoma, Gallbladder, Carcinoid tumor, Case report

Core tip: Neuroendocrine neoplasms are rarely located in the gallbladder (GB), and carcinoid syndrome is exceedingly rare in patients with GB neuroendocrine neoplasms. We present herein, a rare case of GB neuroendocrine carcinoma in a 65-year-old man, who presented with flushing for 2 mo. En bloc cholecystectomy, resection of hepatic segments IVb and V, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and regional lymphadenectomy were performed. Surgery helped to alleviate his symptoms. Distinctive manifestation combined with imaging helps make correct preoperative diagnosis. Radical surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy might improve the prognosis of advanced GB neuroendocrine carcinomas.

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) refer to a family of neoplasms originating from neuroendocrine cells throughout the body, mostly originating in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and lungs[1,2]. Neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) always refers to high-grade neoplasms with poor differentiation. NENs are traditionally divided into functional and nonfunctional neoplasms. Functional NENs produce peptide hormones that cause symptoms, while nonfunctional NENs are clinically silent until neoplasm is large, metastatic disease or bleeding occurs. Primary gallbladder (GB)-NENs are infrequent and make up < 1% of all NENs[1,3]. Among 875 GB carcinomas diagnosed by ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology, only 20 were GB-NENs[4]. In addition, among GB-NENs, carcinoid syndrome caused by functional neoplasm is exceedingly rare (< 1%)[5,6].

Here, we report a case of functional GB-NEC, in which an initial presentation of the patient was suspected as manifestation of carcinoid syndrome. The patient underwent radical surgery that helped to alleviate his symptoms. In addition, we reviewed cases of functional GB-NENs associated with rare manifestations reported from 1986 to 2018.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 65-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a history of flushing for 2 mo. The patient had no symptoms of abdominal pain, diarrhea, or jaundice.

History of present illness

Patient’s symptoms started 2 mo ago.

History of past illness

The patient denied a history of hypertension, diabetes, and other relevant illness.

Family history

His father had esophageal cancer.

Physical examination

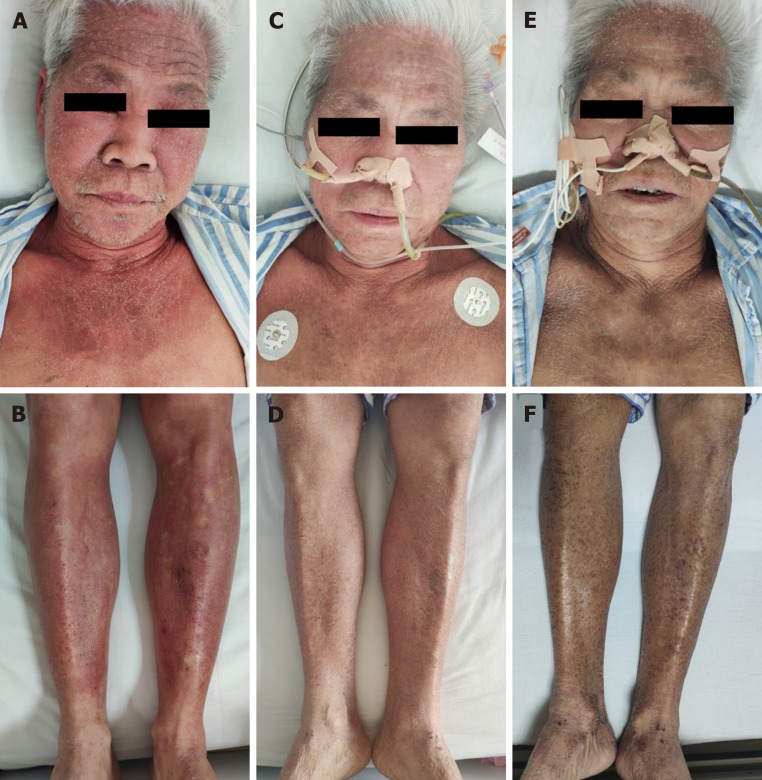

The physical examination was normal except for the skin. The skin over the face, neck, upper chest, and limbs was flushed and scaly (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Visible changes of the skin. A, B: The skin over the face, neck, upper chest, and limbs was flushed, accompanied by desquamation before surgery; C, D: Flushing was obviously relieved on day 5 postoperatively; E, F: At 2 wk after surgery, flushing faded entirely and skin pigmentation was visible.

Laboratory examinations

Complete blood count, renal and liver function tests, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within normal limits. Autoimmune serology showed an increased antinuclear antibody titer (1:40), but antibodies to double-stranded DNA, ribonucleoprotein, Sm nuclear antigen, scleroderma-70 protein, and Jo-1 protein were negative. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) was 34.7 ng/mL (normal range 0–30.0 ng/mL). Levels of tumor markers including α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 125, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were in the normal ranges.

Imaging examinations

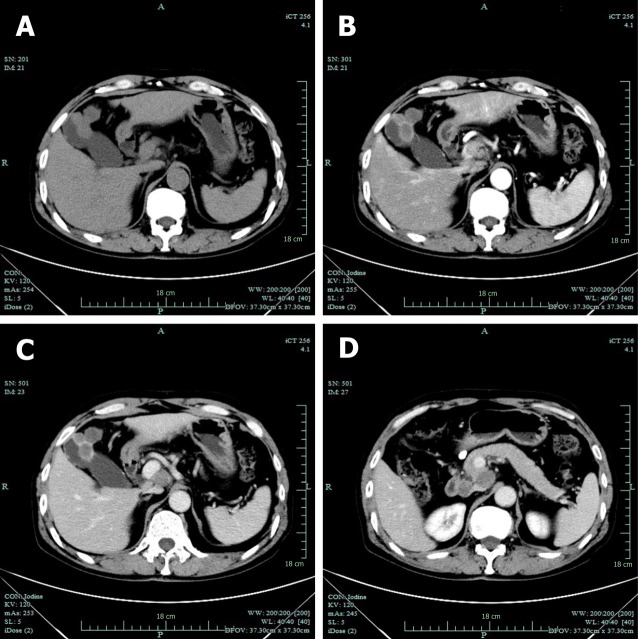

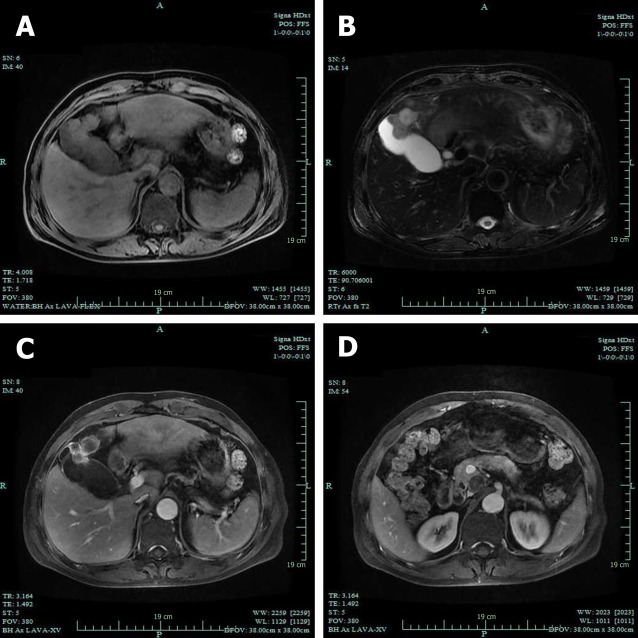

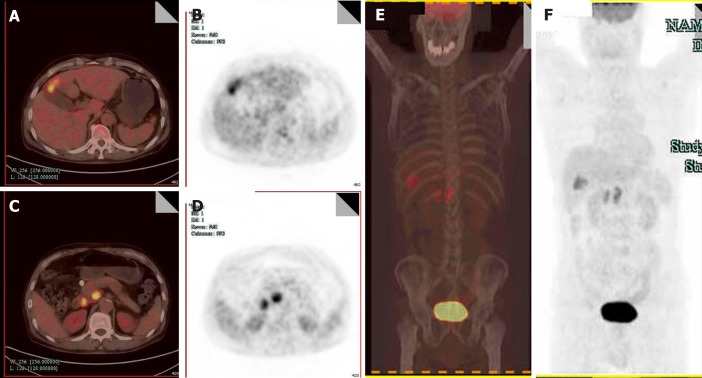

Computed tomography (CT) revealed GB neoplasm and enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed GB neoplasm with liver invasion, and several enlarged lymph nodes were found in the portacaval space (Figure 3). High fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was detected in lymph nodes in the portacaval space, which was considered metastasis, but distant metastasis was not seen by positron emission tomography (PET) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography examination. A: Gallbladder neoplasm was visible in unenhanced imagery; B: Gallbladder neoplasm was mildly enhanced in arterial phases; C: Gallbladder neoplasm was mildly enhanced in venous phases; D: Enlarged lymph nodes were seen in the portacaval space.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging examination. A: The gallbladder neoplasm was revealed with liver invasion on T1-weighted imaging; B: The gallbladder neoplasm was revealed with liver invasion on T2-weighted imaging; C: The neoplasm showed increased signals in contrast-enhanced phase; D: Several enlarged lymph nodes were found in the portacaval space.

Figure 4.

Positron emission tomography examination. A, B: Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was higher in the gallbladder; C, D: Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was higher in lymph nodes in the portacaval space; E, F: Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake did not significantly increase in other tissue.

Further diagnostic work-up

Pathological specimens of the flushed skin revealed that mucin was deposited between the collagen bundles in the dermis. Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy from the GB neoplasm was suggestive of high-grade NEC. Immunohistochemical staining of the biopsy specimen revealed expression of chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin (SYN), pan-cytokeratin (pan-CK), CK19, and cluster of differentiation (CD) 56.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis was GB-NEC due to pathology and immunohistochemistry of the biopsy specimen.

TREATMENT

Intraoperative exploration showed that two lymph nodes in the portacaval space were firm and immovable, which adhered to the pancreas and duodenum respectively, and therefore could not be harvested completely. En bloc cholecystectomy, resection of hepatic segments IVb and V, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and regional lymphadenectomy were performed.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Intraoperative blood loss volume was approximately 300 mL. Operative time was 6 h and 35 min. No adverse events occurred in the postoperative period. And postoperative hospitalization duration was 1 mo.

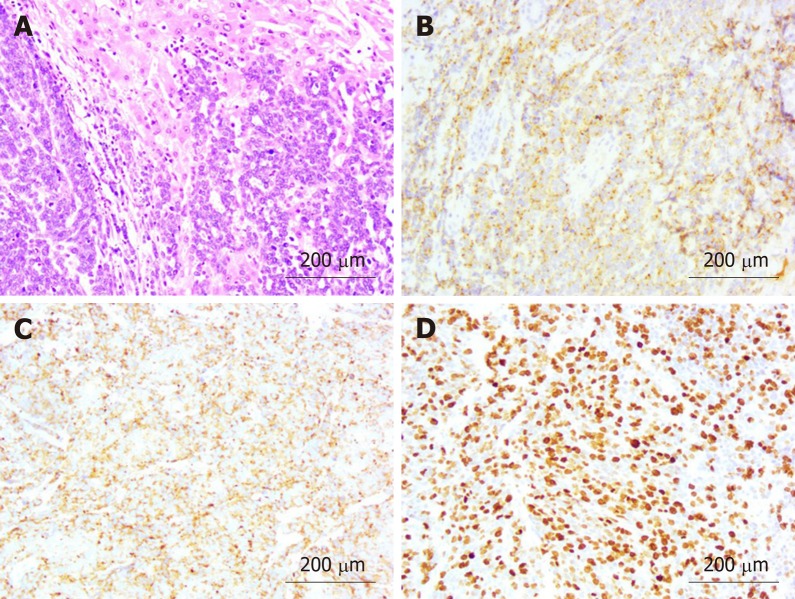

Pathological findings were poorly differentiated NEC with adjacent liver invasion (Figure 5A), pancreatic invasion, and duodenal invasion. Vascular cancer embolus was revealed. No lymph node metastasis was revealed in six peripancreatic lymph nodes and eight perigastric lymph nodes. The neoplasm measured 4.0 cm × 2.0 cm and was located in the neck of GB. Immunohistochemical staining showed expression of CgA (Figure 5B), SYN (Figure 5C), pan-CK, CK19, and CD56. Thyroid transcription factor-1 was detected in a few cells. The GB-NEC was negative for CK7 and glypican-3. Ki-67 index was > 80% (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Pathological examination and immunohistochemical staining (20 ×). A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed poorly differentiated gallbladder neuroendocrine carcinoma with liver invasion; B: Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of chromogranin A; C: Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive expression of synaptophysin; D: Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the Ki-67 index was > 80%.

The level of NSE decreased to 12.6 ng/mL 2 d after surgery. Flushing was obviously relieved at day 5 postoperatively (Figure 1C and D), and 2 wk after surgery, flushing faded entirely and skin pigmentation was visible (Figure 1E and F). The patient refused adjuvant therapy, such as chemotherapy. On telephonic follow-up, the son stated that the skin became flushed in the 3rd month after surgery and the patient passed away in the 7th month.

DISCUSSION

GB-NENs account for a particularly small group of NENs. According to a survey by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result program, the incidence of GB-NEN was < 0.74/100000 between 1973 and 2005, accounting for 0.5% of all NENs[7]. Compared to GB adenocarcinomas, GB-NEC has a tendency of advanced disease progression at diagnosis, poor differentiation of cells and high rate of lymphatic metastases[8].

Functional NENs might cause symptoms due to peptide hormones. Typical symptoms of carcinoid syndrome are flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, and edema. Nevertheless, the most common symptom of GB-NENs is epigastric pain. Lack of distinctive manifestations adds to the difficulty of making correct diagnosis preoperatively[9]. In addition, because of the lack of early-stage symptoms and aggressiveness of the carcinoma, GB-NECs are often diagnosed at an advanced stage with adjacent liver invasion and lymph node metastasis, resulting in poor prognosis[5,10]. The classification and grading criteria for GB-NENs correlates with Ki-67 index and mitotic rate. According to the 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system[11], our patient had high-grade and poorly differentiated NEC, because Ki-67 index was > 80% and the carcinoma was small-cell type. According to the Eighth Edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, the NEC in our case report is classified as T4N0M0.

The clinicopathological features and follow-up results of the reported GB-NENs associated with rare manifestations, including the present case, are described in Table 1[12-17]. The patient age ranged from 52 to 79 years (mean: 65 years). There were no significant gender-related differences. Patients had various symptoms, such as flushing (cases 1 and 6), wheezing (case 1), Cushing’s syndrome (cases 2 and 3), hypoglycemia (case 4), and watery diarrhea (case 5). GB-NEN can arise in any part of GB. Immunohistochemically, cases 1, 2, 4, and 6 presented with intense immunoreactivity for chromogranin and SYN, while cases 1, 4, and 6 presented with intense immunoreactivity for CD56.

Table 1.

Patient details, neoplasm localization, pathology, treatment, and follow-up of reported functional gallbladder neuroendocrine neoplasms

| Case | Ref. | Age in yr, sex | Presentation | Physical examination | Primary site | Pathology | Treatment | Follow-up |

| 1 | Monier et al[12] | 60, M | Epigastric pain, jaundice, flushing, cough, wheezing | NA | fundus of GB | Size: NA; PI: ~ 60%; IHC: Chromogranin A (+), synaptophysin (+), CD56 (+), CK7 (+), polyclonal carcinoembr-yonic antigen (+), Caudal-type homeobox transcription factor 2 (+), S-100 (−), CK20 (−), CD10 (−), CK19 (−), prostate-specific antigen (−),thyroid transcription factor-1 (−), HepParl (−) | NA | NA |

| 2 | Lin et al[13] | 65, F | 3 mo progressive generalized weakness and anorexia | Proximal muscle weakness, hirsutism, moon face, buffalo hump | Body of GB | Size: NA; PI: NA; IHC: Chromogranin (+), synaptophysin (+), adrenocortico-tropic hormone -stain (+) | Cholecystect-omy and wedge-shaped liver resection | Hepatic metastasis 2 mo after surgery |

| 3 | Howlett et al[14] and Coates et al[15] | 68, F | NA | Cushing’s syndrome | GB | Size: NA; PI: NA; IHC: Neuron specific enolase immunostain-ing (+) | NA | Survived for 1 mo following presentation |

| 4 | Ahn et al[16] | 52, F | Episodic hypoglycemia of 10 mo duration | NA | GB | Size: 10.3 cm × 7 cm × 5.3 cm; PI: NA; IHC: CD56 (+), chromogranin (+), synaptophysin (+), immunochem-ical staining for insulin (+) | Hepatic segmentectomy, cholecystecto-my, pancreaticosp-lenectomy | NA |

| 5 | Salimi et al[17] | 79, M | Watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weakness for several weeks | NA | GB | Size: 0.5 cm in thickness and 1.5 cm in diameter; PI: NA; IHC: Neuron specific enolase immunostain-ing (+), chromogranin (+) | NA | The patient died on his 3rd day of hospitalization from multiple organ failure |

| 6 | Present case | 65, M | A history of flushing for 2 mo | The skin over face, neck, upper chest and limbs flushed and was scaly | neck of GB | Size: 4.0 cm × 2.0 cm; PI: Ki-67 (80%+++); IHC: Chromogranin A (+), synaptophysin (+), pan-CK (+), CK19 (+), CD56 (+), thyroid transcription factor-1 (a few +), CK7 (−), glypican-3 (−) | En bloc cholecystect-omy, resection of hepatic segment IVb and V, Whipple and regional lymphadenec-tomy were performed | The skin became flushed in 3rd month after surgery and the patient passed away in 7th month |

M: Male; F: Female; NA: Not available; GB: Gallbladder; PI: Proliferation index; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; CD: Cluster of differentiation; CK: Cytokeratin.

Imaging examinations including ultrasonography, CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and PET can indicate GB neoplasm. According to an article that compared CT features between GB-NEN and GB adenocarcinoma, the former showed well-defined margins and had larger hepatic and lymph node metastasis than adenocarcinomas[18]. One recent study found that primary small cell GB-NENs mainly presented as a large, heterogeneous GB neoplasm with extraluminal growth[19]. The GB-NEC in our case manifested as a large neoplasm with hepatic and lymph node metastasis, in accordance with the above findings. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT plays an important role in defining aggressiveness of high-grade gastro-entero-pancreatic NENs and providing with prognostic information, especially when combined with 68Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues PET/CT[20]. High sensitivity has been proved for PET/CT with 68Ga-labeled peptides in patients with suspected NENs[21,22]. The utility of Gallium-68-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N″,N‴-tetra acetic acid-D-Phe1-Tyr3-octreotate (68Ga-DOTATATE) PET/CT has been discussed recently, which gives relevant information for accurate staging of gastro-entero-pancreatic NENs and selection of appropriate treatment intervention[23]. Gallium-68-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N'',N'''-tetra acetic acid-D-Phe1-Try3-octreotide (68Ga-DOTATOC) PET/CT is reported as an effective tool in the localization of unknown primary NENs[24,25].

GB-NEN is often misdiagnosed preoperatively, and most GB-NENs are discovered by pathology and immunohistochemistry[26-28]. In order to make a definite diagnosis preoperatively and selection of appropriate treatment intervention, percutaneous biopsy can be performed to assess GB neoplasm[29-31]. In 75% of NENs, neoplasm can stain positive for SYN, followed by CgA.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for Hepatobiliary Cancer (Version 4. 2019), if GB-NEC is restricted to the lamina propria, a simple cholecystectomy is adequate. However, for patients with T2 or higher carcinoma, cholecystectomy combined with hepatic resection and lymphadenectomy can improve survival. The increased survival rate has been realized for locally invasive GB-NECs based on radical surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy[32]. In some cases, in which the neoplasm is unresectable or specimen margins have neoplasm involvement, systemic chemotherapy can be the treatment intervention[2]. Adjuvant therapy is based on dissemination state, resection margin and histological classification. However, for biliary NEN there are no consensual indications for adjuvant therapy[33]. Gemcitabine-based and fluoropyrimidine-based combination chemotherapy regimens are recommended for the treatment of patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. The role of radiotherapy is unclear. Radiotherapy might be useful for local control and palliation of pain from metastatic bone disease, but NENs are generally not sensitive to traditional radiotherapy[34,35]. The effectiveness of biotherapy (like SST analogs) has been demonstrated in controlling symptoms in some gastro-entero-pancreatic NENs, such as SST-receptor-positive inoperable gastro-entero-pancreatic NEN[36]. In the present case, the patient refused adjuvant therapy and survived for 7 mo after surgery. Maybe chemotherapy would have inhibited the recurrence and done some good to the patient’s survival period.

Our case report had several limitations. First, we did not determine levels of serum CgA, serum serotonin and urinary 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid preoperatively. So we could not diagnosis the patient’s disease as carcinoid syndrome[37]. However, the patient’s symptom was of 2 mo duration and was obviously relieved at day 5 postoperatively. In addition, we ruled out immunological disease and dermatosis by the examination of antinuclear antibody titer, antibodies to double-stranded DNA, ribonucleoprotein, Sm nuclear antigen, scleroderma-70 protein, Jo-1 protein and pathological finding of the flushed skin. Therefore, his disease was suspected as carcinoid syndrome. Second, our case report lacked intra-operatory images and photographs of the resected neoplasm. We provided the size of the neoplasm and location to make up for this limitation.

CONCLUSION

In most cases, the symptoms of patients with GB-NEN are not distinctive, but it should be kept in mind that a few patients present with carcinoid syndrome. Distinctive manifestation combined with imaging helps to make correct preoperative diagnosis. Percutaneous biopsy can be an option to identify the neoplasm characteristics. Radical surgery including cholecystectomy and hepatic resection combined with regional lymphadenectomy plus adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for advanced GB-NEC. Further studies on chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and biotherapy are needed for the standardization of treatment intervention including surgery.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Peer-review started: September 21, 2019

First decision: November 4, 2019

Article in press: January 11, 2020

P-Reviewer: Aosasa S, Iliescu EL, Yang ZH S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Zhang YL

Contributor Information

Ming Jin, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Bo Zhou, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Xiong-Ling Jiang, Department of Pathology, First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China.

Qi-Yi Zhang, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Xiang Zheng, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Yuan-Cong Jiang, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China.

Sheng Yan, Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China. shengyan@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zheng Z, Chen C, Li B, Liu H, Zhou L, Zhang H, Zheng C, He X, Liu W, Hong T, Zhao Y. Biliary Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Clinical Profiles, Management, and Analysis of Prognostic Factors. Front Oncol. 2019;9:38. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, Shen YY, Ni XZ. Two cases of neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11916–11920. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You YH, Choi DW, Heo JS, Han IW, Choi SH, Jang KT, Han S. Can surgical treatment be justified for neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder? Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14886. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yadav R, Jain D, Mathur SR, Iyer VK. Cytomorphology of neuroendocrine tumours of the gallbladder. Cytopathology. 2016;27:97–102. doi: 10.1111/cyt.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eltawil KM, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Modlin IM. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: an evaluation and reassessment of management strategy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:687–695. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d7a6d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W, Chen W, Chen J, Hong T, Li B, Qu Q, He X. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of gallbladder: a case series and literature review. Eur J Med Res. 2019;24:8. doi: 10.1186/s40001-019-0363-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayub F, Saif MW. Neuroendocrine Tumor of the Cystic Duct: A Rare and Incidental Diagnosis. Cureus. 2017;9:e1755. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Wang L, Liu X, Zhang G, Zhao Y, Geng Z. Gallbladder neuroendocrine carcinoma: report of 10 cases and comparision of clinicopathologic features with gallbladder adenocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:8218–8226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou YP, Li WM, Liu HR, Li N. Primary carcinoid tumor of the gallbladder: a case report and brief review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Hossain S, Henson DE, Schwartz AM. Carcinoid tumors and small-cell carcinomas of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts: a comparative study based on 221 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2009;13:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182–188. doi: 10.1111/his.13975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monier A, Saloum N, Szmigielski W, Alrashid A, Napaki SM. Neuroendocrine tumor of the gallbladder. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:228–231. doi: 10.12659/PJR.893705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin D, Suwantarat N, Kwee S, Miyashiro M. Cushing's syndrome caused by an ACTH-producing large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:56–58. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howlett TA, Drury PL, Perry L, Doniach I, Rees LH, Besser GM. Diagnosis and management of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome: comparison of the features in ectopic and pituitary ACTH production. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1986;24:699–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1986.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coates PJ, Doniach I, Howlett TA, Rees LH, Besser GM. Immunocytochemical study of 18 tumours causing ectopic Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:955–960. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.9.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn JE, Byun JH, Ko MS, Park SH, Lee MG. Case report: neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder causing hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salimi Z, Sharafuddin M. Ultrasound appearance of primary carcinoid tumor of the gallbladder associated with carcinoid syndrome. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:435–437. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TH, Kim SH, Lee KB, Han JK. Outcome and CT differentiation of gallbladder neuroendocrine tumours from adenocarcinomas. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faraoun SA, Guerrache Y, Dautry R, Boudiaf M, Dohan A, Barral M, Hoeffel C, Rousset P, Fohlen A, Soyer P. Computed Tomographic Features of Primary Small Cell Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Gallbladder. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2018;42:707–713. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carideo L, Prosperi D, Panzuto F, Magi L, Pratesi MS, Rinzivillo M, Annibale B, Signore A. Role of Combined [68Ga] Ga-DOTA-SST Analogues and [18F] FDG PET/CT in the Management of GEP-NENs: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2019:8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8071032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampaio Vieira T, Borges Faria D, Souto Moura C, Francisco E, Barroso S, Pereira de Oliveira J. Incidental finding of a breast carcinoma on Ga-68-DOTA-1-Nal3-octreotide positron emission tomography/computed tomography performed for the evaluation of a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11878. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deppen SA, Liu E, Blume JD, Clanton J, Shi C, Jones-Jackson LB, Lakhani V, Baum RP, Berlin J, Smith GT, Graham M, Sandler MP, Delbeke D, Walker RC. Safety and Efficacy of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for Diagnosis, Staging, and Treatment Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:708–714. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.163865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadowski SM, Neychev V, Millo C, Shih J, Nilubol N, Herscovitch P, Pacak K, Marx SJ, Kebebew E. Prospective Study of 68Ga-DOTATATE Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography for Detecting Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Unknown Primary Sites. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:588–596. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menda Y, O'Dorisio TM, Howe JR, Schultz M, Dillon JS, Dick D, Watkins GL, Ginader T, Bushnell DL, Sunderland JJ, Zamba GKD, Graham M, O'Dorisio MS. Localization of Unknown Primary Site with 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1054–1057. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.180984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cingarlini S, Ortolani S, Salgarello M, Butturini G, Malpaga A, Malfatti V, DʼOnofrio M, Davì MV, Vallerio P, Ruzzenente A, Capelli P, Citton E, Grego E, Trentin C, De Robertis R, Scarpa A, Bassi C, Tortora G. Role of Combined 68Ga-DOTATOC and 18F-FDG Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in the Diagnostic Workup of Pancreas Neuroendocrine Tumors: Implications for Managing Surgical Decisions. Pancreas. 2017;46:42–47. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose Y, Sakata J, Endo K, Takahashi M, Saito R, Imano H, Kido T, Yoshino K, Sasaki T, Wakai T. A 0.8-cm clear cell neuroendocrine tumor G1 of the gallbladder with lymph node metastasis: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:150. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du H, Zhang H, Xu Y, Wang L. Neuroendocrine tumor of the gallbladder with spectral CT. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2014;4:516–518. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2014.08.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujii M, Saito H, Shiode J. Rare case of a gallbladder neuroendocrine carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019;12:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s12328-018-0883-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jun SR, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gallbladder and bile duct: Report of four cases with pathological correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:604–609. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200607000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Fattach H, Guerrache Y, Eveno C, Pocard M, Kaci R, Shaar-Chneker C, Dautry R, Boudiaf M, Dohan A, Soyer P. Primary neuroendocrine tumors of the gallbladder: Ultrasonographic and MDCT features with pathologic correlation. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96:499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chakraborty PS, Dhull VS, Karunanithi S, Roy SG, Kumar R. Rare case of gall bladder neuroendocrine tumor: 18F-FDG and 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT findings. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2014;33:316–317. doi: 10.1016/j.remn.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moskal TL, Zhang PJ, Nava HR. Small cell carcinoma of the gallbladder. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:54–59. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199901)70:1<54::aid-jso10>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Lee WJ, Lee SH, Lee KB, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Kim SW, Yoon YB, Hwang JH, Han HS, Woo SM, Park SJ. Clinical features of 20 patients with curatively resected biliary neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimono C, Suwa K, Sato M, Shirai S, Yamada K, Nakamura Y, Makuuchi M. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder: long survival achieved by multimodal treatment. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:351–355. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Drozdov I, Siddique ZL, Gustafsson BI. Pharmacotherapy of neuroendocrine cancers. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2617–2626. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.15.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikou GC, Lygidakis NJ, Toubanakis C, Pavlatos S, Tseleni-Balafouta S, Giannatou E, Mallas E, Safioleas M. Current diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal carcinoids in a series of 101 patients: the significance of serum chromogranin-A, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and somatostatin analogues. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:731–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boutzios G, Kaltsas G. Clinical Syndromes Related to Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Front Horm Res. 2015;44:40–57. doi: 10.1159/000382053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]