Abstract

Background:

Previously published work established the need for a specialty-specific definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. That work established a composite definition consisting of 11 domains and their component “defining themes” for professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. As a next step towards assessing generalizability of our single-center findings, we sought to gain input from a national sample of pediatric anesthesiologists.

Aim:

To establish the construct validity of our previously published multidimensional definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology using a nationally representative sample of pediatric anesthesiologists.

Methods:

A survey was distributed via snowball sampling to the leaders of every pediatric anesthesiology fellowship program and pediatric anesthesia department or clinical division in the United States. Survey items were designed to validate individual component themes in the working definition. For affirmed items, the respondent was asked to rate the importance of the item. Respondents were also invited to suggest novel themes to be included in the definition.

Results:

216 pediatric anesthesiologists representing a variety of experience levels and practice settings responded to the survey. All 40 themes were strongly supported by the respondents, with the least supported theme receiving 71.6% approval. 92.8% of respondents indicated that the 11 domains previously identified formed a comprehensive list of domains for professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. Four additional novel themes were suggested by respondents, including wellness/self-care/burnout prevention, political advocacy, justice within a practice organization, and respect for leadership/experienced partners. These are topics for future study. The survey responses also indicated a near-universal agreement that didactic lectures would be ineffective for teaching professionalism.

Conclusion:

This national survey of pediatric anesthesiologists serves to confirm the construct validity of our prior working definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology, and has uncovered several opportunities for further study. This definition can be used for both curriculum and policy development within the specialty.

Keywords: Anesthesiology [H02.403.066]; Pediatrics [H02.403.670]; Education, Medical, Graduate [I02.358.399.350]; Education, Medical, Continuing [102.358.212.350], [102.358.399.250]; Professionalism [N05.350.340.581]; Surveys and Questionnaires [N05.715.360.300.800]

Introduction

Describing the many components of “professionalism” in anesthesiology1, as well as determining a specific definition for the field of pediatric anesthesiology, is an essential and challenging task. Previously published work2 reviewed, in detail, both the need for precise, specialty-specific definitions and the absence of such a definition for pediatric anesthesiology. The conclusion of that work was a composite definition consisting of 11 domains and their component “defining themes” for professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology.

Recently, Cullen et al worked to identify, and rank by importance, unprofessional behaviors using checklists.3 The authors have suggested that by employing their checklists, medical students and residents displaying professionalism concerns could be identified and remediated early. However, Riveros et al concluded that, among anesthesiology residents, multisource feedback and standardized education changed trainee awareness of professionalism standards and performance self-assessment scores, and did not have impact on external evaluations by families, faculty, or other residents.4 These studies have reinforced the need for both a clear, specialty-specific definition of professionalism as well as tools for evaluating and teaching professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology.

In an editorial accompanying publication of our original study, Martin implored, and we agree, that our single-center findings must be broadened to include the community at large in order to “serve as the basis for a new educational curriculum for faculty and trainees.”5 As a next step towards affirming the generalizability of our single-center findings, we sought to gain input from a national sample of pediatric anesthesiologists. The aim of the present study was to establish the construct validity of our previously published multi-dimensional definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. Specifically, we describe using survey data from a more generalizable sample to support or dispute whether the domains and items generated in the prior manuscript were reflective and inclusive of a shared understanding of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. Our underlying goal remains the creation of a reflective, case-based curriculum for teaching and discussing professionalism to pediatric anesthesiology fellows, faculty members, and practitioners.

Methods

The study was conducted between December 2016 and January 2017 using an electronically-distributed survey. The survey was built and data were stored using a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture - a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing an intuitive interface for validated data entry and audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures) database housed at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.6 Survey items described 40 component items across 11 domains resulting from the formative qualitative study.2 The electronic survey consisted of three parts: theme-testing, domain-affirmation, and demographics.

For the theme-testing section of the survey, we sought to validate the 40 individual component themes making up our working definition of pediatric anesthesiology professionalism. Using the raw data from our previous work, we generated a single survey item for each component theme through a consensus process among study team members with expertise in pediatric anesthesia, graduate medical education, and mixed methodologies. The survey items were designed to describe the underlying theme in enough detail that inter-respondent variability arising from item definition confusion would be minimized. The full electronic survey (in static form) is available in an online supplement as Figure S1: Survey Tool for Professionalism in Pediatric Anesthesiology.

For each of the 40 theme-based survey items, the respondent was first asked for a binary “yes” or “no” response to the prompt “Please answer YES for all items that should be included in the definition of ‘Professionalism in Pediatric Anesthesiology,’ even if you believe the relative importance of a given item to be low.” For items that received a “no” response, no further questions about that item were offered. In contrast, for items receiving a “yes” response, the respondent was then asked to identify the importance of the item in the definition (i.e., importance ranking), by placing a single mark at the location of importance on a continuous sliding scale with a left-sided anchor of “Irrelevant” and a right-sided anchor of “Essential.”

At the conclusion of the theme-testing section of the survey, respondents were asked to identify any items relevant to the definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology that were not previously described in order to identify items not suggested by our original sample and to increase generalizability. Respondents who identified such an item were given an opportunity to rate the importance of the new item via the same sliding scale and anchors. Additionally, the electronic survey was programmed to repeatedly generate another opportunity for creating and rating new items using the same format and importance ranking scale to allow for as many new items as necessary to saturate the exploration of uncovered items.

The domain-affirmation section of the survey asked respondents to review the list of 11 domains (describing the 40 items) identified in our working definition of professionalism for pediatric anesthesiology. Respondents were then asked for a binary “yes” or “no” response to the prompt, “Do you believe this is a comprehensive list of major domains for Professionalism in Pediatric Anesthesiology?” Respondents who answered “no” to this question were given the opportunity to add any missing domains in a text field. Finally, all respondents were asked to enter any additional comments or answer clarifications in a comments field.

The demographic section of the survey included items characterizing respondents’ duration of practice, frequency of work with anesthesiology trainees, prior professionalism education, and beliefs about optimal methods for teaching professionalism.

The electronic survey was distributed to a nationwide group of pediatric anesthesiologists via a snowball sampling mechanism. Snowball sampling is a nonprobability sampling method whereby research participants help to identify additional potential participants.7 The lead investigator sent an email request for survey participation, as well as an electronic survey link, to each of the pediatric anesthesiology fellowship Program Directors in the US (through the Pediatric Anesthesiology Program Directors’ Association (PAPDA)). Each Program Director was asked to forward the survey to their faculty as well as any other potentially interested pediatric anesthesiologists. The lead investigator also initiated a similar snowball sampling mechanism through an email list of Division Chiefs or Department Chairs for pediatric anesthesiology private practices or academic departments in the US (through the Pediatric Anesthesia Leadership Council (PALC)). The described distribution mode precluded an accurate awareness of the full denominator of respondents – and hence a response rate; however, a sample of participants with diverse backgrounds and from different practice settings across the country can be expected.7

Data were analyzed using SigmaPlot 13.0 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Professionalism theme rates of affirmative answers to the binary question about importance were reported as simple percentages and grouped by domains (as previously reported).2 For qualitative sliding scale responses (i.e. importance rankings), values were linearly scaled from 0 (i.e. irrelevant) to 100 (i.e. essential) based on automated computer analysis of the physical position of the slider for each response. Median, interquartile range, and 10th and 90th percentile answers were calculated.

Results

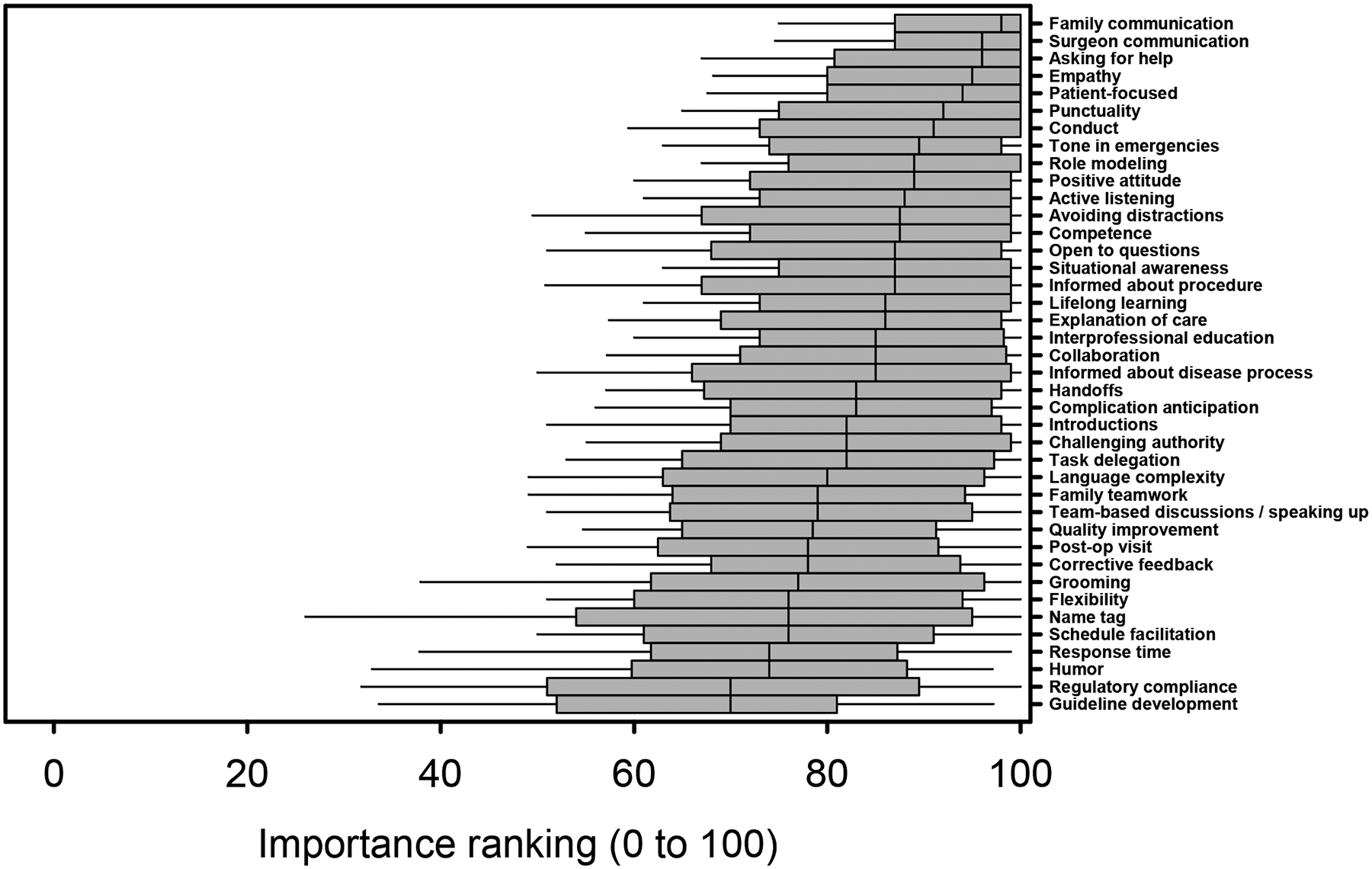

A total of 216 pediatric anesthesiologists responded to the survey. Results of the professionalism theme-based survey questions are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Notably, each of the 40 themes was supported by the respondents. The least supported theme, “Developing clinical guidelines / Working to change care within the practice (or nationally) through guideline development,” still received a positive response to the binary question about inclusion in the definition from 71.6% of respondents (Table 1). Figure 1 shows the aggregated sliding scale importance ranking responses, ranked by decreasing median scores; the majority of participants marked each one of the 40 items as closer to “essential” than “irrelevant” on the sliding scale.

Table 1.

Theme Inclusion (affirmative) responses, grouped by domain. For full descriptions/definitions of these themes, please see Lockman JL, Schwartz AJ, Cronholm PF: Working to define professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology: a qualitative study of domains of the expert pediatric anesthesiologist as valued by interdisciplinary stakeholders. Pediatric Anesthesia 27(2): 137–146, February 2017.

| Theme | Affirmation (%) | Theme | Affirmation (%) | Theme | Affirmation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-focused | 98.4 | Family Communication | 99.5 | Role Modeling | 98.8 |

| Handoffs | 94.2 | Surgeon Communication | 98.9 | Tone in emergencies | 96.1 |

| Post-op Visit | 94.2 | Language Complexity | 91.6 | Flexibility | 90.5 |

| Informed about Procedure | 83.6 | Task Delegation | 86.4 | ||

| Informed about Disease Process | 82.1 | Situational Awareness | 93.3 | ||

| Complication Anticipation | 87.6 | Collaboration | 96.4 | ||

| Lifelong Learning | 93.7 | Schedule Facilitation | 77.5 | Family Teamwork | 94.7 |

| Regulatory Compliance | 89.5 | Asking for Help | 94.7 | ||

| Competence | 86.4 | Corrective Feedback | 94.2 | Challenging Authority | 94.1 |

| Interprofessional Education | 89.0 | ||||

| Active Listening | 98.3 | Quality Improvement | 88.9 | Team-based Discussions / Speaking Up | 97.2 |

| Open to Questions | 97.2 | Guideline Development | 71.6 | Introductions | 95.5 |

| Avoiding Distractions | 94.4 | Explanation of Care | 94.4 | ||

| Conduct | 96.4 | Response Time | 87.6 | ||

| Empathy | 96.4 | Punctuality | 94.7 | ||

| Positive Attitude | 94.1 | Grooming | 89.9 | ||

| Humor | 77.5 | Name Tag | 79.3 |

Figure 1.

Aggregate sliding scale Importance Ranking responses, ranked by decreasing median scores, for professionalism themes. Box-and-whisker plots represent medians (line), interquartile range (box), and 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers).

Regarding the domain-based working definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology, 92.8% of respondents indicated that the 11 domains identified formed a comprehensive list. Twenty-six respondents (12%) suggested additional novel candidate themes for consideration which were analyzed for (1) occurrence among the themes already represented, and (2) redundancy with other respondents. The 4 resulting unique candidate themes, in order of decreasing frequency of occurrence, are Wellness/Self-care/Burnout Prevention, Political Advocacy, Justice within a practice organization, and Respect for leadership/experienced partners.

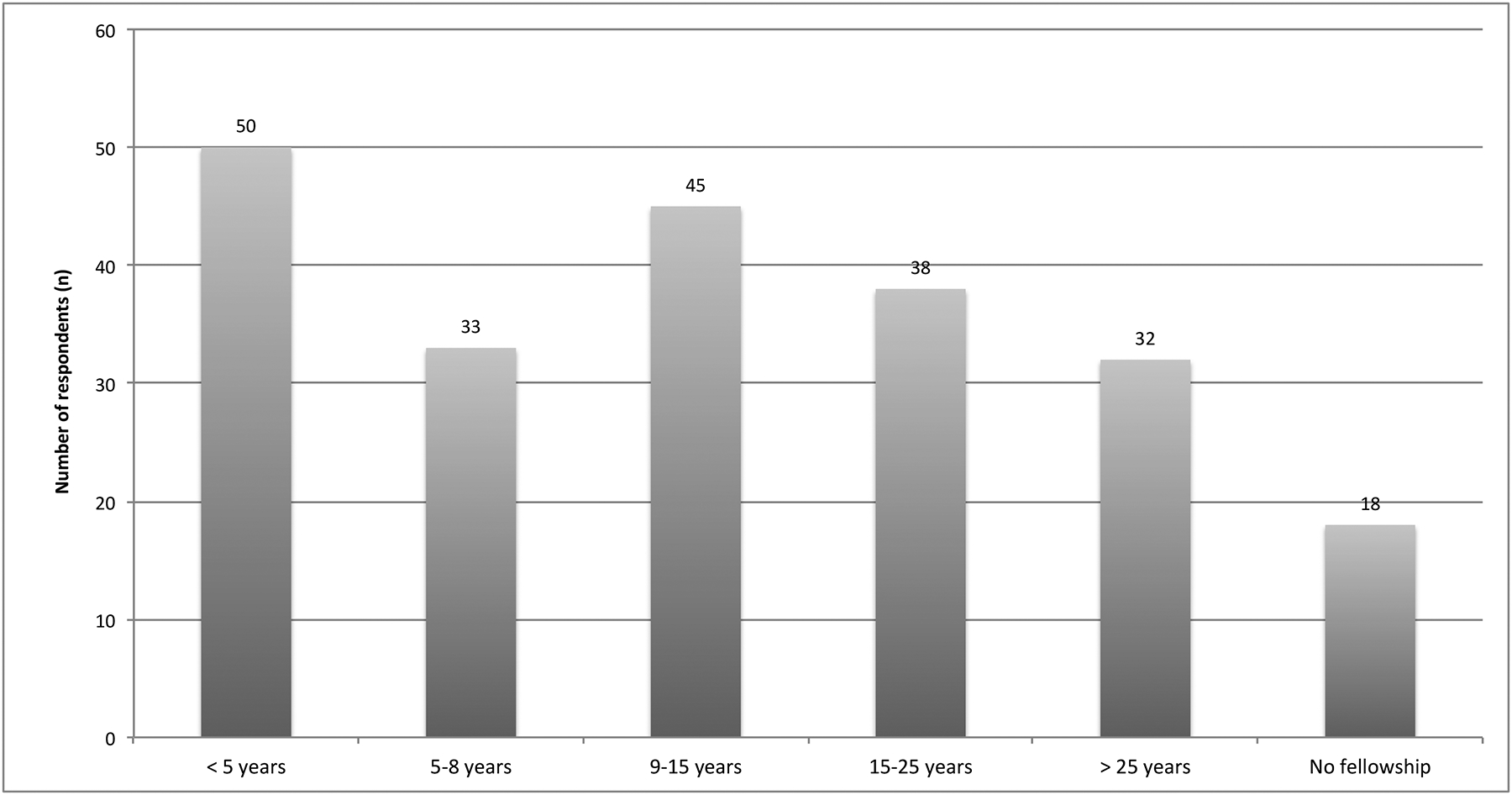

Respondents represented a wide variety of practice experience, as shown in Figure 2. A great majority (91.7%, n=198) of respondents report working with anesthesiology trainees (i.e. medical students, residents, or fellows) at least weekly, and 69%, (n=149) reported working with trainees multiple times per week.

Figure 2.

Elapsed time since respondents completed pediatric anesthesiology fellowship training.

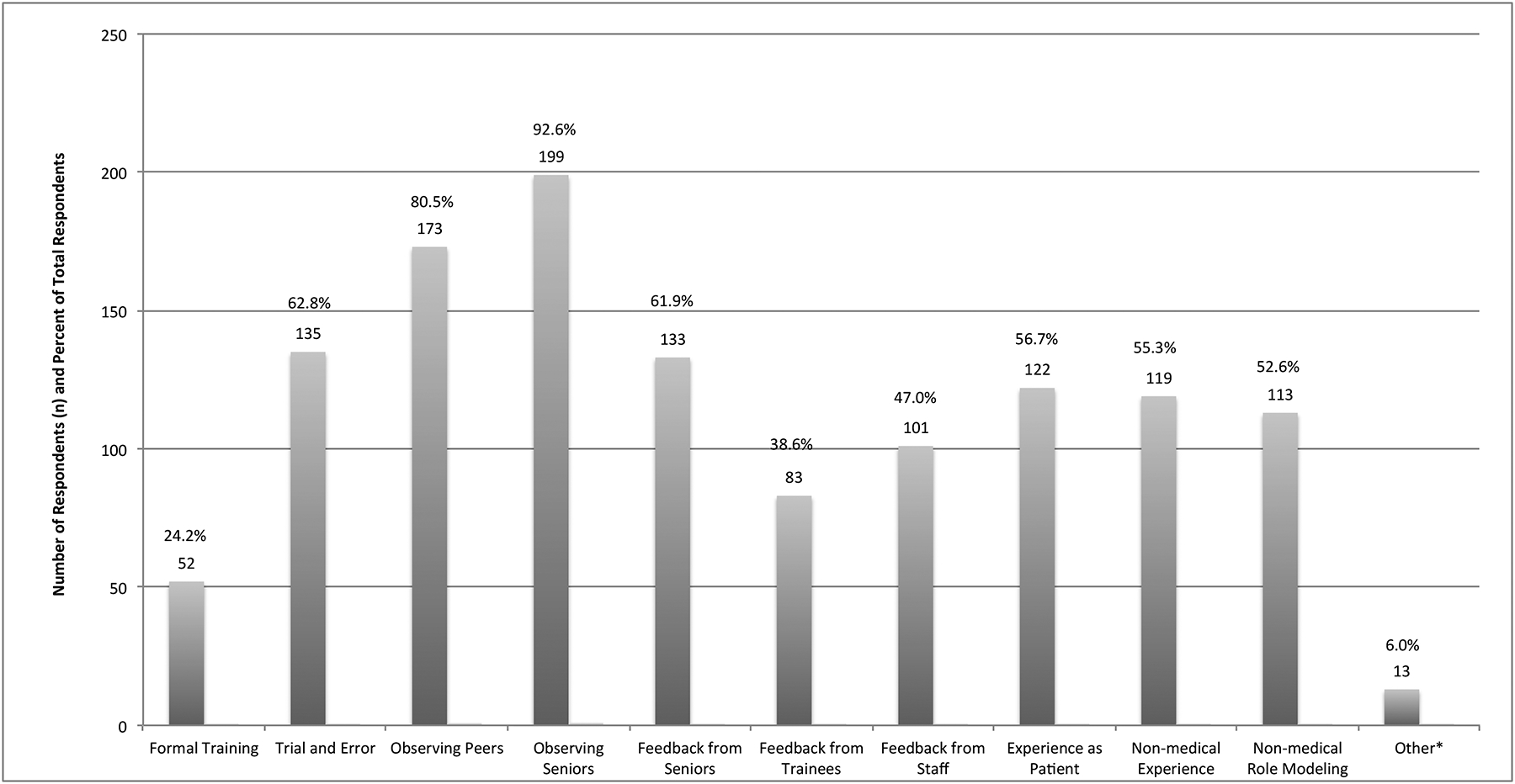

When asked to identify all modes of prior professionalism education, respondents selected a range of options, and nearly all (92.6%) selected the answer “Observing the behavior of my senior/more experienced colleagues” (Figure 3). In response to the question, “During training or since completion of training, how many hours of formal education in professionalism have you had? This may include professionalism seminars or lectures in addition to simulation-based professionalism training,” 45.3% reported no formal education, 31.3% reported 1–5 hours of formal education, and 23.4% reported at least 5 hours of formal education since medical school.

Figure 3.

How survey respondents report learning about professionalism at any time in the past. Respondents were instructed to select as many responses as desired. *Other responses included comments about military training, religious/spiritual background, teaching as a way to learn, and self-education. Percentages indicate the total number of respondents who selected each response.

A minority (16.4%) of respondents reported prior experience as a professionalism course leader or facilitator. As shown in Figure 4, the survey responses also indicated a near-universal agreement that didactic lectures would not be the most effective mode of teaching professionalism; this mode was supported by only 3.7% of respondents.

Figure 4.

Survey respondents’ choice about the single “most effective” mode of teaching about professionalism. *Other responses included comments about small group discussions, reflective writing, and multi-modal learning.

Discussion

The results of this nationwide survey of a snowball sampling-generated population of pediatric anesthesiologists serve to confirm the construct validity of our prior findings about professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology.2 Notably, every thematic element previously identified in our single-center study of stakeholders was endorsed in this larger and more diverse sample of pediatric anesthesiologists in the US. Similarly, the 11 domains characterizing our composite working definition were also considered comprehensive for the purpose of describing professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. While some respondents did suggest additional themes and domains, the vast majority of these were already included in the definitions of the themes and domains we have previously identified, and which were based on input from nurses, family members, surgeons, and anesthesiologists sampled in the first study; there were a total of four novel candidate themes that should be considered in future work, although this study was not designed for validation of these four themes by other respondents. This important result, that our definition appears to be both accurate and comprehensive, can be interpreted to mean that it is time to develop appropriate professionalism curricula based on our findings.

Several surprising elements were uncovered by our data. First, we note that the largest distribution of importance ranking for any single theme occurred for the theme of “consistently wearing a visible name tag.” While a majority of respondents supported this as part of the definition, the wide distribution of importance ranking of this element is intriguing because 1) name tag wearing is a fundamental regulation in many hospital codes of conduct and several states (including ours) have regulatory statutes about name tags;8 2) non-adherence to hospital identification badge policies is a source of Joint Commission regulatory noncompliance;9 and 3) we believe that as patients, and perhaps more importantly as parents of pediatric patients, our charges always deserve to be made aware of the names and roles of anyone engaged in clinical encounters.

A second surprising discovery was that the two themes thought to be least important in the definition, although still supported by a majority of respondents, were regulatory compliance (“practice is conducted in accordance with, or working to change, regulatory protocols and rules at the hospital and national level”) and clinical guidelines (“working to change care within the practice, or nationally, through guideline development”). The results may indicate that, despite overwhelming public specialty support for standardization of care through such mechanisms as Enhanced Recovery After Surgery programs,10 and despite the adoption of value-based reimbursement models that include outcome measures and regulatory compliance metrics, there may be some privately held beliefs that such standardization and regulation is not always professional. Alternatively, the relatively low importance rankings may indicate that compliance issues (e.g. adherence to hospital regulatory guidelines) have become so much an accepted part of pediatric anesthesiology practice that they are no longer an issue requiring the focus of an assessment of professionalism. Further study is needed to differentiate the nuanced meanings of the findings.

Finally, we note that over 75% of respondents (n=164) reported less than 5 hours of professionalism education since graduation from medical school. This is surprising for two reasons; first, a large number of respondents were relatively recent graduates from training programs (Figure 2), and the data may represent a gap in standards enforced by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) system. Specifically, the ACGME requires that all pediatric anesthesiology programs evaluate fellows regularly for professionalism and evaluate faculty at least annually for professionalism. In addition, the ACGME requires both education about professionalism and the creation of a culture that is supportive of professionalism and wellness.11 Second, one third of respondents (n=70) reported completion of training at least 15 years before completing the survey (thus graduating medical school at least 19 years prior). For these respondents, fewer than 5 hours of education in this area over two decades represents a gap in both ACGME standards11 and the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) system, which does not address professionalism or any specific content. The role of the ACCME is to accredit, but not to direct content for, the over 148,000 annual educational programs for physicians and other healthcare professionals.12 We have previously reported2 the phenomenon that professionalism education can and does occur via many different modalities, both intentional (by design) and unintentional (through the hidden curriculum.)15 Nonetheless, participants reported limited and variably presented professionalism education inferring a deficiency in the existence of a defined standard professionalism curriculum. We report this for consideration by pediatric anesthesiology practitioners, educators and specialty leaders.. Further study is warranted to confirm the existence of, and determine the nature of and benefits of establishing remedies for, the identified gaps in graduate and continuing medical education with a primary focus on professionalism.

This study has several important limitations. Most notably, the use of the snowball sampling method led to the inability to determine the response rate (due to unknown denominator size). While our hundreds of respondents represent a far larger number and more diverse sample than the original focus group samples that generated the working definition, we cannot know how many potential respondents were not invited to participate.13 Because the PAPDA and PALC groups include representation from every pediatric anesthesiology fellowship and every pediatric anesthesia department or clinical division (including some private practice groups) nationally, it is reasonable to assume that those invited represent an appropriately distributed sample with regards to geography and practice setting. Nonetheless, as with any survey, there is the potential for non-response bias to influence the results. As a consequence, it is possible that only those with particular interest in the topic of professionalism responded to the survey, which may preclude full generalizability to all pediatric anesthesiologists, but may also have included those with a particular interest or expertise in the area. Additionally, because the sampling focused on training programs and hospital departments and practices only within the US, the results may not be generalizable to all pediatric anesthesiologists or hospitals globally. Indeed, cultural expectations of physicians vary significantly between nations, and any definition of professionalism in any specialty may thus necessarily be nation-specific.14 For this reason, the definition we have generated is best thought of as a US-based definition, and further study about the effects of cultural norms and beliefs on definitions internationally should also be considered. Finally, as the study was not designed to assess criterion validity, we have yet to demonstrate that these concepts of professionalism are associated with improved behaviors or outcomes.

Despite these limitations, there are also several important strengths of this study. Most notably, we believe this to be the largest cohort of pediatric anesthesiologists to respond to any survey about professionalism in the specialty; as such, the responses represent an important sample of the profession. Another strength surrounds the diversity of the sample with regards to years in practice and exposure to modes of professionalism education. While the previous study allowed for generation of the themes tested herein, a strength of this study design is that it enabled respondents to identify novel professionalism concepts due to the ability of respondents to anonymously add new theme ideas; this has the potential to elicit themes not mentioned during focus groups due to social desirability bias. Finally, our data have affirmed our belief that didactic lectures about professionalism should not be emphasized in addressing pediatric anesthesiology professionalism curriculum deficiencies. In contrast, respondents endorsed our goal of creation of curricula that involve discussion and reflection as shown in Figure 4.

We also recognize (as affirmed by the present study) that the consequences of the hidden curriculum15 demand training curricula that focus on faculty and practitioners as much, or more, than on trainees in order to be effective. Thus, an important next step for this research, in addition to the areas for future study indicated above, is to develop a working group to create a case-based, faculty-directed, reflective curriculum for professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology. Based on the data that our diverse group of respondents provided in this hypothesis-generating study, we plan to focus on simulation-based (or video-based) case stems/scenarios designed to elicit discussion among small groups of learners.

Conclusion

The results of this national survey of pediatric anesthesiologists confirmed the construct validity of the prior working definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology as we have reported it, and have also uncovered several opportunities and controversies for curriculum development and further study. We believe the most important conclusion of this work is the overwhelming support for all 40 themes by participants, and that it is time to develop and incorporate strong graduate and continuing medical education programs in professionalism, especially in the domains of communication and teamwork. We believe these results should also provide a basis for advancing ACGME and ACCME policies and metrics for professionalism within Pediatric Anesthesiology as well as help to inform development and refinement of professionalism milestones across other specialties.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1 Survey Tool for Professionalism in Pediatric Anesthesiology.

Clinical Implications.

What is already known:

Specialty-specific definitions of professionalism are important for the creation of relevant curricula for professionalism.

What this article adds:

This study used a national survey of U.S. pediatric anesthesiologists to affirm the previously generated working definition of professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology.

This study uncovers significant gaps in both training programs and continuing medical education programs surrounding professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology.

Footnotes

Disclosures

This study was reviewed by the CHOP Institutional Review Board and was exempted. Drs. Lockman, Yehya, Schwartz, and Cronholm have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Kearney RA. Defining professionalism in anaesthesiology. Med Educ 2005; 39: 769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lockman JL, Schwartz AJ, Cronholm PF. Working to define professionalism in pediatric anesthesiology: a qualitative study of domains of the expert pediatric anesthesiologist as valued by interdisciplinary stakeholders. Pediatric Anesthesia 2017; 27: 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen MJ, Konia MR, Borman-Shoap EC, Braman JP, Tiryaki E, Marcus-Blank Bm Andrews JS. Not all unprofessional behaviors are equal: The creation of a checklist of bad behaviors. Med Teach 2017; 39: 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riveros R, Kimatian S, Castro P, Dhumak V, Honar H, Mascha EJ, Sessler DI. Multisource feedback in professionalism for anesthesia residents. J Clin Anesth 2016; 34: 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin LD. Professionalism: in the eye of the beholder. Pediatric Anesthesia 2017; 27: 226–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noy C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2008; 11(4): 327–344. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rules and Regulations [28 Pa. Code Ch. 53]. The Pennsylvania Bulletin; Available at: https://www.pabulletin.com/secure/data/vol41/41-50/2107.html. Accessed February 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Standards FAQ Details. The Joint Commission; Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/jcfaqdetails.aspx?StandardsFAQId=1115. Accessed February 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beverly A, Kaye AD, Ljungqvist O, Urman RD. Essential Elements of Multimodal Analgesia in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Guidelines. Anesthesiol Clin 2017; 35: e115–e143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACGME Common Program Requirements for One-year Fellowships. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/One-Year_CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

- 12.The ACCME Accreditation System. Available at: http://www.accme.org/physicians-and-health-care-professionals/accme-accreditation-system. Accessed February 8, 2018.

- 13.Halpern SD, Asch DA. Commentary: Improving response rates to mailed surveys: What do we learn from randomized controlled trials? Int J Epidemiol 2003; 32: 637–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu L, Yin X, Bao X, Nie JB. Chinese physicians’ attitudes toward and understanding of medical professionalism: results of a national survey. J Clin Ethics 2014; 25: 135–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaiser RR. The teaching of professionalism during residency: why it is failing and a suggestion to improve its success. Anesth Analg 2009; 108: 948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1 Survey Tool for Professionalism in Pediatric Anesthesiology.