Abstract

The development of large-scale data sets requires a new means to display and disseminate research studies to large audiences. Knowledge of protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks has become a principle interest of many groups within the field of proteomics. At the confluence of technologies, such as cross-linking mass spectrometry, yeast two-hybrid, protein cofractionation, and affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP–MS), detection of PPIs can uncover novel biological inferences at a high-throughput. Thus new platforms to provide community access to large data sets are necessary. To this end, we have developed a web application that enables exploration and dissemination of the growing BioPlex interaction network. BioPlex is a large-scale interactome data set based on AP–MS of baits from the human ORFeome. The latest BioPlex data set release (BioPlex 2.0) contains 56 553 interactions from 5891 AP–MS experiments. To improve community access to this vast compendium of interactions, we developed BioPlex Display, which integrates individual protein querying, access to empirical data, and on-the-fly annotation of networks within an easy-to-use and mobile web application. BioPlex Display enables rapid acquisition of data from BioPlex and development of hypotheses based on protein interactions.

Keywords: BioPlex, AP–MS, protein interactions, protein complexes, web application, graph display, term enrichment, network communities, data visualization, PHP/MySQL

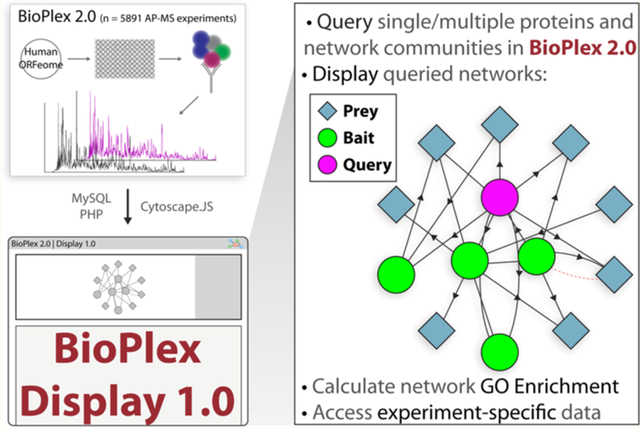

Graphical Abstract

BACKGROUND

Data visualization for large-scale protein interaction networks has become an important seed for hypothesis generation. Many integrated platforms have been developed to display protein interaction data in formats that enable users to access, interact with, and use these data to their own ends.1–4 The flexibility of these network display platforms provides rapid access to a wealth of biological information with only an Internet browser (no third party software) and minimal user input. Thus data visualization of protein interaction graphs provides a layer of data assimilation that can enhance researchers’ utilization of complex biological network information.

To this end, we developed a web application for the display and dissemination of the BioPlex interaction network, termed BioPlex Display. The BioPlex network is the largest set of affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP–MS) experiments ever assembled (with the latest data release consisting of >5891 individual experiments).5,6 The shear amount of data can be cumbersome for individual users to manipulate and interact with on a global scale. Moreover, owing to a need to incorporate data from many different sources, more generic applications often cannot provide multidimensional or experiment-specific details pertaining to large-scale protein interaction efforts, although these data may be abundantly useful for researchers. For BioPlex in particular, no platform existed to provide a unified point of entry to access individual network information, highly interconnected network communities, subthreshold interactions, and experiment specific information, like peptide spectral match (PSM) counts for individual AP–MS experiments. With BioPlex and a need for a multifunctional data distribution utility in mind, we developed BioPlex Display to simplify the process by which researchers are able to interrogate proteins of interest, determine interacting partners, generate graphs, and interact with related information derived from Gene Ontology annotations and the UniProt Knowledgebase.7,8 Initial numbers (e.g., 1089 average, unique users per month) suggest that this tool will be a highly utilized framework for user interaction with the BioPlex project resources.

DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

General Application Information

BioPlex Display was developed as a PHP web application (Figures 1 and 2A). The core modules of the application are built in PHP 5.4 with MySQL for database queries and are run on a Linux virtual machine (Ubuntu 14.04.5 LTS, Apache 2.4.7). Networks are displayed using Cytoscape.js, a JavaScript-based Cytoscape library for graph visualization.9 User selection of a protein of interest from the 11 574 proteins identified in interactions within the BioPlex network will query all relevant data for a protein subnetwork to be displayed (see below). Without further user input, only those interactions for which the probability of interaction was determined to be significant are displayed, although “sub-threshold” interactions can be displayed down to a probability of interaction as low as 0.5.5,6 The web application can be found at: http://bioplex.hms.harvard.edu/bioplexDisplay/. Information for users can be found at the help site within the web application. Lastly, we have implemented a wrapper to allow external queries of BioPlex Display to enable users to easily share networks of interest and to allow other applications to link into BioPlex Display.

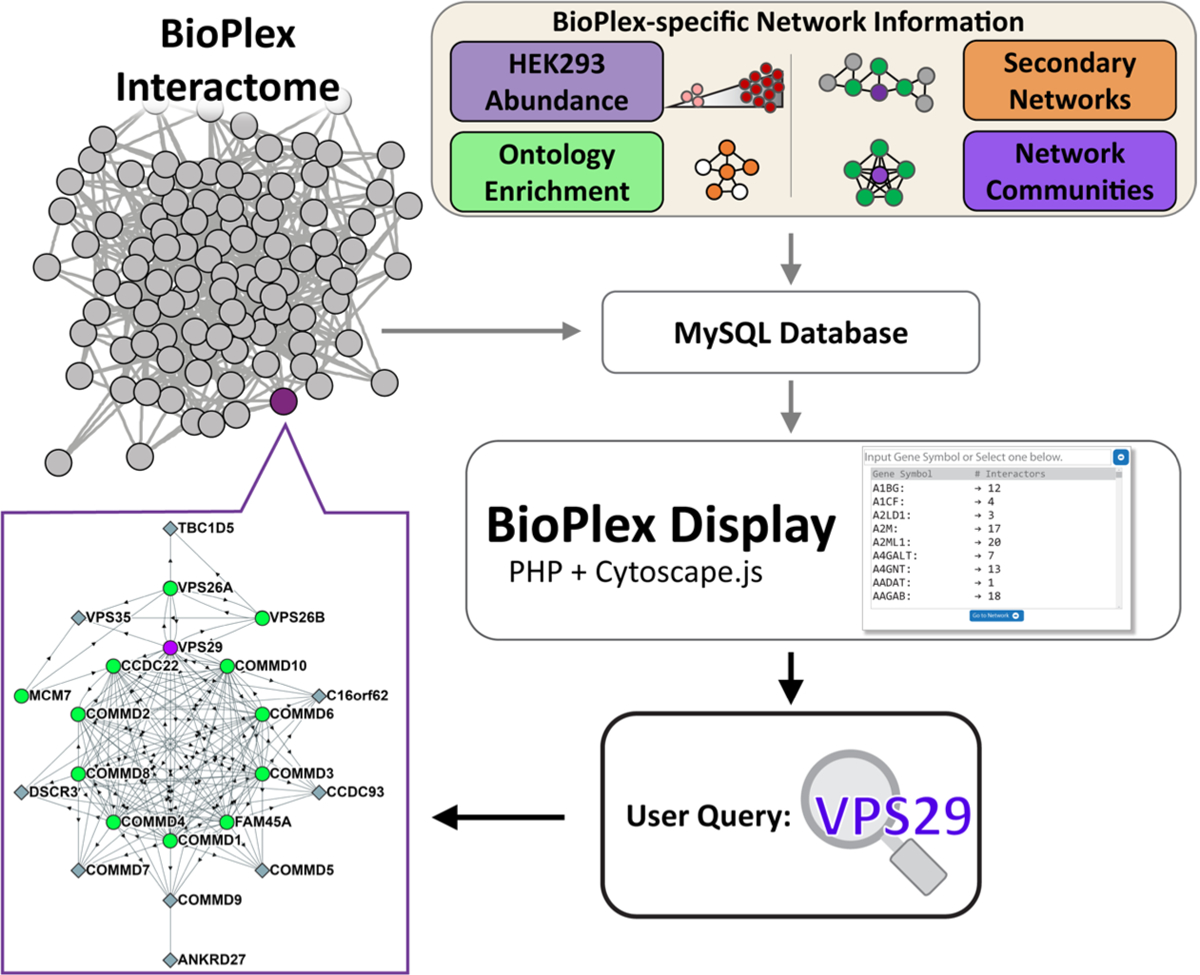

Figure 1.

Overview of BioPlex Display and general information on the graph representations. The BioPlex interactome network consisting of bait–prey interactions as well as annotations and additional information is stored in MySQL databases. These databases are queried in real time with the user accessing the site to generate graph representations of the protein interaction network for a specific input. (The example given is for the retromer complex subunit VPS29.)

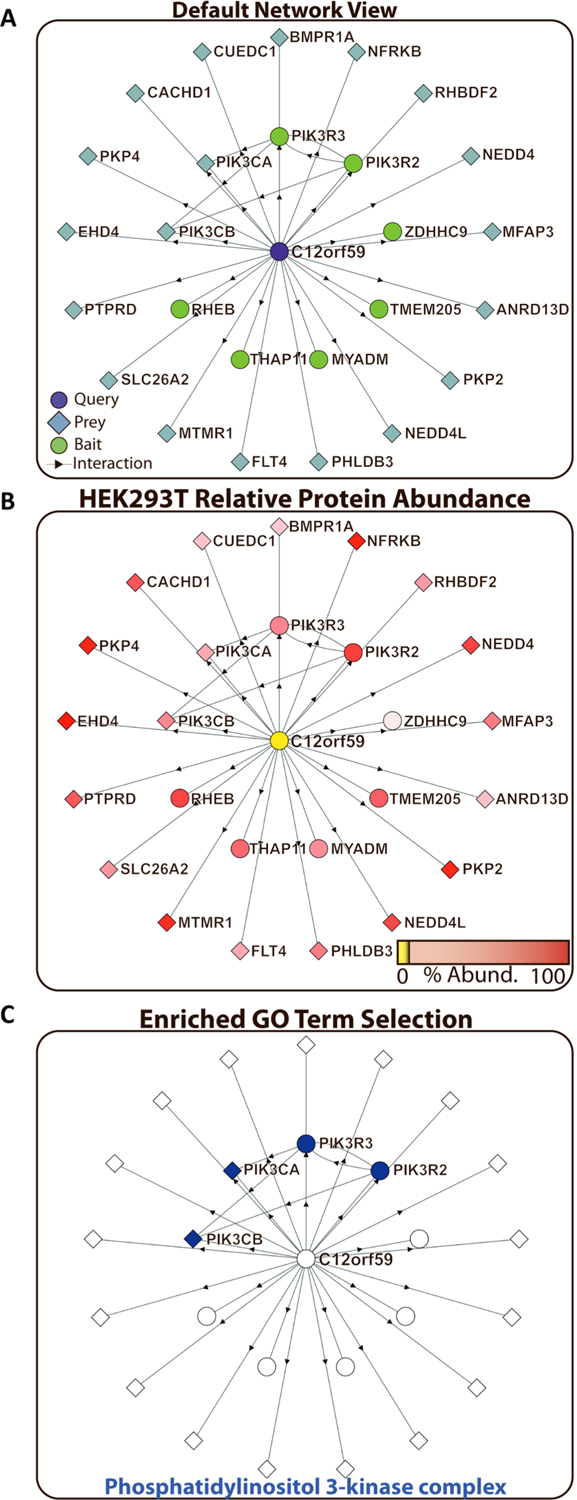

Figure 2.

Network exploration and hypothesis development for the uncharacterized protein C12orf59. (A) Default representation of a queried protein interaction subnetwork. Proteins used as baits at some point in the BioPlex project are shown as green circles. Proteins only identified as preys are shown as blue diamonds. The original protein query is highlighted in purple, and its annotation as either a BioPlex bait (circle) or a prey-only protein (diamond) is retained. (B) On the basis of previous spectral-counting data for HEK293T cells, the relative protein abundance for each protein in the C12orf59 network is shown as a gradient from high expression (red) down to no detection (yellow). (C) For each protein interaction network, gene ontology (GO) annotation enrichment is calculated. Proteins belonging to specific GO annotation groups can be highlighted. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex proteins (orange nodes) were observed to be enriched in the C12orf59 interaction network (Fisher’s Exact test adjusted p-value: 2.30 × 10−8).

HEK293 Protein Abundance Percentile

Using data previously established through the initial BioPlex paper, we included HEK293T abundance data for each protein found in BioPlex (Figure 2B).6 These data were assembled from deep-fractionation and label-free quantification of HEK293 proteins and, among other things, can be used to assess the relative enrichment of binding partners due to AP–MS. As noted in the legend below each network, coloring the network based on HEK293 abundance will change each node to a graduated color between the 1st and 100th abundance percentile. If the protein was within the zeroth abundance (yellow label), then it was not observed in the deep fractionation study. Of note, many proteins have very low HEK293 abundance in wild-type cells, but they are found in the interactome data set either because they were expressed as tagged-bait proteins or they were found as prey proteins owing to the enrichment inherent to affinity purification of stable protein complexes.

Gene Ontology Annotations

For each input protein, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichments are calculated on the fly (Figure 2C). GO information for individual proteins is based on the annotations downloaded 01/06/17.7,10 The enrichment significance is calculated using a Fisher’s Exact Test with binomial calculations transformed to log space to retain precision for even extremely low values in PHP. While we developed functions for exact calculation of the constituent factorials, as the protein interaction database becomes larger, we have been required to use factorial approximation to improve load speeds.11 All enrichment p-values are corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment.12 For p-value calculation, all term categories (biological process, molecular function, cellular component) are used. Default calculations require at least two proteins within a subnetwork to be present in any given GO category for one-hop networks and seven proteins to be present within a subnetwork for two-hop networks. These parameters were chosen to ensure efficient loading of the application but can be modified by users through the site to expose GO categories with higher adjusted p-values.

Network Manipulation and Data Export

The network display and interaction were enabled through the use of Cytoscape.js JavaScript libraries.9 Thereby users can thoroughly interact with and rearrange nodes and edges to visualize their data as they find necessary or useful. Of note, because JavaScript is run client-side, users can employ developer tools in most modern browsers (e.g., Chrome, Firefox) and functionality within Cytoscape.js to update graph styles at will.9 The use of a JavaScript graph theory library also enables access to and interaction with BioPlex Display from mobile devices. BioPlex Display allows for export of images (PNG) and flat files containing information pertaining to a specific protein’s interaction network. Flat files are compatible with other display platforms such as ProtHits-Viz.13 Data can also be exported as JSON arrays that can be directly uploaded into Cytoscape 3.0 to enable users to further interact with and assemble those biological networks of interest.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To access the interactome information within BioPlex Display, a user need only select or input a gene symbol of interest (e.g., VPS29 in Figure 1). Once selected the input will be queried against the BioPlex network for confident interactions.5,6 The user is then empowered to explore general information pertaining to the proteins that interact with their query. In the case of VPS29, BioPlex Display visualizes interactions between the VPS29-containing retromer complex (VPS26A, VPS26B, VPS35) and subunits of the recently described Commander Complex (COMMD1-10).14 Proteins are displayed as being either a bait or a prey protein, meaning that they were either one of the 5891 tagged, bait proteins derived from the human ORFeome collection15 or were identified solely as untagged, prey proteins. The directionality of the edges (from bait to prey) is noted for each interaction by an arrow. Selecting an individual edge will reveal the probability of interaction for the selected edge. Reciprocal interactions occurring when two proteins were both tagged, used as bait proteins, and observed to interact with each other are indicated by multiple connecting edges. We further included functionality to allow users to take advantage of the multiple layout schemes available through Cytoscape.js (e.g., concentric circles, hierarchical, compound spring embedded,16 or gridded nodes) to enable more flexibility during display.

Extending from the basic query framework users are also enabled to query multiple protein symbols (using comma-separated strings such as “Bad, BCL2L1, Bax”) to generate unique multiprotein interaction graphs. These maps can be used to help researchers interrogate a specific subset of interactions and test whether several proteins of interest were observed to interact in the BioPlex network. Along with this multiprotein querying, we have developed a query tool to allow users to search for proteins of interest within the 1320 protein interaction communities identified in the assembly of BioPlex 2.0.5,6 These highly interconnected communities represent important protein complexes (e.g., TFIID protein complex in community 135) or proteins connected through their roles in similar pathways (e.g., RNA processing in community 1). Through the use of the network community viewer, users can now not only examine the most enriched GO terms for these communities but also rapidly access a compendium of enriched GO annotations to go along with the interactions, graphs, and AP–MS data.

Assembly of the BioPlex interactome required extensive filtering of identified spectral matches to eliminate both false discoveries and spurious or nonspecific protein identifications from each AP–MS experiment. These filters are explained elsewhere.5,6 Yet the ability to view the proteins identified in each AP–MS experiment can enable a more in-depth understanding of the specificity of interactions. To this end we have (1) included functionality to enable users to append interactions that fall below the strict statistical thresholds (probability of interaction 0.75 or greater) used to generate the final BioPlex protein interaction network and (2) developed a novel tool for querying the total PSMs observed for an individual protein across all 5891 individual AP–MS experiments. Display of “sub-threshold” interactions can aid researchers in the analysis of “near miss” interactions. The PSM query tool also allows users to examine which proteins may have been present in an individual AP–MS experiment but were not called interactors in BioPlex. We highlight the example of the molecular chaperone Hsp90β (HSP90AB1), which was found in a large number of AP–MS experiments, yet Hsp90β was called as an interactor for only 23 proteins, emphasizing the stringent filters in place for a protein–protein interaction (PPI) to be called (Figure S1). Notably, among the 23 proteins interacting with Hsp90β there was an enrichment for protein kinases, and specifically cell cycle kinases, which was consistent with previous findings detailing Hsp90s requirement for cellular proliferation.17 Furthermore, the Hsp90β case emphasizes the utility of multidimensional data that is facilitated through BioPlex Display.

We believe that the BioPlex Display application will enable the generation of new hypotheses based on the simplicity of accessing the underlying BioPlex network. As an example of this, we highlight the interaction network surrounding C12orf59. Although C12orf59 has no known function, the protein was observed interacting with four components of the PI3K complex (catalytic: PIK3CA, PIK3CB; regulatory: PIK3R3, PIK3R2) (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the interactions with multiple regulatory and catalytic PI3K subunits suggest that C12orf59 interacts with more than one form of the PI3K complex, which normally exists as a heterodimeric complex consisting of one regulatory and one catalytic component. Here we also highlight the ability of BioPlex Display to generate secondary interaction graphs, that is, interactions between proteins in the C12orf59 network and “secondary” proteins that were not called as direct interactors for C12orf59 but interacted with C12orf59’s interactors (Figure S2).

In silico analysis of C12orf59 predicted two transmembrane domains, with a predicted localization of the main body of the protein to the cytoplasm, where it could interact with PI3K subunits (Figure S3).18 Additionally, down regulation of C12orf59 has previously been found to be associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma, although no mechanism for this association was determined. This further indicates that C12orf59 may play a role in regulating renal cell signal transduction, potentially through modulation of the PI3K pathway.19 The ability to connect graph representations of this BioPlex subnetwork with GO enrichment information, the Uniprot Knowledgebase, and other third-party applications allowed us to posit that this uncharacterized protein may play a role in PI3K signaling.

Although the primary focus of the BioPlex project has been to map protein interactions within a single cell line, we are beginning to expand the BioPlex platform to profile interactions in additional cell lines as a form of large-scale validation and as an initial attempt to quantify cell-type specificity in protein interaction networks.5,6 As BioPlex moves into new cell lines, we will expand BioPlex Display to allow for the overlay of interactions from different data sets and cell lines. The data output from BioPlex Display will be made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License to enable worldwide, simple, free access to the network information and generated graphs. In future releases of BioPlex Display, we are hoping to add utilities for the integration of protein localization prediction and domain–domain interaction networks to further enable the useful exploration of this large resource.

Finally, we note that while other web applications exist for the display of protein interaction networks,1–3 the novelty and primary utility of BioPlex Display lies in an ability to integrate multiple dimensions of the BioPlex project’s AP–MS results (e.g., bait-prey annotation, PSM data, interaction networks, protein communities within the network, subthreshold protein interactions, etc.). No other software platform currently has the capability to display and disseminate all of these data in an easily accessible platform. We further note the difference in the interaction networks between STRING and BioPlex Display networks in Figure S3, which highlights that although interactions may be observed in the BioPlex network, they may not currently be annotated in other applications. We believe that BioPlex Display is made more valuable by allowing flexible and in-depth interrogation of the BioPlex network, allowing researchers to not only examine protein interactions specific to BioPlex but also generate figures for display and presentation elsewhere.

CONCLUSIONS

The BioPlex Display web application was developed to enable general dissemination and interaction with the extensive AP–MS-based human protein interaction network determined through thousands of individual experiments. The aim of the work presented here was to assemble this data into an easy to use framework of graph display, data overlay, and links to biologically relevant external tools to enable users to deploy the information for the development of novel hypotheses. Furthermore, the capabilities of the PHP/MySQL framework will allow the BioPlex Display application to grow seamlessly with the continued experimental output of the main BioPlex project.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Harper and Gygi laboratories for both advice and beta-testing of the application, particularly Dr. Joao Paulo, Dr. Brian Erickson, Dr. David Nusinow, and Ramin Rad for assistance with networking and implementation. We also thank the following funding sources for supporting this project: National Institutes of Health (U41 HG006673 to S.P.G, J.W.H., E.L.H), and Biogen (to S.P.G, J.W.H.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00572.

Figure S1. Peptide spectral match plot across all 5891 AP–MS experiments for Hsp90β (HSP90AB1). Figure S2. Example of secondary network interactions for the protein C12orf59. Figure S3. Prediction of C12orf59 localization and potential functions. (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): S.P.G is a consultant for Biogen, Inc.

REFERENCES

- (1).Szklarczyk D; et al. The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein-protein association networks, made broadly accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D362–D368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Schweppe DK; et al. XLinkDB 2.0: integrated, large-scale structural analysis of protein crosslinking data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2716–2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Combe CW; Fischer L; Rappsilber J xiNET: cross-link network maps with residue resolution. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14, 1137–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Mostafavi S; Ray D; Warde-Farley D; Grouios C; Morris Q GeneMANIA: a real-time multiple association network integration algorithm for predicting gene function. Genome Biol. 2008, 9 (1), S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Huttlin EL; et al. Architecture of the human interactome defines protein communities and disease networks. Nature 2017, 545, 505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Huttlin EL; et al. The BioPlex Network: A Systematic Exploration of the Human Interactome. Cell 2015, 162, 425–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).The Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D1049–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).The UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D158–D169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Franz M; Lopes CT; Huck G; Dong Y; Sumer O; Bader GD; et al. Cytoscape.js: a graph theory library for visualisation and analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 32, btv557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Carbon S; et al. AmiGO: online access to ontology and annotation data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 288–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ramanujan Aiyangar S The Lost Notebook and Other Unpublished Papers; Narosa Pub. House, 1988; Ch. 3, p 339. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Benjamini Y; Hochberg Y Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc., Ser. B 1995, 57 (1), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Knight JD; et al. A web-tool for visualizing quantitative protein-protein interaction data. Proteomics 2015, 15, 1432–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mallam AL; Marcotte EM Systems-wide Studies Uncover Commander, a Multiprotein Complex Essential to Human Development. Cell Syst 2017, 4, 483–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lamesch P; et al. hORFeome v3.1: a resource of human open reading frames representing over 10,000 human genes. Genomics 2007, 89, 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Dogrusoz U; Giral E; Cetintas A; Civril A; Demir E A layout algorithm for undirected compound graphs. Inf. Sci 2009, 179, 980–994. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Okamoto J; et al. Inhibition of Hsp90 leads to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human malignant pleural mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol 2008, 3, 1089–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Krogh A; Larsson B; von Heijne G; Sonnhammer EL Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol 2001, 305, 567–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Xie J; et al. Down-regulation of C12orf59 is associated with a poor prognosis and VHL mutations in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 6824–6834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.