Abstract

Background

Few studies examined associations between depressive symptoms and metabolic syndrome (MetS) among older Chinese adults. Considering that the prevalence of depressive symptoms is high in older Chinese adults, we aimed to examine associations of depressive symptoms with MetS and its components in older Chinese adults.

Methods

Data from a community-based cross-sectional study of 4579 Chinese adults aged 60 years or older were analyzed. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire. The presence of MetS was defined based on the Adult Treatment Panel III criteria, which include obesity, reduced blood high-density lipoprotein, high blood pressure (BP), elevated fasting plasma glucose and hypertriglyceridemia. A participant was considered as having MetS if he or she met at least three of the above-mentioned criteria.

Results

In all participants, depressive symptoms were related to elevated fasting plasma glucose (≥ 7.0 mmol/L) (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 1.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] [1.00–2.20]) and diabetes (adjusted OR = 1.50, 95% CI [1.01–2.20]). The associations of depressive symptoms with MetS and its components were not significant among women. However, there was a negative association between depressive symptoms and elevated systolic BP (≥ 130 mm Hg) (OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.4–0.9]), and similar findings were observed after adjusting for lifestyle-related variables in men.

Conclusions

In older Chinese adults, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with elevated systolic BP in men while these findings were not found in women.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, Metabolic syndrome components, Public health, Epidemiology

Background

The World Health Organization has estimated that more than 300 million people worldwide suffered from depression in the year 2015 [1]. Depression is a major mental health problem in old people. Population-based prevalence of depression in seniors was about 4.2–25.1% as reported in different studies [2–5]. Individuals with depressive symptoms may be also susceptible to metabolic syndrome (MetS) which is a common health issue in older adults. The potential mechanism might be related to its co-occurrence with obesity [6], as obesity is an important component of MetS and visceral adipose tissue secretes inflammatory cytokines that could cause chronic inflammation, and trigger MetS [7–9]. In addition, gender may be an effect modifier in the relationship between depression or depressive symptoms and MetS, even though studies reported inconsistent findings regarding the moderation effect of gender on the association between depression and MetS [10–12]. For example, a longitudinal study in Europe indicated that women but not men with depressive symptoms are vulnerable to MetS [10, 11]. On the contrary, a study from Japan found that the association only presented in men [12]. But a study conducted in Norway found none of the interaction effects related to gender [13].

Depression is a mental health problem affected by various psychosocial factors, findings from a single study conducted in a specific area can not be extrapolated to other populations with different age, culture and ethnicity. The prevalence of depressive symptoms is high in older Chinese adults [14]. But few studies assessed its association with MetS among this population. Thus, this study aimed to assess the association of depressive symptoms with MetS in Chinese adults aged 60 years or older in a community-based study.

Methods

Study design and procedure

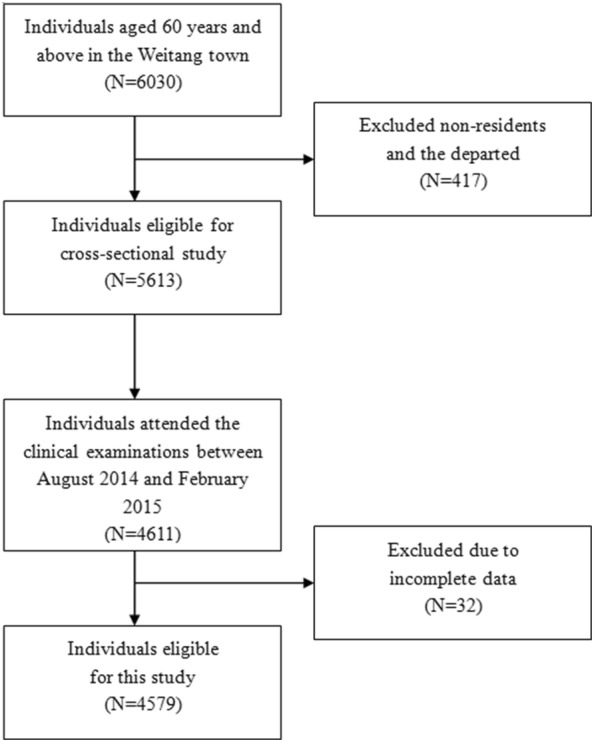

Weitang Geriatric Diseases study is a community-based study conducted in the Weitang town among adults aged 60 years or older in Suzhou located in the east part of China. Detailed study protocol has been described elsewhere [15, 16]. Briefly, participants were screened based on local official records and those (n = 6030) aged 60 years or older were invited via sent-home letters. Exclusion criteria applied to those whom had migrated from the residing address, had been living there shorter than 6 months, or deceased. From August 2014 to February 2015, a total of 5613 adults enrolled and 4611 attended the clinical examinations. (Fig. 1) The final sample consisted of 4579 participants with completed data from anthropometric examinations and blood sample analyses.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart for sample construction of the cross-sectional study

The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soochow University.

Assessment of depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which is a validated instrument with high sensitivity and specificity [17, 18]. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items and each item corresponds to one criterion of the fourth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnosis for symptoms of major depression [18]. Eight items of the PHQ-9 are about the frequency of depressive symptoms, and the last item is about the frequency of thinking about hurting themselves during the past two weeks. Item responses were based on a 4-point Likert scale of “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days”, and “nearly every day” with the scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Participants with total scores ranging from 5 to 27 were regarded as having depressive symptoms [18, 19].

Assessment of MetS and its components

Body weight was measured in kilograms with light clothing using a digital scale. Height was measured in centimetres without shoes using a wall-mounted measurement tape. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Blood samples were collected and analyzed with the standard laboratory assays to obtain high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and blood triglycerides. Blood pressure (BP) was measured at least 3 times after 5 min or longer intervals of rest with an automatic blood pressure monitor (Dinamap model Pro Series DP110X-RW, 100V2; GE Medical Systems Information Technologies, Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States). The value of BP was calculated from the average of the last two readings. The definition of MetS was based on the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III [20]. A participant was considered as having MetS if he or she met at least three of the following criteria: (a) abdominal obesity defines as BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher [21], (b) HDL cholesterol lower than 40 mg/dL for men when 50 mg/dL for women, (c) BP of 130/85 mmHg or above or use of antihypertensive medications, (d) FPG of 7.0 mmol/L or greater or with physician-diagnosed diabetes mellitus, (e) blood triglycerides defines as 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or above.

Assessment of covariates

The data of social-demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender, education level, marital status) was collected by trained interviewers using a pre-designed questionnaire. Marital status was divided into living “with” and “without” spouse, and education level was classified into “primary education or below” and “secondary education or above”. Lifestyle-related variables including smoking (current/former/never), alcohol drinking (drinkers/non-drinkers), tea consumption (drinkers/non-drinkers), dietary pattern (normal/vegetarian) and sleep quality (good/intermediate/poor) were self-reported. Information regarding medication intake were collected and no participants had used antidepressant medications before.

Statistical analysis

To compare the characteristics of participants with and without depressive symptoms, Chi square test and student’s t-test were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Associations of depressive symptoms with MetS and its components were assessed using logistic regression models. All models were established separately for MetS and its individual components (i.e. BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 130 mm Hg, diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 85 mm Hg, blood triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, HDL cholesterol < 1.0 in men or < 1.3 mmol/L in women, FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, diabetes). Model 1 did not adjust for any covariates. Model 2 adjusted for social-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education level, and marital status). Model 3 additionally adjusted for lifestyle habits (smoking, alcohol consumption, tea consumption, dietary pattern, and sleep quality). In addition, gender-stratified analyses were performed to examine the interaction effects of gender.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of the participants included in this analysis was 67.4 ± 6.3 years old. Individuals with depressive symptoms accounted for 8% of the whole population and women were more likely to have depressive symptoms (P < 0.001). The characteristics of participants with and without depressive symptoms have been reported in a previous publication [22]. Table 1 shows comparisons of participants’ statuses of MetS and its components by the presence of depressive symptoms in the overall sample and in males and females, separately. Overall, 20.0% of the participants without depressive symptoms and 20.8% with depressive symptoms were affected by MetS and the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.70). With regards to the specific components of MetS, we found that participants with depressive symptoms tended to have lower BMI (P<0.001) and lower DBP (P = 0.04). The distributions of other MetS components between participants with and without depressive symptoms were not significantly different. Gender-stratified analyses indicated that depressive women were more likely to have lower BMI (P = 0.001), and depressive men tended to have lower DBP (P = 0.02) and lower triglycerides (P = 0.012) compared with their non-depressive counterparts.

Table 1.

Metabolic syndrome characteristics of study participants by gender and depressive symptoms

| Total | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No depressive symptoms (n = 4214) | Depressive symptoms (n = 365) | P | No depressive Symptoms (n = 2124) | Depressive symptoms (n = 255) | P | No depressive symptoms (n = 2090) | Depressive symptoms (n = 110) | P | |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 843 (19.99) | 76 (20.82) | 0.70 | 548 (25.77) | 60 (23.53) | 0.44 | 295 (14.12) | 16 (14.55) | 0.90 |

| High BMIa, n (%) | 825 (19.59) | 59 (15.89) | 0.09 | 382 (17.99) | 37 (14.51) | 0.17 | 444 (21.20) | 21 (19.09) | 0.59 |

| High BPb, n (%) | 3604 (85.54) | 326 (89.32) | 0.047 | 1863 (87.71) | 234 (91.76) | 0.058 | 1741 (83.34) | 92 (83.63) | 0.94 |

| High triglyceridesc, n (%) | 931 (22.08) | 80 (21.92) | 0.94 | 561 (26.38) | 63 (24.71) | 0.57 | 370 (17.71) | 17 (15.45) | 0.55 |

| Low HDLd, n (%) | 965 (22.89) | 87 (23.84) | 0.68 | 720 (33.88) | 74 (29.02) | 0.12 | 245 (11.73) | 13 (11.82) | 0.98 |

| Glucose componente, n (%) | 462 (10.97) | 50 (13.70) | 0.11 | 237 (11.16) | 33 (12.94) | 0.40 | 225 (10.77) | 17 (15.45) | 0.13 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 23.32 (2.61) | 22.81 (2.82) | < 0.001 | 23.26 (2.61) | 22.66 (2.89) | 0.001 | 23.39 (2.62) | 23.14 (2.65) | 0.33 |

| Fasting glucose, mean (SD), mmol/L | 5.58 (1.10) | 5.68 (1.57) | 0.25 | 5.64 (1.11) | 5.65 (1.35) | 0.86 | 5.53 (1.08) | 5.75 (1.99) | 0.26 |

| Systolic BP, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 144.24 (19.75) | 145.14 (18.68) | 0.41 | 147.55 (19.75) | 148.02 (18.19) | 0.71 | 140.89 (19.20) | 138.45 (18.14) | 0.19 |

| Diastolic BP, mean ± SD, mm Hg | 85.83 (11.18) | 84.57 (11.49) | 0.04 | 85.35 (10.81) | 84.97 (11.56) | 0.60 | 86.31 (11.53) | 83.64 (11.31) | 0.02 |

| Triglycerides, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 1.36 (0.81) | 1.33 (0.77) | 0.57 | 1.45 (0.78) | 1.42 (0.84) | 0.57 | 1.27 (0.83) | 1.13 (0.51) | 0.012 |

| HDL, mean ± SD, mmol/L | 1.46 (0.39) | 1.49 (0.41) | 0.09 | 1.48 (0.37) | 1.51 (0.38) | 0.23 | 1.43 (0.40) | 1.46 (0.48) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 329 (7.81) | 38 (10.41) | 0.08 | 176 (8.29) | 26 (10.20) | 0.30 | 153 (7.32) | 12 (10.91) | 0.16 |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 2174 (51.61) | 199 (54.52) | 0.29 | 1110 (52.28) | 138 (54.12) | 0.58 | 1064 (50.93) | 61 (55.45) | 0.36 |

BMI body mass index; BP blood pressure; HDL high-density lipoprotein; SD standard deviation

a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2

bSystolic BP ≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg or antihypertensive medication

c Blood triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L

d HDL cholesterol < 1.0 mmol/L in men and < 1.3 mmol/L in women

e Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or with a history of diabetes

Table 2 shows the effect estimates (odds ratios, ORs) together with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on the associations of depressive symptoms with MetS and its individual component. We found that depressive symptoms were negatively related to elevated DBP (≥ 85 mm Hg) (crude OR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.6–1.0]) but positively related to elevated FPG (≥ 7.0 mmol/L) (crude OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.03–2.1]). After adjusting for age, gender, education level and marital status, the associations between MetS and depressive symptoms were no longer significant except for the association with elevated FPG (OR = 1.47, 95% CI [1.01–2.1]). This association remained significant even after additionally controlling for other potential confounders (smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary pattern and sleep quality) (OR = 1.50, 95% CI [1.00–2.2]). Furthermore, diabetes was related to the presence of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.50, 95% CI [1.01–2.2]).

Table 2.

Associations of depressive symptoms with metabolic syndrome and its individual component

| Depressive symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Metabolic syndrome | ||

| Model 1 | 1.05 (0.80–1.40) | 0.70 |

| Model 2 | 1.03 (0.80–1.30) | 0.86 |

| Model 3 | 1.02 (0.80–1.30) | 0.87 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | ||

| Model 1 | 0.78 (0.60–1.00) | 0.09 |

| Model 2 | 0.95 (0.70–1.30) | 0.75 |

| Model 3 | 0.97 (0.70–1.30) | 0.86 |

| Systolic BP ≥ 130 mm Hg | ||

| Model 1 | 1.17 (0.90–1.50) | 0.25 |

| Model 2 | 0.84 (0.60–1.10) | 0.22 |

| Model 3 | 0.87 (0.60–1.20) | 0.34 |

| Diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg | ||

| Model 1 | 0.77 (0.60–1.00) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | 0.83 (0.70–1.00) | 0.09 |

| Model 3 | 0.94 (0.70–1.20) | 0.61 |

| Blood triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L | ||

| Model 1 | 0.99 (0.80–1.30) | 0.94 |

| Model 2 | 0.99 (0.80–1.30) | 0.92 |

| Model 3 | 0.98 (0.70–1.30) | 0.87 |

| HDL < 1.0 (men) or < 1.3 mmol/L (women) | ||

| Model 1 | 1.05 (0.80–1.40) | 0.68 |

| Model 2 | 0.90 (0.70–1.20) | 0.42 |

| Model 3 | 0.89 (0.70–1.20) | 0.40 |

| Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L | ||

| Model 1 | 1.47 (1.03–2.10) | 0.04 |

| Model 2 | 1.47 (1.01–2.10) | 0.04 |

| Model 3 | 1.50 (1.00–2.20) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | ||

| Model 1 | 1.37 (0.96–2.00) | 0.08 |

| Model 2 | 1.41 (0.98–2.00) | 0.06 |

| Model 3 | 1.50 (1.01–2.20) | 0.05 |

HDL high-density lipoprotein, BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Model 1, crude model

Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, education level, marital status

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus smoking, alcohol consumption, tea consumption, dietary pattern, sleep quality

Gender might be a possible effect modifier on the relationship between depressive symptoms and DBP (P = 0.026). The gender-specific associations are shown in Table 3. Among women, none of the MetS individual component was related to depressive symptoms. Among men, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with elevated DBP in model 1 (crude OR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.4–0.85]) and model 2 (OR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.4–0.98]), but not in model 3. Additionally, depressive symptoms was associated with elevated SBP (≥ 130 mm Hg) among men in model 2 and 3 (OR = 0.59, 95% CI [0.4–0.9]) but not in model 1.

Table 3.

Associations of depressive symptoms with metabolic syndrome and its individual component by gender

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Metabolic syndrome | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.04 (0.60–1.80) | 0.90 | 0.89 (0.70–1.20) | 0.44 |

| Model 2 | 1.30 (0.70–2.20) | 0.35 | 0.95 (0.70–1.30) | 0.74 |

| Model 3 | 1.49 (0.80–2.70) | 0.19 | 0.85 (0.60–1.20) | 0.36 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.88 (0.50–1.40) | 0.60 | 0.77 (0.50–1.10) | 0.17 |

| Model 2 | 1.06 (0.60–1.70) | 0.82 | 0.90 (0.60–1.30) | 0.59 |

| Model 3 | 1.27 (0.70–2.20) | 0.37 | 0.96 (0.60–1.40) | 0.85 |

| Systolic BP ≥ 130 mm Hg | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.72 (0.50–1.10) | 0.11 | 1.34 (0.90–1.90) | 0.12 |

| Model 2 | 0.59 (0.40–0.90) | 0.01 | 1.08 (0.70–1.60) | 0.70 |

| Model 3 | 0.59 (0.40–0.90) | 0.02 | 1.14 (0.80–1.70) | 0.54 |

| Diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.58 (0.40–0.85) | <0.01 | 0.89 (0.70–1.20) | 0.40 |

| Model 2 | 0.66 (0.40–0.98) | 0.04 | 0.92 (0.70–1.20) | 0.52 |

| Model 3 | 0.77 (0.50–1.16) | 0.22 | 1.03 (0.80–1.40) | 0.83 |

| Blood triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L | ||||

| Model 1 | 0.85 (0.50–1.40) | 0.55 | 0.99 (0.80–1.30) | 0.94 |

| Model 2 | 1.05 (0.60–1.80) | 0.85 | 0.96 (0.70–1.30) | 0.79 |

| Model 3 | 1.04 (0.60–1.90) | 0.88 | 0.92 (0.70–1.20) | 0.57 |

| HDL < 1.0 (men) or < 1.3 mmol/L (women) | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.01 (0.60–1.80) | 0.98 | 0.80 (0.60–1.10) | 0.12 |

| Model 2 | 1.24 (0.70–2.20) | 0.49 | 0.84 (0.60–1.10) | 0.23 |

| Model 3 | 1.21 (0.60–2.30) | 0.56 | 0.83 (0.60–1.10) | 0.23 |

| Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.67 (0.90–3.10) | 0.09 | 1.42 (0.90–2.20) | 0.13 |

| Model 2 | 1.63 (0.90–3.00) | 0.12 | 1.39 (0.90–2.20) | 0.17 |

| Model 3 | 1.48 (0.80–2.90) | 0.26 | 1.56 (0.90–2.60) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Model 1 | 1.55 (0.80–2.90) | 0.17 | 1.26 (0.80–1.90) | 0.30 |

| Model 2 | 1.60 (0.80–3.00) | 0.15 | 1.33 (0.90–2.10) | 0.21 |

| Model 3 | 1.56 (0.80–3.10) | 0.21 | 1.49 (0.90–2.40) | 0.11 |

HDL high-density lipoprotein BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Model 1, crude model

Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, education level, marital status

Model 3 adjusted for model 2 plus smoking, alcohol consumption, tea consumption, dietary pattern, sleep quality

Discussion

Depressive symptoms were not related to MetS in the present sample of Chinese community-dwelling male and female older adults. However, we found that depressive symptoms were associated with MetS components including DBP and FPG and diabetes. In general, the study findings were consistent with the results in a recent meta-analysis of observational studies, which demonstrated that the risk of developing diabetes mellitus in depressive individuals was 1.41 times higher than non-depressive ones [23]. Similar associations were found in a longitudinal study with British elders [24]. In addition, a study of Chinese population also demonstrated that FPG concentration was positively associated with the prevalence of depressive symptoms [25]. Shared pathophysiological mechanisms may exist in depressive symptoms and diabetes such as visceral obesity [26], decreased adiponectin level [27] and cortisol dysregulation from the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [28]. These pathophysiological mechanisms may be complicated with depressive symptoms and lead to insulin resistance and diabetes.

No associations were found between depressive symptoms and MetS as well as MetS components among women, while significant inverse associations were found among men. Different from our study, Scuteri and colleagues showed that women but not men were more likely to have decreased nocturnal SBP when depression was present [29]. Regardless of gender, the relationship between depression and blood pressure is not confirmative. Two cross-sectional studies showed that depressed elders tended to have lower SBP [30] [31]. A prospective study also found that depression was associated with low BP at 22 years of follow-up [32]. However, this finding was not supported by a 4-year follow-up study [33].

The negative association between SBP and depressive symptoms may be explained by several possible mechanisms. First, individuals with depression are more likely to have cardiovascular disease [34, 35] and may take antihypertensive medications to lower BP levels. However, the present study found that the negative association persisted after adjusting the use of antihypertensive medication. Second, the mechanism is related to a somatic-affective symptom-cluster. General weakness, fatigue and inflammatory process caused by chronic low BP may overlap depressive symptoms [30, 36], or potentially induce depressive symptoms. Third, neuropeptide Y might be a possible marker in the relationship between depression and low BP level [37–39].

The null findings among women may due to gender-related differences in the pathogenesis of depression and hormonal factors. Neural mechanisms associated with pathological distortions while experiencing emotion regulation [40]. In addition, estrogens dropped later and less markedly as human age, women may develop cardiovascular diseases later in life [41, 42]. Further studies need to pay attention to the potential gender-related variations in the relationship between depression and cardiometabolic risk factors.

This study has following limitations needed to be noted. First, the cross-sectional design cannot determine the direction of effects between depression symptoms and MetS. Second, participants self-reported the use of antidepressants medications, which was subject to response bias and recall errors. Even though the diagnostic validity of the PHQ-9 was comparable with a clinician-administered instrument [43], participants may have varied capabilities in completing the questionnaire based on their age, education and cognitive function.

Conclusions

This study showed that depressive symptoms were negatively associated with elevated SBP in older men but not women. For older Chinese adults, especially men, increasing family attention to depressive symptoms, regular screening and timely diagnosis of depression, as well as monitoring blood glucose and BP routinely are important from a public health perspective. Further studies are warranted to examine the causality and the potential bidirectional relationships between depressive symptoms and MetS in older adults.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- BP

Blood pressure

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- PHQ-9

Nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire

- BMI

Body mass index

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

Authors’ contributions

J-HL and Y-XQ conducted the statistical analyses and wrote manuscript. Q-HM, H-PS and YX contributed data collection and interpretation of the data. C-WP conceived and designed the study and revised manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Bureau of Xiangcheng District in Suzhou, China under Grant No. XJ201706 and the Health Commission of Suzhou under Grant No. GSWS2019090.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author (Chen-Wei Pan, pcwonly@gmail.com) upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Soochow University. Written inform consent was obtained from each participant at the recruitment stage of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing-Hong Liu and Yu-Xi Qian contributed equally to the work presented here and therefore should be considered equivalent authors

References

- 1.WHO . Depression and other common mental disorders: Global Health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life–systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forlani C, Morri M, Ferrari B, Dalmonte E, Menchetti M, De Ronchi D, Atti AR. Prevalence and gender differences in late-life depression: a population-based study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(4):370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sjoberg L, Karlsson B, Atti AR, Skoog I, Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. Prevalence of depression: comparisons of different depression definitions in population-based samples of older adults. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goncalves-Pereira M, Prina AM, Cardoso AM, da Silva JA, Prince M, Xavier M. The prevalence of late-life depression in a Portuguese community sample: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group study. J Affect Disord. 2018;246:674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stunkard AJ, Faith MS, Allison KC. Depression and obesity. Biol Psychiat. 2003;54(3):330–337. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00608-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viscogliosi G, Andreozzi P, Chiriac IM, Cipriani E, Servello A, Marigliano B, Ettorre E, Marigliano V. Depressive symptoms in older people with metabolic syndrome: is there a relationship with inflammation? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):242–247. doi: 10.1002/gps.3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeBoer MD, Gurka MJ, Woo JG, Morrison JA. Severity of metabolic syndrome as a predictor of cardiovascular disease between childhood and adulthood: the princeton lipid Research Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(6):755–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rethorst CD, Bernstein I, Trivedi MH. Inflammation, obesity, and metabolic syndrome in depression: analysis of the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(12):e1428–e1432. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Block A, Schipf S, Van der Auwera S, Hannemann A, Nauck M, John U, Volzke H, Freyberger HJ, Dorr M, Felix S, et al. Sex- and age-specific associations between major depressive disorder and metabolic syndrome in two general population samples in Germany. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(8):611–620. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2016.1191535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurka MJ, Vishnu A, Okereke OI, Musani S, Sims M, DeBoer MD. Depressive symptoms are associated with worsened severity of the metabolic syndrome in African American women independent of lifestyle factors: a consideration of mechanistic links from the Jackson heart study. Psychoneuro Endocrinol. 2016;68:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekita A, Arima H, Ninomiya T, Ohara T, Doi Y, Hirakawa Y, Fukuhara M, Hata J, Yonemoto K, Ga Y, et al. Elevated depressive symptoms in metabolic syndrome in a general population of Japanese men: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:862. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hildrum B, Mykletun A, Midthjell K, Ismail K, Dahl AA. No association of depression and anxiety with the metabolic syndrome: the Norwegian HUNT study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Zhang DJ, Shao JJ, Qi XD, Tian L. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan CW, Wang X, Ma Q, Sun HP, Xu Y, Wang P. Cognitive dysfunction and health-related quality of life among older Chinese. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17301. doi: 10.1038/srep17301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan CW, Cong XL, Zhou HJ, Wang XZ, Sun HP, Xu Y, Wang P. Evaluating health-related quality of life impact of chronic conditions among older adults from a rural town in Suzhou, China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;76:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badr H, Federman AD, Wolf M, Revenson TA, Wisnivesky JP. Depression in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their informal caregivers. Aging Mental Health. 2017;21(9):975–982. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1186153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Expert Panel on Detection E Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (ncep) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabanayagam C, Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Tan AG, Tai ES, Aung T, Saw SM, Wong TY. Metabolic syndrome components and age-related cataract: the Singapore Malay eye study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2397–2404. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang H, Sun HP, Wang P, Xu Y, Pan CW. Cataract and depressive symptoms among older Chinese adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(12):1479–1484. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu M, Zhang X, Lu F, Fang L. Depression and risk for diabetes: a meta-analysis. Can J Diab. 2015;39(4):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham E, Au B, Schmitz N. Depressive symptoms, prediabetes, and incident diabetes in older english adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(12):1450–1458. doi: 10.1002/gps.4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng YF, Zhong SM, Qin YH. The relationship between major depressive disorder and glucose parameters: a cross-sectional study in a Chinese population. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26(4):665–669. doi: 10.17219/acem/63023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelzangs N, Kritchevsky SB, Beekman AT, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Simonsick EM, Yaffe K, Harris TB, Penninx BW. Depressive symptoms and change in abdominal obesity in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1386–1393. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Campos AC, Miranda AS, Rocha NP, Talib LL, Gattaz WF, Forlenza OV. Reduced serum levels of adiponectin in elderly patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(8):1081–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joseph JJ, Golden SH. Cortisol dysregulation: the bidirectional link between stress, depression, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017;1391(1):20–34. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scuteri A, Spalletta G, Cangelosi M, Gianni W, Assisi A, Brancati AM, Modestino A, Caltagirone C, Volpe M. Decreased nocturnal systolic blood pressure fall in older subjects with depression. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21(4–5):292–297. doi: 10.1007/BF03324918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Licht CM, de Geus EJ, Seldenrijk A, van van Hout HP, Zitman FG, Dyck R, Penninx BW. Depression is associated with decreased blood pressure, but antidepressant use increases the risk for hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;53(4):631–638. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.126698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niu K, Hozawa A, Awata S, Guo H, Kuriyama S, Seki T, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Nakaya N, Ebihara S, Wang Y, et al. Home blood pressure is associated with depressive symptoms in an elderly population aged 70 years and over: a population-based, cross-sectional analysis. Hypertens Res. 2008;31(3):409–416. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildrum B, Romild U, Holmen J. Anxiety and depression lowers blood pressure: 22-year follow-up of the population based HUNT study, Norway. BMC Public health. 2011;11:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shinn EH, Poston WS, Kimball KT, St Jeor ST, Foreyt JP. Blood pressure and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a prospective study. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(7 Pt 1):660–664. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(01)01304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(7):613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Crump C, Burke GL. Cerebrovascular disease and evolution of depressive symptoms in the cardiovascular health study. Stroke. 2002;33(6):1636–1644. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000018405.59799.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marijnissen RM, Smits JE, Schoevers RA, van den Brink RH, Holewijn S, Franke B, de Graaf J, Oude Voshaar RC. Association between metabolic syndrome and depressive symptom profiles–sex-specific? J Affect Disord. 2013;151(3):1138–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michalkiewicz M, Knestaut KM, Bytchkova EY, Michalkiewicz T. Hypotension and reduced catecholamines in neuropeptide Y transgenic rats. Hypertension. 2003;41(5):1056–1062. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000066623.64368.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karl T, Herzog H. Behavioral profiling of NPY in aggression and neuropsychiatric diseases. Peptides. 2007;28(2):326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tikhonoff V, Hardy R, Deanfield J, Friberg P, Kuh D, Muniz G, Pariante CM, Hotopf M, Richards M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression across adulthood and blood pressure in late middle age: the 1946 British birth cohort. J Hypertens. 2014;32(8):1590–1598. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutin AR, Beason-Held LL, Dotson VM, Resnick SM, Costa PT., Jr The neural correlates of Neuroticism differ by sex prospectively mediate depressive symptoms among older women. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barnes JN. Sex-specific factors regulating pressure and flow. Exp Physiol. 2017;102(11):1385–1392. doi: 10.1113/EP086531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kloner RA, Carson C, 3rd, Dobs A, Kopecky S, Mohler ER., 3rd Testosterone and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(5):545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author (Chen-Wei Pan, pcwonly@gmail.com) upon reasonable request.