Abstract

The prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle reflex (ASR), as an index of sensorimotor gating, is one of the most extensively used paradigms in the field of neuropsychiatric disorders. Few studies have examined how prenatal stress (PS) regulates the sensorimotor gating during the lifespan and how PS modifies the development of amyloid-beta (Aβ) pathology in brain areas underlying the PPI formation. We followed alternations in corticosterone levels, learning and memory, and the PPI of the ASR measures in APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F offspring of dams exposed to gestational noise stress. In-depth quantifications of the Aβ plaque accumulation were also performed at 6 months. The results indicated an age-dependent deterioration of sensorimotor gating, long-lasting PS-induced abnormalities in PPI magnitudes, as well as deficits in spatial memory. The PS also resulted in a higher Aβ aggregation predominantly in brain areas associated with the PPI modulation network. The findings suggest the contribution of a PS-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity in regulating the PPI modulation substrates leading to the abnormal development of the neural protection system in response to disruptive stimuli. The long-lasting HPA axis dysregulation appears to be the major underlying mechanism in precipitating the Aβ deposition, especially in brain areas contributed to the PPI modulation network.

Keywords: Acoustic startle reflex, Alzheimer's disease, amyloid-beta plaque, corticosterone, HPA axis, noise, prenatal stress, prepulse inhibition, sensorimotor gating

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which accounts for 60–80% of dementia cases (Cui and Li 2013; Marcello et al. 2015), is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder leading to cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and sensory and physical disabilities (Fiest et al. 2016). The AD’s neuropathological landmarks include the extracellular deposition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide, the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, as well as neuronal and synaptic loss in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Marcello et al. 2015). Even though the complex etiology of AD is not well understood, modifiable risk factors related to lifestyle characteristics, environmental risks, and diseases have been identified as the underlying reasons in 35% of cases (Livingston et al. 2017). Among known modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia, chronic stress has long been recognized in the etiology and pathophysiology of persistent mental and physical health conditions (Pardon 2011; Marcello et al. 2015).

Prenatal stress (PS) or exposure to glucocorticoids during critical periods of brain development has been shown to be associated with an organizational effect on brain structure function and systematically intensifies the risk of developing multiple neuropsychiatric disorders and mental illnesses during the lifespan (Ishii and Hashimoto-Torii 2015; Hoeijmakers et al. 2017; Van den Bergh et al. 2017). Strong evidence from human and non-human studies suggests that dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system modulates the effects of PS and early-life stress on fetal development and birth outcome (Weinstock 2005; Charil et al. 2010; Weinstock 2017; Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019a). The PS can also result in epigenetic variations of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid)-methylation at corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene promoters lasting into adulthood and can even extend to the next generation (Crudo et al. 2012; Bock et al. 2015; Jafari et al. 2019b). The PS has also been shown to be associated with a reduced fetal blood flow and the supply of essential nutrients and oxygen to the fetus through the placenta (Charil et al. 2010; Jafari et al. 2017a), as well as negative effects on the immune system leading to enhanced susceptibility to illness and disease (Weinstock 2008; Trump et al. 2016).

Studies also signify that stress can significantly impact cognitive processing (Jafari et al. 2017b; Jafari et al. 2019b). Stress is known to modulate the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle reflex (ASR), a measure of sensorimotor gating (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016; Shoji et al. 2016). The PPI of the ASR is one of the well-known experimental paradigms in the field of neuropsychiatric disorders (Koch 1999; Ueki et al. 2006; Li et al. 2009). The PPI implies a normal reduction of the amplitude of the startle reflex when a weak prepulse stimulus is presented 30–500 msec before the startling stimulus. Thus, the PPI is used as an index of sensorimotor gating (Rohleder et al. 2014). Studies in humans demonstrate that PPI is modulated by both attentional and emotional responses to prepulse, indicating that this early-stage gating is top-down modulated (Li et al. 2009; De la Casa et al. 2016). Recent experimental evidence also confirms the top-down processing of PPI in laboratory animals (Li et al. 2009; Rohleder et al. 2014). Both human (Perriol et al. 2005; Ueki et al. 2006) and non-human (Wang et al. 2012; Jafari et al. 2019a; Story et al. 2019) studies suggest that the sensorimotor gating is impaired with the progression of AD pathology, and its abnormalities may be linked to cognitive impairment and cerebral Aβ neuropathology (Wang et al. 2012). Generally, impairments in sensorimotor gating have been reported in rodents following stress exposure (Conti and Printz 2003; Kjaer et al. 2010; Hougaard et al. 2011; Bakshi et al. 2012; Jafari et al. 2019a), social isolation (Chang et al. 2015; Bailoo et al. 2016), variation in maternal care (Cromwell and Atchley 2015), or corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) injection (Conti et al. 2002; Bakshi et al. 2012). There are also similar supports in humans subsequent to performing a stressful task (performing a complex task with time restriction) (De la Casa et al. 2016) or cortisol injection (Richter et al. 2011). PPI alternations also have been suggested as a model for exploring information-processing deficits in post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs) (Bakshi et al. 2012), schizophrenia, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders (ADHDs) (Li et al. 2009; Swerdlow et al. 2016).

Several previous findings led us to perform the current experiments. First, the association between PS and later deficits in cognitive behavior and higher vulnerability to adult diseases, which has been shown in both human and rodent models (Charil et al. 2010; Antonelli et al. 2017; Weinstock 2017; Jafari et al. 2019b). Second, Aβ neuropathology that has been suggested as the most known hypothesis underlying cognitive dysfunction among widespread neuropathological deficits contributed to AD pathogenesis (Selkoe and Hardy 2016). Third, alteration in the activity of the maternal and fetal neuroendocrine systems that has been shown as the most likely mechanism for the adverse effects of PS on brain development and increased risk for developing neuropsychiatric and brain diseases in old age (Charil et al. 2010; Antonelli et al. 2017; Weinstock 2017; Jafari et al. 2019b). Few studies, however, have examined the lasting impact of PS on sensorimotor gating, as well as predisposing the development of Aβ pathology in brain areas underlying the PPI formation. Our study was novel in 1) applying a prenatal noise stress paradigm as a lifestyle risk factor for AD common today (Cui and Li 2013; Marcello et al. 2015), 2) probing for life-course alternations in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responsivity and spatial learning and memory, 3) quantifying Aβ deposition in major brain areas that contribute in the PPI of the ASR in rodents (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016), and 4) applying a unique AD mouse model (APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F) that represents a robust age-related spread of Aβ aggregates and cognitive deficits titrated to endogenous levels of APP with no sign of tauopathy (Saito et al. 2014). The knock-in APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mouse is a second-generation mouse model of AD that has a modified APP gene with humanized Aβ. The cortical deposition specifically starts after 2 months and is almost saturated by 7 months. Subcortical amyloidosis is also shown after 4 months (Saito et al. 2014; Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019a). Since APP is not over-produced in human AD, this last point provides an important improvement over earlier Aβ-based mouse models of AD (Sasaguri et al. 2017). Earlier mouse models overexpressed APP or APP-presenilin1 (PS1), which led to the accumulation of unusual fragments generated by α-secretase such as C-terminal fragment-β (CTF-β). CTF-β is more toxic than Aβ and does not accumulate in human AD brains (Saito et al. 2016; Sasaguri et al. 2017). Thus, in this mouse model of AD, we hypothesized that the PS has a strong contribution in regulating the auditory-motor gating and precipitating the development of Aβ pathology in the PPI modulation network.

Material and Methods

Animals

The male and female pairs of AD transgenic mice (with background strain of C57BL/6NJ) carrying Swedish (NL), Arctic (G), and Beyreuther/Iberian (F) mutations (APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F) were provided by RIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan. Then, a colony of APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice was maintained at the Canadian Center for Behavioural Neuroscience. Genotyping of all mice was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using tail snipping method. For the recording of gestational length, a former protocol was followed (Jafari et al. 2017a; Jafari et al. 2017c). Forty female APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice at 8 weeks of age were individually mated with forty male APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice in standard shoe-box cages at 4:00 PM. The female mice were assessed 3 h later at 7:00 PM and the next morning for breeding signs such as sperm plug and red/swollen vaginal opening. If a plug or sperm was present, the female was considered possibly pregnant and removed from the male until the pregnancy was confirmed, and then housed with 2–3 females until 1–2 days before parturition. Once a female was left with a male overnight, she was not paired with a male again until the lack of pregnancy was confirmed. The weight gain of the female mice was followed every day to confirm pregnancy. On gestational day (GD) 11, a weight gain of at least 3.5 g usually signifies conception has occurred. This method allows a determination of the length of gestation with a 0.5-day precision (Jafari et al. 2017d). All litters became pregnant according to this timed pregnancy procedure. Pregnant mice, then, were randomly assigned to either stress (PS) or the control group. At the age of 22–23 days, the pups were weaned from their mothers, and only 1 or 2 male pups were randomly selected from each litter (n = 20 in each group). One litter from the PS group and 2 litters from the control group did not deliver any male pups, so 2 male offspring were randomly chosen from the other dams with multiple males in the same group. In this study, the male pups randomly chosen at the study outset were not housed in the same cage, but each one was located in a separate cage. To preclude the effect of social isolation (being housed individually in separate cages) (Tada et al. 2016; Mumtaz et al. 2018; Viana Borges et al. 2019) on the results, each selected pup was only housed with his 1–2 sex-matched siblings, and these siblings were not considered in this study. We chose to study only the male pups as studies in mice commonly demonstrate no sex effect in PPI of the ASR test (Logue et al. 1997; Willott et al. 2003; Ison and Allen 2007; Jafari et al. 2018a,b). All animals were given access to food and water ad libitum and were maintained on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle. All testing and training was performed during the light phase of the cycle at a fixed time of day by the same examiner. The experimenter was blind to the experimental groups in all measures. The experimental procedures were approved by the University of Lethbridge Animal Care Committee in compliance with the standards set out by the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

Experimental design

We exposed the stress animals to a noise stress paradigm on GDs 12–16 because the corticogenesis process occurs from embryonic days 10–17 in mice, and layers II/III, IV, and V mainly develop during GDs 12–16 (Kolb et al. 2012; Kolb et al. 2013). This timeframe is also consistent with the second trimester of human pregnancy when substantial neural development occurs (Clancy et al. 2007).

Noise stress procedure

The mice were exposed to the noise stress as previously described (Jafari et al. 2017d; Jafari et al. 2018b). Briefly, on GDs 12, 14, and 16, the mice (n = 20) in groups of 2–3 in their standard cage were moved to a sound chamber specified for the stress group. The noise stress paradigm consisted of an intermittent 3000 Hz frequency sound of 90 dB SPL for 1 s duration and 15 s interstimulus interval (ISI) for 24 h starting at 8:00 AM. A speaker, which emitted the noise stimulus, was placed inside the cage. The sound pressure level was monitored daily inside the cage without an animal (Tektronix RM3000, Digital Phosphor Oscilloscope). We used a 3000-Hz frequency tone because (a) it is audible by mice (Heffner and Heffner 2007) and (b) it is relatively similar to environmental and traffic noises that are largely made up of low- to mid-frequency tones (Jafari et al. 2018a). We also applied an intermittent stimulus intensity to preclude the likelihood of noise-induced hearing loss. Twenty-four hours of rest after each noise exposure was also enough time for recovery from possible temporary threshold shifts (White et al. 1998).

Control group

On GDs 12, 14, and 16 pregnant mice (n = 20), which were housed in groups of 2–3 in their standard cage, were moved with their home cages to a sound chamber specified for the control group. A silent speaker was placed inside the cage. The mice were left undisturbed for 24 h starting at 8:00 AM. In the control group, no stress was given (Jafari et al. 2018a,b).

Plasma corticosterone assay

Blood was taken from the submandibular vein at 7:30–8:30 AM at ages 2, 6, 12, and 18 months (Fig. 1). Approximately 0.1 mL of blood was collected in heparin-coated tubes. The tubes were centrifuged at 6000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 m to collect the plasma. Collected plasma samples were stored at −80 °C and then analyzed as formerly described (Jafari et al. 2018a,b).

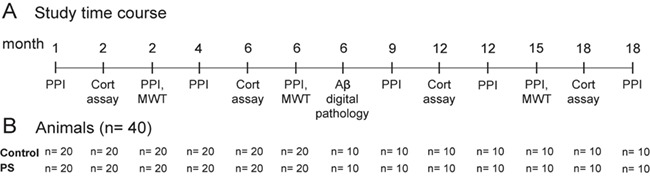

Figure 1.

(A) Time of each procedure across age in APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F offspring. (B) The number of animals per procedure. The PPI of the ASR was performed 8 times at ages 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 months for APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice. To keep track long-lasting effects of PS on corticosterone levels and spatial learning and memory, blood was collected 4 times at ages 2, 6, 12, and 18 months, and the MWT was performed 3 times at 2, 6, and 15 months. Half of the animals were sacrificed at 6 months, and digital pathology by Nanozoomer was performed to quantify the total number of Aβ plaques, total plaque area (%), plaque area in specific brain regions, and the plaque size (μm). Aβ, amyloid beta; ASR, acoustic startle reflex; Cort, corticosterone; MWT, Morris water task; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition, PS, prenatal stress.

Behavioral tests

We administered the PPI of the ASR test 8 times at 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months, which was close to the timelines previously reported in related longitudinal studies in mice (van den Buuse et al. 2003; Ouagazzal et al. 2006; Shoji et al. 2016). We did not perform the Morris water task (MWT) in similar times as the PPI of the ASR test, however, because it was a long training protocol (8-day acquisition trials and a probe trial a day afterward) and previous studies demonstrated that periodic cognitive enrichment throughout aging, via multiple learning trials in MWT, can improve the memory performance of AD mice (Martinez-Coria et al. 2015). This improvement in cognitive reserve also has strong supports in human studies (Fratiglioni and Wang 2007; Kelly et al. 2014; Chapman et al. 2015).

Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex

A former protocol was followed (Jafari et al. 2018a,b; Jafari et al. 2019a) to perform the PPI of the ASR at ages 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months (Fig. 1). Each mouse was placed in a plastic cylinder situated on a plate with a pressure sensor in an acoustic chamber (PANLAB Harvard Apparatus). Any animal motion was detected by the sensor, which measured its amplitude and stored data on a computer hard drive. Software generated a sequence of stimulus trials including a startle stimulus, a prepulse stimulus, and a startle stimulus paired with a prepulse stimulus in a white background noise of 65 dB. The ASR stimulus was an 8-kHz tone frequency with a 115-dB intensity, a 40-ms duration, and a 1-ms rise/fall time. The prepulse stimulus was also an 8-kHz tone frequency with an 80-dB intensity, a 20-ms duration, and a 1-ms rise/fall time, which was presented 100 ms before the startle stimulus. The testing session was started with an acclimation period lasting for 3 min. Then the animals received 10 startle-only trials to habituate their startle responses to a steady state level. Immediately afterward, forty trials including 10 “no stimulus,” 10 “pulse stimulus,” 10 “prepulse stimulus,” and 10 “prepulse + pulse stimulus” were presented in pseudo-random order with a 30-s ISI. The PANLAB system automatically presented the amplitude and latency of the ASR and PPI in an Excel data spreadsheet. The ASR amplitude, the ASR latency (latency in “pulse stimulus” or “pulse alone” trials), the PPI ratio, and the PPI latency (latency in “prepulse + pulse stimulus” trials) (Swerdlow et al. 1995) were between the 2 groups. The PPI ratio was calculated by subtracting the ASR amplitude from the PPI amplitude divided by the ASR amplitude.

The MWT

The MWT was conducted at ages 2, 6, and 15 months with an alternating order of animals (Fig. 1). The water task consisted of a pool (153 cm in diameter) filled with water (23–25 °C) up to a level of ~15 cm from the top edge of the tank. The water was made opaque by non-toxic white tempera paint. The pool was located in a room rich with distal cues. During all hidden platform trials, the platform was submerged ~1.0 cm under the surface of the water. The tank was divided virtually into 4 quadrants, with starting points at north, west, east, and south. Animals were trained with 4 trials per day for 8 consecutive days (Water2100 Software vs.7, 2008). Each trial began with the mouse being placed in the pool in a pseudo-random sequence at 1 of the 4 cardinal compass positions around the perimeter of the pool. Testing was stopped after the mouse reached the platform or if the mouse did not find the platform, at the 60-s trial time limit. Data were recorded using an automated tracking system (HVS Image, Hampton, UK). The swim time (sec), swim speed (m/s), and swim distance (m) were calculated for analysis. The probe trial was also carried out on the ninth day, 24 h after the last acquisition trial, in which the platform was removed, and each mouse was allowed to swim freely for 60 s. The time spent in the quadrant where the platform had been located was measured (Jafari et al. 2018a,b).

Quantification of the Aβ plaque area

The Aβ quantifications were performed at 6 months (10 mice per group), because the Aβ aggregation is age-dependent in the knock-in APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice showing a significant overexpression in the whole brain at 6 months (Saito et al. 2014; Jafari et al. 2018b). We also elected 6 brain sections for quantifications because they generally encompassed all specific brain areas associated with the PPI of the ASR formation (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016).

Methoxy-X04 injection and brain imaging

Methoxy-X04 is a fluorescent that has high specificity in staining Aβ plaques in post-mortem sections of AD brain. The Methoxy-X04 solution was prepared by dissolving the Methoxy into a solution containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 45% propylene glycol, and 45% sodium phosphate buffered saline. Twenty-four hours prior to perfusion, mice were weighed and given an intraperitoneal injection of methoxy-X04 at a dose of 10 mg/kg of body weight (Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019a). Then they were euthanized via a transcardiac perfusion of 0.9% saline followed by paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brains were removed and post-fixed for 24 h in PFA (Jafari et al. 2018a). They were subsequently sliced at 50 μm using a Cryostat, and every second section was mounted on glass slides. Brain sections were automatically imaged in a ×40 magnification (resolution: 0.23 μm/pixel) using the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer 2.0-HT Scan System (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan) for quantification of Aβ plaques.

Brain sections and regions of interests

For each brain, 6 coronal sections (AP ~2.96, 0.098, −2.06, −2.92, −4.48, and −5.34 mm) corresponding with a mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001) were selected for Aβ plaque quantifications, that is, total plaque area (%), total number of plaques, and the largest plaque size (Figs 3 and 4). In each brain section, plaque area (%) was also computed for some specific brain regions that studies have shown their contribution in the functional network of the PPI formation (Li et al. 2009; Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016). The PPI of the ASR response consists of 3 brain circuits: 1) a startle pathway (caudal pontine reticular nucleus [PnC], ventrolateral tegmental nucleus [VLTg], and cochlear nuclei [CN]); 2) a PPI mediation network (inferior colliculus [IC], pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus [PPTg], and superior colliculus [SC]); and 3) a PPI modulation network (frontal cortex area [FrA], prelimbic cortex [PrL], anterior cingulate cortex [Cg1&2], hippocampus region [Hipp], parasubiculum [PaS], basolateral amygdala [BLA], nucleus accumbens [Ncb], ventral tegmental area [VTA], and primary auditory cortex [Au1]) (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016). Studies have shown the contribution of the PPI modulation network in the progression of AD pathology, stress handling, or in the regulation of brain cognitive processes (Sara 2009; Schoenfeld and Gould 2012; Kim et al. 2015; Saar et al. 2015,Jafari et al. 2019b). To determine the plaque area, each brain section was uploaded in ImageJ 1.4.3.67 software, and the total plaque area and also plaque area of the regions of interest (ROI) were measured via using required image processing options under “Edit,” “Image,” “Process,” and “Analyze” tabs. These 6 coronal sections (A1–A6) were chosen for the Aβ plaque quantification as they provided an appropriate view to discriminate selected ROI’s boundaries (Jafari et al. 2018a).

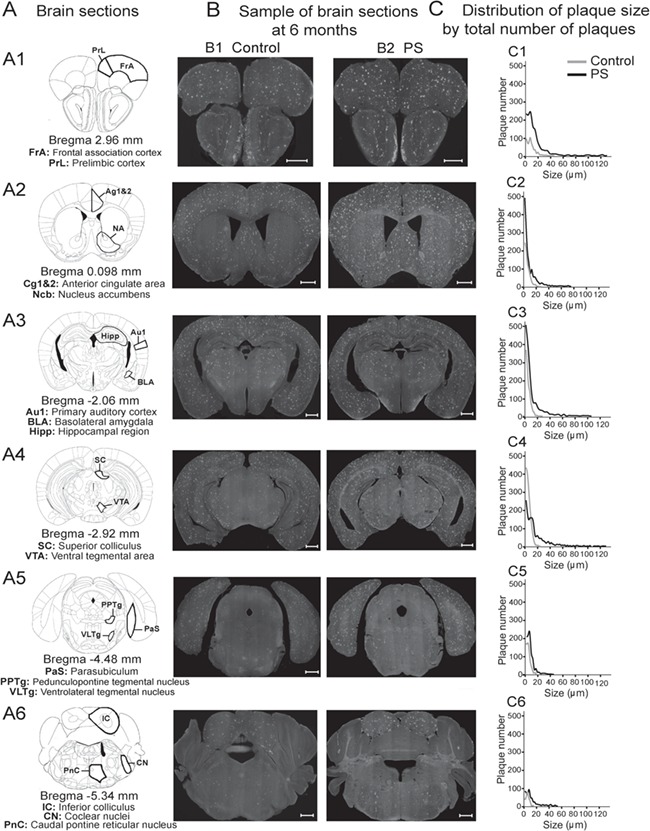

Figure 3.

The Aβ plaque quantifications at 6 months. (A) Six coronal sections (A1–A6: Bregma ~2.96, 0.98, −2.06, −2.92, −2.92, −4.48, and −5.34 mm) were selected for quantifying the Aβ plaques. (B) Samples of brain sections used in a control (B1) and a PS (B2) animal. (C) Their corresponding distributions of plaque size (μm) by the total number of plaques (C1–C6). Scale bar, 0.5 ml. Aβ, amyloid beta; Au1, primary auditory cortex; BLA, basolateral amygdala; Cg1&2, anterior cingulate area; CN, cochlear nuclei; FrA, frontal cortex area; Hipp, hippocampal region; IC, inferior colliculus; Ncb, nucleus accumbens; PaS, parasubiculum; PnC, caudal pontine reticular nucleus; PPTg, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; PrL, prelimbic cortex; PS, prenatal stress; SC, superior colliculus; VLTg, ventrolateral tegmental nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

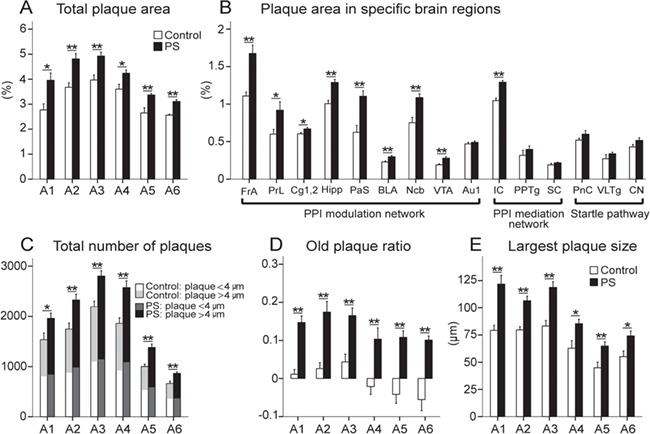

Figure 4.

The PS effect on Aβ aggregation at 6 months. The PS group showed a significant increase in total plaque area (A), plaque area in specific brain regions (B), total number of plaques (C), old plaque ratio (D), and largest plaque size (E) in 6 brain sections (A1–A6) selected for statistical analyses. Among 15 specific brain regions chosen for detailed comparisons in brain areas associated with the PPI of the ASR formation, a significantly larger plaque area was observed in all brain areas associated with the PPI modulation network, except for Au1. No significant difference was, however, shown in brain regions linked to both PPI mediation network and startle pathway, except for IC from the PPI mediation network. Results reported as mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Aβ, amyloid beta; Au1, primary auditory cortex; BLA, basolateral amygdala; Cg1&2, anterior cingulate area; CN, cochlear nuclei; FrA, frontal cortex area; Hipp, hippocampal region; IC, inferior colliculus; Ncb, nucleus accumbens; PaS, parasubiculum; PnC, caudal pontine reticular nucleus; PPTg, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; PrL, prelimbic cortex; PS, prenatal stress; SC, superior colliculus; VLTg, ventrolateral tegmental nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

The Ilastik 1.1.7 software was used for quantifying the total number of plaques in each brain section (Jafari et al. 2018b). This software presents the number of plaques as well as the plaque size corresponding with each discrete plaque. The number of plaques was also quantified according to the plaque size (a radius of less than or more than 4 μm). Studies indicate that 87% of newly formed plaques are small in size having a radius of <4μm (Hefendehl et al. 2011). In each brain section, the average of the 3 largest plaques was also considered as the largest plaque size (Jafari et al. 2019a).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 24.0 at a significance level of 0.05 or better. Data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) test. Given the normal distribution of data in all measures (P ≥ 0.084), parametric statistical tests were applied for data analysis. Univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the 2 groups regarding different parameters of the corticosterone assay, behavioral tests, and Aβ plaque measurements. To balance a similar number of animals at all ages in multiple comparisons throughout age, we compared the animals for which we had the complete data for all time points. A Linear Mixed Effect Model was conducted to compare the 2 groups by considering age as a covariate, the interaction of age and treatment, and a random effect of litter on the corticosterone levels and behavioral tests. The F values, P values, estimations of the effect size (partial η2), and observed power were reported for the statistical analyses. A bivariate correlational analysis was also applied to test the relationship between behavioral test results and Aβ plaque measures at 6 months. Adjustments for multiple comparisons within model for the post hoc tests were performed with Bonferroni correction.

Results

The PS impact on corticosterone levels

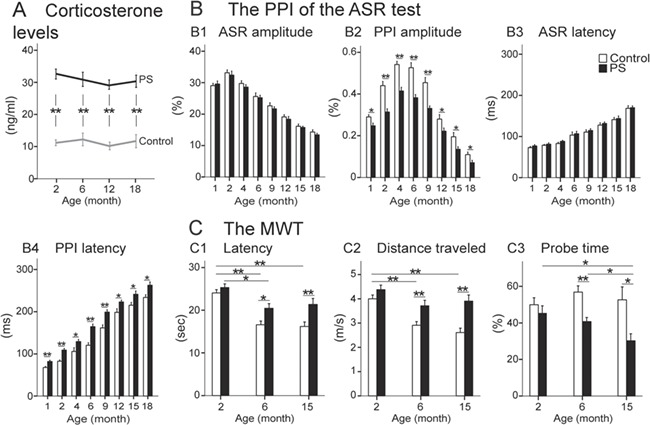

Significantly higher corticosterone levels were observed in the PS animals compared with the controls in all measures at 2 (F1,38 = 138.690, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.914, power = 1.00), 6 (F1,38 = 38.237, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.732, power = 1.00), 12 (F1,38 = 100.191, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.909, power = 1.00), and 18 (F1,38 = 47.377, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.725, power = 1.00) months. The difference between the 2 groups (F1,76 = 234.741, P ≤ 0.001) was also significant by considering age a covariate. The interaction of age and group was not significant (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Results of corticosterone assays and behavioral tests. (A) The corticosterone levels (ng/ml): the corticosterone level was significantly higher in the PS group compared with the control group over age. The PPI of the ASR test: (B1) The ASR amplitude (%) significantly decreased by age in both groups. (B2) The PS animals exhibited a significantly lower PPI amplitude (%) than the controls across age. (B3,B4) The ASR and PPI latencies (msec) significantly increased by age in both groups, and the difference between the 2 groups in PPI latency was significant within age. The MWT: The PS animals demonstrated impairments in swim latency (C1) and swim distance (C2) than the control animals at 6 and 15 months. (C3) The probe test: The PS animals displayed a significant impairment in probe time at older ages, 6 and 15 months, than the controls. Results reported as mean ± S.E.M. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ASR, acoustic startle reflex; MWT, Morris water task; PPI, pre-pulse inhibition; PS, prenatal stress.

The PS impact on behavioral tests

The PPI of the ASR

The highest ASR amplitude (%) at 2 months gradually decreased by age in both groups, and no significant difference was observed between the 2 groups (Fig. 2B1). The largest PPI amplitude (%) was shown at 4 months. The PPI amplitude gradually deteriorated by age in both groups, and it was significantly lower in the PS group compared with the control group at all ages (1 month: F1,38 = 6.016, P = 0.017, η2 = 0.090, power = 0.675; 2 months: F1,38 = 20.430, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.300, power = 0.993; 4 months: F1,38 = 26.418, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.350, power = 0.999; 6 months: F1,38 = 22.249, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.363, power = 0.996; 9 months: F1,18 = 22.192, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.381, power = 0.997; 12 months: F1,18 = 4.799, P = 0.038, η2 = 0.167, power = 0.558; 15 months: F1,18 = 6.666, P = 0.016, η2 = 0.217, power = 0.698; 18 months: F1,18 = 4.960, P = 0.032, η2 = 0.160, power = 0.573) (Fig. 2B2). The difference between the 2 groups (F1,152 = 385.861, P ≤ 0.001) and the interaction of age and group (F2,152 = 23.976, P ≤ 0.001) were also significant in the PPI amplitude by considering age a covariate.

Whereas the age-dependent increase in ASR latency (msec) was similar in both groups (Fig. 2B3), the PPI latency (msec) was significantly longer in PS animals compared to the controls within the lifespan (1 month: F1,38 = 12.371, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.150, power = 0.931; 2 months: F1,38 = 17.312, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.282, power = 0.983; 4 months: F1,38 = 5.304, P = 0.026, η2 = 0.101, power = 0.616; 6 months: F1,38 = 23.860, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.405, power = 0.997; 9 months: F1,18 = 16.961, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.320, power = 0.980; 12 months: F1,18 = 6.305, P = 0.020, η2 = 0.215, power = 0.672; 15 months: F1,18 = 6.175, P = 0.018, η2 = 0.231, power = 0.701; 18 months: F1,18 = 5.272, P = 0.032, η2 = 0.193, power = 0.593) (Fig. 2B4). The difference between the 2 groups (F1,152 = 101.180, P ≤ 0.001) and the interaction of age and group (F2,152 = 195.739, P ≤ 0.001) were also significant in the PPI latency by considering age a covariate.

The MWT

Swim latency to find the hidden platform was significantly longer at 6 (F1,38 = 5.945, P = 0.012, η2 = 0.028, power = 0.701) and 15 (F1,38 = 8.602, P = 0.004, η2 = 0.033, power = 0.834) months in the PS animals compared with the control group (Fig. 2C1,C2). The same results were observed in the distance traveled (6 months: F1,38 = 8.962, P = 0.003, η2 = 0.030, power = 0.856; 15 months: F1,18 = 15.654, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.071, power = 0.998), whereas the swim speed was similar in both groups (P ≥ 0.302). By including age as covariate, the difference between the 2 groups in both swim latency (F1,1917 = 38.166, P ≤ 0.001) and distance traveled (F1,1917 = 29.463, P ≤ 0.001) and the interaction of age and group (swim latency: F2,1917 = 16.042, P ≤ 0.001; distance traveled: F2,1917 = 14.829, P ≤ 0.001) were also significant.

The PS group also exhibited a significantly shorter probe time at ages 6 and 15 months compared with the control group (6 months: F1,38 = 11.085, P = 0.005, η2 = 0.442, power = 0.872; 15 months: F1,18 = 6.186, P = 0.028, η2 = 0.401, power = 0.623) (Fig. 2C3). The difference between the 2 groups (F1,57 = 54.978, P ≤ 0.001) and the interaction of age and group (F2,57 = 4.713, P = 0.011) were also significant by including age a covariate.

To ensure that the subset sampling was not biased, we also compared the 2 groups of animals within ages 1–6 months who were euthanized at 6 months for Aβ digital pathology. The findings were consistent with the results presented for the first half of the animals who were not killed, and we had their complete data for all time points. Thus, the difference between the 2 groups in corticosterone levels (F1,36 = 83.046, P ≤ 0.001), the PPI amplitude (F1,76 = 66.732, P ≤ 0.001; age*group interaction: F2,76 = 42.344, P ≤ 0.001), the PPI latency (F1,76 = 34.009, P ≤ 0.001; age*group interaction: F2,76 = 29.253, P ≤ 0.001), the swim latency (F1,1279 = 71.579, P ≤ 0.001; age*group interaction: F2,1279 = 13.033, P ≤ 0.001), the distance traveled (F1,1279 = 52.931, P ≤ 0.001; age*group interaction: F2,1279 = 8.295, P ≤ 0.001), and the probe time (F1,36 = 64.913, P ≤ 0.001) were significant by considering age a covariate.

Impact of the PS on the Aβ plaque development

At the age of 6 months, Aβ plaques were observed in all brain sections for both groups (Fig. 3A,B). The distribution of plaque size by total number of plaques has been presented for samples of brain sections in a control and a stressed animal (Fig. 3C). Total plaque area (%) was significantly larger in all brain sections in the PS group compared with the control group (A1: F1,18 = 8.011, P = 0.016, η2 = 0.421, power = 0.732; A2: F1,18 = 14.898, P = 0.003, η2 = 0.575, power = 0.939; A3: F1,18 = 14.328, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.578, power = 0.943; A4: F1,18 = 7.506, P = 0.019, η2 = 0.406, power = 0.704; A5: F1,18 = 9.641, P = 0.009, η2 = 0.598, power = 0.884; A6: F1,18 = 37.892, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.996, power = 1.00) (Fig. 4A). Among 15 specific brain regions chosen for detailed comparisons in brain areas associated with the PPI of the ASR formation (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016), a significantly larger plaque area was observed in all brain areas associated with the PPI modulation network in the PS animals compared with the controls, that is, FrA (F1,18 = 15.711, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.588, power = 0.949), PrL (F1,18 = 5.487, P = 0.038, η2 = 0.337, power = 0.577), Cg1&2 (F1,18 = 6.491, P = 0.027, η2 = 0.271, power = 0.641), Hipp (F1,18 = 21.318, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.660, power = 0.987), PaS (F1,18 = 16.838, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.605, power = 0.961), BLA (F1,18 = 17.616, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.616, power = 0.967), Ncb (F1,18 = 12.711, P = 0.005, η2 = 0.518, power = 0.812), and VTA (F1,18 = 13.651, P = 0.004, η2 = 0.512, power = 0.911) (Fig. 4B) except for Au1 (P = 0.444). No significant difference was shown, however, in brain regions linked to both PPI mediation network and startle pathway, that is, PPTg, SC, PnC, VLTg, and CN except for IC (F1,18 = 36.620, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.769, power = 1.00) from the PPI mediation network.

The PS caused a significant increase in the number of plaques in all brain sections (A1: F1,18 = 6.425, P = 0.028, η2 = 0.369, power = 0.637; A2: F1,18 = 11.573, P = 0.006, η2 = 0.512, power = 0.872; A3: F1,18 = 16.070, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.595, power = 0.953; A4: F1,18 = 16.039, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.593, power = 0.953; A5: F1,18 = 18.897, P = 0.001, η2 = 0.632, power = 0.976; A6: F1,18 = 15.317, P = 0.002, η2 = 0.583, power = 0.945). Figure 4C demonstrates the total number of plaques divided by plaque size less than or more than 4 μm radius in both groups. The number of plaques larger than 4 μm was significantly higher in the PS animals than the controls in all section (A1: F1,18 = 9.903, P = 0.008, η2 = 0.487, power = 0.832; A2: F1,18 = 45.753, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.806, power = 1.00; A3: F1,18 = 29.249, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.727, power = 0.998; A4: F1,18 = 44.803, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.803, power = 1.00; A5: F1,18 = 31.625, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.999, power = 0.976; A6: F1,18 = 34.526, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.758, power = 1.00). Identically, the old plaque ratio was significantly larger in the PS group compared to the controls (A1: F1,18 = 39.034, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.900, power = 1.00; A2: F1,18 = 19.181, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.839, power = 1.00; A3: F1,18 = 17.713, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.617, power = 0.969; A4: F1,18 = 11.076, P = 0.007, η2 = 0.502, power = 0.857; A5: F1,18 = 27.414, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.714, power = 0.997; A6: F1,18= 27.935, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.717, power = 0.998) (Fig. 4D). The PS also led to the formation of larger plaque sizes in all brain sections (A1: F1,18 = 18.870, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.631, power = 0.970; A2: F1,18 = 24.698, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.692, power = 0.994; A3: F1,18 = 22.230, P = 0.001, η2 = 0.669, power = 0.990; A4: F1,18= 8.117, P = 0.016, η2 = 0.425, power = 0.737; A5: F1,18 = 9.587, P = 0.009, η2 = 0.501, power = 0.841; A6: F1,18 = 7.801, P = 0.017, η2 = 0.415, power = 0.720) (Fig. 4E).

Correlation between Aβ plaque area measures and behavioral findings

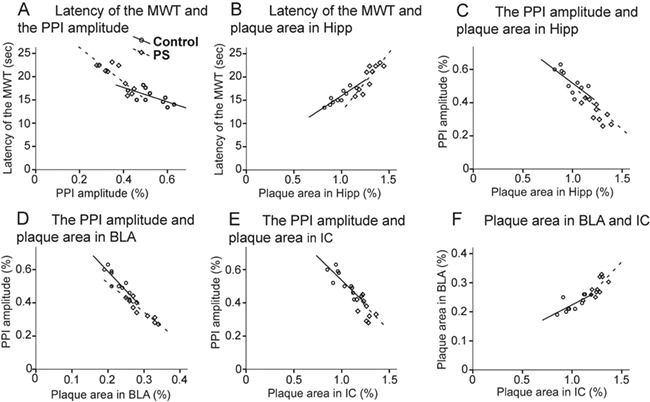

All possible bivariate correlations between behavioral measures including 1) the latency in MWT (sec) (the average of latency for each animal during a course of an 8-day training) and 2) the PPI amplitude (%), as well as Aβ quantifications including the plaque area (%) in 1) Hipp (Bregma ~−2.06), 2) BLA (Bregma ~−2.06), and 3) IC (Bregma ~−5.34) were determined at 6 months. In each group, there was a significant negative relationship between the latency in MWT and PPI amplitude (PS: r = −0.766, P = 0.010; control: r = −0.698, P = 0.028; Fig. 5A), a significant positive relationship between the latency in MWT and the Hipp plaque area (PS: r = 0.901, P ≤ 0.001; control: r = 0.927, P ≤ 0.001; Fig 5B), a significant negative relationship between the PPI amplitude and the Hipp plaque area (PS: r = −0.889, P = 0.001; control: r = −0.789, P = 0.011; Fig 5C), a significant negative relationship between the PPI amplitude and the BLA plaque area (PS: r = −0.708, P = 0.023; control: r = −0.877, P = 0.001; Fig 5D), a significant negative relationship between the PPI amplitude and the IC plaque area (PS: r = −0.678, P = 0.032; control: r = −0.898, P = 0.001; Fig 5E), and a significant positive relationship between the BLA plaque area and the IC plaque area (PS: r = 0.730, P = 0.017; control: r = 0.711, P = 0.019; Fig 5F).

Figure 5.

Bivariate correlations between behavioral findings (the latency in MWT and the PPI magnitude) and brain measures (plaque area in Hipp [Bregma ~−2.06], BLA [Bregma ~−2.0], and IC [Bregma ~−5.34]). Relationships were observed between (A) the latency in MWT and the PPI amplitude (B) the latency in MWT and the Hipp plaque area, (C) the PPI amplitude and the Hipp plaque area, (D) the PPI amplitude and the BLA plaque area, (E) the PPI amplitude and the IC plaque area, and (F) the BLA plaque area and the IC plaque area in both PS (⋄) and control ( ) groups. BLA, basolateral amygdala; Hipp, hippocampal region; IC, inferior colliculus; MWT, Morris water task; PS, prenatal stress; PPI, prepulse inhibition.

) groups. BLA, basolateral amygdala; Hipp, hippocampal region; IC, inferior colliculus; MWT, Morris water task; PS, prenatal stress; PPI, prepulse inhibition.

Discussion

The main findings were 1) a PS-modulated long-lasting dysregulation of the HPA axis; 2) age-dependent changes in PPI of the ASR measures with enduring PS-induced abnormalities in PPI measures; 3) a PS-modulated spatial learning and memory deficit with greater impacts in older ages; 4) an elevated Aβ plaque deposition (in aspects of plaque area, plaque number, and plaque size) in the PS animals compared with the controls at 6 months; 5) a PS-induced larger Aβ aggregation in brain areas associated with the PPI modulation network; and 6) statistical relationships between behavioral test results and Aβ plaque measures at 6 months. We consider these findings in turn.

Long-lasting dysregulation of the HPA axis in PS offspring

We followed alternations in corticosterone levels during the lifespan for all animals. The PS animals displayed a significantly higher corticosterone level compared to the controls at all ages (2, 6, 12, and 18 months). The pattern of the long-lasting HPA axis hyperactivity in PS offspring was identical to what was already reported in their mothers (Jafari et al. 2018b). Our findings were consistent with current evidence suggesting that the dysregulation of the maternal and fetal HPA axes resulted from a repeated gestational stress as the most likely mechanism for an enduring PS-induced glucocorticoid hypersecretion (Weinstock 2005; Charil et al. 2010; Weinstock 2017). The CRH is synthesized by the placenta and released into the maternal and fetal blood flow during pregnancy. This placental CRH activity is regulated by the maternal HPA axis (Jafari et al. 2019b). The long-lasting maternal HPA axis hyperactivity produced by a repeated gestational stress leads to an elevated production and release of placental CRH into the blood flow, which in turn modulates the hippocampal function and integrity (Charil et al. 2010). This chronic HPA axis hyperactivity also modifies other parahippocampal and limbic areas prolific of CRH receptors in both mothers and offspring that studies have shown their contribution to mood disorders, anxiety, aggression, and impulsivity disorders (Jafari et al. 2019b). The PS also affects hippocampal mineralocorticoids and GRs involved in the negative feedback loop that inhibits the hormonal stress response and restores the system to a constant state (Huizink et al. 2004; Weinstock 2005).

Life-course PS-induced abnormalities in PPI measures

PPI refers to the ability of a weak prestimulus to reduce the startle response to a loud stimulus presented instantly after the prestimulus (Bakshi et al. 2012). Both ASR and PPI are age dependent representing the highest ASR amplitude at 2 months and the largest PPI magnitude at 4 months in mice (Shoji et al. 2016; Jafari et al. 2018a,b). In our study, proportionate changes in ASR amplitude in both groups over age showed similar hearing levels in the 2 groups. The C57BL/6NJ mouse strain (the background strain of APPNL-G-F/NL-G-F mice) exhibits a significant hearing loss compared to CBA/CaJ mouse strain for 32 kHz auditory brainstem response thresholds by 6 months of age and for 16 kHz thresholds by 12 months (Kane et al. 2012). In our study, the ASR age-related changes for 8 KHz threshold was observed at 6 months, which was consistent with the results already reported for C57BL/6NJ mice (Shoji et al. 2016; Jafari et al. 2018a). The ASR latency also exhibited identical age-dependent increments in both groups. The PS animals, however, were different in PPI measures compared to the controls indicating a significant deterioration of the PPI amplitude and also a longer PPI latency during the lifespan. Impaired PPI magnitudes suggested a PS-induced deficiency in detecting the prepulse stimulus, which is the landmark of impairment in sensorimotor gating. Whereas previous studies confirm disruption in sensorimotor gating subsequent to stress exposure (Conti and Printz 2003; Kjaer et al. 2010; Hougaard et al. 2011; Bakshi et al. 2012; Jafari at al. 2019a) or CRF injection (Conti et al. 2002; Bakshi et al. 2012) in rats, and also as an outcome of performing a stressful task (De la Casa et al. 2016) or cortisol injection (Richter et al. 2011) in humans due to enhanced HPA axis responsivity, little evidence exists regarding the PS effects. In our study, the lasting PS-induced dysregulation of the HPA axis appears to be the major mechanism underlying the enduring disruption of the PPI during the lifespan. Contrary to earlier studies that proposed the PPI reflects the function of a pre-attentional sensory buffer (Koch 1999), current studies demonstrate the modulation of the PPI with both attentional and emotional responses to prepulse in humans, thus implicating that this early-stage gating is top-down modulated (Li et al. 2009). Animal studies also confirm top-down modulation of PPI (Rohleder et al. 2016) showing an increase in PPI amplitude by auditory fear conditioning (Li et al. 2008; Du et al. 2009).

There are also a few studies reporting the PPI latency, and the existing evidence is likewise truly controversial. For instance, whereas prolonged latency and increased amplitude of PPI was suggested in the patients with first-episode schizophrenia (Song et al. 2014), an increase in ASR latency and reduced PPI latency was interpreted as a profound disruption of sensorimotor gating in patients with Huntington’s disease (Swerdlow et al. 1995). Thus, it seems that little information exists regarding alternations in PPI latency in both health and disease, and further studies are suggested to clarify how the latency of the PPI is changing in neurodevelopmental disorders and neuropsychiatric diseases in both humans and rodent models.

Enduring PS-induced impairments in spatial learning and memory

A significantly longer latency and shorter probe time in the correct quadrant in PS animals than the controls, especially in older ages, indicated a PS-induced deficit in spatial learning and memory. Extensive evidence suggests that the PS-created HPA axis hyperactivity 1) downregulates receptors in the hippocampus, the hypothalamus, and the pituitary or adrenal glands; 2) reduces the sensitivity of the receptors at any of these levels; 3) modifies the CRH levels or affinity of plasma binding proteins (Huizink et al. 2004); and 4) leads to impairments in cognitive performance (Kim et al. 2015). Among brain neurotransmitter systems, the PS has also been shown to increase hippocampal acetylcholine release, inhibit the influence of cholinergic receptors on the activity of the HPA axis, downregulate hippocampal GRs, and modulate the memory and learning abilities of the offspring (Huizink et al. 2004; Charil et al. 2010). PS is also associated with alterations of dopamine receptor systems that contribute to the control of cognition, affect, and locomotion (Huizink et al. 2004). Appropriate development and survival of dopaminergic, GABAergic, cholinergic, and serotonergic neurons are also dependent on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is expressed in the hippocampus (Autry and Monteggia 2012). Studies indicate that the PS-induced impairment in memory is associated with a reduction in BDNF mRNA in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of rodents (Ratajczak et al. 2015).

PS resulted in an elevated Aβ accumulation

Whereas an age-dependent Aβ accumulation was shown in all brain sections in both groups, a significant adverse effect of PS was observed in different Aβ plaque measures including total Aβ plaque area, plaque size, and also total number of plaques with a significant superiority for larger plaque sizes (>4 μm radius) in the PS animals. The results were quite similar to the findings already reported for mothers of these offspring (Jafari et al. 2018b). Our findings in PS-induced overproduction of Aβ plaques demonstrate the impact of PS in accelerating the development of neuropathological landmarks of the progression of AD. Whereas the reduced synapse number is likely the strongest quantitative neuropathological correlate of the AD (Selkoe and Hardy 2016), experimental studies imply that soluble oligomers of Aβ42 impair synapse number, hamper long-term potentiation, and enhance long-term synaptic depression in rodent hippocampus, and injecting them into healthy rats impairs memory (Shankar et al. 2008). Recent evidence also indicates the contribution of chronic stress in modulating amyloid pathways leading to the accelerated development of Aβ pathology in transgenic mouse models (Pardon 2011). Studies in AD mice suggest that exposure to a repeated stress during adulthood can result in a significant increase in Aβ soluble oligomers, accelerate Aβ aggregation (Cuadrado-Tejedor et al. 2012; Marcello et al. 2012), impair neurotrophic signaling (Rothman et al. 2012), elevate hippocampal levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (Cui et al. 2015), create a progressive loss of hippocampal synapses (Marcello et al. 2012), and lead to dysfunction of the memory networks (Baglietto-Vargas et al. 2015). Three months of isolation stress (Kang et al. 2007) and chronic pharmacological elevation of glucocorticoid levels using the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone (Green et al. 2006) have also been found to elevate brain soluble and insoluble amyloid levels. PS studies also indicate the association between an elevated hippocampal soluble Aβ (Martisova et al. 2013) and the increased susceptibility of offspring to cognitive impairment (Fang et al. 2018).

PS led to a larger Aβ aggregation in brain areas linked to the PPI modulation network

The PPI is a neuropsychological process demonstrating impairments in several neurological diseases (Kohl et al. 2013). In addition to brain areas mediating startle and PPI, which are located within the brain stem, there are also cortico-limbic areas that modulate the PPI-mediation (Swerdlow et al. 2001). In this study, we aimed to explore how PS modulates the Aβ aggregation in different levels of the neural circuitries underpinning the PPI of the ASR formation. Thus, according to a recent model suggested for the functional network of brain circuitries participating in PPI of the ASR (Rohleder et al. 2014; Rohleder et al. 2016), the Aβ plaque aggregation was compared between the PS and control animals in brain areas associated with 1) the startle pathway (CN, PnC, and VLTg); 2) the PPI mediation network (IC, SC, and PPTg); and 3) the PPI modulation network (FrA, PrL, Cg 1&2, Hipp, Pas, BLA, Ncb, VTA, AU1). A PS-induced larger Aβ accumulation was observed in all brain areas linked to the PPI modulation network (except for Au1) as well as IC from the PPI mediation circuitry. This finding suggests that the PS impacts brain areas underlying the PPI modulation network compared to the brain regions participate in PPI mediation and startle pathway. The major effect of PS on brain areas associated with cognitive processes was consistent with the previous studies demonstrating the detrimental influence of a chronic stress on frontal cortex (Arnsten 2009), hippocampal region (Kim et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2015), anterior cingulate area (Maviel et al. 2004), cortical and amygdala areas (Roozendaal et al. 2004; Oliveira et al. 2012), and nucleus accumbens (Setlow 1997), as well as the interaction of these brain areas in accelerating the development of AD (Ueki et al. 2006; Radley et al. 2015; Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019a). The PS also caused a significant Aβ deposition in IC. Among the hearing nuclei of the auditory pathway, the IC plays a major role in the synchronized processing of auditory stimuli (Jafari and Malayeri 2016; Omidvar et al. 2018). Studies have shown that stress alters gene expression in IC (Mazurek et al. 2012) and can negatively influence stimulus transmission and integration associated with cognition in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex (Manikandan et al. 2006).

According to the “protection-of-processing” theory for justifying the function of PPI, a weak prepulse stimulus preceded by an intense stimulus can stimulate not only the information processing for the prepulse signal but also the gating mechanism that dampens the information of the intense disruptive inputs (e.g., intense loud sound). The PPI, thus, protects the early processing of the prepulse signal from interference by disturbed stimuli (Swerdlow et al. 2001; Li et al. 2009). In humans, applying an “attention-to-prepulse” paradigm (task-based protocol) or using an affective/emotional stimulus as the prepulse leads to a larger PPI than no task condition or using emotionally neutral prepulse stimuli (Bradley et al. 2006). Rodent studies also affirm the enhancement of PPI by auditory fear conditioning, which is induced by precisely pairing the prepulse stimulus with foot shock (Li et al. 2008; Li et al. 2009; Cromwell and Atchley 2015). These findings suggest that the PPI is top-down modulated (Li et al. 2009; De la Casa et al. 2016). Ample human studies in schizophrenic patients and subjects with ADHD and also animal models of studying schizophrenia suggest deficient attentional modulation of PPI, as well as impaired top-down processing in regulating sensorimotor gating (Li et al. 2009; Swerdlow et al. 2016). In line with these studies, our findings indicate the lasting role of the HPA axis dysregulation in modifying the brain circuitry underlying the development of the neural protection system to dampen the information of the intense disruptive inputs in PS offspring. For instance, studies indicate the disruptive role of the startle reflex on cognitive performance in humans and learned lever-pressing paradigms in rats (Li et al. 2009). The findings also signify that an enduring HPA hyperactivity accelerates Aβ pathology in brain regions often associated with the PPI modulation network. The contribution of these brain areas underlying cognitive processes also has been shown in dementia (Ueki et al. 2006; Radley et al. 2015; Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019b). Thus, our findings suggest that the PPI of the ASR is a sensitive experimental paradigm to identify early changes and follow subsequent deteriorations in PPI in the course of the development of AD, as well as the effect of exposure to prenatal or early-life adverse experiences.

In view of emotional or affective aspects of AD, whereas human studies demonstrate deficits in facial and prosodic emotional recognition, the severity of cognitive deficit, or the strong verbal or memory requirement of the task applied, often complicates the interpretation of emotional effects of AD (Bucks and Radford 2004). Recent human PPI findings suggest that the effect of positive and negative emotions is different among younger compared to older adults (Le Duc et al. 2016). Studies of sensorimotor gating in animal AD models also support the contribution of aversive stimuli in subserving emotional expression or regulation (Li et al. 2009; Webber et al. 2013). This finding stands for the conditions that PPI may alter without a major contribution of the cognition. For instance, the temporal properties of fear conditioning, which is highly aversive to animals, could allow for a rapid influence on vigilance and attention processes. This aversive state might reflect a major modulatory role of inhibitory gating of the amygdala on brainstem reflexive responses in filtering aversive stimuli (Cromwell et al. 2005; Webber et al. 2013). PPI is also resilient to changes in predictability (a possible cognitive–emotive functional intersection) that could help to understand how sensorimotor gating is modified by negative emotions (Webber et al. 2013). Studies also demonstrate that the release of stress hormones or other neurotransmitters, which may not directly affect the PnC, can modify neuronal transmission in other substrates of the PPI pathway (Koch 1999). For example, a dysregulated maternal HPA axis leads to excess production and release of placental CRH that in turn influences the hippocampus as well as other parahippocampal and limbic areas associated with mood, anxiety, aggression, and impulsivity disorders in offspring (Wadhwa et al. 2004). Overall, considering current evidence that indicates maternal stressors in rodents can replicate some of the behavioral abnormalities observed in humans during the lifespan (Weinstock 2017), it is likely that applying a PPI paradigm with different levels of predictability may help to develop an understanding of the mechanisms underlying changes in affective processes by PS that predispose the individual to the risk of cognitive decline and AD (Plappert et al. 2005). Taken together, future studies on emotional modulation of the PPI might lead to better ways at understanding AD or predicting AD progression, especially in the field of modifiable risk factors of AD, like prenatal or early life stressors.

In our study, the correlational analysis demonstrated relationships between the latency of the MWT and both PPI amplitude and Hipp plaque area: the PPI amplitude and plaque area in Hipp, BLA, and IC and also plaque area in BLA and IC in each group. The findings suggest that whereas both behavioral and pathological measures were worse in the PS mice than the controls, the behavioral results and Aβ quantifications were related in each group. This finding was similar with the result previously reported for the mothers of these offspring (Jafari et al. 2018b) and was consistent with the past publications on the relationship between the PPI and MWT in rats (Oliveras et al. 2015) and humans (Scholes and Martin-Iverson 2009). It was suggested that the relationship between PPI and MWT findings is likely mediated by common attentional processes underlying their regulation (Scholes and Martin-Iverson 2009). Our correlational findings, however, require to be replicated and further explored in future neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies.

In respect of the sex differences in PPI of the ASR, most evidence shows larger amplitudes in males compared to females in both humans (Abel et al. 1998; Swerdlow et al. 1999; Kumaria et al. 2003) and rats (Koch 1998; Lehmann et al. 1999). It was suggested that this sex effect largely results from the impact of reproductive hormones on brain substrates regulating PPI (Koch 1998; Swerdlow et al. 1999; Kumaria et al. 2003). In contrast, most studies with mice do not replicate this sex effect in different strains of mice (Logue et al. 1997; Willott et al. 2003; Ison and Allen 2007; Jafari et al. 2018a). In our study, thus, only the male mice were included.

In this study, we did not run a second Aβ analysis at older ages in view of the saturation of the cortical Aβ deposition by almost 7 months in our knock-in APP mouse model (Saito et al. 2014; Jafari et al. 2018b; Jafari et al. 2019a). We suggest, however, that future research consider older ages to monitor any possible changes in Aβ accumulation during the lifespan. Wild-type littermates also were not included in this study. Whereas exposure to stress has been previously reported to impair cognitive performance in wild-type mice, the combination of stress with a genetic risk factor (overexpression of APP) could aggravate the cognitive deficit (Marcello et al. 2015). It is suggested, therefore, that future research investigates how PS modulates APP metabolism also in healthy aging, as in wild-type mice. We also only periodically measured the corticosterone levels to demonstrate the PS effect on HPA axis during the lifespan. Future studies likewise should measure the CRH, GRs, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels more systematically across ages to provide further evidence for the dysregulation of the neuroendocrine system in response to PS. Similarly, we suggest that future studies investigate baseline immune activity, and immune system alternations resulted by PS, as well as life-course changes in phosphorylated tau in cortical and subcortical brain areas, especially in brain regions contributing in PPI regulation.

Conclusion

This was the first study in AD mice that aimed to identify how PS modifies auditory-motor gating during the lifespan and how PS modulates the Aβ development in brain areas associated with the PPI formation. Our findings demonstrated age-dependent changes in the PPI of the ASR measures with enduring PS-induced abnormalities in PPI magnitudes and also in spatial learning and memory. Aβ quantifications suggested a PS-induced higher Aβ aggregation mostly in brain areas associated with the PPI modulation network. The findings indicate that the PS-induced long-lasting dysregulation of the HPA axis impairs the development of the neural protection system in response to disruptive stimuli by modulating the sensorimotor gating. The enduring HPA axis hyperactivity can also predispose the Aβ development in brain areas largely associated with the PPI modulation network that regulates cognitive processes. The PPI of the ASR is a sensitive experimental paradigm that we suggest be applied in future research to develop knowledge regarding the contribution of prenatal stressors or early life detriments in regulating neural networks underlying cognitive processes and precipitating the risk of cognitive impairment and AD.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant no. 390930); Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery grant no. 40352); Alberta Innovates (Chair; grant no. 43568); Alberta Alzheimer Research Program (grant nos. PAZ15010 and PAZ17010); Alzheimer Society of Canada (grant no. 43674 to M.H.M.); and Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (grant no. 33033 to B.K.).

Notes

We would like to acknowledge Gerlinde A.S. Metz for using her laboratory equipment (PANLAB Harvard Apparatus) for the PPI of the ASR test, Jogender Mehla for helping to do the corticosterone assay, Di Shao for animal husbandry, and Takashi Saito and Takaomi Saido from RIKEN Brain Science Institute for providing the AD mice used in this study. This study was part of a postdoctoral fellowship to Z.J. in Canadian Center for Behavioral Neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge.

Author contributions

Z.J., B.E.K., and M.H.M. conceived and designed the method and prepared and reviewed the manuscript. Z.J. performed experimental work and data analysis. M.H.M. and B.E.K. provided project leadership.

References

- Abel K, Waikar M, Pedro B, Hemsley D, Geyer M. 1998. Repeated testing of prepulse inhibition and habituation of the startle reflex: a study in healthy human controls. J Psychopharmacol. 12:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli MC, Pallares ME, Ceccatelli S, Spulber S. 2017. Long-term consequences of prenatal stress and neurotoxicants exposure on neurodevelopment. Prog Neurobiol. 155:21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. 2009. Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 10:410–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry AE, Monteggia LM. 2012. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 64:238–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglietto-Vargas D, Chen Y, Suh D, Ager RR, Rodriguez-Ortiz CJ, Medeiros R, Myczek K, Green KN, Baram TZ, LaFerla FM. 2015. Short-term modern life-like stress exacerbates Abeta-pathology and synapse loss in 3xTg-AD mice. J Neuroch. 134:915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailoo JD, Varholick JA, Garza XJ, Jordan RL, Hintze S. 2016. Maternal separation followed by isolation-housing differentially affects prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in C57BL/6 mice. Dev Psychobiol. 58:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Alsene KM, Roseboom PH, Connors EE. 2012. Enduring sensorimotor gating abnormalities following predator exposure or corticotropin-releasing factor in rats: a model for PTSD-like information-processing deficits? Neuropharmacology. 62:737–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock J, Weinstock T, Braun K, Segal M. 2015. Stress in utero: prenatal programming of brain plasticity and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 78:315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Codispoti M, Lang PJ. 2006. A multi-process account of startle modulation during affective perception. Psychophysiology. 43:486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucks RS, Radford SA. 2004. Emotion processing in Alzheimer's disease. Aging Ment Health. 8:222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Hsiao YH, Chen YW, Yu YJ, Gean PW. 2015. Social isolation-induced increase in NMDA receptors in the hippocampus exacerbates emotional dysregulation in mice. Hippocampus. 25:474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman SB, Aslan S, Spence JS, Hart JJJ, Bartz EK, Didehbani N, Keebler MW, Gardner CM, Strain JF, DeFina LF. 2015. Neural mechanisms of brain plasticity with complex cognitive training in healthy seniors. Cereb Cortex. 25:396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charil A, Laplante DP, Vaillancourt C, King S. 2010. Prenatal stress and brain development. Brain Res Rev. 65:56–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Finlay BL, Darlington RB, Anand KJ. 2007. Extrapolating brain development from experimental species to humans. Neurotoxicology. 28:931–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti LH, Murry JD, Ruiz MA, Printz MP. 2002. Effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response in two rat strains. Psychopharmacology. 161:296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti LH, Printz MP. 2003. Rat strain-dependent effects of repeated stress on the acoustic startle response. Behav Brain Res. 144:11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell HC, Anstrom K, Azarov A, Woodward DJ. 2005. Auditory inhibitory gating in the amygdala: single-unit analysis in the behaving rat. Brain Res. 1043:12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell HC, Atchley RM. 2015. Influence of emotional states on inhibitory gating: animals models to clinical neurophysiology. Behav Brain Res. 276:67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crudo A, Petropoulos S, Moisiadis VG, Iqbal M, Kostaki A, Machnes Z, Szyf M, Matthews SG. 2012. Prenatal synthetic glucocorticoid treatment changes DNA methylation states in male organ systems: multigenerational effects. Endocrinology. 153:3269–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado-Tejedor M, Ricobaraza A, Frechilla D, Franco R, Perez-Mediavilla A, Garcia-Osta A. 2012. Chronic mild stress accelerates the onset and progression of the Alzheimer's disease phenotype in Tg2576 mice. J Alzheimer's Dis. 28:567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui B, Li K. 2013. Chronic noise exposure and Alzheimer disease: is there an etiological association? Med Hypotheses. 81:623–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui B, Li K, Gai Z, She X, Zhang N, Xu C, Chen X, An G, Ma Q, Wang R. 2015. Chronic noise exposure acts cumulatively to exacerbate Alzheimer's disease-like amyloid-beta pathology and neuroinflammation in the rat hippocampus. Sci Rep. 5: 12943:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Casa LG, Mena A, Ruiz-Salas JC. 2016. Effect of stress and attention on startle response and prepulse inhibition. Physiol Behav. 165:179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Li J, Wu X, Li L. 2009. Precedence-effect-induced enhancement of prepulse inhibition in socially reared but not isolation-reared rats. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 9:44–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Li H, Chang L, Song Y, Ma L, Lu L, Du Z, Li Y, Liu J, Wu Y. 2018. Prenatal stress induced gender-specific alterations of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit expression and response to Abeta in offspring hippocampal cells. Behav Brain Res. 336:182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiest KM, Roberts JI, Maxwell CJ, Hogan DB, Smith EE, Frolkis A, Cohen A, Kirk A, Pearson D, Pringsheim T. 2016. The prevalence and incidence of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 43(Suppl 1):S51–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. 2007. Brain reserve hypothesis in dementia. J Alzheimer's Dis. 12:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KN, Billings LM, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. 2006. Glucocorticoids increase amyloid-beta and tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 26:9047–9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefendehl JK, Wegenast-Braun BM, Liebig C, Eicke D, Milford D, Calhoun ME, Kohsaka S, Eichner M, Jucker M. 2011. Long-term in vivo imaging of beta-amyloid plaque appearance and growth in a mouse model of cerebral beta-amyloidosis. J Neurosci. 31:624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner HE, Heffner RS. 2007. Hearing ranges of laboratory animals. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 46:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers L, Ruigrok SR, Amelianchik A, Ivan D, van Dam AM, Lucassen PJ, Korosi A. 2017. Early-life stress lastingly alters the neuroinflammatory response to amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Brain Behav Immun. 63:160–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hougaard KS, Mandrup KR, Kjaer SL, Bogh IB, Rosenberg R, Wegener G. 2011. Gestational chronic mild stress: effects on acoustic startle in male offspring of rats. Int J Deve Neurosci. 29:495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Mulder EJ, Buitelaar JK. 2004. Prenatal stress and risk for psychopathology: specific effects or induction of general susceptibility? Psychol Bull. 130:115–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S, Hashimoto-Torii K. 2015. Impact of prenatal environmental stress on cortical development. Front Cell Neurosci. 9:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison JR, Allen PD. 2007. Pre- but not post-menopausal female CBA/CaJ mice show less prepulse inhibition than male mice of the same age. Behav Brain Res. 185:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Faraji J, Mirza Agha B, Metz GAS, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2017a. The adverse effects of auditory stress on mouse uterus receptivity and behaviour. Sci Rep. 7:4720:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2017b. Effect of acute stress on auditory processing: a systematic review of human studies. Rev Neurosci. 28:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2018a. Chronic traffic noise stress accelerates brain impairment and cognitive decline in mice. Exp Neurol. 308:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2019b. Noise exposure accelerates the risk of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: adulthood, gestational, and prenatal mechanistic evidence from animal studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Malayeri S. 2016. Subcortical encoding of speech cues in children with congenital blindness. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 34:757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Mehla J, Afrashteh N, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2017c. Corticosterone response to gestational stress and postpartum memory function in mice. PLoS One. 12:e0180306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Mehla J, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2017d. Prenatal noise stress impairs HPA axis and cognitive performance in mice. Sci Rep. 7: 10560:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Mehla J, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2018b. Gestational noise stress augments postpartum β-amyloid pathology and cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Cereb Cortex. 1–13, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari Z, Okuma M, Karem H, Mehla J, Kolb BE, Mohajerani MH. 2019a. Prenatal noise stress aggravates β-amyloid pathology and cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 77:66–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane KL, Longo-Guess CM, Gagnon LH, Ding D, Salvi RJ, Johnson KR. 2012. Genetic background effects on age-related hearing loss associated with Cdh23 variants in mice. Hear Res. 283:80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JE, Cirrito JR, Dong H, Csernansky JG, Holtzman DM. 2007. Acute stress increases interstitial fluid amyloid-beta via corticotropin-releasing factor and neuronal activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:10673–10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly ME, Loughrey D, Lawlor BA, Robertson IH, Walsh C, Brennan S. 2014. The impact of cognitive training and mental stimulation on cognitive and everyday functioning of healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 15:28–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Pellman B, Kim JJ. 2015. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. 22:411–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Lee HJ, Welday AC, Song E, Cho J, Sharp PE, Jung MW, Blair HT. 2007. Stress-induced alterations in hippocampal plasticity, place cells, and spatial memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:18297–18302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer SL, Wegener G, Rosenberg R, Lund SP, Hougaard KS. 2010. Prenatal and adult stress interplay–behavioral implications. Brain Res. 1320:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. 1998. Sensorimotor gating changes across the estrous cycle in female rats. Physiol Behav. 64:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. 1999. The neurobiology of startle. Prog Neurobiol. 59:107–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl S, Heekeren K, Klosterkotter J, Kuhn J. 2013. Prepulse inhibition in psychiatric disorders--apart from schizophrenia. J Psychiat Res. 47:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Mychasiuk R, Muhammad A, Gibb R. 2013. Brain plasticity in the developing brain. Prog Brain Res. 207:35–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Mychasiuk R, Muhammad A, Li Y, Frost DO, Gibb R. 2012. Experience and the developing prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(Suppl 2):17186–17193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaria V, Grayb JA, Guptaa P, Luschera S, Sharmac T. 2003. Sex differences in prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response. Pers Individ Dif. 35:733–742. [Google Scholar]

- Le Duc J, Fournier P, Hebert S. 2016. Modulation of Prepulse inhibition and startle reflex by emotions: a comparison between young and older adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 8:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Pryce CR, Feldon J. 1999. Sex differences in the acoustic startle response and prepulse inhibition in Wistar rats. Behav Brain Res. 104:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Du Y, Li N, Wu X, Wu Y. 2009. Top-down modulation of prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in humans and rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 33:1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Ping J, Wu R, Wang C, Wu X, Li L. 2008. Auditory fear conditioning modulates prepulse inhibition in socially reared rats and isolation-reared rats. Behav Neurosci. 122:107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J. 2017. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 390:2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue SF, Owen EH, Rasmussen DL, Wehner JM. 1997. Assessment of locomotor activity, acoustic and tactile startle, and prepulse inhibition of startle in inbred mouse strains and F1 hybrids: implications of genetic background for single gene and quantitative trait loci analyses. Neuroscience. 80:1075–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan S, Padma MK, Srikumar R, Jeya Parthasarathy N, Muthuvel A, Sheela Devi R. 2006. Effects of chronic noise stress on spatial memory of rats in relation to neuronal dendritic alteration and free radical-imbalance in hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 399:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello E, Epis R, Saraceno C, Di Luca M. 2012. Synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 970:573–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello E, Gardoni F, Di Luca M. 2015. Alzheimer's disease and modern lifestyle: what is the role of stress? J Neurochem. 134:795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Coria H, Yeung ST, Ager RR, Rodriguez-Ortiz CJ, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM. 2015. Repeated cognitive stimulation alleviates memory impairments in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Brain Res Bull. 117:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martisova E, Aisa B, Guerenu G, Ramirez MJ. 2013. Effects of early maternal separation on biobehavioral and neuropathological markers of Alzheimer's disease in adult male rats. Curr Alzheimer Res. 10:420–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maviel T, Durkin TP, Menzaghi F, Bontempi B. 2004. Sites of neocortical reorganization critical for remote spatial memory. Science. 305:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek B, Haupt H, Klapp BF, Szczepek AJ, Olze H. 2012. Exposure of Wistar rats to 24-h psycho-social stress alters gene expression in the inferior colliculus. Neurosci Lett. 527:40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz F, Khan MI, Zubair M, Dehpour AR. 2018. Neurobiology and consequences of social isolation stress in animal model-a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 105:1205–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira M, Rodrigues AJ, Leao P, Cardona D, Pego JM, Sousa N. 2012. The bed nucleus of stria terminalis and the amygdala as targets of antenatal glucocorticoids: implications for fear and anxiety responses. Psychopharmacology. 220:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveras I, Rio-Alamos C, Canete T, Blazquez G, Martinez-Membrives E, Giorgi O, Corda MG, Tobena A, Fernandez-Teruel A. 2015. Prepulse inhibition predicts spatial working memory performance in the inbred Roman high- and low-avoidance rats and in genetically heterogeneous NIH-HS rats: relevance for studying pre-attentive and cognitive anomalies in schizophrenia. Front Behav Neurosci. 9:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omidvar S, Mahmoudian S, Khabazkhoob M, Ahadi M, Jafari Z. 2018. Tinnitus impacts on speech and non-speech stimuli. Otol Neurotol. 39:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouagazzal AM, Reiss D, Romand R. 2006. Effects of age-related hearing loss on startle reflex and prepulse inhibition in mice on pure and mixed C57BL and 129 genetic background. Behav Brain Res. 172:307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardon MC. 2011. Therapeutic potential of some stress mediators in early Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol. 46:170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. 2001. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perriol MP, Dujardin K, Derambure P, Marcq A, Bourriez JL, Laureau E, Pasquier F, Defebvre L, Destee A. 2005. Disturbance of sensory filtering in dementia with Lewy bodies: comparison with Parkinson's disease dementia and Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 76:106–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plappert CF, Rodenbucher AM, Pilz PK. 2005. Effects of sex and estrous cycle on modulation of the acoustic startle response in mice. Physiol Behav. 84:585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radley J, Morilak D, Viau V, Campeau S. 2015. Chronic stress and brain plasticity: mechanisms underlying adaptive and maladaptive changes and implications for stress-related CNS disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 58:79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak P, Kus K, Murawiecka P, Slodzinska I, Giermaziak W, Nowakowska E. 2015. Biochemical and cognitive impairments observed in animal models of schizophrenia induced by prenatal stress paradigm or methylazoxymethanol acetate administration. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 75:314–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]