Abstract

Research has begun to examine the consequences of paternity leave, focusing primarily on whether paternity leave-taking increases father involvement. Yet, other consequences of paternity leave-taking have not been considered using U.S data. This study uses longitudinal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study to examine whether fathers’ time off from work after the birth of a child is associated with relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality. We also consider whether these relationships are mediated by father involvement. Results suggest that fathers’ time off of work after a birth and length of time off are each positively associated with relationship quality and coparenting quality one year after a child’s birth. They are also positively associated with trajectories of relationship quality and coparenting quality over the first five years after birth. Father involvement at least partially mediates these relationships. Overall, this study suggests that the potential benefits of fathers’ time off of work after the birth of a child may extend beyond father involvement and may improve parental relationships.

Expectations for fathering now encompass becoming an engaged, nurturing parent. Yet, traditional expectations emphasizing the importance of breadwinning roles for fathers continue to persist (Gerson 2010; Marsiglio and Roy 2012). As such, pressures to adhere to breadwinning norms may limit the amount of time that fathers spend sharing in household and childcare tasks with mothers, which may contribute to lower parental relationship quality and lower parental well-being (Aumann, Galinsky, and Matos 2011; Carlson, Hanson, and Fitzroy 2016; Gerson 2010; Jacobs and Gerson 2004).

One policy that may help to alleviate conflicts between traditional and contemporary fathering expectations is paternity leave (Galinsky, Aumann, and Bond 2011; Marsiglio and Roy 2012). Paternity leave often refers to workplace policies that allow, and protect the rights of, fathers who take a leave of absence from work due to the arrival of a new child (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel 2007; Pragg and Knoester 2017). Yet, others may classify any time taken off of work for a child’s birth (even if a formal leave policy is not used) as paternity leave. Regardless of how leave is taken, paternity leave enables fathers to maintain a breadwinning role; it may also allow fathers to focus on developing parenting skills and coparenting relationships immediately after the birth of a child, which may help to facilitate greater father involvement and a more equitable division of domestic labor (Huerta et al. 2014; Rehel 2014).

Paternity leave is associated with more frequent father involvement and higher levels of well-being among European mothers (Bratberg and Naz 2014; Haas and Hwang 2008; Huerta et al. 2014; Pragg and Knoester 2017; Sejourne et al. 2012). However, studies have yet to consider how paternity leave (and related increases in father involvement) may influence parental relationships. This question has important implications for understanding work-family balance, gender inequality, and family well-being. For example, younger cohorts increasingly believe that egalitarian romantic relationships are ideal, and evidence suggests that egalitarianism is associated with higher quality, more generous, and more stable relationships relative to couples who adhere to traditional gender roles (Carlson et al. 2016; Coon Sells and Ganong 2017; Gerson 2010; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015; Stanik and Bryant 2012; Wilcox and Dew 2016). Yet, many relationships are unable to live up to these egalitarian ideals, as workplace norms and public policies constrain individuals into adhering to traditional gender norms (Gerson 2010; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015). Paternity leave is one policy that may alleviate some of these constraints, enable couples to pursue egalitarian ideals by providing fathers time to invest in their family life, and consequently strengthen couple relationships.

In the present study, we focus on reports of fathers’ time off work after the birth of a child and their associations with mothers’ reports of parental relationships in the five years following a child’s birth. We use longitudinal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCW). The FFCW follows a cohort of children born in large U.S. cities and subsequently includes disproportionately disadvantaged families (i.e., high percentages of low-SES families, racial/ethnic minority families, and families that experience union transitions). Although data limitations prevent a definitive focus on the implications of utilizing paternity leave policies per se, we assess whether taking time off of work after the birth of a child and how much time fathers take off are associated with mothers’ reports of parental relationship quality, fathers’ relationship support, and fathers’ coparenting quality. We then examine whether these associations are mediated by father involvement.

Conceptual Framework

The focus of our study is on the implications of fathers taking time off of work after the birth of a child for three distinct, albeit related, dimensions of parental relationships. Relationship quality refers to a universal rating of the quality of the mother-father relationship. Relationship support refers to the extent to which mothers are supported emotionally and are respected for their thoughts. Coparenting quality indicates the extent to which fathers live up to expectations and cooperate in coparenting responsibilities. We draw on role theory to frame our understanding of how fathers’ time off work after childbirth might be related to parental relationships (Goode 1960; Hecht 2001). In particular, role theory points to how the addition of a new child might lead to role conflict (i.e., stress from multiple roles conflicting—such as parent/worker/partner) and role overloads (i.e., stress from too many role responsibilities, which may include role conflict) (Cowan et al. 1985; Hecht 2001; Yavorsky, Kamp Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan 2015). Relatedly, role conflict and role overload can lead to declines in relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality (Hecht 2001; Twenge, Campbell, and Foster 2003).

Parental Relationships After the Arrival of a New Child

Having a child is stressful and requires substantial effort and attention, as infants rely on their parents for emotional, social, and physical care (Waldfogel 2006). Thus, becoming a parent (or having additional children) may create additional roles, increasing the likelihood of experiencing role conflicts and overloads and potentially contributing to greater conflicts and stress (Goode 1960; Twenge et al. 2003). Indeed, on average, parental relationship quality declines after having a child, and this decline is more pronounced among mothers (Cowan et al. 1985; Dew and Wilcox 2011; Keizer and Schenk 2012; Twenge et al. 2003). Such declines are largely attributable to the challenging and frequently changing roles that accompany the arrival of a new child.

To manage role conflicts and overloads, parents may prioritize specific roles. Thus, despite rising egalitarianism, parenthood is often associated with role traditionalization (Cowan et al. 1985; Yavorsky et al. 2015). That is, mothers tend to spend more time in childcare and housework; fathers tend to spend more time in paid labor and contribute relatively less time to domestic labor. This is particularly true for low-income fathers who are more likely to work multiple and/or inflexible jobs and nonstandard hours than more advantaged parents (Williams 2010). Role traditionalization often results in greater stress for mothers as they become primarily responsible for domestic tasks while still often maintaining roles in the paid labor force (Cowan et al. 1985; Twenge et al. 2003; Yavorsky et al. 2015).

Role traditionalization also contributes to lower relationship quality among mothers (Cowan et al. 1985; Dew and Wilcox 2011; Twenge et al. 2003; Wilcox and Nock 2006). This is largely due to mothers perceiving the division of domestic labor (i.e., housework and childcare) as unfair, although the dynamics may depend on parents’ gender ideologies (Dew and Wilcox 2011; Milkie et al. 2002; Newkirk, Perry-Jenkins, and Sayer 2017). Yet, even after accounting for gender ideologies, mothers’ expectations about what the division of household labor should be are often not met as fathers are not participating in domestic tasks to the extent that mothers feel they should be (McClain and Brown 2017; Yavorsky et al. 2015).

Increasingly, both women and men espouse egalitarian ideals and desire to share in both domestic and paid labor (Gerson 2010; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015), and egalitarianism is associated with higher relationship quality (Carlson et al. 2016; Carlson, Miller, and Sassler 2018; Frisco and Williams 2003). As such, policies and practices that promote egalitarianism may improve parental relationships.

Fathers’ Time Off Work Following a Birth and Parental Relationships

Despite widespread evidence of increased egalitarianism, cultural practices, public policies, and workplace expectations largely reinforce traditional gender roles (Pedulla and Thébaud 2015). For example, women earn less money than men, experience discrimination, and suffer an additional wage penalty for motherhood whereas fatherhood is associated with a wage premium (England et al. 2016; Killewald 2013). These economic differences coupled with a cultural pressure for women to engage in intensive mothering places women at a significant disadvantage (Hays 1996). Moreover, national and workplaces policies in the U.S. provide limited assistance for maintaining work-family balance, and such policies are often only available to higher SES individuals (Albiston and O’Connor 2016; Winston 2014). Policies that may empower parents to live up to their egalitarian ideals, such as paternity leave, may improve parental relationships (McClain and Brown 2017; Newkirk et al. 2017; Schober 2012). However, these possibilities have not yet been adequately examined, empirically.

New fatherhood ideals encourage men to be actively involved in their children’s lives, but pressures to fulfill provider roles, especially when becoming a parent, persist (Aumann et al. 2011; Marsiglio and Roy 2012). Paternity leave may help fathers to balance these competing pressures by allowing fathers time at home to help with domestic tasks while maintaining their positions within the paid labor market (Rehel 2014; Tanaka and Waldfogel 2007). Time off work following a birth may be especially beneficial to low-income families who often are not employed in flexible jobs (Williams 2010; Winston 2014). Specifically, time off work after a birth may reduce the likelihood of role traditionalization by providing fathers time to learn and practice parenting tasks. This devoted time may help fathers to feel comfortable engaging in tasks that have traditionally been done by mothers and begin to view themselves as competent caregivers, which may strengthen men’s identities as fathers and lead them to prioritize engaged fathering (Pasley, Petren, and Fish 2014; Pragg and Knoester 2017; Rehel 2014). Taking time off work may also provide an opportunity for parents to learn to share parenting tasks and establish clear expectations about the division of household labor, potentially reducing the likelihood of perceiving the division of labor as unfair (Rehel 2014). Overall, taking time off work following a child’s birth may signal a commitment by fathers to become [more] equal coparents, which may reduce conflicts about domestic labor (Nomaguchi, Brown, and Leyman 2017).

Hypothesis 1: Mothers will report higher levels of relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality if fathers take time off work after the birth of a child.

Hypothesis 2: Length of time off work will be positively associated with mothers’ reports of relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality.

Mediating Role of Father Involvement

Although taking time off of work after a birth may improve parental relationships, simply demonstrating a commitment to coparenting for a brief period of time may not be sufficient to maintain a high-quality relationship (Neponmyaschy and Waldfogel 2007; Pragg and Knoester 2017). That is, time off of work following a birth may only help to strengthen parental relationships if fathers use this time to demonstrate support and devotion to mothers.

One way that fathers can demonstrate their desire to facilitate an equitable division of labor is through their involvement in childcare. With time off work, fathers may become more likely to commit to childcare and other domestic tasks that have been traditionally performed by mothers (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie 2006; Rehel 2014). Moreover, time off work (especially longer periods of time) may enable fathers to bond with their child from birth, increasing the likelihood that men remain engaged in their child’s life in the future (Cabrera, Fagan, and Farrie 2008; Petts and Knoester 2018). Indeed, paternity leave-taking and length of paternity leave are associated with greater father involvement in both developmental and caretaking tasks (Haas and Hwang 2008; Huerta et al. 2014; Neponmyaschy and Waldfogel 2007; Petts and Knoester 2018; Pragg and Knoester 2017; Tanaka and Waldfogel 2007).

Father involvement may also contribute to higher parental relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality. Indeed, more frequent father involvement is associated with stronger parental relationships—and these associations are especially strong for mothers’ perceptions of relationships (Carlson et al. 2016; Hohmann-Marriott 2009; Kalmijn 1999; McClain 2011; McClain and Brown 2017; Nomaguchi et al. 2017). Although studies have shown that the relationship between father involvement and parental relationships may be mediated (father involvement leads mothers to feel the division of labor is fair, improving relationship quality) or bidirectional (higher quality relationships may motivate fathers to be more involved), greater investment by fathers (i.e., taking time off work and being engaged with children) likely allows for a more equitable division of childcare and ultimately better relationships with mothers (Carlson et al. 2011; Carlson, McLanahan, and Brooks-Gunn 2008; McClain and Brown 2017; Newkirk et al. 2017).

Hypothesis 3: Father involvement will at least partially mediate the relationships between fathers’ time off work (and length of time off) and parental relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality.

Other Factors

Although fathers’ time off work following a birth may be associated with parental relationship outcomes, there are other factors that may confound these associations. Most notably, opportunities for, and barriers to, taking time off work are influenced by socioeconomic status. Higher SES is associated with greater access to paternity leave; most employers do not have [paid] paternity leave programs, and such benefits are even more uncommon in low-income occupations (Winston 2014). Low-income fathers are also less likely to be able to afford taking unpaid time off work. Fathers with higher SES are thus more likely to take time off, and longer periods of time off, than low-SES fathers (Huerta et al. 2014; Petts, Knoester, and Li 2018). Moreover, time off work is often stigmatized as it violates norms of what a good [male] worker should be (Albiston and O’Connor 2016). As such, taking time off work is associated with lower performance ratings and lower future income, and these penalties and stigmas are more commonly applied to disadvantaged fathers (Rudman and Mescher 2013; Williams, Blair-Loy, and Berdahl 2013). Socioeconomic status is also associated with parental relationships. For example, low-SES couples may experience greater conflict due to economic stresses relative to higher SES couples (Hardie and Lucas 2010). Thus, accounting for socioeconomic factors is important to accurately assess the relationship between fathers’ time off work following a birth and parental relationship outcomes.

Parenting attitudes may also shape the relationships between fathers’ time off work following a birth and parental relationships. Having positive attitudes about fathering and believing that fathers should be actively involved in children’s lives may increase the likelihood that men take time (and longer periods of time) off work (Duvander 2014; Petts et al. 2018; Pragg and Knoester 2017), and may also increase the likelihood that fathers are involved in their child’s lives and are part of higher-quality parental relationships (Goldberg 2015; Maume and Sebastian 2012; Pragg and Knoester 2017).

Finally, we incorporate factors such as parents’ age, child’s gender, low birth weight, religious participation, and family size as these may also affect whether fathers take time off of work and parental relationships. Specifically, married, older, first-time, and religious fathers may be more likely to take time off work and also report better relationships than unmarried, younger, nonreligious, and fathers with additional children (Huerta et al. 2014; Pragg and Knoester 2017; Twenge et al. 2003; Umberson et al. 2005; Wolfinger and Wilcox 2008). Having a child with low birth weight may also lead fathers to take more time off work, but may strain parental relationships.

Data and Methods

Data

We use data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCW). The FFCW is a longitudinal birth cohort study that follows 4,898 children born between 1998 and 2000 and their parents. Fragile families are defined as unmarried parents and their children, and these data are drawn from large urban areas with high percentages of low-income, minority, and unmarried parents. Nonetheless, married parents are also included in the data. Birth mothers were interviewed at the hospital or shortly thereafter, and they identified the father of their child who was also interviewed as soon as possible afterward.1 For this study, data are taken from when parents were interviewed shortly after birth (W1) and when children were approximately one (W2), three (W3), and five years old (W4).

The sample is restricted to families in which both parents were interviewed at W1 and W2, families in which fathers were asked about time off work following birth, and families in which fathers were employed at W1 to be eligible to take time off work, resulting in a sample size of 2,109 families for analyses that predict parental relationships at W2. For longitudinal analyses, the sample is further restricted to families in which both parents completed the questionnaires in W1–W4 (N = 1,494) to have valid responses on key measures for both fathers and mothers.2

Fathers’ Time Off Work Following Birth

In the W2 survey, fathers were asked “did you take any time off from work for the birth of the focal child?” Fathers who responded yes were then asked “in total, how many weeks of leave, paid or unpaid, did you take for the birth of the focal child?” These questions were used to construct two indicators. Time off work indicates whether fathers took time off work for the birth of their child (1 = yes). Length of time off work is an ordinal-level variable indicating whether fathers took no time off, one week, 2 weeks, or more than 2 weeks off.

Although there is reason to believe that these questions indicate whether (and for how long) fathers took paternity leave as fathers were asked specifically about leave,3 we are unable to determine whether fathers took time off using FMLA, an employer family leave program, vacation/sick time, or some other means. Thus, we focus on time off of work following childbirth in this study, but acknowledge that understanding the associations between fathers’ time off work following a birth and parental relationship outcomes may inform policy and workplace decisions about paternity leave.

Parental Relationships

We focus on three dimensions of parental relationships. Measures are taken from mothers’ responses in W2–W4. First, relationship quality indicates mothers’ ratings of their relationship with the child’s father (1 = poor to 5 = excellent).

Second, relationship support is taken from mothers’ responses to questions about how often fathers (1 = never to 3 = often): (a) are fair and willing to compromise when you have a disagreement, (b) express affection or love, (c) insult or criticize you or your ideas (reverse coded), (d) encourage or help you do things that are important, (e) listen to you when you need someone to talk to, and (f) really understand your hurts and joys (α = .76).4 The mean response is used. Mothers were only asked these questions if they were romantically involved with the father, so analyses involving relationship support have smaller sample sizes (N = 1,687 for W2 analyses; N = 1,297 for W2–W4 analyses).

Finally, coparenting quality is taken from mothers’ responses to questions about how often (1 = rarely true to 3 = always true): (a) father acts like the father you want for your child, (b) you can trust father to take good care of child, (c) father respects the schedules and rules you make for child, (d) father supports you in the way you want to raise child, (e) you and father talk about problems that come up with raising child, and (f) you can count on father for help when you need someone to look after child for a few hours (α = .81). The mean response is used.

Father Involvement

Father involvement is taken from W2–W4 and indicates how many days per week fathers reported engaging in activities such as playing games, reading, and singing songs to their child. Mean responses are used (α = .81). There was some variation between waves in the activities that fathers were asked about, but all items capture active engagement with children. Because items varied between waves, standardized measures of father involvement (i.e., M = 0; SD = 1) are included in the longitudinal analyses following procedures used in previous research (Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale, and McRae 1998; McClain and DeMaris 2013).

Control Variables

A number of W1 variables were included as controls. Controls for SES include fathers’ (0 = less than $10,000 to 8 = $75,000 or more) and mothers’ income (0 = less than $5,000 to 4 = $20,000 or more), and both parents’ educational attainment (1 = did not complete high school to 4 = college degree). Parents’ work hours is categorized as (a) part-time (less than 35 hours a week), (b) full-time (35–54 hours a week, used as reference category), and (c) more than full time (55 hours a week or more). An additional category of does not work is included for mothers, and is also included for fathers in the longitudinal analyses (all fathers had to be working at W1 to be eligible to take time off, but may not be working at later waves). Fathers’ occupation type is categorized as (a) professional, (b) labor (used as reference category) (c) service, (d) sales, or (e) other. Race/ethnicity for both parents is coded as (a) White (used as reference category), (b) Black, (c) Latino, or (d) other race/ethnicity. We also control for parents’ age, number of other children, whether the father had a child with a different mother, and number of other adults in the child’s household. Relationship status at W1 is categorized as (a) married (used as reference category), (b) cohabiting, and (c) nonresident father. Results were largely unchanged in analyses separating the nonresident category into romantically involved (i.e., visiting) and non-romantically involved, so these are combined into one nonresident category.

Other variables include child gender (1 = male), whether child had low birth weight, and parents’ religious participation (0 = never to 4 = once a week or more). We also include W1 indicators of relationship support and relationship conflict (taken from mothers’ reports on how often she and father argued about money, spending time, sex, the pregnancy, alcohol/drug use, and being faithful; α = .60) to better establish temporal ordering.

We also include W1 variables that assess attitudes regarding parenting roles. Positive father attitudes are indicated by fathers’ level of agreement at (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) on whether (a) being a father and raising children is one of the most fulfilling experiences for a man, (b) I want people to know that I have a new child, and (c) not being a part of my child’s life would be one of the worst things that could happen to me (α = .73). The mean response is used. Both parents were also asked to identify which fathering role (provide regular financial support, teach child about life, provide direct care, show love and affection to the child, provide protection for the child, or serve as an authority figure and discipline the child) was most important. Engaged father attitudes indicates parents who identified either providing direct care or showing love and affection to the child as most important, and separate indicators for mothers and fathers are used. Traditional gender attitudes is a dichotomous variable indicating whether parents agree that it is much better for everyone if the man earns the main living and the woman takes care of the home and family, and we include separate indicators for mothers and fathers. Finally, prenatal involvement is a dichotomous measure indicating that fathers both (a) gave the mother money to buy things for the baby during pregnancy and (b) helped in other ways such as providing transportation to the prenatal clinic or helping with chores prior to the child’s birth.

We also incorporate time-varying variables into the longitudinal analyses. These variables are coded as previously described, but are taken from W2–W4 and allowed to vary over these waves. Time-varying variables include parents’ income, hours worked, and age. Fathers’ occupation type, relationship status,5 number of children, number of other adults in the child’s household, and religious participation are also included as time-varying variables.

Analytic Strategy

Ordinary least squares (OLS), generalized ordered logistic regression, and multilevel (i.e., growth curve) models are used in this study. First, we analyze whether fathers’ time off work following a birth (and length of time off) are associated with parental relationship outcomes at W2; OLS models are used to estimate relationship support and coparenting quality, and generalized ordered logistic regression models are used to estimate relationship quality.6 We first estimate a model including time off work or length of time off and the W2 control variables, and then add the W2 indicator of father involvement in the second model. Sobel-Goodman tests (using bootstrapped standard errors and 1,000 replications) were used to formally test for mediation. For the generalized ordered logistic regression models, the KHB method is used to test for indirect effects, as this method can be used in nonlinear models (Karlson, Holm, and Breen 2012). Results using the KHB method are reported in the text.

Second, multilevel models are used to assess whether fathers’ time off work following a birth and length of time off are associated with longitudinal patterns of parental relationships from W2–W4. These models account for the lack of independence and clustering in longitudinal data due to repeated measurements over time (level 1) nested within individuals (level 2) (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). Unconditional growth models (i.e., models without any predictor variables) were first examined to determine the shape of the trajectories. For each dimension of parental relationships, a linear model was the best fitting model. Years after birth was used as the indicator of time and rescaled so that 0 is used to estimate the intercept (0 for W2, 2 for W3, and 4 for W4). A random effect term for years after birth was also included in all models (tests for additional random effects and slopes did not improve model fit). All continuous variables were mean centered.

Similar to the W2 analyses, two models are estimated for each outcome. In these models, time-invariant control variables are taken from W1 (i.e., race/ethnicity, parent education, child gender, low birth weight, attitudes). Time-varying variables are taken from each wave (i.e., father involvement, income, hours worked, fathers’ occupation, family structure, number of children, number of other adults, and religious participation). Less than 5% of cases include missing data (with the exception of fathers’ income – 9% of cases have missing data). To account for this, multiple imputation from five imputed models is used.

Selection

Although fathers’ time off work following a birth may influence parental relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality, it is also possible that there are factors that lead fathers to take time off work (and longer periods of time off) as well as promote better relationships with mothers (i.e., selection effects). Although we are unable to examine whether any associations between time off work and dimensions of parental relationships are due to unobserved factors (availability of paternity leave programs, family-friendly workplace culture, father’s personality, etc.), we take two approaches to minimize concerns about selection effects given the observed data available.

To assess whether associations between fathers’ time off work and parental relationships are due to selection, we utilize propensity score matching (PSM). PSM models approximate an experimental design in which groups are matched on a variety of covariates and only differ in whether or not they received the treatment (i.e., took time off) to isolate the effect of treatment (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983). To estimate propensity scores, we first ran a logistic regression model using W1 control variables to match fathers in the treatment (took time off) and control (did not take time off) groups and generate propensity scores (i.e., the probability of taking time off). Respondents with the closest propensity scores were matched. We then assessed whether the assumption for common support was met (i.e., that propensity scores overlap between the treatment and control groups), and omitted cases in which the common support assumption was not met (N = 13). Pre- and post-tests suggest that balance was achieved (i.e., covariates did not differ statistically between the treatment and control groups). Finally, the propensity scores were used to estimate average treatment effects on the treated for each dimension of parental relationships. Full results from these models can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S1).

To assess whether associations between length of time off work and parental relationships are due to selection, we utilize augmented inverse propensity weighted (AIPW) estimators. Similar to PSM, this approach estimates average treatment effects accounting for covariates that may select people into certain treatments (i.e., lengths of time off), yet differs in that AIPW estimators can be used when there are multiple treatments (Cattaneo 2010). To utilize AIPW estimators, we followed a similar process as described for PSM. The same W1 variables were used in models that simultaneously predict length of time off and dimensions of parental relationships to estimate the average treatment effects of length of time off. Diagnostic analyses suggest that the main assumptions needed to utilize AIPW estimators were met. Full results can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S1).

Results

Summary statistics for all variables at W1 are included in Table 1 (unweighted results are shown). Results show that mothers’ reports of relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality appear to be high. Mothers report their relationship quality with fathers to be between good and very good on average, and means for both relationship support and coparenting quality are close to the index maximum (2.74 out of 3). Fathers are also frequently engaged in activities with their new child (more than 4 days per week, on average).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics

| M | SD | Min | Max |

M (no time off) |

M (time off) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship Quality (W2) | 3.66 | 1.25 | 1 | 5 | 3.28 | 3.76*** | |

| Coparenting Quality (W2) | 2.74 | 0.40 | 1 | 3 | 2.64 | 2.76*** | |

| Relationship Supportiveness (W2) | 2.74 | 0.35 | 1 | 3 | 2.58 | 2.68*** | |

| Time Off Work | 0.79 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.00*** | |

| Length of Time Off Work | 1.07 | 0.78 | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 1.35*** | |

| Father Involvement | 4.35 | 1.59 | 0 | 7 | 3.82 | 4.49*** | |

| Mother Age | 25.77 | 6.10 | 16 | 56 | 24.41 | 26.12*** | |

| Father Age | 28.18 | 6.93 | 16 | 57 | 27.40 | 28.39** | |

| Mother is Whitea | 0.29 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.33*** | |

| Mother is Black | 0.40 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.58 | 0.36*** | |

| Mother is Latino | 0.26 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.23 | 0.27 | |

| Mother is Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.04 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Mother is U.S. Native | 0.85 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.84** | |

| Father is Whitea | 0.27 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.31*** | |

| Father is Black | 0.42 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.59 | 0.37*** | |

| Father is Latino | 0.26 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.27 | |

| Father is Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.05 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| Father is U.S. Native | 0.84 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.82** | |

| Mother Education | 2.34 | 1.03 | 1 | 4 | 2.12 | 2.40*** | |

| Father Education | 2.31 | 1.00 | 1 | 4 | 2.05 | 2.38*** | |

| Father Income | 3.36 | 2.18 | 0 | 8 | 2.71 | 3.54*** | |

| Mother Income | 1.43 | 2.66 | 0 | 4 | 1.18 | 1.50*** | |

| Mother Does Not Work | 0.05 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| Mother Works Part-Time | 0.30 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.30 | |

| Mother Works Full-Timea | 0.62 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.63 | |

| Mother Works Overtime | 0.03 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| Father Works Part-Time | 0.11 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.10*** | |

| Father Works Full-Timea | 0.71 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.73** | |

| Father Works Overtime | 0.18 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

| Professional Occupation | 0.17 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.18*** | |

| Labor Occupationa | 0.49 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.53 | 0.48 | |

| Sales Occupation | 0.08 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.09 | |

| Service Occupation | 0.24 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.23 | |

| Other Occupation | 0.02 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Marrieda | 0.34 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.39*** | |

| Cohabiting | 0.41 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.41 | |

| Nonresident Father | 0.25 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.21*** | |

| Other Children | 1.04 | 1.15 | 0 | 5 | 1.15 | 1.02*** | |

| Had Child with Other Mother | 0.29 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.27*** | |

| Other Adults in Household | 0.59 | 0.93 | 0 | 3 | 0.72 | 0.56** | |

| Religious Participation (Mother) | 2.11 | 1.36 | 0 | 4 | 2.08 | 2.11 | |

| Religious Participation (Father) | 1.91 | 1.35 | 0 | 4 | 1.83 | 1.93 | |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 3.76 | 0.40 | 1 | 4 | 3.72 | 3.77** | |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Father) | 0.66 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.66 | |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Mother) | 0.74 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.75 | |

| Traditional Gender Attitudes (Father) | 0.39 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.38 | 0.39 | |

| Traditional Gender Attitudes (Mother) | 0.29 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.30 | |

| Prenatal Involvement | 0.93 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.96*** | |

| Child is Male | 0.52 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.51 | 0.52 | |

| Low Birth Weight | 0.09 | - | 0 | 1 | 0.11 | 0.09 | |

| W1 Relationship Support | 2.77 | 0.26 | 1 | 3 | 2.72 | 2.79*** | |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | 1.40 | 0.35 | 1 | 3 | 1.45 | 1.39** |

N = 2109 (N = 1687 for relationship support).

Used as reference category. Significant differences determined by two-tailed t-tests (*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001).

In addition, taking time off of work following a birth is quite common (79% of fathers took time off), but short in duration (one week, on average).7 Specifically, of the fathers who took time off, 74% took one week, 17% took 2 weeks, and 9% took more than two weeks off. Although these periods of time off work are short compared to other high-income countries and the amount allowed by FMLA, these results are consistent with findings on leave within the U.S. Fathers take relatively short leaves in the U.S. because the U.S. does not have a statutory paid leave policy, many people are ineligible for FMLA, and most workplaces do not provide paid family leave (Albiston and O’Connor 2016; Petts et al. 2018; Winston 2014). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that fathers who take leave under the California Paid Leave Program only take 1.5 weeks of leave on average (Bartel et al. 2018).

Results in Table 1 also provide initial evidence that relationship quality, coparenting quality, relationship support, and father involvement are higher (on average) when fathers take time off work compared to fathers who do not take time off work. We turn to multivariate analyses to more fully test our hypotheses.

Fathers’ Time Off Work and Parental Relationship Outcomes at W2

First, we examine whether fathers’ time off work following a birth is associated with parental relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality at W2. Results examining whether fathers’ time off work is associated with relationship quality are presented in Table 2. Consistent with the first hypothesis, mothers report better relationships with fathers if fathers take time off work following a birth (b = .22, p < .05), as shown in Model 1. However, the effect size is modest (taking time off work is associated with a 1/10 SD increase in relationship quality). This relationship persists in PSM models, suggesting that the relationship is not a function of selection effects. Similarly, as shown in Model 3, length of time off work is positively associated with relationship quality (b = 0.11, p < .05), and results from AIPW models suggest that relationship quality is higher if fathers take one or two weeks off, but longer periods of time off work are unrelated to relationship quality. Thus, there is evidence supporting the first two hypotheses.

Table 2.

Results from Generalized Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Relationship Quality One Year After a Birth (W2)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE |

| Time Off Work | 0.22* | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.11 | ||||

| Length of Time Off Work | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.22*** | 0.03 | 0.22*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| Mother Age | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Father Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Black (Mother) | −0.14 | 0.18 | −0.14 | 0.19 | - | - | −0.14 | 0.19 |

| Latino (Mother) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Mother) | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| U.S. Native (Mother) | −0.03 | 0.17 | −0.10 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.17 | - | - |

| Black (Father) | - | - | - | - | −0.28 | 0.19 | - | - |

| Latino (Father) | −0.09 | 0.18 | −0.12 | 0.18 | −0.11 | 0.18 | −0.11 | 0.18 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Father) | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.26 | −0.00 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.26 |

| U.S. Native (Father) | 0.09 | 0.16 | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.16 |

| Mother Education | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.11* | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Father Education | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| Father Income | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Mother Income | 0.00 | 0.03 | - | - | −0.00 | 0.03 | - | - |

| Does Not Work (Mother) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Works Part-Time (Mother) | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.09 |

| Works Overtime (Mother) | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.26 | - | - | - | - |

| Works Part-Time (Father) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Works Overtime (Father) | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| Professional Occupation | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Sales Occupation | −0.01 | 0.19 | −0.05 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.16 | −0.06 | 0.16 |

| Service Occupation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other Occupation | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.33 |

| Cohabiting | - | - | −0.35** | 0.12 | - | - | −0.36** | 0.12 |

| Nonresident Father | - | - | −0.76*** | 0.15 | - | - | −0.76*** | 0.15 |

| Other Children | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Had Child with Other Mother | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other Adults in Household | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| Religious Participation (Mother) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Religious Participation (Father) | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 0.20 | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Father) | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.09 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Mother) | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Traditional Gender (Father) | - | - | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Traditional Gender (Mother) | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | - | - | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| Prenatal Involvement | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Child is Male | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Low Birth Weight | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| W1 Relationship Support | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | −0.83*** | 0.13 | −0.82*** | 0.13 | −0.82*** | 0.13 | −0.82*** | 0.13 |

N = 2109; Variables not reported are those that violated the proportional odds assumption. These variables are included in the model, but results vary by level of relationship quality. Full results with these variables (including separate coefficients for each level of relationship quality) are included in the supplementary materials (Table S2).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Potential mediating effects are examined in Models 2 and 4 of Table 2. Results support the third hypothesis in showing that father involvement appears to mediate the relationships between fathers’ time off work and relationship quality. Formal tests indicate that approximately 46% of the reduction of the coefficient for taking time off work (p < .001) and 57% of the reduction of the coefficient for length of time off work (p < .001) is reduced due to inclusion of father involvement in the models.

Results examining whether fathers’ time off work following a birth is associated with mother’s reports of relationship support are presented in Table 3. As shown in Model 1, mothers report receiving more support if fathers take time off work (b = .05, p < .01). However, this relationship is not significant in PSM models, suggesting that the relationship between fathers’ time off work and relationship support is due to selection effects. In addition, as shown in Model 3, length of time off is unrelated to relationship support. This result persists in AIPW models. Thus, evidence suggests that fathers’ time off work is unrelated to relationship support at W2.

Table 3.

Results from OLS Regression Models Predicting Relationship Support One Year after a Birth (W2)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B |

| Time Off Work | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | ||||

| Length of Time Off Work | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01* | 0.00 | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| Mother Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Father Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Black (Mother) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Latino (Mother) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Mother) | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| U.S. Native (Mother) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Black (Father) | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Latino (Father) | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Father) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| U.S. Native (Father) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Mother Education | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Father Education | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Father Income | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Mother Income | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Does Not Work (Mother) | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| Works Part-Time (Mother) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Works Overtime (Mother) | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.05 | 0.11* | 0.05 |

| Works Part-Time (Father) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Works Overtime (Father) | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Professional Occupation | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Sales Occupation | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 |

| Service Occupation | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 |

| Other Occupation | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.06 |

| Cohabiting | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Nonresident Father | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Had Child with Other Mother | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Other Children | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Other Adults in Household | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Religious Participation (Mother) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Religious Participation (Father) | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Father) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Mother) | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Traditional Gender (Father) | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Traditional Gender (Mother) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Prenatal Involvement | −0.00 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.04 |

| Child is Male | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Low Birth Weight | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| W1 Relationship Support | 0.59*** | 0.03 | 0.59*** | 0.03 | 0.59*** | 0.03 | 0.59*** | 0.03 |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.14*** | 0.03 |

| Sobel-Goodman Test | 0.00* | 0.00 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.26 | ||||

N = 1687

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Results examining whether fathers’ time off work is associated with coparenting quality at W2 are presented in Table 4. As shown in Model 1, mothers report better coparenting relationships if fathers take time off of work (b = .07, p < .01), and this relationship persists in PSM models. Yet, the effect size is modest; taking time off is associated with a 1/5 SD increase in coparenting quality. In addition, as shown in Model 3, length of time off is associated with higher-quality coparenting relationships (b = .02, p < .05). However, this only appears to hold when fathers take one week off (b = .04, p < .05) once selection is accounted for. Similar to results in Table 2, approximately 34% of the effect of taking time off work on coparenting quality, and 65% of the effect of length of time off, is indirect through increasing father involvement. Yet, taking time off work remains a significant predictor of coparenting quality even after accounting for father involvement (b = .05, p < .05), as shown in Model 2. Overall, results from Table 4 provide support for the first and third hypotheses. Consistent with the second hypothesis, there is also evidence that length of time off work is positively associated with coparenting quality.

Table 4.

Results from OLS Regression Models Predicting Coparenting Quality One Year after a Birth (W2)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B |

| Time Off Work | 0.07** | 0.02 | 0.05* | 0.02 | ||||

| Length of Time Off Work | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.06*** | 0.01 | ||||

| Controls | ||||||||

| Mother Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 |

| Father Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Black (Mother) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Latino (Mother) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Mother) | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| U.S. Native (Mother) | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Black (Father) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Latino (Father) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Other Race/Ethnicity (Father) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| U.S. Native (Father) | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Mother Education | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Father Education | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Father Income | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Mother Income | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Does Not Work (Mother) | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Works Part-Time (Mother) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Works Overtime (Mother) | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| Works Part-Time (Father) | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 0.03 |

| Works Overtime (Father) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Professional Occupation | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Sales Occupation | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Service Occupation | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Other Occupation | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Cohabiting | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.05* | 0.02 | −0.06* | 0.02 | −0.05* | 0.02 |

| Nonresident Father | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.10** | 0.03 | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.10** | 0.03 |

| Other Children | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 |

| Had Child with Other Mother | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 | −0.06** | 0.02 |

| Other Adults in Household | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 |

| Religious Participation (Mother) | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Religious Participation (Father) | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Positive Father Attitudes | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Father) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Engaged Father Attitudes (Mother) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Traditional Gender (Father) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Traditional Gender (Mother) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Prenatal Involvement | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.10** | 0.03 | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.10** | 0.03 |

| Child is Male | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Low Birth Weight | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| W1 Relationship Support | 0.39*** | 0.04 | 0.37*** | 0.04 | 0.39*** | 0.04 | 0.37*** | 0.04 |

| W1 Relationship Conflict | −0.17*** | 0.03 | −0.16*** | 0.03 | −0.17*** | 0.03 | −0.16*** | 0.03 |

| Sobel-Goodman Test | 0.02*** | 0.01*** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.25 | ||||

N = 2109

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Fathers’ Time Off Work and Trajectories of Parental Relationship Outcomes

Next, we analyze whether fathers’ time off work following a birth is associated with trajectories of parental relationship quality, relationship support, and coparenting quality over the first five years after the birth of a child. Results are reported in Table 5. In these models, initial status indicates the average level of each indicator of parental relationships at W2, and the variables listed under initial status indicate relationships with this initial level. Linear rate of change indicates the degree to which the trajectory changes over time, and the variables listed under rate of change indicate relationships with the linear changes.

Table 5.

Results from Multilevel Models Predicting Trajectories of Parental Relationships from 1–5 Years after a Birth (W2–W4)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B | B | SE B |

| Panel A: Relationship Quality | ||||||||

| Initial Status | 3.82*** | 0.19 | 3.88*** | 0.19 | 3.84*** | 0.19 | 3.90*** | 0.19 |

| Time Off Work | 0.15* | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.07 | ||||

| Length of Time Off | 0.09** | 0.03 | 0.07* | 0.03 | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.15*** | 0.03 | ||||

| Linear Rate of Change | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Time Off Work | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Length of Time Off | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Father Involvement | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Sobel-Goodman Test | 0.02** | 0.01** | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −5030 | −4961 | −5030 | −4961 | ||||

| Panel B: Relationship Support | ||||||||

| Initial Status | 2.64*** | 0.08 | 2.64*** | 0.08 | 2.66*** | 0.07 | 2.66*** | 0.07 |

| Time Off Work | 0.06** | 0.02 | 0.06* | 0.02 | ||||

| Length of Paternity Leave | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01* | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Linear Rate of Change | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Time Off Work | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Length of Time Off | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Father Involvement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Sobel-Goodman Test | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −676 | −653 | −676 | −653 | ||||

| Panel C: Coparenting Quality | ||||||||

| Initial Status | 2.64*** | 0.07 | 2.65*** | 0.07 | 2.66*** | 0.07 | 2.68*** | 0.06 |

| Time Off Work | 0.07** | 0.02 | 0.06** | 0.02 | ||||

| Length of Time Off | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Father Involvement | 0.06*** | 0.01 | 0.06*** | 0.01 | ||||

| Linear Rate of Change | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Time Off Work | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||||

| Length of Time Off | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Father Involvement | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Sobel-Goodman Test | 0.00* | 0.00** | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −656 | −602 | −659 | −605 | ||||

For Panels A and C, N = 1494 (4482 person-years). For Panel B, N = 1297 (3339 person-years). Models include all control variables described in the methods section.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

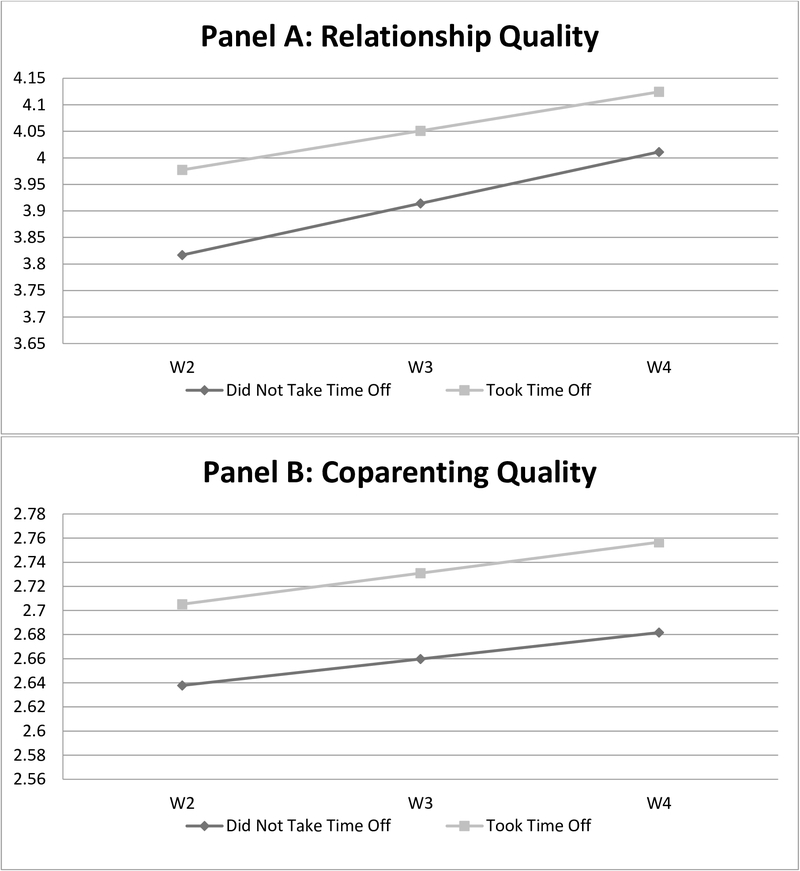

As shown in Model 1 of each panel in Table 5, taking time off work following a birth is associated with higher relationship quality (b = .15, p < .05), relationship support (b = .06, p < .01), and coparenting quality (b = .07, p < .01). These positive relationships persist in PSM models that account for selection into relationship and coparenting quality, but the relationship between time off work and trajectories of relationship support appears to be due to selection. In each panel in Table 5, the linear slope coefficient for time off work is not statistically significant, suggesting that the higher levels of relationship and coparenting quality for fathers who take time off persist over time. These results are further illustrated in Figure 1, and show modest effect sizes (taking time off is associated with 1/6 SD greater relationship quality and 1/8 SD higher coparenting quality).

Figure 1.

Predicted Trajectories of Parental Relationship Outcomes by Time Off Work

Father involvement is included in Model 2 of Table 5. Consistent with the W2 results, father involvement is positively associated with trajectories of relationship and coparenting quality; 24% of the effect of taking time off work on relationship quality, and 25% of the effect of taking time off work on coparenting quality, is estimated to be indirect through increasing father involvement. Taking time off of work remains a significant predictor of trajectories of coparenting quality (b = .06, p < .01) after accounting for father involvement.

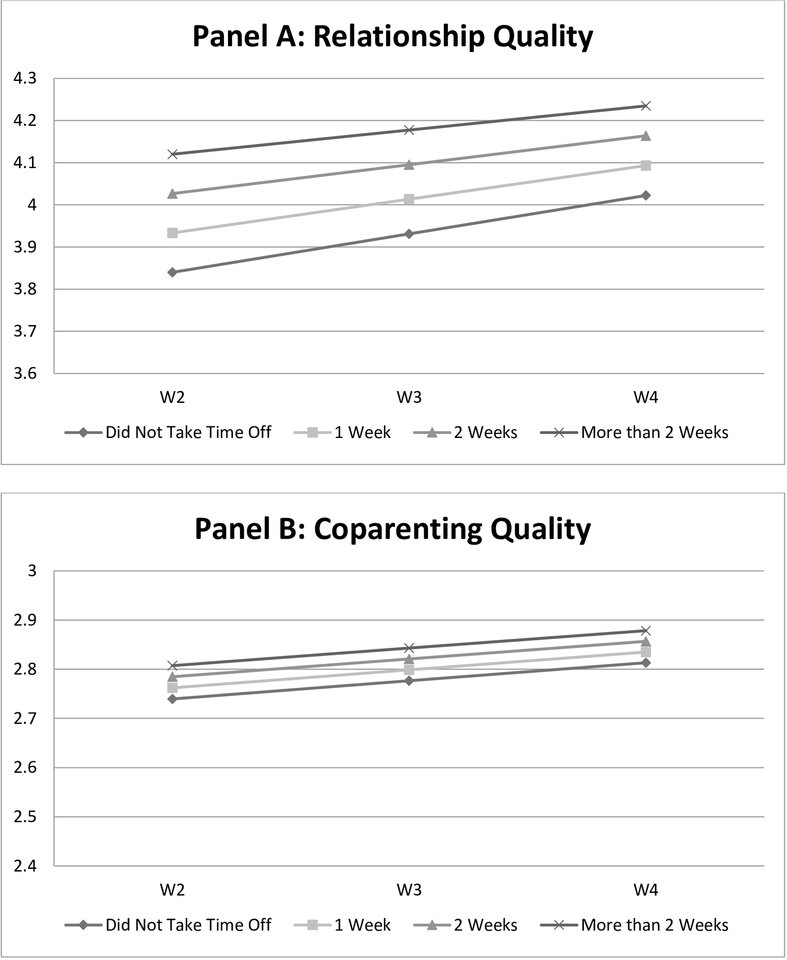

As shown in Model 3 of Table 5, length of time off work following a birth is positively associated with trajectories of relationship quality (b = .09, p < .01), relationship support (b = .02, p < .05), and coparenting quality (b = .03, p < .05). These results persist in AIPW models for relationship quality and coparenting quality, but the relationship between length of time off work and trajectories of relationship support appears to be due to selection. Significant relationships are further illustrated in Figure 2, which shows that longer periods of time off are associated with higher quality relationships but effect sizes are modest; taking more than two weeks off is associated with 1/5 SD higher relationship quality and 1/4 SD higher coparenting quality relative to fathers who do not take time off work.

Figure 2.

Predicted Trajectories of Parental Relationship Outcomes by Length of Paternity Leave

Father involvement is included in Model 4 of Table 5 to further test the third hypothesis. Consistent with other results, formal tests of mediation indicate that 25% of the effect of length of time off work on relationship quality and coparenting quality is indirect through increasing father involvement. However, length of time off remains a significant predictor of trajectories of relationship quality even after accounting for father involvement (b = .07, p < .05).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to expand knowledge on the consequences of paternity leave by focusing on whether taking time off work and length of time off work were associated with mothers’ reports of different dimensions of parental relationships in both the short- and long-term, and whether these associations were mediated by father involvement. In doing so, results suggest that policies allowing fathers to take time off work following a birth may enable parents to enact egalitarian ideals by providing fathers with time to learn and engage in parenting behaviors – and consequently improve their relationships after the arrival of a child. These findings are particularly important given the focus on disproportionately disadvantaged families in this study; millions of dollars have been spent on programs to promote responsible fatherhood in disadvantaged communities, but evaluation of these programs suggest that establishing strong coparenting relationships remains a barrier to active father involvement (Martinson and Nightingale 2008). Results from this study suggest that enabling disadvantaged fathers to take time off work may help fathers become more engaged parents and coparents.

First, we found evidence in support of the first hypothesis, which anticipated that taking time off work following a birth would be positively associated with parental relationship outcomes. Mothers reported higher relationship and coparenting quality one year after the birth of their child and over the first few years of their child’s life if fathers took time off work.

By taking time off work following a birth, fathers may demonstrate their willingness to be engaged in family life and do their share of the childcare. Fathers who take time off work may also signal their intentions to not solely act as a financial provider, and their commitments to accept the consequences of taking time off work and expanding their roles in their families (Albiston and O’Connor 2016; Pragg and Knoester 2017; Rehel 2014). Thus, taking time off work following a birth may increase the likelihood that mothers feel that the division of household labor is fair and reduce the role conflicts and overloads mothers experience, resulting in higher relationship and coparenting quality (Dew and Wilcox 2011; Milkie et al. 2002).

We also found support for the hypothesis about longer periods of time off work following a birth being positively associated with parental relationship outcomes. Although periods of time off work were short (especially compared to many European countries), taking 1–2 weeks off was associated with more favorable reports of relationship and coparenting quality one year after a child’s birth and longitudinally.

In sum, it seems that in addition to symbolizing a commitment to be an engaged parent, taking 1–2 weeks off work may provide fathers with time that can be used to learn how to be a more equitable caregiver. The opportunity to be home with children after birth may encourage fathers to learn parenting skills and gain confidence as a parent (Rehel 2014). Longer periods of time off may enable parents to learn how to parent together and establish clearer understandings of each parent’s capabilities to fulfill different roles. These experiences may be especially beneficial to fathers, as fathers may have less experience with caretaking (Bianchi et al. 2006). As such, consistent with previous research suggesting that an egalitarian division of labor is associated with higher quality relationships, taking a week or two off work may help reduce role conflicts, facilitate egalitarianism, and nurture stronger parental relationships8 (Carlson et al. 2016; Stanik and Bryant 2012; Wilcox and Dew 2016).

In contrast to our hypothesis, taking time off work appeared to be unrelated to relationship support after accounting for selection effects. Because information on relationship support was only available for parents who were romantically involved, it is likely that these analyses were selective on stronger relationships. Indeed, fathers who were romantically involved with mothers at W2 were significantly more likely to have taken time off work than fathers who were not romantically involved (82% vs. 66%). Romantically involved fathers also appear to be more advantaged (higher income, education, etc.). Within a sample of disadvantaged parents, this relative advantage may be particularly significant because the ability to take time off work is highly dependent on SES, and relationship quality also varies by SES (Hardie and Lucas 2010; Winston 2014). Future research should further consider whether fathers’ time off work is associated with relationship support.

Finally, results suggest that father involvement at least partially mediates the associations between fathers’ time off work following a birth and both relationship quality and coparenting quality. That is, both time off work and length of time off are associated with more frequent father involvement, and mothers are more likely to rate their relationships with fathers more positively if fathers are more engaged in their child’s life. Consistent with previous research, time off of work appears to facilitate greater father involvement (Pragg and Knoester 2017; Rehel 2014). Mothers are also more likely to feel supported in their relationship and report higher relationship quality with fathers if the fathers are more involved, as mothers likely feel less pressure to serve as the sole caregiver, reducing role conflict (Carlson et al. 2016; Kalmijn 1999; Keizer and Shenk 2012; McClain and Brown 2017).

Overall, results from this study suggest that taking time off work following the birth of a child may enable fathers to become more engaged parents, contributing to reduced role conflicts, a more equitable division of household labor, and stronger relationships with mothers. Most fathers are unable to take longer periods of time off (especially paid time off) because few employers provide [paid] leave and the U.S. does not have a statutory paid leave policy (Albiston and O’Connor 2016; Petts et al. 2018; Winston 2014). Expansions of [paid] parental leave policies may provide the structural support that parents need to enact their desires to share equally in both domestic and paid labor, ultimately benefiting parents, families, and children (Gerson 2010; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015). Increased access to leave policies may be especially beneficial for economically disadvantaged families, who often face economic and social constraints that make it difficult to fulfill the dual responsibilities of breadwinning and caregiving (Hohmann-Marriott 2009; Williams 2010). Moreover, adopting and encouraging the use of leave policies may improve parental relationships particularly among disadvantaged families who have a high likelihood of experiencing union transitions (Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing 2007). Although there is reason to believe that economically advantaged families may receive similar benefits from paternity leave, future research should more fully consider the relative benefits of leave.

There are some limitations to note. First, there is no information about whether fathers are using workplace parental or paternity leave programs or other ways of taking time off of work (unpaid leave through the Family and Medical Leave Act, vacation or sick days, etc.). More specific information about length of time off (i.e., days instead of weeks) would also be helpful given the relatively short periods of time off work that fathers take in the U.S.

Second, this study utilized a number of strategies to minimize the possibility that any observed relationship between fathers’ time off work and parental relationships may be due to selection effects based on observed characteristics. However, we are unable to account for possible selection effects due to unobserved factors (availability of workplace leave programs, father’s personality, etc.). Employing an approach to further minimize this selectivity concern would be ideal, however such approaches are either not feasible (e.g., an experimental design in which fathers are randomly assigned to take leave or not) or are hampered by a lack of data on parental relationship outcomes (e.g., national-level data such as the Current Population Surveys collected before and after implementation of state family leave policies). Thus, we utilize the best available data to analyze the relationship between fathers’ time off of work and parental relationship outcomes, but additional work is needed to provide further evidence of the observed relationships reported in this study.

Third, although this study focused on three dimensions of parental relationships, the range of these items is somewhat limited. Furthermore, this study did not consider the relative success or failure of parental relationships, as a focus on union stability was outside of the scope of this study (see Footnote 8). Future research should incorporate more precise measures in assessing whether fathers’ time off work helps to strengthen and stabilize parental relationships.

Fourth, there is theoretical and empirical evidence to support the findings that fathers’ time off of work following a birth may increase father involvement, which in turn improves parental relationships. However, reciprocal relationships are also possible (e.g., parental relationship quality increases father involvement). Indeed, supplementary models suggest that stronger parental relationships are associated with greater father involvement, but there is less evidence that parental relationship outcomes mediate the relationships between fathers’ time off work and father involvement. Certainly, this is an avenue for future research to consider.

Finally, although this study suggests that fathers’ time off work following a birth may increase father involvement (and strengthen relationships), we do not have data on how childcare is divided within these families and whether this division of labor is seen as equitable. Although fathers’ participation in childcare is associated with parental relationships in some studies (Carlson et al. 2016; Kalmijn 1999; Keizer and Shenk 2012; McClain and Brown 2017), understanding whether fathers’ time off work following a birth increases the likelihood of an equitable division of household labor is important to consider. We propose father involvement as one possible mechanism that may help explain the relationship between fathers’ time off work following a birth and the nature of parental relationships, but future research should explore other mechanisms such as an equitable division of labor.

This study extends the literature on parental leave by focusing on an additional potential benefit of time off of work: improving parental relationships. Results suggest that fathers’ time off work following a birth and length of time off are associated with higher relationship quality and coparenting quality. Results also suggest that father involvement largely mediates these associations; fathers who take time off work (and longer periods of time off) are more involved with their child and this, in turn, helps to improve parental relationships. These findings may be especially useful to policymakers who aim to strengthen parental relationships.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

Research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03HD087875. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Richard J. Petts is Associate Professor of Sociology at Ball State University. His research examines family inequality broadly defined, with recent work focusing on parental leave as a key social policy and practice that may help to reduce gender inequality and promote family well-being. His recent work has been published in Journal of Marriage and Family, Sex Roles, and Community, Work & Family.

Chris Knoester is Associate Professor of Sociology at Ohio State University. His research focuses on the effects of children on parents’ lives and on the patterns and implications of fathering, specifically. Recently, he has been comprehensively analyzing the patterns and implications of paternity leaves, with Richard J. Petts and Brianne Pragg. This work has also been published in Journal of Marriage and Family, Sex Roles, Journal of Family Issues, and Community, Work, & Family.

Footnotes

By W2, 91% of fathers had established paternity. We included paternity establishment as an additional control in supplementary models, and results are identical to those presented.

Restricting analyses to couples in which both parents are interviewed at each wave may result in a sample of couples with comparatively stronger relationships. Supplementary analyses using a less restrictive sample (mothers interviewed in all waves and fathers interviewed at W2) produced results that are very similar to those presented. We present results using the sample with more complete data to provide a conservative estimate of the relationships between paternity leave, father involvement, and parental relationship outcomes.

Fathers who did not take time off work were asked why, and reasons are consistent with the literature on paternity leave including “did not have access to leave”, “had access to leave but couldn’t afford to take it”, “had access to leave but thought it would hurt career”, and “did not feel the need to take any leave.”

There are additional items assessing relationship support at W4, but only the items that are consistently asked at each wave (W2–W4) are used.

An additional category was included for single fathers in longitudinal analyses to account for families in which mothers no longer reside with the focal child. Supplementary analyses in which only W1 relationship status was used produced results that are consistent with those presented.

Generalized ordered logistic regression is used to predict relationship quality because the proportional odds assumption (i.e., that the relationship between all pairs of ordered groups – excellent vs. other options, very good vs. other options, etc. – is the same, resulting in only one set of coefficients for the model) is violated in these models by numerous control variables. Generalized ordered logistic regression models allow the proportional odds assumption to be relaxed for variables that violate this assumption, resulting in one set of coefficients for variables that do not violate the assumption, and separate coefficients for each pair of ordered groups for variables that violate the assumption (Williams 2016). Results for variables that do not violate the assumption are included in Table 2, and full results can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S2).

Weights are not used for a number of reasons (national weights not available for the full sample, the complex weights are not compatible with multiple imputation, etc.). In supplementary analyses using the city weights (making the data representative of births in the 18 cities used in this study), 84% of fathers took time off of work following a birth, and average length of time off was 1.13 weeks.

We considered the possibility that time off work may also be associated with relationship stability in supplementary analyses. Life table estimates suggest that the odds of relationship dissolution are lower among romantically involved couples in which the father takes time off work (and longer periods of time off), but these relationships only persist for married couples in multivariate models. Given the complexity of these analyses, a focus on relationship stability is outside of the scope of this study but should be more fully considered in future research.

Contributor Information

Richard J. Petts, Ball State University.

Chris Knoester, The Ohio State University.

References

- Albiston Catherine and Lindsey Trimble O’Connor. 2016. “Just Leave.” Harvard Women’s Law Journal 39:1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aumann Kerstin, Galinsky Ellen, and Matos Kenneth. 2011. “The New Male Mystique.” Families and Work Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel Ann P., Rossin-Slater Maya Ruhm Christopher J., Stearns Jenna, and Waldfogel Jane. 2018. “Paid Family Leave, Fathers’ Leave-Taking, and Leave-Sharing in Dual-Earner Households.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37:10–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing. 2007. “Parents’ Relationship Status Five Years After a Non-Marital Birth.” Fragile Families Research Brief Number 39, Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne M., Robinson John P., and Milkie Melissa A.. 2006. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bratberg Espen and Naz Ghazala. 2014. “Does Paternity Leave Affect Mothers’ Sickness Absence?” European Sociological Review 30:500–511. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Natasha J., Fagan Jay and Farrie Danielle. 2008. “Explaining the Long Reach of Fathers’ Prenatal Involvement on Later Paternal Engagement.” Journal of Marriage and Family 70:1094–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Daniel L., Hanson Sarah, and Fitzroy Andrea. 2016. “The Division of Child Care, Sexual Intimacy, and Relationship Quality in Couples.” Gender & Society 30:442–466. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Daniel L., Miller Amanda J., and Sassler Sharon. 2018. “Stalled for Whom? Change in the Division of Particular Housework Tasks and their Consequences for Middle- to Low-Income Couples.” Socius. doi: 4:2378023118765867. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Pilkauskas Natasha V., McLanahan Sara S., and Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. 2011. “Couples as Partners and Parents Over Children’s Early Years.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73:317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., McLanahan Sara S., and Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. 2008. “Coparenting and Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement with Young Children After a Nonmarital Birth.” Demography 45:461–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo Matias D. 2010. Efficient Semiparametric Estimation of Multi-valued Treatment Effects under Ignorability. Journal of Econometrics 155:138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J., Chase-Lansdale P. Lindsay, and McRae Christine. 1998. “Effects of Parental Divorce on Mental Health Throughout the Life Course.” American Sociological Review 63:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sells Coon, Tamara G. and Ganong Lawrence. 2017. “Emerging Adults’ Expectations and Preferences for Gender Role Arrangements in Long-Term Heterosexual Relationships.” Sex Roles 76:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan Carolyn Pape, Cowan Philip A., Heming Gertrude, Garrett Ellen, Coysh William S., Curtis-Boles Harriet, and Boles Abner J. III. 1985. “Transitions to Parenthood: His, Hers, and Theirs.” Journal of Family Issues 6:451–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]