Abstract

Chloroplasts are responsible for biosynthesis of salicylic acid (SA) an important signal molecule in plant immunity. EDS5 is a homolog of the MATE (multidrug and toxic compound extrusion) family of transporters, and is essential for SA biosynthesis. It has been speculated that EDS5 would be involved in the export of SA from chloroplasts. However, the subcellular localization of EDS5 remains largely uncharacterized. We demonstrate here that EDS5 is specifically localized to the chloroplast envelope membrane in Arabidopsis. In addition, we found that EDS5 is preferentially expressed in epidermal cells. These findings suggest that EDS5 is responsible for transport of SA from chloroplasts to the cytoplasm in epidermal cells.

Keywords: salicylic acid, chloroplast, chloroplast envelope, mate transporter, EDS5, epidermis

Introduction

Salicylic acid (SA) is a phytohormone that plays a critical role in plant immunity.1 In response to pathogen infection, SA levels increase drastically within a few hours. SA accumulation leads to activation of a set of SA-dependent defense responses, including differential expression of defense genes, such as pathogen-related (PR) genes and increases in the levels of phenolics and phytoalexines,2 which limit the growth of virulent pathogens in susceptible plants. Thus, SA is a central signaling molecule controlling plant innate immunity.

Chloroplasts play a critical role in SA biosynthesis in plants.3 SA consists of an aromatic ring bearing a hydroxyl group and originates from chorismate, the end product of the shikimate pathway in chloroplasts. There are two distinct pathways that produce SA from chorismate in plants; the isochorismate (IC) pathway and the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) pathway. It has been shown that the IC pathway plays a central role in the immunity-related SA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana, whereas the PAL pathway is likely responsible for SA biosynthesis in Nicotiana tobacum. In the IC pathway, chorismate is converted to SA through an IC intermediate by isochorismate synthase (ICS) in chloroplasts. Arabidopsis encodes two chloroplast-localized ICSs, ICS1 and ICS2, which are 57% identical to a bacterial (C. roseus) ICS. IC is subsequently converted to SA by isochorismate pyruvate lyase (IPL) in bacteria. Plant enzymes with IPL activity remain to be identified. However, it has been speculated that chloroplasts would be responsible for the conversion of IC to SA in Arabidopsis. In agreement, a recent study revealed that SA is synthesized in chloroplasts, but not in the cytoplasm, in Arabidopsis.4

Several mutants that are unable to establish defense responses have been identified through genetic analysis in Arabidopsis. In addition to ICS1 (Sid2), EDS1, a protein with homology to lipases, and another lipase-domain containing protein, PAD4, are physically-interacting proteins that are required for SA synthesis in response to some pathogens. It has also been shown that EDS5 is required for SA accumulation.5,6 EDS5 encodes an intra-membrane protein homologous to members of the MATE (multidrug and toxin extrusion) transporter family.7 Plant MATE proteins are involved in detoxification and/or transport of endogenous secondary metabolites.8 It was shown previously that EDS5-GFP fusion proteins are targeted to chloroplasts.9 Therefore, it is expected that EDS5 is localized to the chloroplast envelope membrane and may be involved in transporting SA and/or SA precursors from chloroplasts to the cytoplasm.10 However, a plastid envelope location of Arabidopsis EDS5 remains uncharacterized. In this study, we show that EDS5 is indeed specifically localized to the envelope membrane of chloroplasts. Furthermore, we found that EDS5 is preferentially expressed in epidermal cells, suggesting a possible role for epidermal cells in plant immune responses.

Results

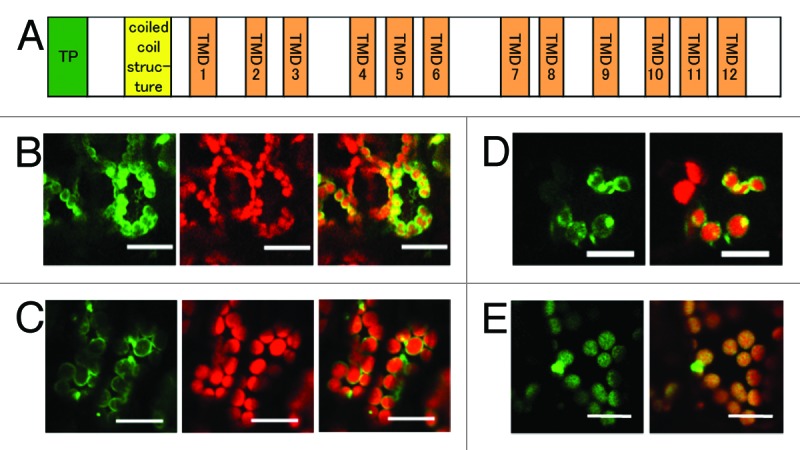

EDS5 is a member of the MATE transporter family and is predicted to have 11 membrane-spanning domains corresponding to TMDs 1 to 7 and 9 to 12 in the NORM protein from V. parahemolyticus (Fig. 1A).8,11 Furthermore, EDS5 has a hydrophilic coil domain and a putative chloroplast transit peptide at the N terminus. We cloned an EDS5 cDNA and GFP was fused to the C-terminal end of EDS5 to allow the study of the subcellular and sub-organellar localization of EDS5 in intact cells. This EDS5-GFP fusion protein was expressed under the control of a constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35S:ESD5-GFP). We speculate that EDS5-GFP would be localized to the chloroplast envelope. In agreement, in the transient expression assays using a Fast Agro-mediated Seedling Transformation (FAST) technique,12 the outlines of chloroplasts exhibited strong green fluorescence in the cells expressing EDS5-GFP (Fig. 1B). Chloroplast envelope targeting of EDS5 was further confirmed by subcellular localization of a GFP fusion protein in stable transgenic Arabidopsis plants (35S:ESD5-GFP). EDS5-GFP exhibited circumferential fluorescence with occasional brighter foci (Fig. 1C). The EDS5-GFP fusion proteins were not targeted to any other organelles. The localization of EDS5-GFP was similar to that of MSL3-GFP, which encodes a chloroplast envelope-localized mechano-sensitive channel (Fig. 1D),13 but was not similar to the thylakoid membrane-localized CAS-GFP, which shows a uniform distribution of GFP fluorescence within the chloroplasts (Fig. 1E).14 These results indicate that EDS5 is localized to the chloroplast envelope.

Figure 1. Localization of the EDS5-GFP fusion protein in the chloroplast envelope. (A) Schematic structure of Arabidopsis EDS5. EDS5 has 12 trans membrane domains (TMDs) in addition to a putative chloroplast transit peptide (TP) and a coiled-coil structure at the N-terminal region. (B) Arabidopsis cotyledons transiently expressing EDS5-GFP fusion proteins using the FAST technique. (C) Stable expression of EDS5-GFP fusion proteins driven by the CaMV 35S promoter in Arabidopsis leaves. GFP fluorescence is specifically detected at the marginal region of chloroplasts in both transiently and stably expressing plants (B and C). (D) Transient expression of MSL3-GFP fusion proteins in Arabidopsis cotyledons using the FAST technique. (E) Stable expression of CAS-GFP fusion proteins driven by the CaMV 35S promoter in Arabidopsis leaves. Scale bar, 20 µm.

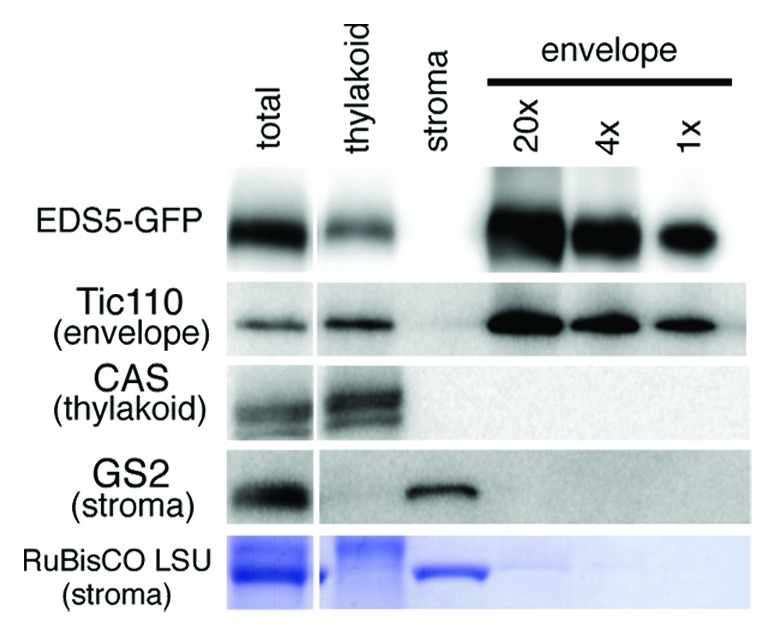

To validate the chloroplast envelope location of EDS5, we performed immunoblotting using highly purified chloroplast envelope membranes from transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing EDS5-GFP under the control of the 35S promoter (35S:EDS5-GFP). We prepared envelope membranes from purified intact chloroplasts via chloroplast lysis in a hypotonic medium followed by centrifugation on sucrose gradients.15 The yellow color of the purified envelope fraction indicated that it contained almost no chlorophyll and, thus, very few contaminating thylakoids. Indeed, Tic110, a well-known marker protein of the chloroplast inner envelope, was detected in the purified envelope fraction, but the thylakoid membrane-specific protein CAS14,16,17 was not (Fig. 2). Furthermore, neither the envelope nor the thylakoid membranes were contaminated with stromal proteins, including glutamine synthetase2 (GS2) and RuBisCO. Taken together, these results indicate that the envelope membranes were highly purified and contained almost no contamination of thylakoid and stroma proteins, although the thylakoid membranes were slightly contaminated with envelope membranes. As shown in Figure 2, the expected 81 kDa band corresponding to EDS5-GFP fusion protein was detected using anti-GFP antibody in the purified envelope membranes, and a weak signal was present in the thylakoid membrane fraction. No signal was detected using anti-GFP antibody in non-transgenic Arabidopsis (data not shown). Taken together, we conclude that EDS5-GFP fusion proteins reside specifically in the chloroplast envelope membranes.

Figure 2. Immunoblot analysis of sub-chloroplast localization of EDS5-GFP. Chloroplasts isolated from 35S:EDS5-GFP plants were subfractionated into thylakoid membranes, stroma and envelope membranes. Fractions corresponding to 0.0065 mg chlorophyll were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis using anti-GFP (for EDS-GFP), anti-Tic110 (chloroplast envelope marker), anti-CAS (thylakoid membrane marker) and anti-GS2 (stroma marker) antibodies and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies. EDS5-GFP fusion proteins are specifically accumulated in the chloroplast envelope membranes.

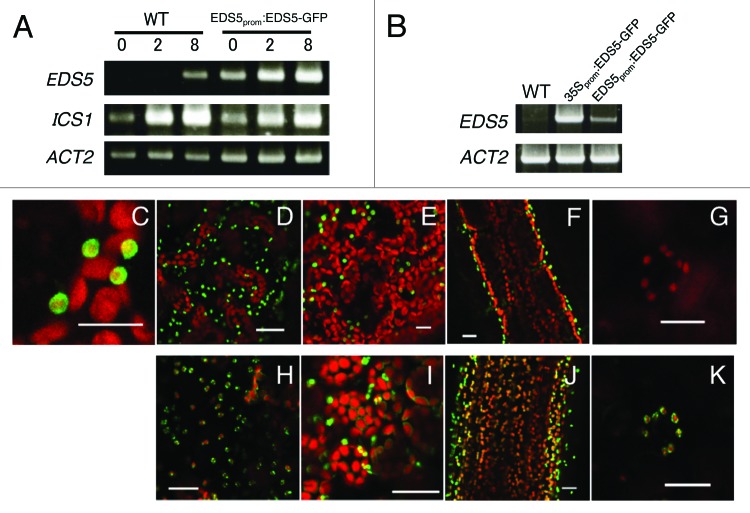

To examine the expression and localization of EDS5 in Arabidopsis further, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing EDS5-GFP driven by its own promoter (EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP). As shown in Figure 3A, bacterial elicitor flg22 activated expression of the EDS5 gene in EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP plants within 2 h, although its expression was significantly higher than that of the endogenous EDS5 gene, indicating that the 1500 bp region of the EDS5 promoter used in the construct was functional and sufficient for elicitor-induced expression. As shown in Figure 3C, EDS5-GFP fusion proteins are localized in the periphery of chloroplasts in EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP plants, confirming chloroplast envelope localization of EDS5. Interestingly, EDS5 promoter-driven EDS5-GFP fusion protein accumulated predominantly in the chloroplasts of epidermal cells, but not in those of mesophyll and stomatal guard cells (Fig. 3D–G), suggesting that EDS5 gene might be expressed preferentially in epidermal cells. Similarly, very strong EDS5-GFP expression was also observed in chloroplasts of the epidermal cells in the 35S:ESD5-GFP plants (Fig. 3B, H and I). On the other hand, chloroplasts had weak but significant GFP fluorescence in 35S:ESD5-GFP mesophyll (Fig. 3I and J) and guard cells (Fig. 3K), suggesting that the epidermal cell-specific expression of EDS5 is regulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.

Figure 3. Preferential expression of EDS5-GFP in the epidermis of Arabidopsis. (A) flg22-induced expression of EDS5 in wild type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing EDS5-GFP from the EDS5 promoter. Plants were treated with 1 μM flg22 for 2 and 8 h. ACT2 is shown as a control. (B) Overexpression of EDS5 in 35S:EDS5-GFP transformants. (C–G) Localization of the EDS5–GFP in epidermis cells (C and D), mesophyll cells (E), the inflorescence stem (F) and guard cells (G) of EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP transformants. (H–K) Localization of the EDS5-GFP in epidermis cells (H), mesophyll cells (I), the inflorescence stem (J) and guard cells (K) of 35S:EDS5-GFP transformants. Scale bar, 20 µm.

Discussion

EDS5 encodes a MATE-type transporter, which are widely distributed in all kingdoms of living organisms, including bacteria, fungi, animals and plants.10,11 MATE-type transporters are responsible for multidrug resistance in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes through the extrusion of xenobiotics and toxic metabolites from cells. Although MATE-type transporters constitute rather small families in bacteria and animals, they are encoded by a large family with 58 members in the Arabidopsis genome,8,11 suggesting their crucial roles in detoxification and/or transport of endogenous secondary metabolites in plants. Phylogenetic analysis of the MATE-type transporters demonstrates that the family can be divided into three subfamilies, bacterial (Family 1), eukaryotic (Family 2), and bacterial and archeatic (Family 3).11,18 Eukaryotic Family 2 is further divided into four subgroups: yeast and fungi, plants, animals and protozoan MATE subgroups. Although most plant MATE proteins belong to the plant-specific subgroup of the Family 2 (Family 2 plant MATE), a small number of plant MATE proteins (six proteins in Arabidopsis), including EDS5, form a small subgroup, which belongs to the bacteria/archea Family 3 (Family 3 plant MATE).18 The Family 3 plant MATE proteins cluster loosely with bacterial proteins.11 Interestingly, most of the Family 3 plant MATE transporters have been identified in plastid proteomes or predicted to target to plastids. Furthermore, we revealed that the Family 3 EDS5 is localized to the chloroplast envelope (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the Family 2 plant MATE proteins seem to be localized in other membranes including vacuoles and plasma membranes (sFigure 1). It is assumed that the Family 3 plant MATE transporters are derived from bacterial proteins probably through endosymbiotic gene transfer, and mainly function in plastids to export secondary metabolites of plastids. On the other hand, the Family 2 plant MATE transporters may be responsible for transporting a wide range of secondary metabolites from the cell or to vacuoles.

Plant MATE proteins are involved in the transport of secondary metabolites and xenobiotics through an H+ exchange mechanism in various biological processes, such as secondary metabolites accumulation, aluminum tolerance, iron homeostasis and detoxification of toxic molecules.8 On the other hand, EDS5 is implicated in SA-dependent disease resistance signaling.7 It has been suggested that SA is synthesized from chorismate by means of chloroplast-localized ICS.3,4 Furthermore, a recent study has shown that SA biosynthesis takes place mainly inside the chloroplasts.4 However, transporters involved in the export of SA from chloroplasts have not been identified. In this study, we demonstrated that EDS5 is localized to the envelope membranes of chloroplasts. EDS5 is essential for SA biosynthesis and has been suggested to be involved in SA export from chloroplasts.5,6 Although no substrates of EDS5 have been established to date, these facts suggest that SA might be exported from chloroplasts through EDS5 localized in the chloroplast envelope.

This study further showed that EDS5 is predominantly expressed in epidermis, but not in mesophyll cells or guard cells in leaves, based on epidermal cell-specific accumulation of EDS5-GFP proteins in EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP plants. In fact, EDS5 gene expression has been reported to be 2.7-fold higher in epidermal cells of the stem than in the stem overall.19 Epidermal cells might play a special role in protection and environmental sensing, since the epidermis is the first boundary between the plant and the external environment. Indeed highly expressed genes in stem epidermis encode proteins involved in defense against pathogens, such as the pathogenesis-related proteins (PR-5 and PR-2), the Leu-rich repeat transmembrane receptor kinase FSL2, defense-related transcription factors (WRKY18, WRKY33, WRKY75, CBP60 g).19 Since EDS5 is likely essential for SA export from chloroplasts,5,6 our findings further suggest the role of epidermal cells in plant immunity. In addition, EDS5-GFP fusion proteins accumulated preferentially in epidermal cells in 35S:ESD5-GFP plants as well, although the CaMV 35S promoter provides strong constitutive expression in most plants. Thus, the epidermal cell-specific expression of EDS5 is likely due to both transcriptional and post-transcriptional control.

Materials and Methods

Arabidopsis thaliana wild-type Columbia ecotype and transgenic plants were germinated and grown on 1/2 strength MS medium containing 0.8%(w/v)agar at 22°C with 16 h light (80 to 100 μmol m-2 s-1)/8 h dark cycles for 1 to 2 weeks. For Chloroplast sub-fractionation experiments, 7- to 8-weeks-old EDS5-GFP plants grown on soil with 16 h light (80 to 100 μmol m-2 s-1)/8 h dark cycles were used.

EDS5 and GFP fusion genes under the control of CaMV 35S promoter were constructed as follows. The full length EDS5 cDNA fragment was ligated in frame with the sGFP (S65T) fragment. The resulting EDS5 and GFP fusion gene was transferred into PGWB405 vector. The EDS5 promoter:GFP expression plasmid was constructed as follows: A 1,500 bp EDS5 promoter fragment was fused to a promoterless EDS5-GFP gene and transferred into PGWB405 vector. to give the EDS5prom:EDS5-GFP construct. The resulting constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and used to transform wild-type Arabidopsis (Col-0) by flower dipping. Kanamycin-resistant T1 transformants were then selected and used for further analyses. The chimeric gene was also introduced into plant cells for transient assays by using a Fast Agro-mediated Seedling Transformation (FAST) technique.12

Two-week-old WT and EDS5-GFP overexpressing plants were floated on 1/2 strength MS medium for 1 d (0 h) in the light, and then treated with 1 μM flg22 for 2 h and 8 h. Total RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were performed with following primers: EDS5 forward (5′-CCAAACACTGGTCGCAGAAT-3′) and reverse (5′-TATGCCTCCAGGCGAAAGAAGCCGTCGT-3′); ICS1 forward (5′-CGCCTGAGAGACTATTCCAAAG-3′) and reverse (5′-CCCCGCATAGATCAATGCCCA-3′); and ACT2 forward (5′-GGCCGATGGTGAGGATATTCAGCCACTTG-3′) and reverse (5′-TCGATGGACCTGACTCATCGTACTCACTC-3′).

Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplasts were isolated by the direct homogenization method as described (Kikuchi et al., 2009). Isolated intact chloroplasts were lysed in a hypotonic buffer [10 mM HEPES-KOH(pH7.8), 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Protease Inhibitor Cocktail(v/v)] for 5min on ice. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 3000 x g at 4°C for 5 min. The pellets containing thylakoids were washed twice in hypotonic buffer. The supernatant containing envelope was layered over a sucrose step gradient composed of 1 M and 0.46 M sucrose (in TE buffer) and sedimented at 70,000 × g at 4°C. The envelope fraction was collected from the boundary between 1 M and 0.46 M sucrose, diluted with TE buffer and centrifuged at 72,000 g at 4°C for 30 min. The pellets were suspended in 2× SDS sample buffer [100 mM Tris, pH6.8, 4%SDS (w/v), 20% glycerol (w/v), 10% β-mercaptoethanol (v/v)] and centrifuged at 10,0000 g at 4°C for 10 min. Samples were denatured in 2× SDS sample buffer at 37°C for 30 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. GFP, Tic110, CAS and GS were detected by incubation with the appropriate primary antibody and then an AP-linked chemiluminescent reagent system.

GFP fluorescence and chlorophyll autofluorescence images were detected using confocal microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- IC

isochorismate

- IPL

isochorismate pyruvate lyase

- ICS

isochorismate synthase

- MATE

multidrug and toxic compound extrusion

- PAL

phenylalanine ammonia-lyase

- SA

salicylic acid

- TMD

trans membrane domain

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank M.H. Sato, Y. Nakahira and Y. Ishizaki for helpful discussion. This work was supported by a Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry for Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and technology (MEXT) of Japan (No. 22370022 and 24657036) to T.S. and by an Adaptable and Seamless Technology transfer Program through target-driven R&D (A-STEP) from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

References

- 1.An C, Mou Z. . Salicylic acid and its function in plant immunity. J Integr Plant Biol 2011; 53:412 - 28; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01043.x; PMID: 21535470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loake G, Grant M. . Salicylic acid in plant defence--the players and protagonists. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2007; 10:466 - 72; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.008; PMID: 17904410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dempsey DA, Vlot AC, Wildermuth MC, Klessig DF. . Salicylic Acid biosynthesis and metabolism. Arabidopsis Book 2011; 9:e0156; PMID: 22303280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fragnière C, Serrano M, Abou-Mansour E, Métraux JP, L’Haridon F. . Salicylic acid and its location in response to biotic and abiotic stress. FEBS Lett 2011; 585:1847 - 52; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.039; PMID: 21530511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nawrath C, Métraux JP. . Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 1999; 11:1393 - 404; PMID: 10449575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng G, Seabolt S, Zhang C, Salimian S, Watkins TA, Lu H. . Genetic dissection of salicylic acid-mediated defense signaling networks in Arabidopsis. Genetics 2011; 189:851 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.111.132332; PMID: 21900271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nawrath C, Heck S, Parinthawong N, Métraux JP. . EDS5, an essential component of salicylic acid-dependent signaling for disease resistance in Arabidopsis, is a member of the MATE transporter family. Plant Cell 2002; 14:275 - 86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.010376; PMID: 11826312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishihara T, Sekine KT, Hase S, Kanayama Y, Seo S, Ohashi Y, et al. . Overexpression of the Arabidopsis thaliana EDS5 gene enhances resistance to viruses. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2008; 10:451 - 61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00050.x; PMID: 18557905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah J. . The salicylic acid loop in plant defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2003; 6:365 - 71; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00058-X; PMID: 12873532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omote H, Hiasa M, Matsumoto T, Otsuka M, Moriyama Y. . The MATE proteins as fundamental transporters of metabolic and xenobiotic organic cations. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006; 27:587 - 93; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.001; PMID: 16996621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yazaki K, Sugiyama A, Morita M, Shitan N. . Secondary transport as an efficient membrane transport mechanism for plant secondary metabolites. Phytochem Rev 2008; 7:513 - 24; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11101-007-9079-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li JF, Park E, von Arnim AG, Nebenführ A. . The FAST technique: a simplified Agrobacterium-based transformation method for transient gene expression analysis in seedlings of Arabidopsis and other plant species. Plant Methods 2009; 5:6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1746-4811-5-6; PMID: 19457242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haswell ES, Meyerowitz EM. . MscS-like proteins control plastid size and shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol 2006; 16:1 - 11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.044; PMID: 16401419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura H, Komori T, Kobori M, Nakahira Y, Shiina T. . Evidence for chloroplast control of external Ca2+-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transients and stomatal closure. Plant J 2008; 53:988 - 98; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03390.x; PMID: 18088326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kikuchi S, Oishi M, Hirabayashi Y, Lee DW, Hwang I, Nakai M. . A 1-megadalton translocation complex containing Tic20 and Tic21 mediates chloroplast protein import at the inner envelope membrane. Plant Cell 2009; 21:1781 - 97; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1105/tpc.108.063552; PMID: 19531596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinl S, Held K, Schlücking K, Steinhorst L, Kuhlgert S, Hippler M, et al. . A plastid protein crucial for Ca2+-regulated stomatal responses. New Phytol 2008; 179:675 - 86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02492.x; PMID: 18507772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vainonen JP, Sakuragi Y, Stael S, Tikkanen M, Allahverdiyeva Y, Paakkarinen V, et al. . Light regulation of CaS, a novel phosphoprotein in the thylakoid membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS J 2008; 275:1767 - 77; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06335.x; PMID: 18331354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hvorup RN, Winnen B, Chang AB, Jiang Y, Zhou XF, Saier MH Jr.. . The multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide (MOP) exporter superfamily. Eur J Biochem 2003; 270:799 - 813; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03418.x; PMID: 12603313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suh MC, Samuels AL, Jetter R, Kunst L, Pollard M, Ohlrogge J, et al. . Cuticular lipid composition, surface structure, and gene expression in Arabidopsis stem epidermis. Plant Physiol 2005; 139:1649 - 65; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1104/pp.105.070805; PMID: 16299169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.