Abstract

Oral rabies vaccination (ORV) is highly effective in foxes and raccoon dogs, whereas for unknown reasons the efficacy of ORV in other reservoir species is less pronounced. To investigate possible variations in species-specific cell tropism and local replication of vaccine virus, different reservoir species including foxes, raccoon dogs, raccoons, mongooses, dogs and skunks were orally immunised with a highly attenuated, high-titred GFP-expressing rabies virus (RABV). Immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR screenings revealed clear differences among species suggesting host specific limitations to ORV. While for responsive species the palatine tonsils (tonsilla palatina) were identified as a main site of virus replication, less virus dissemination was observed in the tonsils of rather refractory species. While our comparison of vaccine virus tropism emphasizes the important role that the tonsilla palatina plays in eliciting an immune response to ORV, our data also indicate that other lymphoid tissues may have a more important role than originally anticipated. Overall, these data support a model in which the susceptibility to oral live RABV vaccine infection of lymphatic tissue is a major determinant in vaccination efficacy. The present results may help to direct future research for improving vaccine uptake and efficacy of oral rabies vaccines under field conditions.

Subject terms: Live attenuated vaccines, Virus-host interactions

Introduction

Rabies is a primary example of how oral vaccination aids to the control and elimination of an infectious disease with zoonotic or economic relevance, particularly with regards to wildlife. In principle, vaccination of wildlife reservoir species should result in a herd immunity above a threshold where the transmission cycle of the disease ceases to persist1,2. While wildlife rabies in Eurasia is mainly associated with foxes and raccoon dogs3, in the Americas, raccoons and skunks both serve as major reservoir species and potent transmitter of the disease to domestic animals4. Another important reservoir in the Caribbean and Southern Africa are mongooses5.

The domestic dog represents the main reservoir and source of infection for humans, particularly in developing countries in Africa and Asia6. Oral vaccination of free-roaming dogs is considered an important complementary tool to increase herd immunity and thus the likelihood of disease elimination7.

Field effectiveness of oral vaccination campaigns is influenced by factors such as the composition of vaccine-loaded baits and a strategy of bait distribution. Another important component is the use of an efficacious and safe oral rabies vaccine. While oral rabies vaccination campaigns using either attenuated or recombinant vaccines have been successful in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) and coyotes (Canis latrans) in North America8–10 and in red foxes and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in Europe3,11, there seems to be inefficient or variable efficacy of oral immunisation in some other target species12. In fact, there is limited success in the oral vaccination of raccoons (Procyon lotor) and striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis) as shown experimentally13–16 and in field applications17. While relatively low minimum effective vaccine virus titres (<108.0 focus forming units (FFU)/mL) are needed for responsive species including foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses (Herpestes auropunctatus)18–23, skunks and raccoons seem to be rather refractory to oral rabies vaccination, even when high virus titres were administered13,16,24–28. Also relatively high doses were needed to successfully immunise dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) by the oral route14,29–33.

Since the gastro-intestinal tract will rapidly inactivate and degrade the enveloped rabies virus, vaccine virus must be taken up in the oral cavity for the development of an immune response34. Despite the broad application of oral rabies vaccines over the last decades, it is still not fully understood if and where oral rabies vaccine viruses replicate in the oral cavity of the target species.

The Waldeyer’s ring is a ringed arrangement of lymphoid organs in the pharynx and consists of various tonsils35. In particular, the t. palatina is assumed to function as the main site for vaccine virus uptake and replication and therefore, appears to play a critical role in eliciting an effective immune response36. However, data are still sparse and the results obtained from the few experimental studies are contradictory. In foxes and dogs for example, the t. palatina was shown to be infected by attenuated rabies vaccine viruses36–38. However, these observations were contradicted by another study in which rabies vaccine virus could not be detected in the t. palatina of small Indian mongoose39. Also in the striped skunk, vaccine virus was less frequently detected after oral administration than in red foxes during a comparative study36. The latter findings suggested less efficient uptake or infection by vaccine virus in the t. palatina leading to insufficient immunity to rabies in this reservoir species16,26–28,40–42.

Against the background of the biological diversity among reservoir species for rabies involving representatives of the families of Canidae, Procyonidae, Herpestidae, Mephitidae, Viverridae, and Mustelidae43 and the lack of knowledge regarding species-specific vaccine uptake in the oral cavity, further studies are needed to investigate vaccine virus entry and replication in the t. palatina of those species36. Therefore, in this study our primary objective was to elucidate the detailed time course of vaccine virus infection in the t. palatina of the most important rabies reservoir species, e.g. red foxes, raccoon dogs, mongooses, raccoons, dogs and skunks, after oral application by conducting comparative experimental in vivo tracking studies. To this end, we used a highly attenuated and high titred GFP-labelled vaccine virus construct, followed by confocal laser-scan microscopy to visualize and assess differences between various important reservoir species. Prior to this full comparative study, we performed a pilot study to confirm that the results obtained with an attenuated vaccine virus strain36 were reliable using the genetically modified virus. Another objective was to answer the question whether tissues of the oropharyngeal tract other than the t. palatina are also involved in mediating immunity after oral vaccination by detecting the presence of viral RNA and viable virus using highly sensitive molecular diagnostic techniques. To this end, we analysed the anatomical and histological structure of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) and Waldeyer’s ring to detect whether differences observed could have an impact on vaccine uptake efficiency.

Results

Restricted replication and limited spread of vaccine virus (SAD L16 GFP) infection in the t. palatina after oral inoculation of red foxes

Previous studies demonstrated that the t. palatina is a main target tissue for infection by orally administered RABV vaccines36–38. In the pilot study, we focused on the red fox as the species, which is very responsive to oral rabies vaccination. Here, we proved the suitability and functionality of the Green-Fluorescence-Protein (GFP) expressing model vaccine virus (SAD L16 GFP; Fig. 1a) for in vivo tracking to closely follow the kinetics and spread of vaccine virus in the oral cavity immediately after application.

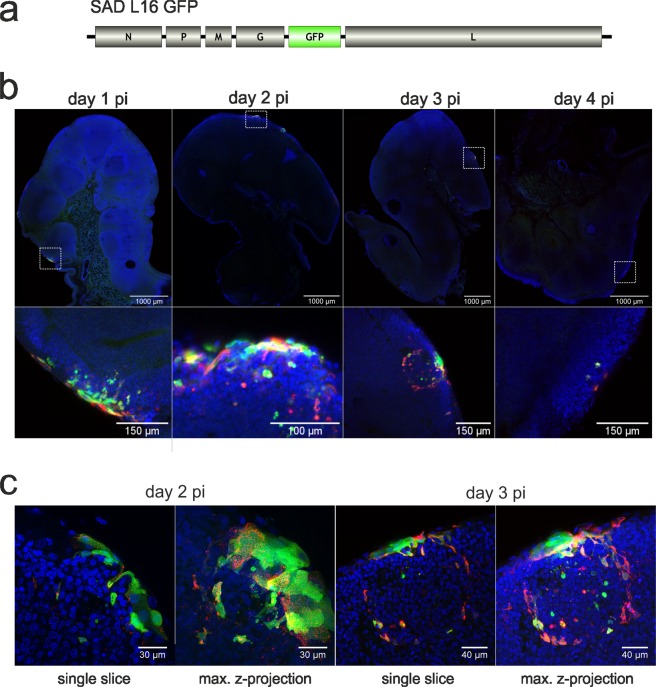

Figure 1.

Spatio-temporal resolution of SAD L16 GFP infection in the t. palatina of foxes at day 1–4 post inoculation. (a) Genome organisation of the virus construct SAD L16 GFP. (b) Detection of virus infected cells in 150 µm vibratome slices by GFP auto-fluorescence (green) and immunostaining for RABV nucleoprotein N (red). Blue: Nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. Top: Mosaic overview images generated from confocal tile scans performed with at low magnification (20x objective). Bottom: details from mosaic images shown. (c) Higher resolution images of individual infection foci at days 2 and 3 pi. Shown are single optical slices (left side) and maximum z-projections of confocal z-stacks.

In the pilot as well as in the full comparative study using a standardised approach, foxes inoculated orally with a GFP expressing vaccine virus were screened for the presence of vaccine virus at day 1, 2, 3, 4 and 10 post inoculation (pi). Confocal laser-scan microscope analysis was performed to detect both, GFP and RABV N protein, in vibratome slices of retropharyngeal tissues. Whereas GFP expression was not detectable in mucosa, tongue or lymph node tissues at any time point, GFP positive cells were present in all tonsils taken at day 1 to 4 pi (Fig. 1b). While at days 1 to 3 pi larger foci of infection were predominant, at day 4 pi only single GFP and N protein positive cells could be detected (Fig. 1b).

Already at day 1 pi, infection foci were detected in peripheral cell layers of the tonsils (Fig. 1b). In the following days pi, the size of infection foci in the epithelial cell layers did not increase and the virus did not infect deeper follicular and parafollicular areas of the lymphatic tissue, suggesting restricted replication and very limited spread of vaccine virus infection in of foxes. RABV N protein was associated with GFP positive cells (Fig. 1b) at day 1 pi, confirming that green fluorescence observed was proof of virus infection. When having a closer look at later time points (day 2, 3 pi), the ratio of GFP and N protein specific signals shifted towards increased detection of N protein (Fig. 1c), suggesting different kinetics of GFP and N protein accumulation and turnover in infected cells.

Vaccine virus tropism and infection of the t. palatina differs among various target species

Since there is evidence that the efficacy of oral rabies vaccination varies between reservoir species, we compared the tropism of SAD GFP virus in the t. palatina after oral inoculation between six reservoir species. We classified species by whether or not they require a low dose (red fox, raccoon dog and small Indian mongoose) or a high dose (raccoons, dogs and striped skunks) for successful vaccination, based on previous literature. These species were inoculated using the same standardized approach described.

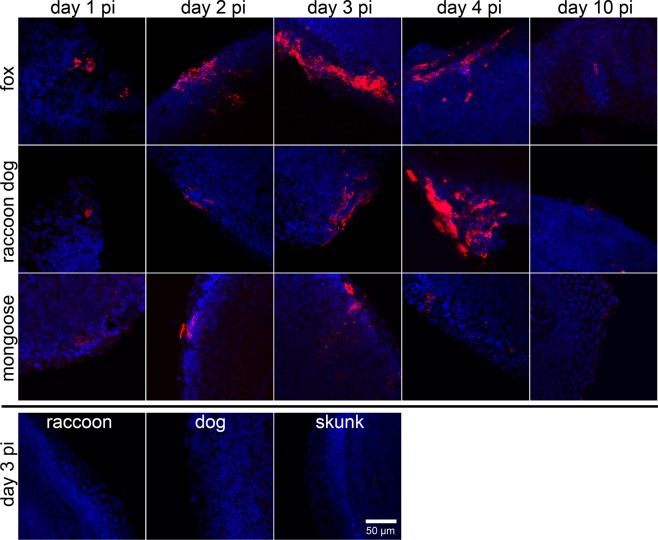

Similar to the observation in foxes (Fig. 2, upper line), in other responsive species such as raccoon dogs and mongooses vaccine virus N protein specific fluorescence was detected in t. palatina until day 4 pi (Fig. 2, Table 1). No foci but only single vaccine virus infected cells were detectable at day 10 pi. In contrast, in the great majority of analysed tonsils of rather refractory species, i.e. raccoons, dogs and skunks, no vaccine virus specific signals were observed by laser-scan microscope imaging (Table 1), suggesting that infection of tonsil tissues in these species was strongly limited or did not even occur.

Figure 2.

Spatio-temporal resolution of SAD L16 GFP infection in foxes, raccoon dogs, mongooses, raccoons, dogs and skunks by detection of the RABV nucleoprotein detection in the t. palatina. Comparative detection of virus infected cells in vibratome tonsil slices by nucleoprotein specific immunofluorescence (red) at time of necropsy (day 1–4, 10 pi). N protein detection failed for tonsil slices of raccoons, dogs and skunks at any time point (exemplary shown for day 3 pi). Blue: cell nuclei. Maximum projections of confocal z-stacks are shown.

Table 1.

Detection of RABV nucleoprotein in the t. palatina by immunofluorescence using confocal laser-scan microscopy post inoculation.

| day 1 pi | day 2 pi | day 3 pi | day 4 pi | day 10 pi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| individual animal | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| fox | − | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | − |

| raccoon dog | + | + | − | ++ | − | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + |

| mongoose | − | + | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | ++ | − | + |

| raccoon | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| dog | + | +/− | − | +/− | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| skunk | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

At least three slices per tonsil and animal (A,B) were analysed. ++/+++: infection foci; +: single positive cells; +/−: signals questionable; −: no detection of infection foci or single infected cells.

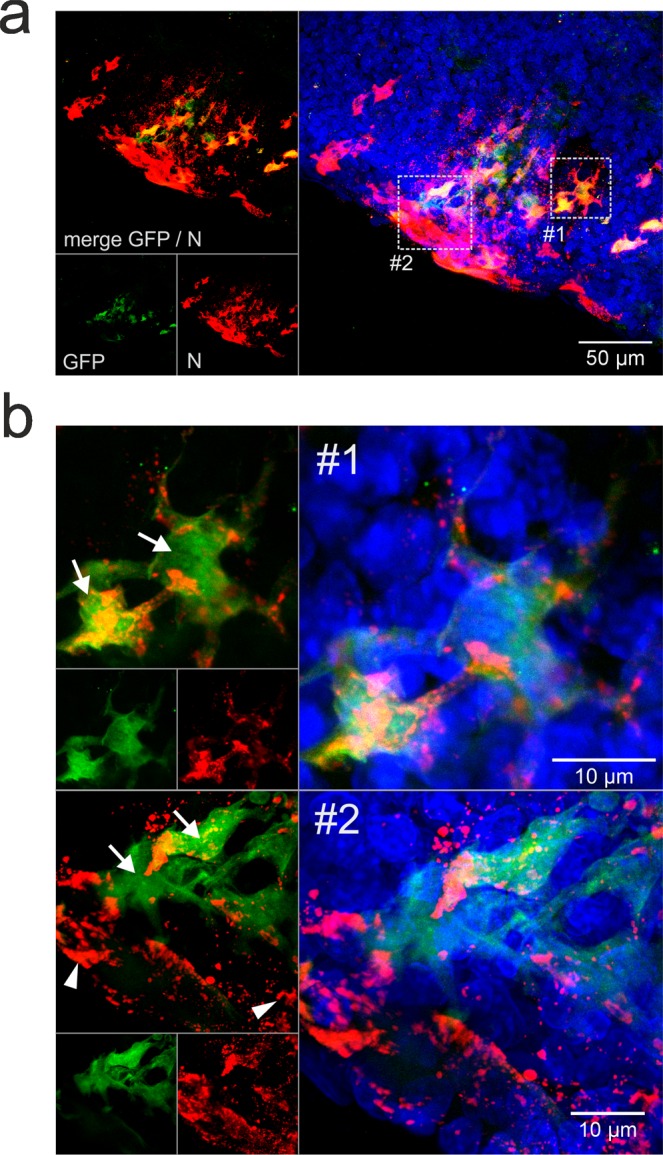

Similar to the pilot experiment depicted in Fig. 1, partial separation of GFP auto fluorescence and virus N protein specific immunofluorescence was observed, as shown by an infection focus in a fox t. palatina at day 2 pi (Fig. 3a). The details show GFP positive cells with moderate N detection (Fig. 3b, arrows) and cells with stronger N signals but without detectable GFP fluorescence (Fig. 3b, arrowheads).

Figure 3.

SAD GFP virus infection of fox t. palatina at 2 days post inoculation. (a) Focus of virus infected cells at day 2 pi. Maximum z-projection of a confocal z-stack. Green: GFP. Red: nucleoprotein (N). Blue: nuclei stained with Hoechst 33342. Dotted line boxes indicate in B shown details #1 and #2. (b) Details from A showing GFP positive cells with N signals (white arrows) and N signals without detectable GFP signals (arrowheads).

Analyzed carnivore species have a comparable anatomic configuration of Waldeyer’s ring, with minor variations in MALT

In a next step, we wanted to elucidate whether the differences observed in vaccine uptake efficiency among species can be explained by anatomical and histological differences in the morphological structure of the Waldeyer’s ring and MALT. The full comparative study started with the skunks, and a standard necropsy technique for preparation of tongue and adnexa of the Waldeyer’s ring was performed. However, this resulted in suboptimal representation of the anatomical features of Waldeyer’s ring. Therefore, we decided to variate the necropsy technique as described in materials and methods and showed in Supplementary Fig. S2 for optimal results.

All species had a comparable anatomic configuration of Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring. The current literature mainly focuses on the Waldeyer’s ring of dog species where a tonsilla (t.) lingualis, t. palatina and t. pharyngea can be differentiated44. This information is lacking for other carnivore species, therefore we comparatively investigated the presence or absence of MALT in all studied species (see Supplementary Table S1). Notably, in all studied carnivores, the t. palatina was the most prominent lymphoid structure (see Supplementary Fig. S2), followed by the t. pharyngea that was readily seen dorsocaudal of the opening of the eustachian tube as a patchy area with visible lymphoid follicles, except in the mongoose (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Histologically the entire structure is covered by a respiratory epithelium with an almost continuous basement membrane rarely infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages. A t. veli palatina or t. lingualis was not detectable in any of the studied carnivore species applying the criteria for MALT. Non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelium and a thin layer of respiratory epithelium on the nasopharyngeal side oro-pharyngeally covered the soft palate.

The t. palatina in each individual was covered by a non-keratinized squamous epithelium extensively infiltrated by lymphocytes and macrophages (lymphoepithelium). In the underlying submucosa variable prominent secondary lymphoid follicles with macrophages and interfollicular zones were seen (see Supplementary Fig. S3, left panel side). In all species, a regular structural morphology could be observed consisting of a variable thick multilayered cytokeratin positive non-keratinising squamous epithelium. Many CD20 positive B cells, fewer CD3 positive T cells and IBA1 positive macrophages, some with a dendritic cell morphology, infiltrated the lymhoepithelium (see Supplementary Fig. S3, right panel side). Frequently, interwoven nest or pockets of variable combinations of the aforementioned immune cells were observed within the squamous epithelium. RABV-nucleoprotein-positive cells were evident and predominantly confined to the non-keratinizing epithelium in 2 out of 2 foxes at 1 dpi, and in 1 out of 2 foxes at 2 and 3 dpi, respectively. Comparatively, RABV-antigen was detectable in epithelial cells in 1 out of 2 raccoon dogs at 2 dpi, and in 2 out of 2 raccoon dogs at 3 dpi. The underlying submucosal architecture showed no obvious species specific differences in the staining pattern of B cell-rich lymphoid follicles and T cell-dominated interfollicular zones.

Relative viral load in the t. palatina is moderate to low depending on the target species

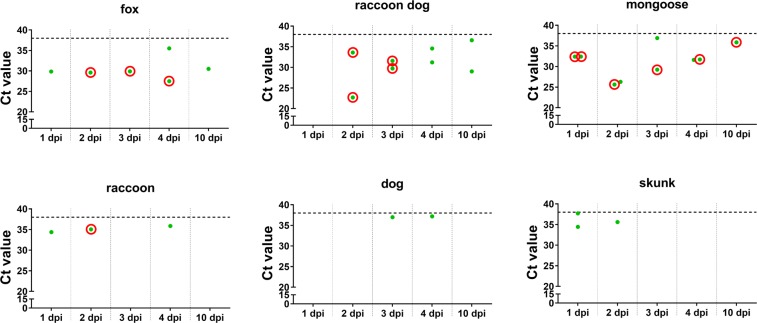

In order to establish a correlation between the vaccine virus tropism and infection in the t. palatina as observed by confocal laser-scan microscopy in the different target species (Fig. 2, Table 1), we investigated the presence of viral RNA. Vaccine virus RNA could be detected in the t. palatina of more responsive species, i.e. foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses, at almost all time points pi as opposed to raccoons, dogs and skunks (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S2). With 31.04 the mean ct-value as a surrogate for the relative viral load was significantly lower (p < 0.0004) for the more responsive group of species as compared to the rather refractory species (mean ct-value 35.89), corroborating findings of the immunofluorescence analyses. Along with the findings from RT-qPCR screenings, infectious virus could only be isolated from the t. palatina of species more responsive to oral vaccination with the exception of one raccoon at day 2 pi (Fig. 4). For foxes, viable virus was detectable from 2 to 4 dpi and for raccoon dogs at days 2 and 3 pi. Detection of viable virus was highest in the t. palatina of mongooses as infectious virus could be isolated at all time points.

Figure 4.

Detection of SAD L16 GFP in the t. palatina of different reservoir species by RT-qPCR. All animals received 108.0 FFU/mL SAD L16 GFP by direct oral instillation. SAD L16 GFP positive (green dots): Ct values < 38, SAD L16 negative: Ct values ≥ 38 (dotted line, values not shown). t. palatina, which were tested positive for RABV RNA in RT-qPCR screenings, were tested for infectious virus by RTCIT. Samples for which infectious vaccine virus could be isolated are highlighted with a red circle.

Positivity rates for the detection of vaccine virus RNA in other tissues of the oropharyngeal tract also follow the same species-specific pattern

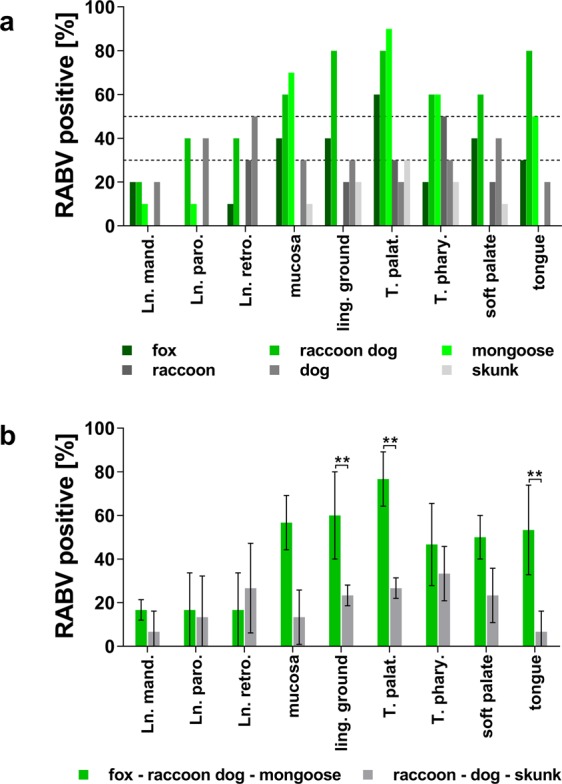

To investigate whether tissues other than the t. palatina are also involved in vaccine virus uptake, nine tissues of the oropharyngeal tract were screened by RT-qPCR. Viral RNA could be detected in all tissues, albeit with differences in positivity rates. High positivity rates were observed in the t. palatina, followed by t. pharyngea, mucosa, tongue, and lingual ground tissue (Fig. 5a). The t. palatina of foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses revealed a higher positivity rate and lower Ct-values (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Tables S4–S6) as opposed to raccoons, dogs and skunks (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Tables S7–S9). These data may indicate that both the frequency of vaccine virus infection and the relative viral load was increased in the t. palatina of foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses compared to the other species.

Figure 5.

Positivity rates of tissue samples tested by RT-qPCR for the presence of viral RNA. (a) The columns show the percentage of positive samples per species and tissue. For each species, all time points were summarised (5 time points × 2 animals, n = 10). For better orientation, dotted horizontal lines were drawn at 50% and 30%. (b) Mean positivity rates for viral RNA as demonstrated by RT-qPCR. Species were grouped according to their assumed susceptibility to oral vaccination in responsive (fox-raccoon dog-mongoose = green) and refractory (raccoon-dog-skunk = gray) species. For each group, mean rates of RT-qPCR positive tissues (mean ± s.d.; n ≥ 2) are shown. Analyses of significance in the differences between two means were calculated by two-way ANOVA followed by Šidák’s multiple comparison test. Differences between two means with p < 0.01 were considered highly significant (**). Tissue abbreviation: Lnn. mand.- lymphnodi mandibulares, Ln. paro. – lymphnodus parotideus, Ln. retro. – lymphnodus retropharyngealis, ling. ground – lingual ground, T. palat. – tonsilla pallatina (elsewhere referred to as t. palatina), T. phary. – t. pharyngea,.

When species were combined according to their assumed responsiveness to oral rabies vaccination, irrespective of the time point after inoculation, the overall positivity rate across all tissues in responsive species (54%), i.e. foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses, was higher as opposed to rather refractory species (32%), i.e. raccoons, dogs and skunks, although not statistically significant. In contrast, differences were observed for t. palatina, mucosa and tongue tissues showing significantly (p < 0.01) higher positivity rates in responsive species as compared to rather refractory species (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Table S3). Even though viral RNA was also detected in samples from lymph nodes, positivity rates did not exceed 30% in most species (Fig. 5a).

Viable vaccine virus was only detectable up to four hours post inoculation, while RNA was present up to four days post inocluation in oral swabs

In order to investigate the longevity of viral RNA and viable virus in the oropharyngeal cavity and to see whether detection of the oral rabies vaccine virus in the oropharynx and infection of particular target cells or tissues is a determinant for vaccine uptake, oral swabs were collected 2, 4 and 24 hrs pi and at the day of euthanasia. Virus detection by RT-qPCR was generally highest in oral swabs taken immediately after direct vaccine virus administration (Table 2). While except for skunks, almost all samples taken 2 hrs pi were positive for viral RNA, after 4 hrs virus detection decreased. At this time point, only oral swab samples of foxes, raccoons and dogs were still virus RNA positive, whereas the positivity rate in raccoon dogs, mongooses and skunks ranged between 30% and 70%. Sporadically, viral RNA could be detected in individuals of several species up to day 4 pi (Table 2). On the opposite, viable virus could only be found up to 4 hrs pi. Notably, virus could only be isolated from three oral swabs from skunks and no viable virus was detected in any of the oral swabs from dogs, whereas all other species had at least 12 oral swabs each during the first 4 hours with positive results (Table 2). Interestingly, almost all saliva specimen of raccoons within the first 4 hrs were positive for viable virus. This viable virus cannot be a result of active shedding of progeny vaccine virus but is merely vaccine virus administered and not yet cleared from the oral cavity.

Table 2.

Detection of vaccine virus (ct values) in oral swabs by RT-qPCR and RTCIT.

| Time p.i. | 2 h | 4 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 10 d | Time p.i. | 2 h | 4 h | 1 d | 2 d | 3 d | 4 d | 10 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR (ct-values) and virus isolation in RTCIT | |||||||||||||||

| Fox_01 | 22.2 | 29.2 | — | nd | nd | nd | — | RC_01 | 22.2 | 25.4 | 33.8 | nd | nd | nd | — |

| Fox_02 | 22.2 | 33.2 | — | nd | nd | nd | — | RC_02 | 26.6 | 34.2 | — | nd | nd | nd | — |

| Fox_03 | 19.6 | 29.9 | — | nd | nd | 28.0 | RC_03 | 30.3 | 31.0 | — | nd | nd | 30.7 | ||

| Fox_04 | 22.8 | 24.2 | — | nd | nd | 34.8 | RC_04 | 27.5 | 31.4 | 32.0 | nd | nd | — | ||

| Fox_05 | 21.1 | 29.6 | — | nd | — | RC_05 | 26.0 | 29.3 | — | nd | — | ||||

| Fox_06 | 20.2 | 30.9 | — | nd | 32.6 | RC_06 | 31.6 | 31.8 | — | nd | — | ||||

| Fox_07 | 21.4 | 33.4 | — | — | RC_07 | 33.8 | 29.4 | — | — | ||||||

| Fox_08 | 27.4 | 33.5 | — | — | RC_08 | 28.5 | 30.5 | — | — | ||||||

| Fox_09 | 27.8 | 37.9 | 36.1 | RC_09 | 27.2 | 27.7 | — | ||||||||

| Fox_10 | 24.3 | 32.6 | 35.2 | RC_10 | 31.1 | 29.7 | 34.5 | ||||||||

| RD_01 | 28.6 | 30.4 | — | nd | nd | nd | — | Dog_01 | 32.0 | 31.7 | — | nd | nd | nd | — |

| RD_02 | 30.9 | 32.6 | — | nd | nd | nd | — | Dog_02 | 32.4 | 33.3 | 35.4 | nd | nd | nd | — |

| RD_03 | 28.5 | — | — | nd | nd | — | Dog_03 | 30.3 | 31.5 | 32.8 | nd | nd | — | ||

| RD_04 | 26.0 | — | — | nd | nd | — | Dog_04 | 33.9 | 36.2 | — | nd | nd | 37.4 | ||

| RD_05 | 27.1 | 36.5 | — | nd | — | Dog_05 | 32.4 | 35.3 | — | nd | — | ||||

| RD_06 | 34.9 | — | — | nd | — | Dog_06 | 33.8 | 33.0 | — | nd | — | ||||

| RD_07 | 28.6 | — | — | — | Dog_07 | 32.0 | 30.4 | 37.0 | — | ||||||

| RD_08 | 26.0 | 30.1 | — | — | Dog_08 | 31.3 | 34.4 | — | — | ||||||

| RD_09 | 28.7 | — | — | Dog_09 | 30.0 | 34.4 | 37.4 | ||||||||

| RD_10 | 30.9 | 32.2 | — | Dog_10 | 27.0 | 30.2 | — | ||||||||

| MG_01 | 29.5 | — | — | nd | nd | nd | — | SK_01 | 36.1 | 35.2 | — | nd | nd | nd | — |

| MG_02 | 30.0 | — | — | nd | nd | nd | — | SK_02 | 30.2 | 32.8 | 36.0 | nd | nd | nd | — |

| MG_03 | — | — | — | nd | nd | — | SK_03 | — | 35.0 | — | nd | nd | — | ||

| MG_04 | 29.3 | — | — | nd | nd | — | SK_04 | — | 36.5 | — | nd | nd | — | ||

| MG_05 | 28.2 | — | 32.8 | nd | — | SK_05 | 30.7 | 34.7 | — | nd | — | ||||

| MG_06 | 21.9 | 33.5 | — | nd | 35.5 | SK_06 | 30.0 | 37.4 | 37.0 | nd | — | ||||

| MG_07 | 20.0 | 30.5 | — | — | SK_07 | 36.7 | — | 36.0 | — | ||||||

| MG_08 | 27.8 | — | — | — | SK_08 | — | — | 35.7 | — | ||||||

| MG_09 | 30.6 | 35.4 | 28.8 | SK_09 | 32.4 | — | — | ||||||||

| MG_10 | 28.1 | — | 36.9 | SK_10 | — | 31.3 | — | ||||||||

All animals received 108.0 FFU/mL by direct oral instillation. −: negative; nd: not determined; blank space: animals already euthanised. Oral swabs, which were positive for RABV RNA in RT-qPCR screenings, were tested for infectious virus by RTCIT. Samples for that infectious vaccine virus could be isolated are marked in bold. Animal abbreviation: RD – raccoon dog, MG – mongoose, RC – raccoon, SK – skunk.

All animals regardless of species produced RABV specific antibodies by day 10 post inoculation

To see whether oral application of the GFP labelled vaccine virus strain SAD B19 elicited a measurable immune response, the presence of rabies specific antibodies was tested by two different diagnostic assays.

All animals were naïve at the time point of vaccine virus application as demonstrated by the absence of rabies specific antibodies as measured both by RFFIT and ELISA. Notably, at day 10 pi all animals had seroconverted as indicated by ELISA (Table 3), and with exception of one skunk, all animals exhibited virus neutralising antibody (VNA) titres above the threshold of 0.5 IU/ml. When reservoir species were grouped according to the presumed responsiveness to ORV a significant difference between more responsive, i.e. foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses, as opposed to the remaining less responsive species could only be observed for VNA titres (Table 3).

Table 3.

RABV specific VNA and binding antibodies in serum samples at day 0 and 10 post inoculation.

| days pi | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | |||||||

| VNA (RFFIT) [IU/mL] |

RABV Ab (ELISA) [% inhibition] |

VNA (RFFIT) [IU/mL] |

RABV Ab (ELISA) [% inhibition] |

|||||

| fox 1 | <0.5 | − | 16.16 | − | 7.65 | + | 76.94 | + |

| fox 2 | 0.33 | − | 38.58 | − | 70.68 | + | 90.94 | + |

| raccoon dog 1 | 0.08 | − | 12.24 | − | 9.66 | + | 59.21 | + |

| raccoon dog 2 | 0.25 | − | 18.42 | − | 0.57 | + | 46.40 | + |

| mongoose 1 | 0.19 | − | 15.28 | − | 45.03 | + | 61.25 | + |

| mongoose 2 | 0.15 | − | 12.61 | − | 23.56 | + | 68.86 | + |

| raccoon 1 | 0.03 | − | 23.54 | − | 2.39 | + | 68.99 | + |

| raccoon 2 | 0.06 | − | 28.77 | − | 1.16 | + | 60.12 | + |

| dog 1 | 0.02 | − | 12.19 | − | 0.55 | + | 42.78 | + |

| dog 2 | 0.25 | − | 13.65 | − | 1.19 | + | 41.08 | + |

| skunk 1 | 0.06 | − | 21.97 | − | 1.38 | + | 75.30 | + |

| skunk 2 | 0.05 | − | 9.96 | − | 0.04 | − | 54.43 | + |

VNA (RFFIT) <0.5 IU/mL/RABV Ab (ELISA) <40% inhibition = no seroconversion (−), VNA (RFFIT) ≥ 0.5 IU/mL/RABV Ab (ELISA) ≥40% inhibition = seroconversion (+).

Discussion

Oral rabies vaccination of wildlife is a challenge as there are a variety of reservoir species that need to be targeted45. By coincidence, the red fox, the initial species for the development of the concept of oral rabies vaccination, was also the species that was highly susceptible to oral rabies vaccination; a relative low minimum effective dose was needed to elicit a protective immune response19–21,46. It was only by experience from experimental and field data that other reservoir species required much higher doses to be successfully immunised by the oral route. Principally, due to the instability of the rabies virus, the gastro-intestinal tract will cause rapid antigen degradation, and hence the rabies virus vaccine must be taken up in the oral cavity for the development of an immune response34. However, from some of these early studies in foxes, it became clear that orally administered inactivated rabies virus vaccines did not induce protective immunity47,48, indicating that vaccine virus replication within the host was essential. Hence, presently all available oral rabies vaccines are live replication-competent virus constructs. Based on our previous findings36, this study aimed at elucidating the species-specific uptake, distribution and kinetics of oral rabies vaccines in the oral cavity of the most important terrestrial rabies reservoir species in order to identify barriers for immunisation with a focus on species known to be rather refractory to oral vaccination. To this end, in this first comparative and comprehensive in vivo tracking study with a standardised approach, we used a genetically modified vaccine virus construct, followed by up-to date techniques in imaging and viral RNA detection. Earlier studies could identify infected cells36,37. In this study, using the SAD L16 GFP construct we were also able to identify cells in which active virus gene expression took place.

Our data confirm that orally administered rabies vaccine virus multiplies at a low level within the oral cavity of foxes, particularly, but not exclusively in the t. palatina, as shown before37. When analysing the time-course of infection in the t. palatina, immunofluorescence analyses of viral nucleoprotein and GFP fluorescence revealed foci of RABV infected cells in the peripheral cell layers of fox tonsils at days 1 to 4 pi (Figs. 1b and 2). These data confirmed previous snapshots of SPBN GASGAS vaccine virus infection of red fox peripheral tonsil layers36 and demonstrate the utility of GFP-labelled vaccine virus strains for in-vivo tracking. Limitation of both vertical and lateral spread of virus infection, strongly indicate a spatio-temporal restriction of vaccine virus tropism and replication in tonsils of foxes.

To follow vaccine virus uptake and subsequent tropism and time course of infection in the t. palatina, next to GFP auto fluorescence, we additionally focused on N protein staining. The observed phenomena of accumulation of N protein aggregates and loss of GFP fluorescence in fox tonsils from day 2 onwards (Figs. 1c and 3b) clearly suggest different kinetics of GFP and N protein accumulation and turnover in vaccine virus infected cells. The N protein as part of intracellular ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) accumulates in large inclusion bodies and is likely to be less prone to degradation, while soluble GFP may be less stable in infected cells and may be rapidly removed by host immune system.

Strikingly, comparative immunofluorescence analyses revealed substantially more vaccine virus and virus infected cells in species that are more responsive to oral vaccination, thus corroborating general assumptions and field observations on differences among reservoir species in vaccine uptake efficiencies8,17,49–52 and responsiveness to oral rabies vaccination18–23. Viral N-protein staining confirmed locally restricted areas of RABV infected cells in the peripheral layer of the t. palatina of foxes, raccoon dogs and mongooses with similar limited vertical and lateral spread of virus infection, but failed to identify even single infected cells in the other species (Fig. 2, Table 1). These observations were corroborated by the differences in the detection of infectious virus and relative viral load in the t. palatina of the respective target species (Figs. 4 and 5). The reasons for these obvious differences remain elusive. As discussed before36, the morphology of the lymphoreticular tissue of the pharynx cannot explain the observed differences in vaccine uptake among the species studied here. All species had a comparable anatomic configuration of Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring with a dominating t. palatina. Also histologically, there was no difference in the cellular structure of the tonsils, which were represented by a peripheral non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelial cell layer followed by germinal centres consisting of lymphocytes (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

In our study we were required to use a very high vaccine dose (108.0 FFU/mL) to increase the likelihood to observe any differences in vaccine uptake in MALT of the oral cavity of the various species at all. This could be the reason why all animals regardless of species exhibited RABV specific antibodies by day 10 pi (Table 3) as measured by the standard RFFIT53 and the more sensitive ELISA53,54, irrespective of the identification of infected cells in the t. palatina. Therefore, other tissues in the oropharyngeal cavity must have been involved in virus uptake and subsequent interaction with the immune system. Screening for viral RNA demonstrated its presence in all investigated tissues, albeit with significant differences in the positivity rates (Fig. 5). The positivity rate for tonsils was higher for species known to be more responsive to oral vaccination as was the relative viral load (Fig. 5) corroborating findings of the immunofluorescence analyses (Figs. 1b and 2). Besides the t. palatina, significantly increased virus detection by RT-qPCR were also seen in mucosa and tongue samples of more responsive species (Fig. 5b), suggesting that infection of other oropharyngeal tissues also contributes to vaccine efficacy. However, based on our data there seems to be no preferential site for vaccine virus uptake and replication in low-responsive species. Our quantitative serological results suggest a correlation with responsiveness to oral vaccination in various species for RFFIT, whereby mean VNA titres of responsive species were significantly higher (p < 0.05) as opposed to low responsive species (Table 3). Even taking this limited number of animals into account this corroborates previous findings53.

The short time window (day 10 pi for virus RNA detection, day 4 pi for antigen detection) during which vaccine virus (SAD L16 GFP) could be detected in tonsils is noteworthy. When dissemination of a conventional C-strain vaccine or a modified live marker vaccine (CP7_E2alf) for classical swine fever in tissues was investigated, vaccine virus genomes were consistently detected in the tonsils lymphoid up to day 7 pi55, day 42 pi56 and day 7757 pi by RT-qPCR. The results indicate that, as with other oral vaccines, vaccine virus detection is usually transient even in lymphatic organs. However, in contrast to the other vaccines, duration time of the rabies vaccine in the tonsils is much shorter and the relative viral load in the t. palatina remains rather low (Figs. 1, 2 and 4)56.

In previous studies, detection of vaccine virus and RNA in oral swabs post vaccination was shown to be residual input virus and not virus shedding as such36. Notably, a clear distinction between responsive and refractory species as seen for vaccine virus tropism and infection in the t. palatina and other tissues in the oropharyngeal cavity was only partially visible when assessing the detection of SAD L16 GFP in oral swabs, partly contrasting earlier findings with the genetically engineered vaccine virus construct SPBN GASGAS36. In our study, vaccine virus could only be re-isolated from oral swabs within 4 hours except for dogs where only RNA was present (Table 2). The detection of vaccine RNA in this time window points to a degradation of input virus by the environment in the oral cavity. Occasional detection of vaccine virus RNA in oral tissues beyond day 1 pi (see Supplementary Tables S4–S9) may be due to release of non-infectious virus particles from infected cells or the detection of dislodged cells containing vaccine virus RNA.

Taken together, the data corroborate the hypothesis of rapid clearance of attenuated rabies virus vaccines in the oral cavity as described before regardless of the target species37,58. The mechanism behind this could be related to the activation of NFκB related genes, which might lead to a rapid clearance at the primary sites of infection as shown for SPBN GASGAS59. Still quite unknown is whether RABV infection of related immune cells, which could trigger a strong antigen specific response, influences the development of a protective immunity. In vitro and in vivo studies revealed that rabies virus could directly infect immune cells. RABV infection of human and mouse T lymphocytes induced apoptosis, which subsequently lead to an enhanced immune response by activating macrophages, cytokine cascades and increased antigen presentation60. Also, RABV was shown to infect and activate primary B cells, which subsequently directly primed and activated CD4+ T cells in vitro61. To investigate whether B and T cell infection occur in vivo, further functional characterisation of target cells, such as lymphocytes in the epithelial cell layers of infected tonsils, is required.

Conclusions

The comparison of the in vivo tropism and time course of infection of an attenuated oral rabies vaccine virus in the oropharyngeal tract of the most important rabies reservoir species43 after direct oral instillation clearly revealed species-specific differences. Although the detailed mechanisms of vaccine virus uptake and processing as well as the involvement of potentially infected immune cells in the t. palatina need further clarification, the results strengthen the hypothesis that certain reservoir species appear more refractory to oral vaccination than others. Whether field effectiveness of ORV for example in skunks and raccoons appears to be limited by poor bait uptake or inadequate ingestion of vaccine rather than from poor vaccine efficacy62 remains to be proven.

Next to the t. palatina as a main site of vaccine virus uptake, other tissues in the oropharyngeal cavity may play a greater role in virus uptake and subsequent interaction with the immune system than assumed before. Understanding the mechanisms of vaccine virus uptake and replication is crucial for vaccine development and optimisation. Next to improved or new vaccines that lead to enhanced field performance17, further research should investigate how vaccine uptake efficacy in raccoons, skunks and other rather refractory reservoir species can be improved, for example by increasing vaccine titre, vaccination intervals or by adding muco-adhesive and/or permeation enhancing substances63–66 to allow for future elimination strategies.

Material and Methods

Virus

The laboratory strain SAD L16 is a recombinant full-length clone of the attenuated oral vaccine strain SAD B1967,68. A GFP expressing variant was generated by a standard rescue protocol69 after insertion of an additional transcription unit between virus genes G and L at SAD L16 genome position 5338. The inserted sequence comprised a duplicated N/P gene border sequences (SAD L16 nt positions 1413–1500) followed by an ORF coding for an EGFP protein with N- and C-terminal Strep- and His-tags, respectively.

Ethics statement

All animals were kept in accordance with the prevailing guidelines and general care was provided as required. While the pilot fox study (42502-3-725) and the study in dogs (42502-3-762) was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal State of Saxony Anhalt, Landesverwaltungsamt Sachsen-Anhalt, 06003 Halle, Germany, all other studies were evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Landesamt für Landwirtschaft, Lebensmittelsicherheit und Fischerei Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 18003 Rostock, Germany (7221.3-1-058/15).

Animals

10 animals per species (foxes, raccoon dogs, mongooses, raccoons, dogs and striped skunks) were used for oral inoculation and dissemination studies.

Adult foxes, raccoon dogs, raccoons, skunks and dogs (breed: beagles HsdRcc: DOBE, 4–5 kg) were purchased from commercial breeders, whereas mongoose were caught using baited box traps on the rabies-free island Korčula, Croatia, and transported to Germany. Except for dogs and foxes of the pilot study, all animals were kept in individual stainless steel cages at 20 °C room temperature, 60–80% humidity and a 12 hr/12 hr (35% dimming during night modus) lighting control within a fan forced draught ventilation equipped BSL3** animal facility at the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute (FLI), Greifswald – Insel Riems, Germany. Dogs and foxes of the pilot study were kept in single cages at a room temperature of 20–25 °C, 20–70% humidity and a 12 hr/12 hr light-dark control within the animal facility at the Ceva Innovation Center GmbH (Dessau-Roßlau, Germany). Animals were fed daily with commercially produced feed for farmed-kept foxes and raccoon dogs (Schirmer und Partner GmbH Co KG, Döhlen, Germany; Michael Hassel GmbH, Langenargen, Germany). The diet was supplemented with vitamins, minerals and items like 1-day old chicken. Water was offered ad libitum. The general health status of all animals, feed uptake and defecation was observed and recorded daily.

Blood samples were taken prior to immunisation and at day of necropsy (see Supplementary Fig. S1). For animals at the FLI (foxes of the comparative study, raccoon dogs, mongooses, raccoons and skunks), collection of blood samples and administration of virus were conducted under anaesthesia using Zoletil® (combination of Tiletamin and Zolazepam, Virbac, France). Blood was taken from the large superficial veins of the extremities (e.g. Vena cephalica antebrachii, Vena saphena). For euthanasia, animals were first anaesthetised with Zoletil® followed by cardiac bleeding and subsequent administration of T61® (Intervet, Germany). Foxes of the pilot study were anaesthetised with a combination of Xylazine and Ketamine whereas for dogs no anaesthesia for blood sampling and virus administration was needed. For euthanasia, foxes and dogs were first anaesthetised using a combination of Xylazine and Ketamine (foxes) and Medetomidine, Acepromazine and Butorphanol (dogs) followed by cardiac bleeding and subsequent administration of T61®.

Oral inoculation and dissemination studies

To investigate species-specific differences in vaccine virus tropism, all animals received 1.0 mL SAD L16 GFP (108 FFU/mL) by direct oral application (d.o.A.). This rather high dose was selected because it increased the likelihood of successful immunization in all species based on experience with SAD B19 or SAD B19-derived oral rabies virus vaccines19,20,23,28,32.

To prove the suitability and functionality of the Green-Fluorescence-Protein (GFP) expressing model vaccine virus and to follow the time course of vaccine virus infection in the t. palatina after oral application in a highly responsive species, in a pilot study (Fig. 1), two foxes were sacrificed 2, 3, 4 and 10 days and one animal 1 day post inoculation (pi). At necropsy, samples of the t. palatina, lymph node tissues, mucosa, and tongue were collected for immunofluorescence analysis.

In the subsequent comparative study (Fig. 2) aimed at elucidating differences in vaccine uptake efficiency, two animals of each species were sacrificed 1, 2, 3, 4 and 10 days pi, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S1). At necropsy, the skulls were carefully dissected in two halves with a diamond band saw to expose Waldeyer’s ring and tongue. Subsequently, the following tissues were carefully prepared and samples of the lymph nodes (lymphonodii (lnn.) mandibulares, lnn. parotidei, lnn. retropharyngei), mucosa, tongue and parts of the Waldeyer´s ring (lingual ground, t. palatina, t. pharyngea, soft palate) were collected and screened for vaccine virus construct by RT-qPCR. One half of each skull with the Waldeyer’s ring attached was immediately fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde for at least 14 days. Similar tissue samples as aforementioned were processed, embedded in paraffin wax and 2–4 µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Specimens were histologically assessed for the presence of lesions, and the occurrence of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following standard criteria: variable interfollicular T-cell zones, multiple B-cell follicles, lack of afferent lymphatics, direct exogenous antigen sampling by mucosal surfaces with microfold/membrane (M) cells35 using an Axio Imager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). For immunofluorescence analysis, tissues were fixed in 4% buffered formaldehyde (pH 7.4). Saliva swabs were taken prior to (0 h) and 2 h, 4 h and 24 h after oral RABV administration as well as during necropsy (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Saliva samples were collected by wiping off the oral cavity for at least 1 minute. The cotton tips were stored at −80 °C until subsequent analysis of virus construct by RT-qPCR and rabies tissue culture infection test (RTCIT).

Diagnostic assays

For detection of RABV RNA in oropharyngeal tissue samples and saliva swabs, RNA was extracted fully automated using the MagAttract Viral RNA M18 Kit in combination with the BioSprint 96 Workstation (Quiagen, Hilden) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was done as previously described70. Positive tested saliva and t. palatina samples were further analysed for presence of infectious rabies virus by RTCIT71,72 using the cell line BHK-21 [BSR/5] (Collection of Cell Lines in Veterinary Medicine (CCLV), Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, No. 0194). To confirm a negative result, three sequential cell culture passages were carried out.

For the detection of virus neutralising antibodies (VNA), collected blood samples were analysed by rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT) as described elsewhere53. Binding antibodies were detected by rabies virus specific inhibition ELISA according to manufacturer specifications (BioPro Rabies ELISA Ab kit, O.K. Servis BioPro, Prague, Czech Republic)54.

Immunofluorescence analysis

For subsequent immunofluorescence analysis, vibratome sections of fixed tonsils with a thickness of 150 µm were prepared. Because of the small size, cryostat sections of mongoose t. palatina with a thickness of 20 µm were prepared and mounted on a slide. Tonsil sections were incubated overnight with a specific primary antibody against RABV nucleoprotein (polyclonal rabbit-α-RABV N 161-573, diluted 1:3000 in 0.1% Triton/PBS), followed by an incubation with the fluorophore-coupled secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor® 568 goat-α-rabbit, 0.7 µg/mL in 0.1% Triton/PBS, ThermoFisher Scientific) for 4 h. Nuclei were visualised with Hoechst 33342 (1 µg/mL in PBS, ThermoFisher Scientific). Stained t. palatina slices were documented using the confocal laser-scan microscope Leica DMI 6000 TCS SP5 with a 63-fold oil immersion objective (Leica Microsystems).

Immunohistochemistry

To characterize the cellular morphology of t. palatina in each species, immunohistochemistry was applied using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase-complex (ABC) method utilizing the Vectastain® Elite ABC standard kit (Vector Laboratories) with citric buffer (10 mM, pH 6,0) pre-treatment, to label the following tonsillar epitopes: cytokeratins 1–8, 10, 13–17, 19 (clone AE1/AE3, mouse anti-human, monoclonal, diluted 1:500, Dako, Deutschland GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), macrophages and dendritic cells (anti IBA1, rabbit anti-human, polyclonal, diluted 1:200, FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals, Germany), B cells (CD20, rabbit anti-human, polyclonal, diluted 1:200, Thermo Fisher, Germany), T cells (CD3, rabbit anti-human, polyclonal, diluted 1:200, Dako, Germany,) and RABV-nucleoprotein (polyclonal, rabbit-α-N161-5; diluted 1: 200073) by incubating overnight. Antigen visualization was performed with 3-amino-9-ethyl-carbazol as chromogen and hematoxylin as counterstain. As negative controls, consecutive sections were incubated with rabbit serum or tris-buffered saline instead of the primary antibodies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance in the differences between two means (RT-qPCR positivity) between various lymphoid tissues in responsive versus low-responsive species was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Šidák´s multiple comparison test. Other data including the overall RT-qPCR positivity, the ct-values in t. palatina, and serological results were tested for significance using an unpaired T-test. Analyses were carried out using Graphpad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with P values < 0.05 considered statistically significant and P values < 0.01 considered highly significant, respectively.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Thomas Möritz, Matthias Jahn, and Frank Klipp and the entire team for supervising the keeping of the animals. We are also grateful to Jeannette Kliemt, Angela Hillner, Dietlind Kretzschmar and Gabriele Czerwinski for their skilled technical assistance with laboratory diagnostics. The project was funded in the frame of a research cooperation with Ceva Innovation Center GmbH into mechanisms of oral rabies vaccination and supported by an intramural collaborative research grant at the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut.

Author contributions

V.t.K. was the principle investigator for the experimental study, while S.F. and P.S. functioned as project manager and coordinator for all other partners involved. V.t.K., C.M.F., A.V., S.F. and T.M. designed the experimental study. P.S. and C.K. provided the experimental facilities for foxes (pilot study) and dogs at Ceva Innovation Center GmbH. S.O., A.K., V.t.K., S.N., E.E. and T.N. were daily supervisors of the experiment and were in charge of sample collection and preparation at Ceva Innovation Center GmbH and FLI. S.F. provided the oral vaccine virus construct (SAD L16 GFP). R.U. and J.S. conducted macroscopic and pathohistologic examinations. V.t.K., S.N., E.E., T.N., S.O., T.M., C.M.F., R.U. and J.S. were in charge of subsequent immunohistological and immunofluorescence investigations. V.t.K., E.E., T.M. and C.M.F. did diagnostic testing of tissues and serum samples. V.t.K., T.M., C.M.F., S.F. and A.V. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures and tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information Files).

Competing interests

Drs A.V., P.S., C.K., A.K. and S.O. are full-time employees of Ceva Innovation Center GmbH, Germany, a company manufacturing oral rabies vaccine baits. Drs T.M., C.M.F., S.F. and V.t.K. from the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute received funding from Ceva Innovation Center GmbH in the frame of a joint research cooperation on mechanisms of oral rabies vaccination of animals and resulting immunity but declare no other potential conflict of interest. Drs T.N., E.E., R.U. and J.S. declare no potential conflict of interest. Ceva Innovation Center GmbH, Germany, was involved in the conceptualisation, design, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. The corresponding author declares no competing interest within the submission system.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-59719-4.

References

- 1.Thulke, H. & Eisinger, D. The strength of 70%: revision of a standard threshold of rabies control. In Towards the elimination of rabies in Eurasia Development in Biologicals (eds B. Dodet, A. R. Fooks, T. Müller, & N. Tordo) 291–298 (Karger, 2008). [PubMed]

- 2.Aubert, M. In Wildlife Rabies Control (eds K. Bögel, F. X. Meslin, & M. Kaplan) 9–18 (Wells Medical Ltd., 1992).

- 3.Müller T, et al. Terrestrial rabies control in the European Union: historical achievements and challenges ahead. Vet. J. 2015;203:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma X, et al. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2016. J. Am. Veterinary Med. Assoc. 2018;252:945–957. doi: 10.2460/javma.252.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everard COR, Everard JD. Mongoose Rabies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1988;10:610–614. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.Supplement_4.S610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampson K, et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cliquet F, et al. Oral vaccination of dogs: a well-studied and undervalued tool for achieving human and dog rabies elimination. Vet. Res. 2018;49:61. doi: 10.1186/s13567-018-0554-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidwa TJ, et al. Evaluation of oral rabies vaccination programs for control of rabies epizootics in coyotes and gray foxes: 1995–2003. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2005;227:785–792. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacInnes CD, et al. Elimination of rabies from red foxes in eastern Ontario. J. Wildl. Dis. 2001;37:119–132. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-37.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velasco-Villa, A. et al. The history of rabies in the Western Hemisphere. Antiviral Res., 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.013 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Freuling CM, et al. The elimination of fox rabies from Europe: determinants of success and lessons for the future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2013;368:20120142. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki J, et al. Oral vaccination of wildlife using a vaccinia-rabies-glycoprotein recombinant virus vaccine (RABORAL V-RG((R))): a global review. Vet. Res. 2017;48:57. doi: 10.1186/s13567-017-0459-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tolson ND, Charlton KM, Lawson KF, Campbell JB, Stewart RB. Studies of Era/Bhk-21 Rabies Vaccine in Skunks and Mice. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1988;52:58–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rupprecht CE, Dietzschold B, Cox JH, Schneider LG. Oral vaccination of raccoons (Procyon lotor) with an attenuated (SAD-B19) rabies virus vaccine. J. Wildl. Dis. 1989;25:548–554. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-25.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rupprecht CE, et al. Oral immunization and protection of raccoons (Procyon lotor) with a vaccinia-rabies glycoprotein recombinant virus vaccine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA Biol. Sci. 1986;83:7947–7950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.20.7947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolson ND, et al. Mutants of rabies viruses in skunks: immune response and pathogenicity. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1990;54:178–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slate D, et al. Oral rabies vaccination in north america: opportunities, complexities, and challenges. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cliquet F, et al. Safety and efficacy of the oral rabies vaccine SAG2 in raccoon dogs. Vaccine. 2006;24:4386–4392. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neubert A, Schuster P, Müller T, Vos A, Pommerening E. Immunogenicity and efficacy of the oral rabies vaccine SAD B19 in foxes. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Public. Health. 2001;48:179–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2001.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuster P, et al. Comparative immunogenicity and efficacy studies with oral rabies virus vaccine SAD P5/88 in raccoon dogs and red foxes. Acta Vet. Hung. 2001;49:285–290. doi: 10.1556/004.49.2001.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cliquet F, et al. Efficacy of a square presentation of V-RG vaccine baits in red fox, domestic dog and raccoon dog. Dev. Biol. 2008;131:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanton JD, et al. Vaccination of Small Asian Mongoose (Herpestes javanicus) Against Rabies. J. Wildl. Dis. 2006;42:663–666. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-42.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vos A, et al. Oral vaccination of captive small Indian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) against rabies. J. Wildl. Dis. 2013;49:1033–1036. doi: 10.7589/2013-02-035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown LJ, et al. Oral vaccination and protection of striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis) against rabies using ONRAB(R) Vaccine. 2014;32:3675–3679. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlton KM, et al. Oral rabies vaccination of skunks and foxes with a recombinant human adenovirus vaccine. Arch. Virol. 1992;123:169–179. doi: 10.1007/BF01317147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grosenbaugh DA, Maki JL, Rupprecht CR, Wall DK. Rabies Challenge of Captive Striped Skunks (Mephitis mephitis) following Oral Administration of a Live Vaccinia-Vectored Rabies Vaccine. J. Wildl. Dis. 2007;43:124–128. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rupprecht CE, et al. Ineffectiveness and Comparative Pathogenicity of Attenuated Rabies Virus-Vaccines for the Striped Skunk (Mephitis-Mephitis) J. Wildl. Dis. 1990;26:99–102. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-26.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vos A, Pommerening E, Neubert L, Kachel S, Neubert A. Safety studies of the oral rabies vaccine SAD B19 in striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) J. Wildl. Dis. 2002;38:428–431. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.2.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fekadu M, et al. Immunogenicity, efficacy and safety of an oral rabies vaccine (SAG-2) in dogs. Vaccine. 1996;14:465–468. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)00244-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cliquet, F. et al. The safety and efficacy of the oral rabies vaccine SAG2 in Indian stray dogs. Vaccine, 257–264 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.WHO. Oral immunization of dogs against rabies: report of the Sixth Consultation. (WHO, 1998).

- 32.Aylan O, Vos A. Efficacy studies with SAD B19 in Turkish dogs. J. ETLIK Veterinary Microbiology. 1998;9:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rupprecht CE, et al. Oral vaccination of dogs with recombinant rabies virus vaccines. Virus Res. 2005;111:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baer GM, Broderson JR, Yager PA. Determination of the site of oral rabies vaccination. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1975;101:160–164. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandtzaeg P, Kiyono H, Pabst R, Russell MW. Terminology: nomenclature of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:31–37. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vos A, et al. Oral vaccination of wildlife against rabies: Differences among host species in vaccine uptake efficiency. Vaccine. 2017;35:3938–3944. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orciari LA, et al. Rapid clearance of SAG-2 rabies virus from dogs after oral vaccination. Vaccine. 2001;19:4511–4518. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ortmann S, et al. In Vivo Safety Studies With SPBN GASGAS in the Frame of Oral Vaccination of Foxes and Raccoon Dogs Against Rabies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018;5:91. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortmann S, et al. Safety studies with the oral rabies virus vaccine strain SPBN GASGAS in the small Indian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) BMC Vet. Res. 2018;14:90. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanlon CA, Niezgoda M, Morrill P, Rupprecht CE. Oral efficacy of an attenuated rabies virus vaccine in skunks and raccoons. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002;38:420–427. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fekadu M, et al. Oral vaccination of skunks with raccoon poxvirus recombinants expressing the rabies glycoprotein or the nucleoprotein. J. Wildl. Dis. 1991;27:681–684. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-27.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tolson ND, Charlton KM, Stewart RB, Campbell JB, Wiktor TJ. Immune Response in Skunks to a Vaccinia Virus Recombinant Expressing the Rabies Virus Glycoprotein. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1987;51:363–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization WHO expert consultation on rabies, third report. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2018;1012:195. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casteleyn C, Breugelmans S, Simoens P, Van den Broeck W. The tonsils revisited: review of the anatomical localization and histological characteristics of the tonsils of domestic and laboratory animals. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011;2011:472460. doi: 10.1155/2011/472460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA, Slate D. Oral vaccination of wildlife against rabies: opportunities and challenges in prevention and control. Dev. Biol. 2004;119:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baer GM, Abelseth MK, Debbie JG. Oral vaccination of foxes against rabies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1971;93:487–490. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brochier B, Godfroid J, Costy F, Blancou J, Pastoret PP. Vaccination of young foxes (Vulpes vulpes, L.) against rabies: trials with inactivated vaccine administered by oral and parenteral routes. Ann. Rech. Vet. 1985;16:327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rupprecht CE, Dietzschold B, Campbell JB, Charlton KM, Koprowski H. Consideration of inactivated rabies vaccines as oral immunogens of wild carnivores. J. Wildl. Dis. 1992;28:629–635. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-28.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vos A, Müller T, Schuster P, Schlüter H, Neubert A. Oral vaccination of foxes against rabies with SAD B19 in Europe, 1983 - 1998: A review. Veterinary Bull. 2000;70:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zienius, D., Pridotkas, G., Lelesius, R. & Sereika, V. Raccoon dog rabies surveillance and post-vaccination monitoring in Lithuania 2006 to 2010. Acta Vet. Scand. 53, 10.1186/1751-0147-53-58 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Niin E, Laine M, Guiot AL, Demerson JM, Cliquet F. Rabies in Estonia: Situation before and after the first campaigns of oral vaccination of wildlife with SAG2 vaccine bait. Vaccine. 2008;26:3556–3565. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosatte R, et al. Prevalence of tetracycline and rabies virus antibody in raccoons, skunks, and foxes following aerial distribution of V-RG baits to control raccoon rabies in Ontario, Canada. J. Wildl. Dis. 2008;44:946–964. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-44.4.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore, S. et al. Rabies Virus Antibodies from Oral Vaccination as a Correlate of Protection against Lethal Infection in Wildlife. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2, 10.3390/tropicalmed2030031 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Wasniewski M, et al. Evaluation of an ELISA to detect rabies antibodies in orally vaccinated foxes and raccoon dogs sampled in the field. J. Virol. Methods. 2013;187:264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drager C, Petrov A, Beer M, Teifke JP, Blome S. Classical swine fever virus marker vaccine strain CP7_E2alf: Shedding and dissemination studies in boars. Vaccine. 2015;33:3100–3103. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koenig P, et al. Detection of classical swine fever vaccine virus in blood and tissue samples of pigs vaccinated either with a conventional C-strain vaccine or a modified live marker vaccine. Vet. Microbiol. 2007;120:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tignon M, et al. Classical swine fever: comparison of oronasal immunisation with CP7E2alf marker and C-strain vaccines in domestic pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;142:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vos A, et al. An assessment of shedding with the oral rabies virus vaccine strain SPBN GASGAS in target and non-target species. Vaccine. 2018;36:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J, McGettigan JP, Faber M, Schnell MJ, Dietzschold B. Infection of monocytes or immature dendritic cells (DCs) with an attenuated rabies virus results in DC maturation and a strong activation of the NFkappaB signaling pathway. Vaccine. 2008;26:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thoulouze MI, Lafage M, Montano-Hirose JA, Lafon M. Rabies virus infects mouse and human lymphocytes and induces apoptosis. J. Virol. 1997;71:7372–7380. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.10.7372-7380.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lytle AG, Norton JE, Jr., Dorfmeier CL, Shen S, McGettigan JP. B cell infection and activation by rabies virus-based vaccines. J. Virol. 2013;87:9097–9110. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00800-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wohlers A, Lankau EW, Oertli EH, Maki J. Challenges to controlling rabies in skunk populations using oral rabies vaccination: A review. Zoonoses Public. Health. 2018;65:373–385. doi: 10.1111/zph.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fry T, Van Dalen K, Hurley J, Nash P. Mucosal adjuvants to improve wildlife rabies vaccination. J. Wildl. Dis. 2012;48:1042–1046. doi: 10.7589/2011-11-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borsutzky S, et al. The mucosal adjuvant macrophage-activating lipopeptide-2 directly stimulates B lymphocytes via the TLR2 without the need of accessory cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6308–6313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benediktsdottir BE, Baldursson O, Masson M. Challenges in evaluation of chitosan and trimethylated chitosan (TMC) as mucosal permeation enhancers: From synthesis to in vitro application. J. controlled release: Off. J. Controlled Rel. Soc. 2014;173:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma S, Kulkarni J, Pawar AP. Permeation enhancers in the transmucosal delivery of macromolecules. Pharmazie. 2006;61:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conzelmann KH, Cox JH, Schneider LG, Thiel HJ. Molecular Cloning and Complete Nucleotide Sequence of the Attenuated Rabies Virus SAD B19. Virology. 1990;175:485–499. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90433-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schnell MJ, Mebatsion T, Conzelmann KK. Infectious Rabies Viruses from Cloned Cdna. EMBO J. 1994;13:4195–4203. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finke S, Granzow H, Hurst J, Pollin R, Mettenleiter TC. Intergenotypic replacement of lyssavirus matrix proteins demonstrates the role of lyssavirus M proteins in intracellular virus accumulation. J. Virol. 2010;84:1816–1827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01665-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffmann B, et al. Improved safety for molecular diagnosis of classical rabies viruses by use of a TaqMan real-time reverse transcription-PCR “double check” strategy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:3970–3978. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00612-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Webster WA. A tissue culture infection test in routine rabies diagnosis. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1987;51:367–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Webster, W. A. & Casey, G. A. Virus isolation in neuroblastoma cell culture. In Laboratory techniques in rabies, 4th ed.; Meslin, F. X., Kaplan, M. M. & Koprowski, H., Eds. World Health Organization: Geneva, pp. 93–104 (1996).

- 73.Orbanz J, Finke S. Generation of recombinant European bat lyssavirus type 1 and inter-genotypic compatibility of lyssavirus genotype 1 and 5 antigenome promoters. Arch. Virol. 2010;155:1631–1641. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0743-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information Files).