Abstract

Despite an overall temporal stability in time of the human gut microbiota at the phylum level, strong variations in species abundance have been observed. We are far from a clear understanding of what promotes or disrupts the stability of microbiome communities. Environmental factors, like food or antibiotic use, modify the gut microbiota composition, but their overall impacts remain relatively low. Phages, the viruses that infect bacteria, might constitute important factors explaining temporal variations in species abundance. Gut bacteria harbour numerous prophages, or dormant viruses, which can evolve to become ultravirulent phage mutants, potentially leading to important bacterial death. Whether such phenomenon occurs in the mammal’s microbiota has been largely unexplored. Here we studied temperate phage–bacteria coevolution in gnotoxenic mice colonised with Roseburia intestinalis, a dominant symbiont of the human gut microbiota, and Escherichia coli, a sub-dominant member of the same microbiota. We show that R. intestinalis L1-82 harbours two active prophages, Jekyll and Shimadzu. We observed the systematic evolution in mice of ultravirulent Shimadzu phage mutants, which led to a collapse of R. intestinalis population. In a second step, phage infection drove the fast counter-evolution of host phage resistance mainly through phage-derived spacer acquisition in a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats array. Alternatively, phage resistance was conferred by a prophage originating from an ultravirulent phage with a restored ability to lysogenize. Our results demonstrate that prophages are a potential source of ultravirulent phages that can successfully infect most of the susceptible bacteria. This suggests that prophages can play important roles in the short-term temporal variations observed in the composition of the gut microbiota.

Subject terms: Bacteriophages, Molecular evolution

Introduction

The mammal’s gut microbiota is probably one of the most densely populated microbial communities on earth. In humans, its composition is globally conserved among healthy adults [1, 2], and abnormal compositions, called dysbioses, are correlated with numerous diseases [3–5]. Yet the factors influencing the composition of the gut microbiota in health and disease are far from being entirely understood. For example, in a study on ~1000 healthy adults, the combined effect of 69 covariates (food, drug, anthropometric factors, etc.) could explain only 16.4% of the variation in microbiota composition [6]. The impact of host genetics seems to be even lower [7]. In addition, despite overall stability in term of presence or absence of main bacterial genera, strong variations in the relative abundance of species are observed on short time scale, even in healthy individuals submitted to the same diet [8–11]. Bacteriophages (phages), the viruses that infect bacteria, have been suspected to impact intestinal microbiota composition. In spite of clear evidence that phage-mediated selection plays an important role in bacterial strain diversification (reviewed in [12]), there is as yet little proof that they are important determinants of the microbiota composition (reviewed in [13–16]). Some metagenomics studies showed correlations between an increase in specific phages with reductions of particular bacterial taxa [17, 18]. Yet, in most animal experiments using well-defined phage–bacteria pairs, phage-mediated bacterial mortality in the gut environment was limited to a fraction of susceptible bacteria, and was not sufficient to drive the selection of phage-resistant bacteria [19–21], suggesting that the intestinal environment complicates phage multiplication [16, 22]. In agreement with these observations, the phage to bacteria ratio is much lower in the gastrointestinal tract than in other environments, suggesting less lytic replication [23]. These different pieces of evidence might contribute to the fact that the study of phages in the gut microbiota lagged behind the study of bacteria, and that phages are still often forgotten in microbiome studies.

Temperate phages, in particular, are generally considered to cause low bacterial mortality. They encode molecular mechanisms enabling them either to reproduce through lytic cycles upon infection or to lysogenize bacteria, i.e., to establish in a stable dormant state in the infected cell. The dormant phage is called a prophage, the bacterial host a lysogen, and it is estimated that about 80% of bacteria are lysogens in the mammal’s gut [24–26]. In line with this estimation, virions from temperate phages are dominant among intestinal viruses [23, 27, 28]. Prophages are generally considered beneficial for their bacterial hosts, in particular in the gastrointestinal tract [15, 29]. The first advantage of lysogeny is superinfection inhibition, i.e., the protection from infection by other phages of the same “immunity” type. Inhibition of the superinfecting phage occurs by the same mechanism that establishes the dormancy of the resident prophage [30]. Second, prophages can bring new functions to their host, favouring colonisation, growth or stress resistance (reviewed in [31]). Finally, lysogeny can provide an advantage to the bacterial host by releasing infectious virions that are able to kill susceptible bacterial competitors [32, 33]. Yet, in the gut, this advantage is limited by the frequent lysogenization of susceptible bacteria [34, 35], as well as by the supposed rarity of susceptible competitors. Therefore, to date, the role of temperate phages in intestinal microbial communities is mostly studied from the perspective of horizontal gene transfer.

Yet some prophages can constitute a major threat for their hosts. In several microbial environments, important induction of prophages has been observed, resulting in the death of a significant part of the bacterial population [35–37]. In addition, prophages of strains used in large-scale industrial fermentations are potential sources of virulent phage mutants infective for the host strain, the so-called ultravirulent mutants [38–40]. However, to the best of our knowledge, even though lysogeny is widespread among intestinal bacteria, massive killing of bacteria by a temperate phage has never been documented in intestinal environments. This might result from a potential limited ability of phages to multiply in the gut environment as previously discussed, but also from a surprisingly paucity of studies of temperate phage–bacteria coevolution in such an important microbial ecosystem [12].

The complexity of the gut microbiota prevents any exhaustive characterisation of all the virus–bacteria interactions, even with high throughput metagenomic studies. A particular roadblock is the difficulty to predict the bacterial host of the phages detected, especially for phages with no relatives among reference viruses (reviewed in [41]). In particular, no phage infecting Lachnospiracea, the most abundant bacterial family of the human gut microbiota [6], has been deposited in public databases. Here we followed the coevolution in gnotoxenic mice of a Lachnospiracea strain, Roseburia intestinalis L1-82, and its prophages. The Roseburia genus is of particular interest, not only because of its high abundance in the gut microbiota, but also because of its important production of short-chain fatty acids in the human gut, including butyrate, which have a critical role in the regulation of host immune responses [42], and is depleted in several human diseases [43]. In our study, mice were co-colonised with Escherichia coli, a sub-dominant member of the human gut microbiota whose abundance increases in several human diseases [44]. We show that ultravirulent mutants of R. intestinalis phage Shimadzu systematically invade this simplified gut ecosystem, and lyse the large majority of susceptible bacteria. Phage-mediated bacterial killing drives the fast evolution of host phage resistance through phage-derived spacer acquisition in a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) array. Our results illustrate that prophages are not always dormant, and can play important roles in the short-term temporal variations observed in the composition of the microbiota.

Material and methods

Bacterial cultures

R. intestinalis L1-82 (DSM 14610), was grown at 37 °C in LYBHI medium (BHI medium (Merck) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco), cellobiose at 0.5 mg/ml (Sigma), maltose at 0.5 mg/ml (Sigma) and cysteine at 0.5 mg/ml (Sigma)), in an anaerobic chamber filled with 90% N2, 5% CO2and 5% H2. E. coli LF82 (obtained from M2iSH lab, Université Clermont Auvergne, France) and E. coli MG1655 were grown in LB medium (Difco) at 37 °C or LB agar plates (1.5% agar). R. intestinalis was plated on LYBHI agar plates (LYBHI medium with 1.5% agar and hemin at 0.5%), supplemented with 2 µg/mL of ciprofloxacine to suppress E. coli growth when necessary.

Sequencing of encapsidated DNA in L1-82 culture supernatant

A total of 500 ml of an L1-82 culture grown overnight were centrifuged at 5200 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was recovered and centrifuged at 5200 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. This step was repeated with 1 h of centrifugation and the samples were concentrated with PEG and NaCl as described below. Phage pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of SM buffer (100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 (Sigma)) and treated with 0.25 μg of RNAse A (Sigma) and Dnase I (Sigma) at 37 °C for 1 h. Phage DNA was then extracted using Promega kit Wizard® DNA Clean-up system. Sequencing was performed with the Ion proton sequencing technology. Alignment of reads was performed using bowtie2 (-N 1 –L 32) and then visualised with Tablet using default parameters [45]. Overall, 60% and 19.4% of total reads respectively aligned to the two predicted prophages, the last 20% of reads aligning to the rest of the L1-82 genome, indicating a background level of chromosomal DNA contamination. As the whole bacterial genome is about 100-fold longer than both prophages, this contamination accounts for about 0.2% of reads aligning on each prophage, and is thus negligible in the estimation of the number of encapsidated phage genomes.

Mitomycin C induction

Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold and grown at 37 °C until absorbance at 600 nm was between 0.2 and 0.4. 135 µL of culture was distributed in a 96-well plate (Cellstar, 96 Well Cell Culture Plate, U-bottom) and 15 µL of H2O or Mitomycin C (Sigma) was added at the appropriate dilution. Plate was sealed (AMPLIsealTM Greiner Bio-one) in anaerobic condition and incubated at 37 °C in a TECAN SUNRISE. Absorbance at 600 nm was measured every 15 min for 10 h. Phage genome counts in supernatant were determined after 6 h by quantitative PCR as described below.

Animals and experimental design

Germ-free 5–8 week-old C3H/HeN mice (female) from the germ-free rodent breeding facilities of Anaxem-Micalis (INRA, Jouy-en-Josas, France) were kept in flexible-film isolators (Getinge-La Calhène, Vendôme, France) in standard cages (2–4 mice/cage) with sterile wood shavings as animal bedding. Three entirely independent experiments were performed, each with two or three cages. Cage 7, for which results are not detailed here, was placed in the same incubator as cages 3 and 4, and the levels of R. intestinalis and Shimadzu followed a similar pattern to the other cages. Mice were given free access to autoclaved tap water and to a standard diet, R03-40 (Scientific Animal food and Engineering, Augy, France), sterilised by gamma irradiation. Isolators were maintained under controlled conditions of light (12 h), temperature (20–22 °C) and humidity (45–55%). To obtain gnotobiotic E. coli/R. intestinalis-diassociated mice, mice were orally inoculated with 100 µL of a saturated E. coli LF82 or E. coli MG1655 culture (2.5 × 109 CFU/ml). After 48 h, 1010 CFU of R. intestinalis in 200 µL were administered by intragastric gavage of mice pretreated with sodium bicarbonate (0.2 M, 0.1 mL by intragastric gavage, 10 min ahead of the inoculation of bacteria). All procedures were carried out according to European Community Rules of Animal Care and with authorisation 1234-2015101315238694 from French Veterinary Services.

Phage extraction and isolation from faeces

Fresh or frozen faeces thawed on ice for 10 min were diluted 40-fold in cold PBS. Resuspended faeces were kept on ice for 5 min with regular agitation prior to centrifugation for 10 min at 5251 × g at 4 °C. Supernatants were recovered and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter (PALL Corporation Acrodisc PF syringe filter). For subsequent quantification by PCR, virions were precipitated with PEG 8000 (Sigma) at a final concentration of 10% and NaCl (Sigma) at a final concentration of 1 M. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, phage particles were harvested by centrifugation (5251 × g for 1 h at 4 °C with a swinging rotor) and resuspended in 100 μl of SM buffer. Samples were treated with 10 U of Turbo DNase (Ambion) for 1 h at 37 °C in Turbo DNase buffer and then incubated at 95 °C for 30 min in 0.2 ml PCR tubes for enzyme inactivation and capsid disruption. For phage isolation, the faecal filtrates were mixed with 150 µL of an exponentially growing R. intestinalis culture (optical density at 600 nm comprised between 0.2 and 0.5) in an anaerobic chamber. Overall, 1 ml of melted Top BHI agarose (LYBHI supplemented with 0.25% agarose and 0.1% cysteine (Sigma)) at 37 °C was added and the mix was immediately poured on 6 cm diameter Petri dishes containing LYBHI agar. Plates were then incubated overnight at 37 °C in the anaerobic chamber. A single lysis plaque was then mixed with an exponentially growing bacterial culture and top agar and poured on an LYBHI Agar plate as described above. After 16 h of incubation at 37 °C, lysis was confluent, and 2 ml of SM buffer were poured on the top of the plates and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h. The phage supernatant was then recovered and filtered at 0.2 µm.

Bacterial DNA extraction from faeces

Bacterial pellets obtained during free phage extraction from faeces were resuspended in 500 µL of LB (Difco). The suspension was centrifuged 1 min at 500 × g to remove debris. Supernatant was recovered and mixed with 250 µL of lysis buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 5% SDS), 250 µL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1; [pH 8.0], Sigma Aldrich) and half of a tube of silica beads (100 µM MP Bio, Lysing matrix B). Bacteria were lysed using Fast-prep MPBio (5.5, 3 × 30 s, 5 min between each cycle). Samples were then centrifuged (13,000 × g, 3 min, 20 °C) and the aqueous phase recovered. After addition of 400 µL of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1), the mix was vortexed vigorously (10 s) and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 3 min, 20 °C). DNA was precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol and 0.3 M of sodium acetate and resuspended in 100 µL of water.

Phage and bacteria quantification by qPCR

qPCR on 100-fold diluted samples was performed using the Takyon ROX SYBR Mastermix blue dTTP kit (Eurogentec) and the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystem). Phage and bacteria amounts were determined using specific primer pairs (Table S3). Because we made absolute quantification, only one gene was used as standard to quantify phage and bacteria populations. Standard gene are indicated in Table S3, as primer targets. Numbers of copies in standards were calculated using DNA quantification (Qbit) and the strain genome size. Quantification of chromosomal DNA contamination was performed on each phage sample in experiment 1, and was always below 1% that of phage DNA. The reaction mix was the following: 7.5 μl Takyon mix, 0.9 μl H2O, 0.3 μl of each primer (200 nM final concentration), 6 μl of DNA diluted in H2O. The PCR conditions were: (95 °C 15 s, 58 °C 45 s, 72 °C 30 s) 45 cycles, 72 °C 5 min, followed by melting curves. Results were analysed using the StepOne Software 2.3.

Isolation of R. intestinalis clones from mouse faeces

One or two faeces were recovered from mice, sealed immediately in screw cap micro tube, transferred to an anaerobic chamber (see bacterial culture), diluted in 0.5 mL of PBS 1X. 20 µL of this bacterial suspension was then streaked on GHYBHI plates (brain-heart infusion medium supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract, 1.5% agar, cellobiose (1 mg/ml [Sigma]), maltose (1 mg/ml [Sigma]), cysteine (0.5 mg/ml [Sigma]), Hemin 0.5% and ciprofloxacin at 2 µg/mL). After 24–48 h of growth at 37 °C, isolated clones were grown 24 h at 37 °C in liquid LY-BHI medium, frozen with 20% of glycerol and kept at −80 °C until analysis.

Quantification of Shimadzu cured bacteria

In an anaerobic chamber, bacteria either from a growing culture (OD600 = 0.3) or from a frozen faeces were rapidly diluted in cold PBS to prevent reinfection and plated on LYBHI agar plates. Individual clones were used to inoculate two 96 well microplates per condition. After a 16 h incubation at 37 °C, PCR with either attB or attL primers (Table S1) was realised on 1 µl of bacterial cultures, and the proportion of attB positive clones determined. Quantitative PCR was performed on bacterial DNA as described above with attB and sigA primers, and the proportion of cured bacteria determined as the attB over sigA copy numbers.

Shimadzu susceptibility assay in 96 wells microplates

A 96 well microplate (Cellstar, 96 Well Cell Culture Plate, U-bottom) was inoculated with 96 different clones and duplicated for conservation at −80 °C and subsequent tests. For each test, frozen cultures kept in a 96 well microplate were used to inoculate a microplate filled with 200 µl of LYBHI. Overnight cultures were diluted 50-fold and grown at 37 °C for 2 h in 50 µl. Overall, 5 µl of a phage lysate at a concentration of 109 pfu/ml was added and the microplate incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Cultures were then diluted fourfold in warm LYBHI and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Absorbance at 600 nm was then measured in a TECAN SUNRISE, and compared with the absorbance of cultures grown in similar conditions but with no phage. Clones were considered susceptible to the phage if the absorbance at 600 nm of the culture with phage was more than twofold lower than that of the culture without phage. The experiment was repeated two times for all clones and a third time for clones that gave incongruent results.

Shimadzu susceptibility assay on agar plates

A 5 µl drop of phage suspension containing ~105 PFU was spotted on a lawn of R. intestinalis in top agarose as described above, and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Confluent lysis at the position of the drop indicated bacterial susceptibility, whereas reduction over at least 4 Log was considered as an indication of bacterial resistance.

Bacterial numeration by microscopy

10-fold dilutions of freshly passed faeces in PBS were spread on an agarose pad on a microscope slide and imaged at ×100 magnification by a microscope (Zeiss Axioskop2Plus; camera Zeiss axiocam ICc1), in phase contrast. E. coli and R. intestinalis cells were manually counted (Fig. S1). We analysed more than 50 cells on 3 different images for each condition. In parallel, E. coli CFU were numerated on LB agar plates. The concentration of R. intestinalis cell was obtained by multiplying the concentration of E. coli deduced from plating by the ratio of R. intestinalis on E. coli cells obtained by microscopy.

Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM)

For Jekyll virion observation, 100 mL of R. intestinalis culture supplemented with 1 µg/mL of mitomycin C were centrifuged and the supernatant filtered through a 0.2 μm filter, concentrated with PEG and 0.5 M NaCl as described above and then purified by ultracentrifugation (20,000 × g, 2 h, 4 °C) on a 3 layers iodoxanol gradient (concentration of 0, 20% and 45% of iodoxanol). Virions were recovered at the interface between the 20% and the 45% layers. Shimadzu virions were extracted from mice faeces resuspended in PBS. After centrifugation for 2 min at 10,000 × g the supernatant was filtered (0.22 µm) and then concentrated using an ultrafiltration device Amicon Ultra 2 mL with a cut-off of 100,000 Da (Millipore). For both phages, droplets of phage preparations were directly placed on Formvar carbon-coated grids for 5 min. The grids were stained with 1% uranyl acetate and then viewed for TEM using a HITACHI HT 7700 (Elexience, France) at 80 kV. Microphotographies were acquired with a charge-coupled device camera AMT.

R. intestinalis L1-82 sequencing, assembly and annotation

Genomic DNA was extracted from a bacterial culture with a standard phenol:chloroform protocol preceded by a lysis step with lysozyme and SDS, as previously described. Sequencing was realised using the PacBio technology. Long reads were quality controlled with NanoPlot v1.8.1 [46]. Sequencing produced 202,572 reads of N50 12,694 nucleotides for a total run of 1,214,051,359 bases. This corresponds to a sequencing depth of 270x. Assembly was performed using Canu 1.6 [47] with default parameters except genomeSize = 4.5 m and pacbio = raw. Two contigs were produced by the assembler, one corresponding to the chromosome, the other of 21,201 nucleotides with a GC% of 0.01%. The second was considered spurious and removed from the analysis. A run of Illumina paired-end sequencing (5,827,730 paired-reads of 151 bp) was conducted to correct the remaining error. Reads were first mapped on the PacBio assembly using BWA 0.7.12-r1039 [48], then the assembly was corrected using Pilon 1.22 [49]. Overall, 290 corrections of the initial assembly were performed, mostly indels correction. A final single circular contig of 4,493,348 nucleotides was obtained, and its first nt was chosen at the shift of the genome GC skew, near the dnaA gene. The genome was then annotated with Prokka [50], and prophage genes and boundaries were manually edited. The new version of the genome has been deposited on the EBI database under accession number ERZ773328. On Shimadzu prophage, promoters of cI and cro genes were searched with DBTBS (http://dbtbs.hgc.jp/) [51].

Detection of mutations in the sequenced bacterial isolates

Research of SNPs in bacterial genomes was made using the reference L1-82 genome, using reads generated by Illumina sequencing and analysed using the PATRIC web interface (https://patricbrc.org) [52]. Mapping was made using BWA-MEM and SNP were searched with Freebayes with default parameters. Prophage insertion in clone 4 was first evidenced by the twice higher read coverage on the region corresponding to the Shimadzu prophage, following reads alignment using bowtie2 (-N 1 –L 32) and visualisation with Tablet using default parameters [45]. The position of the second prophage was determined by recovering, at each prophage border, the sequence of 10 clipped reads. These “hybrid” reads were then aligned with BLASTn to the L1-82 genome, revealing the insertion site. CRISPR spacer insertion was detected as in other clones, as described below.

Shivirs and virome sequencing

Overall, 5 ml of ultravirulent phage stocks (concentration above 109 PFU/ml) were concentrated with 10% PEG8000 and 0.5 M NaCl. Alternatively, for virome sequencing, virions were extracted from two to three mouse faeces as described above for qPCR. In both cases, viral DNA was then extracted with a standard phenol:chloroform protocol. DNA was sequenced either by GATC-Eurofins with the Illumina technology (2 × 125 nt), or, in the case of virome 1, with IonTorrent (300 nt reads) in the INRA metagenopolis platform.

Shivir mutation analysis

Raw reads were quality filtered using Trimmomatic [53] in order to remove paired reads with bad qualities (with length <100 bp, with remnant of Illumina adaptors and with average quality values below Q20 on a sliding window of 4 nt). The filtering process yielded an average of 1 to 3 million paired-end reads (2 × 150 bp) per sample. Point mutations and small indel were detected by alignment of reads using bowtie2 (-N 1 –L 32) and visualised with Tablet using default parameters (https://ics.hutton.ac.uk/tablet/). Since Shivir were multiplied on L1-82 strain that carries the ancestral Shimadzu prophage, ~20% of reads corresponded to the wild-type Shimadzu sequence. Putative larger deletions or insertions were searched by assembling the filtered reads using SPAdes [54] with the meta option and increasing kmer values (-k 21,33,55,77,99,127). The resulting contig was then compared by BLASTn to the ancestral Shimadzu.

Analysis of viromes

A first search of SNP was performed similarly to the Shivir analysis. The more thorough analysis of the VR regions was performed as follows. First, using Tablet, all reads covering the VR region of interest and 20 extra nt on each side (for 300 nt-long reads, virome 1), or at least one side (for 125 nt-long reads, virome 2) were downloaded. We reasoned that the various VR alleles in a given virome should group together in a phylogenetic tree. These reads were therefore used for a multi-alignment with MUSCLE [55], which was then trimmed with Gblocks, and given to PhyML on the LIRRM interface [56] to build a tree (default parameters, when more than 500 reads were present, two subpopulations were made and treated in parallel). Several clear flat branches per tree were obtained, corresponding to the main alleles of a given VR. The number of leafs of each such cluster was counted, and by substraction, the remaining reads were considered as singleton alleles. A read of each main cluster was then used to determine the amino-acid sequence of each VR allele. To determine allele proportions, a mapping of virome reads on each VR allele was performed with bowtie2, allowing 0 mismatch (-N 0 –L 20).

Detection of spacer acquisition

Spacer acquisition was determined by a PCR test (primers in Table S1). PCR products were observed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

Detection of mutations by Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing of the R. intestinalis sbpE and CRISPR loci was performed on DNA substrates generated by PCR amplification of bacterial DNA purified from mouse faeces with primers in Table S1, using standard procedures. Sequences of the Shimadzu VR1 and immunity region were similarly obtained from PCR amplification products of viral faecal DNA. Manual inspection of sequencing traces revealed peak mixtures, indicative of the presence of mutants in the population.

Results

Roseburia intestinalis L1-82 harbours two active prophages

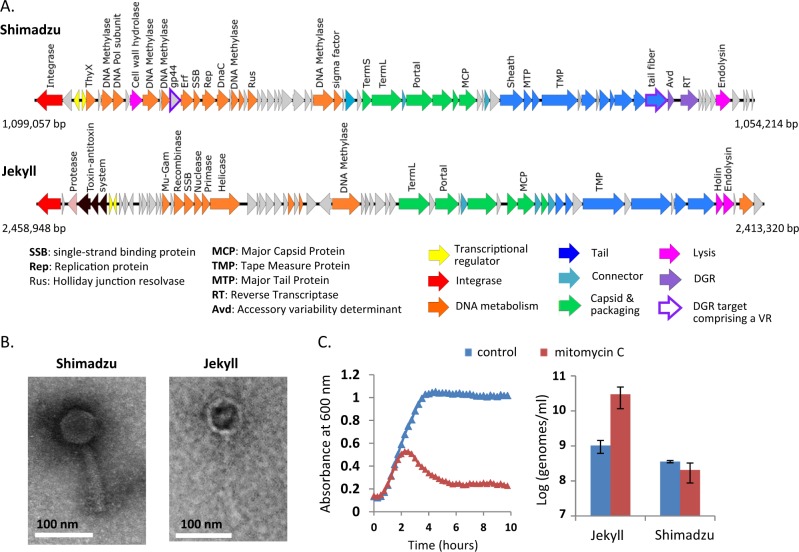

The sequencing and complete assembly of R. intestinalis L1-82 genome revealed the presence of two complete prophages, that we named Shimadzu and Jekyll (Fig. 1a). The production of virions by these prophages was determined by sequencing encapsidated DNA, i.e., DNA protected from DNAse in a culture supernatant. Resulting reads predominantly aligned on the two identified prophages (respectively 60% and 19.4% of total reads, the last 20% of reads aligning to the L1-82 genome), indicating that both prophages produce virions. Of note, read coverage was highly uneven on the Jekyll prophage, suggesting that besides the full size phage genome, a shorter version is also encapsidated (Fig. S2A). Phage genomes were annotated using RAST [57], HHPRED [58] and Phagonaute [59]. Interestingly, the Shimadzu integration site is located within its integrase gene int, encoding a large serine recombinase. Consequently, two different integrases are produced during the lytic cycle and during lysogeny (Fig. S2B). The two forms differ by their last 22 amino acids, which might modify the stability of the protein, as described in mycophages [60].

Fig. 1. Roseburia intestinalis L1-82 prophages.

a Genetic maps of Shimadzu and Jekyll prophages. Positions in R. intestinalis L1-82 genome are indicated. b Transmission electron microscopy images of Shimadzu and Jekyll virions. c Prophage induction by mitomycin C. Left panel: Absorbance of R. intestinalis L1-82 cultures with or without mitomycin C (0.5 µg/ml). Mitomycin C is added at time 0. Right panel: free phage genome concentrations in bacterial culture supernatant 4 h after the addition of mitomycin C. Mean ± standard deviation of three measures.

The Jekyll genome had no significant nucleotide similarity with any viral genome of the NCBI RefSeq genome database, indicating that it corresponds to a new viral clade. The Virfam classification tool, that uses virion protein remote homology and gene synteny [61], clustered Jekyll with phages infecting Bacilli species. The Shimadzu genome presented homology with the Faecalibacterium prausnitzii phage Lagaffe (Fig. S2C), and grouped within a badly-resolved Virfam cluster comprising E. coli lambda phage. Electronic microscopy showed that Jekyll is a Siphoviridae, and Shimadzu a Myoviridae (Fig. 1b), in line with genomic predictions. Quantitative PCR on encapsidated viral DNA indicated that the virion concentration in saturated culture supernatants was 3·108 and 8·108 virions/mL for Shimadzu and Jekyll, respectively. Interestingly, Jekyll, but not Shimadzu, was induced by mitomycin C, a genotoxic agent causing DNA damage, a general signal for prophage derepression (Fig. 1c).

Similarly to F. prausnitzii phage Lagaffe, Shimadzu encodes a Diversity Generating Retroelement (DGR) (Fig. S3). DGRs generate variability in target genes through a reverse transcriptase (RT)-mediated mechanism that introduces nucleotide substitutions at defined locations, called variable repeats (VRs) (reviewed in [62]). VRs are homologous to a template repeat (TR), located directly upstream the reverse transcriptase, and used as a template to generate variation. As sometimes observed [62], two VRs could be detected in Shimadzu: the first one, VR1, is located in a predicted tail gene located just before the reverse transcriptase, a commonly observed position, and the second, VR2, is located in orf43, of unknown function (Figs. 1a and S3). Analysis of sequence reads obtained from virions collected from in vitro culture supernatants indicated that both VRs are successfully modified by the DGR: 2 % of reads aligning to the VRs had 10–15 mismatches, which is typical of DGR-mediated mutagenesis, whereas only 0.1% of reads outside this region exhibited 1–2 mismatches.

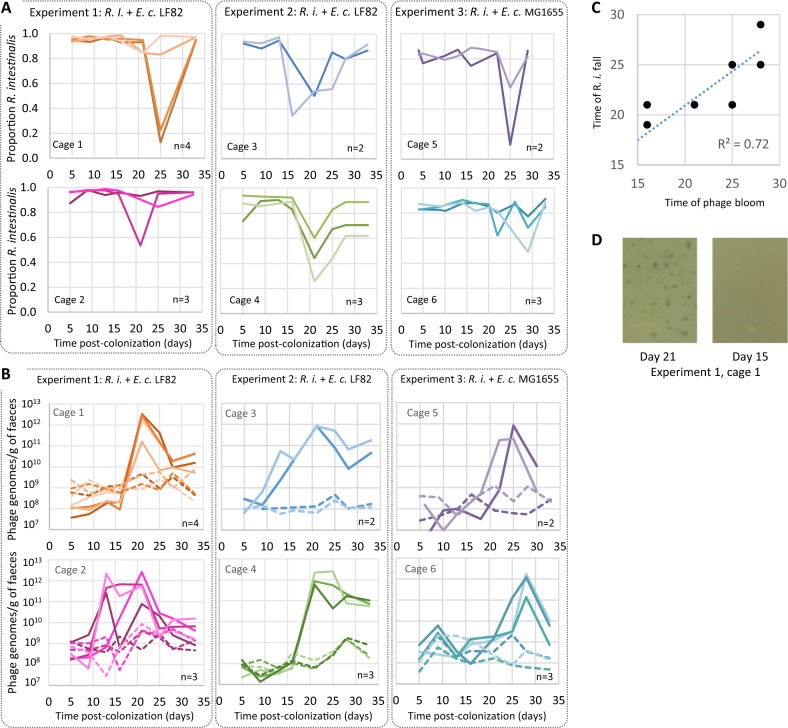

R. intestinalis and Shimadzu populations exhibit important temporal variations in mice

We then examined free phage and bacterial populations in germ-free mice colonised with R. intestinalis L1-82 and either E. coli LF82 (experiments 1 and 2) or E. coli MG1655 (experiment 3). Mice were first colonised with E. coli, and after 2 days, when E. coli populations were close to 3 × 109 CFU/g (Fig. S4), R. intestinalis was introduced to mice (day 0 of the experiment). Each experiment comprised 5–8 mice housed in two different cages placed in the same isolator. Phage and bacterial populations were monitored by quantitative PCR and/or microscopy in faeces for 33 days (Fig. S1). R. intestinalis became rapidly dominant over E. coli, reaching 96 ± 2.5% of the population after 5 days of colonisation (Fig. 2a). However, in each cage, a significant collapse of R. intestinalis was observed in the majority of mice after 16–25 days of colonisation (Fig. 2a), while E. coli populations remained stable (Fig. S4). Since mice were kept in a constant and closed environment, we hypothesised that one of the two R. intestinalis L1-82 prophages could be responsible for this change in bacterial composition. During the first 10 days of colonisation, the concentration of Jekyll and Shimadzu virions in mouse faeces was close to 5 × 108 virions/g of faeces, indicating a high level of spontaneous induction, as previously observed in vitro (Fig. 2b). Afterwards, Jekyll free phage concentration remained constant but Shimadzu concentration suddenly increased by more than a thousand fold, reaching up to 1012 virions/g of faeces after 13–25 days of colonisation, before decreasing and stabilising around 4 × 1010 virions/g (Fig. 2b). Similar results were observed in mice colonised with the two different E. coli strains, ruling out potential effects of E. coli LF82 virulence genes on phage production.

Fig. 2. Variations with time of R. intestinalis and phage populations in mouse faeces.

Each panel corresponds to a different cage, hosting two to four mice (each with a specific shade of colour). In each experiment, two cages (1 & 2, 3 & 4, or 5 &6) were placed in the same isolator. Mice from cages 1–4 were colonised with E.coli LF82, whereas mice in cages 5 and 6 were colonised with E. coli MG1655. a Variation with time of the proportion of R. intestinalis over total bacteria. These proportions were estimated by quantitative PCR in experiments 1 and 2, and by microscopy in experiment 3. b Evolution of the concentration of Shimadzu (solid line) and Jekyll (dashed lines) free phage genomes. c Day of R. intestinalis population collapse as a function of day of Shimadzu bloom. d Lysis plaques on a lawn of R. intestinalis could be obtained from mouse faeces at day 21 (left panel) but not at day 15 (right panel).

Shimadzu multiplication is responsible for R. intestinalis mortality

Shimadzu free phage concentration was maximal shortly before the fall of concentration of R. intestinalis (Fig. 2c, R2 = 0.72), strongly suggesting phage-related bacterial mortality. Yet, as discussed earlier, prophages provide resistance to superinfection, i.e., lysogenic bacteria are immune to infection by a phage that is present as a prophage in its genome. The sudden multiplication of Shimadzu could thus result either from the invasion of ultravirulent mutants able to infect lysogenic cells, or from a sudden environmental signal triggering a massive prophage induction. In favour of the first hypothesis, lysis plaques were obtained from mouse faeces collected after 21 days of colonisation on R. intestinalis L1-82 lawn (Fig. 2d). A PCR test indicated that these lysis plaques correspond to Shimadzu ultravirulent mutants. Their first detection at the time of phage bloom reinforces the hypothesis that they are at the origin of the free phage bloom. Of note, the number of plaque-forming units (PFUs) obtained corresponded to 102–106 PFU per gram of faeces, far from the 1012 virions estimated by quantitative PCR. Quantification of three phage stocks revealed a 100-fold difference between genome copy numbers determined by qPCR and PFUs, which we did not observe for other phages (Fig. S1C), suggesting that most virions are uninfectious in these conditions. Yet, this 100-fold difference does not entirely explain the difference observed in faeces between PFU and virions. The remaining difference could result either from damage of virions during extraction or from genetic heterogeneity in the population of Shimadzu in mouse faeces, with only few phage genotypes being able to infect R. intestinalis L1-82 in vitro. Nevertheless, the isolation of phages on L1-82 indicated that Shimadzu ultravirulent mutants were present in mice, most probably explaining bacterial mortality.

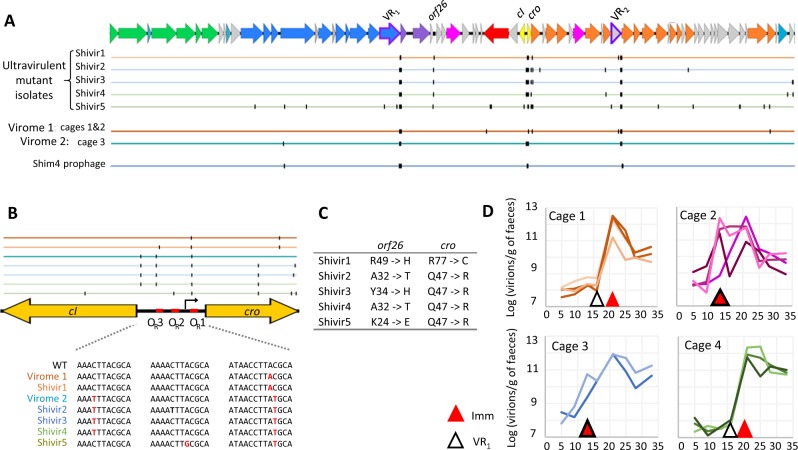

The bloom of Shimadzu free phage is associated with few dominant mutations

To identify the mutations responsible of the ultravirulent phenotype, we sequenced five phages, isolated either from experiment 1 (Shivir1) or from experiment 2 (Shivir2, 3 and 4) after 21 days of colonisation, and Shivir5 isolated after 33 days of colonisation from cage 7 of experiment 2. Each phage genome contained between 34 and 45 mutations, but only four loci were mutated in the five isolates: the two VRs targeted by the DGR (~10-15 mutations per VR), a region comprising two inversely oriented transcriptional regulators, named immunity region, and finally orf26, of unknown function (Fig. 3a). To know if these mutation hotspots represented a general trend rather than biases due to phage isolation, we sequenced total phage DNA (virome) isolated from mouse faeces harvested after 21 days of colonisation. Virome 1 corresponds to a pool of faeces from the 8 mice of experiment 1, whereas virome 2 corresponds to a single mouse of experiment 2. In both viromes, in Shimadzu, mutations in the immunity region, in VR1 and in VR2 were respectively present in ~70%, ~65% and 47% of aligning reads. No other locus was mutated in more than 20% of covering reads (Fig. 3a, b). For example, the mutation in orf26 was present in only 5% of aligning reads in virome 1, and even less in virome 2, indicating that this mutation is not essential for Shimadzu multiplication in mice. Non-synonymous mutations in all five phage isolates (Fig. 3c) suggests mutations in orf26 are nevertheless necessary to form lysis plaques in vitro, and might explain the discrepancy between PFU and phage copy numbers in faeces discussed above. In Jekyll, no mutation was observed in virome 1. Yet, a single point mutation was observed in virome 2 (from a single mouse), in a putative helicase gene, for which we have no explanation.

Fig. 3. Mutations in ultravirulent Shimadzu phages.

a Representation of mutation positions in virome 1 (from all mice of experiment 1) and 2 (from one mice of cage 3 in experiment 2), and in ultravirulent phage isolates. Colour of the line indicates the mouse from which the phage was isolated (cage of isolation). b Upper panel: Mutation positions in the immunity region of Shimadzu, comprising the repressor genes cI, cro, and the intergenic region with three operators. Lower panel: zoom on the mutations in the operators. c Amino acids mutated in orf26 and cro in ultravirulent isolates. d Time of first detection of mutations in the operators and in the VR1, in total faecal viral DNA.

In the two viromes, Shimadzu VR1 variants comprised only one to three dominant alleles. All ultravirulent isolates from experiment 2 had the same VR1 allele (with the exception of a point mutation in Shivir2), which corresponds to the second most dominant allele in the virome 2 (Table S1). By contrast, all isolates carried different VR2 alleles, that differed from the most abundant ones in the corresponding virome. In addition, in virome 1, the most abundant VR2 alleles represented only 3% of reads (Table S1). This suggests stronger positive selection of VR1 alleles as compared with VR2, that could result from a higher importance of the tail protein-containing VR1 for infection. Clearly, more experiments would be required to conclude on the role and importance of the DGR of Shimadzu.

The mutated region comprising two inversely oriented transcriptional regulators is most probably the immunity region, that controls prophage maintenance and resistance to superinfection. Indeed, similarly to the immunity region of the model phage lambda, the intergenic region comprises three almost identical repeats, known as operators (OR), and a putative promoter. In phage λ, the two transcriptional regulators cI and cro are under mutually exclusive expression: during lysogeny, ORs are fixed by CI repressor, preventing the expression of cro and the downstream lytic cycle genes, and vice versa during the lytic cycle. Upon superinfection, CI repressors will also bind the OR of the incoming phage, preventing the expression of its lysis genes, and conferring immunity. All five ultravirulent phages have a mutation in cro and in OR1 (Fig. 3b, c). These mutations might diminish or even abolish the binding of CI repressor produced by the resident prophage, enabling the incoming phage to multiply in lysogens. Mutations in OR2 or OR3 were also observed in some isolates, probably accentuating this phenotype.

Of note, only 70% of reads had a mutation in the immunity region, indicating that the overall production of phages (wt and ultravirulent) has increased, and not only ultravirulent mutants. A possible explanation is that infection of R. intestinalis lysogens by ultravirulent mutants induced the resident wt prophage, resulting in the production of both wt and ultravirulent virions. Indeed, this phenomenon was also observed in vitro: when the Shimadzu ultravirulent mutant was propagated on L82 wt, both wt and mutant reads were observed, in proportions similar to those in vivo (about 2/3 of mutant sequences).

Mutations in the immunity regions appear concomitantly to the phage bloom

To gain insights into the respective role of the mutations described above in Shimadzu multiplication and phage bloom, we then examined their timing of selection by PCR sequencing of faecal filtrates at different time points (Fig. 3d). Given that dominant VR2 alleles in virome 1 represented only 3% of sequences, and that each phage isolate had a different allele, we concluded that the VR2 containing gene might be less essential for Shimadzu multiplication, and we focused on the VR1 and the immunity region. Important VR1 diversification was detected before the onset of the phage bloom in two cages, indicating the selection of mutant alleles prior to phage bloom (Fig. 3d). This selection indicates that, even prior to the phage bloom and the presence of ultravirulent mutants, free phage production did not only result from spontaneous prophage induction, but also from an infection process. This infection probably concerned only a small subpopulation of bacteria since neither an increase in free phage titers, nor a bacterial population decrease, could be detected at that time. We hypothesised that the bacterial population responsible for the multiplication of these VR1 mutated phages could consist of bacteria having lost spontaneously the Shimadzu prophage. On such a population, VR1 allele selection could occur if the ancestral tail fibre gene is not permitting efficient infection. Screening of bacterial clones isolated either from an in vitro culture or from mice faeces after 13 days of colonisation (200 clones in each case) revealed in both situations a proportion of cured bacteria close to 5 × 10−3. Such proportion was confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 4h). By contrast to VR1 mutations, mutations in the operator OR became dominant concomitantly with the phage bloom in all mice (Fig. 3d), definitely associating the major phage multiplication peak with the evolution of ultravirulence.

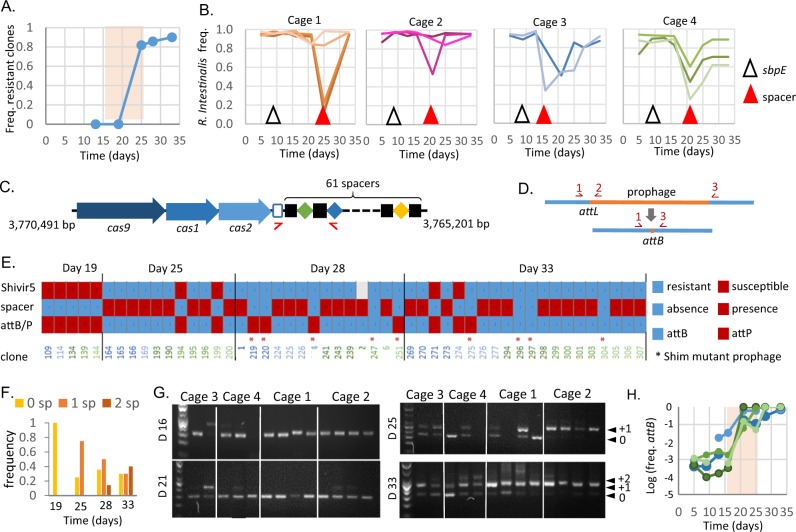

Fig. 4. Phage resistance is associated to CRISPR spacer acquisition or to lysogenization by a prophage with a new immunity type.

a Proportion of bacterial clones resistant to Shimadzu with respect to isolation time in experiment 2. The pale pink region indicates the time of Shimadzu bloom. b Time of first detection of mutations in sbpE and of spacer acquisition in total bacterial DNA from mouse faeces. c Type II-C CRISPR-Cas system of R. intestinalis L1-82 and positions of primers used for detection of spacer acquisition. Positions in the bacterial genome are indicated. d Schematic representation of Shimadzu attL and attB sites, and their detection by PCR. e For 52 isolated clones, are indicated: Shivir5 resistance (upper line), spacer acquisition (middle line), presence of attB or attL sites (lower line), and presence of a Shim prophage with cro inversion (*). The colour of clone number corresponds to the mouse from which it has been isolated, as in Fig. 2. Sequenced clones correspond to numbers 1, 2, 4 and 6. Clones isolated at earlier time points were all identical to those of day 19 and therefore not included in the figure. f Frequency of clones with 0, 1 or 2 new spacers as a function of isolation time. g Spacer acquisition in total R. intestinalis population from faeces at four different time points (day 16, day 21, day 25 and day 33). DNA ladder is a 50 pb scale. Smaller PCR fragments correspond to the wild-type size (indicated by “0”), the acquisition of 1 spacer to “+1” and 2 spacers to “+2”. h Population level of Shimadzu cured R. intestinalis, in mice from different cages. Cage is colour coded as in B panel.

Ultravirulent phages drive the fast selection of resistant bacteria

Despite the systematic and massive multiplication of Shimadzu in all mice, R. intestinalis concentration almost recovered its initial level after 30 days of colonisation, and in some mice the bacterial population was barely affected by the ultravirulent phages (Fig. 2). These observations hint at the rapid emergence of resistant bacteria. To investigate this phenomenon, a total of 300 R. intestinalis clones were isolated after 16, 19, 25, 28 or 33 days of colonisation in experiment 2. Ninety-six of them were grown in the presence or absence of ultravirulent phage Shivir5, which showed the best lysis ability of bacteria in liquid cultures. Phage resistance was defined as the absence of bacterial biomass reduction by the phage. For two additional Shivir mutants, a smaller scale analysis (on 10 bacterial clones) by plaque assay revealed an identical susceptibility pattern, i.e., clones resistant to Shivir5 showed a reduction of the efficiency of plating of the other ultravirulent phages by at least 4 log. The proportion of resistant clones dramatically increased after the phage bloom (Fig. 4a), explaining the recovery of R. intestinalis population in mice.

Resistance is mostly related to the acquisition of phage-directed CRISPR-Cas spacer

Bacteria have developed an incredible number of mechanisms to counter phage infections (reviewed in [63]). To get insight into the mechanisms involved, 4 resistant clones of R. intestinalis isolated after 28 days of colonisation were entirely sequenced. Each of them contained between 20 and 34 point mutations, but only gene sbpE (RiL182_04007), presenting homology to a Bacillus subtilis extracellular solute-binding protein gene, was mutated in all clones. In particular, SbpE mutation I341T was dominant in the mouse gut early on, after only 9 days of colonisation (Fig. 4b), and long before the Shimadzu bloom, suggesting that SbpE is associated to adaptation to the mouse gastrointestinal tract rather than to phage resistance.

Sequencing also revealed in three of the four isolates the insertion of a 30 base pair sequence homologous to the Shimadzu genome (Table S3), in a CRISPR array, of type II-C (Fig. 4c). CRISPR and their associated genes, CRISPR-Cas immune systems, provide phage resistance by integrating short phage-derived sequences (spacers), generally at the leader end of the CRISPR array, similarly to what we observed. Type II-C CRISPR-Cas systems function by cleaving invading DNA homologous to spacer sequences. Spacer acquisition was investigated in the clones tested for Shivir5 susceptibility: more than 75% of the resistant clones had acquired a new spacer, but none of the susceptible clones (Fig. 4c, e), and the proportion of clones with two additional spacers increased with time (Fig. 4f). Sequencing of newly acquired spacers in 10 other clones showed that they all possess one or two Shimadzu-derived spacers, and two clones also possess a spacer that targets the R. intestinalis genome (Table S3). The already described cost associated with autoimmunity of CRISPR-Cas type II systems [64] was apparent because these two clones displayed altered growth, especially on plates. Finally, spacer sequencing revealed the presence in the same mouse of clones with different spacers, suggesting several spacer acquisitions in the same mouse.

To confirm that bacterial resistance through CRISPR-Cas activity is general and does not result from biases in the isolated clones, we monitored spacer acquisition on total bacterial DNA from mouse faeces (Fig. 4g). In each cage, important spacer acquisition was first evidenced at the onset of bacterial recovery (Fig. 4b). In addition, the number of acquired spacers increased with time, exactly as in isolated clones (Fig. 4f). Altogether, these results indicate that CRISPR-Cas activity is the main R. intestinalis resistance mechanism against ultravirulent Shimadzu phage in the mouse gut.

Spacer acquisition is associated with the loss of Shimadzu prophage

Out of the four R. intestinalis clones sequenced, the three clones with an additional spacer had also lost the Shimadzu prophage. By contrast, Jekyll prophage was intact in all four sequenced clones. Amplification by PCR of either Shimadzu attB, the site formed by prophage excision, or attL, a site formed by prophage presence (Fig. 4d), revealed the absence of Shimadzu in all 32 clones with a new spacer (Fig. 4e). To evaluate the representativeness of the isolated clones, we determined by quantitative PCR the evolution with time of the global proportion of faecal bacteria with intact attB site. This proportion remained close to that estimated by screening of isolated clones, 5.10−3, for the first two weeks of colonisation (Fig. 4h). Yet, after phage bloom, the proportion of bacteria with an intact attB site dramatically increased in all tested mice: Shimadzu-derived spacer acquisition most probably selected cured bacteria because of the important cost associated with autoimmunity.

Resistance is also mediated by a prophage with a modified immunity region

By contrast, the fourth sequenced clone (clone 4 in Fig. 4e), had no additional spacer but a second Shimadzu prophage, inserted in a tRNA at position 3,542,165 of the genome. Sequence analysis revealed that some prophage positions were mutated in 50% of aligning reads, suggesting that the second prophage, named Shim4 (for Shimadzu prophage with modified Immunity region located in clone 4), was mutated at these positions (Fig. 3a). In particular, two different alleles of both VRs could be identified, and the VR1 mutant allele was identical to that of the ultravirulent Shivir phages isolated from the same experiment (Table S1). No mutation in orf26 was identified, reinforcing the idea that such mutations are not essential for infection in vivo. In the immunity region, the same three point mutations observed in corresponding virome 2 were detected, but the cro gene and its promoter were inverted (Fig. 5a). This inversion might lead to an increased expression of CI repressor, enabling to restore the resistance to superinfection of the lysogen. To investigate the generality of this phenomenon, we looked for the presence of such Shim prophage with an inversion of cro in the eight other clones that were resistant to Shivir infection but that had not acquired an additional spacer. We could amplify by PCR the Shimadzu immunity region in all isolates, even in clones with an intact attB site, indicating the presence of a prophage at another genomic position than in the ancestral L1-82. An inversion of cro gene was evidenced in all eight isolates (Fig. 4e). These bacterial isolates still produced virions, albeit at a level much lower than the ancestral L1-82 strain or other lysogens isolated from mice, comforting the hypothesis that they produce more CI repressor in the prophage state than the L1-82 (Figs. 5b and S5). Altogether, ultravirulent phage resistance of the 40 clones tested result either from spacer acquisition or from lysogenization by a phage with a new immunity type. A summary sketch of the results is proposed in Fig. 6.

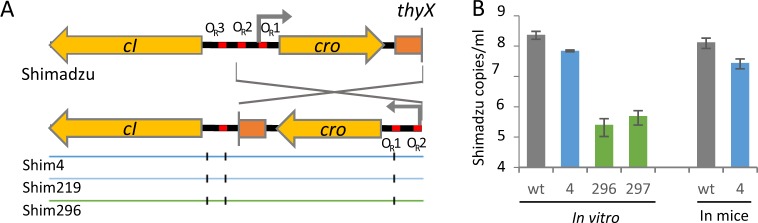

Fig. 5. Prophage Shim has an inverted cro region.

a Zoom on the immunity region, showing the cro inversion in Shim prophage and the 3 point mutations. b Spontaneous Shimadzu virion production in clones 4, 296, 297 and in L1-82 ancestral clone, in vitro or in mouse faeces from mice colonised either with L1-82 ancestral clone or clone 4, after 3 days of colonisation. Clone 4 is a dilysogen harbouring two prophages, Shimadzu wt and Shim, the other clones only contain a Shim prophage. Mean ± s.d of three measures by qPCR quantification.

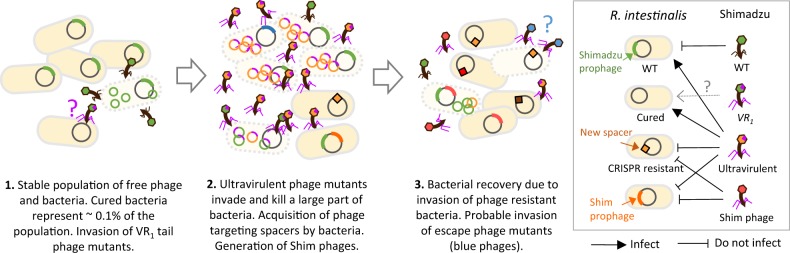

Fig. 6. Summary sketch of the results.

In a first step, stable populations of free phage and bacteria are observed. Yet, complex dynamics might already occur, as 0.1% of bacteria are spontaneously cured of the Shimadzu prophage, and phages with mutant VR1 alleles are selected and become dominant in some mice, possibly because they can infect cured bacteria. In a second step, a free phage bloom occurs due to the invasion of ultravirulent Shivir mutants that multiply on lysogenic bacteria. Some bacteria acquire a spacer targeting the phage in the CRISPR-Cas system. Shimadzu lysogenic bacteria are killed by spacer acquisition because of autoimmunity. Other bacteria are lysogenized by modified ultravirulent phages with a restored ability of lysogenization (Shim phages). In a third step, resistant bacteria invade, leading to the recovery of the bacterial population. Free phage titres remain high, indicating on-going infection, possibly due to the invasion of escape phage mutants.

Discussion

The prophage state is generally considered a dormant state that gives little opportunity for viral evolution, since viruses mutate much faster during lytic replication than during lysogenic cycles [65]. This might explain why the coevolution between temperate phages and bacteria has been much less studied than between virulent phages and bacteria [12, 66]. Yet, theory predicts that ultravirulent mutants should invade the phage population when bacterial hosts are numerous and therefore transmission is high, i.e., when the benefit of superinfection outweighs the cost of the loss of lysogenization capacity [30, 67]. Here, we followed the coevolution between R. intestinalis L1-82 and its prophages for 33 days in the mouse gut, and demonstrate that Shimadzu ultravirulent mutants systematically invade, leading to major phage-mediated mortality of R. intestinalis. In addition, in agreement with theory [30], we observed in some cases later invasion of compensatory mutations that restore lysogenization ability and provide resistance to the ultravirulent mutants. Since the large majority of bacteria of the human microbiota harbours prophages [24, 26], this kind of dynamics might regularly occur, leading to massive phage-induced bacterial mortality, and participating in the variations in microbiota composition.

Even though predicted by theory, evolution of ultravirulence was considered to only rarely arise in nature, and, to the best of our knowledge, had only been observed in industrial setups, where large bacterial population size favours the appearance of mutants [39, 68, 69]. Based on results with lambda phage, the best-known example of lysogeny regulation, this rarity was proposed to stem from the fact that a double mutant would need to be generated, and the probability of acquiring two simultaneous mutations is very small during lysogeny [70, 71]. Because of this presumed rarity, the evolution of ultravirulence is rarely, if ever, considered when referring to lysogeny in host-associated microbiota. Similarly to what was shown with lambda, all ultravirulent Shimadzu mutants had at least two mutations in the immunity region, generally in operators OR1 and OR3. Yet, when a single strain dominates at high concentration, as in gnotoxenic mice, our results show that ultravirulent mutants with several simultaneously acquired mutations can be generated. Single-strain stability, i.e., the presence of a single dominant strain, was observed for numerous species of the gut microbiota [72], and in particular for Roseburia species [73], suggesting that the environmental conditions necessary for ultravirulence evolution should be present in natural gut ecosystems. Most probably, some specific phage genetic features are also required. In particular, whether the phage DGR system and/or the presence of spontaneously cured bacteria facilitated ultravirulence evolution is a very interesting open question that deserves further investigation.

Here phage infection resulted in the fast selection of resistant bacteria in the mouse gut, contrary to what is generally observed in vivo (reviewed in [74]). This absence of genetic resistance selection was interpreted as a result of physiological bacterial resistance to phage infection in the mouse intestine, resulting from its complex structure and slow bacterial growth [22, 75, 76]. In our experiments, almost all bacterial clones isolated after the emergence of ultravirulent phages were resistant, indicating very efficient phage-mediated selection and thereby particularly efficient multiplication of Shimadzu in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. To the best of our knowledge, our work constitutes the first examination of phage–bacteria interactions with a dominant member of the gut microbiota, and such outcome might be not so rare with this kind of bacteria. Ultravirulent temperate phage mutants might thus be responsible for some of the unexplained variations in bacterial populations in animal experiments.

Despite this very efficient phage infection, bacterial density was not largely affected, and this is due to rapidly acquired resistance by CRISPR-Cas immunity. CRISPR-Cas systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes, but only a small proportion of these systems have been identified to be active in bacteria. Here we demonstrate high efficiency of the minimal type II-C CRISPR-Cas system of R. intestinalis. Considering that among strains acquiring spacers, only those cured of Shimadzu were conserved, and that cured bacteria were about 107 per mice, we can estimate a rate of spacer acquisition above 10−7, similar to that of the best active CRISPR-Cas systems (reviewed in [77]). This high efficiency might be driven by the presence of defective Shimadzu particles, suggested by the discrepancy between Shimadzu PFU and the number of free phage determined by qPCR. Indeed, there is evidence that spacer acquisition occurs most efficiently during the infection by defective viral particles [64]. Yet, interestingly, phage-derived spacer acquisition did not lead to phage extinction. This could result from a high phage mutation rate, enabling to generate escape mutants, but also from the presence of lysogens with an additional Shim-like prophage, that continuously produce free phage.

Interestingly, because the bacteria harbour a prophage closely related to the invading phage, spacer acquisition is highly detrimental, and leads to a kind of suicide. In the case of ultravirulent phage mutants, CRISPR-Cas does not act as a true immunity system, but rather functions as an abortive infection system leading to infected cell death. In the case of R. intestinalis L1-82, a subpopulation of spontaneously cured bacteria, around 5.10−3, is sufficient for phage-derived spacer acquisition and recovery of the bacterial population. However, contrary to Shimadzu, most prophages are almost impossible to cure (our own experience). In some cases, this might be related to the presence of toxin-antitoxin genes, as in the Jekyll prophage of this study, that stabilise the presence of prophages through post-segregational killing [78–81]. In consequence, such subpopulation of cured bacteria does not always exist, probably precluding type II CRISPR-Cas efficiency against superinfection by ultravirulent mutants.

In the present study, resistance to phages conferred by mutations in the bacterial protein used by phage for infection was not observed. This is surprising in the light of studies showing that phage receptor mutations tend to dominate, especially when phage populations are high [82]. The fitness cost of phage receptor mutations, in the case of Shimadzu, may be even higher than the one associated to CRISPR-Cas activity. An alternative explanation could be that such receptor mutants may be systematically countered by Shimadzu escape mutants, thanks to the DGR-mediated high variability of its tail gene, which possibly encodes the receptor-binding protein.

Finally, our study illustrates how a prophage can be a significant source of mortality in bacterial populations. Therefore, prophages could be compared with “genetic time bombs”, meaning that lysogenic bacteria live under the constant threat of superinfection by an ultravirulent mutant. Since phages are known to alter competition among bacterial strains or species [83–86], such evolution could have major effects on the composition of an ecosystem. In particular, Roseburia species are very important in the human gut microbiota, notably due to its large butyrate production, a metabolite with critical role in the regulation of host immune responses [42]. Phage-mediated killing of Roseburia bacteria might therefore participate to the unexplained variations in microbiota composition observed even in defined communities [8–11], which might, in certain conditions, lead to important changes and a rupture of intestinal homoeostasis.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Anne Foussier, Fatima Joly and Aurélie Balvay from Anaxem facility for their help with animal handlings, to Christine Longin from the MIMA2 facilities (INRAE, 10.15454/1.5572348210007727E12) for the TEM observations, to the Migale platform (INRAE, 10.15454/1.5572390655343293E12) for the bio-informatics environment and to Moïra Dion for English language editing. JKC was funded by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FDT20170437017), and mouse experiments were funded by Association François Aupetit.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41396-019-0566-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Yamada T, Mende DR, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–80. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407076101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FW, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK, et al. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchesi JR, Adams DH, Fava F, Hermes GD, Hirschfield GM, Hold G, et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65:330–9. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Darzi Y, Faust K, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science. 2016;352:560–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E, Kurilshikov A, Korem T, Zeevi D, et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature. 2018;555:210–5. doi: 10.1038/nature25973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4578–85. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores GE, Caporaso JG, Henley JB, Rideout JR, Domogala D, Chase J, et al. Temporal variability is a personalized feature of the human microbiome. Genome Biol. 2014;15:531. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0531-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voigt AY, Costea PI, Kultima JR, Li SS, Zeller G, Sunagawa S, et al. Temporal and technical variability of human gut metagenomes. Genome Biol. 2015;16:73. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0639-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarker SA, Berger B, Deng Y, Kieser S, Foata F, Moine D, et al. Oral application of Escherichia coli bacteriophage: safety tests in healthy and diarrheal children from Bangladesh. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:237–50.. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scanlan PD. Bacteria-bacteriophage coevolution in the human gut: implications for microbial diversity and functionality. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:614–23.. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills S, Shanahan F, Stanton C, Hill C, Coffey A, Ross RP. Movers and shakers: influence of bacteriophages in shaping the mammalian gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:4–16. doi: 10.4161/gmic.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Paepe M, Leclerc M, Tinsley CR, Petit MA. Bacteriophages: an underestimated role in human and animal health? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:39. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manrique Pilar, Dills Michael, Young Mark. The Human Gut Phage Community and Its Implications for Health and Disease. Viruses. 2017;9(6):141. doi: 10.3390/v9060141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fania L, Ruggeri S, Sordi D, Oliva A, Provini A, Ricci F, et al. Sweet syndrome following a positive Mantoux test due to pulmonary tuberculosis. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12754. doi: 10.1111/dth.12754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waller AS, Yamada T, Kristensen DM, Kultima JR, Sunagawa S, Koonin EV, et al. Classification and quantification of bacteriophage taxa in human gut metagenomes. ISME J. 2014;8:1391–402. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyes A, Wu M, McNulty NP, Rohwer FL, Gordon JI. Gnotobiotic mouse model of phage-bacterial host dynamics in the human gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20236–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319470110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chibani-Chennoufi S, Sidoti J, Bruttin A, Kutter E, Sarker S, Brussow H. In vitro and in vivo bacteriolytic activities of Escherichia coli phages: implications for phage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2558–69. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2558-2569.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss M, Denou E, Bruttin A, Serra-Moreno R, Dillmann ML, Brussow H. In vivo replication of T4 and T7 bacteriophages in germ-free mice colonized with Escherichia coli. Virology. 2009;393:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maura D, Galtier M, Le Bouguenec C, Debarbieux L. Virulent bacteriophages can target O104:H4 enteroaggregative Escherichia coli in the mouse intestine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:6235–42. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00602-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brussow H. Bacteriophage-host interaction: from splendid isolation into a messy reality. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles B, Silveira CB, Bailey BA, Barott K, Cantu VA, Cobian-Guemes AG, et al. Lytic to temperate switching of viral communities. Nature. 2016;531:466–70. doi: 10.1038/nature17193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Touchon M, Bernheim A, Rocha EP. Genetic and life-history traits associated with the distribution of prophages in bacteria. ISME J. 2016;10:2744–54. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cornuault JK, Petit MA, Mariadassou M, Benevides L, Moncaut E, Langella P, et al. Phages infecting Faecalibacterium prausnitzii belong to novel viral genera that help to decipher intestinal viromes. Microbiome. 2018;6:65. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MSB, Bae JW. Lysogeny is prevalent and widely distributed in the murine gut microbiota. ISME J. 2018;12:1127–41.. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reyes A, Haynes M, Hanson N, Angly FE, Heath AC, Rohwer F, et al. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature. 2010;466:334–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J, Li H, Keilbaugh SA, Wu GD, et al. The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome Res. 2011;21:1616–25.. doi: 10.1101/gr.122705.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahony J, Lugli GA, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Impact of gut-associated bifidobacteria and their phages on health: two sides of the same coin? Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102:2091–9. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berngruber TW, Weissing FJ, Gandon S. Inhibition of superinfection and the evolution of viral latency. J Virol. 2010;84:10200–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00865-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bondy-Denomy J, Davidson AR. When a virus is not a parasite: the beneficial effects of prophages on bacterial fitness. J Microbiol. 2014;52:235–42. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bossi L, Fuentes JA, Mora G, Figueroa-Bossi N. Prophage contribution to bacterial population dynamics. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6467–71. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6467-6471.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown SP, Le Chat L, De Paepe M, Taddei F. Ecology of microbial invasions: amplification allows virus carriers to invade more rapidly when rare. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2048–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duerkop BA, Clements CV, Rollins D, Rodrigues JL, Hooper LV. A composite bacteriophage alters colonization by an intestinal commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17621–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206136109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Paepe M, Tournier L, Moncaut E, Son O, Langella P, Petit MA. Carriage of lambda latent virus is costly for its bacterial host due to frequent reactivation in monoxenic mouse intestine. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selva L, Viana D, Regev-Yochay G, Trzcinski K, Corpa JM, Lasa I, et al. Killing niche competitors by remote-control bacteriophage induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1234–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brum JR, Hurwitz BL, Schofield O, Ducklow HW, Sullivan MB. Seasonal time bombs: dominant temperate viruses affect Southern Ocean microbial dynamics. ISME J. 2016;10:437–49. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucchini S, Desiere F, Brussow H. Comparative genomics of Streptococcus thermophilus phage species supports a modular evolution theory. J Virol. 1999;73:8647–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8647-8656.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimizu-Kadota M, Kiwaki M, Sawaki S, Shirasawa Y, Shibahara-Sone H, Sako T. Insertion of bacteriophage phiFSW into the chromosome of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (S-1): characterization of the attachment sites and the integrase gene. Gene. 2000;249:127–34.. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durmaz E, Miller MJ, Azcarate-Peril MA, Toon SP, Klaenhammer TR. Genome sequence and characteristics of Lrm1, a prophage from industrial Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain M1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4601–9. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00010-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards RA, McNair K, Faust K, Raes J, Dutilh BE. Computational approaches to predict bacteriophage-host relationships. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2016;40:258–72. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rios-Covian D, Ruas-Madiedo P, Margolles A, Gueimonde M, de Los Reyes-Gavilan CG, Salazar N. Intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:185. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tamanai-Shacoori Z, Smida I, Bousarghin L, Loreal O, Meuric V, Fong SB, et al. Roseburia spp.: a marker of health? Future Microbiol. 2017;12:157–70.. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, Andersson AF, Lucio M, Zheng Z, et al. A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1844–54 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milne I, Stephen G, Bayer M, Cock PJ, Pritchard L, Cardle L, Shaw PD, Marshall D. Using Tablet for visual exploration of second-generation sequencing data. Brief Bioinforma. 2013;14:193–202. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Coster W, D'Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:2666–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–36.. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60.. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sierro N, Makita Y, de Hoon M, Nakai K. DBTBS: a database of transcriptional regulation in Bacillus subtilis containing upstream intergenic conservation information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D93–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wattam AR, Davis JJ, Assaf R, Boisvert S, Brettin T, Bun C, et al. Improvements to PATRIC, the all-bacterial bioinformatics database and analysis resource center. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D535–D42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinforma. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, et al. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimmermann L, Stephens A, Nam SZ, Rau D, Kubler J, Lozajic M, et al. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J Mol Biol. 2018;430:2237–43.. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delattre H, Souiai O, Fagoonee K, Guerois R, Petit MA. Phagonaute: a web-based interface for phage synteny browsing and protein function prediction. Virology. 2016;496:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Broussard GW, Oldfield LM, Villanueva VM, Lunt BL, Shine EE, Hatfull GF. Integration-dependent bacteriophage immunity provides insights into the evolution of genetic switches. Mol Cell. 2013;49:237–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lopes A, Tavares P, Petit MA, Guerois R, Zinn-Justin S. Automated classification of tailed bacteriophages according to their neck organization. BMC Genom. 2014;15:1027. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu L, Gingery M, Abebe M, Arambula D, Czornyj E, Handa S, et al. Diversity-generating retroelements: natural variation, classification and evolution inferred from a large-scale genomic survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:11–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Houte S, Buckling A, Westra ER. Evolutionary ecology of prokaryotic immune mechanisms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80:745–63. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hynes AP, Villion M, Moineau S. Adaptation in bacterial CRISPR-Cas immunity can be driven by defective phages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4399. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanjuan R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. Viral mutation rates. J Virol. 2010;84:9733–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00694-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koskella B, Brockhurst MA. Bacteria-phage coevolution as a driver of ecological and evolutionary processes in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:916–31. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berngruber TW, Froissart R, Choisy M, Gandon S. Evolution of virulence in emerging epidemics. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003209. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Capra ML, Mercanti DJ, Rossetti LC, Reinheimer JA, Quiberoni A. Isolation and phenotypic characterization of Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus paracasei bacteriophage-resistant mutants. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111:371–81.. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mercanti DJ, Carminati D, Reinheimer JA, Quiberoni A. Widely distributed lysogeny in probiotic lactobacilli represents a potentially high risk for the fermentative dairy industry. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;144:503–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lenski RE, May RM. The evolution of virulence in parasites and pathogens: reconciliation between two competing hypotheses. J Theor Biol. 1994;169:253–65. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]