Graphical Abstract

A HPLC-MS method had been developed and applied to investigate the influence of pretreatment of piperazine ferulate on pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate. The changes in the pharmacokinetic behavior indicated that the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate might exert the protective effect on methotrexate-induced renal injury.

Keywords: Methotrexate, Piperazine ferulate, Pharmacokinetic parameters, HPLC-MS

Abstract

The present study was designed to investigate the influence of the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate on pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate in methotrexate-induced renal injury rats. A simple and efficient high performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) method was developed to determine methotrexate in rat plasma. Methotrexate and syringic acid (internal standard) were extracted from rat plasma samples by protein precipitation with acetonitrile. The analysis was performed on a CAPCELL PAK C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) with acetonitrile and 5 mmol/l ammonium acetate aqueous (10:90, v/v). The linear range was 5.0 × 10−2 to 100.0 µg/ml for methotrexate. Other parameters were all within the acceptance criteria. The validated method was successfully applied the pharmacokinetic study of methotrexate between two methotrexate treated groups (with and without the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate). Compared with the methotrexate treated alone group, the pharmacokinetic parameters in the methotrexate with the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate group showed significantly lower MRT(0-t), MRT(0-∞) and T1/2. Results suggested that methotrexate can be rapidly eliminated, cleared or metabolized in rat blood, which might be related to the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate. The method provided deeper insights into rational clinical use of methotrexate with the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate on cancer patients with renal dysfunction.

1. Introduction

As a dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor, methotrexate has been widely used to treat cancer [1], [2], [3]. However, nonoliguric and oligoanuric acute renal failure has been reported following administration of low- or high-dose methotrexate in many clinical cases [4], [5], [6], [7], which is a major limiting factor in clinical therapy. Some regimens, such as folic acid or leucovorin, were reported during treatment with methotrexate, so as to relieve the toxicity induced by methotrexate in the clinical therapy [8], [9]. However, it was supposed that folic acid supplementation may cause a reduction in efficacy of methotrexate [10]. Meanwhile, leucovorin may result in the delayed clearance of methotrexate and this incidence can be higher in older patients and during the first cycles of treatment [11]. Renal dysfunction is a common occurrence in patients with gynecologic cancer [12], metastatic renal cell carcinoma and other kinds of caner [13]. Renal impairment is especially frequent in elderly patients with cancer [14]. Thus, it is meaningful to find renal protective regimens when using methotrexate to treat cancer patients with kidney injury.

Piperazine ferulate is the substrate in the extract of Traditional Chinese Medicine – ligustrazine, which has been widely used in clinical practice in China to treat patients with chronic glomerulonephritis [15]. Piperazine ferulate can partly inhibit the synthesis of extracellular matrix and connective tissue growth factor in rat glomerular mesangial cells, and may be in connection with the prevention of glomerulosclerosis [16]. So piperazine ferulate may attenuate the potential renal injury caused by methotrexate. Although piperazine ferulate is believed to have the effects on improving renal functions [16], [17], [18], there is little study about the influence of pretreatment of piperazine ferulate on pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate in rats, and that was the reason why piperazine ferulate was chosen in this study.

Pharmacokinetics is reported to be a useful proof to reveal the reasonable drug compatibility in combination treatment [19], [20], [21]. In this study, pharmacokinetics had been used to assess the influence of piperazine ferulate on pharmacokinetics profile of methotrexate with HPLC-MS method. Although there were other advanced analytical methods to quantitatively determine methotrexate [22], [23], [24], this HPLC-MS method possessed the property of being easy to operate with high recovery, accuracy and precision. The pharmacokinetic results were expected to be useful for improving clinical use of methotrexate through the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate.

Renal histopathology was conducted to evaluate the renal failure induced by methotrexate. The histopathological differences between methotrexate with and without the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate groups could be regarded as another evidence of clinical application of methotrexate with the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Methotrexate and physiological saline (0.9%) were purchased from Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co., Ltd (Jiangsu, China) and Cologne Heilongjiang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Heilongjiang, China), respectively. Piperazine ferulate tablets were supplied by Shandong Hill Kangtai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Shandong, China). The reference standards of methotrexate and syringic acid (IS, purity >98.0%) (Fig. 1) were both obtained from Aladdin Ltd (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile and methanol (HPLC grade) were provided by Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA), and ammonium acetate was supplied by Kermel Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Tianjin, China). Distilled water was provided by Wahaha Co., Ltd (Hangzhou, China). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of methotrexate (A) and IS (B).

2.2. Animals

In this study, all male Sprague-Dawley rats (220–250 g) were kindly provided by Experimental Animal Center of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University and bred with unlimited access to food and water in an air-conditioned animal center at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 50 ± 10%, with a natural light-dark cycle for 3 days. Before the drug administration, they were fasted overnight with free access to water. Animal study was carried out following the Guidelines of Animal Experimentation of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University, and the protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the institution.

Six rats were randomly divided into two groups (3 rats per group) for histopathology study: methotrexate treated alone group (Group A1) and piperazine ferulate pretreated group (Group B1). Rats in Group B1 and Group A1 were orally given piperazine ferulate (at 50 mg/kg/d) and physiological saline (the same volume of vehicle) for 14 days, respectively. Then all rats were given intravenous injection of methotrexate at a dosage of 50 mg/kg at 14th day. At the end of the histopathology period, rats were sacrificed. Kidney tissues were immediately dissected out and preserved in neutral buffered formalin. Kidney samples were sliced to 3 µm wax sections, and the tissuesections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) dye for microscopic examinations after gradual rehydration in a series of graded alcohols.

After histopathology having evaluated the renal injury model, 12 rats were randomly divided into two groups (6 rats per group): methotrexate treated alone group (Group A2) and piperazine ferulate pretreated group (Group B2). The treatment of rats in Groups A2 and B2 was performed according to the treatment in Groups A1 and B1, respectively. The blood samples (approx. 0.3 ml) were collected from the suborbital vein into heparinized tubes before injection and 0.083, 0.167, 0.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24 h after dosing, then immediately centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The plasma samples were stored at −80 °C for two weeks until HPLC-MS analysis.

2.3. Instrumentation and analytical conditions

The assay was performed on a Shimadzu (Japan, Kyoto) HPLC-MS 2010EA system. The HPLC separation was performed on a CAPCELL PAK C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) and preceded by a C18 guard column (4.0 mm × 2.0 mm, 5 µm) with the mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile and 5 mmol/l ammonium acetate aqueous (10:90, v/v). The flow rate was set at 0.8 ml/min with 25% of the eluent split into the inlet of the mass spectrometer. The injection volume was 10 µl and the total analysis time was 6.0 min for each run. Mass data were acquired using a mono-quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with an electrospray ionization source (ESI) in the negative ion mode under the following optimized parameters and conditions: nebulizing gas 1.5 l/min, drying gas 2.0 l/min, curved desolvation line temperature 200 °C, heat block temperature 200 °C, detector voltage 1.75 kV, the other parameters were fixed as for the tuning file. Analysis was conducted in selected ion monitoring mode (SIM) at m/z 453.1 [M-H]- for methotrexate and m/z 197.1 [M-H]- for IS, respectively.

2.4. Standard solutions, calibration curves and quality control (QC) samples

Methotrexate stock solution (1.0 mg/ml) was prepared in water with a certain amount of sodium carbonate aqueous solution (0.2 mol/l), while IS stock solution (1.0 mg/ml) was prepared in methanol. Methotrexate stock solution was further diluted to obtain standard working solutions with water. IS was diluted to a concentration of 40.0 µg/ml with methanol as working solution. All solutions were store at 4 °C and were brought to room temperature before use.

Calibration standards of methotrexate (5.0 × 10−2, 5.0 × 10−1, 2.0, 5.0, 25.0, 50.0, 100.0 µg/ml) were prepared by adding 20 µl of single standard working solution and 20 µl of IS to blank rat plasma. The lowest limits of quantification, low, medium, high quality control (QC) samples were prepared at concentrations of 5.0 × 10−2, 1.0 × 10−1, 4.0 and 80.0 µg/ml for methotrexate.

2.5. Sample preparation

All frozen samples, calibration standards and QC samples were thawed and to equilibrate at room temperature prior to analysis. An aliquot of 100 µl plasma sample was spiked with 20 µl of IS working solution and 20 µl of water, and vortex-mixed for 30 s, then the mixture was deproteinized with 200 µl of acetonitrile by vortex-mixing for 5 min. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, the upper organic layer was transferred to another centrifuge tube and evaporated to dryness under a gentle steam of nitrogen. The residue was redissolved with 100 µl of initial mobile phase, of which 10 µl aliquot was injected into HPLC-MS system.

2.6. Method validation

The selectivity was evaluated by comparing chromatograms of blank plasma from six different rats, blank plasma spiked with methotrexate and IS, and plasma sample at 0.5 h after intravenous injection of methotrexate.

The linearity of the assay was assessed by analyzing the calibration curve for methotrexate over the concentration range (5.0 × 10−2 to 100.0 µg/ml) using least-squares linear regression of the analyte/IS peak area ratios versus the normalized standard concentration with a weighed (1/x2) factor.

The inter-day and intra-day precisions of the method were assessed by six replicates of each QC sample on three consecutive analytical days and three different days. The accuracy was determined by comparing each calculated QC sample with the theoretical. Precision was defined as the relative standard deviation (RSD%), while accuracy was defined as relative error (RE%). Six individual LLOQ samples were prepared to achieve the acceptable accuracy within ±20% and the precision below 20%.

The recovery of methotrexate was determined at three QC levels with six replicates by comparing the peak areas from extracted samples with those in post-extracted blank plasma samples spiked with methotrexate at the same concentration. The recovery of IS was determined in the same way.

The matrix effect was measured by comparing the peak responses of post-extraction spiked blank samples with standard solutions containing equivalent amounts of the compound of methotrexate.

Long-term stability (−80 °C for 14 days), short-term stability (room temperature for 24 h) and freeze (−80 °C)-thaw (room temperature) circle (three times) were selected to evaluate the stability of methotrexate.

2.7. Plasma pharmacokinetics and data analysis

Pharmacokinetic data for methotrexate were calculated by non-compartmental analysis of plasma concentration versus time data using the DAS 2.0 software package (Chinese Pharmacological Society). Statistical analysis comparisons of AUC, MRT, T1/2 and CLz between two groups were performed by use of SPSS 17.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Science) using independent samples t-tests after their natural logarithmic transformation or the nonparametric test. The data are presented as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant for all the tests.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Histopathology

The kidney tissue specimens are presented in Fig. 2, which demonstrate that many abnormal morphological changes were observed in Group A1, including glomerular compensatory swelling, glomerular atrophy and tubular cloudy swelling. No obvious abnormalities were found in Group B1 when observing glomeruli and tubules.

Fig. 2.

Representative histopathological photographs of SD rat kidney sections (100×). (A) Group A1; (B) Group B1.

3.2. Optimization of LC-MS conditions and sample preparation

To optimize ESI conditions for detection of methotrexate, both negative and positive ion modes had been tested. Negative ion mode was chosen, for it was more sensitive for methotrexate and IS analysis.

In order to increase signal response of methotrexate and IS, several mobile phases (methanol and acetonitrile) and other additives (5 mmol/l and 10 mmol/l ammonium acetate) were tested. As a result, acetonitrile and 5 mmol/l ammonium acetate in the aqueous phase could minimize background noise and the risk of ion suppression, as well as improve the peak shape of analytes.

Both liquid–liquid extraction and protein precipitation were investigated in order to avoid matrix suppression and interference from endogenous plasma components. Initially, ethyl acetate and isopropanol-ethyl acetate were tested. However, neither of them was found to give satisfactory and consistent recovery for analytes. Therefore, protein precipitation method was evaluated in this study, and the addition of 200 µl of acetonitrile into 100 µl of plasma was indicated to be with high recoveries for methotrexate and IS.

3.3. Method validation

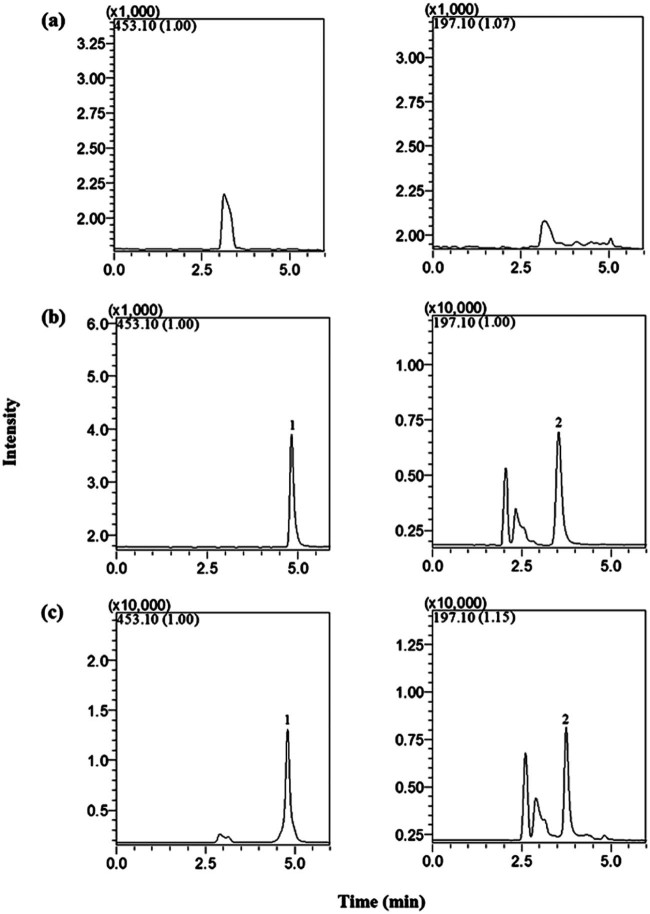

The retention times of methotrexate and IS were 3.63 and 4.92 min, respectively. No significant interference from endogenous substances was observed at the retention times of methotrexate and IS. Fig. 3 shows the representative chromatograms obtained from the methotrexate of blank plasma, plasma spiked with methotrexate and plasma samples obtained at 0.5 h after intravenous injection.

Fig. 3.

SIM chromatograms obtained from blank rat plasma (a), blank rat plasma spiked with methotrexate (0.8 µg/ml) and IS (b) and rat plasma at 0.5 h after intravenous injection of methotrexate (c). 1, methotrexate; 2, IS.

The calibration curves of methotrexate in rat plasma were analyzed. The typical calibration curve for methotrexate was y = 0.1223x + 0.0887, and it showed good linearity over the concentration range of 5.0 × 10−2 to 100.0 µg/ml in rat plasma. The coefficient of correlation (r2) was 0.9997. The LLOQ (5.0 × 10−2 µg/ml) was the lowest concentration on the calibration curve. The precision and accuracy at LLOQ for methotrexate were within ±20%.

The intra- and inter-day precisions were less than 6.5% and 7.1% (RSD%). And the accuracies were within ±7.8 (RE%). The data of the assay are summarized in Table 1, indicating that the developed method is accurate and reliable.

Table 1.

Precision, accuracy, recovery and matrix effect of methotrexate determination in rat plasma (n = 6).

| Spiked concentration (µg/ml) | Precision | Accuracy (RE%) | Extraction recovery (%) | Matrix effect (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day (RSD%) | Inter-day (RSD%) | |||||

| Methotrexate | 1.0 × 10−1 | 6.5 | 7.1 | −7.8 | 82.5 ± 6.9 | 92.3 ± 4.5 |

| 4.0 | 3.4 | 4.2 | −4.7 | 86.3 ± 3.7 | 88.7 ± 4.8 | |

| 80.0 | 2.1 | 2.7 | −1.5 | 85.2 ± 4.6 | 93.6 ± 5.3 | |

The extraction recoveries of methotrexate at three QC concentrations were 82.5–86.3% (Table 1), which indicated that the extraction method was consistent and repeatable. The results of matrix effect of methotrexate were 88.7–93.6%, indicating that no-eluting endogenous substances significantly influenced the ionization for methotrexate in this analytical method. The mean extraction recovery and matrix effect of IS were 83.3% and 98.5%, respectively.

The stability of methotrexate under various conditions is listed in Table 2. The consistent results indicated that methotrexate was stable under all tested conditions. All results were within the acceptance criteria of ±9.2% deviation from the nominal concentration.

Table 2.

Stability of methotrexate in rat plasma (n = 3).

| Spiked concentration (µg/ml) | Three freeze–thaw cycles stability | 24 h at room temperature | Stability for 14 d at −80 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE% | RSD% | RE% | RSD% | RE% | RSD% | ||

| Methotrexate | 1.0 × 10−1 | −9.2 | 6.8 | −6.4 | 7.2 | −3.5 | 4.1 |

| 4.0 | −4.8 | 5.9 | −4.4 | 4.5 | −5.2 | 6.3 | |

| 80.0 | −3.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 3.8 | −1.7 | 3.5 | |

3.4. Pharmacokinetics

The method described above was successfully applied to a comparative pharmacokinetic study of methotrexate with and without piperazine ferulate. The mean plasma concentration time profiles of methotrexate in two groups are shown in Fig. 4. And the corresponding pharmacokinetic parameters are listed in Table 3.

Fig. 4.

The mean concentration–time curves of methotrexate in Group A2 and Group B2 rat plasma. The blood was received at different time (from 0 to 24 h). Each point represents mean ± SD.

Table 3.

The toxicokinetic parameters of methotrexate after intravenous injection in Group A2 and Group B2 rats.

| Data | Unit | Group A2 | Group B2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC(0-t) | µg⋅h/ml | 36.41 ± 11.98 | 28.09 ± 8.57 |

| AUC(0-∞) | µg⋅h/ml | 36.47 ± 12.03 | 28.18 ± 8.52 |

| MRT(0-t) | h | 1.01 ± 0.28 | 0.57 ± 0.16* |

| MRT(0-∞) | h | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 0.65 ± 0.15* |

| T1/2 | h | 4.56 ± 0.87 | 3.09 ± 0.79* |

| CLz | l/h/kg | 63.05 ± 30.94 | 76.50 ± 22.33 |

P < 0.05 compared with Group A2 rats. Mean ± SD, n = 6.

In accordance with the results of histopathology, the results in Table 3 demonstrate that there were significant differences on some parameters (P < 0.05) between two groups. Compared with Group A2, MRT(0-t), MRT(0-∞) and T1/2 of methotrexate significantly decreased in Group B2. With the obtained pharmacokinetic results, it can be concluded that pretreatment of piperazine ferulate can affect the pharmacokinetic profiles of methotrexate, which might indicate that protective piperazine ferulate could attenuate the renal failure caused by methotrexate.

Methotrexate in high dose range (>50 mg/kg) is usually used to treat cancer [25], [26], [27]. According to the histopathology and the previous studies [28], [29], the dose of methotrexate (50 mg/kg) showed obvious nephrotoxicity in rats, thus this dose was chosen in this study. Reports demonstrated that the dose of piperazine ferulate (10 mg/d) was shown to have protective effects on renal injury [17]. Taking the mean weight of rats and the dose of methotrexate into consideration, 50 mg/kg/d was used as the dose of piperazine ferulate.

The results of histopathological changes suggested that the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate might display the protective effect in this study. Meanwhile, it was supposed that piperazine ferulate could reduce proteinuria and erythrocyturia effectively in the treatment of primary chronic glomerulonephritis [16], which was one of the most common causes ofend-stage renal disease among chronic kidney diseases [30]. Therefore, in the comparative pharmacokinetic study, Group A2 (methotrexate treated alone group) and Group B2 (piperazine ferulate pretreated group) were developed to investigate whether pretreatment of piperazine ferulate could change the pharmacokinetic behaviors of methotrexate.

It was reported that piperazine ferulate had effects on anticoagulant, anti-platelet aggregation, the expansion of capillaries, the increase in coronary blood flow and the relief of spasm [17]. Thus, the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate might posses the ability to accelerate the transformation rates of methotrexate from blood to tissues, which could lead to the significant decreases of MRT(0-t) (P < 0.05) and MRT(0-∞) (P < 0.05) in Group B2 when compared with those in Group A2. Moreover, the above effects of piperazine ferulate could also improve the renal blood flow, then result in the quicker metabolism and excretion of methotrexate. It might be the reason for the reduced AUC (although not significant) in Group B2 when compared with that in Group A2.

More than 90% of methotrexate is believed to be cleared by kidneys [31]. The precipitation of methotrexate in the renal tubules and the direct toxic effect of methotrexate on the renal tubules were supposed to be the important reasons for methotrexate-induced renal dysfunction [32], [33]. Based on the previous research [16], [17], piperazine ferulate might inhibit fibrosis in the renal fibroblast, and take part in the prevention of glomerulosclerosis, which might result in the acceleration of the metabolism and elimination of methotrexate. Since metabolism and elimination were considered relevant to T1/2 and CLz, the decrease of T1/2 (P < 0.05) and CLz (although P > 0.05) in Group B2 could be interrupted under the condition of the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate when compared with those in Group A2.

In summary, the results of the comparative pharmacokinetic study suggested that the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate significantly decreased MRT(0-t) (P < 0.05), MRT(0-∞) (P < 0.05) and T1/2 (P < 0.05), and reduced AUC, CLz of methotrexate, but not significantly. The result indicated that the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate could lead to less damages of the organism caused by methotrexate, which were in accordance with the histopathological changes, which was meaningful for clinical use of methotrexate with pretreatment of piperazine ferulate in cancer therapy.

4. Conclusion

A simple and sensitive HPLC-MS method had been developed and was successfully applied to investigate the influence of pretreatment of piperazine ferulate on pharmacokinetic parameters of methotrexate. In accordance with the histopathological result, the changes in the pharmacokinetic behavior indicated that the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate might exert the protective effect on methotrexate-induced renal injury. The result could be expected to be helpful in improving clinical use of methotrexate through the pretreatment of piperazine ferulate, especially in caner patients with renal dysfunction.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shenyang Pharmaceutical University.

Contributor Information

Longshan Zhao, Email: longshanzhao@163.com.

Xiaohui Chen, Email: cxh_syphu@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Lukenbill J., Advani A.S. The treatment of adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig R. 2013;8:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s11899-013-0159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luetke A., Meyers P.A., Lewis I. Osteosarcoma treatment – where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg C.N., Donat S.M., Bellmunt J. Chemotherapy for bladder cancer: treatment guidelines for neoadjuvant chemotherapy, bladder preservation, adjuvant chemotherapy, and metastatic cancer. Urology. 2007;69:62–79. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widemann B.C., Adamson P.C. Understanding and managing methotrexate nephrotoxicity. Oncologist. 2006;11:694–703. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widemann B.C., Balis F.M., Kempf-Bielack B. High-dose methotrexate-induced nephrotoxicity in patients with osteosarcoma – incidence, treatment, and outcome. Cancer. 2004;100:2222–2232. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari S., Smeland S., Mercuri M. Chemotherapy with high-dose ifosfamide, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: a joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian sarcoma groups. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8845–8852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivity S., Zafrir Y., Loebstein R. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1109–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauthier H.P., Guilhaume M.N., Bidard F.C. Survival of breast cancers patients with meningeal carcinoma. B Cancer. 2011;98:391–398. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2011.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan S.L., Baggott J.E., Vaughn W.H. The effect of folic acid supplementation on the toxicity of low-dose methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum-us. 1990;33:9–18. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Dabagh A., Davis S.A., Kinney M.A. The effect of folate supplementation on methotrexate efficacy and toxicity in psoriasis patients and folic acid use by dermatologists in the USA. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacci G., Ferrari S., Longhi A. Delayed methotrexate clearance in osteosarcoma patients treated with multiagent regimens of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:851–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y.F., Finkel K.W., Hu W. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin treatment in recurrent gynecologic cancer patients with renal dysfunction. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S., Parsa V., Heilbrun L.K. Safety and efficacy of molecularly targeted agents in patients with metastatic kidney cancer with renal dysfunction. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:794–800. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328346af0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aapro M., Launay-Vacher V. Importance of monitoring renal function in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang B., Ni Q., Wang X. Meta-analysis of the clinical effect of ligustrazine on diabetic nephropathy. Am J Chinese Med. 2012;40:25–27. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X12500036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu H.Y., Fan W.X., Fu P. General acteoside of rehmanniae leaves in the treatment of primary chronic glomerulonephritis: a randomized controlled trial. Afr. J. Tradit Complem. 2013;10:109–115. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i4.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng W.Z., Li Z.H. Protective effect and the mechanism of action of piperazine ferulate on diabetic glomerulopathy in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Chinese Journal of Hospital Pharmacy. 2003;23:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S.J., Gu Y., Yang H.C. Renoprotective effects of piperazine ferulate on rats with nephritic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:345A. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meilis N., Harahap Y., Saputri F.C. Pharmacokinetic interaction between irbesartan and Orthosiphon stamineus extract in rat plasma. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2016;11:70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kan S.L., Li J., Liu J.P. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics relationships for Salvianolic Acid B micro-porous osmotic pump pellets in angina pectoris rabbit. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2014;9:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto Y., Taguchi K., Yamasaki K. Effect of PEGylation on the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic characteristics of bovine serum albumin-encapsulated liposome. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2016;11:112–113. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouquie R., Deslandes G., Bernaldez B.N. A fast LC-MS/MS assay for methotrexate monitoring in plasma: validation, comparison to FPIA and application in the setting of carboxypeptidase therapy. Anal Methods-UK. 2014;6:178–186. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodin I., Braun A., Stavrianidi A. A validated LC–MS/MS method for rapid determination of methotrexate in human saliva and its application to an excretion evaluation study. J Chromatogr B. 2013;937:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganti V., Walker E.A., Nagar S. Pharmacokinetic application of a bio-analytical LC-MS method developed for 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate in mouse plasma, brain and urine. Biomed Chromatogr. 2013;27:994–1002. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ackland S.P., Schilsky R.L. High-dose methotrexate: a critical reappraisal. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:2017–2031. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.12.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frei E., Blum R.H., Pitman S.W. High dose methotrexate with leucovorin rescue. Rationale and spectrum of antitumor activity. Am J Med. 1980;68:370–376. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Djerassi I. High-dose methotrexate (NSC-740) and citrovorum factor (NSC-3590) rescue: background and rationale. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1975;6:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kintzel P.E. Anticancer drug-induced kidney disorders. Drug Saf. 2001;24:19–38. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perazella M.A. Crystal-induced acute renal failure. Am J Med. 1999;106:459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L.X., Wang F., Wang L. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;379:815–822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bleyer W.A. The clinical pharmacology of methotrexate: new applications of an old drug. Cancer. 1978;41:36–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197801)41:1<36::aid-cncr2820410108>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobs S.A., Stoller R.G., Chabner B.A. 7-Hydroxymethotrexate as a urinary metabolite in human subjects and rhesus monkeys receiving high dose methotrexate. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:534–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI108308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lankelma J., van der Klein E., Ramaekers F. The role of 7-hydroxymethotrexate during methotrexate anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 1980;9:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(80)90117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]