Abstract

Although active constituents extracted from plants show robust in vitro pharmacological effects, low in vivo absorption greatly limits the widespread application of these compounds. A strategy of using phyto-phospholipid complexes represents a promising approach to increase the oral bioavailability of active constituents, which is consist of ‘‘label-friendly” phospholipids and active constituents. Hydrogen bond interactions between active constituents and phospholipids enable phospholipid complexes as an integral part. This review provides an update on four important issues related to phyto-phospholipid complexes: active constituents, phospholipids, solvents, and stoichiometric ratios. We also discuss recent progress in research on the preparation, characterization, structural verification, and increased bioavailability of phyto-phospholipid complexes.

Keywords: Phyto-phospholipid complexes, Active constituents, Hydrogen bonds, Bioavailability

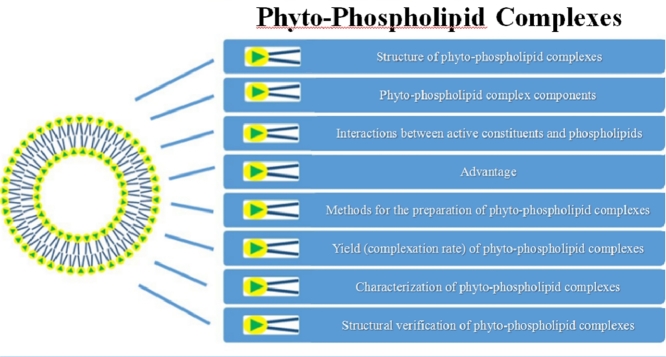

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Active constituents extracted from plants have been used to treat various diseases since ancient times [1], [2]. Silybin extracted from milk thistle fruit has been used to provide liver support for 2000 years [3]. Curcumins extracted from turmeric have been reported to exhibit antioxidant and anticancer properties [4], [5]. Moreover, some of the most widely studied active constituents are polyphenols, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolics [6], [7]. However, many active constituents extracted from plants are poorly absorbed when administered orally, which limits their widespread application [8], [9]. The poor absorption of these compounds results from two properties. First, the multi-ring structures of polyphenols are too large to be absorbed by passive diffusion or non-active absorption. Second, the poor water or lipid solubility of these compounds prevents them from passing across the outer membrane of gastrointestinal cells [10], [11].

Active constituents extracted from natural plants have been shown to exhibit robust in vitro pharmacological effects, but poor in vivo absorption. A variety of solutions have been proposed to counter the problem of poor absorption [12], such as the preparation of emulsions [13], liposomes [14], and nanoparticles [15], as well as the modification of chemical structures [16] and delivery as prodrugs [17]. Among the potential strategies, phyto-phospholipid complexes (known as phytosomes) have emerged as a promising strategy to enhance the bioavailability of active constituents [11]. Phyto-phospholipid complexes are prepared by complexing active constituents at defined molar ratios with phospholipids under certain conditions [18]. Amphipathic phospholipids mainly act as “ushers” of active constituents to help them pass through the outer membrane of gastrointestinal cells, eventually reaching the blood [11]. After forming phospholipid complexes, the membrane permeability and oil–water partition coefficient of constituents are greatly improved. Thus, phyto-phospholipid complexes are more readily absorbed and generate higher bioavailability compared to free active constituents [19], [20]. Encouragingly, the technique of phospholipid complexes has overcome the obstacle of poor bioavailability for many active constituents [21], [22].

Therefore, the preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes has recently received increased attention [23]. Based on the literature, we review various aspects of phyto-phospholipid complexes, including interactions, structures, characterization, structural verification, and increased bioavailability. We also highlight recent advances in the types of active constituents, phospholipids, solvents, and stoichiometric ratios.

2. Structure of phyto-phospholipid complexes

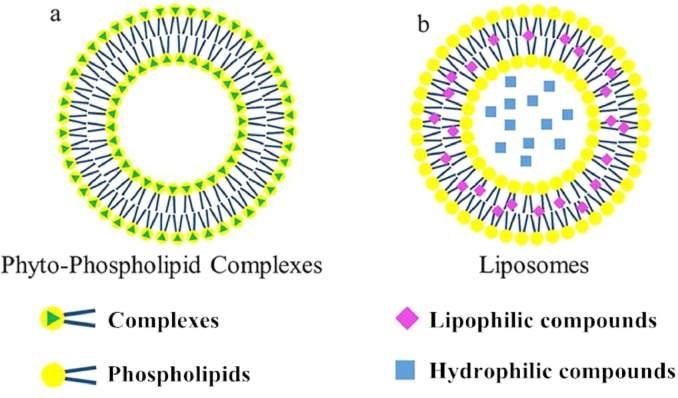

Phyto-phospholipid complexes are formed by interactions between active constituents and the polar head of phospholipids [23]. Interactions between active constituents and phospholipids enable phospholipid complexes to be an integral part in which the phospholipids head group is anchored, but the two long fatty acid chains do not participate in complex formation. The two long fatty acid chains can move and encapsulate the polar part of complexes to form a lipophilic surface. Phyto-phospholipid complexes form agglomerates when diluted in water, which resemble a small cell that shows some similarity to liposomes; the differences between liposomes and complexes are shown in Fig. 1 [24]. As can be seen from Fig. 1, the biggest difference between phytosomes and liposomes is that, in liposomes, the active ingredient is distributed in the medium contained the cavity or in the layers of the membrane, whereas in phytosomes, it is an integral part of the membrane, being the molecules stabled through hydrogen bonds to the polar head of the phospholipids.

Fig. 1.

Structure of phyto-phospholipid complexes and liposomes.

Liposomes are closed vesicles formed by lipid bilayers that can encapsulate compounds within an aqueous compartment or multiple lipid bilayers, but do not mix with compounds [25].

3. Phyto-phospholipid complex components

Bombardelli proposed that phyto-phospholipid complexes can be created from the reaction of phospholipids at a stoichiometric ratio with active constituents that are extracted from plants [26]. Based on subsequent studies, this initial description of phyto-phospholipid complexes has been challenged. According to the literature, we have proposed an updated list of the four essential components needed: phospholipids, phyto-active constituents, solvents, and the stoichiometric ratio involved in the formation of phyto-phospholipid complexes [24].

3.1. Phospholipids

Phospholipids are abundant in egg yolk and plant seeds. Currently, industrially produced phospholipids are available [24]. Phospholipids can be divided into glycerophospholipids and sphingomyelins depending on the backbone. Additionally, glycerophospholipids include phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and phosphatidylglycerol (PG) [27].

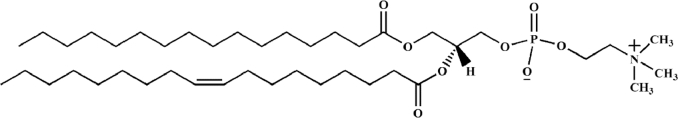

PC, PE, and PS are the major phospholipids used to prepare complexes that are composed of a hydrophilic head group and two hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains [28]. Among these phospholipids, PC is the most frequently used to prepare phospholipid complexes. The structure of the PC is as follows (Fig. 2). The benefits of PC include its amphipathic properties that give it moderate solubility in water and lipid media. Moreover, PC is an essential component of cell membranes, and accordingly it exhibits robust biocompatibility and low toxicity. PC molecules exhibit hepatoprotective activities, and have been reported to show clinical effects in the treatment of liver diseases, such as hepatitis, fatty liver, and hepatocirrhosis [11], [29]. Patel et al. prepared high-affinity small molecule-phospholipid complexes of siramesine and PA [33]. To date, the use of PG and PI to prepare phospholipid complexes has not yet been reported.

Fig. 2.

Structure of phosphatidylcholine (PC).

3.2. Phyto-active constituents

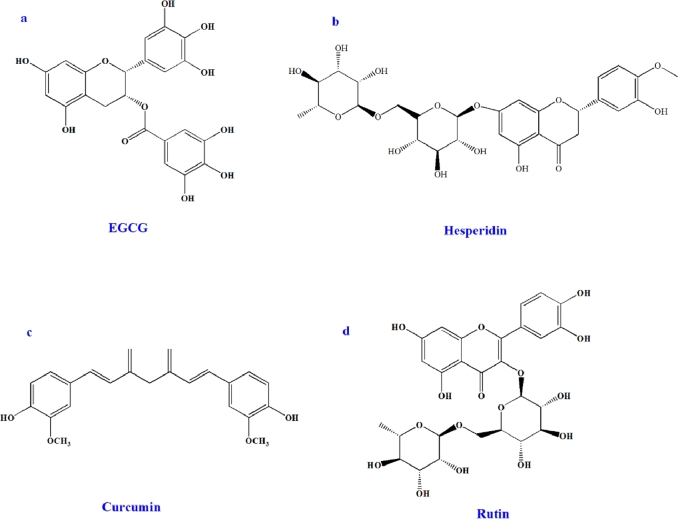

The active constituents of herbal extracts identified by researchers are generally defined based on robust in vitro pharmacological effects, rather than on in vivo activities. Most of these compounds are polyphenols. Some of the polyphenols structural drugs are shown below (Fig. 3). Some of the biologically active polyphenolic constituents of plants show affinity for the aqueous phase and cannot pass through biological membranes, such as hesperidin. By contrast, others have high lipophilic properties and cannot dissolve in aqueous gastrointestinal fluids, such as curcumin and rutin. Phyto-phospholipid complexes cannot only improve the solubility of lipophilic polyphenols in aqueous phase but also the membrane penetrability of hydrophilic ones from aqueous phase. Furthermore, the production of complexes can protect polyphenols from destruction by external forces, such as hydrolysis, photolysis, and oxidation [2].

Fig. 3.

Structure of selected polyphenols: (a) EGCG, (b) Hesperidin, (c) Curcumin, and (d) Rutin.

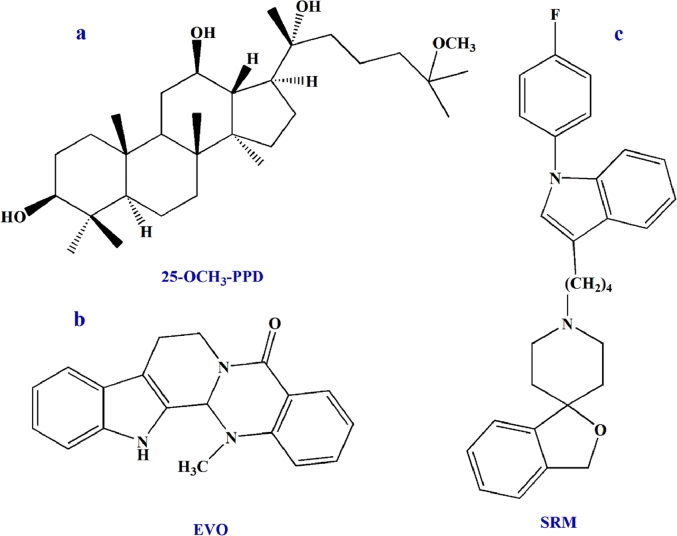

Apart from polyphenols, other molecules from herbal extracts can also be prepared in complexes with phospholipids, such as 20(R)-25-methoxyl-dammarane-3β,12β,20-triol (25-OCH3-PPD) [30], evodiamine (EVO) [31], and siramesine (SRM) [32] (Fig. 4). Therefore, phyto-phospholipid complexes are no longer limited to polyphenols and, in theory, the strategy of generated complexes is suitable for any active molecule [2].

Fig. 4.

Structure of (a) 25-OCH3-PPD, (b) EVO, and (c) SRM.

More phyto-phospholipid complexes on the market are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Therapeutic applications of different phyto-phospholipid complexes on the market [33], [34], [35], [36], [37].

| S. no. | Trade name | Phytoconstituents complex | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Greenselct® phytosome | Epigallocatechin 3-O-gallate from camelia sinensis (green tea) | Systemic antioxidant. Protect against cancer and damage to cholesterol. |

| 2. | Ginkgoselect® phytosome | Ginkgo flavono glycosides from Ginkgo biloba | Protects brain and vascular lining. |

| 3. | Silybin phytosome | Silybin from silymarin | Provides antioxidant protection for the liver and skin. |

| 4. | Glycyrrhiza phytosome | 18-beta glycyrrhetinic acid | Anti-inflammatory activity |

| 5. | Grape seed (Leucoselect) phytosome | Procyanidins from vitis Vinifera | Anti-oxidant, anticancer |

| 6. | Curcumin (Merinoselect) phytosomes | Polyphenol from Curcuma Longa | Cancer chemo preventive agent improving the oral bioavailability of curcuminoids, and the plasma. |

| 7. | OleaselectTM phytosome | Polyphenols from olive oil | Inhibit harmful oxidation of LDL cholesterol, and provides an anti-inflammatory effect. |

| 8. | Sabalselect® phytosome | An extract of saw palmet to berries through supercritical CO2 (carbondioxide) extraction | It is beneficial to the normal functioning of the prostate |

| 9. | PA2 phytosome horse Chestnut bark | Proanthocyanidin A2 from | Anti-wrinkles, UV protectant |

| 10. | Zanthalene phytosome | Zanthalene from zanthoxylum bungeanum | Soothing, anti-irritant, anti-itching |

| 11. | Centella phytosome | Terpenes | Vein and skin disorders |

| 12. | Hawthorn phytosomeTM | Flavonoids from Crataegus sp. | Nutraceutical, cardio‐protective and antihypertensive |

3.3. Solvents

Different solvents have been utilized by different researchers as the reaction medium for formulating phyto-phospholipid complexes. Traditionally, aprotic solvents, such as aromatic hydrocarbons, halogen derivatives, methylene chloride, ethyl acetate, or cyclic ethers etc. have been used to prepare phyto-phospholipid complexes but they have been largely replaced by protic solvents like ethanol [23], [38]. Indeed, protonic solvents, such as ethanol and methanol, have been more recently been successfully utilized to prepare phospholipid complexes. For example, Xiao prepared silybin-phospholipid complexes using ethanol as a protonic solvent; subsequently, the protonic solvent was removed under vacuum at 40°C [22].

Various types of solvents have been successfully studied. When the yield of phospholipid complexes is sufficiently high, ethanol can be a useful and popular solvent that leaves less residue residual and causes minimal damage. Some liposomal drug complexes operate in the presence of water or buffer solution, where the phytosomes interact with a solvent with a reduced dielectric constant [33].

Recently, many studies have used the supercritical fluid (SCF) process to control the size, shape, and morphology of the material of interest. Supercritical anti solvent process (SAS) is one of the SCF technologies that are becoming a promising technique to produce micronic and submicronic particles with controlled size and size distribution [39]. In this technique, a supercritical fluid (usually CO2) will be chosen as an anti-solvent to reduce the solute's solubility in the solvent.

3.4. Stoichiometric ratio of active constituents and phospholipids

Normally, phyto-phospholipid complexes are enployed by reacting a synthetic or natural phospholipid with the active constituents in a molar ratio ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 [40]. Whereas, a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 is considered to be the most efficient ratio for preparing phospholipid complexes [41]. For example, quercetin-phospholipid complexes were prepared by mixing Lipoid S 100 and quercetin at a molar ratio of 1:1 [42]. However, different stoichiometric ratios of active constituents and phospholipids have been used. Maryana et al. prepared silymarin-phospholipid complexes with different stoichiometric ratios of 1:5, 1:10, and 1:15; they found that the complexes with a stoichiometric ratio of 1:5 showed the best physical properties and the highest loading capacity of 12.18% ± 0.30% [43]. Yue et al. conducted a comparative study using the stoichiometric ratios of 1:1, 1.4:1, 2:1, 2.6:1, and 3:1 to generate oxymatrine-phospholipid complexes; they determined that optimal quantity was obtained at a ratio of 3:1 [20]. Therefore, a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 is not always optimal for the formulation of phospholipid complexes. For different types of drugs, we should experimentally adjust the stoichiometric ratio of active constituents and phospholipids according to distinct purposes, such as the highest drug loading.

4. Interactions between active constituents and phospholipids

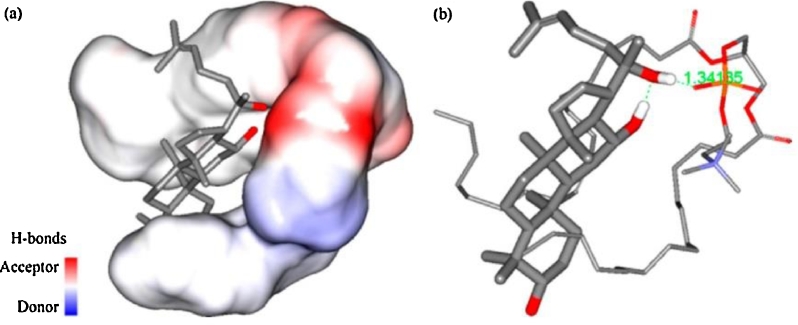

In 1989, Bombardelli reported a chemical bond between a flavonoid molecule and a phospholipid molecule [44]. In the past, there was controversy about the formation of phyto-phospholipid complexes [45], [46]. A study on the interaction of the 20(S)-protopanaxadiol phospholipid complexes at the molecular level using molecular docking showed that a hydrogen bond formed between one of the –OH group in 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and the —P O group in the phospholipids (Fig. 5) [47]. Phyto-phospholipid complexes, which empolyed by reaction of stoichiometric amount of phospholipids and the phytoconstituents complex, are revealed by the spectroscopic data that the phopspholipid – active ingredient interaction is due to the formation of hydrogen bond between the polar head and the polar functionalities of the active ingredient. The 1HNMR and 13CNMR data show that, the signal of the fatty chain has not changed both in free phospholipids and in the complex, which suggested that long aliphatic chains are wrapped around the active principle, producing lipophilic envelope [40]. The same conclusion can also be drawn from the thermal analysis in other studies that, the interaction between the two molecules had been attributed to formation of hydrogen bond or hydrophobic interaction [48].

Fig. 5.

A 3D conformational model of 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and phospholipids after docking and optimization. (a) 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and phospholipids with an interpolated charge surface; (b) hydrogen bond interactions between the molecules (reproduced with permission from [47]). Copyright 2016 MDPI.

In summary, most researchers agree that interactions between active constituents and phospholipids occur via hydrogen bonds to generate intermolecular force rather than chemical or hybrid bonds.

5. Advantage

5.1. Enhance the bioavailability

Multiple studies have revealed that phyto-phospholipid complexes can boost the absorption of through oral topical route, hence it can increase the bioavailability and reduce the required dose. So, it can significantly improve therapeutic benefit (Table 2).

Table 2.

| Parameter | Tmax(h) | Cmax(ng/ml) | AUC(0–24 h)(ng/h/ml) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25-OCH3-PPD | 2.25 ± 2.47 | 7.18 ± 3.39 | 26.65 ± 7.11 | [30] |

| 25-OCH3-PPD-phospholipid complexes | 2.10 ± 0.55 | 28.07 ± 19.52 | 97.24 ± 40.17 | [30] |

| Quercetin (103) | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 2.04 ± 0.38 | [42] |

| Quercetin-phospholipid complexes (103) | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 1.58 ± 0.11 | 8.12 ± 0.95 | [42] |

| Quercetin | 1.21 | 179.21 | 1368.26 | [19] |

| Quercetin-phospholipid complexes | 1.02 | 724.89 | 3321.05 | [19] |

| Kaempferol | 6.32 | 180.23 | 1139.59 | [19] |

| Kaempferol-phospholipid complexes | 5.83 | 323.56 | 2228.21 | [19] |

| Isorhamnetin | 7.21 | 195.96 | 1153.66 | [19] |

| Isorhamnetin-phospholipid complexes | 4.32 | 672.29 | 2722.37 | [19] |

| Luteolin | 2.5 ± 0.75 | 3410 ± 910 | 10,420 ± 2350 | [49] |

| luteolin–phospholipid complexes | 2 ± 0.63 | 9770 ± 1250 | 55,790 ± 5760 | [49] |

| Berberine | 0.5 | 66.01 ± 15.03 | 384.45 ± 108.62 | [50] |

| berberine-phospholipid complexes | 2 | 219.67 ± 6.02 | 1169.19 ± 93.75 | [50] |

| Oleanolic acid (OA) | 0.313 ± 0.12 | 59.5 ± 10.64 | 259.6 ± 22.98 | [51] |

| Solidified OA-phospholipid complexes | 0.46 ± 0.001 | 78.7 ± 10.18 | 360.6 ± 19.13 | [51] |

| Rosuvastatin | 1.94 ± 0.89 | 183.95*103± 4.56*103 | 671.56*103± 5.64*103 | [52] |

| Rosuvastatin–phospholipid complexes | 1.41 ± 0.95 | 674.17*103± 1.24*103 | 2018.59*103± 3.79*103 | [52] |

Zhang et al. prepared phospholipid complexes of 25-OCH3-PPD by solvent evaporation and found that the AUC(0–24 h) of the complex increased from 26.65 to 97.24, which was 3.65-fold higher than free 25-OCH3-PPD and resulted in a relative bioavailability of 365% [30]. Zhang prepared quercetin-phospholipid complexes and showed that the AUC(0–t) of the quercetin-phospholipid complexes increased from 2.04 to 8.12, which was a 3.98-fold increase [42]. Chen et al. examined the pharmacokinetics and oral bioavailability of these complexes by comparing quercetin, kaempferol and isorhamnetin extracts from Ginkgo biloba (GBE) to their respective phospholipid complexes (GBP) in rats. The AUC0−T of quercetin, kaempferol, and isorhamnetin for GBP increased by 2.42-, 1.95-, and 2.35-fold, respectively. This indicated that bioavailability was significantly enhanced by GBP compared with GBE [19].

After the formation of phyto-phospholipid complexes, the membrane permeability and oil–water partition coefficients of active constituents significantly improve. Thus, phyto-phospholipid complexes are more readily absorbed and generate increased bioavailability compared with free active constituents. Therefore, the preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes has recently gained increased attention. Phytosomal formulations have also gained important applications in the pharmaceutical industry. Furthermore, products based on phyto-phospholipid complexes have been available on the market to treat several diseases or improve human health, such as Silymarin Phytosome® from milk thistle seed for antihepatotoxic activities [53], Escin ß-sitosterol Phytosome® from horse chestnut fruit for antioedema effects, Leucoselect® Phytosome® from grape seed for antioxidant activities, and Greenselect® Phytosome® from green tea leaf for weight management [25], [54].

5.2. Enhance percutaneous absorption

Phyto-phospholipid complexes can easily transition from a hydrophilic environment into the lipophilic environment of the cell membrane and then enter the cell [37]. Therefore, a large number of studies have displayed that the percutaneous absorption of phytoconstituents is improved because of the application of phytoconstituents in form of phytosome [51], [55].

Due to the above characteristics of skin penetration, phyto-phospholipid complexes are widely employed in transdermal field [56], [57]. According to a recent report, Stefano TOGNI et al. prepared a quercetin-phospholipids 2% cream to increase the safety and tolerability of the quercetin-based formulation [56]. For the sake of overcoming the problem of lower skin penetration of Citrus auranticum and Glycyrrhiza glabra, Damle and Mallya developed a novel phyto-phospholipid complex cream [57].

5.3. Hepatoprotective effect

Compare with carriers employed in other drug delivery systems, phosphatidylcholine are crude ingredients that also reveal a great therapeutic benefits [39]. Phosphatidylcholine not only acts as an ingredient added to the formulation of phyto-phospholipid complexes, but also acts as a hepatoprotective. So, when phosphatidylcholine is taken by the patient, it will show the synergistic effect to protect the liver. In some situations, phospholipids also have the nutritional benefits.

Since 1994, Choline has been reported that it is necessary for normal liver function [58]. In vitro studies have shown that these PLs increase hepatic collagenase activity and may thus help prevent fibrosis and cirrhosis by encouraging collagen breakdown [59]. Besides, lecithin has been verified that it can also produce a protective effect in non-alcoholic fatty liver disorders and protection against various other toxic substances like hepatitis A and B [60]. Thus, it has a great protective effect of liver function. Khan et al. prepared a phospholipid complex of luteolin (LPC) by solvent evaporation and its hepatoprotective potential was assessed against D-galctosamine and lipopolysaccharide (GalN/LPS) induced hepatic damage [49].

5.4. Other advantage

Phyto-phospholipid complexes possess better drug complexation rate and the preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes is not complicated [61]. In addition, phyto-phospholipid complexes show better stability trait because the formation of chemical bonds between plant extracts and phosphatidylcholine molecule. By increasing the solubility of bile to active constituents, phyto-phospholipid complexes improve the liver targeting [37]. In some case, the duration of drug is prolonged. Due to a shorter half-time of Naringenin and rapid clearance from the body, frequent administration of the molecule is required. Wherefore, phospholipid complexes of Naringenin were prepared to prolong its duration in blood circulation [62]. According to another report, the phospholipid enhanced the plasma concentration of andrographolide in a significant manner and the effect persisted for a longer period of time. And the half-life of andrographolide–phospholipid complexes is 3.34 times that of pure andrographolide [63].

6. Methods for the preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes

6.1. Methods

There are three primary methods for preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes, including solvent evaporation, freeze-drying, and anti-solvent precipitation.

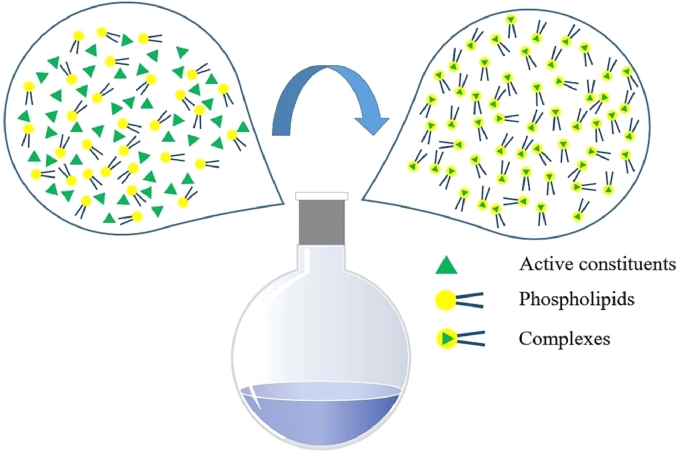

Solvent evaporation is a traditional and frequently used method for preparing phospholipid complexes. Shan and colleagues applied the solvent evaporation method to prepare oleanolic acid-phospholipid complexes [64]. Yu et al. prepared a berberine-phospholipid complexes (P-BER) by a rapid solvent evaporation method followed by a self-assembly technique, for the sake of developing a more efficient berberine drug delivery system [50]. Briefly, a designated stoichiometric ratio of active constituents and phosphatidylcholines was placed in the shared round-bottom and dissolved in a favorable solvent by heating at an optimal unchanging temperature with a certain time (Fig. 6). Prepared complexes can be obtained by evaporation to remove solvent under vacuum.

Fig. 6.

Schematic of the preparation of phyto-phospholipid complexes.

Other methods for preparing phospholipid complexes include anhydrous co-solvent lyophilization [65], [66] and anti-solvent precipitation [67], [68]. For example, Diosmin was firstly dissolved in DMSO, and then the diosmin was added to the solution of SPC followed by stirring for 3 h until complex formation [69]. Kaempferol-phospholipid complexes were also prepared by lyophilization method [70]. In addition, allium cepa-phospholipid complexes (ACP), which showed a significant antidiabetic activity, were prepared by anti-solvent precipitation [71].

Out of these, some methods described in various studies are discussed here. Li et al. developed supercritical antisolvent precipitation to produce puerarin phospholipid complexes and proposed that supercritical fluids were superior to conventional methods for drug phospholipid complexes preparation [72]. Damle and Mallya used Salting-Out Method and Film Formation Method to prepared a phyto-phospholipid complexes [57].

6.2. The influencing factors of phyto-phospholipid complexes

The factors that influence the formation of phyto-phospholipid complexes are mainly included solvent, stoichiometric ratio of active constituents, reaction temperature and reaction time [55], [69], [73]–75]. Depending on the desired target, different process variables can be selected. For maximum yield, Saoji et al. studied the influence of process variables such as the phospholipid-to-drug ratio, the reaction temperature and the reaction time, and used a central composite design to acquire the optimal formulation [55]. For best solubility and skin permeation, Das and Kalita prepared a rutin phytosome in different stoichiometric ratios [74]. According to a recent report [75], by changing stoichiometric ratios and reaction temperature, the highest yield apigenin-phospholipid complexes are prepared by Telange and his colleagues.

7. Yield (complexation rate) of phyto-phospholipid complexes

The yield of active constituents in complex with phospholipids represents an extremely important index for prescription screening. The weight difference between the initial active constituent and free compounds is the amount of active constituent in complex with phospholipids. The formula is as follows:

Where “a” is the weight or content of initial active constituent, “b” is the weight or content of free active constituent, and “(a – b)” is the weight or content of the phospholipid complexes [76].

Based on the properties of the active constituents, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or ultraviolet spectrophotometry can also be used to calculate the yield. The choice of solvent, temperature, duration, drug concentration, and stoichiometric ratio of active constituents to phospholipids are the main factors that affect the yield of phospholipid complexes.

8. Characterization of phyto-phospholipid complexes

8.1. Solubility and partition coefficient

Determining solubility in either water or organic solvents and the n-octanol/water partition coefficient (P) is necessary to characterize active constituents, active constituent phyto-phospholipid complexes and physical mixtures. Generally, phyto-phospholipid complexes have better lipophilicity and hydrophilicity than active constituents, and typically exhibit improved lipophilicity [24]. Rahila confirmed that embelin in complex has greater solubility in n-octanol and water than embelin and its respective physical mixtures [77].

8.2. Particle size and zeta potential

Particle size and zeta potential are important properties of complexes that are related to stability and reproducibility. In general, the average phospholipid complexes particle size ranged from 50 nm to 100 µm. Mazumder prepared sinigrin phytosome complexes, and the average particle size and zeta potential of the complex were 153 ± 39 nm and 10.09 ± 0.98 mV, respectively [67].

8.3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

SEM has yielded important insights into the solid state properties and surface morphology of complexes. TEM is often used to study the crystallization and dispersion of nano-materials and to measure the particle size of nanoparticles. SEM has shown that active compounds can be visualized in a highly crystalline state, but the shaped crystals disappeared after complexation. When diluted in distilled water under slight shaking, TEM showed that phyto-phospholipid complexes exhibit vesicle-like structures [67].

9. Structural verification of phyto-phospholipid complexes

9.1. Ultraviolet spectra (UV-spectra)

Samples that reflect different absorption in the UV wavelength range can be used to characterize own structural properties. Most studies have revealed no differences in the UV absorption characteristics of constituents before and after complexation. Xu et al. prepared luteolin-phospholipid complexes and found that the characteristic peaks of luteolin remained present [78]. Therefore, we conclude that the chromophores of compounds are not affected by being complexed with phospholipids.

9.2. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

In DSC, interactions can be observed by comparing the transition temperature, appearance of new peaks, disappearance of original peaks, melting points, and changes in the relative peaks area [76]. Phyto-phospholipid complexes usually display radically different characteristic peaks compared to those of a physical mixture. It is assumed that, in addition to the two fatty chains of phospholipids, strong interactions occur in the active ingredients and the polar part of phospholipids also inhibits free rotation. Das and Kalita prepared phyto-phospholipid complexes that contained rutin and the resulting DSC thermogram showed two characteristic peaks that were lower than that of the physical mixture and the peaks of rutin and PC disappeared [79].

9.3. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR is a powerful method for structural analysis, and yields different functional groups that show distinct characteristics in band number, position, shape, and intensity. The formation of phyto-phospholipid complexes can be verified by comparing the spectroscopy of phospholipid complexes to that of physical mixtures. Separate studies may show different results. Indeed, Das and Kalita prepared phyto-phospholipid complexes composed of rutin. The FTIR of a physical mixture of rutin and phyto-phospholipid complexes was superimposable with that of pure tutin [79]. When Mazumder et al. prepared sinigrin-phytosome complexes, the FTIR of phytosome complex showed different peaks from that of sinigrin, phospholipids and their mechanical mixtures [67].

9.4. X-ray diffraction

Currently, X-ray diffraction is an effective method to examine the microstructure of both crystal materials and some amorphous materials. X-ray diffraction is usually performed on either active constituents or active constituent phyto-phospholipid complexes, PCs and their physical mixtures. X-ray diffraction of an active constituent and physical mixture shows intense crystalline peaks that indicate a high crystal form. By contrast, active constituent phyto-phospholipid complexes do not exhibit crystalline peak, which suggests that the constituents in complex with phospholipids exhibit a molecular or amorphous form. That may account for the observation that phyto-phospholipid complexes have better lipophilicity and hydrophilicity than active constituents [24].

9.5. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR techniques play an important role in the identification of the structures of the complexes. As noted above, interactions between polyphenols and phospholipids are created by hydrogen bonds rather than chemical bonds. Angelico et al. established based on NMR data that hydrogen bonds can form between some polar phenolic functional groups of silybin A and phospholipids [80]. The spectra of different phyto-phospholipid complexes suggest that the hydrophobic side of lipids can act to cover the envelope on the central choline-bioactive parts of these complexes.

10. Conclusions

Phospholipids show affinity for active constituents through hydrogen bond interactions. In theory, a phospholipid complex strategy should be suitable for any active molecule not limited to polyphenols. With advances in research, we update the newest advances in phospholipids, phyto-active constituents, solvents, and stoichiometric ratios that are essential to prepare phospholipid complexes. The characterization and structural verification of phospholipid complexes has been well established. Bioavailability can be significantly improved with the help of phospholipids compared with chemically equivalent non-complexed forms. The potential of phyto-phospholipid complexes, with the effort of clinicians and other researchers, has a bright future for applications in the pharmaceutical field.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ajps.2018.05.011.

Contributor Information

Yihui Deng, Email: dengyihui@syphu.edu.cn.

Yanzhi Song, Email: songyanzhi@syphu.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Saller R, Meier R, Brignoli R. The use of silymarin in the treatment of liver diseases. Drugs. 2001;61(14):2035–2063. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidd PM. Bioavailability and activity of phytosome complexes from botanical polyphenols: the silymarin, curcumin, green tea, and grape seed extracts. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14(3):226–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Çelik HT, Gürü M. Extraction of oil and silybin compounds from milk thistle seeds using supercritical carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluids. 2015;100:105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namratha K, Shenai P, Chatra L. Antioxidant and anticancer effects of curcumin – a review. Çağdaş Tıp Dergisi. 2013;3(2):136–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsewak RS, Dewitt DL, Nair MG. Cytotoxicity, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Curcumins I–III from Curcuma longa. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(4):303–308. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(00)80048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apostolova E, Spaseska B, Crcarevska MS, Dodov MG, Raichki RS. An overview of phytosomes as a novel herbal drug delivery system. International Symposium at Faculty of Medical Sciences. 2015;1(1):95–96. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai J, Mumper RJ. Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules. 2010;15(10):7313–7352. doi: 10.3390/molecules15107313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng Z, Yuan C, Zhang F, et al. Intestinal absorption and first-pass metabolism of polyphenol compounds in rat and their transport dynamics in caco-2 cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food source and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):727–747. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phytosomes B.S. The new technology for enhancement of bioavailability of botanicals and nutraceuticals. Int J Health Res. 2009;2(3):225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kidd P, Head K. A review of the bioavailability and clinical efficacy of milk thistle phytosome: a silybin-phosphatidylcholine complex (Siliphos) Altern Med Rev. 2005;10(3):193–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ting Y, Jiang Y, Ho CT, Huang Q. Common delivery systems for enhancing in vivo bioavailability and biological efficacy of nutraceuticals. J Funct Foods. 2014;7:112–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei L, Kelly AL, Song M. Emulsion-based encapsulation and delivery systems for polyphenols. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2016;47:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aude M, Florence EL. Encapsulation of natural polyphenolic compounds: a review. Pharmaceutics. 2011;3(4):793–829. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics3040793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He JL, Luo LY, Zeng L. Recent advances in research on preparation technologies and applications of tea polyphenol nanoparticles. Food Sci. 2011;32:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert J, Sang S, Hong J, et al. Peracetylation as a means of enhancing in vitro bioactivity and bioavailability of epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:2111–2116. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulholland PJ, Ferry DR, Anderson D, et al. Pre-clinical and clinical study of QC12, a water-soluble, pro-drug of quercetin. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(2):245–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1008372017097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hostettmann K. National conference on "recent advances in herbal drug technology". Int J Pharma Sci. 2010;36(1):S1–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen ZP, Sun J, Chen HX, et al. Comparative pharmacokinetics and bioavailability studies of quercetin, kaempferol and isorhamnetin after oral administration of Ginkgo biloba extracts, Ginkgo biloba extract phospholipid complexes and Ginkgo biloba extract solid dispersions in rats. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(8):1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue PF, Yuan HL, Ming Y, et al. Preparation, characterization and pharmacokinetics in vivo of oxymatrine–phospholipid complex. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2009;1:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maiti K, Mukherjee K, Gantait A, Saha BP, Mukherjee PK. Curcumin–phospholipid complex: preparation, therapeutic evaluation and pharmacokinetic study in rats. Int J Pharma. 2007;330(1–2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao Y, Song Y, Chen Z, Ping Q. The preparation of silybin-phospholipid complex and the study on its pharmacokinetics in rats. Int J Pharma. 2006;307(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan J, Alexander A, Saraf S, Saraf S. Recent advances and future prospects of phyto-phospholipid complexation technique for improving pharmacokinetic profile of plant actives. J Control Release. 2013;168(1):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghanbarzadeh B, Babazadeh A, Hamishehkar H. Nano-phytosome as a potential food-grade delivery system. Food Biosci. 2016;15:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel J, Patel R, Khambholja K, Patel N. An overview of phytosomes as an advanced herbal drug delivery system. Asian J Pharma Sci. 2008;4(6):363–371. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bombardelli E, Sabadie M. Phospholipid complexes of extracts of vitis vinifera, their preparation process and pharmaceutical and cosmetic compositions containing them. US Patent No. 4963527; 1990.

- 27.Li J, Wang X, Zhang T, et al. A review on phospholipids and their main applications in drug delivery systems. Asian J Pharma Sci. 2015;10(2):81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suriyakala PC, Babu NS, Rajan DS, Prabakaran L. Phospholipids as versatile polymer in drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;6(1):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duric M, Sivanesan S, Bakovic M. Phosphatidylcholine functional foods and nutraceuticals: a potential approach to prevent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 2012;114(4):389–398. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Zhang Y, Guo S, Bai F, Wu T, Zhao Y. Improved oral bioavailability of 20(R)-25-methoxyl-dammarane-3β, 12β, 20-triol using nanoemulsion based on phospholipid complex: design, characterization, and in vivo pharmacokinetics in rats. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:3707–3716. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S114374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan Q, Shan L, Chen X, et al. Design and evaluation of a novel evodiamine-phospholipid complex for improved oral bioavailability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012;13(2):534–547. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9772-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parry MJ, Alakoskela JMI, Khandelia H, et al. High-affinity small molecule−phospholipid complex formation: binding of siramesine to phosphatidic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(39):12953–12960. doi: 10.1021/ja800516w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel J, Patel R, Khambholja K, Patel N. An overview of phytosomes as an advanced herbal drug delivery system. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2009;4(6):363–371. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naik SR, Pilgaonkar VW, Panda VS. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Ginkgo biloba phytosomes in rat brain. Phytother Res. 2006;20(11):1013–1016. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bombardelli E, Curri S, Della Loggia R, Gariboldi P, Tubaro A. Anti-inflammatory activity of 18-ß-glycyrrhetinic acid in phytosome form. Fitoterapia. 1989;60:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karimi N, Ghanbarzadeh B, Hamishehkar H, Keyvani F, Pezeshki A, Gholian MM. Phytosome and liposome: the beneficial encapsulation systems in drug delivery and food application. Appl Food Biotechnol. 2015;2(3):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Awasthi R, Kulkarni G, Pawar VK. Phytosomes: an approach to increase the bioavailability of plant extracts. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2011;3(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shakeri A, Sahebkar A. Phytosome: a fatty solution for efficient formulation of phytopharmaceuticals. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2016;10(1):7–10. doi: 10.2174/1872211309666150813152305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semalty A. Cyclodextrin and phospholipid complexation in solubility and dissolution enhancement: a critical and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(8):1255–1272. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.916271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tripathy S, Patel DK, Barob L, Naira SK. A review on phytosomes, their characterization, advancement & potential for transdermal application. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2013;3(3):147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chauhan NS, Rajan G, Gopalakrishna B. Phytosomes: a potential phyto-phospholipid carriers for herbal drug delivery. J Pharm Res. 2009;2(7):1267–1270. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang K, Zhang M, Liu Z, et al. Development of quercetin-phospholipid complex to improve the bioavailability and protection effects against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in SD rats. Fitoterapia. 2016;113:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maryana W, Rachmawati H, Mudhakir D. Formation of phytosome containing silymarin using thin layer-Hydration technique aimed for oral delivery. Mater Today Proc. 2016;3(3):855–866. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bombardelli E, Curri SB, Loggia RD, Negro PD, Tubaro A, Gariboldi P. Complexes between phospholipids and vegetal derivatives of biological interest. Fitoterapia. 1989;60:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alam MA, Aljenoobi FI, Almohizea AM. Commercially bioavailable proprietary technologies and their marketed products. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(19–20):936–949. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afanas'eva YG, Fakhretdinova ER, Spirikhin LV, Nasibullin RS. Mechanism of interaction of certain flavonoids with phosphatidylcholine of cellular membranes. Pharm Chem J. 2007;41(7):354–356. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pu Y, Zhang X, Zhang Q, et al. 20(S)-Protopanaxadiol phospholipid complex: process optimization, characterization, in vitro dissolution and molecular docking studies. Molecules. 2016;21(10):1396. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semalty A, Semalty M, Rawat MSM, Franceschi F. Supramolecular phospholipids–polyphenolics interactions: the PHYTOSOME® strategy to improve the bioavailability of phytochemicals. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(5):306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan J, Saraf S, Saraf S. Preparation and evaluation of luteolin–phospholipid complex as an effective drug delivery tool against GalN/LPS induced liver damage. Pharm Dev Technol. 2016;21(4):475–486. doi: 10.3109/10837450.2015.1022786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu F, Li Y, Chen Q, et al. Monodisperse microparticles loaded with the self-assembled berberine-phospholipid complex-based phytosomes for improving oral bioavailability and enhancing hypoglycemic efficiency. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2016;103:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang Q, Yang X, Du P, Zhang H, Zhang T. Dual strategies to improve oral bioavailability of oleanolic acid: enhancing water-solubility, permeability and inhibiting cytochrome P450 isozymes. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2016;99:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beg S, Raza K, Kumar R, Chadha R, Katare O, Singh B. Improved intestinal lymphatic drug targeting via phospholipid complex-loaded nanolipospheres of rosuvastatin calcium. RSC Adv. 2016;6(10):8173–8187. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Usman M, Ahmad M, Madni AU, et al. In-vivo kinetics of silymarin (milk thistle) on healthy male volunteers. Trop J Pharm Res. 2009;8(4):311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gilardini L, Pasqualinotto L, Pierro FD, Risso P, Invitti C. Effects of greenselect Phytosome® on weight maintenance after weight loss in obese women: a randomized placebo-controlled study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):233. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1214-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saoji SD, Raut NA, Dhore PW, Borkar CD, Popielarczyk M, Dave VS. Preparation and evaluation of phospholipid-based complex of standardized centella extract (SCE) for the enhanced delivery of phytoconstituents. AAPS J. 2016;18(1):102–114. doi: 10.1208/s12248-015-9837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Togni S, Maramaldi G, Pagin I, Cattaneo R, Eggenhoffner R, Giacomelli L. Quercetin-phytosome 2% cream: evaluation of the potential photoirritant and sensitizing effects. esperienze dermatologiche - dermatological experiences 2016;18:85–7.

- 57.Damle M, Mallya R. Development and evaluation of a novel delivery system containing phytophospholipid complex for skin aging. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2016;17(3):607–617. doi: 10.1208/s12249-015-0386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canty DJ, Zeisel SH. Lecithin and choline in human health and disease. Nutr Rev. 1994;52(10):327–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lieber CS, Decarli LM, Mak KM, Kim CI, Leo MA. Attenuation of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis by polyunsaturated lecithin. Hepatology. 1990;12(6):1390–1398. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aleynik SI, Leo MA, Ma X, Aleynik MK, Lieber CS. Polyenylphosphatidylcholine prevents carbon tetrachloride-induced lipid peroxidation while it attenuates liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 1997;27(3):554–561. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karimi N, Ghanbarzadeh B, Hamishehkar H, Keivani F, Pezeshki A, Gholian MM. Phytosome and liposome: the beneficial encapsulation systems in drug delivery and food application. Appl Food Biotech. 2015;2(3):17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Semalty A, Semalty M, Singh D, Rawat M. Preparation and characterization of phospholipid complexes of naringenin for effective drug delivery. J Incl Phenom Macro. 2010;67(3–4):253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maiti K, Mukherjee K, Murugan V, Saha BP, Mukherjee PK. Enhancing bioavailability and hepatoprotective activity of andrographolide from andrographis paniculata, a well-known medicinal food, through its herbosome. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90(1):43–51. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shan L, Tan QY, Hong W, Hong L, Zhang JQ. Preparation, characterization and in vitro anti-tumor activities of evodiamine phospholipids complex. Chin Pharm J. 2012;47(7):517–523. [Google Scholar]

- 65.He N, Zhang L, Zhu F, Rui K, Yuan MQ, Qin H. Formulation of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems for insulin-soybean lecithin complex. West China J Pharm Sci. 2010;25(4):396–399. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al SJE. Physicochemical characterization and determination of free radical scavenging activity of rutin-phospholipid complex. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3(3):909–913. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazumder A, Dwivedi A, Preez JLD, Plessis JD. In vitro wound healing and cytotoxic effects of sinigrin-phytosome complex. Int J Pharm. 2015;498(1–2):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh D, Rawat MSM, Semalty A, Semalty M. Chrysophanol–phospholipid complex. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2013;111(3):2069–2077. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freag MS, Elnaggar YS, Abdallah OY. Lyophilized phytosomal nanocarriers as platforms for enhanced diosmin delivery: optimization and ex vivo permeation. Int J Nanomed. 2013;8:2385–2397. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S45231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Telange DR, Patil AT, Pethe AM, Tatode AA, Anand S, Dave VS. Kaempferol-phospholipid complex: formulation, and evaluation of improved solubility, in vivo bioavailability, and antioxidant potential of Kaempferol. J Excip Food Chem. 2016;7(4):89–116. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Habbu P, Madagundi S, Shastry R, Vanakudri R, Kulkarni V. Preparation and evaluation of antidiabetic activity of allium cepa-phospholipid complex (phytosome) in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. RGUHS J Pharm Sci. 2015;5:132–141. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Y, Yang DJ, Chen SL, Chen SB, Chan AS. Process parameters and morphology in puerarin, phospholipids and their complex microparticles generation by supercritical antisolvent precipitation. Int J Pharm. 2008;359(1–2):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Z, Chen Y, Deng J, Jia X, Zhou J, Lv H. Solid dispersion of berberine–phospholipid complex/TPGS 1000/SiO 2: preparation, characterization and in vivo studies. Int J Pharm. 2014;465(1):306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Das MK, Kalita B. Design and evaluation of phyto-phospholipid complexes (phytosomes) of rutin for transdermal application. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2014;4(10):51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Telange DR, Patil AT, Pethe AM, Fegade H, Anand S, Dave VS. Formulation and characterization of an apigenin-phospholipid phytosome (APLC) for improved solubility, in vivo bioavailability, and antioxidant potential. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;108:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hao H, Jia Y, Han R, Amp IA. Phytosomes: an effective approach to enhance the oral bioavailability of active constituents extracted from plants. J Chin Pharm Sci. 2013;22(5):385–392. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pathan RA, Bhandari U. Preparation & characterization of embelin–phospholipid complex as effective drug delivery tool. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl. 2011;69(1–2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu K, Liu B, Ma Y, et al. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of luteolin-phospholipid complex. Molecules. 2009;14(9):3486–3493. doi: 10.3390/molecules14093486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Das MK, Kalita B. Design and evaluation of phyto-phospholipid complexes (phytosomes) of rutin for transdermal application. J J Appl Pharm Sci. 2014;4(10):51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Angelico R, Ceglie A, Sacco P, Colafemmina G, Ripoli M, Mangia A. Phyto-liposomes as nanoshuttles for water-insoluble silybin–phospholipid complex. Int J Pharm. 2014;471(1–2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.