Abstract

Background

Recurrent apnoea is common in preterm infants. These episodes can lead to hypoxaemia and bradycardia, which may be severe enough to require the use of positive pressure ventilation. In infants with apnoea, methylxanthine treatment has been used successfully to prevent further episodes. It is possible that prophylactic therapy given to all very preterm infants soon after birth might prevent apnoea and the need for additional ventilator support.

Objectives

To determine the effect of prophylactic treatment with methylxanthine on apnoea, bradycardia, episodes of hypoxaemia, use of mechanical ventilation, and morbidity in preterm infants at risk for apnoea of prematurity

Search methods

The standard search strategy of the Neonatal Review Group was updated in August 2010. This included searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Oxford Database of Perinatal Trials, MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE.

Selection criteria

All trials using random or quasi‐random patient allocation in which prophylactic methylxanthine (caffeine or theophylline) was compared with placebo or no treatment in preterm infants were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

The standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration and its Neonatal Review Group were used.

Main results

Three studies were eligible for inclusion in the review. Two small studies (randomising a total of 104 infants) evaluated the effect of prophylactic caffeine on short term outcomes. There were no meaningful differences between the caffeine and placebo groups in the number of infants with apnoea, bradycardia, hypoxaemic episodes, use of IPPV or side effects in either of the studies. Only two outcomes (use of IPPV and tachycardia) were common to the two studies and meta‐analysis showed no substantive differences between the groups. One large trial of caffeine therapy (CAP 2006) in a heterogeneous group of infants at risk for and having apnoea of prematurity demonstrated an improved rate of survival without developmental disability at 18 to 21 months corrected age. The reports of the subgroup of infants treated with prophylactic caffeine did not demonstrate any significant differences in clinical outcomes except for a decrease in the risk of PDA ligation.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review do not support the use of prophylactic caffeine for preterm infants at risk of apnoea.

Any future studies need to examine the effects of prophylactic methylxanthines in preterm infants at higher risk of apnoea. This should include examination of important clinical outcomes such as need for IPPV, neonatal morbidity, length of hospital stay and long term development.

Plain language summary

Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnoea in preterm infants

Apnea is a pause in breathing of greater than 20 seconds. It may occur repeatedly in preterm babies (born before 34 weeks). Methylyxanthines (such as theophylline and caffeine) are drugs that are believed to stimulate breathing efforts and have been used to reduce apnoea. It has been suggested that preterm babies with apnoea should receive prophylactic caffeine as a preventative measure.

Two small studies and one large study were identified. The two small studies enrolled infants given caffeine as a preventative measure. Neither study demonstrated any decrease in apnoea or other short term complications.

The one large study included a heterogeneous group of infants who received therapy for a variety of indications (prevention, treatment and avoidance of post‐extubation apnoea of prematurity). In this overall population there was an improvement in clinical outcome at hospital discharge and developmental outcome at 18 to 21 months; however, these benefits could not be proven in the subpopulation who received prophylactic caffeine. A decrease in PDA was noted in this subpopulation.

Background

Description of the condition

Recurrent episodes of apnoea are common in preterm infants and the incidence as well as the severity increases at lower gestational ages (Henderson‐Smart 1995). Although apnoea can occur spontaneously and be attributed to prematurity alone, it can also be provoked or made more severe if there is an additional insult such as infection, hypoxaemia or intracranial pathology. The American Academy of Pediatrics defines infant apnoea as a pause in breathing of greater than 20 seconds, or one of less than 20 seconds if with bradycardia and/or cyanosis (AAP 2003). The definition, diagnosis, and treatment (drugs and assisted ventilation therapy) of apnoea of prematurity have been reviewed (Finer 2006).

Description of the intervention

Methylxanthines are thought to stimulate breathing efforts and have been used in clinical practice to reduce apnoea since the 1970's. Theophylline and caffeine are two forms of methylxanthine that have been used and they are effective for the treatment of infants with recurrent apnoea (Henderson‐Smart 2009). Their mechanism of action is not certain. Possibilities include increased chemoreceptor responsiveness (based on increased breathing responsiveness to CO2), enhanced respiratory muscle performance and generalised central nervous system excitation.

How the intervention might work

In the treatment of apnoea, caffeine has similar effects to theophylline (Henderson‐Smart 2010), but has potential therapeutic advantages due to the larger gap between therapeutic blood levels and those levels associated with toxic effects, more reliable enteral absorption and the longer half life which allows once daily administration (Blanchard 1992).

Why it is important to do this review

If prolonged, apnoea can lead to hypoxaemia and reflex bradycardia which may require active resuscitative efforts to reverse. There are clinical concerns that these episodes might be harmful to the developing brain or cause dysfunction of the gut or other organs (Henderson‐Smart 1995). Frequent episodes may be accompanied by respiratory failure of sufficient severity as to lead to intubation and the use of intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV).

Objectives

To determine the effect of prophylactic treatment with methylxanthine on apnoea, bradycardia, episodes of hypoxaemia, use of mechanical ventilation, and morbidity in preterm infants at risk for apnoea of prematurity.

To evaluate a difference in response depending on quality of the study, type (caffeine or theophylline) or dose of methylxanthine, gestational age at birth, postnatal age at study entry, or duration of treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All trials utilising random or quasi‐random patient allocation in which treatment was compared with placebo or no treatment were eligible.

Types of participants

Preterm infants, particularly those born at less than 34 weeks gestation who are at risk of developing recurrent apnoea, bradycardia and hypoxic episodes.

Types of interventions

Prophylactic methylxanthine (caffeine, theophylline or aminophylline) versus placebo or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary

Occurrence of recurrent apnoea, bradycardia and hypoxaemia.

Use of CPAP and/or IPPV.

Death before hospital discharge.

Secondary

Acute drug side effects (tachycardia or feed intolerance leading to omission of treatment).

Neonatal morbidity such as ‐ patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment, intracranial haemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis.

Duration of IPPV.

Duration of oxygen therapy.

Chronic lung disease indicated by respiratory support (oxygen &/or positive airway pressure) still given at 36 weeks postmenstrual age.

Longer term outcomes such as growth and neurodevelopmental outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

The standard search strategy of the Neonatal Review Group was used. This included searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2010), MEDLINE (1966 to August 2010), CINAHL (1982 to August 2010) and EMBASE (1988 to August 2010) using MeSH term preterm infant, and text terms methylxanthines (caffeine, theophylline, aminophylline), apnoea (or apnea), as well as a search of previous reviews including cross references, and conference proceedings including abstracts from the Society for Pediatric Research meeting 2001 to 2010.

Data collection and analysis

The standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration and its Neonatal Review Group were used. The methodological quality of each trial was reviewed by the second review author blinded to trial authors and institution(s). Additional information was supplied by Bucher 1988 to clarify methodology. The manuscript reporting the unpublished results of a trial was supplied by Levitt 1988.

Each review author extracted data separately, then results were compared and differences resolved. An outcome was analysed if there was more than 80% ascertainment.

The standard method of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group was used to analyse the data, utilizing risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) as well as differences in means.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Details of the three included studies (Levitt 1988; Bucher 1988; CAP 2006) are in the table 'Characteristics of Included Studies' and discussed briefly below. One study, Larsen 1995, was excluded due to not having a control group.

Included studies

Bucher 1988 studied preterm infants of less than 33 weeks gestation (mean approximately 30 weeks). Levitt 1988 entered infants of less than 31 weeks gestation (mean approximately 29 weeks).

Both studies used a loading dose of 20 mg/kg of caffeine citrate but Levitt 1988 used 5 mg/kg/day as maintenance, half that used in Bucher 1988. While in Levitt 1988 treatment was continued until the infants reached 32 weeks postmenstrual age, only 96 hours of treatment was given in Bucher 1988.

Bucher 1988 did not report apnoea; instead, he recorded episodes of bradycardia and hypoxaemia, which often occur during apnoea. These were obtained from a computerised record of heart rate (bradycardia was defined as a 20% or more fall in heart rate from the baseline within 20 seconds) and transcutaneous oxygen tension (hypoxaemia was defined as a 20% or more fall in oxygen level from the baseline within 20 seconds). Levitt 1988 used a combination of clinical and polygraphic studies to record apnoea (77% of the tape recordings were acceptable for analysis). Levitt 1988 defined apnoea as cessation of breathing for 20 seconds or more with associated bradycardia (less than 100/min) or cyanosis.

The CAP Trial (CAP 2006) examined the primary outcome of death or disability at 18 to 21 months corrected age in preterm infants randomised to either caffeine or placebo. Preterm infants were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were deemed to be at risk of apnoea of prematurity, if they were experiencing apnoea of prematurity or if prophylactic methylxanthine was deemed indicated prior to extubation. A report of hospital outcomes of enrolled infants was first published in 2006 (CAP 2006). A report of the long term effects of caffeine was published in 2007 and results of a post‐hoc subgroup analyses were published in 2010 (CAP 2006). The post‐hoc subgroup analyses included an analysis of outcomes according to the indication for treatment, which included the subgroup receiving caffeine or placebo for apnoea prophylaxis, and hence is eligible for this review. As randomisation was not stratified according to the indication for inclusion in the CAP Trial, the trial authors note that “caution should be exercised in the interpretation of these subanalyses”.

Excluded studies

One study, Larsen 1995, was excluded due to not having a control group.

Risk of bias in included studies

Three studies are generally of high quality except that follow‐up was incomplete in Levitt 1988 and Bucher 1988. Bucher 1988 and CAP 2006 did not report apnoea.

Effects of interventions

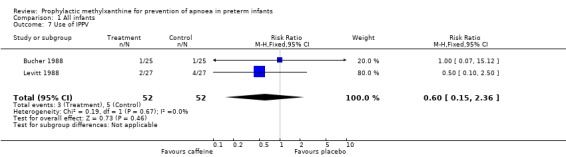

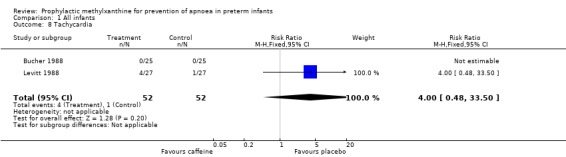

Two trials (Bucher 1988; Levitt 1988) randomised a total of 104 infants; studied the short term effects of caffeine prophylaxis on apnoea and related symptoms. There were no differences between the caffeine and placebo groups in either of the studies in the number of infants with apnoea (Levitt 1988), bradycardia, hypoxaemic episodes (Bucher 1988), use of IPPV or side effects (Bucher 1988; Levitt 1988).

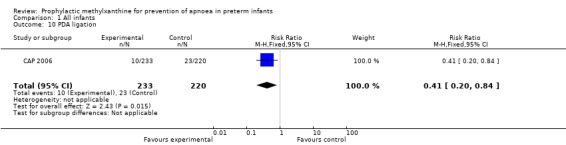

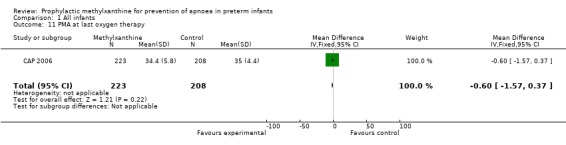

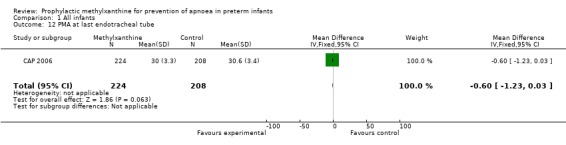

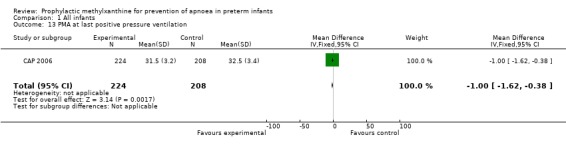

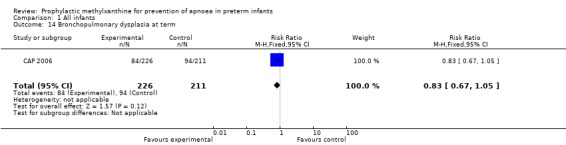

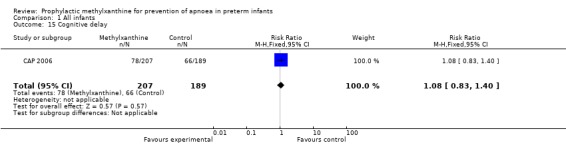

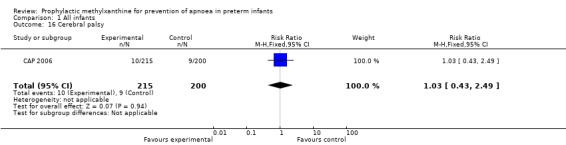

Two trials (Levitt 1988; CAP 2006) reported longer term clinical outcomes. Levitt 1988 reported on the long term follow‐up of 30 (56%) of 54 infants. This was not only incomplete, but was reported by apnoea incidence rather than by trial treatment group. CAP 2006 did not report apnoea as an outcome, but in the post‐hoc analysis of the subgroup enrolled for prevention of apnoea, caffeine was found to reduce the rate of PDA ligation (total of 453 infants, RR 0.4 (95%CI 0.20 to 0.84) and lower the postmenstrual age (PMA) at last positive pressure ventilation (total of 432 infants, mean difference ‐1.00, 95%CI ‐1.32 to ‐0.38). In other outcomes for this subgroup, including the PMA at last oxygen therapy, PMA at last endotracheal tube, bronchopulmonary dyplasia at term, cognitive delay, cerebral palsy, death or major disability, there were no differences.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The total number of infants (104) studied in the two trials of Bucher 1988 and Levitt 1988 is small. As a result, the power of these studies is limited to detect only large differences in outcome (e.g. 50% relative risk reduction) even for outcomes which are common, such as bradycardia (> 24 /day) and hypoxaemic episodes (> 12 /day) where, in the study of Bucher 1988, there is more than 60% incidence in the control group and similar outcomes in the treatment group. CAP 2006 did not report apnoea, but reported that caffeine reduced use of PDA ligation and lower PMA at last positive pressure ventilation in the subgroup of infants randomised for apnoea prophylaxis. Other long term outcomes were not different.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

It is possible that failure to observe an effect of prophylactic caffeine in the Bucher 1988 trial was due to measurement of hypoxaemia and mild bradycardia as primary outcomes ‐ events associated with apnoea, rather than apnoea itself. It could be argued that such events might be increased in the treatment group if caffeine increased arousal, movements and metabolic rate. This would minimise any differences due to a reduction in apnoea, if that occurred. In the Levitt 1988 trial, however, the clinical events of apnoea and bradycardia were recorded and no differences were found between infants who received prophylactic caffeine and those on placebo.

The CAP Trial (CAP 2006) has originally published outcomes at discharge and growth and development at 18 to 21 months (2006 and 2007). These results include a large number of very low birthweight infants (Caffeine group 1006, placebo group 1000) with any one of the three indications for trial entry (prophylactic prevention of apnoea in 22%, treatment of apnoea in 40% or prophylaxis for endotracheal extubation in 38%). In this trial outcomes in the prophylactic group do not include apnoea frequency or severity, but did provide short and long term follow up outcomes in a large number of infants. It is important to note that randomisation in the CAP Trial was not stratified by indication for enrolment.

Quality of the evidence

The trials in this review did not allow subgroup analyses to determine whether the results varied by the type (caffeine or theophylline) or dose of methylxanthine, gestational or postnatal age at study entry, or duration of treatment.

Potential biases in the review process

There is not enough data in trials on the apnoea outcome.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Although no good effect of caffeine used as prophylaxis for apnoea was found in this review, methylxanthines, including caffeine, are known to be effective in reducing existing apnoea and the use of IPPV when used to treat infants with apnoea (Henderson‐Smart 2009). In addition, another review has suggested that methylxanthines prior to extubation might be of benefit in reducing the rate of respiratory failure, which is due in part to hypoventilation and apnoea (Henderson‐Smart 2008a).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review suggest that the use of prophylactic methylxanthine for preterm infants at risk of apnoea reduces the duration of need for positive pressure ventilation and the rate of PDA ligation. There is no direct data from randomised trials to indicate that the incidence or severity of apnoea itself, or its associated symptoms, is prevented or reduced by the use of methylxanthines for the clinical indication of apnoea prophylaxis in preterm infants.

Implications for research.

Any future studies should address the effects of prophylactic methylxanthines in preterm infants at higher risk of apnoea, bradycardia or hypoxaemic episodes, and possibly address the question of whether a higher dose of caffeine might be more effective. These should include examination of important clinical outcomes such as need for IPPV, length of hospital stay and long term development.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 February 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1996 Review first published: Issue 2, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 April 2012 | Amended | Contact person changed. |

| 7 December 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 3 August 2010 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | This update includes the addition of outcomes from a subgroup of the CAP Trial 2006 (CAP 2006). |

| 3 August 2010 | New search has been performed | This updates the review "Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants" published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. New co‐author Antonio De Paoli. |

| 12 August 2009 | Amended | Corrections made to citations in 'Studies awaiting classification'. |

| 24 June 2008 | New search has been performed | This review updates the existing review of 'Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants' published in The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Disk Issue 2, 2006 (Henderson‐Smart 2006). Outcomes have been updated. A new trial (CAP TRIAL 2006; 'Studies awaiting classification') has been added. |

| 17 January 2006 | New search has been performed | This review updates the existing review of 'Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants' which was published in The Cochrane Library, Disk Issue 2, 2002. The search strategy has been updated to include the databases, EMBASE and CINAHL. One new trial was identified as a result of the most recent search and was excluded. Therefore, there is no change in the conclusion that there is no evidence from randomized trials to support the use of prophylactic methylxanthine in preterm infants at risk of apnea, bradycardia or hypoxemic episodes. |

| 4 February 1999 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Levitt for a copy of her unpublished paper and to Prof. Bucher for additional information about his study.

The Cochrane Neonatal Review Group has been funded in part with Federal funds from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, USA, under Contract No. HHSN267200603418C.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All infants.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

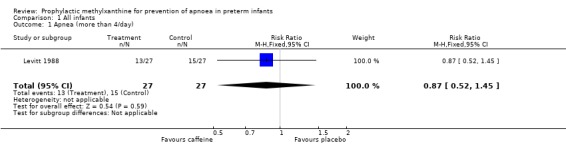

| 1 Apnea (more than 4/day) | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.52, 1.45] |

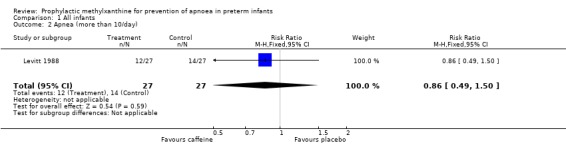

| 2 Apnea (more than 10/day) | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.49, 1.50] |

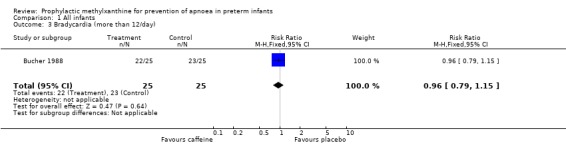

| 3 Bradycardia (more than 12/day) | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.79, 1.15] |

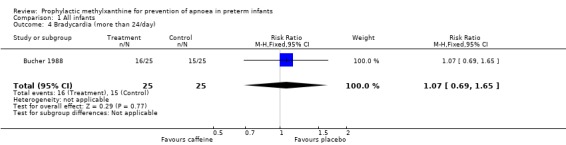

| 4 Bradycardia (more than 24/day) | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.69, 1.65] |

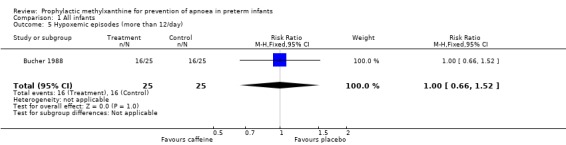

| 5 Hypoxemic episodes (more than 12/day) | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.66, 1.52] |

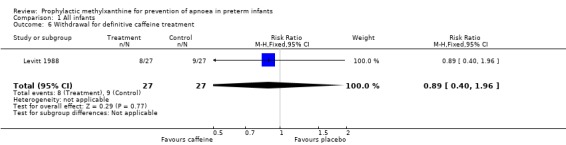

| 6 Withdrawal for definitive caffeine treatment | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.40, 1.96] |

| 7 Use of IPPV | 2 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.15, 2.36] |

| 8 Tachycardia | 2 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.48, 33.50] |

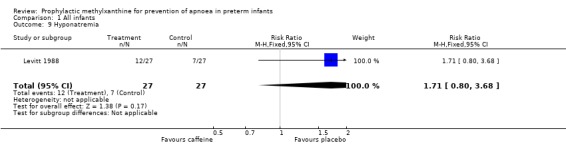

| 9 Hyponatremia | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.80, 3.68] |

| 10 PDA ligation | 1 | 453 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.20, 0.84] |

| 11 PMA at last oxygen therapy | 1 | 431 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.57, 0.37] |

| 12 PMA at last endotracheal tube | 1 | 432 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐1.23, 0.03] |

| 13 PMA at last positive pressure ventilation | 1 | 432 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐1.62, ‐0.38] |

| 14 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia at term | 1 | 437 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.67, 1.05] |

| 15 Cognitive delay | 1 | 396 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.83, 1.40] |

| 16 Cerebral palsy | 1 | 415 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.43, 2.49] |

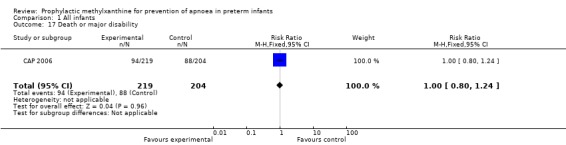

| 17 Death or major disability | 1 | 423 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.80, 1.24] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 1 Apnea (more than 4/day).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 2 Apnea (more than 10/day).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 3 Bradycardia (more than 12/day).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 4 Bradycardia (more than 24/day).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 5 Hypoxemic episodes (more than 12/day).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 6 Withdrawal for definitive caffeine treatment.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 7 Use of IPPV.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 8 Tachycardia.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 9 Hyponatremia.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 10 PDA ligation.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 11 PMA at last oxygen therapy.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 12 PMA at last endotracheal tube.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 13 PMA at last positive pressure ventilation.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 14 Bronchopulmonary dysplasia at term.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 15 Cognitive delay.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 16 Cerebral palsy.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All infants, Outcome 17 Death or major disability.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bucher 1988.

| Methods | Concealment of randomisation ‐ yes; blinding of intervention ‐ yes; follow up complete; blinding of outcome assessment ‐ yes. | |

| Participants | 50 preterm infants <33 weeks gestation (stratified into those born at 26‐29, 30‐32 weeks), 48 hrs old, spontaneous breathing for 24 hrs, in a single centre. | |

| Interventions | Caffeine citrate 20 mg/kg load at 48 hrs and 10 mg/kg at 72 and 96 hrs of age. Total duration of study period 96 hrs. Saline placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Polygraph recording of bradycardia (>20% fall in heart rate from baseline within 20 sec); hypoxaemic episodes (>20% decrease from baseline within 20 sec); use of IPPV; tachycardia | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Intervention and outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Apnoea not measured |

CAP 2006.

| Methods | Concealment of randomisation ‐ yes (off site in pharmacy); blinding of intervention ‐ yes in 90.5%; follow up 96% for perinatal outcomes, also follow‐up to 18‐21months; blinding of outcome assessment ‐ yes. | |

| Participants | The overall reporting of the CAP trial contained 2006 infants with birth weights of 500 to 1250 g during the first 10 days of life who entered the trial because they were to be given prophylactic therapy to prevent apnoea, treatment of recurrent apnoea or to facilitate extubation. Davis 2010 reports a post‐hoc subgroup analysis including an analysis of outcomes according to the indication for treatment, which included the subgroup receiving caffeine or placebo for apnoea prophylaxis, and hence is eligible for this review (Davis PG et al 2010). | |

| Interventions | Caffeine citrate 20 mg/kg loading dose and 5 mg/kg daily (1006 infants) vs placebo of normal saline (1000 infants) commenced at an average of 3 days. The maintenance study drug could be doubled if there was concern about increased apnoea or reduced if there was concern about toxicity. Infants were eligible if they had apnoea, or if prevention of apnoea or assistance prior to endotracheal extubation was considered necessary in the first ten days of life by the treating clinician. In this review only the results of the post‐hoc subgroup analysis of the infants treated to prevent apnoea are included. | |

| Outcomes | The total number of infants evaluated for in each outcome are given in brackets. The outcomes in the perinatal period up to term corrected age, included age at last oxygen therapy (431), age at last positive pressure ventilation (432) and endotracheal intubation (432). Patent ductus arteriosus ligation (453) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (437). The longer term outcomes of this study included death or major disability (423), cognitive delay (396), cerebral palsy (415), at a corrected age of 18 to 21 months. Apnea outcomes were not reported. Only the outcomes for infants enrolled for prophylactic prevention of apnoea in the CAP Trial 2010 were used in this review. |

|

| Notes | In the whole CAP Trial the birth characteristics of mothers and infants in the caffeine and placebo groups were similar across the multiple centres in various countries. Antenatal corticosteroids 88% vs 87%, chorioamnionitis 14% vs 13%, caesarean section 62% vs 63%. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Blinded randomisation |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Application to infants and assessment of outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Apnea not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

Levitt 1988.

| Methods | Concealment of randomisation ‐ yes (off site in pharmacy); blinding of intervention ‐ yes ; follow up 96% for apnoea; blinding of outcome assessment ‐ yes. | |

| Participants | 54 preterm infants born at <31 weeks, randomised within 24 hrs of birth or on endotracheal extubation in the first week of age. Exclusions ‐ major congenital abnormality, intraventricular haemorrhage, congestive heart failure, metabolic disorder, septicaemia. | |

| Interventions | Caffeine citrate 20 mg/kg load and 5 mg/kg/day until 32 weeks post menstrual age. Saline placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Apnea >20 sec with bradycardia (<100 bpm) or cyanosis, use of IPPV, withdrawal for definitive caffeine treatment (open label), tachycardia, hyponatraemia. | |

| Notes | 30 of 54 (56%) followed up to 16‐36 months for neurodevelopmental assessment. Not reported by treatment group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment and outcome assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 0nly 4% missed follow up for apnoea |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Larsen 1995 | This trial compared aminophylline with caffeine citrate without a placebo or no treatment control group |

| Welborn 1989 | Caffeine was compared with placebo in infants born at 37 weeks or less who have at term equivalent age an operation for inguinal hernia repair. The aim being to prevent postoperative apnoea. |

Differences between protocol and review

This review update has increased the range of outcomes.

Contributions of authors

The initial protocol and review were developed by Henderson‐Smart and Steer. This update was done by Henderson‐Smart and approved by Antonio De Paoli.

Sources of support

Internal sources

NSW Centre for Perinatal Health Services Research, University of Sydney, Australia.

Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia.

Department of Paediatrics, Royal Hobart Hospital, Hobart, Australia.

External sources

-

CAP Trial members, Barbara Schmit and Peter Davis, Canada.

Information about the CAP trial methodology and subgroup outcomes

-

Bucher provided additional trial information, Switzerland.

Additional evidence about types of apnoea and bradycardia.

-

Peter Steer, Australia.

Played an important role in earlier versions of this review

Declarations of interest

None

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bucher 1988 {published and unpublished data}

- Bucher HU, Duc G. Does caffeine prevent hypoxaemic episodes in premature infants? A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Pediatrics 1988;147:288‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CAP 2006 {published data only}

- Davis PG, Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Doyle LW, Asztalos E, Haslam R, Sinha S, Tin W, Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group. Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial: benefits may vary in subgroups. Journal of Pediatrics 2010;156:382‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W, Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group. Caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;354:2112‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, Doyle LW, Barrington KJ, Ohlsson A, Solimano A, Tin W, Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity Trial Group. Long‐term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. New England Journal of Medicine 2007;357:1893‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Levitt 1988 {published and unpublished data}

- Levitt GA, Harvey DR. The use of prophylactic caffeine in the prevention of neonatal apnoeic attacks. Unpublished manuscript.

- Levitt GA, Mushin A, Bellman S, Harvey DR. Outcome of preterm infants who suffered neonatal apnoeic attacks. Early Human Development 1988;16:235‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Larsen 1995 {published data only}

- Larsen PB, Brendstrup L, Skov L, Flachs H. Aminophylline versus caffeine citrate for apnea and bradycardia prophylaxis in premature neonates. Acta Paediatrica 1995;84:360‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Welborn 1989 {published data only}

- Welborn LG, Hannallah RS, Fink R, Ruttimann UE, Hicks JM. High‐dose caffeine suppresses postoperative apnea in former preterm infants. Anesthesiology 1989;71:347‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

AAP 2003

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement. Apnea, sudden infant death syndrome, and home monitoring. Pediatrics 2003;111:914‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blanchard 1992

- Blanchard PW, Aranda JV. Pharmacotherapy of respiratory control disorders. In: Beckerman RC, Brouillette RT, Hunt CE editor(s). Respiratory Control Disorders in Infants and Children. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1992:352‐70. [Google Scholar]

Finer 2006

- Finer NN, Higgins R, Kattwinkel J, Martin RJ. Summary proceedings from the apnea‐of‐prematurity group. Pediatrics 2006;117 Pt 2:S47‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 1995

- Henderson‐Smart DJ. Recurrent apnea. In: Yu VYH editor(s). Bailliere's Clinical Paediatrics. Vol. 3, No. 1 Pulmonary Problems in the Perinatal Period and their Sequelae, London: Bailliere Tindall, 1995:203‐22. [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 2008a

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Davis PG. Prophylactic methylxanthine for extubation in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000139] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 2009

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Peter Steer. Methylxanthine treatment for apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000140] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 2010

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Steer P. Caffeine vs theophylline treatment for apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000273] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Samuels 1992

- Samuels MP, Southall DP. Recurrent Apnea. In: Sinclair JC, Bracken MB editor(s). Effective Care of the Newborn Infant. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992:385‐97. [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Henderson‐Smar 2009

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Steer PA. Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 1999

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Steer PA. Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1999, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 2002

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Steer PA. Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henderson‐Smart 2006

- Henderson‐Smart DJ, Steer PA. Prophylactic methylxanthine for prevention of apnea in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000432] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]