Abstract

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), nonmalignant enlargement of the prostate, can lead to obstructive and irritative lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). The pharmacologic use of plants and herbs (phytotherapy) for the treatment of LUTS associated with BPH has been growing steadily. The extract of the African prune tree, Pygeum africanum, is one of the several phytotherapeutic agents available for the treatment of BPH.

Objectives

To investigate the evidence whether extracts of Pygeum africanum (1) are more effective than placebo in the treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH), (2) are as effective as standard pharmacologic BPH treatments, and (3) have less side effects compared to standard BPH drugs.

Search methods

Trials were searched in computerized general and specialized databases (MEDLINE (1966 to 2000), EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Phytodok), by checking bibliographies, and by contacting relevant manufacturers and researchers.

Selection criteria

Trials were eligible if they (1) were randomized (2) included men with BPH (3) compared preparations of Pygeum africanum (alone or in combination) with placebo or other BPH medications (4) included clinical outcomes such as urologic symptom scales, symptoms, or urodynamic measurements. Eligibility was assessed by at least two independent observers.

Data collection and analysis

Information on patients, interventions, and outcomes were extracted by at least two independent reviewers using a standard form. The main outcome measure for comparing the effectiveness of Pygeum africanum with placebo and standard BPH medications was the change in urologic symptoms scale scores. Secondary outcomes included change in urologic symptoms including nocturia and urodynamic measures (peak and mean urine flow, prostate size). The main outcome measure for adverse effects was the number of men reporting adverse effects.

Main results

A total of 18 randomized controlled trials involving 1562 men met inclusion criteria and were analyzed. Only one of the studies reported a method of treatment allocation concealment, though 17 were double blinded. There were no studies comparing Pygeum africanum to standard pharmacologic interventions such as alpha‐adrenergic blockers or 5‐alpha reductase inhibitors. The mean study duration was 64 days (range, 30 to 122 days). Many studies did not report results in a method that permitted meta‐analysis. Compared to men receiving placebo, Pygeum africanum provided a moderately large improvement in the combined outcome of urologic symptoms and flow measures as assessed by an effect size defined by the difference of the mean change for each outcome divided by the pooled standard deviation for each outcome (‐0.8 SD [95% confidence interval (CI), ‐1.4 to ‐0.3 (n = 6 studies)]). Men using Pygeum africanum were more than twice as likely to report an improvement in overall symptoms (RR=2.1, 95% CI = 1.4 to 3.1). Nocturia was reduced by 19%, residual urine volume by 24% and peak urine flow was increased by 23%. Adverse effects due to Pygeum Africanum were mild and comparable to placebo. The overall dropout rate was 12% and was similar between Pygeum Africanum (13%), placebo (11%) and other controls (8%).

Authors' conclusions

A standardized preparation of Pygeum africanum may be a useful treatment option for men with lower urinary symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, the reviewed studies were small in size, were of short duration, used varied doses and preparations and rarely reported outcomes using standardized validated measures of efficacy. Additional placebo‐controlled trials are needed as well as studies that compare Pygeum africanum to active controls that have been convincingly demonstrated to have beneficial effects on lower urinary tract symptoms related to BPH. These trials should be of sufficient size and duration to detect important differences in clinically relevant endpoints and use standardized urologic symptom scale scores.

Plain language summary

Extracts from the African prune tree (Pygeum africanum) may be able to help relieve urinary symptoms caused by enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), enlargement of the prostate gland, is common in older men. An enlarged prostate can interfere with urination, increasing the frequency and urge, or causing problems emptying the bladder. Both surgery and drugs are used to try to treat BPH. However, using herbal medicines to try to relieve the symptoms of BPH is becoming common. Pygeum africanum is one of several popular herbal remedies for BPH. The review found that pygeum africanum is well tolerated, cheaper than many prescription medicines used for BPH, and provides moderate relief from the urinary problems caused by an enlarged prostate.

Background

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a nonmalignant enlargement of the prostate. Symptoms related to BPH are one of the most common problems in older men. Histological evidence of BPH is found in more than 40% of men in their fifties and nearly 90% of men in their eighties (Berry 1984). The majority of men over the age of 60 are considered to have urinary symptoms attributable to BPH. In the United States treatment of BPH accounts for approximately 1.7 million physician office visits (Guess 1992) and results in more than 300,000 prostatectomies annually (McConnell 1994). The proliferative disorder resulting in BPH affects both the stromal and the epithelial portions of the prostate. The enlarging prostate results in the progressive occlusion of the proximal urethra and can result in both obstructive and irritative urinary tract symptoms. The obstructive symptoms of BPH include weak urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete bladder emptying, terminal urine dribbling and abdominal straining (Christensen 1990; Caine 1987). The irritative symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency and nocturia. The treatment goal in the vast majority of patients with BPH is to relieve these bothersome symptoms.

The use of plants and herbs for medicinal purposes (phytotherapy) including treatment of BPH symptoms has been growing steadily in most countries. Usage of plant extracts is common in Europe and is increasing in the United States. Phytotherapeutic agents represent nearly half of the medications dispensed for BPH in Italy, compared with 5% for alpha blockers and 5% for 5‐alpha reductase inhibitors (Di Silverio 1993). In Germany and Austria, phytotherapy is the first‐line treatment for mild to moderate urinary obstructive symptoms and represents > 90% of all drugs prescribed for the treatment of BPH (Buck 1996). In the United States their use has also markedly increased, they are readily available as nonprescription dietary supplements and are often recommended in "natural health food stores or books" for self treatment of BPH symptoms.

Pygeum africanum, an extract from the bark of the African prune tree, has been utilized in Europe since 1969 for the treatment of mild to moderate symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. The mechanism of action of Pygeum africanum remains unclear. In animal models, Pygeum africanum has been shown to have pharmacologic properties that may be beneficial in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. These include modulation of bladder contractility, anti‐inflammatory activity, decreased production of leukotrienes and other 5‐lipoxygenase metabolites (Sidoti 1993; Paubert‐Braquet 1994), inhibition of fibroblast production (Yablonsky 1997; Paubert‐Braquet 1993) effects on adrenal androgens (Thieblot 1977), and restoration of secretory activity of prostate epithelium.

Despite the wide‐spread use of Pygeum africanum uncertainty remains regarding treatment effectiveness and tolerability. A previous qualitative summary did not meet criteria for a systematic review (Andro 1995). This review included results from open‐labelled uncontrolled studies, did not assess study quality nor conduct a quantitative meta‐analysis to estimate the magnitude or statistical significance of treatment efficacy and was sponsored by a manufacturer of Pygeum africanum extract. We conducted a systematic review including a quantitative meta‐analysis, where possible, of the evidence from randomized controlled trials to determine the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of Pygeum africanum, alone or in combination with other herbal agents, for men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Objectives

The aim of our review was to provide a comprehensive overview including a quantitative meta‐analysis of the existing evidence to determine the therapeutic efficacy and the adverse effects of the plant extract Pygeum africanum. Specifically, was Pygeum africanum more effective than placebo in improving the symptoms and/or urodynamics of BPH and as effective as current medical therapies.

Main comparison Determine if Pygeum africanum was more efficacious than placebo in improving validated and standardized urologic symptom scores in men with symptomatic BPH.

Secondary comparisons 1. Determine if Pygeum africanum is more efficacious than placebo in improving urodynamic measurements and urinary symptoms including peak urine flow, mean urine flow, residual urine, prostate size, nocturia, dysuria, and urinary frequency.

2. Determine if Pygeum africanum is as efficacious as active controls in improving urologic symptom scores and urodynamic measures.

3. Determine the adverse effects of Pygeum africanum.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled clinical trials.

Types of participants

Men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia

Types of interventions

Comparison of preparations of Pygeum africanum with placebo or medical therapies for BPH with a treatment duration of at least 30 days.

Types of outcome measures

Urologic symptom scores (Boyarsky, American Urologic Association Score, International Prostate Symptom Score:IPSS); Urodynamic measures (defined as change in peak urine flow (PUF), mean urine flow (MUF), residual urine volume; changes in prostate size (measured in cc); urinary frequency, nocturia (times/per evening); quality of life score (QOL); and overall physician/patient health assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched MEDLINE for 1966 to 2000 using a combination of the March 1996 update of the optimally sensitive search strategy for trials from the Cochrane Collaboration with the MeSH headings "prostatic hyperplasia," "phytotherapy," "plant extracts," "Pygeum africanum," "Tadenan", "Docosonal", and "Pigenil" including all subheadings (Dickersin 1994). A search of EMBASE, years 1974 to 1999 was done by using a similar approach to that for Medline. We also searched the private database Phytodok, Munich Germany, and the Cochrane Library, including the database of the Cochrane Prostate Diseases and Urologic Malignancies Review Group and the Cochrane Field for Complementary Medicine. Reference lists of all identified trials and previous reviews were searched for additional trials. The manufacturer and authors were contacted for missing data or additional trials. There were no language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility: Two investigators (AI and RM) independently determined if identified studies met inclusion criteria.

Extraction: The following data were extracted from each included study: study characteristics, demographics of patients, enrollment criteria, outcomes, adverse effects, and number and reasons for dropout. Missing or additional information was sought from authors/sponsors. Included and excluded studies as well as extracted data were reviewed and discrepancies resolved by discussion and consensus.

Assessment of methodological quality: Study quality was assessed using the method outlined by Schulz and colleagues (Schulz 1995) assigning 1 to poorest quality and 3 to best quality: 1 = trials in which concealment was inadequate (e.g. alteration or reference to case record numbers or to dates of birth); 2 = trials in which the authors either did not report an allocation concealment approach at all or reported an approach that did not fall into one of the other categories; and 3 = trials deemed to have adequate measures to conceal allocations (e.g. central randomization; numbered or coded bottles or containers; drugs prepared by the pharmacy; serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes etc. that contained elements convincing of concealment).

Summarizing results of primary studies: Outcomes: The mean urologic symptom score (points), peak and mean urine flow (mL/sec), residual urine volume (mL), prostate size (cc), frequency (% men reporting), urgency (% men reporting), dysuria (% men reporting) and nocturia (# times). The number and percent of men reporting specific side effects and/or withdrawing from the study.

Meta‐analysis: Because no common outcome measure was available from all eighteen studies we utilized two methods for combining data. One method, reported by Saint 1995, assesses treatment effect size for continuous variables by the difference of the mean change for each outcome divided by the pooled standard deviation for each outcome when trials report different outcome measures of effectiveness (e.g. symptom scale scores, nocturia, peak urine flow rate). The second method calculates a summary measure for individual outcomes using studies that provide similar outcome measures and utilizes standard meta‐analytic techniques described below.

For determining effect size we utilized the outcome that was determined a priori to be most clinically significant (order of clinical importance: symptom scale score > nocturia > peak urine flow > residual urine volume). One outcome from each study was then transformed into units of standard deviations (SD), giving a comparable effect size for each study. The study‐specific overall effect size was the difference in mean outcome for the Pygeum africanum and placebo groups, divided by the pooled SD of the outcome measure. The summary effect size across studies was calculated as the weighted average of the study‐specific effect size, with weights equal to the inverse of the estimated variance of each using standard meta‐analytic methodology as developed by DerSimonian and Laird (DerSimonian 1986; Laird 1990). We used the same definition of standardized effect sizes to look at individual and comparable continuous outcomes when available (nocturia and peak urine flow). The statistical significance of the summary effect size was assessed by comparing it with the standard normal distribution. A scale for effect size suggested by Cohen 1988 was used with 0.8 reflecting a large effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.2 a small effect.

Additional meta‐analyses considered the difference between Pygeum africanum treatment and the control treatment in the mean change from baseline to end of follow‐up for each separate continuous outcome. For those studies not reporting mean change scores and the corresponding standard errors, the standard errors for the mean change scores were approximated using the standard errors of the outcomes at baseline and followup. The approximation used the methodology reported by Laird 1990 and Lau 1996 based on the correlation between outcomes. Analyses were conducted for three different assumed values for this correlation (0.25, 0.50, 0.75). This approach was taken to examine the sensitivity of the results to the value of this unknown parameter. Weighted mean differences were calculated using the methodology outlined above. There were no qualitative differences between the meta‐analysis results for the three assumed correlation values; we present here the results for the assumed correlation of 0.50. For categorical outcome measures weighted relative risks and 95% CI were calculated using standard meta‐analytic techniques.

Chi squared tests were used for analysis of bivariate comparisons (adverse events and dropouts) using simple pooling of data. To assess the percentage of patients having improvement in urologic symptoms, a modified intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed (i.e., men who dropped out or were lost to follow‐up were considered to have had worsening symptoms) (Lavori 1992). The denominator for the modified intention‐to‐treat analysis included the number randomized to treatment at baseline, and the numerator included the number completing the trial and showing improvement. A test for heterogeneity was calculated according to standard formulas (DerSimonian 1986; Saint 1995) and a random effects model utilized for all summary estimates.

Results

Description of studies

The combined search strategies identified 31 trials; 18 met inclusion criteria. None were conducted in the United States and 12 were reported in a non‐English language [German (1), Italian (10), French (2)]. Fourteen trials were excluded because they did not include a control group (Anonymous 1973; Breza 1998; Diz 1973; Grasset 1974; Greiner 1970; Grévy 1970; Guilland‐Vallée 1970; Guillemin 1970; Huet 1970; Lange 1970; Lhez 1970; Martínez‐Piñeiro '73; Robineau 1976; Rometti 1970). The majority of studies examined Pygeum Africanum alone versus placebo alone (n = 11) (Barlet 1990; Bassi 1987; Blitz 1985; Bongi 1972; Donkervoort 1977; Dufour 1984; Frasseto 1986; Maver 1972; Ranno 1986; Rizzo 1985). Two trials comparing Pygeum africanum against an anti‐inflammatory drug (Gagliardi 1983; Rigatti 1983). One study comparing Pygeum Africanum to placebo included an additional treatment arm of Pygeum africanum in combination with a steroid (Giacobini 1986). Two studies compared Pygeum africanum alone to one or more herbal agents and versus placebo (Barth 1981; Mandressi 1983), one trial compared Pygeum africanum to another herbal agent (Dutkiewicz 1996), one trial compared different daily dosage forms of Pygeum africanum (Chatelain 1999), and one trial compared two different doses of Pygeum africanum in combination with another herbal extract (Krzeski 1993). None of the "active comparison" arms have been conclusively demonstrated to be effective in treating symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia.

A total of 1562 participants were randomized in the 18 trials. The mean treatment duration was 64 ± 21.1 days and ranged from 30 to 122 days. The majority of the studies (n = 14; participants = 1103) utilized a standardized extract of Pygeum africanum. The doses of Pygeum africanum ranged between 75 to 200 mg per day. Of the placebo controlled trials 1 utilized a dose of Pygeum africanum equal to 75 mg per day, 7 utilized a dose of 100 mg per day, 4 utilized a dose of 200 mg/day and one did not report the dosage (Dutkiewicz 1996). For studies that provided baseline data, results did not vary between treatment arms and were consistent with men typically presenting with moderate benign prostatic hyperplasia. The mean age was 66.± 6.9 years (9 studies, n = 845, range 42 to 89); nocturia = 3 ± 0.7 times per evening (4 studies, n = 413); peak urine flow = 12 ± 3.6 mL/sec (5 studies, n = 416); residual urine volume = 40 ± 25.6 mL (2 studies, n = 284). Not all studies could be pooled because of differences in reporting methods. Of the 13 trials of Pygeum africanum versus placebo identified, 12 reported a beneficial effect of Pygeum africanum on at least one measure of effectiveness: overall symptoms, nocturia, peak urine flow or residual volume. Only one trial demonstrated no difference between Pygeum africanum and placebo (Rizzo 1985). This trial assessed the effect of Pygeum africanum on nocturia, peak urine flow and overall symptom change in 20 men over 12 weeks. None of the trials showed an effect of Pygeum africanum worse then placebo or "active control."

Risk of bias in included studies

Only one of the studies reported a method for concealment of treatment allocation (score = 2) but 17 of the 18 studies were double‐blinded. Most studies did not provide baseline patient information nor provide clinically relevant baseline or outcomes data in a standardized fashion. No placebo‐controlled studies utilized standardized, validated symptom scales (the outcome measure of greatest clinical significance). There was no information on patient race, comorbid conditions, prostate size or standardized/validated urologic symptom scale scores. All studies were of short treatment duration with none having a follow up greater than four months.

Effects of interventions

Summary Effect Sizes: Six studies involving 474 participants (54% of all participants enrolled in placebo controlled trials) could be pooled to provide a weighted estimate of effectiveness (Barlet 1990; Bongi 1972; Giacobini 1986; Mandressi 1983; Maver 1972; Rizzo 1985). All involved Pygeum africanum alone versus placebo, and five utilized a standardized preparation of Pygeum africanum. The overall summary effect size was ‐0.8 SD (95% CI ‐1.4 to ‐0.3) indicating a statistically significant large improvement with Pygeum africanum. The summary effect size from three studies that provided data on nocturia was ‐0.8 SD (95% CI ‐1.4 to ‐0.1) (Barlet 1990; Bongi 1972; Mandressi 1983). This indicates that Pygeum africanum resulted in a statistically significant moderate to large improvement in nocturia. Summary results from the four studies providing data on peak urine flow demonstrated a mean effect size of 0.7 SD (95% CI 1.3 to 0.0) indicating a moderate effect on peak urine flow (Barlet 1990; Giacobini 1986; Maver 1972; Rizzo 1985).

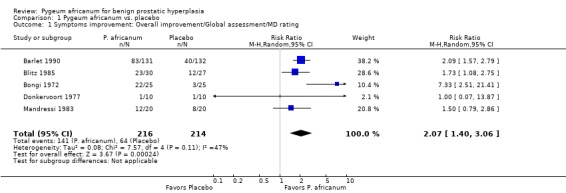

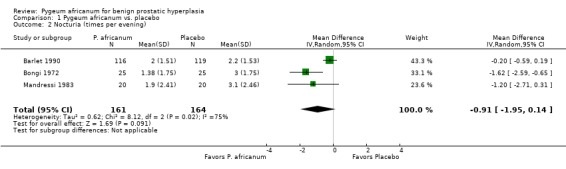

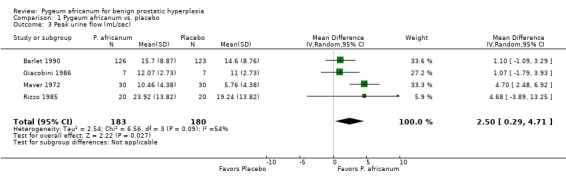

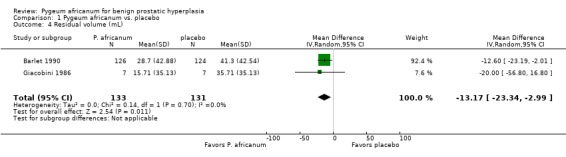

Urinary symptoms and flow measures: Consistent with the results seen in the summary effect sizes, Pygeum africanum improved specific urinary symptoms and flow measures. In 5 double‐blind trials involving 430 participants, men receiving Pygeum africanum were more than twice as likely to be rated by their physician as having overall improvement in symptoms compared to men taking placebo (65% vs. 30%; RR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.4 to 3.1) (Barlet 1990; Blitz 1985; Bongi 1972; Donkervoort 1977; Mandressi 1983). Pygeum africanum reduced nocturia compared to placebo by 19% (weighted mean difference (WMD) = ‐ 0.9 times per evening; 95% CI = ‐2.0 to 0.1) though this did not reach statistical significance (Barlet 1990; Bongi 1972; Mandressi 1983). Pygeum africanum also increased peak urine flow compared to placebo by 23%, WMD = 2.5 mL/sec (95% CI = 0.3 to 4.7) (Barlet 1990; Giacobini 1986; Maver 1972; Rizzo 1985). Pygeum africanum reduced residual urine volume by 24% (WMD = ‐13 mL; 95% CI = ‐23.3 to ‐3.0) (Barlet 1990; Giacobini 1986).

To assess for publication bias we constructed funnel plots from published trials providing data for calculation of summary effect size, overall symptom improvement, nocturia and peak urine flown. The few studies available for funnel plot analysis make assessment difficult and do not provide clear evidence for or against publication bias.

Adverse Events: All studies provided information on the percentage of men who dropped‐out or were lost to follow up, potentially the most reliable indicator of tolerability. The mean percentage of participants who dropped out was 12% (n = 179), ranged from 0% to 45% and did not differ between Pygeum africanum (13%), placebo (11%) and other controls (8%) (P = 0.4 vs placebo and P=0.5 vs other control). Three studies (two placebo controlled) had drop out rates > 20%. The reason for the high drop out rate was not reported but two of the trials (Barth 1981; Chatelain 1999) indicated that adverse effects were "infrequent and mild" in participants completing the trial. None of these three trials reported outcome data in a method suitable for incorporation into the effect size analyses. Thirteen of the eighteen studies provided information on specific adverse events. Adverse events due to Pygeum africanum were generally mild in nature and comparable in frequency to placebo. The most frequently reported adverse events were gastrointestinal and occurred among seven men in five trials.

Discussion

This systematic review summarizes the available evidence from randomized controlled trials regarding the efficacy and tolerability of Pygeum africanum for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms attributable to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Our results suggest that Pygeum africanum improves urinary symptoms and flow measures and that the point estimate for the effect size is moderate in magnitude. Because of the diversity of outcome measures, a summary estimate of the effect of Pygeum africanum was based on units of SD available from 6 studies involving 474 participants. This method is useful for determining if an overall benefit exists but only indicates whether the overall effect is of small, moderate or large magnitude. Our analyses of individual effect sizes for nocturia and peak urinary flow indicate that improvement of comparable magnitude occurred in both urinary symptoms and flow measures.

Summary risk ratios and weighted mean differences comparing Pygeum africanum to placebo for overall symptoms, peak urine flow, and residual urine volume demonstrated a statistically significant improvement as well as a trend towards improvement for nocturia. These findings are considered clinically significant, comparable to other widely used treatment options and consistent with the results obtained utilizing effect sizes. The results from individual trials demonstrated that all but one study noted an improvement with Pygeum africanum for symptoms attributable to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Additionally, Pygeum africanum was well tolerated with the drop out rate for men receiving Pygeum africanum not different than for men receiving placebo.

While studies utilized different quantities, dosing intervals and preparations of Pygeum africanum the majority of studies utilized a standardized extract of Pygeum africanum at a dose of 100 to 200 mg per day. Five of the six studies providing data for summary estimates of effect size utilized the standardized extract of Pygeum africanum. All summary efficacy data were derived from placebo‐controlled, double blind studies utilizing a "noncombination" source of Pygeum africanum. This suggests that a standardized preparation of Pygeum africanum is associated with the observed improvement in symptoms and flow measures.

No study was conducted in the United States and many studies did not report means and standard deviations making completion of a quantitative review difficult. There was no information provided to determine if Pygeum africanum prevented long‐term complications of benign prostatic hyperplasia such as acute urinary retention, renal insufficiency or the need for surgical intervention. No studies compared Pygeum africanum with medical interventions of demonstrated effectiveness including alpha adrenergic blockers and 5‐alpha reductase inhibitors. The "active controls" used in the studies have not been convincingly demonstrated to have beneficial effects.

A possible source of bias is that outcomes included in the effect size calculation could have been selected to favor Pygeum africanum. However, we ranked outcome measures for inclusion in the effect size calculation prior to data abstraction and analysis. Furthermore, effectiveness was consistently observed in all but one of the studies and regardless of whether the results were reported as physician rating of patient's global symptom improvement (n = 6 trials; 430 patients); nocturia (n = 3 trials; 325 participants); peak urine flow (n = 4 trials; 363 participants); or residual volume (n = 4 trials; 264 participants). An additional source of bias could result from failure to publish small negative studies (publication bias) or outcomes that were not favorably affected. This would enhance the summary effect size estimates and could contribute to our finding that only one out of seventeen reported studies was negative. Funnel plots were constructed to assess for publication bias, however few studies could be included in the plot construction.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The overall standardized effect size and the summary improvement in global symptoms, nocturia, peak urine flow and residual urine volume suggests that Pygeum africanum is effective in men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. This benefit is of modest size and appears to be clinically significant. Pygeum africanum is well tolerated and costs less than most prescription medications. A standardized preparation of Pygeum africanum, may be a useful treatment option, at least in the short term, for men with lower urinary symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Implications for research.

Additional placebo‐controlled trials are needed as well as studies that compare Pygeum africanum to active controls that have been convincingly demonstrated to have beneficial effects on lower urinary tract symptoms related to BPH. Future trials should be of sufficient size and duration (e.g. > 6 months) to detect important differences in clinically relevant endpoints and use standardized urologic symptom scale scores.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 2, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 November 1997 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review is out of date and has been withdrawn.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Maurizio Tiso for his work in translating and abstracting data from the Italian language studies.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pygeum africanum vs. placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Symptoms improvement: Overall improvement/Global assessment/MD rating | 5 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.07 [1.40, 3.06] |

| 2 Nocturia (times per evening) | 3 | 325 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.91 [‐1.95, 0.14] |

| 3 Peak urine flow (mL/sec) | 4 | 363 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.50 [0.29, 4.71] |

| 4 Residual volume (mL) | 2 | 264 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐13.17 [‐23.34, ‐2.99] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pygeum africanum vs. placebo, Outcome 1 Symptoms improvement: Overall improvement/Global assessment/MD rating.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pygeum africanum vs. placebo, Outcome 2 Nocturia (times per evening).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pygeum africanum vs. placebo, Outcome 3 Peak urine flow (mL/sec).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pygeum africanum vs. placebo, Outcome 4 Residual volume (mL).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Barlet 1990.

| Methods | Multicentre study. Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=263 European men with symptomatic BPH, age > 50. Age range 50‐85, mean 67. Lost to follow‐up: 8 (3%). | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=132). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg twice daily (n=131). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Overall improvement in symptoms (MD/subject ‐ rating); Nocturia; peak urine flow; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Barth 1981.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=215 European men with symptomatic BPH, age > 50. Lost to follow‐up: 67 (31%). | |

| Interventions | Control 1: placebo (n=46). Treatment 2: P. africanum extract (Docosanol) 100 mg daily (n=50). Control 2: Sitosterin 30 mg (n=34). Treatment 2: P. africanum extract (Docosanol) 100 mg daily (n=37). Control 3: ERU* 300 mg (n=24). Treatment 3: P. africanum extract (Docosanol) 100 mg daily (n=24). Treatment duration: 8 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; peak urine flow; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bassi 1987.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=40 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Mean age: 67 years. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=20). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Pigenil) 100 mg daily (n=20). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; peak urine flow. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Blitz 1985.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=57 French men with symptomatic BPH. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Overall improvement in symptoms. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Bongi 1972.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=50 Italian men with symptomatic BPH, residual volume < 200 ml. Age range: 49‐84. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 75 mg daily Treatment duration: 60 days | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; residual volume. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Chatelain 1999.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=209 French men with symptomatic BPH, age > 50, IPSS 10 or >, PUF < 15 ml/s, residual volume < 150 ml. Mean age: 66 years. Lost to follow‐up: 26 (11.1%). | |

| Interventions | Treatment 1: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 50 mg x 2 daily (n=101). Treatment 2: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=108). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Symptom score (IPSS); peak urine flow. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | 235 men were randomized, 223 completed the comparative phase, but only 209 men were valid for per‐protocol analysis. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Donkervoort 1977.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=20 Dutch men with symptomatic BPH. Lost to follow‐up: 4 (20%). | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 75 mg daily Treatment duration: 12 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Overall improvement in symptoms; Nocturia; peak urine flow. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dufour 1984.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=120 French men with symptomatic BPH not in need of surgery. Lost to follow‐up: 56 (47%). | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=60). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=60). Treatment duration: 6 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dutkiewicz 1996.

| Methods | Single‐site study. Double blinded: no. Randomization: unclear Patients not blinded: Providers not blinded: Lost to follow‐up: none | |

| Participants | N=89 Polish men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 50‐68. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: Cernilton 2 tablets three times daily x 2 weeks followed by 1 tablet three times daily up to 4 months (n=51). Treatment: Tadenan 2 tablets twice daily (38). Treatment duration: 24 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Obstructive symptom score Irritative symptom score; peak urine flow; residual volume; prostate volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | Exclusions: No details provided. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Frasseto 1986.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=20 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 50‐84, mean 67 years. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=10). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 75 mg daily (n=10). Treatment duration: 60 days | |

| Outcomes | "Dysuric symptoms" (nocturia, pollachiuria, reduced strenght of flux). Adverse events. | |

| Notes | Prostate size evaluated by ultrasonography. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gagliardi 1983.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=40 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 50‐84, mean 67 years. Lost to follow‐up: 1 (2.5%). | |

| Interventions | Control: Anti‐inflammatory (not identified) (n=20) Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=20). Treatment duration: 30 days. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Giacobini 1986.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=21 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 48‐70. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=7). Treatment 1: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 200 mg daily (n=7). Treatment 1: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 200 mg daily + medroxyprogesterone acetate (Farlutal) (n=7). Treatment duration: 90 days. | |

| Outcomes | Peak flow rate; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Krzeski 1993.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=134 Polish men with symptomatic BPH (> 1 symptom). Age range: 53‐84, mean 64 years. Lost to follow‐up: 14.2%. | |

| Interventions | Treatment 1: P. africanum 25 mg + Urtica dioica 300 mg (n=67). Treatment 2: half dose of above (n=67). Treatment duration: 8 weeks. | |

| Outcomes | Overall improvement in symptoms; nocturia; peak flow rate; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Mandressi 1983.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. Randomization: Identical packaging | |

| Participants | N=60 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 50‐80. | |

| Interventions | Control 1: placebo (n=20). Control 2: Permixon 320mg daily (n=20). Treatment: Pygeum africanum extract Average (n=20). Treatment duration: 30 days. Lost to follow‐up: unclear | |

| Outcomes | Patient self‐rating of "Dysuric symptoms" (pain on voiding) Nocturia. Adverse events. Dropouts due to side effects: none | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Maver 1972.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=60 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 55‐85, mean 66 years. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=30). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=30). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ranno 1986.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=39 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Mean age: 70 years. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=19). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=20). Treatment duration: 2 months. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; peak urine flow. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Rigatti 1983.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=49 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: NSAID (n=25). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg daily (n=24). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Rizzo 1985.

| Methods | Double blinded: yes. | |

| Participants | N=40 Italian men with symptomatic BPH. Age range: 42‐74, mean 62 years. Lost to follow‐up: 0. | |

| Interventions | Control: placebo (n=20). Treatment: P. africanum extract (Tadenan) 100 mg twice daily (n=20). Treatment duration: 60 days. | |

| Outcomes | Nocturia; peak urine flow; residual volume. Adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

* Extract of Rad. urticae

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Anonymous 1973 | No control group. |

| Breza 1998 | No control group. |

| Diz 1973 | No control group. |

| Grasset 1974 | No control group. |

| Greiner 1970 | No control group. |

| Grévy 1970 | No control group. |

| Guilland‐Vallée 1970 | No control group. |

| Guillemin 1970 | No control group. |

| Huet 1970 | No control group. |

| Lange 1970 | No control group. |

| Lhez 1970 | No control group. |

| Martínez‐Piñeiro '73 | No control group. |

| Robineau 1976 | No control group. |

| Rometti 1970 | No control group. |

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development (HSRD) Office, USA.

Minneapolis/VISN‐13 Center for Chronic Diseases Outcomes Research (CCDOR), USA.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Barlet 1990 {published data only}

- Barlet A, Albrecht J, Aubert A, Fischer M, Grof F, Grothuesmann HG, Masson JC, Mazeman E, Mermon R, Reichelt H, Schonmetzler F, Suhler A. Wirksamkeit eines extraktes aus Pygeum africanum in der medikamentosen therapie von miktionsstorungen infolge einer benignen prostatahyperplasie: bewertung objektiver und subjektiver parameter. Wien Klin Wochenschr 1990;102(22):667‐73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Barth 1981 {published data only}

- Barth H. Non hormonal treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy. Clinical evaluation of the active extract of Pygeum africanum. Proceedings of Symposium on Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy; October 3, 1981;Paris:45‐8. [Google Scholar]

Bassi 1987 {published data only}

- Bassi P, Artibani W, Luca V, Zattoni F, Lembo A. Estratto standardizzato di pygeum africanum nel trattamento dell'ipertrofia prostatica benigna. Studio clinico controllato versus placebo. Minerva Urol Nefrol 1987;39(1):45‐50. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blitz 1985 {published data only}

- Blitz M, Garbit JL, Masson JC, Shuler A, Vacant J. Etude controlee de l'efficacite d'un traitement medical sur des sujets consultant pour la premiere fois pour un adenome de la prostate. Lyon Mediterr Med 1985;21:11. [Google Scholar]

Bongi 1972 {published data only}

- Bongi G. Il Tadenan nella terapia dell'adenoma prostatico. Studio anatomo‐clinico. Minerva Urol 1972;24:124‐38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chatelain 1999 {published data only}

- Chatelain C, Autet W, Brackman F. [Comparison of once and twice daily dosage forms of Pygeum africanum extract in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized, double‐blind study, with long term open label extension]. Urology 1999;54(3):473‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Donkervoort 1977 {published data only}

- Donkervoort T, Sterling A, Ness J, Donker PJ. A clinical and urodynamic study of Tadenan in the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy. Eur Urol 1977;3:218‐25. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dufour 1984 {published data only}

- Dufour B, Choquenet C, Revol M, Faure G, Jorest R. Etude controlee des effets le l'extrait de Pygeum africanum sur les symptomes fonctionnels de l'adenome prostatique. Ann Urol 1984;18(3):193‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dutkiewicz 1996 {published data only}

- Dutkiewicz S. Usefulness of Cernilton in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int Urol Nephrol 1996;28(1):49‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frasseto 1986 {published data only}

- Frasseto G, Bertoglio S, Mancuso S, Ervo R, Mereta F. Studio sull'efficacia e sulla tollerabilita del Tadenan 50 in pazienti affeti da ipertrofia prostatica. Prog Med 1986;42:49‐53. [Google Scholar]

Gagliardi 1983 {published data only}

- Gagliardi V, Apicella F, Pino P, Falchi M. [Terapia medica dell'ipertrofia prostatica. Sperimentazione clinica controllata]. Arch Ital Urol Nefrol Andrologia 1983;55:51‐69. [Google Scholar]

Giacobini 1986 {published data only}

- Giacobini S, Heland M, Natale G, Gentile V, Bracci U. Valutazione clinica e morfo‐funzionale del trattamento a doppio cieco con placebo. Tadenan 50 e Tadenan 50 associato a Farlutal nei pazienti con ipertrofia prostatica benigna. Antologia Medica Italiana 1986;6:1‐10. [Google Scholar]

Krzeski 1993 {published data only}

- Krzeski T, Kazon M, Borkowski A, Witeska A, Kuczera J. Combined extracts of Urtica dioica and Pygeum africanum in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: double‐blind comparison of two doses. Clin Ther 1993;15(6):1011‐20. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mandressi 1983 {published data only}

- Mandressi S, Tarallo U, Maggioni A, Tombolini P, Rocco F, Quadraccia. Medical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: efficacy of the extract of Serenoa repens (Permixon) compared to that of the extract of Pygeum africanum and a placebo. Urologia 1983;50(4):752‐8. [Google Scholar]

Maver 1972 {published data only}

- Maver A. Medical treatment of fibroadenomatous hypertrophy of the prostate with a new plant substance. Minerva Medica 1972;63(37):2126‐36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ranno 1986 {published data only}

- Ranno S, Minaldi G, Viscusi G, Marco G, Consoli C. Efficacia e tollerabilita del trattamento dell'adenoma prostatico con Tadenan 50. Prog Med 1986;42:165‐9. [Google Scholar]

Rigatti 1983 {published data only}

- Rigatti P, Zennaro F, Fraschini O, Oxilia A. L'impegio del Tadenan nell'adenoma prostatico. Ricerca clinica controllata. Atti Acad Med Lomb 1983;38:1‐4. [Google Scholar]

Rizzo 1985 {published data only}

- Rizzo M, Tosto A, Paoletti MC, Raugei A, Favini P, Nicolucci A, Paolini R. Terapia medica dell'adenoma della prostata: Valutazione clinica comparativa tra estratto di Pygeum africanum ad alte dosi e placebo. Farmacia Terapia 1985;2:105‐10. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Anonymous 1973 {published data only}

- [Investigation terapeutica con Pronitol]. Clinica Rural 1973;8:56‐62. [Google Scholar]

Breza 1998 {published data only}

- Breza J, Dzurny O, Borowka A, et al. [Efficacy and acceptability of Tadenan (Pygeum Africanum extract) in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): a multicentre trial in Central Europe]. Curr Med Res Opin 1998;14(3):127‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diz 1973 {published data only}

- Diz M. [Pygeum Africanum in urologia]. NEJM (Spanish ed.) 1973;7:35‐8. [Google Scholar]

Grasset 1974 {published data only}

- Grasset D. [Expérimentation clinique du Tadenan dans traitement de l'adénome prostatique]. Méd Praticienne 1974;537:87‐91. [Google Scholar]

Greiner 1970 {published data only}

- Greiner G, Ballof. [Résultats cliniques de l'expérimentation du Tadenan]. Méd Interne 1970;5:10‐12. [Google Scholar]

Grévy 1970 {published data only}

- Grévy A, Favre J‐P. [Nouvelle thérapeutique dans les troubles mictionnels d'origine prostatique ou cervicale chez l'homme]. Méd Interne 1970;5:3‐5. [Google Scholar]

Guilland‐Vallée 1970 {published data only}

- Guilland‐Vallée Y. [Expérimentation clinique du V1326 (Tadenan)]. Méd Interne 1970;5:7‐9. [Google Scholar]

Guillemin 1970 {published data only}

- Guillemin P. [Essai clinique du V1326, ou Tadenan, vis‐à‐vis de l'adénome prostatique]. Méd Praticienne 1970;386:75‐6. [Google Scholar]

Huet 1970 {published data only}

- Huet JA. [Les affections de al prostate sujétion du troisième age]. Méd Interne 1970;5:405‐8. [Google Scholar]

Lange 1970 {published data only}

- Lange J, Muret P. [Expérimentation clinique du V1326 dans les troubles prostatiques]. Bordeaux Méd 1970;11:2807‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lhez 1970 {published data only}

- Lhez A, Leguevague G. [Essai clinique d'un nouveau complexe lipido‐stérolique d'origine végétale dans de traitment de l'adénome prostatique]. Vie Med 1970;39:5399‐5404. [Google Scholar]

Martínez‐Piñeiro '73 {published data only}

- Martinez‐Piñeiro JA, Armero H. [Resultados de la terapeutica de las affecciones prostaticas con V1326]. NEJM (Spanish ed.) 1973;7:29‐34. [Google Scholar]

Robineau 1976 {published data only}

- Robineau Y, Pelissier E. [Applications thérapeutiques du Pygeum Africanum (Tadenan) chez 50 malades de notre service ayant consulté pour des troubles urinaires en relation directe avec un adénome prostatique]. Diagnostics 1976;175:115‐20. [Google Scholar]

Rometti 1970 {published data only}

- Rometti A. [Traitement médicale de l'adénome prostatique par le V13‐26]. Provence Médicale 1970;38:49‐51. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Andro 1995

- Andro MC, Riffaud JP. Pygeum Africanum extract for the treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: A review of 25 years of published experience. Cur Ther Res 1995;56:796‐817. [Google Scholar]

Berry 1984

Buck 1996

- Buck AC. Phytotherapy for the prostate. Br J Urol 1996;78(3):325‐326. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Caine 1987

- Caine M, Schuger L. The "capsule" in benign prostatic hypertrophy. US Department of Health and Human Services, NIH Publication No. 87‐2881. 1987; Vol. 221.

Christensen 1990

- Christensen MM, Bruskewitz RC. Clinical manifestations of benign prostatic hyperplasia and the indications for therapeutic intervention. Urol Clin North Am. 1990; Vol. 17:509‐516. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed]

Cohen 1988

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Edition. Hillsdale, NH: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc, 1988. [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Di Silverio 1993

- Silverio F, Flammia GP, Sciarra A, Caponera M, Mauro M, Buscarini M, Tavani M, D'Eramo G. Plant extracts in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Minerva Urol Nefrol 1993;45:143‐149. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dickersin 1994

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;312:944‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guess 1992

Laird 1990

- Laird N, Mosteller F. Some statistical methods for combining experiment results. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1990;6:5‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lau 1996 [Computer program]

- Lau J. [Meta‐Analyst]. Version Version 0.99. Boston, Mass: New England Medical Center, 1996.

Lavori 1992

- Lavori PW. Clinical trials in psychiatry: should protocol deviation censor patient data?. Neuropsychopharmacology 1992;6:39‐63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McConnell 1994

- McConnell JD, Barry MJ, Bruskewitz RC. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: Diagnosis and treatment. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 8, AHCPR Publication No. 94‐0582. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1994. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed]

Oesterling 1995

- Oesterling JE. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical and minimally invasive treatment options. N Engl J Med 1995;332(2):99‐109. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paubert‐Braquet 1993

- Paubert‐Braquet M, Momboisse JC, Boichot‐Lagente E, et al. Pygeum Africanum extract (Tadenan) inhibits b‐FGF and EGF‐induced proliferation of 3T3 fibroblasts. Pharmacologist 1993;35:173. [Google Scholar]

Paubert‐Braquet 1994

- Paubert‐Braquet M, Cave A, Hocquemill R, et al. Effect of Pygeum Africanum extract on A23187‐stimulated production of lipoxygenase metabolite from human polymorphonuclear cells. Lipid Mediators 1994;9:285‐290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paubert‐Braquet 94

- Paubert‐Braquet M, Monboisse JC, Servant‐Saez N, Serikoff A, Cave A, Hocquemiller R, Cupont C, Fourneau C, Borel JP. Inhibition of bFGF and EGF‐induced proliferation of 3T3 fibroblasts by extract of Pygeum africanum (Tadenan). Biomed Pharmacother. Biomed Pharmacother 1994;48(Suppl 1):43‐47. [Google Scholar]

Saint 1995

- Saint S, Bent S, Vittinghoff E, Grady D. Antibiotics in Chronic Obstructive Disease Excacerbatons: A Meta‐Analysis. JAMA 1995;273:957‐60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schulz 1995

- Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sidoti 1993

- Sidoti C, Hedef N, Delacroix D, et al. [Inhibitory effect of Pygeum Africanum extract (Tadenan) on A23187‐stimulated lipoxygenase metabolite production from human polymorphonuclear cells]. Pharmacologist 1993;35:173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thieblot 1977

- Thieblot L, Grizard G, Boucher D. [Etude du V1326, principe actif d'un extrait d'ecorce de plante Africaine Pygeum Africanum sur l'axe hypohyso‐genito surrenalien du rat]. Therapie 1977;32:99‐110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yablonsky 1997

- Yablonsky F, Nicolas V, Riffaud JP, Bellamy F. Antiproliferative effect of Pygeum africanum extract on rat prostatic fibroblasts. J Urol 1997;157:2381‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]