Abstract

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common health care problem. Recurrent UTI (RUTI) in healthy non‐pregnant women is defined as three or more episodes of UTI during a twelve month period. Long‐term antibiotics have been proposed as a prevention strategy for RUTI.

Objectives

To determine the efficacy (during and after) and safety of prophylactic antibiotics used to prevent uncomplicated RUTI in adult non‐pregnant women.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (from 1966), EMBASE (from 1980), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL in The Cochrane Library) and reference lists of retrieved articles.

Selection criteria

Any published randomised controlled trial where antibiotics were used as prophylactic therapy in RUTI.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. Statistical analyses were performed using the random effects model and the results expressed as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

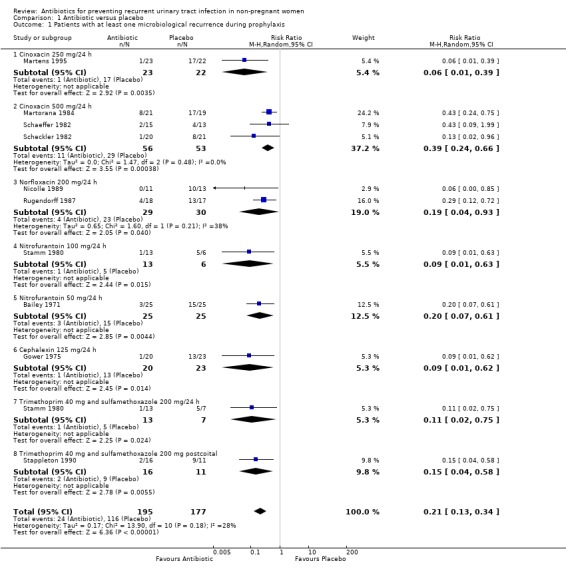

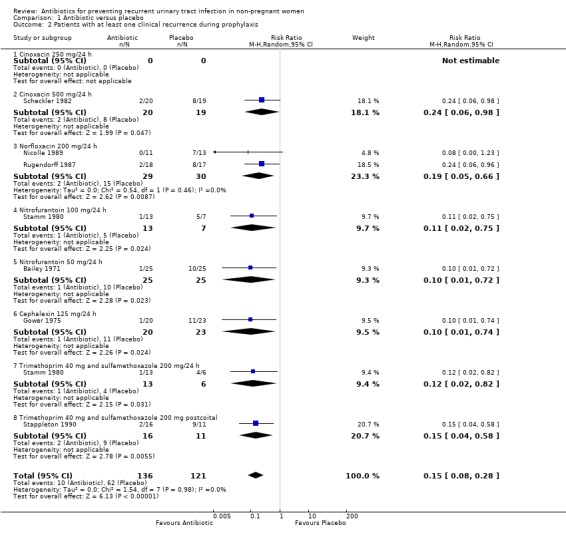

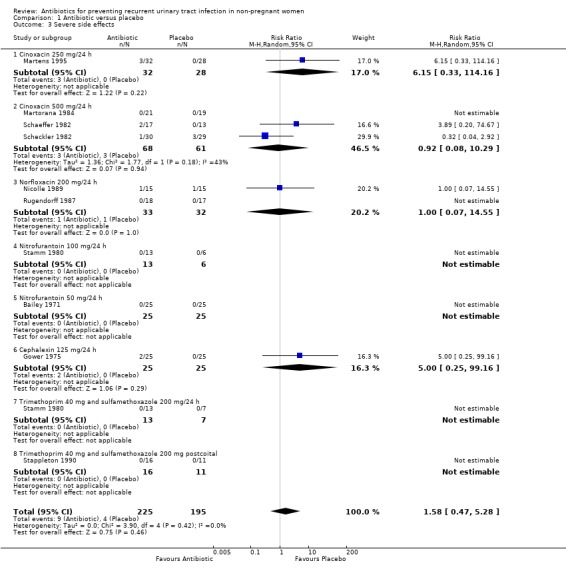

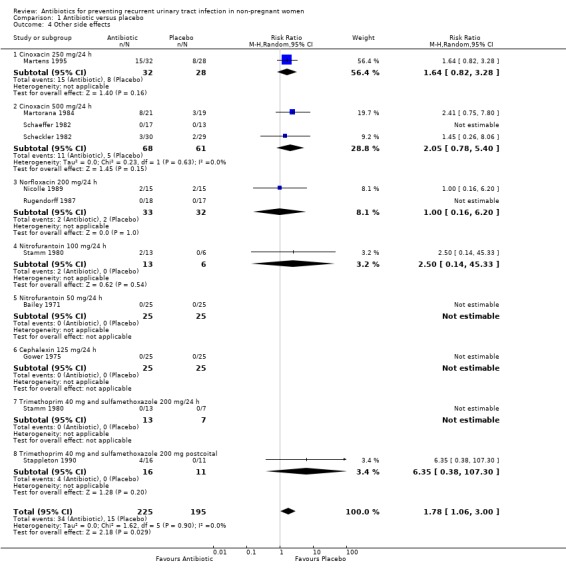

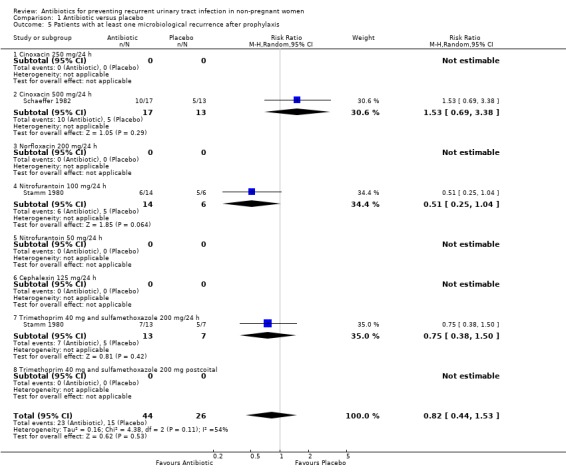

Nineteen studies involving 1120 women were eligible for inclusion. Antibiotic versus antibiotic (10 trials, 430 women): During active prophylaxis the rate range of microbiological recurrence patient‐year (MRPY) was 0 to 0.9 person‐year in the antibiotic group against 0.8 to 3.6 with placebo. The RR of having one microbiological recurrence (MR) was 0.21 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.34), favouring antibiotic and the NNT was 1.85. For clinical recurrences (CRPY) the RR was 0.15 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.28). The NNT was 1.85. The RR of having one MR after prophylaxis was 0.82 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.53). The RR for severe side effects was 1.58 (95% CI 0.47 to 5.28) and for other side effects the RR was 1.78 (CI 1.06 to 3.00) favouring placebo. Side effects included vaginal and oral candidiasis and gastrointestinal symptoms.

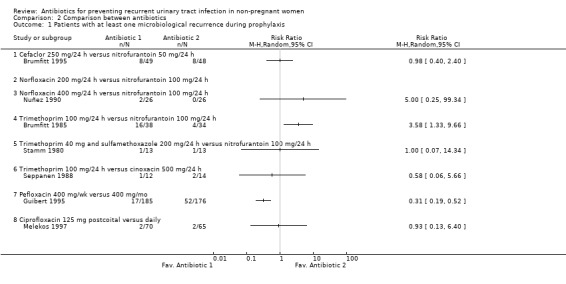

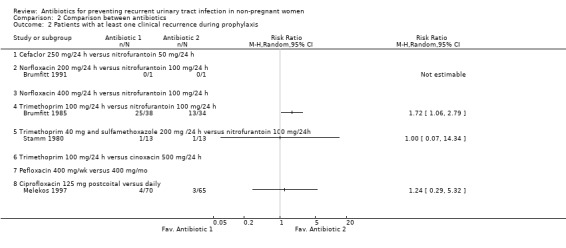

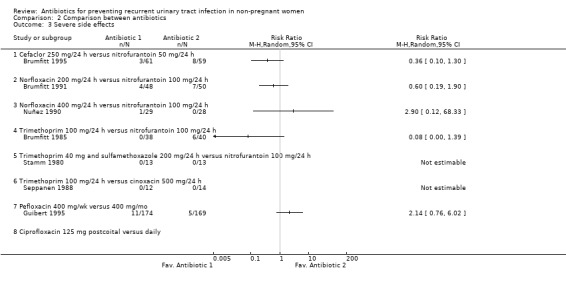

Antibiotic versus antibiotic (eight trials, 513 women): These trials were not pooled. Weekly perfloxacin was more effective than monthly. The RR for MR was 0.31(95% CI 0.19 to 0.52). There was no significant difference in MR between continuous daily and postcoital ciprofloxacin.

Authors' conclusions

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis for 6‐12 months reduced the rate of UTI during prophylaxis when compared to placebo. After prophylaxis two studies showed no difference between groups. There were more adverse events in the antibiotic group. One RCT compared postcoital versus continuous daily ciprofloxacin and found no significant difference in rates of UTIs, suggesting that postcoital treatment could be offered to woman who have UTI associated with sexual intercourse.

Plain language summary

Non‐pregnant women who have had several urinary tract infections are less likely to have another infection if they take antibiotics for six to 12 months

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are infections of the bladder and kidneys. They can cause vomiting, fever and tiredness, and occasionally kidney damage. The review found that non‐pregnant women who had two or more UTIs in the past year had less chance of having a further UTI if given a six to 12 month treatment with antibiotics. The most commonly reported side effects are digestive problems, skin rash and vaginal irritation. More research is needed determine the optimal duration for antibiotic treatment.

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common health care problem. In a sample of women from US 10.8% of them aged 18 and older reported at least one presumed UTI the past year (Foxman 2000).

Recurrent urinary tract infections (RUTI) is defined in the literature by three episodes of UTI in the last twelve months or two episodes in the last six months. Some studies estimate that 20‐30% of women who have a UTI would have an RUTI. According to cohort and case control studies (Hooton 1996; Scholes 2000) risk factors associated with RUTI in sexually active premenopausal women are the frequency of sexual intercourse, the use of spermicides, the age of first UTI (less than 15 years of age indicates a greater risk of RUTI) and history of UTI in the mother; suggesting that genetic factors/long‐term environmental exposures might predispose to this condition. Following menopause, risk factors strongly associated to the condition are vesical prolapse, incontinence and post‐voiding residual urine. Other risk factors like non‐secretor status and history of UTI before menopause need to be confirmed by further research (Raz 2000).

RUTIs cause a significant discomfort to women and a high impact in ambulatory health care costs as a result of outpatients visits, diagnostic tests and prescriptions. Different approaches have been proposed for the prevention of RUTI and include; non‐pharmacological therapies such as voiding after sexual intercourse or the ingestion of cranberry juice (Jepson 2004), and the use of antibiotics as preventive therapy antibiotic given in regular basis or postcoital prophylaxis in sexually active women.

With respect to antibiotic prophylaxis, it is not known which antibiotic schedule is best, or what is the optimal duration of prophylaxis, the incidence of adverse events, the recurrence of infections after stopped prophylaxis or the treatment adherence.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to assess the efficacy (reduction in number of microbiological and clinical recurrences) and safety (side effects) of antibiotic prophylactic for prevention of RUTI in adult, non‐pregnant women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any published randomised control trial (RCT) where antibiotics were used as prophylactic therapy in women with recurrent urinary tract infections.

Types of participants

Non‐pregnant women over 14 years of age with a history of at least two episodes of uncomplicated UTI in the last year. We excluded trials including women with a history of urological surgery, stones or renal function impairment.

Types of interventions

Any antibiotic regimen administered for at least six months as a preventive strategy for RUTI. We included any type of schedule strategy (daily basis, weekly, monthly or postcoital).

The control group should have received placebo, antibiotic (same antibiotic different schedule, or two different antibiotics), or another pharmacological non‐antibiotic treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Recurrences occurring during active prophylaxis period

Number of recurrences/patient‐year, using microbiological criteria (Microbiological criteria could be: confirmation of diagnosis of recurrence by a positive urine culture of > 100,000 bacteria/ml with isolation or identification of the agent responsible or if there is pyuria plus symptoms > 10,000 bacteria/ml) (MRPY).

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence during prophylaxis, using microbiological criteria (%MR).

Number of recurrences/patient‐year during prophylaxis, identified using clinical criteria (dysuria and/or pollakiuria) (CRPY).

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence during prophylaxis, identified using clinical criteria (dysuria and/or pollakiuria) (%CR).

Recurrences occurring after active prophylaxis period

Number of recurrences per patient/year after prophylaxis, using microbiological criteria.

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence after prophylaxis, using microbiological criteria.

Number of recurrences per patient/year after prophylaxis, identified using clinical criteria.

Proportion of patients with at least one recurrence after prophylaxis, identified using clinical criteria.

Side effects

Proportion of patients who had severe side effects (defined as those requiring withdrawal of treatment)

Proportion of patients with mild side effects (i.e. not requiring withdrawal of treatment).

Withdrawals

Proportion of patients who withdrawal treatment in both groups.

The same numeration is used for the results in the tables of comparisons. Trials which had data of at least one of the first four outcomes were included.

Search methods for identification of studies

Initial search

We attempted to identify as many as relevant published clinical trials as possible in which antibiotics to prevent RUTIs were assessed. We used electronic searching of bibliographic databases and hand‐searching, according to the methods described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook.

MEDLINE from 1966 to April 2004 using the search terms "recurrent urinary tract infection"[in all fields] AND wom* [in all fields] AND prophy* [in all fields] OR preven* [in all fields], combined with the MEDLINE search strategies for randomised controlled trials suggested by the Cochrane Centre, without language restrictions.

EMBASE from 1988 to January 2003 using similar search strategy

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials(CENTRAL in The Cochrane Library, Issue 1 2004).

The reference list of articles.

Review updates

The Cochrane Renal Group's specialised register and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, in The Cochrane Library) and MEDLINE was searched. CENTRAL and the Renal Group's specialised register contain the handsearched results of conference proceedings from general and speciality meetings. This is an ongoing activity across the Cochrane Collaboration and is both retrospective and prospective (Master List 2007). Please refer to The Cochrane Renal Review Group's Module in The Cochrane Library for the complete lis of nephrology conference proceedings searched.

November 2005

No new studies identified.

March 2007

Two new ongoing studies were identified and shall be included once they have been completed and published (Beerepoot 2006; McMurdo 2006). Five studies (six reports) were excluded (Donabedian 1995; Ejrnaes 2006; Ferry 2004; Hoivik 1984; Kasanen 1983).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of trials

Two reviewers independently selected the trials using the defined inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement a third reviewer was involved. We performed a pilot test to the reproducibility of the decisions between the two reviewers.

Evaluation of quality

The quality of the trials included was assessed in terms of the randomisation process and internal and external validity, based on the criteria described by Guyatt 1993. The criteria used were:

Was the randomisation list concealed?

Allocation adequately concealed (A) (Used central randomisation, allocation through pharmacy, sealed envelopes).

Method of allocation inadequate (B).

Method of allocation not specified (C).

Were patients and clinicians "blind" to treatment?

Single or double‐blind.

Not blinded.

Method not reported.

Was the follow‐up complete?

Loss of less than 20%.

Loss of 20% or more.

Not reported.

Were patients analysed in the groups to which they were randomised?

Yes.

No.

Unclear.

Were groups similar at the start of the trial?

No difference in prognostic factors between treatment groups.

Difference in prognostic factors between treatment groups.

Not reported.

Aside from the experimental intervention, were the groups treated equally?

Yes (Information on confounding treatments is provided).

No.

Not reported.

Two reviewers independently estimate the quality of included trials. An overall 'quality score' was not obtained. If heterogeneity was detected in the trials, the quality assessments were used to explain it. Quality was also measured though the Validated Quality Scale (Jadad 1996) which provides a score ranging from 0 to 5; studies not reaching 3 points were considered to be of poor quality.

Data collection

Two reviewers independently extracted the data using the "extraction data form" specifically designed for this review. The following information was collected from each study:

Study setting,

Study population (age, co‐morbidity, prior treatments);

Type of clinical trial;

Inclusion criteria;

Description of the intervention(s);

Duration of the intervention(s);

Length of follow‐up;

Methods used to assess outcomes (urine culture, clinical evaluation);

Number of "drop‐outs" and how the data were analysed;

Results.

Data analysis

The number of microbiological and clinical recurrences/patient/year during prophylaxis period) were analysed using density incidence. Relative risk (RR) and their confidence interval were calculated using Epi Info version 6.04 (Bernard 1987; Hennekens 1987). Dichotomous outcomes (proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence during and after prophylaxis period and proportion of patients with adverse events) where analysed through RR. Absolute risk reduction (ARR) was evaluated using number needed‐to‐treat ( NNT), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) where calculated from CI limits of ARR (Altman 1998). We performed pooled analysis for the group antibiotics versus placebo. Heterogeneity was tested by a standard chi‐square test and considered to be significant if P < 0.1. Sensitivity analysis was done excluding those trials that have different inclusion criteria or tested different schedules.

In the group antibiotic versus antibiotic, pooled analysis of the data was done in five trials that compared nitrofurantoin against another antibiotic. The pooled risk of microbiological recurrences and the pooled risk of adverse events were analysed. The three other trials in this group and the last group (antibiotic versus other pharmacological intervention) did not have any particular feature in common that justified pooled analysis. We described the P value as stated in the original article for MRPY and CRPY. For categorical outcomes we expressed the RR and the 95% CI for each trial.

Results

Description of studies

We retrieved 108 studies from the search strategy. Eighty‐nine studies were excluded. Reasons for exclusion where:

Thirty‐four were not prophylaxis studies.

Nineteen were not antibiotic interventions.

Of the remaining 34 (see Characteristics of excluded studies), twenty‐five were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria:

Fourteen studies were before‐after studies (Battilana 1988; Brumfitt 1987; Fairley 1974; Harding 1979; Jodal 1989; Light 1981; Masu 1984; Pfau 1983; Pfau 1988; Pfau 1989; Pfau 1994; Privette 1988; Svensson 1982; Westenfelder 1987),

Four were crossover trials (Biering 1994; Meyhoff 1981; Toba 1991; Wong 1985), and

Seven were non‐randomised or not controlled trials (Harding 1974; Kasanen 1974; Landes 1970; Martens 1995b; Ronald 1975; Sakurai 1994a; Stamey 1977).

The remaining nine trials were not included for other reasons:

duration of intervention less than six months (MacDonald 1983; Mavromanolakis 1997),

including children (Fujii 1981), including men (Hardy 1980; Vahlensieck 1992),

complicated UTIs (Kalowski 1975; Kasanen 1982; Landes 1980; Raz 1991).

Finally, nineteen studies met the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of included studies and Table 4 and Table 5).

1. Antibiotic versus placebo. Description of studies.

| Study (antibiotic) | N | Treatment period | Follow‐up | Dose regimen | Fertile cycle, age | Setting | Definition of RUTI | Diagnosis: anatomical abnormality | Definition of clinical RUTI |

| Martens 1995 (cinoxacin 250) | 60 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Premenopausal range 18 to 35 years (88% < 25 years) | Outpatient clinic (medical centre) | Three episodes | Unclear | ‐‐‐‐ |

| Martorana 1984 (cinoxacin 500) | 40 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Both ‐ pre and postmenopausal range 20 to 65 years | Outpatient urologic clinic | 3 episodes | Unclear | ‐‐‐‐ |

| Schaeffer 1982 (cinoxacin 500) | 30 | 6 months or until UTI | 6 months | Daily | Both ‐ range 20 to 69 years | Outpatient urologic clinic | Three documented episodes | Unclear | ‐‐‐‐ |

| Scheckler 1982 (cinoxacin 500) | 59 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Both ‐ range 18 to 65 (83% < 35 years) | 3 family practices 1 general urology clinic | Three episodes, most bacteria | Unclear | Symptoms |

| Nicolle 1989 (norfloxacin 200) | 30 | 12 months or until UTI | Only antibiotic arm | Daily | Both ‐ range 12 to 75 years | Outpatient infection clinic | Three symptomatic episodes | Unclear | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Rugendorff 1987 (norfloxacin 200) | 39 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Both ‐ range 17 to 77 years | Outpatient urologic clinic | Three episodes (facultative bacteria) | Unclear | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Stamm 1980 (nitrofurantoin 100; cotrimoxazole 40‐200) | 45 | 6 months or until UTI | 6 months | Daily | Both ‐ range 19 to 73 years. Mean 54 years. | Outpatient infection clinic | Two culture documented episodes | Yes, included | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Bailey 1971 (nitrofurantoin 50) | 50 | 6 months or until UTI. Unclear | No | Daily | Premenopausal | Urinary infection clinic | History of RUTI | Yes, excluded | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Gower 1975 (cephalexin 125) | 50 | 12 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Both ‐ range 20 to 60 years. mean 31 years. | Outpatient renal infection clinic | History of RUTI | Unclear | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Stappleton 1990 (cotrimoxazole 40‐200) | 27 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Postcoital | Premenopausal Median 23 years. | University students (department) | Two documented episodes related to intercourse | Unclear | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Total | 430 |

2. Antibiotic versus antibiotic or other strategy. Description of studies.

| Study (antibiotic) | N | Treatment period | Follow‐up | Dose regimen | Fertile cycle, age | Setting | Definition RUTI | Diagnosis: anatomical abnormality | Definition of clinical RUTI |

| Brumfitt 1995 (cefaclor 250; nitrofurantoin 50) | 135 | 12 months | 3‐6 months. Not available | Daily | Both Range: 18‐90 years. Mean: 45‐40 years | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 4 symptomatic (1 bact.) | Yes, included | Symptoms |

| Brumfitt 1991 (norfloxacin 200; nitrofurantoin 100) | 111 | 12 months | 3‐6 months. Not available | Daily | Both Range: 17‐83 years. Mean: 39‐37 years. | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 4 symptomatic (1 bact.) | Yes, included | Symptoms |

| Nuñez 1990 (norfloxacin 400; nitrofurantoin 100) | 56 | 6 months or until UTI | No | Daily | Both Mean: 46‐45 years. | Outpatient urologic clinic | 2 verified by medical records | Unclear | ‐‐‐ |

| Brumfitt 1985 (trimethoprim 100; nitrofurantoin 100) | 100 | 12 months | No | Daily | Both Mean: 38‐41 years | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 3 symptomatic (1 bact.) | Yes, included | Symptoms |

| Stamm 1980 (*Also in Table 4 cotrimoxazole 40‐200; nitrofurantoin 100) | 30 | 6 months or until UTI | 6 months | Daily | Both Range 19‐73 years. Mean: 54 years. | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 2 cultures documented | Yes, included (minor) | Symptomatic bacteriuria |

| Seppanen 1988 (trimethoprim 100; cinoxacin 500) | 26 | 6 months or until UTI | 4‐6 weeks | Daily | Both Range: 17‐63 years. Mean: 27‐33 years. | Outpatient urologic clinic | 3 episodes | Yes, excluded | ‐‐‐ |

| Guibert 1995 (pefloxacin 400) | 361 | 11 months (48 weeks) | 3 months (not all women) | Weekly versus monthly | Both Range: 18‐51 years. Mean: 38‐37 years. | Family Practice | 4 acute cystitis | Yes, excluded | ‐‐‐ |

| Melekos 1997 (ciprofloxazole 125) | 152 | 12 months | 12 months | Postcoital versus daily | Premenopausal Range: 18‐46 years. Mean: 28‐31 years. | Outpatient urologic clinic | 3 documented | Yes, excluded (included 6% minor) | Symptoms |

| Brumfitt 1983 (trimethoprim 100; povidone iodine; methenamine hippurate 1 g) | 67 | 12 months | 3‐6 months. Not available | Trimethoprim: Daily Poividone iodine: Solution Methenamine hippurate: Every 12 h. | Both Mean: 32‐38 years. | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 4 symptomatic (1 bact.) | Yes, included | Symptoms |

| Brumfitt 1981 (nitrofurantoin 50; methenamine hippurate 1 g) | 110 | 12 months | Yes, unclear | Every12 h | Both Mean: 31‐36 years. | Outpatient urinary infection clinic | 3 symptomatic (1 bact.) | Yes, included | Symptoms |

Both = pre and post

We classified the trials into three groups according to the types of interventions evaluated:

Antibiotics versus placebo

Antibiotic versus antibiotic, different antibiotic or same antibiotic using different schedule.

Antibiotic versus another pharmacologic intervention (non‐antibiotic)

Antibiotic versus placebo

(Table 4‐ Antibiotic versus placebo. Description of studies).

Ten trials with a total number of 430 women were studied (Bailey 1971; Gower 1975; Martens 1995; Martorana 1984; Nicolle 1989; Rugendorff 1987; Schaeffer 1982; Scheckler 1982; Stamm 1980; Stappleton 1990). In the study by Stamm 1980, two comparisons were made.

The recruitment was made from outpatient clinics (urologic, general practice or infection clinics) and one study recruited university students (Stappleton 1990). Women were premenopausal in three trials (Bailey 1971; Martens 1995; Stappleton 1990) and both pre‐and postmenopausal in the rest.

Two trials (Nuñez 1990; Stamm 1980) used two documented urinary infections in the last twelve month instead of three as inclusion criteria. There were two studies where the number of past urinary tract infections were not clarified, the authors stated "history of recurrent urinary tract infections" as inclusion criteria (Bailey 1971, Gower 1975). We did a sensitivity analysis excluding them.

The antibiotics used were: norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h (Nicolle 1989; Rugendorff 1987), cinoxacin (or ciprofloxacin) 500 mg/24 h (Martorana 1984; Schaeffer 1982; Scheckler 1982) cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h ( Martens 1995), nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h ( Stamm 1980), nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h (Bailey 1971), cotrimoxazole 40‐200/24 h (Stamm 1980), cephalexin 125 mg/24 h ( Gower 1975) and cotrimoxazole 40‐200 mg postcoital (Stappleton 1990).

Active prophylaxis treatment was six months in eight studies and twelve months in two (Nicolle 1989; Gower 1975). In the case of the post coital study, women were instructed to take Cotrimoxazole one dose after sexual intercourse.

In all studies, prophylaxis was interrupted in cases of recurrence. The definition of clinical recurrence was the presence of bacteriuria plus clinical symptoms of UTI in six studies, or clinical symptoms of UTI (Scheckler 1982).

In relation to post‐intervention follow‐up, only two studies performed follow‐up six months after the finished prophylaxis period (Schaeffer 1982; Stamm 1980).

Antibiotic versus another antibiotic

(Table 5 ‐ Antibiotic verus antibiotic or other strategy. Description of studies)

Six studies with a total of 458 women were included. None of the trials compared the same antibiotic. In five, nitrofurantoin was compared against another antibiotic: cefaclor 250 mg/24 h, norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h, norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h, trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h, trimethoprim 40 mg/24 h and Sulphamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1995; Nuñez 1990; Stamm 1980). The other trial compared trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h (Seppanen 1988).

Women where pre‐ and postmenopausal and recruitment was made from outpatients clinics (urologic or UTI clinics).

In the three Brumfitt trials (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1985) the duration of prophylaxis was twelve months, the definition of clinical recurrence was the presence of clinical symptoms of urinary infection and patients were told not to interrupt prophylaxis in the case of recurrence (the episode was treated and then prophylaxis was restarted). In the other three trials (Nuñez 1990; Seppanen 1988; Stamm 1980) the prophylaxis period was six months and it was suspended in cases of recurrence. Clinical recurrence was defined by bacteriuria plus clinical symptoms of UTI.

In two studies there was some data in relation to follow‐up. In Seppanen 1988 follow‐up was for a period of 4‐6 weeks and in Stamm 1980 for six months after the active intervention period.

Antibiotic versus same antibiotic with different regimen

A total number of 513 women were evaluated in two studies, one comparing pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo (Guibert 1995) and the other Ciprofloxacin 125 mg/24 h versus postcoital (Melekos 1997). In both, the duration of prophylaxis was one year and the follow‐up after the active treatment period was three and twelve months. In Guibert 1995 women were pre‐ and postmenopausal and recruited in family practices. In Melekos 1997 women were premenopausal and sexually active and were screened in urologic outpatient clinics. Patients were told not to interrupt treatment in case of recurrence. The definition of clinical recurrence was the presence of clinical symptoms of UTI in Melekos 1997.

Antibiotic versus other pharmacological strategy (non‐antibiotic)

(Table 5‐ Antibiotic verus placebo or other strategy. Description of studies)) A total number of 177 women were evaluated in two studies (Brumfitt 1981; Brumfitt 1983). One comparing trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine solution and methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h (Brumfitt 1983), and the other compared nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h (Brumfitt 1981). In both the duration of the interventions was twelve months, patients were told not to interrupt treatment in case of recurrence and the definition of clinical recurrence was the presence of clinical symptoms of UTI. Women were pre‐ and postmenopausal and recruitment was made from outpatient UTI clinics.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall the quality of the included studies was poor. As it can be seen from Table 6‐ Antibiotic versus placebo. Methodological quality and Table 7‐ Antibiotic versus antibiotic or other strategy. Methodological quality, most studies did not provide any information regarding randomisation and allocation concealment. The loss‐to‐follow‐up and adverse events in some studies were unclear, barely described or not described at all. However using the JADAD Quality Scale (Jadad 1996), the 11 double‐blind studies obtained 3 points or more.

3. Antibiotic versus placebo. Methodological quality.

| Study (antibiotic) | Blinding | Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Number/group | Withdrawn (dropouts) | Withdrawn (side effects) | Withdrawn (other reasons) | Differences between groups |

| Martens 1995 (cinoxacin 250) | Double | Distribution table | Unclear | 60 32‐28 | 15 (25%) 9‐6 | 3‐0 | 6‐6 Missed appointment: 3‐6 Missed laboratory visits: 2‐0 Pregnant 1‐0 |

No |

| Martorana 1984 (cinoxacin 500) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 40 21‐19 | 0 (0%) | 0‐0 | No | Not reported |

| Schaeffer 1982 (cinoxacin 500) | No | ‐‐ | Unclear | 30 17‐13 | 2 (6.6%) 2‐0 | 2‐0 | No | No |

| Scheckler 1982 (cinoxacin 500) | Double | Random code | Unclear | 59 30‐29 | 18 (30%) 10‐8 | 1‐3 | All: 9 treated < 50 days, 3 poor compliance 4 bacterial culture not protocol 4 other protocol violations | Not reported |

| Nicolle 1989 (norfloxacin 200) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 30 15‐15 | 6 (20%) 4‐2 | 1‐1 | 3‐1: Lost to follow‐up 2‐0 Pregnancy 1‐0 infected at enrolment 0‐1 | Not reported |

| Rugendorff 1987 (norfloxacin 200) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 39 20‐19 | 4 (10%) 2‐2 | No | 2‐2 Poor compliance | Not reported |

| Stamm 1980 (nitrofurantoin 100; cotrimoxazole 40‐200) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 45 15‐15‐15 | 6 (13.2%) 2‐2‐2 | No | 2‐2‐2 lost to follow up | No |

| Bailey 1971 (nitrofurantoin 50) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 50 25‐25 | 0 (0%) | No | Not reported | |

| Gower 1975 (cephalexin 125) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 50 25‐25 | 7 (14%) 5‐2 | 2‐0 | 3‐2 lost to follow up | Not reported |

| Stappleton 1990 (cotrimoxazole 40‐200) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 27 16‐11 | 2 (7.4%) 2‐0 | No | 2‐0 Suspected pregnancy 2‐0 | Yes (Diaphragm users) 69% vs 91% |

4. Antibiotic versus antibiotic or other strategy. Methodological quality.

| Study (antibiotic) | Blinding | Randomisation | Allocation concealment | Number/group | Withdrawn (dropouts) | Withdrawn (side effects) | Withdrawn (other reasons) | Differences between groups |

| Brumfitt 1995 (cefaclor 250; nitrofurantoin 50) | No | ‐‐ | Unclear | 135 | 38 (28%) 12‐11 +15? | 3‐8 | 12‐11: Non compliant or failed to return for three follow‐up visits, side effects 15 (two groups) 9 violation of protocol, 6 failed to return to the clinic. |

None |

| Brumfitt 1991 (norfloxacin 200; nitrofurantoin 100) | No | ‐‐ | Unclear | 111 55‐56 | 23 (20.7%) 10‐13 | 4‐7 (of 98) | *Not clear if included side effects 13 (7‐6) no assessable: 2 left the country, 2 stopped taking their medication after a few days and 9 failed to attend their scheduled appointments. 10 (?) Not clinically assessable. | None |

| Nuñez 1990 (norfloxacin 400; nitrofurantoin 100) | Single | ‐‐ | Unclear | 56 29‐27 | 5 (9%) 3‐2 | 1‐0 | 2‐2 Lost to follow‐up | None |

| Brumfitt 1985 (trimethoprim 100; nitrofurantoin 100) | No | Random chart | Unclear | 100 50‐50 | 28 (28%) 12‐16 | 0‐6 | 12‐10 Non compliant or failed to return for three follow‐up visits | Yes (Radiological abnormality 46% versus 25%) |

| Stamm 1980 *Also in Table 6 (cotrimoxazole 40‐200; nitrofurantoin 100) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 45 15‐15‐(15) | 6 (13.3%) 2‐2‐(2) | 0 | 2‐2‐(2) Lost of follow‐up | None |

| Seppanen 1988 (trimethoprim 100; cinoxacin 500) | Double | ‐‐ | Unclear | 26 12‐14 | 0 (0%) | 0 | Not reported | |

| Guibert 1995 (pefloxacin 400; weekly versus monthly) | Double | ‐‐‐ | Unclear | 361 185‐176 | 25 (7%) 13‐12 | 11‐5 | Lost | None |

| Melekos 1997 (ciprofloxacin 125; postcoital versus daily). | Single | Date of birth | Inadequate | 152 ?‐? | 17 (11.1%) | 5 | 12 (two groups): protocol violation, poor compliance, lost of follow‐up, pregnancy or desire to become pregnant | None |

| Brumfitt 1983 (trimethoprim 100; povidone iodine; methenamine hippurate 1 g) | No | ‐‐ | Unclear | 67 | 3 + 15 (27%) | 0‐3‐4 | 3‐ failed to return to the clinic regularly 15 (were assessed) stopped treatment prematurely: pain on voiding in 3 in MH group, 1 became pregnant in TMP, 1 lost to follow‐up and the remaining 10 failed to attend clinic appointments. | None |

| Brumfitt 1981 (nitrofurantoin 50; methenamine hippurate 1 g) | No | ‐‐ | Unclear | 110* 56‐54 | 11 (10%) 5‐6 | 12‐2 | Failed to return for follow‐up 3‐4, attend only spasmodically 2‐2. *11 patients taking NF were changed to MH. 3 taking MH to NF. | Yes (Radiological abnormality, 29% versus 12%) |

Antibiotic versus placebo

(Table 6 ‐ Antibiotic versus placebo. Methodological quality). Only Scheckler 1982 and Martens 1995 provided some description of the methods of randomisation. In the rest of the trials this was unclear. Nine out of ten trials were double‐blind while allocation concealment was unclear in all the studies. The withdrawal rate was equal or more than 20% in three. In Nicolle 1989 it was 20% (norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h), in Martens 1995 25% (cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h) and 30% in Scheckler 1982 (cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h).

Antibiotic versus antibiotic

(Table 7 ‐ Antibiotic versus antibiotic or other strategy. Methodological quality)

Antibiotic versus another antibiotic

Method of randomisation was not stated in most of the studies. In Brumfitt 1985 was made by random chart . Allocation concealment was unclear or inadequate in all of them. Three studies were not blinded (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1995), one study was single blind (Nuñez 1990), and two were double blinded (Seppanen 1988; Stamm 1980).The withdrawals and drop‐outs were over 20% in three studies (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1995).

Antibiotic versus same antibiotic with different doses

Melekos 1997 had randomisation inadequate (date of birth), unclear allocation concealment and a rate of drop outs of 11%.Guibert 1995 did not report the randomisation methods, was double blinded and the drop out rate was 7%.

Studies comparing antibiotic versus non antibiotic

(Table 7 ‐ Antibiotic versus antibiotic or other strategy. Methodological quality) The two studies were unblinded. Withdrawals and drop‐outs were over 20% in Brumfitt 1983. Brumfitt 1981 was a crossover design.

Effects of interventions

Antibiotics versus placebo (comparison 01)

In 10/11 comparisons, antibiotics showed higher efficacy than placebo to reduce clinical and microbiological recurrences (see additional Table 8‐ Antibiotics versus placebo. MRPY and CRPY).

5. Antibiotic versus placebo. MRPY and CRPY.

| Study (antibiotic) | MRPY Antibiotic | MRPY Placebo | RR (95% CI) | P value | CRPY Antibiotic | CRPY Placebo | RR (95% CI) | P value | Duratation Interval |

| Martens 1995 (cinoxacin 250) | 6 months or until UTI | ||||||||

| Martorana 1984 (cinoxacin 500) | 0.97 (8/8.25) | 3.58 (17/4.75) | 0.27 (0.12, 0.63) | < 0.001 | 6 months or until UTI | ||||

| Schaeffer 1982 (cinoxacin 50) | 0.4 (3/7) | 0.8 (4/5) | 0.54 (0.12, 2.4) | 0.46 | 6 months or until UTI | ||||

| Scheckler 1982 (cinoxacin 500) | 6 months or until UTI | ||||||||

| Nicolle 1989 (norfloxacin 200) | 0 (0/11.6) | 1.6 (10/6.3) | 0 (not defined) | < 0.001 | 0 (0/11.6) | 1.12 (7/6.3) | 0 (Nnt defined) | < 0.001 | 12 months or until UTI |

| Rugendorff 1987 (norfloxacin 200) | 0.54 (4/7.4) | 3.3 (13/3.9) | 0.16 (0.05, 0.5) | < 0.001 | 0.27 (2/7.4) | 2.05 (8/3.9) | 0.13 (0.03, 0.6) | 0.004 | 6 months or until UTI |

| Stamm 1980 (nitrofurantoin 100) | 0.14 (1/7.1) | 2.8 (10/3.6) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.4) | < 0.001 | 6 months or until UTI | ||||

| Bailey 1971 (nitrofurantoin 50) | 0.19 (3/15.9) | 2.06 (15/7.3) | 0.09 (0.03, 0.32) | < 0.001 | 0.06 (1/15.9) | 1.37(10/7.3) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.36) | < 0.001 | 6 months or until UTI |

| Gower 1975 (cephalexin 125) | 12 months or until UTI | ||||||||

| Stamm 1980 (cotrimoxazole ‐ oral) | 0.15 (1/6.7) | 2.8 (10/3.6) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.42) | < 0.001 | 6 months or until UTI | ||||

| Stappleton 1990 (cotrimoxazole ‐ postcoital) | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.001 | 0.3 | 3.6 | 0.001 | 6 months or until UTI |

Recurrences occurring during active prophylaxis period

Number of recurrences/patient‐year, using microbiological criteria (MRPY)

This outcome was assessed in eight comparisons (Table 8 ‐ Antibiotics versus placebo. MRPY and CRPY). The rate range of MRPY was 0 to 0.9 person‐years in the antibiotic group and between 0.8 to 3.6 infections/person‐years in the placebo group.

In a subgroup analysis done by Stappleton 1990 patients were stratified according to their intercourse frequency (three groups: less than twice a week, two to three times per week and more than three) and infection rates for each subgroup were calculated. In the subgroup less than twice/wk the MRPY was 0 (n = 10) in the active treatment arm versus 1.8 in the antibiotic arm, 0.6 versus 4.3 for 2‐3 times/wk (n = 7), and 0.6 versus 15 for greater than 3 times/wk (n = 7). For patients who were on placebo, increases in intercourse frequency were significantly correlated with increases in infection rate ( r = 0.8, P = 0.004).

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence using microbiological criteria (% MR)

All the trials, which included 372 patients, analysed this outcome (analyses 01.01 to 01.08). The pooled data showed that the RR of having at least one recurrence was 0.21 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.33) favouring antibiotic arm. The heterogeneity test was not significant (P = 0.18) and the NNT was 1.85 (CI 1.60 to 2.20)

We performed two sensitivity analyses. First we excluded the postcoital study (Stappleton 1990) and then we excluded those studies that included patients who had only two infections in the 12 months prior to enrolment instead of three, and those that had as inclusion criteria "history of RUTI". The overall effect remained unchanged.

Number of recurrences/patient‐year using clinical criteria (CRPY)

Four trials including 136 patients were analysed and showed a statistically significant difference. (Table 8‐ Antibiotics versus placebo. MRPY and CRPY). The range of having one clinical recurrence was between 0 to 0.27/person‐years in the antibiotic group and 1.12 to 3.6 person‐years in the placebo group ( P < 0.01 for both).

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence using clinical criteria (%CR)

In eight comparisons (seven trials), which included 257 patients, RR of having a clinical UTI was 0.15 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.28) favouring antibiotic against placebo. The heterogeneity test was not significant (P = 0.98) and the NNT to prevent one recurrence was 2.2 (CI 1.80 to 2.80). The exclusion of the two studies that includes women with at least two UTI in the last 12 months, those that had as inclusion criteria "history of RUTI", and excluding the postcoital study did not change the effect.

Recurrence after prophylaxis

In relation to post‐intervention follow‐up two trials had a follow up assessment six months after finished the prophylaxis period (Schaeffer 1982; Stamm 1980). The outcomes used to evaluate patients were MRPY (Stamm 1980) and the proportion of patients with MR in both. In one trial follow up was conducted only in the arm receiving norfloxacin during 12 months (Nicolle 1989 ).

Number of recurrences/patient‐year after prophylaxis using microbiological criteria (MRPY)

The MRPY was 1.2 (nitrofurantoin) and 1.3 (cotrimoxazole) versus 3 in placebo. However, it was not possible to analyse the statistical significance as the authors did not report the data necessary to construct the coefficient.

Proportion of patients who experienced at least one recurrence after prophylaxis using microbiological criteria.( %MR)

Two studies, including 70 patients (Schaeffer 1982; Stamm 1980), were analysed (analysis 01.05). The RR of having at least one recurrence after prophylaxis was 1.53 (CI 0.69 to 3.38) for cinoxacin versus placebo ( Schaeffer 1982), 0.51 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.04) for nitrofurantoin and 0.75 (CI 0.38 to 1.50) for cotrimoxazole 40‐200 mg/24 h (Stamm 1980). The pooled analysis was 0.82 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.53).

Number of recurrences/patient‐year after prophylaxis using clinical criteria (CRPY)

There were not studies that assessed clinical recurrences after prophylaxis.

Side effects

Proportion of patients who had severe side effects

(Table 9‐ Side effects (SE) "severe side effects" defined as those requiring withdrawal of treatment) All trials reported severe side effects. In 225 patients, 9 were withdrawn from treatment in the antibiotic groups and 208 patients were withdrawn in the placebo groups. Four left the study because of adverse events. Five trials had no severe side effects. The pooled RR of severe side effects (analysis 01.03) was 1.58 (95% CI ).47 to 5.28) favouring placebo group. The most common described severe side effects were skin rash and nausea. The absolute numbers of severe side effects were: cephalexin = 2 , cinoxacin 500 mg = 3, cinoxacin 250 mg = 3, norfloxacin = 1 and placebo = 4. Nitrofurantoin ( Bailey 1971; Stamm 1980) and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole daily and postcoital (Stappleton 1990) studies did not reported any severe side effects.

6. Side effects.

| Study | Severe side effects (n/N) | Non‐severe side effects (n/N) |

| Martens 1995 |

Cinoxacin 250: 3/32

Placebo: 0/28 |

Cinoxacin 250: 15/32*

Placebo: 8/28* *Description of both groups: Vaginitis, genital monilia, vaginal itch and anorexia |

| Martorana 1984 |

Cinoxacin 500: 0/21 Placebo: 0/19 |

Cinoxacin 500: 8/21

Placebo: 3/19

|

| Schaeffer 1982 |

Cinoxacin 500: 2/17

Placebo: 0/13 |

Zero in both groups |

| Scheckler 1982 |

Cinoxacin 500: 1/30

Placebo: 3/29

|

Cinoxacin 500: 3/30

Placebo: 2/29

|

| Nicolle 1989 |

Norfloxacin 200: 1/15

Placebo: 1/15

|

Norfloxacin 200: 2/15

Placebo: 2/15

|

| Rugendorff 1987 |

Norfloxacin 200: 0/18 Placebo: 0/17 |

Zero in both groups |

| Stamm 1980 |

Norfloxacin 100: 0/13 TMP‐SMX: 0/13 Placebo: 0/13 |

Norfloxacin 100: 2/13

TMP‐SMX: 0/13 Placebo: 0/13 |

| Bailey 1971 |

Norfloxacin 50: 0/25 Placebo: 0/25 |

Zero in both groups |

| Gower 1975 |

Cephalexin 125: 2/25

Placebo: 0/25 |

Zero in both groups |

| Stappleton 1990 |

TMP‐SMX: 0/16 Placebo: 0/16 |

TMP‐SMX: 4/16

Placebo: 0/16 |

| Brumfitt 1995 |

Cefaclor 250: 3/61 Nitrofurantoin 50: 8/59 *Description include severe and non severe side effects and both groups: "Vaginal irritation and nausea were the most commonly reported events in each group". |

Cefaclor 250: 3/61 Nitrofurantoin 50: 4/59 (see severe side effects) |

| Brumfitt 1991 |

Norfloxacin 200: 4/48

Nitrofurantoin 100: 7/50

|

Norfloxacin 200: 6/48

Nitrofurantoin 100: 8/50

|

| Nuñez 1990 |

Norfloxacin 400: 1/29

Nitrofurantoin 100: 0/28 |

Includes period of full dose treatment Norfloxacin 400: 28/29. Nitrofurantoin 100: 21/28 Both groups: Nausea, headache, epigastralgia, and arthralgia/myalgia |

| Brumfitt 1985 |

Trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole 100: 0/38 Nitrofurantoin 100: 6/48

|

Trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole 100: 7/38

Nitrofurantoin 100: 10/34

|

| Seppanen 1988 |

Trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole 100: 0/12 Cinoxacin 500: 0/14 |

Trimethoprim‐sulphamethoxazole 100: 3/12

Cinoxacin 500: 1/14

|

| Guibert 1995 |

Weekly perfloxacin 400: 11/174 Monthly perfloxacin 400: 5/169 *Description include severe and non‐severe side effects. The most commonly side effects were digestives (nausea) and insomnia. Some tendinopathy was reported. |

Weekly perfloxacin 400: 38/174 Monthly perfloxacin 400: 28/169 (see sever side effects) |

| Melekos 1997 |

Postcoital and daily ciproflocaxin 125: 5/135 (both groups) *Description include severe and non severe side effects. Gastrointestinal distress, headaches, rash and vaginal candidiasis occurred in 13 (4‐9) of the initial 152 patients. Five of these women discontinued preventive treatment and were excluded |

Postcoital ciproflocaxin 125: 4/70 Daily ciproflocaxin 125: 9/65 (see severe side effects) |

| Brumfitt 1983 |

Trimethoprim 100: 0/20 Povidone iodine: 3/19

Methenamine hippurate: 4/25

|

Trimethoprim 100: 1/20

Povidone iodine: 2/19

Methenamine hippurate: 5/25

|

| Brumfitt 1981 |

Nitrofurantoin 50: 12/43

Methenamine hippurate: 2/56

*Description include severe and non‐severe side effects. |

Nitrofurantoin 50: 9/43 Methenamine hippurate: 4/56 (see severe side effects) |

Proportion of patients with other side effects

(Table 9 ‐ Side effects (SE) (not needing to withdrawal of treatment)

The ten studies reported side effects. In a total number of 225 patients that received antibiotic 34 side effects were reported and in the placebo arm 15/195 patients had non‐severe side effects. The RR of having one side effect was 1.78 (95% CI 1.06 to 3.00) favouring the placebo group. The side effects described were vaginal itching and nausea. Vaginal candidiasis was less frequent (see additional table " Description of side effects" Table 9 ). For non‐severe side effects, absolute numbers were: cinoxacin 500 mg = 11, cinoxacin 250 mg = 15, trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole postcoital = 4, nitrofurantoin = 2, norfloxacin 200 mg = 2, cephalexin = 0 and placebo = 15.

Withdrawals and dropouts

Three studies have 20% or more of dropouts during the prophylaxis period. Martens 1995 had 25%, Scheckler 1982 30% and Nicolle 1989 20%. When we excluded this three studies, there were no differences in the main outcomes. There were no differences between placebo and intervention groups in relation to withdrawals.

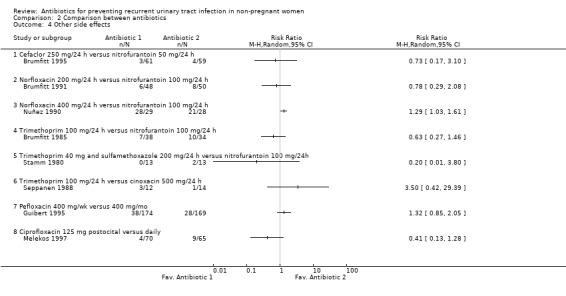

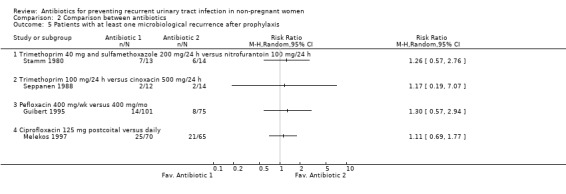

Antibiotic versus antibiotic (comparison 02)

(Table 10 ‐ Antibiotic versus antibiotic. MRPY and CRPY) Eight trials compared antibiotics ‐ either two different antibiotics or different dosing regimens (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1995; Guibert 1995; Melekos 1997; Nuñez 1990; Seppanen 1988; Stamm 1980)

7. Antibiotic versus antibiotic. MRPY and CRPY.

| Study (antibiotics) | MRPY 1 versus 2 | P | CRPY 1 versus 2 | P | Duration of treatment |

| Brumfitt 1995 (cefaclor 250, nitrofurantoin 50) | 0.3 (13/43.6) versus 0.29 (12/41.7) | NS | 1.38 (60/43.6) versus 1.51 (63/41.7) | NS | 12 months |

| Brumfitt 1991 (norfloxacin 200; nitrofurantoin 100) | 0.1 (4/39.9) versus 0.14 (5/35.9) | NS | 0.75 (30/39.9) versus 0.86 (31/35.9) | NS | 12 months |

| Nuñez 1990 (norfloxacin 400; nitrofurantoin 100) | 0.16 (2/12.6) versus 0 (0/13) | NS (0.2) | 6 months or until UTI | ||

| Brumfitt 1985 (trimethoprim 100; nitrofurantoin 100) | 1 (28/27.8) versus 0.17 (5/30) | < 0.001 | 1.69 (47/27.8) versus 1.23 (37/30) | NS | 12 months |

| Stamm 1980 (Cotrimoxazole 40‐200; nitrofurantoin 100) | 0.15 (1/6.7) versus 0.14 (1/7.1) | NS | 6 months or until UTI | ||

| Seppanen 1988 (trimethoprim 100; cinoxacin 500) | 0.18 (1/5.5) versus 0.31 (2/6.4) | NS (0.6) | 6 months or until UTI | ||

| Guibert 1995 (pefloxacin 400; weekly versus monthly) | 0.16 (23/145.8) versus 0.6 (78/129.4) | < 0.001 | 11 months | ||

| Melekos 1997 (ciprofloxazole 125; postcoital versus daily) | 0.043 (3/70) versus 0.031 (2/65) | NS (0.7) | 12 months |

NS = not significant

Comparison between two different antibiotics

The studies identified did not compare the same antibiotics. In four studies nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h was compared against: norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h, norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h, trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h and trimethoprim 40 mg and sulphamethoxazole 200 mg /24 h (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Nuñez 1990; Stamm 1980). In another study nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h was compared with cefaclor 250 mg/24 h (Brumfitt 1991). The individual results of this studies did not showed a clear benefit of one antibiotic over another. The only trial that showed an effect ( Brumfitt 1985), compared nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h versus trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h and had a RR of having microbiological recurrences of 3.58 favouring nitrofurantoin. However the CIs were very wide (95% CI 1.33 to 9.66). The RR for clinical recurrences was 1.72 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.79)

One trial compared trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h with cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h (Seppanen 1988) and showed no significant differences between the two antibiotics.

We tried to pooled the data from the four studies that compared nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h against another antibiotic. There was significant heterogeneity between the trials and differences in the way clinical outcomes were assessed. Therefore we decided not to present the pooled data.

In relation to severe adverse events, the pooled data showed more severe adverse events with nitrofurantoin versus the rest of the antibiotics. Looking at the data, the study that had the most differences compared trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h (Brumfitt 1985), the same study that showed higher efficacy for nitrofurantoin. Excluding this study there were no differences between nitrofurantoin and the rest of antibiotics RR 0.54 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.24) using the random effects model.

With other side effects there were no difference between nitrofurantoin and the rest, but there was heterogeneity among the trials. The most frequent adverse events in all trials were nausea, vaginal candidiasis and oral candidiasis. Nuñez 1990 included in the assessment of adverse events the period while patients were receiving antibiotic as treatment for UTI. This trial had the highest rate of adverse events and most women reported events during the treatment period or during prophylaxis.

Comparison between same antibiotic but different schedule

Guibert 1995 compared pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus pefloxacin 400 mg/mo. In this individual trial weekly pefloxacin was more effective than monthly treatment. The RR of having one microbiological recurrence was 0.31(95% CI 0.19 to 0.52) favouring the weekly schedule. There was no significant difference in the risk in the adverse events rate. The RR for severe adverse events was 2.14 (95% CI 0.76 to 6.02) and 1.32 (95% CI 0.85 to 2.05) for other side effects. The post‐intervention follow‐up did not showed any differences between the groups in relation to the risk of having a microbiological recurrence.

In Melekos 1997, sexual active women with UTI associated with sexual intercourse received ciprofloxacin 125 mg postcoital versus ciprofloxacin 125 mg/24 h for 12 months and microbiological and clinical outcomes were assessed. The difference in the rate of urinary infections and the rate of side effects between postcoital or daily intake was not significantly difference(MRPY = 0.46 versus 0.42, P = 0.8) after the active prophylaxis period.

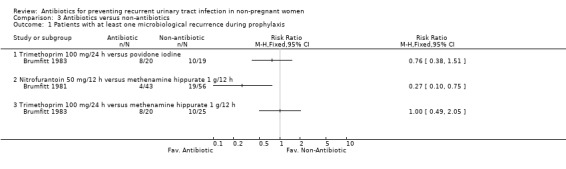

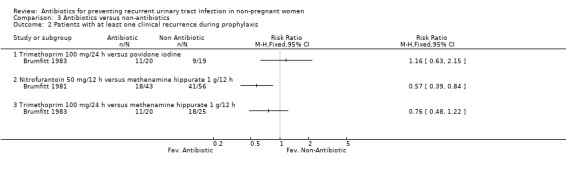

Antibiotic versus other pharmacological intervention (comparison 03)

(Table 11 ‐ Antibiotic versus other strategy. MRPY and CRPY) Brumfitt 1983 compared trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine and trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h. There were 20‐25 patients in each arm. There were few differences between groups both in terms of clinical and microbiological recurrence.

8. Antibiotic versus other strategy. MRPY and CRPY.

| Study (interventions) | MRPY: antibotic versus other strategy | P | CRPY: antibiotic versus other strategy | P | Duration of intervention |

| Brumfitt 1983 (trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h; povidone iodine) | 1.53 (15/9.8) versus 1.79 (17/9.5) | NS | 2.24 (22/9.8) versus 2.42 (23/9.5) | NS | 12 months |

| Brumfitt 1981 (nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h; methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h) | 0.19 (5/26.5) versus 0.57 (25/43.9) | 0.02 | 1.02 (27/26.5) versus 2.32 (102/43.9) | < 0.001 | 12 months |

| Brumfitt 1983 (trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h; methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h) | 1.53 (15/9.8) versus 1.38 (24/17.4) | NS | 2.24 (22/9.8) versus 2.01 (35/17.4) | NS | 12 months |

NS = not significant

Brumfitt 1981 tested nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h. The study was not blinded. The MRPY was 0.19 person‐year for nitrofurantoin and 0.57 for the methenamine hippurate group. The severe adverse events were 12/43 patients in the nitrofurantoin arm and 2/56 patients in the hippurate group. In this trial there were crossovers.

Discussion

Antibiotic intake (cotrimoxazole, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, or norfloxacin/cinoxacin) reduced the number of clinical and microbiological recurrences when compared to placebo in pre‐ and postmenopausal women with RUTI. The results of the trials were consistent both in the direction and magnitude of the effect. Only Schaeffer 1982 showed no benefit, however this trial had few events (two in the antibiotic group and four in the placebo arm) and this could explain the lack of significance. Once the antibiotics were suspended, UTIs recurred and equalled those of the placebo arm in the two studies that have look at this outcome. This data confirms clinical suspicions that the effect on UTI is only short acting.

The consequences of taking antibiotics are the adverse events. The rate of adverse events was higher in the antibiotic group than placebo. It is important to highlight here that all the trials have different ways in reporting adverse events. As a result we have analysed studies with a broad range of reported adverse events. For example, in some trials the reported averse event rate in the antibiotic arm was zero, something that is rarely reproduced in real life.

The adverse events were classified in most trials as severe or mild. Severe adverse events were those that forced the suspension of treatment. As a result In some trials adverse events (e.g. oral or vaginal candidiasis) were classified as mild and in others severe. If we put the intervention into the perspective of dally practice where an otherwise healthy women is starting on antibiotics to prevents UTI it seems that an episode of vaginal or oral candidiasis could been perceived as extremely bothersome.

Other factors to take into account are withdrawals and dropouts .Three studies reported more than 20%. This data suggests that outside of clinical trials these figures could be large. It is already difficult to enhance adherence with chronic medications. Patient compliance is an important factor and must to be consider in future studies. Women's preferences are very important in deciding if prophylaxis should be given, and under special circumstances (e.g. travel or student exam periods) the benefits outweigh the risks.

The overall quality of the clinical trials evaluated comparing antibiotic versus placebo was acceptable remembering that some were done in the seventies and others in the eighties, and this may simply reflect a lack of reporting rather than low quality. All but one had 3 or more points in the JADAD scale, however they did not explain randomisation or allocation procedures. The trial with lowest methodological quality was the study that showed no difference. The study was not blinded and had a low rate of recurrence in both groups (Schaeffer 1982).

The different decades of the trials affected the definition of RUTI. The earliest studies considered two UTIs in the past 12 months, while the later studies accepted as a definition for RUTI three or more UTIs. A criticism of the clinical trials reviewed here is the variability among them in relation to outcomes and adverse events assessment and the lack, in most part, of follow‐up after finishing the antibiotic prophylaxis intake period.

If deciding to start a patient on antibiotics is a difficult task, deciding which one should be the first selection is even more complicated. We had planned to answer this question analysing the second group of studies (antibiotic versus antibiotic) but the identified trials did not allow us to determine this. Most trials could not be compared with respect to the efficacy outcomes and especially the adverse events data. It would be inappropriate to compare adverse event rates, since most trials assessed this outcomes differently. We were able to perform a pooled data analysis of the five studies comparing nitrofurantoin with other antibiotics. There were no significant differences in effectiveness between nitrofurantoin and the other groups. Nitrofurantoin appears to be more effective than trimethoprim, but had more side effects in a non‐blind study. With respect to adverse events it is difficult to assess wether nitrofurantoin had more episodes than the rest. It seems that had the same risk of adverse events but more withdrawals, the decision of which antibiotic to use should rely on local resistance patterns, cost and adverse events. Consumers must to be informed in relation of the events that they might experience while taking the medication.

Which schedule use is even less clear than the antibiotic selection. Daily intake was the most tested schedule. Two trials tested postcoital schedule in sexually active women. One trial included 27 patients and compared postcoital versus placebo and the other included 135 women and compared postcoital versus daily intake. Postcoital was more effective than placebo in reducing recurrences and daily was as effective as postcoital. These two studies suggest that in sexual active women with UTI related to sexual intercourse, the postcoital approach could be a better option than daily intake.

Another trial compared pefloxacin 400 mg weekly versus monthly. The microbiological recurrences were less in the weekly approach than the monthly.

The other decision that physician needs to make is how long the prophylaxis should be given. Unfortunately the studies identified did not look at prophylaxis longer than 12 months. The threshold for starting prophylactic treatment is also controversial. Some experts advocate as few as two UTIs/year and others as many as six UTI episodes/year (PRODIGY 2003). Again women's preferences should be taking into consideration while deciding the best approach.

Another difficult to answer question is which patients would benefit most from these strategies. We we unable to perform any subgroup analyses. The only data that we have is that most of the studies involved healthy women pre‐ and postmenopausal. The subgroup analysis done by Stappleton 1990 showed that women with higher frequencies of sexual intercourse/week had higher infections rates, something that is consistent with previous findings. The definition of recurrences also deserves discussion. Most of the trials used microbiological recurrences as the main outcome. The arguments against this outcome would be that microbiological recurrences are not relevant at all and that the only important outcomes are clinical ones. However, the cohort study done by Hooton 1996 showed that asymptomatic bacteriuria was a strong predictor of UTI. Considering clinical recurrence, the definition was different among studies. Some trials used symptomatic bacteriuria, which seems the most relevant outcome, and others just symptoms. For example, in the three antibiotic versus antibiotic studies by Brumfitt studies (Brumfitt 1985; Brumfitt 1991; Brumfitt 1995) clinical recurrence was defined as the presence of clinical symptoms. It was impressive that clinical recurrences were five times higher than microbiological ones in these three studies suggesting that most patients did not have UTI.

The ecological impact of preventive long‐term antibiotics on bacterial resistance needs to be considered in future trials. It is possible that bacterial resistance patterns changes from time to time and between communities. The actual local bacterial resistance should also be considered (Baerheim 2001) when deciding the best strategy.

For future research it would be important to compare antibiotic prophylaxis against other interventions such a self‐diagnosis /self‐treatment, the ingestion of cranberry juice or oestrogens in postmenopausal women as there are no trials that compared these alternatives. Finally, is crucial that researchers improve the quality of clinical trials in RUTI. The first step should be for a uniform definition of RUTI, the outcomes, assessment of adverse events and the follow‐up period.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis using, cotrimoxazole, nitrofurantoin, cephalexin, or a quinolone (norfloxacin, cinoxacin) reduces rates of RUTI in non‐pregnant women with uncomplicated RUTIs when compared with placebo. The effect lasts during the active antibiotic intake period.

The duration of the intervention is not clear. The maximal duration tested was one year.

Side effects are frequent. Described side effects are: vaginal and oral candidiasis, skin rash, nausea. Dropouts and withdrawal were frequent. Three studies (versus placebo) reported rates more than 20%. Nitrofurantoin displayed the highest number of withdrawals, followed by cephalexin and weekly pefloxacin.

The decision of the best antibiotic choice must relay on community patterns of resistance, adverse events and local costs.

In women with UTI associated with sexual intercourse, post coital prophylaxis seems to be as effective as daily intake.

No conclusions can be drawn about the optimal duration of prophylaxis, schedule or doses.

Women preferences should be taking into account to balance adverse events and the discomfort caused by UTIs.

Implications for research.

The first goal should be to achieve a standardized the way in which RCTs in this area are performed.

To allow comparisons, researchers need to established the same definition for RUTI, assess outcomes in similar fashion and to retrieve adverse events in the same way. By doing so, different trials could be easily compared and conclusion more easily reached.

Research should focus on comparing other strategies (e.g. self‐treatment, the ingestion of cranberry juice against antibiotic prophylaxis or vaginal estriol for postmenopausal women).

Further investigations are needed in relation to predisposing risk factors in both sexually active women and postmenopausal women and to explore other strategies to prevent UTI.

Regarding long term prophylaxis with antibiotics, there is no clear evidence on the optimal duration of prophylaxis, how often should it be repeated, post‐prophylaxis benefits nor the optimal doses of the different antibiotics. The last clinical trial was done in 1997, a surprising fact given the many issues that need to be assessed.

For future trials it would be desirable to evaluate quality of life, women's preferences and long‐term outcomes with each alternative. It would also be helpful cost effectiveness studies of the different alternatives.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1998 Review first published: Issue 3, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 March 2007 | Amended | Two new ongoing studies identified which will be included upon their completion. |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre and the Cochrane Renal Group for their technical support and patience. To Gerard Urrutia , Marta Roqué and Santiago Pérez.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antibiotic versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis | 10 | 372 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.13, 0.34] |

| 1.1 Cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.01, 0.39] |

| 1.2 Cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 3 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.39 [0.24, 0.66] |

| 1.3 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h | 2 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.04, 0.93] |

| 1.4 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 0.63] |

| 1.5 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.07, 0.61] |

| 1.6 Cephalexin 125 mg/24 h | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.01, 0.62] |

| 1.7 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.02, 0.75] |

| 1.8 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg postcoital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.04, 0.58] |

| 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis | 7 | 257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.08, 0.28] |

| 2.1 Cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | 39 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.06, 0.98] |

| 2.3 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h | 2 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.05, 0.66] |

| 2.4 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.02, 0.75] |

| 2.5 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.01, 0.72] |

| 2.6 Cephalexin 125 mg/24 h | 1 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [0.01, 0.74] |

| 2.7 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.12 [0.02, 0.82] |

| 2.8 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg postcoital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.15 [0.04, 0.58] |

| 3 Severe side effects | 10 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.58 [0.47, 5.28] |

| 3.1 Cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.15 [0.33, 114.16] |

| 3.2 Cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 3 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.08, 10.29] |

| 3.3 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h | 2 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 14.55] |

| 3.4 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.5 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.6 Cephalexin 125 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.25, 99.16] |

| 3.7 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.8 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg postcoital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Other side effects | 10 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.78 [1.06, 3.00] |

| 4.1 Cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.64 [0.82, 3.28] |

| 4.2 Cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 3 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.05 [0.78, 5.40] |

| 4.3 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h | 2 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.16, 6.20] |

| 4.4 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.5 [0.14, 45.33] |

| 4.5 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.6 Cephalexin 125 mg/24 h | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.7 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.8 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg postcoital | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 6.35 [0.38, 107.30] |

| 5 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence after prophylaxis | 2 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.44, 1.53] |

| 5.1 Cinoxacin 250 mg/24 h | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 Cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.53 [0.69, 3.38] |

| 5.3 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.4 Nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.25, 1.04] |

| 5.5 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.6 Cephalexin 125 mg/24 h | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.7 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h | 1 | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.38, 1.50] |

| 5.8 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg postcoital | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, Outcome 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, Outcome 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, Outcome 3 Severe side effects.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, Outcome 4 Other side effects.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo, Outcome 5 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence after prophylaxis.

Comparison 2. Comparison between antibiotics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Cefaclor 250 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.5 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.6 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.7 Pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.8 Ciprofloxacin 125 mg postcoital versus daily | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Cefaclor 250 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg /24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.6 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.7 Pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.8 Ciprofloxacin 125 mg postcoital versus daily | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Severe side effects | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Cefaclor 250 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.5 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.6 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.7 Pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.8 Ciprofloxacin 125 mg postcoital versus daily | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Other side effects | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Cefaclor 250 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 50 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Norfloxacin 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Norfloxacin 400 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.5 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.6 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.7 Pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.8 Ciprofloxacin 125 mg postocital versus daily | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence after prophylaxis | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Trimethoprim 40 mg and sulfamethoxazole 200 mg/24 h versus nitrofurantoin 100 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus cinoxacin 500 mg/24 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Pefloxacin 400 mg/wk versus 400 mg/mo | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Ciprofloxacin 125 mg postcoital versus daily | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between antibiotics, Outcome 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between antibiotics, Outcome 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between antibiotics, Outcome 3 Severe side effects.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between antibiotics, Outcome 4 Other side effects.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison between antibiotics, Outcome 5 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence after prophylaxis.

Comparison 3. Antibiotics versus non‐antibiotics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

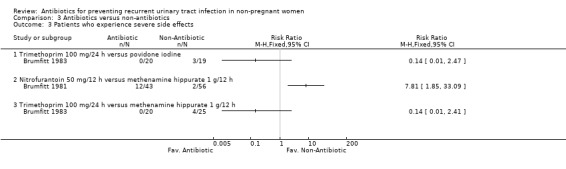

| 3 Patients who experience severe side effects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

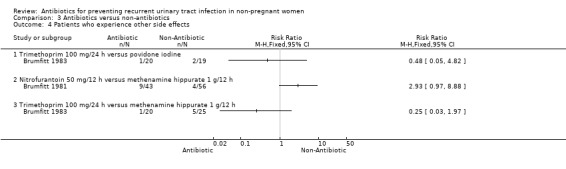

| 4 Patients who experience other side effects | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus povidone iodine | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Nitrofurantoin 50 mg/12 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Trimethoprim 100 mg/24 h versus methenamine hippurate 1 g/12 h | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics versus non‐antibiotics, Outcome 1 Patients with at least one microbiological recurrence during prophylaxis.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics versus non‐antibiotics, Outcome 2 Patients with at least one clinical recurrence during prophylaxis.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics versus non‐antibiotics, Outcome 3 Patients who experience severe side effects.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Antibiotics versus non‐antibiotics, Outcome 4 Patients who experience other side effects.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bailey 1971.

| Methods | Double blind. Duration of intervention: unclear. If bacteriuria recurred, the patient ended the study. (Outcomes at 26 weeks). Follow‐up: not assessed Withdrawals and dropouts: 0. Bacteriological evaluation of urine: every 4 weeks for the first 3 months and thereafter every 6‐8 weeks. | |

| Participants | 50 women (25 in each group). Assessed efficacy in all. Setting: Urinary infection clinic (Hospital). Inclusion: history of recurrent urinary‐tract symptoms with bacteriuria. Premenopausal women. Inclusion after infection and treatment. | |

| Interventions | Nitrofurantoin 50 mg each night, versus placebo. Mean time on treatment: 33 weeks (range 5‐53) in nitrofurantoin group, and 15.1 weeks (range 1‐39) in placebo group. | |

| Outcomes | 1. No. of bacteriuria episodes (2, 12 and 26 weeks). 2. Episode symptomatic or asymptomatic at 26 weeks | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Brumfitt 1981.

| Methods | Not blinding. Duration intervention: 12 months. Post‐intervention follow‐up: performed in 28 patients for an average of 143 days. Withdrawals and drop‐outs: 11. Bacteriological evaluation of urine: 8 in 12 months (monthly intervals for 6 months, then at 9 and 12 months after entry). Eleven patients originally allocated to nitrofurantoin were changed to methenamine hippurate, and three were changed of methenamine hippurate to nitrofurantoin. | |

| Participants | 110 women. Assessed efficacy in 99: 43 in group nitrofurantoin (mean age 31.3 years, SD 13.2), and 56 in group methenamine hippurate (mean age 35.9 years, SD 16.7). Setting: Hospital (UTI Clinic). Inclusion: In the preceding year at least 3 episodes of symptoms of UTI, at least one of these documented microbiologically (not all). | |