Abstract

Background

Prostacyclin is an agent with a number of effects on platelets, blood vessels and nerve cells which might improve outcome after acute ischaemic stroke.

Objectives

To assess the effect of prostacyclin or analogues on survival in people with acute ischaemic stroke.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched November 2003). For the first version, we also searched EMBASE (1980 to 1999), MEDLINE (1966 to 1999), Science Citation Index (1981 to 1999) and the Ottawa Stroke Trials Registry. We also contacted the manufacturers of prostacyclin and the principal investigators of the identified trials.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials comparing prostacyclin or analogues with placebo or control. Trials where people were entered within one week of stroke onset were included.

Data collection and analysis

Information on the methods of randomisation, blinding, analysis, the number of patients randomised, dose and timing of prostacyclin or analogue, patient withdrawals, the number of deaths occurring in each trial, and trial quality, were collected and assessed.

Main results

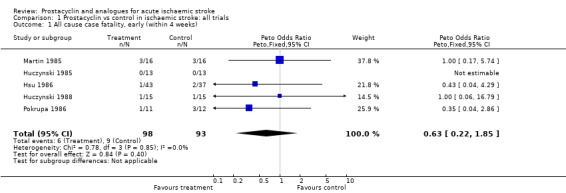

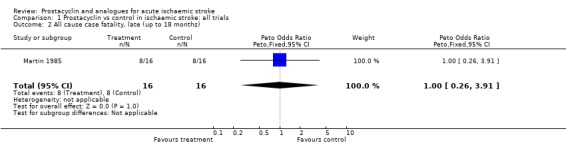

Five trials involving 191 people were included. Six early deaths (within four weeks) occurred with prostacyclin, and nine with placebo (odds ratio (OR) 0.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 1.85). One trial of 32 patients reported late deaths (by 10 to 18 months) in 50% of patients in each group.

Authors' conclusions

Too few patients have been studied in randomised trials to allow conclusions to be drawn about the effect of prostacyclin treatment on survival of people with acute stroke.

Plain language summary

Prostacyclin and analogues for acute ischaemic stroke

Prostacyclin and related drugs, which can dilate brain blood vessels, are of no apparent benefit in the early treatment of strokes caused by blood clots. Most strokes are caused by a blood clot which then reduces blood flow in the affected part of the brain. Without an adequate blood supply, the brain quickly suffers damage which is often permanent. Drugs which can thin blood and improve brain blood flow might reduce damage and improve outcome after stroke. Prostacyclin and related drugs have the ability to thin blood and increase brain blood flow. This systematic review assesses whether this type of drug improves outcome after stroke. The review identified five small trials which, when taken together, did not find any benefit. The limited amount of data mean that there is no evidence at present to suggest that prostacyclin and related drugs should be used in acute stroke.

Background

Stroke is the third most common cause of death in the Western world and the most common cause of long‐term adult disability. However, no acute therapeutic intervention has yet been shown to be effective in reducing mortality or morbidity. Prostacyclin is an endothelium‐derived prostenoid which has vasodilating, antiplatelet (Moncada 1983), antileucocyte (Bath 1991), fibrinolytic and cytoprotective effects. Prostacyclin synthesis appears to be reduced in stroke (Gryglewski 1982) whilst cerebral infarction is characterised by thrombosis, platelet and leucocyte aggregation, and leucocyte infiltration. Hence, prostacyclin is a candidate treatment for acute ischaemic stroke.

Pre‐clinical studies suggest that prostacyclin may be effective in animal models of cerebral infarction (e.g. Akopov 1992). Several non‐randomised trials of prostacyclin in acute ischaemic stroke have been reported which suggest that prostacyclin reduces morbidity following stroke and is safe to administer (Gryglewski 1982; Gryglewski 1983; Hakim 1984; Miller 1984; Miller 1985; Pokrupa 1986). As a result, a number of randomised controlled trials in acute ischaemic stroke have been undertaken. This Cochrane review presents an overview analysis of these randomised controlled trials.

Objectives

To determine whether prostacyclin is a safe treatment for patients with ischaemic stroke when administered acutely and whether it reduces the risk of early and late death.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled parallel group trials examining the effects of prostacyclin administered within one week of acute presumed ischaemic stroke.

Types of participants

Patients with acute stroke, where attempts were made to exclude primary intracerebral haemorrhage, were included in the analysis.

Types of interventions

Intravenous prostacyclin or analogue versus placebo. The analogues considered were: TRK‐100, ONO‐41483, HOE 892, OP‐2507 and ZK 36374.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the frequency of early (within one month) death. The only secondary outcome was late (within eighteen months) death from all causes. Morbidity was not analysed since the trial publications do not give sufficient information.

Search methods for identification of studies

See: 'Specialized register' section in Cochrane Stroke Group

Relevant trials were identified in the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register, which was last searched by the Review Group Co‐ordinator in November 2003.

For the first version of this review, we also searched EMBASE (1980 to 1999), MEDLINE (1966 to 1999), Science Citation Index (1981 to 1999), and the Ottawa Stroke Trials Registry. Electronic search terms included: (stroke or cerebr*) and (prostacyclin or epoprostenol or ciprostene or clioprost or iloprost or isocarbacyclin or beraprost or TRK‐100 or ONO‐41483 or HOE 892 or OP‐2507 or ZK 36374); the latter compounds are analogues of prostacyclin.

In an effort to identify unpublished trials, we contacted the manufacturers of prostacyclin: Wellcome Foundation, UK, and Upjohn Company, UK. Additional information was sought from the principal investigators of the identified trials. Reviews of prostacyclin in cerebrovascular disease were also searched (Chen 1986; Martindale 1993; Moncada 1983). Note: prostacyclin was first identified in 1976 and studied in man in 1978.

Data collection and analysis

We (PB, FB) selected trials for inclusion in the review and sought additional information from the principal investigators of all trials that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria.

We noted information on the methods of randomisation, blinding, analysis, the number of patients randomised, dose and timing of prostacyclin or analogue, patient withdrawals, and the number of deaths occurring in each trial. The primary outcome was early (within one month) death.

We tested for heterogeneity and calculated a weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across trials (odds ratio) using the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 4.2.

Results

Description of studies

Five trials, each of which used sodium prostacyclin, met our inclusion criteria and have been included in the analysis, as summarised in Characteristics of included studies. One further trial of 427 patients, published within a paper which also describes several non‐stroke studies, involved the administration of a prostacyclin analogue (Mizushima 1994); this trial has been excluded as no information has been received from the authors. Altogether, five trials were excluded (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

The average age of the patients in the trials was approximately 65 years, and slightly more men than women were included.

Risk of bias in included studies

Prostacyclin caused frequent but essentially mild adverse effects (e.g. headaches, nausea, 'warmth', dizziness, and facial flushing); as a result, it is unlikely that any of the trials of prostacyclin were ever truly blinded since both patients and staff may have been aware whether drug or placebo was administered. Two trials used independent neurological assessors who were not present during infusions to minimise bias in outcome assessment (Martin 1985; Pokrupa 1986); at present, this is of no relevance to this review because death is the only available outcome.

Three of the included trials delayed administration of prostacyclin until after 24 hours following stroke onset to exclude patients with transient ischaemic attack. Hsu studied all patients within 24 hours (Hsu 1986) whilst Pokrupa included patients up to 48 hours post‐ictus (Pokrupa 1986). Only one trial reported deaths at one year (Martin 1985). Three trials used CT scans to exclude cerebral haemorrhage (Hsu 1986; Martin 1985; Pokrupa 1986); the other two used a combination of EEG and CSF analysis (Huczynski 1985; Huczynski 1988) which means that some patients with primary intracerebral haemorrhage may have inadvertently been studied.

One trial randomised patients by sealed numbered opaque envelope (Pokrupa 1986); the other trial reports do not give explicit information on how randomisation was undertaken although all declare they were randomised. Furthermore, none of the studies explicitly state that they were analysed by intention to treat; however, it is clear in three trials that no patients were lost to follow up (Huczynski 1985; Martin 1985; Pokrupa 1986). However, we have performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis since outcome data relating to deaths are available for all patients whether withdrawn from treatment or not.

Effects of interventions

The total number of participants included in the five analysed trials amounted to 191. There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity in the analysis (Chi = 0.78, 2P > 0.1). The five trials showed a non‐significant 37% reduction in the odds of early death (within one month) (95% confidence interval (CI), 78% reduction to 85% excess); however, this difference is due to three less deaths in the prostacyclin group across two trials (Hsu 1986; Pokrupa 1986). Only one trial assessed late deaths (total deaths at 10 to 18 months) and found no difference although the confidence intervals were wide (Martin 1985).

Prostacyclin is a vasodilator which induces dose‐dependent falls in blood pressure. Hypotension during the acute phase of stroke may be associated with poor outcome (Bath 1995). Four of the trials reported the effect of prostacyclin on blood pressure; Martin and Pokrupa found no statistical difference between active and placebo groups with respect to blood pressure and heart rate (Martin 1985; Pokrupa 1986). Two patients receiving prostacyclin in the former study had to have the dose halved because of hypotension (Martin 1985). In contrast, Hsu reported that prostacyclin reduced blood pressure and increased heart rate (Hsu 1986). Although Huczynski did not compare active and placebo groups, one patient receiving prostacyclin was withdrawn from the trial because of hypotension (Huczynski 1988). One trial found that facial flushing, a recognised adverse effect of prostacyclin, occurred in six patients receiving active medication but none taking placebo (Hsu 1986). Eleven patients in one study had the prostacyclin infusion rate reduced due to the development of adverse effects (Pokrupa 1986).

Discussion

This review analyses apparently randomised controlled trials of intravenous prostacyclin in acute ischaemic stroke. The results do not support the hypothesis that prostacyclin reduces early all cause case fatality. However, the confidence intervals are wide reflecting the low numbers of patients studied, and prostacyclin could equally reduce short‐term case fatality by 78% or increase it by 85%. One trial examined the effect of prostacyclin on late deaths and found no difference. The protocols used can be criticised in the light of current practice. Firstly, prostacyclin was only administered to all patients within 24 hours of stroke onset in one trial; three other trials delayed treatment beyond 24 hours when ischaemic damage is likely to be fixed and not amenable to pharmacological intervention. Secondly, prostacyclin was administered discontinuously in four trials leading to the potential for rebound vasoconstriction and platelet/leucocyte activation between infusions. Thirdly, two trials used EEG and CSF criteria to exclude primary intracerebral haemorrhage which raises the possibility that patients with haemorrhage were included. Lastly, it is currently unclear how patients were randomised in four of the five studies.

In spite of the biological rationale for administering prostacyclin in acute ischaemic stroke, it is also possible that it may worsen outcome since infusions in normal people paradoxically reduce cerebral blood flow (Brown 1982; Cook 1983).

In summary, analysis of five trials of prostacyclin do not show evidence that it reduces case fatality following acute presumed ischaemic stroke. However, the numbers of trials and participants studied were too small and trial designs were suboptimal so that further research is required.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Prostacyclin should not currently be used in the routine management of acute ischaemic stroke.

Implications for research.

The existing trials show no evidence that prostacyclin is harmful or beneficial in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. However, the trials included few patients and mostly administered prostacyclin late (after 24 hours) and in a discontinuous fashion. Hence, one or more larger trials of prostacyclin, or a longer acting analogue, are warranted in acute ischaemic stroke. It is suggested that a new trial might enrol upwards of 2000 patients within 12 hours of the onset of ischaemic stroke. Prostacyclin or analogue should be infused over five days continuously, as in (Hsu 1986), to prevent potential rebound platelet hyperfunction (Sinzinger 1981) and perhaps reduce adverse effects. Aspirin would be given to all patients, as is standard now, with the benefit of inhibiting the endogenous synthesis of vasoconstricting proaggregatory prostenoids (e.g. thromboxane A2) (Huczynski 1988).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1995 Review first published: Issue 1, 1995

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 March 2004 | New search has been performed | November 2003

January 1998

January 1996

NOTE: This review covers an area where no active research is taking place. It will be updated if relevant information becomes available, e.g. on completion of an appropriate study. |

Notes

NOTE: This review covers an area where no active research is taking place. It will be updated if relevant information becomes available, e.g. on completion of an appropriate study.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Wojtek Rakowicz for translating the Polish language paper, Dr David Moher of the Ottawa Stroke Trials Registry for helping to identify relevant trials, the individual prostacyclin trialists for providing further information, and to the Cochrane Stroke Group Editorial Board and external peer reviewers for making constructive comments on this review. Dr Philip Bath was Wolfson Senior Lecturer in Stroke Medicine, and is Stroke Association Professor of Stroke Medicine. Dr Fiona Bath contributed (co‐ordination, searching, data collation, management, entry, and analysis) to the first version of the review.

Ongoing trials

We are not aware of any ongoing trials of prostacyclin or analogues and would be grateful to be informed of any, or of any other relevant trials not covered here.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Prostacyclin vs control in ischaemic stroke: all trials.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All cause case fatality, early (within 4 weeks) | 5 | 191 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.22, 1.85] |

| 2 All cause case fatality, late (up to 18 months) | 1 | 32 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.26, 3.91] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostacyclin vs control in ischaemic stroke: all trials, Outcome 1 All cause case fatality, early (within 4 weeks).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Prostacyclin vs control in ischaemic stroke: all trials, Outcome 2 All cause case fatality, late (up to 18 months).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Hsu 1986.

| Methods | Randomisation technique not stated Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial Analysis by intention to treat Stratified by thrombotic and embolic CI Five centre trial | |

| Participants | USA 49 males, 31 females Mean age 64 years Stroke type: atherothrombotic 66, embolic 14 Enrolment within 24 hours 100% CT pre‐entry | |

| Interventions | Rx: PGI2 (epoprostenol sodium, Upjohn Co, USA, and Wellcome, Foundation, UK) Pl: buffer/diluent | |

| Outcomes | Death at 4 weeks Neurological impairment assessed using Turnhill score at entry, day 3, weeks 1, 2 + 4 | |

| Notes | Ex: stupor, coma, psychiatric disorder, clinical intracranial hypertension, organ or systemic disease, bleeding risk, heparin FU: 4 weeks Further information unavailable because original data discarded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Huczynski 1985.

| Methods | Randomisation technique not stated Double‐blind, placebo controlled No loss to FU | |

| Participants | Poland 15 male, 11 female Mean age 67 years Enrolment between 48 hours and 5 days 100% EEG and CSF pre‐entry diagnosis of CI | |

| Interventions | Rx: PGI2 (epoprostenol, Wellcome, UK, and Upjohn Co, USA), 5 x 6 hour consecutive 2.5 to 5 ng/kg/min iv infusions (depending on patients tolerance), separated by 6 hour intervals Pl: solvent Duration: 54 hours | |

| Outcomes | Death at 2 weeks Neurological impairment assessed using modified Matthew score at baseline, after 6 and 54 hours, 2 weeks | |

| Notes | Ex: heart failure, hyperglycaemia, uraemia, hyperpyrexia, previous stroke FU: 2 weeks Further information unavailable since original data discarded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Huczynski 1988.

| Methods | Randomisation technique not stated Double‐blind, placebo controlled Not intention‐to‐treat Withdrawals: PGI2 4, Pl 1 from treatment | |

| Participants | Poland 16 male, 14 female Mean age 61 years Enrolment 24 to 72 hours after CI 100% EEG and CSF pre‐entry diagnosis of CI | |

| Interventions | Rx: PGI2 (Wellcome, UK, or Chinoin, WRL), daily 6 hour iv infusions at 2.5 to 5 ng/kg/ min Pl: glycine solvent Duration: 2 weeks All patients given low molecular weight dextran | |

| Outcomes | Death at 4 weeks Neurological impairment assessed using modified Matthew score assessed at baseline, after each infusion, 3 and 4 weeks | |

| Notes | Ex: heart failure, hyperglycaemia, uraemia, arrhythmia, hyperpyrexia, previous stroke, mild stroke FU: 4 weeks | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Martin 1985.

| Methods | Randomisation technique not stated (randomisation in blocks of 4) Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled Not intention‐to‐treat Withdrawal: PGI2 1 from treatment | |

| Participants | UK. 32 patients (gender numbers not given) Mean age 68 years Enrolment between 24 and 36 hours of stroke 100% CT exclusion of PICH | |

| Interventions | Rx: PGI2 (epoprostenol, Wellcome, UK), 5 x 6 hour alternating prostacyclin 5 ng/kg/min and saline iv infusions Pl: solvent Duration: 54 hours | |

| Outcomes | Death at 2 weeks and 10 to 18 months Neurological impairment assessed using modified Matthew Score, Token speech test, and WHO disability status at 2 and 4 weeks CT infarct volume at 2 weeks Cerebral blood transit time pre and post‐infusion | |

| Notes | Ex: ICH FU: 2 weeks and 10 to 18 months Further information unavailable since original data discarded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Pokrupa 1986.

| Methods | Randomisation by sealed numbered opaque envelope Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, single‐centre trial Intention‐to‐treat No loss to FU | |

| Participants | Canada 11 male, 12 female Mean age 63 years 100% CT pre‐entry Enrolment within 48 hours of ictus | |

| Interventions | Rx: PGI2 ("Cycloprostin", Upjohn Co., USA) 5 daily 8 hour consecutive infusions weaned up from 2 to 10 ng/kg/min and tapered over last hour Pl: sterile diluent buffer (NaCl 0.147 w/v, glycine 0.188 w/v, NaOH, pH 10.5 +/‐ 0.3) Duration: 5 days | |

| Outcomes | Death at 5 days, and 1, 2 and 4 weeks Neurological impairment rating at 5 days, and 1, 2 and 4 weeks CT and PET at 5 to 9 days | |

| Notes | Ex: coma, complicating neurological conditions, heparin, malignant hypertension, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, heart attack within 2 months, recent surgery FU: 5 days, and 1, 2, and 4 weeks Original data available | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

CI: cerebral infarction Ex: exclusion FU: follow up PICH: primary intracerebral haemorrhage iv: intravenous PGI2: prostacyclin Pl: placebo Rx: treatment

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Hakim 1984 | 5 patients with acute ischaemic stroke (< 48 hours of onset) given prostacyclin (2 to 10 ng/kg/min iv over 8 hours daily for 5 days) Excluded: non‐controlled study |

| Hoshi 1990 | Patients post cerebral infarction Excluded: (i) cross‐over trial; (ii) one month post stroke, i.e. trial not acute |

| Isaka 1990 | 5 patients with carotid atheroma post ischaemic stroke Assessment of carotid platelet deposition (indium 111 scintigraphy) on TRK‐100 or placebo Excluded: (i) crossover trial; (ii) no relevant outcomes |

| Mizushima 1994 | Patients with mixed group of diagnoses Excluded: (i) data relating to stroke patients unavailable |

| Zhao 1991 | 18 patients with acute cerebral infarction (< 72 hours of onset) given prostacyclin (2‐5 ng/kg/min iv; n = 11) versus dextran (n = 7) Excluded: (i) confounded; (ii) not randomised |

Contributions of authors

Philip Bath: conceived and designed the review, developed the search strategy, interpreted the data, wrote and updated the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Wolfson Foundation, UK.

South Thames NHS R&D Executive, UK.

Stroke Association, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Hsu 1986 {published and unpublished data}

- Hsu CY, Faught Jn RE, Furlan AJ, Coull BM, Huang EL, Hogan EL, et al. Intravenous prostacyclin in acute nonhemorrhagic stroke: a placebo‐controlled double‐blind trial. Stroke 1986;18:352‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent IC, Huang DC, Linet OI. Randomized, controlled clinical trial of Cyclo‐prostin (epoprostenol, prostacyclin, PGI2) in acute atherothrombotic strokes and embolic strokes of cardiac origin (multi‐clinic protocol 1088 ‐ Investigators: Drs Coull, Faught, Furlan, Hogan, and Yatsu). Upjohn Company Technical Report 7250/85/007 1985.

- Linet O, Hsu CY, Faught RE, Hogan EL, Furlan AJ, Coull BM, et al. Epoprostenol in acute stroke. Stroke 1985;16:149. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsu FM, Grotta JC, Pettigrew LC, Gray CS. Prostacylin infusion for acute ischaemic strokes: Results of a double‐blind study. In: Battistini N, Fiorani P, Courbier R, Plum F, Fieschi C editor(s). Acute brain ischaemia: medical and surgical therapy. 1st Edition. New York: Raven Press, 1986:263‐271. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsu FM, Grotta JC, Pettigrew LC, Gray JD, Hogan EL, Hsu CY, et al. Prostacyclin infusions in acute ischaemic strokes. Royal Society of Medicine Services International Congress and Symposium Series No 99. In: Clifford Rose F editor(s). Stroke: epidemiological, therapeutic and socio‐economic aspects. 1st Edition. London: Royal Society of Medicine Services Limited, 1986:73‐9. [Google Scholar]

Huczynski 1985 {published data only}

- Huczynski J, Kostka‐Trabka E, Sotowska W, Bieron K, Grodzinska L, Dembinska‐Kiec A, et al. Double‐blind controlled trial of the therapeutic effects of prostacyclin in patients with completed ischaemic stroke. Stroke 1985;16:810‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Huczynski 1988 {published data only}

- Huczynski J, Gryglewski RJ, Kostka‐Trabka E, Dembinska‐Kiec A, Pykosz‐Mazur E, Sotowska W, et al. Use of prostacyclin in patients with ischemic stroke. A double‐blind method II. Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska 1988;22:299‐304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martin 1985 {published data only}

- Hamdy NAT, Martin JF, Nicholl J, Owen P, Lewtas N, Bergvall UB, et al. Controlled trial of prostacyclin in acute cerebral infarction. Clinical Science 1984;66 (Suppl):48P. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JF, Hamdy N, Nicholl J, Lewtas N, Bergvall U, Owen P, et al. Prostacyclin in cerebral infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 1985;312:1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JF, Handy N, Nicholl J, Lewtas N, Bergvall U, Owen P, et al. Double‐blind controlled trial of prostacyclin in cerebral infarction. Stroke 1985;16:386‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pokrupa 1986 {published and unpublished data}

- Pokrupa A, Hakim J, Villanueva G, Francis G, Wolfe L. Clinical study of prostacyclin infusion after acute ischemic stroke. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1986;13:165. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrupa R, Hakim A, Villanueva J, Meyer E, Diksic M, Evans A. PET evaluation of blood flow and metabolic changes induced by PGI2 therapy in patients with ischemic stroke. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1986;13:188. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrupa RP, Hakim AM, Villanueva JA, Diksic M, Evans AE, Meyer E, et al. Prostacyclin infusion after acute cerebral infarction: clinical and PET studies. Unpublished manuscript.

References to studies excluded from this review

Hakim 1984 {published data only}

- Hakim AM, Pokrupa RP, Wolfe LS. Preliminary report on the effectiveness of prostacylin in stroke. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1984;11(3):409 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

Hoshi 1990 {published data only}

- Hoshi K, Mizushima Y. A preliminary double‐blind cross‐over trial of lipo‐PGI2, a prostacyclin derivative incorporated in lipid microspheres, in cerebral infarction. Prostaglandins 1990;40(2):155‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Isaka 1990 {published data only}

- Isaka Y, Imaizumi M, Mieno M, Uehara A, Hashikawa K, Handa N, et al. Potency of TRK‐100 (oral active prostacyclin analogue) as an antiplatelet agent as assessed by indium 111 platelet scintigraphy. Stroke 1990;21(suppl 1)(8):I‐160 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

Mizushima 1994 {published data only}

- Mizushima Y, Toyota T, Okita K, Ohtomo E. Recent clinical studies on lipo‐PGE1 and lipo‐PGI2: PGE1 and PGI2 incorporated in lipid microspheres, for targeted delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 1994;28:243‐9. [Google Scholar]

Zhao 1991 {published data only}

- Zhao J. Treatment of acute cerebral infarction with PGI2 ‐ evaluating the clinical effect and observation of dynamic changes in plasma TXB2 and 6‐keto PGF1 alpha levels. Chung Hua Shen Ching Ching Shen Ko Tsa Chih 1991;24:138‐40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Akopov 1992

- Akopov S, Ghazarian A, Gabrielian E. Effects of nimodipine and nicergolin on cerebrovascular injuries induced by activation of platelets and leukocytes in vivo. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie 1992;318:66‐75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bath 1991

- Bath PMW, Hassall DG, Gladwin A‐M, Palmer RMJ, Martin JF. Nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Divergence of inhibitory effects on monocyte chemotaxis and adhesion to endothelium in vitro. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis 1991;11:254‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bath 1995

- Bath PMW, Bath FJ. Blood pressure management in acute stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1995, Issue 2. [Google Scholar]

Brown 1982

- Brown MM, Pickles H. Effect of epoprostenol (prostacyclin, PGI2) on cerebral blood flow in man. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 1982;45:1033‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 1986

- Chen ST, Hsu CY, Hogan EL, Halushka PV, Linet OI, Yatsu FM. Thromboxane, prostacyclin, and leukotrienes in cerebral ischemia. Neurology 1986;36:466‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1983

- Cook PJ, Maidment CG, Dandona P, et al. The effect of intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin, PGI2) on cerebral blood flow and cardiac output in man. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1983;16:707‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gryglewski 1982

- Gryglewski RJ, Nowak S, Kostka‐Trabka E, Bieron K, Dembinska‐Kiec A, Blaszczyk B, Kusmiderski J, Markowska E, Szmatola S. Clinical use of prostacyclin (PGI2) in ischaemic stroke. Pharmacological Research Communications 1982;14:879‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gryglewski 1983

- Gryglewski RJ, Nowak S, Kostka‐Trabka E, Kusmiderski J, Dembinska‐Kiec A, Bieron K, et al. Treatment of ischaemic stroke with prostacyclin. Stroke 1983;14:197‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Martindale 1993

- Reynolds JEF (ed). Martindale, the extra pharmacopoeia. 30th Edition. London: The Pharmaceutical Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Miller 1984

- Miller VT, Coull BM, Yatsu FM, Shah AB, Beamer NB. Prostacyclin infusion in acute cerebral infarction. Neurology 1984;34:1431‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miller 1985

- Miller VT, Coull BM, Yatsu FM, Shah AB, Beamer NB. Prostacyclin therapy for acute stroke. In: Plum F, Pulsinelli W editor(s). Cerebrovascular Diseases. New York: Raven Press, 1985:235‐9. [Google Scholar]

Moncada 1983

- Moncada S. Biology and therapeutic potential of prostacyclin. Stroke 1983;14:157‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sinzinger 1981

- Sinzinger H, Silberbauer K, Horsch AK, Gall A. Decreased sensitivity of human platelets to PGI2 during long‐term intra‐arterial PGI2 infusion in patients with peripheral vascular disease ‐ a rebound phenomenon?. Prostaglandins 1981;21:49‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]