Abstract

Background

Carotid patches for carotid endarterectomy may be made from an autologous vein or synthetic material.

Objectives

To assess the safety and efficacy of different materials for carotid patch angioplasty.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register (last searched 3 August 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2009), MEDLINE (1966 to November 2008), EMBASE (1980 to November 2008) and Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings (1980 to 2008). We handsearched relevant journals and conference proceedings, checked reference lists, and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials comparing one type of carotid patch with another for carotid endarterectomy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed eligibility, trial quality, and extracted data.

Main results

We included 13 trials involving a total of 2083 operations; seven trials compared vein closure with PTFE closure, and six compared Dacron grafts with other synthetic materials. In most trials a patient could be randomised twice and have each carotid artery randomised to different treatment groups. There were no significant differences in the outcomes between vein patches and synthetic materials apart from pseudoaneurysms where there were fewer associated with synthetic patches than vein patches (odds ratio (OR) 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.02 to 0.49). However, the numbers involved were small and the clinical significance of this finding is uncertain. Compared to other synthetic patches, Dacron was associated with a higher risk of: perioperative combined stroke and transient ischaemic attack (P = 0.03); restenosis at 30 days (P = 0.004); perioperative stroke (P = 0.07) and perioperative carotid thrombosis (P = 0.1). During follow‐up for more than one year, there were also significantly more strokes (P = 0.03), stroke/death (P = 0.02) and arterial restenoses (P < 0.0001) with Dacron but the numbers of outcomes were small and the significance of this finding is uncertain.

Authors' conclusions

The number of outcome events is too small to allow reliable conclusions to be drawn and more trial data are required to establish whether any differences do exist. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that other synthetic (e.g. PTFE) patches may be superior to collagen impregnated Dacron grafts in terms of perioperative stroke rates and restenosis. Pseudoaneurysm formation may be more common after use of a vein patch compared with a synthetic patch.

Plain language summary

Patches of different types for carotid patch angioplasty

About 20% of strokes result from narrowing of the carotid artery (the main artery supplying blood to the brain). Carotid endarterectomy is an operation that involves opening the carotid artery to remove this narrowing and therefore reduce the risk of stroke. However, there is a 5% to 10% risk of the operation itself causing a stroke. There is evidence that, at the end of the operation when the artery is being closed, inserting a patch into the gap in the artery reduces the risk of strokes. Patches are made out of either synthetic material or the patient's own vein. This review aimed to assess whether one type of patch was better than another; however, the 13 trials reviewed did not provide clear evidence about which type of patch material is best. Vein patches may rupture with potentially fatal consequences and synthetic materials are vulnerable to infection. Further research is needed.

Background

Carotid endarterectomy has been shown in large, well‐conducted randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to reduce the risk of stroke in patients with recently symptomatic, severe (greater than 70%) internal carotid artery stenosis (ECST 1991; ECST 1998; NASCET 1991; NASCET 1998). There is also some evidence that it may be beneficial for some categories of asymptomatic patients (ACAS 1995). What is less clear at present is whether different surgical techniques affect the outcome, although there is increasing evidence that the use of carotid patch angioplasty is superior to primary closure in reducing the risk of restenosis and improving both short and long‐term clinical outcome (Counsell 1998). Consequently, many vascular surgeons use carotid patching either routinely or selectively. However, there is still considerable debate over the choice of patch material. Vein patching (usually harvested from the saphenous vein and sometimes from the jugular vein) is favoured by some on the basis that a non‐randomised comparison suggested that it was better at preventing stroke or death (Fode 1986). It also has the advantages of being easily available, easy to handle and possibly has a greater resistance to infection. Synthetic material, such as Dacron or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), is favoured by others who feel that it offers a lower risk of patch rupture (Murie 1994) and aneurysmal dilatation (Gonzalez 1994), and also that it spares the morbidity associated with saphenous vein harvesting and leaves the vein which may be required for coronary bypass grafting at a later date. It is also possible that one type of synthetic material is better than another. For example, AbuRahma et al found PTFE resulted in significantly fewer perioperative carotid thromboses and strokes than Dacron (AbuRahma 2002). Finally, there are less commonly used materials such as bovine pericardium (Kim 2001) which have yet to be widely accepted.

The most reliable evidence on the best material to use comes from randomised trials and so we have reviewed the randomised trials comparing different types of patch material in carotid endarterectomy.

Objectives

We wished to assess the safety and efficacy of different types of patch material in carotid patch angioplasty. The primary hypothesis was that synthetic material was associated with a lower risk of patch rupture than venous patches, but that venous patches were associated with lower risk of perioperative stroke and early and late infection.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought to identify all unconfounded randomised trials in which one type of carotid patch was compared to another. Quasi‐randomised trials in which allocation to different treatment regimens was not adequately concealed (e.g. allocation by alternation, date of birth, hospital number, day of the week or by using an open random number list) could also be included.

Types of participants

We considered trials which included any type of patient undergoing carotid endarterectomy eligible, whether the initial indication for endarterectomy was symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid disease.

Types of interventions

We sought to identify all trials comparing one type of patch material with another in carotid endarterectomy. The materials currently available include saphenous vein (harvested from either the ankle or the groin), Dacron, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) polyester or polyurethane.

Types of outcome measures

We aimed to extract from each trial the number of patients originally allocated to each treatment group to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. Within each treatment group we then extracted the number of patients:

who died within 30 days of the operation and during subsequent follow‐up; we tried to classify each death as stroke‐related or not;

who had any stroke (fatal, non‐fatal, contralateral, ipsilateral, brainstem, haemorrhage, or infarct) within 30 days of the operation and during subsequent follow‐up; we also performed a separate analysis of strokes ipsilateral to the endarterectomy.

We also tried to extract the number of arteries that:

became occluded within 30 days of the operation;

developed a significant complication related to surgery, e.g. haemorrhage from or rupture of the artery, infection of the endarterectomy site, or cranial nerve palsy;

developed restenosis greater than 50% (including occlusion), or a pseudoaneurysm (as defined in each trial) during follow‐up.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module.

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor in August 2009. We also updated the electronic searches and handsearched additional issues of relevant journals as follows.

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2009), MEDLINE (1966 to November 2008) (Appendix 1), EMBASE (1980 to November 2008) (Appendix 2) and Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings (1980 to November 2008), which was searched using the terms "carotid" and ("trial* or random*").

-

We handsearched the following journals including conference supplements:

Annals of Surgery (1981 to September 2008);

Annals of Vascular Surgery (1994 to September 2008);

Cardiovascular Surgery (now Vascular) (1994 to September 2008);

European Journal of Vascular Surgery (now European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery) (1987 to September 2008);

Journal of Vascular Surgery (1994 to September 2008);

Stroke (1994 to September 2008).

We reviewed the reference lists of all relevant studies.

We contacted experts in the field to identify further published and unpublished studies.

-

For the previous version of the review:

-

we handsearched the following journals including conference supplements:

American Journal of Surgery (1994 to 2001);

British Journal of Surgery (1985 to 2001);

World Journal of Surgery (1978 to 2001).

-

we handsearched abstracts of the following meetings for the years 1995 to 2001:

AGM of the Vascular Surgical Society (UK);

AGM of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland;

American Heart Association Stroke Conference;

Annual Meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery (USA);

The European Stroke Conference.

-

We did not apply any language restriction in the searches and arranged translation of all possibly relevant non‐English language publications.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (KR) selected those trials that met the inclusion criteria and another review author (PMR) independently reviewed these decisions. We resolved all disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

The same two review authors also assessed the methodological quality of each trial. We decided not to use a scoring system to assess quality but simply to record the following details: the randomisation method, the blinding of the clinical and Doppler assessments, whether outcomes were reported for all patients originally randomised in each group irrespective of whether they received the operation they were allocated to or whether the patient was excluded after randomisation, and the number of patients lost to follow up. We sought data on the number of outcome events in all patients originally randomised to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis. We triple‐checked all data extraction. In addition, we also extracted details about the patients included in the trial, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the comparability of the treatment and control groups for important prognostic factors, the type of patch, the type of anaesthetic, the use of shunts, and the use of antiplatelet therapy during follow‐up. Much of the above data were not available from the publications, and so we sought further information from the trialists in all cases; however, we did not always receive a response.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All of the trials randomised the artery rather than the patient and all included patients who had bilateral carotid endarterectomies. It was, therefore, possible for a single patient to have both types of patch material. In these patients, it would be difficult to relate death or stroke to one particular procedure. In the previous version of this review, in trials where it was possible for a patient to have both procedures, death and any stroke were only analysed in those who had unilateral procedures or the same procedure to both arteries. Where data were not obtainable from the authors of relevant trials the whole trial was excluded from the analysis (Lord 1989). Of the five studies published since 1995, two ensured that patients undergoing more than one operation were assigned the same closure method (Hayes 2001; O'Hara 2002) whereas three did not (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Katz 1996). However, most patients who undergo more than one operation will have a period of at least 30 days between the procedures, therefore short‐term results are likely to be reliable regardless of how data are analysed. Only one of the later studies reported long‐term follow‐up (AbuRahma 1996) but the number of bilateral operations are small compared with the total number of operations carried out and unlikely to bias the results significantly. Therefore, this trial was retained but this should be born in mind when interpreting results.

A separate analysis of only strokes ipsilateral to the operated artery was also performed for each artery. However, the total number of strokes was very similar to the number of ipsilateral strokes, since in the majority of studies all the strokes were ipsilateral. Arterial complications such as occlusion, haemorrhage from the endarterectomy site, restenosis, infection at the operation site, or pseudoaneurysm formation were analysed for all arteries rather than patients. The analyses based on arteries assumed that, in patients who had bilateral endarterectomies, outcome events in each carotid artery were independent.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated proportional risk reductions based on a weighted estimate of the odds ratio (OR) using the Peto method (APT 1994). We calculated absolute risk reductions from the crude risks of each outcome in all trials combined.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between study results using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This examined the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. Values of I2 over 75% indicate a high level of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Since foreknowledge of treatment allocation might lead to biased treatment allocation and exaggerated treatment effects (Schulz 1995), separate sensitivity analyses of those trials where allocation concealment was secure and those where it was less secure were performed in the first version of this review. However, since no significant difference was found between the trials with different allocation techniques, and because no studies in this later review were quasi‐randomised, we did not plan to carry out sensitivity analyses for this version of the review.

Results

Description of studies

The previous version of this review (Bond 2004) included eight trials involving a total of 1480 operations. Since that time there have been many retrospective reports examining different patch types. However, these only included five relevant randomised trials of a sufficient standard to be included in this review and increased the total number of trials to 13 with 2083 operations available for analysis. Two of the five later trials compared vein to PTFE (Grego 2003) and polyester patch (Meerwaldt 2008), one compared Dacron with PTFE patching (AbuRahma 2007) and the rest compared Dacron with other synthetic materials, namely polyurethane patch (Albrecht‐Fruh 1998) and bovine pericardium (Marien 2002). One pre‐1995 and one post‐1995 trial had three arms; saphenous vein patching, PTFE patching and primary closure (AbuRahma 1996; Lord 1989). Only the results from the vein patching and PTFE patching group are included in this review.

Four trials compared saphenous vein harvested from the groin with synthetic patches (Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Ricco 1996). Two trials used saphenous vein from the ankle (Gonzalez 1994; Meerwaldt 2008), one trial alternately used vein from the jugular and from the saphenous vein at the ankle (AbuRahma 1996) and one trial used vein from the external jugular vein (Grego 2003). One trial did not specify a site (O'Hara 2002). In all trials the operations were all performed under general anaesthetic, and most were also performed with shunting. All patients received antiplatelet therapy perioperatively. One study used heparin reversal at the end of surgery in 30% of their synthetic closures but none in their vein closure patients (Katz 1996). One used it in all patients (Gonzalez 1994), five used reversal in none (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Ricco 1996) and data were unavailable in six cases (Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002).

Early (within 30 days) postoperative arterial occlusion was assessed by duplex sonography or angiography in 10 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Gonzalez 1994; Grego 2003; Ricco 1996; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008) and based on symptoms only in two trials (Katz 1996; Lord 1989). During long‐term follow‐up, restenosis of the arteries was assessed by Duplex ultrasound in 10 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996) and by Doppler ultrasound and intravenous digital subtraction angiography in another (Gonzalez 1994). Two trials only provided data on ipsilateral strokes and it is unclear whether any other strokes occurred during follow‐up (Lord 1989; Ricco 1996).

In the pre‐2002 review the average age of patients involved in the trials was about 67.5 years, 60% to 80% were male and less than 36% of operations were performed for asymptomatic carotid disease. In the studies since 2002, the average age was 67.6 years, 50% to 80% were male, and 41% of the operations were performed for asymptomatic carotid disease (excluding one study which intended to do only symptomatic patients (Meerwaldt 2008)). One trial only included patients with narrow internal carotid arteries (less than 5 mm external diameter) and also excluded patients with recurrent carotid stenosis (Ricco 1996), whereas two trials excluded patients with internal carotid diameters less than 4 mm (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002). All but two trials excluded patients undergoing either recurrent carotid endarterectomy or combined coronary and carotid surgery at the same time (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996), one excluded no patients at all (Gonzalez 1994) and one did not give information on exclusions (Lord 1989). In all but four of the trials the treatment groups were comparable for important prognostic factors. Two trials had significantly more males in the synthetic group than the vein patch group (Grego 2003; O'Hara 2002). Another two trials had significantly different stroke rates between the two groups (Marien 2002; Meerwaldt 2008).

Risk of bias in included studies

There were several significant flaws in the trials. However, the trials published after 2002 were generally of better quality than those before. Up to 2002 six out of 10 reported a method of randomisation (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Hayes 2001; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996), after 2002 all three trials reported a method of randomisation (AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008). Adequately concealed allocation was performed in seven of the 10 pre‐2002 trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; Gonzalez 1994; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996) and after 2002 all three trials had adequately concealed allocation (AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008). Eight trials attempted to perform blind follow‐up (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Grego 2003; Hayes 2001; Meerwaldt 2008; O'Hara 2002; Ricco 1996). One trial did not blind outcome assessments and only followed the patients until hospital discharge (Lord 1989). As mentioned previously, one of the main flaws in all the trials was that a patient undergoing bilateral carotid endarterectomy could be randomised twice and have each carotid artery randomised to different treatment groups. In these trials, it was unclear from the published reports how many patients in each group had bilateral procedures that were different in each artery, and whether any deaths or strokes occurred in these patients. True intention‐to‐treat analyses were possible in seven trials (AbuRahma 1996; AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007; Gonzalez 1994; Hayes 2001; Lord 1989; O'Hara 2002).

Effects of interventions

We included data from 13 trials, involving 2083 operations, in this review. The results presented may differ from those in the published reports where we have obtained additional information from the study authors. There was no statistical heterogeneity in any of the analyses except two: outcome of perioperative ipsilateral stroke and long‐term arterial occlusion between Dacron and PTFE (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 4.5).

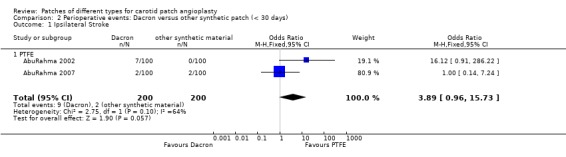

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 1 Ipsilateral Stroke.

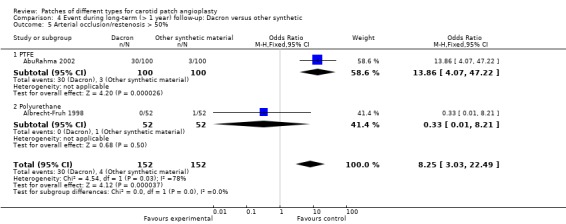

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 5 Arterial occlusion/restenosis > 50%.

Operative details

Duration of operation

The duration of operation was not analysed statistically because there was evidence that the durations were not normally distributed. However, synthetic patching was associated with significantly longer operation times than vein patching in three trials: mean times were 128 minutes versus 112 minutes (Gonzalez 1994), 105 minutes versus 89 minutes (Ricco 1996) and 100 minutes versus 93 minutes (Meerwaldt 2008). In contrast, two other trials found vein patching was associated with (non‐significantly) longer operation times than either PTFE or Dacron: mean times were 126 minutes versus 123 minutes (AbuRahma 1996) and 105 minutes versus 103 minutes (Hayes 2001). In the first two cases this difference was due to longer haemostasis times with PTFE. However, the difference in the second pair of trials was explained by the longer time required to harvest vein from the groin or neck. The trial that was excluded because of the lack of clinical data (Carney 1987) also reported that the time from release of the clamps to the end of the operation was significantly longer with PTFE patches (53 minutes) compared with both vein patching (41 minutes) or Dacron patching (45 minutes) because of excessive bleeding. The trials comparing Dacron with PTFE found a non‐significantly higher operation time, but significantly higher haemostasis time (P < 0.001) in patients patched with PTFE than Dacron (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007). Five trials did not give adequate data on operation time (Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002; O'Hara 2002).

Outcomes within 30 days of operation

Clinical outcomes

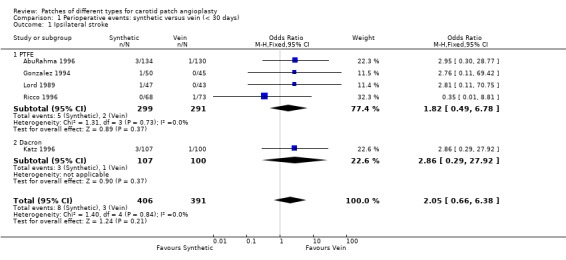

Vein versus synthetic material

No significant differences were seen in the rates of ipsilateral stroke (Analysis 1.1), any stroke (Analysis 1.2), death (Analysis 1.3) or combined stroke and death (Analysis 1.5) between the different patch types. However, the absolute risks of perioperative stroke (1.8%, 25/1122), death (1.0%, 14/1122) and combined stroke and death (2.4%, 27/1122) were all very low. All of the strokes were ipsilateral, but in two trials other types of stroke were not recorded. The functional outcome of stroke was not assessed in any of the trials. The small number of events make it unlikely that any differences between PTFE patching and vein patching would have been detected even if present.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 1 Ipsilateral stroke.

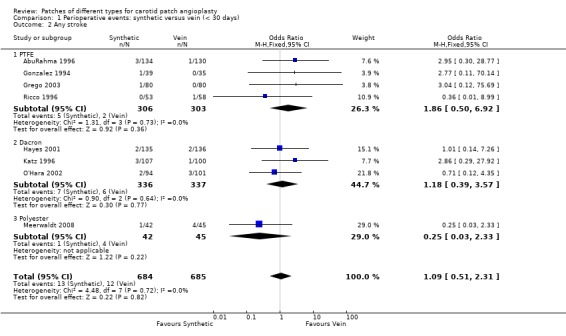

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 2 Any stroke.

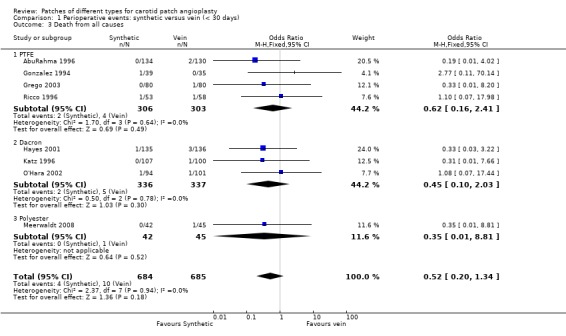

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 3 Death from all causes.

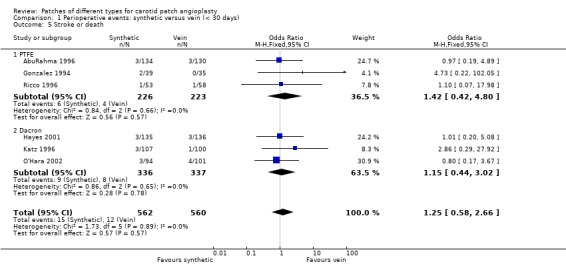

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 5 Stroke or death.

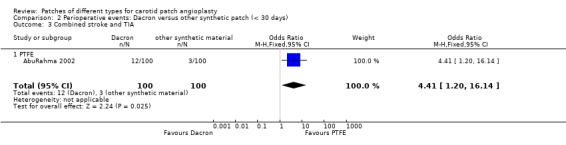

Dacron versus other synthetic material

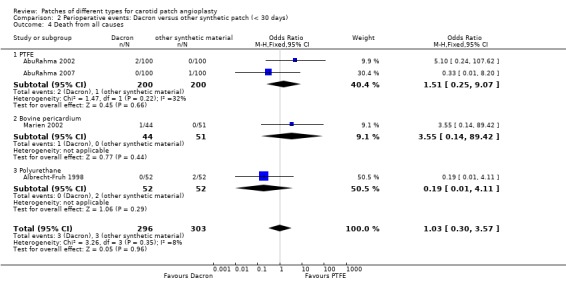

Eight strokes occurred in the Dacron group compared with one in the other synthetic group (P = 0.07) (Analysis 2.2). There was also a significantly increased risk of perioperative combined stroke and transient ischaemic attack (P = 0.03) with Dacron compared with PTFE (Analysis 2.3). There were three deaths in the Dacron‐patched group and one in the other synthetic group (P = 1.0).

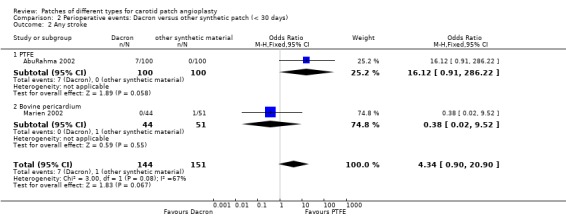

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 2 Any stroke.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 3 Combined stroke and TIA.

Arterial complications

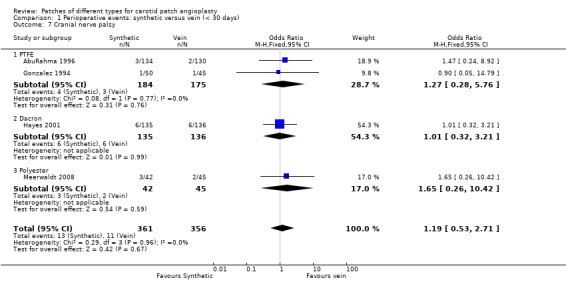

Cranial nerve injury

Vein versus synthetic material

Cranial nerve palsy occurred in 3% of cases (19/630). There was no suggestion that it was more common in either group and the confidence intervals were wide.

Dacron versus PTFE

No cranial nerve palsies were reported.

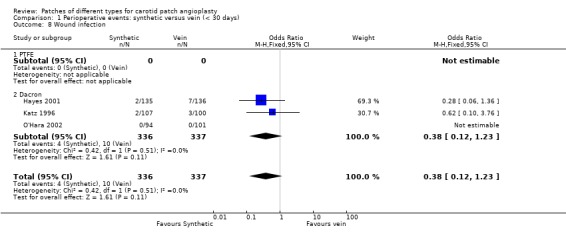

Wound infection

Vein versus synthetic material

Wound infection was non‐significantly more common in the vein group compared to the synthetic patch group (Analysis 1.8). This was due to the increased risk of groin wound infection, of which patients undergoing synthetic patching would not be at risk. However, there were no patch infections during the perioperative period.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 8 Wound infection.

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

No wound infections were reported.

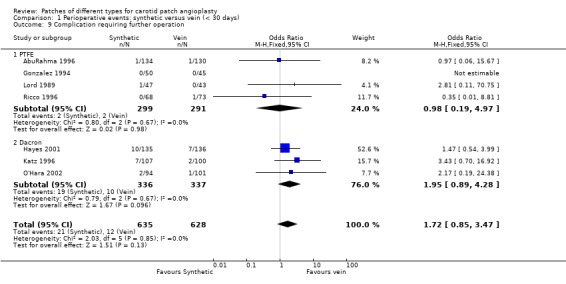

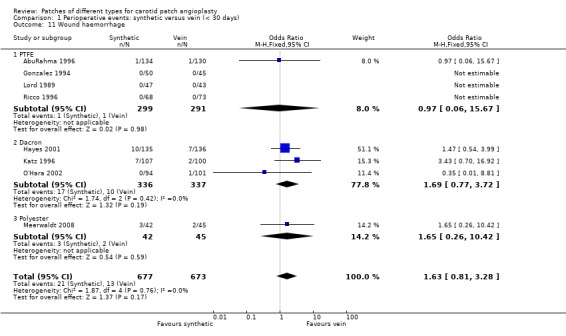

Reoperation

Vein versus synthetic material

Reoperation for any reason occurred in 2.6% (33/1263) of cases and showed a non‐significant trend towards being more common in the synthetic patch group (OR 1.72, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.47, P = 0.13) (Analysis 1.9). Reoperations were for either patch rupture (one in the PTFE group, and two in the vein group) or wound haemorrhage (2.44%, 33/1350). One of the vein ruptures involved saphenous vein harvested from the groin and one from the ankle (Analysis 1.11). Two of the three patch ruptures were fatal, one in each group. There was a non‐significant tendency for wound haematoma to be more common in the synthetic group (OR 1.63, 95% CI 0.81 to 3.28, P = 0.2).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 9 Complication requiring further operation.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 11 Wound haemorrhage.

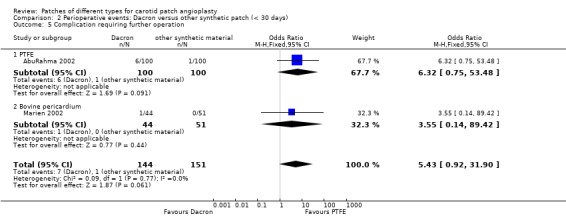

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

Eight patients required reoperation, seven in the Dacron group and one in the other synthetic patch (PTFE group) (P = 0.06). All re‐explorations were for suspected or proven carotid thrombosis/occlusion in seven cases and one case was due to wound haematoma (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 5 Complication requiring further operation.

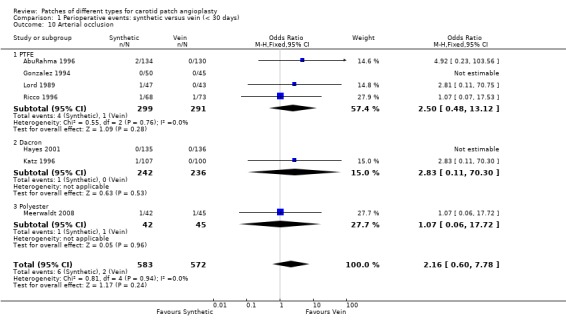

Arterial occlusion

Vein versus synthetic material

The absolute risk of arterial occlusion was 0.7% (8/1155). There was a non‐significant trend to suggest that acute occlusion is more common in arteries patched with synthetic material (OR 2.16, 95% CI 0.60 to 7.78, P = 0.2) (Analysis 1.10). Five of seven studies reporting rates of arterial occlusion did so based upon perioperative duplex ultrasound whereas two reported only symptomatic occlusions.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 10 Arterial occlusion.

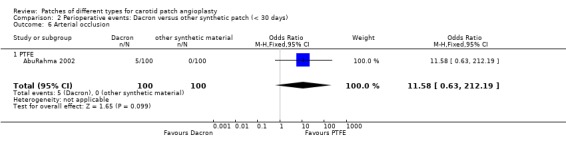

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

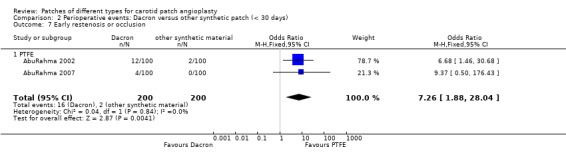

A significant risk of restenosis or occlusion at 30 days (P = 0.01) and a non‐significant increased risk of perioperative carotid thrombosis (P = 0.1) was found with Dacron compared with PTFE (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 6 Arterial occlusion.

Outcomes during long‐term follow‐up (at least one year) including events during the first 30 days

Three trials did not follow up patients for at least one year (Katz 1996; Lord 1989; Marien 2002) and these have been excluded from these analyses.

Clinical outcomes

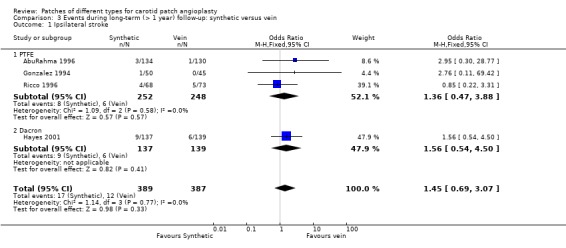

Ipsilateral stroke

Vein versus synthetic material

There was no significant difference in the ipsilateral stroke rate between vein and other synthetic material. The overall risk of ipsilateral stroke was 3.7% (29/776) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 1 Ipsilateral stroke.

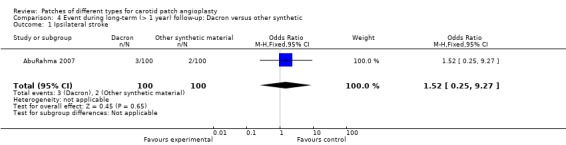

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

There was only one trial in this comparison, which showed no significant difference between two groups in terms of the ipsilateral stroke rate (Analysis 4.1) The overall risk of ipsilateral stroke was 2.5% (5/200).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 1 Ipsilateral stroke.

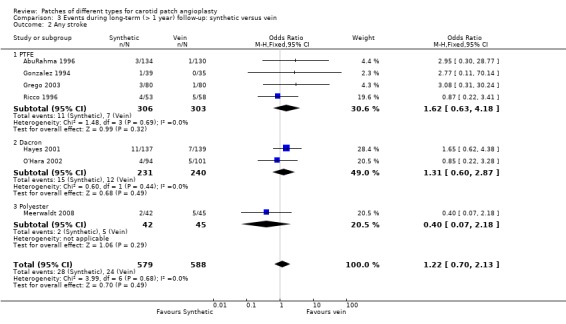

Stroke

Vein versus synthetic material

There were 52 recorded strokes of any type during follow‐up (overall risk 4.5%). There was no significant difference between synthetic patching and vein patching and the confidence intervals were wide (OR 1.22, 95% CI 0.70 to 2.13) (Analysis 3.2). The functional outcome of stroke was not assessed in any of the trials reporting long‐term outcomes.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 2 Any stroke.

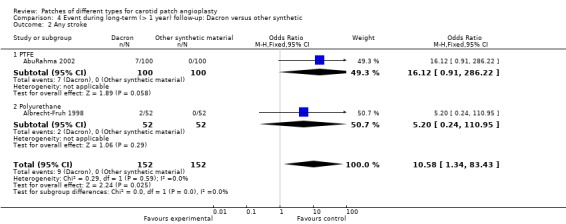

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

A significantly higher risk of stroke at long‐term follow‐up was found with Dacron compared with PTFE and polyurethane patching (OR 10.58, 95% CI 1.34 to 83.43) (Analysis 4.2). The 95% CI was very wide.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 2 Any stroke.

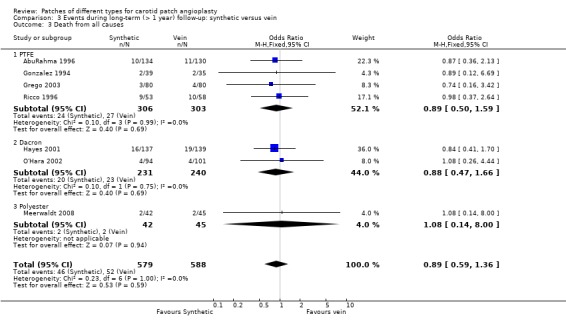

Death from all causes

Vein versus synthetic material

There was no significant difference in case fatality between the two groups (overall risk 8.4%) but the data were insufficient to give precise results (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.36) (Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 3 Death from all causes.

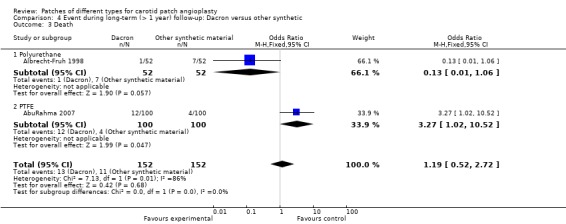

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

There were only two trials that reported this outcome, with no significant difference in death rate between Dacron and other synthetic material (Analysis 4.3). The overall risk of death was 3.7% (29/776).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 3 Death.

Any stroke or death

Vein versus synthetic material

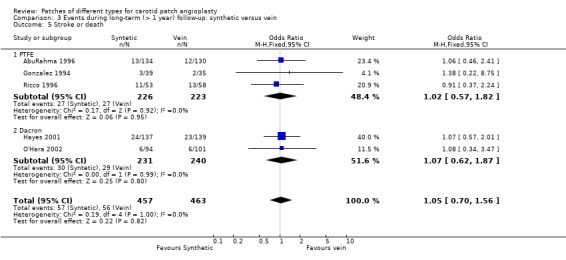

The risk of stroke or death in the PTFE group (10.31%, 57/457) was similar to that in the vein patch group (10.19%, 56/463) but again the confidence interval was wide due to the limited data available (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.56) (Analysis 3.5).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 5 Stroke or death.

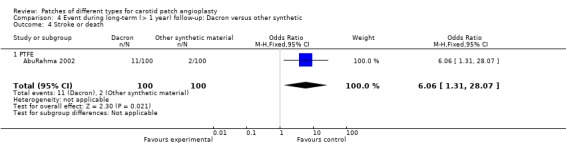

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

Only one study reported this outcome, showing a significant trend towards a lower stroke or death rate with PTFE than with Dacron (Analysis 4.4) The overall risk of ipsilateral stroke is 6.5% (13/200).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic, Outcome 4 Stroke or death.

Arterial complications

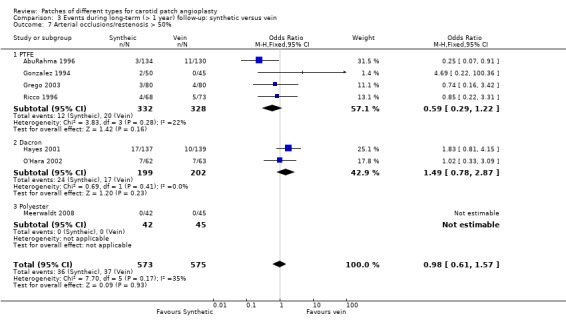

Occlusion or restenosis greater than 50%

Vein versus synthetic material

Only 73 arteries (6.4%) became restenosed or occluded during follow‐up so that it remains unclear whether PTFE patching reduces this risk or not. No trend favouring either vein or synthetic material was present (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.57) (Analysis 3.7).

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 7 Arterial occlusions/restenosis > 50%.

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

Compared with Dacron patching, there was a significantly lower risk of restenosis with other synthetic materials (especially with PTFE) (OR 8.25, 95% CI 3.03 to 22.49) (Analysis 4.5).

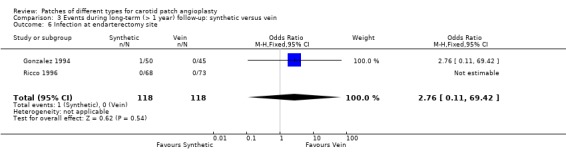

Infection

Vein versus synthetic material

One artery with a PTFE patch developed an infected false aneurysm at seven months which was successfully excised. There were no other late graft infections (Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 6 Infection at endarterectomy site.

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

There was no trial of this comparison.

Pseudoaneurysm formation

Vein versus synthetic material

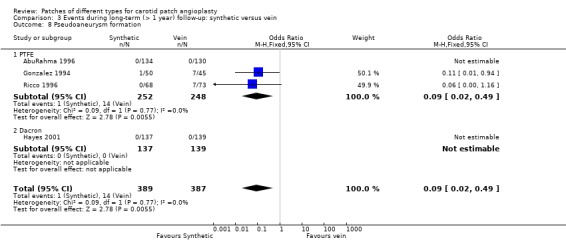

These data were available from four trials (AbuRahma 1996; Gonzalez 1994; Hayes 2001; Ricco 1996), but no trial provided an adequate definition of a pseudoaneurysm. Two trials (Gonzalez 1994; Ricco 1996) showed significant reductions in the risk of pseudoaneurysm with PTFE patching (0.8%) compared with vein patching (11.9%) (OR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.49) (Analysis 3.8) and two trials did not report any pseudoaneurysms in either group (AbuRahma 1996; Hayes 2001). Moreover, the clinical significance of the reduced risk with PTFE patching was unclear. None of the pseudoaneurysms ruptured or were associated with ipsilateral strokes, and in one trial all dilatations appeared within one month of surgery and none were progressive (Gonzalez 1994).

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 8 Pseudoaneurysm formation.

Dacron versus other synthetic patch

There were no trial data for this comparison.

Discussion

The results of this systematic review in 2002 were inconclusive because very few patients had been included in randomised comparisons of different types of patch. Despite having increased the number of patients in this current analysis there were still insufficient data to allow us to draw useful conclusions. There are no obvious differences in the risks of stroke or death suffered by patients receiving synthetic or venous patches (either perioperatively or during long‐term follow‐up), or to support the belief that synthetic patching is associated with a lower risk of patch rupture. The risk of major arterial complications such as rupture or infection was very low (less than 1%) in both groups. Any trials designed to reliably detect a reduction in the risk of rupture with synthetic patching would, therefore, need to be enormous, and even if the risks of rupture were less with synthetic patching the absolute benefits would be small. For example, assuming a baseline risk of rupture of 0.6%, over 10,000 arteries would be needed to have an 80% chance of detecting a 50% reduction in the relative risk of rupture, and this would still only prevent one rupture for every 350 operations. Pseudoaneuryms were less common in the PTFE group but these data may not be accurate because they were based on so few patients. Furthermore, the definition of pseudoaneurysm may not have been consistent between trials, and the clinical implications are unclear since there were no complications associated with pseudoaneurysm formation. It has been suggested previously that reversal of perioperative anticoagulation may reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding but may also be associated with an increased risk of perioperative stroke. The inconsistency in rates of anticoagulation reversal between the included studies may, therefore, confound interpretation of the results.

There is increasing evidence to support the use of routine or selective patching over primary closure during carotid endarterectomy (Counsell 1998). However, this review has shown that there is little reliable evidence to guide surgeons on which patch material to use. Synthetic patches do offer the advantage of sparing the morbidity and time associated with vein harvesting (e.g. poor wound healing and pain) and ensures the vein is available for future coronary bypass grafting if required. However, the use of PTFE in patching may increase the operation time (by several minutes) mainly due to increased bleeding through the suture holes. This may be less of a problem with Dacron patching (Carney 1987). In addition, the trial by Carney and Lilly suggested that surgeons preferred the handling qualities of Dacron or vein to PTFE which they found less compliant (Carney 1987). Dacron may, therefore, be preferable to PTFE, although some people believe it carries a greater risk of thrombosis (Lord 1989) and may be more prone to infection (Schmitt 1986). Furthermore, the only good quality randomised trials that have compared the use of Dacron and other synthetic material in carotid endarterectomy (AbuRahma 2002; AbuRahma 2007) found a significant benefit of PTFE over Hemoshield Dacron graft in terms of 30‐day stroke rate and postoperative restenosis of greater than 50%. However, they also noted a longer haemostasis time associated with PTFE.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review do not support the use of vein over synthetic patch material in carotid endarterectomy. The decision of which type of patch to use, if any, remains a matter of individual preference. However, if synthetic material is used, the currently available (limited) evidence from small trials appears to suggest a better outcome with PTFE than Dacron material.

Implications for research.

Further trials comparing one type of patch with another are required, but they will need large numbers of patients. More trials are required which compare different types of synthetic graft material.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2009 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Change of authorship. |

| 17 September 2009 | New search has been performed | Difference between this review and the previous version: two new trials (Grego 2003; Meerwaldt 2008) comparing synthetic with venous patching, and another three trials comparing Dacron and other synthetic material (AbuRahma 2007; Albrecht‐Fruh 1998; Marien 2002) have been added to the review. These provided more data on the long‐term outcome between Dacron and other synthetic material. The review now has 13 included studies with data for 2083 operations. The conclusions are similar to the previous version of this review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1996 Review first published: Issue 3, 1996

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 28 February 2003 | New search has been performed | Differences between this review and the previous version: four new trials (AbuRahma 1996; Hayes 2001; Katz 1996; O'Hara 2002) comparing synthetic with venous patching have recently been added to the review. Data on a total of 1280 operations are now available for analysis. A further trial 'Jugular vein versus PTFE patch for carotid endarterectomy' by Deriu and Grego is due to be reported in the next year and has been added to the 'Awaiting assessment' section and will be included in the review as soon as possible. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following: Hazel Fraser for searching the Cochrane Stroke Group trials register and providing regular updates of newly identified RCTs, and also Brenda Thomas for searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). We also thank the previous authors of this review, particularly Dr Rick Bond.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategies

MEDLINE 1966 to 1995: term used "carotid endarterectomy"

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1994 to 2008 and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (lines 1 to 12)

1 Endarterectomy, carotid/ 2 exp carotid arteries/su (surgery) 3 exp carotid artery diseases/su 4 exp carotid arteries/ 5 exp carotid artery diseases/ 6 carotid.tw. 7 4 or 5 or 6 8 endarterectomy/ 9 (endarterectom$ or surg$).tw. 10 8 or 9 11 7 and 10 12 1 or 2 or 3 or 11 13 randomized controlled trial.pt. 14 randomized controlled trials as topic/ 15 controlled clinical trial.pt. 16 controlled clinical trials as topic/ 17 random allocation/ 18 clinical trial.pt. 19 exp clinical trials as topic/ 20 (clin$ adj25 trial$).tw. 21 random$.tw. 22 research design/ 23 intervention studies/ 24 control$.tw. 25 patch$.tw. 26 or/13‐25 27 12 and 26 28 limit 27 to humans

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategies

EMBASE 1980 to 1995: terms used "carotid endarterectomy" and "carotid surgery"

EMBASE (Ovid) 1994 to 2008

1 carotid endarterectomy/ 2 carotid artery surgery/ 3 exp carotid artery disease/su 4 exp carotid artery/ 5 exp carotid artery disease/ 6 4 or 5 7 artery surgery/ or endarterectomy/ or vascular surgery/ or surgery/ 8 6 and 7 9 (carotid adj5 (endarterect$ or surgery)).tw. 10 1 or 2 or 3 or 8 or 9 11 Clinical trial/ 12 randomized controlled trial/ 13 controlled study/ 14 randomization/ 15 random$.tw. 16 Prospective study/ 17 "Evaluation and follow up"/ or Follow up/ 18 versus.tw. 19 prospective.tw. 20 types of study/ 21 methodology/ 22 comparative study/ 23 ((intervention or experiment$) adj5 group$).tw. 24 Parallel design/ 25 intermethod comparison/ 26 (controls or control group$).tw. 27 (control$ adj trial$).tw. 28 patch$.tw. 29 or/11‐28 30 10 and 29 31 limit 30 to humans

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ipsilateral stroke | 5 | 797 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.05 [0.66, 6.38] |

| 1.1 PTFE | 4 | 590 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [0.49, 6.78] |

| 1.2 Dacron | 1 | 207 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.86 [0.29, 27.92] |

| 2 Any stroke | 8 | 1369 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.51, 2.31] |

| 2.1 PTFE | 4 | 609 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.50, 6.92] |

| 2.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.39, 3.57] |

| 2.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.03, 2.33] |

| 3 Death from all causes | 8 | 1369 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.20, 1.34] |

| 3.1 PTFE | 4 | 609 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.16, 2.41] |

| 3.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.10, 2.03] |

| 3.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.35 [0.01, 8.81] |

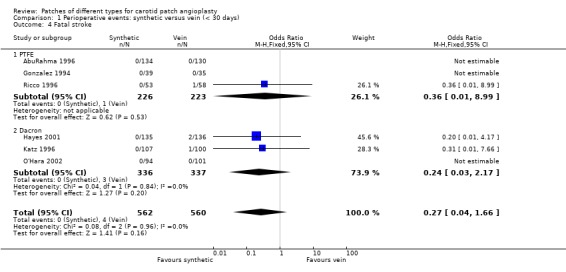

| 4 Fatal stroke | 6 | 1122 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.27 [0.04, 1.66] |

| 4.1 PTFE | 3 | 449 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.01, 8.99] |

| 4.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.24 [0.03, 2.17] |

| 5 Stroke or death | 6 | 1122 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.58, 2.66] |

| 5.1 PTFE | 3 | 449 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.42, 4.80] |

| 5.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.44, 3.02] |

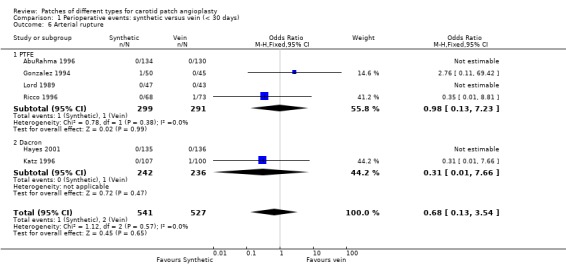

| 6 Arterial rupture | 6 | 1068 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.13, 3.54] |

| 6.1 PTFE | 4 | 590 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.13, 7.23] |

| 6.2 Dacron | 2 | 478 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.01, 7.66] |

| 7 Cranial nerve palsy | 4 | 717 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.53, 2.71] |

| 7.1 PTFE | 2 | 359 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.28, 5.76] |

| 7.2 Dacron | 1 | 271 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.32, 3.21] |

| 7.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [0.26, 10.42] |

| 8 Wound infection | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.12, 1.23] |

| 8.1 PTFE | 0 | 0 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.12, 1.23] |

| 9 Complication requiring further operation | 7 | 1263 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.72 [0.85, 3.47] |

| 9.1 PTFE | 4 | 590 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.19, 4.97] |

| 9.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.95 [0.89, 4.28] |

| 10 Arterial occlusion | 7 | 1155 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [0.60, 7.78] |

| 10.1 PTFE | 4 | 590 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.50 [0.48, 13.12] |

| 10.2 Dacron | 2 | 478 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [0.11, 70.30] |

| 10.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.06, 17.72] |

| 11 Wound haemorrhage | 8 | 1350 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [0.81, 3.28] |

| 11.1 PTFE | 4 | 590 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.06, 15.67] |

| 11.2 Dacron | 3 | 673 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.69 [0.77, 3.72] |

| 11.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [0.26, 10.42] |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 4 Fatal stroke.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 6 Arterial rupture.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Perioperative events: synthetic versus vein (< 30 days), Outcome 7 Cranial nerve palsy.

Comparison 2. Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ipsilateral Stroke | 2 | 400 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.89 [0.96, 15.73] |

| 1.1 PTFE | 2 | 400 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.89 [0.96, 15.73] |

| 2 Any stroke | 2 | 295 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.34 [0.90, 20.90] |

| 2.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.12 [0.91, 286.22] |

| 2.2 Bovine pericardium | 1 | 95 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.02, 9.52] |

| 3 Combined stroke and TIA | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.41 [1.20, 16.14] |

| 3.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.41 [1.20, 16.14] |

| 4 Death from all causes | 4 | 599 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.30, 3.57] |

| 4.1 PTFE | 2 | 400 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.25, 9.07] |

| 4.2 Bovine pericardium | 1 | 95 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.55 [0.14, 89.42] |

| 4.3 Polyurethane | 1 | 104 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.01, 4.11] |

| 5 Complication requiring further operation | 2 | 295 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.43 [0.92, 31.90] |

| 5.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.32 [0.75, 53.48] |

| 5.2 Bovine pericardium | 1 | 95 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.55 [0.14, 89.42] |

| 6 Arterial occlusion | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.58 [0.63, 212.19] |

| 6.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 11.58 [0.63, 212.19] |

| 7 Early restenosis or occlusion | 2 | 400 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.26 [1.88, 28.04] |

| 7.1 PTFE | 2 | 400 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.26 [1.88, 28.04] |

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 4 Death from all causes.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Perioperative events: Dacron versus other synthetic patch (< 30 days), Outcome 7 Early restenosis or occlusion.

Comparison 3. Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ipsilateral stroke | 4 | 776 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.45 [0.69, 3.07] |

| 1.1 PTFE | 3 | 500 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.47, 3.88] |

| 1.2 Dacron | 1 | 276 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.56 [0.54, 4.50] |

| 2 Any stroke | 7 | 1167 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.70, 2.13] |

| 2.1 PTFE | 4 | 609 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.62 [0.63, 4.18] |

| 2.2 Dacron | 2 | 471 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [0.60, 2.87] |

| 2.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.4 [0.07, 2.18] |

| 3 Death from all causes | 7 | 1167 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.59, 1.36] |

| 3.1 PTFE | 4 | 609 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.50, 1.59] |

| 3.2 Dacron | 2 | 471 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.47, 1.66] |

| 3.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.14, 8.00] |

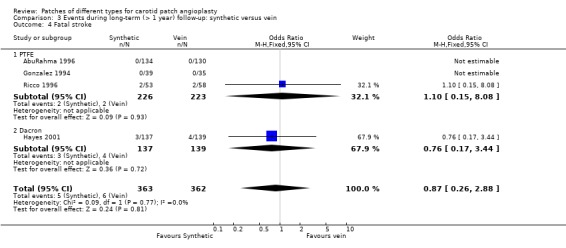

| 4 Fatal stroke | 4 | 725 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.26, 2.88] |

| 4.1 PTFE | 3 | 449 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.15, 8.08] |

| 4.2 Dacron | 1 | 276 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.17, 3.44] |

| 5 Stroke or death | 5 | 920 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.70, 1.56] |

| 5.1 PTFE | 3 | 449 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.57, 1.82] |

| 5.2 Dacron | 2 | 471 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.62, 1.87] |

| 6 Infection at endarterectomy site | 2 | 236 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.76 [0.11, 69.42] |

| 7 Arterial occlusions/restenosis > 50% | 7 | 1148 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.61, 1.57] |

| 7.1 PTFE | 4 | 660 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.29, 1.22] |

| 7.2 Dacron | 2 | 401 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.49 [0.78, 2.87] |

| 7.3 Polyester | 1 | 87 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Pseudoaneurysm formation | 4 | 776 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.02, 0.49] |

| 8.1 PTFE | 3 | 500 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.09 [0.02, 0.49] |

| 8.2 Dacron | 1 | 276 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Events during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: synthetic versus vein, Outcome 4 Fatal stroke.

Comparison 4. Event during long‐term (> 1 year) follow‐up: Dacron versus other synthetic.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ipsilateral stroke | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.25, 9.27] |

| 2 Any stroke | 2 | 304 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.58 [1.34, 83.43] |

| 2.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 16.12 [0.91, 286.22] |

| 2.2 Polyurethane | 1 | 104 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.20 [0.24, 110.95] |

| 3 Death | 2 | 304 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.52, 2.72] |

| 3.1 Polyurethane | 1 | 104 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.01, 1.06] |

| 3.2 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.27 [1.02, 10.52] |

| 4 Stroke or death | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.06 [1.31, 28.07] |

| 4.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.06 [1.31, 28.07] |

| 5 Arterial occlusion/restenosis > 50% | 2 | 304 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.25 [3.03, 22.49] |

| 5.1 PTFE | 1 | 200 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 13.86 [4.07, 47.22] |

| 5.2 Polyurethane | 1 | 104 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.21] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

AbuRahma 1996.

| Methods | R: computer‐generated sealed envelopes (artery randomised) Both duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: 4 patients in vein group underwent primary closure and were excluded from the trial, 3 jugular vein patients had saphenous vein and were included in trial | |

| Participants | USA 357 patients, 399 operations in three arms: 130 vein, 134 PTFE and 135 primary closure 50% male Mean age 68 years 33% asymptomatic Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: alternating saphenous vein patch (from ankle) and jugular vein Routine shunting for all and GA 325 mg daily aspirin was started within 24 hours of surgery for all patients | |

| Outcomes | Death, ipsilateral stroke, ipsilateral TIA and ipsilateral RIND at 30 days and 48 months Duplex evidence of restenosis > 50% during FU | |

| Notes | Ex: patients with ICA < 4 mm or combined CABG or redo surgery FU: mean 30 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

AbuRahma 2002.

| Methods | R: computer‐generated sealed envelopes (artery randomised) Both duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: 4 patients in vein group underwent primary closure and were excluded from the trial, 3 jugular vein patients had saphenous vein and were included in trial | |

| Participants | USA 180 patients, 200 operations in 2 arms: 100 Dacron, 100 PTFE closure 53% male Mean age 68 years 39% asymptomatic Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: collagen‐impregnated Dacron Routine shunting for all and GA 325 mg daily aspirin was started within 24 hours of surgery for all patients | |

| Outcomes | Death, ipsilateral stroke, ipsilateral TIA and ipsilateral RIND at 30 days Duplex evidence of restenosis > 50% during follow‐up | |

| Notes | Ex: patients with ICA < 4 mm or combined CABG or redo surgery FU: mean 30 days | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

AbuRahma 2007.

| Methods | R: sealed envelopes with block of 10 randomisation Duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: no | |

| Participants | USA 200 patients, 200 operations 49.5 % male Mean age 67.9 years 45% asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch (ACUSEAL) Control: Dacron patch (Hemashield‐Fitnesse) 100% shunted Postoperative aspirin 325 mg for all | |

| Outcomes | Perioperative outcome: neurological event, ipsilateral stroke, ipsilateral TIA, mortality, restenosis, thrombosis, combined perioperative neurological event Long‐term outcome: ipsilateral stroke, all ipsilateral TIA, all TIA and strokes, all cause mortality, stroke mortality, all TIA‐stroke‐death rate, > 70% stenosis | |

| Notes | Ex: concomitant CABG or redo carotid endarterectomy FU: 30 days and long‐term outcome | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Albrecht‐Fruh 1998.

| Methods | R: unclear Both duplex and clinical FU: unclear Crossovers: no | |

| Participants | Germany 52 patients, 52 operations 67% male Mean age 67.1 years % asymptomatic carotid disease unclear but indicated that it is similar in both groups Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: Dacron patch Control: polyurethane patch % shunted: unclear Postoperative aspirin: unclear | |

| Outcomes | Perioperative outcome: bleeding time in suture hole Long‐term outcome: stroke, restenosis | |

| Notes | Ex: pregnancy, emergency operation, infection FU: 30 days and long‐term outcome (1 year) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gonzalez 1994.

| Methods | R: open random number list (artery randomised) Clinical and DSA FU blind Crossovers: none Exclusions during trial: none Patients lost to FU: none | |

| Participants | Spain 84 patients, 95 operations 88% male Mean age 69 years 28% asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: saphenous vein patch (from ankle) Routine shunting for all Peri‐ and postoperative aspirin (325 mg) for all | |

| Outcomes | Death < 30 days, at 1 year and end of FU Stroke < 30 days, at 1 year and end of FU Perioperative occlusion (intravenous DSA) Perioperative wound haemorrhage, infection, cranial nerve palsy Restenosis > 50% or occlusion at 1 year and end of FU (intravenous DSA) | |

| Notes | Ex: none FU: mean 29 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Grego 2003.

| Methods | R: sealed envelopes with block randomisation Both duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: no | |

| Participants | Italy 80 patients, 80 operations 61.9% male Mean age 70.25 years 30.6 % asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group except sex | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: external jugular vein patch 100 % shunted Postoperative: day 3 start aspirin, 100 mg for all | |

| Outcomes | Perioperative outcome: blood loss, time to haemostasis, relevant neurological complication, TIA, mortality Long‐term outcome: relevant neurological complication, stroke, mortality | |

| Notes | Ex: combined cardiac surgery, surgery to treat recurrent restenosis, lack of external jugular vein FU: perioperative outcome and long‐term (at least 3 years) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hayes 2001.

| Methods | R: computer‐generated sealed envelopes Both duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: 3 patients randomised to vein had Dacron due to lack of vein, 6 patients had a different operation than CEA (artery randomised) | |

| Participants | UK 274 patients, 276 operations. 67% male Mean age 70 years 11% asymptomatic Comparability: sex, age, vascular risk factors and % symptomatic disease was similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: knitted Dacron graft Control: saphenous vein harvested from groin Postoperative dextran given selectively according to Doppler‐detected emboli Anaesthesia and shunt use not specified | |

| Outcomes | Death, disabling stroke, non‐disabling stroke and cranial nerve injury and duplex evidence of restenosis at 30 days and 3 years | |

| Notes | Ex: 20 patients excluded prior to randomisation, 10 refusal, 6 no vein, 4 other FU: 30 days and 3 years 2 patients refused long‐term duplex follow‐up | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Katz 1996.

| Methods | R: uncertain technique Artery randomised | |

| Participants | USA 190 patients, 207 operations 49% male Mean age 71 years 47% asymptomatic Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors | |

| Interventions | Rx: knitted Dacron graft Control: saphenous vein harvested from groin Heparin reversed in most of Dacron patients but none of vein patients All GA Dextran given perioperatively All patients shunted | |

| Outcomes | Death or Ipsilateral stroke < 30 days Perioperative wound haemorrhage or infection | |

| Notes | Ex: 17 patients: 7 refusal, 6 absent vein graft, 4 combined CABG FU: 30 days only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lord 1989.

| Methods | R: sealed envelopes (artery randomised) Probably neither duplex nor clinical FU blind Crossovers: 4 but not known from which group Exclusions during trial: 4 crossovers Patients lost to FU: none | |

| Participants | Australia Number of patients unknown, 90 operations 62% male Mean age 63 years % asymptomatic carotid disease unknown Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % symptomatic disease similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: saphenous vein patch (from groin) 17% shunted Postoperative aspirin for all | |

| Outcomes | Ipsilateral stroke < 30 days Perioperative occlusion (intravenous DSA) Perioperative wound haemorrhage | |

| Notes | Ex: unknown FU: until hospital discharge | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Marien 2002.

| Methods | R: based on the last number of patient's medical record: odd number used bovine pericardium and even number used Dacron patches Blinded duplex and clinical FU: unclear Concealment: no Crossovers: none | |

| Participants | USA 92 patients, 95 operations 61% male Mean age 65.9 years 46.3% asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease similar in each group, but % stroke is higher in bovine patch pericardium | |

| Interventions | Rx: bovine pericardium patch Control: Dacron patch 100 % shunted Postoperative for all patients: continue antiplatelet | |

| Outcomes | Perioperative outcome: suture line blood loss, neck haematoma, TIA, stroke, death | |

| Notes | Ex: concomitant CABG and recurrent carotid stenosis FU: perioperative | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Meerwaldt 2008.

| Methods | R: sealed envelopes Both duplex and clinical FU blinded Crossovers: none Lost to FU: none | |

| Participants | The Netherlands 87 patients, 87 operations 79.3% male Mean age 66.5 years 0% asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors similar in each group except the percentage of regressive stroke, non‐regressive stroke and bilateral carotid stenosis is higher in bovine pericardium group | |

| Interventions | Rx: polyester patch (Fluoropassiv) Control: vein patch (ankle vein) 9.2 % shunted Postoperative for all patients: continued Dipyridamol 150 mg | |

| Outcomes | Perioperative period: death, TIA, regressive stroke, asymptomatic recurrent stenosis/acute thrombosis, local wound complication (e.g. nerve damage, infection, pain) At 6 weeks and 2 years: death, stroke, restenosis, acute thrombosis | |

| Notes | Ex: known allergies to patch product, previous ipsilateral carotid surgery, bilateral carotid endarterectomy, progressive neurological events one month prior to surgery (crescendo TIA) and hospitalisation for heart failure in previous 6 months FU: perioperative, 6 weeks and 2 years | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

O'Hara 2002.

| Methods | R: computer‐generated sealed envelopes (artery randomised) Probably neither duplex nor clinical FU blinded Crossovers: ? none Exclusions during trial: 9 patients did not undergo allocated treatment Patients lost to FU: none | |

| Participants | USA 195 patients, 207 operations 74% male Mean age 69 years 58% asymptomatic Comparability: other than a higher incidence of males in the synthetic patch groups, age, vascular risk factors and % symptomatic disease was similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: knitted Dacron graft Control: saphenous vein harvest site not specified Anaesthesia and shunt use not specified | |

| Outcomes | Death or any stroke < 30 days Reoperation Any hospital complication Recurrent stenosis on follow‐up | |

| Notes | Ex: ? number excluded prior to randomisation 9 patients allocated to surgery failed to undergo it FU: 30 days and median long‐term duplex FU at 18 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ricco 1996.

| Methods | R: opaque, sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes (artery randomised) Follow‐up blinding attempted Crossovers: none Exclusions during trial: none Patients lost to FU: 3 PTFE, 4 vein patch | |

| Participants | France 124 patients, 141 operations 80% male Mean age 63.5 years 33% asymptomatic carotid disease Comparability: age, sex, vascular risk factors, % asymptomatic disease were similar in each group | |

| Interventions | Rx: PTFE patch Control: saphenous vein patch (90% from groin) 83% shunted Postoperative aspirin (250 mg) for all | |

| Outcomes | Death < 30 days, 1 year and end of FU Ipsilateral stroke < 30 days, 1 year and end of FU Perioperative occlusion (Duplex) Perioperative wound haemorrhage Restenosis > 50% or occlusion at 1 year and end of FU (Duplex) | |

| Notes | Ex: external artery diameter > 5 mm and internal diameter > 3.5 mm, recurrent stenosis FU: mean 53 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

CABG: carotid artery bypass graft CEA: carotid endarterectomy DSA: digital subtraction angiography Ex: exclusion criteria FU: follow‐up GA: general anaesthesia ICA: internal carotid artery PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene R: concealment of allocation RIND: reversible ischaemic neurological deficit Rx: treatment TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Carney 1987 | No clinical outcomes recorded (e.g. deaths, strokes, arterial complications) 74 patients randomised between Dacron, PTFE and venous patch Randomisation by open random number list |

| Chyatte 1996 | No clinical outcomes recorded (e.g. deaths, strokes, arterial complications) but was looking at microemboli perioperatively |

| Ruckert 2000 | No clinical outcomes recorded (e.g. deaths, strokes, arterial complications) but was looking at bleeding time, microemboli perioperatively Although there is a restenosis result, paper did not report whether that was the perioperative or long‐term outcome |

PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene

Contributions of authors

Kittipan Rerkasem: refined the protocol, performed searches, selected studies for inclusion, extracted and entered the date, and wrote the review. Peter Rothwell: refined the protocol, performed searches, selected studies, co‐ordinated the project, commented on the design of the protocol and on the final manuscript.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxford University Medical Research Fund (MRF), UK.

External sources

NHS Executive Research and Development Directorate, UK.

Medical Research Council, UK.

Northern Neurological Center, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, Thailand.

Division of Vascular Surgery Unit, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Thailand, Thailand.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

AbuRahma 1996 {published data only}

- AbuRahma AF, Khan JH, Robinson PA, Saiedy S, Short YS, Boland JP, et al. Prospective randomized trial of carotid endarterectomy with primary closure and patch angioplasty with saphenous vein, jugular vein, and polytetrafluoroethylene: perioperative (30 day) results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1996;24:998‐1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuRahma AF, Robinson PA, Saiedy S, Kahn JH, Boland JP. Prospective randomized trial of carotid endarterectomy with primary closure and patch angioplasty with saphenous vein, jugular vein, and polytetrafluoroethylene: long‐term follow‐up. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1998;27(2):222‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AbuRahma 2002 {published data only}

- AbuRahma A, Hannay S, Khan JH, Robinson PA, Hudson JK, Davis EA. Prospective randomised study of carotid endarterectomy with polytetrafluoroethylene versus collagen‐impregnated Dacron (Hemashield) patching: perioperative (30‐day) results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2002;35:125‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuRahma AF, Hopkins ES, Robinson PA, Deel JT, Agarwal S. Prospective randomized trial of carotid endarterectomy with polytetrafluoroethylene versus collagen‐impregnated Dacron (Hemashield) patching: late follow‐up. Annals of Surgery 2003;237:885‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AbuRahma 2007 {published data only}

- AbuRahma AF, Stone PA, Flaherty SK, AbuRahma Z. Prospective randomized trial of ACUSEAL (Gore‐Tex) versus Hemashield‐Finesse patching during carotid endarterectomy: early results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2007;45:881‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburahma AF, Stone PA, Elmore M, Flaherty SK, Armistead L, AbuRahma Z. Prospective randomized trial of ACUSEAL (Gore‐Tex) vs Finesse (Hemashield) patching during carotid endarterectomy: long‐term outcome. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2008;48(1):99‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Albrecht‐Fruh 1998 {published data only}

- Albrecht‐Fruh G, Ktenidis K, Horsch S. Dacron versus polyurethane (PUR) patch angioplasty in carotid surgery. In: Horsch S, Ktenidis K editor(s). Perioperative Monitoring in Carotid Surgery. Darmstadt Steinkopff Springer, 1998:153‐7. [Google Scholar]

Gonzalez 1994 {published and unpublished data}

- Gonzalez‐Fajardo JA, Perez JL, Mateo AM. Saphenous vein patch versus polytetrafluoroethylene patch after carotid endarterectomy. Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 1994;35:523‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez‐Burckhardt JL, Gonzalez‐Fajardo JA, Mateo AH. Saphenous vein patch versus polytetrafluoroethylene patch after carotid endarterectomy. International Angiology 1995;14 Suppl 1:346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grego 2003 {published data only}

- Grego F, Antonello M, Lepidi S, Bonvini S, Deriu GP. Prospective, randomized study of external jugular vein patch versus polytetrafluoroethylene patch during carotid endarterectomy: perioperative and long‐term results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2003;38:1232‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hayes 2001 {published data only}

- Hayes PD, Allroggen H, Steel S, Thompson MM, London NJ, Bell PR, et al. Randomized trial of vein versus Dacron patching during carotid endarterectomy: influence of patch type on postoperative embolization. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2001;33(5):994‐1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor R, Hayes PD, Payne DA, Allroggen H, Steel S, Thompson MM, et al. Randomized trial of vein versus Dacron patching during carotid endarterectomy: long‐term results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2004;39(5):985‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Katz 1996 {published data only}

- Katz SG, Kohl RD. Does the choice of material influence early morbidity in patients undergoing carotid patch angioplasty?. Surgery 1996;119:297‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lord 1989 {published and unpublished data}

- Lord RSA, Raj TB, Stary DL, Nash PA, Graham AR, Goh KH. Comparison of saphenous vein patch, polytetrafluoroethylene patch, and direct arteriotomy closure after carotid endarterectomy. Part I: Perioperative results. Journal of Vascular Surgery 1989;9:521‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marien 2002 {published data only}

- Marien BJ, Raffetto JD, Seidman CS, LaMorte WW, Menzoian JO. Bovine pericardium vs Dacron for patch angioplasty after carotid endarterectomy. A prospective randomized study. Archives of Surgery 2002;137:785‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meerwaldt 2008 {published data only}

- Meerwaldt R, Lansink KW, Blomme AM, Fritschy WM. Prospective randomized study of carotid endarterectomy with Fluoropassiv thin wall carotid patch versus venous patch. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2008;36:45‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Hara 2002 {published data only}

- O'Hara PJ, Hertzer NR, Mascha EJ, Krajewski LP, Clair D G, Ouriel K. A prospective, randomized study of saphenous vein patching versus synthetic patching during carotid endarterectomy. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2002;35(2):324‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ricco 1996 {published and unpublished data}

- Ricco J‐B, Demarque C, Bouin‐Pineau M‐H, Camiade C. Vein patch versus PTFE patch for carotid endarterectomy. A randomized trial in a selected group of patients. Manuscript submitted to the European Journal of Vascular Surgery 1996.

- Ricco JB, Gauthier J‐B, Bodin‐Pineau M‐H. Enlargement patch after carotid endarterectomy. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or saphenous patch? Results of a randomized study after 3 years (abstract). Paper presented at The French Language Society of Vascular Surgery, Annual Congress of Reims. 19‐20 June 1992.

References to studies excluded from this review

Carney 1987 {published data only}

- Carney WI, Lilly MP. Intraoperative evaluation of PTFE, Dacron and autologous vein as carotid patch materials. Annals of Vascular Surgery 1987;1:583‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chyatte 1996 {published data only (unpublished sought but not used)}

- Chyatte D. Perioperative microemboli during carotid endarterectomy: differences between synthetic and saphenous vein patches. Cerebrovascular Diseases 1996;6 Suppl 2:2 (Abstract 17). [Google Scholar]

Ruckert 2000 {published data only}

- Ruckert RI, Obitz JG, Schwenk W, Walter M. Prospective randomized comparison of different patch materials in carotid surgery. Acta Chirurgica Austriaca 2000;32:19. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

ACAS 1995

- Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995;273(18):1421‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

APT 1994

- Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration. Collaborative overview of trials of antiplatelet therapy ‐ I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81‐106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Counsell 1998

- Counsell C, Salinas R, Warlow C, Naylor R. Patch angioplasty compared to primary closure in carotid endarterectomy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998, Issue 1. [Art. No.: CD000160. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000160] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ECST 1991

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists' Collaborative Group. MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial: interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70‐99%) or with mild (0‐29%) carotid stenosis. Lancet 1991;337:1235‐43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ECST 1998

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC Eurpean Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998;351:1379‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fode 1986

- Fode NC, Sundt Jr TM, Robertson JT, Peerless SJ, Shields CB. Multicenter retrospective review of results and complications of carotid endarterectomy in 1981. Stroke 1986;17:370‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim 2001

- Kim GE, Kwon TW, Cho YP, Kim DK, Kim HS. Carotid endarterectomy with bovine patch angioplasty: a preliminary report. Cardiovascular Surgery 2001;9(5):458‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murie 1994

- Murie JA, John TG, Morris PJ. Carotid endarterectomy in Great Britain and Ireland: practice between 1984 and 1992. British Journal of Surgery 1994;81:827‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NASCET 1991

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high‐grade carotid stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1991;325:445‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NASCET 1998

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339:1415‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmitt 1986