Background

Debate about appropriate gatekeeping for access to investigational drugs outside clinical trials has intensified in recent years, culminating in the enactment of the federal “Right to Try” Act in May 2018 and similar laws in 41 states.1,2 The premise of Right to Try is that regulatory bodies should not be party to doctor-patient decisions about how to respond to life-threatening disease, even when those decisions involve unapproved products.3 This contrasts with the longstanding pathway known as “Expanded Access”, which requires that pre-approval access be authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and institutional review boards.4 For both pathways, patients may access investigational drugs only if the manufacturer agrees to provide them.

Many ethicists5-9 and patient groups10 have articulated why Expanded Access is preferable to Right to Try. Expanded Access offers greater protections for individual patients without reducing or substantially slowing their access to investigational products while also offering greater benefits for patient populations by incorporating strong safety reporting and affirming the importance of FDA’s role in protecting the public’s health. In this light, the fact that only two patients have been publicly documented as securing access to investigational products under the Right to Try Act since the law’s passage (one with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis11 and one with brain cancer12) is a relief.

Yet, this does not capture how often patients may ask their physicians about Right to Try or how often physicians may raise the issue, perhaps motivated by the law’s promise of reduced administrative burden13 and liability protection. The private nature of such discussions and the fact that the federal law is relatively new have provided little opportunity for empirical examination. Nevertheless, some manufacturers have stated that they will facilitate access through Right to Try,14,14a a new contract research organization plans to work with manufacturers to collect observational data from Right to Try uses,15,15a and President Trump continues to tout the law as a success that has “saved many lives.”16 These developments, alongside sustained attention to pre-approval access by FDA and the media, suggest that physicians should anticipate receiving Right to Try requests and that new reports of access through this pathway may be forthcoming.

Right to Try and Oncology

Oncology likely will be at the forefront of any increase in Right to Try activity. There has been a longstanding appetite for pre-approval access to experimental cancer interventions that dates back to the 1970s, when a group of terminally ill patients with cancer unsuccessfully sued over FDA’s approach to regulating laetrile17 and the FDA and National Cancer Institute established the Group C treatment investigational new drug application, providing a means to distribute investigational agents for cancer treatment outside clinical trials.18 This robust interest continues today. Oncology products comprised 20% (1,071) of Expanded Access requests for individual patients that FDA allowed to proceed between fiscal years 2010 and 2014, second only to requests for antiviral products (23%).19

Oncology drug development is also proceeding rapidly. In 2017, more than 700 molecules were in late-stage development for cancers, 60% more than a decade ago.20 In 2018, FDA approved 52 drugs and drug combinations for new oncology indications.21 This level of activity may add to a sense that a wave of novel, better oncology drugs must be coming, fueling the belief that patients with cancer could benefit from investigational products if only they could access them immediately.

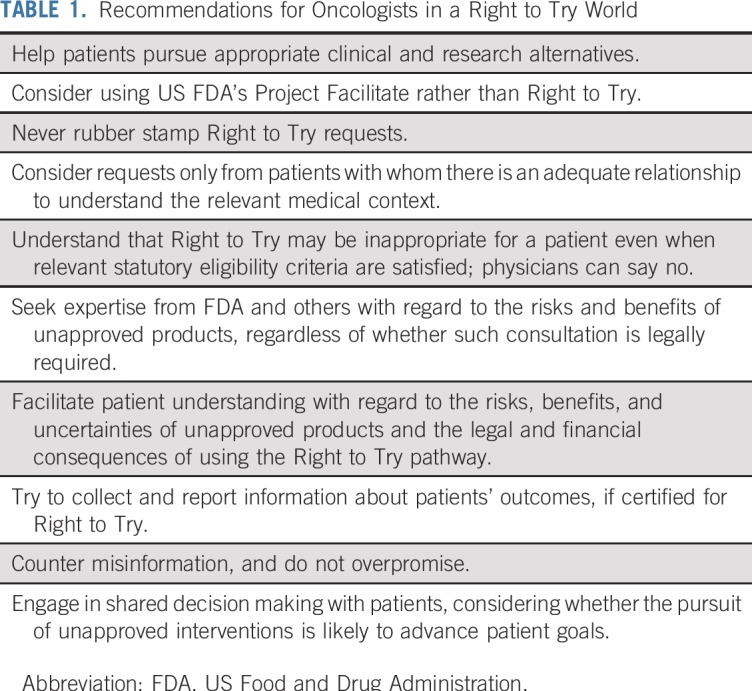

Although Right to Try is relevant to many specialties, this context suggests that it is particularly important for oncologists (and cancer centers) to consider how to respond. Some have suggested that because Expanded Access offers the same benefits as Right to Try with better patient protections, “it would be unethical for oncologists to use [Right to Try] to gain access to an experimental drug for their patients.”22 We agree that oncologists, and others, focused on patient best interests should steer patients away from Right to Try and toward Expanded Access, assuming that there is no appropriate clinical trial and that pre-approval access is itself reasonable. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that not every oncologist will feel comfortable with adopting a blanket policy of refusing Right to Try requests, especially if a manufacturer will make a product available only through this pathway. Therefore, we offer suggestions for how oncologists can satisfy their ethical and legal obligations in the context of Right to Try (Table 1) and fulfill their envisioned role under the law to safeguard seriously ill, often vulnerable patients.

TABLE 1.

Recommendations for Oncologists in a Right to Try World

Certifying Eligible Patients

To access an investigational drug under Right to Try, a patient must be diagnosed with a life-threatening condition, receive physician certification of exhaustion of approved treatment options and inability to participate in a clinical trial of the desired product, and provide informed consent.1 At a minimum, oncologists who are considering certification of patient eligibility should not make themselves available for doctor shopping or as a rubber stamp. In other contexts, such as direct-marketed genetic testing23 and online prescription companies,24 patients have been superficially connected to physicians who order tests or write prescriptions to permit product sale. Similar companies may emerge to offer the services of physicians willing to certify Right to Try eligibility for a fee. The idea of physician mercenaries is problematic because it makes a farce of the gatekeeping role that Right to Try preserves for certifying physicians. In the absence of a genuine doctor-patient relationship, or at least a comprehensive consulting relationship, a physician is unlikely to have adequate information to understand the patient’s condition and history or to confirm eligibility criteria.

Also important to understand is that the legal requirements for certifying eligibility for, and otherwise complying with, Right to Try are a floor, not a ceiling. This means that conscientious oncologists may determine that certification is inappropriate, even if the statutory criteria are met; the law explicitly precludes liability for a determination not to provide access. Oncologists should carefully assess whether a patient has tried all standard treatments, and if these have been exhausted, whether there are any options for appropriate clinical trials. To certify a patient’s eligibility, the Right to Try law requires physicians to confirm only that the patient cannot participate in a trial of the specific investigational product the patient is seeking.1 Nonetheless, if there is a trial of a different product relevant to the patient’s disease for which the patient may be eligible, oncologists should consider whether that might be preferable to Right to Try, keeping in mind both the patient’s interests and the importance of supporting rigorous data collection about investigational agents.

Right to Try does not require independent assessment of the risks and potential benefits of providing a patient with access to the investigational drug, yet this assessment is essential to patient welfare. In the spirit of shared decision making, competent adult patients’ views about which risks they are willing to accept for which benefits deserve serious consideration. But oncologists also have a professional obligation not to expose patients to unreasonable risks and to help patients to understand the relevant uncertainties and likelihood of achieving their goals. Accordingly, even where a patient has satisfied legal criteria for Right to Try, oncologists should deny certification where the risks are too great or the patient is mistaken about expected benefits. If oncologists do certify eligibility, they should consider ways to collect patient outcome data and report them to companies and FDA (although they are not legally required to do so) because this will help to inform future assessments of the drug.

Evaluation of the risks and benefits of an investigational drug can be challenging. This is largely why cutting FDA out of the Right to Try pathway is problematic: the agency has expertise and information that individual physicians may not. Although FDA authorizes more than 99% of Expanded Access requests,19 it requires changes to the dose, safety monitoring, and/or informed consent for 11% of requests.25 This suggests that even though not required, oncologists who contemplate Right to Try requests can provide the best care by seeking FDA’s input. To the extent permissible given confidentiality protections, FDA should provide such input and inform physicians about how they can seek agency feedback on Right to Try requests.

Expanded Access places some administrative burdens on physicians that Right to Try does not.8 However, FDA launched a pilot program in June 2019 called Project Facilitate to simplify Expanded Access for oncology products.26,27 This concierge program entails a single point of contact for all oncology Expanded Access requests through which expert FDA staff will guide oncologists through the process. Project Facilitate also will help FDA to collect information about patient outcomes and circumstances in which, and reasons why, manufacturers deny access requests. Given these efforts, oncologists have an even stronger reason to prefer Expanded Access over Right to Try.

Promoting Patient Understanding

Both pre-approval pathways require that physicians secure informed consent from patients. Under Expanded Access, this includes satisfying disclosure and institutional review board approval requirements applicable to research.28 By contrast, Right to Try does not specify the parameters of informed consent and no outside entity must review it, although some state laws are more explicit.

Oncologists using Right to Try should help patients understand the risks, potential benefits, and uncertainties about the investigational drug, just as they would with any approved treatment or clinical trial. This conversation is especially critical for Right to Try because unlike for approved therapies, clinical trials, and Expanded Access, there is no required independent assessment of the risks and benefits of the intervention by any expert body.22 Consistent with the focus of Right to Try on patient autonomy, then, oncologists should take steps to ensure that patients have appropriate information, understanding, and voluntariness to exercise autonomous choice. Medical licensing boards and consumer protection agencies may play a role in disciplining physicians who overpromise on safety or effectiveness of investigational products or engage in otherwise exploitative practices.29-31

Pragmatic details also exist about Right to Try that oncologists can help their patients understand. Most important is that the law does not create any right to investigational products.32,33 As with Expanded Access, manufacturers are free to deny Right to Try requests. Just as we argue that oncologists should avoid Right to Try in the interests of their patients, we suggest that manufacturers ought to do the same. Indeed, several large manufacturers have re-affirmed their commitment to using Expanded Access in collaboration with FDA if and when they provide unapproved products outside of clinical trials.34,35

Patients also should understand that no one is required to cover the costs of access through either pathway. Certain state statutes have even more stark implications, sometimes excluding Right to Try patients from insurance coverage or hospice eligibility.2 Right to Try also strips patients of their ability to hold drug manufacturers liable for damages and physicians liable absent gross misconduct.1 Although these legal constraints may have limited practical impact given the lack of publicly reported instances of patients suing for injuries resulting from Expanded Access,19 it is nevertheless important that patients understand what they are relinquishing. The corollary is that oncologists should take steps to help to ensure that patients understand their alternatives.

Faced with the prospect of death, many patients with cancer are willing to try investigational products. Oncologists need to help these patients to decide what course of action is optimal in light of patients’ values and interests. This ethical and professional responsibility includes the assessment of whether pre-approval access is advisable in particular circumstances and, if so, under which pathway. We maintain that oncologists should strongly prefer Expanded Access, but if they nonetheless proceed with Right to Try, they should take steps to ensure that patients are aware of the risks, potential benefits, and uncertainties about the investigational drug as well as the limits of the law. More broadly, oncologists and other practitioners should play a role in participating in deeper conversations within their institutions and with policymakers about unintended barriers to pre-approval access and what types of limits should be placed on such access, while keeping in mind the potential for different approaches to reinforce existing inequities in our health care system. Although the debate around Right to Try has highlighted the superiority of Expanded Access, now is the time to more systematically consider when and how physicians, manufacturers, and regulators should enable patients to try unproven, unapproved products.36

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Steven Joffe for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and Pamela C. Brannon for expert research assistance.

Footnotes

H.F.L. is supported by the Greenwall Foundation, A.S. is supported by Arnold Ventures, and R.H.V. is supported by National Cancer Institute Center Core Grant P30 CA016520 for this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Right to Try Requests and Oncologists’ Gatekeeping Obligations

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/journal/jco/site/ifc.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Holly Fernandez Lynch

Honoraria: WIRB-Copernicus Group

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: WIRB-Copernicus Group

Ameet Sarpatwari

Honoraria: New England Journal of Medicine

Research Funding: Anthem Public Policy Institute

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Kaiser Permanente

Robert H. Vonderheide

Consulting or Advisory Role: Eli Lilly, Verastem, Medimmune

Research Funding: Eli Lilly (Inst), Inovio (Inst), Apexigen (Inst), Fibrinogen (Inst), Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Inventor on patent related to cellular immunotherapy

Patricia J. Zettler

Expert Testimony: Direct Purchaser Class, End Payor Class, and Retailer Plaintiffs in In re Opana Antitrust Litigation, No. 14cv-10150 (N.D. Ill.), Direct Purchaser Class Plaintiffs in In re Suboxone Antitrust Litigation, No. 2:13-MD-2445 (E.D. Pa)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Trickett Wendler, Frank Mongiello, Jordan McLinn, and Matthew Bellina Right to Try Act. Pub L No 115-176: May 30, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/204/text.

- 2.Kearns L, Bateman-House A. Who stands to benefit? Right to try law provisions and implications. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51:170–176. doi: 10.1177/2168479017694849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corieri C. Everyone deserves the right to try: Empowering the terminally ill to take control of their treatment, 2014. https://goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/cms_page_media/2015/1/28/Right%20To%20Try.pdf.

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration Expanded access. 2019 https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/PublicHealthFocus/ExpandedAccessCompassionateUse/default.htm

- 5.Zettler PJ, Greely HT. The strange allure of state “right-to-try” laws. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1885–1886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joffe S, Lynch HF. Federal right-to-try legislation - threatening the FDA’s public health mission. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:695–697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bateman-House A, Robertson CT. The federal Right to Try Act of 2017—A wrong turn for access to investigational drugs and the path forward. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:321–322. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch HF, Zettler PJ, Sarpatwari A. Promoting patient interests in implementing the federal Right to Try act. JAMA. 2018;320:869–870. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caplan AL. Right-to-try laws provide little access to investigational drugs. We created a process that does, 2019. https://www.statnews.com/2019/06/03/effective-ethical-right-to-try-process. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roubein R: 40 patient advocacy groups oppose ‘right to try’ drug bill, 2018. https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/372600-40-patient-advocacy-groups-oppose-right-to-try-drug-bill.

- 11.Florko N. A year after Trump touted ‘right to try,’ patients still aren’t getting treatment, 2019. https://www.statnews.com/2019/01/29/right-to-try-patients-still-arent-getting-treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 12. ERC-USA initiates therapy under Right to Try law with first patient in California using investigational compound ERC1671 for treatment of glioblastoma, 2019. http://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2019/01/08/1682156/0/en/ERC-USA-Initiates-Therapy-Under-Right-to-Try-Law-With-First-Patient-In-California-Using-Investigational-Compound-ERC1671-for-Treatment-of-Glioblastoma.html.

- 13.Cortez M. Brain cancer patient is first to get untested treatment under Trump-backed law Bloomberg. 2019 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-10/brain-cancer-patient-gets-unproven-therapy-first-under-new-law

- 14.Folkers K, Chapman C, Redman B. Federal right to try: Where is it going? Hastings Cent Rep. 2019;49:26–36. doi: 10.1002/hast.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a. ERC Right-to-Try Policy, February 18, 2019, https://www.erc-immunotherapy.com/sites/default/files/ERC-Right-To-Try-Policy-15JULY2019.pdf.

- 15. Beacon of Hope CRO. https://www.bohcro.com.

- 15a. Knoepfler P: Richard Garr Q&A on his new Right-To-Try firm Beacon of Hope. Knoepfler Lab Stem Cell Blog. September 12, 2019. https://ipscell.com/2019/09/richard-garr-qa-on-right-to-try-firm-beacon-of-hope/

- 16.Trump D. Address to Faith and Freedom Coalition, Washington, DC, June 26, 2019. https://f2.link/190626a#69.

- 17. United States v Rutherford, 442 US 544 (1979)

- 18.US Food and Drug Administration Treatment use of investigational drugs: Guidance for institutional review boards and clinical investigators, 1998. http://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/treatment-use-investigational-drugs.

- 19.McKee AE, Markon AO, Chan-Tack KM, et al. How often are drugs made available under the Food and Drug Administration’s expanded access process approved? J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57:S136–S142. doi: 10.1002/jcph.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science: Global Oncology Trends 2018: Innovation, Expansion and Disruption, 2018. https://www.iqvia.com/institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2018.

- 21.Blumenthal GM, Pazdur R. Approvals in 2018: A histology-agnostic new molecular entity, novel end points and real-time review. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:139–141. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0170-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope TM. Why oncologists should decline to participate in the Right to Try Act. 2018 https://www.ascopost.com/issues/august-10-2018/declining-to-participate-in-the-right-to-try-act

- 23.Swetlitz I. https://www.statnews.com/2018/03/16/genetic-tests-fda-regulation Genetic tests ordered by doctors race to market, while ‘direct-to-consumer’ tests hinge on FDA approval, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer N, Thomas K. Drug sites upend doctor-patient relations: ‘It’s restaurant-menu medicine,’ 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/02/technology/for-him-for-hers-get-roman.html.

- 25.Jarow JP, Lemery S, Bugin K, et al. Ten-year experience for the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, part 2: FDA’s role in ensuring patient safety. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51:246–249. doi: 10.1177/2168479016679214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehmer J. Project Facilitate: Oncology Center of Excellence (OCE). https://www.fda.gov/media/127743/download.

- 27.McGinley L. FDA to make it easier for doctors to get unapproved cancer drugs for patients. 2019 https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2019/06/03/fda-make-it-easier-doctors-get-unapproved-cancer-drugs-patients/?utm_term=.3e65de12c03b

- 28.US Food and Drug Administration Requirements for all expanded access uses. 21 CFR 312.305, 2019.

- 29.Federation of State Medical Boards Regenerative and Stem Cell Therapy Practices: Report and Recommendations of the Workgroup to Study Regenerative and Stem Cell Therapy Practices. 2018 http://www.fsmb.org/siteassets/advocacy/policies/fsmb-stem-cell-workgroup-report.pdf

- 30. Ariz Rev Stat 32-1401(c)(27), 2017.

- 31. Ala Code 34-24-360(7), 2007.

- 32.Bateman-House A. “Right to try” is law, now what?: Part 1. Health Affairs Blog, October 25, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20181024.111856/full.

- 33.Blake V. The terminally ill, access to investigational drugs, and FDA rules. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15:687–691. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.8.hlaw1-1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roubein R, Harper C. Hopes rise for law to expand access to experimental drugs. 2017 https://thehill.com/policy/healthcare/320470-hopes-rise-for-law-to-expand-access-to-experimental-drugs

- 35.Thomas K. Why can’t dying patients get the drugs they want? 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/23/health/right-to-try-drugs-fda.html

- 36.Florko N. When ‘right to try’ isn’t enough: Congress wants a single ALS patient to get a therapy never tested in humans, 2019. https://www.statnews.com/2019/05/31/when-right-to-try-isnt-enough. [Google Scholar]