Abstract

Background

Sweeping of the membranes, also named stripping of the membranes, is a relatively simple technique usually performed without admission to hospital. During vaginal examination, the clinician's finger is introduced into the cervical os. Then, the inferior pole of the membranes is detached from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. This intervention has the potential to initiate labour by increasing local production of prostaglandins and, thus, reduce pregnancy duration or pre‐empt formal induction of labour with either oxytocin, prostaglandins or amniotomy. This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardised methodology.

Objectives

To determine the effects of membrane sweeping for third trimester induction of labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register (6 July 2004) and bibliographies of relevant papers.

We updated this search on 31 July 2009 and added the results to the awaiting classification section.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing membrane sweeping used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction.

Main results

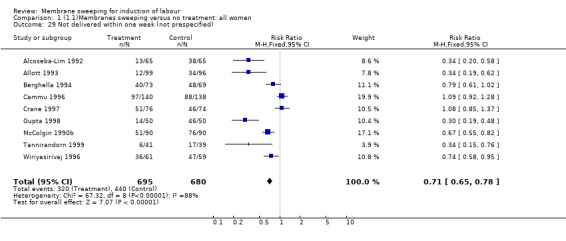

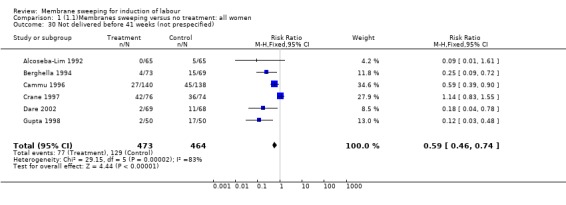

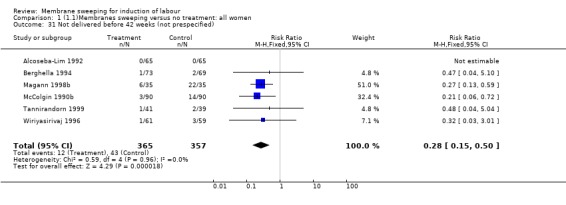

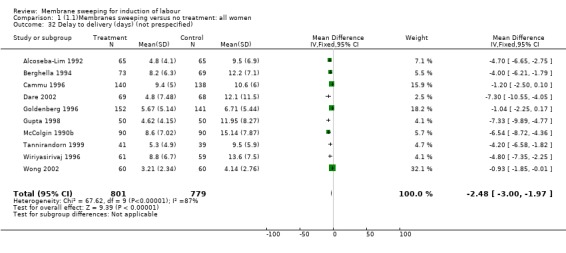

Twenty‐two trials (2797 women) were included, 20 comparing sweeping of membranes with no treatment, three comparing sweeping with prostaglandins and one comparing sweeping with oxytocin (two studies reported more than one comparison). Risk of caesarean section was similar between groups (relative risk (RR) 0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.15). Sweeping of the membranes, performed as a general policy in women at term, was associated with reduced duration of pregnancy and reduced frequency of pregnancy continuing beyond 41 weeks (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.74) and 42 weeks (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.50). To avoid one formal induction of labour, sweeping of membranes must be performed in eight women (NNT = 8). There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of maternal or neonatal infection. Discomfort during vaginal examination and other adverse effects (bleeding, irregular contractions) were more frequently reported by women allocated to sweeping. Studies comparing sweeping with prostaglandin administration are of limited sample size and do not provide evidence of benefit.

Authors' conclusions

Routine use of sweeping of membranes from 38 weeks of pregnancy onwards does not seem to produce clinically important benefits. When used as a means for induction of labour, the reduction in the use of more formal methods of induction needs to be balanced against women's discomfort and other adverse effects.

[Note: The 11 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Plain language summary

Membrane sweeping for induction of labour

Sweeping the membranes is effective in bringing on labour but causes discomfort, some bleeding and irregular contractions.

Sweeping the membranes during a cervical examination is done to bring on labour in women at term. The review of trials found that sweeping brings on labour and is generally safe where there are no other complications. Sweeping reduces the need for other methods of labour induction such as oxytocin or prostaglandins. The review also found that sweeping can cause discomfort during the procedure, some bleeding and irregular contractions.

Background

This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

Stripping/sweeping of the membranes is an old method for inducing labour (Hamilton 1810). In this review we will use the word 'sweeping' instead of 'stripping', but both words describe the same intervention. The goal of sweeping of the membranes is to initiate labour through a cascade of physiological events, and thus to reduce pregnancy duration or to pre‐empt formal induction of labour with either oxytocin, prostaglandins or amniotomy.

This intervention is currently performed by a large number of clinicians. The technique is relatively simple: during vaginal examination, the clinician's finger is introduced into the cervical os. Then, the inferior pole of the membranes is detached from the lower uterine segment by a circular movement of the examining finger. Increased local production of prostaglandins, which have been documented following this procedure, provide a plausible mechanism for a potential effect of this intervention on pregnancy duration (Keirse 1983). When the membranes cannot be reached, some clinicians attempt to stretch the cervix until sweeping is feasible (Goldenberg 1996). When the cervix is closed, some perform a cervical massage to stimulate the production of prostaglandins (El‐Torkey 1992). All these interventions were considered together in this review.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of membrane sweeping for third trimester cervical ripening and induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing membrane sweeping for cervical ripening or labour induction, with either vaginal examination (with or without cervical assessment), no vaginal examination or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see 'Methods of the review'); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the prestated outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Predefined subgroup analyses are: previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data will appear in the analysis tables.

Types of interventions

Sweeping of membranes consists of a digital separation of the membranes from the lower uterine segment during vaginal examination. Membrane sweeping was compared with placebo/no treatment or any other method above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction. Placebo/no treatment in this case could be either no vaginal examination or vaginal examination for cervical assessment only (by Bishop score or other scoring scale), without the intention to detach the membranes.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by the authors of the labour induction generic protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Subgroup analyses were limited to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction:

Measures of effectiveness: (6) cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications: (8) uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side‐effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction: (26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

'Uterine rupture' will include all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. Trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery will be excluded.

Additional outcomes may appear in individual primary reviews, but will not contribute to the secondary reviews.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews we use the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes 'to include uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with fetal heart rate changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability).

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Sweeping of membranes is generally performed as an outpatient procedure without the goal of immediate induction of labour. In a previous version of this review, the following prespecified outcome measures were included:

For studies evaluating sweeping as a general intervention performed at 38 to 40 weeks to prevent post‐term pregnancy: proportion of women continuing pregnancy beyond 41 and beyond 42 weeks.

For studies evaluating sweeping as a method of induction of labour: proportion of women receiving 'formal' induction of labour (defined as use of amniotomy, oxytocin or prostaglandins in women not having contractions).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register (6 July 2004).

We updated this search on 31 July 2009 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

The first search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of trial reports and reviews.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, in many different categories of women undergoing labour induction. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged by category of woman, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We therefore developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The data will then be extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by category of woman.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods have been listed in a specific order, from one to 25. Each primary review includes comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 25) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) will include only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

placebo/no treatment;

vaginal prostaglandins;

intracervical prostaglandins;

intravenous oxytocin;

amniotomy;

intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy;

vaginal misoprostol;

oral misoprostol;

mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter;

membrane sweeping;

extra‐amniotic prostaglandins;

intravenous prostaglandins;

oral prostaglandins;

mifepristone;

estrogens;

corticosteroids;

relaxin;

hyaluronidase;

castor oil, bath, and/or enema;

acupuncture;

breast stimulation;

sexual intercourse;

homoeopathic methods.

nitric oxide

buccal or sublingual misoprostol;

hypnosis.

The primary reviews will be analysed by the following subgroups:

previous caesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

The secondary reviews will include all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews, and will include only five primary outcome measures. There will thus be six secondary reviews of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous caesarean section, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous caesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which include data which have changed, will also be updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data were extracted to a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous reviewers in the area of induction of labour.

Information was extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process was completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examines the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These were then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Appendix 1 for the purpose of the reviews.

Performance bias was examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials, i.e. participant, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels were sought.

Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prestated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 1999). Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis was performed if possible). Where data were missing, clarification was sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data were excluded from the analysis. This decision rests with the reviewers of primary reviews and is clearly documented. Once missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data were extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting is poor, methodological issues are reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data were extracted, they were distributed to individual reviewers for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 1999), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed effect model. Number‐needed to treat (NNT) were also reported.

From 2001, the data extraction is no longer conducted centrally. This means that the data extraction is now carried out by the reviewers of the primary reviews if new trials are found when the search and the review are updated.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis included all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and subgroup analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or subgroups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

This review was conducted before the global strategy to review methods of labour induction was designed. Therefore, in addition to the methods described above, identification of studies, assessment of quality and data extraction were also performed by two of the authors (Michel Boulvain, Olivier Irion). As sweeping of membranes is generally performed to avoid post‐term pregnancy or formal induction of labour by other methods, these outcomes were considered as important in the original review and included in the present update.

Results

Description of studies

See 'Table: Characteristics of included studies'.

Studies conducted to evaluate sweeping of the membranes could be divided in two groups: (1) studies assessing a general policy of sweeping of the membranes at 38 to 40 weeks to prevent post‐term pregnancy; (2) studies assessing sweeping of the membranes as a method for induction of labour (or to pre‐empt more formal induction of labour).

Regarding studies conducted by McColgin et al, it is unclear whether women in the larger study (McColgin 1990b) include those in the smaller one (McColgin 1990a). Information on this issue was sought, but is not yet available. Therefore, only the larger study is included in the meta‐analysis, except when outcomes were reported only in the smaller trial. One trial (Cammu 1996) included only nulliparous women. Results of this study were included, as there is at present no evidence of effect modification according to parity. One study (Netta 2002) evaluated group B streptococcus colonisation associated with sweeping of the membranes. There seems to be no additional risk in women with sweeping, but the study is too small to rule out an effect. The number of inductions of labour in nulliparous women was the only outcome reported in the publication (a conference abstract).

(Ten reports from an updated search in July 2009 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias during assignment

Most trials report on their method for randomisation, which was generally based on a computer generated sequence or a table of random numbers. Alcoseba‐Lim 1992; Doany 1997; Goldenberg 1996; Magann 1998a; McColgin 1990b; Salamalekis 2000; Tannirandorn 1999; and Weissberg 1977 do not report on the method of concealment of the allocation. In one study (Doany 1997), the number of women per group is unequal, without explanation for the reasons in the report.

Risk of selection bias because of exclusions

Some women have been excluded from the analysis in the following trials: McColgin 1990b: 29 women (see Tables for details); Goldenberg 1996: nine women (all in the sweeping group); Boulvain 1998: two women (both in control group); Berghella 1994: seven women (all in the sweeping group, because of unfavourable cervix); Doany 1997: seven women because of missing data (delivery outside the hospital); Tannirandorn 1999: 16 women (seven in the sweeping group and nine in the control group).

Risk of bias in assessing the outcomes

The nature of the intervention does not permit blinding of the clinician as to the allocated intervention. Blinding of women is difficult because of discomfort associated with the intervention and increased duration of the vaginal examination. Definition of a primary outcome measure which would not be prone to biased assessment is therefore important. For studies assessing sweeping of the membranes as a method to prevent post‐term pregnancy, delivery after 41 or 42 weeks could be considered as an important outcome measure. All authors reported on the method to assess gestational age, and gestational age assessment was probably performed similarly in either group. When the outcome measure was 'delay before onset of labour', definition of spontaneous labour was given by Goldenberg 1996, but not by other authors. Therefore, a potential bias in the determination of time of onset of labour cannot be ruled out. For studies evaluating sweeping of membranes as a method to induce labour, a date for induction of labour by other methods (formal induction of labour) was given prior to randomisation by Boulvain 1998. A deadline date was given by Allott 1993 and Wong 2002, but it was unclear whether this date was given prior to randomisation. El‐Torkey 1992 gave the date for formal induction knowing the group allocation. Cammu 1996, Crane 1997, Doany 1997, Gupta 1998, Magann 1998a, Magann 1998b and Wiriyasirivaj 1996 stated that labour was induced when gestational age reached 41 or 42 weeks.

The above comments must be considered in the light of the fact that one of the authors of this review is also the author of one of the trials included.

Effects of interventions

Twenty‐two trials are included (2797 women).

Comparison of sweeping the membranes and no treatment

Thirteen studies including women at 37 to 40 weeks' gestation and six studies including women at or beyond 40 weeks' gestation were conducted. A total of 2389 women participated in these studies.

Primary outcomes

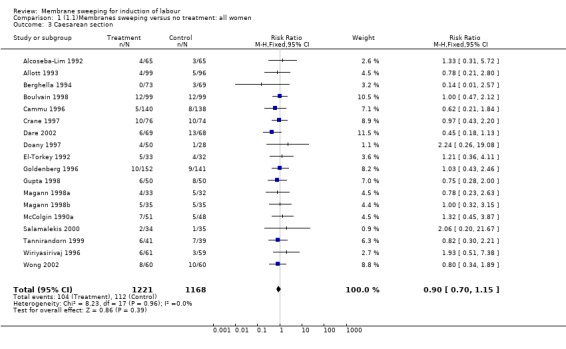

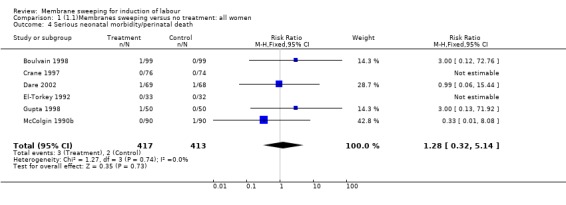

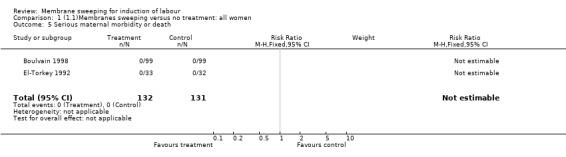

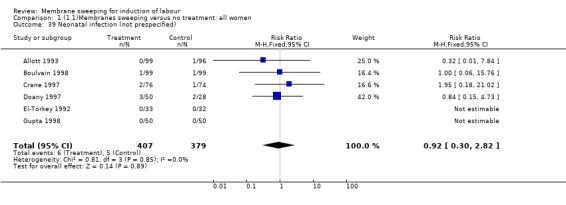

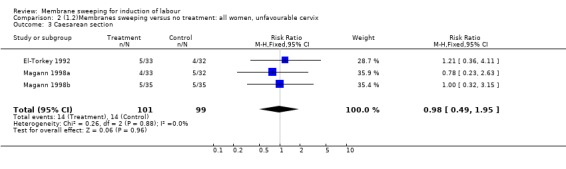

Because sweeping of membranes is not generally aiming at inducing labour in the short‐term and is usually performed as an outpatient procedure, primary outcomes as 'vaginal delivery not achieved in 24 hours' and 'uterine hyperstimulation' were not reported by the investigators. The risk of caesarean section was not modified by the intervention (relative risk (RR): 0.90; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.70 to 1.15). Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death was infrequent and similar between groups (3/417 versus 2/413). Serious maternal morbidity or death was not reported.

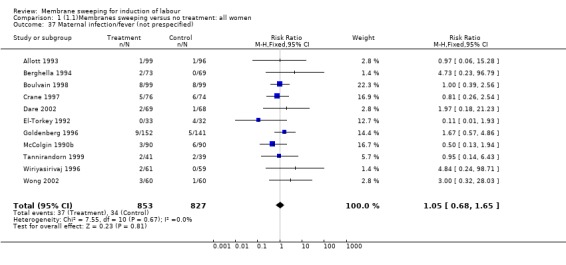

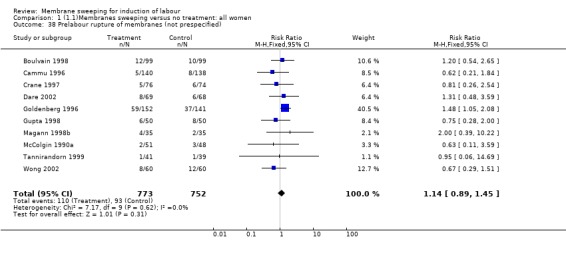

Secondary outcomes

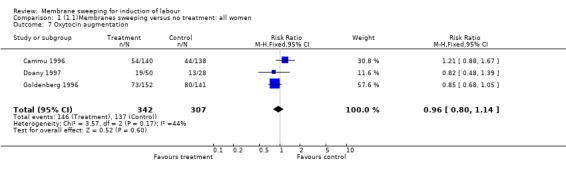

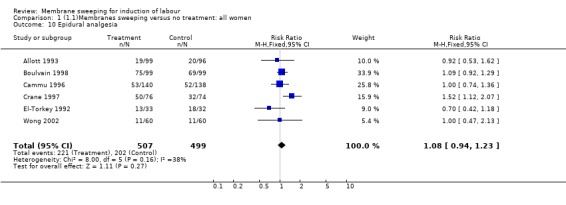

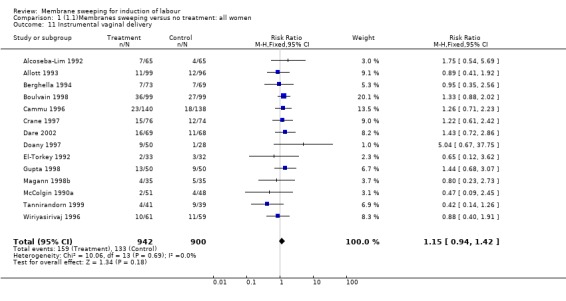

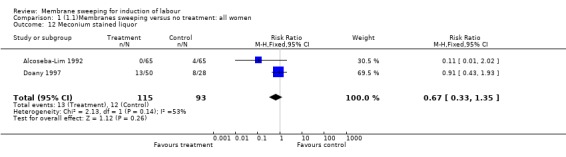

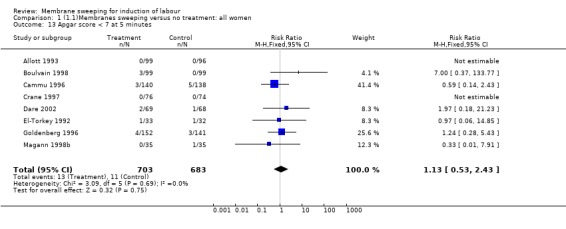

Changes in cervical status at 12 and 24 hours were not reported by any authors. Oxytocin augmentation (RR: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.80 to 1.14), use of epidural analgesia (RR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.23) and instrumental delivery (RR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.94 to 1.42) were similar between groups. Meconium stained liquor (RR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.33 to 1.35), Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (RR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.53 to 2.43) and neonatal intensive care unit admission (RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.63) were also similar. Two perinatal deaths were reported in each group. Postpartum haemorrhage was infrequently reported. In Doany 1997, seven women among 28 had postpartum haemorrhage (not defined) in the control group, as compared to none among 50 in the sweeping group. No difference was found by the other authors reporting this outcome (Tannirandorn 1999; Wiriyasirivaj 1996 ). Prelabour rupture of membranes (RR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.89 to 1.45) maternal infection/fever (RR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.68 to 1.65) and neonatal infection (as defined by the authors of the original studies) (RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.30 to 2.82) were similar between groups. No major maternal side‐effect was reported in the trials. However, in the trials that assessed, systematically, minor side‐effects and women's discomfort during the procedure, women in the sweeping group reported significantly more pain during vaginal examination (Boulvain 1998; Wong 2002). In the first study (Boulvain 1998), pain was assessed by the Short Form of the McGill Pain Questionnaire, that includes three scales: a visual analogue scale (0 to 10 cm), the present pain index (0 to 5) and a set of 15 descriptors of pain scoring 0 to 3 (Melzack 1987). Median scores for each of the items were significantly higher in women allocated to sweeping of membranes. In addition, more women allocated to sweeping experienced vaginal bleeding and painful contractions not leading to onset of labour during the 24 hours following the intervention. In the second trial (Wong 2002), the authors report that 70% of women reported that the procedure was associated with significant discomfort and one third with significant pain.

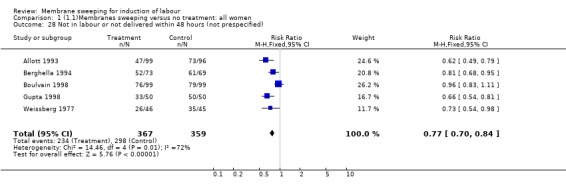

Sweeping the membranes in women at term generally reduces the delay between randomisation and spontaneous onset of labour, or between randomisation and delivery, by a mean of three days. This must be interpreted in the light of the fact that the effect is more apparent in the smaller studies, as compared to the larger ones. This raises the suspicion of a publication bias. Sweeping the membranes increased the likelihood of either spontaneous labour within 48 hours (RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.70 to 0.84) or of delivery within one week (RR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.65 to 0.78). Sweeping the membranes performed as a general policy from 38 to 40 weeks onwards decreased the frequency of 'post‐term' pregnancy defined as pregnancy continuing beyond 42 weeks (RR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.50; NNT: 11) and beyond 41 weeks (RR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.46 to 0.74; NNT: 9).

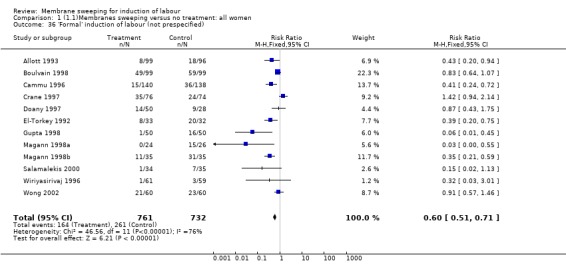

A reduction in the frequency of using other methods to induce labour ('formal induction of labour') in women allocated to sweeping was reported in most trials (RR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.71). The overall risk reduction in the available trials was 14%. About eight women need to have sweeping of membranes to avoid one formal induction of labour. These results must be interpreted with caution, as important heterogeneity was found in trials' results.

Comparison of sweeping the membranes and prostaglandins

Three studies (339 women) compared sweeping and prostaglandins (PG). Doany 1997 compared sweeping of membranes to intravaginal PGE2 gel (2 mg). Magann compared daily sweeping of membranes to daily intracervical PGE2 gel (0.5 mg) (Magann 1998b) and with daily intravaginal insert (Magann 1999). No conclusions can be drawn because of the small number of participants in individual trials and the differences between the study designs.

Comparison of sweeping the membranes and oxytocin

Only one study with limited sample size (69 women) compared these two options. No difference was found in the risk of caesarean section.

Discussion

The available data suggest that sweeping of the membranes promotes the onset of labour. When performed in unselected women, sweeping of the membranes reduces the risk of post‐term pregnancy and the use of other methods of induction of labour. However, the rationale for performing routinely an intervention with the potential to induce labour in women with an uneventful pregnancy at 38 weeks of gestation is, at least, questionable. Sweeping of the membranes has less predictable results than the other methods and the intervention is probably not appropriate if urgent induction of labour is indicated. When the reason for induction is non‐urgent, some women may prefer sweeping of membranes instead of more formal methods for labour induction.

Sweeping the membranes was not shown to be associated with benefits on primary outcomes prespecified in the series of reviews on methods of induction of labour. The frequency of major side‐effects was not increased, but women in the sweeping group reported discomfort during the intervention, bleeding and irregular contractions. This must be taken into account while discussing management options with women for whom induction of labour is decided.

Limitations of this systematic review include the relatively small size of the studies, heterogeneity between trials' results for some outcomes and the suspicion of publication bias. The heterogeneity between trials results could result from methodological differences between studies. Given the small numbers of women included in most trials and the fact that clinicians and women were not blinded as to group allocation, a bias in delaying formal induction in even a small number of women in either group may have large consequences on the risk estimate. To minimise this risk of bias, a preset date for labour induction by other methods in the case of failure of sweeping of the membranes was given in one trial (Boulvain 1998), and possibly in others (Allott 1993; Wong 2002). Also, the results for several outcomes should be interpreted taking into account a possible publication bias.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The available evidence suggests that sweeping the membranes promotes the onset of labour. For women thought to require induction of labour, a reduction in the use of more formal methods of induction could be expected. For women near term (37 to 40 weeks of gestation) in an uncomplicated pregnancy there seems to be little justification for performing routine sweeping of membranes. Sweeping of the membranes is probably safe, provided that the intervention is avoided in pregnancies complicated by placenta praevia or when contraindications for labour and/or vaginal delivery are present. There is no evidence that sweeping the membranes increases the risk of maternal and neonatal infection, or of premature rupture of the membranes. However, women's discomfort during the procedure and other side‐effects must be balanced with the expected benefits before submitting women to sweeping of the membranes.

Implications for research.

Future studies should stratify the participants according to cervical status and/or parity, in order to determine if sweeping of the membranes is more effective in specific subgroups.

[Note: The 11 citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 July 2009 | Amended | Search updated. Ten new reports added to Studies awaiting classification (de Miranda 2006; Hill 2006; Hill 2008; Hill 2008a; Ifnan 2006; Imsuwan 1999; Kashanian 2006; Kaul 2004; Tan 2006; Yildirim 2008). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1997 Review first published: Issue 4, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 9 November 2004 | New search has been performed | We have added two new trials (Dare 2002; Wong 2002) , one new ongoing trial (Manidakis 1999) and a new report of Magann 1998b. We have excluded four new trials (Bergsjo 1989; Foong 2000; Gemer 2001; McColgin 1993). |

Acknowledgements

This review was originally conducted by Prof MJNC Keirse. Michel Boulvain received salary support from Prof Wollast to prepare an earlier version of this review. We thank Irene Kwan, NCCWCH, London, for spotting a (now corrected) error.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methodological quality of trials

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence. | Computer generated sequence, random number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation. | Central randomisation, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 18 | 2389 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.70, 1.15] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death | 6 | 830 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.32, 5.14] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 2 | 263 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 3 | 649 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.80, 1.14] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 6 | 1006 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.94, 1.23] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 14 | 1842 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.94, 1.42] |

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 2 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.33, 1.35] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 8 | 1386 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.53, 2.43] |

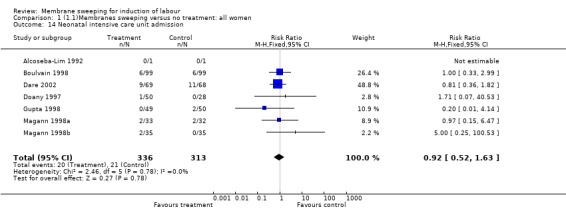

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 7 | 649 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.52, 1.63] |

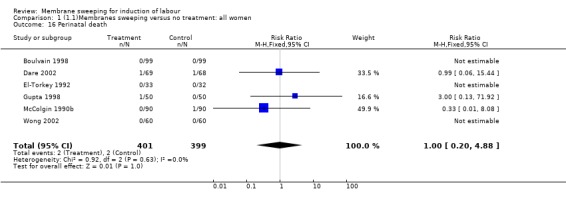

| 16 Perinatal death | 6 | 800 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.20, 4.88] |

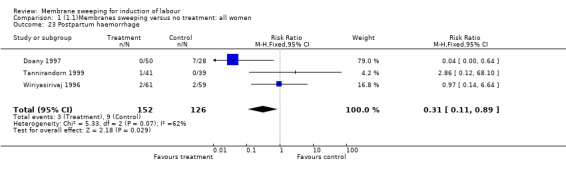

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 3 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.11, 0.89] |

| 28 Not in labour or not delivered within 48 hours (not prespecified) | 5 | 726 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.70, 0.84] |

| 29 Not delivered within one week (not prespecified) | 9 | 1375 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.65, 0.78] |

| 30 Not delivered before 41 weeks (not prespecified) | 6 | 937 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.46, 0.74] |

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 6 | 722 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.28 [0.15, 0.50] |

| 32 Delay to delivery (days) (not prespecified) | 10 | 1580 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.48 [‐3.00, ‐1.97] |

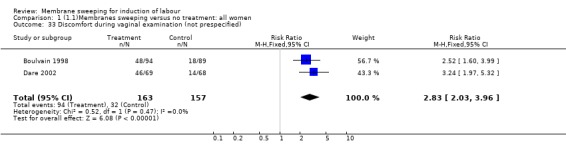

| 33 Discomfort during vaginal examination (not prespecified) | 2 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [2.03, 3.96] |

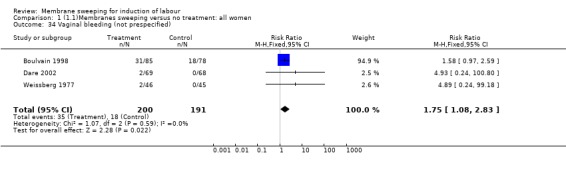

| 34 Vaginal bleeding (not prespecified) | 3 | 391 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.75 [1.08, 2.83] |

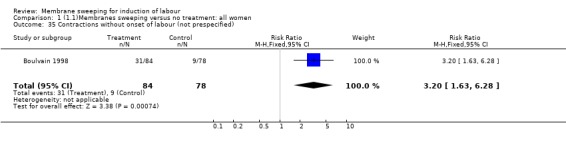

| 35 Contractions without onset of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 162 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.20 [1.63, 6.28] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 12 | 1493 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.51, 0.71] |

| 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified) | 11 | 1680 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.68, 1.65] |

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 10 | 1525 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.89, 1.45] |

| 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified) | 6 | 786 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.30, 2.82] |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 28 Not in labour or not delivered within 48 hours (not prespecified).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 29 Not delivered within one week (not prespecified).

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 30 Not delivered before 41 weeks (not prespecified).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 32 Delay to delivery (days) (not prespecified).

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 33 Discomfort during vaginal examination (not prespecified).

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 34 Vaginal bleeding (not prespecified).

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 35 Contractions without onset of labour (not prespecified).

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

1.37. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified).

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1 (1.1)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, Outcome 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified).

Comparison 2. (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

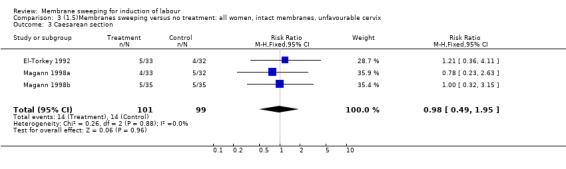

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.49, 1.95] |

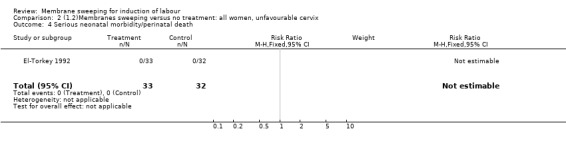

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

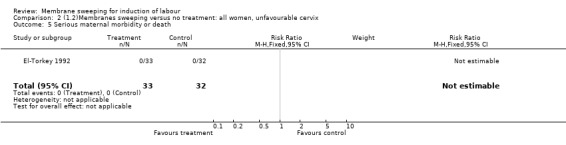

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

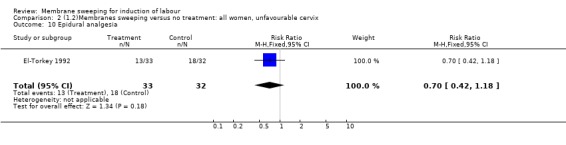

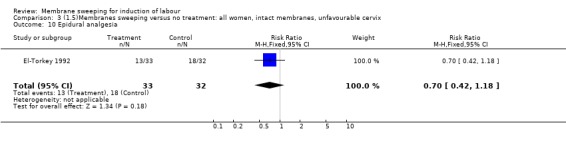

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.42, 1.18] |

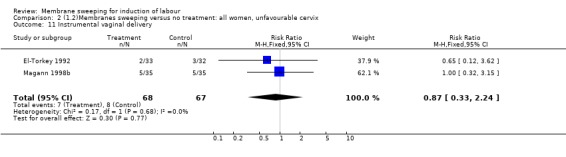

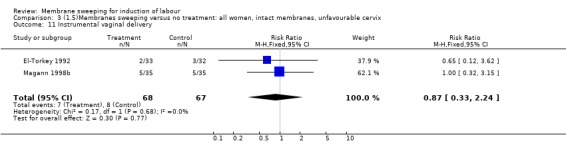

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.33, 2.24] |

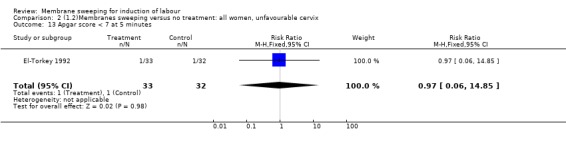

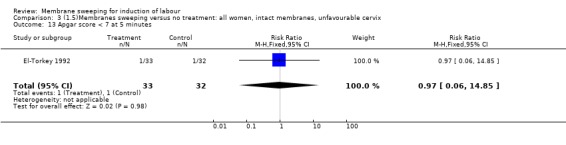

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.06, 14.85] |

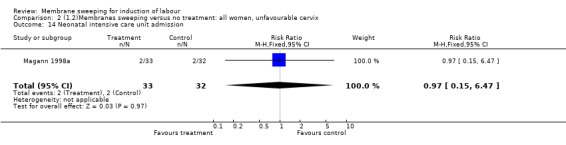

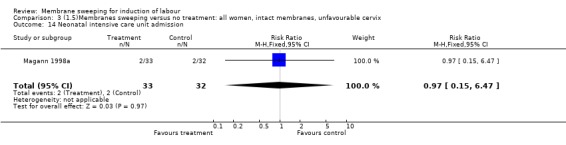

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.15, 6.47] |

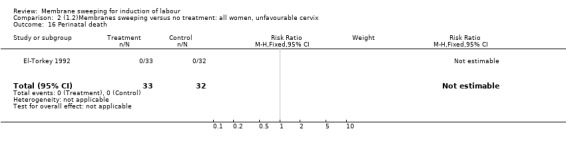

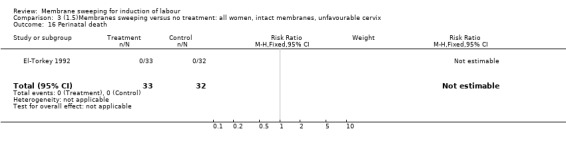

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

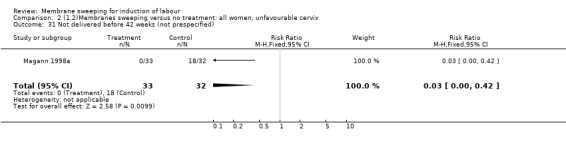

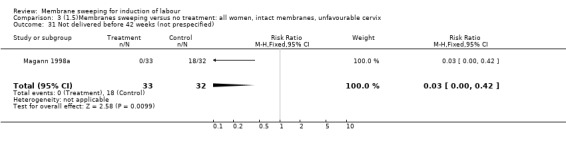

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [0.00, 0.42] |

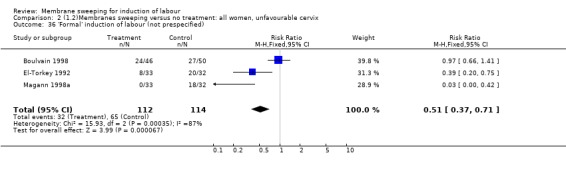

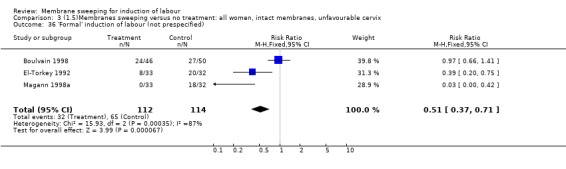

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 3 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.37, 0.71] |

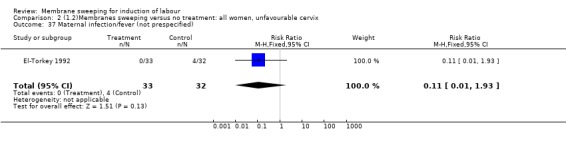

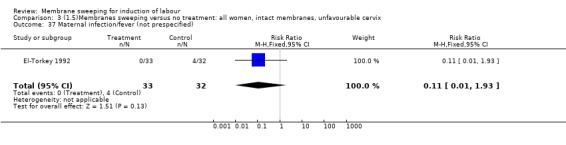

| 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 1.93] |

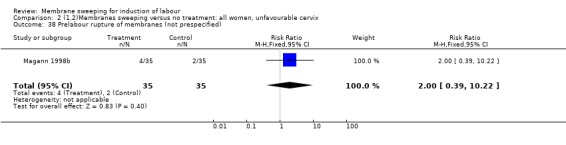

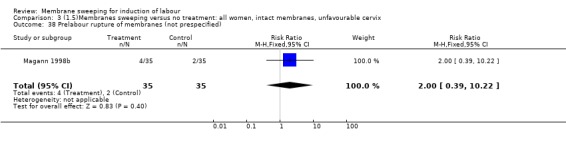

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.39, 10.22] |

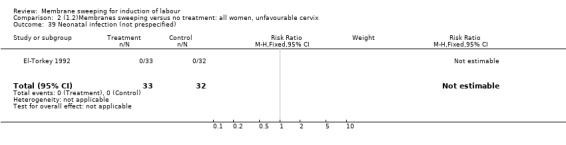

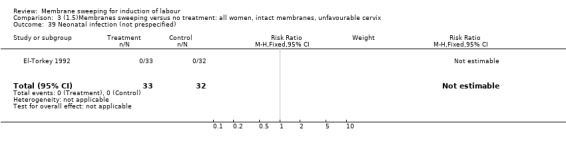

| 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

2.31. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

2.36. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

2.37. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified).

2.38. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

2.39. Analysis.

Comparison 2 (1.2)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified).

Comparison 3. (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.49, 1.95] |

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.42, 1.18] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.33, 2.24] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.06, 14.85] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.15, 6.47] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [0.00, 0.42] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 3 | 226 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.37, 0.71] |

| 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 1.93] |

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.39, 10.22] |

| 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified) | 1 | 65 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

3.13. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

3.14. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

3.16. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

3.31. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

3.36. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

3.37. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 37 Maternal infection/fever (not prespecified).

3.38. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

3.39. Analysis.

Comparison 3 (1.5)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all women, intact membranes, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified).

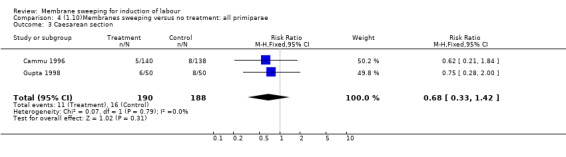

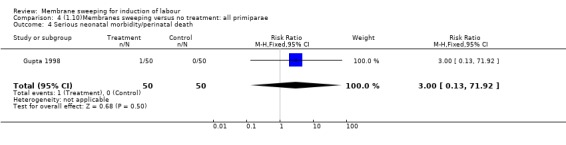

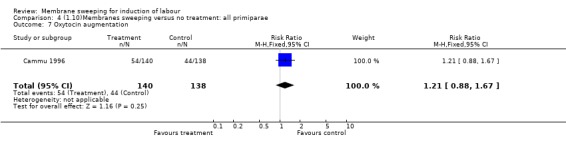

Comparison 4. (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.33, 1.42] |

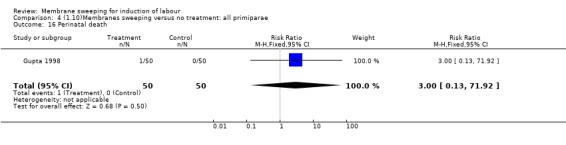

| 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.88, 1.67] |

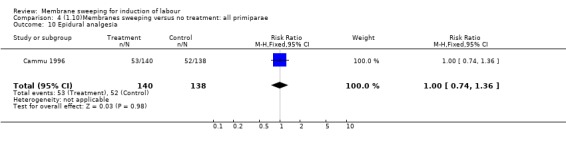

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.74, 1.36] |

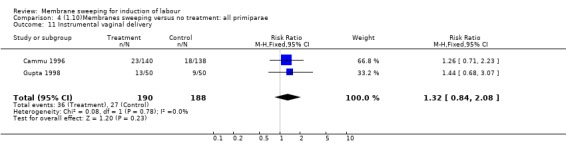

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.84, 2.08] |

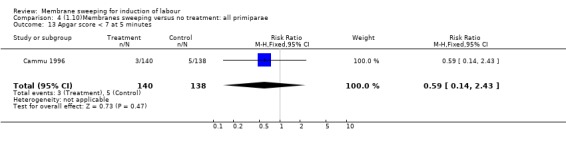

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 278 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.14, 2.43] |

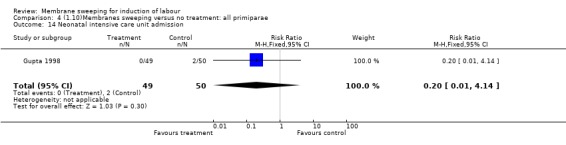

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 4.14] |

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

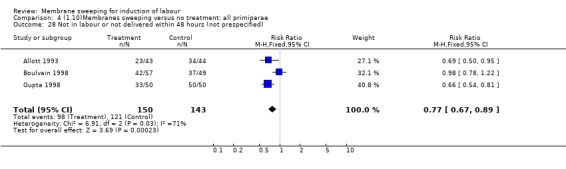

| 28 Not in labour or not delivered within 48 hours (not prespecified) | 3 | 293 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.67, 0.89] |

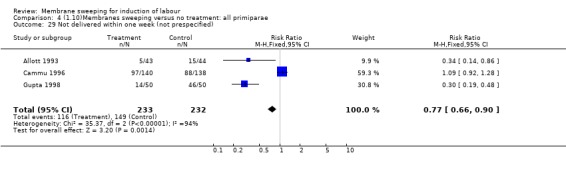

| 29 Not delivered within one week (not prespecified) | 3 | 465 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.66, 0.90] |

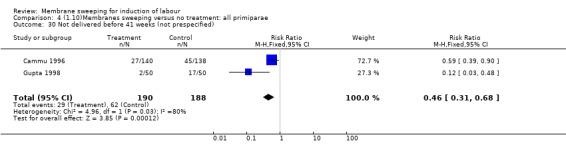

| 30 Not delivered before 41 weeks (not prespecified) | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.31, 0.68] |

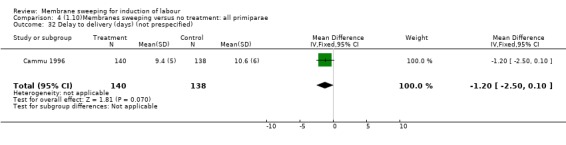

| 32 Delay to delivery (days) (not prespecified) | 1 | 278 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.20 [‐2.50, 0.10] |

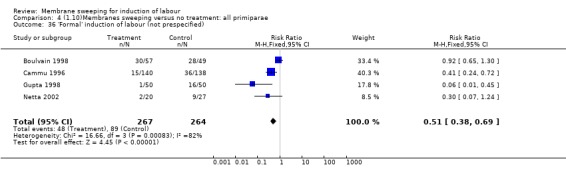

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 4 | 531 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.38, 0.69] |

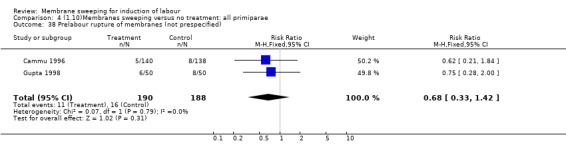

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 2 | 378 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.33, 1.42] |

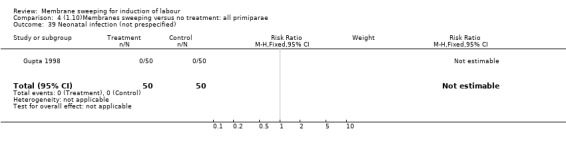

| 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified) | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 4 Serious neonatal morbidity/perinatal death.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

4.11. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

4.13. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

4.14. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

4.16. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

4.28. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 28 Not in labour or not delivered within 48 hours (not prespecified).

4.29. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 29 Not delivered within one week (not prespecified).

4.30. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 30 Not delivered before 41 weeks (not prespecified).

4.32. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 32 Delay to delivery (days) (not prespecified).

4.36. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

4.38. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

4.39. Analysis.

Comparison 4 (1.10)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified).

Comparison 5. (1.19)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all multiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

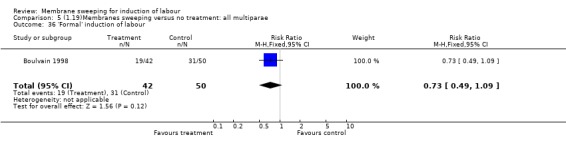

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour | 1 | 92 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.49, 1.09] |

5.36. Analysis.

Comparison 5 (1.19)Membranes sweeping versus no treatment: all multiparae, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour.

Comparison 10. (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

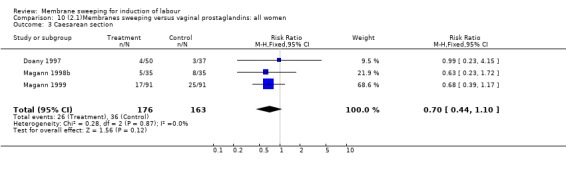

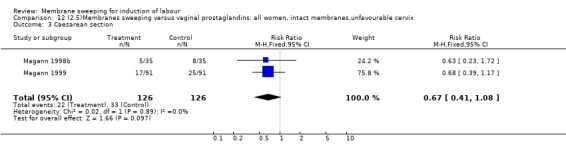

| 3 Caesarean section | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.44, 1.10] |

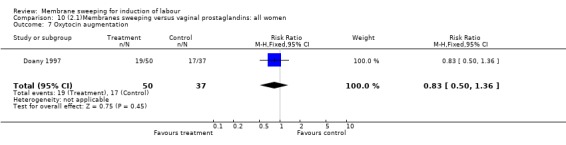

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.50, 1.36] |

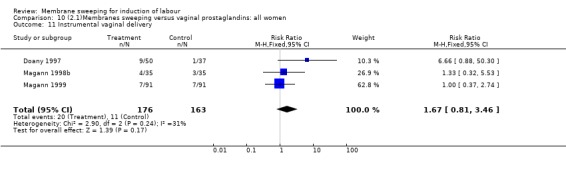

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.81, 3.46] |

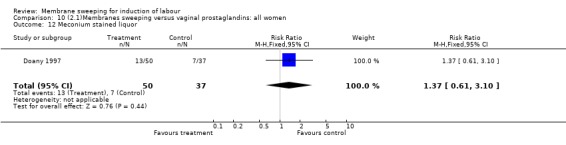

| 12 Meconium stained liquor | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [0.61, 3.10] |

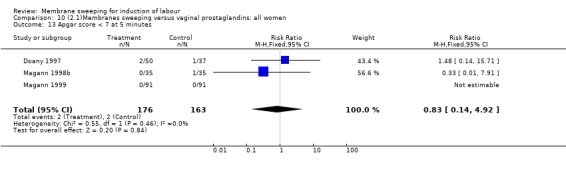

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.14, 4.92] |

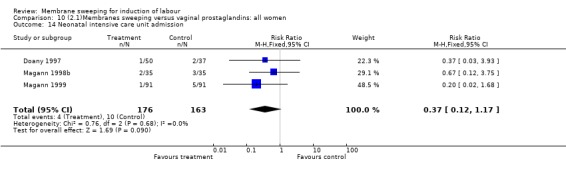

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.37 [0.12, 1.17] |

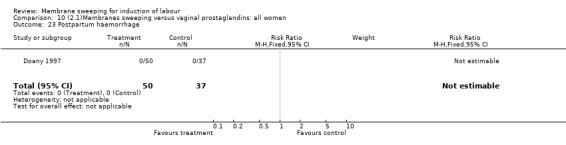

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

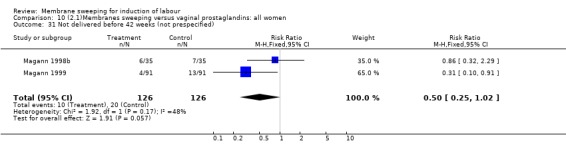

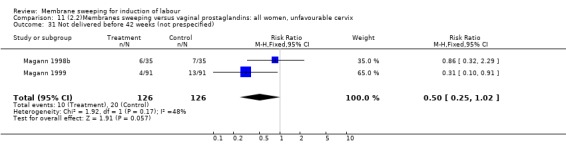

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.25, 1.02] |

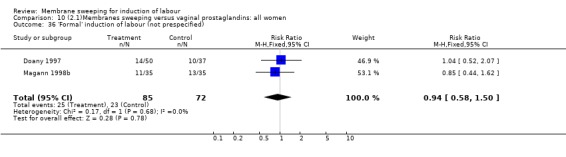

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 2 | 157 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.58, 1.50] |

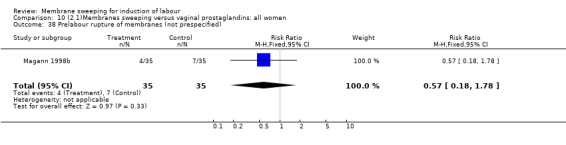

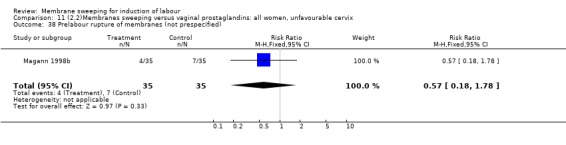

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.78] |

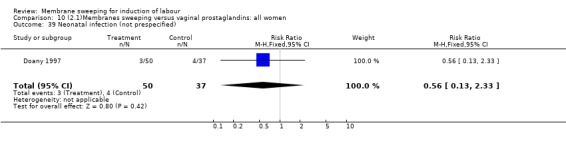

| 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified) | 1 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.13, 2.33] |

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

10.11. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

10.12. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium stained liquor.

10.13. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

10.14. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

10.23. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

10.31. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

10.36. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

10.38. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

10.39. Analysis.

Comparison 10 (2.1)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, Outcome 39 Neonatal infection (not prespecified).

Comparison 11. (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

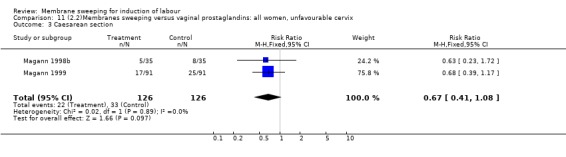

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.41, 1.08] |

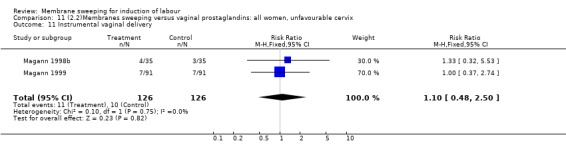

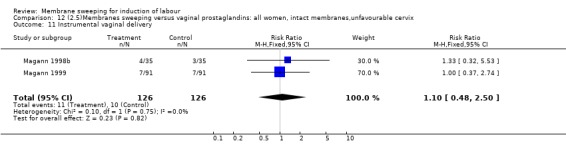

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.48, 2.50] |

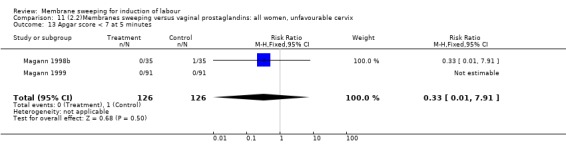

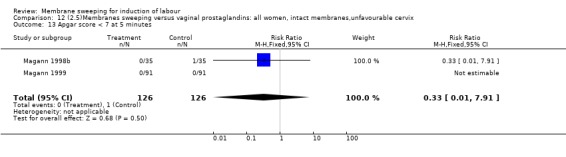

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.91] |

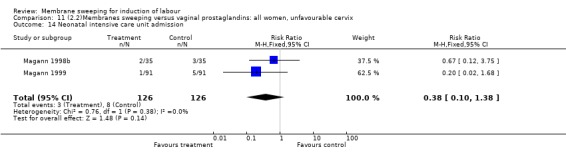

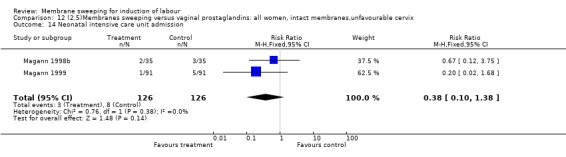

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.10, 1.38] |

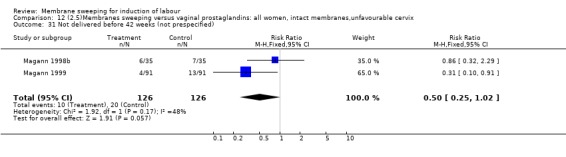

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.25, 1.02] |

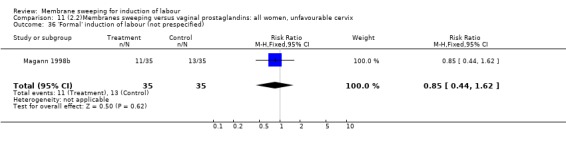

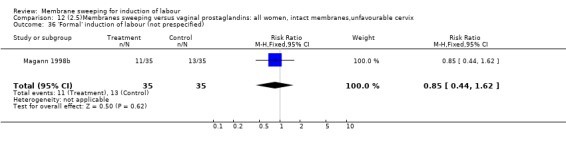

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.44, 1.62] |

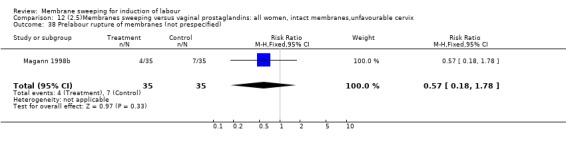

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.78] |

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

11.11. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

11.13. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

11.14. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

11.31. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

11.36. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

11.38. Analysis.

Comparison 11 (2.2)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

Comparison 12. (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.41, 1.08] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.48, 2.50] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.91] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.10, 1.38] |

| 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified) | 2 | 252 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.25, 1.02] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.44, 1.62] |

| 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified) | 1 | 70 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.18, 1.78] |

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

12.11. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

12.13. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

12.14. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

12.31. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 31 Not delivered before 42 weeks (not prespecified).

12.36. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

12.38. Analysis.

Comparison 12 (2.5)Membranes sweeping versus vaginal prostaglandins: all women, intact membranes,unfavourable cervix, Outcome 38 Prelabour rupture of membranes (not prespecified).

Comparison 20. (4.1)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

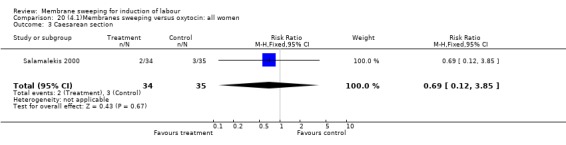

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.12, 3.85] |

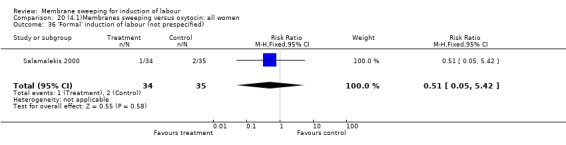

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.42] |

20.3. Analysis.

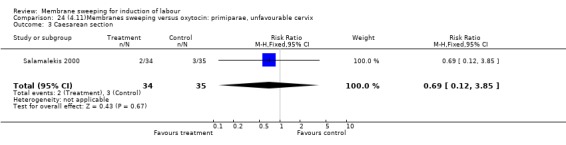

Comparison 20 (4.1)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

20.36. Analysis.

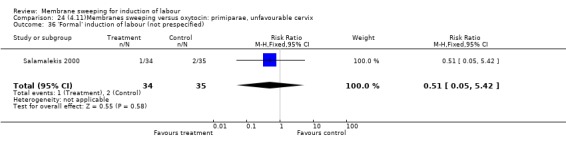

Comparison 20 (4.1)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

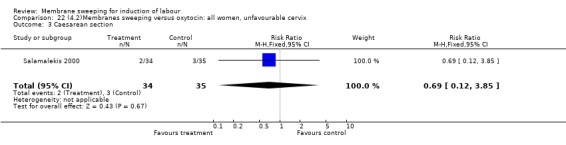

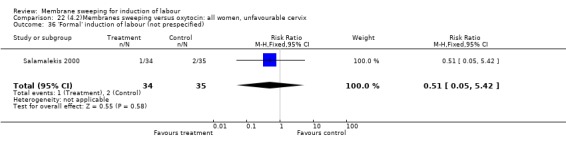

Comparison 22. (4.2)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.12, 3.85] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.42] |

22.3. Analysis.

Comparison 22 (4.2)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

22.36. Analysis.

Comparison 22 (4.2)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all women, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

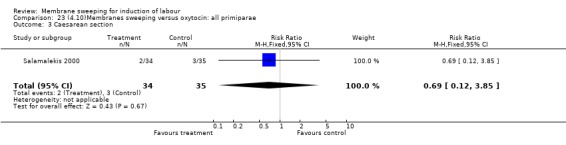

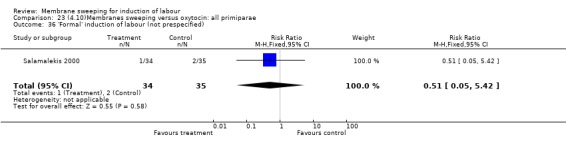

Comparison 23. (4.10)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.12, 3.85] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.42] |

23.3. Analysis.

Comparison 23 (4.10)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

23.36. Analysis.

Comparison 23 (4.10)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

Comparison 24. (4.11)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: primiparae, unfavourable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.12, 3.85] |

| 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified) | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.05, 5.42] |

24.3. Analysis.

Comparison 24 (4.11)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

24.36. Analysis.

Comparison 24 (4.11)Membranes sweeping versus oxytocin: primiparae, unfavourable cervix, Outcome 36 'Formal' induction of labour (not prespecified).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alcoseba‐Lim 1992.

| Methods | Method of randomisation and concealment of allocation not described. | |

| Participants | Women at 38 weeks of gestation, with dates determined by last menstrual periods, fundal height and ultrasound performed before 26 weeks. Exclusions: malpresentations, previous LSCS, vaginal bleeding, uncertain gestational age. | |

| Interventions | Weekly sweeping of membranes; for women with a closed cervix, digital stretching of the cervix was performed. In the control group, weekly cervical assessment by Bishop score was performed. | |

| Outcomes | Delivery within 7 days, delivery after 40 and after 41 weeks, operative delivery, neonatal morbidity (chorioamnionitis and meconium staining). Data on spotting, pain and oligohydramnios are reported for the sweeping of membranes group, but not for the control group. | |

| Notes | Author contacted, no reply. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Allott 1993.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence; sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Pregnant women beyond 40 weeks of gestation. Exclusion: women with a closed cervix. | |

| Interventions | Sweeping of membranes or Bishop's score performed by the principal investigator. | |

| Outcomes | Delay before onset of spontaneous labour (number of women starting spontaneous labour reported for every day between day 1 to day 7 after randomisation); overall and stratified by gravidity (primi vs multi), and by Bishop's score (< or = 6 vs > 6); formal induction of labour; mode of delivery; analgesia; mean duration of labour; precipitate labour (< 2 hours); pyrexia and use of antibiotics; Apgar score < 6 at 1 and 5 minutes; neonatal infection and use of antibiotics. | |

| Notes | Number of cesarean sections unclear. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Berghella 1994.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence; code contained in opaque sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Low risk pregnant women at 38 weeks of pregnancy; gestational age assessed by dates, and pelvic examination before 12 weeks or ultrasound scanning before 20 weeks; exclusion criteria were: placenta praevia, multiple pregnancy, non‐vertex, fetal growth restriction, or any medical complication. Women with long, closed cervices were excluded, apparently after randomisation. | |

| Interventions | Weekly stripping of membranes or weekly gentle vaginal examination for Bishop's score. | |

| Outcomes | Delivery at 41 weeks or more; delivery after 42 weeks; mode of delivery; mean delay until delivery. | |

| Notes | Contact for excluded women. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Boulvain 1998.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Concealment of allocation by consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes, opened by the delivery room nurse during a telephone call with the obstetrician. Randomly permutated blocks of 6 and 8, stratified by hospital (3 participating hospitals and 29 obstetricians). | |

| Participants | Women for whom non‐urgent induction of labour was medically indicated. A date for formal induction of labour was given prior to randomisation, at least 3 days and not later than one week after inclusion. | |

| Interventions | Intervention arm: sweeping of membranes. If not possible, the cervix was either dilated by the examining finger, or a cervical 'massage' was performed. Control arm: cervical assessment by Bishop score. | |

| Outcomes | Formal induction of labour; delay before spontaneous labour onset; maternal discomfort; bleeding; other side‐effects during or after the procedure; caesarean section; forceps/vacuum; requirement for analgesia during labour; neonatal morbidity. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cammu 1996.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Concealment of allocation by consecutively numbered, sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Nulliparous women at 39 weeks of gestation. Low‐risk, cephalic presentation, single fetus. | |

| Interventions | Weekly sweeping of the membranes or weekly gentle cervical examination with Bishop scoring. | |

| Outcomes | Continuation of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks, not delivered within 1 week, requirement for labour induction by other methods, caesarean section, premature rupture of membranes, low Apgar score and low cord blood pH. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Crane 1997.

| Methods | Random allocation derived from a table of numbers in blocks of 6; stratified by cervical status (opened or closed); code contained in opaque, sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes. | |

| Participants | Low‐risk women, at 38‐40 weeks (based on dates, or early ultrasound). | |

| Interventions | Sweeping of membranes or rubbing of the cervix if cervix was closed in the intervention group; cervical assessment by Bishop score only in controls. | |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous labour within one week, spontaneous labour before 41 weeks, overall spontaneous labour, mode of delivery, PROM, analgesia, maternal infection, Apgar score, neonatal infection. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Dare 2002.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Concealment of allocation by consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. | |

| Participants | Pregnant women at 38 weeks, with gestational age ascertained by sonography. Women with closed cervix were not included. | |

| Interventions | Membranes stripping or gentle cervical examination, performed by one clinician | |

| Outcomes | Continuation of pregnancy beyond 41 weeks, discomfort during the procedure, caesarean section, premature rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, Apgar score <7 at 5', admission to NICU, neonatal death. | |

| Notes | 9 women lost to follow‐up and 12 excluded (postrandomisation?) because of closed cervix. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Doany 1997.

| Methods | Random allocation derived from a table of random numbers. Method of concealment not described. | |

| Participants | Women at or beyond 287 days of gestation, with a single fetus in cephalic presentation. Weight between 2500 g and 4500 g, AFI between 5 and 25 cm, reactive NST and uterine contractions less than one per 5 minutes. Exclusion: absent prenatal care, previous uterine surgery, medical or psychiatric illness or drug use. | |

| Interventions | Four groups: 1 No sweeping and placebo gel. 2 No sweeping and PGE2 gel. 3 Sweeping and placebo gel. 4 Sweeping and PGE2 gel. | |

| Outcomes | Interval from admission to delivery. Cesarean section and instrumental delivery, induction of labour, oxytocin augmentation, epidural analgesia, number of visits. Apgar score, admission at neonatal intensive care unit, meconium stained liquor. | |

| Notes | Unequal number of women in the four groups, reasons not explained in the methods section. Exclusions after randomisation because of missing data (delivery outside the hospital): 7 women (0/28, 3/40, 1/51, 3/31 in groups 1 to 4, respectively). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

El‐Torkey 1992.

| Methods | Random allocation; random permutated blocks; opaque sealed envelopes kept in the antenatal clinic. | |

| Participants | Pregnant women with prolonged pregnancy, preferring induction of labour instead of biophysical assessment of the fetus. Deadline date for labour induction given after randomisation. | |

| Interventions | Sweeping of the membranes performed by the principal investigator or no vaginal examination. | |

| Outcomes | Spontaneous labour; cervix > 4 cm at first examination after admission to hospital in labour; maternal infection and use of antibiotics; analgesia during labour; mode of delivery; Apgar score < 6 at 1 minute and 5 minutes; neonatal infection; perinatal death. | |

| Notes | Recruitment terminated before completed sample size. Multiple assessments of the statistical significance of main outcome, probably. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Goldenberg 1996.

| Methods | Computerised random allocation. | |

| Participants | Low risk women at >= 38 weeks with dates ascertained by last menses, ultrasound examination and absence of uterine size/dates discrepancy. | |

| Interventions | Stretching of the cervix and membrane stripping versus Bishop scoring. Stretching/stripping was performed by one of two authors. | |

| Outcomes | Delay before labour onset, defined as a cervical dilatation >= 3 cm on admission, or membrane rupture with contractions. Dysfunctional contractions, premature rupture of membranes, mode of delivery, maternal febrile morbidity. | |

| Notes | 9 excluded because of their request to halt the procedure. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gupta 1998.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Concealment of allocation by sealed envelopes opened after entry into the trial. | |

| Participants | Low‐risk nulliparous women at 38 weeks (dates confirmed in early gestation) with an open cervix. Absence of infection, placenta praevia, PROM, cephalopelvic disproportion. | |

| Interventions | Membrane sweeping or gentle vaginal examination performed by the same physician. | |

| Outcomes | Main endpoint: spontaneous labour before or at 40 completed weeks (< 41 weeks or 287 days). Other: labour induction, spontaneous labour within 48 hours and 7 days, PROM, mode of delivery, vaginal cultures. | |

| Notes | > 40 completed weeks was interpreted as > 286 days of gestation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Magann 1998a.

| Methods | Random allocation. Method of concealment not described. | |

| Participants | Women with uncomplicated pregnancies, with an unfavourable cervix and a negative fetal fibronectin test at 39 weeks. | |

| Interventions | Sweeping every 3 days or vaginal examination every 3 days. | |

| Outcomes | Induction of labour at 42 weeks. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Magann 1998b.

| Methods | Random allocation derived from a table of random numbers. Concealment of allocation by consecutively numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | Women at or beyond 287 days of gestation, with intact membranes and a Bishop score < 5. Exclusion: placenta praevia. | |

| Interventions | Daily sweeping, daily intracervical PGE2 0.5 mg or daily vaginal examination. | |

| Outcomes | Induction of labour for continuing pregnancy beyond 42 weeks, caesarean section, instrumental delivery, Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes, admission to neonatal intensive care unit, PROM. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Magann 1999.

| Methods | Random allocation derived from a table of random numbers. Concealment of allocation by sealed, opaque envelopes. | |

| Participants | Women at or beyond 287 days of gestation, with intact membranes, single fetus in vertex presentation and a Bishop score < 5. | |

| Interventions | Daily sweeping or daily intravaginal insert releasing 0.3 mg per hour of PGE2 over 12 hours. | |

| Outcomes | Mean interval from admission to delivery, Bishop score on admission, labour induction at 42 weeks, mode of delivery, Apgar score, cord pH, admission to NICU. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

McColgin 1990a.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Method of concealment not described. | |

| Participants | Pregnant women at 38 weeks, with gestational age ascertained by menstrual dates, early examination, and sonography before 20 weeks. Women with closed cervix were included. | |

| Interventions | Weekly stripping of membranes (or stretching of the cervix then stripping if cervix was closed) or weekly pelvic examination for cervical assessment. | |

| Outcomes | Mean delay to delivery; delivery within 1 week; delivery at or beyond 42 weeks. | |

| Notes | Same women as McColgin 1990b? | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

McColgin 1990b.

| Methods | Random allocation based on a computer generated sequence. Method of concealment not described. | |