Abstract

PURPOSE

Case management (CM) interventions are effective for frequent users of health care services, but little is known about which intervention characteristics lead to positive outcomes. We sought to identify characteristics of CM that yield positive outcomes among frequent users with chronic disease in primary care.

METHODS

For this systematic review of both quantitative and qualitative studies, we searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO (1996 to September 2017) and included articles meeting the following criteria: (1)population: adult frequent users with chronic disease, (2)intervention: CM in a primary care setting with a postintervention evaluation, and (3)primary outcomes: integration of services, health care system use, cost, and patient outcome measures. Independent reviewers screened abstracts, read full texts, appraised methodologic quality (Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool), and extracted data from the included studies. Sufficient and necessary CM intervention characteristics were identified using configurational comparative methods.

RESULTS

Of the 10,687 records retrieved, 20 studies were included; 17 quantitative, 2 qualitative, and 1 mixed methods study. Analyses revealed that it is necessary to identify patients most likely to benefit from a CM intervention for CM to produce positive outcomes. High-intensity intervention or the presence of a multidisciplinary/interorganizational care plan was also associated with positive outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Policy makers and clinicians should focus on their case-finding processes because this is the essential characteristic of CM effectiveness. In addition, value should be placed on high-intensity CM interventions and developing care plans with multiple types of care providers to help improve patient outcomes.

Key words: case management, frequent users, primary health care, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

In developed countries, the bulk of health care system expenses is attributable to a small proportion of the population. Specifically, frequent users of health care services account for approximately 10% of the population but upward of 70% of health care expenditures.1–3 Many frequent users have chronic physical diseases that are further complicated by mental health comorbidities and/or social vulnerabilities, which increase their overall health care needs.4,5 These individuals are more likely to experience fragmentation of care,6,7 suffer from disability,8 and have a general decrease in quality of life9 and an increased risk of death.10,11

A variety of interventions have been developed to improve the health and social care of frequent users, the most common of which are case management (CM), individualized care plans, patient education and counseling, problem solving, and information sharing.12–17 Case management is a promising and effective intervention to improve the health and social care of frequent users12–17; it is a collaborative approach to ensure, coordinate, and integrate care and services for patients, in which a case manager evaluates, plans, implements, coordinates, and prioritizes services on the basis of patients’ needs in close collaboration with other health care providers.18

Many literature reviews have reported the effectiveness of CM interventions, citing such benefits as reductions in emergency department (ED)visits and hospital admissions, overall reductions in expenditures, and improved patient outcomes such as quality of life and patient satisfaction.12–15,19,20 However, CM is a complex intervention, with various characteristics interacting in a nonlinear manner.21,22 To design and implement effective CM interventions, we need to understand the characteristics of CM that are associated with positive outcomes. The objective of the present study was to conduct a systematic review to identify characteristics of CM that yield positive outcomes among adult frequent users with chronic disease in primary care.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies, with a data-based convergent synthesis design.23 This type of design, combining the strengths of quantitative and qualitative research, helps to develop a rich and deep understanding of complex health interventions.23,24 Our complete methods are detailed in a peer-reviewed systematic review protocol that is registered on PROS-PERO (CRD42016048006).25

Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1)population: adult frequent users (aged ≥18 years)with physical chronic disease and receiving care in primary, secondary, tertiary, or community care settings, (2)intervention: CM in a primary care setting (including ED)with a postintervention evaluation, and (3)primary outcomes: integration of services, health care system use, financial cost, and patient outcomes (eg, self-management, patient experience of care, health-related quality of life, etc). To increase homogeneity of the sample of included studies and comparability of CM characteristics between studies, pediatric, frail elderly, and homeless populations were excluded because these populations might have distinct sets of needs. In addition, specific disease-oriented CM interventions were excluded because primary care aims to improve whole-person health.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

A bibliographic database search was conducted of the online databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO for empirical studies (experimental, quasi-experimental, qualitative, and mixed methods studies)published in English or French and limited to the past ~20 years (ie, 1996 to September 2017). An information specialist for Cochrane Canada Francophone developed and ran specific search strategies for each database, combining the search concepts “frequent use” and “evaluation studies.” The MEDLINE search strategy is presented in Supplemental Appendix 1 (http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448/suppl/DC1/). Relevant studies were identified via a hand search of the reference lists of studies selected via the electronic search to be included in the review. To capture more information on CM interventions, companion documents (eg, protocols, reports, website pages, news articles) for each included study were retrieved by searching Google, ResearchGate, Scopus, and PubMed, as well as e-mailing the corresponding authors.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Four reviewers participated in the study selection using Covidence systematic review software. Two independent reviewers (L.L., M-J.C; see acknowledgment in end copy for reviewers listed in this section) screened titles and abstracts using the eligibility criteria, and 2 other independent reviewers (M.S., V.G.) assessed full texts of the selected studies for eligibility. At both stages, discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (M.L.). Eligible studies were retained for data extraction and methodologic quality assessment. Two reviewers extracted the following data using a standardized data extraction form: study characteristics (eg, first author, year of publication, country, setting, design); definition of frequent users; population characteristics such as age and sex; sample size; type, objective, frequency, and content of intervention; length of intervention sessions; duration of patient follow-up; case-finding process; health care providers involved; intervention offered to control group; data analysis; outcome characteristics and assessment instruments; and intervention effectiveness according to reported outcomes (quantitative or qualitative). Data extraction was double-checked by a second reviewer.

Quality Appraisal and Data Synthesis

Two independent reviewers used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)26–29 to assess eligible studies and determine an overall methodologic quality score for each. When necessary, disagreements between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer. The MMAT was specifically designed to concomitantly appraise studies with diverse designs and has been validated and reliability tested.26–29 We used the 2011 version of the MMAT, which includes 2 initial screening questions and 19 items. Studies that did not meet the 2 initial screening questions were deemed not empirical and were excluded. We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of methodologic quality on the results by replicating the analysis without the low-quality studies (MMAT score ≤25%).30 The MMAT has recently been updated and revalidated using a conceptual framework on the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies included in mixed studies reviews31; qualitative research32 with MMAT users worldwide; and a Delphi study with international experts.33 This led to the 2018 version of the MMAT.34 We used the original version for the present study.

Sufficient and necessary characteristics of CM interventions were identified using configurational comparative methods (CCM) 35; this is used to study a small to intermediate number of cases (eg, 5-50), among which an outcome of interest has been identified,36 allowing for the integration of quantitative and qualitative results.23 The use of CCM helps to identify configurations, that is, a combination of conditions that produces the presence or absence of the outcome of interest across cases. This allows for reduction of the complexity of data sets in small N situations by using Boolean algebra37 to explore different combinations of conditions and to identify necessary and sufficient conditions associated with the outcome of interest. A necessary condition is one that is always present when the outcome occurs, that is, the outcome cannot occur without this condition. A condition (or combination of conditions)is considered sufficient to produce an outcome if the outcome always occurs when the condition (or combination of conditions)is present.38 In the present study, the characteristics of CM interventions were the conditions we explored. Supplemental Appendix 2 (http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448/suppl/DC1/)provides definitions of CCM terms.

The CCM followed the 6 steps described by Rihoux and Ragin35 (a complete description of each step is detailed in Supplemental Appendix 3, http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448/suppl/DC1/): (1)building a raw data table, (2)constructing a truth table, (3)resolving contradictory configurations, (4)conducting Boolean minimization using fuzzy set/qualitative comparative analysis (fs/QCA)software, (5)bringing in the logical remainders cases (TOS-MANA software was used to create a visual representation of our results), and (6)interpreting the results. Following best practices in CCM, the selection of conditions used in the analysis, and the way each condition was defined, was informed by case-based knowledge (data extraction)and CM theory.38 The number of conditions was limited so that the ratio between the number of possible logical combinations of conditions and the number of cases was kept sufficiently low.37,39 For example, for the thematic synthesis step of the present review, we identified main characteristics of CM interventions in the included studies (Table 1). Of those, we identified 4 initial conditions that were most commonly reported in the included studies (informed by the team’s experience with CM and prior research on CM for frequent users). The definitions of these conditions were developed iteratively by drawing from prior research, going back to the cases to explore how they were defined, and drawing on the substantive and field knowledge of the team members. One condition (effective communication between health care providers) was removed because it was not reported or we were not able to conclude its absence/presence across all cases. Finally, the definitions of the 3 remaining main conditions were used to develop a codebook that was independently tested for clarity and comprehensiveness by reviewers outside the team. The final list of conditions and outcomes is presented in Supplemental Appendix 4 (http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/4/448/suppl/DC1/).

Table 1.

Description of Included Studies

| First Author, Year, (Country) | Design | Setting | Population (CM Intervention Inclusion Criteria) | N | Main Characteristics of the Intervention | Outcom | Methodological Quality Score, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam et al,40 2010 (USA) | Nonrandomized trial | Primary care clinic | >8 clinic visits/year with multiple comorbidities (physical, psychiatric and psychosocial issues) | I: 12 C: 8 |

Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referral to mental health services, review of medication, and care coordination. The PCP presented the care plan to the patient and amended it if needed. | ↓ Clinic visits ↑ Well-being ↑ Patient satisfaction ↑ Quality of care ↑ No show or cancelled appointments No change in hospital admission and ED use |

100 |

| Bodenmann et al,41 2017 (Switzerland) | Randomized controlled trial | ED | >5 ED visits/year | I: 125 C: 125 |

Interdisciplinary mobile team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include assistance for financial entitlements, education, housing, health insurance, and domestic violence support, as well as referral to mental health services, substance abuse treatment, or a PCP. Team also provided care coordination, counseling on substance abuse (if needed) and use of medical services. They also facilitated communication between health care team members. | No significant changes in ED visits | 75 |

| Brown et al,42 2005 (USA) | Before-after study | Primary care clinic | >1 hospital admission/year, >1 chronic condition, and life expectancy judged to be greater than 3 years | 17 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referral for diagnostic testing or specialists' services and a review of medication. The team also provided care coordination, psychological support, self-management support, and disease management. | ↓ ED visits ↓ Hospital admissions ↓ Length of stay No change in health care costs |

25 |

| Crane et al,43 2012 (USA) | Nonrandomized trial | ED | >6 ED visits/year; low family income | I: 34 C: 36 |

Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referral for diagnostic testing or specialists' services and review of medication. The team also provided group and individual medical appointments, telephone access to care manager, and group sessions on life-skills support. | ↓ ED visits ↓ ED and inpatient costs ↑ Employment status |

75 |

| Edgren et al,44 2016 (Sweden) | Randomized controlled trial | ED | >3 ED visits/6 months, deemed at risk of high health care use and considered to be receptive to intervention | I: 8,214 C: 3,967 |

Nurse case manager developed, with patient, a care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include self-management support, patient education, and referrals to other health and social services. Via regular contact by telephone, case manager provided self-management support to patient. They also facilitated communication and supported interactions with health care providers and social services. | ↓ Outpatient care ↓ Inpatient care ↓ ED visits ↓ Health care costs |

25 |

| Grimmer-Somers et al,45 2010 (Australia) | Mixed methods study | Primary care centers | Vulnerable frequent users | Quant: 37 Qual: Unknown |

Interdisciplinary care team developed, with patient, care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to other health and social services, self-management support, patient education, goal setting, and involvement in peer-led community group. The team also provided support for language, literacy, social support, and transport barriers. | ↓ ED use ↓ Hospital admissions ↓ Length of stay ↓ Inpatient cost ↓ Outpatient attendance ↓ Patient reflection on their health and other needs ↑ Patient goal-setting |

50 |

| Grinberg et al,46 2016(USA) | Qualitative study | Transitional primary care-postdischarge | >2 hospital admissions/6 months with at least 3 of the following criteria:>2 chronic conditions; >5 outpatient medications; lack of access to health care services; lack of social support; mental health comorbidity; substance abuse or use; homeless | 30 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include access to primary care, review of medication, medical appointment accompaniment, assistance for transport, and financial entitlements. The team also provided care coordination and health navigation after hospital discharge. | ↑ Patient motivation ↑ Self-management ↑ Healing relationships |

100 |

| Grover et al,47 2010 (USA) | Before-after study | ED | >5 ED visits/month or concern about ED use raised by staff or identified by California prescription-monitoring program | 85 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to outpatient and social services as well as restriction of narcotics prescriptions. Patients received letters to inform them of the care plan but had no contact with the team. The care plan was entered in the patient's medical records in the ED for easy access to information by the ED staff. | ↓ ED use ↓ Radiation exposure from diagnostic imaging ↑ Efficacy of referral No change in hospital admissions or most common chief complaint |

75 |

| Hudon et al,48 2015 (Canada) | Qualitative study | Primary care clinics | >3 ED visits and/or hospital admissions/year, >1 chronic condition, and identified by family physician as a frequent user likely to benefit from intervention | 25 patients 8 family members |

Nurse case manager developed, with patient and other health care providers, a care plan based on patient's evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to health and social services and interdisciplinary team meetings (including the patient). The case manager also provided self-management support and care coordination. | ↑ Access to care ↑ Communication ↑ Care coordination ↑ Patient involvement in decision-making ↑ Care transition |

50 |

| McCarty et al,49 2015 (USA) | Before-after study | ED | ≥25 ED visits/year or identified by ED staff as frequent user likely to benefit from intervention | 23 | Interdisciplinary care team developed, with patient, a care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to health care and social services, goal setting, crisis intervention, restriction of narcotic prescriptions, assistance for transport, financial entitlements, and housing. The team also provided care coordination and supported interactions with community services. | ↓ ED visits | 50 |

| Peddie et al,50 2011 (New Zealand) | Nonrandomized trial | ED | ≥10 ED visits/year | I: 87 C: 77 |

Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. The care plan could include referrals to a PCP and interdisciplinary team meeting (including the patient). | No change in ED visits | 25 |

| Pope et al,51 2000 (Canada) | Before-after study | ED | Frequent users who had the potential for high ED use, with at least 2 of the following criteria: chronic condition, complex medical condition, substance abuse user, violent behavior or abusive behavior | 24 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to health care and social services, restriction of narcotic prescriptions, restriction of ED use, limited interaction with ED staff, and escort by a security guard in the ED. The team also provided counseling and supported interactions with community services. | ↓ ED visits | 25 |

| Reinius et al,52 2013 (Sweden) | Randomized controlled trial | ED | ≥3 ED visits/6 months with the ability to participate in the study based on medical history, number of medications prescribed, and social factors | I: 211 C: 57 |

Same intervention as Edgren et al (2016)44 | ↓ Outpatient care ↓ ED visits ↓ Length of stay ↓ Health care costs ↑ Health status ↑ Patient satisfaction No change in inpatient care, hospital admissions, or mortality |

50 |

| Roberts et al,53 2015 (USA) | Before-after study | Transitional primary care – post discharge | ≥2 hospital admissions/6 months or ≥3 hospital admissions/year with ≥1 chronic condition | 198 | Interdisciplinary care team developed, with patient, care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include goal setting, review of medication, assistance for transport, financial entitlements, and housing. The team also provided self-management support, patient education, health navigation, and care coordination. | ↓ ED visits ↓ Hospital admission ↓ Health care costs |

75 |

| Shah et al,54 2011 (USA) | Nonrandomized trial | Primary care center | ≥4 ED visits or hospital admissions or ≥3 hospital admissions or ≥2 hospital admissions and 1 ED visit/ year, with low family income, uninsured, and not eligible for public health insurance program | I: 98 C: 160 |

Case manager developed, with patient, care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to health and social services, goal setting, assistance for transport, financial entitlements, and housing. The case manager also provided care navigation, facilitated communication with health care providers, supported interactions with community services, and provided care transition. | ↓ ED visits ↓ Health care cost No change in hospital admissions or length of stay |

50 |

| Skinner et al,55 2009 (UK) | Before-after study | ED | ≥10 ED visits/6 months or identified by senior health care providers as putting a high demand on unscheduled care services (or at future risk) and who could benefit from intervention | 57 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. The care plan could include referrals to health care services. | ↓ ED visits | 75 |

| Sledge et al,56 2006 (USA) | Randomized controlled trial | Primary care center | ≥2 hospital admissions/year | I: 47 C: 49 |

Same intervention as Brown et al (2005)42 | ↑ Clinic visits No change in health care use or costs, functional status, patient satisfaction, or medication taking adherence. |

50 |

| Spillane et al,57 1997 (USA) | Randomized controlled trial | ED | ≥10 ED visits/year | I: 27 C: 25 |

Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include care recommendation and treatment guidelines for ED staff such as limitation of diagnostic tests and restriction of narcotics prescriptions. The team also provided psychosocial services, care coordination, and liaison with a PCP. | No change in ED visits | 75 |

| Stokes-Buzzelli et al,58 2010 (USA) | Before-after study | ED | Top 100 frequent ED users, or identified as frequent users deemed appropriate for intervention | 36 | Interdisciplinary care team developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. The care plan could include care suggestions and treatment guidelines (eg, restriction of narcotics prescriptions) for ED staff. | ↓ ED visits ↓ ED contact time ↓ Laboratory tests ordered ↓ ED costs |

75 |

| Weerahandi et al,59 2015 (USA) | Nonrandomized trial | Transitional primary care – postdischarge | ≥1 hospital admission/1 month or 2 hospital admissions/6 months | I: 579 C: 579 |

Social worker case manager, with patient and other health care providers, developed care plan based on patient’s evaluation. Care plan could include referrals to health care and social services, counseling for mental health problems, self-management support, patient activation, assistance with insurance, and medical appointment accompaniment. The case manager also provided care coordination and care transition and facilitated communication between health care providers. | No change in hospital admissions | 50 |

C = control group; CM = case management; ED = emergency department; I = intervention group; PCP = primary care provider; Qual = qualitative study; Quant = quantitative study; UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America.

RESULTS

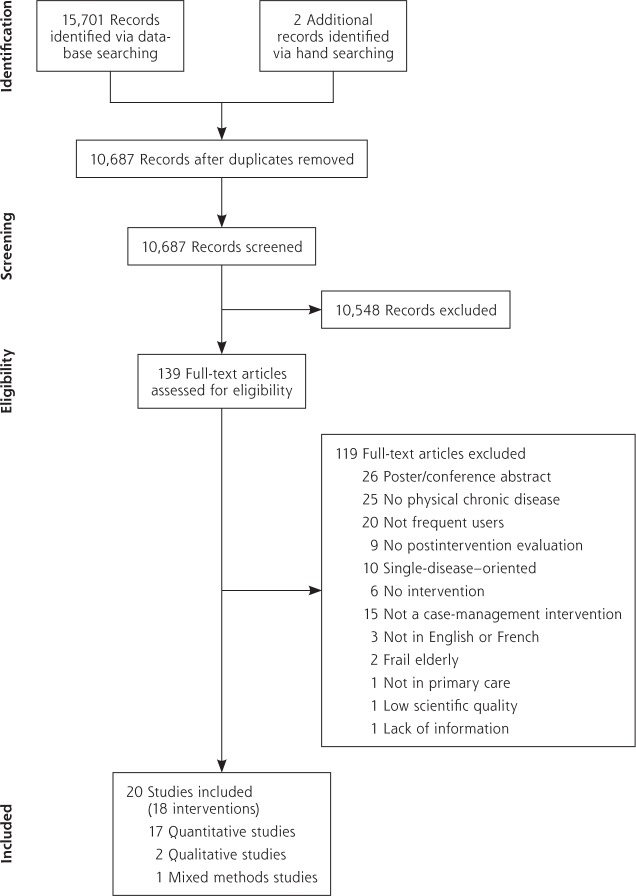

We identified 10,687 unique records, of which 10,548 did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among the 139 full-text articles selected, 117 were excluded based on the inclusion criteria, 1 was excluded because it did not meet the 2 initial MMAT screening questions,60 and another was excluded from the CCM analysis, owing to lack of information about the conditions (characteristics)of CM intervention in the documents.61 Thus, 20 studies (18 CM interventions)were included in the synthesis. Table 1 presents a description of these studies. Seventeen were quantitative (7 before-after studies, 5 nonrandomized controlled trials, and 5 randomized controlled trials), 2 were qualitative, and 1 was a mixed methods study. Twelve were conducted in United States, 2 each in Sweden and Canada, and 1 each in Switzerland, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. The studies included 17 to 12,181 participants, with a mean age range of 20 to 66 years. The proportion of men varied from 23% to 75%. All of the studies included development and implementation of a care plan, 15 involved an interdisciplinary team,40–43,45–47,49–51,53,55–58 and 11 were conducted in an ED setting.41,43,44,47,49–52,55,57,58

Figure 1.

Study selection process.

For the majority of studies (n = 17), CM intervention participants were identified using a threshold of number of health care visits.40–44,46–50,52–57,59 To determine eligibility, 9 studies required patients be evaluated by a health care provider to assess their likelihood of benefiting from the CM intervention.42,44,47–49,51,52,55,58 Ten studies included patients with a complex/vulnerable situation such as the presence of physical, psychiatric, and/or psychosocial issues.40,42,43,45,46,48,51–54 The methodologic quality of the included studies ranged from 25% to 100% (median, 50%).

Fifteen studies reported positive outcomes such as health and functional status,52 patient satisfaction,40,52 self-management,45,46,48 ED42–45,47,49,51–55,58 and clinic visits,40,44,45,52 hospital admission42,44,45,53 and length of stay,42,45,52 and ED43,44,52–55,57,58 and inpatient cost.43,44,45,52–54 Regarding the conditions, 16 studies implemented a high-intensity CM intervent ion40–46,48,49,51–54,56,57,59 including at least 3 of the following criteria: caseload of fewer than 60 patients, ≥50% of the time spent face-to-face with the patient, initial assessment in person, and multidisciplinary team meetings or frequent contact with the patient. Fifteen studies identified patients who could benefit the most from the CM40,42–49,51–55,58 on the basis of their identification as frequent users (with no clear definition)with complex care needs or based on providers’ assessment that the CM intervention would be beneficial. Finally, 17 studies included a multidisciplinary/interorganizational care plan40–43,45–51,53,55–59 documenting patient needs and goals as well as the available resources to respond to patients’ needs and including at least 2 health care providers from disciplines other than the family physician or case manager.

Table 2 shows 5 configurations for which the case-finding condition was always present when a positive outcome occurred. In addition, the CCM revealed that the multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary care plan and the CM intensity conditions were often present when a positive outcome occurred. These results remained the same when we removed the studies with low methodologic quality.42,44,50,51 Supplemental Appendix 5 (http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448/suppl/DC1/)illustrates the relation between the conditions and the-outcomes based on the results presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Truth Table

| Case-Management Intensity | Case Finding | Multidisciplinary/Interdisciplinary Care Plan | Positive Outcome | No. of Cases | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | Adam et al,40 Brown et al,42 Crane et al,43 Grimmer-Somers et al,45 Grinberg et al,46 Hudon et al,48 McCarty et al,49 Pope et al,51 Roberts et al53 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Edgren et al,44 Reinius et al,52 Shah et al54 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Grover et al,47 Skinner et al,55 Stokes-Buzzelli et al58 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Bodenmann et al,41 Sledge et al,56 Spillane et al,57 |

| Weerahandi et al,59 | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Peddie et al50 |

The analysis revealed that the case-finding characteristic (ie, high frequency of health care visits)and complexity of health care needs are necessary to produce a positive outcome. Moreover, in our cases, positive outcomes were associated with the following 2 sufficient characteristics when each was combined with this necessary condition: high-intensity CM intervention and presence of a multidisciplinary/interorganizational care plan.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that CM should be offered to patients such as those who are uninsured, have a low income, or who a health care provider deems in need and who frequently use health care services and have complex health care needs. Such appropriate case finding should be combined with a high-intensity intervention and/or the presence of a multidisciplinary/interorganizational care plan.

Previous research,60,62–64 as well our prior thematic analysis review on key factors of CM interventions,65 have recognized the importance of appropriate patient identification. Previous studies, however, have defined the appropriateness of patient identification on the basis of patients’ risk of frequent health care use and associated cost to health care systems.63,66,67 In addition to these criteria, our present results recommend a case-finding process based also on patient complex care needs (eg, combination of physical, psychiatric, and social conditions; poverty, polymedication, lack of social support, or clinical judgment).68 A combination of quantitative (eg, prediction tools and thresholds)and qualitative (eg, clinical judgment)techniques might be the best approach to identify patients for whom CM interventions will likely be most beneficial.64

The association between high-intensity CM and its effectiveness has been examined in other populations. In a systematic mixed studies review exploring the relations between positive outcomes and barriers to CM implementation designed for patients with dementia and their caregivers in home care programs, high-intensity CM identified with CCM was shown to be a necessary and sufficient condition to produce positive clinical outcomes and to reduce health care use.69 Similar to our present results, the importance of small caseload, regular follow-up, and multidisciplinary team meetings was highlighted.69 In addition, reviews on the effect of CM in reducing hospital use,70 and on the effectiveness of interventions in reducing ED use,16 reported that regular in-person contacts with a case manager, a criterion for high-intensity CM, might contribute to positive patient outcomes. However, others62 have reported equivocal results regarding the effect of high-intensity CM for patients with complex care needs and highlighted that evidence from CM interventions remains unclear. This might explain why our present CCM analysis did not identify high-intensity CM intervention as a necessary condition to produce positive outcomes.

Multidisciplinary teams have been recognized as an important part of CM interventions,18 providing the opportunity to learn from each other and offering holistic and comprehensive care for patients with complex care needs.62–64,71,72 As the coordinator of the multidisciplinary team, the case manager must ensure that patients receive coordinated and integrated care processes that guarantee quality and cost effectiveness.63 To this end, the development and implementation of a care plan is a strategy used by the case manager and best suited to align the goals of the different health care services.63 Our present review suggests that a care plan provided by health care providers from different disciplines, combined with appropriate case finding, is a strategy that will more likely be effective and result in positive CM outcomes.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review aimed at identifying characteristics of CM interventions associated with positive outcomes. Whereas a meta-analysis of quantitative results would have led to an estimate of the magnitude of the effect of CM, it would not have revealed the characteristics that are necessary and sufficient to yield the effect size. The present review used an innovative method of data analysis, CCM, which allowed us to combine quantitative, qualitative, randomized, and uncontrolled study designs in a single analysis scheme to clarify how CM leads to positive outcomes. All steps of this systematic review were confirmed by at least 2 members of the team to ensure reproducibility of the results. In addition, the systematic review process lends credence to our results, as does our sensitivity analysis, which showed that the methodologic quality of the included studies did not affect the results.

Limitations

In the present review, all outcomes were considered equal and were not analyzed individually. Second, we considered all of the eligible CM intervention studies regardless of methodologic quality. The sensitivity analysis, however, indicated that the studies with low methodologic quality did not influence the results. Third, given that the majority of the studies were implemented at a single site, results might not be generalizable to multisite health care settings. Fourth, the present review did not address the knowledge gap concerning who should deliver CM or where. Fifth, even though frequent users are a primary target of case management research, the present review did not evaluate case management for individuals with complex health care needs who are not frequent users. Finally, the primary publications often did not include enough contextual information to make a broader consideration of context possible.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of our results, we recommend that policy makers and clinicians focus on their case-finding processes because these comprise the essential characteristic of effective CM. Moreover, value should be placed on high-intensity CM intervention (ie, small caseload, frequent face-to-face contact with the patient, initial assessment in person, and/or multidisciplinary team meetings) and developing care plans with multiple types of care providers to help improve patient outcomes. All policy makers and clinicians directly or indirectly involved in CM now or in the future should consider adapting their decisions or practices accordingly. Further research could address how different primary care settings (eg, ED vs clinic) influence CM outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Roxanne Lépine for the development of the search strategy, as well as Léa Langlois, Véronique Gauthier, Marie-Joelle Cossi, and Michele Schemilt for screening titles and abstracts, and Catherine Vandal and the Unité de Recherche Clinique et épidémiologique du CRCHUS for administrative support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448.

Author contributions: C.H. and M-C.C. conceived the review and participated in its design and coordination. F.L. and H.T.V.Z. coordinated the systematic review methods. P.P., R.S., and B.R. guided the methodologic steps of the configurational comparative methods. C.H., M-C.C., P.P., R.S., B.R., and M.L. participated in the synthesis of the data. M.L. conducted the data collection, and R.S. conducted the data analysis. M.L. drafted the manuscript under the guidance of C.H. and M-C.C. All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Funding support: This project was funded by the Quebec SPOR-SUPPORT Unit, one of the methodologic platforms of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR).73 Members of the Unit are coauthors and offered methodologic support to design and conduct this systematic mixed studies review. The governance structures of the Unit, however, had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication. All authors had full access to all of the data and are responsible for the decision to submit for publication.

PROSPERO registration: CRD42016048006

Supplemental materials: Available at http://www.AnnFamMed.org/content/17/5/448/suppl/DC1/.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Berry-Millett R. Follow the money—controlling expenditures by improving care for patients needing costly services. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(16): 1521-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010; 56(1): 42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wodchis WP. High cost users: driving value with a patient-centred health system. Presented at: Health Links and Beyond: the Long and Winding Road to Person-Centred Care; June 20, 2013; Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, McGee HM, Murray A, Bury G. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: a study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med. 2003; 41(3): 309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vedsted P, Christensen MB. Frequent attenders in general practice care: a literature review with special reference to methodological considerations. Public Health. 2005; 119(2): 118-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudon C, Sanche S, Haggerty JL. Personal characteristics and experience of primary care predicting frequent use of emergency department: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2016; 11(6): e0157489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsson M, Hansagi H. Repeated use of the emergency department: qualitative study of the patient’s perspective. Emerg Med J. 2001; 18(6): 430-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winefield HR, Turnbull DA, Seiboth C, Taplin JE. Evaluating a program of psychological interventions in primary health care: consumer distress, disability and service usage. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007; 31(3): 264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits FT, Brouwer HJ, ter Riet G, van Weert HC. Epidemiology of frequent attenders: a 3-year historic cohort study comparing attendance, morbidity and prescriptions of one-year and persistent frequent attenders. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuda KK, Immekus R. Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: a statewide analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006; 48(1): 9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansagi H, Allebeck P, Edhag O, Magnusson G. Frequency of emergency department attendances as a predictor of mortality: nine-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. J Public Health Med. 1990; 12(1): 39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2011; 58(1): 41-52.e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haroun D, Smits F, van Etten-Jamaludin F, Schene A, van Weert H, Ter Riet G. The effects of interventions on quality of life, morbidity and consultation frequency in frequent attenders in primary care: a systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016; 22(2): 71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moe J, Kirkland SW, Rawe E, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to decrease emergency department visits by adult frequent users: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2017; 24(1): 40-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soril LJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, Noseworthy TW, Clement FM. Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One. 2015; 10(4): e0123660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raven MC, Kushel M, Ko MJ, Penko J, Bindman AB. The effectiveness of emergency department visit reduction programs: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2016; 68(4): 467-483.e415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van den Heede K, Van de Voorde C. Interventions to reduce emergency department utilisation: a review of reviews. Health Policy. 2016; 120(12): 1337-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Case Management Network of Canada. Canadian Standards of Practice in Case Management. Ottawa, Canada: National Case Management Network of Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med. 2013; 44(3): 717-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smits FT, Wittkampf KA, Schene AH, Bindels PJ, Van Weert HC. Interventions on frequent attenders in primary care: a systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008; 26(2): 111-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013; 50(5): 587-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Aubrey-Bassler K, et al. Case management in primary care among frequent users of healthcare services with chronic conditions: protocol of a realist synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(9): e017701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017; 6(1): 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pluye P, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I. Opening-up the definition of systematic literature review: the plurality of worldviews, methodologies and methods for reviews and syntheses. J Clin Epidemiol.2016; 73: 2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Aubrey-Bassler K, et al. Effective interventions targeting frequent users of health care and social services with chronic conditions in primary care: a systematic mixed studies review. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016048006. Published Sep 2016; updated September 22, 2016; Accessed Mar 28, 2018.

- 26.Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health.2014; 35: 29-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49(1): 47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in Mixed Studies Reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 46(4): 529-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souto RQ, Khanassov V, Hong QN, Bush PL, Vedel I, Pluye P. Systematic mixed studies reviews: updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015; 52(1): 500-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999; 282(11): 1054-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong QN, Pluye P. A conceptual framework for critical appraisal in systematic mixed studies reviews. J Mixed Methods Res.2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong QN, Gonzalez-Reyes A, Pluye P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J Eval Clin Pract. 2018; 24(3): 459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT): a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol.2019; 111: 49-59.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong QN, Pluye P, Fabregues S, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018; 34(4): 285-291. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rihoux B, Ragin C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)and Related Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dy SM, Garg P, Nyberg D, et al. Critical pathway effectiveness: assessing the impact of patient, hospital care, and pathway characteristics using qualitative comparative analysis. Health Serv Res. 2005; 40(2): 499-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg-Schlosser D, De Meur G, Rihoux B, Ragin CC. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)as an Approach. In: Rihoux B, Ragin C, eds. Configurational Comparative Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009: 1-18. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rihoux B, Lobe B. The case for Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Adding Leverage for Thick Cross-Case Comparison. In: Byrne D, Ragin C, eds. The Sage Handbook of Case-Based Methods. London, England: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marx A, Dusa A. Crisp-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (csQCA), contradictions and consistency benchmarks for model specification. Methodol Innov Online. 2011; 6(2): 103-148. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adam P, Brandenburg DL, Bremer KL, Nordstrom DL. Effects of team care of frequent attenders on patients and physicians. Fam Syst Health. 2010; 28(3): 247-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenmann P, Velonaki VS, Griffin JL, et al. Case management may reduce emergency department frequent use in a universal health coverage system: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(5): 508-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, O’Connor P, Sledge WH. Primary intensive care: pilot study of a primary care-based intervention for high-utilizing patients. Dis Manag. 2005; 8(3): 169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crane S, Collins L, Hall J, Rochester D, Patch S. Reducing utilization by uninsured frequent users of the emergency department: combining case management and drop-in group medical appointments. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012; 25(2): 184-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgren G, Anderson J, Dolk A, et al. A case management intervention targeted to reduce healthcare consumption for frequent Emergency Department visitors: results from an adaptive randomized trial. Eur J Emerg Med. 2016; 23(5): 344-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimmer-Somers K, Johnston K, Somers E, Luker J, Alemao LA, Jones D. A holistic client-centred program for vulnerable frequent hospital attenders: cost efficiencies and changed practices. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010; 34(6): 609-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grinberg C, Hawthorne M, LaNoue M, Brenner J, Mautner D. The core of care management: the role of authentic relationships in caring for patients with frequent hospitalizations. Popul Health Manag. 2016; 19(4): 248-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grover CA, Close RJ, Villarreal K, Goldman LM. Emergency department frequent user: pilot study of intensive case management to reduce visits and computed tomography. West J Emerg Med. 2010; 11(4): 336-343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Diadiou F, Lambert M, Bouliane D. Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services with chronic diseases: a qualitative study of patient and family experience. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):523-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCarty RL, Zarn J, Fenn R, Collins RD. Frequent ED utilizers: a case management program to address patient needs. Nurs Manage. 2015; 46(9): 24-31; quiz 31-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peddie S, Richardson S, Salt L, Ardagh M. Frequent attenders at emergency departments: research regarding the utility of management plans fails to take into account the natural attrition of attendance. N Z Med J. 2011; 124(1331): 61-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pope D, Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, Etherington J. Frequent users of the emergency department: a program to improve care and reduce visits. CMAJ. 2000; 162(7): 1017-1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reinius P, Johansson M, Fjellner A, Werr J, Ohlén G, Edgren G. A telephone-based case-management intervention reduces healthcare utilization for frequent emergency department visitors. Eur J Emerg Med. 2013; 20(5): 327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roberts SR, Crigler J, Ramirez C, Sisco D, Early GL. Working with socially and medically complex patients: when care transitions are circular, overlapping, and continual rather than linear and finite. J Healthc Qual. 2015; 37(4): 245-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah R, Chen C, O’Rourke S, Lee M, Mohanty SA, Abraham J. Evaluation of care management for the uninsured. Med Care. 2011; 49(2): 166-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skinner J, Carter L, Haxton C. Case management of patients who frequently present to a Scottish emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009; 26(2): 103-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, et al. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Dis Manag. 2006; 9(6): 328-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spillane LL, Lumb EW, Cobaugh DJ, Wilcox SR, Clark JS, Schneider SM. Frequent users of the emergency department: can we intervene? Acad Emerg Med. 1997; 4(6): 574-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stokes-Buzzelli S, Peltzer-Jones JM, Martin GB, Ford MM, Weise A. Use of health information technology to manage frequently presenting emergency department patients. West J Emerg Med. 2010; 11(4): 348-353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weerahandi H, Basso Lipani M, Kalman J, et al. Effects of a psychosocial transitional care model on hospitalizations and cost of care for high utilizers. Soc Work Health Care. 2015; 54(6): 485-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dattalo M, Nothelle S, Tackett S, et al. Frontline account: targeting hot spotters in an internal medicine residency clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2014; 29(9): 1305-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Navratil-Strawn JL, Hawkins K, Wells TS, et al. An emergency room decision-support program that increased physician office visits, decreased emergency room visits, and saved money. Popul Health Manag. 2014; 17(5): 257-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bodenheimer TS, Berry-Millett R. Care Management of Patients With Complex Health Care Needs. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ross S, Curry N, Goodwin N. Case Management: What It Is and How It Can Best Be Implemented. London, UK: The King’s Funds; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2014; 19: 1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hudon C, Chouinard MC, Lambert M, Diadiou F, Bouliane D, Beau-din J. Key factors of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a thematic analysis review. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(10): e017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stokes J, Panagioti M, Alam R, Checkland K, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P. Effectiveness of case management for ‘at risk’ patients in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10(7): e0132340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Billings J, Dixon J, Mijanovich T, Wennberg D. Case finding for patients at risk of readmission to hospital: development of algorithm to identify high risk patients. BMJ. 2006; 333(7563): 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bodenmann P, Baggio S, Iglesias K, et al. Characterizing the vulnerability of frequent emergency department users by applying a conceptual framework: a controlled, cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2015; 14: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khanassov V, Vedel I, Pluye P. Barriers to implementation of case management for patients with dementia: a systematic mixed studies review. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):456-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Joo JY, Liu MF. Case management effectiveness in reducing hospital use: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev. 2017; 64(2): 296-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trella RS. A multidisciplinary approach to case management of frail, hospitalized older adults. J Nurs Adm. 1993; 23(2): 20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Stampa M, Vedel I, Trouvé H, Ankri J, Saint Jean O, Somme D. Multidisciplinary teams of case managers in the implementation of an innovative integrated services delivery for the elderly in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14: 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html. Accessed Apr 18, 2018.