A lysosome activator ameliorates muscular dystrophies.

Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a devastating disease caused by mutations in dystrophin that compromise sarcolemma integrity. Currently, there is no treatment for DMD. Mutations in transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (ML1), a lysosomal Ca2+ channel required for lysosomal exocytosis, produce a DMD-like phenotype. Here, we show that transgenic overexpression or pharmacological activation of ML1 in vivo facilitates sarcolemma repair and alleviates the dystrophic phenotypes in both skeletal and cardiac muscles of mdx mice (a mouse model of DMD). Hallmark dystrophic features of DMD, including myofiber necrosis, central nucleation, fibrosis, elevated serum creatine kinase levels, reduced muscle force, impaired motor ability, and dilated cardiomyopathies, were all ameliorated by increasing ML1 activity. ML1-dependent activation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) corrects lysosomal insufficiency to diminish muscle damage. Hence, targeting lysosomal Ca2+ channels may represent a promising approach to treat DMD and related muscle diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked inherited muscle disease (1), is caused by loss-of-function mutations affecting dystrophin, a large cytoplasmic protein that connects the cytoskeleton with extracellular matrix proteins via the muscle membrane (sarcolemma) (2, 3). The fragile sarcolemma that makes human DMD muscles prone to contraction-induced muscle damage is mimicked in the striated muscles of the mdx mouse, a murine model of DMD (4–6). Although gene therapy approaches, including CRISPR-Cas9 technology (7), have provided hope for potential treatment to some specific variants of DMD, the existence of thousands of DMD-causing dystrophin mutations remains a major challenge (1). To develop a therapeutic approach that would be more broadly applicable to all forms of DMD, it is necessary to understand the common pathological mechanisms underlying the condition (4).

Muscle cells are especially sensitive to membrane damage, and recent studies have identified impairment of membrane repair capability as an important cause of muscular dystrophies (8–10). For instance, we recently found that mice lacking transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1/MCOLN1; ML1), a lysosomal Ca2+ release channel required for lysosomal exocytosis (11, 12), display early-onset, progressive dystrophies similar to DMD (13). When ML1 is pharmacologically inhibited or genetically inactivated, membrane resealing is impaired in skeletal muscles (13). Hence, lysosomes may provide a major source of membranes for repairing damaged sarcolemma, and ML1 is essential for Ca2+-dependent delivery of lysosomal membranes (i.e., lysosomal exocytosis) to damaged sites (13). Studies of other muscle diseases have also connected lysosomal dysfunction with muscle pathogenesis (14).

In the current proof-of-concept study, we examined whether up-regulation of ML1, by genetic or pharmacological methods, is sufficient to increase lysosomal functions and sarcolemma repair. If so, ML1 may be a putative target for amelioration of muscle damage in vivo.

RESULTS

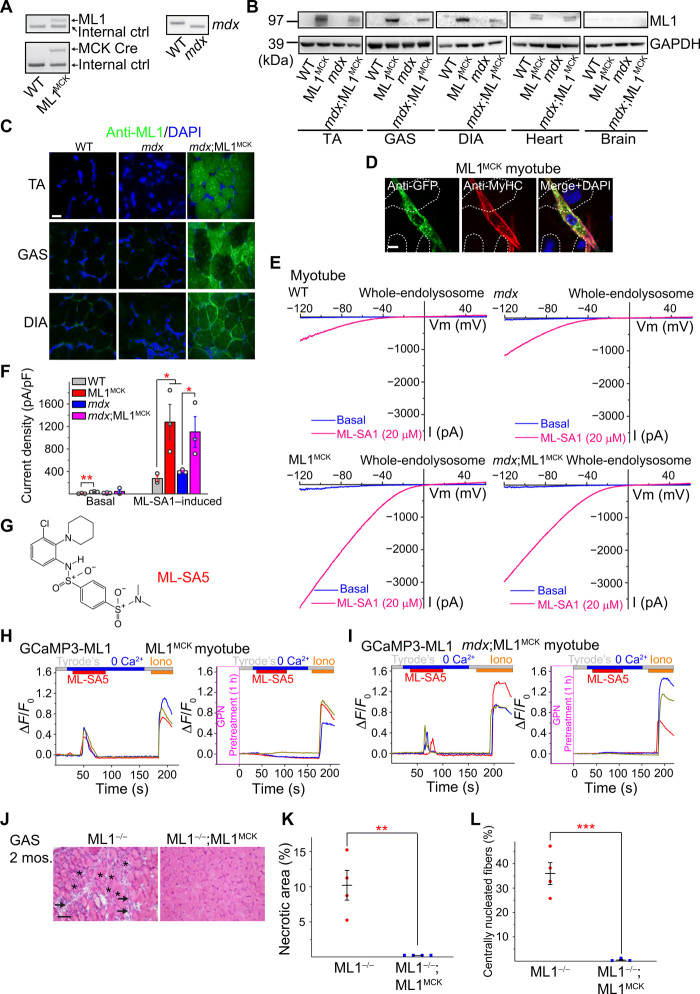

Transgenic overexpression of ML1 ameliorates muscular dystrophies in mdx mice

To achieve muscle-specific overexpression of ML1 in vivo, we crossed a mouse line carrying a GCaMP3-ML1 transgene (ML1 ROSA-lSl) (15) with a Cre line driven by the muscle-specific creatine kinase (CK) promoter (MCK-Cre) (16). The resultant ML1 ROSA-lSl;MCK-Cre (abbreviated as ML1MCK) progeny were then crossed with mdx mice with a loss-of-function dystrophin mutation (17) to generate mdx;ML1MCK mice (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A). Western blotting and immunofluorescence analyses with anti-ML1 antibody revealed ML1 overexpression in both skeletal and cardiac muscle tissues of the mdx;ML1MCK mice; isolated primary myotubes were ML1 immunopositive, whereas nonmuscle tissues showed barely detectable immunoreactivity (Fig. 1, B to D, and fig. S1, B and C).

Fig. 1. Muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of ML1.

(A) PCR genotyping of the mdx mutation, GCaMP3-ML1 transgene, and MCK-Cre. (B) Western blotting with anti-ML1 antibody in brain and various skeletal muscle tissues, including GAS, TA, and DIA from WT, ML1 ROSA-lSl;MCK Cre (ML1MCK), mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice (see fig. S1B for the source files). GAPDH served as the loading control. Note that MCK-Cre is selectively expressed in differentiated myotubes (16), and its expression in the muscle tissue might be affected by the degree of dystrophies. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of TA, GAS, and DIA cryosections from various transgenic mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of primary myotubes isolated from ML1MCK mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Whole-endolysosome ML1 currents (IML1) were activated by ML-SA1 (20 μM), a synthetic agonist of ML1, in primary myotubes harvested from WT, ML1MCK, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice. Currents were stimulated with a ramp voltage protocol from −120 to +60 mV. Holding potential = 0 mV. (F) IML1 current densities of myotubes from (E). Each open circle represents one cell/patch. (G) Structure of ML-SA5. (H and I) ML-SA5–induced lysosomal Ca2+ release, measured with GCaMP3 imaging, in primary myotubes isolated from ML1MCK mice. GPN (glycyl-l-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide), a dipeptide causing osmotic lysis of lysosomes, was used as a negative (depleting lysosomal Ca2+ stores) control. (J) Representative images showing H&E staining of GAS isolated from 2-month-old ML1−/− and ML1−/−;ML1MCK mice. Arrows label necrotic areas, and asterisks show centrally nucleated myofibers. Scale bar, 100 μm. (K and L) Quantification of necrosis (K) and central nucleation (L) in GAS sections from 2-month-old ML1−/− and ML1−/−;ML1MCK mice. All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Whole-lysosomal ML1 currents, activated by TRPML-specific synthetic agonists (ML-SAs) (12, 15, 18), were 4 to 10 times larger in the ML1MCK myotubes than in wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 1, E and F). ML-SAs induced robust glycyl-l-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide–sensitive lysosomal Ca2+ release (15) in ML1MCK myotubes, suggesting that genetically overexpressed ML1 channels were functionally localized on the late endosomal and lysosomal membranes of muscle cells (Fig. 1, G to I, and fig. S1, D and E). Introducing ML1MCK into the ML1 knockout (KO) mice resulted in a complete rescue of the dystrophic phenotype, as manifested by the decreases in myofiber necrosis and central nucleation (Fig. 1, J to L) (13). Hence, the ML1MCK mice were considered suitable for investigating the in vivo effects of ML1 overexpression on striated muscles.

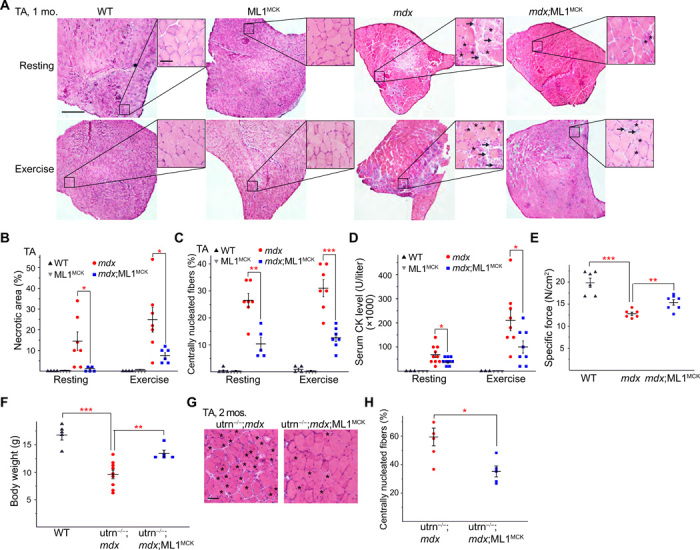

Mdx mice, either homozygous females or hemizygous males, exhibit early-onset muscular dystrophies, as evidenced by myofiber necrosis (myonecrosis) and degeneration/regeneration cycles, which were readily observed by postnatal day 14 (P14) (19). In 1-month-old mdx;ML1MCK mice, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed that myonecrosis, quantified by the percentage of the necrotic area (i.e., the presence of necrotic myofibers, immune cells, and fibroblasts) in whole cross sections, was markedly reduced in tibialis anterior (TA) muscles compared with age-matched mdx mice, especially after downhill treadmill exercise (Fig. 2, A and B). The number of centrally nucleated fibers, caused by repeated myocyte degeneration and regeneration, was also significantly reduced in the mdx;ML1MCK muscles (Fig. 2, A and C). Similar anti-dystrophic effects were seen in other skeletal muscles, including the gastrocnemius (GAS) and diaphragm (DIA) (fig. S2, A to G). Serum CK levels, a diagnostic biomarker of DMD (13), were also reduced by ML1 overexpression (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the histological and biochemical results, physiological assays showed improved specific muscle force in mdx mice following ML1MCK overexpression (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. Transgenic overexpression of ML1 reduces muscle pathologies in young mdx mice.

(A) H&E staining of TA sections from WT, ML1MCK, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 1 month, before (rest) and after treadmill exercise. Both male and female mice were randomly assigned into different groups. Arrows label necrotic areas and asterisks show centrally nucleated myofibers. Scale bar, 500 μm or 50 μm (zoom-in images). (B) Percentage of necrotic area in TA muscles from various transgenic mice. Each datum (n indicates the number of the muscle) represents the averaged result from at least five representative images randomly selected from at least three sections. Statistical analyses were performed by experimenters who were blind to animal genotypes. (C) Percentage of centrally nucleated fibers in TA muscles from different transgenic mice. (D) Serum CK levels in 1-month-old WT, ML1MCK, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice before and after treadmill exercise. (E) Specific force test of GAS from multiple 1-month-old mice. (F) Body weight measurements of WT, utrophin−/−;mdx (utrn−/−;mdx), and utrn−/−;mdx;ML1MCK male mice at the age of 1 month. (G) Effect of ML1 overexpression on histology of TA muscles isolated from 2-month-old utrn−/−;mdx mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (H) Quantification on central nucleation of muscle histology from (G). All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

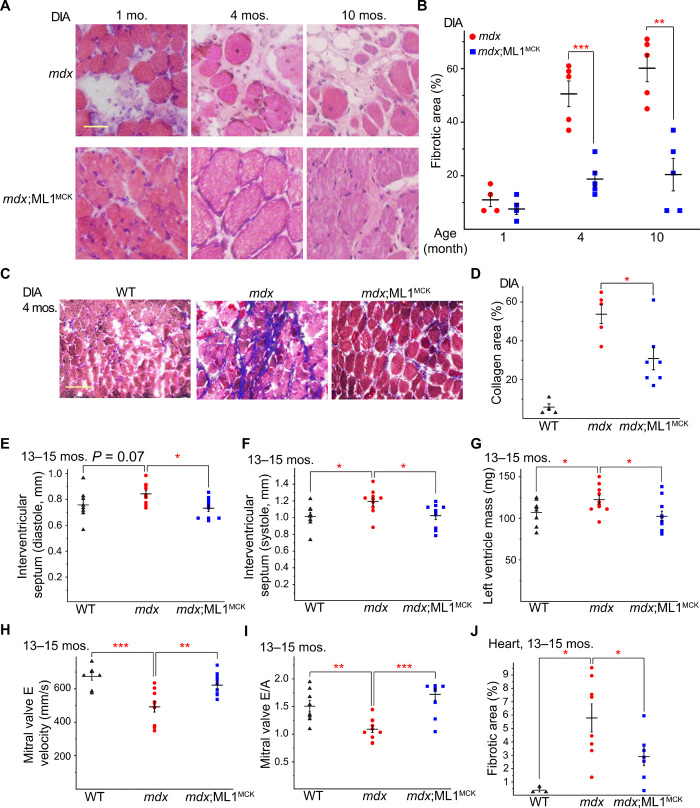

In most skeletal muscles of mdx mice, the dystrophic phenotype did not appear to be progressive, perhaps due to compensatory expression of utrophin, a functional homolog of dystrophin (20). Relative to mdx mice, utrophin−/−;mdx mice have a much more severe and progressive muscular dystrophy that resembled human DMD (20). Both dystrophy and body weight loss characteristic of the utrophin−/−;mdx phenotypes (20) were improved by ML1MCK overexpression (Fig. 2, F to H). Dystrophy of the DIA in mdx mice was also progressive, as seen in human DMD, and respiratory failure is a major cause of death in DMD (6). Consistent with previous studies (6), we observed massive necrosis and subsequent fibrous and adipose tissue replacement (i.e., fibrosis) in mdx DIA muscles (Fig. 3, A and B). At all ages examined (1, 4, and 10 months), fibrosis was reduced significantly by ML1MCK overexpression (Fig. 3, A and B). The content of collagen, a major component of fibrous scar tissue (13), was also decreased by ML1MCK overexpression (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3. Transgenic ML1 overexpression ameliorates myopathies in aged mdx mice.

(A) H&E staining of DIA isolated from mdx and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 1, 4, and 10 months. Both male and female mice were used in this experiment. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Age-dependent progressive fibrosis in DIA muscles isolated from mdx and mdx;ML1MCK mice. (C) Trichrome collagen staining of DIA from 4-month-old mice. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Quantification of results (n indicates the number of the animal) averaged from multiple randomly selected images as shown in (C). (E and F) Thickness of IVS was measured by echocardiography (see fig. S2H) at the end diastole (E) and end systole (F) from 13- to 15-month-old WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK male mice. The echocardiographer was blind to the mouse genotype. (G) Calculated left ventricle mass in 13- to 15-month-old WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK male mice. (H) Peak velocity of E wave measured by LV pulse-wave Doppler (see fig. S2I) in 13- to 15-month-old WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK male mice. (I) Ratios between peak velocity of E and A waves (see fig. S2I) in WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK male mice. (J) Quantification for the percentage of fibrotic area in WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 13 to 15 months (see fig. S2J). All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Cardiac failure is another major cause of death in DMD, but cardiomyopathies are observed only in aged (e.g., >10-month-old) mdx mice (21, 22). We performed echocardiograms in 13- to 15-month-old WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK male mice (fig. S2H). Compared with WT mice, mdx mice had thickened interventricular septum (IVS) and increased left ventricle mass (Fig. 3, E to G), both of which are characteristic of dilated cardiomyopathies (21). Both echocardiographic abnormalities were ameliorated by ML1 overexpression (Fig. 3, E to G). We also performed pulse-wave Doppler echocardiography to analyze the contractile function of the left ventricle (fig. S2I). Consistent with previous studies (23), mdx hearts had reduced E wave velocity and E/A ratio (Fig. 3, H and I), suggestive of ventricular dysfunction. Both parameters were corrected by ML1MCK overexpression (Fig. 3, H and I). Histological analyses showed that cardiac fibrosis in aged (15-month-old) mdx mice was also reduced by ML1MCK expression (Fig. 3J and fig. S2J). Together, these results suggest that transgenic overexpression of ML1 is sufficient to attenuate dystrophies of both skeletal and cardiac muscles in DMD-like mouse models.

Pharmacological activation of ML1 in vivo ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mice

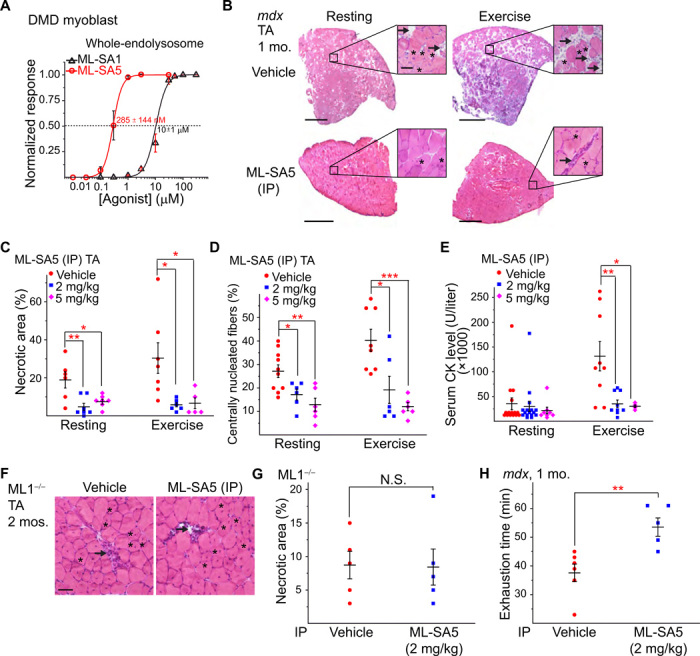

Next, we tested whether small-molecule ML1 agonists have a muscle protective effect in mdx mice. ML-SA5, a potent ML-SA compound with an in vitro EC50 (median effective concentration) value in the nanomolar range for endogenous ML1 (Figs. 1G and 4A), exhibited pharmacokinetic properties suitable for in vivo studies (fig. S3A). Mdx mice received daily intraperitoneal injection of ML-SA5, starting at P14 and continuing for at least 2 weeks. Like the vehicle [10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) + 40% polyethylene glycol (PEG) + 50% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]–treated group, no pathological signs were evident following ML-SA5 injection, manifested by normal body weight, complete blood count, liver biochemistry and histology, and kidney histology (fig. S3, B to J), suggesting the minimal toxicity effects. However, at the intraperitoneal dose of 2 to 5 mg/kg, daily ML-SA5 injection for 2 weeks decreased TA muscle necrosis by more than 70%, both at rest and after treadmill exercise (Fig. 4, B and C). Centrally nucleated fibers were also decreased in the ML-SA5–injected mdx mice (Fig. 4, B and D). Similar rescue effects were also seen in the GAS and DIA muscles (fig. S4, A to F). Consistently, serum CK level was also reduced in mdx mice that received ML1 agonist injection (Fig. 4E). In contrast, intraperitoneal injection of ML-SI6, a potent ML1 inhibitor (13, 24), worsened the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice (fig. S4, G to K). Furthermore, in ML1 KO mice that also exhibit a DMD-like phenotype such as necrosis and central nuclei (13), no obvious ML-SA5 rescue effects were seen (Fig. 4, F and G). Hence, the actions of ML-SA5 are likely to be mediated through ML1 (i.e., on target). Last, at the behavioral level, motor performance in a downhill treadmill test improved markedly following ML-SA injection in mdx mice (Fig. 4H). Therefore, similar to the genetic overexpression studies, pharmacological activation of ML1 in vivo using small molecules was also muscle protective.

Fig. 4. Small-molecule ML1 agonists ameliorate muscular dystrophies in mdx mice.

(A) ML-SA1 and ML-SA5 dose-dependently activated whole-endolysosomal ML1 currents in DMD myoblasts. (B) H&E staining of TA from 1-month-old mdx mice that received daily intraperitoneal injection of ML-SA5 (2 mg/kg) for 14 days starting at P14. Arrows and asterisks indicate necrotic areas and centrally nucleated fibers, respectively. Scale bar, 500 or 50 μm (zoom in). (C) Percentages of necrotic area in ML-SA5–injected mice. Each datum (n indicates the number of the muscle; n ≥ 4) represents the averaged result from at least three representative images randomly selected from at least three sections. Statistical analyses were performed by experimenters who were blind to treatment conditions. (D) Percentage of centrally nucleated fibers in ML-SA5–injected mice. (E) Serum CK levels in ML-SA5–treated mdx mice at the age of 1 month before and after treadmill exercise. (F and G) Effect of ML-SA5 intraperitoneal injection on TA from 2-month-old ML1 KO mice. Injection starts from P14. N.S., not significant. (H) Treadmill exhaustion time of mdx mice treated with ML-SA5 versus vehicle control. N, number of tested animals. The experimenter was blind to the treatment conditions. In the experiments shown in this figure, both male and female mice were randomly assigned into different treatment groups. All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

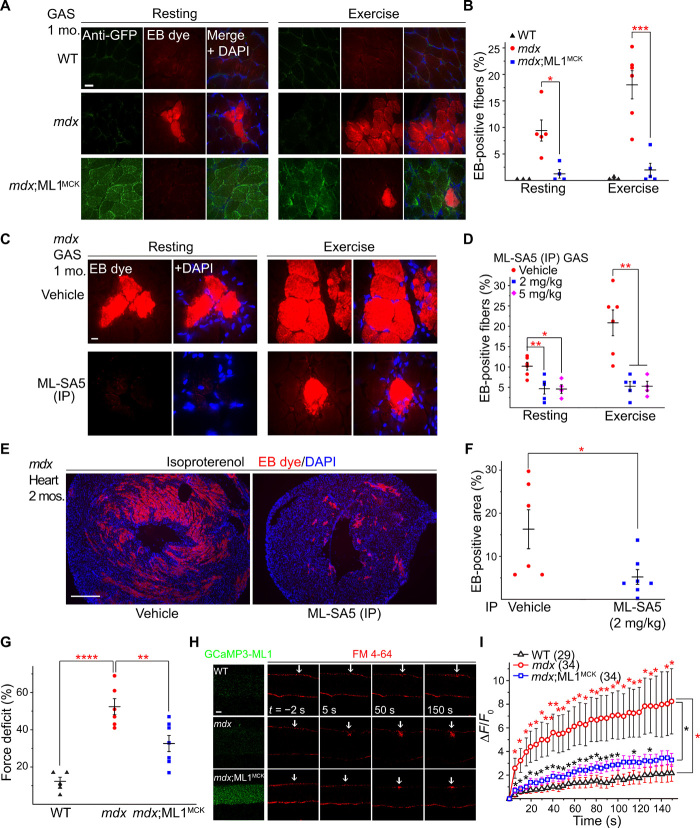

ML1 facilitates sarcolemma repair, thereby reducing skeletal and cardiac muscle damage in mdx mice

One of the major causes of muscular dystrophy is defective sarcolemma repair, and lysosomal exocytosis is a primary route for resealing damaged membranes (25). Given the essential role of ML1 in lysosomal exocytosis and membrane resealing (13), it is likely that ML1’s muscle protective effects are mediated by sarcolemma repair. Skeletal muscle damage was experimentally induced in vivo with a short-term treadmill exercise protocol (26) and confirmed with the entry of the membrane-impermeable Evans blue (EB) dye (13). The percentage of EB-positive fibers, which never exceeded 2% in WT muscles, reached 9% at rest and 18% after treadmill exercise in mdx muscles (Fig. 5, A and B). Notably, mdx;ML1MCK mice had less than 2% of EB-positive muscle fibers, even after treadmill exercise (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S5, A and B). EB uptake was also much reduced in ML-SA–treated mdx muscle (Fig. 5, C and D, and fig. S5, C and D) but increased in ML-SI–treated mdx mice (fig. S4, J and K). Likewise, when cardiomyocyte damage was induced in young (2-month-old) mdx mice with isoproterenol, EB uptake in the heart tissues was much reduced by ML-SA5 injection (Fig. 5, E and F). Collectively, these results suggest that compromised membrane integrity in both skeletal and cardiac muscles can be improved by ML1 up-regulation.

Fig. 5. ML1 activation facilitates sarcolemma repair to reduce muscle damage in mdx mice.

(A) Representative images of EB dye uptake in GAS isolated from WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 1 month, before (rest) and after treadmill exercise. Scale bar, 10 μm. GCaMP3-ML1 expression was detected using an anti-GFP antibody. (B) Quantification of EB-positive fibers from (A). Each datum (n, number of the muscle) represents the averaged result from at least five representative images selected from at least three sections. (C) EB dye uptake in GAS isolated from ML-SA5–treated mdx mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Quantification of EB dye uptake in GAS from ML-SA5–treated mdx mice. (E and F) EB dye uptake in cardiac muscles isolated from 2-month-old ML-SA5 (2 mg/kg)–injected mdx mice that were stimulated with β-isoproterenol to cause cardiac damage. Injection of ML-SA5 started from P14. Scale bar, 500 μm. (G) Muscle force deficit of mechanically stretched GAS from 1-month-old mice. (H) Representative images of laser damage–induced FM dye accumulation in isolated FDB fibers. Arrows highlight damage sites. Scale bar, 20 μm. (I) Time-dependent laser damage–induced FM dye accumulation in FDB fibers isolated from WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 1 month. n indicates the number of the FDB fibers for each genotype. In all the experiments shown in this figure, both male and female mice were randomly assigned into different experimental groups. All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

We also performed an ex vivo muscle damage test, in which in situ force in GAS muscles was measured before and after mechanical stretch by blind experimenters (27). The muscle force deficit seen in mdx mice was markedly reduced with ML1 overexpression (Fig. 5G), showing that ML1 expression has the potential to protect muscles from contraction-induced muscle damage in vivo. To study membrane repair in vitro, we used FM 4-64 dye to detect membrane disruptions (8) in single myofibers isolated from the flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscle (8, 9). Upon laser irradiation, mdx fibers continued to take up FM dye at the injury sites for several minutes, whereas FM dye uptake was much reduced in ML1-overexpressed mdx muscle (Fig. 5, H and I). These results suggest that ML1 activation facilitates membrane repair to reduce muscle damage in mdx mice.

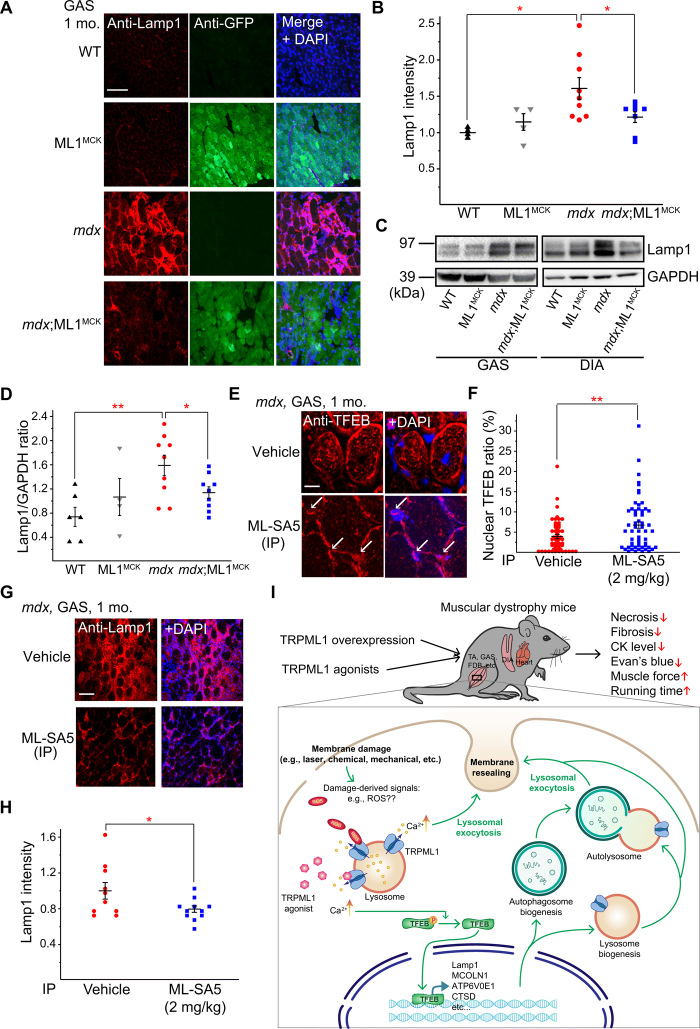

Up-regulation of ML1 in muscle activates transcriptional factor EB and corrects lysosomal insufficiency

Expression of lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (Lamp1) is an indicator of lysosome function in vivo such that Lamp1 up-regulation accompanies lysosomal dysfunction or insufficiency (28). Aberrant Lamp1 expression has been reported in several mdx studies (29, 30). We found that Lamp1 levels were increased in mdx compared with WT mice in both GAS and DIA isolated from 1-month-old animals (Fig. 6, A to D). In our immunofluorescence analysis, Lamp1 up-regulation was apparent in both muscle fibers and surrounding cells (e.g., infiltrated macrophages; Fig. 6A and fig. S5E), suggesting that inflammation, which is known to be associated with necrosis (31), may also contribute to Lamp1 up-regulation. Collectively, these results suggest that there is lysosome insufficiency in the muscle tissues of mdx mice and that lysosome biogenesis might have been weakly activated to compensate for the deficiency.

Fig. 6. ML1 agonist activates TFEB to correct lysosomal insufficiency in mdx muscles.

(A) Lamp1 immunofluorescence staining of GAS from WT, ML1MCK, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice at the age of 1 month. GCaMP3-ML1 expression was detected using an anti-GFP antibody. Scale bar, 100 μm. Both male and female mice were used in the experiments shown in this figure. (B) Quantitative analyses of images in (A). For each datum representing each muscle, at least five representative images from at least three sections were analyzed. (C) Western blotting analysis of Lamp1 protein expression in GAS and DIA from 1-month-old mice. (D) Quantitation of Western blotting results in (C). (E) TFEB immunolabeling in GAS from ML-SA5–treated mice at the age of 1 month. (F) Quantitative analysis of nuclear versus total TFEB ratio from (G). n indicates muscle fibers in randomly selected images from at least four muscles in each group. (G) Lamp1 immunostaining in GAS from ML-SA5 (2 mg/kg)–treated mdx mice at the age of 1 month. Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) Quantification of Lamp1 immunolabeling in GAS from ML-SA5–treated mdx mice. For each datum representing each muscle, at least five representative images from at least three sections were analyzed. (I) Genetic or pharmacological up-regulation of ML1 ameliorates myopathies in vivo through TFEB-dependent lysosome biogenesis, Ca2+-dependent lysosomal exocytosis, and sarcolemma repair. Muscle damage may generate a yet-to-be-defined signal (e.g., reactive oxygen species) (18) to activate ML1 channels on lysosome membranes. Subsequent lysosomal Ca2+ release triggers Ca2+-dependent lysosomal exocytosis and nuclear translocation of TFEB, which then activates transcription of a unique set of genes related to lysosome biogenesis. Subsequently, lysosome function is boosted and sarcolemma repair may be facilitated to reduce muscle damage in DMD cells in vitro and in vivo. All data are means ± SEM; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

ML1 activation has been reported to increase lysosome biogenesis and Lamp1 levels through nuclear translocation of transcriptional factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal genes (18, 32). Lamp1 expression was significantly lower in mdx;ML1MCK mice compared to mdx mice (Fig. 6, A to D). Likewise, the aberrant up-regulation of TFEB was also corrected by ML1 overexpression or activation (see fig. S5, F to H). These seemingly puzzling results may be explained by the fact that ML1 expression boosts lysosome function and decreases necrosis in muscle, obviating the need for compensatory changes via the expression of lysosomal genes. In mdx;ML1MCK mice or ML-SA5–injected mdx mice, TFEB nuclear translocation was increased (Fig. 6, E and F, and fig. S5F), but Lamp1 and TFEB up-regulation and other compensatory lysosomal changes, e.g. increased LC3-II levels, were suppressed (Fig. 6, G and H, and fig. S5, F to I). Hence, ML1 activation may further boost lysosome function to override lysosome insufficiency, yielding muscle protective effects. Similar scenarios have been reported in several lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs), in which TFEB activation has been found to increase lysosome biogenesis in WT cells while suppressing Lamp1 up-regulation in LSD animal models (14, 28).

ML1 protects human DMD muscle cells from damage through TFEB and lysosomal exocytosis

To study the role of ML1 activation in lysosome biogenesis directly, we used DMD cells, an immortalized myoblast line developed from a DMD patient’s muscle cells (fig. S6, A and B) (33). Only mild Lamp1 up-regulation was observed in DMD myoblasts (fig. S6C), suggesting that the lysosome insufficiency occurring in mdx mice might be caused by extensive in vivo muscle damage. Consistent with our lysosomal patch-clamp studies (Fig. 4A), nanomolar concentrations of ML1 agonists were sufficient to induce notable nuclear translocation of TFEB (fig. S6, D and E) and the related protein TFE3 (fig. S6, F and G). Consistently, expression of TFEB/TFE3 target genes, including those required for lysosome biogenesis and function, were elevated by ML-SA5 treatment (fig. S6H). Notably, TFEB mRNA and protein expressions were significantly reduced in ML-SA5–treated WT and DMD cells (fig. S6, H to K), suggestive of the negative feedback regulation. Hence, ML1 activation may lead to TFEB nuclear translocation, thereby increasing lysosome biogenesis, which, in turn, reduces lysosome stress and restores lysosome homeostasis.

Whereas increased TFEB activation and lysosome biogenesis may amplify lysosomal trafficking events including lysosomal exocytosis (34), ML1 activation alone can trigger lysosomal exocytosis directly (35). Membrane damage [i.e., chemical injury caused by streptolysin O (SLO) toxin] triggers lysosomal exocytosis and membrane repair (25). In myofibers, which contain a large cytoplasm, ML1-mediated lysosomal Ca2+ release, but not Ca2+ influx mediated by overexpressed ML1 channels (36) (see fig. S7, A to E), may preferentially activate lysosome-localized Ca2+ sensors to facilitate lysosomal exocytosis and biogenesis. Propidium iodide (PI) staining is a common readout for membrane damage and cell viability (37). In DMD myoblasts and differentiated myotubes, both membrane damage and ML-SA treatment induced lysosomal exocytosis (fig. S9, A and B), suggesting that ML-SAs may trigger membrane repair processes by mimicking a yet-to-be-identified damage signal. Consistent with this hypothesis, ML1 agonists and inhibitors decreased and increased, respectively, PI-positive cells following SLO treatment (fig. S8, A to D). The cytoprotective effects of ML-SAs were abolished by knockdown of TFEB expression (fig. S8, E to H) or blockage of lysosomal exocytosis with dominant-negative synaptotagmin VII (Syt-VII) (fig. S9, C and D). Collectively, these results suggest that boosting ML1 activity may promote myocyte survival by reducing membrane damage via a direct and acute mechanism (i.e., lysosomal exocytosis), as well as through an indirect and more sustained mechanism (i.e., lysosome biogenesis; Fig. 6I).

DISCUSSION

ML1 deficiency causes a DMD-like muscle phenotype in both humans and rodents (13). In the current study, we found that both genetic and pharmacological activation of ML1 had muscle protective effects in mdx mice and human DMD muscle cells. ML1 activation led to TFEB nuclear translocation and increased lysosomal biogenesis while also increasing lysosomal trafficking (e.g., exocytosis), thereby facilitating sarcolemma repair to reduce muscle damage (Fig. 6I). Hence, our proof-of-concept study has provided strong evidence that small-molecule ML1 agonists can be developed to treat DMD. Upon withdrawal of ML-SA compounds, the muscle protective effects of the drugs disappeared (see fig. S10), suggesting that sustained or periodic activation of lysosome enhancement is required for DMD treatment. Although DMD is not an LSD per se (28), the observed compensatory changes are suggestive of lysosome insufficiency. In both cases, augmenting ML1/TFEB-dependent lysosome biogenesis can alleviate lysosome insufficiency. Since ML1 is a ubiquitously expressed lysosomal channel, there could be “on-target” adverse effects of ML1 activation on nonmuscle issues in mdx mice. However, ML1/TFEB activation is most effective in cells/tissues with lysosome dysfunction/insufficiency, and ML1/TFEB-mediated lysosome biogenesis is suppressed by multiple mechanisms in healthy cells (28, 38). Hence, the on-target, “overstimulating” effects of ML1 may be minimal on healthy cells/tissues/animals.

The simplest explanation for the presently observed muscle protective effect of ML1, in our view, would be facilitation of lysosomal exocytosis and membrane repair (Fig. 6I). However, although blockage of lysosomal exocytosis abolished ML1-dependent muscle protection, it should be noted that overexpression of Syt-VII dominant-negative constructs might indirectly affect lysosome biogenesis and TFEB-dependent functions. TFEB has been shown to be muscle protective in other studies as well (14). In LSDs, ML1 and TFEB form a positive feedback loop that promotes cellular clearance (28). It is possible that the same lysosome program may boost sarcolemma repair to reduce muscle damage in DMD and other muscle diseases. Hence, manipulating lysosome function with small molecules may have broad therapeutic potential.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The overall goal of this study was to determine the effect of ML1 up-regulation on muscular dystrophy and membrane repair. All data presented here were replicated in at least four mice or three biological replicates for in vitro experiments, with all histochemical staining data quantified by experimenters who were blind to genotypes/treatments. On the basis of pilot studies of ML1 up-regulation on various pathologic hallmarks in mice, with a power of 0.8 and P < 0.05, we calculated a sample size of between 5 and 11 mice per group. Animals were randomly allocated into control and experimental groups.

Mouse lines

We generated muscle cell–specific ML1-overexpressing (ML1 ROSA-lSl;MCK Cre or ML1MCK) mice by crossing ROSA-loxSTOPlox-GCaMP3-ML1 (abbreviated ML1 ROSA-lSl) mice with a muscle cell–specific Cre line (MCK-Cre) (15). Mdx (001801) and utrophin+/−;mdx (014563) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. ML1−/− mice were provided by S. Slaugenhaupt (13). All mice used in the study were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 genetic background. Mice were used under the University of Michigan’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee’s approval. For cardiac function studies, only hemizygous male mice at the age of 13 to 15 months were used. For histological and physiological studies of skeletal muscles, both hemizygous male and homozygous female mdx mice were randomly assigned into different groups. The muscle type and age of the mice used for each experiment were indicated in the figures and legends.

Western blotting

After lysing muscle tissues in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche), 20 to 40 μg of total protein aliquots were loaded into 4 to 12% bis-tris or 3 to 8% tris-acetate SDS–polyacrylamide gradient gels (Invitrogen) and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes via iBlot 2 Gel Transfer Device (Life Technologies). The membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) skim milk in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 for 1 hour and then incubated overnight in the blocking buffer at 4°C. The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-ML1 (ACC-081, Alomone Labs), anti–green fluorescent protein (GFP) (A6455, Invitrogen), anti-mouse Lamp1 [1D4B, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)], anti-human Lamp1 (H4A3, DSHB), anti-mouse TFEB (A303-673A, Bethyl), anti-human TFEB (4240, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-LC3 (L8918, Sigma), anti-dystrophin (ab15277, Abcam), anti-utrophin (8A4, DSHB), anti–α-dystroglycan (sc-53987, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (MAB347, Millipore). Peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-rat secondary antibodies were applied at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Bands were quantitated in ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence

Muscle tissues, harvested and frozen in 2-methylbutane, prechilled in liquid nitrogen, were cryosectioned at 12 μm. After being washed with tris-buffered saline (TBS) + 0.025% Triton X-100, sections were blocked with 10% serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in TBS at room temperature for 2 hours. Cell lines and isolated primary cells cultured on coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Fixed cells and cryosections were then incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies targeting ML1, GFP, Lamp1, TFEB, dystrophin, or CD11b (M1/70.15.11.5.2, DSHB) at 1:50 or 1:200 solutions. Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were then applied for 1 hour in the dark at room temperature, followed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole counterstaining if necessary. Cells and tissue sections were imaged on a spinning disc confocal imaging system composed of an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope; 10×, 20×, and 60× Olympus objectives; a CSU-X1 scanner (Yokogawa); an iXon electron multiplying charge-coupled device camera (Andor); and MetaMorph Advanced Imaging acquisition software v.7.7.8.0 (Molecular Devices). Image analysis results were quantified in MetaMorph software.

Primary muscle cell culture

Murine myoblasts were harvested and cultured as previously described (39). Briefly, skeletal muscles were isolated from P0 to P3 pups and dissociated with 0.25% trypsin supplemented with collagenase (2 mg/ml) (Sigma) at 37°C. To remove fibroblasts, cells were preplated on a standard, non–tissue culture–coated petri dish for 60 to 90 min. Muscle cells were then counted, seeded onto collagen-coated glass coverslips, and maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 in F10 medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin/streptomycin. To induce differentiation, myoblasts were grown to confluence before switching to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 5% horse serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Electrophysiology, Ca2+ imaging, and immunofluorescence labeling were performed after 3 days of differentiation induction to allow MCK-Cre expression.

Whole-endolysosome electrophysiology

Endolysosomal electrophysiology was performed on isolated endolysosomes from muscle cells treated with 1 μM vacuolin-1 to enlarge late endosomes and lysosomes (40, 41). The bath (internal/cytoplasmic) solution contained 140 mM K gluconate, 4 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 2 mM Na2–adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.39 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM guanosine triphosphate (GTP), and 10 mM Hepes [pH adjusted with KOH to 7.2; the free [Ca2+]i was estimated to be ~100 nM on Maxchelator software (https://bit.ly/2G7fIVH)]. The pipette (luminal) solution consisted of a low-pH Tyrode’s solution with 145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM MES, and 10 mM glucose (pH 4.6). A perfusion system was used to ensure efficient solution exchange. Data were collected with an Axopatch 200A patch-clamp amplifier, Digidata 1440, and pClamp 10.0 software (Axon Instruments). Currents were digitized at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. All experiments were conducted at 21° to 23°C, and all recordings were analyzed in pClamp 10.0 and Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

GCaMP3 Ca2+ imaging

Ca2+ imaging was performed in ML1MCK and mdx;ML1MCK primary myotubes overexpressing GCaMP3-ML1 (15). The fluorescence intensity at 488 nm (F488) was recorded with the spinning disc confocal imaging system.

Histochemical staining

Frozen sections were warmed to room temperature and hydrated in double-distilled (MilliQ) H2O. Tissues were stained with H&E dyes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for the nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively, followed by gradient washing in ethanol (70, 90, and 100%) and xylene (100%). The stained sections were mounted in Permount medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Staining quantification was performed blindly following standardized operating procedures (SOP number: DMD_M.1.2.007). Necrotic myofibers, inflammatory cells, and fibroblasts were all counted as necrotic area. Collagen content was assessed with a Masson’s trichrome kit (Sigma). Area stained with blue color was quantified as fibrotic area.

Muscle force measurement

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (tribromoethanol, 250 mg/kg) and placed on a warmed platform to maintain body temperature. GAS muscle contractile properties were measured in situ, as described previously (42). Briefly, after the GAS was isolated from surrounding tissues, the distal tendon was secured to the lever arm of a servomotor (model 6650LR, Cambridge Technology). The knee and foot were clamped to the platform. The muscle was activated by tibial nerve stimulation. With the muscle held at optimal length (L0), 300-ms trains of stimulus pulses were applied at increasing frequencies until the maximum isometric tetanic force (P0) was achieved. After the pre-stretch P0 (preP0) was recorded, we applied two stretches (12 s apart) of 30% of fiber length (Lf), which was estimated by multiplying L0 by previously determined Lf-to-L0 ratios. After a 1-min rest, post-stretch P0 (postP0) was obtained to determine the force deficit. To maintain muscle temperature and moisture, a warm saline drip (37°C) was applied to the GAS continuously throughout the procedure. After the experiment, mice were euthanized, and muscles were removed and trimmed of their tendons. Physiological cross-sectional areas were determined by dividing muscle mass by the product of Lf using a density of mammalian skeletal muscle of 1.06 g/cm3. Specific P0 (SP0) refers to P0 per cross-sectional area, and the force deficit was calculated as 1 − postP0/preP0.

Echocardiography

Echocardiograms were performed by following the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography as described previously (43). All echocardiography experiments were performed by one registered echocardiographer who was blind to the mouse genotype. Before imaging, 13- to 15-month-old WT, mdx, and mdx;ML1MCK mice were weighed and anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane. Imaging was performed using a Vevo 770 Microimaging system (VisualSonics Inc.) equipped with an RMV707B (15 to 45 MHz) transducer. Left ventricular (LV) wall thickness was measured at end systole and end diastole. Mitral valve E and A wave inflow velocities were sampled at the tips of the mitral valve leaflets from the apical four-chamber view. LV mass (LVM) was calculated using the formula LVM = 1.053*[(LVID;d + LVPW;d + IVS;d)3 – LVID;d3], with the LV internal diameter (LVID), the LV posterior wall thickness (LVPW), and IVS being measured during diastole (d) from the parasternal short-axis view at the tip levels of the mitral valve leaflets.

Injection of small-molecule compounds

At P14, mdx mice were weighed and randomized into treatment groups. ML-SA compounds (dissolved in 10% DMSO, 40% PEG300, and 50% PBS) were administered to mice by intraperitoneal injection. After 14 days of daily injection, the mice were subjected to various behavioral tests or sacrificed for histological and biochemical analyses. For EB staining in the cardiac muscle and toxicity studies, drug injection was extended for one more month until the mice reached 2 months old. To induce cardiomyopathy in 2-month-old mdx mice, β-isoproterenol (0.5 mg/kg) (Sigma) was injected subcutaneously 1 day before sacrificing (44). ML-SA and ML-SI compounds were identified initially by Ca2+ imaging–based high-throughput screening conducted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Chemical Genomics Center (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioassay/624414), and their potencies were improved by medicinal chemistry. All ML-SA and ML-SI compounds are available upon request under material transfer agreement with the University of Michigan.

Treadmill exercise

Mice were trained on an Exer-6M treadmill (Columbus Instruments). Before running, they were acclimated to the treadmill chamber for 30 min. To induce damage, P28 mice ran on the treadmill with a 15° downgrade at 12 to 15 m/min for 30 min 1 day before being sacrificed for analysis (26). To measure exhaustion time, the treadmill was set to a speed of 12 to 20 m/min.

Uptake of EB dye

Freshly prepared 1% (w/v) EB dye (Sigma) in PBS was injected intraperitoneally at 10 ml/kg 1 day before tissue collection.

Measurement of CK activity

Venous tail blood was collected before and after treadmill exercise, and serum was separated by centrifugation. Serum CK activity was measured with a Creatine Kinase Activity Assay kit (Abcam) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Complete blood count and liver biochemistry

Venous tail blood was collected in the EDTA tubes and sent to a laboratory test for complete blood count at room temperature immediately after collection. For liver biochemistry, serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at −80°C until sent for analysis.

Myofiber damage assay

After mice were sacrificed, FDB muscles were removed surgically and then digested in type I collagenase (2 mg/ml) (Sigma) at 37°C for 60 min. After trituration and resuspension in FluoroBrite DMEM solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific), single FDB fibers were mounted on a glass bottom dish precoated with Matrigel (Corning) and then stained with FM 4-64 dye (5 μg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) immediately before imaging. A Leica SP5 inverted confocal microscope system with a multiphoton laser (laser power of 2.3 W at wavelength 820 nm) was used to irradiate the fibers and take images. Fluorescence intensity at the injury site was measured by ImageJ software.

Muscle cell line culture

Immortalized human myoblast cell lines, including a WT line (ref. AB1079C38Q) and a DMD line (ref. AB1023DMD11Q: stop in exon 59), were provided by V. Mouly at the Institut de Myologie in France (45). Myoblasts were grown in KMEM (one volume of medium-199 + four volumes of DMEM, both from Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 20% FBS, fetuin (25 μg/ml, Sigma), insulin (5 μg/ml, Sigma), basic fibroblast growth factor (0.5 ng/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific), human epidermal growth factor (5 ng/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and dexamethasone (0.2 μg/ml, Sigma) in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C. Myoblasts were induced to differentiate into myotubes by switching to medium containing DMEM with gentamicin (50 μg/ml) and insulin (10 μg/ml).

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from cultured human myoblasts with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and then purified with a Turbo DNA-free kit (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was then synthesized with a SuperScript III RT kit (Invitrogen). We conducted real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with the PowerUp SYBR Green 2× Master Mix (Invitrogen) and the following PCR primers (32): HPRT [forward (fw), 5′-tggcgtcgtgattagtgatg-3′; reverse (rev), 5′-aacaccctttccaaatcctca-3′], PGC1α (fw, 5′-catgcaaatcacaatcacagg-3′; rev, 5′-ttgtggcttttgctgttgac-3′), MCOLN1 (fw, 5′-gagtgggtgcgacaagtttc-3′; rev, 5′-tgttctcttcccggaatgtc-3′), ATP6V0E1 (fw, 5′-cattgtgatgagcgtgttctgg-3′; rev, 5′ -aactccccggttaggaccctta-3′), ATP6V1H (fw, 5′-ggaagtgtcagatgatcccca-3′; rev, 5′-ccgtttgcctcgtggataat-3′), CTSF (fw, 5′-acagaggaggagttccgcacta-3′; rev, 5′-gcttgcttcatcttgttgcca-3′), TFEB (fw, 5′-caaggccaatgacctggac-3′; rev, 5′-agctccctggacttttgcag-3′), CTSD (fw, 5′-cttcgacaacctgatgcagc-3′; rev, 5′-tacttggagtctgtgccacc-3′), PPP3CA (fw, 5′-gctgccctgatgaaccaac-3′; rev, 5′-gcaggtggttctttgaatcgg-3′), DPP7 (fw, 5′-gattcggaggaacctgagtg-3′; rev, 5′-cggaagcaggatcttctgg-3′), CTSB (fw, 5′-agtggagaatggcacacccta-3′; rev, 5′-aagagccattgtcacccca-3′), TPP1 (fw, 5′-gatcccagctctcctcaatac-3′; rev, 5′-gccatttttgcaccgtgtg-3′), and NEU1 (fw, 5′-tgaagtgtttgcccctggac-3′; rev, 5′-aggcaccatgatcatcgctg-3′).

Silencing RNA knockdown

TFEB expression was transfected with small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides (5′-gaaaggagacgaagguucaacauca-3′) and Lipofectamine 2000 (both from Invitrogen). Cells were subjected to biochemical and cell biological analyses 72 hours after transfection.

Flow cytometry PI staining

Cells were pretreated with various compounds, digested in Accutase, and then washed with Tyrode’s solution supplemented with 20% FBS. After counting, cell membranes were damaged with SLO toxin (1 μg/ml, 10 min) at 37°C. His-tagged SLO (carrying a cysteine deletion that eliminates the need for thiol activation) (37) was provided by R. Tweeten (University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK) and purified as described previously (13). SLO-treated cells were stained with PI (2 μg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 5 min and analyzed by the Attune NxT Acoustic Focusing Cytometer (Life Technologies). Total cell events were measured with Vybrant DyeCycle Violet stain (Invitrogen). At least 10,000 cells were used for each experimental group. Data were analyzed in Attune NxT software.

Lamp1 surface labeling

After 3 days of differentiation, immortalized human myotubes pretreated with ML-SAs were incubated with SLO (0.5 to 1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min. Nonpermeabilized cells were labeled with anti-human Lamp1 (H4A3) antibody, which recognizes a luminal epitope, at 4°C for 1 hour. Cells were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and incubated with Alexa Flour 488–conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 hour.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Turkey’s post hoc tests or with paired and unpaired Student’s t tests where appropriate. A value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Slaugenhaupt for providing ML1 KO mice; V. Mouly from Institut de Myologie in Paris for immortalized control and DMD human cell lines; L. Looger for the GCaMP3 construct; and D. Sun, D. Michele, M. Akaaboune, R. Han, J. Kuwada, and R. Hume for constructive suggestions. We appreciate the encouragement and helpful comments of other members of the Xu laboratory. Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants (NS062792, AR060837, and DK115474 to H.X. and P30 AR069620 to Michigan Integrative Musculoskeletal Health Core Center). Additional support was provided by an M-Cubed grant, a PFD disease initiative grant, and a Rackham Dissertation Fellowship from the University of Michigan. A sponsored research grant from CalyGene Biotechnology provided interim funding for research supplies. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The work of NCATS’ authors was carried out using funding of their intramural research program. Author contributions: L.Y. designed and conducted experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. X.Z., Y.Y., D.L., K.T., Z.Z., W.H., C.W., K.C.-B., and C.S.D. conducted experiments and analyzed data. S.V.B. analyzed data. A.B. provided reagents. R.C., N.S., X.H., J.M., and M.F. performed high-throughput screening and medicinal chemistry. H.X. designed the study and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and proofread the manuscript. Competing interests: H.X. is the scientific cofounder of CalyGene Biotechnology Inc. H.X., M.F., J.M., R.C., N.J.M., N.S., and X.H. are inventors on a pending patent related to this work filed by the NIH and the University of Michigan. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. ML-SA5 and other reagents are available upon request under material transfer agreement with the University of Michigan. All reagents in this study can be provided by the University of Michigan pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/6/eaaz2736/DC1

Fig. S1. Muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of ML1.

Fig. S2. Muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of ML1 reduces GAS, DIA, and cardiac pathologies in mdx mice.

Fig. S3. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of ML-SA5.

Fig. S4. ML1 agonist injection (intraperitoneal) ameliorates GAS and DIA pathologies in mdx mice.

Fig. S5. Activation of ML1 corrects lysosomal insufficiency and improves sarcolemmal repair in mdx mice.

Fig. S6. ML1 agonist activates TFEB/TFE3 and lysosomal biogenesis in DMD myoblasts.

Fig. S7. Sarcolemmal Ca2+ entry is not required for ML-SA–induced TFEB nuclear translocation.

Fig. S8. ML1 agonist prevents cell death in DMD myoblasts via TFEB.

Fig. S9. Lysosomal exocytosis is required for ML-SA5–induced sarcolemma repair and cell survival.

Fig. S10. Requirement of continuous agonist administration in achieving muscle protective effects.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Mercuri E., Muntoni F., Muscular dystrophies. Lancet 381, 845–860 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies K. E., Nowak K. J., Molecular mechanisms of muscular dystrophies: Old and new players. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 762–773 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimov F., Kunkel L. M., The cell biology of disease: Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Biol. 201, 499–510 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen D. G., Whitehead N. P., Froehner S. C., Absence of dystrophin disrupts skeletal muscle signaling: Roles of Ca2+, reactive oxygen species, and nitric oxide in the development of muscular dystrophy. Physiol. Rev. 96, 253–305 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell K. P., Three muscular dystrophies: Loss of cytoskeleton-extracellular matrix linkage. Cell 80, 675–679 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stedman H. H., Sweeney H. L., Shrager J. B., Maguire H. C., Panettieri R. A., Petrof B., Narusawa M., Leferovich J. M., Sladky J. T., Kelly A. M., The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature 352, 536–539 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amoasii L., Long C., Li H., Mireault A. A., Shelton J. M., Sanchez-Ortiz E., McAnally J. R., Bhattacharyya S., Schmidt F., Grimm D., Hauschka S. D., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N., Single-cut genome editing restores dystrophin expression in a new mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaan8081 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansal D., Miyake K., Vogel S. S., Groh S., Chen C.-C., Williamson R., McNeil P. L., Campbell K. P., Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature 423, 168–172 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai C., Masumiya H., Weisleder N., Matsuda N., Nishi M., Hwang M., Ko J.-K., Lin P., Thornton A., Zhao X., Pan Z., Komazaki S., Brotto M., Takeshima H., Ma J., MG53 nucleates assembly of cell membrane repair machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 56–64 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNeil P., Membrane repair redux: Redox of MG53. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 7–9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills E., Dong X.-p., Wang F., Xu H., Mechanisms of brain iron transport: Insight into neurodegeneration and CNS disorders. Future Med. Chem. 2, 51–64 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen D., Wang X., Li X., Zhang X., Yao Z., Dibble S., Dong X.-p., Yu T., Lieberman A. P., Showalter H. D., Xu H., Lipid storage disorders block lysosomal trafficking by inhibiting a TRP channel and lysosomal calcium release. Nat. Commun. 3, 731 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng X., Zhang X., Gao Q., Ali Samie M., Azar M., Tsang W. L., Dong L., Sahoo N., Li X., Zhuo Y., Garrity A. G., Wang X., Ferrer M., Dowling J., Xu L., Han R., Xu H., The intracellular Ca2+ channel MCOLN1 is required for sarcolemma repair to prevent muscular dystrophy. Nat. Med. 20, 1187–1192 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spampanato C., Feeney E., Li L., Cardone M., Lim J.-A., Annunziata F., Zare H., Polishchuk R., Puertollano R., Parenti G., Ballabio A., Raben N., Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is a new therapeutic target for Pompe disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 5, 691–706 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahoo N., Gu M., Zhang X., Raval N., Yang J., Bekier M., Calvo R., Patnaik S., Wang W., King G., Samie M., Gao Q., Sahoo S., Sundaresan S., Keeley T. M., Wang Y., Marugan J., Ferrer M., Samuelson L. C., Merchant J. L., Xu H., Gastric acid secretion from parietal cells is mediated by a Ca2+ efflux channel in the tubulovesicle. Dev. Cell 41, 262–273.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruning J. C., Michael M. D., Winnay J. N., Hayashi T., Hörsch D., Accili D., Goodyear L. J., Kahn C. R., A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol. Cell 2, 559–569 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke M. S., Khakee R., McNeil P. L., Loss of cytoplasmic basic fibroblast growth factor from physiologically wounded myofibers of normal and dystrophic muscle. J. Cell Sci. 106 (Pt. 1), 121–133 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X., Cheng X., Yu L., Yang J., Calvo R., Patnaik S., Hu X., Gao Q., Yang M., Lawas M., Delling M., Marugan J., Ferrer M., Xu H., MCOLN1 is a ROS sensor in lysosomes that regulates autophagy. Nat. Commun. 7, 12109 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straub V., Rafael J. A., Chamberlain J. S., Campbell K. P., Animal models for muscular dystrophy show different patterns of sarcolemmal disruption. J. Cell Biol. 139, 375–385 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grady R. M., Teng H., Nichol M. C., Cunningham J. C., Wilkinson R. S., Sanes J. R., Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: A model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 90, 729–738 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinlan J. G., Hahn H. S., Wong B. L., Lorenz J. N., Wenisch A. S., Levin L. S., Evolution of the mdx mouse cardiomyopathy: Physiological and morphological findings. Neuromuscul. Disord. 14, 491–496 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danilowicz D., Rutkowski M., Myung D., Schively D., Echocardiography in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 3, 298–303 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adamo C. M., Dai D.-F., Percival J. M., Minami E., Willis M. S., Patrucco E., Froehner S. C., Beavo J. A., Sildenafil reverses cardiac dysfunction in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 19079–19083 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W., Gao Q., Yang M., Zhang X., Yu L., Lawas M., Li X., Bryant-Genevier M., Southall N. T., Marugan J., Ferrer M., Xu H., Up-regulation of lysosomal TRPML1 channels is essential for lysosomal adaptation to nutrient starvation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E1373–E1381 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng X., Zhang X., Yu L., Xu H., Calcium signaling in membrane repair. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 45, 24–31 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radley-Crabb H., Terrill J., Shavlakadze T., Tonkin J., Arthur P., Grounds M., A single 30 min treadmill exercise session is suitable for ‘proof-of concept studies’ in adult mdx mice: A comparison of the early consequences of two different treadmill protocols. Neuromuscul. Disord. 22, 170–182 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks S. V., Faulkner J. A., The magnitude of the initial injury induced by stretches of maximally activated muscle fibres of mice and rats increases in old age. J. Physiol. 497, 573–580 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu H., Ren D., Lysosomal physiology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 57–80 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pal R., Palmieri M., Loehr J. A., Li S., Abo-Zahrah R., Monroe T. O., Thakur P. B., Sardiello M., Rodney G. G., Src-dependent impairment of autophagy by oxidative stress in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Commun. 5, 4425 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duguez S., Duddy W., Johnston H., Lainé J., le Bihan M. C., Brown K. J., Bigot A., Hathout Y., Butler-Browne G., Partridge T., Dystrophin deficiency leads to disturbance of LAMP1-vesicle-associated protein secretion. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 70, 2159–2174 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tidball J. G., Inflammatory processes in muscle injury and repair. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 288, R345–R353 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medina D. L., di Paola S., Peluso I., Armani A., de Stefani D., Venditti R., Montefusco S., Scotto-Rosato A., Prezioso C., Forrester A., Settembre C., Wang W., Gao Q., Xu H., Sandri M., Rizzuto R., de Matteis M. A., Ballabio A., Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 288–299 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarathy A., Wuebbles R. D., Fontelonga T. M., Tarchione A. R., Mathews Griner L. A., Heredia D. J., Nunes A. M., Duan S., Brewer P. D., van Ry T., Hennig G. W., Gould T. W., Dulcey A. E., Wang A., Xu X., Chen C. Z., Hu X., Zheng W., Southall N., Ferrer M., Marugan J., Burkin D. J., SU9516 increases α7β1 integrin and Ameliorates disease progression in the mdx mouse model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 25, 1395–1407 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medina D. L., Fraldi A., Bouche V., Annunziata F., Mansueto G., Spampanato C., Puri C., Pignata A., Martina J. A., Sardiello M., Palmieri M., Polishchuk R., Puertollano R., Ballabio A., Transcriptional activation of lysosomal exocytosis promotes cellular clearance. Dev. Cell 21, 421–430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samie M., Wang X., Zhang X., Goschka A., Li X., Cheng X., Gregg E., Azar M., Zhuo Y., Garrity A. G., Gao Q., Slaugenhaupt S., Pickel J., Zolov S. N., Weisman L. S., Lenk G. M., Titus S., Bryant-Genevier M., Southall N., Juan M., Ferrer M., Xu H., A TRP channel in the lysosome regulates large particle phagocytosis via focal exocytosis. Dev. Cell 26, 511–524 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilpatrick B. S., Yates E., Grimm C., Schapira A. H., Patel S., Endo-lysosomal TRP mucolipin-1 channels trigger global ER Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx. J. Cell Sci. 129, 3859–3867 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idone V., Tam C., Goss J. W., Toomre D., Pypaert M., Andrews N. W., Repair of injured plasma membrane by rapid Ca2+-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 180, 905–914 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P., Gu M., Xu H., Lysosomal ion channels as decoders of cellular signals. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44, 110–124 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Springer M. L., Rando T. A., Blau H. M., Gene delivery to muscle. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. Chapter 13, Unit13.4 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong X.-P., Cheng X., Mills E., Delling M., Wang F., Kurz T., Xu H., The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature 455, 992–996 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong X.-p., Shen D., Wang X., Dawson T., Li X., Zhang Q., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Weisman L. S., Delling M., Xu H., PI(3,5)P2 controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca2+ release channels in the endolysosome. Nat. Commun. 1, 38 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larkin L. M., Davis C. S., Sims-Robinson C., Kostrominova T. Y., Remmen H. V., Richardson A., Feldman E. L., Brooks S. V., Skeletal muscle weakness due to deficiency of CuZn-superoxide dismutase is associated with loss of functional innervation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 301, R1400–R1407 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boluyt M. O., Converso K., Hwang H. S., Mikkor A., Russell M. W., Echocardiographic assessment of age-associated changes in systolic and diastolic function of the female F344 rat heart. J. Appl. Physiol. 96, 822–828 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yue Y., Skimming J. W., Liu M., Strawn T., Duan D., Full-length dystrophin expression in half of the heart cells ameliorates β-isoproterenol-induced cardiomyopathy in mdx mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 1669–1675 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mamchaoui K., Trollet C., Bigot A., Negroni E., Chaouch S., Wolff A., Kandalla P. K., Marie S., di Santo J., St Guily J., Muntoni F., Kim J., Philippi S., Spuler S., Levy N., Blumen S. C., Voit T., Wright W. E., Aamiri A., Butler-Browne G., Mouly V., Immortalized pathological human myoblasts: Towards a universal tool for the study of neuromuscular disorders. Skelet. Muscle 1, 34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/6/eaaz2736/DC1

Fig. S1. Muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of ML1.

Fig. S2. Muscle-specific transgenic overexpression of ML1 reduces GAS, DIA, and cardiac pathologies in mdx mice.

Fig. S3. Pharmacokinetics and toxicity of ML-SA5.

Fig. S4. ML1 agonist injection (intraperitoneal) ameliorates GAS and DIA pathologies in mdx mice.

Fig. S5. Activation of ML1 corrects lysosomal insufficiency and improves sarcolemmal repair in mdx mice.

Fig. S6. ML1 agonist activates TFEB/TFE3 and lysosomal biogenesis in DMD myoblasts.

Fig. S7. Sarcolemmal Ca2+ entry is not required for ML-SA–induced TFEB nuclear translocation.

Fig. S8. ML1 agonist prevents cell death in DMD myoblasts via TFEB.

Fig. S9. Lysosomal exocytosis is required for ML-SA5–induced sarcolemma repair and cell survival.

Fig. S10. Requirement of continuous agonist administration in achieving muscle protective effects.