Abstract

Cranial neural crest cells are multipotent cells that migrate into the pharyngeal arches of the vertebrate embryo and differentiate into various craniofacial organ derivatives. Therefore, migrating cranial neural crest cells are considered one of the most attractive candidate cell sources in regenerative medicine. We generated cranial neural crest like cell (cNCCs) using mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells cultured in neural crest-inducing medium for 14 days. Subsequently, we conducted RNA sequencing experiments to analyze gene expression profiles of cNCCs at different time points after induction. cNCCs expressed several neural crest specifier genes; however, some previously reported specifier genes such as paired box 3 and Forkhead box D3, which are essential for embryonic neural crest development, were not expressed. Moreover, ETS proto-oncogene 1, transcription factor and sex-determining region Y-box 10 were only expressed after 14 days of induction. Finally, cNCCs expressed multiple protocadherins and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs enzymes, which may be crucial for their migration.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00795-019-00229-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cranial neural crest, Migratory neural crest, iPS cells, RNA sequencing, Adamts

Introduction

Stem cell-based tissue engineering is important in the field of oral science because it facilitates the regeneration of damaged tissues or organs [1, 2]. Various stem cell populations exhibiting regeneration potential in the craniofacial region have been identified. Of these, cranial neural crest cells (cNCCs) are considered one of the most important candidates owing to their role in craniofacial tissue organization [3]. cNCCs comprise a multipotent population of migratory cells that are unique to the vertebrate embryo and can differentiate into various craniofacial organ derivatives [4, 5]. The neural crest (NC) can form teratoma when transplanted into immunocompromised animals [6]. cNCC development involves three stages [7–10]: the neural plate border stage, the premigratory stage, and the migratory stage. During the migratory stage, cNCCs delaminate from the posterior midbrain and individual rhombomeres in the hindbrain [11] and migrate into the pharyngeal arches to form skeletal elements of the face and teeth and contribute to formation of the pharyngeal glands (the thymus, thyroid, and parathyroid) [12]. Therefore, cNCCs presumably represent a new treatment strategy for diseases of the craniofacial region [13].

Development from the premigratory to migratory stage proceeds swiftly [14]; thus, it is typically difficult to detect the precise time point of this transition [15]. A recent transcriptome analysis of pure populations of migratory cNCCs cells expressing the sex-determining region Y-box 10 (Sox10) from chicks [16] has substantially improved our understanding of cNCC characteristics. However, whether these cells are in the migratory stage and how long it takes to promote embryonic stem (ES) cell-derived NCCs from the premigratory to migratory stage remains unclear. In recent years, the use of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells as a revolutionary approach to treat various medical conditions has garnered much attention [17, 18], and iPS cells as a cell source have shown several evident advantages over ES cells and primary cultured cNCCs in regenerative medicine [16]. In addition, embryonic NC development depends on several environmental factors that influence the regulation of NC progenitors and timing of differentiation; therefore, it is important to elucidate the regulatory gene networks and expression profiles of mouse iPS (miPS) cell-derived cNCCs. Recent advances in next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies have facilitated comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles [19–21]. Therefore, in the present study, we used RNA-seq to investigate the gene expression landscape of cNCCs induced from miPS cells. We treated iPS-derived cells with cNCC induction medium for 14 days and performed RNA-seq experiments. Our results indicated that c-Myc; ETS proto-oncogene 1, transcription factor (Ets1); Sox10; a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain metallopeptidase with thrombospondin motifs (Adamts) 2 and 8; protocadherin alpha (Pcdha) 2, 5, -7, -11, and -12; protocadherin alpha subfamily C,1 (Pcdhac1); and protocadherin gamma subfamily C,3 (Pcdhgc3) may be appropriate markers for migratory cNCCs induced from miPS cells.

Materials and methods

miPS cell culture

The miPS cells used in the present study (APS0001; iPS-MEF-Ng-20D-17 mouse-induced pluripotent stem cell line) were purchased from RIKEN BRC (Ibaraki, Japan) [22]. The cells were incubated with inactivated murine embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder cells in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 15% KnockOut™ Serum Replacement (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA), 1% l-glutamine (Chemicon), 1000 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (P/S; Invitrogen), and 0.11 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan); 60-mm cell culture plates were used for passaging the cells at a density of 1 × 105 cells/plate. Cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 95% humidity, and the culture medium was changed each day.

Embryoid body (EB) formation and cNCC differentiation

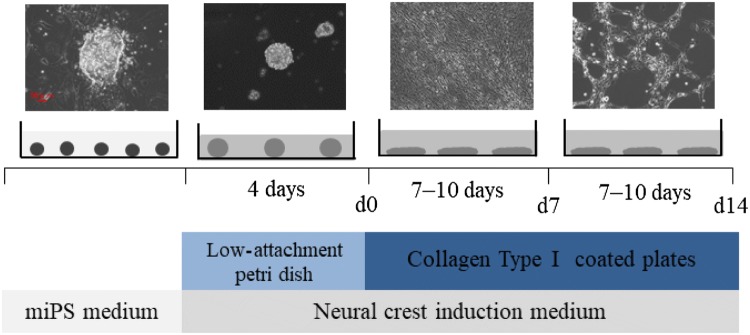

We obtained cultured cNCC cells as described previously [23] (Fig. 1). miPS cells were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Invitrogen) and transferred to low-attachment, 10-mm Petri dishes at a density of 2 × 106 cells/plate to generate EBs. The generated EBs were cultured in cNCC induction medium comprising a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and F12 nutrient mixture (Invitrogen) and then in Neurobasal™ medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 0.5 × N2 (Invitrogen), 0.5 × B27 (Invitrogen), 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (Reprocell, Yokohama, Japan), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (Peprotech, Offenbach, Germany), and 1% P/S for 4 days; the medium was changed every other day. After 4 days, day 0 (d0) EBs were collected and transferred to 60-mm cell culture plates coated with 1 μg/mL collagen type I (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA, USA). The cells were then subcultured in the same medium; the medium changed every other day, and any rosette-forming cells were eliminated. After 7–10 days, d7 cells were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin–EDTA and transferred to 60-mm cell culture plates coated with 1 μg/mL collagen type I at a density of 1 × 105 cells/plate to generate d14 cells. This process was repeated three times. The cells from each of these passages were collected for RNA extraction.

Fig. 1.

The experimental protocol used to induce the formation of cranial neural crest cells (cNCCs) from mouse-induced pluripotent stem (miPS) cells. The photographs show miPS cells at four different stages: initial miPS cells, embryoid body (EB) on day 0 (d0), and cNCCs on d7 and d14. Small circles represent miPS cells; large circles represent EBs; ellipses represent d7 and d14 cells. Scale bar 50 μm

O9-1 cell culture

O9-1 cells, a mouse cNCC line, were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA) and cultured as a control, as previously described [24].

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis (qRT-PCR)

The expression of representative NC markers, namely nerve growth factor receptor (Ngfr), snail family transcriptional repressor (Snai) 1 and 2, and Sox9 and 10, was analyzed using qRT-PCR analysis. Total RNA was extracted using QIAzol® reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and RNA purity was assessed using NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each RNA sample exhibited an A260/A280 ratio of > 1.9. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and qRT-PCR analysis was performed with Premix Ex Taq™ reagent (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System; the primer sequences are presented in Table 1. All samples were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA levels. Relative expressions of genes of interest were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method and were compared among the groups using analysis of variance, followed by the Bonferroni test when significant differences were detected among the groups. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for all analyses, and all data were expressed as mean values and standard deviations.

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

| Gene | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | CGGACAGGATTGACAGATTG | CGCTCCACCAACTAAGAACG |

| Ngfr (p75NTR) | ACTGAGCGCCAGTTACGC | CGTAGACCTTGTGATCCATCG |

| Snail (Snail) | CTTGTGTCTGCACGACCTGT | AGGAGAATGGCTTCTCACCA |

| Snai2 (Slug) | CATTGCCTTGTCTGCAAG | CAGTGAGGGCAAGAGAAAGG |

| Sox9 | GTACCCGCATCTGCACAAC | CTCCTCCACGAAGGGTCTCT |

| Sox10 | ATGTCAGATGGGAACCCAGA | GTCTTTGGGGTGGTTGGAG |

Immunohistochemistry

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) for 15 min followed by methanol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd) for 5 min. After washing, the nonspecific binding of antibodies was blocked by adding 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) in a phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBST) for 1 h. The cells were then incubated with the primary antibodies Snai1 1:50 for Rabbit polyclonal anti-Snai1 (26183-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA.) and Sox10 1:500 for Mouse monoclonal anti-Sox10 (AMAb91297; Atlas Antibodies, Bromma, Sweden.) in PBST for 2 nights at 4 °C. We conducted that the positive control of Snai1 was O9-1 cells (cranial neural crest cells) and the positive control of Sox10 was DP cells (dental pulp cells). The negative control of Snai1 and Sox10 was SNL cells (fetus fibroblast cells) (Fig. S1).They were then incubated in the secondary antibodies fluorescein isothiocyanate Alexa Flour 488-conjugated affinity purified Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H&L) (ab150077; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:500 for Snai1 and Alexa Flour 568-conjugated affinity purified Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H&L) (A-11004; Invitrogen) at a dilution of 1:500 for Sox10 in PBST for 1 h. Eventually, the cells were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma, Livonia, MI, USA) to visualize the nuclear DNA.

RNA-seq

Total RNA from each sample was used to construct libraries with the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Polyadenylated mRNAs are commonly extracted using oligo-dT beads, following which the RNA is often fragmented to generate reads that cover the entire length of the transcripts. The standard Illumina approach relies on randomly primed double-stranded cDNA synthesis, followed by end-repair, dsDNA adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. The multiplexed libraries were sequenced as 125-bp paired-end reads using the Illumina Hiseq 2500 system (Illumina). Prior to performing any analysis, quality of the data was confirmed and read cleaning, such as adapter removal and simple quality filtering, was performed using Trimmomatic (ver. 0.32). Subsequently, the paired-end reads were mapped to the mouse genome reference sequence GRCm38 using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (ver. 0.7.10). The number of sequence reads mapped to each gene domain using SAM tools (ver. 0.1.19) was counted, and the reads per kilobase of transcript per 1 million mapped reads (RPKM) for known transcripts were calculated to normalize the expression level data to gene length and library size, thereby facilitating the comparison of different samples.

Results

Gene expression profiles and immunohistochemistry of cNCCs derived from miPS cells

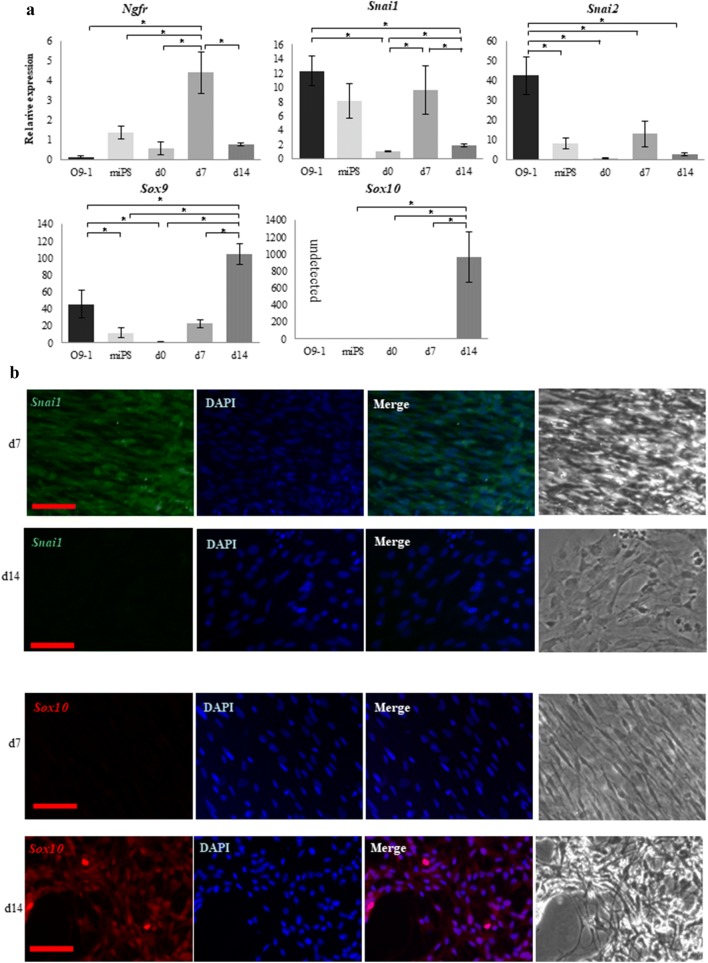

Expressions of the NC markers Ngfr, Snai1, Snai2, Sox9, and Sox10 were examined by qRT-PCR in cNCCs derived from miPS cells as well as in O9-1 cells as a control. Expression of all genes except Ngfr and Sox10 was detected in O9-1 cells [24]. In contrast, expressions of all genes were detected in cNCCs, with the premigratory NC markers Ngfr, Snai1, and Snai2 exhibiting the highest expression levels in d7 cells and the migratory and cranial NC markers Sox9 and Sox10 exhibiting the highest expression levels in d14 cells (Fig. 2a). The strongest immunofluorescent staining was detected for Snai1 and Sox10 in d7 and d14 cells, respectively (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Comparison between O9-1 cells and cranial neural crest cells (cNCCs) derived from mouse-induced pluripotent stem (miPS) cells using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and immunostaining. a Expression of the premigratory neural crest (NC) markers Ngfr, Snai1, and Snai2 and the migratory NC and cNC markers Sox9 and Sox10. Expressions of the premigratory NC markers increased in day 7 (d7) cells, whereas those of the migratory markers increased in d14 cells. Sox10 was not detected in O9-1 cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test: *p < 0.05. b Immunostaining of d7 and d14 cells. Sox10 was more highly expressed in the d14 cells, whereas Snai1 was more highly expressed in the d7 cells. Scale bar 50 μm

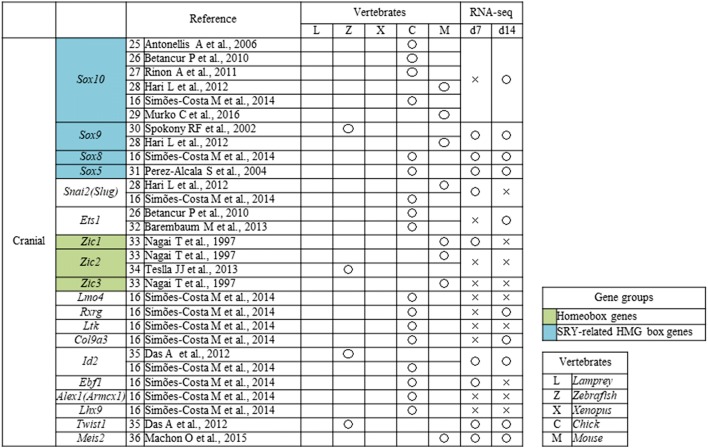

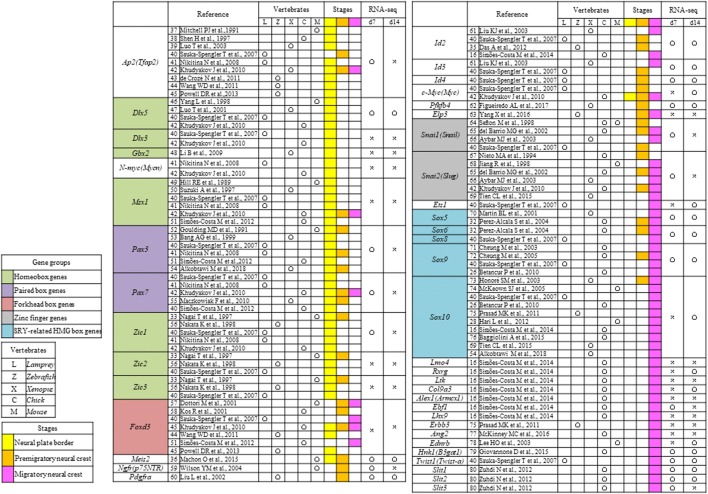

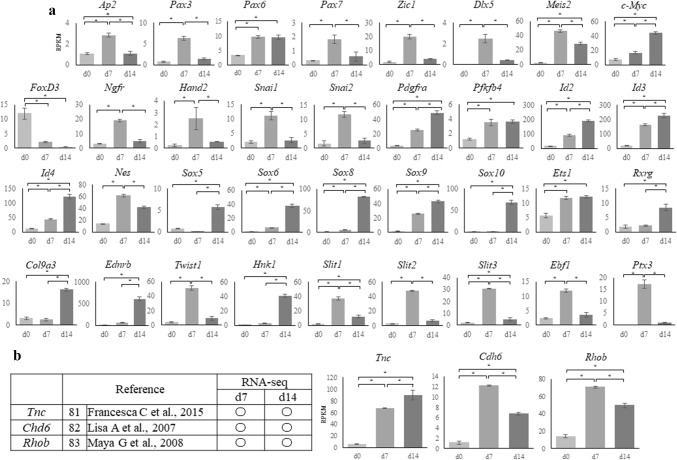

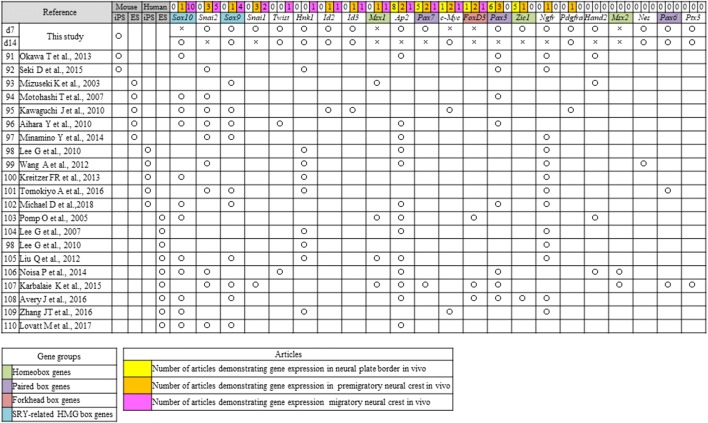

NC specifier transcription factors

We conducted a literature search of NC specifier transcription factors identified in vivo [16, 25–80] (Tables 2, 3) and compared these reports with our RNA-seq results. The relative expressions of genes that underwent a significant change in expression are presented in Fig. 3a.

Table 2.

Neural crest (NC) genes that have previously been examined in vivo

Open circles indicate genes that were upregulated on day 7 (d7) or d14 compared with d0 [log fold change (FC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05), whereas crosses indicate genes that were not upregulated

Table 3.

Neural crest (NC) transcription factors that have previously been examined in vivo

Open circles indicate genes that were upregulated on day 7 (d7) or d14 compared with d0 [log fold change (FC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05), whereas crosses indicate genes that were not upregulated

Fig. 3.

RNA sequencing results for cranial neural crest cells (cNCCs) differentiated from mouse-induced pluripotent stem (miPS) cells. a Expression of each of the genes listed in Table 2 at day 0 (d0), d7, and d14 after induction. Sex-determining region Y (SRY)-related high mobility group (HMG) box genes showed the highest upregulation in d14 cells. The vertical axis reveals reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM), and the horizontal axis indicates time. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test: *p < 0.05. b Expression of genes that have not been examined during the neural crest stages in vivo. Tnc showed the highest upregulation in d14 cells, whereas Cha6 and Rhob were upregulated in day 7 (d7) cells. The vertical axis indicates reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM), and the horizontal axis indicates time. Open circles indicate genes upregulated in d7 or d14 compared with d0 [log fold change (FC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05)]. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test: *p < 0.05

The transcription factor AP-2 alpha (Ap2) along with paired box 3 (Pax3) and zinc finger protein of the cerebellum 1 (Zic1), both of which are regulated by Ap2, were the most highly expressed genes in d7 cells (Fig. 3a). Pax6, which has been reported in human ES and iPS-derived NC cells (Tables 2, 3), was detected in both d7 and d14 cells, whereas Pax7, which has not previously been reported in the mouse NC, was detected in the d7 cells (Fig. 3a). In contrast, the homeobox genes gastrulation brain homeobox 2 (Gbx2), msh homeobox 1 (Msx1), distal-less homeobox 3 (Dlx3), Zic2, and Zic3 were not detected in d7 or d14 cells, and the homeobox genes Zic1 and Dlx5 were only expressed in the d7 cells, despite these having been reported in the NC of a range of species (Table 2); however, Meis homeobox 2 (Meis2) was expressed in both d7 and d14 cells.

The MYCN proto-oncogenes, bHLH transcription factor (N-myc) and c-Myc, have been reported in NCCs (Table 3); however, c-Myc expression was detected in d7 and d14 cells (Fig. 3a), while N-myc was not. Furthermore, there was a gradual and substantial downregulation of the winged-helix transcription factor Forkhead box D3 (FoxD3) (Fig. 3a), which is an important factor for maintaining the pluripotency of ES cells and a key NC specifier that has been implicated in multiple stages of NC development and NCC migration in embryos of various species (Tables 2, 4).

Table 4.

Neural crest (NC) transcription factors that have previously been examined in vitro

Open circles indicate genes that were upregulated on day 7 (d7) or d14 compared with d0 [log fold change (FC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05), whereas crosses indicate genes that were not upregulated

The premigratory NC markers Ngfr, heart and neural crest derivatives expressed 2 (Hand2), Snai1, and Snai2 were only detected in the d7 cells; however, other premigratory NC markers, such as the platelet derived growth factor receptor, alpha polypeptide (Pdgfra); 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 4 (Pfkfb4); inhibitor of DNA binding 2 (Id2), Id3, and Id4; and nestin (Nes) were detected in both d7 and d14 cells (Fig. 3a).

Expression of migratory NC markers such as Sox5, -6, -8, -9, and -10, which encode members of the sex-determining region Y (SRY)-related high mobility group (HMG)-box family of transcription factors and are crucial in several aspects of NCCs, were detected in d7 or d14 cells. Sox10, a known marker for migratory cNCCs in various species (Table 2), was only detected in d14 cells similar to the other migratory NC markers. Twist family bHLH transcription factor 1 (Twist1), which is activated via various signal transduction pathways and is crucial for E-cadherin downregulation, as well as beta-1,3-glucuronyltransferase 1 (B3gat1/Hnk1), which plays a role in the formation of CD57 epitope, was detected in both d7 and d14 cells. In contrast, the expression of the trunk NC markers lit guidance ligand 1/2 (Slit1/2), which plays an important role in trunk NC cell migration toward ventral sites, was upregulated only in d7 cells (Fig. 3a).

Finally, expressions of tenascin C (Tnc), cadherin-6 (Cdh6), and ras homolog family member B (Rhob), all of which are related to cell adhesion and motility [81–85], were significantly increased in both d7 and d14 cells (Fig. 3b).

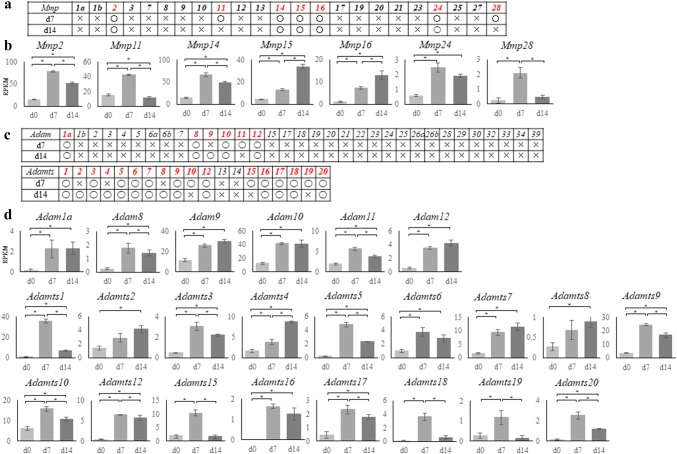

Metzincin superfamily zinc proteinase and protocadherin superfamily

Members of the metzincin superfamily are proteinases that carry a zinc ion at their active site. This family includes the matrix metalloproteinases (Mmps), Adam, and Adamts, all of which have gained attention as factors involved in cancer cell invasion and migration. Mmp2, -11, -14, -15, -16, -24, and -28 were significantly upregulated in cNCCs (Fig. 4a), all of which except Mmp24 are membrane-bound. Mmp11 and -28 were only expressed in d7 cells, whereas all other Mmps were detected in both d7 and d14 cells (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

RNA sequencing results for the matrix metalloproteinase (Mmp), a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (Adam), and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (Adamts) gene families. a Expressions of Mmp family genes in mouse. Round marks alongside day 7 (d7) or d14 cells indicate that the genes were upregulated compared with d0 [log fold change (logFC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05], whereas cross marks indicate lack of upregulation. b Graphical representation of the upregulation of Mmp2, -11, -14, -15, -16, -24, and -28 in d7 or d14 cells. Mmp15 and -16 showed the highest upregulation in d14 cells. The vertical axis indicates reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM), and the horizontal axis indicates time. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test: *p < 0.05. c Expressions of Adam and Adamts genes in mouse. Round marks alongside d7 or d14 cells indicate that the genes were upregulated compared with d0 (logFC > 1, p < 0.01, FDR < 0.05), whereas cross marks indicate lack of upregulation. d Graphical representation of the upregulation of Adam1a and 8–12, and Adamts1–10, -12, and 15–20 in the d7 or d14 cells. Adam2, -4, -7, and -8, and Adamts 9 and -12 showed the highest upregulation in d14 cells. The vertical axis indicates reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM), and the horizontal axis indicates time. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni test: *p < 0.05

Only Adam1a, -8, -10, and -12 were upregulated in both d7 and d14 cells (Fig. 4c, d); this is contrary to reports that the members of this family are important in NC migration and that Adam-10, -12, -15, -19, and -33 are expressed in the mouse NC [86]. Moreover, various Adamts family genes, which are important for connective tissue organization and cell migration, were upregulated in either d7 or d14 cells (Fig. 4c, d). In particular, Adamts1 expression was markedly increased, whereas Adamts2 and -8 expressions, which are presumably important in cancer cell invasion [87–89], increased in the later stages of differentiation.

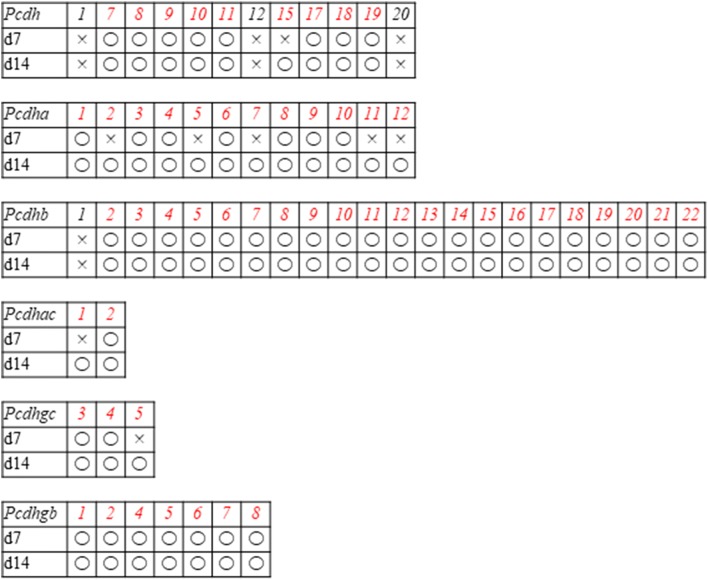

Most Pcdh genes, which are involved in cell adhesion [90], were upregulated in d7 and d14 cells (Table 5); however, Pcdha2, -5, -7, -11, and -12; Pcdhac1; and Pcdhgc5 were only upregulated in d14 cells.

Table 5.

Expression of the protocadherin superfamily based on RNA sequencing data

Open circles indicate genes that were upregulated on day 7 (d7) or d14 compared with d0 [log fold change (FC) > 1, p < 0.01, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05), whereas crosses indicate genes that were not upregulated

Discussion

In the present study, we derived cells from miPS which are closely migratory cNCCs genes. Previously, NCCs have been derived from ES or iPS cells using various approaches [91–110], and the protocol used in the present study was based on the methods outlined by Bajpai et al. [23]; however, few studies have investigated changes in the properties of cNCCs at different time points after induction.

In the present study, d7 and d14 cells expressed typical NC markers, such as Ngfr, Snai1, and Snai2. In contrast, O9-1 cells (controls) did not express Ngfr, suggesting that cNCCs derived from miPS cells are better than O9-1 cells for evaluating cNCC characteristics [24]. Moreover, unlike O9-1 cells, d14 cells expressed markedly high levels of Sox10, which is considered a reliable marker for migratory cNCCs. Since cNCCs are involved in craniofacial tissue organization, several reports are available on their gene expression profiles; however, these reports show varying results with species and protocols. Moreover, cNCCs rapidly differentiate in the embryo [14]; thus, it is considerably difficult to synchronize the timing of isolation to a particular point during their development. Furthermore, migratory cNCCs intermingle with other cell types in the embryo, further complicating the isolation and characterization of a pure cell population. Consequently, there have been few reports on cNCC markers [16, 25–36]. Simões-Costa et al. [16] successfully isolated Sox10-positive cNCCs from chicken embryos and analyzed their gene profiles. Similarly, we detected Sox10 expression in d14 cNCCs. Reportedly, there are multiple NCC populations [11], and iPS cells can differentiate into numerous different NCC populations in the same culture. Therefore, this diversity in populations may explain the discrepancies in results; however, under the conditions used in the present study, c-Myc; Ets1; Sox10; Adamts2; Adamts8; Pcdha2, -5, -7, -11, and -12; Pcdhac1, and Pcdhgc3 may represent useful markers for migratory cNCCs. Furthermore, our results indicated that d7 cells were in the premigratory stage despite expressing numerous NC markers. Therefore, cNCCs derived from miPS cells required > 14 days to become migratory in vitro, and this duration is considerably longer than that observed in the mouse embryos in vivo under the same conditions [111].

The use of RNA-seq facilitates the normalization of expression levels of different genes, allowing comparisons between samples. In our triplicate experiments, none of the induced cNCCs expressed several homeobox genes considered to be expressed in the early stages of cNCC differentiation. In particular, we did not observe FoxD3 expression in either d7 or d14 cells, although it has been recognized as one of the key transcription factors in cNCCs [112]. These contradictory results suggest that cNCCs derived from miPS cells express distinct gene regulatory networks. FoxD3, a pluripotent stem cell marker gene that plays an important role in maintaining pluripotency, is expressed at different time points in different cells, but its expression decreases in a time-dependent manner [41], indicating that FoxD3 may not be a key regulator in iPS-derived cNCCs. However, we speculate that iPS cells express sufficient levels of FoxD3 to differentiate into cNCCs.

Protocadherins belong to the cadherin superfamily and are involved in intercellular interactions [90], whereas metzincins are key proteinases that facilitate cell migration [42]. Unfortunately, the abundances of members of these families hindered their analysis; however, because RNA-seq enabled us to comprehensively evaluate the gene expression profiles, we were able to focus on expressions of all procadherin and metazicin family members. As expected, we observed that several Adam and Adamts genes were upregulated, with most of the Admats genes showing significantly increased expression. The Adam genes with increased expression in cNCCs were membrane-bound, whereas Adamts genes which secreted proteinases, indicating that the expression of various Adamts may allow the matrix to be digested more efficiently and that each proteinase may be capable of digesting a different type of extracellular matrix protein [42]. Therefore, the secretion of various Adamts and Pcdh proteins may play a crucial role in cNCC migration.

Conclusion

In summary, cNCCs derived from miPS exhibited RNA expression profiles that partly overlap with previously reported profiles. These cells may be useful for the regeneration of tissue formed by NCCs (osteoblast, melanocyte, and glial cells). We observed that although the resulting cNCCs exhibited several NC specifiers, they lacked some of the specifiers, indicating that a distinct molecular network may regulate gene expression in miPS-derived cNCCs. Moreover, our results indicated that c-Myc; Ets1; Sox10; Adamts2 and -8; Pcdha2, -5,-7, -11, and -12; Pcdhac1; and Pcdhgc3 may represent appropriate markers for migratory miPS-derived cNCCs. Finally, cNCCs expressed a wide spectrum of genes encoding Adamts family enzymes that may be crucial for their migration.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Comparison between the positive control and the negative control using immunostaining and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). (a) Immunostaining of positive control and negative control. The positive control of Snai1 was O9-1 cells and the positive control of Sox10 was DP cells. The negative control of Snai1 and Sox10 was SNL cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. (b) Expressions of Snai1 and Sox10 increased in the positive control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Student’s t test: *p < 0.05. (DOCX 391 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor T. Azuma, MD, PhD, Department of Biochemistry, and Professor T. Ichinohe, DDS, PhD, Department of Dental Anesthesiology, for their guidance. We also thank S. Onodera and A. Saito, Department of Biochemistry.

Funding

The funding was received by Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant nos. KIBANKENNKYU(B)18H03007 and 18K09753 KIBANKENNKYU(C)).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ayano Odashima, Email: satouayano@tdc.ac.jp.

Toshifumi Azuma, Email: tazuma@tdc.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Luan X, Dangaria S, Ito Y, Walker GG, Jin T, Schmidt MK, Galang MT, Druzinsky R. Neural crest lineage segregation: a blueprint for periodontal regeneration. J Dent Res. 2009;88(9):781–791. doi: 10.1177/0022034509340641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malhotra N. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells in dentistry: a review. Int J Stem Cells. 2016;9(2):176–185. doi: 10.15283/ijsc16029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight RD, Schilling TF. Cranial neural crest and development of the head skeleton. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:120–133. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theveneau E, Mayor R. Collective cell migration of the cephalic neural crest: the art of integrating information. Genesis. 2011;49(4):164–176. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Han J, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127(8):1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell AM, Mito JK, Ablain J, Dang M, Formichella L, Fisher DE, Zon LI. Neural crest state activation in NRAS driven melanoma, but not in NRAS-driven melanocyte expansion. Dev Biol. 2018;449(17):30855–30862. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meulemans D, Bronner-Fraser M. Gene-regulatory interactions in neural crest evolution and development. Dev Cell. 2004;7(3):291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steventon B, Carmona-Fontaine C, Mayor R. Genetic network during neural crest induction: from cell specification to cell survival. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16(6):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simões-Costa M, Bronner ME. Establishing neural crest identity: a gene regulatory recipe. Development. 2015;142(2):242–257. doi: 10.1242/dev.105445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martik ML, Bronner ME. Regulatory logic underlying diversification of the neural crest. Trends Genet. 2017;33(10):715–727. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minoux M, Rijli FM. Molecular mechanisms of cranial neural crest cell migration and patterning in craniofacial development. Development. 2010;137(16):2605–2621. doi: 10.1242/dev.040048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayor R, Theveneau E. The neural crest. Development. 2013;457(1):2247–2251. doi: 10.1242/dev.091751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuno H, Mihara FR, Ohta S, Fukuda K, Kurosawa K, Akamatsu W, Sanosaka TS, Kohyama J, Hayashi K, Nakajima K, Takahashi T, Wysocka J, Kosaki K, Okano H. CHARGE syndrome modeling using patient-iPSCs reveals defective migration of neural crest cells harboring CHD7 mutations. eLife. 2017;6:e21114. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simoes-Costa M, Bronner ME. Reprogramming of avian neural crest axial identity and cell fate. Science. 2016;352(6293):1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milet C, Monsoro-Burq AH. Neural crest induction at the neural plate border in vertebrates. Dev Biol. 2012;366(1):22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simões-Costa M, Tan-Cabugao J, Antoshechkin I, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner ME. Transcriptome analysis reveals novel players in the cranial neural crest gene regulatory network. Genome Res. 2014;24(2):281–290. doi: 10.1101/gr.161182.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi D, Samata B, Katsukawa M, Kikuchi T, Morizane A, Ono Y, Sekiguchi K, Nakagawa M, Parmar M, Takahashi J. Isolation of human induced pluripotent stem cell derived dopaminergic progenitors by cell sorting for successful transplantation. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakane T, Masumoto H, Tinney JP, Yuan F, Kowalski WJ, Ye F, LeBlanc AJ, Sakata R, Yamashita JK, Keller BB. Impact of cell composition and geometry on human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived engineered cardiac tissue. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45641. doi: 10.1038/srep45641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallego RI, Pai AA, Tung J, Gilad Y. RNA-seq: impact of RNA degradation on transcript quantification. BMC Biol. 2014;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(1):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7151):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajpai R, Chen DA, Rada-Iglesias A, Zhang J, Xiong Y, Helms J, Chang CP, Zhao Y, Swigut T, Wysocka J. CHD7 cooperates with PBAF to control multipotent neural crest formation. Nature. 2010;463(7283):958–962. doi: 10.1038/nature08733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishii M, Arias AC, Liu L, Chen YB, Bronner ME, Maxson RE. A stable cranial neural crest cell line from mouse. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(17):3069–3080. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonellis A, Bennett WR, Menheniott TR, Prasad AB, Lee-Lin SQ, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Green ED, Paisley D, Kelsh RN, Pavan WJ, Ward A. Deletion of long-range sequences at Sox10 compromises developmental expression in a mouse model of Waardenburg-Shah (WS4) syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(2):259–271. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betancur P, Bronner-Fraser M, Sauka-Spengler T. Genomic code for Sox10 activation reveals a key regulatory enhancer for cranial neural crest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3570–3575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906596107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinon A, Molchadsky A, Nathan E, Yovel G, Rotter V, Sarig R, Tzahor E. p53 coordinates cranial neural crest cell growth and epithelial–mesenchymal transition/delamination processes. Development. 2011;138(9):1827–1838. doi: 10.1242/dev.053645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hari L, Miescher I, Shakhova O, Suter U, Chin L, Taketo M, Richardson WD, Kessaris N, Sommer L. Temporal control of neural crest lineage generation by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Development. 2012;139(12):2107–2117. doi: 10.1242/dev.073064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murko C, Bronner ME. Tissue specific regulation of the chick Sox10E1 enhancer by different Sox family members. Dev Biol. 2016;422(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spokony RF, Aoki Y, Saint-Germain N, Magner-Fink E, Saint-Jeannet JP. The transcription factor Sox9 is required for cranial neural crest development in Xenopus. Development. 2002;129(2):421–432. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Alcala S, Nieto MA, Barbas JA. LSox5 regulates RhoB expression in the neural tube and promotes generation of the neural crest. Development. 2004;131(18):4455–4465. doi: 10.1242/dev.01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barembaum M, Bronner ME. Identification and dissection of a key enhancer mediating cranial neural crest specific expression of transcription factor, Ets-1. Dev Biol. 2013;382(2):567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagai T, Aruga J, Takada S, Günther T, Spörle R, Schughart K, Mikoshiba K. The expression of the mouse Zic1, Zic2, and Zic3 gene suggests an essential role for Zic genes in body pattern formation. Dev Biol. 1997;182(2):299–313. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teslaa JJ, Keller AN, Nyholm MK, Grinblat Y. Zebrafish Zic2a and Zic2b regulate neural crest and craniofacial development. Dev Biol. 2013;380(1):73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das A, Crump JG. Bmps and id2a act upstream of Twist1 to restrict ectomesenchyme potential of the cranial neural crest. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Machon O, Masek J, Machonova O, Krauss S, Kozmik Z. Meis2 is essential for cranial and cardiac neural crest development. BMC Dev Biol. 2015;15:40. doi: 10.1186/s12861-015-0093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell PJ, Timmons PM, Hébert JM, Rigby PW, Tjian R. Transcription factor AP-2 is expressed in neural crest cell lineages during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5(1):105–119. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen H, Wilke T, Ashique AM, Narvey M, Zerucha T, Savino E, Williams T, Richman JM. Chicken transcription factor AP-2: cloning, expression and its role in outgrowth of facial prominences and limb buds. Dev Biol. 1997;188(2):248–266. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo T, Lee YH, Saint-Jeannet JP, Sargent TD. Induction of neural crest in Xenopus by transcription factor AP2alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(2):532–537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237226100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sauka-Spengler T, Meulemans D, Jones M, Bronner-Fraser M. Ancient evolutionary origin of the neural crest gene regulatory network. Dev Cell. 2007;13(3):405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikitina N, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner-Fraser M. Dissecting early regulatory relationships in the lamprey neural crest gene network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(51):20083–20088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806009105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khudyakov J, Bronner-Fraser M. Comprehensive spatiotemporal analysis of early chick neural crest network genes. Dev Dyn. 2009;238(3):716–723. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Crozé N, Maczkowiak F, Monsoro-Burq AH. Reiterative AP2a activity controls sequential steps in the neural crest gene regulatory network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(1):155–160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010740107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang WD, Melville DB, Montero-Balaguer M, Hatzopoulos AK, Knapik EW. Tfap2a and Foxd3 regulate early steps in the development of the neural crest progenitor population. Dev Biol. 2011;360(1):173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Powell DR, Hernandez-Lagunas L, LaMonica K, Artinger KB. Prdm1a directly activates foxd3 and tfap2a during zebrafish neural crest specification. Development. 2013;140(16):3445–3455. doi: 10.1242/dev.096164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang L, Zhang H, Hu G, Wang H, Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. An early phase of embryonic Dlx5 expression defines the rostral boundary of the neural plate. J Neurosci. 1998;18(20):8322–8330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo T, Matsuo-Takasaki M, Lim JH, Sargent TD. Differential regulation of Dlx gene expression by a BMP morphogenetic gradient. Int J Dev Biol. 2001;45(4):681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Mayor R. The posteriorizing gene Gbx2 is a direct target of Wnt signalling and the earliest factor in neural crest induction. Development. 2009;136(19):3267–3278. doi: 10.1242/dev.036954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill RE, Jones PF, Rees AR, Sime CM, Justice MJ, Copeland NJ, Jenkins NA, Graham E, Davidson DR. A new family of mouse homeo box-containing genes: molecular structure, chromosomal location, and developmental expression of Hox-7.1. Genes Dev. 1998;3(1):26–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki A, Ueno N, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Xenopus msx1 mediates epidermal induction and neural inhibition by BMP4. Development. 1997;124(16):3037–3044. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simões-Costa M, McKeown SJ, Tan-Cabugao J, Sauka-Spengler T, Bronner ME. Dynamic and differential regulation of stem cell factor FoxD3 in the neural crest is encrypted in the genome. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goulding MD, Chalepakis G, Deutsch U, Erselius JR, Gruss P. Pax-3, a novel murine DNA binding protein expressed during early neurogenesis. EMBO J. 1991;10(5):1135–1147. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bang AG, Papalopulu N, Goulding MD, Kintner C. Expression of Pax-3 in the lateral neural plate is dependent on a Wnt-mediated signal from posterior nonaxial mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1999;212(2):366–380. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alkobtawi M, Ray H, Barriga EH, Moreno M, Kerney R, Monsoro-Burq AH, Saint-Jeannet JP, Mayor R. Characterization of Pax3 and Sox10 transgenic Xenopus laevis embryos as tools to study neural crest development. Dev Biol. 2018;444(17):30693–30700. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maczkowiak F, Matéos S, Wang E, Roche D, Harland R, Monsoro-Burq AH. The Pax3 and Pax7 paralogs cooperate in neural and neural crest patterning using distinct molecular mechanisms, Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Biol. 2010;340(2):381–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakata K, Nagai T, Aruga J, Mikoshiba K. Xenopus Zic family and its role in neural crest development. Mech Dev. 1998;75(1–2):43–51. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dottori M, Gross MK, Labosky P, Goulding M. The winged helix transcription factor Foxd3 suppresses interneuron differentiation and promotes neural crest cell fate. Development. 2001;128(21):4127–4138. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kos R, Reedy MV, Johnson RL, Erickson CA. The winged-helix transcription factor FoxD3 is important for establishing the neural crest lineage and repressing melanogenesis in avian embryos. Development. 2001;128(8):1467–1479. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson YM, Richards KL, Ford-Perriss ML, Panthier JJ, Murphy M. Neural crest cell lineage segregation in the mouse neural tube. Development. 2004;131(24):6153–6162. doi: 10.1242/dev.01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu L, Chong SW, Balasubramaniyan NV, Korzh V, Ge R. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (pdgfr-α) gene in zebrafish embryonic development. Mech Dev. 2002;116:227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu KJ, Harland RM. Cloning and characterization of Xenopus Id4 reveals differing roles for Id genes. Dev Biol. 2003;264(2):339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Figueiredo AL, Maczkowiak F, Borday C, Pla P, Sittewelle M, Pegoraro C, Monsoro Burq AH. PFKFB4 control of AKT signaling is essential for premigratory and migratory neural crest formation. Development. 2017;144(22):4183–4194. doi: 10.1242/dev.157644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang X, Li J, Zeng W, Li C, Mao B. Elongator protein 3 (Elp3) stabilizes Snail1 and regulates neural crest migration in Xenopus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26238. doi: 10.1038/srep26238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sefton M, Sánchez S, Nieto MA. Conserved and divergent roles for members of the Snail family of transcription factors in the chick and mouse embryo. Development. 1998;125(16):3111–3121. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.16.3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.del Barrio MG, Nieto MA. Overexpression of Snail family members highlights their ability to promote chick neural crest formation. Development. 2002;129(7):1583–1593. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.7.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aybar MJ, Nieto MA, Mayor R. Snail precedes Slug in the genetic cascade required for the specification and migration of the Xenopus neural crest. Development. 2003;130(3):483–494. doi: 10.1242/dev.00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nieto MA, Sargent MG, Wilkinson DG, Cooke J. Control of cell behavior during vertebrate development by Slug, a zinc finger gene. Science. 1994;264(5160):835–859. doi: 10.1126/science.7513443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiang R, Lan Y, Norton CR, Sundberg JP, Gridley T. The Slug gene is not essential for mesoderm or neural crest development in mice. Dev Biol. 1998;198(2):277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tien CL, Jones A, Wang H, Gerigk M, Nozell S, Chang C. Snail2/Slug cooperates with Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to regulate neural crest development. Development. 2015;142(4):722–731. doi: 10.1242/dev.111997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin BL, Harland RM. Hypaxial muscle migration during primary myogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Dev Biol. 2001;239(2):270–280. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheung M, Briscoe J. Neural crest development is regulated by the transcription factor Sox9. Development. 2003;130(23):5681–5693. doi: 10.1242/dev.00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheung M, Chaboissier MC, Mynett A, Hirst E, Schedl A, Briscoe J. The transcriptional control of trunk neural crest induction, survival, and delamination. Dev Cell. 2005;8(2):179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Honoré SM, Aybar MJ, Mayor R. Sox10 is required for the early development of the prospective neural crest in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2003;260(1):79–96. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McKeown SJ, Lee VM, Bronner-Fraser M, Newgreen DF, Farlie PG. Sox10 overexpression induces neural crest-like cells from all dorsoventral levels of the neural tube but inhibits differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2005;233(2):430–444. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prasad MK, Reed X, Gorkin DU, Cronin JC, McAdow AR, Chain K, Hodonsky CJ, Jones EA, Svaren J, Antonellis A, Johnson SL, Loftus SK, Pavan WJ, McCallion AS. SOX10 directly modulates ERBB3 transcription via an intronic neural crest enhancer. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baggiolini A, Varum S, Mateos JM, Bettosini D, John N, Bonalli M, Ziegler U, Dimou L, Clevers H, Furrer R, Sommer L. Premigratory and migratory neural crest cells are multipotent in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McKinney MC, McLennan R, Kulesa PM. Angiopoietin 2 signaling plays a critical role in neural crest cell migration. BMC Biol. 2016;14(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee HO, Levorse JM, Shin MK. The endothelin receptor-B is required for the migration of neural crest-derived melanocyte and enteric neuron precursors. Dev Biol. 2003;259(1):162–175. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Giovannone D, Ortega B, Reyes M, El-Ghali N, Rabadi M, Sao S, de Bellard ME. Chicken trunk neural crest migration visualized with HNK1. Acta Histochem. 2015;117(3):255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zuhdi N, Ortega B, Giovannone D, Ra H, Reyes M, Asención V, McNicoll I, Ma L, de Bellard ME. Slits affect the timely migration of neural crest cells via robo receptor. Dev Dyn. 2012;241(8):1274–1288. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chiovaro F, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Chiquet M. Transcriptional regulation of tenascin genes. Cell Adhes Migr. 2015;9(1–2):34–47. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1008333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taneyhill AL, Coles EG, Bronner-Fraser M. Snail2 directly represses cadherin6B during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions of the neural crest. Development. 2007;134(8):1480–1490. doi: 10.1242/dev.02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Groysman M, Shoval I, Kalcheim C. A negative modulatory role for rho and rho-associated kinase signaling in delamination of neural crest cells. Neural Dev. 2008;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vega FM, Thomas M, Reymond N, Ridley AJ. The Rho GTPase RhoB regulates cadherin expression and epithelial cell–cell interaction. Cell Commun Signal. 2015;13:6. doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0085-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Q, Dalman MR, Sarmah S, Chen S, Chen Y, Hurlbut AK, Spencer MA, Pancoe L, Marrs JA. Cell adhesion molecule cadherin-6 function in zebrafish cranial and lateral line ganglia development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(7):1716–1726. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tomczuk M, Takahashi Y, Huang J, Murase S, Mistretta M, Klaffky E, Sutherland A, Bolling L, Coonrod S, Marcinkiewicz C, Sheppard D, Stepp MA, White JM. Role of multiple beta1 integrins in cell adhesion to the disintegrin domains of ADAMs 2 and 3. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290(1):68–81. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Desanlis I, Felstead HL, Edwards DR, Wheeler GN. ADAMTS9, a member of the ADAMTS family, in Xenopus development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2018;29:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Porter S, Clark IM, Kevorkian L, Edwards DR. The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem J. 2005;386(1):15–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hubmacher D, Apte SS. ADAMTS proteins as modulators of microfibril formation and function. Matrix Biol. 2015;47(2015):34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen WV, Maniatis T. Clustered protocadherins. Development. 2013;140(16):3297–3302. doi: 10.1242/dev.090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Okawa T, Kamiya H, Himeno T, Kato J, Seino Y, Fujiya A, Kondo M, Tsunekawa S, Naruse K, Hamada Y, Ozaki N, Cheng Z, Kito T, Suzuki H, Ito S, Oiso Y, Nakamura J, Isobe K. Transplantation of neural crest-like cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells improves diabetic polyneuropathy in mice. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(10):1767–1783. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seki D, Takeshita N, Oyanagi T, Sasaki S, Takano I, Hasegawa M, Takano-Yamamoto T. Differentiation of odontoblast-like cells from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells by Pax9 and Bmp4 transfection stem cells. Transl Med. 2015;4(9):993–997. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mizuseki K, Sakamoto T, Watanabe K, Muguruma K, Ikeya M, Nishiyama A, Arakawa A, Suemori H, Nakatsuji N, Kawasaki H, Murakami F, Sasai Y. Generation of neural crest-derived peripheral neurons and floor plate cells from mouse and primate embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):5828–5833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Motohashi T, Aoki H, Chiba K, Yoshimura N, Kunisada T. Multipotent cell fate of neural crest-like cells derived from embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25(2):402–412. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kawaguchi J, Nichols J, Gierl MS, Faial T, Smith A. Isolation and propagation of enteric neural crest progenitor cells from mouse embryonic stem cells and embryos. Development. 2010;137(5):693–704. doi: 10.1242/dev.046896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aihara Y, Hayashi Y, Hirata M, Ariki N, Shibata S, Nagoshi N, Nakanishi M, Ohnuma K, Warashina M, Michiue T, Uchiyama H, Okano H, Asashima M, Furue MK. Induction of neural crest cells from mouse embryonic stem cells in a serum-free monolayer culture. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54(8–9):1287–1294. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103173ya. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Minamino Y, Ohnishi Y, Kakudo K, Nozaki M. Isolation and propagation of neural crest stem cells from mouse embryonic stem cells via cranial neurospheres. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(2):172–181. doi: 10.1089/scd.2014.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee G, Chambers SM, Tomishima MJ, Studer L. Derivation of neural crest cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):688–701. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang A, Tang Z, Li X, Jiang Y, Tsou DA, Li S. Derivation of smooth muscle cells with neural crest origin from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;195(1–2):5–14. doi: 10.1159/000331412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kreitzer FR, Salomonis N, Sheehan A, Huang M, Park JS, Spindler MJ, Lizarraga P, Weiss WA, So PL, Conklin BR. A robust method to derive functional neural crest cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Am J Stem Cells. 2013;2(2):119–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tomokiyo A, Hynes K, Ng J, Menicanin D, Camp E, Arthur A, Gronthos S, Mark Bartold P. Generation of neural crest-like cells from human periodontal ligament cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(2):402–416. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Michael D, Wagoner MD, Bohrer LR, Aldrich BT, Greiner MA, Mullins RF, Worthington KS, Tucker BA, Wiley LA. Feeder-free differentiation of cells exhibiting characteristics of corneal endothelium from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Biol Open. 2018;7(5):bio032102. doi: 10.1242/bio.032102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pomp O, Brokhman I, Ben-Dor I, Reubinoff B, Goldstein RS. Generation of peripheral sensory and sympathetic neurons and neural crest cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem cells. 2005;23(7):923–930. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee G, Kim H, Elkabetz Y, Al Shamy G, Panagiotakos G, Barberi T, Tabar V, Studer L. Isolation and directed differentiation of neural crest stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(12):1468–1475. doi: 10.1038/nbt1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Q, Spusta SC, Mi R, Lassiter RN, Stark MR, Höke A, Rao MS, Zeng X. Human neural crest stem cells derived from human ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells: induction, maintenance, and differentiation into functional schwann cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1(4):266–278. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Noisa P, Lund C, Kanduri K, Lund R, Lähdesmäki H, Lahesmaa R, Lundin K, Chokechuwattanalert H, Otonkoski T, Tuuri T, Raivio T. Notch signaling regulates the differentiation of neural crest from human pluripotent stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2083–2094. doi: 10.1242/jcs.145755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Karbalaie K, Tanhaei S, Rabiei F, Kiani-Esfahani A, Masoudi NS, Nasr-Esfahani MH, Baharvand H. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous tooth exhibit stromal-derived inducing activity and lead to generation of neural crest cells from human embryonic stem cells. Cell J. 2015;17(1):37–48. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2015.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Avery J, Dalton S. Methods for derivation of multipotent neural crest cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1341:197–208. doi: 10.1007/7651_2015_234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang JT, Weng ZH, Tsang KS, Tsang LL, Chan HC, Jiang XH. MycN is critical for the maintenance of human embryonic stem cell-derived neural crest stem cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lovatt M, Yam GH, Peh GS, Colman A, Dunn NR, Mehta JS. Directed differentiation of periocular mesenchyme from human embryonic stem cells. Differentiation. 2018;99:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dennis AR, McLennan R, Jessica MT, Craig LS, Jeffrey SH, Kulesa PM. The neural crest cell cycle is related to phases of migration in the head. Development. 2014;141(5):1095–1103. doi: 10.1242/dev.098855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Krishnakumar R, Chen AF, Pantovich MG, Danial M, Parchem RJ, Labosky PA, Blelloch R. FOXD3 regulates pluripotent stem cell potential by simultaneously initiating and repressing enhancer activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(1):104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison between the positive control and the negative control using immunostaining and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). (a) Immunostaining of positive control and negative control. The positive control of Snai1 was O9-1 cells and the positive control of Sox10 was DP cells. The negative control of Snai1 and Sox10 was SNL cells. Scale bar = 50 μm. (b) Expressions of Snai1 and Sox10 increased in the positive control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, with values representing mean ± SD. Groups were compared using ANOVA, followed by the Student’s t test: *p < 0.05. (DOCX 391 kb)